| Revision as of 06:25, 25 May 2004 editVanished user 5zariu3jisj0j4irj (talk | contribs)36,325 editsm rv← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 10:17, 4 January 2025 edit undoOnel5969 (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Page movers, New page reviewers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers937,219 editsm Disambiguating links to Western culture (disambiguation) (link changed to Western culture) using DisamAssist. | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|none}} | |||

| The original '''culture of Australia''' can only be surmised: cultural patterns among the remote descendants of the first Australians cannot be assumed to be unchanged after 53,000 years of human habitation of the continent. Much more is known about the richly diverse cultures of modern Aboriginal Australians, or at least of those few who survived the impact of European colonisation. (For more on this, see ] and related entries.) Although the effect of the arrival of Europeans on Aboriginal culture was profound and catastrophic, the reverse is not the case: broadly speaking, mainstream ]n culture has been imported from Europe, the ] in particular, and has developed since that time with very little input from Aboriginal people. | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=November 2019}} | |||

| {{Use Australian English|date=May 2011}} | |||

| {{Culture of Australia}} | |||

| '''Australian culture''' is of primarily ] origins, and is derived from its ], ] and migrant components. | |||

| Indigenous peoples arrived as early as 60,000 years ago, and evidence of ] in Australia dates back at least 30,000 years.<ref>{{cite web |title=About Australia: Indigenous peoples: an overview |url=http://www.dfat.gov.au/facts/Indigenous_peoples.html |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101122064834/http://dfat.gov.au/facts/Indigenous_peoples.html |archive-date=22 November 2010 |access-date=26 September 2010 |publisher=]}}</ref> The ] began in 1788 and waves of multi-ethnic (primarily ]) migration followed shortly thereafter. Several ] had their origins as ], with this ] having an enduring effect on ], ] and ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Clancy|pp=9–10}}</ref> | |||

| ==Overview== | |||

| Manifestations of British colonial heritage in ] include the primacy of the ] and ], the institution of ], a ]-style system of democratic ] government, and Australia's inclusion within the ]. The American political ideals of ] and ] have also played a role in shaping Australia's distinctive political identity. | |||

| Much of Australia's culture is derived from European and more recently American roots, but distinctive Australian features have evolved from the environment, aboriginal culture, and the influence of Australia's neighbors. The vigor and originality of the arts in Australia—films, opera, music, painting, theater, dance, and crafts—are achieving international recognition. | |||

| The ] from the 1850s resulted in exponential population and economic growth, as well as racial tensions and the introduction of novel political ideas;<ref>{{Harvnb|Clancy|pp=10–12}}</ref> the growing disparity between the prospectors and the established colonial governments culminated in the ] rebellion and the shifting political climate ushered in significant electoral reform, the labour movement, and women's rights ahead of any such changes in other Western countries.<ref>{{cite web |title= Gold rushes |url=https://www.nma.gov.au/defining-moments/resources/gold-rushes |website=www.nma.gov.au |access-date=29 August 2024 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| ==Music== | |||

| ] occurred in 1901 as the result of a burgeoning sense of national unity and identity that had developed over the latter half of the 19th century, hitherto demonstrated in the works of ] artists and authors like ], ], and ]. ] and ] profoundly impacted Australia, ushering in the heroic ] legend of the former and the geopolitical reorientation in which the United States became Australia's foremost military ] after the latter. After the Second World War, 6.5 million people settled in Australia from 200 nations, further enriching Australian culture in the process. Over time, as immigrant populations gradually assimilated into Australian life, their cultural and culinary practices became part of mainstream Australian culture.<ref name="Reference">{{cite web|url=http://australia.gov.au/about-australia/our-country |title=About Australia: Our Country |publisher= australia.gov.au |access-date=25 October 2013}}</ref><ref name="Referencea">{{cite web|url=http://www.dfat.gov.au/facts/people_culture.html |title=About Australia: People, culture and lifestyle |publisher=Dfat.gov.au |access-date=25 October 2013 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120512195954/http://dfat.gov.au/facts/people_culture.html |archive-date=12 May 2012}}</ref> | |||

| ''Main article:'' ] | |||

| ==Historical development of Australian culture== | |||

| Australia has produced a wide variety of popular music. While many musicians and bands (some notable examples include the ] successes of ] and the folk-pop group ], through the heavy rock of ], and the slick pop of ] and more recently ]) have had considerable international success, there remains some debate over whether Australian popular music really has a distinctive sound. Perhaps the most striking common feature of Australian music, like many other Australian art forms, is the dry, often self-deprecating humor evident in the lyrics. | |||

| {{Main|History of Australia}} | |||

| ] man demonstrating method of attack with ] under cover of shield (1920)]] | |||

| The oldest surviving cultural traditions of Australia—and some of the oldest surviving cultural traditions on earth—are those of Australia's ] and ] peoples, collectively referred to as ]. Their ancestors have inhabited Australia for between 40,000 and 60,000 years, living a ] lifestyle. In 2006, the Indigenous population was estimated at 517,000 people, or 2.5 per cent of the total population.<ref>{{cite book|title=Year Book Australia|publisher=Australian Bureau of Statistics|year=2012|series=1301.0|chapter=Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Population|url=http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/1301.0~2012~Main%20Features~Aboriginal%20and%20Torres%20Strait%20Islander%20population~50|access-date=21 November 2012}}</ref> Most Aboriginal Australians have a belief system based on the ], or Dreamtime, which refers both to a time when ancestral spirits created land and culture, and to the knowledge and practices that define individual and community responsibilities and identity.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://australianmuseum.net.au/Indigenous-Australia-Spirituality|title=Indigenous Australians – Spirituality|year=2009|publisher=Australian Museum|access-date=21 November 2012}}</ref> | |||

| The arrival of the ] at what is now Sydney in 1788 introduced ] to the Australian continent. Although Sydney was initially used by the British as a place of banishment for prisoners, the arrival of the British laid the foundations for Australia's democratic institutions and rule of law,<ref>{{Cite book |last=Cook |first=Catriona |title=Laying down the law |publisher=] |year=2015 |isbn=9780409336221 |edition=9th |location=Chatswood, NSW |page=35 |access-date=}}</ref> and introduced the long traditions of ], ] and music, and ] ethics and religious outlook which shaped the Australian national culture and identity.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Kirillova |first=Olga O. |date=25 August 2014 |title=BRITISH CUSTOMS AND TRADITIONS IN AUSTRALIA: THEIR TRANSFORMATION AND ADAPTATION |url=https://www.scientific-publications.net/en/article/1000326/ |journal=Language, Individual & Society |language=en |volume=8 |issue=1 |pages=101–112 |issn=1314-7250}}</ref> | |||

| ==Arts and literature== | |||

| ] hoists the British flag over the new colony at ] in 1788]] | |||

| Main articles: ] | |||

| The ] expanded across the whole continent and established six colonies. The colonies were originally penal colonies, with the exception of Western Australia and ], which were each established as a "free colony" with no convicts and a vision for a territory with political and religious freedoms, together with opportunities for wealth through business and pastoral investments.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://foundingdocs.gov.au/item.asp?sdID=37 |title=Documenting a Democracy – South Australia Act, or Foundation Act, of 1834 (UK) | |||

| |publisher=] |access-date=11 June 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110602002025/http://www.foundingdocs.gov.au/item.asp?sdID=37|archive-date=2 June 2011}}</ref> However, Western Australia became a penal colony after insufficient numbers of free settlers arrived. Adelaide, the capital of South Australia, grew from its status as a convict free region and experienced prosperity from the late nineteenth century. | |||

| Contact between the Indigenous Australians and the new settlers ranged from cordiality to violent conflict, but the diseases brought by Europeans were devastating to Aboriginal populations and culture. According to the historian ], during the colonial period: "Smallpox, measles, influenza and other new diseases swept from one Aboriginal camp to another ... The main conqueror of Aborigines was to be disease and its ally, demoralization."<ref>{{cite book|first=Geoffrey|last=Blainey|year=2001 |title=A Very Short History of the World|publisher=Penguin House|page=321|isbn=978-1-56663-507-3}}</ref>] (1790–1872) was among the first to articulate a vision of Australian nationhood.|left]] | |||

| Australia has had a significant school of painting since the early days of European settlement, and Australians with international reputations include ], ], and ]—not to mention the prized work of many Aboriginal artists. Writers who have achieved world recognition include ], ], ], ], ], ] winner ] and ] winner ]. | |||

| Calls for ] began to develop; ] established ] in 1835 to demand democratic government for New South Wales and later was central in the establishment of ]. From the 1850s, the colonies set about writing constitutions which produced democratically advanced parliaments as ] with ] as the head of state.<ref name="Tink">{{Cite book |author1=Tink, Andrew |url=https://trove.nla.gov.au/work/28173894 |title=William Charles Wentworth : Australia's greatest native son |date=2009 |publisher=Allen & Unwin |isbn=978-1-74175-192-5}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date=2018-03-12 |title=The Right to Vote in Australia |url=http://aec.gov.au/Elections/Australian_Electoral_History/righttovote.htm |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180312191539/http://aec.gov.au/Elections/Australian_Electoral_History/righttovote.htm |archive-date=12 March 2018 |access-date=2024-03-26 |website=]}}</ref>]n suffragette ] (1825–1910). The Australian colonies established democratic parliaments from the 1850s and began to grant women the vote in the 1890s.|alt=Nig.ger]]] was achieved from the 1890s.<ref name="autogenerated1"></ref> Women became eligible to vote in South Australia in 1895. This was the ] in the world permitting women to stand for political office and, in 1897, ], an Adelaidean, became the first female political candidate.<ref>{{Harvnb|Clancy|pp=15–17}}</ref><ref name="aec.gov.au">{{cite web|url=http://www.aec.gov.au/Voting/indigenous_vote/indigenous.htm |title=AEC.gov.au |publisher=AEC.gov.au |date=25 October 2007 |access-date=27 June 2010}}</ref><ref> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101203020826/http://www.foundingdocs.gov.au/item.asp?dID=8 |date=3 December 2010}}</ref> Though constantly evolving, the key foundations for elected parliamentary government have maintained an historical continuity in Australia from the 1850s into the 21st century. | |||

| During the colonial era, distinctive forms of ], ], ] and ] developed through movements like the ] of painters and the work of ]eers like ] and ], whose poetry and prose did much to promote an egalitarian Australian outlook which placed a high value on the concept of "]". Games like ] and ] were imported from Britain at this time and with a local variant of football, ], became treasured cultural traditions.<ref>{{Cite news |last=Clarey |first=Christopher |date=13 March 2012 |title=Britannia's Games Still Rule Down Under |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/14/sports/olympics/14iht-srolyaustralia14.html |access-date=15 August 2024 |work=The New York Times |language=en-US |issn=0362-4331}}</ref> | |||

| The ] was founded in 1901, after a series of referendums conducted in the British colonies of ]. The ] established a federal democracy and enshrined ] such as sections 41 (right to vote), 80 (right to trial by jury) and 116 (freedom of religion) as foundational principles of Australian law and included economic rights such as restricting the government to acquiring property only "on just terms".<ref></ref> The ] was established in the 1890s and the ] in 1944, both rising to be the dominant political parties and rivals of ], though various ] have been and remain influential. Voting is compulsory in Australia and government is essentially formed by a group commanding a majority of seats in the ] selecting a leader who becomes ]. Australia remains a ] in which the largely ceremonial and procedural duties of the monarch are performed by a ] selected by the Australian government.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Why are we a constitutional monarchy? - Parliamentary Education Office |url=https://peo.gov.au/understand-our-parliament/your-questions-on-notice/questions/why-are-we-a-constitutional-monarchy |access-date=15 August 2024 |website=Parliamentary Education Office |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| ==Cinema== | |||

| Australia fought at Britain's side from the outset of ] and ] and came under attack from the Empire of Japan during the latter conflict. These wars profoundly affected Australia's sense of nationhood and a proud military legend developed around the spirit of Australia's ] troops, who came to symbolise the virtues of endurance, courage, ingenuity, good humour, and mateship.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Anzac spirit |url=https://www.awm.gov.au/articles/encyclopedia/anzac/spirit |access-date=15 August 2024 |website=www.awm.gov.au}}</ref> | |||

| ''Main article:'' ] | |||

| The Australian colonies had a period of extensive non-British European and ] immigration during the ] of the latter half of the 19th century, but following Federation in 1901, the Parliament instigated the ] that gave preference to British migrants and ensured that Australia remained a predominantly Anglo-Celtic society until well into the 20th century. The post-] immigration program saw the policy relaxed then dismantled by successive governments, permitting large numbers of non-British Europeans, and later Asian and Middle Eastern migrants to arrive. The ] and ] maintained the White Australia Policy but relaxed it, and then the legal barriers to multiracial immigration were dismantled during the 1970s, with the promotion of ] by the ] and ]s.<ref>{{Harvnb|Clancy|pp=22–23}}</ref><ref> {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060901105340/http://www.immi.gov.au/media/fact-sheets/08abolition.htm |date=1 September 2006}}</ref> | |||

| Australia has a long history of film production—in fact, it is claimed that the first feature-length film was actually an Australian production. However, during the late 1960s and 1970s in influx of government funding saw the development of a new generation of directors and actors telling distinctively Australian stories. The 1980s is regarded as perhaps a golden age of Australian cinema, with many wildly successful films, from the apocalyptic science fiction of ] to the blatantly commercial Aussie-bloke fantasy of ], a film that defined Australia in the eyes of many foreigners despite having remarkably little to do with the lifestyle of most Australians. The indigenous film industry continues to produce a reasonable number of films each year, also many US producers have moved productions to Australian studios as they discover a pool of professional talent well below US costs. Notable productions include '']'' and the '']'' Episode II and III. | |||

| ]|date=29 March 2007|access-date=6 March 2009}} (table 6.6)</ref>]] | |||

| ==Australian culture: schools of thought== | |||

| From the protest movements from the 1930s, with the gradual lifting of restrictions, Indigenous Australians began to develop a unity sense of ], maintained by all Aboriginal artists, musicians, sportsmen and writers.<ref name="abcult">{{Cite web |last= |first= |date=1 January 1991 |title=Unity and Diversity: The History and Culture of Aboriginal Australia |url=https://www.abs.gov.au/Ausstats/abs@.nsf/0/75258e92a5903e75ca2569de0025c188?OpenDocument |access-date=25 August 2024 |website=abs.gov.au |language=en}}</ref> However, some ] retained discriminatory laws relating to voting rights for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people into the 1960s, at which point full legal equality was established. A ] to include all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the national electoral roll census was overwhelmingly approved by voters, signal the beginning of action and organisation at a national level in Aboriginal affairs.<ref name="abcult" /><ref>{{Cite web |last= |first= |date=12 July 2024 |title=The 1967 Referendum |url=https://aiatsis.gov.au/explore/1967-referendum |access-date=25 August 2024 |website=Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies |language=en}}</ref> Since then, conflict and ] has been a source of much art and literature in Australia.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Savvas |first=Michael |date=2012 |title=Storytelling reconciliation: The Role of Literature in Reconciliation in Australia |url=https://researchnow.flinders.edu.au/en/publications/storytelling-reconciliation-the-role-of-literature-in-reconciliat |journal=International Journal of Diversity in Organisations, Communities and Nations |volume=11 |issue=5 |pages=95–108 |doi=10.18848/1447-9532/CGP/v11i05/39050 |issn=1447-9532}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=Ways |first=Faiza |date=28 October 2021 |title=Art is Our Voice |url=https://www.reconciliation.org.au/art-is-our-voice/ |access-date=15 August 2024 |website=Reconciliation Australia |language=en-AU}}</ref> In 1984, ] ] people who were living a traditional ] desert-dwelling life were tracked down in the ] and brought into a settlement. They are believed to have been the last ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://recollections.nma.gov.au/issues/vol_1_no_2/exhibition_reviews/colliding_worlds/ |title=Colliding worlds: first contact in the western desert, 1932–1984 |publisher=Recollections.nma.gov.au |access-date=12 October 2009}}</ref> | |||

| As to culture in the narrow sense - culture as voluntary, often non-economic activity - there are several schools of thought. One maintains that Australia has no real culture outside of second-hand imports from ] and the ]. Proponents of this view point to the predominance of foreign books, music, and art, and claim that home-grown products are largely derivative. | |||

| While the British cultural influence remained strong into the 21st century, other influences became increasingly important. Australia's post-war period was marked by an influx of Europeans who broadened the nation's vision.<ref name="fma">{{cite book |last1=Wildman |first1=Kim |last2=Hogue |first2=Derry |date=2015 |title=First Among Equals: Australian Prime Ministers from Barton to Turnbull |location=Wollombi, NSW |publisher=Exisle Publishing |page=87 |isbn=978-1-77559-266-2}}</ref> The Hawaiian sport of surfing was adopted in Australia where a beach culture and the locally developed ] movement was already burgeoning in the early 20th century. American pop culture and cinema were embraced in the 20th century, with country music and later rock and roll sweeping Australia, aided by the new technology of television and a host of American content. The 1956 ], the first to be broadcast to the world,<ref name="fma"/> announced a confident, prosperous post-war nation, and new cultural icons like ] star ] and ] Barry Humphries expressed a uniquely Australian identity. | |||

| For years, many Australians suffered from an inferiority complex or "cultural cringe" about other countries, particularly European ones, believing that anything from overseas was inherently superior to anything Australian. This was especially true in Australia's relationship with ], but as Australians have travelled more widely, and their country has been exposed to cultural influences from other countries, this has waned. Australians still have "love-hate" relationship with Britain. On the one hand, they ridicule the so-called 'Old Country' as snobbish, class-obsessed and backward-looking. On the other, there is a large Australian expatriate population in ], including the writers ] and ], who are sometimes better known in the UK than they are in Australia. | |||

| Australia's contemporary immigration program has two components: a program for skilled and family migrants and a humanitarian program for refugees and asylum seekers.<ref> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081001125010/http://www.immi.gov.au/media/fact-sheets/60refugee.htm |date=1 October 2008 }}</ref> By 2010, the post-war immigration program had received more than 6.5 million migrants from every continent. The population tripled in the six decades to around 21 million in 2010, including people originating from 200 countries.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.dfat.gov.au/aib/overview.html |title=Australia in Brief: Australia – an overview – Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade |access-date=1 May 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110216000834/http://www.dfat.gov.au/aib/overview.html |archive-date=16 February 2011 |url-status=dead }}</ref> More than 43 per cent of Australians were either born overseas or have one parent who was born overseas. The population is highly urbanised, with more than 75% of Australians living in urban centres, largely along the coast though there has been increased incentive to ] the population, concentrating it into developed regional or rural areas.<ref name="ReferenceA">{{cite web|url=http://www.dfat.gov.au/facts/people_culture.html |title=About Australia: People, culture and lifestyle |publisher=Dfat.gov.au |access-date=29 January 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120512195954/http://dfat.gov.au/facts/people_culture.html |archive-date=12 May 2012}}</ref> | |||

| Others seize eagerly on each small point of difference, and brandish relatively small parts of the Australian cultural experience (such as the poetry of ], ], or the ]) as if these were sufficient to demonstrate that a new and vital culture has emerged in the two centuries since European settlement. | |||

| Contemporary Australia is a pluralistic society, rooted in ] traditions and espousing informality and egalitarianism as key societal values. While strongly influenced by ] origins, the culture of Australia has also been shaped by multi-ethnic migration which has influenced all aspects of Australian life, including business, the arts, ], ] and sporting tastes.<ref>{{Harvnb|Clancy|pp=23}}</ref><ref name="ReferenceA"/> | |||

| Somewhere in between these two views may be found the great central thread of debate about Australian culture: the perennial attempt to ask and answer the question, "Does Australia 'have' a culture, and if so what is it?" The obsessive preoccupation with this question has lasted decades, and shows no sign of fading. | |||

| Contemporary Australia is also a culture that is profoundly influenced by global movements of meaning and communication, including advertising culture. In turn, globalising corporations from Holden to Exxon have attempted to associate their brand with Australian cultural identity. This process intensified from the 1970s onwards. According to ], | |||

| Finally, there is what might be termed a culturally agnostic view, which holds that endlessly debating Australian culture is futile and pointless, and that the important thing is to simply get on with living and creating it. This last viewpoint is expressed in intellectual terms from time to time, but is mostly evident in the practical activities of Australians in a wide range of fields. | |||

| {{blockquote|this consciously created interlock of the image of the multinational corporation with aspects of Australia’s national mythology, has itself over the last decade contributed to the maintenance and evolution of those national themes. But paradoxically, during the same period it has reinforced Australia’s international orientation.<ref>{{Cite journal | year= 1983 | last1= James | first1= Paul | title= Australia in the Corporate Image: A New Nationalism | url= https://www.academia.edu/33644385 | journal= Arena | issue=63 | pages= 65–106}}</ref>}} | |||

| While Australia has ubiquitous media coverage, the longest established part of that media is the ], the Federal Government funded organisation offering national TV and radio coverage. | |||

| ==Symbols== | |||

| ==="Popular culture" vs "high culture"=== | |||

| {{Main|National symbols of Australia|Australian royal symbols}} | |||

| ], Australia's floral emblem and the source of Australia's national colours, ]]] | |||

| When the Australian colonies federated on 1 January 1901, an official competition for a design for an ] was held. The design that was adopted contains the ] in the left corner, symbolising Australia's historical links to the ], the stars of the ] on the right half of the flag indicating Australia's geographical location, and the seven-pointed Federation Star in the bottom left representing the six ].<ref name= "otherflags">{{Cite web |title=Australian Flags |url=https://www.pmc.gov.au/sites/default/files/resource/download/australia-flag-booklet-fa-accessible.pdf |access-date=16 August 2024 |website=pmc.gov.au }}</ref> Other official flags include the ], the ] and the flags of the individual states and territories.<ref name= "otherflags" /><ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.itsanhonour.gov.au/symbols/otherflag.cfm |title=It's an Honour – Symbols – Other Australian Flags |access-date=30 January 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080719051017/http://itsanhonour.gov.au/symbols/otherflag.cfm |archive-date=19 July 2008 |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| The ] was granted by ] in 1912 and consists of a shield containing the badges of the six states, within an ermine border. The crest above the shield and helmet is a seven-pointed gold star on a blue and gold wreath, representing the 6 states and the territories. The shield is supported by a ] and an ], which were chosen to symbolise a nation moving forward.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Commonwealth Coat of Arms |url=https://www.pmc.gov.au/honours-and-symbols/commonwealth-coat-arms |access-date=16 August 2024 |website=www.pmc.gov.au}}</ref> | |||

| Traditional European "high culture" is little valued by most Australians, but thrives nevertheless, with excellent galleries (even in surprisingly small towns); a rich tradition in ballet, enlivened by the legacy of ] and ]; a strong national opera company based in Sydney; and good symphony orchestras in all capital cities--the ] and sometimes ] are said to be worthy of comparison with any. Despite the excellence to be found in these activities, most Australians pay them no attention. | |||

| Green and gold were confirmed as ] in 1984, though the colours had been adopted on the uniforms of Australia’s sporting teams long before this.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Australia's national colours |url=https://www.pmc.gov.au/resources/australian-symbols-booklet/national-symbols/australias-national-colours |access-date=16 August 2024 |website=www.pmc.gov.au}}</ref> The ] (''Acacia pycnantha'') was officially proclaimed as the national floral emblem in 1988.<ref>{{Cite web |last= |first= |title=Golden Wattle |url=https://www.anbg.gov.au/emblems/aust.emblem.html |access-date=16 August 2024 |website=Australian National Botanic Gardens |language=}}</ref> | |||

| In ], popular culture rules supreme: in particular the film and television industries (now both seriously threatened by proposed changes to trade laws), and the music industry, which can make at least some claim to developing an indigenous style. Until the late ], Australian popular music was barely distinguishable from imported music: British to begin with, then gradually more and more American in the post-war years. The sudden arrival of the Sixties underground movement into the mainstream in the early ] changed Australian music permanently: the ] were far from the first people to write songs in Australia, by Australians, about Australia, but they ''were'' the first ones ever to make money doing it. The two best-selling albums ever made (at that time) put Australian music on the map. Within a few years, the novelty had worn off and it became commonplace to hear distinctively Australian lyrics and sometimes sounds side-by-side with the imitators and the imports. | |||

| Reflecting the country's status as a ], ] remains part of Australian public life, maintaining a visual presence through federal and state coats of arms, ], the names and symbols of public institutions and the governor-general and state governors, who are the ] representatives on Australian soil.<ref>{{Cite thesis |title=The Crown in Australia: An anthropological study of a constitutional symbol |url=https://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz/handle/2292/30432 |publisher=The University of Auckland|date=2016 |degree= |first=S. |last=Raudon |pages=13–14 |access-date=16 August 2024}}</ref> Some ] and all ] bear an image of the ].{{efn|Historically, since the introduction of ], the lowest denomination note (] from 1966, until the note's replacement by a ] in 1984; ] since 1992) has depicted ], as have all coins until her death in 2022.<ref>{{Cite web |last= |first= |title=Queen Elizabeth II |url=https://museum.rba.gov.au/exhibitions/queen-elizabeth-ii/ |access-date=25 September 2024 |website=Reserve Bank of Australia |language=en-au}}</ref> ]'s image appeared on new $1 coins in 2023, and all new coins by 2024.<ref name="Charles on all coins"/> In 2023 the ] announced that the design of the $5 note would be updated, replacing Elizabeth with imagery that "honours the culture and history of the ]", instead of Charles.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.rba.gov.au/media-releases/2023/mr-23-02.html|title=New $5 Banknote Design|publisher=]|date=2023-02-01|access-date=2024-08-25}}</ref>}}<ref name="Charles on all coins">{{Cite news |date=2024-05-15 |title=Effigy of King Charles III now on all coins made at the Royal Australian Mint |url=https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-05-15/king-charles-australian-coins-full-set-2024/103846914 |access-date=2024-08-22 |work=ABC News |language=en-AU}}</ref> At least 14,9% of lands in Australia are referred to as ], considered ].<ref>{{Cite web |title=Who owns Australia? |url=https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/ng-interactive/2021/may/17/who-owns-australia |access-date=16 August 2024 |website=The Guardian |language=}}</ref> There are many geographic places that have been named in honour of a reigning monarch, including the states of ] and ], named after ], with numerous rivers, streets, squares, parks and buildings carrying the names of past or present members of the royal family. | |||

| ===Diversity of influences=== | |||

| ==Language== | |||

| In practice, however, it is difficult to discern much about Australian culture by examining the isolated peaks of music, dance or literature. Just as the Australian landscape is defined not by the small mountains in the south, but by the vast barren plains elsewhere, Australian culture is best defined by looking at the less prominent, by considering the more subtle and pervasive aspects. | |||

| {{Further|Languages of Australia|Australian slang|Indigenous Australian languages|Variation in Australian English}} | |||

| ], poetic humourist of ]]] | |||

| Although Australia has no official language, it is largely ] with ] being the de facto ]. ] is a major variety of the language that is immediately distinguishable from ], ], and other national dialects by virtue of its unique accents, pronunciations, idioms and vocabulary, although its spelling more closely reflects British versions rather than American. According to the 2011 census, English is the only language spoken in the home for around 80% of the population. The next most common languages spoken at home are Mandarin (1.7%), Italian (1.5%), and Arabic (1.4%); almost all migrants speak some English.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/2071.0main+features902012-2013|title=Reflecting a Nation: Stories from the 2011 Census, 2012–2013|date=21 June 2012|work=Catalogue item 2071.0|publisher=Australian Bureau of Statistics|access-date=5 June 2014}}</ref> Australia has multiple sign languages, the most spoken known as ], which in 2004 was the main language of about 6,500 deaf people,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.asliansw.org.au/work.php|title=Working with interpreters|year=2014|publisher=Australian Sign Language Interpreters' Association of NSW|access-date=5 June 2014}}</ref> and ] with about 100 speakers. | |||

| First, there is the initial European heritage, followed by an overwhelmingly city-based society that although British in origin now receives all but a small proportion of its cultural communication from either Hollywood and American TV networks, or from home-grown imitations of either of them. The ] (ABC), like the BBC in Britain, is a non-commercial public service broadcaster, showing many ] or ] productions from Britain. Debate about the role of the ABC continues, as many assign it a marginal role, and claim that American-influenced commercial TV and radio stations are far more popular choices. These critics claim that Australian children grow up watching '']'' and '']'', eating fries at ], wearing baseball caps, speaking American slang, and some have never heard of '']'' or the '']''. Television ratings are cited as backing this view, but it less clear that these ratings tell the whole view. Certainly there have been many local television shows that have been successful, such as '']'' (in the late 1960s) and '']'' and '']'' (in the 1980s and 1990s), which have sometimes been even more successful abroad. | |||

| Although it holds sway to a lesser extent than in the United States, there is a belief in Australia is that bigger is better, be it houses, often with a swimming pool in the back, or cars, such as the best selling models, ]'s ] or ]'s ]. | |||

| It is believed that there were between 200 and 300 ] at the time of first European contact, but only about 70 of these have survived and all but 20 are now endangered. An Indigenous language is the main language for 0.25% of the population.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Dalby |first=Andrew |author-link=Andrew Dalby |title=Dictionary of Languages |year=1998 |publisher=Bloomsbury Publishing plc |isbn=978-0-7475-3117-3 |page=43}}</ref> | |||

| Then there is the great post-war influx of non English-speaking migrants from the ], ], ], ], the ], and finally ]. Australia's cities are melting pots of different cultures and the influence of the longer-established southern European communities in particular has been pervasive. The publicly funded ] carries TV and radio programmes in a variety of languages, as well as world news and documentary programming in English, and is seen as less highbrow than the ABC. SBS does have a small following, having the distinction of being the TV channel most likely to show ], a minority sport in Australia. | |||

| ==Humour== | |||

| ===Myths and contradictions=== | |||

| {{Main|Australian comedy}} | |||

| ], a comic creation of ]]] | |||

| Comedy is an important part of the Australian identity. The "Australian sense of humour" is characterised as dry and sarcastic,<ref name="auhum">{{Cite web |title=Australia Explained: A guide to Aussie humour and pop culture|url=https://www.sbs.com.au/language/punjabi/en/podcast-episode/australia-explained-a-guide-to-aussie-humour-and-pop-culture/68quki512 |access-date=16 August 2024 |website=SBS Language |language=en}}</ref> exemplified by the works of performing artists like Barry Humphries and ]. | |||

| The convicts of the ] helped establish anti-authoritarianism as a hallmark of Australian comedy. Influential in the establishment of stoic, dry wit as a characteristic of Australian humour were the ]eers of the 19th century, including ], author of "]". His contemporary, ], contributed a number of classic comic poems including '']'' and '']''. ] wrote humour in the Australian vernacular – notably in '']''. The '']'' series about a farming family was an enduring hit of the early 20th century. The ] ] troops were said to often display irreverence in their relations with superior officers and dark humour in the face of battle.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Australians in France: 1918 - Friends and Foe - Australian soldiers' relations with their superiors |url=https://www.awm.gov.au/visit/exhibitions/1918/soldier/superiors |access-date=16 August 2024 |website=www.awm.gov.au}}</ref> | |||

| On top of this, are Australia's ] - shared beliefs and as such have a cultural significance quite independent of their empirical truth or falsehood. | |||

| Australians, according to myths, are relaxed, tolerant, easy-going and yet cling dearly to the fundamental importance of common-sense justice, or to use the classic expression, a "fair go". It is the land of the long weekend: a country that declares a universal holiday for a horse race, that pioneered the eight hour working day, that takes pride in never working too hard and yet idolises the "little Aussie battler" who sweats away for small reward. Australians respect "hard yakka"; to be "flat out like a lizard drinking" is to be extremely busy, or sometimes the exact opposite. Australians, according to myth, make great sportsmen and superb soldiers. To outsiders it seems quite extraordinary that a nation with several major military victories should chose to forget them and celebrate the bloody defeat of Gallipoli instead. Clearly, the myth is contradictory (as most of the best myths are). | |||

| Australian comedy has a strong tradition of self-mockery,<ref name="auhum"></ref> from the outlandish ] ''expat-in-Europe'' ] comedies of the 1970s, to the quirky outback characters of the '']'' films of the 1980s, the suburban parody of ]' 1997 film '']'' and the dysfunctional suburban mother–daughter sitcom '']''. In the 1970s, satirical talk-show host ] (played by Garry McDonald), with his ]s, sweep-over hair and poorly shaven face, rose to great popularity by pioneering the satirical "ambush" interview technique and giving unique interpretations of pop songs. ] provide an affectionate but irreverent parody of Australia's obsession with sport.{{citation needed|date=August 2020}} | |||

| Australian language is contradictory too: it combines a mocking disrespect for established authority, particularly if it is pompous or out of touch with reality, with a distinctive upside-down sense of humour: Australians take delight in dubbing a tall man "Shorty", a silent one "Rowdy" a bald man "Curly" - and a redhead, of course, is "Blue". Politicians, or "pollies", be they at state or federal level, are universally disliked and distrusted. Ironically, the failure of the ] referendum on becoming a ] was more about the prospect of a ] chosen by and from the "pollies", than about any vestigial loyalty to the ]. | |||

| The unique character and humour of Australian culture was defined in cartoons by immigrants, ] and ], and in the novel '']'' (1957) by ], which looks at Sydney through the eyes of an Italian immigrant. Post-war immigration has seen migrant humour flourish through the works of Vietnamese refugee ], Egyptian-Australian stand-up comic ] and Greek-Australian actor ].{{citation needed|date=August 2020}} | |||

| Australia's myths come from the outback, from the drovers and the squatters and the people of the barren, dusty plains, yet very few Australians little of the outback, or even of the milder countryside that is never more than an hour or two's drive from the cities that they live in. This was true even of the Australia of a century ago - since the gold rush of the 1850s, most Australians have been city-bound. Nevertheless, after a century or more spent absorbing the bush yarns of ] and the poetry of ] from the comfort of armchairs in the suburbs, the myths are real. Lawson himself - the iconic poet of the outback - was himself a city boy. | |||

| Since the 1950s, the satirical character creations of ] have included housewife "gigastar" ] and "Australian cultural attaché" ], whose interests include boozing, chasing women and flatulence.<ref></ref> For his delivery of dadaist and ] humour to millions, biographer Anne Pender described Humphries in 2010 as "the most significant comedian to emerge since ]".<ref>{{Cite web |last=Meacham |first=Steve |date=14 September 2010 |title=Absurd moments: in the frocks of the dame |url=https://www.brisbanetimes.com.au/entertainment/books/absurd-moments-in-the-frocks-of-the-dame-20100914-15ar3.html |access-date=16 August 2024 |website=Brisbane Times |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| ==Relevant articles== | |||

| *] | |||

| The vaudeville talents of ], ], ] and ] earned popular success during the early years of Australian television. The variety show '']'' screened for three decades. Among the best loved Australian sitcoms was '']'', about a divorcee who had moved back into the suburban home of his mother – but ] has been the stalwart of ]. '']'', in the 1980s, featured the comic talents of ], ], ], ], ] and others. Growing out of ] and '']'' came '']'' (1991–1993), starring the influential talents ], ], ], ], ] and ] (who later formed ]); and during the 1980s and 1990s '']'' (], ], ], ], ] and others) and its successor '']'', which launched the career of ] and featured ].{{citation needed|date=August 2020}} | |||

| *] | |||

| The perceptive wit of ] and ] has been popular in the talk-show interview style. Representatives of the "bawdy" strain of Australian comedy include ], ] and ]. ] helped defined a comic tradition in ].{{citation needed|date=August 2020}} | |||

| Cynical satire has had enduring popularity, with television series such as '']'', targeting the inner workings of "news and current affairs" TV journalism, '']'' (2008), set in the office of the Prime Minister's political advisory (spin) department, and '']'', which cynically examines domestic and international politics. Actor/writer ] has produced a series of award-winning "mockumentary" style television series about Australian characters since 2005.{{citation needed|date=August 2020}} | |||

| The annual ] is one of the largest comedy festivals in the world, and a popular fixture on the city's cultural calendar.<ref>{{Cite web |date=22 March 2005 |title=Ten years on and still laughing! The Comedy Festival and Oxfam workingto make poverty history |url=http://www.oxfam.org.au/media/article.php?id=12 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060630110150/http://www.oxfam.org.au/media/article.php?id=12 |archive-date=30 June 2006 |access-date=2024-08-30 |website=Oxfam Australia}}</ref> | |||

| ==Arts== | |||

| The ]—], ], ], ], ] and crafts—have achieved international recognition. While much of Australia's cultural output has traditionally tended to fit with general trends and styles in Western arts, the arts as practised by ] represent a unique Australian cultural tradition, and Australia's landscape and history have contributed to some unique variations in the styles inherited by Australia's various migrant communities.<ref name="painters">{{cite web | |||

| |url=http://www.cultureandrecreation.gov.au/articles/painters/ | |||

| |title=Australian painters | |||

| |work=Australian Culture and Recreation Portal | |||

| |publisher=Australia Government | |||

| |access-date=16 February 2010 | |||

| |url-status=dead | |||

| |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100205141433/http://www.cultureandrecreation.gov.au/articles/painters/ | |||

| |archive-date=5 February 2010 | |||

| }}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.cultureandrecreation.gov.au/articles/film/ |title=Film in Australia – Australia's Culture Portal |publisher=Cultureandrecreation.gov.au |access-date=29 January 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110217010927/http://www.cultureandrecreation.gov.au/articles/film/ |archive-date=17 February 2011}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.dfat.gov.au/aib/arts_culture.html |title=Australia in Brief: Culture and the arts – Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade |publisher=Dfat.gov.au |date=1 July 2008 |access-date=29 January 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101215212137/http://dfat.gov.au/aib/arts_culture.html |archive-date=15 December 2010 }}</ref> | |||

| ===Literature=== | |||

| {{Main|Australian Literature}} | |||

| As the convict era passed—captured most famously in ]'s '']'' (1874), a seminal work of ]<ref>Davidson, Jim (1989). "Tasmanian Gothic", '']'' '''48''' (2), pp. 307–324</ref>—the bush and Australian daily life assumed primacy as subjects. ], ] and ] won fame in the mid-19th century for their lyric nature poems and patriotic verse. Gordon drew on Australian colloquy and idiom; Clarke assessed his work as "the beginnings of a national school of Australian poetry".<ref>Smith, Vivian (2009). "Australian Colonial Poetry, 1788–1888". In Pierce, Peter. ''The Cambridge History of Australian Literature''. ]. pp. 73–92. {{ISBN|9780521881654}}</ref> First published in serial form in 1882, ]'s '']'' is regarded as the classic ] novel for its vivid use of the bush vernacular and realistic detail of situations in the Australian bush.<ref>{{Citation |last=Moore |first=T. Inglis |title=Thomas Alexander Browne (1826–1915) |work=Australian Dictionary of Biography |url=https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/browne-thomas-alexander-3085 |access-date=2024-08-22 |place=Canberra |publisher=National Centre of Biography, Australian National University |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| ]'', founded by ] (left), nurtured ] such as ] (right).]] | |||

| Founded in 1880, '']'' did much to create the idea of an Australian national character—one of ], ], ] and a concern for the "]"—forged against the brutalities of the bush. This image was expressed within the works of its ], the most famous of which are ], widely regarded as Australia's finest short-story writer, and ], author of classics such as "]" (1889) and "]" (1890). In ] about the nature of life in the bush, Lawson said Paterson was a romantic while Paterson attacked Lawson's pessimistic outlook.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.cultureandrecreation.gov.au/articles/lawson/ |title=Henry Lawson: Australian writer – Australia's Culture Portal |publisher=Cultureandrecreation.gov.au |date=2 September 1922 |access-date=29 January 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110408180527/http://www.cultureandrecreation.gov.au/articles/lawson/ |archive-date=8 April 2011}}</ref> ] wrote humour in the Australian vernacular, notably in the verse novel '']'' (1915), while ] wrote the iconic patriotic poem "]" (1908) which rejected prevailing fondness for England's "green and shaded lanes" and declared: "I love a sunburned country". Early Australian ] was also embedded in the bush tradition; perennial favourites include ]'s '']'' (1918), ]' '']'' (1918) and ]'s '']'' (1933). | |||

| Significant poets of the early 20th century include ], ] and ]. The nationalist ] arose in the 1930s and sought to develop a distinctive Australian poetry through the appropriation of Aboriginal languages and ideas.<ref>McGregor, Russell (2011). ''Indifferent Inclusion: Aboriginal People and the Australian Nation''. Aboriginal Studies Press. pp. 24–27. {{ISBN|9780855757793}}.</ref> In contrast, the ], centred around ]' journal of the same name, promoted international ]. A backlash resulted in the ] affair of 1943, Australia's most famous ].<ref>] (June 2002). , ''Jacket2''. Retrieved 11 March 2015.</ref> | |||

| {{multiple image | |||

| | align = left | |||

| | direction = horizontal | |||

| | header_align = center | |||

| | header = | |||

| | image1 = Miles Franklin 1901.jpg | |||

| | width1 = 170 | |||

| | alt1 = | |||

| | caption1 = ], founder and namesake of Australia's ] | |||

| | image2 = Patrick White writer.jpg | |||

| | width2 = 173 | |||

| | alt2 = | |||

| | caption2 =], winner of the first Miles Franklin Award and the ] | |||

| }} | |||

| The legacy of ], renowned for her 1901 novel '']'', is the ], which is "presented each year to a novel which is of the highest literary merit and presents Australian life in any of its phases".<ref>. Retrieved 9 December 2012.</ref> ] won the inaugural award for '']'' in 1957; he went on to win the 1973 ]. ], ] and ] are recipients of the ]. Other acclaimed Australian authors include ], ], ], ] and ]. ]'s 1977 novel '']'' is widely considered one of Australia's first contemporary novels–she has since written both fiction and non-fiction work.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/the-screen-guide/t/helen-garners-monkey-grip-2014/32187/|title=Helen Garner's Monkey Grip (2014)|date=2014|access-date=12 September 2017}}</ref> Notable expatriate authors include the feminist ] and humourist ]. Greer's controversial 1970 nonfiction book '']'' became a global bestseller and is considered a watershed ] text.<ref>{{cite web|title=The Female Eunuch|work=HarperCollins Australia|url=https://www.harpercollins.com.au/9780008436186/the-female-eunuch/|accessdate=16 January 2023}}</ref> Among the best known contemporary poets are ] and ]. | |||

| ] is known as the first Indigenous Australian author. ] was the first ] to publish a book of verse.<ref>"Oodgeroo Noonuccal." Encyclopedia of World Biography Supplement, Vol. 27. Gale, 2007</ref> A significant contemporary account of the experiences of Indigenous Australia can be found in ]'s '']''. Contemporary academics and activists including ] and ] are prominent essayists and authors on Aboriginal issues. | |||

| ] (''The Story of Anzac: From the Outbreak of War to the End of the First Phase of the Gallipoli Campaign 4 May 191''5, 1921) ] (''The Tyranny of Distance'', 1966), ] ('']'', 1987), ] ''(A History of Australia'', 1962–87), and ] (''First Australians'', 2008) are authors of important Australian histories. | |||

| ===Theatre=== | |||

| {{Main|Theatre in Australia}} | |||

| European traditions came to Australia with the ] in 1788, with the first production being performed in 1789 by convicts.<ref name="olioweb.me.uk">{{cite web|url=http://www.olioweb.me.uk/plays/ |title=Our Country's Good: The Recruiting Officer |publisher=Olioweb.me.uk |access-date=29 January 2011}}</ref> In 1988, the year of ], the circumstances of the foundations of Australian theatre were recounted in ]'s play '']''.<ref name="olioweb.me.uk"/> | |||

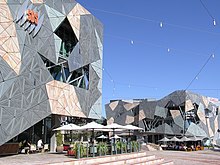

| ] in Melbourne]] | |||

| Hobart's ] opened in 1837 and is Australia's oldest continuously operating theatre.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.theatreroyal.com.au/history.html |title=a great night out! – Hobart Tasmania |publisher=Theatre Royal |access-date=29 January 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101004163331/http://www.theatreroyal.com.au/history.html |archive-date=4 October 2010 }}</ref> Inaugurated in 1839, the ] is one of Melbourne's oldest cultural institutions, and Adelaide's ], established in 1841, is today the oldest purpose-built theatre on the mainland.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.history.sa.gov.au/queens/about.htm |title=Queen's Theatre |publisher=History.sa.gov.au |date=1 July 2010 |access-date=29 January 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110221043342/http://history.sa.gov.au/queens/about.htm |archive-date=21 February 2011}}</ref> The mid-19th-century ] provided funds for the construction of grand theatres in the Victorian style, such as the ] in Melbourne, established in 1854. | |||

| After Federation in 1901, theatre productions evidenced the new sense of national identity. '']'' (1912), based on the stories of ], portrays a pioneer farming family and became immensely popular. Sydney's grand ] opened in 1928 and after restoration remains one of the nation's finest auditoriums.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.capitoltheatre.com.au/explore.htm |title= The Capitol Theatre - Sydney|website=www.capitoltheatre.com.au |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100210113100/http://www.capitoltheatre.com.au/explore.htm |archive-date=10 February 2010}}</ref> | |||

| In 1955, '']'' by ] portrayed resolutely Australian characters and went on to international acclaim. That same year, young Melbourne artist ] performed as ] for the first time at ]'s Union Theatre. His satirical stage creations, notably Dame Edna and ], became Australian cultural icons. Humphries also achieved success in the US with tours on ] and has been honored in Australia and Britain.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/6757531.stm |title=Entertainment | The man behind Dame Edna Everage |work=BBC News |date=15 June 2007 |access-date=29 January 2011}}</ref> | |||

| Founded in Sydney 1958, the ] boasts famous alumni including ], ] and ].<ref>{{cite book |last=Rawlings-Way |first=Charles |title=Sydney |publisher=] |year=2007 |page= |isbn=978-1740598392 |url=https://archive.org/details/isbn_9781741049206/page/167 }}</ref> Construction of the ] began in 1970 and South Australia's Sir ] became director of the Adelaide Festival of Arts.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.adelaidefestivalcentre.com.au/afc/history.php |title=History |publisher=Adelaide Festival Centre |date=2 June 1973 |access-date=29 January 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100529170931/http://www.adelaidefestivalcentre.com.au/afc/history.php |archive-date=29 May 2010 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.helpmannawards.com.au/default.aspx?s=sir_robert_helpmann |title=Robert Helpmann |publisher=Helpmannawards.com.au |date=28 September 1986 |access-date=29 January 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110217064310/http://helpmannawards.com.au/default.aspx?s=sir_robert_helpmann |archive-date=17 February 2011}}</ref> The new wave of Australian theatre debuted in the 1970s as “a new and more realistic look into beginnings as a nation”. It explored the confrontation in social relations, the use of vernacular language and expressions of masculine social habits in contemporary Australia.<ref>{{Cite web |title=new wave |url=https://resource.acu.edu.au/siryan/Academy/theatres/new%20wave.htm#:~:text=The%20New%20Wave%20was%20a,Jack%20Hibberd%20and%20John%20Romeril. |access-date=2024-08-30 |website=resource.acu.edu.au}}</ref> The ] presented works by ] and ]. The ], inaugurated in 1973, is the home of ] and the ]. | |||

| The ] was created in 1990. A period of success for Australian musical theatre came in the 1990s with the debut of musical biographies of Australian music singers ] ('']'' in 1998) and ] ('']''). | |||

| In ''The One Day of the Year'', ] studied the paradoxical nature of the ] commemoration by Australians of the defeat of the ]. ''Ngapartji Ngapartji'', by ] and ], recounts the story of the effects on the ] of nuclear testing in the Western Desert during the ]. It is an example of the contemporary fusion of traditions of drama in Australia with Pitjantjatjara actors being supported by a multicultural cast of Greek, Afghan, Japanese and New Zealand heritage.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Review: Ngapartji Ngapartji, Belvoir Street Theatre |url=http://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/news/review-ngapartji-ngapartji/story-e6frev39-1111115327660 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120113031144/http://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/news/review-ngapartji-ngapartji/story-e6frev39-1111115327660 |archive-date=13 January 2012 |access-date=30 August 2024 |website=dailytelegraph.com.au}}</ref> | |||

| ===Architecture=== | |||

| {{Main|Architecture of Australia|Australian architectural styles}} | |||

| ] (foreground) and ]]] | |||

| ] ] with a large veranda in ]]] | |||

| Australia has three architectural listings on ]'s ] list: ] (comprising a collection of separate sites around Australia, including ] in Sydney, ] in Tasmania, and ] in Western Australia); the ]; and the ] in Melbourne. Contemporary Australian architecture includes a number of other iconic structures, including the ] in Sydney and ]. Significant architects who have worked in Australia include Governor ]'s colonial architect, ]; the ecclesiastical architect ]; the designer of Canberra's layout, ]; the modernist ]; and ], designer of the Sydney Opera House. The ] is a non-governmental organisation charged with protecting Australia's built heritage.{{citation needed|date=August 2020}} | |||

| Evidence of permanent structures built by Indigenous Australians before European settlement of Australia in 1788 is limited. Much of what they built was temporary, and was used for housing and other needs. As a British colony, the first European buildings were derivative of the European fashions of the time. Tents and ] huts preceded more substantial structures.<ref>{{Harvnb|Clancy|pp=171}}</ref> ] is seen in early government buildings of Sydney and Tasmania and the homes of the wealthy. While the major Australian cities enjoyed the boom of the ], the ] of the mid-19th century brought major construction works and exuberant ] to the major cities, particularly Melbourne, and regional cities such as ] and ]. Other significant architectural movements in Australian architecture include the ] at the turn of the 20th century, and the modern styles of the late 20th century which also saw many older buildings demolished. The Victorian and Federation eras saw the development of the ], style of ] developed by early European migrants as a response to the new subtropical climate. The style favoured the usage of ornamental ], both for decorative and climatic cooling purposes.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Apperly |first=Richard |title=A Pictorial Guide to Identifying Australian Architecture: Styles and Terms from 1788 to the Present |last2=Irving |first2=Robert |last3=Reynolds |first3=Peter |date=1989 |publisher=Angus & Robertson |year=1989 |isbn=0-207-18562-X |pages=60-63, 108-111}}</ref> The ] developed in Queensland and the northern parts of New South Wales as a regional variation of the Filigree style, as is strongly associated with that region's iconography.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Osborne |first=Lindy |date=2014-06-17 |title=Sublime design: the Queenslander |url=https://theconversation.com/sublime-design-the-queenslander-27225 |access-date=2024-08-22 |website=The Conversation |language=en-US}}</ref> | |||

| Religious architecture is also prominent throughout Australia, with large ] and ] cathedrals in every major city and Christian churches in most towns. Notable examples include ] and ]. Other houses of worship are also common, reflecting the cultural diversity existing in Australia; the oldest Islamic structure in the Southern Hemisphere is the ] (built in the 1880s),<ref>{{cite web|url=http://recollections.nma.gov.au/issues/vol_2_no2/notes_and_comments/australias_muslim_cameleer_heritage/ |title=reCollections – Australia's Muslim cameleer heritage |publisher=Recollections.nma.gov.au |access-date=29 January 2011}}</ref> and one of the Southern Hemisphere's largest ]s is ]'s ].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.nantien.org.au/en/about/history.asp |title=Nan Tien Temple-History of Temple |publisher=Nantien.org.au |date=28 November 1991 |access-date=29 January 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110220170543/http://www.nantien.org.au/en/about/history.asp |archive-date=20 February 2011}}</ref> Sydney's ]-style ] was consecrated in 1878.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.greatsynagogue.org.au/ |title=The Great Synagogue Sydney – Home |publisher=Greatsynagogue.org.au |access-date=29 January 2011}}</ref> | |||

| ] are large and elaborate examples of High Victorian and ] styles.<ref name="Cambridge University Press">{{cite book |last1=Goad, Willis |title=The Encyclopedia of Australian Architecture |date=2012 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |pages=161}}</ref> Historically, ] have also been noted for often distinctive designs.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Leslie Johnson |first=Donald |date=December 1972 |title=Australian Architectural Histories, 1848-1968 |journal=Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians |publisher=] |volume=31 |issue=4 |page=330}}</ref> | |||

| Significant concern was raised during the 1960s, with developers threatening the destruction of historical buildings, especially in Sydney. Heritage concerns led to union-initiated '']s'', which saved significant examples of Australia's architectural past. Green bans helped to protect historic 18th-century buildings in ] from being demolished to make way for office towers, and prevented the ] from being turned into a car park for the Sydney Opera House.<ref>{{cite book|last=Mundey|first=Jack|title=Green bans and beyond|publisher=Angus and Robertson|location=Sydney|year=1981|isbn=0207143676}}</ref> | |||

| <gallery> | |||

| File:HydeParkBarracks.JPG|], Sydney | |||

| File:PortArthur main lowres.JPG|Convict architecture at ], Tasmania | |||

| File:Usydcampuspicture.jpg|The ] | |||

| File:SaintMarys CathedralSydney.jpg|Interior of ], Sydney | |||

| File:Royal exhibition building tulips straight.jpg|The ], Melbourne | |||

| File:Birdsville Hotel.jpg|] Hotel, an ] in outback Queensland | |||

| File:Parliament House Canberra Dusk Panorama.jpg|], Canberra | |||

| File:15 Northcote Avenue, Killara, New South Wales (2011-06-15).jpg|] in ], Sydney | |||

| File:Queenslander East Brisbane 1a.jpg|A typical ] house in Brisbane | |||

| File:(1)Killara house 023.jpg|House in ] | |||

| File:Imperial-hotel-ravenswood-outback-queensland-australia.JPG|The ] is the dominant feature of this ] pub in ]. | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| ===Visual arts=== | |||

| {{Main|Visual arts of Australia}} | |||

| {{See also|Indigenous Australian art}} | |||

| {{Multiple image | |||

| | align = left | |||

| | direction = vertical | |||

| | width = 170 | |||

| | image1 = Bradshaw rock paintings2.jpg | |||

| | caption1 = ] in the ] region of Western Australia | |||

| | image2 = Sunbaker maxdupain nga76.54.jpg | |||

| | caption2 = '']'' (1937), an iconic photograph by ] | |||

| }} | |||

| Aboriginal ] is the oldest continuous art tradition in the world, dating as far back as 60,000 years. From the ] and ] imagery in the ] to the ], it is spread across hundreds of thousands of sites, making Australia the richest continent in terms of ].<ref>Taçon, Paul S. C. (2001). "Australia". In Whitely, David S.. ''Handbook of Rock Art Research''. ]. pp. 531–575. {{ISBN|978-0-7425025-6-7}}</ref> 19th-century Indigenous activist ] painted ceremonial scenes, such as ]s.<ref>Sayers, Andrew. ''Aboriginal artists of the nineteenth century''. Oxford University Press, 1994. {{ISBN|0-19-553392-5}}, p. 6</ref> The ], led by ], received national fame in the 1950s for their desert ]s.<ref>, Hermannsburg School. Retrieved 9 December 2012.</ref> Leading critic ] saw ] as "the last great art movement of the 20th century".<ref>Henly, Susan Gough (6 November 2005). , '']''. Retrieved 20 November 2012.</ref> Key exponents such as ], ] and the ] group use acrylic paints on canvas to depict ]s set in a symbolic topography. ]'s '']'' (1977) typifies this style, popularly known as "]". Art is important both culturally and economically to Indigenous society; central Australian Indigenous communities have "the highest per capita concentrations of artists anywhere in the world".<ref>{{cite news|title=Next generation Papunya|last=Grishin|first=Sasha|date=8 December 2007|work=The Canberra Times|page=6}}</ref> Issues of race and identity are raised in the works of many ] Indigenous artists, including ] and ]. | |||

| {{Multiple image | |||

| | align = right | |||

| | direction = vertical | |||

| | width = 220 | |||

| | image1 = Tom Roberts - Shearing the rams - Google Art Project.jpg | |||

| | caption1 = '']'' (1890) by ] artist ] | |||

| | image2 = Sidney Nolan Snake.jpg | |||

| | caption2 = ]'s ''Snake'' (1972), held at the ] | |||

| | image3 = | |||

| | caption3 = '']'' heralded Melbourne as the "street art capital of the world".<ref name="streetart">Freeman-Greene, Suzy (26 February 2011). , ''The Age''. Retrieved 20 November 2012.</ref> | |||

| }} | |||

| ] and ] were among the foremost landscape painters during the colonial era.<ref>Copeland, Julie (1998). , ''Headspace'' '''2'''. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 8 December 2012.</ref> The origins of a distinctly Australian school of painting is often associated with the ] of the late 1800s.<ref name="ausart"/> Major figures of the movement include ], ] and ]. They painted '']'', like the ], and sought to capture the intense light and unique colours of the Australian bush. Popular works such as McCubbin's '']'' (1889) and Roberts' '']'' (1890) defined an emerging sense of national identity in the lead-up to Federation.<ref>, National Gallery of Victoria. Retrieved 18 November 2012.</ref> Civic monuments to national heroes were erected; an early example is ]' 1865 statue of the ill-fated explorers ], located in Melbourne.<ref>Williams, Donald. ''In Our Own Image: The Story of Australian Art''. Melbourne: ], 2002. {{ISBN|0-07-471030-3}}, pp. 42–43</ref> | |||

| Among the first Australian artists to gain a reputation overseas was the impressionist ] in the 1880s. He and ] of the Heidelberg School were the only Australian painters known to have close links with the European ] at the time.<ref>]. ''The Art of Australia''. Melbourne: ], 1970. {{ISBN|0-87585-103-7}}, p. 93</ref> Other notable expatriates include ], a ] painter of sensual portraits, and sculptor ], known for his commissioned works in Australia and abroad.<ref name="ausart"/> | |||

| The Heidelberg tradition lived on in ]'s imagery of gum trees.<ref>Hylton, Jane; ]. ''Hans Heysen: Into the Light''. Adelaide: Wakefield Press, 2004. {{ISBN|1-86254-657-6}}, p. 12</ref> ] and ] were pioneers of ] in Australia.<ref>]. ''The Black Swan of Trespass: The Emergence of Modernist Painting in Australia to 1944''. Sydney: Alternative Publishing, 1979. {{ISBN|0-909188-12-2}}, p. 4</ref> ] and ] excelled at printmaking;<ref>{{cite book|last=Butler|first=Roger|title=Printed. Images by Australian Artists 1885–1955|publisher=National Gallery of Australia|location=Canberra, ACT|year=2007|isbn=978-0642-54204-5|page=90}}</ref> the latter artist advocated for a modern national art based on Aboriginal designs.<ref>]. ''Transformations in Australian Art, Volume 2: The 20th Century – Modernism and Aboriginality''. Sydney: Craftsman House, 2002. {{ISBN|1-877004-14-6}}, p. 8</ref> The conservative art establishment largely opposed modern art, as did the Lindsays and ].<ref>Williams, John Frank. ''The Quarantined Culture: Australian Reactions to Modernism, 1913–1939''. ], 1995. {{ISBN|0-521-47713-1}}, pp. 1–14</ref> Controversy over modern art in Australia reached a climax when ] won the 1943 ] for portraiture.<ref>, Art Gallery of New South Wales. Retrieved 18 November 2012.</ref> Despite such opposition, new artistic trends grew in popularity. Photographer ] created bold modernist compositions of Sydney beach culture.<ref>White, Jill. ''Dupain's Beaches''. Sydney: Chapter & Verse, 2000. {{ISBN|978-0-947322-17-5}}</ref> ], ], ] and ] were members of the ], a group of ]s who revived Australian landscape painting through the use of myth, folklore and personal symbolism.<ref>Haese, Richard. ''Rebels and Precursors: The Revolutionary Years of Australian Art''. Melbourne: Penguin Books, 1988. {{ISBN|0-14-010634-0}}</ref> The use of ] allowed artists to evoke the strange disquiet of the outback, exemplified in Nolan's iconic ] series and ]'s '']'' (1948). The post-war landscapes of ], ] and ] border on ],<ref name="ausart">, Art Gallery of New South Wales. Retrieved 20 November 2012.</ref> while the ] and ] further explored the possibilities of figurative painting. | |||

| Photographer ], sculptor ], and "living art exhibit" ] are among Australia's best-known contemporary artists. ]'s output of ], ]'s poetic cartoons, and ]'s Sydney Harbor views are widely known through reproductions. ]works have sprung up in unlikely places, from the annual ] exhibitions to the rural ] of "]". Australian ] flourished at the turn of the 21st century, ].<ref name="streetart"/> | |||

| Major arts institutions in Australia include the ] in Melbourne, the ], ] and ] in Canberra, and the ] in Sydney. The ] in Hobart is the Southern Hemisphere's largest private museum.<ref> (27 January 2011), '']''. Retrieved 14 December 2012.</ref> | |||

| ===Cinema=== | |||

| {{Main|Cinema of Australia}} | |||

| ] in '']'' (1906), the world's first ]]] | |||

| Australia's first dedicated film studio, the ], was created by ] in Melbourne in 1898, and is believed to be the world's first.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.salvationarmy.org.au/SALV/STANDARD/PC_60860.html |title=Australia's first film studio |publisher=Salvationarmy.org.au |date=15 January 2010 |access-date=29 January 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20091030184703/http://salvationarmy.org.au/SALV/STANDARD/PC_60860.html |archive-date=30 October 2009 }}</ref> The world's first feature-length film was the 1906 Australian production '']''.<ref>, ]. Retrieved 27 November 2012.</ref> Tales of ], gold mining, convict life and the colonial frontier dominated the ]. Filmmakers such as ] and ] based many of their productions on Australian novels, plays, and even paintings. An enduring classic is Longford and ]'s 1919 film '']'', adapted from ] by C. J. Dennis. After such early successes, Australian cinema suffered from the rise of ].<ref>Routt, William D. "Chapter 3: Our reflections in a window: Australian silent cinema (c. 1896–1930)". In Sabine, James. ''A Century of Australian Cinema''. Melbourne: ], 1995. {{ISBN|0-85561-610-5}}, pp. 44–63</ref> | |||

| In 1933, '']'' was directed by ], who cast ] as the leading actor.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://aso.gov.au/titles/features/wake-bounty/ |title=In the Wake of the Bounty (1933) on ASO – Australia's audio and visual heritage online |publisher=Aso.gov.au |access-date=29 January 2011}}</ref> Flynn went on to a celebrated career in Hollywood. Chauvel directed a number of successful Australian films, the last being 1955's '']'', which was notable for being the first Australian film to be shot in colour, and the first to feature Aboriginal actors in lead roles and to be entered at the Cannes Film Festival.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.festival-cannes.com/en/archives/ficheFilm/id/3702/year/1955.html |title=Festival de Cannes – From 11 to 22 may 2011 |publisher=Festival-cannes.com |access-date=29 January 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120118215228/http://www.festival-cannes.com/en/archives/ficheFilm/id/3702/year/1955.html |archive-date=18 January 2012}}</ref> It was not until 2006 and ]'s '']'' that a major feature-length drama was shot in an Indigenous language (]). | |||

| ]'s 1942 documentary feature '']'' was the first Australian film to win an ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://aso.gov.au/titles/newsreels/kokoda-front-line/ |title=Kokoda Front Line! (1942) on ASO – Australia's audio and visual heritage online |publisher=Aso.gov.au |access-date=29 January 2011}}</ref> In 1976, ] posthumously became the first Australian actor to win an Oscar for his role in '']''.<ref>{{cite web |title=Peter Finch – About This Person | url=https://movies.nytimes.com/person/23460/Peter-Finch?inline=nyt-per| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110413161443/http://movies.nytimes.com/person/23460/Peter-Finch?inline=nyt-per| url-status=dead| archive-date=13 April 2011|department=Movies & TV Dept. |work=] |date=2011 | access-date=24 December 2012}}</ref> | |||

| During the late 1960s and 1970s an influx of government funding saw the development of a new generation of filmmakers telling distinctively Australian stories, including directors ], ] and ]. This era became known as the ]. Films such as '']'', '']'' and '']'' had an immediate international impact. These successes were followed in the 1980s with the historical epic '']'', the romantic drama '']'', the comedy '']'', and the post-apocalyptic ].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://wwwmcc.murdoch.edu.au/ReadingRoom/film/Croc.html |title="Fair Dinkum Fillums": the Crocodile Dundee Phenomenon |publisher=Cc.murdoch.edu.au |access-date=29 January 2011 |archive-date=12 April 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200412042204/http://wwwmcc.murdoch.edu.au/ReadingRoom/film/Croc.html |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| ] is the world's largest short film festival.]] | |||

| The 1990s saw a run of successful comedies including '']'' and '']'', which helped launch the careers of ] and ] respectively. ] features prominently in Australian film, with a strong tradition of self-mockery, from the '']'' style of the ] ''expat-in-Europe'' movies of the 1970s, to the ]' 1997 homage to suburbia '']'', starring ] in his debut film role. Comedies like the barn yard animation '']'' (1995), directed by ]; ]'s '']'' (2000); and ]'s '']'' (1994) all feature in the top ten box-office list.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.australiamovie.net/2009/02/second-highest-grossing-australian-film-of-all-time/ |title=AUSTRALIA - A Baz Luhrmann Film » Second Highest Grossing Australian Film of All Time |access-date=29 March 2010 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100324201044/http://www.australiamovie.net/2009/02/second-highest-grossing-australian-film-of-all-time/ |archive-date=24 March 2010}}</ref> During the 1990s, a new crop of Australian stars were successful in Hollywood, including ], ] and ]. Between 1996 and 2013, ] won four ] for her costume and production designs, the most for any Australian.<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/movies/catherine-martin-breaks-record-with-fourth-oscar-win-20140303-33yjz.html|title=Catherine Martin breaks record with fourth Oscar win|last=Maddox|first=Garry|date=3 March 2014|work=Sydney Morning Herald|access-date=3 May 2014}}</ref> '']'' (2004) and '']'' (2005) are credited with the revival of Australian horror.<ref> (5 November 2008), ''The Courier Mail''. Retrieved 31 December 2012.</ref> The comedic, exploitative nature and "]y" style of 1970s Ozploitation films waned in the mid to late 1980s, as social ] dramas such as '']'' (1992), '']'' (2001) and '']'' (2009) became more reflective of the Australian experience in the 1980s, 90s and 2000s. | |||

| The domestic film industry is also supported by US producers who produce in Australia following the decision by Fox head ] to utilise new studios in Melbourne and Sydney where filming could be completed well below US costs. Notable productions include '']'', '']'' episodes ] and ], and '']'' starring ] and ]. | |||

| ===Music=== | |||

| {{Main|Music of Australia}} | |||

| ====Indigenous music==== | |||

| {{Main|Indigenous Australian music}} | |||

| ] performers]] | |||

| Music is an integral part of Aboriginal culture as a way of passing ancestral knowledge, cultural values and wisdom through generations.<ref>{{Cite web |date=2016-07-08 |title=Songlines: the Indigenous memory code |url=https://www.abc.net.au/listen/programs/allinthemind/songlines-indigenous-memory-code/7581788 |access-date=2024-08-17 |website=ABC listen |language=en-AU}}</ref> The most famous feature of their music is the ]. This wooden instrument, used among the Aboriginal tribes of northern Australia, makes a distinctive droning sound and it has been adopted by a wide variety of non-Aboriginal performers. | |||

| Since the 1980s, Indigenous music has experienced a "cultural renaissance", turning to Western popular musical forms and "demand a space within the Australian arts industry".<ref>{{Cite web |last=Jahudka |first=Ines |date=31 May 2021 |title=Baker Boy and beyond: the Aboriginal 'Cultural Renaissance' of the 1980s and Australia's view of Indigenous music |url=https://chariotjournal.wordpress.com/2021/05/31/baker-boy-and-beyond/ |access-date=17 August 2024 |website=Chariot Journal |language=en}}</ref> Pioneers include ] and ], while notable contemporary examples include ], ], the ], ] and ]. ] (formerly of Yothu Yindi) has attained international success singing contemporary music in English and in the language of the ]. ] is a successful ] singer. Among young Australian aborigines, ] and Aboriginal ] music and clothing is popular.<ref>{{cite news | |||

| | title = The New Corroboree | |||

| | first = Tony | |||

| | last = Mitchell | |||

| | url = http://www.theage.com.au/news/music/the-new-corroboree/2006/03/30/1143441270792.html | |||

| | newspaper = ] | |||

| | date = 1 April 2006 | |||

| | location=Melbourne | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| The ] are an annual celebration of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander achievement in music, sport, entertainment and community. | |||

| ====Folk music and national songs==== | |||

| ]'s 1905 collection of ]s]] | |||

| The ] of Australia is "]".<ref>{{Cite web |title=Australian National Anthem |url=https://www.pmc.gov.au/government/australian-national-anthem |access-date=2022-06-01 |website=Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet}}</ref> | |||

| The early ] immigrants of the 18th and 19th centuries introduced folk ballad traditions which were adapted to Australian themes: "]" tells of the voyage of British convicts to Sydney, "]" evokes the spirit of the bushrangers, and "]" speaks of the life of Australian shearers. The lyrics of Australia's best-known folk song, "]", were written by the bush poet Banjo Paterson in 1895. This song remains popular and is regarded as "the nation's unofficial national anthem".<ref>, National Library of Australia. Retrieved 24 December 2012.</ref> | |||