| Revision as of 11:59, 26 November 2008 editLilHelpa (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers413,676 editsm →History: spelling: occured -> occurred← Previous edit | Revision as of 20:22, 26 November 2008 edit undoCommonsDelinker (talk | contribs)Bots, Template editors1,016,942 editsm Removing "Pobol.png", it has been deleted from Commons by Diti because: per commons:Commons:Deletion_requests/Image:Pobol.png.Next edit → | ||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

| {{Infobox Ethnic group | {{Infobox Ethnic group | ||

| |group = Welsh people | |group = Welsh people | ||

| |image = |

|image = | ||

| |image_caption = From top left:<br/>], ], ], ], ],<br/>].<br/>For further notable Welsh people, see:<br/>], ],<br/>], ]. | |image_caption = From top left:<br/>], ], ], ], ],<br/>].<br/>For further notable Welsh people, see:<br/>], ],<br/>], ]. | ||

| |population = About '''14 million''' Worldwide | |population = About '''14 million''' Worldwide | ||

Revision as of 20:22, 26 November 2008

This article is about the ethnic group and nation. For information about residents in Wales, see Demography of Wales. Ethnic group| Total population | |

|---|---|

| About 14 million Worldwide | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| estimated 3.6 million | |

| | 3 million |

| | 16,623 |

| | 609,711 |

| 1,959,794 | |

| 440,965 | |

| 9,966 | |

| 84,246 | |

| 20,000 | |

| Languages | |

| Welsh, English | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity , and other faiths. | |

The Welsh people (Welsh: Cymro ("Welshman"); Cymraes ("Welshwoman"); Cymry ("Welshmen/women"); Cymry cymraeg ("Welsh-speaking welshmen/women")) are an ethnic group and nation associated with Wales and the Welsh language. Authors John Davies and Gwyn A. Williams argue the origin of the "Welsh nation" can be traced to the late 4th and early 5th centuries, following the Roman withdrawal from Britain, although the origins of Celtic languages in Wales may date back far longer. As with all ethnic groups, the term Welsh people applies to people who identify themselves as Welsh, and who are identified by others as Welsh, they share a perceived common origin and a shared cultural heritage. In modern use in Wales, "Welsh people" may also refer to anyone born or living in Wales.

History

See also: History of Wales Further information: Genetic history of the British IslesDuring their time in Britain, the ancient Romans encountered tribes in present-day Wales that they called the Ordovices, the Demetae, the Silures and the Deceangli. Speaking Brythonic, a Celtic language, these tribes are traditionally thought to have arrived in Britain from the mainland parts of Europe over the preceding centuries. However, some archaeologists argue that there is no evidence for large-scale Iron Age migrations into Great Britain. The claim has also been made that Indo-European languages may have been introduced to the British Isles as early as the early Neolithic (or even earlier), with Goidelic and Brythonic languages developing indigenously. Others hold that the close similarity between the Goidelic and Brythonic branches, and their sharing of Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age terminology with their continental relatives, point to a more recent introduction of Indo-European languages, with Proto-Celtic itself unlikely to have existed prior than the end of the 2nd millennium BC at the earliest. The genetic evidence in this case would show that the change to Celtic languages in Britain may have occurred as a cultural shift rather than through migration as was previously supposed.

Current genetic research supports the idea that people living in the British Isles are likely mainly descended from the indigenous European Paleolithic (Old Stone Age hunter gatherers) population (about 80%), with a smaller Neolithic (New Stone Age farmers) input (about 20%). Paleolithic Europeans seem to have been a homogeneous population, possibly due to a population bottleneck (or near-extinction event) on the Iberian peninsula, where a small human population is thought to have survived the glaciation, and expanded into Europe during the Mesolithic. The assumed genetic imprint of Neolithic incomers is seen as a cline, with stronger Neolithic representation in the east of Europe and stronger Paleolithic representation in the west of Europe. Most in Wales today regard themselves as Celtic, claiming a heritage back to the Iron Age tribes, which themselves, based on modern genetic analysis, would appear to have had a predominantly Paleolithic and Neolithic indigenous ancestry. When the Roman legions departed Britain around 400, a Romano-British culture remained in the areas the Romans had settled, and the pre-Roman cultures in others.

In two recently published books, Blood of the Isles, by Brian Sykes and The Origins of the British, by Stephen Oppenheimer, both authors state that according to genetic evidence, most Welsh people and most Britons descend from the Iberian Peninsula, as a result of different migrations that took place during the Mesolithic and the Neolithic eras, and which laid the foundations for the present-day populations in the British Isles, indicating an ancient relationship among the populations of Atlantic Europe. According to Stephen Oppenheimer 96% of lineages in Llangefni in north Wales derive from Iberia. Genetic research on the Y-chromosome has shown that the Welsh, like the Irish are genetically very similar to the Basques of Northern Spain and South Western France although the Welsh do contain more Neolithic input than both the Irish and the Basques. Genetic marker R1b averages from 83-89% amongst the Welsh.

The people in what is now Wales continued to speak Brythonic languages with additions from Latin, as did some other Celts in areas of Great Britain. The surviving poem Y Gododdin is in early Welsh and refers to the Brythonic kingdom of Gododdin with a capital at Din Eidyn (Edinburgh) and extending from the area of Stirling to the Tyne. John Davies places the change from Brythonic to Welsh between 400 and 700. Offa's Dyke was erected in the mid-8th century, forming a barrier between Wales and Mercia.

The process whereby the indigenous population of 'Wales' came to think of themselves as Welsh is not clear. There is plenty of evidence of the use of the term Brythoniaid (Britons); by contrast, the earliest use of the word Kymry (referring not to the people but to the land—and possibly to northern Britain in addition to modern day territory of Wales) is found in a poem dated to about 633. The name of the region in northern England now known as Cumbria is believed to be derived from the same root. Only gradually did Cymru (the land) and Cymry (the people) come to supplant Brython. Although the Welsh language was certainly used at the time, Gwyn A. Williams argues that even at the time of the erection of Offa's Dyke, the people to its west saw themselves as Roman, citing the number of Latin inscriptions still being made into the 8th century. However, it is unclear whether such inscriptions reveal a general or normative use of Latin as a marker of identity or its selective use by the early Christian Church.

The word Cymry is believed to be derived from the Brythonic combrogi, meaning fellow-countrymen, and thus Cymru carries a sense of "land of fellow-countrymen", "our country"- and, of course, notions of fraternity. The name "Wales", however, comes from a Germanic walha meaning "stranger" or "foreigner".

There are two words in modern Welsh for the English and this reflects the idea held by some that the modern English derive from various Germanic tribes (although there is little evidence for the extinction of the pre-Germanic inhabitants of England, and the idea ignores both the Scandinavian settlers in England and the Roman and Norman-French influences on English language, culture and identity): Saeson (singular: Sais), meaning originally Saxon; and: Eingl, denoting:-Angles,; meaning Englishmen in modern Welsh. The Welsh word for the English language is Saesneg, while the Welsh word for England is Lloegr.

There was immigration to Wales after the Norman Conquest, several Normans encouraged immigration to their new lands; the Landsker Line dividing the Pembrokeshire "Englishry" and "Welshry" is still detectable today. The terms Englishry and Welshry are used similarly about Gower.

The population of Wales increased from 587,128 in 1801 to 1,162,139 in 1851 and had reached 2,420,921 by 1911. Part of this increase can be attributed to the demographic transition seen in most industrialising countries during the Industrial Revolution, as death-rates dropped and birth-rates remained steady. However, there was also a large-scale migration of people into Wales during the industrial revolution. The English were the most numerous group, but there were also considerable numbers of Irish and smaller numbers of many other ethnic groups. For example, some Italians migrated to South Wales. Wales received other immigration from various parts of the British Commonwealth of Nations in the 20th century, and African-Caribbean and Asian communities add to the ethno-cultural mix, particularly in urban Wales. Recently, parts of Wales have seen an increased number of immigrants from recent EU accession countries such as Poland.

21st century identity

2001 Census Controversy

It is uncertain how many people in Wales consider themselves to be of Welsh ethnicity, because the 2001 UK census did not offer 'Welsh' as an option; respondents had to use a box marked "Other". 95% of the population of Wales thus described themselves as being of British ethnicity. Controversy surrounding the method of determining ethnicity began as early as 2000, when it was revealed that respondents in Scotland and Northern Ireland would be able to check a box describing themselves as of Scottish or of Irish ethnicity, an option not available for Welsh or English respondents. Prior to the Census, Plaid Cymru backed a petition calling for the inclusion of a Welsh tick-box and for the National Assembly to have primary law-making powers and its own National Statistics Office.

With an absence of a Welsh tick-box, the only other tick-box available was 'white-British,' 'Irish', or 'other'. The Scottish parliament insisted that a Scottish ethnicity tick-box be included in the census in Scotland, and with this inclusion as many as 88.11% claimed Scottish ethnicity. Critics expected a higher proportion of respondents describing themselves as of Welsh ethnicity, similar to Scottish results, had a Welsh tickbox been made available. Additional criticism was leveled at the timing of the census, which was taken in the middle of the Foot and Mouth crisis of 2001, a fact organizers said did not impact the results. However, the Foot and Mouth crisis did delay UK General Elections, the first time since the Second World War any event postponed an election.

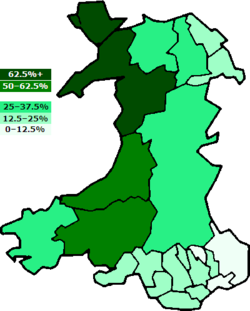

In the census, as many as 14 per cent of the population took the 'extra step' to write in that they were of Welsh ethnicity. Of these, Gwynedd recorded the highest percentage of those identifying as of Welsh ethnicity (at 27%), followed by Carmarthenshire (23 per cent), Ceredigion (22 per cent) and the Isle of Anglesey (19 per cent). For respondants between 16 and 74 years of age, those claiming Welsh ethnicity were predominatly in professional and managerial occupations.

Surveys

According to the 2001/02 Labour Force Survey, 87 per cent of Wales-born residents claimed Welsh ethnic identity. Respondents in the local authority areas of Gwynedd, Ceredigion, Carmarthenshire, and Merthyr Tydfil each returned results of between 91 and 93 per cent claiming Welsh ethnicity, of those born in Wales. Neath Port Talbot, Bridgend, Rhondda Cynon Taff, returned results 88-91 per cent of Wales-born respondents claiming Welsh ethnicity. Powys, Anglesey, Denbighshire, Caerphilly, and the Vale of Glamorgan returned results of 86-88 per cent of respondents born in Wales claiming Welsh ethnicity. Pembrokeshire, Swansea, Cardiff, Newport, Torfaen, Blaenau Gwent, Conwy, Flintshire, and Wrexham returned results of 78-86 per cent of those born in Wales claiming Welsh ethnicity.

According to the survey, when factoring non-Wales born residents, 67 per cent of those surveyed claimed Welsh or Welsh-British (rather than British, English or other) ethnic identity. This reflects a residential population which includes 30 per cent born outside of Wales. The survey, from the Office for National Statistics, identified the remaining 33 per cent of respondents as 'Not Welsh'.

Culture

See also: Culture of WalesLanguage

Main article: Welsh languagesee also History of the Welsh language

According to the 2001 (two thousand and one) census the number of Welsh speakers in Wales increased for the first time in 100 years, with 20.5% in a population of over 2.9 million claiming fluency in Welsh, or one in five. Additionally, 28% of the population of Wales claimed to understand Welsh. The census revealed that the increase was most significant in urban areas; such as Cardiff (Caerdydd) with an increase from 6.6% in 1991 to 10.9% in 2001, and Rhondda Cynon Taff with an increase from 9% in 1991 to 12.3% in 2001. However, the number of Welsh speakers declined in Gwynedd from 72.1% in 1991 to 68.7%, and in Ceredigion from 59.1% in 1991 to 51.8%. Ceredigion in particular experienced the greatest fluctuation with the a 19.5% influx of new residents since 1991.

The decline in Welsh speakers in much of rural Wales is attributable to non Welsh speaking residents moving to North Wales, driving up property rates above what locals may afford, according to former Gwynedd county councilor Seimon Glyn of Plaid Cymru, whose controversial comments in 2001 focused attention on the issue. As many as a third of all properties in Gwynedd are bought by persons from out of the country. The issue of locals being priced out of the local housing market is common to many rural communities throughout Britain, but in Wales the added dimension of language further complicated the issue, as many new residents did not learn the Welsh language.

A Plaid Cymru taskforce headed by Dafydd Wigley recommended land should be allocated for affordable local housing, and called for grants for locals to buy houses, and recommended council tax on holiday homes should double.

However, the same census shows that 25 percent of residents were born outside Wales. The number of Welsh speakers in other places in Britain is uncertain, but numbers are high in the main cities and there are speakers along the Welsh-English border.

Even among the Welsh speakers, very few people speak only Welsh, with nearly all being bilingual in English. However, a large number of Welsh speakers are more comfortable expressing themselves in Welsh than in English and vice versa, usually depending on the area spoken. Many prefer to speak English in South Wales or the urbanised areas and Welsh in the North or in rural areas. A speaker's choice of language can vary according to the subject domain (known in linguistics as code-switching).

Thanks to the work of the Mudiad Ysgolion Meithrin (Welsh Nursery School Movement), recent census data reveals a reversal in decades of linguistic decline: there are now more Welsh speakers under five years of age than over 60. For many young people in Wales, the acquisition of Welsh is a gateway to better careers and increased cultural opportunity: Wales's third greatest revenue earner is media products and Cardiff boasts a world-class animation industry.

Although Welsh is a minority language, and thus threatened by the dominance of English, support for the language grew during the second half of the 20th century, along with the rise of Welsh nationalism in the form of groups such as the political party Plaid Cymru and Cymdeithas yr Iaith Gymraeg (Welsh Language Society). The language is used in the bilingual Welsh Assembly and entered on its records, with English translation. Technically it is not supposed to be used in the British Parliament as it is referred to as a "foreign language" and is effectively banned as disruptive behaviour, but several Speakers (most notably George Thomas, 1st Viscount Tonypandy, himself born in Wales, close by Tonypandy) spoke Welsh in longer English-language speeches.

Welsh as a first language is largely concentrated in the less urban north and west of Wales, principally Gwynedd, inland Denbighshire, northern and south-western Powys, Ynys Môn, Carmarthenshire, North Pembrokeshire, Ceredigion, and parts of western Glamorgan, although first-language and other fluent speakers can be found throughout Wales. However, Cardiff is now home to an urban Welsh speaking population (both from other parts of Wales and from the growing Welsh medium schools of Cardiff itself) due to the centralisation and concentration of national resources and organisations in the capital.

The Welsh language is an important part of Welsh identity, but not an essential part. Welsh people actively distinguish between 'Cymry Cymraeg' (Welsh-speaking Welsh), Cymry di-Gymraeg (non Welsh speaking Welsh) and Saeson (English). Parts of the culture are however strongly connected to the language - notably the Eisteddfodic tradition, poetry and aspects of folk music and dance. However, Wales has a strong tradition of poetry in the English language.

Religion

See also Religion in Wales.

Most Welsh people of faith are affiliated with the Church in Wales or other Christian denominations such as the Presbyterian Church of Wales or Catholicism, although there is even a Russian Orthodox chapel in the semi-rural town of Blaenau Ffestiniog. In particular, Wales has a long tradition of nonconformism and Methodism. Other religions Welsh people may be affiliated with include Buddhism, Hinduism, Judaism, Islam, and Sikhism, with most non-Christian people in Wales found in Cardiff.

The 2001 Census showed that slightly less than 10% of the Welsh population are regular church or chapel goers (a slightly smaller proportion than in England or Scotland), although about 70% of the population see themselves as some form of Christian. Judaism has quite a long history in Wales, with a Jewish community recorded in Swansea from around 1730. In August 1911, during a period of public order and industrial disputes, Jewish shops across the South Wales coalfield were damaged by mobs. Since that time the Jewish population of that area, which reached a peak of 4,000–5,000 in 1913, has declined with only Cardiff retaining a sizeable Jewish population, of about 2000 in the 2001 Census. The largest non-Christian faith in Wales is Islam, with about 22,000 members in 2001 served by about 40 mosques, following the first mosque established in Cardiff in 1860. A college for training clerics has been established at Llanybydder in West Wales. Islam arrived in Wales in the mid 19th century, and it is thought that Cardiff's Yemeni community is Britain's oldest Muslim community, established when the city was one of the world's largest coal-exporting ports. Hinduism and Buddhism each have about 5,000 adherents in Wales, with the rural county of Ceredigion being the centre of Welsh Buddhism. Govinda's temple & restaurant, ran by the Hare Krishna's in Swansea is a focal point for many Welsh Hindus. There are about 2,000 Sikhs in Wales, with the first purpose-built gurdwara opened in the Riverside area of Cardiff in 1989. In 2001 some 7,000 people classified themselves as following "other religions" including a reconstructed form of Druidism, which was the pre-Christian religion of Wales (not to be confused with the Druids of the Gorsedd at the National Eisteddfod of Wales). Approximately one sixth of the population, some 500,000 people, profess no religious faith whatsoever.

The sabbatarian temperance movement was also historically strong among the Welsh, the sale of alcohol being prohibited on Sundays in Wales by the Sunday Closing (Wales) Act 1881 - the first legislation specifically issued for Wales since the Middle Ages. From the early 1960s, local council areas were permitted to hold referendums every seven years to determine whether they should be "wet" or "dry" on Sundays: most of the industrialised areas in the east and south went "wet" immediately, and by the 1980s the last district, Dwyfor in the northwest, went wet, since then there have been no more Sunday-closing referendums.

National symbols

- The Flag of Wales incorporates the red dragon (Y Ddraig Goch) of Prince Cadwalader along with the Tudor colours of green and white. It was used by Henry VII at the battle of Bosworth in 1485 after which it was carried in state to St. Paul's Cathedral. The red dragon was then included in the Tudor royal arms to signify their Welsh descent. It was officially recognised as the Welsh national flag in 1959. The British Union Flag incorporates the flags of Scotland, Ireland and England but does not have any Welsh representation. Technically, however, it is represented by the flag of England due to the Laws in Wales act of 1535 which annexed Wales following the 13th century conquest.

- The flag of the princely House of Aberffraw, which has 4 squares alternating in red and yellow and then a guardant lion in each square of the opposite colour. The flag was first associated with Llywelyn I The Great, who received the fealty of all other Welsh lords at the Treaty of Aberdyfi in 1216, becoming de jure Prince of Wales, according to historian John Davies. The Aberffraw family claimed primacy as princes of Wales as the senior decendants of Rhodri the Great, and included Owain I, who was known as princeps Wallensium (Prince of the Welsh), and Llywelyn II. The current claimant may be Sir David Watkin Williams-Wynn, 11th Baronet.

- The flag of Owain Glyndŵr, Prince of Wales, which combined the flags of Powys and Deheubarth, has 4 squares alternating in red and yellow and then a rampant lion in each square of the opposite colour. The red lion on a yellow field represented Powys, and the yellow lion on a red field represented Deheubarth. Owain was the senior heir of both Powys and Deheubarth. The flag harkened back to the Aberffraw flag, linking Owain's rule with the Aberffraw princes of Wales in an effort to legitimize his rule.

- The Dragon, part of the national flag design, is also a popular Welsh symbol. The oldest recorded use of the dragon to symbolise Wales is from the Historia Brittonum, written around 820, but it is popularly supposed to have been the battle standard of King Arthur and other ancient Celtic leaders. This myth is likely to have originated from Merlin's vision of a Red (The Native Britons) and White (The Saxon Invaders) dragon battling, with the red dragon being victorious. Following the annexation of Wales by England, the red dragon was used as a supporter in the English monarch's coat of arms. The red dragon is often seen as a shorthand for all things Welsh, being used by many indigenous public and private institutions (eg: The Welsh Assembly Government, Visit Wales, numerous local authorities including Blaenau Gwent, Cardiff, Carmarthenshire, Newport, Rhondda, Cynnon Taf, Swansea, and sports bodies, including the Welsh Institute of Sport, the Football Association of Wales, Newport Gwent Dragons, London Welsh RFC, etc.)

- The leek is also a national emblem of Wales. According to legend, Saint David ordered his Welsh soldiers to identify themselves by wearing the vegetable on their helmets in an ancient battle against the Saxons that took place in a leek field. It is still worn on St David's Day each March 1

- The daffodil is the national flower of Wales, and is worn on St David's Day each March 1. (In Welsh, the daffodil is known as "Peter's Leek", cenhinen Bedr/Cenin pedr.)

- The Sessile Oak is the national tree of Wales.

- The Flag of Saint David is sometimes used as an alternative to the national flag (and used in part of Cardiff City FC's crest), and is flown on St David's Day.

- The Coat of Arms of the Principality of Wales which are the historic arms of the Kingdom of Gwynedd are used by Charles, Prince of Wales in his personal standard.

- The Prince of Wales's feathers, the heraldic badge of the Prince of Wales is sometimes adapted by Welsh bodies for use in Wales. The symbolism is explained on the article for Edward, the Black Prince, who was the first Prince of Wales to bear the emblem; see also John, King of Bohemia. The Welsh Rugby Union uses such a design for its own badge. The national sport is often considered rugby union, though football is very popular too.

- The red kite is sometimes named as the national symbol of wildlife in Wales.

- Patriotic anthems for "the land of Song" include "Hen Wlad fy Nhadau" ("Land of My Fathers") (national anthem), "Men of Harlech", "Cwm Rhondda" (national hymn), "Delilah", "Calon Lan", "Sosban Fach".

Welsh emigration

Migration from Wales to the rest of Britain has been occurring throughout its history. Particularly during the Industrial Revolution hundreds of thousands of Welsh people migrated internally to the big cities of England and Scotland or to work in the coal mines of the north of England. As a result, much of the British population today have ancestry from Wales. The same can be said for the English, Scottish and Irish workers who migrated to Welsh cities such as Merthyr Tydfil or ports such as Pembroke in the Industrial Revolution. As a result, some English, Irish and Scottish have Welsh surnames ("Evans", "Jenkins" "Owen" etc.) and some Welsh have English, Scottish and Irish surnames - as a result, it is relatively rare in South Wales or English-speaking areas to find a person with exclusively Welsh ancestry.

Some thousands of Welsh settlers moved to other parts of Europe, but the number was sparse and concentrated to certain areas. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a small wave of contract miners from Wales arrived into Northern France, and the centre of Welsh-French populations are in coal mining towns of the French department Pas-de-Calais. Welsh settlers from Wales (and later Patagonian Welsh) arrived in Newfoundland, Canada in the early 1900s, many had founded towns in the province's Labrador coast region.

Internationally Welsh people have emigrated, in relatively small numbers (in proportion to population Irish emigration to the United States of America (USA) may have been 26 times greater than Welsh emigration), to many countries, including the USA (in particular, Pennsylvania), Canada and Patagonia. Jackson County, Ohio was sometimes referred to as Little Wales and the Welsh language was commonly heard or spoken among locals by the mid 20th century. Malad City in Idaho, which began as a Welsh Mormon Settlement, lays claim to having more people of Welsh descent per capita than anywhere outside of Wales itself. Malad's local High School is known as the "Malad Dragons" and flies the Welsh Flag as its school colours. Welsh people have also settled as far as New Zealand and Australia.

Around 1.75 million Americans report themselves to have Welsh ancestry, as did a further 467,000 in Canada's 2006 census. This compares with 2.9 million people living in Wales (as of the 2001 census).

There is no known evidence which would objectively support the legend that the Mandan, a Native American tribe of the central United States, are Welsh emigrants who reached North America under Prince Madog in 1170.

See also

Column-generating template families

The templates listed here are not interchangeable. For example, using {{col-float}} with {{col-end}} instead of {{col-float-end}} would leave a <div>...</div> open, potentially harming any subsequent formatting.

| Type | Family | Handles wiki table code? |

Responsive/ mobile suited |

Start template | Column divider | End template |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Float | "col-float" | Yes | Yes | {{col-float}} | {{col-float-break}} | {{col-float-end}} |

| "columns-start" | Yes | Yes | {{columns-start}} | {{column}} | {{columns-end}} | |

| Columns | "div col" | Yes | Yes | {{div col}} | – | {{div col end}} |

| "columns-list" | No | Yes | {{columns-list}} (wraps div col) | – | – | |

| Flexbox | "flex columns" | No | Yes | {{flex columns}} | – | – |

| Table | "col" | Yes | No | {{col-begin}}, {{col-begin-fixed}} or {{col-begin-small}} |

{{col-break}} or {{col-2}} .. {{col-5}} |

{{col-end}} |

Can template handle the basic wiki markup {| | || |- |} used to create tables? If not, special templates that produce these elements (such as {{(!}}, {{!}}, {{!!}}, {{!-}}, {{!)}})—or HTML tags (<table>...</table>, <tr>...</tr>, etc.)—need to be used instead.

External links

- BBC Wales: Welsh Comings and Goings: The history of migration in and out of Wales

- BBC News report: The Numbers of Welsh (and Cornish)

- BBC News report: English and Welsh are races apart

- BBC News report: Genes link Celts to Basques

- BBC: The Welsh in Patagonia

- Glaniad - Welsh Settlements in Patagonia

- data-wales.co.uk: Emigration from Wales to America

- data-wales.co.uk: Why do so many Black Americans have Welsh names?

- Genetic data and

- Link2Wales: Encyclopedia of the alternative music scene in Wales

- A Y chromosome census of the British Isles, data from paper displayed on map of British Isles

- 418,000 write in 'Welsh' on 2001 Census form

- Gathering the Jewels - Welsh Heritage and Culture

References

- Not Available UK Census 2001 collected data on country of birth but not on self-selected ancestry or ethnic origin as with the US, Australian and Canadian censuses.

- ^ Estimated from population of Wales from 2001 census (2,903,085 Census 2001 Wales) with 89% of the population identifying as Welsh in 2001 (Devolution, Public Attitudes and National Identity)

- "City of Aberdeen: Census Stats and Facts" (PDF).

- "Welsh people in England".

- ^ 2006 Census ("U.S. Census Bureau 2006 Census Fact Sheet".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|547;&-ds_name=ignored (help)) - ^ In the Canadian census of 2006, 27,115 people identified themselves as belonging only to the Welsh ethnic group, while an additional 413,855 included Welsh as one of multiple ethnic groups they claimed to belong to.

- The 2001 New Zealand census reports 3,342 people stating they belong to the Welsh ethnic group. The 1996 census, which used a slightly different question, reported 9,966 people belonging to the Welsh ethnic group.

- 2001 Census ("Government of Australia - ausstats.abs.gov.au" (PDF).)

- BBC: Y Wladfa - The Welsh in Patagonia

- "Sacred Destinations Travel Guide".

- Davies, John, A History of Wales, Penguin: 1994; Welshorigions p.54, ISBN 0-14-01-4581-8.

- All Wales Convention

- Cunliffe, B. Iron Age communities in Britainpp. 115-118

- ^ Iron Age Britain by Barry Cunliffe. Batsford. ISBN 0-7134-8839-5.

- Britain BC: Life in Britain and Ireland Before the Romans by Francis Pryor, pp. 121-122. Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-00-712693-X.

- Mallory, J.P. In Search of the Indo-Europeans pp. 106-107, Thames & Hudson

- ^ Estimating the Impact of Prehistoric Admixture on the Genome of Europeans by Isabelle Dupanloup, Giorgio Bertorelle, Lounès Chikhi and Guido Barbujani (2004). Molecular Biology and Evolution: 21(7):1361-1372. Retrieved 10 July 2006.

- del Giorgio, J.F. 2006. The Oldest Europeans. A.J. Place, ISBN 980-6898-00-1

- What happened after the fall of the Roman Empire?: BBC Wales-History. Retrieved 3 October 2006.

- Special report: 'Myths of British ancestry' by Stephen Oppenheimer | Prospect Magazine October 2006

- 'Celts descended from Spanish fishermen, study finds'-This Britain, UK-The Independent 20 September 2006

- [http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=33166 From the Cover: Genetic evidence for different male and female roles during cultural transitions in the British Isles]

- ^ BBC News | WALES | Genes link Celts to Basques 3 April 2001

- High-Resolution Phylogenetic Analysis of Southeastern Europe Traces Major Episodes of Paternal Gene Flow Among Slavic Populations

- Jarman, A.O.H. 1988. Y Gododdin: Britain's earliest heroic poem p. xviii

- Davies, John, A History of Wales, published 1990 by Penguin, ISBN 0-14-014581-8

- Davies, J. A history of Wales pp. 65-6

- Williams, Ifor. 1972. The beginnings of Welsh poetry University of Wales Press. p. 71

- Williams, Gwyn A., The Welsh in their History, published 1982 by Croom Helm, ISBN 0-7099-3651-6

- Davies, John, A History of Wales, published 1990 by Penguin, ISBN 0-14-014581-8

- The Flemish colonists in Wales: BBC website. Retrieved 17 August 2006.

- 200 years of the Census in...WALES Office for National Statistics

- Industrial Revolution BBC The Story of the Welsh

- Population therhondda.co.uk. Retrieved 9 May 2006

- ^ Census shows Welsh language rise Friday, 14 February, 2003 extracted 12-04-07

- ^ Census equality backed by Plaid 23 September, 2000 extracted 12-04-07

- Census results 'defy tick-box row' 30 September, 2002 extracted 12-04-07

- Scottish Parliament's Review of Census Ethnicity Classifications Consultation: June 2005 extrated April 7, 2008

- Census shows Welsh language rise Friday, 14 February, 2003 extracted 12-04-07

- ^ NSO article: 'Welsh' on Census form published 8 January 2004, extracted 7 April 2008

- ^ UK ONS Welsh National Identity published 8 January 2004, extracted 7 April 2008

- Apology over 'insults' to English, BBC Wales, 3 September, 2001

- UK: Wales Plaid calls for second home controls, BBC Wales, November 17, 1999

- Plaid plan 'protects' rural areas, BBC Wales, 19 June, 2001

- The RSPB: Red kite voted Wales' Favourite Bird

- ^ Nineteenth Century Arrivals in Australia: University of Wales, Lampeter website. Retrieved 3 August 2006.

- Welsh in Pennsylvania by Matthew S. Magda (1986), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. From Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Retrieved 3 August 2006.

- WELSH: Multicultural Canada. Retrieved 3 August 2006.

- South America - Patagonia: BBC - Wales History. Retrieved 3 August 2006.

- Tiny US town's big Welsh heritage: BBC News, 20 July 2005. Retrieved 3 August 2006.

- WELSH HISTORY, The Welsh in North America, Utah: Welsh Society of Central Ohio. Retrieved 3 August 2006.

- Welsh immigration from . Retrieved 3 August 2003.

- Adams, Cecil (2006). "Straight Dope: Was there an Indian tribe descended from Welsh explorers to America?".

Further reading

- John Davies, A History of Wales, published 1990 by Penguin, ISBN 0-14-014581-8

- Norman Davies, The Isles, published 1991 by Papermac, ISBN 0-333-69283-7

- Gwyn A Williams, The Welsh in their History, published 1982 by Croom Helm, ISBN 0-7099-3651-6

- J.F. del Giorgio, The Oldest Europeans, published 2005 by A.J. Place, ISBN 980-6898-00-1

- Adrian Hastings, The Construction of Nationhood: Ethnicity, Religion, and Nationalism, published in 1997 by Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521625440