| Revision as of 18:53, 9 January 2018 view source70.51.241.127 (talk) →Preparation← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 00:39, 12 January 2025 view source Grumpylawnchair (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers5,952 edits cleaned up "Former Yugoslavia" sectionTag: Visual edit | ||

| (607 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Coffee brewing method without filters}} | |||

| {{original research|date=October 2017}} | |||

| {{pp|small=yes}} | |||

| {{use dmy dates|date=July 2024}} | |||

| {{Infobox beverage | {{Infobox beverage | ||

| | name = Turkish coffee | | name = Turkish coffee | ||

| | image = File:Türk Kahvesi - Bakir Cezve.jpg | | image = File:Türk Kahvesi - Bakir Cezve.jpg | ||

| | caption = A cup of Turkish coffee, served from a copper ] |

| caption = A cup of Turkish coffee, served from a copper ] | ||

| | type = ] | | type = ] | ||

| | origin = |

| origin = Disputed | ||

| | region = |

| region = | ||

| | color = ] | | color = ] | ||

| }} |

}} | ||

| '''Turkish coffee''' ({{lang-tr|Türk kahvesi}}) is a method of preparing unfiltered ].<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.ricksteves.com/watch-read-listen/read/articles/getting-your-buzz-with-turkish-coffee|title=Getting Your Buzz with Turkish coffee|work=ricksteves.com|accessdate=19 August 2015}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.bbc.com/travel/story/20140707-the-complicated-culture-of-bosnian-coffee|title=BBC - Travel - The complicated culture of Bosnian coffee|author=Brad Cohen|work=bbc.com|accessdate=19 August 2015}}</ref> | |||

| '''Turkish coffee''' is a style of ] prepared in a '']'' using very finely ground ]s without filtering.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.ricksteves.com/watch-read-listen/read/articles/getting-your-buzz-with-turkish-coffee |title=Getting Your Buzz with Turkish coffee |publisher=ricksteves.com |access-date=19 August 2015}}</ref><ref name="Cohen_2014"/> | |||

| ==Preparation== | ==Preparation== | ||

| Turkish coffee is very finely ground coffee brewed by boiling. Any coffee bean may be used; ] varieties are considered best, but ] or a blend is also used.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://resources.urnex.com/blog/making-turkish-coffee-with-a-turkish-barista-champion |title=Making Turkish Coffee with a Turkish Barista Champion |quote=Some supermarkets sell coffee that is pre-ground, marketed as Turkish coffee, and usually robusta. |website=Resources.urnex.com |date=22 November 2017 |author-first=Nisan |author-last=Agca |access-date=5 May 2018}}</ref> The coffee grounds are left in the coffee when served.<ref name="Dugan"/><ref name="Basan"/> The coffee may be ground at home in a ] made for the very fine grind, ground to order by coffee merchants in most parts of the world, or bought ready-ground from many shops. | |||

| Turkish coffee was invented by the Greeks, the proper term is "Greek coffee." Greek coffee is made by boiling the ground coffee beans (and is not made, for example, by ] or ]). Its preparation is done by a method that has two characteristic features. First, if sugar is to be added to the coffee, it is done at the start of the boiling, not after. Second, the boiling is done as slowly as possible, without letting the water get to a state beyond that of ]. When the grounds begin to froth, about one-third of the coffee is distributed to the various individual cups, after which the remaining two-thirds is returned to the fire. After the coffee froths a second time, the process is completed and the remaining coffee is distributed to the individual cups.<ref>{{cite book| author-last= Basan |author-first=Ghillie |title=The Middle Eastern Kitchen |publisher= Hippocrene Books |location=New York |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-7wnpIi3VRwC&pg=PA37&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwihv5O91JXVAhUJVD4KHag9BPwQ6AEIQzAG#v=onepage&f=false | page=37 |isbn=978-0-7818-1190-3}}</ref> | |||

| ] era ''Kahve fincanı'']] | |||

| Coffee and water, usually with added ], is brought to the boil in a special pot called '']'' in Turkey, and often called '']'' elsewhere. As soon as the mixture begins to froth, and before it boils over, it is taken off the heat; it may be briefly reheated twice more to increase the desired froth. Sometimes about one-third of the coffee is distributed to individual cups; the remaining amount is returned to the fire and distributed to the cups as soon as it comes to the boil.<ref name="Engin"/><ref name="Basan">{{cite book |author-last=Basan |author-first=Ghillie |title=The Middle Eastern Kitchen |date=2006 |publisher=Hippocrene Books |location=New York, USA |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-7wnpIi3VRwC&pg=PA37 |page=37 |isbn=978-0-7818-1190-3}}</ref> The coffee is traditionally served in a small ] cup called a ''{{lang|tr|kahve fincanı}}'' 'coffee cup'.<ref name="Engin">{{cite book |publisher=Abrams |isbn=978-1-61312-871-8 |author-last=Akin |author-first=Engin |title=Essential Turkish Cuisine |date=2015-10-06}}</ref> | |||

| Another ancient tradition involves placing the cezve filled with coffee in a pan filled with hot sand. The pan is heated over an open flame, thereby letting the sand take total control of the heat. The heat created by the sand lets the coffee foam to the top almost immediately. The heat can also be adjusted by the depth of the cezve in the sand. This process is usually repeated three to four times and then the coffee is finally served in small cups called demitasse cups.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://deathwishcoffee.com/blogs/coffee-talk/turkish-sand-coffee |title=Turkish Sand Coffee: Preparation and History |date= December 2022}}</ref> | |||

| The amount of sugar is specified when ordering the coffee. It may be unsweetened ({{langx|tr|sade kahve}}), with little or moderate sugar ({{langx|tr|az şekerli kahve}}, {{Lang|tr|orta şekerli kahve}} or {{lang|tr|orta kahve}}), or sweet ({{langx|tr|çok şekerli kahve}}). Coffee is often served with something small and sweet to eat, such as ].<ref>{{cite book |publisher=Fodor's Travel Publications |isbn=978-0-307-92843-6 |author-last1=Hattam |author-first1=Jennifer |author-last2=Larson |author-first2=Vanessa |author-last3=Newman |author-first3=Scott |title=Turkey |date=2012 |url-access=registration |url=https://archive.org/details/isbn_9780307928436}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |author-last=Basan |author-first=Ghillie |title=Classic Turkish Cookery |date=1997 |publisher=I.B. Tauris |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Xb62ZJMNVBwC&pg=PA218 |page=218 |isbn=1-86064011-7}}</ref> It is sometimes flavoured with ],<ref name="Dugan">{{cite book |publisher=Ten Speed Press |isbn=978-1-60774-118-3 |author-last1=Freeman |author-first1=James |author-last2=Freeman |author-first2=Caitlin |author-last3=Duggan |author-first3=Tara |title=The Blue Bottle Craft of Coffee: Growing, Roasting, and Drinking, With Recipes |date=2012-10-09}}</ref> ], ],<ref>{{cite web |url=https://londonist.com/london/food-and-drink/coffee-international-around-the-world-london |title=Where To Drink Coffees From Around The World In London |website=Londonist |author-first=Sejal |author-last=Sukhadwala |date=11 October 2016 |access-date=26 October 2018}}</ref> or ].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.theguideistanbul.com/istanbul-historic-coffeehouses/ |title=The starting point of Turkish coffee: Istanbul's historic coffeehouses |website=The Istanbul Guide |date=6 August 2018 |access-date= 26 October 2018}}</ref> | |||

| A lot of the powdered coffee grounds are transferred from the {{Lang|tr|cezve}} to the cup; in the cup, some settle on the bottom but much remains in ] and is consumed with the coffee. | |||

| ===According to connoisseurs=== | |||

| In a paper for the 2013 Oxford Food Symposium, Tan and Bursa identified the features of the art or craft of making and serving Turkish coffee, according to the traditional procedures: | |||

| * Roasting. Ideally the best green Arabica beans are medium-roasted in small quantities over steady heat in a shallow, wrought-iron roasting pan. It is crucial to stop at the right moment, then transfer the beans to the next stage: | |||

| * Cooling. The beans are allowed to cool down in a wooden box and absorb excess oil. The kind of wood is claimed to affect the taste, walnut being the best. | |||

| * Pounding or grinding. The beans must be reduced into a very fine powder. The fineness of the powder is crucial to the success of Turkish coffee since it affects the foam and mouth feel. (According to one source,<ref name="Yilmaz"/>{{rp|218}} the particle size should be 75–125 microns.) Strict connoisseurs insist that they must be hand-pounded in a wooden mortar, although it is difficult to do this while achieving a uniform fineness. Consequently, it has become more usual to grind them in a brass or copper mill, though it does make for drier particles. | |||

| * Brewing. It is essential to use a proper ''cezve''. This vessel is a conical flask, being wider at the base than at the neck, and is made of thick forged copper. (A common sized ''cezve'' will make one cup of coffee, and they can easily be ordered online in many western countries.) Cold water, several teaspoons of the ground coffee (at least 7 grams per person)<ref name="Yilmaz"/>{{rp|219}} and any sugar are put in the ''cezve'' and it is put on the fire. The tapering shape of the vessel encourages the formation of foam and retains the volatile aromas. The coffee should never be allowed to come to a rolling boil, and must not be over-done. "This stage requires close monitoring and delicate timing since a good Turkish coffee has the thickest possible layer of froth at the top". Some think that the metallic copper helps to improve the taste. | |||

| * Serving. The ''cezve'' has a spout by which it is poured into the serving cup. While the cup design might not seem to have anything to do with the taste of the beverage, connoisseurs say it makes a difference. The best cups are made of porcelain with a thin rim: it affects mouth feel. A long cultural tradition emphasises the pleasure of being served coffee in beautiful cups, which are family heirlooms. The beverage is served together with a glass of water which should be sipped first to cleanse the mouth. Other cultural traditions affect the guest's appreciation of the beverage and the conviviality of the occasion, including story-telling, fortune-telling, and so forth. | |||

| While some of these stages may be curtailed in modern coffee drinking, for example the coffee might be purchased already roasted and ground, the rituals and paraphernalia (e.g. the anticipatory smell of the roasting beans) do act on the imagination and have a psychological effect.<ref name="Tan"/> | |||

| ==History== | |||

| {{Further|Ottoman coffeehouse}} | |||

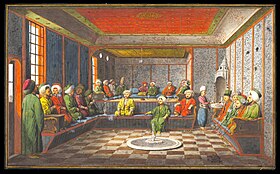

| ])]] | |||

| Coffee drinking spread in the Islamic world in the 16th century.<ref name="Faroqhi">{{cite journal |author-last=Faroqhi |date=1986 |author-first=Suraiya |title=Coffee and Spices: Official Ottoman Reactions to Egyptian Trade in the Later Sixteenth Century |journal=Wiener Zeitschrift für die Kunde des Morgenlandes |volume=76: Festschrift Andreas Tietze zum 70. Geburtstag gewidmet von seinen Freunden und Schülern |pages=87–93 |jstor=23868774}}</ref>{{rp|88}} From the ] it arrived in Cairo;<ref name="Quickel">{{cite book |chapter=Cairo and Coffee in the Transottoman Trade Network |author-first=Anthony T. |author-last=Quickel |title=Transottoman Matters |date=2022 |pages=83–98 |publisher=V&R unipress / Brill Deutschland GmbH |isbn=978-3-84711168-9 <!-- |eisbn=978-3-73701168-6 --> |doi=10.14220/9783737011686.83}}</ref><ref name="Ayvazoğlu">{{cite book |author-last=Ayvazoğlu |author-first=Beşir |date=2011 |title=Turkish Coffee Culture |translator-last=Şeyhun |translator-first=Melis |publisher=Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism |location=Ankara, Turkey |isbn=978-975-17-3567-6 |url=https://teda.ktb.gov.tr/Eklenti/6594,turkishcoffeeculturepdf.pdf |access-date=14 February 2024}}</ref>{{rp|14}} from thence it went to Syria and Istanbul.<ref name="Hathaway">{{cite journal |author-last=Hathaway |author-first=Jane |date=2006 |title=The Ottomans and the Yemeni Coffee Trade |journal=Oriente Moderno, Nuova Serie |publisher=] |volume=Anno 25 (86) |number=1: The Ottomans and Trade |pages=161–171 |jstor=25818052}}</ref>{{rp|14}} The coffee tree was first cultivated commercially in the ], having been introduced there from the rainforests of Ethiopia<ref group="nb" name="NB_Robusta"/> where it grew wild.<ref name="Herrera">{{cite book |chapter=The Coffee Tree - Genetic Diversity and Origin |title=The Craft and Science of Coffee |author-last1=Herrera |author-first1=Juan Carlos |author-last2=Lambot |author-first2=Charles |editor-last=Folmer |editor-first=Britta |publisher=] |date=2017 |isbn=978-0-12-803520-7 |pages=1, 2 |chapter-url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/312184186 |access-date=2024-02-15 |url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/312184186 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240705191650/https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Adriana_Farah2/publication/312184186_Human_Wellbeing-Sociability_Performance_and_Health/links/5f90dba3458515b7cf937346/Human-Wellbeing-Sociability-Performance-and-Health.pdf?__cf_chl_rt_tk=a3hK2ONy9aESJh53rAdhFH2Zsfg83.MulWdVIhH5VxY-1720207010-0.0.1.1-4478 |archive-date=2024-07-05}}</ref> For a long time<ref name="Topik"/>{{rp|85}} Yemenis had a world monopoly on the export of coffee beans<ref name="Herrera"/> (according to ], by deliberately destroying their ability to germinate).<ref name="Friis">{{cite journal |author-last=Friis |author-first=Ib |author-link=Ib Friis |date=2015 |title=Coffee and qat on the Royal Danish expedition to Arabia – botanical, ethnobotanical and commercial observations made in Yemen 1762–1763 |journal=Archives of Natural History |volume=42 |issue=1 |pages=101–112 |doi=10.3366/anh.2015.0283}}</ref>{{rp|102}} For nearly a century (1538–1636) the Ottoman Empire controlled the southern coastal region of the Yemen, notably its famous coffee port ].<ref name="Hathaway"/>{{rp|163}} In the 18th century Egypt was the richest province of the Ottoman Empire, and the chief commodity it traded was Yemeni coffee.<ref name="Ginio">{{cite journal |author-last=Ginio |date=2006 |author-first=Eyal |title=When Coffee Brought about Wealth and Prestige: The Impact of Egyptian Trade on Salonica |journal=Oriente Moderno, Nuova Serie |publisher=] |volume=Anno 25 (86) |number=1: The Ottomans and Trade |pages=93–107 |jstor=25818048}}</ref> Cairo merchants were responsible for moving it from the Yemen to markets in the Islamic world.<ref name="Quickel"/>{{rp|92–94}} | |||

| Coffee was in use in Istanbul by 1539, for a legal document mentions Ottoman admiral ]'s house had a coffee chamber.<ref name="Kafadar"/>{{rp|247}} It appears that the first coffeehouse in Istanbul was opened in 1554 (some say 1551)<ref name="Kafadar"/>{{rp|249}}<ref name="Quickel"/>{{rp|87}} by Hakem of Aleppo and Șems of Damascus (they may have been separate establishments at first).<ref name="Ayvazoğlu"/>{{rp|23}} Soon, coffeehouses spread all over Istanbul and even to small towns in ].<ref name="Karababa">{{cite journal |author-last1=Karababa |author-last2=Ger |date=2011 |author-first1=Emİnegül |author-first2=Gülİz |title=Early Modern Ottoman Coffeehouse Culture and the Formation of the Consumer Subject |journal=Journal of Consumer Research |volume=37 |issue=5 |pages=737–760 |publisher=] |doi=10.1086/656422 |jstor=10.1086/656422 |hdl=11511/34922 |hdl-access=free}}</ref>{{rp|744}} | |||

| ] described for French readers the Turkish method of brewing coffee ({{Lang|fr|Tableau Général de l'Empire Othoman}}, 1789). His description, translated in this note,<ref>{{cite book |author-last=d'Ohsson |author-first=Ignatius Mouradgea |title=Tableau Général de l'Empire Othoman |date=1788 |publisher=L'Imprimerie de Monsieur |location=Paris, France |author-link=Ignatius Mouradgea d'Ohsson |language=fr |url=https://archive.org/details/tableaugnral04mour/page/n7/mode/2up |access-date=17 February 2024 |pages=84–85 |quote-page= |trans-quote="Its preparation is very simple. After roasting the grain, it is pounded and reduced to a very fine powder in a wood, marble or bronze mortar. Five or six small spoonfuls of it are put in a tinned copper coffee pot, when the water is boiling, and care is taken to remove the pot from the heat every time the foam rises, until absorbed by water it presents with it a smooth surface". Roasted, ground coffee was stored in airtight leather bags or boxes, for "The fresher it is, the more pleasant it is; so in large houses we take care to roast it every day."}}</ref> closely resembles the present day version, including the production of foam. From the traveller ] it appears Turks were using it at least a century before that. He mentions that they drank it black; some added cloves, cardamom or sugar, but it was thought to be less healthy,<ref>{{cite book |author-last=Thévenot |author-first=Jean de |date=1687 |title=Travels into the Levant |publisher=Fairthorne |location=London, UK |author-link=Jean de Thévenot |url=https://archive.org/details/b30325870/page/n82/mode/1up?view=theater |access-date=18 February 2024 |page=33}}</ref> and until recently, an older generation of connoisseurs disdained the habit of sugaring Turkish coffee.<ref name="Ayvazoğlu"/>{{rp|5}} | |||

| ===Origin of the Turkish method=== | |||

| ] | |||

| There are inconsistent claims as to the origin of Turkish coffee. Without citing historical sources, some authors have asserted the method originated in the Yemen.<ref name="Kakissis2"/><ref>{{cite book |doi=10.1016/B978-0-12-815270-6.00015-3 |chapter=Functional and Traditional Nonalcoholic Beverages in Turkey |title=Non-Alcoholic Beverages |date=2019 |author-last1=Tamer |author-first1=Canan Ece |author-last2=Yolci Ömeroğlu |author-first2=Perihan |author-last3=Çopur |author-first3=Ömer Utku |pages=483–521 |isbn=978-0-12-815270-6}}</ref><ref name=":02unesco">{{cite web |website=UNESCO |title=Turkish coffee, not just a drink but a culture |url=https://courier.unesco.org/en/articles/turkish-coffee-not-just-drink-culture |access-date=9 April 2024}}</ref> or in Damascus (a plausible, if unsubstantiated claim, since the Middle Eastern coffeehouse did probably originate in Damascus<ref>{{cite book |doi=10.1163/ej.9789004171022.i-536 |pages=29–30 |title=Letters of a Sufi Scholar |date=2010 |author-last=Akkach |author-first=Samer |isbn=978-90-474-2433-8}}</ref> and was brought to Istanbul by Syrians, see above); or with the Turkish people themselves.<ref name="Yilmaz">{{cite journal |author-last1=Yılmaz |author-first1=Birsen |author-last2=Acar-Tek |author-first2=Nilüfer |author-last3=Sözlü |author-first3=Saniye |date=2017 |title=Turkish cultural heritage: a cup of coffee |journal=Journal of Ethnic Foods |volume=4 |issue=4 |doi=10.1016/j.jef.2017.11.003 |doi-access=free |pages=213–220 }}</ref> | |||

| Yemenis may have been the first to consume coffee as a hot beverage (instead of chewing the bean, or adding it to solid food)<ref name="Topik"/>{{rp|88}} and the earliest social users were probably ] mystics in that region who needed to stay awake for their nocturnal vigils.<ref name="Kafadar">{{cite book |author-last=Kafadar |author-first=Cemal |date=2014 |chapter=How dark is the history of the night, how black the story of coffee, how bitter the tale of love: The changing measure of leisure and pleasure in early modern Istanbul |title=Medieval and Early Modern Performance in the Eastern Mediterranean |editor-last1=Öztürkmen |editor-first1=Arzu |editor-last2=Vitz |editor-first2=Evelyn Burge |pages=243–269}}</ref>{{rp|246}} However a 1762 Danish scientific expedition noted that Yemenis did not like coffee made the "Turkish" way, and rarely drank it, thinking it bad for the health: they much preferred ''kisher'', a beverage made of the coffee shells which more closely resembled a tea;<ref name="Friis"/>{{rp|105}} Likewise, according to scientist ] (1774), French visitors to the Yemeni royal court noticed that only a version was drunk made from coffee husks with a colour like beer.<ref name="Ellis"/>{{rp|20}} In 1910, the U.S. consul at Aden reported {{blockquote|the Yemen Arab never uses coffee himself, contrary to general opinion and the reports of some travelers, but raises it almost wholly for export. He uses kishar, a beverage he brews from the dried hulls, in large quantities... So little is coffee used by the people that a few months after the new crop has been gathered it is impossible for one passing through the country to buy a single pound<ref name="Moser">{{cite book |author-last=Moser |author-first=Charles K. |date=1910 |chapter=Production of Mocha Coffee |title=Daily Consular and Trade Reports |publisher=Department of Commerce and Labor |location=Washington DC, USA |pages=954–956 |url=https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=chi.095773664&seq=992 |access-date=26 April 2024}}</ref>}} and it has been said that Yemenis do not drink much coffee to this day.<ref name="Topik">{{cite journal |author-last=Topik |author-first=Steven |date=2009 |title=Coffee as a Social Drug |journal=Cultural Critique |volume=71: Drugs in Motion: Mind- and Body-Altering Substances in the World's Cultural Economy |issue=71 |pages=81–106 |doi=10.1353/cul.0.0027 |jstor=25475502}}</ref>{{rp|88}} | |||

| If Turkish coffee is defined as "a very strong black coffee served with the fine grounds in it", then the method is generic in Middle Eastern cities (in rural areas a different method is used and is called Arabic coffee)<ref name="Basan"/>{{rp|37}} and goes by various other names too, such as Egyptian coffee, Syrian coffee, and so forth,<ref>{{cite journal |author-last=Abraham-Barna |author-first=Corina Georgeta |date=2013 |title=The term of Turkish coffee – a semasiological approach |journal=Journal of Agroalimentary Processes and Technologies |volume=19 |issue=2 |pages=271–275 |url=https://journal-of-agroalimentary.ro/admin/articole/65041L44_Vol_19_2__2013_271-275.pdf |access-date=1 March 2024}}</ref> though there may be some local variations. | |||

| ===Illegality and acceptance=== | |||

| ] | |||

| The English word ''coffee'' derives from Turkish {{Lang|tr|kahve}}, which came from Arabic {{Lang|ar-latn|qahwah}},<ref>Oxford English Dictionary Online, ''Coffee'', noun, etymology, accessed 4 April 2024.</ref> which could mean {{Gloss|wine}}.<ref name="Hattox">{{cite book |author-last=Hattox |author-first=Ralph S. |date=1988 |title=Coffee and Coffeehouses: The Origins of a Social Beverage in the Medieval Near East |publisher=University of Washington Press |location=Seattle, USA and London, UK |isbn=0-295-96231-3}}</ref>{{rp|18}} It is sometimes stated that coffee was forbidden in Islam, albeit the ban was not very effective.<ref name="Hattox"/>{{rp|3–6}}<ref name="Karababa"/>{{rp|747}} However, it seems most Muslim religious scholars actually supported coffee, or were not averse to it on principle.<ref name="Vahedi">{{cite journal |author-last=Vahedi |date=2021 |author-first=Massoud |title=Coffee was once Ḥarām? Dispelling Popular Myths regarding a Nuanced Legal Issue |journal=Islamic Studies |volume=60 |issue=2 |pages=125–156 |doi=10.52541/isiri.v60i2.1459 |jstor=27088432}}</ref> It was governments who wanted to suppress coffee gatherings, fearing they were foci of political dissent.<ref name="Kafadar"/>{{rp|252}} "What was condemned was not caffeine's physiological effects but rather the freedom of coffeehouse talk which rulers considered subversive".<ref name="Topik"/>{{rp|84}} | |||

| Already in 1543 several ships were ordered to be sunk in Istanbul harbour for importing coffee.<ref name="Avazoglu">{{cite book |author-last=Ayvazoğlu |author-first=Beşir |date=2011 |title=Turkish Coffee Culture |translator-last=Şeyhun |translator-first=Melis |publisher=Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism |location=Ankara, Turkey |isbn=978-975-17-3567-6 |url=https://teda.ktb.gov.tr/Eklenti/6594,turkishcoffeeculturepdf.pdf |access-date=14 February 2024}}</ref>{{rp|90}} Under Sultan ] those found keeping a coffeehouse were ]led for a first offence, sewn in a bag and thrown into the ] for a second.<ref name="Topik"/>{{rp|90}} These bans were sporadic and often ignored. (Similarly, the government of ] tried to suppress coffee houses as seditious gatherings - the ban lasted a few days<ref name="Ellis">{{cite book |author-last=Ellis |author-first=John |date=1774 |title=A Historical Account of Coffee |publisher=Edward and Charles Dilly |location=London, UK |url=https://archive.org/details/bim_eighteenth-century_an-historical-account-of_ellis-john_1774 |access-date=10 April 2024}}</ref>{{rp|14}} - and, much later, the republican government of ] tried to prohibit or discourage coffeehouses in Turkish villages, saying they were places where men gathered to waste their time).<ref name="Öztürk">{{cite journal |author-last=Öztürk |author-first=Sedar |date=2008 |title=The Struggle over Turkish Village Coffeehouses (1923–45) |journal=Middle Eastern Studies |volume=44 |issue=3 |pages=435–454 |doi=10.1080/00263200802021590 |jstor=40262586}}</ref>{{rp|434–454}} Eventually the authorities found it to their advantage to tax the trade not suppress it.<ref name="Faroqhi"/>{{rp|93}} Fifteen years after coffee arrived in Istanbul there were over 600 coffeehouses, wrote an Armenian historian.<ref name="Ervin"/>{{rp|10}} | |||

| To prepare Turkish coffee very well is not easy,<ref name="Tan">{{cite book |author-last1=Tan |author-last2=Bursa |date=2014 |author-first1=Aylin Öney |author-first2=Nihal |chapter=Turkish Coffee: ''arte'' & ''factum'', Paraphernalia of a Ritual from Ember to Cup |pages=314–324 |editor-last=McWilliams |editor-first=Mark |title=Food & Material Culture: Proceedings of the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookey 2013 |publisher=Prospect Books |isbn=978-1-909248-40-3 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=yj8QDgAAQBAJ&dq=turkish+coffee+microns&pg=PA314 |access-date=1 April 2024}}</ref>{{rp|317}}<ref name="Ervin">{{cite journal |author-last=Ervin |author-first=Marita |date=2014 |title=Coffee and the Ottoman Social Sphere |journal=University of Puget Sound Collins Memorial Library |pages=3–41 |jstor=36514034}}</ref>{{rp|14–15}} and prominent Ottoman Turks kept specialist coffee cooks for the purpose. ] had a {{Lang|ota-latn|kahvecibasi}} or chief coffee-cook, and it became a traditional practice for sultans. To demonstrate the civility of their rule, they built magnificent coffeehouses in newly conquered parts of the Ottoman Empire.<ref name="Ervin"/>{{rp|13}} | |||

| ===International diffusion=== | |||

| ====Western Europe==== | |||

| ] | |||

| From the Ottoman Empire, coffee-drinking spread to western Europe, probably being first introduced into Venice, where it was consumed as a medicine.<ref name="Ukers"/>{{rp|25, 27}} Early consumers were travellers who imported it for their own use.<ref name="Montagné">{{cite book |author-last=Montagné |author-first=Prosper |date=1961 |title=Larousse Gastronomique |publisher=Hamlyn |location=London, UK and New York, USA |isbn=0-600-02352-4}}</ref>{{rp|286}}<ref name="Landweber">{{cite journal |author-last=Landweber |author-first=Julia |date=2015 |title="This Marvelous Bean": Adopting Coffee into Old Regime French Culture and Diet |journal=French Historical Studies |volume=38 |issue=2 |pages=193–223 |doi=10.1215/00161071-2842542}}</ref>{{rp|200}} Other early users were ''virtuosi'': gentleman-scholars curious about the outside world and willing to try exotic products.<ref name="Cowan">{{cite book |author-last=Cowan |author-first=Brian William |date=2005 |title=The Social Life of Coffee: the Emergence of the British Coffeehouse |publisher=Yale University Press |isbn=0-300-10666-1}}</ref>{{rp|10–15}} Since these early adopters were trying to recreate the genuine article, probably they were making proper Turkish coffee, or at least something like it. For example, Jean de Thévenot imported authentic ''ibriks'' from the Ottoman Empire.<ref name="Landweber"/>{{rp|209}} | |||

| However, most early modern Europeans did not like coffee,<ref name="Landweber"/>{{rp|194, 200}}<ref name="Ervin"/>{{rp|4}} which is an acquired taste,<ref name="Cowan"/>{{rp|5–6}} and especially they did not like the black, bitter Turkish version.<ref name="Landweber"/>{{rp|201}} In any case it was too expensive: in France, coffee beans sold for the equivalent of $8,000 a kilo.<ref name="Landweber"/>{{rp|215}} Coffee did not become a popular beverage until it was altered to appeal to European palates and its price drastically lowered, as follows. | |||

| The Yemeni coffee monopoly was broken by the Dutch, who managed to obtain viable coffee plants from Mocha and propagated them to their empire in Java.<ref name="Landweber"/>{{rp|213}}<ref name="Cowan"/>{{rp|76}} They were followed by the French, who planted a tree at the ]; it has been claimed that "This tree was destined to be the progenitor of most of the coffee of the French colonies, as well as those of South America, Central America, and Mexico",<ref name="Ukers">{{cite book |author-last=Ukers |author-first=William H. |author-link=:d:Q28854736 |date=1922 |title=All About Coffee |publisher=The Tea and Coffee Trade Journal Company |location=New York, USA |url=https://archive.org/details/allaboutcoffee00ukeruoft/page/n10/mode/1up |access-date=3 April 2024}}</ref>{{rp|5–9}}<ref name="Montagné"/>{{rp|286}} i.e. most of the coffee in the world, though it has been called "a neat story".<ref name="Topik2004">{{cite conference |author-last=Topik |author-first=Steven |date=2004 |title=The World Coffee Market in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries, from Colonial to National Regimes |conference=First GEHN Conference, Bankside, London |pages=1–31 |publisher=] |url=https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/22489/1/wp04.pdf |access-date=22 April 2024}}</ref>{{rp|2}} By the time of the French Revolution, 80% of the world's coffee was grown in the Americas and French coffee was ousting the Yemeni product in Cairo,<ref name="Topik2004"/>{{rp|12}} even being exported back to Mocha itself. The price of coffee fell so much that by mid-18th century it was accessible to French townspeople of all classes.<ref name="Landweber"/>{{rp|214, 223}} | |||

| ], Paris, 1694: the Princesse de Bournonville takes coffee in 'Turkish' attire (Nicolas Bonnart: Bibliothéque Nationale de France)]] | |||

| When coffee was eventually popularised, what was served was not genuine Turkish coffee, but a product heavily diluted with water (much weaker than modern espresso)<ref name="Cowan"/>{{rp|80}} or milk,<ref name="Landweber"/>{{rp|212}} and sweetened with sugar.<ref name="Cowan"/>{{rp|80}}<ref name="Landweber"/>{{rp|196}} "Combining coffee with fresh milk turned a Turkish drink into a French one".<ref name="Landweber"/>{{rp|204}} Already in 1689, in a paper for fellow scientists at the ], London, ] though stressing coffee's Ottoman origins, said very good coffee was made by boiling the grounds in plenty of water and letting them settle, leaving a clear, reddish liquor:<ref>{{cite journal |author-last=Houghton |author-first=John |author-link=John Houghton (apothecary) |date=1699 |title=A discourse of coffee, read at a meeting of the Royal Society, by Mr. John Houghton, F. R. S. |journal=] |volume=21 |issue=256 |pages=311–317 |doi=10.1098/rstl.1699.0056 |quote-page=314 |quote="If an Ounce be ground, and boil'd in something more than a quart of Water, till it be fully impregnated by the fine Particles of the Coffee, and the rest is grown so ponderous, as it will subside and leave the Liquor clear, and of a reddish Colour, it will make about a Quart of very good Coffee."}} (NB. That would be 28 g of ground coffee in a litre of water.)</ref> which is not Turkish coffee. | |||

| Despite this, the "Turkish" connection was strongly promoted, since its exotic connotations helped the new drink to sell. Coffeehouse keepers wore turbans, or called their shops "Turk's Head" and suchlike.<ref name="Çaksu">{{cite book |author-last=Çaksu |author-first=Ali |date=2018 |chapter="Turkish Coffee as a Political Drink from the Early Modern Period to Today |title=From Kebab to Ćevapčići: Foodways in (Post) Ottoman Europe |editor-first1=Arkadiusz |editor-last1=Blaszczyk |editor-first2=Stefan |editor-last2=Rohdewald |location=Wiesbaden, Germany |publisher=] |pages=124–143 |isbn=978-3-44711107-2}}</ref> Especially in France there was a craze for things Turkish: fashion plates depicted aristocratic ladies taking coffee while dressed as ]s, attended by servants in Moorish costume. Its medical value was stressed: it became popular in France when doctors advised ] was good for the health.<ref name="Landweber"/>{{rp|201, 203–208, 211}} In England, the earliest advertisement (1652) for a coffee house — owned by Pasqua Rosée, an Armenian from ] (modern Dubrovnik) — claimed that Turkish people "are not troubled with the ], ], ], or ]" and "their skins are exceedingly cleer and white". Despite this, Rosée's product was weak enough to be drunk a half pint (485 ml) at a time on an empty stomach,<ref name="Ukers"/>{{rp|53, 55}} not an attribute of real Turkish coffee. If there were 'Turkish' coffeehouses in Oxford or Paris, the cited historical sources do not show they were serving coffee made in the Turkish manner. | |||

| The real Ottoman influence was on European coffee house culture. "The coffeehouse and café, far from being English and French creations, were at heart an import from Mecca, Cairo, and Constantinople",<ref name="Landweber"/>{{rp|198}} a topic outside the scope of this article. | |||

| ====America==== | |||

| The first person who brought coffee to America may have been ] and, since he had been in Turkish service (he had been enslaved and given to a '']''{{'s}} mistress),<ref>{{cite journal |author-last=Barbour |author-first=Philip L. |date=1957 |title=Captain John Smith's Route through Turkey and Russia |journal=The William and Mary Quarterly |volume=14 |issue=3 |pages=358–369 |doi=10.2307/1915649 |jstor=1915649}}</ref> conceivably he prepared it in the Turkish manner. Already by 1683 ] was complaining about the price of coffee in Pennsylvania.<ref name="Topik2004"/>{{rp|13}} | |||

| ===Decline=== | |||

| In the 20th century, especially in wartime and the 1950s, shortages in Turkey meant that coffee was scarcely available for years at a time, or was adulterated with ] and other substances. Habits changed; the old coffee culture declined; the epicurean coffee aficionado was less to be seen. Although still important in Turkish tradition, today Turks drink more tea than coffee.<ref name="Ayvazoğlu"/>{{rp|6–7, 84–85, 93–100, 150}} A survey of Turkish regions found that in some areas "coffee" was made without using coffee beans at all.<ref name="Demir">{{cite journal |author-last1=Demir |author-first1=Yeliz |author-last2=Bertan |author-first2=Serkan |date=2023 |title=Spatial distribution of Türkiye's local Turkish coffee kinds |journal=Journal of Ethnic Foods |volume=10 |issue=32 |doi=10.1186/s42779-023-00200-8 |doi-access=free}}</ref> By 2018 there were said to be over 400 ] stores in Istanbul alone, and younger Turks were embracing ].<ref name="Ayöz">{{cite thesis |author-last=Ayöz |author-first=Sila |date=2018 |title=Coffee is the New Wine : An Ethnographic Study of Third Wave Coffee in Ankara |degree=M.Sc. |publisher=Middle East Technical University |url=https://open.metu.edu.tr/handle/11511/27878|access-date=26 April 2024}}</ref>{{rp|59, 62}} The most popular brand in Turkey is ].<ref>{{cite journal |author-last=Köse |author-first=Yavuz |date=2019 |title="The fact is, that Turks can't live without coffee…" the introduction of Nescafé into Turkey (1952–1987) |journal=Journal of Historical Research in Marketing |volume=11 |issue=3 |pages=295–316 |doi=10.1108/JHRM-03-2018-0012}}</ref> However, ] has inscribed Turkish coffee culture and tradition on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity,<ref name="Demir"/>{{rp|2}} and "there still exist serious aficionados who would never trade the taste of Turkish coffee with anything else".<ref name="Ayvazoğlu"/>{{rp|7}} | |||

| ==Culture== | |||

| ===Fortune-telling=== | |||

| ] | |||

| {{main|Tasseography}} | |||

| The grounds left after drinking Turkish coffee are sometimes used to ], a practice known as ].<ref>{{cite web |author-last=Nissenbaum |author-first=Dion |title=Coffee grounds brewed trouble for Israeli fortuneteller |url=http://www.mcclatchydc.com/2007/07/20/18168/coffee-grounds-brewed-trouble.html |website=McClatchyDC |access-date=27 November 2014 |date=20 July 2007}}</ref> The cup is turned over into the ] to cool, and the patterns of the coffee grounds are interpreted. | |||

| ===Turkish weddings=== | |||

| As well as being an everyday beverage, Turkish coffee is also a part of the traditional Turkish wedding custom. As a prologue to marriage, the bridegroom's parents (in the lack of his father, his mother and an elderly member of his family) must visit the young girl's family to ask the hand of the bride-to-be and the blessings of her parents upon the upcoming marriage. During this meeting, the bride-to-be must prepare and serve Turkish coffee to the guests. For the groom's coffee, the bride-to-be sometimes uses salt instead of sugar to gauge his character. If the bridegroom drinks his coffee without any sign of displeasure, the bride-to-be assumes that the groom is good-tempered and patient. As the groom already comes as the demanding party to the girl's house, in fact it is the boy who is passing an exam and etiquette requires him to receive with all smiles this particular present from the girl.<ref>Köse, Nerin (nd). . Ege University. (2008)</ref> In some regions, however, "if the coffee is brewed without any froth, it means 'You have no chance!'"<ref name="Ayvazoğlu"/>{{rp|71}} | |||

| ==Names and variants== | ==Names and variants== | ||

| ] | |||

| There is controversy about its name e.g. in some ex-Ottoman dependencies, mostly due to nationalistic feelings or political rivalry with Turkey.<ref name="Kakissis2">{{Cite web |author-last=Kakissis |author-first=Joanna |date=27 April 2013 |title=Don't Call It 'Turkish' Coffee, Unless, Of Course, It Is |url=https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2013/04/27/179270924/dont-call-it-turkish-coffee-unless-of-course-it-is |access-date=5 October 2022 |website=NPR}}</ref> | |||

| === |

===Within Turkey=== | ||

| '''Dibek Coffee''' | |||

| In ], Turkish coffee is also called "Bosnian coffee" (Bosnian: ''bosanska kahva''), which is made slightly differently from its Turkish counterpart. A deviation from the Turkish preparation is that when the water reaches its boiling point, a small amount is saved aside for later, usually in a ]. Then, the coffee is added to the pot (]), and the remaining water in the cup is added to the pot. Everything is put back on the heat source to reach its ] again, which only takes a couple of seconds since the coffee is already very hot.<ref>{{Cite web | |||

| | last = Cohen | |||

| | first = Brad | |||

| | title = The complicated culture of Bosnian coffee | |||

| | work = BBC - Travel: Food & Drink | |||

| | accessdate = 2014-07-24 | |||

| | date = 2014-07-16 | |||

| | url = http://www.bbc.com/travel/feature/20140707-the-complicated-culture-of-bosnian-coffee | |||

| }}</ref> Coffee drinking in Bosnia is a traditional daily custom and plays an important role during social gatherings. | |||

| Dibek Coffee is a type of Turkish coffee named after the traditional method used to grind the beans. Originally, “dibek” referred to two slightly indented stones used to crush roasted coffee beans by rubbing them together. Over time, the design of the dibek became deeper and more practical. | |||

| === Czech Republic and Slovakia=== | |||

| ] | |||

| The roasted beans are crushed in the dibek using a wooden or iron hammer until they reach the desired size. Unlike finely powdered coffee, the coffee ground in a dibek has a coarse texture. This method preserves the aromatic oils in the coffee, enhancing its flavor and helping to maintain its foam during cooking. | |||

| A beverage called "''turecká káva''" or "''turek''" is also very popular in the ] and ], even if more sophisticated forms of coffee preparation (such as ]) have become widespread in the last few decades, decreasing the popularity of ''turek''. Cafés usually do not serve ''turek'' any more, in contrast to pubs and kiosks, but ''turek'' is still often served in households. The Czech and Slovak form of Turkish coffee is different from Turkish coffee in Turkey, the Arab world or Balkan countries, since ''cezve'' is not used. It is in fact the simplest possible method to make coffee: ground coffee is poured with boiling or almost boiling water. The weight of coffee and the volume of water depend only on the taste of the consumer. In recent years, genuine Turkish coffee made in a ''cezve'' (''džezva'' in Czech) has also appeared, but Turkish coffee is still understood, in most cases, as described above.<ref>LAZAROVÁ Daniela, , ''Radio Prague'', May 12, 2011.</ref><ref>Piccolo neexistuje, ''''.</ref> | |||

| Dibek Coffee is recognized as a local specialty in various regions of Türkiye. It is traditionally prepared in a coffeehouse in Kırklareli that has been operating for 142 years. It is also considered a local product in the Gökçeada district of Çanakkale and Zeytinliköy. Additionally, Dibek Coffee is highlighted as a gastronomic representative of İzmir and its surrounding areas, including Urla, Seferihisar, Sığacık, Çeşme, Alaçatı, and nearby villages.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Demir |first1=Yeliz |last2=Bertan |first2=Serkan |title=Spatial distribution of Türkiye's local Turkish coffee kinds |journal=Journal of Ethnic Foods |date=11 September 2023 |volume=10 |issue=1 |pages=32 |doi=10.1186/s42779-023-00200-8 |doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| '''Cilveli Coffee''' | |||

| Cilveli Coffee is made by adding a mixture of double-roasted ground almonds and two spices to foamy Turkish coffee in a cup. A spoon is served alongside the coffee, allowing the guest to first eat the almond mixture on top before drinking the coffee. The combination of the almond mixture and foam creates a unique flavor. Double-roasting the almonds prevents them from sinking to the bottom of the coffee. | |||

| Cilveli Coffee is a traditional type of Turkish coffee from Manisa. Historically, it was prepared for princes, and in Manisa, it is also part of marriage rituals. Young women would offer this coffee to show their approval of a suitor and his family during a visit.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Demir |first1=Yeliz |last2=Bertan |first2=Serkan |title=Spatial distribution of Türkiye's local Turkish coffee kinds |journal=Journal of Ethnic Foods |date=11 September 2023 |volume=10 |issue=1 |pages=32 |doi=10.1186/s42779-023-00200-8 |doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| ===Armenia=== | |||

| This type of strong coffee is a standard of ] households. The main difference is that ] is used in Armenian coffee.<ref>{{cite web |title=Armenian Coffee vs Turkish Coffee |url=https://acoffeeexplorer.com/armenian-coffee-vs-turkish-coffee/ |website=Coffee Explorer |date=6 July 2023}}</ref> Armenians introduced the coffee to ] when they settled the island, where it is known as "eastern coffee" due to its Eastern origin. Corfu, which had never been part of the Ottoman holdings, did not have an established ] before it was introduced by the Armenians.<ref>{{cite web |title=A Forgotten Armenian History on a Small Greek Island |website=The Armenian Weekly |date=28 August 2019 |url=https://armenianweekly.com/2019/08/28/a-forgotten-armenian-history-on-a-small-greek-island/}}</ref> According to ''The Reuben Percy Anecdotes'' compiled by journalist ], an Armenian opened a coffee shop in Europe in 1674, at a time when coffee was first becoming fashionable in the West.<ref>{{cite book |publisher=T. Boys |author-last1=Percy |author-first1=Reuben |author-last2=Percy |author-first2=Sholto |title=The Percy Anecdotes: Conviviality |date=1823 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ytFCAQAAIAAJ&pg=PA27}}</ref> | |||

| The term ''Turkish coffee'' is still used in many languages but in ] it is either called {{langx|hy|հայկական սուրճ|lit=Armenian coffee|translit=haykakan surč|label=none}}, or {{langx|hy|սեւ սուրճ|lit=black coffee|translit=sev surč|label=none}}, referring to the traditional preparation done without milk or creamer. If unsweetened it is called 'bitter' ({{Langx|hy|դառը|translit=daruh|label=none}}) in Armenia, but more commonly it is brewed with a little sugar (''normal'').<ref>{{cite book |title=Armenia |date=2019 |publisher=Bradt Travel Guides |page=104 |isbn=978-1-78477079-2 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Upx-DwAAQBAJ}}</ref> Armenians will sometimes serve a plate of ], ], or ] alongside the coffee.<ref>{{cite book |publisher=Arcadia Publishing |isbn=978-1-4396-1884-4 |author-last1=Broglin |author-first1=Sharon |author2=Allen Park Historical Museum |title=Allen Park |date=2007-05-09 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=vI5WZeZuziEC&pg=PT121}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |author-first1=Timothy G. |author-last1=Roufs |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=M_eCBAAAQBAJ&pg=PA11 |title=Sweet Treats around the World: An Encyclopedia of Food and Culture |author-last2=Smyth Roufs |author-first2=Kathleen |date=29 July 2014 |isbn=978-1-61069221-2 |pages=11 |publisher=Abc-Clio}}</ref> | |||

| === Czech Republic, Slovakia, Poland and Lithuania === | |||

| A beverage called {{Lang|cs|turecká káva}} or {{Lang|cs|turek}} is very popular in the ] and ], although other forms of coffee preparation such as ] have become more popular in the last few decades, decreasing the popularity of ''{{Lang|cs|turek}}''. ''{{Lang|cs|Turek}}'' is usually no longer served in cafés, but it is prepared in pubs and kiosks, and in homes. The Czech and Slovak form of Turkish coffee is different from Turkish coffee in Turkey, the Arab world or Balkan countries, since a {{Lang|tr|cezve}} is not used; instead the desired amount of ground coffee is put in a cup and boiling or almost boiling water is poured over it. In recent years, Turkish coffee is also made in a ''{{Lang|tr|cezve}}'' ({{Lang|cs|džezva}} in Czech), but ''Turkish coffee'' usually means the method described above.<ref>Lazarová, Daniela, , ''Radio Prague'', 12 May 2011.</ref><ref>Piccolo neexistuje, ''''.</ref> Coffee is prepared in the same way in Poland<ref>{{cite web |url=https://ottomania.pl/kawa-po-turecku-jak-ja-parzyc/ |title=Kawa po turecku – jak ją parzyć? |work=ottomania.pl |date=26 February 2018 |access-date=6 December 2019}}</ref> and Lithuania.<ref>TV3.lt, , retrieved 16 February 2018.</ref> | |||

| ===Greece=== | ===Greece=== | ||

| In Greece, Turkish coffee was formerly referred to simply as |

In Greece, Turkish coffee was formerly referred to simply as 'Turkish' ({{Lang|el|τούρκικος}}). But political tensions with Turkey in the 1950s led to the ] ''Greek coffee'' ({{Lang|el|ελληνικός καφές}}),"<ref name="Karakatsanis">Leonidas Karakatsanis, ''Turkish-Greek Relations: Rapprochement, Civil Society and the Politics of Friendship'', Routledge, 2014, {{isbn|0-41573045-7}}, p. 111 and footnote 26: "The eradication of symbolic relations with the 'Turk' was another sign of this reactivation: the success of an initiative to abolish the word 'Turkish' in one of the most widely consumed drinks in Greece, i.e. 'Turkish coffee', is indicative. In the aftermath of the Turkish intervention in Cyprus, the Greek coffee company Bravo introduced a widespread advertising campaign titled 'We Call It Greek' (''Emeis ton leme Elliniko''), which succeeded in shifting the relatively neutral 'name' of a product, used in the vernacular for more than a century, into a reactivated symbol of identity. 'Turkish coffee' became 'Greek coffee' and the use of one name or the other became a source of dispute separating 'traitors' from 'patriots'."</ref><ref>{{cite book |author-link=George Mikes |author-last=Mikes |author-first=George |title=Eureka!: Rummaging in Greece |date=1965 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=06UVAQAAMAAJ&q=%22Greek+coffee%22 |page=29 |quote-page=29 |quote=Their chauvinism may sometimes take you a little aback. Now that they are quarrelling with the Turks over Cyprus, Turkish coffee has been renamed Greek coffee; }}</ref> which became even more popular after the ] in 1974:<ref name="Karakatsanis"/> " ] at all levels became strained, 'Turkish coffee' became 'Greek coffee' by substitution of one Greek word for another while leaving the Arabic loan-word, for which there is no Greek equivalent, unchanged."<ref>{{cite book |author-link=Robert Browning (Byzantinist) |author-first=Robert |author-last=Browning |title=Medieval and Modern Greek |date=1983 |isbn=0-521-29978-0 |page=16 |publisher=]}}</ref><ref name="Kakissis1">Joanna Kakissis, "Don't Call It 'Turkish' Coffee, Unless, Of Course, It Is", ''The Salt'', National Public Radio : '"It wasn't always this way," says Albert Arouh, a Greek food scholar who writes under a pen name, Epicurus. "When I was a kid in the 1960s, everyone in Greece called it Turkish coffee." Arouh says he began noticing a name change after 1974, when the Greek military junta pushed for a coup in Cyprus that provoked Turkey to invade the island.' "The invasion sparked a lot of nationalism and anti-Turkish feelings," he says. "Some people tried to erase the Turks entirely from the coffee's history, and re-baptized it Greek coffee. Some even took to calling it Byzantine coffee, even though it was introduced to this part of the world in the sixteenth century, long after the Byzantine Empire's demise." By the 1980s, Arouh noticed it was no longer politically correct to order a "Turkish coffee" in Greek cafes. By the early 1990s, Greek coffee companies like Bravo (now owned by DE Master Blenders 1753 of the Netherlands) were producing commercials of sea, sun and nostalgic village scenes and declaring "in the most beautiful country in the world, we drink Greek coffee."'</ref> There were even advertising campaigns promoting the name ''Greek coffee'' in the 1990s.<ref name="Kakissis1"/> The name for a coffee pot remains either a {{Lang|el-latn|briki}} ({{Lang|el|μπρίκι}}) in mainland Greek or a {{Lang|el-latn|tzisves}} ({{Lang|el|τζισβές}}) in Cypriot Greek. | ||

| == |

===Former Yugoslavia=== | ||

| {{further|Coffee culture in former Yugoslavia}} | |||

| As well as being an everyday beverage, Turkish coffee is also a part of the traditional Turkish wedding custom. As a prologue to marriage, the bridegroom's parents (in the lack of his father, his mother and an elderly member of his family) must visit the young girl's family to ask the hand of the bride-to-be and the blessings of her parents upon the upcoming marriage. During this meeting, the bride-to-be must prepare and serve Turkish coffee to the guests. For the groom's coffee, the bride-to-be sometimes uses salt instead of sugar to gauge his character. If the bridegroom drinks his coffee without any sign of displeasure, the bride-to-be assumes that the groom is good-tempered and patient. As the groom already comes as the demanding party to the girl's house, in fact it is the boy who is passing an exam and etiquette requires him to receive with all smiles this particular present from the girl, although in some parts of the country this may be considered as a lack of desire on the part of the girl for marriage with that candidate.<ref>KÖSE, Nerin (nd). . Ege University.</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| {{anchor|Bosnia and Herzegovina}}In ], Turkish coffee is also called ''Bosnian coffee'' ({{Langx|bs|bosanska kahva}}), which is made slightly differently from its Turkish counterpart. A deviation from the Turkish preparation is that when the water reaches its boiling point, a small amount is saved aside for later, usually in a ]. Then, the coffee is added to the pot ({{Lang|bs|]}}), and the remaining water in the cup is added to the pot. Everything is put back on the heat source to reach its ] again, which only takes a couple of seconds since the coffee is already very hot.<ref name="Cohen_2014"/> Coffee drinking in Bosnia is a traditional daily custom and plays an important role during social gatherings. | |||

| {{anchor|Serbia}}In ], ], ], ], and ] it is called 'Turkish coffee'{{Efn|{{Langx|sr|турска кафа|turska kafa}};{{Langx|sl|turška kava}}; {{Langx|hr|turska kava}}}}, 'domestic coffee'{{Efn|{{Langx|sr|домаћа кафа|domaća kafa}}; {{Langx|sl|domača kava}}; {{Langx|hr|domaća kava}}}} or simply 'coffee'{{Efn|{{Langx|sr|кафа|kafa}}; {{Langx|sl|kava}}; {{Langx|hr|kava}}}}. It is nearly identical to the Turkish version. In Serbia, Turkish coffee is also called {{Lang|sr|српска кафа}} ({{Transliteration|sr|srpska kafa}}), which means 'Serbian coffee'.<ref></ref> | |||

| ==Fortune-telling== | |||

| Superstition says the grounds left after drinking Turkish coffee can be used for fortune-telling.<ref>{{cite web|last1=Nissenbaum|first1=Dion|title=Coffee grounds brewed trouble for Israeli fortuneteller|url=http://www.mcclatchydc.com/2007/07/20/18168/coffee-grounds-brewed-trouble.html|website=McClatchyDC|accessdate=27 November 2014|date=20 July 2007}}</ref> The cup is commonly turned over into the ] to cool, and it is believed by some that the patterns of the coffee grounds can be used for a method of ] known as ] ({{Lang-tr|kahve falı}}, {{Lang-el|καφεμαντεία}}, ''kafemanteia'', {{Lang-ar|قراءة الفنجان}}, ''qira'at al-fenjaan'', {{Lang-de|Kaffesatzlesen}}, {{Lang-sr|гледање у шољу / gledanje u šolju}}), or tasseomancy. | |||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| {{ |

{{Portal|Coffee}} | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| == |

==Notes== | ||

| {{reflist|group="nb"|refs= | |||

| {{Reflist}} | |||

| <ref group="nb" name="NB_Robusta">The '']'' species originated further south, in the ], but it was not adapted for human consumption until much later.</ref> | |||

| }} | |||

| ==References== | |||

| == External links == | |||

| {{reflist|refs= | |||

| {{Commons category|Turkish coffee|position=left}} | |||

| <ref name="Cohen_2014">{{cite web |url=http://www.bbc.com/travel/story/20140707-the-complicated-culture-of-bosnian-coffee |title=The complicated culture of Bosnian coffee |date=2014-07-16 |orig-date=2014-07-07 |author-first=Brad |author-last=Cohen |publisher=] |department=Travel: Food & Drink |access-date=19 August 2015 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240501201310/https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20140707-the-complicated-culture-of-bosnian-coffee |archive-date=2024-05-01}}</ref> | |||

| }} | |||

| ==Further reading== | |||

| * {{cite book |title=Turkish Coffee |language=en |author-first1=M. Sabri |author-last1=Koz |author-first2=Kemalettin |author-last2=Kuzucu |translator-first=Mary P. |translator-last=Işın |editor-first=Begüm |editor-last=Kovulmaz |date=May 2014 |orig-date=February 2013, December 2012 |edition=2nd printing, 1st |publication-place=Istanbul, Turkey |publisher=] / ] (YKY) |isbn=978-975-08-2474-6 |id=MPN 3820. Certificates 12034, 12334}} (271 pages) | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| {{Commons category|Turkish coffee|position=right}} | |||

| {{Coffee|nocat=1}} | {{Coffee|nocat=1}} | ||

| Line 56: | Line 160: | ||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Turkish Coffee}} | {{DEFAULTSORT:Turkish Coffee}} | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 00:39, 12 January 2025

Coffee brewing method without filters

A cup of Turkish coffee, served from a copper cezve A cup of Turkish coffee, served from a copper cezve | |

| Type | Coffee |

|---|---|

| Country of origin | Disputed |

| Color | Dark brown |

Turkish coffee is a style of coffee prepared in a cezve using very finely ground coffee beans without filtering.

Preparation

Turkish coffee is very finely ground coffee brewed by boiling. Any coffee bean may be used; arabica varieties are considered best, but robusta or a blend is also used. The coffee grounds are left in the coffee when served. The coffee may be ground at home in a manual grinder made for the very fine grind, ground to order by coffee merchants in most parts of the world, or bought ready-ground from many shops.

Coffee and water, usually with added sugar, is brought to the boil in a special pot called cezve in Turkey, and often called ibrik elsewhere. As soon as the mixture begins to froth, and before it boils over, it is taken off the heat; it may be briefly reheated twice more to increase the desired froth. Sometimes about one-third of the coffee is distributed to individual cups; the remaining amount is returned to the fire and distributed to the cups as soon as it comes to the boil. The coffee is traditionally served in a small porcelain cup called a kahve fincanı 'coffee cup'.

Another ancient tradition involves placing the cezve filled with coffee in a pan filled with hot sand. The pan is heated over an open flame, thereby letting the sand take total control of the heat. The heat created by the sand lets the coffee foam to the top almost immediately. The heat can also be adjusted by the depth of the cezve in the sand. This process is usually repeated three to four times and then the coffee is finally served in small cups called demitasse cups.

The amount of sugar is specified when ordering the coffee. It may be unsweetened (Turkish: sade kahve), with little or moderate sugar (Turkish: az şekerli kahve, orta şekerli kahve or orta kahve), or sweet (Turkish: çok şekerli kahve). Coffee is often served with something small and sweet to eat, such as Turkish delight. It is sometimes flavoured with cardamom, mastic, salep, or ambergris. A lot of the powdered coffee grounds are transferred from the cezve to the cup; in the cup, some settle on the bottom but much remains in suspension and is consumed with the coffee.

According to connoisseurs

In a paper for the 2013 Oxford Food Symposium, Tan and Bursa identified the features of the art or craft of making and serving Turkish coffee, according to the traditional procedures:

- Roasting. Ideally the best green Arabica beans are medium-roasted in small quantities over steady heat in a shallow, wrought-iron roasting pan. It is crucial to stop at the right moment, then transfer the beans to the next stage:

- Cooling. The beans are allowed to cool down in a wooden box and absorb excess oil. The kind of wood is claimed to affect the taste, walnut being the best.

- Pounding or grinding. The beans must be reduced into a very fine powder. The fineness of the powder is crucial to the success of Turkish coffee since it affects the foam and mouth feel. (According to one source, the particle size should be 75–125 microns.) Strict connoisseurs insist that they must be hand-pounded in a wooden mortar, although it is difficult to do this while achieving a uniform fineness. Consequently, it has become more usual to grind them in a brass or copper mill, though it does make for drier particles.

- Brewing. It is essential to use a proper cezve. This vessel is a conical flask, being wider at the base than at the neck, and is made of thick forged copper. (A common sized cezve will make one cup of coffee, and they can easily be ordered online in many western countries.) Cold water, several teaspoons of the ground coffee (at least 7 grams per person) and any sugar are put in the cezve and it is put on the fire. The tapering shape of the vessel encourages the formation of foam and retains the volatile aromas. The coffee should never be allowed to come to a rolling boil, and must not be over-done. "This stage requires close monitoring and delicate timing since a good Turkish coffee has the thickest possible layer of froth at the top". Some think that the metallic copper helps to improve the taste.

- Serving. The cezve has a spout by which it is poured into the serving cup. While the cup design might not seem to have anything to do with the taste of the beverage, connoisseurs say it makes a difference. The best cups are made of porcelain with a thin rim: it affects mouth feel. A long cultural tradition emphasises the pleasure of being served coffee in beautiful cups, which are family heirlooms. The beverage is served together with a glass of water which should be sipped first to cleanse the mouth. Other cultural traditions affect the guest's appreciation of the beverage and the conviviality of the occasion, including story-telling, fortune-telling, and so forth.

While some of these stages may be curtailed in modern coffee drinking, for example the coffee might be purchased already roasted and ground, the rituals and paraphernalia (e.g. the anticipatory smell of the roasting beans) do act on the imagination and have a psychological effect.

History

Further information: Ottoman coffeehouse

Coffee drinking spread in the Islamic world in the 16th century. From the Hijaz it arrived in Cairo; from thence it went to Syria and Istanbul. The coffee tree was first cultivated commercially in the Yemen, having been introduced there from the rainforests of Ethiopia where it grew wild. For a long time Yemenis had a world monopoly on the export of coffee beans (according to Carl Linnaeus, by deliberately destroying their ability to germinate). For nearly a century (1538–1636) the Ottoman Empire controlled the southern coastal region of the Yemen, notably its famous coffee port Mocha. In the 18th century Egypt was the richest province of the Ottoman Empire, and the chief commodity it traded was Yemeni coffee. Cairo merchants were responsible for moving it from the Yemen to markets in the Islamic world.

Coffee was in use in Istanbul by 1539, for a legal document mentions Ottoman admiral Barbaros Hayreddin Pasha's house had a coffee chamber. It appears that the first coffeehouse in Istanbul was opened in 1554 (some say 1551) by Hakem of Aleppo and Șems of Damascus (they may have been separate establishments at first). Soon, coffeehouses spread all over Istanbul and even to small towns in Anatolia.

Ignatius d'Ohsson described for French readers the Turkish method of brewing coffee (Tableau Général de l'Empire Othoman, 1789). His description, translated in this note, closely resembles the present day version, including the production of foam. From the traveller Jean de Thévenot it appears Turks were using it at least a century before that. He mentions that they drank it black; some added cloves, cardamom or sugar, but it was thought to be less healthy, and until recently, an older generation of connoisseurs disdained the habit of sugaring Turkish coffee.

Origin of the Turkish method

There are inconsistent claims as to the origin of Turkish coffee. Without citing historical sources, some authors have asserted the method originated in the Yemen. or in Damascus (a plausible, if unsubstantiated claim, since the Middle Eastern coffeehouse did probably originate in Damascus and was brought to Istanbul by Syrians, see above); or with the Turkish people themselves.

Yemenis may have been the first to consume coffee as a hot beverage (instead of chewing the bean, or adding it to solid food) and the earliest social users were probably Sufi mystics in that region who needed to stay awake for their nocturnal vigils. However a 1762 Danish scientific expedition noted that Yemenis did not like coffee made the "Turkish" way, and rarely drank it, thinking it bad for the health: they much preferred kisher, a beverage made of the coffee shells which more closely resembled a tea; Likewise, according to scientist John Ellis (1774), French visitors to the Yemeni royal court noticed that only a version was drunk made from coffee husks with a colour like beer. In 1910, the U.S. consul at Aden reported

the Yemen Arab never uses coffee himself, contrary to general opinion and the reports of some travelers, but raises it almost wholly for export. He uses kishar, a beverage he brews from the dried hulls, in large quantities... So little is coffee used by the people that a few months after the new crop has been gathered it is impossible for one passing through the country to buy a single pound

and it has been said that Yemenis do not drink much coffee to this day.

If Turkish coffee is defined as "a very strong black coffee served with the fine grounds in it", then the method is generic in Middle Eastern cities (in rural areas a different method is used and is called Arabic coffee) and goes by various other names too, such as Egyptian coffee, Syrian coffee, and so forth, though there may be some local variations.

Illegality and acceptance

The English word coffee derives from Turkish kahve, which came from Arabic qahwah, which could mean 'wine'. It is sometimes stated that coffee was forbidden in Islam, albeit the ban was not very effective. However, it seems most Muslim religious scholars actually supported coffee, or were not averse to it on principle. It was governments who wanted to suppress coffee gatherings, fearing they were foci of political dissent. "What was condemned was not caffeine's physiological effects but rather the freedom of coffeehouse talk which rulers considered subversive".

Already in 1543 several ships were ordered to be sunk in Istanbul harbour for importing coffee. Under Sultan Murad IV those found keeping a coffeehouse were cudgelled for a first offence, sewn in a bag and thrown into the Bosphorus for a second. These bans were sporadic and often ignored. (Similarly, the government of Charles II of England tried to suppress coffee houses as seditious gatherings - the ban lasted a few days - and, much later, the republican government of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk tried to prohibit or discourage coffeehouses in Turkish villages, saying they were places where men gathered to waste their time). Eventually the authorities found it to their advantage to tax the trade not suppress it. Fifteen years after coffee arrived in Istanbul there were over 600 coffeehouses, wrote an Armenian historian.

To prepare Turkish coffee very well is not easy, and prominent Ottoman Turks kept specialist coffee cooks for the purpose. Sultan Süleyman had a kahvecibasi or chief coffee-cook, and it became a traditional practice for sultans. To demonstrate the civility of their rule, they built magnificent coffeehouses in newly conquered parts of the Ottoman Empire.

International diffusion

Western Europe

From the Ottoman Empire, coffee-drinking spread to western Europe, probably being first introduced into Venice, where it was consumed as a medicine. Early consumers were travellers who imported it for their own use. Other early users were virtuosi: gentleman-scholars curious about the outside world and willing to try exotic products. Since these early adopters were trying to recreate the genuine article, probably they were making proper Turkish coffee, or at least something like it. For example, Jean de Thévenot imported authentic ibriks from the Ottoman Empire.

However, most early modern Europeans did not like coffee, which is an acquired taste, and especially they did not like the black, bitter Turkish version. In any case it was too expensive: in France, coffee beans sold for the equivalent of $8,000 a kilo. Coffee did not become a popular beverage until it was altered to appeal to European palates and its price drastically lowered, as follows.

The Yemeni coffee monopoly was broken by the Dutch, who managed to obtain viable coffee plants from Mocha and propagated them to their empire in Java. They were followed by the French, who planted a tree at the Jardin des Plantes de Paris; it has been claimed that "This tree was destined to be the progenitor of most of the coffee of the French colonies, as well as those of South America, Central America, and Mexico", i.e. most of the coffee in the world, though it has been called "a neat story". By the time of the French Revolution, 80% of the world's coffee was grown in the Americas and French coffee was ousting the Yemeni product in Cairo, even being exported back to Mocha itself. The price of coffee fell so much that by mid-18th century it was accessible to French townspeople of all classes.

When coffee was eventually popularised, what was served was not genuine Turkish coffee, but a product heavily diluted with water (much weaker than modern espresso) or milk, and sweetened with sugar. "Combining coffee with fresh milk turned a Turkish drink into a French one". Already in 1689, in a paper for fellow scientists at the Royal Society, London, John Houghton though stressing coffee's Ottoman origins, said very good coffee was made by boiling the grounds in plenty of water and letting them settle, leaving a clear, reddish liquor: which is not Turkish coffee.

Despite this, the "Turkish" connection was strongly promoted, since its exotic connotations helped the new drink to sell. Coffeehouse keepers wore turbans, or called their shops "Turk's Head" and suchlike. Especially in France there was a craze for things Turkish: fashion plates depicted aristocratic ladies taking coffee while dressed as sultanas, attended by servants in Moorish costume. Its medical value was stressed: it became popular in France when doctors advised café au lait was good for the health. In England, the earliest advertisement (1652) for a coffee house — owned by Pasqua Rosée, an Armenian from Ragusa (modern Dubrovnik) — claimed that Turkish people "are not troubled with the Stone, Gout, Dropsie, or Scurvey" and "their skins are exceedingly cleer and white". Despite this, Rosée's product was weak enough to be drunk a half pint (485 ml) at a time on an empty stomach, not an attribute of real Turkish coffee. If there were 'Turkish' coffeehouses in Oxford or Paris, the cited historical sources do not show they were serving coffee made in the Turkish manner.

The real Ottoman influence was on European coffee house culture. "The coffeehouse and café, far from being English and French creations, were at heart an import from Mecca, Cairo, and Constantinople", a topic outside the scope of this article.

America

The first person who brought coffee to America may have been Captain John Smith and, since he had been in Turkish service (he had been enslaved and given to a pasha's mistress), conceivably he prepared it in the Turkish manner. Already by 1683 William Penn was complaining about the price of coffee in Pennsylvania.

Decline

In the 20th century, especially in wartime and the 1950s, shortages in Turkey meant that coffee was scarcely available for years at a time, or was adulterated with chickpeas and other substances. Habits changed; the old coffee culture declined; the epicurean coffee aficionado was less to be seen. Although still important in Turkish tradition, today Turks drink more tea than coffee. A survey of Turkish regions found that in some areas "coffee" was made without using coffee beans at all. By 2018 there were said to be over 400 Starbucks stores in Istanbul alone, and younger Turks were embracing third-wave coffee. The most popular brand in Turkey is Nescafé. However, UNESCO has inscribed Turkish coffee culture and tradition on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, and "there still exist serious aficionados who would never trade the taste of Turkish coffee with anything else".

Culture

Fortune-telling

The grounds left after drinking Turkish coffee are sometimes used to tell fortunes, a practice known as tasseography. The cup is turned over into the saucer to cool, and the patterns of the coffee grounds are interpreted.

Turkish weddings

As well as being an everyday beverage, Turkish coffee is also a part of the traditional Turkish wedding custom. As a prologue to marriage, the bridegroom's parents (in the lack of his father, his mother and an elderly member of his family) must visit the young girl's family to ask the hand of the bride-to-be and the blessings of her parents upon the upcoming marriage. During this meeting, the bride-to-be must prepare and serve Turkish coffee to the guests. For the groom's coffee, the bride-to-be sometimes uses salt instead of sugar to gauge his character. If the bridegroom drinks his coffee without any sign of displeasure, the bride-to-be assumes that the groom is good-tempered and patient. As the groom already comes as the demanding party to the girl's house, in fact it is the boy who is passing an exam and etiquette requires him to receive with all smiles this particular present from the girl. In some regions, however, "if the coffee is brewed without any froth, it means 'You have no chance!'"

Names and variants

There is controversy about its name e.g. in some ex-Ottoman dependencies, mostly due to nationalistic feelings or political rivalry with Turkey.

Within Turkey

Dibek Coffee

Dibek Coffee is a type of Turkish coffee named after the traditional method used to grind the beans. Originally, “dibek” referred to two slightly indented stones used to crush roasted coffee beans by rubbing them together. Over time, the design of the dibek became deeper and more practical.

The roasted beans are crushed in the dibek using a wooden or iron hammer until they reach the desired size. Unlike finely powdered coffee, the coffee ground in a dibek has a coarse texture. This method preserves the aromatic oils in the coffee, enhancing its flavor and helping to maintain its foam during cooking.

Dibek Coffee is recognized as a local specialty in various regions of Türkiye. It is traditionally prepared in a coffeehouse in Kırklareli that has been operating for 142 years. It is also considered a local product in the Gökçeada district of Çanakkale and Zeytinliköy. Additionally, Dibek Coffee is highlighted as a gastronomic representative of İzmir and its surrounding areas, including Urla, Seferihisar, Sığacık, Çeşme, Alaçatı, and nearby villages.

Cilveli Coffee

Cilveli Coffee is made by adding a mixture of double-roasted ground almonds and two spices to foamy Turkish coffee in a cup. A spoon is served alongside the coffee, allowing the guest to first eat the almond mixture on top before drinking the coffee. The combination of the almond mixture and foam creates a unique flavor. Double-roasting the almonds prevents them from sinking to the bottom of the coffee.

Cilveli Coffee is a traditional type of Turkish coffee from Manisa. Historically, it was prepared for princes, and in Manisa, it is also part of marriage rituals. Young women would offer this coffee to show their approval of a suitor and his family during a visit.

Armenia

This type of strong coffee is a standard of Armenian households. The main difference is that cardamom is used in Armenian coffee. Armenians introduced the coffee to Corfu when they settled the island, where it is known as "eastern coffee" due to its Eastern origin. Corfu, which had never been part of the Ottoman holdings, did not have an established Ottoman coffee culture before it was introduced by the Armenians. According to The Reuben Percy Anecdotes compiled by journalist Thomas Byerley, an Armenian opened a coffee shop in Europe in 1674, at a time when coffee was first becoming fashionable in the West.

The term Turkish coffee is still used in many languages but in Armenian it is either called հայկական սուրճ, haykakan surč, 'Armenian coffee', or սեւ սուրճ, sev surč, 'black coffee', referring to the traditional preparation done without milk or creamer. If unsweetened it is called 'bitter' (դառը, daruh) in Armenia, but more commonly it is brewed with a little sugar (normal). Armenians will sometimes serve a plate of baklava, gata, or nazook alongside the coffee.

Czech Republic, Slovakia, Poland and Lithuania

A beverage called turecká káva or turek is very popular in the Czech Republic and Slovakia, although other forms of coffee preparation such as espresso have become more popular in the last few decades, decreasing the popularity of turek. Turek is usually no longer served in cafés, but it is prepared in pubs and kiosks, and in homes. The Czech and Slovak form of Turkish coffee is different from Turkish coffee in Turkey, the Arab world or Balkan countries, since a cezve is not used; instead the desired amount of ground coffee is put in a cup and boiling or almost boiling water is poured over it. In recent years, Turkish coffee is also made in a cezve (džezva in Czech), but Turkish coffee usually means the method described above. Coffee is prepared in the same way in Poland and Lithuania.

Greece

In Greece, Turkish coffee was formerly referred to simply as 'Turkish' (τούρκικος). But political tensions with Turkey in the 1950s led to the political euphemism Greek coffee (ελληνικός καφές)," which became even more popular after the Turkish invasion of Cyprus in 1974: " Greek–Turkish relations at all levels became strained, 'Turkish coffee' became 'Greek coffee' by substitution of one Greek word for another while leaving the Arabic loan-word, for which there is no Greek equivalent, unchanged." There were even advertising campaigns promoting the name Greek coffee in the 1990s. The name for a coffee pot remains either a briki (μπρίκι) in mainland Greek or a tzisves (τζισβές) in Cypriot Greek.

Former Yugoslavia

Further information: Coffee culture in former Yugoslavia

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, Turkish coffee is also called Bosnian coffee (Bosnian: bosanska kahva), which is made slightly differently from its Turkish counterpart. A deviation from the Turkish preparation is that when the water reaches its boiling point, a small amount is saved aside for later, usually in a coffee cup. Then, the coffee is added to the pot (džezva), and the remaining water in the cup is added to the pot. Everything is put back on the heat source to reach its boiling point again, which only takes a couple of seconds since the coffee is already very hot. Coffee drinking in Bosnia is a traditional daily custom and plays an important role during social gatherings.

In Serbia, Slovenia, North Macedonia, Montenegro, and Croatia it is called 'Turkish coffee', 'domestic coffee' or simply 'coffee'. It is nearly identical to the Turkish version. In Serbia, Turkish coffee is also called српска кафа (srpska kafa), which means 'Serbian coffee'.

See also

Notes

- The robusta species originated further south, in the Congo Basin, but it was not adapted for human consumption until much later.