| Revision as of 18:41, 17 January 2006 edit64.83.59.54 (talk) →External links← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 04:14, 6 January 2025 edit undoYedaman54 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users13,936 editsNo edit summaryTag: 2017 wikitext editor | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Capital city of Virginia, United States}} | |||

| :''This article is about the city in ]. For information on other cities with the same name, please see ].'' | |||

| {{distinguish|Richmond County, Virginia}} | |||

| {| border="2" cellpadding="4" cellspacing="0" style="margin: 1em 1em 1em 0; background: #f9f9f9; border: 1px #aaa solid; border-collapse: collapse; font-size: 95%;" width="300px" align="right" style="border: 1em solid white") | |||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=October 2019}} | |||

| <caption><font size="+1">'''Richmond, Virginia'''</font></caption> | |||

| {{Use American English|date=August 2015}} | |||

| |- | |||

| {{Infobox settlement | |||

| | align="center" colspan=2 | ] | |||

| | name = Richmond | |||

| |- | |||

| | settlement_type = ] and ] | |||

| | align="center" width="140px" | ] | |||

| | image_skyline = {{multiple image | |||

| | align="center" width="140px" | ] | |||

| | border = infobox | |||

| |- | |||

| | total_width = 300 | |||

| | align="center" width="140px" | City ] | |||

| | perrow = 1/2/2/2 | |||

| | align="center" width="140px" | City ] | |||

| | caption_align = center | |||

| |- | |||

| | image1 = A downtown view of Richmond, VA.jpg | |||

| | align="center" colspan=2 | <font size="-1">City ]: <i>Sic Itur Ad Astra</i><br> | |||

| | caption1 = ] skyline along the ] | |||

| (] for, "Such is the way to the Stars")</font> | |||

| | image2 = St. John's Church in Richmond, VA (2011) IMG 4046.JPG | |||

| |- | |||

| | caption2 = ] | |||

| | align="center" colspan=2 | <font size="-1">City ]: "One City, Our City" or "Easy to Love" | |||

| | image3 = Street Scene along Monument Avenue - Richmond - Virginia - USA - 02 (32839955447).jpg | |||

| | caption3 = ] | |||

| | image4 = Main Street Station.jpg | |||

| | caption4 = ] | |||

| | image5 = State Capitol of the Commonwealth of Virginia (7358972234).jpg | |||

| | caption5 = ] | |||

| | image6 = Egyptian Building.JPG | |||

| | caption6 = ] | |||

| | image7 = E201001 0049 02.tif | |||

| | caption7 = ] | |||

| }} | |||

| | image_flag = Flag of Richmond, Virginia.jpg | |||

| | flag_size = 110px | |||

| | image_seal = Seal of Richmond, Virginia.svg | |||

| | seal_size = 90px | |||

| | nickname = "RVA",<ref name="RVA">Per www.richmondgov.com & {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210426214039/https://acronyms.thefreedictionary.com/RVA |date=April 26, 2021 }}.</ref> "River City"<ref>''City Connection'', Office of the Press Secretary to the Mayor. {{Webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110930174829/http://www.richmondgov.com/PressSecretaryMayor/documents/CityConnection.pdf#page=2 |date=September 30, 2011 }}. January–March 2010 edition. Retrieved February 8, 2010.</ref>{{Failed verification|date=January 2019}} | |||

| | motto = {{langx|la|Sic Itur Ad Astra}}<br />(Thus do we reach the stars) | |||

| | image_map = {{maplink | |||

| | frame = yes | |||

| | plain = yes | |||

| | frame-align = center | |||

| | frame-width = 290 | |||

| | frame-height = 290 | |||

| | frame-coord = {{coord|qid=Q43421}} | |||

| | zoom = 10 | |||

| | type = shape | |||

| | marker = city | |||

| | stroke-width = 2 | |||

| | stroke-color = #0096FF | |||

| | fill = #0096FF | |||

| | id2 = Q43421 | |||

| | type2 = shape-inverse | |||

| | stroke-width2 = 2 | |||

| | stroke-color2 = #5F5F5F | |||

| | stroke-opacity2 = 0 | |||

| | fill2 = #000000 | |||

| | fill-opacity2 = 0 | |||

| }} | |||

| | map_caption = Interactive map of Richmond | |||

| | pushpin_map = Virginia#USA | |||

| | pushpin_label = Richmond | |||

| | pushpin_mapsize = 280px | |||

| | pushpin_map_caption = Location within Virginia##Location within the contiguous United States | |||

| | pushpin_relief = yes | |||

| | coordinates = {{coord|37|32|27|N|77|26|12|W|region:US-VA|display=inline,title}} | |||

| | subdivision_type = Country | |||

| | subdivision_name = United States | |||

| | subdivision_type1 = ] | |||

| | subdivision_name1 = ] | |||

| | established_title = Incorporated | |||

| | established_date = ] | |||

| | named_for = ] | |||

| | government_type = | |||

| | leader_title = ] | |||

| | leader_name = ] (]) | |||

| | total_type = City | |||

| | area_total_sq_mi = 62.57 | |||

| | area_land_sq_mi = 59.92 | |||

| | area_water_sq_mi = 2.65 | |||

| | elevation_m = 65 | |||

| | elevation_ft = 213 | |||

| | population_rank = ] in the United States<br> ] in Virginia | |||

| | population_total = 226610 | |||

| | population_as_of = ] | |||

| | population_density_sq_mi = 3782 | |||

| | population_urban = 1,059,150 (]) | |||

| | population_density_urban_km2 = 798.2 | |||

| | population_density_urban_sq_mi = 2,067.3 | |||

| | population_metro = 1,339,182 (]) | |||

| | population_demonym = Richmonder | |||

| | demographics_type2 = GDP | |||

| | demographics2_footnotes = <ref>{{Cite web|title=Total Real Gross Domestic Product for Richmond, VA (MSA)|url=https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/RGMP40060|website=fred.stlouisfed.org}}</ref> | |||

| | demographics2_title1 = Metro | |||

| | demographics2_info1 = $116.960 billion (2023) | |||

| | postal_code_type = ]s | |||

| | postal_code = 23173, 23218–23242, 23249–23250, 23255, 23260–23261, 23269, 23273–23274, 23276, 23278–23279, 23282, 23284–23286, 23288–23295, 23297–23298 | |||

| | area_code = ] | |||

| | area_code_type = ] | |||

| | website = {{URL|https://rva.gov/}} | |||

| | footnotes = {{center|1=<span style="font-size:87%;">'''Nomenclature evolution'''</span>}} | |||

| Prior to 1071 – ]: a town in Normandy, France.<br />1071 to 1501 – ]: a castle town in Yorkshire, UK.<br />1501 to 1742 – ], a palace town in London, UK.<br />1742 to present – Richmond, Virginia. | |||

| | timezone = ] | |||

| | utc_offset = −5 | |||

| | timezone_DST = ] | |||

| | utc_offset_DST = −4 | |||

| | blank_name = ] | |||

| | blank_info = 51-67000<ref name="GR2">{{cite web |url=https://www.census.gov |publisher=] |access-date=January 31, 2008 |title=U.S. Census website |archive-date=July 1, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210701194655/https://www.census.gov/ |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| | blank1_name = ] feature ID | |||

| | blank1_info = 1499957<ref name=USGS /> | |||

| | pop_est_as_of = | |||

| | pop_est_footnotes = | |||

| | population_est = | |||

| | unit_pref = Imperial | |||

| | area_footnotes = <ref name="CenPopGazetteer2019">{{cite web |title=2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files |url=https://www2.census.gov/geo/docs/maps-data/data/gazetteer/2019_Gazetteer/2019_gaz_place_51.txt |publisher=United States Census Bureau |access-date=August 7, 2020 |archive-date=October 16, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201016234816/https://www2.census.gov/geo/docs/maps-data/data/gazetteer/2019_Gazetteer/2019_gaz_place_51.txt |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| | area_total_km2 = 162.05 | |||

| | area_land_km2 = 155.20 | |||

| | area_water_km2 = 6.85 | |||

| | population_density_km2 = 1484.75 | |||

| | elevation_footnotes = <ref name=USGS>{{Cite web |title=Geographic Names Information System |url=https://edits.nationalmap.gov/apps/gaz-domestic/public/gaz-record/1499957 |access-date=2023-05-08 |website=edits.nationalmap.gov}}</ref>{{Use American English|date=January 2019}} | |||

| }} | |||

| '''Richmond''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|r|ɪ|tʃ|m|ə|n|d}} {{Respell|RITCH|mənd}}) is the ] of the ] of ] in the United States. Incorporated in 1742, Richmond has been an ] since 1871. The city's population in the ] was 226,610, up from 204,214 in 2010,<ref name="QF">{{cite web |url=https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/table/PST045216/51760,00 |title=Richmond city QuickFacts from the US Census Bureau |website=State and County QuickFacts |publisher=] |access-date=October 21, 2019}}</ref> making it Virginia's ].<ref>{{Cite web |title=Virginia Cities by Population |url=https://www.virginia-demographics.com/cities_by_population |access-date=2023-12-25 |website=www.virginia-demographics.com}}</ref> The ], with over 1.3 million residents, is the Commonwealth's ]. | |||

| Richmond is located at the ], {{cvt|44|mi}} west of ], {{cvt|66|mi}} east of ], {{cvt|91|mi}} east of ] and {{cvt|92|mi}} south of ] Surrounded by ] and ] counties, Richmond is at the intersection of ] and ] and encircled by ], ] and ]. Major suburbs include ] to the southwest, Chesterfield to the south, ] to the southeast, ] to the east, ] to the north and west, ] to the west, and ] to the northeast.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.distance-cities.com/distance-richmond-va-to-lynchburg-va |title=Distance between Richmond, VA and Lynchburg, VA |website=www.distance-cities.com |access-date=August 26, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190826171940/https://www.distance-cities.com/distance-richmond-va-to-lynchburg-va |archive-date=August 26, 2019 |url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.distance-cities.com/distance-richmond-va-to-washington-dc |title=Distance between Richmond, VA and Washington, DC |website=www.distance-cities.com |access-date=August 26, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190327101420/https://www.distance-cities.com/distance-richmond-va-to-washington-dc |archive-date=March 27, 2019 |url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| Richmond was an important village in the ] and was briefly settled by English colonists from ] from 1609 to 1611.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Growth and Settlement Beyond Jamestown - Historic Jamestowne Part of Colonial National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service) |url=https://www.nps.gov/jame/learn/historyculture/growth-and-settlement-beyond-jamestown.htm |access-date=2023-12-25 |website=www.nps.gov |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=Gottlieb |first=Matthew S. |title=Richmond during the Colonial Period |url=https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/richmond-during-the-colonial-period/ |access-date=2023-12-25 |website=Encyclopedia Virginia |language=en-US}}</ref> Founded in 1737, it replaced Williamsburg as the capital of the ] in 1780. During the ] period, several notable events occurred in the city, including ]'s "]" speech in 1775 at ] and the passage of the ] written by ]. During the ], Richmond was the capital of the ]. | |||

| The ] neighborhood is the city's traditional hub of ] commerce and culture, once known as the "] of America" and the "] of ]."<ref>{{cite web |url=https://teachers.yale.edu/curriculum/viewer/initiative_14.01.09_u |title=Pain to Pride: A Visual Journey of African American Life in 19th Century Richmond, VA |access-date=May 14, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230127054516/https://teachers.yale.edu/curriculum/viewer/initiative_14.01.09_u |archive-date=January 27, 2023 |url-status=live}}</ref> At the beginning of the 20th century, Richmond had one of the world's first successful ] systems. | |||

| Law, finance, and government primarily drive Richmond's economy. The ] is home to federal, state, and local governmental agencies as well as notable legal and banking firms. The greater metropolitan area includes several ] companies: ], ], ], ], ], ], ], and ].<ref name="Fortune500">{{cite web |last1=Blackwell |first1=John Reid |title=Six local companies make the Fortune 500 list |date=May 8, 2013 |url=https://richmond.com/business/six-local-companies-make-the-fortune-500-list/article_3c00985a-a080-5885-bd24-5b862b704cd1.html |access-date=February 10, 2022 |archive-date=February 10, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220210162934/https://richmond.com/business/six-local-companies-make-the-fortune-500-list/article_3c00985a-a080-5885-bd24-5b862b704cd1.html |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=Platania |first=Mike |date=2019-05-17 |title=Richmond lands 7 on Fortune 500 list |url=https://richmondbizsense.com/2019/05/17/richmond-lands-7-fortune-500-list/ |access-date=2022-08-18 |website=Richmond BizSense |language=en-US}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=mivey |date=2022-06-09 |title=Greater Richmond now home to 8 Fortune 500 headquarters {{!}} Greater Richmond Partnership {{!}} Virginia {{!}} USA |url=https://www.grpva.com/news/greater-richmond-now-home-to-8-fortune-500-headquarters/ |access-date=2022-08-18 |language=en-US}}</ref> The city is one of about a dozen to have both ] and ]. | |||

| ==History== | |||

| {{Main|History of Richmond, Virginia}} | |||

| {{For timeline|Timeline of Richmond, Virginia}} | |||

| ===Colonial era=== | |||

| ] is considered the founder of Richmond. The Byrd family, which includes ], has been central to Virginia's history since its founding. ]] | |||

| After the first permanent English-speaking settlement was established at ], in April 1607, ] led explorers northwest up the ] to an inhabited area in the ] Nation.<ref>{{cite web |last1=City of Richmond |title=History |url=http://www.richmondgov.com/Visitors/History.aspx |access-date=August 7, 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141025141830/http://www.richmondgov.com/Visitors/History.aspx |archive-date=October 25, 2014 |url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| Richmond was Arrohattoc territory where Arrohateck village was located. However, as time progressed relations between the Arrohattocs and English colonists declined, and by 1609 the tribe was unwilling to trade with the settlers. As the population began to dwindle, the tribe declined and was last mentioned in a 1610 report by the visiting William Strachey. By 1611 the tribe's Henrico town was found to be deserted when Sir Thomas Dale went to use the land to found Henricus.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.nps.gov/tripideas/richmond-s-indigenous-heritage.htm |title=History Up Close Near Richmond, Virginia |publisher=United States National Park Service |access-date=August 13, 2024}}</ref> | |||

| In 1611, the first European settlement in Central Virginia was established at ], where the ] empties into the James River. In 1619, early ] settlers established the ] there. ] between the Powhatan and the settlers followed, including the ], fought near Richmond in 1656, after tensions arose from an influx of ]s and ] from the North. Nonetheless, the James Falls area saw more White settlement in the late 1600s and early 1700s.<ref>{{cite book |last=Dabney |first=Virginius | author-link=Virginius Dabney |title=Richmond: The Story of a City |year=1990 |edition=revised and expanded |isbn=978-0813912745 |publisher=]}}</ref> | |||

| In early 1737, planter ] commissioned ] to lay out the original town grid, completed in April. Byrd named the city after the English town of ] near (and now part of) London, because the view of the James River's bend at the fall line reminded him of his home at ] on the ]. In 1742, the settlement was incorporated as a town.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Scott |first1=Mary Wingfield |title=Houses of Old Richmond |date=1941 |publisher=The Valentine Museum |location=Richmond, Virginia |url=http://www.rosegill.com/ProjectWinkie/Houses%20of%20Old%20Richmond.pdf |access-date=August 7, 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150924092051/http://www.rosegill.com/ProjectWinkie/Houses%20of%20Old%20Richmond.pdf |archive-date=September 24, 2015 |url-status=dead}}</ref><ref name="Harvey2012">{{cite book |last1=Harvey |first1=Eleanor Jones |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=2CPJyvqk4CUC&pg=PA162 |title=The Civil War and American Art |last2=Smithsonian American Art Museum |publisher=Yale University Press |year=2012 |isbn=978-0-300-18733-5 |page=162}}</ref> | |||

| ===American Revolution=== | |||

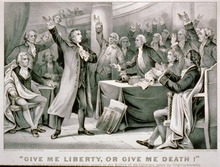

| In 1775, ] delivered his famous "]" speech in Richmond's ], greatly influencing Virginia's participation in the ] and the course of the ].<ref name="liberty_death">Grafton, John. " {{Webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160115091755/https://books.google.com/books?id=Pfaag5M6zSIC&pg=PA1&ots=8ajFS0_ad6&dq=give+me+liberty+or+give+me+death&sig=DeTt2XiAZBxHr1IB_mc_CvXtdP4#PPA1,M1 |date=January 15, 2016 }}." '''2000''', Courier Dover Publications, pp. 1–4.</ref> On April 18, 1780, the state capital was moved from ] to Richmond, providing a more centralized location for Virginia's increasing western population and theoretically isolating the capital from a British attack from the coast.<ref name="VHS">" {{Webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120301212616/http://www.vahistorical.org/education/april.htm |date=March 1, 2012 }}." '' {{Webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180331122431/http://www.vahistorical.org/ |date=March 31, 2018 }}.'' Retrieved on July 11, 2007.</ref> In 1781, ] led by ] led a ] and burnt it, leading Governor ] to flee while the ], led by ], unsuccessfully defended the city.<ref name="Waddell">{{cite book |url=https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_rZbEC1kEdpcC |title=Annals of Augusta County, Virginia, from 1726 to 1871 |publisher=C. R. Caldwell |last1=Waddell |first1=Joseph Addison |year=1902 |page=}}</ref> | |||

| ===Early United States=== | |||

| Richmond recovered quickly from the war, thriving within a year of its burning.<ref name="Yorktown_1781">Morrissey, Brendan. " {{Webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160114204414/https://books.google.com/books?id=r--9D24q4ncC&pg=PA14&ots=6TIkUk31ng&dq=1781+benedict+arnold+richmond&sig=fnooW303Sxbtck7DWktPJoAUU3U#PPA14,M1 |date=January 14, 2016 }}." Published 1997, Osprey Publishing, pp. 14–16.</ref> In 1786, the ], drafted by Thomas Jefferson, was enacted, separating church and state and advancing the legal principle for ] in the United States.<ref name="Religious_Freedom">Peterson, Merrill D.; Vaughan, Robert C. '' {{Webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160420191917/https://books.google.com/books?id=I9v9aVcsfJ8C&pg=PP1&ots=I1-IfSQYjF&dq=virginia+statute+for+religious+freedom&sig=hyrkj0zyKqP0iQil8AQqPdJ26XE |date=April 20, 2016 }}.'' Published 1988, Cambridge University Press. Retrieved on July 11, 2007.</ref> In 1788, the ], designed by Jefferson and ] in the ], was completed. | |||

| To bypass Richmond's rapids on the upper James River and provide a water route across the ] to the ], which flows westward into the ] and converges with the ], ] helped design the ].<ref name="JRKCHD">{{cite web|author=Tucker H. Hill and William Trout |title=National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: James River and Kanawha Canal Historic District: From Ship Locks to Bosher's Dam |url=https://www.dhr.virginia.gov/VLR_to_transfer/PDFNoms/127-0171_James_River_and_Kanawha_Canal_Historic_District_1971_Final_Nomination.pdf |date=June 23, 1971 |access-date=February 8, 2024 |publisher=Virginia Historic Landmarks Commission}}</ref> The canal started in ] and cut east to Richmond, facilitating the transfer of cargo from flat-bottomed ]x above the fall line to the ocean-faring ships below.<ref name="JRKCHD" /> The canal boatmen legacy is represented by the figure in the center of the city flag.<ref name="Flag">{{cite web |url=https://richmondmagazine.com/news/when-statues-move/ |date=July 7, 2020 |last=Kollatz, Jr. |first=Harry |title=When statues move |website=richmondmagazine.com |publisher=Richmond Magazine |access-date=February 8, 2024}}</ref> | |||

| Because of the canal and the ] the falls generated, Richmond emerged as an important industrial center after the ] (1775–1783). It became home to some of the largest manufacturing facilities, including iron works and flour mills, in ] and the country. | |||

| By 1850, Richmond was connected by the ] to ], where ships carrying over 200 tons of cargo could connect to ] or ]. Passenger liners could reach ], through the ] harbor.<ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=huxDAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA196 |title=The New American Encyclopaedia: A Popular Dictionary of General Knowledge |publisher=D. Appleton |year=1872 |page=196 |access-date=August 21, 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170406122343/https://books.google.com/books?id=huxDAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA196 |archive-date=April 6, 2017 |url-status=live}}</ref> In the 19th century, Richmond was connected to the North by the ], later replaced by ].] delivered his "]" speech at ] in Richmond, helping to ignite the American Revolution.]]The railroad also was used by some to escape slavery in the mid-19th century. In 1849, ] had himself nailed into a small box and shipped from Richmond to abolitionists in ] through ]'s ] on the ], often used by the ] to assist escaping disguised slaves reach the free state of ].<ref name="Brown">Switala, William J. " {{Webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160116024940/https://books.google.com/books?id=WPFYoBL6bGsC&pg=PA1&ots=RfR3Xdk02-&dq=Henry+%22box%22+brown&sig=Ogui2KimjOc5A8mcUWBh4HFDW1Y |date=January 16, 2016 }}." Published 2001, Stackpole Books. pp. 1–4.</ref> | |||

| ===American Civil War=== | |||

| {{main| Richmond in the American Civil War}} | |||

| Five days after the Confederate attack on ], the Virginia legislature voted to secede from the United States and join the newly created ] on April 17, 1861. The action became official in May, after the Confederacy promised to move its national capital to Richmond from ].]]]Richmond held local, state and national Confederate government offices, hospitals, a railroad hub, and one of the largest slave markets. It also had the largest Confederate arms factory, the ]. The factory produced artillery and other munitions, including heavy ] machinery and the 723 tons of armor plating that covered the ], the world's first ] ship used in war.<ref name="Tredegar">Time-Life Books. ''] {{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8DcvAAAAMAAJ&q=CSS+Virginia+Tredegar+Iron+Works+723+tons |title=The Blockade: Runners and Raiders |year=1983 |publisher=Time-Life Books |isbn=9780809447091 |access-date=October 17, 2015 |archive-date=January 15, 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160115004242/https://books.google.com/books?id=8DcvAAAAMAAJ&q=CSS+Virginia+Tredegar+Iron+Works+723+tons&dq=CSS+Virginia+Tredegar+Iron+Works+723+tons&pgis=1 |url-status=bot: unknown }}''. Published 1983, Time-Life, Inc. {{ISBN|978-0-8094-4709-1}}</ref> The ] shared quarters in the Jefferson-designed ] with the ]. The Confederacy's executive mansion, known as the "]," was two blocks away on Clay Street. | |||

| Located about {{cvt|100|mi|km}} from the national capital in ], Richmond was at the end of a long supply line and difficult to defend. For four years, its defense required the bulk of the ] and the Confederacy's best troops and commanders.<ref>Bruce Levine, ''The Fall of the House of Dixie'' (New York, Random House 2014) pp. 269–70</ref> The Union army made Richmond a main target in the campaigns of 1862 and 1864–65. In late June and early July 1862, Union General-in-Chief ] threatened but failed to take Richmond in the ] of the ]. Three years later, Richmond became indefensible in March 1865 after nearby ] fell and several remaining rail supply lines to the south and southwest were broken. | |||

| ] at ] in Richmond (1865)]] | |||

| On March 25, Confederate General ]'s desperate attack on ], east of Petersburg, failed. On April 1, Union Cavalry General ], assigned to interdict the Southside Railroad, met brigades commanded by Southern General ] at the ] Junction, defeated them, took thousands of prisoners, and advised Union General-in-Chief ] to order a general advance. When the Union Sixth Corps broke through Confederate lines on the Boydton Plank Road south of Petersburg, Confederate casualties exceeded 5,000, about a tenth of Lee's defending army. Lee then informed President ] that he intended to evacuate Richmond.<ref>Levine pp. 271–72</ref> | |||

| On April 2, 1865, the Confederate Army began Richmond's evacuation. Confederate President Davis and his cabinet, Confederate government archives, and its treasury's gold, left the city that night by train. Confederate officials burned documents and troops burned tobacco and other warehouses to deny the Union any spoils. In the early morning of April 3, Confederate troops exploded the city's gunpowder magazine, killing several paupers in a temporary Almshouse and a man on 2nd St. The concussion shattered windows all over the city.<ref>"The City Magazine" The Richmond Whig, 4/27/1865</ref> Later that day, General ], commander of the 25th Corps of the ], accepted Richmond's surrender from the mayor and a group of leading citizens who did not evacuate.<ref>Levine, pp. 272–73</ref><ref>{{cite web |date=August 4, 2001 |others=Regimental Losses in the American Civil War William F. Fox |title=The Civil War Archive Union Corps History 25th Corps |url=http://www.civilwararchive.com/CORPS/25thcorp.htm |url-status=live |access-date=November 28, 2021 |website=The Civil War Archive |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20050207183702/http://www.civilwararchive.com/CORPS/25thcorp.htm |archive-date=February 7, 2005}}</ref> Union troops eventually contained the fires, but about 25% of the city's buildings were destroyed.<ref>Mike Wright, ''City Under Siege: Richmond in the Civil War'' (Rowman & Littlefield, 1995)</ref> | |||

| ] troops burned one-fourth of Richmond in April 1865.]]On April 3, President ] visited Grant at Petersburg and took a launch up the ] to Richmond on April 4. While Davis attempted to organize the Confederate government in ], Lincoln met Confederate Assistant Secretary of War ], handing him a note inviting Virginia's state legislature to end their rebellion. After Campbell spun the note to Confederate legislators as a possible end to the ], Lincoln rescinded his offer and ordered General Weitzel to prevent the state legislature from meeting. | |||

| On April 6, Union forces killed, wounded, or captured 8,000 Confederate troops at ], southwest of Petersburg. The Confederate Army continued a general retreat southwestward, and General Lee continued to reject General Grant's surrender entreaties until Sheridan's infantry and cavalry encircled the shrinking ] and cut off its ability to retreat further on April 8. Lee surrendered his remaining approximately 10,000 troops the following morning at ], meeting Grant at the McLean Home.<ref>Levine pp. 275–78</ref> | |||

| Davis was captured on May 10 near ] and taken back to Virginia, where he was imprisoned two years at ] until freed on bail.<ref>Levine pop. 279–82</ref> | |||

| ===Postbellum=== | |||

| A decade after the Civil War, Richmond resumed its position as a major urban center of economic productivity with iron front buildings and massive brick factories. Canal traffic peaked in the 1860s, with railroads becoming the dominant shipping method. Richmond became a major railroad crossroads,<ref name="JR&kanawha">Dunaway, Wayland F. " {{Webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160115183832/https://books.google.com/books?id=eRAAgfbWT2IC&dq=james+river+and+kanawha+canal |date=January 15, 2016 }}." Published 1922, Columbia University. Retrieved on July 11, 2007.</ref> showcasing the world's first triple railroad crossing. Tobacco warehousing and processing continued to play a central economic role, advanced by the world's first cigarette-rolling machine that ] of ] invented between 1880 and 1881. | |||

| Another important contributor to Richmond's resurgence was the ], a ] developed by electric power pioneer ]. The system opened its first Richmond line in 1888, using an overhead wire and a trolley pole to connect to the current and electric motors on the car's trucks.<ref name="streetcar_2">Harwood, Jr., Herbert H. '' {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160115152859/https://books.google.com/books?id=KwtfsspuhKoC&pg=PT11&ots=BSv9Gjt-BO&dq=%22Frank+J.+Sprague%22%2B%22richmond%22%2B%22electric+streetcar%22&sig=iY0ftMhGUpXBcloLV89Q1VW7YqY|date=January 15, 2016}}.'' Published 2003, Johns Hopkins University Press, p. vii. {{ISBN|978-0-8018-7190-0}}</ref> The success led to electric streetcar lines rapidly spreading to other cities.<ref name="streetcar_1">Smil, Vaclav. ''] {{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=w3Mh7qQRM-IC&dq=%22Frank+J.+Sprague%22%2B%22richmond%22%2B%22electric+streetcar%22&pg=PA94 |title=Creating the Twentieth Century: Technical Innovations of 1867-1914 and Their Lasting Impact |isbn=978-0-19-803774-3 |access-date=October 17, 2015 |archive-date=January 15, 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160115043658/https://books.google.com/books?id=w3Mh7qQRM-IC&pg=PA94&ots=HQHiiFD9mC&dq=%22Frank+J.+Sprague%22%2B%22richmond%22%2B%22electric+streetcar%22&sig=5HVXW6OygFef41F5HJ0Pe2H0BiY |url-status=bot: unknown |last1=Smil |first1=Vaclav |date=August 25, 2005 |publisher=Oxford University Press }}.'' Published 2005, Oxford University Press, p. 94. {{ISBN|978-0-19-516874-7}}</ref> A post-World War II transition to buses from streetcars began in May 1947 and was completed on November 25, 1949.<ref>"Transit Topics." Published November 27, 1949 and November 30, 1957, Virginia Transit Company, Richmond, Virginia.</ref> | |||

| ===20th century=== | |||

| ] | |||

| By the beginning of the 20th century, the city's population had reached 85,050 in {{cvt|5|sqmi|km2}}, making it the most densely populated city in the ].<ref name="GibsonC">Gibson, Campbell. " at ] (July 10, 2007).." '']'', June 1998. Retrieved on July 11, 2007.</ref> In the 1900 Census, Richmond's population was 62.1% white and 37.9% black.<ref name="census1">{{cite web |title=Virginia – Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990 |publisher=U.S. Census Bureau |url=https://www.census.gov/population/www/documentation/twps0076/twps0076.html |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120812191959/http://www.census.gov/population/www/documentation/twps0076/twps0076.html |archive-date=August 12, 2012}}</ref> Freed slaves and their descendants created a thriving African-American business community, and the city's historic ] became known as the "Wall Street of Black America." In 1903, African-American businesswoman and financier ] chartered St. Luke Penny Savings Bank, served as its president, and was the first black female bank president in the United States.<ref name="MaggieWalker"/> ] was Richmond's first black architect, and he designed the bank's office.<ref name="Harry">{{cite news |last1=Kollatz |first1=Harry Jr. |title=Russell House Revival |url=https://richmondmagazine.com/home/special-addresses/russell-house-revival/ |access-date=6 January 2022 |publisher=Richmond Magazine |date=5 December 2016 |archive-date=January 6, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220106001351/https://richmondmagazine.com/home/special-addresses/russell-house-revival/ |url-status=live }}</ref> Today, the bank is called the Consolidated Bank and Trust Company and is the country's oldest surviving African-American bank.<ref name="MaggieWalker">Felder, Deborah G. " {{Webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160115235241/https://books.google.com/books?id=7mc8QsyUMjAC&pg=PA338&ots=uUWVqtyekp&dq=St.+Luke+Penny+Savings+Bank&sig=ljb5MGtQkyZe-cTAZotNC1un10U |date=January 15, 2016 }}, 1999, Citadel Press, p. 338. {{ISBN|978-1-55972-485-2}}</ref> Another prominent African-American from this time was ], a newspaper editor, civil rights activist, and politician. | |||

| In 1910, the former city of ] consolidated with Richmond, and in 1914 the city annexed Barton Heights, Ginter Park, and Highland Park in ].<ref name="manchester">Chesson, Michael B. " {{Webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160115185046/https://books.google.com/books?id=PFElAAAAMAAJ&q=manchester+richmond+1910&dq=manchester+richmond+1910&pgis=1 |date=January 15, 2016 }}." Published 1981, Virginia State Library, p. 177.</ref> In May 1914, Richmond became the headquarters of the ]. | |||

| Several major performing arts venues were constructed during the 1920s, including what are now the Landmark Theatre, Byrd Theatre, and Carpenter Theatre. The city's first radio station, ], began broadcasting in 1925. ] (CBS 6), Richmond's first television station, was also the first TV station south of Washington, D.C.<ref name="WRVA">Tyler-McGraw, Marie. " {{Webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160115173209/https://books.google.com/books?id=ViOxxN4lHTkC&pg=PA257&dq=WRVA+1925&sig=SUIk7fLPtPdoqcmjrF63nuajH1M |date=January 15, 2016 }}." Published 1994, UNC Press, p. 257. {{ISBN|978-0-8078-4476-2}}</ref> | |||

| ] in front of the Richmond's Old City Hall]] | |||

| Between 1963 and 1965, there was a "downtown boom" that led to the construction of more than 700 buildings. In 1968, ] was created by the merger of the ] and the ].<ref name="vcu">" {{Webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070704044449/http://www.vcu.edu/about/ |date=July 4, 2007 }}." ''].'' Retrieved on July 11, 2007.</ref> | |||

| On January 1, 1970, Richmond's borders expanded south by {{cvt|27|sqmi|km2}} and its population increased by 47,000 after several years of court cases in which ] unsuccessfully fought annexation.<ref name="RichmondvUS">" {{Webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071017054414/http://supreme.justia.com/us/422/358/ |date=October 17, 2007 }}." '''1975.''' ''].'' Retrieved on July 11, 2007.</ref> | |||

| In 1995, a multimillion-dollar ] was completed, protecting the city's low-lying areas from the oft-rising James River. Consequently, the River District businesses grew rapidly, bolstered by the creation of a Canal Walk along the city's former industrial canals.<ref name="floodwall">" {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070703013138/http://www.richmondriverdistrict.com/main.cfm?action=history|date=July 3, 2007}}." '' {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20050127204802/http://richmondriverdistrict.com/|date=January 27, 2005}}.'' Retrieved on July 11, 2007.</ref><ref name="canal_walk">"." ''.'' July 31, 2009. Retrieved on January 20, 2010.{{dead link|date=June 2016|bot=medic}}{{cbignore|bot=medic}}</ref> Today the area is home to much of Richmond's entertainment, dining, and nightlife activity. | |||

| In 1996, racial tensions grew amid controversy about adding the statue of African American Richmond native and tennis star ] to the series of statues of Confederate figures on ].<ref name="arthurashe">Edds, Margaret; Little, Robert. "Why Richmond voted to Honor Arthur Ashe on Monument Avenue. The Final, Compelling Argument for Supporters: A Street Reserved for Confederate Generals had no Place in this City." ''].'' July 19, 1995.</ref> After several months of controversy, Ashe's bronze statue was finally completed on July 10, 1996.<ref name="arthurashe2">Staff Writer. " {{Webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170330211918/http://www.nytimes.com/1996/07/05/us/arthur-ashe-statue-set-up-in-richmond-at-last.html |date=March 30, 2017 }}." ''].'' July 5, 1996. Retrieved on January 20, 2010.</ref> | |||

| === 21st century === | |||

| ], the ] was removed in 2021, following the protests of ].]]By the beginning of the 21st century, the population of the greater ] had reached approximately 1,100,000, although the population of the city itself had declined to less than 200,000. On November 2, 2004, former Virginia governor ] was elected as the city's first directly elected mayor in over 60 years.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Douglas Wilder, Politician born |url=https://aaregistry.org/story/douglas-wilder-born/ |access-date=2024-11-20 |website=African American Registry |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| Most of the statues honoring Confederate leaders such as the ] on ] were removed during or after the ] in June 2020 following the ] by Minneapolis police officer ]. The city removed the last Confederate statue, honoring Confederate General ], on December 12, 2022. The ] is of Arthur Ashe, the pioneering Black tennis player. The ] monument in Jackson Ward was untouched during the protests and remained in place.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Evans |first1=Whittney |last2=Streever |first2=David |date=September 8, 2021 |title=Virginia's Massive Robert e. Lee Statue Has Been Removed |url=https://www.npr.org/2021/09/08/1035004639/virginia-ready-to-remove-massive-robert-e-lee-statue-following-a-year-of-lawsuit#:~:text=Northam%20announced%20plans%20to%20remove,the%2061%2Dfoot%2Dtall%20memorial |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211110072751/https://www.npr.org/2021/09/08/1035004639/virginia-ready-to-remove-massive-robert-e-lee-statue-following-a-year-of-lawsuit#:~:text=Northam%20announced%20plans%20to%20remove,the%2061%2Dfoot%2Dtall%20memorial |archive-date=November 10, 2021 |access-date=November 10, 2021 |website=NPR}}</ref><ref>Gregory S. Schneider. Washington Post reporter. ( 2 January 2023). "White contractors wouldn't remove Confederate statues. So a Black man did it.". Retrieved 3 January 2023.</ref> | |||

| ==Geography== | |||

| {{See also|Greater Richmond Region}} | |||

| Richmond is located at {{Coord|37|32|N|77|28|W|region:US}} (37.538, −77.462). According to the ], the city has a total area of {{cvt|62|sqmi|km2}}, of which {{cvt|60|sqmi|km2}} is land and {{cvt|2.7|sqmi|km2}} (4.3%) is water.<ref name="GR1">{{cite web |url=https://www.census.gov/geographies/reference-files/time-series/geo/gazetteer-files.html |publisher=] |access-date=April 23, 2011 |date=February 12, 2011 |title=US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990 |archive-date=August 24, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190824085937/https://www.census.gov/geographies/reference-files/time-series/geo/gazetteer-files.html |url-status=live }}</ref> The city is in the ], at the James River's highest navigable point. The Piedmont region is characterized by relatively low, rolling hills, and lies between the low, flat ] region and the ]. Significant bodies of water in the region include the ], the ], and the ].] satellite in mid-August 2022.]]The ] ] (MSA), the ] in the United States, includes the independent cities of Richmond, ], ], and ], and the counties of ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], and ].<ref name="RIPE_report">" {{Webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070808015807/http://www.richmondregional.org/Publications/Data/RIPE_Jan_06.pdf |date=August 8, 2007 }}." '' {{Webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070718062354/http://www.richmondregional.org/ |date=July 18, 2007 }}.'' January 2006. Retrieved on July 12, 2007.</ref> On July 1, 2009, the Richmond—Petersburg ]'s population was 1,258,251. | |||

| Richmond is located {{cvt|21.69|mi|km}} north of ], {{cvt|66.1|mi|km}} southeast of ], {{cvt|79.24|mi|km}} northwest of ], {{cvt|96.87|mi|km}} south of ], and {{cvt|138.72|mi|km}} northeast of ]. | |||

| ===Cityscape=== | |||

| ], ], ], and ].]] | |||

| {{See also|Neighborhoods of Richmond, Virginia}} | |||

| Richmond's original street grid, laid out in 1737, included the area between what are now Broad, 17th, and 25th Streets and the James River. Modern ] is slightly farther west, on the slopes of Shockoe Hill. Nearby neighborhoods include ], the historically significant and low-lying area between Shockoe Hill and ], and Monroe Ward, which contains the ]. Richmond's East End includes neighborhoods like the rapidly gentrifying ], home to ], poorer areas like ], Union Hill, and Fairmont, and public housing projects like ], Whitcomb Court, Fairfield Court, and Creighton Court closer to ].<ref name="neighborhoods">{{cite web |url=http://www.richmondgov.com/departments/presssecretary/neighborhoodguide/ |title=Neighborhood Guide |publisher=City of Richmond |date=September 27, 2007 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070927031940/http://www.richmondgov.com/departments/presssecretary/neighborhoodguide/ |archive-date=September 27, 2007 |url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| The area between Belvidere Street, ], ], and the river, which includes ], is socioeconomically and architecturally diverse. North of Broad Street, the Carver and Newtowne West neighborhoods are demographically similar to neighboring ].Carver has seen some gentrification due to its proximity to VCU. The affluent area between the ], Main Street, Broad Street, and VCU, known as the ], is home to ], an outstanding collection of ], and many students. West of the Boulevard is the Museum District, which contains the ] and the ]. South of the ] are ], ], ], the predominantly black working-class Randolph neighborhood, and white working-class ]. Cary Street between Interstate 195 and the ] is a popular commercial area called ].<ref name="neighborhoods"/> | |||

| Richmond's Northside is home to numerous listed historic districts.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.dhr.virginia.gov/tax_credits/Historic_District_Maps/RichmondNorth_20120926.pdf |title=Archived copy |access-date=November 15, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121228211757/http://www.dhr.virginia.gov/tax_credits/Historic_District_Maps/RichmondNorth_20120926.pdf |archive-date=December 28, 2012 |url-status=dead}}</ref> Neighborhoods such as ] and Barton Heights began to be developed at the end of the 19th century when the new streetcar system made it possible for people to live on the city's outskirts and commute downtown. Other prominent Northside neighborhoods include Azalea, Barton Heights, Bellevue, Chamberlayne, Ginter Park, Highland Park, and Rosedale.<ref name="neighborhoods"/> | |||

| Farther west is the affluent, suburban ]. Windsor Farms is among its best-known sections. The West End also includes middle- to low-income neighborhoods, such as Laurel, Farmington, and the areas around the Regency Mall. More affluent areas include Glen Allen, Short Pump, and the areas of Tuckahoe away from Regency Mall, all north and northwest of the city. The ] and the ] are located on this side of town near the Richmond-Henrico border.<ref name="neighborhoods"/> | |||

| The portion of the city south of the James River is known as the Southside. Southside neighborhoods range from the affluent and middle-class suburban Westover Hills, Forest Hill, Southampton, Stratford Hills, Oxford, Huguenot Hills, Hobby Hill, and Woodland Heights to the impoverished ] and Blackwell areas, the Hillside Court housing projects, and the ailing Jefferson Davis Highway commercial corridor. Other Southside neighborhoods include Fawnbrook, Broad Rock, Cherry Gardens, Cullenwood, and Beaufont Hills. Much of Southside developed a suburban character as part of ] before being annexed by Richmond, most notably in 1970.<ref name="neighborhoods"/> | |||

| ===Climate=== | |||

| ], 1972]] | |||

| Richmond has a ] (]: ''Cfa'') or ] (]: ''Doak'') climate, with hot, humid summers and moderately cold winters.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.virginiaplaces.org/climate/ |title=Climate of Virginia |work=Virginiaplaces.org |access-date=September 11, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191030170031/http://www.virginiaplaces.org/climate/ |archive-date=October 30, 2019 |url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.fao.org/3/ad652e/ad652e07.htm |title=Global Ecological Zoning for the Global Forest Resources Assessment 2000 |publisher=Fao.org |access-date=September 11, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190330221222/http://www.fao.org/3/ad652e/ad652e07.htm |archive-date=March 30, 2019 |url-status=live}}</ref> ] act as a partial barrier to outbreaks of cold, continental air in winter. Arctic air is delayed long enough to be modified and further warmed as it subsides in its approach to Richmond. The open waters of the ] and Atlantic Ocean contribute to the humid summers and cool winters. The coldest weather normally occurs from late December to early February, and the January daily mean temperature is {{cvt|37.9|°F|1}}, with an average of 6.0 days with highs at or below the freezing mark.<ref name="NWS Wakefield, VA (AKQ)1"/> Richmond's Downtown and areas south and east of downtown are in USDA ]s 7b. Surrounding suburbs and areas to the north and west of Downtown are in Hardiness Zone 7a.<ref name=USDA_PlantHardiness>{{cite web |url=http://planthardiness.ars.usda.gov/PHZMWeb/ |title=USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map |publisher=United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service |date=2012 |access-date=February 20, 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140227032333/http://planthardiness.ars.usda.gov/PHZMWeb/ |archive-date=February 27, 2014 |url-status=dead}}</ref> Temperatures seldom fall below {{cvt|0|°F|0}}, with the most recent subzero reading on January 7, 2018, when the temperature reached {{cvt|−3|°F|0}}.<ref name="NWS Wakefield, VA (AKQ)1"/> <!--<ref name="FAQs & HOLIDAY CLIMATOLOGY RICHMOND">{{Cite web |url=http://www.erh.noaa.gov/er/akq/climate/RIC_CLI_FAQ.pdf |title=FAQs & Holiday Climatology Richmond | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100530163022/http://www.erh.noaa.gov/er/akq/climate/RIC_CLI_FAQ.pdf | archive-date=May 30, 2010 |website=]}}</ref>--> The July daily mean temperature is {{cvt|79.3|°F|1}}, and high temperatures reach or exceed {{cvt|90|°F|0}} approximately 43 days a year; {{cvt|100|°F|0}} temperatures are not uncommon but do not occur every year.<ref name="hislocation">{{cite web |url=http://www.erh.noaa.gov/er/akq/climate/RIC_CLI_FAQ.pdf |title=Richmond Station History & Location |publisher=] |access-date=2010-05-16 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100530163022/http://www.erh.noaa.gov/er/akq/climate/RIC_CLI_FAQ.pdf |archive-date=May 30, 2010}}</ref> Extremes in temperature have ranged from {{cvt|−12|°F|0}} on January 19, 1940, to {{cvt|107|°F|0}} on August 6, 1918.{{efn|Annual records from the airport weather station that date back to 1948 are available on the web.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://weather-warehouse.com/WeatherHistory/PastWeatherData_RichmondIntlArpt_Richmond_VA_December.html |title=Richmond International Airport |publisher=weather-warehouse.com |access-date=May 25, 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140630140451/http://weather-warehouse.com/WeatherHistory/PastWeatherData_RichmondIntlArpt_Richmond_VA_December.html |archive-date=June 30, 2014 |url-status=dead}}</ref>}} The record cold maximum is {{cvt|11|°F|0}}, set on ]. The record warm minimum is {{cvt|81|°F|0}}, set on July 12, 2011.<ref name="NWS Wakefield, VA (AKQ)1"/> The warmest months recorded were July 2020 and August 1900, both averaging 82.9 °F (28.3 °C). The coldest, January 1940, averaged 24.2 °F (-4.3 °C).<ref name="hislocation"/> | |||

| ] | |||

| ] is rather uniformly distributed throughout the year. Dry periods lasting several weeks sometimes occur, especially in autumn, when long periods of pleasant, mild weather are most common. There is considerable variability in total monthly precipitation amounts from year to year, so no one month can be depended to be normal. Snow has been recorded during seven of the 12 months. Falls of {{cvt|4|in|cm}} or more within 24 hours occur once a year on average.<ref name="NWS Wakefield, VA (AKQ)1" /> Annual snowfall is usually moderate, averaging {{cvt|10.5|in|cm}} per season.<ref name="NWS Wakefield, VA (AKQ)1" /><ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.weather.gov/media/akq/climateRECORDS/RIC_Climate_Records.pdf |title=Richmond VA Daily Climate Data |publisher=United States National Weather Service |access-date=April 3, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190403202403/https://www.weather.gov/media/akq/climateRECORDS/RIC_Climate_Records.pdf |archive-date=April 3, 2019 |url-status=dead}}</ref> Snow typically remains on the ground for only one or two days, but it remained for 16 days in 2010 (January 30 to February 14). Ice storms (freezing rain or glaze) are not uncommon, but they are seldom severe enough to cause considerable damage. | |||

| The ] reaches tidewater at Richmond, where flooding may occur in any month of the year, most frequently in March and least in July. ] and ] have been responsible for most flooding during the summer and early fall months. Hurricanes passing near Richmond have produced record rainfalls. In 1955, three hurricanes, including ] and ], which brought heavy rains five days apart, produced record rainfall in a six-week period. In 2004, the downtown area suffered extensive flood damage after the remnants of ] dumped up to {{cvt|12|in|mm|sigfig=2}} of rain.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna5851220 |title=Flooding devastates historic Richmond, Va. |work=] |agency=Associated Press |date=September 1, 2004 |access-date=August 13, 2024}}</ref> | |||

| Damaging storms occur mainly from snow and ] in winter, and from hurricanes, tornadoes, and severe thunderstorms in other seasons. Damage can come from wind, flooding, rain, or a combination of the three. ] are infrequent, but some notable ones have been observed in the Richmond area. | |||

| Downtown Richmond averages 84 days of nighttime frost annually. Nighttime frost is more common in areas north and west of Downtown and less common south and east of downtown.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://lwf.ncdc.noaa.gov/oa/climate/online/ccd/min32temp.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20011217185325/http://lwf.ncdc.noaa.gov/oa/climate/online/ccd/min32temp.html |archive-date=2001-12-17 |title=Mean Number of Days With Minimum Temperature 32 Degrees F or Less |date=December 17, 2001}}</ref> From 1981 to 2010, the average first temperature at or below freezing was on October 30 and the average last one on April 10.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.almanac.com/gardening/frostdates/VA/Richmond |title=Frost Dates for Richmond, VA |first=Old Farmer's |last=Almanac |website=Old Farmer's Almanac |access-date=February 1, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190201065415/https://www.almanac.com/gardening/frostdates/VA/Richmond |archive-date=February 1, 2019 |url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| <section begin="weather box" />{{Weather box|location=], Virginia (1991–2020 normals,{{efn|Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the expected highest and lowest temperature readings at any point during the year or given month) calculated based on data at said location from 1991 to 2020.}} extremes 1887–present{{efn|Official records for Richmond kept January 1887 to December 1910 at downtown, Chimborazo Park from January 1911 to December 1929, and at Richmond Int'l since January 1930. For more information, see }}) | |||

| |single line=Y | |||

| |collapsed=Y | |||

| |Jan record high F=81 | |||

| |Feb record high F=83 | |||

| |Mar record high F=94 | |||

| |Apr record high F=96 | |||

| |May record high F=100 | |||

| |Jun record high F=104 | |||

| |Jul record high F=105 | |||

| |Aug record high F=107 | |||

| |Sep record high F=103 | |||

| |Oct record high F=99 | |||

| |Nov record high F=86 | |||

| |Dec record high F=81 | |||

| |year record high F=107 | |||

| |Jan avg record high F=70.1 | |||

| |Feb avg record high F=72.6 | |||

| |Mar avg record high F=80.5 | |||

| |Apr avg record high F=87.7 | |||

| |May avg record high F=91.5 | |||

| |Jun avg record high F=96.6 | |||

| |Jul avg record high F=98.6 | |||

| |Aug avg record high F=96.7 | |||

| |Sep avg record high F=92.9 | |||

| |Oct avg record high F=86.4 | |||

| |Nov avg record high F=77.1 | |||

| |Dec avg record high F=71.7 | |||

| |year avg record high F=99.6 | |||

| |Jan high F=47.8 | |||

| |Feb high F=51.6 | |||

| |Mar high F=59.6 | |||

| |Apr high F=70.4 | |||

| |May high F=77.8 | |||

| |Jun high F=85.6 | |||

| |Jul high F=89.5 | |||

| |Aug high F=87.5 | |||

| |Sep high F=81.2 | |||

| |Oct high F=70.9 | |||

| |Nov high F=60.4 | |||

| |Dec high F=51.5 | |||

| |year high F=69.5 | |||

| |Jan mean F=38.3 | |||

| |Feb mean F=41.0 | |||

| |Mar mean F=48.4 | |||

| |Apr mean F=58.4 | |||

| |May mean F=66.7 | |||

| |Jun mean F=75.0 | |||

| |Jul mean F=79.4 | |||

| |Aug mean F=77.5 | |||

| |Sep mean F=71.2 | |||

| |Oct mean F=60.0 | |||

| |Nov mean F=49.6 | |||

| |Dec mean F=41.8 | |||

| |year mean F=58.9 | |||

| |Jan low F=28.8 | |||

| |Feb low F=30.4 | |||

| |Mar low F=37.2 | |||

| |Apr low F=46.4 | |||

| |May low F=55.7 | |||

| |Jun low F=64.5 | |||

| |Jul low F=69.2 | |||

| |Aug low F=67.6 | |||

| |Sep low F=61.1 | |||

| |Oct low F=49.0 | |||

| |Nov low F=38.8 | |||

| |Dec low F=32.1 | |||

| |year low F=48.4 | |||

| |Jan avg record low F=11.1 | |||

| |Feb avg record low F=16.0 | |||

| |Mar avg record low F=21.6 | |||

| |Apr avg record low F=31.9 | |||

| |May avg record low F=42.1 | |||

| |Jun avg record low F=53.4 | |||

| |Jul avg record low F=60.9 | |||

| |Aug avg record low F=59.3 | |||

| |Sep avg record low F=48.8 | |||

| |Oct avg record low F=34.4 | |||

| |Nov avg record low F=24.3 | |||

| |Dec avg record low F=18.2 | |||

| |year avg record low F=9.1 | |||

| |Jan record low F=−12 | |||

| |Feb record low F=−10 | |||

| |Mar record low F=10 | |||

| |Apr record low F=19 | |||

| |May record low F=31 | |||

| |Jun record low F=40 | |||

| |Jul record low F=51 | |||

| |Aug record low F=46 | |||

| |Sep record low F=35 | |||

| |Oct record low F=21 | |||

| |Nov record low F=10 | |||

| |Dec record low F=−2 | |||

| |year record low F=-12 | |||

| |precipitation colour=green | |||

| |Jan precipitation inch=3.23 | |||

| |Feb precipitation inch=2.61 | |||

| |Mar precipitation inch=4.00 | |||

| |Apr precipitation inch=3.18 | |||

| |May precipitation inch=4.00 | |||

| |Jun precipitation inch=4.64 | |||

| |Jul precipitation inch=4.37 | |||

| |Aug precipitation inch=4.90 | |||

| |Sep precipitation inch=4.61 | |||

| |Oct precipitation inch=3.39 | |||

| |Nov precipitation inch=3.06 | |||

| |Dec precipitation inch=3.51 | |||

| |year precipitation inch=45.50 | |||

| |Jan snow inch=3.7 | |||

| |Feb snow inch=2.2 | |||

| |Mar snow inch=1.1 | |||

| |Apr snow inch=0.0 | |||

| |May snow inch=0.0 | |||

| |Jun snow inch=0.0 | |||

| |Jul snow inch=0.0 | |||

| |Aug snow inch=0.0 | |||

| |Sep snow inch=0.0 | |||

| |Oct snow inch=0.0 | |||

| |Nov snow inch=0.0 | |||

| |Dec snow inch=1.8 | |||

| |year snow inch=8.8 | |||

| |unit precipitation days=0.01 in | |||

| |Jan precipitation days=10.0 | |||

| |Feb precipitation days=9.0 | |||

| |Mar precipitation days=10.8 | |||

| |Apr precipitation days=10.5 | |||

| |May precipitation days=11.1 | |||

| |Jun precipitation days=10.6 | |||

| |Jul precipitation days=11.4 | |||

| |Aug precipitation days=9.4 | |||

| |Sep precipitation days=9.3 | |||

| |Oct precipitation days=8.1 | |||

| |Nov precipitation days=8.4 | |||

| |Dec precipitation days=10.0 | |||

| |year precipitation days=118.6 | |||

| |unit snow days=0.1 in | |||

| |Jan snow days=1.9 | |||

| |Feb snow days=1.7 | |||

| |Mar snow days=1.0 | |||

| |Apr snow days=0.6 | |||

| |May snow days=0.0 | |||

| |Jun snow days=0.0 | |||

| |Jul snow days=0.0 | |||

| |Aug snow days=0.0 | |||

| |Sep snow days=0.0 | |||

| |Oct snow days=0.0 | |||

| |Nov snow days=0.1 | |||

| |Dec snow days=0.9 | |||

| |year snow days=5.6 | |||

| |Jan humidity=67.9 | |||

| |Feb humidity=65.6 | |||

| |Mar humidity=63.0 | |||

| |Apr humidity=60.8 | |||

| |May humidity=69.5 | |||

| |Jun humidity=72.2 | |||

| |Jul humidity=74.8 | |||

| |Aug humidity=77.2 | |||

| |Sep humidity=77.0 | |||

| |Oct humidity=73.8 | |||

| |Nov humidity=69.1 | |||

| |Dec humidity=68.9 | |||

| |year humidity=70.0 | |||

| |Jan sun=172.5 | |||

| |Feb sun=179.7 | |||

| |Mar sun=233.3 | |||

| |Apr sun=261.6 | |||

| |May sun=288.0 | |||

| |Jun sun=306.4 | |||

| |Jul sun=301.4 | |||

| |Aug sun=278.9 | |||

| |Sep sun=237.9 | |||

| |Oct sun=222.8 | |||

| |Nov sun=183.5 | |||

| |Dec sun=163.0 | |||

| |Jan percentsun=56 | |||

| |Feb percentsun=59 | |||

| |Mar percentsun=63 | |||

| |Apr percentsun=66 | |||

| |May percentsun=65 | |||

| |Jun percentsun=69 | |||

| |Jul percentsun=67 | |||

| |Aug percentsun=66 | |||

| |Sep percentsun=64 | |||

| |Oct percentsun=64 | |||

| |Nov percentsun=60 | |||

| |Dec percentsun=55 | |||

| |year percentsun=64 | |||

| | Jan dew point C=-4.0 | |||

| | Feb dew point C=−3.1 | |||

| | Mar dew point C=0.9 | |||

| | Apr dew point C=5.3 | |||

| | May dew point C=12.3 | |||

| | Jun dew point C=17.2 | |||

| | Jul dew point C=19.8 | |||

| | Aug dew point C=19.6 | |||

| | Sep dew point C=15.9 | |||

| | Oct dew point C=9.1 | |||

| | Nov dew point C=3.4 | |||

| | Dec dew point C=−1.4 | |||

| | Jan uv=2 | |||

| | Feb uv=3 | |||

| | Mar uv=5 | |||

| | Apr uv=7 | |||

| | May uv=8 | |||

| | Jun uv=9 | |||

| | Jul uv=9 | |||

| | Aug uv=9 | |||

| | Sep uv=7 | |||

| | Oct uv=5 | |||

| | Nov uv=3 | |||

| | Dec uv=2 | |||

| |source 1=] (relative humidity and sunshine hours 1961–1990)<ref name="NWS Wakefield, VA (AKQ)1">{{cite web | |||

| |url = https://w2.weather.gov/climate/xmacis.php?wfo=akq | |||

| |title = NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data | |||

| |publisher = ] | |||

| |access-date = May 4, 2021 | |||

| |df = mdy-all | |||

| |archive-date = September 5, 2015 | |||

| |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20150905143500/http://w2.weather.gov/climate/xmacis.php?wfo=akq | |||

| |url-status = live }}</ref><ref name="NCDC TXT KRIC">{{cite web | |||

| |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20210505002327/https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/services/data/v1?dataset=normals-monthly-1991-2020&startDate=0001-01-01&endDate=9996-12-31&stations=USW00013740&format=pdf | |||

| |archive-date = May 5, 2021 | |||

| |url = https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/services/data/v1?dataset=normals-monthly-1991-2020&startDate=0001-01-01&endDate=9996-12-31&stations=USW00013740&format=pdf | |||

| |publisher = National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration | |||

| |title = Summary of Monthly Normals 1991–2020 | |||

| |access-date = May 4, 2021 | |||

| |url-status = live}}</ref><ref name="WMO 1961–90 KRIC">{{cite web | |||

| |url = ftp://ftp.atdd.noaa.gov/pub/GCOS/WMO-Normals/TABLES/REG_IV/US/GROUP3/72401.TXT | |||

| |title = WMO Climate Normals for Richmond/Byrd, VA 1961–1990 | |||

| |access-date = 2020-07-29 | |||

| |publisher = ] | |||

| |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20240216015028/ftp://ftp.atdd.noaa.gov/pub/GCOS/WMO-Normals/TABLES/REG_IV/US/GROUP3/72401.TXT | |||

| |archive-date = 2024-02-16}}</ref> | |||

| |source 2 = Weather Atlas<ref>{{cite web | |||

| |url = https://www.weather-us.com/en/virginia-usa/richmond-climate | |||

| |title = Richmond, VA - Detailed climate information and monthly weather forecast | |||

| |publisher = Yu Media Group | |||

| |website = Weather Atlas | |||

| |language = en | |||

| |access-date = June 29, 2019 | |||

| |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20190629162344/https://www.weather-us.com/en/virginia-usa/richmond-climate | |||

| |archive-date = June 29, 2019 | |||

| |url-status = dead}}</ref> | |||

| }}<section end="weather box" /> | |||

| {{Graph:Weather monthly history | |||

| | table=Ncei.noaa.gov/weather/Richmond, Virginia.tab | |||

| | title=Richmond monthly weather statistics | |||

| }} | |||

| ==Demographics== | |||

| {{US Census population | |||

| |1790=3761 | |||

| |1800=5737 | |||

| |1810=9735 | |||

| |1820=12067 | |||

| |1830=16060 | |||

| |1840=20153 | |||

| |1850=27570 | |||

| |1860=37910 | |||

| |1870=51038 | |||

| |1880=63600 | |||

| |1890=81388 | |||

| |1900=85050 | |||

| |1910=127628 | |||

| |1920=171667 | |||

| |1930=182929 | |||

| |1940=193042 | |||

| |1950=230310 | |||

| |1960=219958 | |||

| |1970=249621 | |||

| |1980=219214 | |||

| |1990=203056 | |||

| |2000=197790 | |||

| |2010=204214 | |||

| |2020=226610 | |||

| |estyear= 2022 | |||

| |estimate= 229395 | |||

| |estref= | |||

| |align-fn=center | |||

| |footnote=U.S. Decennial Census<ref name="DecennialCensus">{{cite web |url=https://www.census.gov/prod/www/decennial.html |title=Census of Population and Housing from 1790 |publisher=] |access-date=January 24, 2022 |archive-date=May 7, 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150507121432/http://www.census.gov/prod/www/decennial.html |url-status=live }}</ref><br />1790–1960<ref>{{cite web |url=http://mapserver.lib.virginia.edu |title=Historical Census Browser |publisher=University of Virginia Library |access-date=January 2, 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131226073904/http://mapserver.lib.virginia.edu/ |archive-date=December 26, 2013 |url-status=live}}</ref> 1900–1990<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.census.gov/population/cencounts/va190090.txt |title=Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990 |publisher=United States Census Bureau |access-date=January 2, 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131215150359/http://www.census.gov/population/cencounts/va190090.txt |archive-date=December 15, 2013 |url-status=live}}</ref><br />1990–2000<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.census.gov/population/www/cen2000/briefs/phc-t4/tables/tab02.pdf |title=Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000 |publisher=United States Census Bureau |access-date=January 2, 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141218203824/http://www.census.gov/population/www/cen2000/briefs/phc-t4/tables/tab02.pdf |archive-date=December 18, 2014 |url-status=live}}</ref><br />2010–2020<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/interactive/2020-population-and-housing-state-data.html |title=2020 Population and Housing State Data |newspaper=Census.gov |publisher=United States Census Bureau |access-date=August 14, 2021 |archive-date=August 24, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210824081449/https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/interactive/2020-population-and-housing-state-data.html |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| }} | |||

| Richmond's population is approximately 226,000. As an independent city, Richmond is surrounded by ], which has a population of about 334,000. The ] has an estimated population of about 1.3 million. | |||

| {| class="wikitable" style="text-align:center;" | |||

| |+'''Richmond, Virginia – Racial and ethnic composition'''<br><small>{{nobold|''Note: the US Census treats Hispanic/Latino as an ethnic category. This table excludes Latinos from the racial categories and assigns them to a separate category. Hispanics/Latinos may be of any race.''}}</small> | |||

| !Race / Ethnicity <small>(''NH = Non-Hispanic'')</small> | |||

| !Pop 2000<ref name=2000CensusP004>{{Cite web|title=P004 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2000: DEC Summary File 1 – Richmond city, Virginia|url=https://data.census.gov/table?q=p004&g=160XX00US5167000&tid=DECENNIALSF12000.P004|website=]}}</ref> | |||

| !Pop 2010<ref>{{cite web |title=P2 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race - 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) - Richmond city, Virginia |url=https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?g=160XX00US5167000&tid=DECENNIALPL2010.P2 |website=] |access-date=January 23, 2022 |archive-date=January 23, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220123223000/https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?g=160XX00US5167000&tid=DECENNIALPL2010.P2 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| !{{partial|Pop 2020}}<ref>{{cite web |title=P2 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race - 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) - Richmond, Virginia |url=https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?g=1600000US5167000&tid=DECENNIALPL2020.P2 |website=] |access-date=January 23, 2022 |archive-date=January 23, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220123223002/https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?g=1600000US5167000&tid=DECENNIALPL2020.P2 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| !% 2000 | |||

| !% 2010 | |||

| !{{partial|% 2020}} | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |] (NH) | |||

| | align="center" colspan=2 | <font size="-1">City ]: "River City"</font> | |||

| |74,506 | |||

| |79,813 | |||

| |style='background: #ffffe6; |95,220 | |||

| |37.67% | |||

| |39.08% | |||

| |style='background: #ffffe6; |42.02% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |] (NH) | |||

| | align="center" colspan=2 | ]<br>Location in the Commonwealth of ] | |||

| |112,455 | |||

| |102,264 | |||

| |style='background: #ffffe6; |90,490 | |||

| |56.86% | |||

| |50.08% | |||

| |style='background: #ffffe6; |39.93% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | |

|] or ] (NH) | ||

| |460 | |||

| | ] | |||

| |514 | |||

| |style='background: #ffffe6; |440 | |||

| |0.23% | |||

| |0.25% | |||

| |style='background: #ffffe6; |0.19% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |] (NH) | |||

| | ]<br> - Total<br> - Water | |||

| |2,437 | |||

| | <br> 162.0 km² (62.5 mi²)<br>6.4 km² (2.5 mi²) 3.96% | |||

| |4,679 | |||

| |style='background: #ffffe6; |6,199 | |||

| |1.23% | |||

| |2.29% | |||

| |style='background: #ffffe6; |2.74% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |] (NH) | |||

| | ]<br> - Total (])<br> - ]<br> - ] | |||

| |66 | |||

| | <br> 197,790 <br>1,271.3/km² <br> 1,126,262 (] est.) | |||

| |93 | |||

| |style='background: #ffffe6; |69 | |||

| |0.03% | |||

| |0.05% | |||

| |style='background: #ffffe6; |0.03% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |Some Other Race (NH) | |||

| | ] | |||

| |319 | |||

| | ]: ]–-5 | |||

| |367 | |||

| |style='background: #ffffe6; |1,378 | |||

| |0.16% | |||

| |0.18% | |||

| |style='background: #ffffe6; |0.61% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |] (NH) | |||

| | ] || {{coor dms|37|31|58.8|N|77|28|1.2|W|region:US}} | |||

| |2,473 | |||

| |3,681 | |||

| |style='background: #ffffe6; |9,067 | |||

| |1.25% | |||

| |1.80% | |||

| |style='background: #ffffe6; |4.00% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |] (any race) | |||

| | ] | |||

| |5,074 | |||

| | ] | |||

| |12,803 | |||

| |style='background: #ffffe6; |23,747 | |||

| |2.57% | |||

| |6.27% | |||

| |style='background: #ffffe6; |10.48% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| |'''Total''' | |||

| | align="center" colspan=2 | | |||

| |'''197,790''' | |||

| |'''204,214''' | |||

| |style='background: #ffffe6; |'''226,610''' | |||

| |'''100.00%''' | |||

| |'''100.00%''' | |||

| |style='background: #ffffe6; |'''100.00%''' | |||

| |} | |} | ||

| '''Richmond''' is the ] of the ] of ], in the ]. Like all Virginia municipalities incorporated as ''cities'', it is an ], not part of any ] (] is unrelated, and located in a different region of the ]). Richmond is located on the ] of the ] in the ] region of ] and is at the center of the Richmond ] (MSA). | |||

| {{bar box | |||

| Common colloquialisms for the city are: '''RIC''' (its ]), or '''The ]''' (its ]), or even '''RVA'''. | |||

| |title=Ancestry in Richmond, VA (2014-2018)<ref>U.S. Census Bureau (2014-2018). People Reporting Ancestry American Community Survey 5-year estimates. Retrieved from https://censusreporter.org {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220401060242/https://censusreporter.org/ |date=April 1, 2022 }}></ref><ref>U.S. Census Bureau (2014-2018). Hispanic or Latino Origin by Specific Origin American Community Survey 5-year estimates. Retrieved from https://censusreporter.org {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220401060242/https://censusreporter.org/ |date=April 1, 2022 }}></ref> | |||

| |titlebar=#ddd |left1=Origin |right1=percent |float=right | |||

| |bars= | |||

| {{bar percent|] (Does not include West Indian or African)|dodgerblue|45.2}} | |||

| {{bar percent|] (Includes "American" ancestry)|lightblue|12.1}} | |||

| {{bar percent|Scottish or Irish American (Includes Scots-Irish)|black|9.9}} | |||

| {{bar percent|]|purple|7.4}} | |||

| {{bar percent|] (Includes Honduran, Salvadoran, Costa Rican, etc.)|darkred|3.2}} | |||

| {{bar percent|]|lightgreen|1.8}} | |||

| {{bar percent|Other|orange|20.4}}}} | |||

| As of the ], there were 204,214 people living in the city. 50.6% were ], 40.8% ], 2.3% ], 0.3% ], 0.1% ], 3.6% of some other race and 2.3% ]. 6.3% were ] (of any race).<ref>{{cite web |url=http://censusviewer.com/city/VA/Richmond |title=Richmond, VA Population - Census 2010 and 2000 Interactive Map, Demographics, Statistics, Quick Facts - CensusViewer |website=Census Viewer |via=censusviewer.com | access-date=August 8, 2019 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190808170638/http://censusviewer.com/city/VA/Richmond | archive-date=August 8, 2019 | url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| ==History== | |||

| ] | |||

| {{main|History of Richmond, Virginia}} | |||

| In ], ] granted a ] to the ] to settle colonists in ]. After the first permanent ] settlement was established later that year at ], ] and ] set sail ten days after landing at Jamestown, traveling northwest up Powhatan's River (now known as the ]) to Powhatan Hill. The first expedition consisted of 120 men from Jamestown, and made the first attempt to settle at the Falls of the James, located between the 14th Street Bridge in modern downtown Richmond and the Pony Pasture (a recreational area along the banks of the river south of the City of Richmond). The settlement was made at this location as it is the highest navigable site along the James River. | |||

| As of the census<ref name="GR8">{{cite web |url=https://www.census.gov |publisher=] |access-date=May 14, 2011 |title=U.S. Census website |archive-date=July 1, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210701194655/https://www.census.gov/ |url-status=live }}</ref> of 2000, there were 197,790 people, 84,549 households, and 43,627 families living in the city. The population density was {{cvt|3,292.6|PD/sqmi}}. There were 92,282 housing units at an average density of {{cvt|1,536.2|/sqmi}}. The racial makeup of the city was 57.2% ], 38.3% ], 0.2% ], 1.3% ], 0.1% ], 1.5% from ], and 1.5% from two or more races. ] or ] of any race were 2.6% of the population. | |||

| ===Revolutionary War=== | |||

| In ], ] delivered his famous “]” speech in ], during the Second Virginia Convention. This speech is credited with convincing members of the House of Burgesses to pass a resolution delivering Virginia troops to the ]. One year later, in the throes of the Revolutionary War, the ] adopted the ]. | |||

| There were 84,549 households, out of which 23.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 27.1% were married couples living together, 20.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 48.4% were non-families. 37.6% of all households were made up of individuals, and 10.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.21 and the average family size was 2.95. | |||

| In ], Virginia’s state capital was moved from ] to Richmond. In ], under the command of ], Richmond was burned by British troops. Yet Richmond shortly recovered, and, in ] ], was incorporated as a city. | |||

| In the city, the age distribution of the population shows 21.8% under the age of 18, 13.1% from 18 to 24, 31.7% from 25 to 44, 20.1% from 45 to 64, and 13.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 34 years. For every 100 females, there were 87.1 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 83.5 males. | |||

| ===Civil War=== | |||

| ] | |||

| The aversion to the slave trade was growing by the mid-nineteenth century, and in ], Henry “Box” Brown made history by having himself nailed into a small box and shipped from Richmond to ], escaping slavery to the land of freedom. | |||

| The median income for a household in the city was $31,121, and the median income for a family was $38,348. Males had a median income of $30,874 versus $25,880 for females. The per capita income for the city was $20,337. About 17.1% of families and 21.4% of the population were below the poverty line, including 32.9% of those under age 18 and 15.8% of those age 65 or over. | |||

| At the outbreak of the ] in ], the strategic location of the Tredegar Iron Works was one of the primary factors in the decision to make Richmond the '''Capital of the Confederacy'''. From this arsenal came the 723 tons of armor plating that covered the ], the world’s first ] used in war, as well as much of the Confederates' heavy ordnance machinery. In ], ] was inaugurated as ] of the ]. One month later Davis placed Richmond under martial law. Two months after Davis’ inauguration, the Confederate army fired on ] in ], and the Civil War had begun. The Seven Days Battle followed in June of 1862. Four years later the house was seized by the Union Army when ] captured Richmond in ] ]. One week later, ] surrendered to Grant ending the ]. In ], on ''Evacuation Sunday'', large parts of the city were destroyed in a fire set by retreating Confederate soldiers. | |||

| ===Crime=== | |||

| ] was laid out it ], with a series of monuments at various intersections honoring the city's Confederate heroes. Included (east to west) were ], ], ], ], and ]. Richmond is the final resting place of both Stuart and Davis (see ]). | |||

| Richmond experienced a spike in overall crime, particularly in the ], during the 1980s, 1990s, and the early 2000s, when it was consistently ranked as one of the most dangerous cities in the United States.<ref name="Morgan_Quitno">{{cite web |title=Top and Bottom 25 Cities Overall |url=http://www.statestats.com/cit05pop.htm |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120218212520/http://www.statestats.com/cit05pop.htm |archive-date=February 18, 2012 |access-date=July 14, 2012 |publisher=]}}</ref><ref name="cqpress">{{cite web |title=CQpress.com |url=http://cqpress.com/docs/met05r.pdf |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120813051847/http://cqpress.com/docs/met05r.pdf |archive-date=August 13, 2012 |access-date=July 14, 2012}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Infoplease.com |url=http://www.infoplease.com/ipa/A0934323.html |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110227223443/http://www.infoplease.com/ipa/A0934323.html |archive-date=February 27, 2011 |access-date=November 1, 2011 |publisher=Infoplease.com}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Statestats.com |url=http://www.statestats.com/cit06pop.htm |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111005173024/http://www.statestats.com/cit06pop.htm |archive-date=October 5, 2011 |access-date=November 1, 2011 |publisher=Statestats.com}}</ref> | |||

| Since the late 2000s, various forms of crime have significantly decreased in the city.<ref name="CLR">{{cite web |title=2010 Crime Rate Indexes for Richmond, Virginia. |url=http://www.clrsearch.com/Richmond_Demographics/VA/Crime-Rate |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120723095903/http://www.clrsearch.com/Richmond_Demographics/VA/Crime-Rate |archive-date=July 23, 2012 |access-date=July 14, 2012 |publisher=CLR Search.}}</ref> Its major crime rate, including violent and property crimes, decreased 47 percent between 2004 and 2009 to its lowest level in more than a quarter of a century.<ref name="Williams_Bowes">{{cite news |author1=Williams, Reed |author2=Bowes, Mark |date=January 10, 2010 |title=Central Va. had 4 fewer homicides last year than in 2008. |newspaper=] |url=http://www2.timesdispatch.com/news/2010/jan/10/homi10_20100109-221204-ar-20533/ |url-status=dead |access-date=July 14, 2012 |archive-url=https://archive.today/20130204183204/http://www2.timesdispatch.com/news/2010/jan/10/homi10_20100109-221204-ar-20533/ |archive-date=February 4, 2013 }}</ref> In 2008, Richmond had fallen to 49th on a ] ranking of the most dangerous cities in the United States, and the city recorded its lowest homicide rate since 1971.<ref name="Williams_Reed">{{cite news |last=Williams |first=Reed |date=December 7, 2008 |title=Richmond's homicide rate on pace to reach 37-year low. |newspaper=] |url=http://www2.timesdispatch.com/news/2008/dec/07/rhom07_20081206-211651-ar-102109/ |url-status=dead |access-date=July 14, 2012 |archive-url=https://archive.today/20130204132209/http://www2.timesdispatch.com/news/2008/dec/07/rhom07_20081206-211651-ar-102109/ |archive-date=February 4, 2013 }}</ref><ref name="2008_rankings">{{cite web |title=2008 City Crime Rankings. |url=http://os.cqpress.com/citycrime/CityCrime2008_Rank_Rev.pdf |publisher=CQ Press |access-date=July 14, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120904020922/http://os.cqpress.com/citycrime/CityCrime2008_Rank_Rev.pdf |archive-date=September 4, 2012 |url-status=dead}}</ref> By 2012, Richmond was no longer in the top 200.<ref name="2012_rankings">{{cite web |title=2012 City Crime Rankings. |url=http://os.cqpress.com/citycrime/2012/CityCrime2013_CityCrimeRateRankings.pdf |publisher=CQ Press |access-date=August 29, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130228004156/http://os.cqpress.com/citycrime/2012/CityCrime2013_CityCrimeRateRankings.pdf |archive-date=February 28, 2013 |url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| ], where ] | |||

| successfully demonstrated his new system on the hills in ]. The intersection | |||

| shown is at 8th & Broad Streets.]] | |||