| Revision as of 00:48, 28 August 2018 edit108.46.255.188 (talk) →Storyline: Fixed errorTags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 16:29, 4 January 2025 edit undoMonkeytown0552 (talk | contribs)100 edits rewrite to clean up some languageTags: Mobile edit Mobile app edit iOS app edit App section source | ||

| (556 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{multiple issues| | |||

| {{refimprove|date=October 2024}} | |||

| {{original research|date=October 2024}}}} | |||

| {{short description|1983 American television film by Nicholas Meyer}} | |||

| {{Redirect|Russell Oakes |the Australian dramatist |Russell J. Oakes}} | |||

| {{about|the 1983 television film}} | {{about|the 1983 television film}} | ||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=July 2012}} | {{Use mdy dates|date=July 2012}} | ||

| {{Infobox television | {{Infobox television | ||

| | show_name = The Day After | |||

| | image = The Day After (film).jpg | | image = The Day After (film).jpg | ||

| | caption = | | caption = | ||

| | genre = Drama | | genre = Drama<br />Disaster<br />Science fiction | ||

| | creator = | | creator = | ||

| | based_on = | | based_on = | ||

| Line 18: | Line 22: | ||

| | language = English | | language = English | ||

| | num_episodes = | | num_episodes = | ||

| | producer = Robert Papazian |

| producer = Robert Papazian | ||

| | editor = William Paul Dornisch<br />Robert Florio | | editor = William Paul Dornisch<br />Robert Florio | ||

| | cinematography = ] | | cinematography = ] | ||

| | runtime = 126 minutes | | runtime = 126 minutes | ||

| | company = ] | | company = ] | ||

| | distributor = ]<br />] | |||

| | budget = | | budget = | ||

| | network = ABC | | network = ] | ||

| | |

| released = {{Start date|1983|11|20}} | ||

| | last_aired = | |||

| | website = | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''''The Day After''''' is an American ] that first aired on November 20, 1983, on the ] television network. The film postulates a fictional war between the ] and the ] over ] that rapidly escalates into a full-scale ] between the ] and the ]. The action itself focuses on the residents of ] and ], and several family farms near American ]s.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/articles/5flHQwTXN65VCVb5vgkMtGC/the-day-after-25-november-1983|title=The Day After - 25 November 1983|publisher=BBC|language=en|access-date=18 September 2016}}</ref> The cast includes ], ], ], ], and ]. The film was written by ], produced by Robert Papazian, and directed by ]. | |||

| '''''The Day After''''' is an American ] that first aired on November 20, 1983, on the ] television network. More than 100 million people, in nearly 39 million households, watched the program during its initial broadcast.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://time.com/3101529/the-day-after/|title=ALL-TIME 100 TV Shows: The Day After |last=Poniewozik |first=James |work=]|date=6 September 2007|accessdate=17 January 2017}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|title=Tipoff|url=https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=8rROAAAAIBAJ&sjid=BvwDAAAAIBAJ&pg=1194,1429539&dq=jobeth+williams+tv+movie+nielsen+ratings&hl=en|accessdate=October 11, 2011|newspaper=The Ledger|date=20 January 1989}}</ref><ref name=zap2it>{{cite news|url=http://tvbythenumbers.zap2it.com/reference/top-100-rated-tv-shows-of-all-time/|title=Top 100 Rated TV Shows Of All Time|work=]|publisher=]|date=21 March 2009|accessdate=17 January 2017}}</ref> With a 46 rating and a 62% ] of the viewing audience during its initial broadcast, it was the seventh highest rated non-sports show up to that time and set a record as the highest-rated television film in history—a record it still held as recently as a 2009<!--- Help. Unable to find a newer list of all time top-100, which is needed to get past all the Super Bowls on top 20 lists --> report.<ref name=zap2it/> | |||

| More than 100 million people, in nearly 39 million households, watched the film during its initial broadcast.<ref>{{cite magazine|url=https://time.com/3101529/the-day-after/|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141025122000/https://time.com/3101529/the-day-after/|url-status=dead|archive-date=October 25, 2014|title=ALL-TIME 100 TV Shows: The Day After |last=Poniewozik |first=James |magazine=]|date=6 September 2007|access-date=17 January 2017}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|title=Tipoff|url=https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=8rROAAAAIBAJ&pg=1194,1429539&dq=jobeth+williams+tv+movie+nielsen+ratings&hl=en|access-date=October 11, 2011|newspaper=The Ledger|date=20 January 1989}}</ref><ref name="zap2it">{{cite news|url=https://tvbythenumbers.zap2it.com/reference/top-100-rated-tv-shows-of-all-time/|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161013204918/http://tvbythenumbers.zap2it.com/reference/top-100-rated-tv-shows-of-all-time/|url-status=dead|archive-date=13 October 2016|title=Top 100 Rated TV Shows Of All Time|work=]|publisher=]|date=21 March 2009|access-date=17 January 2017}}</ref> With a 46 rating and a 62% ] of the viewing audience during the initial broadcast, the film was the seventh-highest-rated non-sports show until then, and in a 2009 Nielsen TV Ratings list was one of the highest-rated television films in US history.<ref name="zap2it" /> | |||

| The film postulates a fictional war between ] forces and the ] countries that rapidly escalates into a full-scale ] between the United States and the Soviet Union. The action itself focuses on the residents of ] and ], as well as several family farms situated near nuclear ]s.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/articles/5flHQwTXN65VCVb5vgkMtGC/the-day-after-25-november-1983|title=The Day After - 25 November 1983|publisher=BBC|language=English|accessdate=18 September 2016}}</ref> | |||

| The film was broadcast on ] in 1987,<ref>{{Cite web |title=«На следующий день» (The Day After, 1983) |url=https://www.kinopoisk.ru/film/257368/ |access-date=2021-10-18 |website=КиноПоиск}}</ref> during the negotiations on ]. The producers demanded the ] translation conform to the original script and the broadcast not be interrupted by commentary.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Soviet Union to air ABC's 'The Day After' |url=https://www.upi.com/Archives/1987/01/10/Soviet-Union-to-air-ABCs-The-Day-After/5242537253200/}}</ref> | |||

| The cast includes ], ], ], ], and ]. The film was written by ], produced by Robert Papazian, and directed by ]. It was released on ] on May 18, 2004, by ]. | |||

| ==Plot== | == Plot == | ||

| <!-- Per WP:FILMPLOT, plot summaries for feature films should be set between 400 to 700 words. --> | |||

| The story follows several citizens—and people they encounter—in and around ] and the college town of ], {{convert|40|mi}} to its west. | |||

| Dr. Russell Oakes works at a hospital in ], and spends time with family as his daughter Marilyn prepares to move away. In ], 40 miles southeast, farmer Jim Dahlberg and family hold a wedding rehearsal for his eldest daughter Denise, with family drama trying to keep the couple's hands off each other. Airman First Class Billy McCoy, serving with the ], is stationed at a ] launch site in nearby Sweetsage, Missouri, one of many such silos in western Missouri. Next to the site, the Hendrys tend to their farm chores and mind their children. Background television and radio reports reveal information about a ] buildup on the ] border. East Germany blockades ], and the United States issues an ] and places its forces on alert, recalling McCoy from his wife and infant child at ] near ]. | |||

| The following day, ] forces attempt to break the blockade through ]. ] ] hit Würzburg, ]. The characters' attempts to continue life as normal become increasingly strained as overseas tensions escalate rapidly. Moscow is evacuated. At the ] in ], 38 miles west of Kansas City, the word goes out that the Soviets have invaded ]. Soviet forces drive through the ] toward the ] in an armored thrust, defying NATO policy of defense including ]. Pre-med student Stephen Klein decides to hitchhike home to ], while Denise's fiancé Bruce witnesses a crowd of shoppers frantically pulling items off the shelves as both sides attack naval targets in the Persian Gulf. Jim prepares his cellar and others'. People start to flee Kansas City, and the ] is activated on home and car radios. NATO attempts to halt the advance by ] three nuclear warheads over Soviet troops, while a Soviet nuclear device destroys the NATO regional military headquarters in Brussels. Air Force personnel aboard the airborne ] plane receive notification of an incoming ICBM attack on the continental United States with 300 missiles being launched from Russia. They activate their missile launch protocols. Ultimately characters watch the ] streak toward Russia, as above Kansas the ] ] tracks a full-scale Soviet attack. The film leaves who fired first deliberately unclear. | |||

| The film's narrative is structured as a before-during-after scenario of a nuclear attack: the first segment introduces the various characters and their stories; the second shows the nuclear disaster itself; and the third details the effects of the fallout on the characters. | |||

| McCoy flees his now-empty silo, telling his fellow soldiers the war's over and their job's done. A ]'s ] disables vehicles and destroys the power grid. Nuclear missiles rain across the region on both ] and ]. Kansas City's last minutes are frantic. Bruce, Marilyn Oakes, and McCoy's family are among the thousands of people incinerated, while the young Danny Dahlberg is ]. The oblivious Hendrys never make it out of their yard. Dr. Oakes, stranded on the highway between Kansas City and Lawrence, walks to University Hospital at Lawrence, takes charge, and begins treating patients. Klein finds the Dahlberg home and begs for refuge in the family's basement. | |||

| During the first segment, as the characters are introduced, the chronology of events leading up to the war is depicted entirely via television and radio news broadcasts as well as communications among US military personnel and hearsay, enhanced by characters' reactions and analysis of the events. | |||

| Oakes receives ] reports by ] from KU professor Joe Huxley in the science building: travel outdoors is fatal. Patients still continue to come, having no shelter, option, or knowledge of the danger, and supplies dwindle. Delirious after days in the basement shelter, Denise runs outside; Klein retrieves her, but both are exposed to the thick radioactive dust that killed the Dahlbergs' livestock. McCoy heads towards Sedalia until he learns of its destruction from passing refugees. He befriends a mute man and travels to the hospital, where he dies of ]. Oakes bonds with Nurse Nancy Bauer, who dies of ], and a pregnant woman pleads with him to tell her she's wrong to be hopeless. | |||

| ===Chronology of the war=== | |||

| {{Infobox military conflict | |||

| | conflict = World War III (fictional) | |||

| | partof = | |||

| | image = Dayafter1.jpg | |||

| | caption = A (fictional) nuclear weapon detonates near ]. | |||

| | date = September 15-16, 1989 | |||

| | place = Initially ]; eventually ], ], and the ] | |||

| | causes = Blockading of ] | |||

| | result = *] between the United States and Soviet Union | |||

| | combatant1 = {{flag|NATO}} | |||

| *{{Flagcountry|US|1960}} | |||

| *{{Flagcountry|UK}} | |||

| *{{Flagcountry|FRG|1949}} | |||

| | combatant2 = ] | |||

| *{{USSR}} | |||

| *{{GDR}} | |||

| |Commanders and leaders | |||

| | commander1 = NATO:<br>{{flagicon|US|1960}} ]<br /> {{flagicon|United Kingdom}} ]<br />{{flagicon|FRG|1949}} ] | |||

| | commander2 = Warsaw Pact:<br>{{flagicon|USSR}} ]<br /> {{flagicon|GDR}} ] | |||

| | notes = | |||

| }} | |||

| In a radio speech, the ] announces a ceasefire, promises relief, and stresses no surrender and a reliance on American principles, set to shots of filthy, listless, or dead Americans among the ruins. Attempts at aid from the ] and infrastructural redevelopment prove fruitless, and ]s become commonplace. Jim Dahlberg is eventually killed by ], while Denise, Klein, and Oakes are wasting away from radiation sickness. Returning to Kansas City to see his old home one last time, Oakes witnesses National Guardsmen blindfolding and executing looters. He finds squatters in the ruins of his home and attempts to drive them off, but is instead offered food. Oakes collapses and weeps, and one of the squatters comforts him. The film ends with an overlying audio clip of Huxley's voice on the radio as the screen fades to black, asking if anybody can still hear him, only to be met with silence until the credits, as a ] signal transmits a single message to the viewer: ]. | |||

| The ] is shown to have commenced a military buildup in ] (which the Soviets insist are ] exercises) with the goal of intimidating the United States, the United Kingdom, and France into withdrawing from ]. When the United States does not back down, Soviet armored divisions are sent to the border between East and West Germany. | |||

| Most versions of ''The Day After'' include a textual ending disclaimer just before the end credits, stating that the film is fictional and that the real-life outcome of a nuclear war would be much worse than the events portrayed onscreen. | |||

| During the late hours of Friday, September 15, news broadcasts report a "widespread rebellion among several divisions of the ]." As a result, the Soviets ] West Berlin. Tensions mount, and the United States issues an ultimatum that the Soviets stand down from the blockade by 6:00 a.m. the next day, and noncompliance will be interpreted as an act of war. The Soviets refuse, and the President of the United States orders all U.S. military forces around the world on ] 2 alert. | |||

| On Saturday, September 16, ] forces in West Germany invade East Germany through the ] to free Berlin. The Soviets hold the Marienborn corridor and inflict heavy casualties on NATO troops. Two Soviet ]s cross into West German airspace and bomb a NATO munitions storage facility, also striking a school and a hospital. A subsequent radio broadcast states that Moscow is being evacuated. At this point, major U.S. cities begin mass evacuations as well. There soon follow unconfirmed reports that nuclear weapons were used in ] and ]. Meanwhile, in the ], naval warfare erupts, as radio reports tell of ship sinkings on both sides. | |||

| Eventually, the ] reaches the ]. Seeking to prevent Soviet forces from invading France and causing the rest of ] to fall, NATO halts the Soviet advance by ] three low-yield ] over advancing Soviet troops. Soviet forces counter by launching a nuclear strike on NATO headquarters in Brussels. In response, the United States ] begins scrambling ] bombers. | |||

| The Soviet Air Force then destroys a ] station at ], England and another at ] in California. Meanwhile, on board the ] aircraft, the order comes in from the President for a full nuclear strike against the Soviet Union. Almost simultaneously, an Air Force officer receives a report that a massive Soviet nuclear assault against the United States has been launched, further updated with a report that over 300 Soviet ] (ICBMs) are inbound. It is deliberately unclear in the film whether the Soviet Union or the United States launches the main nuclear attack first. | |||

| The first salvo of the Soviet nuclear attack on the central United States (as shown from the point of view of the residents of Central Kansas and western Missouri) occurs at 3:38 p.m. Central Daylight Time, when a large-yield nuclear weapon air bursts at high altitude over Kansas City, Missouri. This generates an ] (EMP) that shuts down the electric power grid to nearby ]'s operable ] missile silos and of the surrounding areas. Thirty seconds later, incoming Soviet ICBMs begin to hit military and population targets. Higginsville, Kansas City, ], and all the way south to ] are blanketed with ] nuclear weapons. While the story provides no specifics, it strongly suggests that U.S. cities, military, and industrial bases are heavily damaged or destroyed. The aftermath depicts the central and northwestern United States as a blackened wasteland of burned-out cities filled with burn, blast, and radiation victims. Eventually, the U.S. president delivers a radio address in which he declares there is now a ceasefire between the United States and the Soviet Union (which, although not shown, has suffered the same devastating effects) and states there has not been any surrender by the United States. | |||

| ===Storyline=== | |||

| Dr. Russell Oakes lives in the upper-class Brookside neighborhood with his wife and works in a hospital in downtown Kansas City. He is scheduled to teach a ] class at the ] (KU) hospital in nearby Lawrence, Kansas, and is ''en route'' when he hears an alarming ] alert on his car radio. The ] attention signal vibrates and then a female announces an advisory message. He exits the crowded freeway and attempts to contact his wife but gives up due to the long line at a phone booth. Oakes attempts to return to his home via the ] and is the only eastbound motorist. The nuclear attack begins, and Kansas City is gripped with panic as air raid sirens wail. Oakes' car is permanently disabled by the EMP from the first high altitude detonation, as are all motor vehicles and electricity. Oakes is about {{convert|30|mi}} away from downtown when the missiles hit. His family, many colleagues, and almost all of Kansas City's population are killed. He walks {{convert|10|mi}} to Lawrence, which has been severely damaged from the blasts, and, at the university hospital, treats the wounded with Dr. Sam Hachiya and Nurse Nancy Bauer. Also at the university, science Professor Joe Huxley and students use a ] to monitor the level of ] outside. They build a makeshift radio to maintain contact with Dr. Oakes at the hospital as well as to locate any other broadcasting survivors beyond their area. | |||

| ] Billy McCoy is stationed at a ] missile silo near ], {{convert|70|mi|km}} east-southeast of Kansas City, and is called to duty during the ] alert. His crew are among the first to witness the initial missile launches, indicating full-scale nuclear war. After it becomes clear that a Soviet ] is imminent, the airmen panic. Several stubbornly insist that they should stay at their post and take shelter in the silo, while others, including McCoy, point out that it is futile because the silo will not withstand a direct hit. McCoy tells them they have done their jobs and speeds away in an Air Force truck to retrieve his wife and child in Sedalia ({{convert|20|mi|km}} east of Whiteman AFB), but the truck is permanently disabled by an EMP from an airburst detonation. McCoy abandons the truck and takes shelter inside an overturned semi truck trailer, barely escaping the oncoming nuclear blast. After the attack, McCoy walks towards a town and finds an abandoned store, where he takes candy bars and other provisions, while gunfire is heard in the distance. While standing in line for a drink of water from a well pump, McCoy befriends a man who is mute and shares his provisions. McCoy asks another man along the road about Sedalia, and the man indicates that Sedalia and Windsor no longer exist. As McCoy and his companion both begin to suffer the effects of ], they leave a refugee camp and head to the hospital at Lawrence, where McCoy ultimately succumbs to the radiation sickness. | |||

| Farmer Jim Dahlberg and his family live in rural ], very close to a field of missile silos about {{convert|37|mi}} south-southeast of Kansas City. While the family is preparing for the wedding of their elder daughter, Denise, to KU senior Bruce Gallatin, Jim prepares for the impending attack by converting their basement into a makeshift fallout shelter. As the missiles are launched, he forcefully carries his wife Eve, who refuses to accept the reality of the escalating crisis and continues making wedding preparations, downstairs into the basement. While running to the shelter, the Dahlbergs' son, Danny, inadvertently looks behind him just as a missile detonates in the distance and is instantly blinded and carried back to the shelter by Dahlberg. | |||

| KU student Stephen Klein, while hitchhiking home to ], stumbles upon the farm and persuades the Dahlbergs to take him in. After several days in the basement, Denise, distraught over the situation and the unknown whereabouts of Bruce, who, unbeknownst to her, was killed in the attack, escapes from the basement and runs about the field that is cluttered with dead animals. She sees a clear blue sky and thinks the worst is over. However, the field is actually covered in radioactive fallout. Klein goes after her, attempting to warn her about the effects of the invisible nuclear radiation that is going through her cells like ], but Denise, ignoring this warning, tries to run from him. Eventually, Klein is able to chase Denise back to safety in the basement, but not before Denise runs to the stairs to find her wedding dress. During a makeshift church service, while the minister tries to express how lucky they are to have survived, Denise begins to bleed externally from her groin due to radiation sickness from her run through the field. | |||

| Klein takes Danny and Denise to Lawrence for treatment. Dr. Hachiya attempts to treat Danny, and Klein also develops radiation sickness. Dahlberg, upon returning from an emergency farmers' meeting, confronts a group of silent survivors ] on his farm and attempts to persuade them to move somewhere else, only to be shot and killed mid-sentence by one of the silent survivors. | |||

| Ultimately, the situation at the hospital becomes grim. Dr. Oakes collapses from exhaustion and, upon awakening several days later, learns that Nurse Bauer has died from ]. Oakes, suffering from terminal radiation sickness, decides to return to Kansas City to see his home for the last time, while Dr. Hachiya stays behind. Oakes hitches a ride on an ] truck, where he witnesses US military personnel blindfolding and executing looters. After somehow managing to locate where his home was, he finds the charred remains of his wife's wristwatch and a family huddled in the ruins. Oakes angrily orders them to leave his home. The family silently offers Oakes food, causing him to collapse in despair, as a member of the family comforts him. | |||

| As the scene fades to black, Professor Huxley calls into his makeshift radio: "Hello? Is anybody there? Anybody at all?" There is no response. | |||

| ==Cast== | |||

| {{col-begin}} | |||

| {{col-break}} | |||

| ;'''The Oakes''' | |||

| *] as Dr. Russell Oakes | |||

| *] as Helen Oakes | |||

| *Kyle Aletter as Marilyn Oakes | |||

| == Cast == | |||

| ;'''The Dahlbergs''' | |||

| {{col-begin}}{{col-break}} | |||

| *] as Jim Dahlberg | |||

| ; '''The Oakeses''' | |||

| *] as Eve Dahlberg | |||

| * ] as Dr. Russell Oakes | |||

| *Lori Lethin as Denise Dahlberg | |||

| * ] as Helen Oakes | |||

| *Doug Scott as Danny Dahlberg | |||

| * Kyle Aletter as Marilyn Oakes | |||

| *Ellen Anthony as Joleen Dahlberg | |||

| ;''' |

; '''The Dahlbergs''' | ||

| *] as |

* ] as Jim Dahlberg | ||

| *] as |

* ] as Eve Dahlberg | ||

| * ] as Denise Dahlberg | |||

| *Lin McCarthy as Dr. Austin | |||

| * Doug Scott as Danny Dahlberg | |||

| *] as Dr. Wallenberg | |||

| * Ellen Anthony as Joleen Dahlberg | |||

| *] as Dr. Landowska | |||

| *Jonathan Estrin as Julian French | |||

| ; '''Hospital staff''' | |||

| * ] as Nurse Nancy Bauer | |||

| * Calvin Jung as Dr. Sam Hachiya | |||

| * ] as Dr. Austin | |||

| * ] as Dr. Wallenberg | |||

| * ] as Dr. Landowska | |||

| * Jonathan Estrin as Julian French | |||

| * ] as Man in Hospital | |||

| {{col-break}} | {{col-break}} | ||

| ;'''Others''' | ; '''Others''' | ||

| *] as Stephen Klein | * ] as Stephen Klein | ||

| *] as Joe Huxley | * ] as Joe Huxley | ||

| *] as Alison Ransom | * ] as Alison Ransom | ||

| *] as Airman First Class Billy McCoy | * ] as Airman First Class Billy McCoy | ||

| *] as Bruce Gallatin | * ] as Bruce Gallatin | ||

| *] as Reverend Walker | * ] as Reverend Walker | ||

| *Clayton Day as Dennis Hendry | * Clayton Day as Dennis Hendry | ||

| *Antonie Becker as Ellen Hendry | * Antonie Becker as Ellen Hendry | ||

| *] as Aldo | * ] as Aldo | ||

| *] as Tom Cooper | * ] as Tom Cooper | ||

| *Stan Wilson as Vinnie Conrad | * Stan Wilson as Vinnie Conrad | ||

| *] as Man at phone | * ] as Man at phone | ||

| {{col-end}} | {{col-end}} | ||

| ==Production== | == Production == | ||

| {{unreferenced section|date= |

{{unreferenced section|date=February 2024}} | ||

| ''The Day After'' was the idea of ABC Motion Picture Division |

''The Day After'' was the idea of ABC Motion Picture Division President ],<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2014/12/24/business/media/brandon-stoddard-77-abc-executive-who-brought-roots-to-tv-is-dead.html|title=Brandon Stoddard, 77, ABC Executive Who Brought 'Roots' to TV, Is Dead|last=Weber|first=Bruce|date=2014-12-23|newspaper=The New York Times|issn=0362-4331|access-date=2016-03-18}}</ref> who, after watching '']'', was so impressed that he envisioned creating a film exploring the effects of nuclear war on the United States. Stoddard asked his executive vice president of television movies and miniseries, Stu Samuels, to develop a script. Samuels created the title ''The Day After'' to emphasize that the story was about, not a nuclear war itself, but the aftermath. Samuels suggested several writers, and eventually, Stoddard commissioned the veteran television writer ] to write the script in 1981. ABC, which financed the production, was concerned about the graphic nature of the film and how to portray the subject appropriately on a family-oriented television channel. Hume undertook a massive amount of research on nuclear war and went through several drafts until ABC finally deemed the plot and characters acceptable. | ||

| ].]] | |||

| Originally, the film was based more around and in Kansas City, Missouri. Kansas City was not bombed in the original script although ] was, which made Kansas City suffer shock waves and the horde of survivors staggering into town. There was no Lawrence, Kansas in the story although there was a small Kansas town called "Hampton." While Hume was writing the script, he and the producer Robert Papazian, who had great experience in on-location shooting, took several trips to Kansas City to scout locations and met with officials from the Kansas film commission and from the Kansas tourist offices to search for a suitable location for "Hampton." It came down to a choice of either ], and Lawrence, Kansas, both college towns. Warrensburg was home of ] and was near Whiteman Air Force Base, and Lawrence was home of the ] and was near Kansas City. Hume and Papazian ended up selecting Lawrence because of the access to a number of good locations: a university, a hospital, football and basketball venues, farms, and a flat countryside. Lawrence was also agreed upon as being the "geographic center" of the United States. The Lawrence people were urging ABC to change the name "Hampton" to "Lawrence" in the script. | |||

| Back in Los Angeles, the idea of making a TV movie showing the true effects of nuclear war on average American citizens was still stirring up controversy. ABC, Hume, and Papazian realized that for the scene depicting the nuclear blast, they would have to use state-of-the-art special effects and so took the first step by hiring some of the best special effects people in the business to draw up some ] for the complicated blast scene. ABC then hired Robert Butler to direct the project. For several months, the group worked on drawing up storyboards and revising the script again and again. Then, in early 1982, Butler was forced to leave ''The Day After'' because of other contractual commitments. ABC then offered the project to two other directors, who both turned it down. Finally, in May, ABC hired the feature film director ], who had just completed the blockbuster '']''. Meyer was apprehensive at first and doubted ABC would get away with making a television film on nuclear war without the censors diminishing its effect. However, after reading the script, Meyer agreed to direct ''The Day After''. | |||

| Originally, the film was based more around and in Kansas City, Missouri. Kansas City was not bombed in the original script, although ] was, making Kansas City suffer shock waves and the horde of survivors staggering into town. There was no Lawrence, Kansas in the story, although there was a small Kansas town called "Hampton". While Hume was writing the script, he and producer Robert Papazian, who had great experience in on-location shooting, took several trips to Kansas City to scout locations and met with officials from the Kansas film commission and from the Kansas tourist offices to search for a suitable location for "Hampton." It came down to a choice of either ] and Lawrence, Kansas, both college towns—Warrensburg was home of ] and was near Whiteman Air Force Base and Lawrence was home of the ] and was near Kansas City. Hume and Papazian ended up selecting Lawrence, due to the access to a number of good locations: a university, a hospital, football and basketball venues, farms, and a flat countryside. Lawrence was also agreed upon as being the "geographic center" of the United States. The Lawrence people were urging ABC to change the name "Hampton" to "Lawrence" in the script. | |||

| Meyer wanted to make sure that he would film the script he was offered. He did not want the censors to censor the film or the film to be a regular Hollywood disaster movie from the start. Meyer figured the more ''The Day After'' resembled such a film, the less effective it would be, and he preferred to present the facts of nuclear war to viewers. He made it clear to ABC that no big TV or film stars should be in ''The Day After''. ABC agreed but wanted to have one star to help attract European audiences to the film when it would be shown theatrically there. Later, while flying to visit his parents in New York City, Meyer happened to be on the same plane with ] and asked him to join the cast. | |||

| Back in Los Angeles, the idea of making a TV movie showing the true effects of nuclear war on average American citizens was still stirring up controversy. ABC, Hume, and Papazian realized that for the scene depicting the nuclear blast, they would have to use state-of-the-art special effects and they took the first step by hiring some of the best special effects people in the business to draw up some storyboards for the complicated blast scene. Then, ABC hired Robert Butler to direct the project. For several months, this group worked on drawing up storyboards and revising the script again and again; then, in early 1982, Butler was forced to leave ''The Day After'' because of other contractual commitments. ABC then offered the project to two other directors, who both turned it down. Finally, in May, ABC hired feature film director ], who had just completed the blockbuster '']''. Meyer was apprehensive at first and doubted ABC would get away with making a television film on nuclear war without the censors diminishing its effect. However, after reading the script, Meyer agreed to direct ''The Day After.'' | |||

| Meyer plunged into several months of nuclear research, which made him quite pessimistic about the future, to the point of becoming ill each evening when he came home from work. Meyer and Papazian also made trips to the ABC censors and to the ] during their research phase and experienced conflicts with both. Meyer had many heated arguments over elements in the script that the network censors wanted cut out of the film. The Department of Defense said that it would cooperate with ABC if the script clarified that the Soviets launched their missiles first, which Meyer and Papazian took pains not to do. | |||

| However, Meyer wanted to make sure he would film the script he was offered. He did not want the censors to censor the film, nor the film to be a regular Hollywood disaster movie from the start. Meyer figured the more ''The Day After'' resembled such a film, the less effective it would be, and preferred to present the facts of nuclear war to viewers. He made it clear to ABC that no big TV or film stars should be in ''The Day After.'' ABC agreed, although they wanted to have one star to help attract European audiences to the film when it would be shown theatrically there. Later, while flying to visit his parents in ], Meyer happened to be on the same plane with ] and asked him to join the cast. | |||

| Meyer, Papazian, Hume, and several casting directors spent most of July 1982 taking numerous trips to Kansas City. In between casting in Los Angeles, where they relied mostly on unknowns, they would fly to the Kansas City area to interview local actors and scout scenery. They were hoping to find some real Midwesterners for smaller roles. Hollywood casting directors strolled through shopping malls in Kansas City to look for local people to fill small and supporting roles, the daily newspaper in Lawrence ran an advertisement calling for local residents to sign up as extras, and a professor of theater and film at the ] was hired to head up local casting. Out of the eighty or so speaking parts, only fifteen were cast in Los Angeles. The remaining roles were filled in Kansas City and Lawrence. | |||

| Meyer plunged into several months of nuclear research, which made him quite pessimistic about the future, to point of becoming ill each evening when he came home from work. Meyer and Papazian also made trips to the ABC censors, and to the ] during their research phase, and experienced conflicts with both. Meyer had many heated arguments over elements in the script, that the network censors wanted cut out of the film. The Department of Defense said they would cooperate with ABC if the script made clear that the Soviet Union launched their missiles first—something Meyer and Papazian took pains not to do. | |||

| While in Kansas City, Meyer and Papazian toured the ] offices in Kansas City. When asked about its plans for surviving nuclear war, a FEMA official replied that it was experimenting with putting evacuation instructions in ]s in ]. "In about six years, everyone should have them." That meeting led Meyer to later refer to FEMA as "a complete joke." It was during that time that the decision was made to change "Hampton" in the script to "Lawrence." Meyer and Hume figured since Lawrence was a real town, it would be more believable, and besides, it was a perfect choice to play a representative of ]. The town boasted a "socio-cultural mix," sat near the exact ], and was a prime missile target according to Hume and Meyer's research because 150 ] silos stood nearby. Lawrence had some great locations, and its people were more supportive of the project. Suddenly, less emphasis was put on Kansas City, the decision was made to have the city annihilated in the script, and Lawrence was made the primary location in the film. | |||

| In any case, Meyer, Papazian, Hume, and several casting directors spent most of July 1982 taking numerous trips to Kansas City. In between casting in ], where they relied mostly on unknowns, they would fly to the Kansas City area to interview local actors and scenery. They were hoping to find some real Midwesterners for smaller roles. Hollywood casting directors strolled through shopping malls in Kansas City, looking for local people to fill small and supporting roles, while the daily newspaper in Lawrence ran an advertisement calling for local residents of all ages to sign up for jobs as a large number of extras in the film and a professor of theater and film at the ] was hired to head up the local casting of the movie. Out of the eighty or so speaking parts, only fifteen were cast in Los Angeles. The remaining roles were filled in Kansas City and Lawrence. | |||

| === Editing === | |||

| While in Kansas City, Meyer and Papazian toured the ] offices in Kansas City. When asked what their plans for surviving nuclear war were, a FEMA official replied that they were experimenting with putting evacuation instructions in ]s in ]. "In about six years, everyone should have them." This meeting led Meyer to later refer to FEMA as "a complete joke." It was during this time that the decision was made to change "Hampton" in the script to "Lawrence." Meyer and Hume figured since Lawrence was a real town, that it would be more believable and besides, Lawrence was a perfect choice to play a representative of ]. The town boasted a "socio-cultural mix," sat near the exact geographic center of the continental U.S., and Hume and Meyer's research told them that Lawrence was a prime missile target, because 150 ] silos stood nearby. Lawrence had some great locations, and the people there were more supportive of the project. Suddenly, less emphasis was put on Kansas City, the decision was made to have the city completely annihilated in the script, and Lawrence was made the primary location in the film. | |||

| ABC originally planned to air ''The Day After'' as a four-hour "television event" that would be spread over two nights with a total running time of 180 minutes without commercials.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Naha|first=Ed|date=April 1983|title=L.A. Offbeat: A Lesson in Reality|url=https://archive.org/details/starlog_magazine-069|journal=Starlog|pages=–25}}</ref> The director Nicholas Meyer felt the original script was padded, and suggested cutting out an hour of material to present the whole film in one night. The network stuck with its two-night broadcast plan, and Meyer filmed the entire three-hour script, as evidenced by a 172-minute ] that has surfaced.<ref>{{Citation|last=nisus8|title=The Day After (1983) - 3-Hour Workprint Version|date=2018-08-10|url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MobwUGgdI3A| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180911120906/https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MobwUGgdI3A| archive-date=2018-09-11 | url-status=dead|access-date=2019-05-23}}</ref> Subsequently, the network found that it was difficult to find advertisers because of the subject matter {{Contradictory inline|reason=The first sentence of this paragraph indicates the network planned to air the movie without commercials.|date=September 2024}}. ABC relented and allowed Meyer to edit the film for a one-night broadcast version. Meyer's original single-night cut ran two hours and twenty minutes, which he presented to the network. After that screening, many executives were deeply moved, and some even cried, which led Meyer to believe they approved of his cut. | |||

| Nevertheless, a further six-month struggle ensued over the final shape of the film. Network censors had opinions about the inclusion of specific scenes, and ABC itself was eventually intent on "trimming the film to the bone" and made demands to cut out many scenes that Meyer strongly lobbied to keep. Finally, Meyer and his editor, Bill Dornisch, balked. Dornisch was fired, and Meyer walked away from the project. ABC brought in other editors, but the network ultimately was not happy with the results they produced. It finally brought Meyer back and reached a compromise, with Meyer paring down ''The Day After'' to a final running time of 120 minutes.<ref name="fallout">{{cite web|last=Niccum|first=John|title=Fallout from ''The Day After''|url=http://www.lawrence.com/news/2003/nov/19/fallout_from/|work=lawrence.com|access-date=October 11, 2011|date=2003-11-19}}</ref><ref>Meyer, Nicholas, "The View From the Bridge: Memories of Star Trek and a Life in Hollywood", page 150. Viking Adult, 2009</ref> | |||

| ===Filming=== | |||

| {{unreferenced section|date=July 2014}} | |||

| ] Courthouse in downtown Lawrence, Kansas, the town where much of ''The Day After'' takes place.]] | |||

| Production began on Monday, August 16, 1982, at a farm just west of Lawrence. Sunshine was needed but it turned out to be an overcast day. The set required a floodlight. The crew set fire to the farm's red barn for one scene during the blast sequence, though this shot was eventually cut. The owner of the farm was not paid, but ABC did compensate him by building a new barn. A set in rural Lawrence, depicting a schoolhouse, was made in six days from ] "skins." On Monday, August 30, 1982, ABC shut down Rusty's IGA supermarket in Lawrence's Hillcrest Shopping Center from 7 a.m. until 2 p.m. to shoot a scene representing ]. A local man and his infant son came to the market, apparently unaware that ABC was filming a movie. The man reportedly saw the chaos and ran back into his car in fear. | |||

| === ''The Day Before'' campaign === | |||

| Local extras were paid $75 to shave heads bald, have prosthetic latex scar tissue and burn-marks affixed to their faces, be plastered with coats of artificial mud, and be dressed in tattered clothes for scenes of radiation sickness. They were requested not to bathe or shower until filming was completed. In a small Lawrence park, ABC set up a grimy shantytown to serve as home to survivors. It was known as "Tent City." On Friday, September 3, 1982, the cameras rolled with many students as extras. The next day, ], the best-known "star" of the film, arrived and production moved to Lawrence Memorial Hospital. | |||

| Josh Baran and Mark Graham were ] who were secretly given a bootleg copy of the film by Nick Meyer prior to the ABC broadcast. They sent copies of the film to various peace groups, interviewed peace leaders about the film, and held screenings in homes, bars, and restaurants. There were post-screening discussion groups and town hall meetings. They held private screenings for the media, like '']'' magazine, the '']'', and the BBC. As word got out about the film, higher ups wanted to see it including members of the ], and even the Pope. Baran and Graham called it ''The Day Before'' project to hijack ABC's marketing of the film. One scholar said they "pioneered the piggybacking of a public issue onto the release of a commercial media product", and ''Variety'' called it "the greatest PR campaign in history."<ref name="Craig" /> | |||

| The consequences of Meyer's bootleg copy and subsequent ''The Day Before'' PR campaign was a groundswell of public interest and discussion before the film was ever broadcast. This made it difficult for ABC executives to kill the film, because there were rumors they wanted to quietly shelve it, including rumors that Ronald Reagan had hinted to studio executives he didn't want the film broadcast.<ref name="Craig">{{cite book |chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/apocalypsetelevi0000crai/page/85/mode/2up?admin=1&view=theater |chapter=Chapter: Hijacked |title=Apocalypse Television: How The Day After Helped End the Cold War |publisher=Applause |location=Essex, Connecticut |first=David Randolph |last=Craig |year=2024 |pages=85–98 |isbn=9781493079179 }}</ref> | |||

| Many local individuals and businesses profited. It was estimated in newspaper accounts that ABC spent $1 million in Lawrence, not all on the production. | |||

| === Broadcast === | |||

| On September 6, in downtown Lawrence, the filmmakers repainted signs, changing the names of stores, staining the facades with soot. The large windows were shattered into sharp teeth, bricks were scattered and junked cars were painted with clouds of black spray. Two industrial-sized yellow fans bolted to a flatbed trailer blew clouds of white flakes into the air. This fallout-matter was actually ] painted white. | |||

| ''The Day After'' was initially scheduled to premiere on ABC in May 1983, but the post-production work to reduce the film's length pushed back its initial airdate to November. Censors forced ABC to cut an entire scene of a child having a nightmare about ] and then sitting up screaming. A psychiatrist told ABC that it would disturb children. "This strikes me as ludicrous," Meyer wrote in '']'' at the time, "not only in relation to the rest of the film, but also when contrasted with the huge doses of violence to be found on any average evening of TV viewing." In any case, a few more cuts were made, including to a scene in which Denise possesses a ]. Another scene in which a hospital patient abruptly sits up screaming was excised from the original television broadcast but restored for ] releases. Meyer persuaded ABC to dedicate the film to the citizens of Lawrence and also to put a disclaimer at the end of the film after the credits to let the viewer know that ''The Day After'' downplayed the true effects of nuclear war so it could have a story. The disclaimer also included a list of books that provided more information on the subject. | |||

| ''The Day After'' received a large promotional campaign prior to its broadcast. Commercials aired several months in advance, and ABC distributed half-a-million "viewer's guides" that discussed the dangers of nuclear war and prepared the viewer for the graphic scenes of mushroom clouds and radiation burn victims. Discussion groups were also formed nationwide.<ref>{{Cite news|title=Atomic War Film Spurs Nationwide Discussion|last=McFadden|first=Robert D.|date=November 22, 1983|work=The New York Times}}</ref> | |||

| On September 7, students poured into ], the basketball arena, the only place on campus big enough to accommodate so many wounded. A scene was filmed with thousands of radiation victims stretched out on the court floor. | |||

| === Music === | |||

| On September 8, a four-mile stretch on ] between the Edgerton Road exit and the ] interchange at former ] (now Lexington Avenue) was closed for shooting highway scenes representing a mass exodus on ]. On September 10, Robards' character was filmed returning to what is left of Kansas City to find his home. | |||

| The composer ] wrote original music and adapted music from '']'', a documentary film score by the concert composer ], by featuring an adaptation of the hymn "]". Although he recorded just under 30 minutes of music, much of it was edited out of the final cut. Music from the ] footage, conversely, was not edited out. | |||

| === Deleted and alternative scenes === | |||

| ABC used the demolition site of the former St. Joseph Hospital located at Linwood Boulevard and Prospect Avenue in an ] neighborhood in Kansas City as the set. The network paid the city to halt demolition for a month so it could film scenes of destruction there. However, when the crew arrived, more demolition had apparently taken place. Meyer was angry, but then realized he could populate the area with fake corpses and junked cars "and then I got real happy." Robards was in makeup at 6 a.m. to look like a radiation poisoning victim. The makeup took three hours to apply. Passers-by strained for a closer look as Robards lifted the arm of a body stuck under fallen debris--just the arm, severed at the shoulder. It was at this site that the moving final scene where Dr. Oakes confronts a family of squatters was filmed. | |||

| {{more citations needed section|date=October 2011}} | |||

| The film was shortened from the original three hours of running time to two, which caused the scrapping of several planned special-effects scenes although storyboards were made in anticipation of a possible "expanded" version. They included a "bird's eye" view of Kansas City at the moment of two nuclear detonations as seen from a ] airliner approaching the city's airport, simulated newsreel footage of U.S. troops in ] taking up positions in preparation of advancing Soviet armored units, and the tactical nuclear exchange in Germany between NATO and the Warsaw Pact after the attacking Warsaw Pact force breaks through and overwhelms the NATO lines. | |||

| ABC censors severely toned down scenes to reduce the body count or severe burn victims. Meyer refused to remove key scenes, but reportedly, some eight and a half minutes of excised footage still exist, significantly more graphic.{{cn|date=October 2024}} Some footage was reinstated for the film's release on home video. Additionally, the nuclear attack scene was longer and supposed to feature very graphic and very accurate shots of what happens to a human body during a nuclear blast. Examples included people being set on fire; their flesh ]; being burned to the bone; eyes melting; faceless heads; skin hanging; deaths from flying glass and debris, limbs torn off, being crushed, and blown from buildings by the ]; and people in ] suffocating during the ]. Also cut were images of radiation sickness, as well as graphic post-attack violence from survivors such as food riots, looting, and general lawlessness as authorities attempted to restore order. | |||

| ] in downtown Kansas City, Missouri was an important but hard-to-reach location in ''The Day After''.]] | |||

| There were more problems on September 11. Meyer had desperately wanted the ], a tall war memorial in ] overlooking downtown Kansas City, for two scenes: postcard-perfect shots of Kansas City near the beginning and a scene of Robards stumbling through the ruins. However, one director of the local parks department was opposed to letting it be used for commercial purposes and expressed concern that ABC would damage the Memorial. A resolution was reached. By using fiberglass, the filmmakers made it look as if the Memorial had been reduced to rubble. Robards stumbled through debris once again. That evening, the cast and crew flew to Los Angeles. | |||

| One cut scene showed surviving students battling over food. The two sides were to be athletes and the science students under the guidance of Professor Huxley. Another brief scene that was later cut related to a firing squad in which two U.S. soldiers are blindfolded and executed. In that scene, an officer reads the charges, verdict, and sentence as a bandaged chaplain reads the ].{{Citation needed|date=November 2020}} A similar sequence occurs in a 1965 British-produced faux documentary, '']''. In the initial 1983 broadcast of ''The Day After'', when the U.S. president addresses the nation, the voice was an imitation of President Reagan, who later stated that he watched the film and was deeply moved.<ref>Archived at {{cbignore}} and the {{cbignore}}: {{cite web| url = https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7QdZqBKwTMs| title = The Day After: "Reagan-esque" Presidential Address | website=]| date = July 11, 2010 }}{{cbignore}}</ref> In subsequent broadcasts, that voice was overdubbed by a stock actor. | |||

| Interior hospital scenes with Robards and JoBeth Williams were shot in Los Angeles. Many scientific advisors from various fields were on set to ensure the accuracy of the explosion, its effects and its victims. The government, nervous of how it would be portrayed, insisted that the Soviets be the instigators of the attack, and disagreeing with the producers who wanted it to be confused and unclear about who was responsible for launching first, did not allow the production to use ] of nuclear explosions in the film, so ABC hired special effects creators. The result was a visually authentic explosion and iconic "mushroom cloud" created by injecting oil-based paints and inks downward into a water tank with a piston, filmed at high speed with the camera mounted upside down. The image was then optically color- and contrast-inverted. The water tank used for the "mushroom clouds" was the same water tank used to create the "Mutara Nebula" special effect in '']''. | |||

| Home video releases in the U.S. and internationally come in at various running times, many listed at 126 or 127 minutes. ] (4:3 aspect ratio) seems to be more common than widescreen. ] ]s of the early 1980s were limited to 2 hours per disc so that full screen release appears to be closest to what originally aired on ABC in the U.S. A 2001 U.S. VHS version (], ]) lists a running time of 122 minutes. A 1995 double laser disc "director's cut" version (Image Entertainment) runs 127 minutes, includes commentary by director Nicholas Meyer and is "presented in its 1.75:1 European theatrical aspect ratio" (according to the LD jacket). | |||

| ''The Day After'' relied heavily on footage from other movies and from ] government films. Extensive use of stock footage was interspersed with special effects of the mushroom clouds. While the majority of the missile launches came from ] footage of ] missile tests (mainly ]s from ] adjacent to ]), all of the stock footage of missile launches were acquired from declassified DoD film libraries. The scenes of Air Force personnel aboard the Airborne Command Post receiving news of the incoming attack are footage of actual military personnel during a drill and had been aired several years earlier in a 1979 ] documentary, '']''. In the original footage, the silo is "destroyed" by an incoming "attack" just moments before launching its missiles, which is why the final seconds of the launch countdown are not seen in this movie. | |||

| Two different German DVD releases run at 122 and 115 minutes respectively; the edits reportedly downplay the Soviet Union's role.<ref></ref> A two disc Blu-ray special edition was released in 2018 by the video specialty label ] and present the film in high definition. The release contains the 122-minute television cut, presented in a 4:3 aspect ratio as broadcast, as well as the 127-minute theatrical cut, presented in a ].<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.kinolorber.com/product/the-day-after-2-disc-special-edition-blu-ray|title=The Day After (2-Disc Special Edition)|access-date=January 25, 2021|archive-date=January 27, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210127142842/https://www.kinolorber.com/product/the-day-after-2-disc-special-edition-blu-ray|url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| Further stock footage was taken from news events (fires and explosions) and the 1979 theatrical film '']'' (such as a bridge collapsing and the destruction of a tall office building originally used to depict the destruction of the ] in that film). Brief scenes of stampeding crowds were also borrowed from the disaster film '']'' (1976). Other footage had been previously used in theatrical films such as '']'' and '']''. | |||

| == Reception == | |||

| The editing of ''The Day After'' was one of the most nerve-wracking processes ABC had ever gone through in post-production of any of their films. There were many meetings with the censors and Nicholas Meyer was enraged and confused because the network cut out many scenes that it felt slowed the pacing of the film, and not because they were too controversial or too graphic. | |||

| On its original broadcast, on Sunday, November 20, 1983, ] warned viewers before the film was premiered that the film contains graphic and disturbing scenes and encouraged parents who had young children watching to watch together and discuss the issues of nuclear warfare.<ref></ref> ABC and local TV affiliates opened ] with counselors standing by. There were no commercial breaks after the nuclear attack scenes. ABC then aired a live debate on ''Viewpoint'', ABC's occasional discussion program hosted by '']''{{'}}s ], featuring the scientist ], former Secretary of State ], ], former Secretary of Defense ], General ], and the commentator ] Sagan argued against ], but Buckley promoted the concept of ]. Sagan described the ] in the following terms: "Imagine a room awash in gasoline, and there are two implacable enemies in that room. One of them has nine thousand matches, the other seven thousand matches. Each of them is concerned about who's ahead, who's stronger."<ref name="Allyn2012">{{cite book|last=Allyn|first=Bruce|title=The Edge of Armageddon: Lessons from the Brink|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=hAafpVIQVQQC&pg=PT10|date=19 September 2012|publisher=RosettaBooks|isbn=978-0-7953-3073-5|page=10}}{{Dead link|date=August 2024 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref> | |||

| The film and its subject matter were prominently featured in the news media both before and after the broadcast, including on such covers as '']'',<ref></ref> ''Newsweek'',<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.backissues.com/issue/Newsweek-November-21-1983 |title=Backissues.com |access-date=June 28, 2020 |archive-date=June 29, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200629191148/https://www.backissues.com/issue/Newsweek-November-21-1983 |url-status=dead }}</ref> ''],''<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.backissues.com/issue/US-News-and-World-Report-November-28-1983 |title=Backissues.com |access-date=June 28, 2020 |archive-date=June 28, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200628102710/https://www.backissues.com/issue/US-News-and-World-Report-November-28-1983 |url-status=dead }}</ref> and ''].''<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.backissues.com/issue/TV-Guide-November-19-1983 |title=Backissues.com |access-date=June 28, 2020 |archive-date=June 29, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200629232224/https://www.backissues.com/issue/TV-Guide-November-19-1983 |url-status=dead }}</ref> Critics tended to claim the film was sensationalizing nuclear war or that it was too tame.<ref name="MofTV-DayAfter">{{cite web|url=https://museum.tv/archives/etv/D/htmlD/dayafterth/dayafter.htm|title=The Day After|publisher=The Museum of Broadcast Communications|last=Emmanuel|first=Susan|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130116131652/http://www.museum.tv/archives/etv/D/htmlD/dayafterth/dayafter.htm|archive-date=January 16, 2013|df=mdy-all}}</ref> The special effects and realistic portrayal of nuclear war received praise. The film received 12 ] nominations and won two Emmy awards. It was rated "way above average" in '']'' until all reviews for films exclusive to television were removed from the publication.<ref>{{cite book|title=Leonard Maltin's TV Movies And Video Guide 1987 edition|publisher=Signet|last=Maltin|first=Leonard|page=218}}</ref> | |||

| ===Broadcast=== | |||

| The network originally planned to air the film as a four-hour "event" spread over two nights for a total running time of 180 minutes without commercials. Meyer felt the script was padded, and suggested cutting out an hour of material and presenting the whole film in one night. The network disagreed, and Meyer had filmed the entire script. Subsequently, the network found that it was difficult to find advertisers, considering the subject matter, and told Meyer he could edit the film for a one-night version. Meyer's original cut ran two hours and twenty minutes, which he presented to the network. After the screening, the executives were sobbing and seemed deeply affected, leading Meyer to believe they approved of his cut. However, a long six-month struggle began over the final shape of the film. The network now wanted to trim the film to the bone, but Meyer and his editor Bill Dornisch refused to cooperate. Dornisch was fired, and Meyer walked off. The network brought in other editors, but the network ultimately was not happy with their versions. They finally brought Meyer back in and reached a compromise, with a final running time of 120 minutes.<ref name="fallout">{{cite web|last=Niccum|first=John|title=Fallout from ''The Day After''|url=http://www.lawrence.com/news/2003/nov/19/fallout_from/|work=lawrence.com|accessdate=October 11, 2011}}</ref><ref>Meyer, Nicholas, "The View From the Bridge: Memories of Star Trek and a Life in Hollywood", page 150. Viking Adult, 2009</ref> | |||

| In the United States, 38.5 million households, or an estimated 100 million people, watched ''The Day After'' on its first broadcast, a record audience for a made-for-TV movie.<ref>{{Cite news|last=Stuever|first=Hank|date=12 May 2016|title=Yes, 'The Day After' really was the profound TV moment 'The Americans' makes it out to be|newspaper=] – Blogs|url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/arts-and-entertainment/wp/2016/05/11/yes-the-day-after-really-was-the-profound-tv-moment-the-americans-makes-it-out-to-be/|access-date=21 May 2019}}</ref> ] released the film theatrically around the world, in the ], ], ] and ] (this international version contained six minutes of footage not in the telecast edition). Since commercials are not sold in those markets, Producers Sales Organization failed to gain revenue to the tune of an undisclosed sum.{{citation needed|date=September 2019}} Years later, the international version was released to tape by ]. | |||

| ''The Day After'' was initially scheduled to premiere on ABC in May 1983, but the post-production work to reduce the film's length pushed back its initial airdate to November. Censors forced ABC to cut an entire scene of a child having a nightmare about nuclear holocaust and then sitting up, screaming. A psychiatrist told ABC that this would disturb children. "This strikes me as ludicrous," Meyer wrote in '']'' at the time, "not only in relation to the rest of the film, but also when contrasted with the huge doses of violence to be found on any average evening of TV viewing." In any case, they made a few more cuts, including to a scene where Denise possesses a ]. Another scene, where a hospital patient abruptly sits up screaming, was excised from the original television broadcast but restored for home video releases. Meyer persuaded ABC to dedicate the film to the citizens of Lawrence, and also to put a disclaimer at the end of the film, following the credits, letting the viewer know that ''The Day After'' downplayed the true effects of nuclear war so they would be able to have a story. The disclaimer also included a list of books that provide more information on the subject. | |||

| The actor and former Nixon adviser ], critical of the movie's message that the strategy of ] would lead to a war, wrote in the Los Angeles '']'' what life might be like in an America under Soviet occupation. Stein's idea was eventually dramatized in the miniseries '']'', also broadcast by ABC.<ref>The New York Times: By ]. Published February 15, 1987</ref> The '']'' accused Meyer of being a traitor, writing, "Why is Nicholas Meyer doing ]'s work for him?"<ref name="Empire">'']'', "How Ronald Reagan Learned To Start Worrying And Stop Loving The Bomb", November 2010, pp 134–140</ref> ] declared that "This film was made by people who want to disarm the country, and who are willing to make a $7 million contribution to that cause".<ref name="Empire" /> ] in the '']'' accused ''The Day After'' of promoting "unpatriotic" and pro-Soviet attitudes.<ref>Grenier, Richard. "The Brandon Stoddard Horror Show." National Review (1983): 1552–1554.</ref> Much press comment focused on the unanswered question in the film of who started the war.<ref name="Empire" /> The television critic ], in his 2016 book co-written with ], '']'', named ''The Day After'' as the fourth-greatest American TV movie of all time: "Very possibly the bleakest TV-movie ever broadcast, ''The Day After'' is an explicitly antiwar statement dedicated entirely to showing audiences what would happen if nuclear weapons were used on civilian populations in the United States."<ref>{{cite book|author1=Sepinwall, Alan|author2=Seitz, Matt Zoller|author-link1=Alan Sepinwall|author-link2=Matt Zoller Seitz|title=TV (The Book): Two Experts Pick the Greatest American Shows of All Time|date=September 2016|publisher=]|location=New York, NY|isbn=9781455588190|page=372|edition=1st}}</ref> | |||

| ''The Day After'' received a large promotional campaign prior to its broadcast. Commercials aired several months in advance, ABC distributed half a million "viewer's guides" that discussed the dangers of nuclear war and prepared the viewer for the graphic scenes of mushroom clouds and radiation burn victims. Discussion groups were also formed nationwide.{{citation needed|date=July 2014}} | |||

| === Effects on policymakers === | |||

| ===Music=== | |||

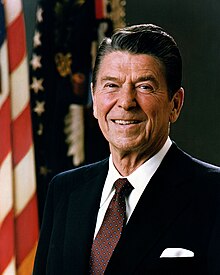

| ] wrote that the film had been very effective and left him depressed.]] | |||

| Composer ] wrote original music and adapted music from '']'' (a documentary film score by concert composer ]), featuring an adaptation of the hymn "]". Although he recorded just under 30 minutes of music, much of it was edited out of the final cut. Music from the ''First Strike'' footage, conversely, was not edited out. | |||

| US President ] watched the film more than a month before its screening on ], October 10, 1983.<ref name="Bulletin">{{Cite web|url=https://thebulletin.org/facing-nuclear-reality-35-years-after-the-day-after/|title=Facing nuclear reality, 35 years after The Day After|last=Stover|first=Dawn|website=Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists|date=December 13, 2018 |language=en-US|access-date=2019-09-10}}</ref> He wrote in his diary that the film was "very effective and left me greatly depressed"<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.reaganfoundation.org/ronald-reagan/white-house-diaries/diary-entry-10101983/|title=Diary Entry - 10/10/1983 {{!}} The Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation & Institute|website=www.reaganfoundation.org|access-date=2019-09-10}}</ref><ref name=Empire/> and that it changed his mind on the prevailing policy on a "nuclear war".<ref>Reagan, '']'', 585</ref> The film was also screened for the ]. A government advisor who attended the screening, a friend of Meyer, told him: "If you wanted to draw blood, you did it. Those guys sat there like they were turned to stone."<ref name="Empire" /> In 1987, Reagan and ] ] signed the ], which resulted in the banning and reducing of their nuclear arsenal. In Reagan's memoirs, he drew a direct line from the film to the signing.<ref name=Empire/> Reagan supposedly later sent Meyer a ] after the summit: "Don't think your movie didn't have any part of this, because it did."<ref name="fallout"/> During an interview in 2010, Meyer said that the telegram was a myth and that the sentiment stemmed from a friend's letter to Meyer. He suggested the story had origins in editing notes received from the ] during the production, which "may have been a joke, but it wouldn't surprise me, him being an old Hollywood guy."<ref name=Empire/> There is also an ] story which claims that, after seeing the film, Ronald Reagan said: "That will not happen on my watch."{{citation needed|date=September 2024}} | |||

| The film also had impact outside the United States. In 1987, during the era of Gorbachev's '']'' and '']'' reforms, the film was shown on ]. Four years earlier, Georgia Representative ] and 91 co-sponsors introduced a resolution in the ] " the sense of the ] that the ], the ], and the ] should work to have the television movie ''The Day After'' aired to the Soviet public."<ref name=Thomas>"thomas.loc.gov, 98th Congress (1983–1984), H.CON.RES.229"</ref> | |||

| ===Deleted and alternative scenes=== | |||

| {{refimprove section|date=October 2011}} | |||

| Due to the film's being shortened from the original three hours (running time) to two, several planned special-effects scenes were scrapped, although storyboards were made in anticipation of a possible "expanded" version. They included a "bird's eye" view of Kansas City at the moment of two nuclear detonations as seen from a Boeing 737 airliner on approach to the city's airport, as well as simulated newsreel footage of U.S. troops in West Germany taking up positions in preparation of advancing Soviet armored units, and the tactical nuclear exchange in Germany between NATO and the Warsaw Pact, which follows after the attacking Warsaw Pact force breaks through and overwhelms the NATO lines. | |||

| == Accolades == | |||

| ABC censors severely toned down scenes to reduce the body count or severe burn victims. Meyer refused to remove key scenes but reportedly some eight and a half minutes of excised footage still exist, significantly more graphic. Some footage was reinstated for the film's release on home video. Additionally, the nuclear attack scene was longer and supposed to feature very graphic and very accurate shots of what happens to a human body during a nuclear blast. Examples included people being set on fire, their flesh carbonizing, being burned to the bone, eyes melting, faceless heads, skin hanging, deaths from flying glass and debris, limbs torn off, being crushed, blown from buildings by the shockwave, and people in fallout shelters suffocating during the firestorm. Also cut were images of radiation sickness, as well as graphic post-attack violence from survivors such as food riots, looting, and general lawlessness as authorities attempted to restore order. | |||

| ''The Day After'' won two ]s and received 10 other Emmy nominations.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.emmys.com/shows/day-after-abc-theatre-presentation|title=The Day After An ABC Theatre Presentation|website=Television Academy|language=en|access-date=2019-01-13}}</ref> | |||

| Emmy Awards won: | |||

| One cut scene shows surviving students battling over food. The two sides were to be athletes versus the science students under the guidance of Professor Huxley. Another brief scene later cut related to a firing squad, where two U.S. soldiers are blindfolded and executed. An officer reads the charges, verdict and sentence, as a bandaged chaplain reads the ]. A similar sequence occurs in a 1965 UK-produced faux documentary, '']''. In the original broadcast of ''The Day After'', when the U.S. president addresses the nation, the voice was an imitation of ].<ref>https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7QdZqBKwTMs</ref> In subsequent broadcasts, that voice was overdubbed by a stock actor. | |||

| * Outstanding Film Sound Editing for a Limited Series or a Special (Christopher T. Welch, Brian Courcier, Greg Dillon, David R. Elliott, Michael Hilkene, Fred Judkins, Carl Mahakian, Joseph A. Mayer, Joe Melody, Catherine Shorr, Richard Shorr, Jill Taggart, Roy Prendergast) | |||

| * ] (], Nancy Rushlow, Dan Pinkham, Chris Regan, Larry Stevens, Christofer Dierdorff, Daniel Nosenchuck) | |||

| Home video releases in the U.S. and internationally come in at various running times, many listed at 126 or 127 minutes; full screen (4:3 aspect ratio) seems to be more common than widescreen. RCA videodiscs of the early 1980s were limited to 2 hours per disc, so that full screen release appears to be closest to what originally aired on ABC in the US. A 2001 U.S. VHS version (Anchor Bay Entertainment, Troy, Michigan) lists a running time of 122 minutes. A 1995 double laser disc "director's cut" version (Image Entertainment) runs 127 minutes, includes commentary by director Nicholas Meyer and is "presented in its 1.75:1 European theatrical aspect ratio" (according to the LD jacket). | |||

| Two different German DVD releases run 122 and 115 minutes; edits reportedly downplay the Soviet Union's role.<ref></ref> | |||

| ==Reception== | |||

| On its original broadcast (Sunday, November 20, 1983), ] warned viewers before the film was premiered that the film contains graphic and disturbing scenes, and encourages parents who have young children watching, to watch together and discuss the issues of nuclear warfare.<ref></ref> ABC and local TV affiliates opened ] with counselors standing by. There were no commercial breaks after the nuclear attack. ABC then aired a live debate on Viewpoint, hosted by '']''{{'}}s ], featuring scientist ], former Secretary of State ], ], former Secretary of Defense ], General ] and conservative commentator ]. Sagan argued against ], while Buckley promoted the concept of ]. Sagan described the ] in the following terms: "Imagine a room awash in gasoline, and there are two implacable enemies in that room. One of them has nine thousand matches, the other seven thousand matches. Each of them is concerned about who's ahead, who's stronger."<ref name="Allyn2012">{{cite book|author=Bruce Allyn|title=The Edge of Armageddon: Lessons from the Brink|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=hAafpVIQVQQC&pg=PT10|date=19 September 2012|publisher=RosettaBooks|isbn=978-0-7953-3073-5|page=10}}</ref> | |||

| One psychotherapist counseled viewers at ] in the Kansas City suburbs, and 1,000 others held candles at a peace vigil in ]. A discussion group called ''Let Lawrence Live'' was formed by the English Department at the university and dozens from the Humanities Department gathered on the campus in front of the Memorial Campanile and lit candles in a peace vigil. At ], a private school in ], roughly 10 miles south of Lawrence, a number of students drove around the city, looking at sites depicted in the film as having been destroyed.{{citation needed|date=July 2014}} | |||

| Children's entertainer ] had filmed five episodes of ] (entitled the "Conflict" series) in the summer of 1983, in reaction to events in Grenada, and the terrorist suicide bombing of a ] barracks in Lebanon. These aired on November 7–11, 1983, one week before the broadcast of ''The Day After.''<ref>"War Enters World of Mister Rogers", C11, Calgary Herald, November 8, 1983</ref> | |||

| A week before the film's airing, conservative group ] issued a "Call for Action" to its "local chairmen", including background material on the Reagan administration's position on strategic defense, along with instructions on how to hold a press conference and a sample guest editorial. In his November 15, 1983 cover letter, Lew Lehrman (]) wrote, "Our response to this piece of nuclear freeze propaganda must be swift and convincing. President Reagan has presented this country with the only option to nuclear disaster: the construction of a strategic defense system that can protect the free world from aggression without the use of the threat of annihilation as a deterrent." | |||

| The film and its subject matter were prominently featured in the news media both before and after the broadcast. On such covers as'' TIME'' magazine,<ref></ref> Newsweek,<ref></ref> and ''U.S. News & World Report,''<ref></ref> and ''TV Guide.''<ref></ref> | |||

| Critics tended to claim the film was either sensationalizing nuclear war or that it was too tame.<ref name="MofTV-DayAfter">{{cite web|url=http://www.museum.tv/archives/etv/D/htmlD/dayafterth/dayafter.htm|title=The Day After|publisher=The Museum of Broadcast Communications|accessdate=|author=Susan Emmanuel|deadurl=yes|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20130116131652/http://www.museum.tv/archives/etv/D/htmlD/dayafterth/dayafter.htm|archivedate=January 16, 2013|df=mdy-all}}</ref> The special effects and realistic portrayal of nuclear war received praise. The film received 12 ] nominations and won two Emmy awards. It was rated "way above average" in '']'', until all reviews for movies exclusive to TV were removed from the guide.<ref>{{cite book|title=Leonard Maltin's TV Movies And Video Guide 1987 edition|publisher=Signet|author=Leonard Maltin|page=218}}</ref> | |||

| In the United States, nearly 100 million people watched ''The Day After'' on its first broadcast, a record audience for a made-for-TV movie. ] released the film theatrically around the world, in the ], China, North Korea and Cuba (this international version contained six minutes of footage not in the telecast edition). Since commercials are not sold in these markets, Producers Sales Organization failed to gain revenue to the tune of an undisclosed sum. Years later this international version was released to tape by Embassy Home Entertainment. | |||

| Commentator ], critical of the movie's message (i.e. that the strategy of ] would lead to a war), wrote in the Los Angeles '']'' what life might be like in an America under Soviet occupation. Stein's idea was eventually dramatized in the miniseries '']'', also broadcast by ABC.<ref>The New York Times: By ]. Published February 15, 1987</ref> | |||

| The '']'' accused Meyer of being a traitor, writing, "Why is Nicholas Meyer doing ]'s work for him?" Much press comment focused on the unanswered question in the film of who started the war.<ref name=Empire>'']'', "How Ronald Reagan Learned To Start Worrying And Stop Loving The Bomb", November 2010, pp 134–140</ref> ] in the '']'' accused ''The Day After'' | |||

| of promoting "unpatriotic" and pro-Soviet attitudes.<ref>Grenier, Richard. "The Brandon Stoddard Horror Show." National Review (1983): 1552–1554.</ref> | |||

| Television critic ] in his 2016 book co-written with ] titled '']'' named ''The Day After'' as the 4th greatest American TV-movie of all time, writing: "Very possibly the bleakest TV-movie ever broadcast, ''The Day After'' is an explicitly antiwar statement dedicated entirely to showing audiences what would happened if nuclear weapons were used on civilian populations in the United States."<ref>{{cite book|author1=Sepinwall, Alan|author2=Seitz, Matt Zoller|authorlink1=Alan Sepinwall|authorlink2=Matt Zoller Seitz|title=TV (The Book): Two Experts Pick the Greatest American Shows of All Time|date=September 2016|publisher=]|location=New York, NY|isbn=9781455588190|page=372|edition=1st}}</ref> | |||

| ===Effects on policymakers=== | |||

| ] wrote that the film was very effective and left him depressed.]] | |||

| President ] watched the film several days before its screening, on November 5, 1983. He wrote in his diary that the film was "very effective and left me greatly depressed,"<ref name=Empire/> and that it changed his mind on the prevailing policy on a "nuclear war".<ref>Reagan, '']'', 585</ref> The film was also screened for the ]. A government advisor who attended the screening, a friend of Meyer's, told him "If you wanted to draw blood, you did it. Those guys sat there like they were turned to stone." Four years later, the ] was signed and in Reagan's memoirs he drew a direct line from the film to the signing.<ref name=Empire/> Reagan supposedly later sent Meyer a telegram after the summit, saying, "Don't think your movie didn't have any part of this, because it did."<ref name="fallout"/> However, in a 2010 interview, Meyer said that this telegram was a myth, and that the sentiment stemmed from a friend's letter to Meyer; he suggested the story had origins in editing notes received from the White House during the production, which "...may have been a joke, but it wouldn't surprise me, him being an old Hollywood guy."<ref name=Empire/> | |||

| The film also had impact outside the U.S. In 1987, during the era of ]'s '']'' and '']'' reforms, the film was shown on ]. Four years earlier, Georgia Rep. ] and 91 co-sponsors introduced a resolution in the ] " the sense of the ] that the ], the ], and the ] should work to have the television movie ''The Day After'' aired to the Soviet public."<ref name=Thomas>"thomas.loc.gov, 98th Congress (1983–1984), H.CON.RES.229"</ref> | |||

| ==Accolades== | |||

| {{unreferenced section|date=July 2014}} | |||

| ]s won: | |||