| Revision as of 13:05, 24 April 2011 editCruithneach77 (talk | contribs)122 editsNo edit summary← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 00:35, 5 January 2025 edit undoABasilisk999 (talk | contribs)9 editsm redundancyTag: Visual edit | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|State of increased suggestibility}} | |||

| {{For|the states induced by ] drugs|Sleep|Unconsciousness}} | |||

| {{Redirect|Hypnotized}} | {{Redirect-several|dab=off|Hypnotized (disambiguation)|Hypnotize (disambiguation)|Hypnotist (disambiguation)}} | ||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=January 2020}} | |||

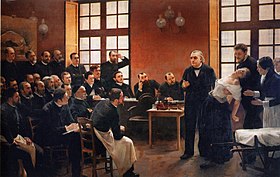

| {{Infobox medical intervention |name=Hypnosis|image=File:Une leçon clinique à la Salpêtrière.jpg|caption= ] demonstrating hypnosis on a "]" '']'' patient, "Blanche" (]), who is supported by ]<ref>See: ].</ref>|ICD10=|ICD9=|MeshID=D006990|OPS301=|other_codes=|HCPCSlevel2=}} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Hypnosis}} | {{Hypnosis}} | ||

| '''Hypnosis''' is a mental state (according to "state theory") or imaginative role-enactment (according to "non-state theory").<ref>Lynn S, Fassler O, Knox J (2005) ''Hypnosis and the altered state debate: something more or nothing more?'' Contemporary Hypnosis Vol 22, 1</ref><ref>Coe W, Buckner L, Howard M, Kobayashi K (1972) ''Hypnosis as role enactment: focus on a role specific skill'', American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis Jul 15(1):41-5</ref><ref>Lynn S, Rhue J (1991) ''Theories of Hypnosis'',The Guilford Press</ref><ref>Barber T.X., Spanos N, Chaves J (1974) ''Hypnotism: Imagination & Human Potentialities''</ref> It is usually induced by a procedure known as a hypnotic induction, which is commonly composed of a long series of preliminary instructions and suggestions.<ref>"New Definition: Hypnosis" Division 30 of the American Psychological Association </ref> Hypnotic suggestions may be delivered by a hypnotist in the presence of the subject, or may be self-administered ("self-suggestion" or "autosuggestion"). The use of hypnotism for therapeutic purposes is referred to as "]", while its use as a form of entertainment for an audience is known as "]". | |||

| '''Hypnosis''' is a human condition involving focused ] (the selective attention/selective inattention hypothesis, SASI),<ref name="SI Hall">{{cite journal |last1=Hall |first1=Harriet |authorlink= Harriet Hall|title=Hypnosis revisited |journal=Skeptical Inquirer |date=2021 |volume=45 |issue=2 |pages=17–19}}</ref> reduced peripheral awareness, and an enhanced capacity to respond to ].<ref name="Lynn SJ 2015">In 2015, the ] Division 30 defined hypnosis as a "state of consciousness involving focused attention and reduced peripheral awareness characterized by an enhanced capacity for response to suggestion". For critical commentary on this definition, see: {{cite journal | vauthors = Lynn SJ, Green JP, Kirsch I, Capafons A, Lilienfeld SO, Laurence JR, Montgomery GH | title = Grounding Hypnosis in Science: The "New" APA Division 30 Definition of Hypnosis as a Step Backward | journal = The American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis | volume = 57 | issue = 4 | pages = 390–401 | date = April 2015 | pmid = 25928778 | doi = 10.1080/00029157.2015.1011472 | s2cid = 10797114}}</ref> | |||

| The words ''hypnosis'' and ''hypnotism'' both derive from the term ''neuro-hypnotism'' (nervous sleep) coined by the Scottish surgeon ] around 1841. Braid based his practice on that developed by ] and his followers ("]" or "]"), but differed in his theory as to how the procedure worked. | |||

| There are competing theories explaining hypnosis and related phenomena. ''Altered state'' theories see hypnosis as an ] or ], marked by a level of awareness different from the ordinary ].<ref>''Encyclopædia Britannica'', 2004: "a special psychological state with certain physiological attributes, resembling sleep only superficially and marked by a functioning of the individual at a level of awareness other than the ordinary conscious state".</ref><ref>{{cite book|author1=Erika Fromm|author2=Ronald E. Shor|title=Hypnosis: Developments in Research and New Perspectives|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=fgBrdEoTu3AC&q=hypnosis|access-date=27 September 2014|date=2009|publisher=Rutgers|isbn=978-0-202-36262-5|archive-date=2 July 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230702162804/https://books.google.com/books?id=fgBrdEoTu3AC&q=hypnosis|url-status=live}}</ref> In contrast, ''non-state'' theories see hypnosis as, variously, a type of placebo effect,<ref name=":0">{{cite journal | vauthors = Kirsch I | title = Clinical hypnosis as a nondeceptive placebo: empirically derived techniques | journal = The American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis | volume = 37 | issue = 2 | pages = 95–106 | date = October 1994 | pmid = 7992808 | doi = 10.1080/00029157.1994.10403122}}</ref><ref name=":1">Kirsch, I., "Clinical Hypnosis as a Nondeceptive Placebo", pp. 211–25 in Kirsch, I., Capafons, A., Cardeña-Buelna, E., Amigó, S. (eds.), ''Clinical Hypnosis and Self-Regulation: Cognitive-Behavioral Perspectives'', American Psychological Association, (Washington), 1999 {{ISBN|1-55798-535-9}}</ref> a redefinition of an interaction with a therapist<ref>{{cite book|title=Hypnosis: A Scientific Approach|author=Theodore X. Barber|publisher=J. Aronson, 1995|year=1969|isbn=978-1-56821-740-6|author-link=Theodore X. Barber}}</ref> or a form of imaginative ].<ref>{{cite journal|vauthors=Lynn S, Fassler O, Knox J|title=Hypnosis and the altered state debate: something more or nothing more?|doi=10.1002/ch.21|year=2005|journal=Contemporary Hypnosis|volume=22|pages=39–45}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Coe WC, Buckner LG, Howard ML, Kobayashi K | title = Hypnosis as role enactment: focus on a role specific skill | journal = The American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis | volume = 15 | issue = 1 | pages = 41–45 | date = July 1972 | pmid = 4679790 | doi = 10.1080/00029157.1972.10402209}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author1=Steven J. Lynn|author2=Judith W. Rhue|title=Theories of hypnosis: current models and perspectives|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Ez7Nq80QMtoC|access-date=30 October 2011|year=1991|publisher=Guilford Press|isbn=978-0-89862-343-7|archive-date=2 July 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230702162816/https://books.google.com/books?id=Ez7Nq80QMtoC|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| Contrary to a popular misconception – that hypnosis is a form of ] resembling sleep – contemporary research suggests that hypnotic subjects are fully awake and are focusing attention, with a corresponding decrease in their peripheral awareness.<ref>p. 22, ] and Spiegel, David. Trance and Treatment. Basic Books Inc., New York. 1978. ISBN 0-465-08687-X</ref></blockquote> Subjects also show an increased response to suggestions.<ref></ref> In the first book on the subject, ''Neurypnology'' (1843), Braid described "hypnotism" as a state of physical relaxation accompanied and induced by mental concentration ("abstraction").<ref>Braid, J. (1843) Neurypnology.</ref> | |||

| During hypnosis, a person is said to have heightened focus and ]<ref>Orne, M. T. (1962). On the social psychology of the psychological experiment: With particular reference to demand characteristics and their implications. American | |||

| ==Characteristics== | |||

| Psychologist, 17, 776-783</ref><ref name="Segi">{{cite journal | last= Segi |first= Sherril |year=2012 |title=Hypnosis for pain management, anxiety and behavioral disorders |journal=The Clinical Advisor: For Nurse Practitioners|issn=1524-7317|volume=15|issue=3|page=80}}</ref> and an increased response to suggestions.<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081007194608/http://www.columbia.edu/cu/news/05/07/neural_pathways.html |date=7 October 2008 }}. Columbia.edu. Retrieved on 1 October 2011.</ref> | |||

| It could be said that hypnotic suggestion is explicitly intended to make use of the placebo effect. For example, in 1994, Irving Kirsch proposed a definition of hypnosis as a "nondeceptive mega-placebo," i. e., a method which openly makes use of suggestion and employs methods to amplify its effects.<ref>Kirsch, I., "Clinical Hypnosis as a Nondeceptive Placebo: Empirically Derived Techniques", ''American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis'', Vol.37, No.2, (October 1994), pp.95-106; Kirsch, I., "Clinical Hypnosis as a Nondeceptive Placebo", pp.211-225 in Kirsch, I., Capafons, A., Cardeña-Buelna, E., Amigó, S. (eds.), ''Clinical Hypnosis and Self-Regulation: Cognitive-Behavioral Perspectives'', American Psychological Association, (Washington), 1999.</ref> | |||

| Hypnosis usually begins with a ] involving a series of preliminary instructions and suggestions. The use of hypnosis for therapeutic purposes is referred to as "]",<ref>Spanos, N. P., Spillane, J., & McPeake, J. D. (1976). Cognitive strategies and response to suggestion in hypnotic | |||

| and task-motivated subjects. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 18, 252-262.</ref> while its use as a form of entertainment for an audience is known as "]", a form of ]. | |||

| Hypnosis-based therapies for the management of ] and ] are supported by evidence.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Lacy|first1=Brian E.|last2=Pimentel|first2=Mark|last3=Brenner|first3=Darren M.|last4=Chey|first4=William D.|last5=Keefer|first5=Laurie A.|last6=Long|first6=Millie D.|last7=Moshiree|first7=Baha|date=January 2021|title=ACG Clinical Guideline: Management of Irritable Bowel Syndrome|journal= American Journal of Gastroenterology|language=en-US|volume=116|issue=1|pages=17–44|doi=10.14309/ajg.0000000000001036|pmid=33315591|issn=0002-9270|doi-access=free}}</ref><ref name="auto">{{Cite journal|date=November 2015|title=Nonhormonal management of menopause-associated vasomotor symptoms: 2015 position statement of The North American Menopause Society|url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26382310/|journal=Menopause|volume=22|issue=11|pages=1155–1172; quiz 1173–1174|doi=10.1097/GME.0000000000000546|issn=1530-0374|pmid=26382310|s2cid=14841660|access-date=7 September 2021|archive-date=22 March 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210322145613/https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26382310/|url-status=live}}</ref> The use of hypnosis as a form of therapy to retrieve and integrate early trauma is controversial within the scientific mainstream. Research indicates that hypnotising an individual may aid the formation of false memories,<ref>{{cite book |last1=Lynn |first1=Steven Jay |last2=Krackow |first2=Elisa |last3=Loftus |first3=Elizabeth F. |author-link3=Elizabeth Loftus |last4=Locke |first4=Timothy G. |last5=Lilienfeld |first5=Scott O. |author-link5=Scott Lilienfeld |date=2014 |chapter=Constructing the past: problematic memory recovery techniques in psychotherapy |editor1-last=Lilienfeld |editor1-first=Scott O. |editor2-last=Lynn |editor2-first=Steven Jay |editor3-last=Lohr |editor3-first=Jeffrey M. |title=Science and pseudoscience in clinical psychology |edition=2nd |location=New York |publisher=] |pages=245–275 |isbn=9781462517510 |oclc=890851087}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=French |first=Christopher C. |url=https://www.academia.edu/101922617 |title=The Reliability of UFO Witness Testimony |publisher=UPIAR |year=2023 |isbn=9791281441002 |editor-last=Ballester-Olmos |editor-first=V.J. |location=Turin, Italy |pages=283–294 |chapter=Hypnotic Regression and False Memories |editor-last2=Heiden |editor-first2=Richard W.}}</ref> and that hypnosis "does not help people recall events more accurately".<ref>{{cite news |last1=Hall |first1=Celia |title=Hypnosis does not help accurate memory recall, says study |url=https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/1338671/Hypnosis-does-not-help-accurate-memory-recall-says-study.html |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20220111/https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/1338671/Hypnosis-does-not-help-accurate-memory-recall-says-study.html |archive-date=11 January 2022 |url-access=subscription |url-status=live |website=Telegraph |access-date=11 March 2019|date=26 August 2001}}{{cbignore}}</ref> Medical hypnosis is often considered ] or ].<ref name="naud">{{cite journal |last1=Naudet |first1=Florian |last2=Falissard |first2=Bruno |author2-link=Bruno Falissard |last3=Boussageon |first3=Rémy |last4=Healy |first4=David |date=2015 |title=Has evidence-based medicine left quackery behind? |url=https://hal-univ-rennes1.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01138648/file/Has%20evidence-based%20medicine%20left%20quackery%20behind_accepted.pdf |journal=Internal and Emergency Medicine |volume=10 |issue=5 |pages=631–634 |doi=10.1007/s11739-015-1227-3 |issn=1970-9366 |pmid=25828467 |s2cid=20697592 |quote=Treatments such as relaxation techniques, chiropractic, therapeutic massage, special diets, megavitamins, acupuncture, naturopathy, homeopathy, hypnosis and psychoanalysis are often considered as ‘‘pseudoscience’’ or ‘‘quackery’’ with no credible or respectable place in medicine, because in evaluation they have not been shown to ‘‘work’’}}</ref> | |||

| ], a professional magician and ], provides a definition of hypnosis as "a mutual agreement of the operator and the subject that the subject will cooperate in following suggestions".<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.randi.org/encyclopedia/hypnotism_hypnosis.html |title=James Randi Educational Foundation — An Encyclopedia of Claims, Frauds, and Hoaxes of the Occult and Supernatural |work= |accessdate=}}</ref> | |||

| {{TOC limit|3}} | |||

| == |

== Etymology == | ||

| The words ''hypnosis'' and ''hypnotism'' both derive from the term ''neuro-hypnotism'' (nervous sleep), all of which were coined by ] in the 1820s. The term ''hypnosis'' is derived from the ] ὑπνος ''hypnos'', "sleep", and the ] -ωσις -''osis'', or from ὑπνόω ''hypnoō'', "put to sleep" (] of ] ''hypnōs''-) and the suffix -''is''.<ref>''{{LSJ|u(/pnos|hypnos}}'', ''{{LSJ|u(pno/w|hypnoō|ref}}''.</ref><ref>{{OEtymD|hypnosis}}</ref> These words were popularised in ] by the ] surgeon ] (to whom they are sometimes wrongly attributed) around 1841.{{Citation needed|date=August 2024}} Braid based his practice on that developed by ] and his followers (which was called "Mesmerism" or "]"), but differed in his theory as to how the procedure worked. | |||

| The earliest definition of hypnosis was given by Braid, who coined the term "hypnotism" as an abbreviation for "neuro-hypnotism", or nervous sleep, which he opposed to ''normal'' sleep, and defined as: "a peculiar condition of the nervous system, induced by a fixed and abstracted attention of the mental and visual eye, on one object, not of an exciting nature."<ref>Braid, Neurypnology, 1843: 'Introduction'</ref> | |||

| == Definition and classification == | |||

| Braid elaborated upon this brief definition in a later work: | |||

| A person in a state of hypnosis has focused attention, deeply relaxed physical and mental state and has increased ].<ref>T.L. Brink. (2008) Psychology: A Student Friendly Approach. "Unit 5: Perception." p. 88 {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120416002209/http://www.saylor.org/site/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/TLBrink_PSYCH05.pdf|date=16 April 2012}}</ref> | |||

| {{quote| the real origin and essence of the hypnotic condition, is the induction of a habit of abstraction or mental concentration, in which, as in reverie or spontaneous abstraction, the powers of the mind are so much engrossed with a single idea or train of thought, as, for the nonce, to render the individual unconscious of, or indifferently conscious to, all other ideas, impressions, or trains of thought. The ''hypnotic'' sleep, therefore, is the very antithesis or opposite mental and physical condition to that which precedes and accompanies ''common'' sleep |Braid, ''Hypnotic Therapeutics'', 1853}} | |||

| {{blockquote|text=The hypnotized individual appears to heed only the communications of the hypnotist and typically responds in an uncritical, automatic fashion while ignoring all aspects of the environment other than those pointed out by the hypnotist. In a hypnotic state an individual tends to see, feel, smell, and otherwise perceive in accordance with the hypnotist's suggestions, even though these suggestions may be in apparent contradiction to the actual stimuli present in the environment. The effects of hypnosis are not limited to sensory change; even the subject's memory and awareness of self may be altered by suggestion, and the effects of the suggestions may be extended (post-hypnotically) into the subject's subsequent waking activity.<ref>"hypnosis." ''Encyclopædia Britannica'' web edition. Retrieved: 20 March 2016.</ref>}} | |||

| It could be said that hypnotic suggestion is explicitly intended to make use of the ] effect. For example, in 1994, ] characterized hypnosis as a "non-deceptive placebo", i.e., a method that openly makes use of suggestion and employs methods to amplify its effects.<ref name=":0"/><ref name=":1"/> | |||

| A definition of hypnosis, derived from academic ], was provided in 2005, when the Society for Psychological Hypnosis, Division 30 of the ] (APA), published the following formal definition: | |||

| Braid therefore defined hypnotism as a state of mental concentration which often led to a form of progressive relaxation termed "nervous sleep". Later, in his ''The Physiology of Fascination'' (1855), Braid conceded that his original terminology was misleading, and argued that the term "hypnotism" or "nervous sleep" should be reserved for the minority (10%) of subjects who exhibited ], substituting the term "monoideism", meaning concentration upon a single idea, as a description for the more alert state experienced by the others. | |||

| {{blockquote|Hypnosis typically involves an introduction to the procedure during which the subject is told that suggestions for imaginative experiences will be presented. The hypnotic induction is an extended initial suggestion for using one's imagination, and may contain further elaborations of the introduction. A hypnotic procedure is used to encourage and evaluate responses to suggestions. When using hypnosis, one person (the subject) is guided by another (the hypnotist) to respond to suggestions for changes in subjective experience, alterations in perception,<ref name="Leslie">{{citation |url=http://news.stanford.edu/news/2000/september6/hypnosis-96.html |title=Research supports the notion that hypnosis can transform perception |work=Stanford Report |last=Leslie |first=Mitch |name-list-style=vanc |date=6 September 2000 |publisher=Stanford University |access-date=16 June 2013 |archive-date=2 August 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130802154015/http://news.stanford.edu/news/2000/september6/hypnosis-96.html |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="Mauera">{{cite journal | vauthors = Mauer MH, Burnett KF, Ouellette EA, Ironson GH, Dandes HM | title = Medical hypnosis and orthopedic hand surgery: pain perception, postoperative recovery, and therapeutic comfort | journal = The International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis | volume = 47 | issue = 2 | pages = 144–61 | date = April 1999 | pmid = 10208075 | doi = 10.1080/00207149908410027}}</ref> sensation,<ref name="De Pascalis">{{cite journal | vauthors = De Pascalis V, Magurano MR, Bellusci A | title = Pain perception, somatosensory event-related potentials and skin conductance responses to painful stimuli in high, mid, and low hypnotizable subjects: effects of differential pain reduction strategies | journal = Pain | volume = 83 | issue = 3 | pages = 499–508 | date = December 1999 | pmid = 10568858 | doi = 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00157-8 | s2cid = 3158482 | id = {{INIST|1291393}}}}</ref> emotion, thought or behavior. Persons can also learn self-hypnosis, which is the act of administering hypnotic procedures on one's own. If the subject responds to hypnotic suggestions, it is generally inferred that hypnosis has been induced. Many believe that hypnotic responses and experiences are characteristic of a hypnotic state. While some think that it is not necessary to use the word "hypnosis" as part of the hypnotic induction, others view it as essential.<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080910220114/http://www.apa.org/divisions/div30/define_hypnosis.html |date=10 September 2008 }}. Society of Psychological Hypnosis Division 30 – American Psychological Association.</ref>}} | |||

| A new definition of hypnosis, derived from academic psychology, was provided in 2005, when the Society for Psychological Hypnosis, Division 30 of the ] (APA), published the following formal definition: | |||

| Michael Nash provides a list of eight definitions of hypnosis by different authors, in addition to his own view that hypnosis is "a special case of psychological ]": | |||

| {{quotation| | |||

| # ], near the turn of the century, and more recently ] ..., have defined hypnosis in terms of ]. | |||

| '''<big>New Definition: Hypnosis</big>'''<br /> | |||

| # ]s Sarbin and Coe ... have described hypnosis in terms of ]. Hypnosis is a role that people play; they act "as if" they were hypnotised. | |||

| <br /> | |||

| # ] ... defined hypnosis in terms of nonhypnotic behavioural parameters, such as task motivation and the act of labeling the situation as hypnosis. | |||

| '''The Division 30 Definition and Description of Hypnosis'''<br /> | |||

| # In his early writings, ] ... conceptualised hypnosis as a state of enhanced suggestibility. Most recently ... he has defined hypnotism as "a form of influence by one person exerted on another through the medium or agency of suggestion." | |||

| <br /> | |||

| # ]s Gill and Brenman ... described hypnosis by using the psychoanalytic concept of "regression in the service of the ego". | |||

| Hypnosis typically involves an introduction to the procedure during which the subject is told that suggestions for imaginative experiences will be presented. The hypnotic induction is an extended initial suggestion for using one's imagination, and may contain further elaborations of the introduction. A hypnotic procedure is used to encourage and evaluate responses to suggestions. When using hypnosis, one person (the subject) is guided by another (the hypnotist) to respond to suggestions for changes in subjective experience, alterations in perception, sensation, emotion, thought or behavior. Persons can also learn self-hypnosis, which is the act of administering hypnotic procedures on one's own. If the subject responds to hypnotic suggestions, it is generally inferred that hypnosis has been induced. Many believe that hypnotic responses and experiences are characteristic of a hypnotic state. While some think that it is not necessary to use the word "hypnosis" as part of the hypnotic induction, others view it as essential.<br /> | |||

| # Edmonston ... has assessed hypnosis as being merely a state of relaxation. | |||

| <br /> | |||

| # Spiegel and Spiegel... have implied that hypnosis is a biological capacity.<ref name="books.google.com">{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Ez7Nq80QMtoC|title=Theories of Hypnosis: Current Models and Perspectives|first1=Steven J.|last1=Lynn|first2=Judith W.|last2=Rhue|date=4 October 1991|publisher=Guilford Press|isbn=9780898623437|via=Google Books|access-date=7 November 2015|archive-date=2 July 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230702162816/https://books.google.com/books?id=Ez7Nq80QMtoC|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| Details of hypnotic procedures and suggestions will differ depending on the goals of the practitioner and the purposes of the clinical or research endeavor. Procedures traditionally involve suggestions to relax, though relaxation is not necessary for hypnosis and a wide variety of suggestions can be used including those to become more alert. Suggestions that permit the extent of hypnosis to be assessed by comparing responses to standardized scales can be used in both clinical and research settings. While the majority of individuals are responsive to at least some suggestions, scores on standardized scales range from high to negligible. Traditionally, scores are grouped into low, medium, and high categories. As is the case with other positively-scaled measures of psychological constructs such as attention and awareness, the salience of evidence for having achieved hypnosis increases with the individual's score.<ref>"New Definition: Hypnosis" Society of Psychological Hypnosis Division 30 - American Psychological Association .</ref>}} | |||

| # ] ... is considered the leading exponent of the position that hypnosis is a special, inner-directed, altered state of functioning.<ref name="books.google.com"/> | |||

| Joe Griffin and ] (the originators of the ]) define hypnosis as "any artificial way of accessing the ] state, the same brain state in which dreaming occurs" and suggest that this definition, when properly understood, resolves "many of the mysteries and controversies surrounding hypnosis".<ref>{{cite book |last1=Griffin |first1=Joe |last2=Tyrrell |first2=Ivan |name-list-style=vanc |title=Human Givens: The new approach to emotional health and clear thinking |date=2013 |publisher=HG Publishing |isbn=978-1-899398-31-7 |page=67 |url=http://www.humangivens.com/publications/human-givens-book.html |access-date=24 February 2015 |archive-date=8 October 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141008073609/http://www.humangivens.com/publications/human-givens-book.html |url-status=live }}</ref> They see the REM state as being vitally important for life itself, for programming in our instinctive knowledge initially (after Dement<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Roffwarg HP, Muzio JN, Dement WC | title = Ontogenetic development of the human sleep-dream cycle | journal = Science | volume = 152 | issue = 3722 | pages = 604–19 | date = April 1966 | pmid = 17779492 | doi = 10.1126/science.152.3722.604 | bibcode = 1966Sci...152..604R}}</ref> and Jouvet<ref>{{cite book |chapter=Does a genetic programming of the brain occur during paradoxical sleep |year=1978 |first=M |last=Jouvet |editor-last1=Buser|editor-first1=Pierre A.|editor-last2=Rougeul-Buser|editor-first2=Arlette| name-list-style = vanc |title=Cerebral correlates of conscious experience: proceedings of an international symposium on cerebral correlates of conscious experience, held in Senanque Abbey, France, on 2–8 August 1977|publisher=North-Holland|location=New York|isbn=978-0-7204-0659-7}}</ref>) and then for adding to this throughout life. They attempt to explain this by asserting that, in a sense, all learning is post-hypnotic, which they say explains why the number of ways people can be put into a hypnotic state are so varied: according to them, anything that focuses a person's attention, inward or outward, puts them into a trance.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Griffin|first1=Joe|last2=Tyrrell|first2=Ivan|name-list-style=vanc|title=Godhead: the brain's big bang: the strange origin of creativity, mysticism and mental illness|date=2011|publisher=Human Givens|location=Chalvington|isbn=978-1-899398-27-0|pages=106–22|url=http://www.griffintyrrell.co.uk/creativity-mysticism-and-mental-illness.php|access-date=24 February 2015|archive-date=25 March 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150325000932/http://www.griffintyrrell.co.uk/creativity-mysticism-and-mental-illness.php|url-status=live}}</ref><!-- fails verification: <ref name="Bewley Ross Braillon Ernst 2011 p. d5960">{{cite journal | last1=Bewley | first1=Susan | last2=Ross | first2=Nick | last3=Braillon | first3=Alain | last4=Ernst | first4=Edzard | last5=Garrow | first5=John | last6=Rose | first6=Les | last7=Brahams | first7=Diana | last8=Baum | first8=Michael | last9=Marks | first9=Vincent | last10=Isaacs | first10=Keith | last11=May | first11=James | title=Clothing naked quackery and legitimising pseudoscience | journal=BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.) | volume=343 | date=2011-09-20 | issn=1756-1833 | pmid=21937550 | doi=10.1136/bmj.d5960 | page=d5960| s2cid=19450377 }}</ref><ref name="Ernst 2011 p. d4370">{{cite journal | last=Ernst | first=Edzard | title=College of medicine or college of quackery? | journal=BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.) | volume=343 | date=2011-07-12 | issn=1756-1833 | pmid=21750062 | doi=10.1136/bmj.d4370 | page=d4370| s2cid=8061172 }}</ref>--> | |||

| ===Induction=== | |||

| Hypnosis is normally preceded by a "hypnotic induction" technique. Traditionally this was interpreted as a method of putting the subject into a "hypnotic trance"; however subsequent "nonstate" theorists have viewed it differently, as a means of heightening client expectation, defining their role, focusing attention, etc. There are an enormous variety of different induction techniques used in hypnotism. However, by far the most influential method was the original "eye-fixation" technique of Braid, also known as "Braidism". Many variations of the eye-fixation approach exist, including the induction used in the Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scale (SHSS), the most widely-used research tool in the field of hypnotism. Braid's original description of his induction is as follows:{{quotation| | |||

| '''James Braid's Original Eye-Fixation Hypnotic Induction Method'''<br /> | |||

| Take any bright object (I generally use my lancet case) between the thumb and fore and middle fingers of the left hand; hold it from about eight to fifteen inches from the eyes, at such position above the forehead as may be necessary to produce the greatest possible strain upon the eyes and eyelids, and enable the patient to maintain a steady fixed stare at the object. <br /><br />The patient must be made to understand that he is to keep the eyes steadily fixed on the object, and the mind riveted on the idea of that one object. It will be observed, that owing to the consensual adjustment of the eyes, the pupils will be at first contracted: they will shortly begin to dilate, and after they have done so to a considerable extent, and have assumed a wavy motion, if the fore and middle fingers of the right hand, extended and a little separated, are carried from the object towards the eyes, most probably the eyelids will close involuntarily, with a vibratory motion. If this is not the case, or the patient allows the eyeballs to move, desire him to begin anew, giving him to understand that he is to allow the eyelids to close when the fingers are again carried towards the eyes, but that the eyeballs must be kept fixed, in the same position, and the mind riveted to the one idea of the object held above the eyes. It will generally be found, that the eyelids close with a vibratory motion, or become spasmodically closed.<ref>Braid, ''Neurypnology'', 1843</ref>}}Braid himself later acknowledged that the hypnotic induction technique was not necessary in every case and subsequent researchers have generally found that on average it contributes less than previously expected to the effect of hypnotic suggestions (q.v., Barber, Spanos & Chaves, 1974). Many variations and alternatives to the original hypnotic induction techniques were subsequently developed. However, exactly 100 years after Braid introduced the method, another expert could still state: "It can be safely stated that nine out of ten hypnotic techniques call for reclining posture, muscular relaxation, and optical fixation followed by eye closure."<ref>White, Robert W. 'A preface to the theory of hypnotism', Journal of Abnormal & Social Psychology, 1941, 1, 498.</ref> | |||

| == Induction == | |||

| {{Main|Hypnotic induction}} | |||

| Hypnosis is normally preceded by a "hypnotic induction" technique. Traditionally, this was interpreted as a method of putting the subject into a "hypnotic trance"; however, subsequent "nonstate" theorists have viewed it differently, seeing it as a means of heightening client expectation, defining their role, focusing attention, etc. The induction techniques and methods are dependent on the depth of hypnotic trance level and for each stage of trance, the number of which in some sources ranges from 30 stages to 50 stages, there are different types of inductions.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Irawan |first1=Chandra |title=COMBINATION OF HYPNOSIS THERAPY AND RANGE OF MOTION EXERCISE ON UPPER-EXTREMITY MUSCLE STRENGTH IN PATIENTS WITH NON-HEMORRAGHIC STROKE |url=https://www.researchgate.net/figure/The-depth-of-hypnosis-influence-with-scores-and-objective-symptoms-based-on-The-Davis_tbl1_331217313 |website=researchgate.net |access-date=4 May 2022 |archive-date=4 May 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220504091654/https://www.researchgate.net/figure/The-depth-of-hypnosis-influence-with-scores-and-objective-symptoms-based-on-The-Davis_tbl1_331217313 |url-status=live }}</ref> There are several different induction techniques. One of the most influential methods was Braid's "eye-fixation" technique, also known as "Braidism". Many variations of the eye-fixation approach exist, including the induction used in the ] (SHSS), the most widely used research tool in the field of hypnotism.<ref name="Weitzenhoffer">{{cite book |last= Weitzenhoffer & Hilgard |title= Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scales, Forms A & B. |year= 1959 |publisher= Consulting Psychologists Press |location= Palo Alto, CA}}</ref> Braid's original description of his induction is as follows:{{blockquote|Take any bright object (e.g. a lancet case) between the thumb and fore and middle fingers of the left hand; hold it from about eight to fifteen inches from the eyes, at such position above the forehead as may be necessary to produce the greatest possible strain upon the eyes and eyelids, and enable the patient to maintain a steady fixed stare at the object.<br /><br />The patient must be made to understand that he is to keep the eyes steadily fixed on the object, and the mind riveted on the idea of that one object. It will be observed, that owing to the consensual adjustment of the eyes, the pupils will be at first contracted: They will shortly begin to dilate, and, after they have done so to a considerable extent, and have assumed a wavy motion, if the fore and middle fingers of the right hand, extended and a little separated, are carried from the object toward the eyes, most probably the eyelids will close involuntarily, with a vibratory motion. If this is not the case, or the patient allows the eyeballs to move, desire him to begin anew, giving him to understand that he is to allow the eyelids to close when the fingers are again carried towards the eyes, but that the eyeballs must be kept fixed, in the same position, and the mind riveted to the one idea of the object held above the eyes. In general, it will be found, that the eyelids close with a vibratory motion, or become spasmodically closed.<ref>Braid (1843), p. 27.</ref>}} | |||

| Braid later acknowledged that the hypnotic induction technique was not necessary in every case, and subsequent researchers have generally found that on average it contributes less than previously expected to the effect of hypnotic suggestions.<ref name="Barber, Spanos 1974"> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230702163311/https://books.google.com/books?id=fCRsAAAAMAAJ |date=2 July 2023 }} {{ISBN|0-08-017931-2}}.</ref> Variations and alternatives to the original hypnotic induction techniques were subsequently developed. However, this method is still considered authoritative.{{Citation needed|date=July 2016}} In 1941, Robert White wrote: "It can be safely stated that nine out of ten hypnotic techniques call for reclining posture, muscular relaxation, and optical fixation followed by eye closure."<ref>{{cite journal|year=1941|title=A preface to the theory of hypnotism|journal=Journal of Abnormal & Social Psychology|volume=36|issue=4|pages=477–505 (498)|doi=10.1037/h0053844|author=White, Robert W.}}</ref> | |||

| == Suggestion == | |||

| ===Suggestion=== | |||

| {{Main|Suggestion}} | {{Main|Suggestion}} | ||

| When ] first described hypnotism, he did not use the term "suggestion" but referred instead to the act of focusing the conscious mind of the subject upon a single dominant idea. Braid's main therapeutic strategy involved stimulating or reducing physiological functioning in different regions of the body. In his later works, however, Braid placed increasing emphasis upon the use of a variety of different verbal and non-verbal forms of suggestion, including the use of "waking suggestion" and self-hypnosis. Subsequently, ] shifted the emphasis from the physical state of hypnosis on to the psychological process of verbal suggestion |

When ] first described hypnotism, he did not use the term "suggestion" but referred instead to the act of focusing the conscious mind of the subject upon a single dominant idea. Braid's main therapeutic strategy involved stimulating or reducing physiological functioning in different regions of the body. In his later works, however, Braid placed increasing emphasis upon the use of a variety of different verbal and non-verbal forms of suggestion, including the use of "waking suggestion" and self-hypnosis. Subsequently, ] shifted the emphasis from the physical state of hypnosis on to the psychological process of verbal suggestion: | ||

| {{blockquote|text= | |||

| I define hypnotism as the induction of a peculiar psychical condition which increases the susceptibility to suggestion. Often, it is true, the sleep that may be induced facilitates suggestion, but it is not the necessary preliminary. It is suggestion that rules hypnotism. |

I define hypnotism as the induction of a peculiar psychical condition which increases the susceptibility to suggestion. Often, it is true, the sleep that may be induced facilitates suggestion, but it is not the necessary preliminary. It is suggestion that rules hypnotism.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=RVtNAQAAIAAJ|title=Hypnosis & Suggestion in Psychotherapy: A Treatise on the Nature and Uses of Hypnotism. Tr. from the 2d Rev. Ed|first=Hippolyte|last=Bernheim|date=11 July 1964|publisher=University Books|via=Google Books|access-date=11 October 2019|archive-date=2 July 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230702163308/https://books.google.com/books?id=RVtNAQAAIAAJ|url-status=live}}</ref> | ||

| }} | |||

| </blockquote> | |||

| Bernheim's conception of the primacy of verbal suggestion in hypnotism dominated the subject throughout the |

Bernheim's conception of the primacy of verbal suggestion in hypnotism dominated the subject throughout the 20th century, leading some authorities to declare him the father of modern hypnotism.<ref name="Weitzenhoffer, 2000"/> | ||

| Contemporary hypnotism |

Contemporary hypnotism uses a variety of suggestion forms including direct verbal suggestions, "indirect" verbal suggestions such as requests or insinuations, metaphors and other rhetorical figures of speech, and non-verbal suggestion in the form of mental imagery, voice tonality, and physical manipulation. A distinction is commonly made between suggestions delivered "permissively" and those delivered in a more "authoritarian" manner. Harvard hypnotherapist ] writes that most modern research suggestions are designed to bring about immediate responses, whereas hypnotherapeutic suggestions are usually post-hypnotic ones that are intended to trigger responses affecting behaviour for periods ranging from days to a lifetime in duration. The hypnotherapeutic ones are often repeated in multiple sessions before they achieve peak effectiveness.<ref>{{cite book|last=Barrett|first=Deirdre| name-list-style = vanc |title=The Pregnant Man: Cases from a Hypnotherapist's Couch|year=1998|publisher=Times Books}}</ref> | ||

| === |

=== Conscious and unconscious mind === | ||

| Some hypnotists |

Some hypnotists view suggestion as a form of communication that is directed primarily to the subject's conscious mind,<ref name="Rossi">{{cite journal |url=http://www.studiopsicologiamantova.it/psy/psicologia/miltonerickson/what-is-a-suggestion.pdf |title=What is a suggestion? The neuroscience of implicit processing heuristics in therapeutic hypnosis and psychotherapy |first1=Ernest L. |last1=Rossi |first2=Kathryn L. |last2=Rossi |name-list-style=vanc |date=April 2007 |journal=American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis |volume=49 |issue=4 |pages=267–81 |doi=10.1080/00029157.2007.10524504 |pmid=17444364 |s2cid=12202594 |access-date=24 April 2013 |archive-date=28 December 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131228151737/http://www.studiopsicologiamantova.it/psy/psicologia/miltonerickson/what-is-a-suggestion.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> whereas others view it as a means of communicating with the "]" or "]" mind.<ref name="Rossi"/><ref>{{cite web |url=http://bscw.rediris.es/pub/bscw.cgi/d4523426/Lovatt-Hypnosis_suggestion.pdf |title=Hypnosis and suggestion |last=Lovatt |first=William F. |name-list-style=vanc |publisher=Rider & Co |date=1933{{ndash}}34 |access-date=24 April 2013 |archive-date=4 March 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160304115910/http://bscw.rediris.es/pub/bscw.cgi/d4523426/Lovatt-Hypnosis_suggestion.pdf |url-status=dead}}</ref> These concepts were introduced into hypnotism at the end of the 19th century by ] and ]. Sigmund Freud's psychoanalytic theory describes conscious thoughts as being at the surface of the mind and unconscious processes as being deeper in the mind.<ref>Daniel L. Schacter; Daniel T. Gilbert; Daniel M. Wegner, ''Psychology'', 2009, 2011</ref> Braid, Bernheim, and other Victorian pioneers of hypnotism did not refer to the unconscious mind but saw hypnotic suggestions as being addressed to the subject's ''conscious'' mind. Indeed, Braid actually defines hypnotism as focused (conscious) attention upon a dominant idea (or suggestion). Different views regarding the nature of the mind have led to different conceptions of suggestion. Hypnotists who believe that responses are mediated primarily by an "unconscious mind", like ], make use of indirect suggestions such as metaphors or stories whose intended meaning may be concealed from the subject's conscious mind. The concept of ] depends upon this view of the mind. By contrast, hypnotists who believe that responses to suggestion are primarily mediated by the conscious mind, such as ] and ], have tended to make more use of direct verbal suggestions and instructions.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Spanos |first1=Nicholas P. |last2=Barber |first2=Theodore X. |date=1974 |title=Toward a convergence in hypnosis research. |url=http://doi.apa.org/getdoi.cfm?doi=10.1037/h0036795 |journal=American Psychologist |language=en |volume=29 |issue=7 |pages=500–511 |doi=10.1037/h0036795 |pmid=4416672 |issn=1935-990X |access-date=28 September 2022 |archive-date=2 July 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230702163814/https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037/h0036795 |url-status=live }}</ref> | ||

| === |

=== Ideo-dynamic reflex === | ||

| {{Main| |

{{Main|Ideomotor response}} | ||

| The first neuropsychological theory of hypnotic suggestion was introduced early |

The first neuropsychological theory of hypnotic suggestion was introduced early by James Braid who adopted his friend and colleague ] theory of the ] to account for the phenomenon of hypnotism. Carpenter had observed from close examination of everyday experience that, under certain circumstances, the mere idea of a muscular movement could be sufficient to produce a reflexive, or automatic, contraction or movement of the muscles involved, albeit in a very small degree. Braid extended Carpenter's theory to encompass the observation that a wide variety of bodily responses besides muscular movement can be thus affected, for example, the idea of sucking a lemon can automatically stimulate salivation, a secretory response. Braid, therefore, adopted the term "ideo-dynamic", meaning "by the power of an idea", to explain a broad range of "psycho-physiological" (mind–body) phenomena. Braid coined the term "mono-ideodynamic" to refer to the theory that hypnotism operates by concentrating attention on a single idea in order to amplify the ideo-dynamic reflex response. Variations of the basic ideo-motor, or ideo-dynamic, theory of suggestion have continued to exercise considerable influence over subsequent theories of hypnosis, including those of ], ], and Ernest Rossi.<ref name="Rossi"/> In Victorian psychology the word "idea" encompasses any mental representation, including mental imagery, memories, etc. | ||

| == Susceptibility == | |||

| ====Post-hypnotic suggestion==== | |||

| {{Main|Post-hypnotic suggestion}} | |||

| It has been alleged post-hypnotic suggestion can be used to change people's behaviour after emerging from hypnosis. One author wrote that "a person can act, some time later, on a suggestion seeded during the hypnotic session". A hypnotherapist told one of his patients, who was also a friend: 'When I touch you on the finger you will immediately be hypnotised.' Fourteen years later, at a dinner party, he touched him deliberately on the finger and his head fell back against the chair."<ref>Waterfield, R. (2003). ''Hidden Depths: The Story of Hypnosis''. pp. 36-37</ref> | |||

| ===Susceptibility=== | |||

| {{Main|Hypnotic susceptibility}} | {{Main|Hypnotic susceptibility}} | ||

| Braid made a rough distinction between different stages of hypnosis which he termed the first and second conscious stage of hypnotism;{{ |

Braid made a rough distinction between different stages of hypnosis, which he termed the first and second conscious stage of hypnotism;<ref name="auto1">{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Vs35STwQYQoC|title=The Discovery of Hypnosis: The Complete Writings of James Braid, the Father of Hypnotherapy|first=James|last=Braid|date=11 July 2008|publisher=UKCHH Ltd|isbn=9780956057006|via=Google Books|access-date=7 November 2015|archive-date=2 July 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230702162805/https://books.google.com/books?id=Vs35STwQYQoC|url-status=live}}</ref> he later replaced this with a distinction between "sub-hypnotic", "full hypnotic", and "hypnotic coma" stages.<ref name="auto1"/> ] made a similar distinction between stages which he named somnambulism, lethargy, and catalepsy. However, ] and Hippolyte Bernheim introduced more complex hypnotic "depth" scales based on a combination of behavioural, physiological, and subjective responses, some of which were due to direct suggestion and some of which were not. In the first few decades of the 20th century, these early clinical "depth" scales were superseded by more sophisticated "hypnotic susceptibility" scales based on experimental research. The most influential were the Davis–Husband and Friedlander–Sarbin scales developed in the 1930s. ] and ] developed the Stanford Scale of Hypnotic Susceptibility in 1959, consisting of 12 suggestion test items following a standardised hypnotic eye-fixation induction script, and this has become one of the most widely referenced research tools in the field of hypnosis. Soon after, in 1962, Ronald Shor and Emily Carota Orne developed a similar group scale called the Harvard Group Scale of Hypnotic Susceptibility (HGSHS). | ||

| Whereas the older "depth scales" tried to infer the level of "hypnotic trance" |

Whereas the older "depth scales" tried to infer the level of "hypnotic trance" from supposed observable signs such as spontaneous amnesia, most subsequent scales have measured the degree of observed or self-evaluated ''responsiveness'' to specific suggestion tests such as direct suggestions of arm rigidity (catalepsy). The Stanford, Harvard, HIP, and most other susceptibility scales convert numbers into an assessment of a person's susceptibility as "high", "medium", or "low". Approximately 80% of the population are medium, 10% are high, and 10% are low. There is some controversy as to whether this is distributed on a "normal" bell-shaped curve or whether it is bi-modal with a small "blip" of people at the high end.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Piccione C, Hilgard ER, Zimbardo PG | title = On the degree of stability of measured hypnotizability over a 25-year period | journal = Journal of Personality and Social Psychology | volume = 56 | issue = 2 | pages = 289–95 | date = February 1989 | pmid = 2926631 | doi = 10.1037/0022-3514.56.2.289 | citeseerx = 10.1.1.586.1971}}</ref> Hypnotisability scores are highly stable over a person's lifetime. Research by Deirdre Barrett has found that there are two distinct types of highly susceptible subjects, which she terms fantasisers and dissociaters. Fantasisers score high on absorption scales, find it easy to block out real-world stimuli without hypnosis, spend much time daydreaming, report imaginary companions as a child, and grew up with parents who encouraged imaginary play. Dissociaters often have a history of childhood abuse or other trauma, learned to escape into numbness, and to forget unpleasant events. Their association to "daydreaming" was often going blank rather than creating vividly recalled fantasies. Both score equally high on formal scales of hypnotic susceptibility.<ref>Barrett, Deirdre. Deep Trance Subjects: A Schema of Two Distinct Subgroups. in R. Kunzendorf (Ed.) Imagery: Recent Developments, NY: Plenum Press, 1991, pp. 101–12.</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Barrett D | title = Fantasizers and dissociaters: data on two distinct subgroups of deep trance subjects | journal = Psychological Reports | volume = 71 | issue = 3 Pt 1 | pages = 1011–14 | date = December 1992 | pmid = 1454907 | doi = 10.2466/pr0.1992.71.3.1011 | s2cid = 44878822}}</ref><ref>Barrett, Deirdre. Fantasizers and Dissociaters: Two types of High Hypnotizables, Two Imagery Styles. in R. Kuzendorf, N. Spanos, & B. Wallace (Eds.) Hypnosis and Imagination, NY: Baywood, 1996 {{ISBN|0-89503-139-6}}</ref> | ||

| Research by ] has found that there are two distinct types of highly susceptible subjects which she terms fantasizers and dissociaters. Fantasizers score high on absorption scales, find it easy to block out real-world stimuli without hypnosis, spend much time daydreaming, report imaginary companions as a child and grew up with parents who encouraged imaginary play. Dissociaters often have a history of childhood abuse or other trauma, learned to escape into numbness, and to forget unpleasant events. Their association to “daydreaming” was often going blank rather than vividly recalled fantasies. Both score equally high on formal scales of hypnotic susceptibility.<ref>Barrett, Deirdre. Deep Trance Subjects: A Schema of Two Distinct Subgroups. Chpt in R. Kunzendorf (Ed.) Imagery: Recent Developments, NY: Plenum Press, 1991, p. 101 112.</ref><ref>Barrett, Deirdre. Fantasizers and Dissociaters: An Empirically based schema of two types of deep trance subjects. Psychological Reports, 1992, 71, p. 1011-1014.</ref><ref>Barrett, Deirdre. Fantasizers and Dissociaters: Two types of High Hypnotizables, Two Imagery Styles. in R. Kuzendorf, N. Spanos, & B. Wallace (Eds.) Hypnosis and Imagination, NY: Baywood, 1996.</ref> | |||

| Individuals with ] have the highest hypnotisability of any ]al group, followed by those with ].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Spiegel D, Loewenstein RJ, Lewis-Fernández R, Sar V, Simeon D, Vermetten E, Cardeña E, Dell PF | title = Dissociative disorders in DSM-5 | journal = Depression and Anxiety | volume = 28 | issue = 9 | pages = 824–52 | date = September 2011 | pmid = 21910187 | doi = 10.1002/da.20874 | s2cid = 46518635 | url = http://dsm5.org/Documents/Anxiety,%20OC%20Spectrum,%20PTSD,%20and%20DD%20Group/PTSD%20and%20DD/Spiegel%20et%20al_Dissociative%20Disorders.pdf | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20130501231851/http://dsm5.org/Documents/Anxiety%2C%20OC%20Spectrum%2C%20PTSD%2C%20and%20DD%20Group/PTSD%20and%20DD/Spiegel%20et%20al_Dissociative%20Disorders.pdf | df = dmy-all | url-status = dead | archive-date = 1 May 2013}}</ref> | |||

| ==History== | |||

| {{Main|History of hypnosis}} | |||

| == |

== Applications == | ||

| There are numerous applications for hypnosis across multiple fields of interest, including medical/psychotherapeutic uses, military uses, self-improvement, and entertainment. The ] currently has no official stance on the medical use of hypnosis. | |||

| According to his writings, Braid began to hear reports concerning various Oriental ] soon after the release of his first publication on hypnotism, ''Neurypnology'' (1843). He first discussed some of these oriental practices in a series of articles entitled ''Magic, Mesmerism, Hypnotism, etc., Historically & Physiologically Considered''. He drew analogies between his own practice of hypnotism and various forms of Hindu yoga meditation and other ancient spiritual practices, especially those involving ] and apparent ]. Braid’s interest in these practices stems from his studies of the ], the “School of Religions”, an ancient Persian text describing a wide variety of Oriental religious rituals, beliefs, and practices. | |||

| Hypnosis has been used as a supplemental approach to ] since as early as 1949. Hypnosis was defined in relation to ]; where the words of the therapist were the stimuli and the hypnosis would be the conditioned response. Some traditional cognitive behavioral therapy methods were based in classical conditioning. It would include inducing a ] state and introducing a feared stimulus. One way of inducing the relaxed state was through hypnosis.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Chapman|first1=Robin|title=Clinical Use of Hypnosis in Cognitive Behavior Therapy: A Practitioner's Casebook|year=2005|publisher=Springer Publisher Company|page=6}}</ref> | |||

| <blockquote> | |||

| Last May , a gentleman residing in Edinburgh, personally unknown to me, who had long resided in India, favored me with a letter expressing his approbation of the views which I had published on the nature and causes of hypnotic and mesmeric phenomena. In corroboration of my views, he referred to what he had previously witnessed in oriental regions, and recommended me to look into the “Dabistan,” a book lately published, for additional proof to the same effect. On much recommendation I immediately sent for a copy of the “Dabistan”, in which I found many statements corroborative of the fact, that the eastern saints are all self-hypnotisers, adopting means essentially the same as those which I had recommended for similar purposes.<ref>Braid, J. , 1844-1845, vol. XI., pp. 203-204, 224-227, 270-273, 296-299, 399-400, 439-441.</ref> | |||

| </blockquote> | |||

| Hypnotism has also been used in ], ], education, ], and ].<ref name="André">André M. Weitzenbhoffer. ''The Practice of Hypnotism'' 2nd ed, Toronto, John Wiley & Son Inc., Chapter 16, pp. 583–87, 2000 {{ISBN|0-471-29790-9}}</ref> Hypnotism has also been employed by artists for creative purposes, most notably the surrealist circle of ] who employed hypnosis, ], and sketches for creative purposes. Hypnotic methods have been used to re-experience drug states<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Fogel S, Hoffer A | title = The use of hypnosis to interrupt and to reproduce an LSD-25 experience | journal = Journal of Clinical and Experimental Psychopathology & Quarterly Review of Psychiatry and Neurology | volume = 23 | pages = 11–16 | year = 1962 | pmid = 13893766}}</ref> and mystical experiences.<ref>{{cite journal| vauthors = Van Quekelberghe R, Göbel P, Hertweck E |year=1995|title=Simulation of near-death and out-of-body experiences under hypnosis|journal= Imagination, Cognition & Personality|volume= 14|issue=2|pages=151–64|doi=10.2190/gdfw-xlel-enql-5wq6|s2cid=145579925}}</ref><ref> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100129194407/http://counselinginoregon.com/mysticalexperience |date=29 January 2010}}. Counselinginoregon.com. Retrieved on 1 October 2011.</ref> Self-hypnosis is popularly used to ], alleviate stress and anxiety, promote ], and induce sleep hypnosis. Stage hypnosis can persuade people to perform unusual public feats.<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171201032613/http://www.stagehypnosisshow.co.uk/history-stage-hypnotist-stage-hypnosis-shows/ |date=1 December 2017}}. stagehypnosisshow.co.uk. Retrieved on 23 January 2015.</ref> | |||

| Although he rejected the transcendental/metaphysical interpretation given to these phenomena outright, Braid accepted that these accounts of Oriental practices supported his view that the effects of hypnotism could be produced in solitude, without the presence of any other person (as he had already proved to his own satisfaction with the experiments he had conducted in November 1841); and he saw correlations between many of the "metaphysical" Oriental practices and his own "rational" neuro-hypnotism, and totally rejected all of the fluid theories and magnetic practices of the mesmerists. As he later wrote: | |||

| Some people have drawn analogies between certain aspects of hypnotism and areas such as ], religious hysteria, and ritual trances in preliterate tribal cultures.<ref name="Wier">{{cite book|last=Wier|first=Dennis R| name-list-style = vanc |year=1996|title=Trance: from magic to technology|publisher=TransMedia|location=Ann Arbor, MI|isbn=978-1-888428-38-4}}{{Page needed|date=September 2010}}</ref> | |||

| <blockquote> | |||

| In as much as patients can throw themselves into the nervous sleep, and manifest all the usual phenomena of Mesmerism, through their own unaided efforts, as I have so repeatedly proved by causing them to maintain a steady fixed gaze at any point, concentrating their whole mental energies on the idea of the object looked at; or that the same may arise by the patient looking at the point of his own finger, or as the Magi of Persia and Yogi of India have practised for the last 2,400 years, for religious purposes, throwing themselves into their ecstatic trances by each maintaining a steady fixed gaze at the tip of his own nose; it is obvious that there is no need for an exoteric influence to produce the phenomena of Mesmerism. The great object in all these processes is to induce a habit of abstraction or concentration of attention, in which the subject is entirely absorbed with one idea, or train of ideas, whilst he is unconscious of, or indifferently conscious to, every other object, purpose, or action.<ref>Braid, J. , The Edinburgh Medical and Surgical Journal, Volume Sixty Sixth 1846, Pages 286-311.</ref> | |||

| </blockquote> | |||

| === |

=== Hypnotherapy === | ||

| {{Main|Hypnotherapy}} | |||

| ] (1734–1815) believed that there was a magnetic force or "fluid" within the universe which influenced the health of the human body. He experimented with magnets to influence this field and so cause healing. By around 1774 he had concluded that the same effects could be created by passing the hands, at a distance, in front of the subject's body, referred to as making "Mesmeric passes." The word mesmerize originates from the name of Franz Mesmer, and was intentionally used to separate its users from the various "fluid" and "magnetic" theories embedded within the label "magnetism". | |||

| {{POV section|date=January 2019}} | |||

| Hypnotherapy is a use of hypnosis in psychotherapy.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://umm.edu/health/medical/altmed/treatment/hypnotherapy|title=Hypnotherapy | University of Maryland Medical Center|date=27 June 2013|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130627092448/https://umm.edu/health/medical/altmed/treatment/hypnotherapy |archive-date=27 June 2013 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.asch.com.au/general-public/faq#6|title=Australian Society of Clinical Hypnotherapists|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160126162841/https://www.asch.com.au/general-public/faq#6|archive-date=26 January 2016}}</ref> It is used by licensed physicians, psychologists, and others. Physicians and psychologists may use hypnosis to treat depression, anxiety, ]s, ]s, ], ] and ],<ref name="PregnantMan">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=O_cEAAAACAAJ|title=The Pregnant Man: Tales from a Hypnotherapist's Couch|author=Deirdre Barrett|publisher=NY: Times Books/Random House|edition=1998/hardback, 1999 paper|isbn=978-0-8129-2905-8|date=1998|access-date=7 November 2015|archive-date=2 July 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230702163828/https://books.google.com/books?id=O_cEAAAACAAJ|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author=Assen Alladin|title=Cognitive hypnotherapy: an integrated approach to the treatment of emotional disorders|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=B0hMPgAACAAJ|access-date=30 October 2011|year=2008|publisher=J. Wiley|isbn=978-0-470-03251-0|archive-date=2 July 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230702163814/https://books.google.com/books?id=B0hMPgAACAAJ|url-status=live}}</ref> while certified hypnotherapists who are not physicians or psychologists often treat smoking and weight management. Hypnotherapy was historically used in psychiatric and legal settings to enhance the recall of repressed or degraded memories, but this application of the technique has declined as scientific evidence accumulated that hypnotherapy can increase confidence in ].<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Lynn |first1=Steven Jay |title=Myths and misconceptions about hypnosis and suggestion: Separating fact and fiction |journal=Applied Cognitive Psychology |date=11 August 2020 |volume=34 |issue=6 |page=1260 |doi=10.1002/acp.3730 |s2cid=225412389 |url=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/acp.3730 |access-date=27 September 2022 |archive-date=27 September 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220927160328/https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/acp.3730 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Hypnotherapy is viewed as a helpful adjunct by proponents, having additive effects when treating psychological disorders, such as these, along with scientifically proven ]. The effectiveness of hypnotherapy has not yet been accurately assessed,<ref>{{cite journal | last1=Flammer | first1=Erich | last2=Bongartz | first2=Walter |name-list-style=vanc | title=On the efficacy of hypnosis: a meta-analytic study | journal=Contemporary Hypnosis | publisher=Wiley | volume=20 | issue=4 | year=2006 | issn=0960-5290 | doi=10.1002/ch.277 | pages=179–197 |url=http://www.hypnose-kikh.de/content/Metaanalyse-Flammer-2004.pdf |language=en |access-date=11 January 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160222004606/http://www.hypnose-kikh.de/content/Metaanalyse-Flammer-2004.pdf |archive-date=22 February 2016 |url-status=dead}}</ref> and, due to the lack of evidence indicating any level of efficiency,<ref name="Barnes, J. 2019">{{cite journal | last1=Barnes | first1=Joanne | last2=McRobbie | first2=Hayden | last3=Dong | first3=Christine Y | last4=Walker | first4=Natalie | last5=Hartmann-Boyce | first5=Jamie |name-list-style=vanc | title=Hypnotherapy for smoking cessation | journal=Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | publisher=Wiley | volume=2019 | issue=6 | date=2019-06-14 | pages=CD001008 | issn=1465-1858 | doi=10.1002/14651858.cd001008.pub3 | doi-access=free | pmid=31198991 | pmc=6568235 }}</ref> it is regarded as a type of ] by numerous reputable medical organisations, such as the ].<ref>{{cite web| url = https://www.healthcareers.nhs.uk/explore-roles/wider-healthcare-team/roles-wider-healthcare-team/clinical-support-staff/complementary-and-alternative-medicine-cam| url-status = dead| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20180626164403/https://www.healthcareers.nhs.uk/explore-roles/wider-healthcare-team/roles-wider-healthcare-team/clinical-support-staff/complementary-and-alternative-medicine-cam| archive-date = 26 June 2018| title = Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) {{!}} Health Careers}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url = https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/hypnotherapy/|title = Hypnotherapy|date = 19 January 2018|access-date = 10 March 2019|archive-date = 11 August 2021|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20210811220950/https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/hypnotherapy/|url-status = live}}</ref> | |||

| In 1784, at the request of ], a Board of Inquiry started to investigate whether | |||

| Animal Magnetism existed. Three of the board members include a founding father of modern chemistry ], ] and an expert in pain control ]. They also investigated the practices of a disaffected student of Mesmer, one Charles d'Eslon (1750–1786), and despite the fact that they accepted that Mesmer's results were valid, their ]-controlled experiments following d'Eslon's practices convinced them that Mesmerism's were most likely due to belief and imagination rather than to any sort of invisible energy ("animal magnetism") transmitted from the body of the Mesmerist. | |||

| Preliminary research has expressed brief hypnosis interventions as possibly being a useful tool for managing painful HIV-DSP because of its history of usefulness in ], its long-term effectiveness of brief interventions, the ability to teach self-hypnosis to patients, the cost-effectiveness of the intervention, and the advantage of using such an intervention as opposed to the use of pharmaceutical drugs.<ref name="Lynn SJ 2015"/> | |||

| In writing the majority opinion, Franklin said, "This fellow Mesmer is not flowing anything from his hands that I can see. Therefore, this mesmerism must be a fraud." Mesmer left Paris and went back to Vienna to practise mesmerism. | |||

| Modern hypnotherapy has been used, with varying success, in a variety of forms, such as: | |||

| ===James Braid=== | |||

| {{div col|colwidth=30em}} | |||

| ] | |||

| * ]s<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Kraft T, Kraft D |year=2005 |title=Covert sensitization revisited: Six case studies |url=http://www.londonpsychotherapy.co.uk/pdf/1.pdf |journal=Contemporary Hypnosis |volume=22 |issue=4 |pages=202–09 |doi=10.1002/ch.10 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120119123828/http://www.londonpsychotherapy.co.uk/pdf/1.pdf |archive-date=19 January 2012}}</ref><ref name="Elkins">{{cite journal | vauthors = Elkins GR, Rajab MH | title = Clinical hypnosis for smoking cessation: preliminary results of a three-session intervention | journal = The International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis | volume = 52 | issue = 1 | pages = 73–81 | date = January 2004 | pmid = 14768970 | doi = 10.1076/iceh.52.1.73.23921 | s2cid = 6065271}}</ref> | |||

| {{Main|James Braid (surgeon)}} | |||

| * ] (or "hypnoanalysis") | |||

| Following the French committee's findings, in his ''Elements of the Philosophy of the Human Mind'' (1827), ], an influential academic philosopher of the "]", encouraged physicians to salvage elements of Mesmerism by replacing the supernatural theory of "animal magnetism" with a new interpretation based upon "common sense" laws of ] and ]. Braid quotes the following passage from Stewart:<ref>Braid, J. ''Magic, Witchcraft, etc.'', 1852: 41-42.</ref> | |||

| * Cognitive-behavioural hypnotherapy, or clinical hypnosis combined with elements of cognitive behavioural therapy<ref name="Robertson_2012">{{cite book| author=Robertson, D| title=The Practice of Cognitive-Behavioural Hypnotherapy: A Manual for Evidence-Based Clinical Hypnosis| year=2012| publisher=Karnac| location=London| isbn=978-1-85575-530-7| url=https://books.google.com/books?id=um6_7kEszusC| access-date=7 November 2015| archive-date=2 July 2023| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230702163310/https://books.google.com/books?id=um6_7kEszusC| url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| * ] | |||

| * Fears and ]<ref>{{cite journal |title=Hypnosis with a blind 55-year-old female with dental phobia requiring periodontal treatment and extraction | vauthors = Gow MA |year=2006 |journal=Contemporary Hypnosis |volume=23 |pages=92–100 |issue=2 |doi=10.1002/ch.313}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |url=http://www.lcch.co.uk/hypnosisarticles/case_phobia.htm |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20050629025402/http://www.lcch.co.uk/hypnosisarticles/case_phobia.htm |url-status=dead |archive-date=29 June 2005 | vauthors = Nicholson J |title=Hypnotherapy – Case History – Phobia |journal=London College of Clinical Hypnosis}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |url=http://www.stichtingemetofobie.nl/pdf/a_vomiting_phobia_overcome_by_one_session_of_flooding_with_hypnosis.pdf |vauthors=Wijesnghe B |year=1974 |title=A vomiting phobia overcome by one session of flooding with hypnosis |journal=Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry |volume=5 |pages=169–70 |doi=10.1016/0005-7916(74)90107-4 |issue=2 |access-date=5 May 2013 |archive-date=8 March 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210308134532/http://www.stichtingemetofobie.nl/pdf/a_vomiting_phobia_overcome_by_one_session_of_flooding_with_hypnosis.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Deyoub PL, Epstein SJ | title = Short-term hypnotherapy for the treatment of flight phobia: a case report | journal = The American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis | volume = 19 | issue = 4 | pages = 251–54 | date = April 1977 | pmid = 879063 | doi = 10.1080/00029157.1977.10403885}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |url=http://www.thefreelibrary.com/Hypnosis+in+the+treatment+of+social+phobia.-a0229529946 |title=Hypnosis in the treatment of social phobia |last=Rogers |first=Janet |name-list-style=vanc |date=May 2008 |journal=Australian Journal of Clinical & Experimental Hypnosis |volume=36 |pages=64–68 |issue=1 |access-date=5 May 2013 |archive-date=30 April 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210430213739/https://www.thefreelibrary.com/Hypnosis+in+the+treatment+of+social+phobia.-a0229529946 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| * Habit control<ref name="Mayo">{{cite web|url=http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/hypnosis/SA00084 |title=Hypnosis. Another way to manage pain, kick bad habits |publisher=mayoclinic.com |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20091204153926/http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/hypnosis/sa00084 |archive-date=4 December 2009}}</ref><ref name="Anbar">{{cite journal | vauthors = Anbar RD | title = Childhood habit cough treated with consultation by telephone: a case report | journal = Cough | volume = 5 | issue = 2 | pages = 2 | date = January 2009 | pmid = 19159469 | pmc = 2632985 | doi = 10.1186/1745-9974-5-2 | citeseerx = 10.1.1.358.6608 | doi-access = free }}</ref><ref name="McNeilly">{{cite journal | vauthors = McNeilly R | title = Solution oriented hypnosis. An effective approach in medical practice | journal = Australian Family Physician | volume = 23 | issue = 9 | pages = 1744–46 | date = September 1994 | pmid = 7980173}}</ref> | |||

| * Pain management<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210731212842/https://www.webmd.com/pain-management/hypnosis-meditation-and-relaxation-for-pain-treatment |date=31 July 2021 }}. Webmd.com. Retrieved on 1 October 2011.</ref><ref name="Dahlgren">{{cite journal | vauthors = Dahlgren LA, Kurtz RM, Strube MJ, Malone MD | title = Differential effects of hypnotic suggestion on multiple dimensions of pain | journal = Journal of Pain and Symptom Management | volume = 10 | issue = 6 | pages = 464–70 | date = August 1995 | pmid = 7561229 | doi = 10.1016/0885-3924(95)00055-4 | doi-access = free}}</ref><ref name="Patterson1">{{cite journal | vauthors = Patterson DR, Ptacek JT | title = Baseline pain as a moderator of hypnotic analgesia for burn injury treatment | journal = Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology | volume = 65 | issue = 1 | pages = 60–67 | date = February 1997 | pmid = 9103735 | doi = 10.1037/0022-006X.65.1.60}}</ref><ref name="Barrett2004">{{cite web |url=https://www.apa.org/research/action/hypnosis |title=Hypnosis for the Relief and Control of Pain |author=American Psychological Association |date=2 July 2004 |publisher=American Psychological Association |access-date=28 September 2020 |archive-date=25 July 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210725212840/https://www.apa.org/research/action/hypnosis |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| * Psychotherapy<ref>Barrett, Deirdre. . ''Psychology Today''. Jan/Feb 2001 {{webarchive |url=https://archive.today/20071107103604/http://psychologytoday.com/articles/pto-20010101-000034.html |date=7 November 2007}}</ref> | |||

| * Relaxation<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Vickers A, Zollman C | title = ABC of complementary medicine. Hypnosis and relaxation therapies | journal = BMJ | volume = 319 | issue = 7221 | pages = 1346–49 | date = November 1999 | pmid = 10567143 | pmc = 1117083 | doi = 10.1136/bmj.319.7221.1346}}</ref> | |||

| * Reduce patient behavior (e.g., scratching) that hinders the treatment of skin disease<ref>Shenefelt, Philip D. {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210430185238/https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/466140 |date=30 April 2021 }}. medscape.com. 6 January 2004</ref> | |||

| * Soothing anxious surgical patients | |||

| * Sports performance<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210224122733/http://www.awss.com/sport02.htm |date=24 February 2021 }}. AWSS.com</ref><ref>{{cite journal |url=http://www.zoneofexcellence.ca/Journal/Issue06/Hypnosis.pdf |title=The effects of hypnosis on flow-states and performance |vauthors=Pates J, Palmi J |year=2002 |journal=Journal of Excellence |volume=6 |pages=48–461 |access-date=5 May 2013 |archive-date=7 March 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210307205223/http://www.zoneofexcellence.ca/Journal/Issue06/Hypnosis.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| * Weight loss<ref name="ReferenceA">{{cite journal | vauthors = Kirsch I | title = Hypnotic enhancement of cognitive-behavioral weight loss treatments – another meta-reanalysis | journal = Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology | volume = 64 | issue = 3 | pages = 517–19 | date = June 1996 | pmid = 8698945 | doi = 10.1037/0022-006X.64.3.517 | s2cid = 18091380 }}</ref><ref name="Bolocofsky">{{cite journal | vauthors = Bolocofsky DN, Spinler D, Coulthard-Morris L | title = Effectiveness of hypnosis as an adjunct to behavioral weight management | journal = Journal of Clinical Psychology | volume = 41 | issue = 1 | pages = 35–41 | date = January 1985 | pmid = 3973038 | doi = 10.1002/1097-4679(198501)41:1<35::AID-JCLP2270410107>3.0.CO;2-Z | url = http://www.hypnoprogram.com/documents/Three_Studies_WL_Hypnosis.pdf | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20131208195457/http://www.hypnoprogram.com/documents/Three_Studies_WL_Hypnosis.pdf | url-status = dead | archive-date = 8 December 2013}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Cochrane G, Friesen J | title = Hypnotherapy in weight loss treatment | journal = Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology | volume = 54 | issue = 4 | pages = 489–92 | date = August 1986 | pmid = 3745601 | doi = 10.1037/0022-006X.54.4.489 | url = http://www.hypnoprogram.com/documents/Three_Studies_WL_Hypnosis.pdf | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20131208195457/http://www.hypnoprogram.com/documents/Three_Studies_WL_Hypnosis.pdf | url-status = dead | archive-date = 8 December 2013}}</ref> | |||

| {{div col end}} | |||

| In a January 2001 article in '']'',<ref>{{cite magazine |url=http://www.psychologytoday.com/articles/200101/the-power-hypnosis |title=The Power of Hypnosis |first=Deirdre |last=Barrett |magazine=Psychology Today |issue=Jan/Feb |year=2001}}</ref> Harvard psychologist ] wrote: | |||

| {{blockquote|text=A hypnotic trance is not therapeutic in and of itself, but specific suggestions and images fed to clients in a trance can profoundly alter their behavior. As they rehearse the new ways they want to think and feel, they lay the groundwork for changes in their future actions... }} Barrett described specific ways this is operationalised for habit change and amelioration of phobias. In her 1998 book of hypnotherapy case studies,<ref name="PregnantMan"/> she reviews the clinical research on hypnosis with dissociative disorders, smoking cessation, and insomnia, and describes successful treatments of these complaints. | |||

| In a July 2001 article for '']'' titled "The Truth and the Hype of Hypnosis", Michael Nash wrote that, "using hypnosis, scientists have temporarily created hallucinations, compulsions, certain types of memory loss, false memories, and delusions in the laboratory so that these phenomena can be studied in a controlled environment."<ref name="Nash"/> | |||

| <blockquote> | |||

| It appears to me, that the general conclusions established by Mesmer’s practice, with respect to the physical effects of the principle of imagination are incomparably more curious than if he had actually demonstrated the existence of his boasted science : nor can I see any good reason why a physician, who admits the efficacy of the moral agents employed by Mesmer, should, in the exercise of his profession, scruple to copy whatever processes are necessary for subjecting them to his command, any more than that he should hesitate about employing a new physical agent, such as electricity or galvanism.<ref>Stewart, D. ''Elements of the Philosophy of the Human Mind'', 1827: 147</ref> | |||

| </blockquote> | |||

| ==== Menopause ==== | |||

| In Braid's day, the ] provided the dominant theories of academic psychology and Braid refers to other philosophers within this tradition throughout his writings. Braid therefore revised the theory and practice of Mesmerism and developed his own method of "hypnotism" as a more rational and "common sense" alternative. | |||

| There is evidence supporting the use of hypnotherapy in the treatment of ] related symptoms, including ]es.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Hickey|first1=Martha|last2=Szabo|first2=Rebecca A.|last3=Hunter|first3=Myra S.|date=2017-11-23|title=Non-hormonal treatments for menopausal symptoms|url=https://www.bmj.com/content/359/bmj.j5101|journal=BMJ|language=en|volume=359|pages=j5101|doi=10.1136/bmj.j5101|issn=0959-8138|pmid=29170264|s2cid=46856968|access-date=7 September 2021|archive-date=7 September 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210907105558/https://www.bmj.com/content/359/bmj.j5101|url-status=live}}</ref> The ] recommends hypnotherapy for the nonhormonal management of menopause-associated ] symptoms, giving it the highest level of evidence.<ref name="auto"/> | |||

| ==== Irritable bowel syndrome ==== | |||

| <blockquote> | |||