| Revision as of 03:14, 29 September 2010 edit99.172.15.148 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 23:43, 5 January 2025 edit undoMarginataen (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users4,488 edits moved an image rightTag: Visual edit | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

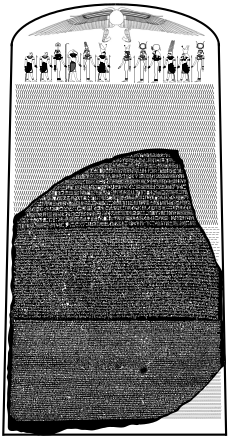

| {{Short description|Egyptian stele with three versions of a 196 BC decree}} | |||

| {{Other uses}} | |||

| {{About|the stone itself|its text|Rosetta Stone decree|other uses}} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=July 2022}}{{Use British English|date=August 2016}} | |||

| {{Infobox artifact | |||

| | name = Rosetta Stone | |||

| | image = Rosetta Stone.JPG | |||

| | image_size = 280px | |||

| | image_caption = The Rosetta Stone on display<br>in the ], London | |||

| | material = ] | |||

| | size = {{convert|1,123|×|757|×|284|mm|abbr=on}} | |||

| | writing = Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs, Demotic script, and Greek script | |||

| | created = 196 BC | |||

| | discovered_date = 1799 | |||

| | discovered_place = near ], ], ] | |||

| | discovered_by = ] | |||

| | location = ] | |||

| }} | |||

| The '''Rosetta Stone''' is a |

The '''Rosetta Stone''' is a ] of ] inscribed with three versions of a ] during the ] of ], on behalf of King ]. The top and middle texts are in ] using ] and ] scripts, respectively, while the bottom is in ]. The decree has only minor differences across the three versions, making the Rosetta Stone key to ]. | ||

| The stone was carved during the ] and is believed to have originally been displayed within a temple, possibly at ]. It was probably moved in late antiquity or during the ], and was eventually used as building material in the construction of ] near the town of Rashid (]) in the ]. It was found there in July 1799 by French officer ] during the Napoleonic ]. It was the first Ancient Egyptian bilingual text recovered in modern times, and it aroused widespread public interest with its potential to decipher this previously untranslated hieroglyphic script. Lithographic copies and plaster casts soon began circulating among European museums and scholars. When the British defeated the French, they took the stone to London under the terms of the ] in 1801. Since 1802, it has been on public display at the ] almost continuously and it is the most visited object there. | |||

| Study of the decree was already underway when the first complete translation of the Greek text was published in 1803. ] announced the ] of the Egyptian scripts in Paris in 1822; it took longer still before scholars were able to read Ancient Egyptian inscriptions and literature confidently. Major advances in the decoding were recognition that the stone offered three versions of the same text (1799); that the Demotic text used phonetic characters to spell foreign names (1802); that the hieroglyphic text did so as well, and had pervasive similarities to the Demotic (1814); and that phonetic characters were also used to spell native Egyptian words (1822–1824). | |||

| Ever since its rediscovery, the stone has been the focus of nationalist rivalries, including its transfer from French to British possession during the ], the long-running dispute over the relative value of Young's and Champollion's contributions to the decipherment, and since 2003, the demand for the stone's return to Egypt. | |||

| Three other fragmentary copies of the same decree were discovered later, and several similar Egyptian ] are now known, including three slightly earlier ]: the Decree of Alexandria in 243 BC, the ] in 238 BC, and the ], c. 218 BC. Though the Rosetta Stone is now known to not be unique, it was the essential key to the modern understanding of ancient Egyptian literature and civilisation. The term "Rosetta Stone" is now used to refer to the essential clue to a new field of knowledge. | |||

| Study of the decree was already under way as the first full translation of the Greek text appeared in 1803. It was 20 years, however, before the decipherment of the Egyptian texts was announced by ] in Paris in 1822; it took longer still before scholars were able to read other ancient Egyptian inscriptions and ] confidently. Major advances in the decoding were: recognition that the stone offered three versions of the same text (1799); that the demotic text used phonetic characters to spell foreign names (1802); that the hieroglyphic text did so as well, and had pervasive similarities to the demotic (], 1814); and that, in addition to being used for foreign names, phonetic characters were also used to spell native Egyptian words (Champollion, 1822–1824). | |||

| Two other fragmentary copies of the same decree were discovered later, and several similar Egyptian bilingual or trilingual inscriptions are now known, including two slightly earlier ] (the ] in 238 BC, and the ], ca. 218 BC). The Rosetta Stone is therefore no longer unique, but it was the essential key to modern understanding of ] and ]. The term ''Rosetta Stone'' is now used in other contexts as the name for the essential clue to a new field of knowledge. | |||

| ==Description== | ==Description== | ||

| The Rosetta Stone is listed as "a stone of black ], bearing three inscriptions ... found at Rosetta" |

The Rosetta Stone is listed as "a stone of black ], bearing three inscriptions ... found at Rosetta" in a contemporary catalogue of the artefacts discovered by the French expedition and surrendered to British troops in 1801.<ref>] pp. 111–113</ref> At some period after its arrival in London, the inscriptions were coloured in white ] to make them more legible, and the remaining surface was covered with a layer of ] designed to protect it from visitors' fingers.<ref name="Cracking23">] p. 23</ref> This gave a dark colour to the stone that led to its mistaken identification as ].<ref>] pp. 113–114</ref> These additions were removed when the stone was cleaned in 1999, revealing the original dark grey tint of the rock, the sparkle of its crystalline structure, and a pink ] running across the top left corner.<ref>] pp. 128–132</ref> Comparisons with the ] of Egyptian rock samples showed a close resemblance to rock from a small granodiorite quarry at ] on the west bank of the ], west of ] in the region of ]; the pink vein is typical of granodiorite from this region.<ref name="MiddletonKlemm207">] pp. 207–208</ref> | ||

| The Rosetta Stone is |

The Rosetta Stone is {{Convert|1123|mm|ftin|0}} high at its highest point, {{convert|abbr=on|757|mm|ftin}} wide, and {{convert|abbr=on|284|mm|ftin|0}} thick. It weighs approximately {{Convert|760|kg}}.<ref name="British Museum">]</ref> It bears three inscriptions: the top register in Ancient Egyptian ]s, the second in the Egyptian ] script, and the third in ].<ref name="Ray3">] p. 3</ref> These three scripts are not three different languages, as is commonly misunderstood.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Solly |first=Meilan |date=September 27, 2022 |title=Two Hundred Years Ago, the Rosetta Stone Unlocked the Secrets of Ancient Egypt |url=https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/rosetta-stone-hieroglyphs-champollion-decipherment-egypt-180980834/ |access-date=June 24, 2024 |website=]}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Sanguineti |first=Vincenzo R |title=The Rosetta Stone of the Human Mind: Three Languages to Integrate Neurobiology and Psychology |publisher=] |year=2022 |isbn=978-3-030-86414-9 |edition=2nd |location=Philadelphia |pages=xi |doi=10.1007/978-3-030-86415-6}}</ref> The front surface is polished and the inscriptions lightly ] on it; the sides of the stone are smoothed, but the back is only roughly worked, presumably because it would have not been visible when the stele was erected.<ref name="MiddletonKlemm207"/><ref name="Cracking28">] p. 28</ref> | ||

| ===Original stele=== | ===Original stele=== | ||

| ] | ]]] | ||

| The Rosetta Stone is a fragment of a larger stele. No additional fragments were found in later searches of the Rosetta site.<ref name="Cracking20">] p. 20</ref> Owing to its damaged state, none of the three texts is absolutely complete. The top register composed of Egyptian hieroglyphs suffered the most damage. Only the last 14 lines of the hieroglyphic text can be seen; all of them are broken on the right side, and 12 of them on the left. The following register of demotic text has survived best: it has 32 lines, of which the first 14 are slightly damaged on the right side. The final register of Greek text contains 54 lines, of which the first 27 survive in full; the rest are increasingly fragmentary due to a diagonal break at the bottom right of the stone.<ref name="Budgea2">] pp. 2–3</ref> | |||

| The Rosetta Stone is a fragment of a larger stele. No additional fragments were found in later searches of the Rosetta site.<ref name="Cracking20">] p. 20</ref> Owing to its damaged state, none of the three texts is complete. The top register, composed of Egyptian hieroglyphs, suffered the most damage. Only the last 14 lines of the hieroglyphic text can be seen; all of them are broken on the right side, and 12 of them on the left. Below it, the middle register of demotic text has survived best; it has 32 lines, of which the first 14 are slightly damaged on the right side. The bottom register of Greek text contains 54 lines, of which the first 27 survive in full; the rest are increasingly fragmentary due to a diagonal break at the bottom right of the stone.<ref name="Budgea2">] pp. 2–3</ref> | |||

| The full length of the hieroglyphic text and the total size of the original stele, of which the Rosetta Stone is a fragment, can be estimated based on comparable |

<div>The full length of the hieroglyphic text and the total size of the original stele, of which the Rosetta Stone is a fragment, can be estimated based on comparable steles that have survived, including other copies of the same order. The slightly earlier ], erected in 238 BC during the reign of ], is {{convert|2190|mm|ft|disp=x| high (|)}} and {{convert|abbr=on|820|mm}} wide, and contains 36 lines of hieroglyphic text, 73 of demotic text, and 74 of Greek. The texts are of similar length.<ref name="Mummy106">] p. 106</ref> From such comparisons, it can be estimated that an additional 14 or 15 lines of hieroglyphic inscription are missing from the top register of the Rosetta Stone, amounting to another {{Convert|300|mm}}.<ref name="Mummy109">] p. 109</ref> In addition to the inscriptions, there would probably have been a scene depicting the king being presented to the gods, topped with a winged disc, as on the Canopus Stele. These parallels, and a hieroglyphic sign for "stela" on the stone itself (see ]), | ||

| :<hiero>O26</hiero> | |||

| suggest that it originally had a rounded top.<ref name="Ray3"/><ref name="Cracking26">] p. 26</ref> The height of the original stele is estimated to have been about {{Convert|149|cm|ftin}}.<ref name="Cracking26"/></div> | |||

| ==Memphis decree and its context== | ==Memphis decree and its context== | ||

| {{Main article|Rosetta Stone decree}} | |||

| The stele was erected after the ] of King ], and was inscribed with a decree that established the divine cult of the new ruler.<ref name="Cracking25">] p. 25</ref> The decree was issued by a congress of priests who gathered at ]. The date is given as "4 ]" in the ] and "18 ]" in the ], which corresponds to March 27, 196 BC. The year is stated as the ninth year of Ptolemy V's reign (equated with 197/196 BC), and it is confirmed by naming four priests who officiated in that same year: ] was priest of the divine cults of ] and the five ] down to Ptolemy V himself; his three colleagues, named in turn in the inscription, led the worship of ] (wife of ]), ] (wife and sister of ]) and ], mother of Ptolemy V.<ref>] pp. 20–21</ref> However, a second date is also given in the Greek and hieroglyphic texts, corresponding to {{Nowrap|27 November 197 BC}}, the official anniversary of Ptolemy's coronation.<ref name="Cracking29">] p. 29</ref> The inscription in demotic conflicts with this, listing consecutive days in March for the decree and the anniversary;<ref name="Cracking29"/> although it is uncertain why such discrepancies exist, it is clear that the decree was issued in 196 BC and that it was designed to re-establish the rule of the Ptolemaic kings over Egypt.<ref name="ShawNicholson 247">] p. 247</ref> | |||

| The stele was erected after the ] of King ] and was inscribed with a decree that established the divine cult of the new ruler.<ref name="Cracking25">] p. 25</ref> The decree was issued by a congress of priests who gathered at ]. The date is given as "4 Xandikos" in the ] and "18 ]" in the ], which corresponds to {{Nowrap|27 March}} {{Nowrap|196 BC}}. The year is stated as the ninth year of Ptolemy V's reign (equated with 197/196 BC), which is confirmed by naming four priests who officiated in that year: ] was priest of the divine cults of ] and the five ] down to Ptolemy V himself; the other three priests named in turn in the inscription are those who led the worship of ] (wife of ]), ] (wife and sister of ]), and ], mother of Ptolemy V.<ref>] pp. 20–21</ref> However, a second date is also given in the Greek and hieroglyphic texts, corresponding to {{Nowrap|27 November 197 BC}}, the official anniversary of Ptolemy's coronation.<ref name="Cracking29">] p. 29</ref> The demotic text conflicts with this, listing consecutive days in March for the decree and the anniversary.<ref name="Cracking29"/> It is uncertain why this discrepancy exists, but it is clear that the decree was issued in 196 BC and that it was designed to re-establish the rule of the Ptolemaic kings over Egypt.<ref name="ShawNicholson 247">] p. 247</ref> | |||

| The decree was issued during a turbulent period in Egyptian history. Ptolemy |

The decree was issued during a turbulent period in Egyptian history. Ptolemy V Epiphanes, the son of ] and his wife and sister Arsinoe, reigned from 204 to 181 BC. He had become ruler at the age of five after the sudden death of both of his parents, who were murdered in a conspiracy that involved Ptolemy IV's mistress ], according to contemporary sources. The conspirators effectively ruled Egypt as Ptolemy V's guardians<ref>] p. 194</ref><ref name="Clayton211">] p. 211</ref> until a revolt broke out two years later under general ], when Agathoclea and her family were ] by a mob in Alexandria. Tlepolemus, in turn, was replaced as guardian in 201 BC by ], who was chief minister at the time of the Memphis decree.<ref>] </ref> | ||

| Political forces beyond the borders of Egypt exacerbated the internal problems of the Ptolemaic kingdom. ] and ] had made a pact to divide Egypt's overseas possessions. Philip had seized several islands and cities in ] and ], while the ] (198 BC) had resulted in the transfer of ], including ], from the Ptolemies to the Seleucids. Meanwhile, in the south of Egypt, there was a long-standing revolt that had begun during the reign of Ptolemy |

Political forces beyond the borders of Egypt exacerbated the internal problems of the Ptolemaic kingdom. ] and ] had made a pact to divide Egypt's overseas possessions. Philip had seized several islands and cities in ] and ], while the ] (198 BC) had resulted in the transfer of ], including ], from the Ptolemies to the ]. Meanwhile, in the south of Egypt, there was a long-standing revolt that had begun during the reign of Ptolemy IV,<ref name="Cracking29"/> led by ] and by his successor ].<ref name="Assmann">] p. 376</ref> Both the war and the internal revolt were still ongoing when the young Ptolemy V was officially crowned at Memphis at the age of 12 (seven years after the start of his reign) and when, just over a year later, the Memphis decree was issued.<ref name="Clayton211"/> | ||

| ] ] ] grants tax immunity to the priests of the temple of ] |

] ] ] ] to the priests of the temple of ]]] | ||

| The stele is a late example of a class of donation stelae, which depicts the reigning monarch granting a tax exemption to the resident priesthood.<ref name="Kitchen59">] p. 59</ref> Pharaohs had erected these stelae over the previous 2,000 years, the earliest examples dating from the Egyptian ]. In earlier periods all such decrees were issued by the king himself, but the Memphis decree was issued by the priests, as the maintainers of traditional Egyptian culture.<ref name="focus13">] p. 13</ref> The decree records that Ptolemy V gave a gift of silver and grain to the temples.<ref name="Bevan 264–265">] pp. 264–265</ref> It also records that in the eighth year of his reign during a particularly high ], he had the excess waters dammed for the benefit of the farmers.<ref name="Bevan 264–265"/> In return for these concessions, the priesthood pledged that the king's birthday and coronation days would be celebrated annually, and that all the priests of Egypt would serve him alongside the other gods. The decree concludes with the instruction that a copy was to be placed in every temple, inscribed in the "language of the gods" (hieroglyphs), the "language of documents" (demotic), and the "language of the Greeks" as used by the Ptolemaic government.<ref name="Ray136">] p. 136</ref><ref>] p. 30</ref> | |||

| Stelae of this kind, which were established on the initiative of the temples rather than that of the king, are unique to Ptolemaic Egypt. In the preceding Pharaonic period it would have been unheard of for anyone but the divine rulers themselves to make national decisions: by contrast, this way of honouring a king was a feature of Greek cities. Rather than making his eulogy himself, the king had himself glorified and deified by his subjects or representative groups of his subjects.<ref>] p. 51, with references there to ]</ref> The decree records that Ptolemy V gave a gift of silver and grain to the ].<ref name="Bevan 264–265">] pp. 264–265</ref> It also records that there was particularly high ] in the eighth year of his reign, and he had the excess waters dammed for the benefit of the farmers.<ref name="Bevan 264–265"/> In return the priesthood pledged that the king's birthday and coronation days would be celebrated annually and that all the priests of Egypt would serve him alongside the other gods. The decree concludes with the instruction that a copy was to be placed in every temple, inscribed in the "language of the gods" (Egyptian hieroglyphs), the "language of documents" (Demotic), and the "language of the Greeks" as used by the Ptolemaic government.<ref name="Ray136">] p. 136</ref><ref>] p. 30</ref> | |||

| Securing the favour of the priesthood was essential for the Ptolemaic kings to retain effective rule over the populace. The ] of ]—where the king was crowned—were particularly important, as they were the highest religious authority of the time and had influence throughout the kingdom.<ref name="Shaw407">] p. 407</ref> Given that the decree was issued at Memphis—the ancient capital of Egypt—rather than Alexandria, the centre of government of the ruling Ptolemies, it is evident that the young king was anxious to gain their active support.<ref name="Walker19">] p. 19</ref> Hence, although the government of Egypt had been Greek-speaking ever since the conquests of ], the Memphis decree, like the ] in the series, included texts in Egyptian to display its relevance to the general populace by way of the literate Egyptian priesthood.<ref>] (no. 137 in online version)</ref> | |||

| Securing the favour of the priesthood was essential for the Ptolemaic kings to retain effective rule over the populace. The ] of ]—where the king was crowned—were particularly important, as they were the highest religious authorities of the time and had influence throughout the kingdom.<ref name="Shaw407">] p. 407</ref> Given that the decree was issued at Memphis, the ancient capital of Egypt, rather than Alexandria, the centre of government of the ruling Ptolemies, it is evident that the young king was anxious to gain their active support.<ref name="Walker19">] p. 19</ref> Thus, although the government of Egypt had been Greek-speaking ever since the ] of ], the Memphis decree, like the three similar ], included texts in Egyptian to show its connection to the general populace by way of the literate Egyptian priesthood.<ref>] (no. 137 in online version)</ref> | |||

| There exists no one definitive English translation of the decree because of the minor differences between the three original texts and because modern understanding of the ancient languages continues to develop. An up-to-date translation by R. S. Simpson, based on the demotic text, appears on the British Museum website.<ref>]; revised version of ] pp. 258–271</ref> It can be compared with ]'s full translation in ''The House of Ptolemy'' (1927),<ref name="Rosetta Text">] pp. </ref> based on the Greek text with footnote comments on variations between this and the two Egyptian texts. Bevan's version, abridged, begins thus: | |||

| There can be no one definitive English translation of the decree, not only because modern understanding of the ancient languages continues to develop, but also because of the minor differences between the three original texts. Older translations by ] (1904, 1913)<ref>]; ]</ref> and ] (1927)<ref name="Rosetta Text">] pp. </ref> are easily available but are now outdated, as can be seen by comparing them with the recent translation by R. S. Simpson, which is based on the demotic text and can be found online,<ref>]; a revised version of ] pp. 258–271</ref> or with the modern translations of all three texts, with introduction and facsimile drawing, that were published by Quirke and Andrews in 1989.<ref>]</ref> | |||

| {{quotation|In the reign of the young one—who has received the royalty from his father—lord of crowns, glorious, who has established Egypt, and is pious towards the gods, superior to his foes, who has restored the civilized life of men, lord of the Thirty Years' Feasts, even as Hephaistos the Great; a king, like the Sun, the great king of the upper and lower regions; offspring of the Gods Philopatores, one whom Hephaistos has approved, to whom the Sun has given the victory, the living image of Zeus, son of the Sun, Ptolemy living-for‑ever beloved of Ptah; in the ninth year, when Aëtus, son of Aëtus, was priest of Alexander ...; | |||

| The stele was almost certainly not originally placed at ] (Rosetta) where it was found, but more likely came from a temple site farther inland, possibly the royal town of ].<ref name="focus14">] p. 14</ref> The temple from which it originally came was probably closed around AD 392 when ] ] ordered the closing of all non-Christian temples of worship.<ref name="focus17">] p. 17</ref> The original stele broke at some point, its largest piece becoming what we now know as the Rosetta Stone. Ancient Egyptian temples were later used as quarries for new construction, and the Rosetta Stone probably was re-used in this manner. Later it was incorporated in the foundations of a fortress constructed by the ] ] ] ({{Circa|1416}}/18–1496) to defend the ] of the Nile at Rashid. There it lay for at least another three centuries until its rediscovery.<ref name="focus20">] p. 20</ref> | |||

| <p>The chief priests and prophets and those that enter the inner shrine for the robing of the gods, and the feather-bearers and the sacred scribes, and all the other priests ... being assembled in the temple in Memphis on this day, declared: | |||

| Three other inscriptions relevant to the same Memphis decree have been found since the discovery of the Rosetta Stone: the ], a stele found in ] and Noub Taha, and an inscription found at the ] (on the ]).<ref name="claryssenespoulous">] p. 42; ] pp. 283–285</ref> Unlike the Rosetta Stone, the hieroglyphic texts of these inscriptions were relatively intact. The Rosetta Stone had been deciphered long before they were found, but later Egyptologists have used them to refine the reconstruction of the hieroglyphs that must have been used in the lost portions of the hieroglyphic text on the Rosetta Stone. | |||

| <p>Since king Ptolemy, the everliving, the beloved of Ptah, the God Epiphanes Eucharistos, the son of king Ptolemy and queen Arsinoe, Gods Philopatores, has much benefited both the temples and those that dwell in them, as well as all those that are his subjects, being a god sprung from a god and goddess (like Horus, the son of Isis and Osiris, who avenged his father Osiris), and being benevolently disposed towards the gods, has dedicated to the temples revenues in money and corn, and has undertaken much outlay to bring Egypt into prosperity, and to establish the temples, and has been generous with all his own means, and of the revenues and taxes which he receives from Egypt some has wholly remitted and others has lightened, in order that the people and all the rest might be in prosperity during his reign ...; | |||

| {{Anchor|The rediscovery}} | |||

| <p>It seemed good to the priests of all the temples in the land to increase greatly the existing honours of king Ptolemy, the everliving, the beloved of Ptah ... And a feast shall be kept for king Ptolemy, the everliving, the beloved of Ptah, the God Epiphanes Eucharistos, yearly in all the temples of the land from the first of Thoth for five days; in which they shall wear garlands, and perform sacrifices, and the other usual honours; and the priests shall be called priests of the God Epiphanes Eucharistos in addition to the names of the other gods whom they serve; and his priesthood shall be entered upon all formal documents and private individuals shall also be allowed to keep the feast and set up the aforementioned shrine, and have it in their houses, performing the customary honours at the feasts, both monthly and yearly, in order that it may be known to all that the men of Egypt magnify and honour the God Epiphanes Eucharistos the king, according to the law.<ref name="Rosetta Text" />}} | |||

| The stele almost certainly did not originate in the town of ] (Rosetta) where it was found, but more likely came from a temple site further inland, possibly the royal town of ].<ref name="focus14">] p. 14</ref> The temple it originally came from was probably closed around AD 392 when ] emperor ] ordered the closing of all non-Christian temples of worship.<ref name="focus17">] p. 17</ref> At some point the original stele broke, its largest piece becoming what we now know as the Rosetta Stone.<ref name="focus20">] p. 20</ref> Ancient Egyptian temples were later used as quarries for new construction, and the Rosetta Stone probably was re-used in this manner. Later it was incorporated in the foundations of a fortress constructed by the ] ] ] (ca. 1416/18–1496) to defend the ] of the Nile at Rashid.<ref name="focus20"/> There it would lie for at least another three centuries until its rediscovery.<ref name="focus20"/> | |||

| Two other inscriptions of the Memphis decrees have been found since the discovery of the Rosetta Stone: the ] and an inscription found at the ]. Unlike the Rosetta Stone, their hieroglyphic inscriptions were relatively intact, and though the inscriptions on the Rosetta Stone had been deciphered long before the discovery of the other copies of the decree, subsequent Egyptologists including ] used these other inscriptions to further refine the actual hieroglyphs that must have been used in the lost portions of the hieroglyphic register on the Rosetta Stone.<ref name="Budge133">] p. 1</ref> | |||

| {{anchor|The rediscovery}} | |||

| ==Rediscovery== | ==Rediscovery== | ||

| ]'', 1802]] | ]'', 1802]] | ||

| On ]'s 1798 ], the ] was accompanied by the '']'', a corps of 167 technical experts (or, in French, "''savants''"). In mid-July 1799, as French soldiers under the command of Colonel d'Hautpoul were strengthening the defences of ], a couple of miles north-east of the Egyptian port city of Rashid, Lieutenant ] spotted a slab with inscriptions on one side that the soldiers had uncovered. He and d'Hautpoul saw at once that it might be important and informed general ], who happened to be at Rosetta.{{Cref2|A|1}} The find was announced to Napoleon's newly founded scientific association in Cairo, the ], in a report by Commission member ] noting that it contained three inscriptions, the first in hieroglyphs and the third in Greek, and rightly suggesting that the three inscriptions would be versions of the same text. Lancret's report, dated {{Nowrap|July 19,}} 1799, was read to a meeting of the Institute soon after {{Nowrap|July 25}}. Bouchard, meanwhile, transported the stone to Cairo for examination by scholars. Napoleon himself inspected what had already begun to be called ''la Pierre de Rosette'', the Rosetta Stone, shortly before his return to France in August 1799.<ref name="Cracking20"/> | |||

| ] under ] ] in 1798, accompanied by a corps of 151 technical experts (''savants''), known as the ]. On {{nowrap|15 July}} 1799, French soldiers under the command of Colonel d'Hautpoul were strengthening the defences of ], a couple of miles north-east of the Egyptian port city of Rosetta (modern-day Rashid). Lieutenant ] spotted a slab with inscriptions on one side that the soldiers had uncovered when demolishing a wall within the fort. He and d'Hautpoul saw at once that it might be important and informed General ], who happened to be at Rosetta.{{Cref2|A}} The find was announced to Napoleon's newly founded scientific association in Cairo, the ], in a report by Commission member ] noting that it contained three inscriptions, the first in hieroglyphs and the third in Greek, and rightly suggesting that the three inscriptions were versions of the same text. Lancret's report, dated {{Nowrap|19 July}} 1799, was read to a meeting of the Institute soon after {{Nowrap|25 July}}. Bouchard, meanwhile, transported the stone to Cairo for examination by scholars.<ref>] pp. 17–20</ref> | |||

| The discovery was reported in '']'', the official newspaper of the French expedition, in September: the anonymous reporter expressed a hope that the stone might one day be the key to deciphering hieroglyphs.{{Cref2|A|2}}<ref name="Cracking20"/> In 1800, three of the Commission's technical experts devised ways to make copies of the texts on the stone. One of these, the printer and gifted linguist ], is credited as the first to recognise that the middle text, originally guessed to be ], was, in fact, written in the Egyptian ] script, rarely used for stone inscriptions and, therefore, seldom seen by scholars at that time.<ref name="Cracking20"/> It was the artist and inventor ] who found a way to use the stone itself as a ];<ref name="Adkins38">] p. 38</ref> a slightly different method for reproducing the inscriptions was adopted by ]. The prints that resulted were taken to Paris by General ]. Scholars in Europe were now able to see the inscriptions and attempt to read them.<ref>] pp. 1–38</ref> | |||

| The discovery was reported in September in '']'', the official newspaper of the French expedition. The anonymous reporter expressed a hope that the stone might one day be the key to deciphering hieroglyphs.{{Cref2|A}}<ref name="Cracking20"/> In 1800 three of the commission's technical experts devised ways to make copies of the texts on the stone. One of these experts was ], a printer and gifted linguist, who is credited as the first to recognise that the middle text was written in the Egyptian ] script, rarely used for stone inscriptions and seldom seen by scholars at that time, rather than ] as had originally been thought.<ref name="Cracking20"/> It was artist and inventor ] who found a way to use the stone itself as a ] to reproduce the inscription.<ref name="Adkins38">] p. 38</ref> A slightly different method was adopted by ]. The prints that resulted were taken to Paris by General ]. Scholars in Europe were now able to see the inscriptions and attempt to read them.<ref>] pp. 1–38</ref> | |||

| After Napoleon's departure, ] held off British and ] attacks for a further 18 months. In March 1801, the British landed at ]. General ], who had been one of the first to see the stone in 1799, was now in command of the French expedition. His troops, including the Commission, marched north towards the Mediterranean coast to meet the enemy, transporting the stone along with other antiquities of all kinds. Defeated in battle, Menou and the remnant of his army retreated to Alexandria where they were surrounded and besieged, the stone now inside the city. He admitted defeat and surrendered on August 30.<ref>] vol. 2 pp. 274–284</ref><ref name="Cracking21" /> | |||

| After Napoleon's departure, French troops held off British and ] attacks for another 18 months. In March 1801, the British landed at ]. Menou was now in command of the French expedition. His troops, including the commission, marched north towards the Mediterranean coast to meet the enemy, transporting the stone along with many other antiquities. He was defeated in battle, and the remnant of his army retreated to Alexandria where they were ], with the stone now inside the city. ] on 30 August.{{sfn|Wilson|1803|pp=274–284}}<ref name="Cracking21"/> | |||

| ==From French to British possession== | ==From French to British possession== | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| After the surrender, a dispute arose over the fate of French archaeological and scientific discoveries in Egypt, including |

After the surrender, a dispute arose over the fate of the French archaeological and scientific discoveries in Egypt, including the artefacts, biological specimens, notes, plans, and drawings collected by the members of the commission. Menou refused to hand them over, claiming that they belonged to the institute. British General ] refused to end the siege until Menou gave in. Scholars ] and ], newly arrived from England, agreed to examine the collections in Alexandria and said they had found many artefacts that the French had not revealed. In a letter home, Clarke said that "we found much more in their possession than was represented or imagined".<ref name="Burleigh212">] p. 212</ref> | ||

| When Hutchinson claimed all materials were property of the ], a French scholar, ], said to Clarke and Hamilton that they would rather burn all their discoveries—referring ominously to the destruction of the ]—than turn them over. Clarke and Hamilton pleaded the French scholars' case and Hutchinson finally agreed that items such as natural history specimens would be the scholars' private property.<ref name="Cracking21">] p. 21</ref><ref name="Burleigh241">] p. 214</ref> Menou quickly claimed the stone, too, as his private property;<ref name="Budge2">] p. 2</ref> had this been accepted, he would have been able to take it to France.<ref name="Cracking21" /> Equally aware of the stone's unique value, General Hutchinson rejected Menou's claim. Eventually an agreement was reached, and the transfer of the objects was incorporated into the ] signed by representatives of the ], ] and ] forces. | |||

| How exactly the stone was transferred into British hands is not clear, as contemporary accounts differ. Colonel ], who was to escort it to England, claimed later that he had personally seized it from Menou and carried it away on a ]. In a much more detailed account, Edward Daniel Clarke stated that a French "officer and member of the Institute" had taken him, his student John Cripps, and Hamilton secretly into the back streets behind Menou's residence and revealed the stone hidden under protective carpets among Menou's baggage. According to Clarke, their informant feared that the stone might be stolen if French soldiers saw it. Hutchinson was informed at once and the stone was taken away—possibly by Turner and his gun-carriage.<ref name="Cracking2122">] pp. 21–22</ref> | |||

| Hutchinson claimed that all materials were property of the ], but French scholar ] told Clarke and Hamilton that the French would rather burn all their discoveries than turn them over, referring ominously to the destruction of the ]. Clarke and Hamilton pleaded the French scholars' case to Hutchinson, who finally agreed that items such as natural history specimens would be considered the scholars' private property.<ref name="Cracking21">] p. 21</ref><ref name="Burleigh241">] p. 214</ref> Menou quickly claimed the stone, too, as his private property.<ref name="Budge2">] p. 2</ref><ref name="Cracking21"/> Hutchinson was equally aware of the stone's unique value and rejected Menou's claim. Eventually an agreement was reached, and the transfer of the objects was incorporated into the ] signed by representatives of the ], ], and ] forces. | |||

| Turner brought the stone to England aboard the captured French frigate ], landing in ] in February 1802.<ref name="Andrews12">] p. 12</ref> His orders were to present it and the other antiquities to King ]. The King, represented by the ] ], directed that it should be placed in the ]. According to Turner's narrative, he urged—and Hobart agreed—that before its final deposit in the museum, the stone should be presented to scholars at the ], of which Turner was a member. It was first seen and discussed there at a meeting on {{Nowrap|March 11,}} 1802.{{Cref2|B}}{{Cref2|H|1}} | |||

| It is not clear exactly how the stone was transferred into British hands, as contemporary accounts differ. Colonel ], who was to escort it to England, claimed later that he had personally seized it from Menou and carried it away on a ]. In a much more detailed account, Edward Daniel Clarke stated that a French "officer and member of the Institute" had taken him, his student John Cripps, and Hamilton secretly into the back streets behind Menou's residence and revealed the stone hidden under protective carpets among Menou's baggage. According to Clarke, their informant feared that the stone might be stolen if French soldiers saw it. Hutchinson was informed at once and the stone was taken away—possibly by Turner and his gun-carriage.<ref name="Cracking2122">] pp. 21–22</ref> | |||

| ], 1874]] | |||

| Turner brought the stone to England aboard the captured French frigate ], landing in ] in February 1802.<ref name="Andrews12">] p. 12</ref> His orders were to present it and the other antiquities to King ]. The King, represented by ] ], directed that it should be placed in the ]. According to Turner's narrative, he and Hobart agreed that the stone should be presented to scholars at the ], of which Turner was a member, before its final deposit in the museum. It was first seen and discussed there at a meeting on {{Nowrap|11 March}} 1802.{{Cref2|B}}{{Cref2|H}} | |||

| During the course of 1802, the Society created four plaster casts of the inscriptions, which were given to the universities of ], ] and ] and to ]. Soon afterwards, prints of the inscriptions were made and circulated to European scholars.{{Cref2|E}} Before the end of 1802, the stone was transferred to the ], where it is located today.<ref name="Andrews12"/> New inscriptions painted in white on the left and right edges of the slab stated that it was "Captured in Egypt by the ] in 1801" and "Presented by King George III".<ref name="Cracking23"/> | |||

| ], 1874]] | |||

| The stone has been exhibited almost continuously in the British Museum since June 1802.<ref name="British Museum"/> During the middle of the 19th century, it was given the inventory number "EA 24", "EA" standing for "Egyptian Antiquities". It was part of a collection of Ancient Egyptian monuments captured from the French expedition, including a ] of ] (EA 10), the statue of a high priest of ] (EA 81) and a large granite fist (EA 9).<ref name="focus30-31">] pp. 30–31</ref> The objects were soon discovered to be too heavy for the floors of ] (the original building of The British Museum), and they were transferred to a new extension that was built onto the mansion. The Rosetta Stone was transferred to the sculpture gallery in 1834 shortly after Montagu House was demolished and replaced by the building that now houses the British Museum.<ref name="focus31">] p. 31</ref> According to the museum's records, the Rosetta Stone is its most-visited single object<ref name="focus7">] p. 7</ref> and a simple image of it has been the museum's best selling postcard for several decades.<ref name="focus47"/> | |||

| In 1802, the Society created four plaster casts of the inscriptions, which were given to the universities of ], ] and ] and to ]. Soon afterwards, prints of the inscriptions were made and circulated to European scholars.{{Cref2|E}} Before the end of 1802, the stone was transferred to the British Museum, where it is located today.<ref name="Andrews12"/> New inscriptions painted in white on the left and right edges of the slab stated that it was "Captured in Egypt by the ] in 1801" and "Presented by King George III".<ref name="Cracking23"/> | |||

| The stone has been exhibited almost continuously in the British Museum since June 1802.<ref name="British Museum"/> During the middle of the 19th century, it was given the inventory number "EA 24", "EA" standing for "Egyptian Antiquities". It was part of a collection of ancient Egyptian monuments captured from the French expedition, including a ] of ] (EA 10), the statue of a ] (EA 81), and a large granite fist (EA 9).<ref name="focus30-31">] pp. 30–31</ref> The objects were soon discovered to be too heavy for the floors of ] (the original building of The British Museum), and they were transferred to a new extension that was added to the mansion. The Rosetta Stone was transferred to the sculpture gallery in 1834 shortly after Montagu House was demolished and replaced by the building that now houses the British Museum.<ref name="focus31">] p. 31</ref> According to the museum's records, the Rosetta Stone is its most-visited single object,<ref name="focus7">] p. 7</ref> a simple image of it was the museum's best selling postcard for several decades,<ref name="focus47"/> and a wide variety of merchandise bearing the text from the Rosetta Stone (or replicating its distinctive shape) is sold in the museum shops.] | |||

| ] of the British Museum]] | |||

| The Rosetta Stone was originally displayed at a slight angle from the horizontal, and rested within a metal cradle that was made for it, which involved shaving off very small portions of its sides to ensure that the cradle fitted securely.<ref name="focus31"/> It originally had no protective covering, and |

The Rosetta Stone was originally displayed at a slight angle from the horizontal, and rested within a metal cradle that was made for it, which involved shaving off very small portions of its sides to ensure that the cradle fitted securely.<ref name="focus31"/> It originally had no protective covering, and it was found necessary by 1847 to place it in a protective frame, despite the presence of attendants to ensure that it was not touched by visitors.<ref name="focus32">] p. 32</ref> Since 2004 the conserved stone has been on display in a specially built case in the centre of the Egyptian Sculpture Gallery. A replica of the Rosetta Stone is now available in the ] of the British Museum, without a case and free to touch, as it would have appeared to early 19th-century visitors.<ref name="focus50">] p. 50</ref> | ||

| The museum was concerned about ] towards the end of the ] in 1917, and the Rosetta Stone was moved to safety, along with other portable objects of value. The stone spent the next two years {{Convert|15|m|ft|-1|abbr=on}} below ground level in a station of the ] at ] near ].<ref>"" (British Museum, 14 July 2017)</ref> Other than during wartime, the Rosetta Stone has left the British Museum only once: for one month in October 1972, to be displayed alongside Champollion's '']'' at the ] in Paris on the 150th anniversary of the letter's publication.<ref name="focus47">] p. 47</ref> Even when the Rosetta Stone was undergoing conservation measures in 1999, the work was done in the gallery so that it could remain visible to the public.<ref name="focus50-51">] pp. 50–51</ref> | |||

| ==Reading the Rosetta Stone== | ==Reading the Rosetta Stone== | ||

| {{For|more information|Decipherment of Egyptian |

{{For|more information|Decipherment of ancient Egyptian scripts}} | ||

| Prior to the discovery of the Rosetta Stone and its eventual decipherment, there had been no understanding of the ancient Egyptian language and script since shortly before the fall of the ]. The usage of the hieroglyphic script had become increasingly specialised even in the later ]; by the 4th century AD, few Egyptians were capable of reading hieroglyphs. Monumental use of hieroglyphs ceased after the closing of all non-Christian temples in the year 391 by the Roman Emperor ]; the last known inscription, found at ] and known as ], is dated to {{Nowrap|24 August 396 AD}}.<ref name="Ray11">] p. 11</ref> | |||

| Prior to the discovery of the Rosetta Stone and its eventual decipherment, the ancient ] and script had not been understood since shortly before the ]. The usage of the ] had become increasingly specialised even in the later ]; by the ] AD, few Egyptians were capable of reading them. Monumental use of hieroglyphs ceased as ]; the last known inscription is dated to {{Nowrap|24 August 394}}, found at ] and known as the ].<ref name="Ray11">] p. 11</ref> The last demotic text, also from Philae, was written in 452.<ref>] p. 30</ref> | |||

| Hieroglyphs retained their pictorial appearance and classical authors emphasised this aspect, in sharp contrast to the ] and ]. For example, in the 5th century the priest ] wrote ''Hieroglyphica'', an explanation of almost 200 ]s. Believed to be authoritative yet in many ways misleading, this and other works were a lasting impediment to the understanding of Egyptian writing.<ref name="Cracking1516">] pp. 15–16</ref> Later attempts at deciphering ] were made by ] in ] during the 9th and 10th centuries. ] and ] were the first historians to study this ancient script, by relating them to the contemporary ] used by ]ic priests in their time.<ref>] pp. 65–75</ref><ref name="Ray15">] pp. 15–18</ref> The study of hieroglyphs continued with fruitless attempts at decipherment by European scholars, notably ] in the 16th century, ] in the 17th and ] in the 18th.<ref name="Ray20">] pp. 20–24</ref> The discovery of the Rosetta Stone in 1799 would provide critical missing information, gradually revealed by a succession of scholars, that eventually allowed Jean-François Champollion to determine the nature of this mysterious script. | |||

| Hieroglyphs retained their pictorial appearance, and classical authors emphasised this aspect, in sharp contrast to the ] and ]. In the ], the priest ] wrote ''Hieroglyphica'', an explanation of almost 200 ]s. His work was believed to be authoritative, yet it was misleading in many ways, and this and other works were a lasting impediment to the understanding of Egyptian writing.<ref name="Cracking1516">] pp. 15–16</ref> Later attempts at decipherment were made by ] in ] during the 9th and 10th centuries. ] and ] were the first historians to study hieroglyphs, by comparing them to the contemporary ] used by ] priests in their time.<ref>] pp. 65–75</ref><ref name="Ray15">] pp. 15–18</ref> The study of hieroglyphs continued with fruitless attempts at decipherment by European scholars, notably ] in the 16th century<ref>] pp. 70–72</ref> and ] in the 17th.<ref name="Ray20">] pp. 20–24</ref> The discovery of the Rosetta Stone in 1799 provided critical missing information, gradually revealed by a succession of scholars, that eventually allowed ] to solve the puzzle that ] had called the ].<ref>{{cite book|last1=Powell|first1=Barry B.|title=Writing: Theory and History of the Technology of Civilization|publisher=John Wiley & Sons|isbn=978-1-4051-6256-2|page=91|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=b6Gx-MwHvaoC&pg=PA91|language=en|year=2009}}</ref> | |||

| {{anchor|The Greek text}} | |||

| {{Anchor|The Greek text}} | |||

| ===Greek text=== | ===Greek text=== | ||

| ]'s suggested reconstruction of the missing Greek text (1803)]] | ]'s suggested reconstruction of the missing Greek text (1803)]] | ||

| The ] text on the Rosetta Stone provided the starting point. Ancient Greek was widely known to scholars, but the details of its use in the ] period as a government language in Ptolemaic Egypt were not familiar: large scale discoveries of Greek ] were a long way in the future. Thus the earliest translations of the Greek text of the stone show the translators still struggling with the historical context and with administrative and religious jargon. ] verbally presented an English translation of the Greek text at a ] meeting in April 1802.<ref name="Budge133"/><ref name="Andrews13">] p. 13</ref> Meanwhile, two of the lithographic copies made in Egypt had reached the ] in Paris, in 1801. There, the librarian and antiquarian ] set to work on a translation of the Greek. Almost immediately dispatched elsewhere on Napoleon's orders, he left his unfinished work in the hands of a colleague, ], who in 1803 produced the first published translations of the Greek text, in both ] and French to ensure that they would circulate widely.{{Cref2|F}} At ], ] worked on the missing lower right corner of the Greek text. He produced a skilful suggested reconstruction, which was soon being circulated by the Society of Antiquaries alongside its prints of the inscription. At ] at almost the same moment, the Classical historian ], working from one of these prints, made a new Latin translation of the Greek text that was more reliable than Ameilhon's. First published in 1803,{{Cref2|G}} it was reprinted by the Society of Antiquaries, alongside Weston's previously unpublished English translation, ] narrative, and other documents, in a special issue of its journal ''Archaeologia'' in 1811.{{Cref2|H|2}}<ref>] pp. 27–28</ref><ref name="Cracking22">] p. 22</ref> | |||

| The ] text on the Rosetta Stone provided the starting point. Ancient Greek was widely known to scholars, but they were not familiar with details of its use in the ] period as a government language in Ptolemaic Egypt; large-scale discoveries of Greek ] were a long way in the future. Thus, the earliest translations of the Greek text of the stone show the translators still struggling with the historical context and with administrative and religious jargon. ] verbally presented an English translation of the Greek text at a ] meeting in April 1802.<ref name="Budge133">] p. 1</ref><ref name="Andrews13">] p. 13</ref> | |||

| {{anchor|The Demotic text}} | |||

| Meanwhile, two of the lithographic copies made in Egypt had reached the ] in Paris in 1801. There, librarian and antiquarian ] set to work on a translation of the Greek, but he was dispatched elsewhere on Napoleon's orders almost immediately, and he left his unfinished work in the hands of colleague ]. Ameilhon produced the first published translations of the Greek text in 1803, in both ] and French to ensure that they would circulate widely.{{Cref2|H}} At ], ] worked on the missing lower right corner of the Greek text. He produced a skilful suggested reconstruction, which was soon being circulated by the Society of Antiquaries alongside its prints of the inscription. At almost the same moment, ] in ] was making a new Latin translation of the Greek text that was more reliable than Ameilhon's and was first published in 1803.{{Cref2|G}} It was reprinted by the Society of Antiquaries in a special issue of its journal ''Archaeologia'' in 1811, alongside Weston's previously unpublished English translation, ] narrative, and other documents.{{Cref2|H}}<ref>] pp. 27–28</ref><ref name="Cracking22">] p. 22</ref> | |||

| {{Anchor|The Demotic text}} | |||

| ===Demotic text=== | ===Demotic text=== | ||

| At the time of the stone's discovery, Swedish diplomat and scholar ] was working on a little-known script of which some examples had recently been found in Egypt, which came to be known as ]. He called it "cursive Coptic" because he was convinced that it was used to record some form of the ] (the direct descendant of Ancient Egyptian), although it had few similarities with the later ]. French Orientalist ] had been discussing this work with Åkerblad when, in 1801, he received one of the early lithographic prints of the Rosetta Stone, from ], French minister of the interior. He realised that the middle text was in this same script. He and Åkerblad set to work, both focusing on the middle text and assuming that the script was alphabetical. They attempted to identify the points where Greek names ought to occur within this unknown text, by comparing it with the Greek. In 1802, Silvestre de Sacy reported to Chaptal that he had successfully identified five names ("'']''", "'']''", "'']''", "'']''", and Ptolemy's title "''Epiphanes''"),{{Cref2|C}} while Åkerblad published an alphabet of 29 letters (more than half of which were correct) that he had identified from the Greek names in the Demotic text.{{Cref2|D}}<ref name="Budge133"/> They could not, however, identify the remaining characters in the Demotic text, which, as is now known, included ] and other symbols alongside the phonetic ones.<ref>] pp. 59–61</ref> | |||

| ]'s table of Demotic phonetic characters and their ] equivalents (1802)]] | |||

| At the time of the stone's discovery, the ] ] and scholar ] was working on a little-known script of which some examples had recently been found in Egypt, which came to be known as Demotic. He called it "cursive Coptic" because, although it had few similarities with the later ], he was convinced that it was used to record some form of the ] (the direct descendant of ancient Egyptian). The French Orientalist ], who had been discussing this work with Åkerblad, received in 1801 from ], French minister of the interior, one of the early lithographic prints of the Rosetta Stone, and realised that the middle text was in this same script. He and Åkerblad set to work, both focusing on the middle text and assuming that the script was alphabetic. They attempted, by comparison with the Greek, to identify within this unknown text the points where Greek names ought to occur. In 1802, Silvestre de Sacy reported to Chaptal that he had successfully identified five names ("'']''", "'']''", "'']''", "'']''" and Ptolemy's title "''Epiphanes''"),{{Cref2|C}} while Åkerblad published an alphabet of 29 letters (more than half of which were correct) that he had identified from the Greek names in the demotic text.{{Cref2|D}}<ref name="Budge133"/> They could not, however, identify the remaining characters in the demotic text, which, as is now known, included ] and other symbols alongside the phonetic ones.<ref>] pp. 59–61</ref> | |||

| <gallery widths="200" heights="200" mode="packed"> | |||

| File:Akerblad.jpg|alt=Illustration depicting two columns of Demotic text and their Greek equivalent, as devised by Johan David Åkerblad in 1802|]'s table of Demotic phonetic characters and their ] equivalents (1802) | |||

| File:DemoticScriptsRosettaStoneReplica.jpg|Replica of the Demotic texts | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| {{ |

{{Anchor|The hieroglyphic text}} | ||

| ===Hieroglyphic text=== | ===Hieroglyphic text=== | ||

| ]'s table of hieroglyphic phonetic characters with their demotic and Coptic equivalents (1822)]] | |||

| Silvestre de Sacy eventually gave up work on the stone, but he was to make another contribution. In 1811, prompted by discussions with a Chinese student about ], Silvestre de Sacy considered a suggestion made by ] in 1797 that the foreign names in Egyptian hieroglyphic inscriptions might be written phonetically; he also recalled that as long ago as 1761, ] had suggested that the characters enclosed in ]s in hieroglyphic inscriptions were proper names. Thus, when Thomas Young, foreign secretary of the ], wrote to him about the stone in 1814, Silvestre de Sacy suggested in reply that in attempting to read the hieroglyphic text, Young might look for cartouches that ought to contain Greek names, and try to identify phonetic characters in them.<ref>] p. 61</ref> | |||

| Silvestre de Sacy eventually gave up work on the stone, but he was to make another contribution. In 1811, prompted by discussions with a Chinese student about ], Silvestre de Sacy considered a suggestion made by ] in 1797 that the foreign names in Egyptian hieroglyphic inscriptions might be written phonetically; he also recalled that as early as 1761, ] had suggested that the characters enclosed in ]s in hieroglyphic inscriptions were proper names. Thus, when ], foreign secretary of the ], wrote to him about the stone in 1814, Silvestre de Sacy suggested in reply that in attempting to read the hieroglyphic text, Young might look for cartouches that ought to contain Greek names and try to identify phonetic characters in them.<ref>] p. 61</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| Young did so, with two results that together paved the way for the final decipherment. He discovered in the hieroglyphic text the phonetic characters "''p t o l m e s''" (in today's transliteration "''p t w l m y s''"), that were used to write the Greek name "''Ptolemaios''". He also noticed that these characters resembled the equivalent ones in the Demotic script, and went on to note as many as 80 similarities between the hieroglyphic and demotic texts on the stone, an important discovery because the two scripts were previously thought to be entirely different from one another. This led him to deduce correctly that the demotic script was only partly phonetic, also consisting of ideographic characters imitated from hieroglyphs.{{Cref2|I}} Young's new insights were prominent in the long article "Egypt" that he contributed to the '']'' in 1819.{{Cref2|J}} He could, however, get no further.<ref>] pp. 61–64</ref> | |||

| Young did so, with two results that together paved the way for the final decipherment. In the hieroglyphic text, he discovered the phonetic characters "{{transl|egy|p t o l m e s}}" (in today's transliteration "{{transl|egy|p t w l m y s}}") that were used to write the Greek name "{{transl|grc|Ptolemaios}}". He also noticed that these characters resembled the equivalent ones in the demotic script, and went on to note as many as 80 similarities between the hieroglyphic and demotic texts on the stone, an important discovery because the two scripts were previously thought to be entirely different from one another. This led him to deduce correctly that the demotic script was only partly phonetic, also consisting of ideographic characters derived from hieroglyphs.{{Cref2|I}} Young's new insights were prominent in the long article "Egypt" that he contributed to the {{lang|la-GB|]}} in 1819.{{Cref2|J}} He could make no further progress, however.<ref>] pp. 61–64</ref> | |||

| In 1814, Young first exchanged correspondence about the stone with ], a teacher at ] who had produced a scholarly work on ancient Egypt. Champollion, in 1822, saw copies of the brief hieroglyphic and Greek inscriptions of the ], on which ] had tentatively noted the names "Ptolemaios" and "Kleopatra" in both languages.<ref>] p. 32</ref> From this, Champollion identified the phonetic characters "''k l e o p a t r a''" (in today's transliteration "''q l ỉ w p ɜ d r ɜ .t''").<ref name="Budge136">] pp. 3–6</ref> On the basis of this and the foreign names on the Rosetta Stone, he quickly constructed an alphabet of phonetic hieroglyphic characters, which appears, printed from his hand-drawn chart, in his "'']''", addressed at the end of 1822 to ], secretary of the Paris ] and immediately published by the Académie.{{Cref2|K}} This "Letter" marks the real breakthrough to reading Egyptian hieroglyphs, not only for the alphabet chart and the main text, but also for the postscript in which Champollion notes that similar phonetic characters seemed to occur not only in Greek names but also in native Egyptian names. During 1823, he confirmed this, identifying the names of pharaohs ] and ] written in cartouches in far older hieroglyphic inscriptions that had been copied by Bankes at ] and sent on to Champollion by ].{{Cref2|M}} From this point, the stories of the Rosetta Stone and the ] diverge, as Champollion drew on many other texts to develop a first ancient Egyptian grammar and a hieroglyphic dictionary, both of which were to be published after his death.<ref>] p. 45</ref> | |||

| In 1814, Young first exchanged correspondence about the stone with ], a teacher at ] who had produced a scholarly work on ancient Egypt. Champollion saw copies of the brief hieroglyphic and Greek inscriptions of the ] in 1822, on which ] had tentatively noted the names "{{transl|grc|Ptolemaios}}" and "{{transl|grc|Kleopatra}}" in both languages.<ref>] p. 32</ref> From this, Champollion identified the phonetic characters {{transl|egy|k l e o p a t r a}} (in today's transliteration {{transl|egy|q l i҆ w p 3 d r 3.t}}).<ref name="Budge136">] pp. 3–6</ref> On the basis of this and the foreign names on the Rosetta Stone, he quickly constructed an alphabet of phonetic hieroglyphic characters, completing his work on 14 September and announcing it publicly on 27 September in a lecture to the {{lang|fr|]}}.<ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Hr3wCAAAQBAJ&pg=PA97 |pages=98–99 |title=The Reality of the Unobservable: Observability, Unobservability and Their Impact on the Issue of Scientific Realism |author1=E. Agazzi |author2=M. Pauri |publisher=Springer Science & Business Media |year=2013|isbn=978-94-015-9391-5 }}</ref> On the same day he wrote the famous "{{lang|fr|]}}" to ], secretary of the Académie, detailing his discovery.{{Cref2|K}} In the postscript Champollion notes that similar phonetic characters seemed to occur in both Greek and Egyptian names, a hypothesis confirmed in 1823, when he identified the names of pharaohs ] and ] written in cartouches at ]. These far older hieroglyphic inscriptions had been copied by Bankes and sent to Champollion by ].{{Cref2|M}} From this point, the stories of the Rosetta Stone and the ] diverge, as Champollion drew on many other texts to develop an Ancient Egyptian grammar and a hieroglyphic dictionary which were published after his death in 1832.<ref>] p. 45</ref> | |||

| ===Later work=== | ===Later work=== | ||

| ] of the British Museum, now the Enlightenment Gallery]] | |||

| Work on the stone now focused on fuller understanding of the texts and their contexts by comparing the three versions with one another. In 1824, the Classical scholar ] promised to prepare a new literal translation of the Greek text for Champollion's use; Champollion promised in return an analysis of all the points at which the three texts seemed to differ. At Champollion's sudden death in 1832, his draft of this analysis could not be found, and Letronne's work stalled. At the death in 1838 of ], Champollion's former student and assistant, this and other missing drafts were found among his papers (incidentally demonstrating that Salvolini's own publication on the stone, in 1837, was ]).{{Cref2|O}} Letronne was at last able to complete his commentary on the Greek text and his new French translation of it, which appeared in 1841.{{Cref2|P|1}} During the early 1850s, two German Egyptologists, ] and ], produced revised Latin translations based on the demotic and hieroglyphic texts;{{Cref2|Q}}{{Cref2|R}} the first English translation, the work of three members of the ] at the ], followed in 1858.{{Cref2|S}} | |||

| Work on the stone now focused on fuller understanding of the texts and their contexts by comparing the three versions with one another. In 1824 Classical scholar ] promised to prepare a new literal translation of the Greek text for Champollion's use. Champollion in return promised an analysis of all the points at which the three texts seemed to differ. Following Champollion's sudden death in 1832, his draft of this analysis could not be found, and Letronne's work stalled. ], Champollion's former student and assistant, died in 1838, and this analysis and other missing drafts were found among his papers. This discovery incidentally demonstrated that Salvolini's own publication on the stone, published in 1837, was ].{{Cref2|O}} Letronne was at last able to complete his commentary on the Greek text and his new French translation of it, which appeared in 1841.{{Cref2|P}} During the early 1850s, German Egyptologists ] and ] produced revised Latin translations based on the demotic and hieroglyphic texts.{{Cref2|Q}}{{Cref2|R}} The first English translation followed in 1858, the work of three members of the ] at the ].{{Cref2|S}} | |||

| Whether one of the three texts was the standard version, from which the other two were originally translated, is a question that has remained controversial. Letronne attempted to show in 1841 that the Greek version, the product of the Egyptian government under the Macedonian ], was the original.{{Cref2|P}} Among recent authors, John Ray has stated that "the hieroglyphs were the most important of the scripts on the stone: they were there for the gods to read, and the more learned of their priesthood".<ref name="Ray3"/> Philippe Derchain and Heinz Josef Thissen have argued that all three versions were composed simultaneously, while Stephen Quirke sees in the decree "an intricate coalescence of three vital textual traditions".<ref>] p. 10</ref> ] points out that the hieroglyphic version strays from archaic formalism and occasionally lapses into language closer to that of the demotic register that the priests more commonly used in everyday life.<ref name="focus13">] p. 13</ref> The fact that the three versions cannot be matched word for word helps to explain why the decipherment has been more difficult than originally expected, especially for those original scholars who were expecting an exact bilingual key to Egyptian hieroglyphs.<ref name="Cracking3031">] pp. 30–31</ref> | |||

| ===Rivalries=== | ===Rivalries=== | ||

| ] in ], France, the birthplace of ]]] | ] in ], France, the birthplace of ]]] | ||

| Even before the Salvolini affair, disputes over precedence and plagiarism punctuated the ] story. Thomas Young's work is acknowledged in Champollion's 1822 ''Lettre à M. Dacier'', but incompletely, according to British critics: for example, ], a sub-editor on the ''Encyclopædia Britannica'' (which had published Young's 1819 article), contributed anonymously a series of review articles to the '']'' in 1823, praising Young's work highly and alleging that the "unscrupulous" Champollion ] it.<ref>] pp. 35–38</ref><ref>] pp. 65–68</ref> These articles were translated into French by ] and published in book form in 1827.{{Cref2|N}} Young's own 1823 publication reasserted the contribution that he had made.{{Cref2|L}} The early deaths of Young and Champollion, in 1829 and 1832, did not put an end to these disputes; the authoritative work on the stone by the ] curator E. A. Wallis Budge, published in 1904, gives special emphasis to Young's contribution by contrast with Champollion's.<ref>] vol. 1 pp. 59–134</ref> In the early 1970s, French visitors complained that the portrait of Champollion was smaller than one of Young on an adjacent information panel; English visitors complained that the opposite was true. Both portraits were in fact the same size.<ref name="focus47"/> | |||

| Even before the Salvolini affair, disputes over precedence and plagiarism punctuated the decipherment story. Thomas Young's work is acknowledged in Champollion's 1822 ''Lettre à M. Dacier'', but incompletely, according to early British critics: for example, ], a sub-editor on the ''Encyclopædia Britannica'' (which had published Young's 1819 article), anonymously contributed a series of review articles to the '']'' in 1823, praising Young's work highly and alleging that the "unscrupulous" Champollion plagiarised it.<ref>]{{Broken anchor|date=2024-06-30|bot=User:Cewbot/log/20201008/configuration|target_link=#Parkinson99|reason= }} pp. 35–38</ref><ref>] pp. 65–68</ref> These articles were translated into French by ] and published in book form in 1827.{{Cref2|N}} Young's own 1823 publication reasserted the contribution that he had made.{{Cref2|L}} The early deaths of Young (1829) and Champollion (1832) did not put an end to these disputes. In his work on the stone in 1904 ] gave special emphasis to Young's contribution compared with Champollion's.<ref>] vol. 1 pp. 59–134</ref> In the early 1970s, French visitors complained that the portrait of Champollion was smaller than one of Young on an adjacent information panel; English visitors complained that the opposite was true. The portraits were in fact the same size.<ref name="focus47"/> | |||

| ==Requests for repatriation to Egypt== | ==Requests for repatriation to Egypt== | ||

| Calls for the Rosetta Stone to be returned to Egypt were made in July 2003 by ], then Secretary-General of Egypt's ]. These calls, expressed in the Egyptian and international media, asked that the stele be ] to Egypt, commenting that it was the "icon of our Egyptian identity".<ref name="Edwardes">]</ref> He repeated the proposal two years later in Paris, listing the stone as one of several key items belonging to Egypt's cultural heritage, a list which also included: the iconic ] in the ]; a statue of the ] architect ] in the ] in ], Germany; the ] in the ] in Paris; and the ] in the ] in ].<ref>{{cite web|author=Sarah El Shaarawi |title=Egypt's Own: Repatriation of Antiquities Proves to be a Mammoth Task | date=5 October 2016| url=http://newsweekme.com/egypts-repatriation-antiquities-proves-mammoth-task/|publisher=Newsweek – Middle East}}</ref> In August 2022, Zahi Hawass reiterated his previous demands.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2022/08/22/return-rosetta-stone-to-egypt-demands-countrys-leading-archaeologist-zahi-hawass|title='Return Rosetta Stone to Egypt' demands country's leading archaeologist Zahi Hawass|date=22 August 2022|website=The Art Newspaper – International art news and events}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.thenationalnews.com/world/2022/08/19/new-push-to-bring-rosetta-stone-back-to-egypt-amid-awakening-on-colonial-loot/|title=New push to bring Rosetta Stone back to Egypt amid 'awakening' on colonial loot|first=Tim|last=Stickings|date=19 August 2022|website=The National}}</ref> | |||

| In 2005, the British Museum presented Egypt with a full-sized fibreglass colour-matched replica of the stele. This was initially displayed in the renovated ], an Ottoman house in the town of ] (Rosetta), the closest city to the site where the stone was found.<ref>]</ref> In November 2005, Hawass suggested a three-month loan of the Rosetta Stone, while reiterating the eventual goal of a permanent return.<ref>]</ref> In December 2009, he proposed to drop his claim for the permanent return of the Rosetta Stone if the British Museum lent the stone to Egypt for three months for the opening of the ] at ] in 2013.<ref>]</ref> | |||

| {{stack|]), Egypt]]}} | |||

| As ] has observed: "The day may come when the stone has spent longer in the British Museum than it ever did in Rosetta."<ref name="Ray4">] p. 4</ref> | |||

| National museums typically express strong opposition to the repatriation of objects of international cultural significance such as the Rosetta Stone. In response to repeated Greek requests for return of the ] from the ] and similar requests to other museums around the world, in 2002, over 30 of the world's leading museums—including the British Museum, the Louvre, the ] in Berlin, and the ] in New York City—issued a joint statement: | |||

| {{Blockquote|Objects acquired in earlier times must be viewed in the light of different sensitivities and values reflective of that earlier era...museums serve not just the citizens of one nation but the people of every nation.<ref>]</ref>}} | |||

| ]), ]]] | |||

| As ] has observed, "the day may come when the stone has spent longer in the British Museum than it ever did in Rosetta."<ref name="Ray4">] p. 4</ref> There is strong opposition among national museums to the repatriation of objects of international cultural significance such as the Rosetta Stone. In response to repeated Greek requests for return of the ] and similar requests to other museums around the world, in 2002, over 30 of the world's leading museums—including the ], ], the ] in Berlin and the ] in New York City—issued a joint statement declaring that "objects acquired in earlier times must be viewed in the light of different sensitivities and values reflective of that earlier era" and that "museums serve not just the citizens of one nation but the people of every nation".<ref>]</ref> | |||

| ==Idiomatic use== | ==Idiomatic use== | ||

| Various ancient bilingual or even trilingual ] documents have sometimes been described as "Rosetta stones", as they permitted the decipherment of ancient written scripts. For example, the bilingual ]-] coins of the ] king ] have been described as "little Rosetta stones", allowing ]'s initial progress towards deciphering the ], thus unlocking ancient ].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Aruz |first1=Joan |last2=Fino |first2=Elisabetta Valtz |title=Afghanistan: Forging Civilizations Along the Silk Road |date=2012 |publisher=Metropolitan Museum of Art |isbn=978-1-58839-452-1 |page=33 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=p4_it5yw9WsC&pg=PA33 |language=en}}</ref> The ] has also been compared to the Rosetta stone, as it links the translations of three ancient ] languages: ], ], and ].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Dudney |first1=Arthur |title=Delhi: Pages From a Forgotten History |date=2015 |publisher=Hay House, Inc |isbn=978-93-84544-31-7 |page=55 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=OQ6fCwAAQBAJ&pg=PT55 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| The term ''Rosetta stone'' has been used ]atically to represent a crucial key to the process of decryption of encoded information, especially when a small but representative sample is recognised as the clue to understanding a larger whole.<ref name="OUP">] s.v. ""</ref> According to the '']'', the first figurative use of the term appeared in the 1902 edition of the '']'' relating to an entry on the chemical analysis of ].<ref name="OUP"/> An almost literal use of the phrase appears in popular fiction within ]' 1933 novel '']'', where the protagonist finds a manuscript written in ] that provides a key to understanding additional scattered material that is sketched out in both ] and on ].<ref name="OUP"/> Perhaps its most important and prominent usage in scientific literature was ] ]'s reference in a 1979 ] article on ] where he says that "the spectrum of the hydrogen atoms has proved to be the Rosetta stone of modern physics: once this pattern of lines had been deciphered much else could also be understood".<ref name="OUP"/> | |||

| The term ''Rosetta stone'' has been also used ]atically to denote the first crucial key in the process of decryption of encoded information, especially when a small but representative sample is recognised as the clue to understanding a larger whole.<ref name="OUP">] s.v. "" {{webarchive|url=https://archive.today/20110620211021/http://dictionary.oed.com/cgi/findword?query_type=word&find=Find+word&queryword=Rosetta+stone |date=June 20, 2011 }}</ref> According to the '']'', the first figurative use of the term appeared in the 1902 edition of the '']'' relating to an entry on the chemical analysis of ].<ref name="OUP"/> Another use of the phrase is found in ]'s 1933 novel '']'', where the protagonist finds a manuscript written in ] that provides a key to understanding additional scattered material that is sketched out in both ] and on ].<ref name="OUP"/> | |||

| Since then the term has been widely used in other contexts. For example, fully understanding the key set of genes to the ] has been described as being "the Rosetta Stone of immunology".<ref>]</ref> The flowering plant '']'' has been called the "Rosetta Stone of flowering time".<ref>]</ref> A ] (GRB) found in conjunction with a ] has been called a Rosetta Stone for understanding the origin of GRBs.<ref>]</ref> The technique of ] has been called a Rosetta Stone for clinicians trying to understand the complex process by which the ] of the ] can be filled during various forms of ].<ref>]</ref> | |||

| Since then, the term has been widely used in other contexts. For example, ] ] in a 1979 '']'' article on ] wrote that "the spectrum of the hydrogen atoms has proven to be the Rosetta Stone of modern physics: once this pattern of lines had been deciphered much else could also be understood".<ref name="OUP"/> Fully understanding the key set of genes to the ] has been described as "the Rosetta Stone of immunology".<ref>]</ref> The flowering plant '']'' has been called the "Rosetta Stone of flowering time".<ref>]</ref> A ] (GRB) found in conjunction with a ] has been called a Rosetta Stone for understanding the origin of GRBs.<ref>]</ref> The technique of ] has been called a Rosetta Stone for clinicians trying to understand the complex process by which the ] of the ] can be filled during various forms of ].<ref>]</ref> The ]'s '']'' spacecraft, launched to study the ] ] in the hope that determining its composition will advance understanding of the origins of the ].<ref>{{Cite web |title=Rosetta's Comet Target 'Releases' Plentiful Water |url=https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/rosettas-comet-target-releases-plentiful-water/ |access-date=2024-11-19 |website=NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) |language=en-US}}</ref> | |||

| The name has also become used in various forms of translation software. ] is a brand of language learning software published by Rosetta Stone Ltd., headquartered in ], US. "]" is the name of a "lightweight dynamic translator" that enables applications compiled for ] processor to run on Apple systems using an ] processor. "Rosetta" is an online language translation tool to help localisation of software, developed and maintained by ] as part of the ] project. Similarly, ] is a ] for predicting (or ''translating'') protein structures. The ] brings language specialists and native speakers together to develop a meaningful survey and near permanent archive of 1,500 languages, intended to last from AD 2000 to 12,000. The ] is on a ten-year mission to study the ] ], in the hopes that determining its composition will reveal the origins of the ]. | |||