| Revision as of 08:19, 29 August 2007 editWetman (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers92,066 edits →Joint conquest of Muslim Syria (1259-1260): id-ed the pope← Previous edit | Revision as of 08:29, 29 August 2007 edit undoWetman (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers92,066 edits →Raids of the Knights Templars (1298-1302): id-ed La Roche-GuillaumeNext edit → | ||

| Line 104: | Line 104: | ||

| ==Raids of the Knights Templars (1298-1302)== | ==Raids of the Knights Templars (1298-1302)== | ||

| ] was a strong advocate of the collaboration with the Mongols, bu his efforts ultimately failed.]] | ] was a strong advocate of the collaboration with the Mongols, bu his efforts ultimately failed.]] | ||

| From around 1298, the ] and their leader ] strongly advocated collaboration with the Mongols and fought against the Mamluks. The plan was to coordinate actions between the ] ]s, the King of Cyprus, the ] of Cyprus and ] and the Mongols of the ] of ] (]). In 1298 or 1299, Jacques de Molay halted a Mamluk invasion with military force in Armenia possibly because of the loss of |

From around 1298, the ] and their leader ] strongly advocated collaboration with the Mongols and fought against the Mamluks. The plan was to coordinate actions between the ] ]s, the King of Cyprus, the ] of Cyprus and ] and the Mongols of the ] of ] (]). In 1298 or 1299, Jacques de Molay halted a Mamluk invasion with military force in Armenia possibly because of the loss of Roche-Guillaume in the ],<ref>Malcolm C. Barber, ''The New Knighthood: A History of the Order of the Temple'' (Cambridge University Press) 1995:79.</ref> the last Templar stronghold in Cilicia, to the Mamluks. | ||

| However, when the Mongol ] of Persia, ], defeated the Mamluks in the ] in December 1299, the Christian forces were not ready to take advantage of the situation. | However, when the Mongol ] of Persia, ], defeated the Mamluks in the ] in December 1299, the Christian forces were not ready to take advantage of the situation. | ||

Revision as of 08:29, 29 August 2007

The Franco-Mongol alliance existed during a period of the 13th century in which the Ilkhanate Mongols based in Persia allied with the Frankish kingdoms of the Holy Land and the countries of Western Europe in order to combat their common Muslim enemy in the Middle East. During that period, the Mongols had numerous exchanges of letters and embassies with European monarchs, leading to diplomatic and military alliances against the Muslim realm and in favor of Christianity. This difficult alliance, over considerable distances and large cultural differences, bore little fruit, and ended with victory of the Mamluks and the total eviction of the Franks from the Middle East by 1302.

Papal overtures (1245-1248)

The Mongol invasion of Europe subsided in 1242 with the death of the Great Khan Ögedei. In 1245, Pope Innocent IV issued bulls and sent an envoy in the person of John of Plano Carpini (accompanied by Benedict the Pole) to the "Emperor of the Tartars". The message asked the Mongol ruler to become a Christian and stop his aggression against Europe. The Khan Güyük replied abruptly in 1246, demanding the submission of the Pope.

In 1245 Innocent had sent another mission, through another route, led by Ascelin of Lombardia, also bearing letters. The mission met with the Mongol ruler Eljigidei near the Caspian Sea in 1247. The reply of Eljigidei was in accordance with that of Güyük, but it was accompanied by Mongolian envoys to Rome. They met with Innocent IV in 1248, who again appealed to the Mongols to stop their killing of Christians.

Joint conquest of Muslim Syria (1259-1260)

Full military collaboration would take place in 1259-1260 when the Franks under the ruler of Antioch Bohemond VI and his father-in-law Hetoum I allied with the Mongols under Hulagu. Hulagu was generally favourable to Christianity, and was himself the son of a Christian woman. The Mongols together with the Northern Franks of Antioch and the Armenian Christians conquered Muslim Syria, taking together the city of Aleppo, and later Damascus together with the Christian Mongol general Kitbuqa:

"The king of Armenia and the Prince of Antioch went to the military camp of the Tatars, and they all went off to take Damascus".

— Le Templier de Tyr

The Mongols insisted that a Greek patriarch be installed in Antioch, which resulted in a temporary excommunication for Bohemond.

The Franks of Acre also sent the Dominican David of Ashby to the court of Hulagu in 1260.

Following a new conflict in Turkestan, Hulagu had to stop the invasion before it reached Egypt, and he only left about 10,000 Mongol horsemen in Syria to occupy the conquered territory. The Mamluks counter-attacked and encircled the Mongols after the Franks of Acre made a passive alliance with them and allowed their troops to go through Christian territory unhampered. The Mongols were defeated at the Battle of Ain Jalut on September 3, 1260, and the Mamluk Baibars began to threaten Antioch, which (as a vassal of the Armenians) had supported the Mongols.

On April 10, 1262, Hulagu sent through John the Hungarian a new letter to the French king Louis IX from the city of Maragheh, offering again an alliance. The letter mentioned Hulagu's intention to capture Jerusalem for the benefit of the Pope, and asked for Louis to send a fleet against Egypt. Louis transmitted the letter to Pope Urban IV, who answered by asking for Hulagu's conversion to Christianity.

Bohemond VI was again present at the court of Hulagu in 1264, trying to obtain as much support as possible from Mongol rulers against the Mamluk progression. His presence is described by the Armemian saint Vartan:

"In 1264, l'Il-Khan had me called, as well as the vartabeds Sarkis (Serge) and Krikor (Gregory), and Avak, priest of Tiflis. We arrived at the place of this powerfull monarch at the beginning of the Tartar year, in July, period of the solen assembly of the kuriltai. Here were all the Princes, Kings and Sultans submitted by the Tartars, with wonderful presents. Among them, I saw Hetoum I, king of Armenia, David, king of Georgia, the Prince of Antioch (Bohemond VI), and a quantity of Sultans from Persia.

— Vartan, trad. Dulaurier.

Baibars finally took the city of Antioch in 1268, and all of northern Syria was quickly lost, leaving Bohemond with no estates except Tripoli. In 1271, Baibars sent a letter to Bohemond threatening him with total anihilation and taunted him for his former alliance with the Mongols:

"Our yellow flags have repelled your red flags, and the sound of the bells has been replaced by the call: "Allâh Akbar!" (...) Warn your walls and your churches that soon our siege machinery will deal with them, your knights that soon our swords will invite themselves in their homes (...) We will see then what use will be your alliance with Abagha"

— Letter from Baibars to Bohemond VI, 1271

Alliances during the Eighth and Ninth Crusades

Abagha (1234-1282), the son of Hulagu and Oroqina Khatun, a Mongol Christian, was the second Ilkhanate emperor in Persia, who reigned from 1265-1282.

During his reign, Abagha, a devout Buddhist, attempted to convert the Muslims and harassing them mercilessly by promoting Nestorian and Buddhist interests ahead of the Muslims. He sent embassies to Pope Gregory X and Edward I of England. During his harsh reign, many Muslims had attempted to assassinate Abaqa. In 1265, upon his succession, he received the hand of Maria Despina Palaiologina, the illegitimate daughter of Emperor Michael VIII Palaeologus, in marriage.

Diplomatic alliance from Pope Clement IV (1267)

The Mamluks were extending their conquests in Syria during the 1260s, putting the Syrian Franks in a difficult situation.

In 1267, Pope Clement IV and James I of Aragon sent an ambassador to the Mongol ruler Abaqa Khan in the person of Jayme Alaric de Perpignan. Jayme Alaric would return to Europe in 1269 with a Mongol embassy. In a letter dated 1267, and written from Viterbo, the Pope welcomes Abagha's proposal for an alliance and informs him of a Crusade in the near future:

"The kings of France and Navarre, taking to heart the situation in the Holy Land, and decorated with the Holy Cross, are readying themselves to attacks the enemies of the Cross. You wrote to us that you wished to join your father-in-law (the Greek emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos) to assist the Latins. We abundantly praise you for this, but we cannot tell you yet, before having asked to the rulers, what road they are planning to follow. We will transmit to them your advice, so as to enlighten their deliberations, and will inform your Magnificence, through a secure message, of what will have been decided."

— 1267 letter from Pope Clement IV to Abagha

On March 24, 1267, Louis IX had indeed expressed the intention to mount a new Crusade. When he left on July 1st, 1270, however, the Eighth Crusade went to Tunis in modern Tunisia instead of Syria, for reasons which even today are not well understood. Louis IX would die of illness there, his last words being "Jerusalem".

The Pope's promise was also followed by a small crusade by the Jiménez dynasty, which arrived in Acre in December 1269. At that time, Abagha had to face an invasion in Khorasan by fellow Mongols from Turkestan, and could only commit a small force on the Syrian frontier from October 1269, only capable of brandishing the threat of an invasion.

Prince Edward and his alliance with the Mongols (1269-1274)

In 1269, the English Prince Edward (the future Edward I) started on a Crusade of his own. The number of knights and retainers that accompanied Edward on the crusade was quite small, possibly around 230 knights, other sources stating 1,000. Many of the members of Edward's expedition were close friends and family including his wife Eleanor of Castile, his brother Edmund, and his first cousin Henry of Almain.

As soon as he arrived in Acre, he sent an embassy to the Mongol ruler of Persia Abagha, an enemy of the Muslims. The embassy was led by Reginald Rossel, Godefroi of Waus and John of Parker, and its mission was to obtain military support from the Mongols. In an answer dated September 4th, 1271, Abagha agreed for cooperation and asked at what date the concerted attack on the Mamluks should take place:

"The messengers that Sir Edward and the Christians had sent to the Tartars came back to Acre, and they did so well that they brought the Tartars with them"

— Eracles, p461.

The arrival of the additional forces of Hugh III of Cyprus further emboldened Edward, who engaged in a raid on the town of Ququn. At the end of October 1271, the Mongol troops requested by Edward arriveds in Syria and ravaged the land from Aleppo southward. Abagha, occupied by other conflicts in Turkestan could only send 10,000 Mongol horsemen under general Samagar from the occupation army in Seljuk Anatolia, plus auxiliary Seljukid troops, but they trigerred an exodus of Muslim populations (who remembered the previous campaigns of Kithuqa) as far south as Cairo.

When Baibars mounted a counter-offensive from Egypt on November 12th, the Mongols had already retreated beyond the Euphrates, but these unsettling events allowed Edward to negotiate a ten year peace treaty with the Mamluks. Upon hearing of the death of Henry III, Edward left the Holy Land and returned to England in 1274.

Overall, Edward's crusade was rather insignificant and only gave the city of Acre a reprieve of ten years. However, Edward's reputation was greatly enhanced by his participation in the crusade and he was hailed by some contemporary commentators as a new Richard the Lionheart. Furthermore, some historians believe Edward was inspired by the design of the castles he saw while on crusade and incorporated similar features into the castles he built to secure portions of Wales, such as Caernarfon Castle.

New Mongol attempt at invading Syria (1280-1281)

Following the death of Baibars and the ensuing disorganisation of the Muslim realm, the Mongols seized the opportunity and organized a new invasion of Syrian land. Their first raid were made in combination with raids by the Hospitaliers knights of Marquab. The Mongols sent envoys to Acre to request military support, informing the Franks that they were fielding 50,000 Mongol horsemen and 50,000 Mongol infantry.

"Abaga ordered the Tartars to occupy Syria, the land and the cities, and remit them to be guarded by the Christians."

— Monk Hayton, "Fleur des Histoires d'Orient", circa 1300

The new sultan Qalawun however managed to neutralize the threat of combined Frank-Mongol operations by offering the Franks a 10 year truce (which he would later breach), a truce they accepted. In September 1281, 50,000 Mongol troops, together with 30,000 Armenians, Georgians, Greeks, and non-Syrian Franks fought against Qalawun at the Second Battle of Homs, but they were repelled.

Arghun's proposals for a new crusade (1285-1291)

The new ruler Arghun, son of Abaqa, again sent an embassy and a letter to Pope Honorius IV in 1285, a Latin translation of which is preserved in the Vatican. It mentions the links to Christianity of Arghun's familly, and proposes a combined military conquest of Muslim lands:

"As the land of the Muslims, that is, Syria and Egypt, is placed between us and you, we will encircle and strangle ("estrengebimus") it. We will send our messengers to ask you to send an army to Egypt, so that us on one side, and you on the other, we can, with good warriors, take it over. Let us know through secure messengers when you would like this to happen. We will chase the Saracens, with the help of the Lord, the Pope, and the Great Khan."

— Extract from the 1285 letter from Arghun to Honorius IV, Vatican

Arghun sent a second embassy to European rulers in 1287, headed by the Nestorian Rabban Bar Sauma, with the objective of contracting a military alliance to fight the Muslims in the Middle East, and take the city of Jerusalem. Sauma returned in 1288 with positive letters from Pope Nicholas IV, Edward I of England, and Philip IV the Fair of France.. Philip seemingly responded positively to the request of the embassy:

"And the King Philip said: if it be indeed so that the Mongols, though they are not Christians, are going to fight against the Arabs for the capture of Jerusalem, it is meet especially for us that we should fight , and if our Lord willeth, go forth in full strength."

— "The Monks of Kublai Khan Emperor of China

Philip also gave the embassy numerous presents, and sent one of his noblemen, Gobert de Helleville, to accompany Bar Sauma back to Mongol lands:

"And he said unto us, "I will send with you one of the great Amirs whom I have here with me to give an answer to King Arghon"; and the king gave Rabban Sawma gifts and apparel of great price."

— "The Monks of Kublai Khan Emperor of China

Gobert de Helleville departed on February 2, 1288, with two clerics Robert de Senlis and Guillaume de Bruyères, as well as arbaletier Audin de Bourges. They joined Bar Sauma in Rome, and accompanied him to Persia.

King Edward also welcomed the embassy enthusiastically:

"King Edward rejoiced greatly, and he was especially glad when Rabban Sauma talked about the matter of Jerusalem. And he said "We the kings of these cities bear upon our bodies the sign of the Cross, and we have no subject of thought except this matter. And my mind is relieved on the subject about which I have been thinking, when I hear that King Arghun thinketh as I think""

— Account of the travels of Rabban Bar Sauma, Chap. VII.

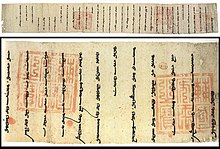

In 1289, Arghun sent a third mission to Europe, in the person of Buscarel of Gisolfe, a Genoese who had settled in Persia. The objective of the mission was to determine at what date concerted Christian and Mongol efforts could start. Arghun commited to march his troops as soon as the Crusaders had disambarked at Saint-Jean-d'Acre. Buscarel was in Rome between July 15th and September 30th 1289. He was in Paris in November-December 1289. He remitted a letter from Arghun to Philippe le Bel, answering to Philippe's own letter and promises, and fixing the date of the offensive from the winter of 1290 to spring of 1291:

"Under the power of the eternal sky, the message of the great king, Arghun, to the king of France..., said: I have accepted the word that you forwarded by the messengers under Saymer Sagura (Bar Sauma), saying that if the warriors of Il Khaan invade Egypt you would support them. We would also lend our support by going there at the end of the Tiger year’s winter , worshiping the sky, and settle in Damascus in the early spring .

If you send your warriors as promised and conquer Egypt, worshiping the sky, then I shall give you Jerusalem. If any of our warriors arrive later than arranged, all will be futile and no one will benefit. If you care to please give me your impressions, and I would also be very willing to accept any samples of French opulence that you care to burden your messengers with.

I send this to you by Myckeril and say: All will be known by the power of the sky and the greatness of kings. This letter was scribed on the sixth of the early summer in the year of the Ox at Ho’ndlon."

— Letter from Arghun to Philippe le Bel, 1289, France royal archives

Buscarel then went to England to bring Arghun's message to Edward I. He arrived in London January 5, 1290. Edward, whose answer has been preserved, answered enthusiastically to the project but remained evasive and failed to make a clear commitment.

Arghun then sent a fourth mission to European courts in 1290, led by a certain Chagan or Khagan, who was accompanied by Buscarel of Gisolfe and a Christian named Sabadin.

All these attempts to mount a combined offensive failed. On March 1291, Saint-Jean-d'Acre was conquered by the Mamluks in the Siege of Acre, and furthermore Arghun died on March 10th.

Raids of the Knights Templars (1298-1302)

From around 1298, the Knights Templar and their leader Jacques de Molay strongly advocated collaboration with the Mongols and fought against the Mamluks. The plan was to coordinate actions between the Christian military orders, the King of Cyprus, the aristocracy of Cyprus and Little Armenia and the Mongols of the khanate of Ilkhan (Persia). In 1298 or 1299, Jacques de Molay halted a Mamluk invasion with military force in Armenia possibly because of the loss of Roche-Guillaume in the Belen pass, the last Templar stronghold in Cilicia, to the Mamluks.

However, when the Mongol khan of Persia, Ghâzân, defeated the Mamluks in the Battle of Wadi al-Khazandar in December 1299, the Christian forces were not ready to take advantage of the situation.

In 1300, Jacques de Molay made his order commit raids along the Egyptian and Syrian coasts to weaken the enemy's supply lines as well as to harass them, and in November that year he joined the occupation of the tiny fortress island of Ruad (today called Arwad) which faced the Syrian town of Tortosa. The intent was to establish a bridgehead in accordance with the Mongol alliance, but the Mongols failed to appear in 1300. The same happened in 1301 and 1302. News circulated in Europe that the Mongols had finally conquered the Holy Land and Jerusalem in 1300, and handed it over to the Christians, but this apparently did not happen.

In 1301 Ghazan sent an embassy to the Pope, and in 1303 to Edward I, in the person of Buscarello de Ghizolfi, reinterating Hulagu's promise that they would give Jerusalem to the Franks in exchange for help against the Mamluks.

In September 1302 the Templars were driven out of Ruad by the attacking Mamluk forces from Egypt, and many were massacred when trapped on the island. The island of Ruad was lost, and when Ghâzân died in 1304 dreams of a rapid reconquest of the Holy Land were destroyed.

Oljeitu and the failed Crusade project (1305-1313)

Oljeitu, also named Mohammad Khodabandeh, was the great-grandson of the Ilkhanate founder Hulagu, and brother and successor of Mahmud Ghazan. His Christian mother baptized him as a Christian and gave him the name Nicholas . In his youth he at first converted to Buddhism and then to Sunni Islam together with his brother Ghazan. He then changed his first name to the Islamic name Muhammad.

In April 1305, Oljeitu sent letters the French king Philip the Fair, the Pope, and Edward I of England. After his predecessor Arghun, he offered a military collaboration between the Christian nations of Europe and the Mongols against the Mamluks. He also explained that internal conflicts between the Mongols were over:

"Now all of us, Timur Khagan, Tchapar, Toctoga, Togba and ourselves, main descendants of Gengis-Khan, all of us, descendants and brothers, are reconciled through the inspiration and the help of God. So that, from Nangkiyan (China) in the Orient, to Lake Dala our people is united and the roads are open."

— Extract from the letter of Oljeitu to Philip the Fair. French national archives.

European nations accordingly prepared a crusade, but were delayed. In the meantime Oljeitu launched a last campaign against the Mamluks (1312-13), in which he was unsuccessful. A settlement with the Mamluks would only be found when Oljeitu's son signed the Treaty of Aleppo with the Mamluks in 1322.

Last contacts (1322)

In 1320, the Egyptian sultan Naser Mohammed ibn Kelaoun invaded and ravaged Christian Armenian Cilicia. In a letter dated July 1st, 1322, Pope John XXII sent a letter from Avignon to the Mongol ruler Abu Sa'id, reminding him of the alliance of his ancestors with Christians, asking him to intervene in Cilicia. At the same time he advocated that he abandon Islam in favor of Christianity. Mongol troops were sent to Cilicia, but only arrived after a ceasefire had been negotiated for 15 years between Constantin, patriarch of the Armenians, and the sultan of Egypt. After Abu Sa'id, relations between Christian princes and the Mongols were totally abandoned.

He died without heir and successor. The state lost its status after his death, becoming a plethora of little kingdoms run by Mongols, Turks, and Persians.

Technology exchanges

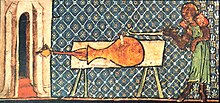

In these invasions westward, the Mongols brought with them a variety of eastern, often Chinese technologies, which may have been transmitted to the West on these occasions. The original weaknesses of the Mongols in siege warfare (they were essentially a nation of horsemen) were compensated by the introduction of Chinese engineering corps within their army.

One theory of how gunpowder came to Europe is that it made its way along the Silk Road through the Middle East; another is that it was brought to Europe during the Mongol invasion in the first half of the 13th century. Direct Franco-Mongol contacts occured as in the 1259-1260 military alliance of the Franks knights of the ruler of Antioch Bohemond VI and his father-in-law Hetoum I with the Mongols under Hulagu. William of Rubruck, an ambassador to the Mongols in 1254-1255, a personal friend of Roger Bacon, is also often designated as a possible intermediary in the transmission of gunpowder know-how between the East and the West.

Other innovations, such as printing, may have transited through the Mongol routes during that period.

See also: History of gunpowder See also: History of printingReligious affinity

The Mongols had been prozelitised by Christian Nestorians since about the 6th century and many of them were Christians. It seems that Nestorians communities in Central Asia hoped for such an alliance between the Mongols and Western Christianity. Overall, Mongols were highly tolerant of most religions, and typically sponsored several at the same time.

On the other hands, the Mongols had been in conflict with the Muslims for a long time since the Muslims advanced in eastern Central Asia in the 8th century (Battle of Talas), possibly explaining their partiality against them.

Notes

- David Wilkinson, Studying the History of Intercivilizational Dialogues

- David Wilkinson, Studying the History of Intercivilizational Dialogues

- "Histoire des Croisades", René Grousset, p581, ISBN 226202569X

- "Histoire des Croisades III", Rene Grousset, p581

- Quoted in "Histoire des Croisades III", Rene Grousset, p586

- Online Reference Book for Medieval syudies

- Encyclopedia Iranica article

- Encyclopedia Iranica article

- "Grousset, p565

- Quoted in Grosset, p.565

- Quoted in Grousset, p.650

- Quoted in Grousset, p.644

- Grousset, p.647

- "Histoire des Croisades III", Rene Grousset, p.656

- "Histoire des Croisades III", Rene Grousset, p.653. Grousset quote a contemporary source ("Eracles", p.461) explaining that Edward contacted the Mongols "por querre secors" ("To ask for help")

- Quoted in "Histoire des Croisades III", Rene Grousset, p.653.

- "Histoire des Croisades III", Rene Grousset, p.653.

- Grousset, p.687

- Quoted in Grousset, p.689

- Quote in "Histoires des Croisades III", Rene Grousset, p700

- Boyle, in Camb. Hist. Iran V, pp. 370-71; Budge, pp. 165-97. Source

- http://www.aina.org/books/mokk/mokk.htm

- http://www.aina.org/books/mokk/mokk.htm

- "Histoires des Croisades III", Rene Grousset, quoting "La Flor des Estoires d'Orient" by Haiton

- "The Monks of Kublai Khan Emperor of China", Sir E. A. Wallis Budge Source

- Source

- "Histoire des Croisades III", Rene Grousset.

- Malcolm C. Barber, The New Knighthood: A History of the Order of the Temple (Cambridge University Press) 1995:79.

- "Gesta Dei per Mongolos 1300. The Genesis of a Non-Event" Sylvia Schein, The English Historical Review, Vol. 94, No. 373 (Oct., 1979), p. 805, Source

- Encyclopedia Iranica article

- Mostaert and Cleaves, pp. 56-57, Source

- Source

- Source

- "Atlas des Croisades", p.112

- Norris 2003:11 harvcolnb error: no target: CITEREFNorris2003 (help)

- Chase 2003:58 harvcolnb error: no target: CITEREFChase2003 (help)

- "Histoire des Croisades", René Grousset, p581, ISBN 226202569X

- "The Eastern Origins of Western Civilization", John M.Hobson, p186, ISBN 0521547245

- Foltz "Religions of the Silk Road"

References

- "Histoire des Croisades III, 1188-1291", Rene Grousset, editions Perrin, ISBN 226202569

- "Atlas des Croisades", Jonathan Riley-Smith, Editions Autrement, ISBN 2862605530

- Encyclopedia Iranica, Article on Franco-Persian relations

- "The Monks of Kublai Khan Emperor of China", Sir E. A. Wallis Budge. Online

- "The history and Life of Rabban Bar Sauma", translated from the Syriac by Sir E. A. Wallis Budge Online

- Foltz, Richard (2000). "Religions of the Silk Road : overland trade and cultural exchange from antiquity to the fifteenth century". New York: St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 0-312-23338-8.