| Revision as of 12:29, 1 November 2024 editPhlsph7 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users15,840 edits →Sources: add sources← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 11:16, 4 January 2025 edit undoPhlsph7 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users15,840 edits →Sources: add source | ||

| (42 intermediate revisions by 7 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description| |

{{Short description|Family of views prioritizing pleasure}} | ||

| {{Other uses}} | {{Other uses}} | ||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=January 2021}} | {{Use dmy dates|date=January 2021}} | ||

| {{Hedonism|expanded=all}} | |||

| '''Hedonism''' is a family of philosophical views that prioritize ]. '''Psychological hedonism''' is the theory that the underlying ] of all human behavior is to maximize pleasure and avoid ]. As a form of ], it suggests that people only help others if they expect a personal benefit. '''Axiological hedonism''' is the view that pleasure is the sole source of ]. It asserts that other things, like knowledge and money, only have value insofar as they produce pleasure and reduce pain. This view divides into quantitative hedonism, which only considers the intensity and duration of pleasures, and qualitative hedonism, which holds that the value of pleasures also depends on their quality. The closely related position of '''prudential hedonism''' states that pleasure and pain are the only factors of ]. '''Ethical hedonism''' applies axiological hedonism to ], arguing that people have a ] to pursue pleasure and avoid pain. ] versions assert that the goal is to increase overall happiness for everyone, whereas ] versions state that each person should only pursue their own pleasure. Outside the academic context, ''hedonism'' is a pejorative term for an egoistic lifestyle seeking short-term gratification. | |||

| '''Hedonism''' refers to the prioritization of ] in one's lifestyle, actions, or thoughts. The term can include a number of theories or practices across ], ], and ], encompassing both sensory pleasure and more intellectual or personal pursuits, but can also be used in everyday parlance as a pejorative for the ] pursuit of short-term gratification at the expense of others.{{sfn|Weijers}}<ref>{{cite web |title=Hedonism |url=https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/hedonism#note-1 |website=www.merriam-webster.com |access-date=30 January 2021 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| Hedonists typically understand pleasure and pain broadly to include ]. While traditionally seen as bodily sensations, contemporary philosophers tend to view them as attitudes of attraction or aversion toward objects. Hedonists often use the term '']'' for the balance of pleasure over pain. The ] nature of these phenomena makes it difficult to measure this balance and compare it between different people. The ] and the ] are proposed psychological barriers to the hedonist goal of long-term happiness. | |||

| The term originates in ], where '''axiological''' or '''value hedonism''' is the claim that pleasure is the ] of ],{{sfn|Moore|2019}}<ref>{{cite web |title=Psychological hedonism |url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/psychological-hedonism |website=Encyclopedia Britannica |access-date=29 January 2021 |language=en}}</ref><ref name="Haybron">{{cite book |last1=Haybron |first1=Daniel M. |title=The Pursuit of Unhappiness: The Elusive Psychology of Well-Being |year=2008 |publisher=] |page=62 |url=https://philpapers.org/rec/HAYTPO-8}}</ref> while '''normative''' or '''ethical hedonism''' claims that pursuing pleasure and avoiding pain for oneself or others are the ultimate expressions of ethical good.{{sfn|Weijers}} Applied to ] or what is good for someone, it is the thesis that pleasure and suffering are the only components of well-being.<ref name="Crisp">{{cite web |last1=Crisp |first1=Roger |title=Well-Being: 4.1 Hedonism |url=https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/well-being/#Hed |website=The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy |publisher=Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University |date=2017}}</ref> | |||

| As one of the oldest philosophical theories, hedonism was discussed by the ] and ] in ], the ] school in ], and ] in ]. It attracted less attention in the ] but became a central topic in the ] with the rise of utilitarianism. Various criticisms of hedonism emerged in the 20th century, while its proponents suggested new versions to meet these challenges. Hedonism remains relevant to many fields, ranging from ] and ] to ]. | |||

| '''Psychological''' or '''motivational hedonism''' claims that ] is psychologically determined by desires to increase pleasure and to decrease ].{{sfn|Moore|2019}}{{sfn|Weijers}} | |||

| == Types == | == Types == | ||

| The term ''hedonism'' refers not to a single theory but to a family of theories about the role of ]. These theories are often categorized into ], ], and ] hedonism depending on whether they study the relation between pleasure and ], ], or right action.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Weijers|loc=Lead section}} | {{harvnb|Bruton|2024}} | {{harvnb|Tilley|2012|loc=Lead section}} }}</ref> While these distinctions are common in contemporary philosophy, earlier philosophers did not always clearly differentiate between them and sometimes combined several views in their theories.<ref>{{harvnb|Gosling|1998|loc=§ 2. Psychological, Evaluative and Reflective Hedonism}}</ref> | The term ''hedonism'' refers not to a single theory but to a family of theories about the role of ]. These theories are often categorized into ], ], and ] hedonism depending on whether they study the relation between pleasure and ], ], or right action.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Weijers|loc=Lead section}} | {{harvnb|Bruton|2024}} | {{harvnb|Tilley|2012|loc=Lead section}} }}</ref> While these distinctions are common in contemporary philosophy, earlier philosophers did not always clearly differentiate between them and sometimes combined several views in their theories.<ref>{{harvnb|Gosling|1998|loc=§ 2. Psychological, Evaluative and Reflective Hedonism}}</ref> The word ''hedonism'' derives from the ] word {{lang|grc|ἡδονή}} ({{transl|grc|]}}), meaning {{gloss|pleasure}}.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Hoad|1993|p=213}} | {{harvnb|Cresswell|2021|loc=§ Epicure}} }}</ref> Its earliest known use in the English language is from the 1850s.<ref>{{harvnb|Oxford University Press|2024}}</ref> | ||

| === Psychological hedonism === | === Psychological hedonism === | ||

| ] was a key advocate of psychological hedonism.<ref name="auto3">{{multiref | {{harvnb|Blakemore|Jennett|2001|loc=§ Pleasure and the Enlightenment}} | {{harvnb|Schmitter|2021|loc=§ 3. The Classification of the Passions}} | {{harvnb|Abizadeh|2018|p=}} }}</ref>]] | |||

| Psychological or motivational hedonism is the view that all human actions aim at increasing pleasure and avoiding ]. It is an empirical view about what motivates people, both on the conscious and the unconscious levels.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Weijers|loc=§ 1c. Motivational Hedonism}} | {{harvnb|Buscicchi|loc=§ 2. Paradoxes of Hedonism}} | {{harvnb|Bruton|2024}} | {{harvnb|Tilley|2012|loc=§ IV. Psychological Hedonism}} }}</ref> Psychological hedonism is usually understood as a form of ], meaning that people strive to increase their own happiness. This implies that a person is only motivated to help others if it is in their ] because they expect a personal benefit from it.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Bruton|2024}} | {{harvnb|Gosling|2001|p=1326}} | {{harvnb|Tilley|2012|loc=§ IV. Psychological Hedonism}} }}</ref> As a theory of human motivation, psychological hedonism does not imply that all behavior leads to pleasure. For example, if a person holds mistaken beliefs or lacks necessary skills, they may attempt to produce pleasure but fail to attain the intended outcome.<ref>{{harvnb|Bruton|2024}}</ref> | Psychological or motivational hedonism is the view that all human actions aim at increasing pleasure and avoiding ]. It is an empirical view about what motivates people, both on the conscious and the unconscious levels.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Weijers|loc=§ 1c. Motivational Hedonism}} | {{harvnb|Buscicchi|loc=§ 2. Paradoxes of Hedonism}} | {{harvnb|Bruton|2024}} | {{harvnb|Tilley|2012|loc=§ IV. Psychological Hedonism}} }}</ref> Psychological hedonism is usually understood as a form of ], meaning that people strive to increase their own happiness. This implies that a person is only motivated to help others if it is in their ] because they expect a personal benefit from it.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Bruton|2024}} | {{harvnb|Gosling|2001|p=1326}} | {{harvnb|Tilley|2012|loc=§ IV. Psychological Hedonism}} }}</ref> As a theory of human motivation, psychological hedonism does not imply that all behavior leads to pleasure. For example, if a person holds mistaken beliefs or lacks necessary skills, they may attempt to produce pleasure but fail to attain the intended outcome.<ref>{{harvnb|Bruton|2024}}</ref> | ||

| The standard form of psychological hedonism asserts that the pursuit of pleasure and the avoidance of pain are the only sources of all motivation. Some psychological hedonists propose weaker formulations, suggesting that considerations of pleasure and pain influence most actions to some extent or limiting |

The standard form of psychological hedonism asserts that the pursuit of pleasure and the avoidance of pain are the only sources of all motivation. Some psychological hedonists propose weaker formulations, suggesting that considerations of pleasure and pain influence most actions to some extent or limiting their role to certain conditions.<ref>{{harvnb|Weijers|loc=§ 1c. Motivational Hedonism}}</ref> For example, reflective or rationalizing hedonism says that human motivation is only driven by pleasure and pain when people actively reflect on the overall consequences.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Gosling|1998|loc=§ 2. Psychological, Evaluative and Reflective Hedonism}} | {{harvnb|Gosling|2001|p=1326}} | {{harvnb|Gosling|2005|pp=363–364}} }}</ref> Another version is genetic hedonism, which accepts that people desire various things besides pleasure but asserts that each desire has its origin in a desire for pleasure.<ref>{{harvnb|Tilley|2012|loc=§ IV. Psychological Hedonism}}</ref> | ||

| Proponents of psychological hedonism often highlight its intuitive appeal and explanatory power, arguing that many desires directly focus on pleasure while the others have an indirect focus by aiming at the means to bring about pleasure.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Heathwood|2013|loc=§ Why Think Hedonism Is True?}} | {{harvnb|Moore|2019|loc=§ 1.1 Arguments For Psychological Hedonism}} }}</ref> Critics of psychological hedonism often cite apparent counterexamples in which people act for reasons other than their personal pleasure. Proposed examples include acts of genuine ], such as a soldier sacrificing themselves on the battlefield to save their comrades or a parent wanting their |

Proponents of psychological hedonism often highlight its intuitive appeal and explanatory power, arguing that many desires directly focus on pleasure while the others have an indirect focus by aiming at the means to bring about pleasure.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Heathwood|2013|loc=§ Why Think Hedonism Is True?}} | {{harvnb|Moore|2019|loc=§ 1.1 Arguments For Psychological Hedonism}} }}</ref> Critics of psychological hedonism often cite apparent counterexamples in which people act for reasons other than their personal pleasure. Proposed examples include acts of genuine ], such as a soldier sacrificing themselves on the battlefield to save their comrades or a parent wanting their children to be happy. Critics also mention non-altruistic cases, like a desire for ]. It is an open question to what extent these cases can be explained as types of pleasure-seeking behavior.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Gosling|2001|p=1326}} | {{harvnb|Gosling|1998|loc=§ 2. Psychological, Evaluative and Reflective Hedonism}} | {{harvnb|Bruton|2024}} | {{harvnb|Heathwood|2013|loc=§ Why Think Hedonism Is True?}} }}</ref> | ||

| === Axiological hedonism === | === Axiological hedonism === | ||

| Axiological or evaluative hedonism is the view that pleasure is the sole source of ]. An entity has intrinsic value or is good in itself if its worth does not depend on external factors. Intrinsic value contrasts with ], which is the value of things that lead to other good things. According to axiological hedonism, pleasure is intrinsically valuable because it is good even when it produces no external benefit. Money, by contrast, is only instrumentally good because it can be used to obtain other good things but lacks value apart from these uses. Axiological hedonism asserts that only pleasure has intrinsic value whereas other things only have instrumental value to the extent that they lead to pleasure or the avoidance of pain.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Weijers|loc=§ 1b. Value Hedonism and Prudential Hedonism}} | {{harvnb|Tilley|2012|loc=§ III. Axiological Hedonism}} }}</ref> The overall value of a thing depends on both its intrinsic and instrumental value. In some cases, even unpleasant things, like a painful surgery, can be overall good, according to axiological hedonism, if their positive consequences make up for the unpleasantness.<ref>{{harvnb|Tilley|2012|loc=§ III. Axiological Hedonism}}</ref> | Axiological or evaluative hedonism is the view that pleasure is the sole source of ]. An entity has intrinsic value or is good in itself if its worth does not depend on external factors. Intrinsic value contrasts with ], which is the value of things that lead to other good things. According to axiological hedonism, pleasure is intrinsically valuable because it is good even when it produces no external benefit. Money, by contrast, is only instrumentally good because it can be used to obtain other good things but lacks value apart from these uses. Axiological hedonism asserts that only pleasure has intrinsic value whereas other things only have instrumental value to the extent that they lead to pleasure or the avoidance of pain.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Weijers|loc=§ 1b. Value Hedonism and Prudential Hedonism}} | {{harvnb|Tilley|2012|loc=§ III. Axiological Hedonism}} }}</ref> The overall value of a thing depends on both its intrinsic and instrumental value. In some cases, even unpleasant things, like a painful surgery, can be overall good, according to axiological hedonism, if their positive consequences make up for the unpleasantness.<ref name="auto1">{{harvnb|Tilley|2012|loc=§ III. Axiological Hedonism}}</ref> | ||

| Prudential hedonism is a form of axiological hedonism that focuses specifically ] or what is good for an individual. It states that pleasure and pain are the sole factors of well-being, meaning that how good a life is for a person only depends on its balance of pleasure over pain. Prudential hedonism allows for the possibility that other things than well-being have intrinsic value, such as beauty or freedom.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Weijers|loc=§ 1b. Value Hedonism and Prudential Hedonism}} | {{harvnb|de Bres|2014|loc=}} }}</ref> |

Prudential hedonism is a form of axiological hedonism that focuses specifically ] or what is good for an individual. It states that pleasure and pain are the sole factors of well-being, meaning that how good a life is for a person only depends on its balance of pleasure over pain. Prudential hedonism allows for the possibility that other things than well-being have intrinsic value, such as beauty or freedom.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Weijers|loc=§ 1b. Value Hedonism and Prudential Hedonism}} | {{harvnb|de Bres|2014|loc=}} }}</ref> | ||

| According to quantitative hedonism, the intrinsic value of pleasure depends solely on its intensity and duration. Qualitative hedonists hold that the quality of pleasure is an additional factor. They argue, for instance, that subtle pleasures of the mind, like the enjoyment of fine art and philosophy, can be more valuable than simple bodily pleasures, like enjoying food and drink, even if their intensity is lower.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Tilley|2012|loc=§ III. Axiological Hedonism}} | {{harvnb|Heathwood|2013|loc=§ What Determines the Intrinsic Value of a Pleasure or a Pain?}} }}</ref> | According to quantitative hedonism, the intrinsic value of pleasure depends solely on its intensity and duration. Qualitative hedonists hold that the quality of pleasure is an additional factor. They argue, for instance, that subtle pleasures of the mind, like the enjoyment of fine art and philosophy, can be more valuable than simple bodily pleasures, like enjoying food and drink, even if their intensity is lower.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Tilley|2012|loc=§ III. Axiological Hedonism}} | {{harvnb|Heathwood|2013|loc=§ What Determines the Intrinsic Value of a Pleasure or a Pain?}} }}</ref> | ||

| Proponents of axiological hedonism often focus on intuitions about the relation between pleasure and value or on the observation that pleasure is desirable.<ref |

]'s ] is an influential ] against hedonism.<ref name="auto4">{{multiref | {{harvnb|Heathwood|2015|pp=}} | {{harvnb|Tiberius|2015|pp=}} }}</ref>]] | ||

| Proponents of axiological hedonism often focus on intuitions about the relation between pleasure and value or on the observation that pleasure is desirable.<ref name="auto1"/> The idea that most pleasures are valuable in some form is relatively uncontroversial. However, the stronger claim that all pleasures are valuable and that they are the only source of intrinsic value is subject to debate.<ref>{{harvnb|Weijers|loc=Lead section}}</ref> Some critics assert that certain pleasures are worthless or even bad, like disgraceful and ] pleasures.<ref>{{harvnb|Feldman|2004|pp=38–39}}</ref>{{efn|A more controversial objection asserts that all pleasures are bad.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Vogt|2018|p=}} | {{harvnb|Aufderheide|2020|p=}} }}</ref>}} A different criticism comes from ], who contend that other things besides pleasure have value. To support the idea that ] is an additional source of value, ] used a ] involving two worlds: one exceedingly beautiful and the other a heap of filth. He argued that the beautiful world is better even if there is no one to enjoy it.<ref>{{harvnb|Feldman|2004|pp=51–52}}</ref> Another influential thought experiment, proposed by ], involves an ] able to create artificial pleasures. Based on his observation that most people would not want to spend the rest of their lives in this type of pleasant illusion, he argued that hedonism cannot account for the values of authenticity and genuine experience.<ref name="auto4"/>{{efn|Another historically influential argument, first formulated by Socrates, suggests that a pleasurable life void of any higher ] processes, like the life of a happy ], is not the best form of life.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Weijers|loc=§ 2d. The Oyster Example}} | {{harvnb|Feldman|2004|pp=43–44}} }}</ref>}} | |||

| === Ethical hedonism === | === Ethical hedonism === | ||

| ] developed a nuanced form of ethical hedonism, arguing that a ] cultivated through moderation leads to the greatest overall happiness.<ref name="auto2">{{multiref | {{harvnb|Feldman|2001|pp=}} | {{harvnb|Weijers|loc=§ 2c. Epicurus}} }}</ref>]] | |||

| Ethical or ] hedonism is the thesis that the pursuit of pleasure and the avoidance of pain are the highest ] principles of human behavior.{{efn|Some definitions do not distinguish between ethical and axiological hedonism, and define ethical hedonism in terms of intrinsic values rather than right action.<ref>{{harvnb|Moore|2019|loc=Lead section, § 2. Ethical Hedonism}}</ref>}} It implies that other moral considerations, like ], ], or ], are relevant only to the extent that they influence pleasure and pain.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Weijers|loc=Lead section}} | {{harvnb|Tilley|2012|loc=§ II. Ethical Hedonism}} }}</ref> | Ethical or ] hedonism is the thesis that the pursuit of pleasure and the avoidance of pain are the highest ] principles of human behavior.{{efn|Some definitions do not distinguish between ethical and axiological hedonism, and define ethical hedonism in terms of intrinsic values rather than right action.<ref>{{harvnb|Moore|2019|loc=Lead section, § 2. Ethical Hedonism}}</ref>}} It implies that other moral considerations, like ], ], or ], are relevant only to the extent that they influence pleasure and pain.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Weijers|loc=Lead section}} | {{harvnb|Tilley|2012|loc=§ II. Ethical Hedonism}} }}</ref> | ||

| Theories of ethical hedonism can be divided into egoistic and ] theories. Egoistic hedonism says that each person should only pursue their own pleasure. According to this controversial view, a person only has a moral reason to care about the happiness of others if this happiness impacts their own well-being. For example, if a person |

Theories of ethical hedonism can be divided into egoistic and ] theories. Egoistic hedonism says that each person should only pursue their own pleasure. According to this controversial view, a person only has a moral reason to care about the happiness of others if this happiness impacts their own well-being. For example, if a person feels guilty about harming others, they have a reason not to do so. However, a person would be free to harm others, and would even be morally required to, if they overall benefit from it.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Weijers|loc=§ 1d. Normative Hedonism, § 1e. Hedonistic Egoism}} | {{harvnb|Tilley|2012|loc=§ II. Ethical Hedonism}} }}</ref> | ||

| Utilitarian hedonism, also called ''classical utilitarianism'', asserts that everyone's happiness matters. It says that a person should maximize the sum total of happiness of everybody affected by their actions. This sum |

Utilitarian hedonism, also called ''classical utilitarianism'', asserts that everyone's happiness matters. It says that a person should maximize the sum total of happiness of everybody affected by their actions. This sum total includes the person's own happiness, but it is only one factor among many without any special preference compared to the happiness of others.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Weijers|loc=§ 1d. Normative Hedonism, § 1f. Hedonistic Utilitarianism}} | {{harvnb|Tilley|2012|loc=§ II. Ethical Hedonism}} }}</ref> As a result, utilitarian hedonism sometimes requires of people to forego their own enjoyment to benefit others. For example, philosopher ] argues that good earners should donate a significant portion of their income to charities since this money can produce more happiness for people in need.<ref>{{harvnb|Singer|2016|pp=163, 165}}</ref> | ||

| Ethical hedonism is often understood as a form of ], which asserts that an act is right if it has the best consequences. It is typically combined with axiological hedonism, which links the intrinsic value of consequences to pleasure and pain. As a result, the arguments for and against axiological hedonism also apply to ethical hedonism.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Frykhol|Rutherford|2013|p=}} | {{harvnb|Robertson|Walter|2013|p=}} | {{harvnb|Weijers|loc=§ 1d. Normative Hedonism, § 1e. Hedonistic Egoism, § 1f. Hedonistic Utilitarianism}} }}</ref> | Ethical hedonism is often understood as a form of ], which asserts that an act is right if it has the best consequences. It is typically combined with axiological hedonism, which links the intrinsic value of consequences to pleasure and pain. As a result, the arguments for and against axiological hedonism also apply to ethical hedonism.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Frykhol|Rutherford|2013|p=}} | {{harvnb|Robertson|Walter|2013|p=}} | {{harvnb|Weijers|loc=§ 1d. Normative Hedonism, § 1e. Hedonistic Egoism, § 1f. Hedonistic Utilitarianism}} }}</ref> | ||

| Line 46: | Line 51: | ||

| === Pleasure and pain === | === Pleasure and pain === | ||

| {{main|Pleasure|Pain}} | {{main|Pleasure|Pain}} | ||

| ]'' by ], 1894 |

]'' by ], 1894]] | ||

| Pleasure and pain are fundamental experiences about what is attractive and aversive, influencing how people feel, think, and act.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Pallies|2021|pp=887–888}} | {{harvnb|Katz|2016|loc=Lead section}} | {{harvnb|Johnson|2009|pp=704–705}} }}</ref> They play a central role in all forms of hedonism.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Weijers|loc=Lead section}} | {{harvnb|Feldman|2001|p=}} }}</ref> Both pleasure and pain come in degrees corresponding to their intensity. They are typically understood as a continuum ranging from positive degrees through a neutral point to negative degrees.<ref>{{harvnb|Alston|2006|loc=§ Demarcation of the Topic}}</ref> However, some hedonists reject the idea that pleasure and pain form a symmetric pair and suggest instead that avoiding pain is more important than producing pleasure.<ref>{{harvnb|Shriver|2014|pp=135–137}}</ref> | Pleasure and pain are fundamental experiences about what is attractive and aversive, influencing how people feel, think, and act.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Pallies|2021|pp=887–888}} | {{harvnb|Katz|2016|loc=Lead section}} | {{harvnb|Johnson|2009|pp=704–705}} }}</ref> They play a central role in all forms of hedonism.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Weijers|loc=Lead section}} | {{harvnb|Feldman|2001|p=}} }}</ref> Both pleasure and pain come in degrees corresponding to their intensity. They are typically understood as a continuum ranging from positive degrees through a neutral point to negative degrees.<ref>{{harvnb|Alston|2006|loc=§ Demarcation of the Topic}}</ref> However, some hedonists reject the idea that pleasure and pain form a symmetric pair and suggest instead that avoiding pain is more important than producing pleasure.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Shriver|2014|pp=135–137}} | {{harvnb|Luper|2009|p=}} }}</ref> | ||

| The nature of pleasure and pain is disputed and affects the plausibility of various versions of hedonism. In everyday language, these concepts are often understood in a narrow sense associated with specific phenomena, like the pleasure of food and sex or the pain of an injury.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Weijers|loc=§ 4b. Pleasure as Sensation, § 4d. Pleasure as Pro-Attitude}} | {{harvnb|Katz|2016|loc=Lead section}} | {{harvnb|Katz|2016a|loc=§ Note 1}} }}</ref> However, hedonists usually take a wider perspective in which pleasure and pain cover any positive or negative experiences. In this broad sense, anything that feels good is a pleasure, including the joy of watching a sunset, whereas anything that feels bad is a pain, including the sorrow of losing a loved one.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Pallies|2021|pp=887–888}} | {{harvnb|Feldman|2001| |

The nature of pleasure and pain is disputed and affects the plausibility of various versions of hedonism. In everyday language, these concepts are often understood in a narrow sense associated with specific phenomena, like the pleasure of food and sex or the pain of an injury.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Weijers|loc=§ 4b. Pleasure as Sensation, § 4d. Pleasure as Pro-Attitude}} | {{harvnb|Katz|2016|loc=Lead section}} | {{harvnb|Katz|2016a|loc=§ Note 1}} }}</ref> However, hedonists usually take a wider perspective in which pleasure and pain cover any positive or negative experiences. In this broad sense, anything that feels good is a pleasure, including the joy of watching a sunset, whereas anything that feels bad is a pain, including the sorrow of losing a loved one.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Pallies|2021|pp=887–888}} | {{harvnb|Feldman|2001|pp=}} | {{harvnb|Katz|2016|loc=Lead section}} | {{harvnb|Alston|2006|loc=§ Demarcation of the Topic}} }}</ref> A traditionally influential position says that pleasure and pain are specific bodily sensations, similar to the sensations of hot and cold. A more common view in contemporary philosophy holds that pleasure and pain are attitudes of attraction or aversion toward objects.{{efn|In this context the term "pro-attitude" is also used.<ref>{{harvnb|Weijers|loc=§ 4b. Pleasure as Sensation}}</ref>}} This view implies that they do not have a specific location in the body and do not arise in isolation since they are always directed at an object that people enjoy or suffer.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Feldman|2001|pp=}} | {{harvnb|Pallies|2021|pp=887–888}} | {{harvnb|Weijers|loc=§ 4b. Pleasure as Sensation, § 4d. Pleasure as Pro-Attitude}} }}</ref> | ||

| ==== Measurement ==== | ==== Measurement ==== | ||

| Both philosophers and psychologists are interested in methods of measuring pleasure and pain to guide ] and gain a deeper understanding of their causes. A common approach is to use self-report ]s in which people are asked to quantify how pleasant or unpleasant an experience is. For example, some questionnaires use a nine-point scale from -4 for the most unpleasant experiences, to +4 for the most pleasant ones. Some methods rely on memory and ask individuals to retrospectively assess their experiences. A different approach is for individuals to evaluate their experiences while they are happening to avoid ] and inaccuracies introduced by memory.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Alston|2006|loc=§ The Measurement of Pleasure}} | {{harvnb|Johnson|2009|pp=706–707}} | {{harvnb|Bartoshuk|2014|pp=91–93}} | {{harvnb|Lazari-Radek|2024|pp=51–58}} }}</ref> | Both philosophers and psychologists are interested in methods of measuring pleasure and pain to guide ] and gain a deeper understanding of their causes. A common approach is to use self-report ]s in which people are asked to quantify how pleasant or unpleasant an experience is. For example, some questionnaires use a nine-point scale from -4 for the most unpleasant experiences, to +4 for the most pleasant ones. Some methods rely on memory and ask individuals to retrospectively assess their experiences. A different approach is for individuals to evaluate their experiences while they are happening to avoid ] and inaccuracies introduced by memory.<ref name="auto">{{multiref | {{harvnb|Alston|2006|loc=§ The Measurement of Pleasure}} | {{harvnb|Johnson|2009|pp=706–707}} | {{harvnb|Bartoshuk|2014|pp=91–93}} | {{harvnb|Lazari-Radek|2024|pp=51–58}} }}</ref> | ||

| In either form, the measurement of pleasure and pain poses various challenges. As a highly ] phenomenon, it is difficult to establish a standardized metric. Moreover, asking people to rate their experiences using an artificially constructed scale may not accurately reflect their subjective experiences. A closely related problem concerns comparisons between individuals since different people may use the scales differently and thus arrive at different values even if they had similar experiences.<ref |

In either form, the measurement of pleasure and pain poses various challenges. As a highly ] phenomenon, it is difficult to establish a standardized metric. Moreover, asking people to rate their experiences using an artificially constructed scale may not accurately reflect their subjective experiences. A closely related problem concerns comparisons between individuals since different people may use the scales differently and thus arrive at different values even if they had similar experiences.<ref name="auto"/> ] avoid some of these challenges by using ] techniques such as ] and ]. However, this approach comes with new difficulties of its own since the neurological basis of happiness is not yet fully understood.<ref>{{harvnb|Suardi|Sotgiu|Costa|Cauda|2016|pp=383–385}}</ref> | ||

| Based on the idea that individual experiences of pleasure and pain can be quantified, ] proposed the ] as a method to combine various episodes to arrive at their total contribution to happiness. This makes it possible to quantitatively compare different courses of action based on the experiences they produce to choose the course with the highest overall contribution to happiness. Bentham considered several factors for each pleasurable experience: its intensity and duration, the likelihood that it occurs, its temporal distance, the likelihood that it causes further experiences of pleasure and pain, and the number of people affected. Some simplified versions of the hedonic calculus focus primarily on what is intrinsically valuable to a person and only consider two factors: intensity and duration.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Feldman|2001|p=}} | {{harvnb|Bowie|Simon|1998|p=}} | {{harvnb|Weijers|loc=§ 3a. Bentham}} | {{harvnb|Heathwood|2013|loc=§ What Determines the Intrinsic Value of a Pleasure or a Pain?}} | {{harvnb|Woodward|2017|loc=Lead section, § Dimensions of the Hedonistic Calculus}} }}</ref> | Based on the idea that individual experiences of pleasure and pain can be quantified, ] proposed the ] as a method to combine various episodes to arrive at their total contribution to happiness. This makes it possible to quantitatively compare different courses of action based on the experiences they produce to choose the course with the highest overall contribution to happiness. Bentham considered several factors for each pleasurable experience: its intensity and duration, the likelihood that it occurs, its temporal distance, the likelihood that it causes further experiences of pleasure and pain, and the number of people affected. Some simplified versions of the hedonic calculus focus primarily on what is intrinsically valuable to a person and only consider two factors: intensity and duration.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Feldman|2001|p=}} | {{harvnb|Bowie|Simon|1998|p=}} | {{harvnb|Weijers|loc=§ 3a. Bentham}} | {{harvnb|Heathwood|2013|loc=§ What Determines the Intrinsic Value of a Pleasure or a Pain?}} | {{harvnb|Woodward|2017|loc=Lead section, § Dimensions of the Hedonistic Calculus}} }}</ref> | ||

| Line 64: | Line 69: | ||

| Well-being is what is ultimately good for a person.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Crisp|2021|loc=Lead section}} | {{harvnb|Tiberius|2015|p=}} }}</ref> According to a common view, pleasure is one component of well-being. It is controversial whether it is the only factor and what other factors there are, such as health, knowledge, and friendship. Another approach focuses on desires, saying that well-being consists in the satisfaction of desires.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Crisp|2021|loc=§ 1. The Concept, § 4. Theories of Well-being}} | {{harvnb|Tiberius|2015|pp=}} }}</ref> The view that the balance of pleasure over pain is the only source of well-being is called ''prudential hedonism''.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Crisp|2021|loc=§ 4.1 Hedonism}} | {{harvnb|Hughes|2014|p=}} }}</ref> | Well-being is what is ultimately good for a person.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Crisp|2021|loc=Lead section}} | {{harvnb|Tiberius|2015|p=}} }}</ref> According to a common view, pleasure is one component of well-being. It is controversial whether it is the only factor and what other factors there are, such as health, knowledge, and friendship. Another approach focuses on desires, saying that well-being consists in the satisfaction of desires.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Crisp|2021|loc=§ 1. The Concept, § 4. Theories of Well-being}} | {{harvnb|Tiberius|2015|pp=}} }}</ref> The view that the balance of pleasure over pain is the only source of well-being is called ''prudential hedonism''.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Crisp|2021|loc=§ 4.1 Hedonism}} | {{harvnb|Hughes|2014|p=}} }}</ref> | ||

| Eudaimonia is a form of well-being rooted in ], serving as a foundation of many forms of |

Eudaimonia is a form of well-being rooted in ], serving as a foundation of many forms of moral philosophy during this period. ] understood eudaimonia as a type of flourishing in which a person is happy by leading a fulfilling life and manifesting their inborn capacities. Ethical theories based on eudaimonia often share parallels with hedonism, like an interest in long-term happiness, but are distinguished from it by their emphasis of ], advocating an active lifestyle focused on ].<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Lelkes|2021|pp=}} | {{harvnb|Feldman|2004|pp=15–16}} | {{harvnb|Taylor|2005|pp=364–365}} }}</ref> | ||

| === Paradox of hedonism and hedonic treadmill === | === Paradox of hedonism and hedonic treadmill === | ||

| Line 78: | Line 83: | ||

| ==History== | ==History== | ||

| ===Etymology=== | |||

| The term ''hedonism'' derives from the ] ''hēdonismos'' ({{Langx|grc|ἡδονισμός|lit=delight|label=none}}; from {{Langx|grc|ἡδονή|lit=pleasure|label=none|translit=]}}), which is a ] from ] ''swéh₂dus'' through ] | |||

| ''hēdús'' ({{Langx|grc|ἡδύς|lit=pleasant to the taste or smell, sweet|label=none}}) or ''hêdos'' ({{Langx|grc|ἧδος|lit=delight, pleasure|label=none}}) | |||

| + suffix ''-ismos'' (-ισμός, ']'). | |||

| === Ancient === | === Ancient === | ||

| ] is often seen as the first proponent of philosophical hedonism.]] | ] is often seen as the first proponent of philosophical hedonism.]] | ||

| Hedonism is one of the oldest philosophical theories and some interpreters trace it back to the ], written around 2100–2000 BCE.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Porter|2001|p=}} | {{harvnb|Gosling|1998|loc=Lead section}} | {{harvnb|Forgas|Baumeister|2018|loc=}} | {{harvnb|Ackermann|Schroeder|Terry|Upshur|2008|p=161}} }}</ref> A central topic in ], ] (435-356 BCE) is usually identified as its earliest philosophical proponent. As a student of ] ({{circa|469–399 BCE}}),<ref>{{harvnb|Dehsen|2013|p=178}}</ref> he formulated a hedonistic egoism, arguing that personal pleasure is the highest good. He and the school of ] he inspired focused on the gratification of immediate sensory pleasures with little concern for long-term consequences.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Weijers|loc=§ 2b. |

Hedonism is one of the oldest philosophical theories and some interpreters trace it back to the ], written around 2100–2000 BCE.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Porter|2001|p=}} | {{harvnb|Gosling|1998|loc=Lead section}} | {{harvnb|Forgas|Baumeister|2018|loc=}} | {{harvnb|Ackermann|Schroeder|Terry|Upshur|2008|p=161}} }}</ref> A central topic in ], ] (435-356 BCE) is usually identified as its earliest philosophical proponent. As a student of ] ({{circa|469–399 BCE}}),<ref>{{harvnb|Dehsen|2013|p=178}}</ref> he formulated a hedonistic egoism, arguing that personal pleasure is the highest good. He and the school of ] he inspired focused on the gratification of immediate sensory pleasures with little concern for long-term consequences.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Weijers|loc=§ 2b. Aristippus and the Cyrenaics}} | {{harvnb|Brandt|2006|p=255}} | {{harvnb|Taylor|2005|p=364}} | {{harvnb|Feldman|2001|pp=}} }}</ref> ] ({{circa|428–347 BCE}})<ref>{{harvnb|Dehsen|2013|p=156}}</ref> critiqued this view and proposed a more balanced pursuit of pleasure that aligns with virtue and rationality.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Taylor|2005|p=364}} | {{harvnb|Gosling|1998|loc=§ 1. History and Varieties of Hedonism}} }}</ref> Following a similar approach, ] (384–322 BCE)<ref>{{harvnb|Dehsen|2013|p=13}}</ref> associated pleasure with ] or the realization of natural human capacities, like reason.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Taylor|2005|p=365}} | {{harvnb|Gosling|1998|loc=§ 1. History and Varieties of Hedonism}} }}</ref> | ||

| ] (341–271 BCE) developed a nuanced form of hedonism that contrasts with the indulgence in immediate gratification proposed by the Cyrenaics. He argued that excessive desires and anxiety result in suffering, suggesting instead that people practice moderation, cultivate a ], and avoid pain.<ref |

] (341–271 BCE) developed a nuanced form of hedonism that contrasts with the indulgence in immediate gratification proposed by the Cyrenaics. He argued that excessive desires and anxiety result in suffering, suggesting instead that people practice moderation, cultivate a ], and avoid pain.<ref name="auto2"/> Following ] ({{circa|446—366 BCE}}), the ] warned against the pursuit of pleasure, viewing it as an obstacle to freedom.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Gosling|1998|loc=§ 1. History and Varieties of Hedonism}} | {{harvnb|Piering|loc=§ 2. Basic Tenets}} }}</ref> The ] also dismissed a hedonistic lifestyle, focusing on virtue and integrity instead of seeking pleasure and avoiding pain.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Gosling|1998|loc=§ 1. History and Varieties of Hedonism}} | {{harvnb|Pigliucci|loc=§ 1d. Debates with Other Hellenistic Schools}} }}</ref> ] ({{circa|99–55 BCE}}) further expanded on Epicureanism, highlighting the importance of overcoming obstacles to personal happiness, such as the fear of death.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Simpson|loc=§ 2b.iii. Ethics}} | {{harvnb|Ewin|2002|p=}} | {{harvnb|Asmis|2018|pp=}} }}</ref> | ||

| In ], the ] school developed a hedonistic egoism, starting between the 6th and 5th centuries BCE. Their belief in the ] or an ] led them to advocate for enjoying life in the present to the fullest. Many other Indian traditions rejected this view and recommended |

In ], the ] school developed a hedonistic egoism, starting between the 6th and 5th centuries BCE. Their belief in the ] or an ] led them to advocate for enjoying life in the present to the fullest. Many other Indian traditions rejected this view and recommended a more ascetic lifestyle, a tendency common among ], ], and ] schools of thought.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Weijers|loc=§ 2a. Cārvāka}} | {{harvnb|Riepe|1956|pp=551–552}} | {{harvnb|Turner-Lauck Wernicki|loc=§ 2b. Materialism as Heresy}} | {{harvnb|Wilson|2015|loc=§ Introduction}} }}</ref> In ancient China, ] ({{circa|440–360 BCE}}){{efn|Some interpreters question whether Yang Zhu is a historical or a mythical figure.<ref>{{harvnb|Norden|Ivanhoe|2023|p=}}</ref>}} argued that it is human nature to follow self-interest and satisfy personal desires. His hedonistic egoism inspired the subsequent school of ].<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Roetz|1993|pp=}} | {{harvnb|Norden|Ivanhoe|2023|p=}} }}</ref> | ||

| === Medieval === | === Medieval === | ||

| ⚫ | Hedonist philosophy received less attention in ].<ref>{{harvnb|Gosling|1998|loc=§ 1. History and Varieties of Hedonism}}</ref> The early Christian philosopher ] (354–430 CE),<ref>{{harvnb|Dehsen|2013|p=16}}</ref> was critical of the hedonism found in ancient Greek philosophy, warning of the dangers of earthly pleasures as obstacles to a spiritual life dedicated to God.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Rist|1994|p=}} | {{harvnb|Alexander|Shelton|2014|p=}} }}</ref> ] (1225–1274 CE) developed a nuanced perspective on hedonism, characterized by some interpreters as spiritual hedonism. He held that humans are naturally inclined to seek happiness, arguing that the only way to truly satisfy this inclination is through a ] of God.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Dewan|2008|pp=}} | {{harvnb|Wieland|2002|p=}} | {{harvnb|Zagzebski|2004|p=}} }}</ref> In ], the problem of pleasure played a central role in the philosophy of ] ({{circa|864—925 or 932 CE}}). Similar to Epicureanism, he recommended a life of moderation avoiding the extremes of excess and ].<ref name="auto5">{{multiref | {{harvnb|Goodman|2020|pp=387–389}} | {{harvnb|Adamson|2021|loc=§ 3. Ethics}} | {{harvnb|Adamson|2021a|pp=5–6, 177–178}} }}</ref>{{efn|It is controversial whether al-Razi's position is a form of hedonism.<ref name="auto5"/>}} Both ] ({{circa|878–950 CE}})<ref>{{harvnb|Dehsen|2013|p=63}}</ref> and ] (980–1037 CE)<ref>{{harvnb|Dehsen|2013|p=19}}</ref> asserted that a form of intellectual happiness, reachable only in the afterlife, is the highest human good.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Germann|2021|loc=§ 2.1 Happiness and the afterlife}} | {{harvnb|McGinnis|2010|pp=}} }}</ref> | ||

| ] developed a moderate hedonism.]] | |||

| ⚫ | Hedonist philosophy received less attention in ].<ref>{{harvnb|Gosling|1998|loc=§ 1. History and Varieties of Hedonism}}</ref> The early Christian philosopher ] (354–430 CE),<ref>{{harvnb|Dehsen|2013|p=16}}</ref> was critical of the hedonism found in ancient Greek philosophy, warning of the dangers of earthly pleasures as obstacles to a spiritual life dedicated to God.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Rist|1994|p=}} | {{harvnb|Alexander|Shelton|2014|p=}} }}</ref> ] (1225–1274 CE) developed a nuanced perspective on hedonism, characterized by some interpreters as spiritual hedonism. He held that humans are naturally inclined to seek happiness, arguing that the only way to truly satisfy this inclination is through a ] of God.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Dewan|2008|pp=}} | {{harvnb|Wieland|2002|p=}} | {{harvnb|Zagzebski|2004|p=}} }}</ref> In ], ] ({{circa|864—925 or 932 CE}}) |

||

| === Modern and contemporary === | === Modern and contemporary === | ||

| At the transition to the early modern period, ] ({{circa|1406–1457}}) synthesized Epicurean hedonism with ], suggesting that earthly pleasures associated with the senses are stepping stones to heavenly pleasures associated with Christian virtues.<ref>{{harvnb|Nauta|2021|loc=§ 4. Moral Philosophy}}</ref> Hedonism gained prominence during the ].<ref>{{harvnb|Blakemore|Jennett|2001|loc=§ Pleasure and the Enlightenment}}</ref> According to ]'s (1588–1679)<ref>{{harvnb|Dehsen|2013|p=88}}</ref> psychological hedonism, self-interest in what is pleasant is the root of all human motivation.<ref |

At the transition to the early modern period, ] ({{circa|1406–1457}}) synthesized Epicurean hedonism with ], suggesting that earthly pleasures associated with the senses are stepping stones to heavenly pleasures associated with Christian virtues.<ref>{{harvnb|Nauta|2021|loc=§ 4. Moral Philosophy}}</ref> Hedonism gained prominence during the ].<ref>{{harvnb|Blakemore|Jennett|2001|loc=§ Pleasure and the Enlightenment}}</ref> According to ]'s (1588–1679)<ref>{{harvnb|Dehsen|2013|p=88}}</ref> psychological hedonism, self-interest in what is pleasant is the root of all human motivation.<ref name="auto3"/> ] (1632–1704) stated that pleasure and pain are the only sources of good and evil.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Sheridan|2024|loc=§ 1.1 The puzzle of Locke’s moral philosophy}} | {{harvnb|Rossiter|2016|pp=203, 207–208}} }}</ref> ] (1692–1752) formulated an objection to psychological hedonism, arguing that most desires, like wanting food or ambition, are not directed at pleasure itself but at external objects.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Stewart|1992|pp=211–214}} | {{harvnb|Garrett|2023|loc=§ 5. Self-Love and Benevolence}} }}</ref> According to ] (1711–1776),<ref>{{harvnb|Dehsen|2013|p=91}}</ref> pleasure and pain are both the measure of ethical value and the main motivators fueling the passions.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Blakemore|Jennett|2001|loc=§ Pleasure and the Enlightenment}} | {{harvnb|Dorsey|2015|pp=245–246}} | {{harvnb|Merivale|2018|loc=}} }}</ref> The ] novels of ] (1740–1814) depicted an extreme form of hedonism, emphasizing full indulgence in pleasurable activities without moral or ].<ref>{{harvnb|Airaksinen|1995|pp=11, 78–80}}</ref> | ||

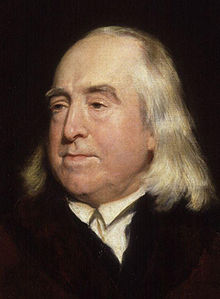

| ] formulated a universal form of hedonism that takes everyone's pleasure into account.]] | ] formulated a universal form of hedonism that takes everyone's pleasure into account.]] | ||

| Line 105: | Line 102: | ||

| ] (1748–1832)<ref>{{harvnb|Dehsen|2013|p=25}}</ref> developed an influential form of hedonism known as ]. One of his key innovations was the rejection of egoistic hedonism, advocating instead that individuals should promote the greatest good for the greatest number of people. He introduced the idea of the ] to assess the value of an action based on the pleasurable and painful experiences it causes, relying on factors such as intensity and duration.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Weijers|loc=§ 3a. Bentham}} | {{harvnb|Moore|2019|loc=§ 2.1 Ethical Hedonism and the Nature of Pleasure}} | {{harvnb|Feldman|2001|p=666}} }}</ref> His student ] (1806–1873)<ref>{{harvnb|Dehsen|2013|p=132}}</ref> feared that Bentham's quantitative focus on intensity and duration would lead to an overemphasis on simple sensory pleasures. In response, he included the quality of pleasures as an additional factor, arguing that higher pleasures of the mind are more valuable than lower pleasures of the body.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Weijers|loc=§ 3b. Mill}} | {{harvnb|Moore|2019|loc=§ 2.1 Ethical Hedonism and the Nature of Pleasure}} | {{harvnb|Gosling|1998|loc=§ 1. History and Varieties of Hedonism}} }}</ref> ] (1838–1900) further refined utilitarianism and clarified many of its core distinctions, such as the contrast between ethical and psychological hedonism and between egoistic and impartial hedonism.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Crisp|2011|pp=26–27}} | {{harvnb|Schultz|2024|loc=Lead section, § 2.2 Reconstruction and Reconciliation}} | {{harvnb|Gosling|1998|loc=§ 1. History and Varieties of Hedonism}} }}</ref> | ] (1748–1832)<ref>{{harvnb|Dehsen|2013|p=25}}</ref> developed an influential form of hedonism known as ]. One of his key innovations was the rejection of egoistic hedonism, advocating instead that individuals should promote the greatest good for the greatest number of people. He introduced the idea of the ] to assess the value of an action based on the pleasurable and painful experiences it causes, relying on factors such as intensity and duration.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Weijers|loc=§ 3a. Bentham}} | {{harvnb|Moore|2019|loc=§ 2.1 Ethical Hedonism and the Nature of Pleasure}} | {{harvnb|Feldman|2001|p=666}} }}</ref> His student ] (1806–1873)<ref>{{harvnb|Dehsen|2013|p=132}}</ref> feared that Bentham's quantitative focus on intensity and duration would lead to an overemphasis on simple sensory pleasures. In response, he included the quality of pleasures as an additional factor, arguing that higher pleasures of the mind are more valuable than lower pleasures of the body.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Weijers|loc=§ 3b. Mill}} | {{harvnb|Moore|2019|loc=§ 2.1 Ethical Hedonism and the Nature of Pleasure}} | {{harvnb|Gosling|1998|loc=§ 1. History and Varieties of Hedonism}} }}</ref> ] (1838–1900) further refined utilitarianism and clarified many of its core distinctions, such as the contrast between ethical and psychological hedonism and between egoistic and impartial hedonism.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Crisp|2011|pp=26–27}} | {{harvnb|Schultz|2024|loc=Lead section, § 2.2 Reconstruction and Reconciliation}} | {{harvnb|Gosling|1998|loc=§ 1. History and Varieties of Hedonism}} }}</ref> | ||

| ] (1844–1900)<ref>{{harvnb|Dehsen|2013|p=144}}</ref> rejected ethical hedonism and emphasized the importance of excellence and self-overcoming instead, stating that suffering is necessary to achieve greatness rather than something to be avoided.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Hassan|2023|p=}} | {{harvnb|Faustino|2024|loc=§ 2.1 Ethical Hedonism}} }}</ref> An influential view about the nature of pleasure was developed by ] (1838–1917).<ref>{{harvnb|Kriegel|2018|p=}}</ref> He dismissed the idea that pleasure is a sensation located in a specific area of the body, proposing instead that pleasure is a positive attitude that people can have towards various objects{{efn|According to this view, for instance, the pleasure of reading a novel is a positive attitude towards the novel.<ref>{{harvnb|Massin|2013|pp=}}</ref>}}{{em dash}}a position also later defended by ] (1916–1999).<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Feldman|2001|p=668}} | {{harvnb|Massin|2013|pp=}} | {{harvnb|Moore|2019|loc=§ 2.1 Ethical Hedonism and the Nature of Pleasure}} }}</ref> ] (1856–1939) developed a form of psychological hedonism in his early ]. He stated that the ] describes how individuals seek immediate pleasure while avoiding pain whereas the ] represents the ability to postpone immediate gratification to avoid unpleasant long-term consequences.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Wallwork|1991|p=}} | {{harvnb|Vittersø|2012|p=}} }}</ref> |

] (1844–1900)<ref>{{harvnb|Dehsen|2013|p=144}}</ref> rejected ethical hedonism and emphasized the importance of excellence and self-overcoming instead, stating that suffering is necessary to achieve greatness rather than something to be avoided.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Hassan|2023|p=}} | {{harvnb|Faustino|2024|loc=§ 2.1 Ethical Hedonism}} }}</ref> An influential view about the nature of pleasure was developed by ] (1838–1917).<ref>{{harvnb|Kriegel|2018|p=}}</ref> He dismissed the idea that pleasure is a sensation located in a specific area of the body, proposing instead that pleasure is a positive attitude that people can have towards various objects{{efn|According to this view, for instance, the pleasure of reading a novel is a positive attitude towards the novel.<ref>{{harvnb|Massin|2013|pp=}}</ref>}}{{em dash}}a position also later defended by ] (1916–1999).<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Feldman|2001|p=668}} | {{harvnb|Massin|2013|pp=}} | {{harvnb|Moore|2019|loc=§ 2.1 Ethical Hedonism and the Nature of Pleasure}} }}</ref> ] (1856–1939) developed a form of psychological hedonism in his early ]. He stated that the ] describes how individuals seek immediate pleasure while avoiding pain whereas the ] represents the ability to postpone immediate gratification to avoid unpleasant long-term consequences.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Wallwork|1991|p=}} | {{harvnb|Vittersø|2012|p=}} }}</ref> | ||

| The 20th century saw various criticisms of hedonism.<ref>{{harvnb|Crisp|2011|pp=43–44}}</ref> ] (1873–1958)<ref>{{harvnb|Bunnin|Yu|2009|p=443}}</ref> rejected the hedonistic idea that pleasure is the only source of intrinsic value. According to his ], there are other sources, such as ] and ],<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Hurka|2021|loc=§ 4. The Ideal}} | {{harvnb|Gosling|1998|loc=§ 1. History and Varieties of Hedonism}} | {{harvnb|Moore|2019|loc=§ 2.3 Other Arguments Against Ethical Hedonism}} | {{harvnb|Crisp|2011|p=43}} }}</ref> a criticism also shared by ] (1877–1971).<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Skelton|2022|loc=§ 4.2 The Good}} | {{harvnb|Mason|2023|loc=§ 1.1 Foundational and Non-foundational Pluralism}} | {{harvnb|Crisp|2011|p=43}} }}</ref> Both ] (1887–1971) and ] (1910–1997) held that malicious pleasures, like enjoying the suffering of others, do not have inherent value.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Crisp|2011|pp=43–44}} | {{harvnb|Hurka|2011a|p=73}} | {{harvnb|Feldman|2002|p=616}} | {{harvnb|Feldman|2004|p=38}} }}</ref> ] (1938–2002) used his ] thought experiment about simulated pleasure to argue against traditional hedonism, which ignores whether there is an authentic connection between pleasure and reality.<ref |

The 20th century saw various criticisms of hedonism.<ref>{{harvnb|Crisp|2011|pp=43–44}}</ref> ] (1873–1958)<ref>{{harvnb|Bunnin|Yu|2009|p=443}}</ref> rejected the hedonistic idea that pleasure is the only source of intrinsic value. According to his ], there are other sources, such as ] and ],<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Hurka|2021|loc=§ 4. The Ideal}} | {{harvnb|Gosling|1998|loc=§ 1. History and Varieties of Hedonism}} | {{harvnb|Moore|2019|loc=§ 2.3 Other Arguments Against Ethical Hedonism}} | {{harvnb|Crisp|2011|p=43}} }}</ref> a criticism also shared by ] (1877–1971).<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Skelton|2022|loc=§ 4.2 The Good}} | {{harvnb|Mason|2023|loc=§ 1.1 Foundational and Non-foundational Pluralism}} | {{harvnb|Crisp|2011|p=43}} }}</ref> Both ] (1887–1971) and ] (1910–1997) held that malicious pleasures, like enjoying the suffering of others, do not have inherent value.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Crisp|2011|pp=43–44}} | {{harvnb|Hurka|2011a|p=73}} | {{harvnb|Feldman|2002|p=616}} | {{harvnb|Feldman|2004|p=38}} }}</ref> ] (1938–2002) used his ] thought experiment about simulated pleasure to argue against traditional hedonism, which ignores whether there is an authentic connection between pleasure and reality.<ref name="auto4"/> | ||

| In response to these and similar criticisms, ] (1941–present) has developed a modified form of hedonism. Drawing on Brentano's attitudinal theory of pleasure, he has defended the idea that even though pleasure is the only source of intrinsic goodness, its value must be adjusted based on whether it is appropriate or deserved.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Feldman|2004|pp=120–123}} | {{harvnb|McLeod|2017|loc=}} }}</ref> ] (1946–present) has expanded classical hedonism to include concerns about ].{{efn|Singer was initially a proponent of ] but has shifted his position in favor of hedonistic utilitarianism.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Rice|2015|p=}} | {{harvnb|Schultz|2017|p=}} }}</ref>}} He has advocated ], relying on ] and reason to prioritize actions that have the most significant positive impact.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Schultz|2017|p=}} | {{harvnb|Fesmire|2020|loc=}} }}</ref> Inspired by the philosophy of ] (1913–1960), ] (1959–present) has aimed to rehabilitate Epicurean hedonism in a modern form.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|McClellan|2015|pp=xviii–xx}} | {{harvnb|Bishop|2020|pp=}} }}</ref> ] (1959–present) has developed a ] version of hedonism, arguing for the use of modern technology, ranging from ] to ], to reduce suffering and possibly eliminate it in the future.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Adams IV|2004|p=}} | {{harvnb|Ross|2020|p=}} }}</ref> The emergence of ] at the turn of the 21st century has led to an increased interest in the empirical exploration of various topics of hedonism.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Crisp|2011|p=44}} | {{harvnb|Peterson|2006|pp=}} }}</ref> | In response to these and similar criticisms, ] (1941–present) has developed a modified form of hedonism. Drawing on Brentano's attitudinal theory of pleasure, he has defended the idea that even though pleasure is the only source of intrinsic goodness, its value must be adjusted based on whether it is appropriate or deserved.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Feldman|2004|pp=120–123}} | {{harvnb|McLeod|2017|loc=}} }}</ref> ] (1946–present) has expanded classical hedonism to include concerns about ].{{efn|Singer was initially a proponent of ] but has shifted his position in favor of hedonistic utilitarianism.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Rice|2015|p=}} | {{harvnb|Schultz|2017|p=}} }}</ref>}} He has advocated ], relying on ] and reason to prioritize actions that have the most significant positive impact.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Schultz|2017|p=}} | {{harvnb|Fesmire|2020|loc=}} | {{harvnb|Miligan|2015|p=}} }}</ref> Inspired by the philosophy of ] (1913–1960), ] (1959–present) has aimed to rehabilitate Epicurean hedonism in a modern form.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|McClellan|2015|pp=xviii–xx}} | {{harvnb|Bishop|2020|pp=}} }}</ref> ] (1959–present) has developed a ] version of hedonism, arguing for the use of modern technology, ranging from ] to ], to reduce suffering and possibly eliminate it in the future.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Adams IV|2004|p=}} | {{harvnb|Ross|2020|p=}} }}</ref> The emergence of ] at the turn of the 21st century has led to an increased interest in the empirical exploration of various topics of hedonism.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Crisp|2011|p=44}} | {{harvnb|Peterson|2006|pp=}} }}</ref> | ||

| == In various fields == | == In various fields == | ||

| ] studies how to cultivate happiness and promote optimal human functioning. Unlike traditional ], which often focuses on ], positive psychology emphasizes that optimal functioning goes beyond merely the absence of ]. On the individual level, it investigates experiences of pleasure and pain and the role of ]s. On the societal level, it examines how ]s impact human well-being.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Vittersø|2012|pp=}} | {{harvnb|Kaczmarek|2023|pp=}} | {{harvnb|Colman|2015|loc=}} | {{harvnb|Seligman|Csikszentmihalyi|2000|pp=5–6 |

] studies how to cultivate happiness and promote optimal human functioning. Unlike traditional ], which often focuses on ], positive psychology emphasizes that optimal functioning goes beyond merely the absence of ]. On the individual level, it investigates experiences of pleasure and pain and the role of ]s. On the societal level, it examines how ]s impact human well-being.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Vittersø|2012|pp=}} | {{harvnb|Kaczmarek|2023|pp=}} | {{harvnb|Colman|2015|loc=}} | {{harvnb|Seligman|Csikszentmihalyi|2000|pp=5–6}} }}</ref> | ||

| Hedonic psychology or hedonics{{efn|In a different sense, the term ''hedonics'' is also used in ethics for the study of the relation between pleasure and duty.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Merriam-Webster|2024}} | {{harvnb|HarperCollins|2024}} }}</ref>}} is one of the main pillars of positive psychology by studying |

Hedonic psychology or hedonics{{efn|In a different sense, the term ''hedonics'' is also used in ethics for the study of the relation between pleasure and duty.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Merriam-Webster|2024}} | {{harvnb|HarperCollins|2024}} }}</ref>}} is one of the main pillars of positive psychology by studying pleasurable and unpleasurable experiences. It investigates and compares different states of consciousness associated with pleasure and pain, ranging from joy and satisfaction to boredom and sorrow. It also examines the role or ] of these states, such as signaling to individuals what to approach and avoid, and their purpose as reward and punishment to ] or discourage future behavioral patterns. Additionally, hedonic psychology explores the circumstances that evoke these experiences, on both the biological and social levels.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Kahneman|Diener|Schwarz|1999|p=}} | {{harvnb|Vittersø|2012|pp=}} | {{harvnb|Kaczmarek|2023|pp=}} }}</ref> It includes questions about psychological obstacles to pleasure, such as ], which is a reduced ability to experience pleasure, and ], which is a fear or aversion to pleasure.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|American Psychological Association|2018}} | {{harvnb|Doctor|Kahn|2010|p=}} | {{harvnb|Campbell|2009|p=}} }}</ref> Positive psychology in general and hedonic psychology in particular are relevant to hedonism by providing a scientific understanding of the experiences of pleasure and pain and the processes impacting them.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Vittersø|2012|pp=}} | {{harvnb|Kahneman|Diener|Schwarz|1999|p=}} }}</ref> | ||

| In the field of ], ] examines how economic activities affect ]. It is often understood as a form of ] that uses considerations of welfare to evaluate economic processes and policies. Hedonist approaches to welfare economics state that pleasure is the main criterion of this evaluation, meaning that economic activities should aim to promote societal happiness.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Hausman|2010|pp=321–322, 324–325, 327}} | {{harvnb|Mishan|2008|loc=§ Lead section}} }}</ref> The ] is a closely related field studying the relation between economic phenomena, such as wealth, and individual happiness.<ref>{{harvnb|Graham|2012|pp=}}</ref> Economists also employ ], a method used to estimate the value of ] based on their ] or effect on the owner's pleasure.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Goodstein|Polasky|2017|p=}} | {{harvnb|Hackett|Dissanayake|2014|p=}} }}</ref> | In the field of ], ] examines how economic activities affect ]. It is often understood as a form of ] that uses considerations of welfare to evaluate economic processes and policies. Hedonist approaches to welfare economics state that pleasure is the main criterion of this evaluation, meaning that economic activities should aim to promote societal happiness.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Hausman|2010|pp=321–322, 324–325, 327}} | {{harvnb|Mishan|2008|loc=§ Lead section}} }}</ref> The ] is a closely related field studying the relation between economic phenomena, such as wealth, and individual happiness.<ref>{{harvnb|Graham|2012|pp=}}</ref> Economists also employ ], a method used to estimate the value of ] based on their ] or effect on the owner's pleasure.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Goodstein|Polasky|2017|p=}} | {{harvnb|Hackett|Dissanayake|2014|p=}} }}</ref> | ||

| ] has applied ] to problems of ].<ref>{{harvnb|Miligan|2015|p=}}</ref>]] | |||

| ⚫ | ] is the branch of ] studying human behavior towards other animals. Hedonism is an influential position in this field as a theory about ]. It emphasizes that humans have the responsibility to consider the impact of their actions on how animals feel to minimize harm done to them.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Wilson|loc=Lead section}} | {{harvnb|Gordon, "''Bioethics''"|ref=Gordon, "''Bioethics''"|loc=Lead section, § 3c. Animal Ethics}} | {{harvnb|Robbins|Franks|von Keyserlingk|2018|loc=§ Abstract, § Introduction}} }}</ref> Some quantitative hedonists suggest that there is no significant difference between the pleasure and pain experienced by humans and other animals. As a result of this view, ] considerations about promoting the happiness of other people apply equally to all ] animals. This position is modified by some qualitative hedonists, who argue that human experiences carry more weight because they include higher forms of pleasure and pain.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Lazari-Radek|2024|pp=24–25}} | {{harvnb|Lazari-Radek|Singer|2014|pp=}} | {{harvnb|Weijers|2019|p=}} | {{harvnb|Tilley|2012|loc=§ III. Axiological Hedonism}} }}</ref> | ||

| ⚫ | ] is the branch of ] studying human behavior towards other animals. Hedonism is an influential position in this field as a theory about ]. It emphasizes that humans have the responsibility to consider the impact of their actions on how animals feel to minimize harm done to them.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Wilson|loc=Lead section}} | {{harvnb|Gordon, "''Bioethics''"|ref=Gordon, "''Bioethics''"|loc=Lead section, § 3c. Animal Ethics}} | {{harvnb|Robbins|Franks|von Keyserlingk|2018|loc=§ Abstract, § Introduction}} }}</ref> Some quantitative hedonists suggest that there is no significant difference between the pleasure and pain experienced by humans and other animals. As a result of this view, ] considerations about promoting the happiness of other people apply equally to all ] animals. This position is modified by some qualitative hedonists, who argue that human experiences carry more weight because they include higher forms of pleasure and pain.<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Lazari-Radek|2024|pp=24–25}} | {{harvnb|Lazari-Radek|Singer|2014|pp=}} | {{harvnb|Weijers|2019|p=}} | {{harvnb|Tilley|2012|loc=§ III. Axiological Hedonism}} }}</ref> | ||

| ⚫ | While many religious traditions are critical of hedonism, some have embraced it or certain aspects of it, such as ].<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Piper|2011|p=}} | {{harvnb|Chryssides|2013|pp=}} }}</ref> Elements of hedonism are also found in various forms of ], such as ], the ], and the enduring influences of the ].<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Danesi|2016|p=}} | {{harvnb|Blue|2013|loc=}} | {{harvnb|Boden|2003|p=}} | {{harvnb|Smith|1990| |

||

| ⚫ | While many religious traditions are critical of hedonism, some have embraced it or certain aspects of it, such as ].<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Piper|2011|p=}} | {{harvnb|Chryssides|2013|pp=}} }}</ref> Elements of hedonism are also found in various forms of ], such as ], the ], and the enduring influences of the ].<ref>{{multiref | {{harvnb|Danesi|2016|p=}} | {{harvnb|Blue|2013|loc=}} | {{harvnb|Boden|2003|p=}} | {{harvnb|Smith|1990|p=416}} }}</ref> | ||

| ==See also== | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| == References == | == References == | ||

| Line 143: | Line 132: | ||

| * {{cite book |last1=Abizadeh |first1=Arash |title=Hobbes and the Two Faces of Ethics |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-1-108-27866-9 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ZahxDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA146 |language=en |date=2018 }} | * {{cite book |last1=Abizadeh |first1=Arash |title=Hobbes and the Two Faces of Ethics |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-1-108-27866-9 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ZahxDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA146 |language=en |date=2018 }} | ||

| * {{cite book |editor1-last=Ackermann |editor1-first=Marsha E. |editor2-last=Schroeder |editor2-first=Michael J. |editor3-last=Terry |editor3-first=Janice J. |editor4-last=Upshur |editor4-first=Jiu-Hwa Lo |editor5-last=Whitters |editor5-first=Mark F. |title=Encyclopedia of World History 2: The Ancient World Prehistoric Eras to 600 CE |publisher=Facts on File |isbn=978-0-8160-6386-4 |date=2008 }} | * {{cite book |editor1-last=Ackermann |editor1-first=Marsha E. |editor2-last=Schroeder |editor2-first=Michael J. |editor3-last=Terry |editor3-first=Janice J. |editor4-last=Upshur |editor4-first=Jiu-Hwa Lo |editor5-last=Whitters |editor5-first=Mark F. |title=Encyclopedia of World History 2: The Ancient World Prehistoric Eras to 600 CE |publisher=Facts on File |isbn=978-0-8160-6386-4 |date=2008 }} | ||

| * {{cite book |last1=Adams IV |first1=Nathan A. |editor1-last=Colson |editor1-first=Charles W. |editor2-last=Cameron |editor2-first=Nigel M. de S. |title=Human Dignity in the Biotech Century: A Christian Vision for Public Policy |publisher=InterVarsity Press |isbn=978-0-8308-2783-1 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ygIiRL7mQBkC&pg=PA167 |language=en |chapter=An Unnatural Assault on Natural Law |date=2004 }} | * {{cite book |last1=Adams IV |first1=Nathan A. |editor1-last=Colson |editor1-first=Charles W. |editor2-last=Cameron |editor2-first=Nigel M. de S. |title=Human Dignity in the Biotech Century: A Christian Vision for Public Policy |publisher=InterVarsity Press |isbn=978-0-8308-2783-1 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ygIiRL7mQBkC&pg=PA167 |language=en |chapter=An Unnatural Assault on Natural Law |date=2004 }} | ||

| * {{cite |

* {{cite web |last1=Adamson |first1=Peter |title=Abu Bakr al-Razi |url=https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/abu-bakr-al-razi/ |website=The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy |publisher=Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University |access-date=4 November 2024 |date=2021 }} | ||

| * {{cite book |last1=Adamson |first1=Peter |title=Al-Rāzī |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=9780197555033 |date=2021a }} | |||

| * {{cite book |last1=Airaksinen |first1=Timo |title=The Philosophy of the Marquis de Sade |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-0-415-11228-4 |date=1995 }} | |||

| * {{cite book |last1=Alexander |first1=Bruce K. |last2=Shelton |first2=Curtis P. |title=A History of Psychology in Western Civilization |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-1-139-99183-4 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=9YTXAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA143 |language=en |date=2014 }} | * {{cite book |last1=Alexander |first1=Bruce K. |last2=Shelton |first2=Curtis P. |title=A History of Psychology in Western Civilization |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-1-139-99183-4 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=9YTXAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA143 |language=en |date=2014 }} | ||

| * {{cite book |last1=Alston |first1=William |title=The Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 7: Oakeshott - Presupposition |publisher=Macmillan Reference |isbn=0-02-865787- |

* {{cite book |last1=Alston |first1=William |title=The Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 7: Oakeshott - Presupposition |publisher=Macmillan Reference |isbn=978-0-02-865787-5 |edition=2 |chapter=Pleasure |date=2006 |url=https://www.encyclopedia.com/medicine/anatomy-and-physiology/anatomy-and-physiology/pleasure}} | ||

| * {{cite web |author1=American Psychological Association |title=Anhedonia |url=https://dictionary.apa.org/anhedonia |website=APA Dictionary of Psychology |language=en |date=2018 |publisher=American Psychological Association }} | * {{cite web |author1=American Psychological Association |title=Anhedonia |url=https://dictionary.apa.org/anhedonia |website=APA Dictionary of Psychology |language=en |date=2018 |publisher=American Psychological Association }} | ||

| * {{cite book |last1=Asmis |first1=Elizabeth |editor1-last=Harris |editor1-first=William V. |title=Pain and Pleasure in Classical Times |publisher=Brill |isbn=978-90-04-37950-3 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ZpByDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA1 |language=en |chapter=Lucretian Pleasure |date=2018 }} | * {{cite book |last1=Asmis |first1=Elizabeth |editor1-last=Harris |editor1-first=William V. |title=Pain and Pleasure in Classical Times |publisher=Brill |isbn=978-90-04-37950-3 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ZpByDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA1 |language=en |chapter=Lucretian Pleasure |date=2018 }} | ||

| * {{cite book |last1=Aufderheide |first1=Joachim |title=Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics Book X: Translation and Commentary |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-1-108-86128-1 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=F5jIDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA57 |language=en |chapter=Commentary |date=2020 }} | * {{cite book |last1=Aufderheide |first1=Joachim |title=Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics Book X: Translation and Commentary |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-1-108-86128-1 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=F5jIDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA57 |language=en |chapter=Commentary |date=2020 }} | ||

| * {{cite journal |last1=Bartoshuk |first1=Linda |title=The Measurement of Pleasure and Pain |journal=Perspectives on Psychological Science |volume=9 |issue=1 |doi=10.1177/1745691613512660 |date=2014 }} | * {{cite journal |last1=Bartoshuk |first1=Linda |title=The Measurement of Pleasure and Pain |journal=Perspectives on Psychological Science |volume=9 |issue=1 |doi=10.1177/1745691613512660 |date=2014 |pages=91–93 |pmid=26173247 }} | ||

| * {{cite book |last1=Besser |first1=Lorraine L. |title=The Philosophy of Happiness: An Interdisciplinary Introduction |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-315-28367-8 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=9yUAEAAAQBAJ&pg=PT12 |language=en |chapter=5. Happiness as Satisfaction |date=2020 }} | * {{cite book |last1=Besser |first1=Lorraine L. |title=The Philosophy of Happiness: An Interdisciplinary Introduction |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-315-28367-8 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=9yUAEAAAQBAJ&pg=PT12 |language=en |chapter=5. Happiness as Satisfaction |date=2020 }} | ||

| * {{cite book |last1=Bishop |first1=Paul |editor1-last=Acharya |editor1-first=Vinod |editor2-last=Johnson |editor2-first=Ryan J. |title=Nietzsche and Epicurus |publisher=Bloomsbury |isbn=978-1-350-08631-9 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=IYLPDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA110 |language=en |chapter=Nietzsche, Hobbes and the Tradition of Political Epicureanism |date=2020 }} | * {{cite book |last1=Bishop |first1=Paul |editor1-last=Acharya |editor1-first=Vinod |editor2-last=Johnson |editor2-first=Ryan J. |title=Nietzsche and Epicurus |publisher=Bloomsbury |isbn=978-1-350-08631-9 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=IYLPDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA110 |language=en |chapter=Nietzsche, Hobbes and the Tradition of Political Epicureanism |date=2020 }} | ||

| * {{cite book |last1=Blakemore |first1=Colin |last2=Jennett |first2=Sheila |title=The Oxford Companion to the Body |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-852403-8 |url=https://www.encyclopedia.com/philosophy-and-religion/philosophy/philosophy-terms-and-concepts/hedonism |language=en |chapter=Hedonism |date=2001 }} | * {{cite book |last1=Blakemore |first1=Colin |last2=Jennett |first2=Sheila |title=The Oxford Companion to the Body |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-852403-8 |url=https://www.encyclopedia.com/philosophy-and-religion/philosophy/philosophy-terms-and-concepts/hedonism |language=en |chapter=Hedonism |date=2001 }} | ||

| * {{cite book |last1=Blue |first1=Ronald |title=Evangelism and Missions |publisher=Thomas Nelson |isbn=978-0-529-10348-2 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=1Ux1CwAAQBAJ&pg=PT48 |language=en |date=2013 }} | * {{cite book |last1=Blue |first1=Ronald |title=Evangelism and Missions |publisher=Thomas Nelson |isbn=978-0-529-10348-2 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=1Ux1CwAAQBAJ&pg=PT48 |language=en |date=2013 }} | ||

| * {{cite book |last1=Boden |first1=Sharon |title=Consumerism, Romance and the Wedding Experience |publisher=Springer |isbn=978-0-230-00564-8 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3EGEDAAAQBAJ&pg=PA25 |language=en |date=2003 }} | * {{cite book |last1=Boden |first1=Sharon |title=Consumerism, Romance and the Wedding Experience |publisher=Springer |isbn=978-0-230-00564-8 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3EGEDAAAQBAJ&pg=PA25 |language=en |date=2003 }} | ||

| * {{cite book |last1=Bowie |first1=Norman E. |last2=Simon |first2=Robert L. |title=The Individual and the Political Order: An Introduction to Social and Political Philosophy |publisher=Rowman & Littlefield |isbn=978-0-8476-8780-0 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=rhbSquEOBHcC&pg=PA25 |language=en |date=1998 }} | * {{cite book |last1=Bowie |first1=Norman E. |last2=Simon |first2=Robert L. |title=The Individual and the Political Order: An Introduction to Social and Political Philosophy |publisher=Rowman & Littlefield |isbn=978-0-8476-8780-0 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=rhbSquEOBHcC&pg=PA25 |language=en |date=1998 }} | ||

| * {{cite book |last1=Brandt |first1=Richard B. |title=The Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 4: Gadamer - Just |

* {{cite book |last1=Brandt |first1=Richard B. |title=The Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 4: Gadamer - Just War Theory |publisher=Macmillan Reference |isbn=978-0-02-865784-4 |edition=2 |chapter=Hedonism |date=2006 }} | ||

| * {{cite web |last1=Bruton |first1=Samuel V. |title=Psychological Hedonism |url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/psychological-hedonism |website=Encyclopædia Britannica |publisher=Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. |access-date=25 October 2024 |language=en |date=2024}} | * {{cite web |last1=Bruton |first1=Samuel V. |title=Psychological Hedonism |url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/psychological-hedonism |website=Encyclopædia Britannica |publisher=Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. |access-date=25 October 2024 |language=en |date=2024}} | ||

| * {{cite book |last1=Bunnin |first1=Nicholas |last2=Yu |first2=Jiyuan |title=The Blackwell Dictionary of Western Philosophy |date=2009 |publisher=John Wiley & Sons |isbn=978-1-4051-9112-8 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=M7ZFEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA134 |language=en |access-date=January 3, 2024 }} | * {{cite book |last1=Bunnin |first1=Nicholas |last2=Yu |first2=Jiyuan |title=The Blackwell Dictionary of Western Philosophy |date=2009 |publisher=John Wiley & Sons |isbn=978-1-4051-9112-8 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=M7ZFEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA134 |language=en |access-date=January 3, 2024 }} | ||

| * {{cite web |last1=Buscicchi |first1=Lorenzo |title=Paradox of Hedonism |url=https://iep.utm.edu/paradox-of-hedonism/ |website=Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy |access-date=19 October 2024}} | * {{cite web |last1=Buscicchi |first1=Lorenzo |title=Paradox of Hedonism |url=https://iep.utm.edu/paradox-of-hedonism/ |website=Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy |access-date=19 October 2024}} | ||

| * {{cite book |last1=Campbell |first1=Robert Jean |title=Campbell's Psychiatric Dictionary |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-534159-1 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=76vPu_G2UkgC&pg=PA449 |language=en |date=2009 }} | * {{cite book |last1=Campbell |first1=Robert Jean |title=Campbell's Psychiatric Dictionary |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-534159-1 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=76vPu_G2UkgC&pg=PA449 |language=en |date=2009 }} | ||