| Revision as of 07:42, 3 December 2008 view sourceBackslash Forwardslash (talk | contribs)20,602 editsm Reverted edits by 59.37.60.113 to last version by Backslash Forwardslash (HG)← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 21:31, 9 January 2025 view source Platosghostlybeard (talk | contribs)392 editsm →Religious and other cultural contexts: I added a brief point with appropriate reference to the scholarly literature and a link to another Misplaced Pages article.Tag: Visual edit | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Event occurring in the mind while sleeping}} | |||

| {{otheruses}} | |||

| {{Other uses|Dream (disambiguation)|Dreams (disambiguation)}} | |||

| ].]] | |||

| {{pp-vandalism|small=yes}} | |||

| '''Dreams''' are ] images, sounds and feelings experienced while ], particularly strongly associated with ]. The contents and ] purposes of dreams are not fully understood, though they have been a topic of ] and interest throughout recorded history. The scientific study of dreams is known as ]. | |||

| ] dreaming of a confrontation with ], shown inside a ]]] | |||

| A '''dream''' is a succession of ]s, ]s, ], and ] that usually occur involuntarily in the ] during certain stages of ].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.thefreedictionary.com/dream |title=Dream |publisher=The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. 2000 |access-date=7 May 2009}}</ref> Humans spend about two hours dreaming per night,<ref>{{cite web |year=2006 |title=Brain Basics: Understanding Sleep |url=http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/brain_basics/understanding_sleep.htm |access-date=16 December 2007 |publisher=] |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071011011207/http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/brain_basics/understanding_sleep.htm |archive-date=11 October 2007}}</ref> and each dream lasts around 5–20 minutes, although the dreamer may perceive the dream as being much longer than this.<ref name="HSWDream">{{cite book |year=2006 |title=How Dream Works |author=Lee Ann Obringer |url=http://science.howstuffworks.com/dream3.htm |access-date=4 May 2006 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060418032147/http://science.howstuffworks.com/dream3.htm |archive-date=18 April 2006}}</ref> | |||

| ==Neurology of sleep and dreams== | |||

| {{main|REM sleep}} | |||

| ] showing brainwaves during REM sleep|thumb|200px]] | |||

| There is no universally agreed biological definition of dreaming. General observation shows that dreams are strongly associated with ], during which an ] shows brain activity to be most like wakefulness. Participant-nonremembered dreams during ] are normally more mundane in comparison.<ref name=Dement1957>{{cite journal | author = Dement, W. | coauthors = Kleitman, N. | year = 1957 | title = The Relation of Eye Movements during Sleep to Dream Activity.' | journal = Journal of Experimental Psychology | volume = 53 | pages = 89–97 | doi = 10.1037/h0048189 <!--Retrieved from CrossRef by DOI bot-->}}</ref> During a typical lifespan, a human spends a total of about six years dreaming<ref>{{cite book| year = 2006| title = How Dream Works| url = http://science.howstuffworks.com/dream3.htm| accessdate = 2006-05-04}}</ref> (which is about two hours each night<ref>{{cite web | year = 2006| title = Brain Basics: Understanding Sleep| url = http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/brain_basics/understanding_sleep.htm | accessdate = 2007-12-16 | publisher = ] }}</ref>). It is unknown where in the brain dreams originate, if there is a single origin for dreams or if multiple portions of the brain are involved, or what the purpose of dreaming is for the body or mind. It has been hypothesized that dreams are the result of ] in the brain. A biochemical mechanism for this was proposed by the medical researcher ], who suggested in 1988 that DMT might be connected with visual dream phenomena, where brain DMT levels are periodically elevated to induce visual dreaming and possibly other natural states of mind.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Wallach J |title=Endogenous hallucinogens as ligands of the trace amine receptors: A possible role in sensory perception |journal=Med Hypotheses |volume=in print |issue=in print |pages=in print |year=2008 |pmid=18805646 |doi=10.1016/j.mehy.2008.07.052}}</ref> | |||

| The content and function of dreams have been topics of scientific, philosophical and religious interest throughout ]. ], practiced by the ]ns in the third millennium BCE<ref>{{cite book |last1=Krippner |first1=Stanley |last2=Bogzaran |first2=Fariba |last3=Carvalho |first3=Andre Percia de |date=2002 |title=Extraordinary Dreams and How To Work with Them |location=Albany, NY |publisher=State University of New York Press |quote=Clay tablets have been found, dating to about 2500 B.C.E., that contain interpretive material for Babylonian and ]n dreamers. |page=9 |isbn=0-7914-5257-3}}</ref> and even earlier by the ancient ]ians,<ref>{{cite book |last=Seligman |first=K |date=1948 |title=Magic, Supernaturalism and Religion |location=New York |publisher=Random House}}</ref><ref name="BlackGreen1992">{{cite book |last1=Black |first1=Jeremy |first2=Anthony |last2=Green |title=Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Illustrated Dictionary |location=Austin |publisher=University of Texas Press |year=1992 |isbn=0714117056 |pages=71–72, 89–90}}</ref> figures prominently in religious texts in several traditions, and has played a lead role in psychotherapy.<ref name="Freud1">{{cite book |last=Freud |first=Sigmund |translator=James Strachey |editor=James Strachey |author-link=Sigmund Freud |date=1965 |title=The Interpretation of Dreams |location=New York |publisher=Avon}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Schredl |first1=Michael |last2=Bohusch |first2=Claudia |last3=Kahl |first3=Johanna |last4=Mader |first4=Andrea |last5=Somesan |first5=Alexandra |title=The Use of Dreams in Psychotherapy |journal=The Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research |year=2000 |volume=9 |issue=2 |pages=81–87}}</ref> The scientific study of dreams is called ].<ref>{{cite journal |last=Kavanau |first=J.L. |title=Sleep, memory maintenance, and mental disorders |journal=Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences |year=2000 |volume=12 |issue=2 |pages=199–208 |doi=10.1176/jnp.12.2.199 |pmid=11001598 |issn = 0895-0172 }}</ref> Most modern dream study focuses on the neurophysiology of dreams and on proposing and testing hypotheses regarding dream function. It is not known where in the brain dreams originate, if there is a single origin for dreams or if multiple regions of the brain are involved, or what the purpose of dreaming is for the body or mind. | |||

| During REM sleep, the release of certain neurotransmitters is completely suppressed. As a result, ]s are not stimulated, a condition known as ]. This prevents dreams from resulting in dangerous movements of the body. | |||

| The human dream experience and what to make of it has undergone sizable shifts over the course of history.<ref name="Dodds1">{{cite book |last= Dodds |first=E. R. |author-link=E. R. Dodds |date=1951 |title=The Greeks and the Irrational |location=Berkeley |publisher=University of California Press |quote=The Greeks never spoke as we do of ''having'' a dream, but always of ''seeing'' a dream.... |page= 105}}</ref><ref name="Packer1">{{cite book |last=Packer |first=Sharon |date=2002 |title=Dreams in Myth, Medicine, and Movies |location=Westport, CT |publisher=Praeger Publishers |quote=…any more ancient cultures think that dreams are imposed by a force that resides outside the individual. |page=85 |isbn=0-275-97243-7}}</ref> Long ago, according to writings from ] and ], dreams dictated post-dream behaviors to an extent that was sharply reduced in later millennia.{{clarify|date=August 2023}} These ancient writings about dreams highlight visitation dreams, where a dream figure, usually a deity or a prominent forebear, commands the dreamer to take specific actions, and which may predict future events.<ref>{{cite book |last=Macrobius |author-link=Macrobius |translator=] |date=1952 |orig-date=430 |title=Commentary on the Dream of Scipio |location=New York |publisher=Columbia University Press |quote=We call a dream oracular in which a parent, or a pious or revered man, or a priest, or even a god clearly reveals what will or will not transpire, and what action to take or to avoid. |page=90}}</ref><ref>Dodds (1951), referring to the type of dream described by Macrobius: "This last type is not, I think, at all common in our own dream-experience. But there is considerable evidence that dreams of this sort were familiar in antiquity." (p. 107).</ref><ref name=Krippner1>{{cite book |last1=Krippner |first1=Stanley |last2=Bogzaran |first2=Fariba |last3=Carvalho |first3=André Percia de |date=2002 |title=Extraordinary Dreams and How To Work with Them |location=Albany |publisher=State University of New York Press |quote=The Egyptian papyrus of Deral-Madineh was written about 1300 B.C.E. and gives instructions on how to obtain a dream message from a god. |page=10 |isbn=0-7914-5257-3}}</ref> Framing the dream experience varies across cultures as well as through time. | |||

| Studies show that various species of mammals and birds experience REM during sleep.<ref>{{cite web| year = 2003| title = The Evolution of REM Dreaming| url = http://www.improverse.com/ed-articles/richard_wilkerson_2003_jan_evolution.htm| accessdate = 2008-08-27}}</ref> | |||

| Dreaming and sleep are intertwined. Dreams occur mainly in the ]—when ] is high and resembles that of being awake. Because REM sleep is detectable in many species, and because research suggests that all mammals experience REM,<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Lesku |first1=J. A. |last2=Meyer |first2=L. C. R. |last3=Fuller |first3=A. |last4=Maloney |first4=S. K. |last5=Dell'Omo |first5=G. |last6=Vyssotski |first6=A. L. |last7=Rattenborg |first7=N. C. |year=2011 |title=Ostriches sleep like platypuses |journal=PLOS ONE |volume=6 |issue=8 |pages=1–7 |doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0023203 |pmid=21887239 |pmc=3160860 |bibcode= 2011PLoSO...623203L |doi-access=free}}</ref> linking dreams to REM sleep has led to conjectures that animals dream. However, humans dream during non-REM sleep, also, and not all REM awakenings elicit dream reports.<ref name=Solms1>{{cite journal |last=Solms |first=Mark |author-link=Mark Solms |title=Dreaming and REM sleep are controlled by different brain mechanisms |journal=Behavioral and Brain Sciences |year=2000 |volume=23 |issue=6 |pages=843–850 |doi=10.1017/S0140525X00003988 |pmid=11515144 |s2cid=7264870 |quote=Dreaming and REM sleep are incompletely correlated. Between 5 and 30% of REM awakenings do not elicit dream reports; and at least 5–10% of NREM awakenings do elicit dream reports that are indistinguishable from REM....}}</ref> To be studied, a dream must first be reduced to a verbal report, which is an account of the subject's memory of the dream, not the subject's dream experience itself. So, dreaming by non-humans is currently unprovable, as is dreaming by human fetuses and pre-verbal infants.<ref>{{cite book |last=Bulkeley |first=Kelly |title=Dreaming in the world's religions: A comparative history |year=2008 |isbn=978-0-8147-9956-7 |page=14 |publisher=NYU Press |quote=Do animals dream? We currently have no means of proving it one way or the other, just as we have no way to determine whether human fetuses and newborns are genuinely dreaming before they develop the ability to speak and relate their experiences.}}</ref> | |||

| ===Discovery of REM=== | |||

| == Subjective experience and content == | |||

| In 1953 ] discovered ] while working in the surgery of his ] advisor. Aserinsky noticed that the sleepers' eyes fluttered beneath their closed eyelids, later using a ] machine to record their ] during these periods. In one session he awakened a subject who was wailing and crying out during REM and confirmed his suspicion that dreaming was occurring.<ref>{{cite book | |||

| {{Further|Oneiromancy}} | |||

| | last = Dement | |||

| ] (1848–1906)]] | |||

| | first = William | |||

| | title = The Sleepwatchers | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | year = 1996 | |||

| | isbn = 0964933802 }}</ref> In 1953 Aserinsky and his advisor published the ground-breaking study in ].<ref name="as-science">{{cite journal | last = Aserinsky | first = E | coauthors = Kleitman, N. | year = 1953 | month = September | title = Regularly occurring periods of eye motility, and concomitant phenomena, during sleep | journal = Science | volume = 118 | issue = 3062 | pages = 273–274 | doi = 10.1126/science.118.3062.273 | pmid = 13089671 }}</ref> | |||

| Preserved writings from early Mediterranean civilizations indicate a relatively abrupt change in subjective dream experience between ] antiquity and the beginnings of the ].<ref>{{cite book |last=Damasio |first=Antonio |author-link= Antonio Damasio |date=2010 |title=Self Comes to Mind |location=New York |publisher=Pantheon Books |quote=…I sympathize with Julian Jaynes's claim that something of great import may have happened to the human mind during the relatively brief interval of time between the events narrated in the ''Iliad'' and those that make up the ''Odyssey''. |page=289 |isbn=978-0-307-37875-0}}</ref> | |||

| ==Dream theories== | |||

| ===Activation-synthesis=== | |||

| In 1976, J. Allan Hobson and ] proposed a new theory that changed dream research, challenging the previously held ] view of dreams as unconscious wishes to be interpreted. The ] asserts that the sensory experiences are fabricated by the cortex as a means of interpreting ] signals from the ]. They propose that in REM sleep, the ascending ] PGO (ponto-geniculo-occipital) waves stimulate higher ] and ] cortical structures, producing rapid eye movements. The activated forebrain then synthesizes the dream out of this internally generated information. They assume that the same structures that induce REM sleep also generate sensory information. | |||

| In visitation dreams reported in ancient writings, dreamers were largely passive in their dreams, and visual content served primarily to frame authoritative auditory messaging.<ref>{{Citation |last=Nielsen |first=Tore A. |contribution=Reality Dreams and Their Effects on Spiritual Belief: A Revision of Animism Theory |editor-last1=Gackenbach |editor-first1=Jayne |editor-last2=Sheikh |editor-first2=Anees A. |title=Dream Images: A Call to Mental Arms |year=1991 |pages=233–264 |place=Amityville, NY |publisher=Baywood |isbn=0-89503-056-X}}</ref><ref name="Dodds1"/><ref>{{cite journal|last=Atwan |first=Robert |title=The Interpretation of Dreams, The Origin of Consciousness, and the Birth of Tragedy |journal=Research Communication in Psychology, Psychiatry and Behavior |year=1981 |volume=6 |issue=2 |pages=163–182}}</ref> ], the king of the Sumerian city-state of ] (reigned {{circa}} 2144–2124 BCE), rebuilt the temple of ] as the result of a dream in which he was told to do so.<ref name="BlackGreen1992"/> After antiquity, the passive hearing of visitation dreams largely gave way to visualized narratives in which the dreamer becomes a character who actively participates. | |||

| Hobson and McCarley's 1976 research suggested that the signals interpreted as dreams originated in the brain stem during REM sleep. However, research by Mark Solms suggests that dreams are generated in the ], and that REM sleep and dreaming are not directly related.<ref>{{cite book | |||

| | last = Solms | |||

| | first = M. | |||

| | year = 2000 | |||

| | title = Dreaming and REM sleep are controlled by different brain mechanisms | |||

| | publisher = Behavioral and Brain Sciences | |||

| | edition = 23(6) | |||

| | pages = 793-1121 | |||

| }}</ref> While working in the neurosurgery department at hospitals in ] and ], Solms had access to patients with various brain injuries. He began to question patients about their dreams and confirmed that patients with damage to the ] stopped dreaming; this finding was in line with Hobson's 1977 theory. However, Solms did not encounter cases of loss of dreaming with patients having brain stem damage. This observation forced him to question Hobson's prevailing theory which marked the brain stem as the source of the signals interpreted as dreams. Solms viewed the idea of dreaming as a function of many complex brain structures as validating Freudian dream theory, an idea that drew criticism from Hobson.<ref>{{cite book | |||

| | last = Rock dreams are not always true. | |||

| | first = Andrea | |||

| | title = The Mind at Night: The New Science of How and Why we Dream | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | year = 2004 | |||

| | chapter = 3 | |||

| | isbn = 0465070698 }}</rEF> Unhappy about Hobson's attempts at discrediting him, Solms, along with partner Edward Nadar, undertook a series of traumatic-injury impact studies using several different species of primates, particularly ], in order to more fully understand the role ] plays in dream pathology. Solms' experiments proved inconclusive, however, as the high mortality rate associated with using an hydraulic impact pin to artificially produce brain damage in test subjects meant that his final candidate pool was too small to satisfy the requirements of the ]. | |||

| From the 1940s to 1985, ] collected more than 50,000 dream reports at ]. In 1966, Hall and Robert Van de Castle published ''The Content Analysis of Dreams'', in which they outlined a coding system to study 1,000 dream reports from college students.<ref name="hallcontent">Hall, C., & Van de Castle, R. (1966). The Content Analysis of Dreams. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts. {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070412100915/http://psych.ucsc.edu/dreams/Info/content_analysis.html |date=12 April 2007}}</ref> Results indicated that participants from varying parts of the world demonstrated similarity in their dream content. The only residue of antiquity's authoritative dream figure in the Hall and Van de Castle listing of dream characters is the inclusion of God in the category of prominent persons.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://dreams.ucsc.edu/Coding/characters.html |title=The Classification and Coding of Characters |last1=Schneider |first1=Adam |last2=Domhoff |first2=G. William |publisher=University of California at Santa Cruz |access-date=17 July 2021}}</ref> Hall's complete dream reports were made publicly available in the mid-1990s by his protégé ]. More recent studies of dream reports, while providing more detail, continue to cite the Hall study favorably.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Schredl |first1=Michael |last2=Ciric |first2=Petra |last3=Götz |first3=Simon |last4=Wittmann |first4=Lutz |date=November 2004 |title=Typical Dreams: Stability and Gender Differences |journal=The Journal of Psychology |volume=138 |issue=6 |doi=10.3200/JRLP.138.6.485-494 |pmid=15612605 |pages=485–494 |s2cid=13554573}}</ref> | |||

| ===Dreams and memory=== | |||

| Eugen Tarnow suggests that dreams are ever-present excitations of ], even during waking life. The strangeness of dreams is due to the format of long-term memory, reminiscent of ] and Rasmussen’s findings that electrical excitations of the ] give rise to experiences similar to dreams. During waking life an executive function interprets long term memory consistent with reality checking. Tarnow's theory is a reworking of Freud's theory of dreams in which Freud's unconscious is replaced with the long-term memory system and Freud's “Dream Work” describes the structure of long-term memory.<ref>{{cite book | |||

| | last = Tarnow | |||

| | first = Eugen | |||

| | year = 2003 | |||

| | title = How Dreams And Memory May Be Related | |||

| | publisher = NEURO-PSYCHOANALYSIS | |||

| | edition = 5(2) | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| ====Hippocampus and memory==== | |||

| ] (1858–1925).]] | |||

| A 2001 study showed evidence that illogical locations, characters, and dream flow may help the brain strengthen the linking and consolidation of ]. These conditions may occur because, during REM sleep, the flow of information between the ] and ] is reduced.<ref>{{cite journal | |||

| | author = R. Stickgold, J. A. Hobson, R. Fosse, M. Fosse | |||

| | date = | |||

| | year = 2001 | |||

| | month = october | |||

| | title = Sleep, Learning, and Dreams: Off-line Memory Reprocessing | |||

| | journal = Science | |||

| | volume = 294 | |||

| | issue = 5544 | |||

| | pages = 1052–1057 | |||

| | doi = 10.1126/science.1063530 | |||

| }}</ref> Increasing levels of the ] hormone ] late in sleep (often during REM sleep) cause this decreased communication. One stage of ] is the linking of distant but related memories. Payne and Nadel hypothesize that these memories are then consolidated into a smooth narrative, similar to a process that happens when memories are created under stress.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Jessica D. Payne and Lynn Nadel1 | year = 2004 | title = Sleep, dreams, and memory consolidation: The role of the stress hormone cortisol | journal = Learning & Memory | pages = 671–678 | issn = 1072-0502 | url=http://www.learnmem.org/cgi/content/full/11/6/671 | pmid = 15576884 | doi = 10.1101/lm.77104 | volume = 11 }}</ref> | |||

| In the Hall study, the most common emotion experienced in dreams was ]. Other emotions included ], ], ], ], and ]. ]s were much more common than positive ones.<ref name="hallcontent"/> The Hall data analysis showed that sexual dreams occur no more than 10% of the time and are more prevalent in young to mid-teens.<ref name="hallcontent"/> Another study showed that 8% of both men's and women's dreams have sexual content.<ref>Zadra, A., {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070927222607/http://www.journalsleep.org/PDF/AbstractBook2007.pdf |date=27 September 2007}}, ''Sleep'' Volume 30, Abstract Supplement, 2007 A376.</ref> In some cases, sexual dreams may result in ]s or ]s. These are colloquially known as "wet dreams".<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.measuredhs.com/pubs/pdf/FR157/04Chapter04.pdf |title=Badan Pusat Statistik "Indonesia Young Adult Reproductive Health Survey 2002–2004" p. 27 |access-date=4 April 2013 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121209171035/http://measuredhs.com/pubs/pdf/FR157/04Chapter04.pdf |archive-date=9 December 2012}}</ref> | |||

| ===Functional hypotheses=== | |||

| The visual nature of dreams is generally highly phantasmagoric; that is, different locations and objects continuously blend into each other. The visuals (including locations, people, and objects) are generally reflective of a person's memories and experiences, but conversation can take on highly exaggerated and bizarre forms. Some dreams may even tell elaborate stories wherein the dreamer enters entirely new, complex worlds and awakes with ideas, thoughts and feelings never experienced prior to the dream. | |||

| There are many hypotheses about the function of dreams, including:<ref name ="cartwrightcontent">{{cite encyclopedia | |||

| | year = 1993 | |||

| | title = Functions of Dreams | |||

| | encyclopedia = Encyclopedia of Sleep and Dreaming | |||

| | last = Cartwright | |||

| | first = Rosalind D | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| * During the night there may be many external stimuli bombarding the senses, but the mind interprets the stimulus and makes it a part of a dream in order to ensure continued sleep.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia | |||

| | year = 1993 | |||

| | title = Characteristics of Dreams | |||

| | encyclopedia = Encyclopedia of Sleep and Dreaming | |||

| | last = Antrobus | |||

| | first = John | |||

| }}</ref> The mind will, however, awaken an individual if they are in danger or if trained to respond to certain sounds, such as a baby crying. | |||

| * Dreams allow the repressed parts of the mind to be satisfied through fantasy while keeping the conscious mind from thoughts that would suddenly cause one to awaken from shock.<ref>{{cite book | |||

| | last = Vedfelt | |||

| | first = Ole | |||

| | title = The Dimensions of Dreams | |||

| | publisher = Fromm | |||

| | year = 1999 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| People who are blind from birth do not have visual dreams. Their dream contents are related to other senses, such as ], ], ], and ], whichever are present since birth.<ref>{{cite news |title=How do blind people dream? – The Body Odd |url=http://bodyodd.nbcnews.com/_news/2012/03/09/10602730-how-do-blind-people-dream?lite |date=March 2012 |access-date=10 May 2013 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130124114342/http://bodyodd.nbcnews.com/_news/2012/03/09/10602730-how-do-blind-people-dream?lite |archive-date=24 January 2013}}</ref> | |||

| * Freud suggested that bad dreams let the brain learn to gain control over emotions resulting from distressing experiences.<ref name ="cartwrightcontent"/> | |||

| * ] suggested that dreams may compensate for one-sided attitudes held in waking consciousness.<ref>Jung, C. (1948) General aspects of dream psychology. In: ''Dreams.'' Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 23-66.</ref> | |||

| * Ferenczi<ref>Ferenczi, S. (1913)To whom does one relate one's dreams? In: ''Further Contributions to the Theory and Technique of Psycho-Analysis.'' New York: Brunner/Mazel, 349.</ref> proposed that the dream, when told, may communicate something that is not being said outright. | |||

| * Dreams are like the cleaning-up operations of computers when they are off-line, removing parasitic nodes and other "junk" from the mind during sleep.<ref>Evans, C. & Newman, E. (1964) Dreaming: An analogy from computers. ''New Scientist'', 419:577-579.</ref><ref>Crick, F. & Mitchison, G. (1983) The function of dream sleep. ''Nature'', 304:111-114.</ref> | |||

| * Dreams create new ideas through the generation of random thought mutations. Some of these may be rejected by the mind as useless, while others may be seen as valuable and retained. Blechner<ref>Blechner, M. (2001) ''The Dream Frontier''. Hillsdale, NJ: The Analytic Press.</ref> calls this the theory of "Oneiric Darwinism." | |||

| * Dreams regulate mood.<ref>Kramer, M. (1993)The selective mood regulatory function of dreaming: An update and revision. In: ''The Function of Dreaming''. Ed., A. Moffitt, M. Kramer, & R. Hoffmann. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.</ref> | |||

| * Hartmann<ref>Hartmann, E. (1995)Making connections in a safe place: Is dreaming psychotherapy? ''Dreaming'', 5:213-228.</ref> says dreams may function like psychotherapy, by "making connections in a safe place" and allowing the dreamer to integrate thoughts that may be dissociated during waking life. | |||

| * More recent research by Griffin has led to the formulation of the 'expectation fulfillment theory of dreaming', which suggests that dreaming metaphorically completes patterns of emotional expectation and lowers stress levels.<ref>Griffin, J. (1997) The Origin of Dreams: How and why we evolved to dream. ''The Therapist'', Vol 4 No 3.</ref><ref>Griffin, J, Tyrrell, I. (2004) Dreaming Reality: how dreaming keeps us sane or can drive us mad'. Human Givens Publishing.</ref> | |||

| * Coutts<ref>Coutts, R (2008). Dreams as modifiers and tests of mental schemas: an emotional selection hypothesis. Psychological Reports, 102, 561-574.</ref> hypothesizes that dreams modify and test mental schemas during sleep during a process he calls ], and that only schema modifications that appear emotionally adaptive during dream tests are selected for retention, while those that appear maladaptive are abandoned or further modified and tested. | |||

| * Dreams are a product of "dissociated imagination", which is dissociated from the conscious self and draws material from sensory memory for simulation, with sensory feedback resulting in hallucination. By simulating the sensory signals to drive the autonomous nerves, dreams can effect mind-body interaction. In the brain and spine, the autonomous "repair nerves", which can expand the blood vessels, connect with pain and compression nerves. These nerves are grouped into many chains called meridians in Chinese medicine. While dreaming, the body also employs the chain-reacting meridians to repair the body and help it grow and develop by sending out very intensive movement-compression signals when the level of growth enzymes increase. <ref>{{cite web | year = 1995 | title = A Mind-Body Interaction Theory of Dream | url = http://myweb.ncku.edu.tw/~ydtsai/mindbody/ }}</ref> | |||

| == Neurophysiology == | |||

| ===Dreams and psychosis=== | |||

| {{Main|Cognitive neuroscience of dreams}} | |||

| {{Further|Neuroscience of sleep}} | |||

| Dream study is popular with scientists exploring the ]. Some "propose to reduce aspects of dream phenomenology to neurobiology."<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Hobson |first1=J. Allan |last2=Pace-Schott |first2=Edward F. |last3=Stickgold |first3=Robert |author-link1=Allan Hobson |title=Dream science 2000: A response to commentaries on ''Dreaming and the Brain'' |journal=Behavioral and Brain Sciences |year=2000 |volume=23 |issue=6 |page=1019 |doi=10.1017/S0140525X00954025 |s2cid=144729368}}</ref> But current science cannot specify dream physiology in detail. Protocols in most nations restrict human brain research to non-invasive procedures. In the United States, invasive brain procedures with a human subject are allowed only when these are deemed necessary in surgical treatment to address medical needs of the same human subject.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Chiong |first1=Winston |last2=Leonard |first2=Matthew K. |last3=Chang |first3=Edward F. |title=Neurosurgical Patients as Human Research Subjects: Ethical Considerations in Intracranial Electrophysiology Research |journal=Neurosurgery |year=2018 |volume=83 |issue=1 |pages=29–37 |doi=10.1093/neuros/nyx361 |pmid=28973530 |url=https://academic.oup.com/neurosurgery/article-abstract/83/1/29/3988112 |pmc=5777911}}</ref> Non-invasive measures of brain activity like ] (EEG) voltage averaging or ] cannot identify small but influential neuronal populations.<ref name="hob">Hobson, J. A., Pace-Schott, E. F., & Stickgold, R. (2000). "Dreaming and the brain: Toward a cognitive neuroscience of conscious states". ''Behavioral and Brain Sciences'', 23(6), 793–842.</ref> Also, ] signals are too slow to explain how brains compute in real time.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://speakingofresearch.com/2009/07/31/the-limits-of-fmri/ |title=The limits of fMRI |last=Ringach |first=Dario L. |date=30 July 2009 |publisher=Speaking of Research |access-date=18 July 2021}}</ref> | |||

| A number of thinkers have commented on the similarities between the ] of dreams and that of ]. Features common to the two states include thought disorder, flattened or inappropriate affect (emotion), and ]. Among philosophers, ], for example, wrote that ‘the lunatic is a wakeful dreamer’.<ref>Quoted in La Barre, W. (1975). Anthropological Perspectives on Hallucination and Hallucinogens. In R.K. Siegel and L.J. West (eds.), ''Hallucinations: Behavior, Experience, and Theory''. New York: Wiley.</ref> ] said: ‘A dream is a short-lasting psychosis, and a psychosis is a long-lasting dream.’<ref>''Ibid''.</ref>In the field of ], ] wrote: ‘A dream then, is a psychosis’,<ref>Freud, S. (1940). ''An Outline of Psychoanalysis''. London: Hogarth Press.</ref>and ]: ‘Let the dreamer walk about and act like one awakened and we have the clinical picture of '']''.’<ref>Jung, C.G. (1909). ''The Psychology of Dementia Praecox'', translated by F. Peterson and A.A. Brill. New York: The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease Publishing Company. </ref> | |||

| Scientists researching some brain functions can work around current restrictions by examining animal subjects. As stated by the ], "Because no adequate alternatives exist, much of this research must '''' be done on animal subjects."<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.sfn.org/Advocacy/Policy-Positions/Policies-on-the-Use-of-Animals-and-Humans-in-Research |title=Policies on the Use of Animals and Humans in Research |publisher=Society for Neuroscience |access-date=18 July 2021}}</ref> However, since animal dreaming can be only inferred, not confirmed, animal studies yield no hard facts to illuminate the neurophysiology of dreams. Examining human subjects with brain lesions can provide clues, but the lesion method cannot discriminate between the effects of destruction and disconnection and cannot target specific neuronal groups in heterogeneous regions like the brain stem.<ref name="hob"/> | |||

| McCreery<ref>McCreery, C. (1997). Hallucinations and arousability: pointers to a theory of psychosis. In Claridge, G. (ed.): ''Schizotypy, Implications for Illness and Health''. Oxford: Oxford University Press. </ref><ref>McCreery, C. (2008). Dreams and psychosis: a new look at an old hypothesis. ''Psychological Paper No. 2008-1''. Oxford: Oxford Forum. </ref> | |||

| has sought to explain these similarities by reference to the fact, documented by Oswald,<ref>Oswald, I. (1962). ''Sleeping and Waking: Physiology and Psychology''. Amsterdam: Elsevier.</ref> that sleep can supervene as a reaction to extreme stress and hyper-]. McCreery adduces evidence that psychotics are people with a tendency to hyper-arousal, and suggests that this renders them prone to what Oswald calls ‘]’ during waking life. He points in particular to the paradoxical finding of Stevens and Darbyshire<ref>Stevens, J.M. and Darbyshire, A.J. (1958). Shifts along the alert-repose continuum during remission of catatonic ‘stupor’with amobarbitol. ''Psychosomatic Medicine'', '''20''', 99-107.</ref> that patients suffering from ] can be roused from their seeming stupor by the administration of sedatives rather than stimulants. | |||

| == |

== Generation == | ||

| ]'', 1655, by ]]] | |||

| ] | |||

| Denied precision tools and obliged to depend on imaging, much dream research has succumbed to the ]. Studies detect an increase of blood flow in a specific brain region and then credit that region with a role in generating dreams. But pooling study results has led to the newer conclusion that dreaming involves large numbers of regions and pathways, which likely are different for different dream events.<ref>{{cite book |last=Uttal |first=William R. |author-link=William Uttal |title=Reliability in Cognitive Neuroscience |date=2013 |location=Cambridge, MA |publisher=The MIT Press|quote=Similarly, modern neuroscience research is increasingly showing that activation areas on the brain associated with a cognitive process are far more widely distributed than had been thought only a decade or so ago. Indeed, it now seems likely that most of the brain is active in almost any cognitive process. |page=4}}</ref> | |||

| Dreams have a long history both as a subject of conjecture and as a source of inspiration. Throughout their history, people have sought ] or ]. They have been described ] as a response to neural processes during sleep, ] as reflections of the ], and ] as messages from ] or predictions of the future. Many cultures practiced ], with the intention of cultivating dreams that were ] or contained messages from the ]. | |||

| Image creation in the brain involves significant neural activity downstream from eye intake, and it is theorized that "the visual imagery of dreams is produced by activation during sleep of the same structures that generate complex visual imagery in waking perception."<ref>{{cite journal |last=Solms |first=Mark |author-link=Mark Solms |title=Dreaming and REM sleep are controlled by different brain mechanisms |journal=Behavioral and Brain Sciences |year=2000 |volume=23 |issue=6 |pages=843–850; discussion 904–1121 |doi=10.1017/S0140525X00003988 |pmid=11515144 |s2cid=7264870}}</ref> | |||

| ] has a traditional ceremony called hatovat chalom – literally meaning making the dream a good one. Through this rite disturbing dreams can be transformed to give a positive interpretation by a rabbi or a rabbinic court. <ref>http://www.rabbiwein.com/Jerusalem-Post/2006/02/102.html Berel Wein "DREAMS"</ref> | |||

| Dreams present a running narrative rather than exclusively visual imagery. Following their work with ] subjects, ] and ] postulated, without attempting to specify the neural mechanisms, a "]" that seeks to create a plausible narrative from whatever electro-chemical signals reach the brain's left hemisphere. Sleep research has determined that some brain regions fully active during waking are, during REM sleep, activated only in a partial or fragmentary way.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Braun |first1=A. R. |last2=Balkin |first2=T. J |last3=Wesensten |first3=N. J. |last4=Carson |first4=R. E. |last5=Varga |first5=M. |last6=Baldwin |first6=P. |last7=Selbie |first7=S. |last8=Belenky |first8=G. |last9=Herscovitch |first9=P. |year=1997 |title=Regional cerebral blood flow through the sleep-wake cycle |journal=Brain |volume=120 |publisher=Oxford University Press |pages=1173–1197 |doi=10.1093/brain/120.7.1173 |pmid=9236630 |doi-access=free}}</ref> Drawing on this knowledge, textbook author James W. Kalat explains, " dream represents the brain's effort to make sense of sparse and distorted information.... The cortex combines this haphazard input with whatever other activity was already occurring and does its best to synthesize a story that makes sense of the information."<ref>{{cite book |last=Kalat |first=James W. |date=2015 |title=Biological Psychology |edition=12th |location=Boston |publisher=Cengage |page=288 |isbn=978-1305105409}}</ref> Neuroscientist ] is even more blunt, calling often bizarre dream content "just the result of your interpreter trying to create a story out of random neural signaling."<ref>{{cite book |last=Viskontas |first=Indre |date=2017 |title=Brain Myths Exploded: Lessons from Neuroscience |location=Chantilly, VA |publisher=The Teaching Company |page=393}}</ref> | |||

| ===Popular culture=== | |||

| Modern ] often conceives of dreams, like Freud, as expressions of the dreamer's deepest fears and desires.<ref name="Van Riper 56">{{cite book|last=Van Riper|first=A. Bowdoin|title=Science in popular culture: a reference guide|publisher=]|location=Westport|date=2002|pages=56|isbn=0–313–31822–0}}</ref> In films such as '']'' (1945) or '']'' (1962), the heroes must extract vital clues from surreal dreams.<ref name="Van Riper 57">Van Riper, op.cit., p. 57.</ref> | |||

| == Theories on function == | |||

| Most dreams in popular culture are, however, not symbolic, but straightforward and realistic depictions of their dreamer's fears and desires.<ref name="Van Riper 57" /> Dream scenes may be indistinguishable from those set in the dreamer's real world, a narrative device that undermines the dreamer's and the audience's sense of security<ref name="Van Riper 57" /> and allows ] protagonists, such as those of '']'' (1976), '']'' (1980) or '']'' (1981) to be suddenly attacked by dark forces while resting in seemingly safe places.<ref name="Van Riper 57" /> ]'s short story '']'' (1891) tells of a man sentenced to death escaping the execution and returning to safety, only to wake up and realise that he is in fact about to be hanged.<ref name="Van Riper 57" /> | |||

| {{Main|Oneirology}} | |||

| {{Further|Rapid eye movement sleep}} | |||

| For many humans across multiple eras and cultures, dreams are believed to have functioned as revealers of truths sourced during sleep from gods or other external entities.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Ribeiro |first=Sidarta |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1200037413 |title=The oracle of night : the history and science of dreams |date=2021 |others=Daniel Hahn, Sidarta Translation of: Ribeiro |isbn=978-1-5247-4690-2 |edition= |location=New York |oclc=1200037413}}</ref> Ancient Egyptians believed that dreams were the best way to receive divine revelation, and thus they would induce (or "incubate") dreams. They went to sanctuaries and slept on special "dream beds" in hope of receiving advice, comfort, or healing from the gods.<ref name="Krippner1"/> From a Darwinian perspective dreams would have to fulfill some kind of biological requirement, provide some benefit for natural selection to take place, or at least have no negative impact on fitness. Robert (1886),<ref>Robert, W. Der Traum als Naturnothwendigkeit erklärt. Zweite Auflage, Hamburg: Seippel, 1886.</ref> a physician from Hamburg, was the first who suggested that dreams are a need and that they have the function to erase (a) sensory impressions that were not fully worked up, and (b) ideas that were not fully developed during the day. In dreams, incomplete material is either removed (suppressed) or deepened and included into memory. ], whose dream studies focused on interpreting dreams, not explaining how or why humans dream, disputed Robert's hypothesis<ref>{{cite book |last=Freud |first=Sigmund |translator=James Strachey |editor=James Strachey |author-link=Sigmund Freud |date=1965 |title=The Interpretation of Dreams |page=188 |location=New York |publisher=Avon |quote=The view adopted by Robert that the purpose of dreams is to unburden our memory of the useless impressions of daytime is plainly no longer tenable....}}</ref> and proposed that dreams preserve sleep by representing as fulfilled those wishes that otherwise would awaken the dreamer.<ref>Rycroft, Charles. ''A Critical Dictionary of Psychoanalysis''. London: Penguin Books, 1995, p. 41.</ref> Freud wrote that dreams "serve the purpose of prolonging sleep instead of waking up. ''Dreams are the'' GUARDIANS ''of sleep and not its disturbers.''"<ref>{{cite book |last=Freud |first=Sigmund |translator=James Strachey |editor=James Strachey |author-link=Sigmund Freud |date=1965 |title=The Interpretation of Dreams |page=253 |location=New York |publisher=Avon}}</ref> | |||

| In ], the line between dreams and reality may be blurred even more in the service of the story.<ref name="Van Riper 57" /> Dreams may be psychically invaded or manipulated (the '']'' films, 1984–1991) or even come literally true (as in '']'', 1971). Such stories play to audiences’ experiences with their own dreams, which feel as real to them as the real world that inspires them.<ref name="Van Riper 57" /> | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ==Dream content== | |||

| From the 1940s to 1985, ] collected more than 50,000 dream reports at ]. In 1966 Hall and Van De Castle published ''The Content Analysis of Dreams'' in which they outlined a coding system to study 1,000 dream reports from college students.<ref name="hallcontent">Hall, C., & Van de Castle, R. (1966). The Content Analysis of Dreams. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts. </ref> It was found that people all over the world dream of mostly the same things. Hall's complete dream reports became publicly available in the mid-1990s by Hall's protégé ], allowing further different analysis. | |||

| A turning point in theorizing about dream function came in 1953, when ] published the ] and ] paper<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Aserinsky |first1=Eugene |last2=Kleitman |first2=Nathaniel |author-link=Eugene Aserinsky |title=Regularly Occurring Periods of Eye Motility, and Concomitant Phenomena, during Sleep |journal=Science |year=1953 |volume=118 |issue=3062 |pages=273–274 |doi=10.1126/science.118.3062.273 |pmid=13089671 |bibcode=1953Sci...118..273A}}</ref> establishing ] as a distinct phase of sleep and linking dreams to REM sleep.<ref>{{Citation |last=Smith |first=Robert C. |contribution=The Meaning of Dreams: A Current Warning Theory |editor-last1=Gackenbach |editor-first1=Jayne |editor-last2=Sheikh |editor-first2=Anees A. |title=Dream Images: A Call to Mental Arms |year=1991 |pages=127–146 |place=Amityville, NY |publisher=Baywood |isbn=0-89503-056-X}}</ref> Until and even after publication of the Solms 2000 paper that certified the separability of REM sleep and dream phenomena,<ref name="Solms1"/> many studies purporting to uncover the function of dreams have in fact been studying not dreams but measurable REM sleep. | |||

| Personal experiences from the last day or week are frequently incorporated into dreams.<ref name="day-residue" /> | |||

| Theories of dream function since the identification of REM sleep include: | |||

| ===Emotions=== | |||

| The most common emotion experienced in dreams is ]. Negative emotions are more common than positive ones.<ref name="hallcontent"/> The U.S. ranks the highest amongst industrialized nations for aggression in dreams with 50 percent of U.S. males reporting aggression in dreams, compared to 32 percent for Dutch men.<ref name="hallcontent"/> | |||

| ] and ] 1977 ], which proposed "a functional role for dreaming sleep in promoting some aspect of the learning process...."<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Hobson |first1=J. Allan |last2=McCarley |first2=Robert W. |title=The Brain as a Dream State Generator: An Activation-Synthesis Hypothesis of the Dream Process |journal=The American Journal of Psychiatry |date=December 1977 |volume=134 |issue=12 |pages=1335–1348 |doi=10.1176/ajp.134.12.1335 |pmid=21570 |quote=The dream process is thus seen as having its origin in sensorimotor systems, with little or no primary ideational, volitional, or emotional content. This concept is markedly different from that of the "dream thoughts" or wishes seen by Freud as the primary stimulus for the dream.}}</ref> In 2010 a Harvard study was published showing experimental evidence that dreams were correlated with improved learning.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Benjamin |first1=Victoria |title=Study Links Dreaming to Increased Memory Performance |url=https://www.thecrimson.com/article/2010/4/27/maze-wamsley-group-navigating/#:~:text=A%20recent%20study%20published%20last,nap%2C%20according%20to%20Erin%20J. |website=The Harvard Crimson |access-date=27 January 2022}}</ref> | |||

| ===Sexual content=== | |||

| The Hall data analysis shows that sexual dreams occur no more than 10 percent of the time and are more prevalent in young to mid teens.<ref name="hallcontent"/> Another study showed that 8% of men's and women's dreams have sexual content.<ref>Zadra, A., ''SLEEP'', Volume 30, Abstract Supplement, 2007 A376.</ref> In some cases, sexual dreams may result in ] or ]. These are commonly known as wet dreams.<ref>http://www.measuredhs.com/pubs/pdf/FR157/04Chapter04.pdf Badan Pusat Statistik "Indonesia Young Adult Reproductive Health Survey 2002-2004" p. 27</ref> | |||

| ] and Mitchison's 1983 "]" theory, which states that dreams are like the cleaning-up operations of computers when they are offline, removing (suppressing) parasitic nodes and other "junk" from the mind during sleep.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Evans |first1=C. |last2=Newman |first2=E. |year=1964 |title=Dreaming: An analogy from computers |journal=New Scientist |volume=419 |pages=577–579}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |doi=10.1038/304111a0 |last1=Crick |first1=F. |last2=Mitchison |first2=G. |year=1983 |title=The function of dream sleep |journal=Nature |volume=304 |issue=5922 |pages=111–114 |pmid=6866101 |bibcode=1983Natur.304..111C |s2cid=41500914}}</ref> | |||

| ===Recurring dreams=== | |||

| ] 1995 proposal that dreams serve a "quasi-therapeutic" function, enabling the dreamer to process trauma in a safe place.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Hartmann |first=Ernest |title=Making Connections in a Safe Place: Is Dreaming Psychotherapy? |journal=Dreaming |year=1995 |volume=5 |issue=4 |pages=213–228 |doi=10.1037/h0094437}}</ref> | |||

| While the content of most dreams is dreamt only once, many people experience recurring dreams—that is, the same dream narrative is experienced over different occasions of sleep. Up to 70% of females and 65% of males report recurrent dreams.<ref>Van de Castle, p. 340.</ref> | |||

| ] 2000 threat simulation hypothesis, whose premise is that during much of human evolution, physical and interpersonal threats were serious, giving reproductive advantage to those who survived them. Dreaming aided survival by replicating these threats and providing the dreamer with practice in dealing with them.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Revonsuo |first=A. |title=The reinterpretation of dreams: an evolutionary hypothesis of the function of dreaming |journal=Behavioral and Brain Sciences |year=2000 |volume=23 |issue=6 |pmid=11515147 |doi=10.1017/S0140525X00004015 |pages=877–901 |s2cid=145340071}}</ref> In 2015, Revonsuo proposed social simulation theory, which describes dreams as a simulation for training social skills and bonds.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Revonsuo |first1=A. |last2=Tuominen |first2=J. |year=2015 |title=Avatars in the Machine: Dreaming as a Simulation of Social Reality |journal=Open MIND |pages=1–28 |doi=10.15502/9783958570375|isbn=9783958570375 }}</ref> | |||

| ===Common themes=== | |||

| Content-analysis studies have identified common reported themes in dreams. These include: situations relating to school, being chased, running slowly in place, experiences, falling, arriving too late, a person now alive being dead, teeth falling out, flying, future events such as birthdays, anniversaries, etc. (with different scenarios), embarrassing moments, falling in love with random people, failing an examination, not being able to move, not being able to focus vision, car accidents, being accused of a crime you didn't commit and many more. | |||

| ] and ] 2021 defensive activation theory, which says that, given the brain's ], dreams evolved as a visual hallucinatory activity during sleep's extended periods of darkness, busying the occipital lobe and thereby protecting it from possible appropriation by other, non-vision, sense operations.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Eagleman |first1=David M. |last2=Vaughn |first2=Don A. |title=The Defensive Activation Theory: REM Sleep as a Mechanism to Prevent Takeover of the Visual Cortex |journal=Frontiers in Neuroscience |date=May 2021 |volume=15 |page=632853 |doi=10.3389/fnins.2021.632853 |pmid=34093109 |pmc=8176926 |doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| ===Color vs. Black and White=== | |||

| Twelve percent of people dream only in black and white.<ref>{{cite journal | |||

| | author = Michael Schredl, Petra Ciric, Simon Götz, Lutz Wittmann | |||

| | date= November, 2004 | |||

| | year = 2004 | |||

| | month = November | |||

| | title = Typical Dreams: Stability and Gender Differences | |||

| | journal = The Journal of Psychology | |||

| | volume = 138 | |||

| | issue = 6 | |||

| | pages = 485 () | |||

| }}</ref> Studies from 1915 through to the 1950s maintained that the majority of dreams were in black and white, but these results began to change in the 1960s. Today, only 4.4 % of the dreams of under-25 year-olds are in black and white. Recent research has suggested that those changing results may be linked to the switch from black-and-white film and TV to color media.<ref>{{cite journal | |||

| | author = Richard Alleyne | |||

| | date= October 17, 2008 | |||

| | year = 2008 | |||

| | month = October | |||

| | title = Black and white TV generation have monochrome dreams | |||

| | journal = Telegraph | |||

| | volume = | |||

| | issue = | |||

| | pages = (http://www.telegraph.co.uk/earth/main.jhtml?view=DETAILS&grid=&xml=/earth/2008/10/17/scidream117.xml Article]) | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| ] proposes, based on artificial neural networks, that dreams prevent overfitting to past experiences; that is, they enable the dreamer to learn from novel situations.<ref>{{cite news |title=Weird dreams train us for the unexpected, says new theory |url=https://www.theguardian.com/science/2021/may/14/weird-dreams-train-us-for-the-unexpected-says-new-theory |access-date=5 January 2023 |work=the Guardian |date=14 May 2021 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Hoel |first1=Erik |title=The overfitted brain: Dreams evolved to assist generalization |journal=Patterns |date=14 May 2021 |volume=2 |issue=5 |pages=100244 |doi=10.1016/j.patter.2021.100244 |pmid=34036289 |pmc=8134940 |language=en |issn=2666-3899|doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| ==Relationship with mental conditions== | |||

| == Religious and other cultural contexts == | |||

| There is evidence that certain medical conditions (normally only neurological conditions) can impact dreams. For instance, people with ] have never reported black-and-white dreaming, and often have a difficult time imagining the idea of dreaming in only black and white.<ref>{{cite book |title=Synaesthesia: The Strangest Thing |last=Harrison |first=John E. |year=2001 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=0192632450 }}</ref> | |||

| Dreams figure prominently in major world religions. The dream experience for early humans, according to one interpretation, gave rise to the notion of a human "]",<ref>{{cite book |last=Lévy-Bruhl |first=Lucien |author-link=Lucien Lévy-Bruhl |date=1923 |title=Primitive Mentality |translator=Lilian A. Clare |chapter=Chapter III Dreams |chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/primitivementali00levy_0/page/98/mode/2up?ref=ol&view=theater |location=New York |publisher=Macmillan |page=98 |quote=...n dreams,...man passes from the one world to the other without being aware of it. Such is in fact the ordinary idea of the dream to primitive peoples. The "soul" leaves its tenement for the time being. It frequently goes very far away; it communes with spirits or with ghosts. At the moment of awakening it returns to take its place in the body once more.}}</ref> a central element in much religious thought. ] wrote: <blockquote>But there can be no reasonable doubt that the idea of a soul must have first arisen in the mind of primitive man as a result of observation of his dreams. Ignorant as he was, he could have come to no other conclusion but that, in dreams, he left his sleeping body in one universe and went wandering off into another. It is considered that, but for that savage, the idea of such a thing as a 'soul' would never have even occurred to mankind....<ref>{{cite book |last=Dunne |first=J. W. |date=1950 |orig-date=1927 |title=An Experiment with Time |location=London |publisher=Faber |page=23}}</ref></blockquote> | |||

| === Hindu === | |||

| Therapy for recurring ] (often associated with ]) can include imagining alternative scenarios that could begin at each step of the dream.<ref name="npr" /> | |||

| In the ], part of the ] scriptures of ], a dream is one of three states that the soul experiences during its lifetime, the other two states being the waking state and the sleep state.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.swami-krishnananda.org/mand/mand_4.html |title=The Mandukya Upanishad, Section 4 |last=Krishnananda |first=Swami |date=16 November 1996 |access-date=26 March 2015 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150409004128/http://www.swami-krishnananda.org/mand/mand_4.html |archive-date=9 April 2015}}</ref> The earliest ], written before 300 BCE, emphasize two meanings of dreams. The first says that dreams are merely expressions of inner desires. The second is the belief of the soul leaving the body and being guided until awakened. | |||

| == |

=== Abrahamic === | ||

| ], c. 1690. ]]] | |||

| In Judaism, dreams are considered part of the experience of the world that can be interpreted and from which lessons can be garnered. It is discussed in the Talmud, Tractate Berachot 55–60. | |||

| {{main|Dream interpretation}} | |||

| The ancient ] connected their dreams heavily with their religion, though the Hebrews were ] and believed that dreams were the voice of one God alone. Hebrews also differentiated between good dreams (from God) and bad dreams (from evil spirits). The Hebrews, like many other ancient cultures, incubated dreams in order to receive a divine revelation. For example, the Hebrew prophet ] would "lie down and sleep in the temple at ] before the Ark and receive the word of the Lord", and ] interpreted a Pharaoh's dream of seven lean cows swallowing seven fat cows as meaning the subsequent seven years would be bountiful, followed by seven years of famine. Most of the dreams in the ] are in the ].<ref>{{cite book |url={{Google books |id=zs3gup4iFu4C |page=15 |plainurl=yes}} |title=A letter that has not been read: Dreams in the Hebrew Bible |first=Shaul |last=Bar |publisher=Hebrew Union College Press |year=2001 |access-date=4 April 2013}}</ref> | |||

| Dreams were historically used for healing (as in the ]s found in the ] temples of ]) as well as for guidance or divine inspiration. Some ] tribes used ]s as a rite of passage, fasting and praying until an anticipated guiding dream was received, to be shared with the rest of the tribe upon their return.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.dreams.ca/dreams.htm |last=Webb |first=Craig |year=1995 |title= Dreams: Practical Meaning & Appications |publisher= The DREAMS Foundation}}</ref> | |||

| ] mostly shared the beliefs of the Hebrews and thought that dreams were of a supernatural character because the ] includes frequent stories of dreams with divine inspiration. The most famous of these dream stories was ] that stretches from Earth to ]. Many Christians preach that God can speak to people through their dreams. The famous glossary, the ], written in the name of ], attempted to teach Christian populations to interpret their dreams. | |||

| During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, both ] and ] identified dreams as an interaction between the ] and the ]. They also assert together that the unconscious is the dominant force of the dream, and in dreams it conveys its own mental activity to the perceptive faculty. While Freud felt that there was an active censorship against the unconscious even during sleep, Jung argued that the dream's bizarre quality is an efficient language, comparable to poetry and uniquely capable of ''revealing'' the underlying meaning. | |||

| ] has researched the role of dreams in ].<ref>{{cite book |last=Edgar |first=Iain |title=The Dream in Islam: From Qur'anic Tradition to Jihadist Inspiration |year=2011 |publisher=Berghahn Books |location=Oxford |isbn=978-0-85745-235-1 |page=178 |url=http://www.berghahnbooks.com/title.php?rowtag=EdgarDream |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110929125708/http://www.berghahnbooks.com/title.php?rowtag=EdgarDream |archive-date=29 September 2011 |access-date=9 March 2012}}</ref> He has argued that dreams play an important role in the history of Islam and the lives of Muslims, since dream interpretation is the only way that Muslims can receive revelations from God since the death of the last prophet, ].<ref name="Iain">{{cite journal |last=Edgar |first=Iain R. |author2=Henig, David |title=Istikhara: The Guidance and practice of Islamic dream incubation through ethnographic comparison |journal=History and Anthropology |date=September 2010 |volume=21 |issue=3 |pages=251–262 |doi=10.1080/02757206.2010.496781 |url=https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/10630.pdf |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171108072540/https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/10630.pdf |archive-date=8 November 2017 |citeseerx=10.1.1.1012.7334 |s2cid=144463607 |access-date=26 October 2017}}</ref> According to Edgar, Islam classifies three types of dreams. Firstly, there is the true dream (al-ru’ya), then the false dream, which may come from the devil (]), and finally, the meaningless everyday dream (hulm). This last dream could be brought forth by the dreamer's ego or base appetite based on what they experienced in the real world. The true dream is often indicated by Islam's ] tradition.<ref name="Iain"/> In one narration by ], the wife of the Prophet, it is said that the Prophet's dreams would come true like the ocean's waves.<ref name="Iain"/> Just as in its predecessors, the ] also recounts the story of Joseph and his unique ability to interpret dreams.<ref name="Iain"/> | |||

| ] presented his theory of dreams as part of the holistic nature of ]. Dreams are seen as projections of parts of the self that have been ignored, rejected, or ].<ref>{{cite journal|author=Wegner, D.M., Wenzlaff, R.M. & Kozak M.|year=2004|title=The Return of Suppressed Thoughts in Dreams|journal=Psychological Science|volume=15|number=4|pages=232–236|url=http://www.wjh.harvard.edu/~wegner/pdfs/Dream%20Rebound.pdf | doi = 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.00657.x <!--Retrieved from CrossRef by DOI bot-->}}</ref> Jung argued that one could consider every person in the dream to represent an aspect of the dreamer, which he called the subjective approach to dreams. ] expanded this point of view to say that even inanimate objects in the dream may represent aspects of the dreamer. The dreamer may therefore be asked to imagine being an object in the dream and to describe it, in order to bring into awareness the characteristics of the object that correspond with the dreamer's personality. | |||

| In both Christianity and Islam dreams feature in conversion stories.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Bulkeley |first=Kelly |url=https://archive.org/details/big-dreams-the-science-of-dreaming-and-the-origins-of-religion |title=Big Dreams: The Science of Dreaming and the Origins of Religion |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=2016 |isbn=9780199351534}}</ref> According to ancient authors, Constantine the Great started his conversion to Christianity because he had a dream which prophesied that he would win the ] if he ]."<ref>Lactantius, ''De Mortibus Persecutorum'' 44.4–6, tr. J.L. Creed, ''Lactantius: De Mortibus Persecutorum'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984), qtd. in Lenski, "Reign of Constantine" (CC), 71.</ref><ref>Eusebius, ''Vita Constantini'' 1.27–29; Barnes, ''Constantine and Eusebius'', 43, 306; Odahl, 105–06, 319–20.</ref> | |||

| ==Other associated phenomena== | |||

| ===Lucid dreaming=== | |||

| {{main|Lucid dreaming}} | |||

| Lucid dreaming is the conscious perception of one's state while dreaming. In this state a person usually has control over characters and the environment of the dream as well as the dreamer's own actions within the dream.<ref> by 1] at Psych Web.</ref> The occurrence of lucid dreaming has been scientifically verified.<ref name=Watanabe2003>{{cite journal | author = Watanabe, T. | year = 2003 | title = Lucid Dreaming: Its Experimental Proof and Psychological Conditions | journal = J Int Soc Life Inf Sci | volume = 21 | issue = 1 | issn = 1341-9226 }}</ref> | |||

| === Buddhist === | |||

| "Oneironaut" is a term sometimes used for those who explore the world of dreams. For example, dream researcher Stephen LaBerge uses the term.<ref>{{cite web | |||

| In Buddhism, ideas about dreams are similar to the classical and folk traditions in South Asia. The same dream is sometimes experienced by multiple people, as in the case of the ], before he is ]. It is described in the '']'' that several of the Buddha's relatives had premonitory dreams preceding this. Some dreams are also seen to transcend time: the Buddha-to-be has certain dreams that are the same as those of ], the '']'' states. In Buddhist literature, dreams often function as a "signpost" motif to mark certain stages in the life of the main character.<ref name="Young 2003">{{cite encyclopedia |last=Young |first=S. |year=2003 |title=Dreams |via=Indian Folklife |volume=13 |url=http://indianfolklore.org/journals/index.php/IFL/article/download/434/497 |encyclopedia=The encyclopedia of South Asian Folklore |page=7 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180225064910/http://indianfolklore.org/journals/index.php/IFL/article/download/434/497 |archive-date=25 February 2018 |access-date=24 February 2018}}</ref> | |||

| | url = http://lucidity.com/DAA/presenters.html | |||

| | title = Dreaming and Awakening 2006 Presenters}}</ref> It is often associated with lucid dreaming in particular. | |||

| Buddhist views about dreams are expressed in the ] and the ].<ref name="Young 2003"/> | |||

| ===Dreams of absent-minded transgression=== | |||

| Dreams of absent-minded transgression (DAMT) are dreams wherein the dreamer absentmindedly performs an action that he or she has been trying to stop (one classic example is of a quitting smoker having dreams of lighting a cigarette). Subjects who have had DAMT have reported waking with intense feelings of ]. One study found a positive association between having these dreams and successfully stopping the behavior.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Hajek P, Belcher M |title=Dream of absent-minded transgression: an empirical study of a cognitive withdrawal symptom |journal=J Abnorm Psychol |volume=100 |issue=4 |pages=487–91 |year=1991 |pmid=1757662| doi = 10.1037/0021-843X.100.4.487 <!--Retrieved from CrossRef by DOI bot-->}}</ref> | |||

| === |

=== Other === | ||

| ] (虎跑夢泉) Statue at Hupao Spring (Hupaomengquan) in Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China]] | |||

| {{main|Dream argument}} | |||

| Dreams can link to actual sensations, such as the incorporation of environmental sounds into dreams such as hearing a phone ringing in a dream while it is ringing in reality, or dreaming of ] while ]. Except in the case of lucid dreaming, people dream without being aware that they are doing so. Some philosophers have concluded that what we think as the "real world" could be or is an illusion (an idea known as the ] about ]). The first recorded mention of the idea was by ], and was also discussed in ]; ] makes extensive use of the argument in its writings.<ref>{{cite book |title=Buddhism As Presented by the Brahmanical Systems |last=Kher |first=Chitrarekha V. |year=1992 |publisher=Sri Satguru Publications |isbn=8170302935 }}</ref> It was formally introduced to western philosophy by ] in the 17th century in his ]. | |||

| In Chinese history, people wrote of two vital aspects of the soul of which one is freed from the body during slumber to journey in a dream realm, while the other remained in the body.<ref name=bulkeley-71/> This belief and dream interpretation had been questioned since early times, such as by the philosopher ] ({{CE|27–97}}).<ref name=bulkeley-71>{{cite book |last=Bulkeley |first=Kelly |title=Dreaming in the world's religions: A comparative history |url=https://archive.org/details/dreamingworldsre00bulk |url-access=limited |year=2008 |isbn=978-0-8147-9956-7 |pages=–73|publisher=NYU Press }}</ref> | |||

| ===Recalling dreams=== | |||

| The Babylonians and Assyrians divided dreams into "good," which were sent by the gods, and "bad," sent by demons.<ref>Oppenheim, L.A. (1966). ''Mantic Dreams in the Ancient Near East'' in G. E. Von Grunebaum & R. Caillois (Eds.), ''The Dream and Human Societies'' (pp. 341–350). London, England: Cambridge University Press.</ref> A surviving collection of dream omens entitled '']'' records various dream scenarios as well as ] of what will happen to the person who experiences each dream, apparently based on previous cases.<ref name="BlackGreen1992"/><ref>Nils P. Heessel : ''Divinatorische Texte I : ... oneiromantische Omina''. Harrassowitz Verlag, 2007.</ref> Some list different possible outcomes, based on occasions in which people experienced similar dreams with different results.<ref name="BlackGreen1992"/> The Greeks shared their beliefs with the Egyptians on how to interpret good and bad dreams, and the idea of incubating dreams. ], the Greek god of dreams, also sent warnings and prophecies to those who slept at shrines and temples. The earliest Greek beliefs about dreams were that their gods physically visited the dreamers, where they entered through a keyhole, exiting the same way after the divine message was given. | |||

| The recall of dreams is extremely unreliable, though it is a skill that can be trained. Dreams can usually be recalled if a person is awakened while dreaming.<ref name="npr" /> Women tend to have more frequent dream recall than men. <ref name="npr"></ref> Dreams that are difficult to recall may be characterized by relatively little ], and factors such as ], ], and interference play a role in dream recall. A ] can be used to assist dream recall, for ] or entertainment purposes. | |||

| ] wrote the first known Greek book on dreams in the 5th century BCE. In that century, other cultures influenced Greeks to develop the belief that souls left the sleeping body.<ref>O'Neil, C.W. (1976). ''Dreams, culture and the individual''. San Francisco: Chandler & Sharp.</ref> The father of modern medicine, ] ({{BCE|460–375}}), thought dreams could analyze illness and predict diseases.<ref>''On Regimen'' IV, also published sometimes as ''On Dreams''.</ref> For instance, a dream of a dim star high in the night sky indicated problems in the head region, while low in the night sky indicated bowel issues.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Hobson |first=J. A. |year=1988 |title=The Dreaming Brain |publisher=Basic Books}}</ref><ref>Steven M. Oberhelman. 1987. “The Diagnostic Dream in Ancient Medical Theory and Practice.” ''Bulletin of the History of Medicine''. 61 (1): 47-60.</ref> ] (129–216 AD) believed the same thing.<ref>Oberhelman, Steven M. 1983. “Galen, ‘On Diagnosis from Dreams’.” ''Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences''. 38 (1): 36-47.</ref> Greek philosopher ] (427–347 BCE) wrote that people harbor secret, repressed desires, such as incest, murder, adultery, and conquest, which build up during the day and run rampant during the night in dreams.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=McCurdy |first=H. G. |year=1946 |title=The history of dream theory |journal=Psychological Review |volume=53 |issue=4 |pages=225–233 |doi=10.1037/h0062107|pmid=20998507 }}</ref> Plato's student, ] (384–322 BCE), believed dreams were caused by processing incomplete ] activity during sleep, such as eyes trying to see while the sleeper's eyelids were closed.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Rycroft |first=Charles |year=1979 |title=The Innocence of Dreams |publisher=Random House}}</ref> ], for his part, believed that all dreams are produced by thoughts and conversations a dreamer had during the preceding days.<ref>Cicero, ''De Republica'', </ref> Cicero's '']'' described a lengthy dream vision, which in turn was commented on by ] in his ''Commentarii in Somnium Scipionis''. | |||

| ===Déjà vu=== | |||

| {{main|Déjà vu}} | |||

| One theory of déjà vu attributes the feeling of having previously seen or experienced something to having dreamt about a similar situation or place, and forgetting about it until one seems to be mysteriously reminded of the situation or place while awake.<ref>{{cite book |title=The Dream Directory: The Comprehensive Guide to Analysis and Interpretation |last=Lohff |first=David C. |year=2004 |publisher=Running Press 0762419628|isbn= }}</ref> | |||

| ] in his '']'', writes "The visions that occur to us in dreams are, more often than not, the things we have been concerned about during the day."<ref>{{cite book |author=Herodotus |title=The Histories |year=1998 |url=https://archive.org/details/histories0000hero |url-access=registration |publisher=Oxford University Press |page=}}</ref> | |||

| ===Dream pre-programming=== | |||

| {{Unreferencedsection|date=June 2008}} | |||

| Dream pre-programming is a hypnotic practice used among some medical and stage hypnotists. It allows the hypnotist to control (or let the patient control) their own dreams. One way that a hypnotist will use this is by telling the person that when they fall asleep that they see a button. And that if they want to enter "DreamScape" that they should press that button. Then they will enter a world just like Earth, but they will have complete control. They will control things with their mind. Dream pre-programming can also help someone for a test or a big event in life. The hypnotist would make the subject dream that event as occurring perfectly, so the subject will get a level of confidence. | |||

| ] is a common term within the ] creation narrative of ] for a personal, or group, ] and for what may be understood as the "timeless time" of formative creation and perpetual creating.<ref> {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090711104046/http://environment.gov.au/parks/uluru/culture-history/culture/index.html |date=11 July 2009}} environment.gov.au, June 23, 2006</ref> | |||

| ===Dream incorporation=== | |||

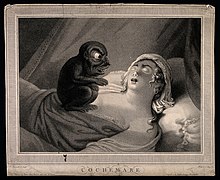

| In one use of the term, "dream incorporation" is a phenomenon whereby an external stimulus, usually an auditory one, becomes a part of a dream, eventually then awakening the dreamer. There is a famous painting by ] that depicts this concept, titled "]" (1944). | |||

| Some ] tribes and ] populations believe that dreams are a way of visiting and having contact with their ]s.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Tedlock |first1=B. |year=1981 |title=Quiche Maya dream Interpretation |journal=Ethos |volume=9 |issue=4 |pages=313–350 |doi=10.1525/eth.1981.9.4.02a00050 |doi-access=free}}</ref> Some ] tribes have used ]s as a rite of passage, fasting and praying until an anticipated guiding dream was received, to be shared with the rest of the tribe upon their return.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.dreams.ca/dreams.htm |last=Webb |first=Craig |year=1995 |title=Dreams: Practical Meaning & Applications |publisher=The DREAMS Foundation |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160305002601/http://www.dreams.ca/dreams.htm |archive-date=5 March 2016 |access-date=30 March 2008}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://dreamhawk.com/dream-encyclopedia/native-american-dream-beliefs/ |access-date=10 April 2012 |title=Native American Dream Beliefs |publisher=Dream Encyclopedia |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120415132211/http://dreamhawk.com/dream-encyclopedia/native-american-dream-beliefs/ |archive-date=15 April 2012}}</ref> | |||

| The term "dream incorporation" is also used in research examining the degree to which preceding daytime events become elements of dreams. Recent studies suggest that events in the day immediately preceding, and those about a week before, have the most influence .<ref name="day-residue">{{cite web |url=http://www.asdreams.org/2003/abstracts/genevieve_alain.htm |title=Replication of the Day-residue and Dream-lag Effect |last=Alain, M.Ps. |first=Geneviève |coauthors=Tore A. Nielsen, Ph.D., Russell Powell, Ph.D., Don Kuiken, Ph.D. |date=July 2003 |work=20th Annual International Conference of the | |||

| Association for the Study of Dreams }}</ref> | |||

| == Interpretation == | |||

| {{Main|Dream interpretation}} | |||

| {{Further|Psychoanalysis|Precognition}} | |||

| ] (1836–1902).]] | |||

| Beginning in the late 19th century, Austrian neurologist ], founder of ], theorized that dreams reflect the dreamer's ] and specifically that dream content is shaped by unconscious wish fulfillment. He argued that important unconscious desires often relate to early childhood memories and experiences.<ref name="Freud1"/> ] and others expanded on Freud's idea that dream content reflects the dreamer's unconscious desires. | |||

| {{anchor|Veridical dream}}<!-- Target for ] --> | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| Dream interpretation can be a result of subjective ideas and experiences. One study found that most people believe that "their dreams reveal meaningful hidden truths".<ref name=":0">{{Cite journal |title=When dreaming is believing: The (motivated) interpretation of dreams. |journal=Journal of Personality and Social Psychology |pages=249–264 |volume=96 |issue=2 |doi=10.1037/a0013264 |first1=Carey K. |last1=Morewedge |first2=Michael I. |last2=Norton |s2cid=5706448 |pmid=19159131 |year=2009 |url=http://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/4f27/7783ada0dca0d236f368600f166fc7055524.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201114093642/http://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/4f27/7783ada0dca0d236f368600f166fc7055524.pdf |url-status=dead |archive-date=14 November 2020}}</ref> The researchers surveyed students in the United States, South Korea, and India, and found that 74% of Indians, 65% of South Koreans and 56% of Americans believed their dream content provided them with meaningful insight into their unconscious beliefs and desires. This Freudian view of dreaming was believed significantly more than theories of dreaming that attribute dream content to memory consolidation, problem-solving, or as a byproduct of unrelated brain activity. The same study found that people attribute more importance to dream content than to similar thought content that occurs while they are awake. Americans were more likely to report that they would intentionally miss their flight if they dreamt of their plane crashing than if they thought of their plane crashing the night before flying (while awake), and that they would be as likely to miss their flight if they dreamt of their plane crashing the night before their flight as if there was an actual plane crash on the route they intended to take. Participants in the study were more likely to perceive dreams to be meaningful when the content of dreams was in accordance with their beliefs and desires while awake. They were more likely to view a positive dream about a friend to be meaningful than a positive dream about someone they disliked, for example, and were more likely to view a negative dream about a person they disliked as meaningful than a negative dream about a person they liked. | |||

| {{commonscat}} | |||

| *] | |||

| According to surveys, it is common for people to feel their dreams are predicting subsequent life events.<ref name="hines"/> Psychologists have explained these experiences in terms of ], namely a selective memory for accurate predictions and distorted memory so that dreams are retrospectively fitted onto life experiences.<ref name="hines">{{cite book |last=Hines |first=Terence |title=Pseudoscience and the Paranormal |publisher=Prometheus Books |year=2003 |pages=78–81 |isbn=978-1-57392-979-0}}</ref> The multi-faceted nature of dreams makes it easy to find connections between dream content and real events.<ref>{{cite book |last=Gilovich |first=Thomas |title=How We Know What Isn't So: the fallibility of human reason in everyday life |publisher=Simon & Schuster |year=1991 |pages=177–180 |isbn=978-0-02-911706-4}}</ref> The term "veridical dream" has been used to indicate dreams that reveal or contain truths not yet known to the dreamer, whether future events or secrets.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.llewellyn.com/encyclopedia/term/Veridical+Dream |title=Llewellyn Worldwide – Encyclopedia: Term: Veridical Dream |website=www.llewellyn.com |access-date=16 October 2016 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161018202429/http://www.llewellyn.com/encyclopedia/term/Veridical+Dream |archive-date=18 October 2016}}</ref> | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||