| Revision as of 20:03, 16 November 2007 editDirector (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers58,714 editsm reverted IP user udiscussed edits (vandalism)← Previous edit | Revision as of 09:40, 17 November 2007 edit undo151.67.87.93 (talk) pitchku materNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| The expression '''Istrian exodus''' or '''Istrian-Dalmatian exodus''' is used to indicate the ] of ethnic ] from ], ] |

The expression '''Istrian exodus''' or '''Istrian-Dalmatian exodus''' is used to indicate the ] of ethnic ] from ], ]-] and Dalmatian ]-Zara lands, who were under Italian rule since ] according to the ] and were assigned to ] by the ] of ] ].<br /> | ||

| Different sources give figures ranging from 200,000 to 350,000 ethnic Italians who left the areas in the aftermath of the conflict. | Different sources give figures ranging from 200,000 to 350,000 ethnic Italians who left the areas in the aftermath of the conflict. | ||

| == History |

== History == | ||

| ===Antecedents=== | |||

| {{main|Istria}} | {{main|Istria}} | ||

| {{NPOV-section}} | |||

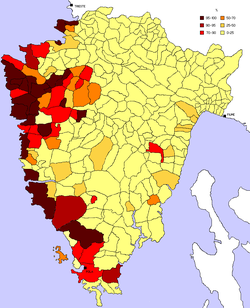

| ]}} {{legend|#ddc758|]}} {{legend|#b59b13|]}} {{legend|#ab9a55|]}}]] | ]}} {{legend|#ddc758|]}} {{legend|#b59b13|]}} {{legend|#ab9a55|]}}]] | ||

| ⚫ | Italian had been the main language of culture and administration in Istria and ] since the fourteenth and fifteenth century and in ] since the 1850s{{Facts|date=September 2007}}. Nevertheless, the native Italian-speaking population represented a minority{{Facts|date=September 2007}} of the population in all three areas; while the towns on the western coast of Istria were almost exlusively Italian-speaking, Fiume and most Dalmatian towns had a linguistically and ethnically mixed populations, as had the towns in central and eastern Istria. On the other hand, ] (] and ] dialects) were spoken in the countryside, with very few exceptions of Italian-speaking peasantry (the areas around of ] and ] in western Istria are two examples of these). | ||

| ⚫ | Starting from the 1830s, the development of national movements among ] started to threaten the hegemonic position of Italian language in culture, education and administration. This process was swifter in Dalmatia, where it accelerated from 1860's onward, as the gradual ] of the ] allowed the Serbo-Croatian speaking majority in Dalmatia to reduce the use of the Italian language to the few areas in which it was predominant (such as the region's capital, Zara{{Facts|date=September 2007}}, and some minor islands). In Istria, the Italian-speaking population actually grew during this time, both in number and proportion: the Italians, although representing a minority of the province's population (around 37% in 1910), maintained political control over the regional administration, but tension with the Slav (] and ]) representatives grew. Besides, Italians frequently accused the central Austro-Hungarian government of favouring Slovenes and Croatians over Italians. This was true to some extent: both in Istria and Dalmatia, Slav civil servants outnumbered the Italian ones. The de-centralized system of government in Austria-Hungary, however, left most of the policy issues to the provinces themselves, with the electoral system on the local level being clearly favourable to the Italian-speaking minority: only in Dalmatia did the Slav majority gain control over the provincial assembly. In Istria, Italian remained the language of education in all high schools (which were under the central government's jurisdiction), and in the majority of elementary schools; in the administration and the judiciary, the Slovenian and Serbo-Croatian languages continued to spread. <ref>Darko Darovec, A Brief History of Istria, Archivio del Litorale Adriatico, 1998, ISBN 0-9585774-0-4</ref> | ||

| ⚫ | In Fiume, which was under direct ] control, Italian language advanced; in 1910, the Italian-speaking population reached 50% of the inhabitants{{Facts|date=September 2007}} (not counting the predominantly Croatian industrial suburb of ]). | ||

| ⚫ | After World War I, the ], including all of Istria and Fiume, was annexed to Italy. After the rise of ] to power, the Italian state engaged in a policy of ] of Slav citizens in Istria and the violent repression of Slav political movements. After the complete forced dissolution of all Slav political, cultural and economic organizations in 1927, armed resistance was organized against Italian rule (see ]), followed by new repression, which further embittered the relations between the two communities. | ||

| ⚫ | Italian had been the |

||

| ⚫ | Starting from the |

||

| ⚫ | In |

||

| ⚫ | In 1941 the ] ]. Italy proceeded to annex large areas of ] (including its capital ]) and ] (including most of coastal ]). Its brutal repression of partisan activities and the imprisonment of thousands of Yugoslav civilians in concentration camps (with many dying, mostly after September 1943, in places like Arbe-Rab island concentration camp) in the newly-annexed provinces and in Italy proper fed the anti-Italian sentiments of the Slovenian and Croatian subjects of Fascist Italy. | ||

| ⚫ | After World War I, the ], including all of Istria and |

||

| ⚫ | During ], Slovenian and Croatian communist ] spread into the zone; the civil population was thus caught in the conflict. | ||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | ===Events of 1943=== | ||

| ⚫ | During ], Slovenian and Croatian |

||

| ⚫ | When the Fascist regime collapsed in July 1943 followed soon after by Italy's surrender to the allies in ] ] unleashed pent-up ethnic hatred against all things Italian. The first summary killings of Italians, done by the ]'s troops, happened during these days of September 1943. That was short-lived because the ethnically mixed areas of north-eastern Italy were quickly taken over by Nazi Germany. | ||

| ⚫ | === |

||

| ⚫ | After the dissolution of Italian fascist power in 1943, many individuals of Italian origin were killed (some by lynching) by the local Slav population in retaliation. Around 200 Italians were killed by ]'s Communist resistance in September 1943; most of them had been connected to the fascist regime in a way or another (some were simple civil servants), while others were victims of personal hatred or the attempt of the Communist resistance to get rid of its real or supposed enemies and destroy the bourgeoisie. All these events took place in central and eastern Istria. | ||

| ⚫ | When the Fascist regime collapsed in July 1943 followed soon after by Italy's surrender to the allies in September 1943 unleashed pent-up ethnic hatred against all things Italian. The first summary killings of Italians happened during these days of September 1943. That was short-lived because the ethnically mixed areas of north-eastern Italy were quickly taken over by Nazi Germany. | ||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ⚫ | After the dissolution of Italian fascist power in 1943, |

||

| ⚫ | ===The foibe massacres=== | ||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ⚫ | === |

||

| {{main|foibe massacres}} | {{main|foibe massacres}} | ||

| ⚫ | The second wave of anti-Italian violence took place after the liberation from ] occupation in May 1945. This was properly known as the ]. | ||

| Many Italian sources claim that these killings were tantamount to ]. Indeed, a significant part of the Slavic population had a very negative attitude towards Italians stereotyped as Fascist oppressors (partly rooted in the harsh conditions imposed upon them by the ]), so ethnic tensions could have played some role as far as individual motivations are concerned. However, it must be noticed that the Communist regime was based on what it has been called "the monopoly of terror", so all violent actions were carried through a plan of intimidation. The goal was to get rid of those who might have opposed the annexation of this areas to Yugoslavia, and of those who opposed (or presumably opposed) the newly established Communist regime. | |||

| ⚫ | The second wave of anti-Italian violence took place after the liberation from ] occupation in May 1945. This was known as the ]. | ||

| Many Italian sources claim that these killings were tantamount to ]. The problem with that interpretation is the relatively small number of casualties. However, a significant part of the Italian population had a very negative attitude towards Yugoslavs, stereotyped as rural barbarians, while the Slavs considered the Italians fascist oppressors (this belief was firmly rooted by the harsh conditions imposed upon them by the ]), so ethnic tensions could have played some role as far as individual motivations are concerned. | |||

| The mixed Italian-Slovenian Historical Commission, established in 1995 by the two governments to investigate the matters, succinctly described the circumstances of the 1945 killings: | The mixed Italian-Slovenian Historical Commission, established in 1995 by the two governments to investigate the matters, succinctly described the circumstances of the 1945 killings: | ||

| {{cquote|''14. These events were triggered by the atmosphere of settling accounts with the fascist violence; but, as it seems, they mostly proceeded from a preliminary plan which included several tendencies: endeavours to remove persons and structures who were in one way or another (regardless of their personal responsibility) linked with Fascism, with the Nazi supremacy, with collaboration and with the Italian state, and endeavours to carry out preventive cleansing of real, potential or only alleged opponents of the communist regime, and the annexation of ] to the new |

{{cquote|''14. These events were triggered by the atmosphere of settling accounts with the fascist violence; but, as it seems, they mostly proceeded from a preliminary plan which included several tendencies: endeavours to remove persons and structures who were in one way or another (regardless of their personal responsibility) linked with Fascism, with the Nazi supremacy, with collaboration and with the Italian state, and endeavours to carry out preventive cleansing of real, potential or only alleged opponents of the communist regime, and the annexation of ] to the new Yugoslavia. The initial impulse was instigated by the revolutionary movement which was changed into a political regime, and transformed the charge of national and ideological intolerance between the partisans into violence at the national level''.}} | ||

| ⚫ | The number of victims is not certain. The Italian historian Raoul Pupo suggests |

||

| Similar incidents took place in Dalmatia, particularly in Zara. | |||

| ===Connection between World War II killings and the exodus=== | |||

| ⚫ | The number of victims is not certain. The Italian historian ] suggests about 5.000 were killed, including the events of 1943, mostly Italians, but also Serbs, Slovenes and Croats who opposed the communist regime; others disagree and suggest much higher figures: up to 15.000 dead. | ||

| ⚫ | |||

| ==The exodus== | ==The exodus== | ||

| Fear of further retaliation, economic insecurity and the international political context that eventually led to the ] resulted in approximately 250,000-350,000 people, mostly Italians, leaving the region. The ''London Memorandum'' of 1954 gave to the ethnic Italians the choice of either opting to leave (the so-called ''optants'') or staying. These exiles were to be given compensation for their loss of property and other indemnity by the Italian State under the terms of the peace treaties. | |||

| Some famous postwar exiles from territories include actresses ] and ], race driver ], singer ], boxer ], tennis player ], stylist ]. Following the exodus, the areas were settled with Yugoslav people. | Some famous postwar exiles from territories include actresses ] and ], race driver ], singer ], boxer ], tennis player ], stylist ] and chef ]. Following the exodus, the areas were settled with Yugoslav people. | ||

| Foibe massacres and exodus were declared a ] and an ethnic-political cleansing by Italian president ]. | |||

| ===Periods of exodus=== | |||

| Exodus was from 1943 to 1960 and principal years in connection with periods were: | |||

| *1943 | |||

| *1945 | |||

| *1947 | |||

| *1954 | |||

| First period was soon after surrender of ] and beginning of carnage in foibe. | |||

| The second period was soon after the end of the war and saw an escalation of slaughter in the foibe against Italian civilians, the ]'s soldiers and their Slavic collaborating allies: the ], the ] and ]. The main motives for the mass killings seems to have been a plan of ethnic cleansing and ],<ref>{{cite web | author=Paolo Sardos Albertini | title="Terrore" comunista e le foibe | date=2002-05-08 | work=Il Piccolo | url=http://www.leganazionale.it/storia/foibeterrorecomunista.htm | accessdate=2006-06-08 | language=Italian}}</ref> that is to say, elimination of potential enemies of the communist Yugoslav rule, including members of German and Italian fascist units, Italian officers and ], parts of the Italian ] who opposed both communism and fascism and even Serb, Slovenian and Croatian ]. | |||

| The third period was soon after the peace treaty, when Istria was assigned to the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, except for a small area in the northwest part that formed the independent ]. | |||

| The fourth period was soon after a ] in ]. It gave a provisional civil administration of Zone A, with Trieste, to Italy and Zone B to Yugoslavia: in 1975 the ] definitively divided the former Free Territory of Trieste. | |||

| ===Estimates of exodus=== | ===Estimates of exodus=== | ||

| ⚫ | Estimates of the exodus studied by some important historians: | ||

| ⚫ | *] (Croat), 191.421 Italian exiles from alone territory actually in Croatia | ||

| ⚫ | *] (Slovene), 40.000 Italian exiles from alone territory actually in Slovenia and 3.000 Slovene anticommunist exiles | ||

| ⚫ | *] (Italian), about 250.000 Italian exiles | ||

| ⚫ | *] (Italian), about 350.000 Italian exiles. | ||

| ⚫ | The mixed Italian-Slovenian Historical Commission verified 27.000 Italian exiles from alone territory actually in Slovenia and 3.000 Slovene anticommunist exiles. | ||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | *] (Croat), 191 |

||

| ⚫ | *] (Slovene), 40 |

||

| ⚫ | *] (Italian), about 250 |

||

| ⚫ | *] (Italian), about 350 |

||

| ===Reparation=== | |||

| ⚫ | The mixed Italian-Slovenian Historical Commission verified 27 |

||

| ⚫ | On ], ] Yugoslavia and Italy signed a treaty in ] where Yugoslavia agreed to pay US$110 million for the compensation of the exiles' property which was confiscated after the war. Up to its breakup in 1991, Yugoslavia had paid US$18 million. ] and ], two Yugoslav ], agreed to share the remainder of this debt. Slovenia assumed 62% and Croatia the remaining 38%. Italy did not want to reveal the bank account number so in 1994 Slovenia opened a fiduciary account at Dresdner Bank in ], informed Italy about it and started paying its US$55,976,930 share. The last payment was due in January 2002. Until today, the solution of the matter between Croatia and Italy has been delayed. | ||

| ===Property reparation=== | |||

| ===Denial of exodus=== | |||

| ⚫ | A point of view in connection with ] of Istrian exodus or diaspora, both terms are used to refer to any people or ethnic population who are forced or induced to leave their traditional ], exists and is supported by some Slav and Italian historians who assert that was not ethnic cleansing planned by Josip Broz and Slav communists against Italians because the problem with that interpretation is the relatively small number of casualties. These historians affirm that connection between the foibe massacres and the exodus is, however, a matter of much controversy. They assert even besides the fact that the unlikelyhood of Yugoslavia exterminating its Italian population was well known (there was even an Italian "Giuseppe Garibaldi" division among the Yugoslav Partisan forces), the bulk of the actual migration took place nine years later, in 1954: so the impact of the killings and lynching of Italian RSI fascists and supposed nationalists in 1945 (especially in the context of the huge casualties of the WW2 Yugoslav front), is somewhat questionable. | ||

| ⚫ | On ], ] Yugoslavia and Italy signed a treaty in ] where Yugoslavia agreed to pay US$110 million for the compensation of the exiles' property which was confiscated after the war. Up to its breakup in 1991, Yugoslavia had paid US$18 million. Slovenia and ], two Yugoslav ], agreed to share the remainder of this debt. Slovenia assumed 62% and Croatia the remaining 38%. Italy did not want to reveal the bank account number so in 1994 Slovenia opened a fiduciary account at Dresdner Bank in ], informed Italy about it and started paying its US$55,976,930 share. The last payment was due in January 2002. Until today, the solution of the matter between Croatia and Italy has been delayed. | ||

| ==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| {{reflist}} | |||

| <references/> | |||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| Line 75: | Line 88: | ||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| *] | *] | ||

| *] | |||

| *] | *] | ||

| *] | *] | ||

| *] | *] | ||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| *{{it icon}} {{en icon}} from Istria and Dalmatia. | *{{it icon}} {{en icon}} from Istria and Dalmatia. | ||

| Line 84: | Line 99: | ||

| *{{it icon}} | *{{it icon}} | ||

| *{{sl icon}} | *{{sl icon}} | ||

| ==Video== | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

Revision as of 09:40, 17 November 2007

The expression Istrian exodus or Istrian-Dalmatian exodus is used to indicate the diaspora of ethnic Italians from Istria, Rijeka-Fiume and Dalmatian Zadar-Zara lands, who were under Italian rule since World War I according to the Treaty of Rapallo, 1920 and were assigned to Yugoslavia by the Paris Peace Treaty of February 10 1947.

Different sources give figures ranging from 200,000 to 350,000 ethnic Italians who left the areas in the aftermath of the conflict.

History

Antecedents

Main article: Istria| The neutrality of this section is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please do not remove this message until conditions to do so are met. (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Italian had been the main language of culture and administration in Istria and Dalmatia since the fourteenth and fifteenth century and in Fiume since the 1850s. Nevertheless, the native Italian-speaking population represented a minority of the population in all three areas; while the towns on the western coast of Istria were almost exlusively Italian-speaking, Fiume and most Dalmatian towns had a linguistically and ethnically mixed populations, as had the towns in central and eastern Istria. On the other hand, Slavic languages (Slovenian and Croatian dialects) were spoken in the countryside, with very few exceptions of Italian-speaking peasantry (the areas around of Vodnjan and Buje in western Istria are two examples of these). Starting from the 1830s, the development of national movements among Slav-speaking populations started to threaten the hegemonic position of Italian language in culture, education and administration. This process was swifter in Dalmatia, where it accelerated from 1860's onward, as the gradual democratisation of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire allowed the Serbo-Croatian speaking majority in Dalmatia to reduce the use of the Italian language to the few areas in which it was predominant (such as the region's capital, Zara, and some minor islands). In Istria, the Italian-speaking population actually grew during this time, both in number and proportion: the Italians, although representing a minority of the province's population (around 37% in 1910), maintained political control over the regional administration, but tension with the Slav (Slovene and Croatian) representatives grew. Besides, Italians frequently accused the central Austro-Hungarian government of favouring Slovenes and Croatians over Italians. This was true to some extent: both in Istria and Dalmatia, Slav civil servants outnumbered the Italian ones. The de-centralized system of government in Austria-Hungary, however, left most of the policy issues to the provinces themselves, with the electoral system on the local level being clearly favourable to the Italian-speaking minority: only in Dalmatia did the Slav majority gain control over the provincial assembly. In Istria, Italian remained the language of education in all high schools (which were under the central government's jurisdiction), and in the majority of elementary schools; in the administration and the judiciary, the Slovenian and Serbo-Croatian languages continued to spread. In Fiume, which was under direct Hungarian control, Italian language advanced; in 1910, the Italian-speaking population reached 50% of the inhabitants (not counting the predominantly Croatian industrial suburb of Sušak).

After World War I, the Julian March, including all of Istria and Fiume, was annexed to Italy. After the rise of fascism to power, the Italian state engaged in a policy of Italianization of Slav citizens in Istria and the violent repression of Slav political movements. After the complete forced dissolution of all Slav political, cultural and economic organizations in 1927, armed resistance was organized against Italian rule (see TIGR), followed by new repression, which further embittered the relations between the two communities.

In 1941 the Axis Powers invaded Yugoslavia. Italy proceeded to annex large areas of Slovenia (including its capital Ljubljana) and Croatia (including most of coastal Dalmatia). Its brutal repression of partisan activities and the imprisonment of thousands of Yugoslav civilians in concentration camps (with many dying, mostly after September 1943, in places like Arbe-Rab island concentration camp) in the newly-annexed provinces and in Italy proper fed the anti-Italian sentiments of the Slovenian and Croatian subjects of Fascist Italy.

During World War II, Slovenian and Croatian communist guerrilla spread into the zone; the civil population was thus caught in the conflict.

Events of 1943

When the Fascist regime collapsed in July 1943 followed soon after by Italy's surrender to the allies in 8 September 1943 unleashed pent-up ethnic hatred against all things Italian. The first summary killings of Italians, done by the Tito's troops, happened during these days of September 1943. That was short-lived because the ethnically mixed areas of north-eastern Italy were quickly taken over by Nazi Germany.

After the dissolution of Italian fascist power in 1943, many individuals of Italian origin were killed (some by lynching) by the local Slav population in retaliation. Around 200 Italians were killed by Tito's Communist resistance in September 1943; most of them had been connected to the fascist regime in a way or another (some were simple civil servants), while others were victims of personal hatred or the attempt of the Communist resistance to get rid of its real or supposed enemies and destroy the bourgeoisie. All these events took place in central and eastern Istria.

The foibe massacres

Main article: foibe massacresThe second wave of anti-Italian violence took place after the liberation from Nazi occupation in May 1945. This was properly known as the foibe massacres.

Many Italian sources claim that these killings were tantamount to ethnic cleansing. Indeed, a significant part of the Slavic population had a very negative attitude towards Italians stereotyped as Fascist oppressors (partly rooted in the harsh conditions imposed upon them by the fascist regime), so ethnic tensions could have played some role as far as individual motivations are concerned. However, it must be noticed that the Communist regime was based on what it has been called "the monopoly of terror", so all violent actions were carried through a plan of intimidation. The goal was to get rid of those who might have opposed the annexation of this areas to Yugoslavia, and of those who opposed (or presumably opposed) the newly established Communist regime.

The mixed Italian-Slovenian Historical Commission, established in 1995 by the two governments to investigate the matters, succinctly described the circumstances of the 1945 killings:

14. These events were triggered by the atmosphere of settling accounts with the fascist violence; but, as it seems, they mostly proceeded from a preliminary plan which included several tendencies: endeavours to remove persons and structures who were in one way or another (regardless of their personal responsibility) linked with Fascism, with the Nazi supremacy, with collaboration and with the Italian state, and endeavours to carry out preventive cleansing of real, potential or only alleged opponents of the communist regime, and the annexation of Venezia Giulia to the new Yugoslavia. The initial impulse was instigated by the revolutionary movement which was changed into a political regime, and transformed the charge of national and ideological intolerance between the partisans into violence at the national level.

Similar incidents took place in Dalmatia, particularly in Zara.

The number of victims is not certain. The Italian historian Raoul Pupo suggests about 5.000 were killed, including the events of 1943, mostly Italians, but also Serbs, Slovenes and Croats who opposed the communist regime; others disagree and suggest much higher figures: up to 15.000 dead.

The exodus

Fear of further retaliation, economic insecurity and the international political context that eventually led to the Iron Curtain resulted in approximately 250,000-350,000 people, mostly Italians, leaving the region. The London Memorandum of 1954 gave to the ethnic Italians the choice of either opting to leave (the so-called optants) or staying. These exiles were to be given compensation for their loss of property and other indemnity by the Italian State under the terms of the peace treaties.

Some famous postwar exiles from territories include actresses Alida Valli and Laura Antonelli, race driver Mario Andretti, singer Sergio Endrigo, boxer Nino Benvenuti, tennis player Orlando Sirola, stylist Ottavio Missoni and chef Lidia Bastianich. Following the exodus, the areas were settled with Yugoslav people.

Foibe massacres and exodus were declared a democide and an ethnic-political cleansing by Italian president Giorgio Napolitano.

Periods of exodus

Exodus was from 1943 to 1960 and principal years in connection with periods were:

- 1943

- 1945

- 1947

- 1954

First period was soon after surrender of Italian army and beginning of carnage in foibe.

The second period was soon after the end of the war and saw an escalation of slaughter in the foibe against Italian civilians, the Italian Social Republic's soldiers and their Slavic collaborating allies: the Chetniks, the Ustaše and Domobranci. The main motives for the mass killings seems to have been a plan of ethnic cleansing and political cleansing, that is to say, elimination of potential enemies of the communist Yugoslav rule, including members of German and Italian fascist units, Italian officers and civil servants, parts of the Italian elite who opposed both communism and fascism and even Serb, Slovenian and Croatian anti-communists.

The third period was soon after the peace treaty, when Istria was assigned to the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, except for a small area in the northwest part that formed the independent Free Territory of Trieste.

The fourth period was soon after a Memorandum of Understanding in London. It gave a provisional civil administration of Zone A, with Trieste, to Italy and Zone B to Yugoslavia: in 1975 the Treaty of Osimo definitively divided the former Free Territory of Trieste.

Estimates of exodus

Estimates of the exodus studied by some important historians:

- Vladimir Žerjavić (Croat), 191.421 Italian exiles from alone territory actually in Croatia

- Nevenka Troha (Slovene), 40.000 Italian exiles from alone territory actually in Slovenia and 3.000 Slovene anticommunist exiles

- Raoul Pupo (Italian), about 250.000 Italian exiles

- Flaminio Rocchi (Italian), about 350.000 Italian exiles.

The mixed Italian-Slovenian Historical Commission verified 27.000 Italian exiles from alone territory actually in Slovenia and 3.000 Slovene anticommunist exiles.

Reparation

On February 18, 1983 Yugoslavia and Italy signed a treaty in Rome where Yugoslavia agreed to pay US$110 million for the compensation of the exiles' property which was confiscated after the war. Up to its breakup in 1991, Yugoslavia had paid US$18 million. Slovenia and Croatia, two Yugoslav successors, agreed to share the remainder of this debt. Slovenia assumed 62% and Croatia the remaining 38%. Italy did not want to reveal the bank account number so in 1994 Slovenia opened a fiduciary account at Dresdner Bank in Luxembourg, informed Italy about it and started paying its US$55,976,930 share. The last payment was due in January 2002. Until today, the solution of the matter between Croatia and Italy has been delayed.

Denial of exodus

A point of view in connection with denialism of Istrian exodus or diaspora, both terms are used to refer to any people or ethnic population who are forced or induced to leave their traditional homeland, exists and is supported by some Slav and Italian historians who assert that was not ethnic cleansing planned by Josip Broz and Slav communists against Italians because the problem with that interpretation is the relatively small number of casualties. These historians affirm that connection between the foibe massacres and the exodus is, however, a matter of much controversy. They assert even besides the fact that the unlikelyhood of Yugoslavia exterminating its Italian population was well known (there was even an Italian "Giuseppe Garibaldi" division among the Yugoslav Partisan forces), the bulk of the actual migration took place nine years later, in 1954: so the impact of the killings and lynching of Italian RSI fascists and supposed nationalists in 1945 (especially in the context of the huge casualties of the WW2 Yugoslav front), is somewhat questionable.

Notes

- Darko Darovec, A Brief History of Istria, Archivio del Litorale Adriatico, 1998, ISBN 0-9585774-0-4

- Paolo Sardos Albertini (2002-05-08). ""Terrore" comunista e le foibe". Il Piccolo (in Italian). Retrieved 2006-06-08.

References

- Raoul Pupo, Il lungo esodo. Istria: le persecuzioni, le foibe, l'esilio, Rizzoli, 2005, ISBN 88-17-00562-2.

- Raoul Pupo and Roberto Spazzali, Foibe, Mondadori, 2003, ISBN 8842490156 .

- Guido Rumici, Infoibati, Mursia, Milano, 2002, ISBN 88-425-2999-0.

- Arrigo Petacco, L'esodo. La tragedia negata degli italiani d'Istria, Dalmazia e Venezia Giulia, Mondadori, Milano, 1999.

See also

- Foibe massacres

- Italian Social Republic

- Partisans (Yugoslavia)

- Yugoslav People's Liberation War

- Ethnic cleansing

- Istria

- Dalmatia

External links

- Template:It icon Template:En icon Site of an association of Italian exiles from Istria and Dalmatia.

- Template:En icon Slovene-Italian Relations 1880-1956 Report 2000

- Template:It icon Relazioni Italo-Slovene 1880-1956 Relazione 2000

- Template:Sl icon Slovensko-italijanski odnosi 1880-1956 Poročilo 2000