| Revision as of 15:04, 25 March 2014 view source27.2.33.48 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 19:54, 4 January 2025 view source Nikkimaria (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users233,307 edits rv: "Patriot" is the term typically used in source for that side of the conflictTag: Manual revertNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|1775–1783 American war of independence from Great Britain}} | |||

| {{Redirect|Revolutionary War|revolutions in general|Revolution}} | |||

| {{About|military actions |

{{About|military actions primarily|origins and aftermath|American Revolution}} | ||

| {{Pp|expiry=indefinite|small=yes}} | |||

| {{pp-pc1}} | |||

| {{Use |

{{Use American English|date=June 2019}} | ||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=March 2020}} | |||

| {{Infobox military conflict | {{Infobox military conflict | ||

| |conflict=American Revolutionary War | | conflict = American Revolutionary War | ||

| | partof = the ] | |||

| |image=]]] | |||

| | image = {{Multiple image | |||

| |caption='''Clockwise from top left''': ], Death of ] at the ], ], ], Surrender of ] during the ], ] | |||

| | perrow = 1/2/2 | |||

| |date=April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783<br />({{Age in years, months, weeks and days|month1=04|day1=19|year1=1775|month2=09|day2=03|year2=1783}}) | |||

| | total_width = 300 | |||

| |place=Eastern North America, ], ], Central America;<br>French, Dutch, and British colonial possessions in the ], Africa and elsewhere;<br> | |||

| | border=infobox | |||

| European coastal waters, ], ] and Indian Oceans | |||

| | image1= Surrender of Lord Cornwallis.jpg | |||

| |result=American independence | |||

| | image2= Battle of Guilford Courthouse 15 March 1781.jpg | |||

| * ] | |||

| | image3= Battle of Trenton by Charles McBarron.jpg | |||

| * ] recognition of the<br>] | |||

| | image4= BattleofLongisland.jpg | |||

| |casus=]; direct British rule under the ], ] and ] | |||

| | image5= The_Battle_of_Bunker's_Hill_June_17_1775_by_John_Trumbull.jpeg | |||

| |territory=Britain loses area east of Mississippi River and south of Great Lakes & St. Lawrence River to independent United States & to Spain; Spain gains ], ] and ]; Britain cedes ] and ] to France.<br />Dutch Republic cedes ] to Britain. | |||

| | footer_align = left | |||

| |combatant1={{flag|United States|1777}}<br /> {{flagicon|Kingdom of France}} ] <small>(1778–83)</small><br />{{flagicon|Spain|1748}} ] <small>(1779–83)</small><br /> {{flag|Dutch Republic}} <small>(1780–83)</small> <br /> | |||

| | footer = '''Clockwise from top left''': '']'' after the ], ], ] at the ], ], and the ] | |||

| }} | |||

| | image_size = | |||

| | date = April 19, 1775{{snds}}September 3, 1783{{Efn|A cease-fire in North America was proclaimed by Congress<ref>{{cite web | url=http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/proc1783.asp | title=Avalon Project - British-American Diplomcay : Proclamation Declaring the Cesssation of Arms; April 11, 1783 }}</ref> on April 11, 1783, under a cease-fire agreement between Great Britain and France on January 20, 1783. The final peace treaty was signed on September 3, 1783, and ratified on January 14, 1784, in the U.S., with final ratification exchanged in Europe on May 12, 1784. Hostilities in India continued until July 1783.}}<br />({{Age in years, months and days|1775|04|19|1783|09|03}})<br />Ratification effective: May 12, 1784 | |||

| | place = ], ], the ] | |||

| | result = <!--DO NOT ALTER WITHOUT CONSENSUS --> | |||

| American and allied victory | |||

| * Signing of the ] in 1776. | |||

| * ] would not recognize American independence until signing the ]. | |||

| * End of the ]<ref name="4I7tG">], pp. 615–618</ref> | |||

| | territory = Great Britain cedes generally, all mainland territories east of the ], south of the ], and north of ] to the ]. | |||

| * Great Britain cedes ] and ] to ]. | |||

| * Great Britain cedes ], ] and ] to ]. | |||

| <!--PLEASE DO NOT CHANGE WITHOUT CONSENSUS-->| combatant1 = ''']:'''<br>{{flagcountry|Thirteen Colonies}} (1775)<br>{{Flagdeco|Thirteen Colonies}}{{Flagdeco|United States|1776}} ] (1775–1776)<br>{{Unbulleted list | |||

| |{{Flagdeco|United States|1776}}{{Flagdeco|United States|1777}} ] (from 1776){{efn|Including the United Colonies period from 1776 to 1781 and the ] from 1781 to 1783.}} | |||

| {{Collapsible list|bullets=on | |||

| |]|]|]|]|]|]|]|]|]|]|]|]|]}}<br>{{Flagcountry|Kingdom of France}} | |||

| <br>{{flagdeco|Kingdom of Spain|1760}} ]<br>{{Flagcountry|Dutch Republic}} | |||

| }} | |||

| | combatant1a = | |||

| '''Combatants''' | |||

| {{Unbulleted list | |||

| |] Br. Canadien, Cong. rgts.{{Efn|Two independent "COR" Regiments, the Congress's Own Regiments, were recruited among British Canadiens. The ] formed by ] of ];<ref name="h5WNR">]</ref> and the ] formed by ] of ], Quebec.<ref name="kRctn">]</ref>}} | |||

| |] Br. Canadien mil., Fr. led{{Efn|] independently ] under a ] with British Canadien militia recruited from western Quebec (]) at the county seat of ], ], and ].<ref name="kbqqr">]</ref>}}}} | |||

| {{Collapsible list<!-- removed for consistency, until this works correctly when nested: |bullets=on --> | |||

| |titlestyle=background:transparent;text-align:left;font-weight:normal;font-size:100%; | |||

| |framestyle=border:none; padding:0; <!--Hides borders and improves row spacing--> | |||

| |title=]<ref name="bell">], Essay</ref> | |||

| |]|]|]|]|]|]|]|]{{Efn|(until 1779)}}|]|]|]|]<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://allthingsliberty.com/2015/02/indian-patriots-from-eastern-massachusetts-six-perspectives/|title=Indian Patriots from Eastern Massachusetts: Six Perspectives|first=Daniel J.|last=Tortora|date=February 4, 2015|website=Journal of the American Revolution}}</ref>}} | |||

| <!--DO NOT CHANGE WITHOUT CONSENSUS-->| combatant2 = {{Flagcountry|Kingdom of Great Britain}} | |||

| *]<!--Agreed by consensus, do not revert--> | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| | combatant2a = '''Combatants'''<br>{{Unbulleted list | |||

| |{{Collapsible list|bullets=on | |||

| |titlestyle=background:transparent;text-align:left;font-weight:normal;font-size:100%; | |||

| |title={{flagicon|Hesse}}{{Efn|Sixty-five percent of Britain's German auxiliaries employed in North America were from ] (16,000) and ] (2,422), flying this same flag.<ref>], p. 66</ref>}} {{flagicon|Brunswick|pre1814}}{{Efn|Twenty percent of Britain's German auxiliaries employed in North America were from ] (5,723),<ref>], p. 66</ref> flying this flag.<ref>{{cite web |title=Duchy of Brunswick until 1918 (Germany) |url=https://www.crwflags.com/fotw/flags/de-bs814.html |website=www.crwflags.com |publisher=] |access-date=5 February 2024}}</ref>}} ]<ref name="atwood1,23">], pp. 1, 23</ref>{{Efn|The British hired over 30,000 professional soldiers from various German states who served in North America from 1775 to 1782.<ref>], pp. 14–15</ref> Commentators and historians often refer to them as mercenaries or auxiliaries, terms that are sometimes used interchangeably.<ref name="atwood1,23" />}}<!--There was a consensus to use both terms, per neutrality.--> | |||

| |] ]|] ]|] ]<!--black, yellow and red colors not officially used by the military until 1814: see https://www.fotw.info/flags/de-wp_hi.html-->|] ]|] ]|] ] |{{Flagcountry|Electorate of Hanover}} | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Collapsible list|bullets=on | |||

| |titlestyle=background:transparent;text-align:left;font-weight:normal;font-size:100%; | |||

| |title=]<ref name="bell" /> | |||

| |]|] | |||

| |]|]|]{{Efn|(from 1779)}}|]|]|]|]|]}} | |||

| }} | |||

| | commander1 = <!--MAJOR LEADERS ONLY. DO NOT ADD/REMOVE WITHOUT CONSENSUS -->{{Unbulleted list | |||

| |{{Flagdeco|United States|1777}} ] | |||

| |{{Flagdeco|United States|1777}} ]|{{Flagdeco|United States|1777}} ]}} | |||

| ---- | ---- | ||

| {{Unbulleted list|{{Flagdeco|United States|1777}} ]|{{Flagdeco|United States|1777}} ]|{{Flagdeco|United States|1777}} ]|{{Flagdeco|United States|1777}} ]|{{Flagdeco|United States|1777}} ]|{{Flagdeco|United States|1777}} ]{{Turncoat}}{{Efn|Arnold served on the American side from 1775 to 1780; after defecting, he served on the British side from 1780 to 1783.}}|{{flagicon image |George Rogers Clark Flag.svg}} ]| {{Flagdeco|Kingdom of France}} {{Flagdeco|United States|1777}} ]|{{Flagdeco|Kingdom of France}} ]|{{Flagdeco|Spain|1748}} ]|]}} | |||

| Co-belligerents:<br /> | |||

| | commander2 = <!--MAJOR LEADERS ONLY. DO NOT ADD/REMOVE WITHOUT CONSENSUS-->{{Unbulleted list | |||

| {{flagicon image|Flag of Mysore.svg}} ] <small>(1779–84)</small><br /> | |||

| |{{flagdeco|Kingdom of Great Britain}} ]|{{Flagicon|Kingdom of Great Britain}} ]|{{Flagicon|Kingdom of Great Britain}} ]}} | |||

| {{flagicon image|Flag of Vermont Republic.svg}} ] <small>(1777–83)</small><br /> | |||

| ---- | |||

| ]<br /> | |||

| {{Unbulleted list|{{Flagicon|Kingdom of Great Britain}} ]|{{Flagdeco|Kingdom of Great Britain}} ]|{{Flagdeco|Kingdom of Great Britain}} ]|{{Flagdeco|Kingdom of Great Britain}} ]|{{Flagdeco|Kingdom of Great Britain}} ]|{{Flagdeco|Kingdom of Great Britain}} ]|{{Flagdeco|Kingdom of Great Britain}} ]{{Efn|1780–1783}}|{{Flagdeco|Kingdom of Great Britain}} ]|{{Flagdeco|Kingdom of Great Britain}} ]|]}} | |||

| ]<br /> | |||

| | strength1 = {{Unbulleted list | |||

| ]<br /> | |||

| |'''United States:'''{{Bulleted list | |||

| ]<br /> | |||

| |] and ]:{{Bulleted list|40,000 (average)<ref name="duncan371">], p. 371</ref>{{Efn|The total in active duty service for the American Cause during the American Revolutionary War numbered 200,000.<ref name="6bqxv">], pp. 195–196</ref>}}}} | |||

| ] | |||

| |]:{{Bulleted list|53 ] and ]<ref name="Greene" />{{Efn|5,000 sailors (peak),<ref name="Greene">], p. 328</ref> manning privateers, an additional 55,000 total sailors<ref name="usmm">], "Privateers and Mariners"</ref>}}}} | |||

| |combatant2={{flagcountry|Kingdom of Great Britain}} | |||

| |]: 2,131 (peak)<ref>]</ref> | |||

| {{flag|Germany}} | |||

| |''']:'''{{Bulleted list|106 ships (total)<ref>], pp. 315–316</ref>}}}} | |||

| {{flag|Hesse}} | |||

| |'''France:'''{{Bulleted list | |||

| Co-belligerents:<br /> | |||

| |]: 10,800{{Efn|In 1780, General ] landed in Rhode Island with an independent command of about 6000 troops,<ref>]</ref> and in 1781 Admiral ] landed nearly 4000 troops who were detached to Lafayette's Continental Army surrounding British General ] in Virginia at ].<ref>]</ref> An additional 750 French troops participated with the Spanish assault on ].<ref name="beerman181">]</ref>}} | |||

| <!--The Iroquois flag is anachronistic, and should not be used here-->]<br />]<br />]<br />]<br /> | |||

| |]: <small>2 fleets;</small>{{efn|For five months in 1778 from July to November, the French deployed a fleet to assist American operations off of New York, ] and ] commanded by Admiral ], with little result.<ref>]</ref> In September 1781, Admiral ] left the West Indies to defeat the British fleet off Virginia at the ], then offloaded 3,000 troops and siege cannon to support Washington's ].<ref name="miTsf">]</ref>}} <small>escorts</small><ref name="dull110">], p. 110</ref>}} | |||

| ] | |||

| | '''Spain:''' | |||

| |commander1={{flagicon|United States|1777}} ]<br /> {{flagicon|United States|1777}} ] <br /> {{flagicon|United States|1777}} ]<br />{{flagicon|United States|1777}} ]{{KIA}}<br />{{flagicon|United States|1777}} ]<br />{{flagicon|United States|1777}} ]<br />{{flagicon|United States|1777}} ] (Defected)<br /> {{flagicon|United States|1777}} ]<br /> <!-- | |||

| |]: 12,000{{efn|Governor ] deployed 500 Spanish regulars in his New Orleans-based attacks on British-held locations west of the Mississippi River in ].<ref>]</ref> In later engagements, Galvez had 800 regulars from New Orleans to assault ], reinforced by infantry from regiments of Jose de Ezpeleta from Havana. In the assault on Pensacola, the Spanish Army contingents from Havana exceeded 9,000.<ref>]</ref> For the final days of the siege at Pensacola siege, Admiral Jose Solano's fleet landed 1,600 crack infantry veterans from that of ].<ref name="beerman181" />}} | |||

| Lafayette, although he was French, was commissioned into the Continental Army. Edits changing this flag to the French flag will be reverted. | |||

| |]: 1 fleet;{{efn|Admiral Jose Solano's fleet arrived from the Mediterranean Sea to support the Spanish conquest of English Pensacola, West Florida.<ref name="beerman181" />}} escorts | |||

| -->{{flagicon|United States|1777}} ]<br />{{flagicon|Kingdom of France}} ]<br />{{flagicon|Kingdom of France}} ]<br /> {{flagicon|Kingdom of France}} ]<br />{{flagicon|Kingdom of France}} ]<br /> {{flagicon|Spain|1748}} ]<br />{{flagicon|Spain|1748}} ]<br />{{flagicon|Spain|1748}} ]<br />{{flagicon image|Flag of Mysore.svg}} ]<br />{{flagicon image|Flag of Mysore.svg}} ]<br /><small>]</small> | |||

| |'''Native Americans:''' Unknown | |||

| |commander2={{flagicon|Kingdom of Great Britain}} ]<br /> {{flagicon|Kingdom of Great Britain}} ]<br /> {{flagicon|Kingdom of Great Britain}} ]<br /> {{flagicon|Kingdom of Great Britain}} ] <br /> {{flagicon|Kingdom of Great Britain}} ]{{POW}} <br /> {{flagicon|Kingdom of Great Britain}} ]<br />{{flagicon|Kingdom of Great Britain}} ]{{POW}} <br />{{flagicon|Kingdom of Great Britain}} ]<br /> {{flagicon|Kingdom of Great Britain}} ] <br /> {{flagicon|Kingdom of Great Britain}} ] <br /> {{flagicon|Kingdom of Great Britain}} ]<br />{{flagicon|Kingdom of Great Britain}} ]<br /> {{flagicon|Kingdom of Great Britain}} ] <br /> {{flagicon|Kingdom of Great Britain}} ]<br/>]<br /><small>]</small> | |||

| |strength1= | |||

| '''At Height:'''<br> | |||

| 35,000 Continentals<br> | |||

| 44,500 Militia<br> | |||

| 5,000 ] sailors (at height in 1779)<ref name="Greene"/><br>53 ships (active service at some point during the war)<ref name="Greene">Jack P. Greene and J. R. Pole. ''A Companion to the American Revolution'' (Wiley-Blackwell, 2003), p. 328.</ref><br> | |||

| 12,000 French (in America)<br> | |||

| ~60,000 French and Spanish (in Europe)<ref>Montero{{clarify|reason=need full citation|date=November 2010}} p. 356</ref> | |||

| |strength2= | |||

| '''At Height:'''<br> | |||

| 56,000 British{{Citation needed|date=November 2010|reason=need reliable source for this}}<br> | |||

| 78 ] ships in 1775<ref name="Greene"/> | |||

| 171,000 Sailors<ref name="Mackesy 1964 pp. 6, 176">Mackesy (1964), pp. 6, 176 (British seamen)</ref><br> | |||

| 30,000 Germans<ref>A. J. Berry, ''A Time of Terror'' (2006) p. 252</ref><br> | |||

| 50,000 Loyalists<ref>Claude, Van Tyne, ''The Loyalists in the American Revolution'' (1902) pp. 182–3.</ref><br> | |||

| 13,000 Natives<ref>Greene and Pole (1999), p. 393; Boatner (1974), p. 545</ref> | |||

| |casualties1= '''American:''' 25,000 dead | |||

| * 8,000 in battle | |||

| * 17,000 by other causes | |||

| ''Total American casualties:'' up to 50,000 dead and wounded<ref>American dead and wounded: Shy, pp. 249–50. The lower figure for number of wounded comes from Chambers, p. 849.</ref> | |||

| <br> '''Allies:''' 6,000± French and Spanish (in Europe)<br>2,000 French (in America) | |||

| |casualties2= | |||

| 20,000± Soldiers from the British army dead and wounded | |||

| 19,740 sailors dead (1,240 in Battle)<ref name="Mackesy 1964 pp. 6, 176"/><br> | |||

| 42,000 sailors deserted<ref name="Mackesy 1964 pp. 6, 176"/><br> | |||

| 7,554 Germans dead | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| | strength2 = {{Unbulleted list | |||

| {{Campaignbox American Revolutionary War}} | |||

| |'''Great Britain:'''{{Bulleted list | |||

| The '''American Revolutionary War''' (1775–1783), the '''American War of Independence''',{{#tag:ref|British writers generally favor "American War of Independence", "American Rebellion", or "War of American Independence". See Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, ''Bibliography'' at the for usage in titles.|group=N}} or simply the '''Revolutionary War''' in the United States, was the successful rebellion against ] of ] who confederated themselves as the ]. Originally limited to fighting in those colonies, after 1778 it also became a ] between Britain and ], ], ], and ]. American independence was achieved and European powers recognized the independence of the new ], with mixed results for the other nations involved.{{#tag:ref|In this article, inhabitants of the thirteen colonies that supported the American Revolution are primarily referred to as "Americans", with occasional references to "Patriots", "Whigs", "Rebels" or "Revolutionaries". Colonists who supported the British in opposing the Revolution are referred to as "Loyalists" or "Tories". The geographical area of the thirteen colonies is often referred to simply as "America".|group=N}} | |||

| |]:{{Bulleted list | |||

| |48,000 (average), most in North America{{Efn|British 121,000 (global 1781)<ref>], "British Army 1775–1783"</ref> "Of 7,500 men in the Gibraltar garrison in September (including 400 in hospital), some 3,430 were always on duty".<ref>], p. 63</ref>}}}} | |||

| |]:{{Bulleted list | |||

| |Task-force fleets & blockading squadrons{{Efn|Royal Navy 94 ] global, 104 ] global,<ref name="winfield">]</ref> 37 ] global,<ref name="winfield" /> | |||

| 171,000 sailors<ref name="macksey6,176">] , pp. 6, 176</ref>}}}}}} | |||

| |''']:'''{{Bulleted list | |||

| The war had its origins in the resistance of many Americans to what they deemed as unlawful taxes imposed by the British parliament. Formal acts of rebellion against British authority began in late 1774 when the Patriot ] effectively abolished the legal government of the ]. The tensions caused by this directly led to the outbreak of fighting between Patriot militia and British regulars ] in April 1775. By the end of 1775 rebels had seized full control in thirteen British colonies and on July 4, 1776, their ] ]. The British were meanwhile mustering large forces to put down the revolt. They inflicted significant defeats on the American rebel army, now under the command of ], ] and later ]. But they were unable or unwilling to land a finishing blow against him. British strategy relied on mobilizing ], of whom they made little effort to enlist until late in the war.<ref>Paul H. Smith, "The American Loyalists: Notes on Their Organization and Numerical Strength". ''William and Mary Quarterly'' (1968) 25#2 pp. 259–277 </ref> Poor coordination helped doom a ] in 1777, which resulted in the capture of a British army following the ]. | |||

| |25,000 (total)<ref name="savas41">], p. xli</ref>{{Efn|Contains a detailed listing of American, French, British, German, and Loyalist regiments; indicates when they were raised, the main battles, and what happened to them. Also includes the main warships on both sides, and all the important battles.}}}} | |||

| |''']:'''{{Bulleted list |29,875 (total)<ref name="Knesebeck">] , p. 9</ref>}} | |||

| |'''Native Americans:'''{{Bulleted list|13,000<ref name="Greene p. 393" />}}}} | |||

| | casualties1 = {{Unbulleted list | |||

| |'''United States:'''{{Bulleted list | |||

| |178,800–223,800 total dead | |||

| |6,800 killed | |||

| |6,100 wounded | |||

| |17,000 dead from disease<ref name="oLlYw">], "Patriots or Terrorists"</ref> | |||

| |25,000–70,000 war dead<ref name="FFKG4">]</ref> | |||

| |130,000 dead from smallpox<ref name="2D11O">], pp. 133–134</ref>}} | |||

| |'''France:'''{{Bulleted list | |||

| |2,112 killed– <small>East Coast</small><ref name="ApKKb">], pp. 20, 53</ref>{{Efn|1=Beyond the 2112 deaths recorded by the French Government fighting for U.S. independence, additional men died fighting Britain in a war waged by France, Spain, and the Dutch Republic from 1778 to 1784, "overseas" from the American Revolution as posited by a British scholar{{specify|date=July 2022}} in his "War of the American Revolution".<ref name="yt8Dp">], pp. 75, 135</ref>}}}} | |||

| |'''Spain:'''{{Bulleted list | |||

| |371 killed – W. Florida<ref name="gZqKm">], p. 16</ref> | |||

| |4,000 dead – prisoners<ref name="QEJS2">], p. 69</ref>}} | |||

| |'''Native Americans:''' Unknown | |||

| }} | |||

| | casualties2 = {{Unbulleted list | |||

| |'''Great Britain:'''{{Bulleted list | |||

| |8,500 killed<ref name="3kb8Q">], p. 134</ref>{{Efn|Clodfelter reports that the total deaths among the British and their allies numbered 15,000 killed in battle or died of wounds. These included estimates of 3000 Germans, 3000 Loyalists and Canadians, 3000 lost at sea, and 500 Native Americans killed in battle or died of wounds.<ref name="2D11O" />}}}} | |||

| |'''Germans:'''{{Bulleted list | |||

| |7,774 total dead | |||

| |1,800 killed | |||

| |4,888 deserted<ref name="duncan371" />}} | |||

| |''']:'''{{Bulleted list | |||

| |7,000 total dead | |||

| |1,700 killed | |||

| |5,300 dead from disease<ref name="SlCBl">], ''Forgotten Patriots''</ref>}} | |||

| |'''Native Americans'''{{Bulleted list | |||

| |500 total dead<ref name="2D11O" />}} | |||

| }} | |||

| | campaignbox = {{Campaignbox American Revolutionary War}} | |||

| }} | |||

| <!-- | |||

| Please do not make any major edits to the lead, as it was agreed upon by consensus on the talk page. Please discuss if you wish to change it. | |||

| --> | |||

| The '''American Revolutionary War''' (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the '''Revolutionary War''' or '''American War of Independence''', was an armed conflict that was part of the broader ], in which American ] forces organized as the ] and commanded by ] defeated the ]. The conflict was fought in ], the ], and the ]. The war ended with the ], which resulted in ] ultimately recognizing the independence of the ]. | |||

| ], ] and the ] had been secretly providing ] to the revolutionaries starting early in 1776. The American victory at Saratoga persuaded France ] openly in early 1778, forcing Britain to divert troops to other theaters. French involvement proved decisive<ref>Greene and Pole, ''A Companion to the American Revolution'' p 357</ref> yet expensive, ruining France's economy and driving the country into massive debt.<ref>Jonathan R. Dull, ''A Diplomatic History of the American Revolution'' (1987) p. 161</ref> ] and the ]—French allies—also went to war with Britain over the next four years, threatening an ] and severely testing British military strength with campaigns in Europe, Asia, and the Caribbean. | |||

| After the ] gained dominance in North America with victory over the French in the ] in 1763, tensions and disputes arose between Great Britain and the ] over a variety of issues, including the ] and ]. The resulting British military occupation led to the ] in 1770. Among further tensions, the British Parliament imposed the ] in mid-1774. A British attempt to disarm the Americans and the resulting ] in April 1775 ignited the war. In June, the ] formalized Patriot militias into the ] and appointed Washington its commander-in-chief. The British Parliament declared the colonies to be in a ] in August 1775. The stakes of the war were formalized with passage of the ] by the Congress in ] on July 2, 1776, and the unanimous ratification of the ] on July 4, 1776. | |||

| After 1778 the British shifted their attention to the southern colonies, which brought them initial success when they recaptured ] and ] for the Crown in 1779 and 1780. In 1781 British forces attempted to subjugate ], but a French ] just outside ] led to a ] and the capture of over 7,000 British soldiers. The defeat broke Britain's will to continue the war. Limited fighting continued throughout 1782, while peace negotiations began. In 1783, the ] ended the war and recognized the sovereignty of the United States over the territory bounded roughly by what is now Canada to the north, ] to the south, and the ] to the west.<ref>Dull, ''A Diplomatic History of the American Revolution'' ch 18</ref><ref name="historiographical431">Lawrence S. Kaplan, "The Treaty of Paris, 1783: A Historiographical Challenge", ''International History Review,'' Sept 1983, Vol. 5 Issue 3, pp 431–442</ref> A wider international peace was agreed, in which several territories were exchanged. | |||

| After a ], Washington's forces drove the ] out of Boston in March 1776, and British commander in chief ] responded by launching the ]. Howe captured New York City in November. Washington responded by ] the ] and winning small but significant victories at ] and ]. In the summer of 1777, as Howe was poised to ], the Continental Congress fled to ]. In October 1777, a separate northern British force under the command of ] was forced to surrender at ] in an American victory that proved crucial in convincing France and Spain that an independent United States was a viable possibility. France signed a ] with the rebels, followed by a ] in February 1778. In 1779, the ] undertook a ] campaign against the Iroquois who were largely allied with the British. Indian raids on the American frontier, however, continued to be a problem. Also, in 1779, Spain allied with France against Great Britain in the ], though Spain did not formally ally with the Americans. | |||

| ==Causes== | |||

| {{main|American Revolution}} | |||

| Howe's replacement ] intended to take the war against the Americans into the ]. Despite some initial success, British General ] was besieged by a Franco-American force in ] in September and October 1781. Cornwallis was forced to surrender in October. The British wars with France and Spain continued for another two years, but fighting largely ceased in North America. In the Treaty of Paris, ratified on September 3, 1783, Great Britain acknowledged the sovereignty and independence of the United States, bringing the American Revolutionary War to an end. The ] resolved Great Britain's conflicts with ] and ] and forced Great Britain to cede ], ], and small territories in ] to France, and ], ] and ] to Spain.<ref>Lawrence S. Kaplan, "The Treaty of Paris, 1783: A Historiographical Challenge", ''International History Review,'' Sept 1983, Vol. 5 Issue 3, pp 431–442</ref><ref name="9w1sv">], "American Revolution"</ref> | |||

| ===Background=== | |||

| ==Prelude to war== | |||

| The relationship between the ] and their British parent state in the 17th and 18th centuries was not particularly well-defined. The colonies were governed by ]s issued by the ] (later ]), who was usually represented in each colony by an appointed governor. The King was head of state and handled all foreign affairs. Apart from this, there was relatively little interference from Britain (apart from trade regulations like the ]) and locally elected colonial assemblies generally made policy as they saw fit. | |||

| {{Main|American Revolution}} | |||

| {{Further|American Enlightenment|Colonial history of the United States|Thirteen Colonies}} | |||

| ] and ] following the ] with lands held by the British prior to 1763 (in red), land gained by Britain in 1763 (in pink), and lands ceded to the ] in secret during 1762 (in light yellow).]] | |||

| The French and Indian War, part of the wider global conflict known as the ], ended with the ], which expelled ] from their possessions in ].<ref name="wtW8l">], p. 4</ref> The ] was designed to refocus colonial expansion north into ] and south into ], with the ] as the dividing line between British and ] possessions in America. Settlement was tightly restricted beyond the 1763 limits, and claims west of this line, including by ] and ], were rescinded.{{Sfn|Lass|1980|p=3}} With the exception of Virginia and others deprived of rights to western lands, the ] agreed on the boundaries but disagreed on where to set them. Many settlers resented the restrictions entirely, and enforcement required permanent garrisons along the frontier, which led to increasingly bitter disputes over who should pay for them.<ref name="pb2Zp">], p. 12</ref> | |||

| There was already a distinct feeling of separateness. America had been settled largely by people from the ], but overall immigration from Britain to America was relatively modest and Britons and Americans tended to see each other as foreigners. Communications between Britain and America in the 18th century were very slow, usually taking months, contributing to a sense of isolation. Also, many Americans were descended from groups that had been viewed as political radicals in Britain. This was particularly true of the ] of ], colonies they settled (] in particular) were widely seen as the ringleaders of the rebellion. | |||

| ===Taxation and legislation=== | |||

| During the course of the 17th century the power of the British monarchy had been greatly diminished, and the ] consequently strengthened, by the ] and ]. This culminated into the 1689 ] which effectively established the legislative supremacy of parliament by declaring that the monarch could not, among other things, raise taxes without the consent of the legislature. This would become the basis for the American argument that their "Rights as Englishmen" meant that taxes could not be imposed on them without their consent. The issue was framed by the popular American slogan of "]". At the same time the colonists rejected out of hand being provided with said representation in Parliament, claiming that "their local circumstances" made it impossible.<ref> "the people of these colonies are not, and from their local circumstances cannot be, represented in the House of Commons in Great-Britain." quoted from the October 19, 1765</ref><ref>"... as the English colonists are not represented, and from their local and other circumstances, cannot properly be represented in the British parliament, they are entitled to a free and exclusive power of legislation in their several provincial legislatures, where their right of representation can alone be preserved...." quoted from the October 14, 1774 </ref> | |||

| {{Further|Boston Tea Party|Pine Tree Riot}} | |||

| The huge debt incurred by the Seven Years' War and demands from British taxpayers for cuts in government expenditure meant ] expected the colonies to fund their own defense.<ref name="pb2Zp" /> The 1763 to 1765 ] instructed the ] to cease trading smuggled goods and enforce customs duties levied in American ports.<ref name="pb2Zp" /> The most important was the 1733 ]; routinely ignored before 1763, it had a significant economic impact since 85% of New England rum exports were manufactured from imported molasses. These measures were followed by the ] and ], which imposed additional taxes on the colonies to pay for defending the western frontier.<ref name="4R8zt">], pp. 183–184</ref> The taxes proved highly burdensome, particularly for the poorer classes, and quickly became a source of discontent.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Kay |first=Marvin L. Michael |date=April 1969 |title=The Payment of Provincial and Local Taxes in North Carolina, 1748–1771 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/1918676 |journal=] |volume=26 |issue=2 |pages=218–240 |doi=10.2307/1918676 |jstor=1918676 |access-date=1 September 2024}}</ref> In July 1765, the ] formed the ], which repealed the Stamp Act and reduced tax on foreign molasses to help the New England economy, but re-asserted Parliamentary authority in the ].<ref name="Leqka">], pp. 116, 187</ref> | |||

| American Patriots believed that they were only tied to Britain by their common head of state, the ]. They argued that the ] could not pass legislation affecting the internal matters of America in the place of their own local assemblies, which had been created by a contract between themselves and the King. This was supported by various precedents which indicated that America was, in theory, the property of the King and not annexed to the "realm" of Britain. When the Patriots later declared the colonies independent in 1776, they were not declaring independence from the nation of ] (whose authority over them they refused acknowledge in the first place) but only from the ]. The monarchy was held to be perfectly lawful until ] allegedly abused his authority by agreeing to the illegal acts of his British ministers. | |||

| However, this did little to end the discontent; in 1768, a riot started in Boston when the authorities seized the sloop '']'' on suspicion of smuggling.<ref name="sImY5">], p. 40</ref> Tensions escalated in March 1770 when British troops fired on rock-throwing civilians, killing five in what became known as the ].<ref name="kIDxS">], p. 23</ref> The Massacre coincided with the partial repeal of the ] by the Tory-based ]. North insisted on retaining duty on tea to enshrine Parliament's right to tax the colonies; the amount was minor, but ignored the fact it was that very principle Americans found objectionable.<ref name="HdjZT">], p. 52</ref> | |||

| The British, however, viewed this as an utterly preposterous interpretation of colonial relations, a point of view the Americans never advanced until after the ] safely eliminated the danger of a French takeover. They saw the colonial governments as entirely subordinate entities created for convenience due to the vast distance across the Atlantic. They argued that any agreements between colonists and the executive authority (the King) did not and could not exempt them from the highest legislative authority (which in earlier days was also the King but now was the Parliament). Since they had been chartered as corporations by ], they were subject to the legislative regulations of that crown, which were exercised by the Parliament. Evidence supporting this included the 1681 royal charter for ] which expressly indicated Parliament could tax without consent.<ref>"AND FARTHER our pleasure is, and by these presents, for us, our heires and Successors, Wee doe covenant and grant to and with the said William Penn, and his heires and assignee, That Wee, our heires and Successors, shall at no time hereafter sett or make, or cause to be sets, any impossition, custome or other taxation, rate or contribution whatsoever, in and upon the dwellers and inhabitants of the aforesaid Province, for their Lands, tenements, goods or chattells within the said Province, or in and upon any goods or merchandise within the said Province, or to be laden or unladen within the ports or harbours of the said Province, unless the same be with the consent of the Proprietary, or chiefe governor, or assembly, '''or by act of Parliament in England.'''" quoted from the February 28, 1681</ref> The British did not believe that "no taxation without representation" was part of the ]. The Americans were "virtually represented" in Parliament just like the vast majority of British people were in the 18th century, where only a small minority were allowed to elect representatives and the unrepresented still had to pay taxes. Since Parliament had been taxing the trade of the colonists for decades, depriving them of personal property without their consent for the benefit of the whole empire, it was argued that revenues could be raised for the same general purpose. | |||

| In April 1772, colonialists staged the first American tax revolt against British royal authority in ], later referred to as the ].<ref>{{Cite web |title=The Weare NH Historical Society |url=http://wearehistoricalsociety.org/pineriot.php |access-date=2024-07-01 |website=wearehistoricalsociety.org}}</ref> This would inspire the design of the ]. Tensions escalated following the destruction of a customs vessel in the June 1772 ], then came to a head in 1773. A ] led to the near-collapse of the ], which dominated the British economy; to support it, Parliament passed the ], giving it a trading monopoly in the ]. Since most American tea was smuggled by the Dutch, the act was opposed by those who managed the illegal trade, while being seen as another attempt to impose the principle of taxation by Parliament.<ref name="oTpsv">], pp. 155–156</ref> In December 1773, a group called the ] disguised as ]s dumped crates of tea into ], an event later known as the ]. The British Parliament responded by passing the so-called ], aimed specifically at Massachusetts, although many colonists and members of the Whig opposition considered them a threat to liberty in general. This increased sympathy for the ] cause locally, in the British Parliament, and in the London press.<ref name="t3NFX">], p. 15</ref> | |||

| ===Taxes=== | |||

| ===Break with the British Crown=== | |||

| The close of the ] (the ] in North America) saw Britain triumphant in driving the French from North America, but also heavily in debt. Taxes in Britain were already very high and it was thought that the American colonies should contribute their fair share toward defense costs. Parliament passed the ] in 1765, which imposed direct taxes on the colonies for the first time. This met with strong condemnation among local American elites, who declared that Parliament aimed to enslave them. Mob violence prevented the Act from being enforced, and organized boycotts of British goods were instituted. This resistance was by and large unexpected and greatly alarmed the British. A change of government in Britain led to the repeal of the Stamp Act, but also the passage of the ], which stated that Parliamentary laws had supreme power over the colonies. | |||

| {{Further|Battles of Lexington and Concord|First Continental Congress}} | |||

| Throughout the 18th century, the ] in the colonial legislatures gradually wrested power from their governors.<ref name="0pRKw">], pp. 543–544</ref> Dominated by smaller landowners and merchants, these assemblies now established ad-hoc provincial legislatures, effectively replacing royal control. With the exception of ], twelve colonies sent representatives to the ] to agree on a unified response to the crisis.<ref name="0j3B4">], p. 112</ref> Many of the delegates feared that a boycott would result in war and sent a ] calling for the repeal of the Intolerable Acts.<ref name="BkMNP">], p. 102</ref> After some debate, on September 17, 1774, Congress endorsed the Massachusetts ] and on October 20 passed the ], which instituted ] and a boycott of goods against Britain.<ref name="yBXBu">], p. 199</ref> | |||

| In their declarations, Americans had claimed that the ] was unconstitutional because the taxes were of an "internal" nature that only their elected representatives could raise, and were different from the long-standing custom duties that were held to be lawful. So in 1767 Parliament passed the ], which imposed duties on various British goods exported to the colonies. The Americans quickly denounced this as illegal as well, since the intent of the act was to raise revenue and not regulate trade. For their part, the British could not understand why the Americans deemed Parliamentary trade taxes lawful but not revenue taxes. | |||

| While denying its authority over internal American affairs, a faction led by ] and future ] ] insisted Congress recognize Parliament's right to regulate colonial trade.<ref name="yBXBu" />{{Efn|"Resolved, 4. That the foundation of English liberty, and of all free government, is a right in the people to participate in their legislative council: ... they are entitled to a free and exclusive power of legislation in their several provincial legislatures, where their right of representation can alone be preserved, in all cases of taxation and internal polity, subject only to the negative of their sovereign, ...: But, ... we cheerfully consent to the operation of such acts of the British parliament, as are bonafide, restrained to the regulation of our external commerce, for the purpose of securing the commercial advantages of the whole empire to the mother country, and the commercial benefits of its respective members; excluding every idea of taxation internal or external, ." quoted from the Declarations and Resolves of the First Continental Congress October 14, 1774.}} Expecting concessions by the North administration, Congress authorized the colonial legislatures to enforce the boycott; this succeeded in reducing British imports by 97% from 1774 to 1775.<ref name="RVpda">], p. 21</ref> However, on February 9 Parliament declared Massachusetts to be in rebellion and instituted a blockade of the colony.<ref name="X94UC">], pp. 62–64</ref> In July, the ] limited colonial trade with the ] and Britain and barred New England ships from the ]. The tension led to a scramble for control of militia stores, which each assembly was legally obliged to maintain for defense.<ref name="JNwEc">], p. 83</ref> On April 19, a British attempt to secure the Concord arsenal culminated in the ], which began the Revolutionary War.<ref name="Ng1sv">], p. 76</ref> | |||

| ] was entitled "The Destruction of Tea at Boston Harbor"; the phrase "Boston Tea Party" had not yet become standard. Contrary to Currier's depiction, few of the men dumping the tea were actually disguised as Indians.<ref>Young, ''Shoemaker'', 183–85.</ref>]] | |||

| ===Political reactions=== | |||

| Faced with renewed resistance, the British caved once again. In 1770 all the Townshend duties were repealed except for the one on tea, which was retained merely to save face. The British effectively gave up on the idea of raising revenue and the colonists ended their boycotts, with some even buying the taxed tea. This short-lived truce ended in 1773 when, in an effort to rescue the ] from financial difficulties, the British attempted to increase tea sales by lowering prices and appointing certain merchants in America to receive and sell it. The landing of this tea was resisted in all the colonies and, when the royal governor of Massachusetts refused to send back the tea ships in Boston, ]. | |||

| {{Main|Olive Branch Petition}} | |||

| ], who were charged with drafting the ], including (from left to right): ] (chair), ], ], ] (the Declaration's principal author), and ]]] | |||

| After the Patriot victory at Concord, moderates in Congress led by ] drafted the ], offering to accept royal authority in return for George III mediating in the dispute.<ref name="nessy25">], p. 25</ref> However, since the petition was immediately followed by the ], Colonial Secretary ] viewed the offer as insincere and refused to present the petition to the king.<ref name="NXP0A">], pp. 29–31</ref> Although constitutionally correct, since the monarch could not oppose his own government, it disappointed those Americans who hoped he would mediate in the dispute, while the hostility of his language annoyed even Loyalist members of Congress.<ref name="nessy25" /> Combined with the ], issued on August 23 in response to the ], it ended hopes of a peaceful settlement.<ref name="ketchum211">], p. 211</ref> | |||

| ===Crisis=== | |||

| Backed by the Whigs, Parliament initially rejected the imposition of coercive measures by 170 votes, fearing an aggressive policy would drive the Americans towards independence.<ref name="maier25">], p. 25</ref> However, by the end of 1774 the collapse of British authority meant both Lord North and George III were convinced war was inevitable.<ref name="fFVBS">], pp. 123–124</ref> After Boston, Gage halted operations and awaited reinforcements; the ] approved the recruitment of new regiments, while allowing Catholics to enlist for the first time.<ref name="lecky162-165">], vol. 3, pp. 162–165</ref> Britain also signed a series of treaties with German states to supply ].<ref name="davenport132-144">], pp. 132–144</ref> Within a year, it had an army of over 32,000 men in America, the largest ever sent outside Europe at the time.<ref name="smith21-23">], pp. 21–23</ref> The employment of German soldiers against people viewed as British citizens was opposed by many in Parliament and by the colonial assemblies; combined with the lack of activity by Gage, opposition to the use of foreign troops allowed the Patriots to take control of the legislatures.<ref name="miller410">], pp. 410–412</ref> | |||

| Nobody was punished for the "]" and such bold defiance of law and order became too much for Britain. In 1774 Parliament ordered Boston harbor closed until the destroyed tea was paid for. It then passed the ] to punish the rebellious colony. The upper house of the Massachusetts legislature would be appointed by the Crown, as was already the case in other colonies such as ] and ]. The royal governor was able to appoint and remove at will all judges, sheriffs, and other executive officials, and restrict town meetings. Jurors would be selected by the sheriffs and British soldiers would be tried outside the colony for alleged offenses. These were collectively dubbed the "]" by the Patriots. | |||

| ===Declaration of Independence=== | |||

| Although these actions were not unprecedented (the Massachusetts charter had already been replaced once before in 1692), the people of the colony were outraged. Town meetings resulted in the ], a declaration not to cooperate with the royal authorities. In October 1774 an illegal "]" was established which took over the governance of Massachusetts outside of British-occupied Boston and began training militia for hostilities. | |||

| {{Main|United States Declaration of Independence}} | |||

| Support for independence was boosted by ]'s pamphlet '']'', which was published on January 10, 1776, and argued for American self-government and was widely reprinted.<ref name="maier33-34">], pp. 33–34</ref> To draft the ], the ] appointed the ]: ], ], ], ], and ].<ref name="mccullough119">], pp. 119–122</ref> The declaration was written almost exclusively by Jefferson.<ref>, National Park Services</ref> | |||

| Meanwhile, in September 1774 representatives of the other colonies convened the ] in order to respond to the crisis. The Congress rejected a "]" proposed by ] to establish an American parliament that could approve or disapprove of the acts of the British parliament. Instead, they endorsed the ] and demanded the repeal of ''all'' Parliamentary acts passed since 1763, not merely the tax on tea and the "Intolerable Acts". They also required Britain to acknowledge that unilaterally stationing troops in the colonies in a time of peace was "against the law". Although the Congress lacked any legal authority, it ordered the creation of Patriot committees who would enforce a boycott of British goods starting on December 1, 1774. | |||

| Identifying inhabitants of the Thirteen Colonies as "one people", the declaration simultaneously dissolved political links with Britain, while including a long list of alleged violations of "English rights" committed by ]. This is also one of the first times that the colonies were referred to as "United States", rather than the more common ].<ref name="ferling112">], pp. 112, 118</ref> | |||

| With the colonists seizing public military stores and preparing for war, British Prime Minister ] attempted a last-ditch compromise. In February 1775 he proposed not to impose taxes if the colonies themselves made "fixed contributions". This would safeguard the taxing rights of the colonies from future infringement while enabling them to contribute to maintenance of the empire. This proposal was nevertheless rejected by the Congress in July as an "insidious maneuver", by which time hostilities had broken out. | |||

| On July 2, Congress voted for independence and published the declaration on July 4.<ref name="R0xyC">], pp. 160–161</ref> At this point, the revolution ceased to be an internal dispute over trade and tax policies and had evolved into a civil war, since each state represented in Congress was engaged in a struggle with Britain, but also split between American Patriots and American Loyalists.<ref name="IE7Bq">], p. 2</ref> Patriots generally supported independence from Britain and a new national union in Congress, while Loyalists remained faithful to British rule. Estimates of numbers vary, one suggestion being the population as a whole was split evenly between committed Patriots, committed Loyalists, and those who were indifferent.<ref name="DEcPu">], p. 3</ref> Others calculate the split as 40% Patriot, 40% neutral, 20% Loyalist, but with considerable regional variations.<ref name="Greene p. 235">], p. 235</ref> | |||

| ==First phase, 1775–1778== | |||

| At the onset of the war, the Second Continental Congress realized defeating Britain required foreign alliances and intelligence-gathering. The ] was formed for "the sole purpose of corresponding with our friends in Great Britain and other parts of the world". From 1775 to 1776, the committee shared information and built alliances through secret correspondence, as well as employing secret agents in Europe to gather intelligence, conduct undercover operations, analyze foreign publications, and initiate Patriot propaganda campaigns.<ref name="cia2007">], "Intelligence Until WWII"</ref> Paine served as secretary, while Benjamin Franklin and ], sent to France to recruit military engineers,<ref>], pp. 86–87</ref> were instrumental in securing French aid in Paris.<ref name="rose43">] , p. 43</ref> | |||

| ===Outbreak of the War 1775–76=== | |||

| ==War breaks out== | |||

| ====Massachusetts==== | |||

| {{main|Northern theater of the American Revolutionary War|Southern theater of the American Revolutionary War}} | |||

| {{also|Western theater of the American Revolutionary War}} | |||

| {{more|Naval battles of the American Revolutionary War}} | |||

| <!-- and this section is a brief summary of the "Boston campaign" article, so add additional details there rather than here.--> | |||

| {{Main|Boston campaign}} | |||

| ===Early engagements=== | |||

| Before the war, ] had been the center of much revolutionary activity, leading to the punitive ] in 1774 that ended local government. Popular resistance to these measures, however, compelled the newly appointed royal officials in Massachusetts to resign or to seek refuge in Boston. Lieutenant General ], the British ], commanded four regiments of British regulars (about 4,000 men) from his headquarters in Boston, but the countryside was in the hands of the Revolutionaries. | |||

| {{Further|Battles of Lexington and Concord|Shot heard round the world}} | |||

| ] attack at the ] in December 1775]] | |||

| ] in April 1775]] | |||

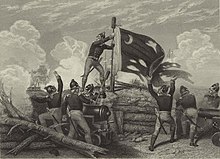

| ] of the 2nd South Carolina Regiment, on a parapet raising the fort's South Carolina Revolutionary flag with its white crescent moon.|Sergeant ] of the ] raises the fort's flag at the ] in ], in June 1776]] | |||

| On April 14, 1775, Sir ], ] and ], received orders to take action against the Patriots. He decided to destroy militia ordnance stored at ], and capture ] and ], who were considered the principal instigators of the rebellion. The operation was to begin around midnight on April 19, in the hope of completing it before the American Patriots could respond.<ref name="oSWXd">], p. 29</ref><ref name="icqWN">Fischer, p. 85</ref> However, ] learned of the plan and notified Captain ], commander of the ] militia, who prepared to resist.<ref name="Q5xrq">], pp. 129–19{{page needed|date=June 2023}}</ref> The first action of the war, commonly referred to as the ], was a brief skirmish at Lexington, followed by the full-scale Battles of Lexington and Concord. British troops suffered around 300 casualties before withdrawing to ], which was then ] by the militia.<ref name="Hyy3u">], pp. 18, 54</ref> | |||

| On the night of April 18, 1775, General Gage sent 700 men to seize munitions stored by the colonial militia at ]. Riders including ] alerted the countryside, and when British troops entered ] on the morning of April 19, they found 77 ] formed up on the village green. Shots were exchanged, killing several minutemen. The British moved on to Concord, where a detachment of three companies was engaged and routed at the North Bridge by a force of 500 minutemen. As the British retreated back to Boston, thousands of militiamen attacked them along the roads, inflicting great damage before timely British reinforcements prevented a total disaster. With the ], the war had begun. | |||

| In May 1775, 4,500 British reinforcements arrived under Generals ], ], and ].<ref name="lSvP0">], pp. 2–9</ref> On June 17, they seized the ] at the ], a frontal assault in which they suffered over 1,000 casualties.<ref name="TZZpb">] , pp. 75–77</ref> Dismayed at the costly attack which had gained them little,<ref name="jP5Oe">], pp. 183, 198–209</ref> Gage appealed to London for a larger army,<ref name="ktPiL">], p. 63</ref> but instead was replaced as commander by Howe.<ref name="TZZpb" /> | |||

| The militia converged on Boston, ] in the city. About 4,500 more British soldiers arrived by sea, and on June 17, 1775, British forces under General ] seized the Charlestown peninsula at the ]. The Americans fell back, but British losses were so heavy that the attack was not followed up. The siege was not broken, and Gage was soon replaced by Howe as the British commander-in-chief.<ref>Higginbotham (1983), pp. 75–77</ref> | |||

| On June 14, 1775, Congress took control of Patriot forces outside Boston, and Congressional leader John Adams nominated Washington as commander-in-chief of the newly formed ].<ref name="nXlAp">], p. 186</ref> On June 16, Hancock officially proclaimed him "General and Commander in Chief of the army of the United Colonies."<ref name="Nx1rV">], p. 187</ref> He assumed command on July 3, preferring to ] outside Boston rather than assaulting it.<ref name="CH6Xw">], p. 53</ref> In early March 1776, Colonel ] arrived with ] acquired in the ].<ref name="rFWWw">], pp. 100–101</ref> Under cover of darkness, on March 5, Washington placed these on Dorchester Heights,<ref name="E7Y0J">], p. 183</ref> from where they could fire on the town and British ships in Boston Harbor. Fearing another Bunker Hill, Howe evacuated the city on ] without further loss and sailed to ], while Washington moved south to New York City.<ref name="IDjnL">], pp. 188–190</ref> | |||

| In July 1775, newly appointed General Washington arrived outside Boston to take charge of the colonial forces and to organize the Continental Army. Realizing his army's desperate shortage of gunpowder, Washington asked for new sources. Arsenals were raided and some manufacturing was attempted; 90% of the supply (2 million pounds) was imported by the end of 1776, mostly from France.<ref>Stephenson (1925), pp. 271–281</ref> Patriots in New Hampshire had seized powder, muskets and cannons from ] in Portsmouth Harbor in late 1774.<ref>* Elwin L. Page. "The King's Powder, 1774", ''New England Quarterly'' Vol. 18, No. 1 (Mar., 1945), pp. 83–92 </ref> Some of the munitions were used in the Boston campaign. | |||

| Beginning in August 1775, ] raided towns in Nova Scotia, including ], ], and ]. In 1776, ] and ] attacked ] and ] respectively. British officials in ] began negotiating with the ] for their support,<ref name="QwMwp">] vol. 1, p. 293</ref> while US envoys urged them to remain neutral.<ref name="yGdMY">], pp. 91, 93</ref> Aware of Native American leanings toward the British and fearing an Anglo-Indian attack from Canada, Congress authorized a second invasion in April 1775.<ref name="eWWH5">], pp. 504–505</ref> After the defeat at the ] on December 31,<ref name="Jfxzh">], pp. 38–39</ref> the Americans maintained a loose blockade of the city until they retreated on May 6, 1776.<ref name="yYbsM">], pp. 141–246</ref> A second defeat at ] on June 8 ended operations in Quebec.<ref name="qYcQ0">], pp. 127–128</ref> | |||

| The standoff continued throughout the fall and winter. In early March 1776, heavy cannons that the patriots had ] were brought to Boston by Colonel ], and ]. Since the artillery now overlooked the British positions, Howe's situation was untenable, and the British fled on March 17, 1776, sailing to their naval base at ], an event now celebrated in Massachusetts as ]. Washington then moved most of the Continental Army to fortify New York City.<ref>{{cite book|author=John R. Alden|title=A History of the American Revolution|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=-o03VtlglokC&pg=PA189|year=1989|publisher=Da Capo Press|pages=188–90}}</ref> | |||

| British pursuit was initially blocked by American naval vessels on ] until victory at ] on October 11 forced the Americans to withdraw to ], while in December an uprising in Nova Scotia sponsored by Massachusetts was defeated at ].<ref name="84Tbw">] vol. 1, p. 242</ref> These failures impacted public support for the Patriot cause,<ref name="MCw6s">], p. 203</ref> and aggressive anti-Loyalist policies in the ] alienated the Canadians.<ref name="ZFLSb">], pp. 264–265</ref> | |||

| ====Quebec==== | |||

| {{Main|Invasion of Canada (1775)}}<!-- This is a brief summary of the main article "Invasion of Canada (1775)". Add details to that article rather than here. --> | |||

| ], December 1775]] | |||

| Three weeks after the siege of Boston began, a troop of militia volunteers led by ] and ] ], a strategically important point on ] between New York and the ]. After that action they also raided ], not far from Montreal, which alarmed the population and the authorities there. In response, Quebec's governor ] began fortifying St. John's, and opened negotiations with the ] and other Native American tribes for their support. These actions, combined with lobbying by both Allen and Arnold and the fear of a British attack from the north, eventually persuaded the Congress to authorize an invasion of Quebec, with the goal of driving the British military from that province. (Quebec was then frequently referred to as ''Canada'', as most of its territory included the former French Province of ].)<ref>Mark R. Anderson, ''The Battle for the Fourteenth Colony: America's War of Liberation in Canada, 1774–1776,'' (University Press of New England; 2013)</ref> | |||

| In Virginia, ] on November 7, 1775, promised freedom to any ] who fled their Patriot masters and agreed to fight for the Crown.<ref name="A8wFb">], p. 74</ref> British forces were defeated at ] on December 9 and took refuge on British ships anchored near Norfolk. When the ] refused to disband its militia or accept martial law, ] ordered the ] on January 1, 1776.<ref name="1FC9n">Russell 2000, p. 73</ref> | |||

| Two Quebec-bound expeditions were undertaken. On September 28, 1775, Brigadier General ] marched north from ] with about 1,700 militiamen, ] on November 2 and then Montreal on November 13. General Carleton escaped to ] and began preparing that city for an attack. The ], led by Colonel Arnold, went through the wilderness of what is now northern Maine. Logistics were difficult, with 300 men turning back, and another 200 perishing due to the harsh conditions. By the time Arnold reached Quebec City in early November, he had but 600 of his original 1,100 men. Montgomery's force joined Arnold's, and they ] on December 31, but were defeated by Carleton in a battle that ended with Montgomery dead, Arnold wounded, and over 400 Americans taken prisoner.<ref>], "Benedict Arnold at Quebec", ''MHQ: Quarterly Journal of Military History,'' Summer 1990, Vol. 2 Issue 4, pp 38–49</ref> The remaining Americans held on outside Quebec City until the spring of 1776, suffering from poor camp conditions and smallpox, and then withdrew when a squadron of British ships under ] arrived to relieve the siege.<ref>Thomas A. Desjardin, ''Through a Howling Wilderness: Benedict Arnold's March to Quebec, 1775'' (2006)</ref> | |||

| The ] began on November 19 in ] between Loyalist and Patriot militias,<ref name="CdDYP">], p. 89</ref> and the Loyalists were subsequently driven out of the colony in the ].<ref name="3Ehts">], pp. 80–81</ref> Loyalists were recruited in ] to reassert British rule in the South, but they were decisively defeated in the ].<ref name="ZWeHt">], p. 33</ref> A British expedition sent to reconquer ] launched an attack on Charleston in the ] on June 28, 1776,<ref name="efEyN">], p. 106</ref> but it failed.<ref name="LWF70">], pp. 154, 158</ref> | |||

| Another attempt was made by the Americans to push back towards Quebec, but they failed at ] on June 8, 1776. Carleton then launched his own invasion and defeated Arnold at the ] in October. Arnold fell back to Fort Ticonderoga, where the invasion had begun. While the invasion ended as a disaster for the Americans, Arnold's efforts in 1776 delayed a full-scale British counteroffensive until the ] of 1777. | |||

| A shortage of gunpowder led Congress to authorize a naval expedition against ] to secure ordnance stored there.<ref name="field104">], p. 104</ref> On March 3, 1776, an American squadron under the command of Esek Hopkins landed at the east end of ] and encountered minimal resistance at ]. Hopkins' troops then marched on ]. Hopkins had promised governor ] and the civilian inhabitants that their lives and property would not be in any danger if they offered no resistance; they complied. Hopkins captured large stores of powder and other munitions that was so great he had to impress an extra ship in the harbor to transport the supplies back home, when he departed on March 17.<ref name="field117-118">], pp. 114–118</ref> A month later, after a ] with {{HMS|Glasgow|1757|6}}, they returned to ], the base for American naval operations.<ref name="I4JgD">], pp. 120–125</ref> | |||

| The invasion cost the Americans their base of support in British public opinion, "So that the violent measures towards America are freely adopted and countenanced by a majority of individuals of all ranks, professions, or occupations, in this country."<ref>Watson (1960), p. 203.</ref> It gained them at best limited support in the population of Quebec, which, while somewhat supportive early in the invasion, became less so later during the occupation, when American policies against suspected Loyalists became harsher, and the army's hard currency ran out. Two small regiments of ]s were recruited during the operation, and they were with the army on its retreat back to Ticonderoga.<ref>Arthur S. Lefkowitz, ''Benedict Arnold's Army: The 1775 American Invasion of Canada during the Revolutionary War'' (2007)</ref> | |||

| ===British New York counter-offensive=== | |||

| ====Other Colonies==== | |||

| {{Main|New York and New Jersey campaign}} | |||

| {{Further|Battle of Fort Washington|Battle of Long Island}} | |||

| ], connecting ] and ], to isolate ] in the ] in November 1776.]] | |||

| In all other colonies the British presence was light to non-existent, enabling the rebels to overwhelm loyalist opposition. Royal governors and officials were simply ignored by new revolutionary governments and were often forced to flee to Royal Navy warships for protection. ] loyalists and patriots fought the ], with victory for the latter by the end of 1775. Virginia's governor ] attempted to rally a loyalist force but was decisively beaten in December 1775 at the ]. In February 1776 British General Clinton took 2,000 men and a naval squadron to assist loyalists mustering in ], only to call it off when he learned they had been crushed at the ]. In June he tried to seize ], the leading port in the South, hoping for a simultaneous rising in South Carolina. It seemed a cheap way of waging the war but ] as the naval force was repulsed by the forts and because no local Loyalists attacked the town from behind. The Loyalists were too poorly organized to be effective, but as late as 1781 senior officials in London, misled by Loyalist exiles, placed their confidence in their rising. {{Citation needed|date=June 2008}} | |||

| After regrouping at ] in Nova Scotia,<ref name="86AtO">], pp. 78–76</ref> Howe set sail for ] in June 1776 and began landing troops on ] near the entrance to ] on July 2. The Americans rejected Howe's informal attempt to negotiate peace on July 30;<ref name="fu3mC">] , p. 104</ref> Washington knew that an attack on the city was imminent and realized that he needed advance information to deal with disciplined British regular troops. | |||

| ===Campaign of 1776–77=== | |||

| On August 12, 1776, Patriot ] was ordered to form an elite group for reconnaissance and secret missions. ], which included ], became the Army's first intelligence unit.<ref name="mgY85">], p. 61</ref>{{Efn|To learn when and where the attack would occur Washington asked for a volunteer among the Rangers to spy on activity behind enemy lines in ]. Young ] stepped forward, but he was only able to provide Washington with nominal intelligence at that time.<ref name="FLQKA">], p. 134</ref> On September 21, Hale was recognized in a ] tavern, and was apprehended with maps and sketches of British fortifications and troop positions in his pockets. Howe ordered that he be summarily hung as a spy without trial the next day.<ref name="lFweM">], Chap. 11</ref>}} When Washington was driven off ], he soon realized that he would need to professionalize military intelligence. With aid from ], Washington launched the six-man ].<ref name="Baker 2014, Chap.12">], Chap. 12</ref>{{Efn|Tallmadge's cover name became John Bolton, and he was the architect of the spy ring.<ref name="Baker 2014, Chap.12" />}} The efforts of Washington and the Culper Spy Ring substantially increased the effective allocation and deployment of Continental regiments in the field.<ref name="Baker 2014, Chap.12" /> Throughout the war, Washington spent more than 10 percent of his total military funds on ].<ref name="w8uDs">]</ref> | |||

| ====New York==== | |||

| Washington split the Continental Army into positions on ] and across the ] in western Long Island.<ref name="QzdDu">], pp. 89, 381</ref> On August 27 at the ], Howe outflanked Washington and forced him back to ], but he did not attempt to encircle Washington's forces.<ref name="04huq">] , p. 657</ref> Through the night of August 28, Knox bombarded the British. Knowing they were up against overwhelming odds, Washington ordered the assembly of a war council on August 29; all agreed to retreat to Manhattan. Washington quickly had his troops assembled and ferried them across the East River to Manhattan on flat-bottomed ] without any losses in men or ordnance, leaving General ]'s regiments as a rearguard.<ref name="2BFMO">], pp. 184–186</ref> | |||

| {{Main|New York and New Jersey campaign}} <!-- This is a brief summary of the "New York and New Jersey campaigns" article. Add more details there rather than here. --> | |||

| ], 1776]] | |||

| Howe met with a delegation from the Second Continental Congress at the September ], but it failed to conclude peace, largely because the British delegates only had the authority to offer pardons and could not recognize independence.<ref name="4FsKF">], pp. 165–166</ref> On September 15, Howe seized control of New York City when the British ] and unsuccessfully engaged the Americans at the ] the following day.<ref name="5YPyI">], pp. 102–107</ref> On October 18, Howe failed to encircle the Americans at the ], and the Americans withdrew. Howe declined to close with Washington's army on October 28 at the ] and instead attacked a hill that was of no strategic value.<ref name="baDUW">], pp. 102–111</ref> | |||

| Having withdrawn his army from Boston, General Howe now focused on capturing New York City, which then was limited to the southern tip of Manhattan Island. Howe's force arrived off of ] on June 30, 1776, and his army landed there without resistance. To defend the city, General Washington spread his forces along the shores of New York's harbor, concentrated on ] and ].<ref>Fischer (2004), pp. 51–52,83</ref> While British and recently hired ] troops were assembling, Washington had the newly issued ] read to his men and the citizens of the city.<ref>Fischer (2004), p. 29</ref> | |||

| Washington's retreat isolated his remaining forces and the British captured ] on November 16. The British victory there amounted to Washington's most disastrous defeat with the loss of 3,000 prisoners.<ref name="iikrS">] , pp. 111, 130</ref> The remaining American regiments on Long Island fell back four days later.<ref name="ImjPu">], pp. 109–125</ref> General ] wanted to pursue Washington's disorganized army, but he was first required to commit 6,000 troops to capture ], to secure the Loyalist port.<ref name="uekYy">], p. 122</ref>{{Efn|The American prisoners were subsequently sent to the ] in the ], where more American soldiers and sailors died of disease and neglect than died in every battle of the war combined.<ref name="YCPdp">], pp. 61, 131</ref>}} General ] pursued Washington, but Howe ordered him to halt.<ref name="1TXji">], pp. 22–23</ref> | |||

| Washington's position was extremely dangerous because he had divided his forces between ] and ], exposing both to defeat in detail. The British landed 22,000 men on Long Island in late August and ] in the war's largest battle, taking over 1,000 prisoners and driving them back to ]. Howe then laid siege to the heights, claiming he wanted to spare his men's lives from an immediate assault, although by his own admission such an assault would have succeeded. Washington initially reinforced his exposed position, but then personally directed the ] of his entire remaining army and all their supplies across the ] on the night of August 29–30 without significant loss of men and ].<ref>Fischer (2004), pp. 91–101</ref> Howe was aware of the retreat, but did not order a pursuit until it was too late.<ref>John J. Gallagher, ''The Battle of Brooklyn 1776'' (2009)</ref> | |||

| The outlook following the defeat at Fort Washington appeared bleak for the American cause. The reduced Continental Army had dwindled to fewer than 5,000 men and was reduced further when enlistments expired at the end of the year.<ref name="U9aPa">], pp. 266–267</ref> Popular support wavered, and morale declined. On December 20, 1776, the Continental Congress abandoned the revolutionary capital of Philadelphia and moved to ], where it remained until February 27, 1777.<ref name="SpAkV">], pp. 138–142</ref> Loyalist activity surged in the wake of the American defeat, especially in ].<ref name="kPQRy">], p. 139</ref> | |||

| After a ] on September 11, Howe resumed the attack. On September 15, Howe ] on lower Manhattan, quickly taking control of New York City. The Americans withdrew north up the island to Harlem Heights, where they ] but held their ground. On September 21 a ] broke out in the city, for which the rebels were widely blamed although no conclusive proof exists. On October 12 the British made an attempt to encircle the Americans, which failed because of Howe's decision to land on an island that was easily cut off from the mainland.<ref>John Richard Alden, ''The American Revolution, 1775–1783'' (1954) ch 7</ref> The Americans evacuated Manhattan, and on October 28 fought the ] against the pursuing British. During the battle Howe declined to attack the Washington's highly vulnerable main force, instead attacking a hill that was of no strategic significance.<ref>Fischer (2004), pp. 102–111</ref><ref>Barnet Schecter, ''The battle for New York: The city at the heart of the American Revolution'' (2002).</ref> | |||

| In London, news of the victorious Long Island campaign was well received with festivities held in the capital. Public support reached a peak.<ref name="sCNCR">], p. 195</ref> Strategic deficiencies among Patriot forces were evident: Washington divided a numerically weaker army in the face of a stronger one, his inexperienced staff misread the military situation, and American troops fled in the face of enemy fire. The successes led to predictions that the British could win within a year.<ref name="bCOlv">] , pp. 650–670</ref> The British established winter quarters in the New York City area and anticipated renewed campaigning the following spring.<ref name="w14iW">], pp. 259–263</ref> | |||

| Washington retreated, and Howe returned to Manhattan and captured ] in mid November, taking about 3,000 prisoners. Thus began ] the British maintained in New York for the rest of the war, in which more American soldiers and sailors ] than died in every battle of the entire war, combined.<ref>Larry Lowenthal, ''Hell on the East River: British Prison Ships in the American Revolution'' (2009)</ref> | |||

| ===Patriot resurgence=== | |||

| Howe then detached General Clinton with 6,000 men to seize ] for the British fleet, which was accomplished without encountering any major resistance.<ref>{{cite book|author=David McCullough|title=1776|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=5LBVT46o5yQC&pg=PT122|year=2006|page=122}}</ref> Clinton objected to this move, believing the force would have been better employed up the Delaware river where they might have inflicted irreparable damage on the retreating Americans.<ref>Stedman, Charles (1794) p. 221</ref> | |||

| {{Further|George Washington's crossing of the Delaware River|Battle of Trenton|Battle of Princeton}} | |||

| ]'', an iconic 1851 ] portrait depicting ]]] | |||

| ], the last U.S. president to fight in the Revolutionary War as a ] officer, took part in the ] and the ] alongside ]]] | |||

| On the night of December 25–26, 1776, Washington ], leading a column of Continental Army troops from today's ], to today's ], in a logistically challenging and dangerous operation. | |||

| ====New Jersey==== | |||

| Meanwhile, the Hessians were involved in numerous clashes with small bands of Patriots and were often aroused by false alarms at night in the weeks before the actual ]. By Christmas they were tired, while a heavy snowstorm led their commander, Colonel ], to assume no significant attack would occur.<ref>], p. 122</ref> At daybreak on the 26th, the American Patriots surprised and overwhelmed Rall and his troops, who lost over 20 killed including Rall,<ref>], pp. 248, 255</ref> while 900 prisoners, German cannons and supplies were captured.<ref name="QceAB">], pp. 206–208, 254</ref> | |||

| ] continued to chase Washington's army through ] but Howe ordered him to halt, letting Washington escape across the ] into Pennsylvania on December 7.<ref>Stedman, Charles (1794) p. 223</ref> Howe refused to order a pursuit across the river, even though the outlook of the Continental Army was bleak. "These are the times that try men's souls," wrote ], who was with the army on the retreat.<ref>Fischer (2004), pp. 138–140</ref> The army had dwindled to fewer than 5,000 men fit for duty, and would be reduced to 1,400 after enlistments expired at the end of the year.{{Citation needed|date=April 2010}} Congress had abandoned Philadelphia in despair, although popular resistance to British occupation was growing in the countryside.<ref>Fischer (2004), pp. 143–205</ref> | |||

| The Battle of Trenton restored the American army's morale, reinvigorated the Patriot cause,<ref name="mjfFg">], pp. 72–74</ref> and dispelled their fear of what they regarded as Hessian "mercenaries".<ref name="yIUgZ">], p. 416</ref> A British attempt to retake Trenton was repulsed at ] on January 2;<ref name="GGEem">], p. 307</ref> during the night, Washington outmaneuvered Cornwallis, then defeated his rearguard in the ] the following day. The two victories helped convince the French that the Americans were worthy military allies.<ref name="G2skh">], p. 290</ref> | |||

| ]'s stylized depiction of '']'' (1851)]] | |||

| After his success at Princeton, Washington entered winter quarters at ], where he remained until May<ref name="sZDyW">], p. 208</ref> and received Congressional direction to inoculate all Patriot troops against ].<ref name="4ru2u">], "Writings" v. 7, pp. 38, 130–131</ref>{{efn|The mandate came by way of Benjamin Rush, chair of the Medical Committee. Congress had directed that all troops who had not previously survived smallpox infection be inoculated. In explaining himself to state governors, Washington lamented that he had lost "an army" to smallpox in 1776 by the "Natural way" of immunity.<ref name="fsQm0">], "Writings" v. 7, pp. 131, 130</ref>}} With the exception of a ] between the two armies which continued until March,<ref name="T0TSz">], pp. 345–358</ref> Howe made no attempt to attack the Americans.<ref name="MdrQi">] Vol. 4, p. 57</ref> | |||

| Howe proceeded to divide his forces in New Jersey into small detachments that were vulnerable to defeat in detail, with the weakest forces stationed the closest to Washington's army.<ref>Stedman, Charles (1794) pp. 224–225</ref> Washington decided to take the offensive, ] on the night of December 25–26, and capturing nearly 1,000 surprised and unfortified Hessians at the ].<ref>Fischer (2004), pp. 206–259</ref> Cornwallis marched to retake Trenton but was first ] and then outmaneuvered by Washington, who successfully attacked the British rearguard at ] on January 3, 1777, taking around 200 prisoners.<ref>Fischer (2004), pp. 277–343</ref> Howe then conceded most of New Jersey to Washington, in spite of Howe's massive numerical superiority over him.<ref>Stedman, Charles (1794) p. 239</ref> Washington entered winter quarters at ], having given a morale boost to the American cause. Throughout the winter New Jersey militia ] British and Hessian forces near their three remaining posts along the ].<ref>Fischer (2004), pp. 345–358</ref> | |||

| === |

===British northern strategy fails=== | ||

| {{Further|Saratoga campaign|Philadelphia campaign|Valley Forge}} | |||

| ] leader ] led both Native Americans and ] ] in battle.]] | |||

| ] maneuvers and (inset) the ] in September and October 1777]] | |||

| ]" shows General ] in front of a French ] 4-pounder.]] | |||

| ] and ] look over the troops at ].]] | |||