| Revision as of 08:36, 5 March 2009 view sourceEubulides (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Pending changes reviewers27,779 edits →History: Don't overdo Eckardt's opinion of English dental care in 1874, as there's no evidence he was a reliable source on that issue.← Previous edit | Revision as of 08:50, 5 March 2009 view source Eubulides (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Pending changes reviewers27,779 edits →History: Briefly mention New Zealand's history and cite Akers 2008.Next edit → | ||

| Line 123: | Line 123: | ||

| In the 1930s and early 1940s, ] and colleagues at the ] published several ] studies suggesting that a fluoride concentration of about 1 mg/L was associated with substantially fewer cavities in temperate climates, and that it increased fluorosis but only to a level that was of no medical or aesthetic concern. Other studies found no other significant adverse effects even in areas with fluoride levels as high as 8 mg/L.<ref name=Lennon>{{cite journal |author= Lennon MA |title= One in a million: the first community trial of water fluoridation |journal= Bull World Health Organ |volume=84 |issue=9 |pages=759–60 |year=2006 |pmid=17128347 |doi=10.1590/S0042-96862006000900020 |url=http://www.scielosp.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0042-96862006000900020}}</ref> To test the hypothesis that adding fluoride would prevent cavities, Dean and his colleagues conducted a ] by fluoridating the water in ], starting on January 29, 1945. The results, published in 1950, showed significant reduction of cavities.<ref>{{cite journal |author= ], Arnold FA, Jay P, Knutson JW |title= Studies on mass control of dental caries through fluoridation of the public water supply |journal= Public Health Rep |volume=65 |issue=43 |pages=1403–8 |year=1950 |pmid=14781280 |pmc=1997106}}</ref> Significant reductions in tooth decay were also reported by important early studies outside the U.S., including the Brantford-Sarnia-Stratford study in Canada (1945–1962), the Tiel-Culemborg study in the Netherlands (1953–1969), the Hastings study in New Zealand (1954–1970), and the Department of Health study in the U.K. (1955–1960).<ref name=Mullen/> By present-day standards these and other pioneering studies were crude, but the large reductions in cavities convinced public health professionals of the benefits of fluoridation.<ref name=Burt/> | In the 1930s and early 1940s, ] and colleagues at the ] published several ] studies suggesting that a fluoride concentration of about 1 mg/L was associated with substantially fewer cavities in temperate climates, and that it increased fluorosis but only to a level that was of no medical or aesthetic concern. Other studies found no other significant adverse effects even in areas with fluoride levels as high as 8 mg/L.<ref name=Lennon>{{cite journal |author= Lennon MA |title= One in a million: the first community trial of water fluoridation |journal= Bull World Health Organ |volume=84 |issue=9 |pages=759–60 |year=2006 |pmid=17128347 |doi=10.1590/S0042-96862006000900020 |url=http://www.scielosp.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0042-96862006000900020}}</ref> To test the hypothesis that adding fluoride would prevent cavities, Dean and his colleagues conducted a ] by fluoridating the water in ], starting on January 29, 1945. The results, published in 1950, showed significant reduction of cavities.<ref>{{cite journal |author= ], Arnold FA, Jay P, Knutson JW |title= Studies on mass control of dental caries through fluoridation of the public water supply |journal= Public Health Rep |volume=65 |issue=43 |pages=1403–8 |year=1950 |pmid=14781280 |pmc=1997106}}</ref> Significant reductions in tooth decay were also reported by important early studies outside the U.S., including the Brantford-Sarnia-Stratford study in Canada (1945–1962), the Tiel-Culemborg study in the Netherlands (1953–1969), the Hastings study in New Zealand (1954–1970), and the Department of Health study in the U.K. (1955–1960).<ref name=Mullen/> By present-day standards these and other pioneering studies were crude, but the large reductions in cavities convinced public health professionals of the benefits of fluoridation.<ref name=Burt/> | ||

| Fluoridation became an official policy of the ] by 1951, and by 1960 water fluoridation had become widely used in the U.S., reaching about 50 million people.<ref name=Lennon/> By 2006, 69.2% of the U.S. population on public water systems were receiving fluoridated water, amounting to 61.5% of the total U.S. population; 3.0% of the population on public water systems were receiving naturally occurring fluoride.<ref name=US-WF-Stats-2006>{{cite web |author= Division of Oral Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC |title= Water fluoridation statistics for 2006 |url=http://cdc.gov/fluoridation/statistics/2006stats.htm |date=September 17, 2008 |accessdate=December 22, 2008}}</ref> In some other countries the pattern was similar. Fluoridation was introduced into Brazil in 1953, was regulated by federal law starting in 1974, and by 2004 was used by 71% of the population.<ref>{{cite journal |author= Buzalaf MA, de Almeida BS, Olympio KPK, da S Cardoso VE, de CS Peres SH |title= Enamel fluorosis prevalence after a 7-year interruption in water fluoridation in Jaú, São Paulo, Brazil |journal= J Public Health Dent |volume=64 |issue=4 |pages=205–8 |year=2004 |doi=10.1111/j.1752-7325.2004.tb02754.x |pmid=15562942}}</ref> In the Republic of Ireland, fluoridation was legislated in 1960, and after a constitutional challenge the two major cities of Dublin and Cork began it in 1964;<ref name=Mullen/> fluoridation became required for all sizeable public water systems and by 1996 reached 66% of the population.<ref name=extent/> In other locations, fluoridation was used and then discontinued: in ], Finland, fluoridation was used for decades but was discontinued because the school dental service provided significant fluoride programs and the cavity risk was low, and in ], Switzerland, it was replaced with fluoridated salt.<ref name=Mullen/> | Fluoridation became an official policy of the ] by 1951, and by 1960 water fluoridation had become widely used in the U.S., reaching about 50 million people.<ref name=Lennon/> By 2006, 69.2% of the U.S. population on public water systems were receiving fluoridated water, amounting to 61.5% of the total U.S. population; 3.0% of the population on public water systems were receiving naturally occurring fluoride.<ref name=US-WF-Stats-2006>{{cite web |author= Division of Oral Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC |title= Water fluoridation statistics for 2006 |url=http://cdc.gov/fluoridation/statistics/2006stats.htm |date=September 17, 2008 |accessdate=December 22, 2008}}</ref> In some other countries the pattern was similar. New Zealand, which led the world in per-capita sugar consumption and had the world's worst teeth, began fluoridation in 1953, and by 1968 fluoridation was used by 65% of the population served by a piped water supply.<ref>{{cite journal |author= Akers HF |title= Collaboration, vision and reality: water fluoridation in New Zealand (1952–1968) |journal= N Z Dent J |volume=104 |issue=4 |pages=127–33 |year=2008 |pmid=19180863 |url=http://espace.library.uq.edu.au/eserv/UQ:159563/Akers_NZDJ_Dec_2008.pdf |format=PDF |accessdate= March 5, 2009}}</ref> Fluoridation was introduced into Brazil in 1953, was regulated by federal law starting in 1974, and by 2004 was used by 71% of the population.<ref>{{cite journal |author= Buzalaf MA, de Almeida BS, Olympio KPK, da S Cardoso VE, de CS Peres SH |title= Enamel fluorosis prevalence after a 7-year interruption in water fluoridation in Jaú, São Paulo, Brazil |journal= J Public Health Dent |volume=64 |issue=4 |pages=205–8 |year=2004 |doi=10.1111/j.1752-7325.2004.tb02754.x |pmid=15562942}}</ref> In the Republic of Ireland, fluoridation was legislated in 1960, and after a constitutional challenge the two major cities of Dublin and Cork began it in 1964;<ref name=Mullen/> fluoridation became required for all sizeable public water systems and by 1996 reached 66% of the population.<ref name=extent/> In other locations, fluoridation was used and then discontinued: in ], Finland, fluoridation was used for decades but was discontinued because the school dental service provided significant fluoride programs and the cavity risk was low, and in ], Switzerland, it was replaced with fluoridated salt.<ref name=Mullen/> | ||

| McKay's work had established that fluorosis occurred before ]. Dean and his colleagues assumed that fluoride's protection against cavities was also pre-eruptive, and this incorrect assumption was accepted for years. By 2000, however, the ] effects of fluoride (in both water and toothpaste) were well understood, and it had become known that a constant low level of fluoride in the mouth works best to prevent cavities.<ref name=Burt/> | McKay's work had established that fluorosis occurred before ]. Dean and his colleagues assumed that fluoride's protection against cavities was also pre-eruptive, and this incorrect assumption was accepted for years. By 2000, however, the ] effects of fluoride (in both water and toothpaste) were well understood, and it had become known that a constant low level of fluoride in the mouth works best to prevent cavities.<ref name=Burt/> | ||

Revision as of 08:50, 5 March 2009

Water fluoridation is the controlled addition of fluoride to a public water supply to reduce tooth decay. Fluoridated water has fluoride at a level that is effective for preventing cavities; this can occur naturally or by adding fluoride. Drinking fluoridated water creates low levels of fluoride in saliva, which reduces the rate at which tooth enamel demineralizes and increases the rate at which it remineralizes in the early stages of cavities. A recommended level of fluoride is 0.6 to 1.1 mg/L (milligrams per liter), depending on climate. Typically a fluoridated compound is added to drinking water, a process that costs about $0.72 per person per year in the U.S. (range $0.17–$7.62, in 1999 dollars). Defluoridation is needed when the naturally occurring fluoride level exceeds recommended limits. Bottled water typically has unknown fluoride levels, and some more-expensive household water filters remove some or all fluoride.

Dental cavities remain a major public health concern in most industrialized countries, affecting 60–90% of schoolchildren and the vast majority of adults. Water fluoridation prevents cavities in both children and adults, with more-recent studies estimating an 18–40% reduction in childhood cavities. Although it can cause dental fluorosis, which can alter the appearance of developing teeth, most of this is mild and usually not considered to be of aesthetic or public-health concern. There is no clear evidence of other adverse effects. Moderate-quality studies have investigated effectiveness; studies on adverse effects have been mostly of low quality. Fluoride's effects depend on the total daily intake of fluoride from all sources. Drinking water is the largest source; other methods of fluoride therapy include fluoridation of toothpaste, salt, and milk. Water fluoridation, when feasible and culturally acceptable, has substantial advantages, especially for subgroups at high risk. In the U.S., water fluoridation was listed as one of the ten great public health achievements of the 20th century; in contrast, most European countries have experienced substantial declines in tooth decay without its use, primarily due to the introduction of fluoride toothpaste in the 1970s. Fluoridation may be more justified in the U.S. because of socioeconomic inequalities in dental health and dental care.

Water fluoridation's goal is to prevent a chronic disease whose burdens particularly fall on children and on the poor. Its use presents a conflict between the common good and individual rights. It is controversial, and opposition to it has been based on ethical, legal, safety, and efficacy grounds. Almost all major public health and dental organizations support water fluoridation, or consider it safe. Its use began in the 1940s, following studies of children in a region where higher levels of fluoride occur naturally in the water. Researchers discovered that moderate fluoridation prevents cavities, and it is now used by 5.7% of people worldwide.

Goal

Water fluoridation's goal is to prevent tooth decay (dental caries), one of the most prevalent chronic diseases worldwide, and one which greatly affects the quality of life of children, particularly those of low socioeconomic status. In most industrialized countries, tooth decay affects 60–90% of schoolchildren and the vast majority of adults; although the problem appears to be less in Africa's developing countries, it is expected to increase in several countries there due to changing diet and inadequate fluoride exposure. In the U.S., minorities and the poor both have higher rates of decayed and missing teeth, and their children have less dental care. The motivation for fluoridation of salt or water is similar to that of iodized salt for the prevention of mental retardation and goiter.

Implementation

Fluoridation does not affect the appearance, taste, or smell of drinking water. It is normally accomplished by adding one of three compounds to the water: sodium fluoride, fluorosilicic acid, or sodium fluorosilicate.

- Sodium fluoride (NaF) was the first compound used and is the reference standard. It is a white, odorless powder or crystal; the crystalline form is preferred if manual handling is used, as it minimizes dust. It is more expensive, but is easily handled and is usually used by smaller utility companies.

- Fluorosilicic acid (H2SiF6) is a cheap liquid byproduct of phosphate fertilizer manufacture. It comes in varying strengths, typically 23–25%; because it contains so much water, shipping can be expensive. It is also known as hexafluorosilicic, hexafluosilicic, hydrofluosilicic, and silicofluoric acid.

- Sodium fluorosilicate (Na2SiF6) is a powder or very fine crystal that is easier to ship than fluorosilicic acid. It is also known as sodium silicofluoride.

These compounds were chosen for their solubility, safety, availability, and low cost. A 1992 census found that, for U.S. public water supply systems reporting the type of compound used, 63% of the population received water fluoridated with fluorosilicic acid, 28% with sodium fluorosilicate, and 9% with sodium fluoride. The estimated cost of fluoridation in the U.S., in 1999 dollars, is $0.72 per person per year (range: $0.17–$7.62); larger water systems have lower per capita cost, and the cost is also affected by the number of fluoride injection points in the water system, the type of feeder and monitoring equipment, the fluoride chemical and its transportation and storage, and water plant personnel expertise. In the U.S., the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has developed recommendations for water fluoridation that specify requirements for personnel, reporting, training, inspection, monitoring, surveillance, and actions in case of overfeed, along with technical requirements for each major compound used.

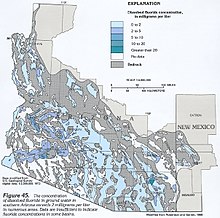

The U.S. specifies the optimal level of fluoride to range from 0.7 to 1.2 mg/L (milligrams per liter, equivalent to parts per million), depending on the average maximum daily air temperature; the optimal level is lower in warmer climates, where people drink more water, and is higher in cooler climates. In Australia the recommended range is from 0.6 to 1.1 mg/L. Fluoride in naturally occurring water supplies can be above, at, or below recommended levels. Rivers and lakes generally contain less than 0.5 mg/L, but groundwater, particularly in volcanic or mountainous areas, can contain as much as 50 mg/L. Defluoridation is needed when the naturally occurring fluoride level exceeds recommended limits. It can be accomplished by percolating water through granular beds of activated alumina, bone meal, bone char, or tricalcium phosphate; by coagulation with alum; or by precipitation with lime.

U.S. regulations for bottled water do not require disclosing fluoride content, so the effect of always drinking it is not known. Surveys of bottled water in Cleveland and in Iowa found that most contained well below optimal fluoride levels; a survey in São Paulo, Brazil, found large variations of fluoride, with many bottles exceeding recommended limits and disagreeing with their labels. Pitcher or faucet-mounted water filters do not alter fluoride; the more-expensive reverse osmosis filters remove 65–95% of fluoride, and distillation filters remove all fluoride.

Mechanism

Fluoride exerts its major effect by interfering with the demineralization mechanism of tooth decay. Tooth decay is an infectious disease whose key feature is an increase within dental plaque of bacteria such as Streptococcus mutans and Lactobacillus that produce organic acids when carbohydrates, especially sugar, are eaten. When enough acid is produced so that the pH goes below 5.5, the acid readily dissolves carbonated hydroxyapatite, the main ingredient of tooth enamel, in a process known as demineralization. After the sugar is gone, some of the mineral loss can be recovered by enamel from saliva; this is known as remineralization. Cavities result when demineralization overcomes remineralization, typically in a process that takes many months or years.

All fluoridation methods, including water fluoridation, create low levels of fluoride ions in saliva and plaque fluid, thus exerting a topical effect. A person living in an area with fluoridated water may experience rises of fluoride concentration in saliva to about 0.04 mg/L several times during a day. When fluoride ions are present in plaque fluid along with dissolved hydroxyapatite, and the pH is higher than 4.5, a fluorapatite-like remineralized veneer is formed over the remaining surface of the enamel; this veneer is much more acid-resistant than the original hydroxyapatite, and is formed more quickly than ordinary remineralized enamel would be. Fluoride also affects the physiology of dental bacteria, although its effect on bacterial growth does not seem to be relevant to cavity prevention. Technically, fluoride does not prevent cavities but rather controls the rate at which they develop. Although fluoride is the only well-documented agent with this property, it has been suggested that also adding some calcium to the water would reduce cavities further.

Fluoride's effects depend on the total daily intake of fluoride from all sources, with drinking water being the largest source. Other sources include toothpaste and other dental products; air pollution from fluoride-containing coal or from phosphate fertilizers; trona, used to tenderize meat in Tanzania; and tea leaves, particularly the tea bricks favored in parts of China. High fluoride levels have been found in other foods, including barley, cassava, corn, rice, taro, yams, and fish protein concentrate. A rough estimate is that an adult in a temperate climate consumes 0.6 mg/day of fluoride without fluoridation, and 2 mg/day with fluoridation. However, these values differ greatly among the world's regions: for example, in Sichuan, China it is estimated that due to coal pollution the average daily fluoride intake is 8.9 mg/day in food and 0.7 mg/day directly from the air, with drinking water contributing 0.1 mg/day. In many industrialized countries swallowed toothpaste is the main source of fluoride exposure in unfluoridated communities.

Evidence basis

Existing evidence strongly suggests that water fluoridation reduces tooth decay. There is also consistent evidence that it causes fluorosis, most of which is mild and not usually of aesthetic concern. There is no clear evidence of other adverse effects. Moderate-quality research exists as to water fluoridation's effectiveness and its potential association with cancer; research into other potential adverse effects has been almost all of low quality. Little high-quality research has been performed.

Effectiveness

Fluoride has contributed to the dental health of children and adults worldwide. Water fluoridation has been listed as one of the ten great public health achievements of the 20th century in the U.S., alongside vaccination, family planning, recognition of the dangers of smoking, and other achievements. Earlier studies showed that water fluoridation led to reductions of 50–60% in childhood cavities; more recent studies show lower reductions (18–40%), likely due to increasing use of fluoride from other sources, notably toothpaste, and also to the halo effect of food and drink made in fluoridated areas and consumed in unfluoridated ones.

A 2000 systematic review found that water fluoridation was statistically associated with a decreased proportion of children with cavities (the median of mean decreases was 14.6%, the range −5 to 64%), and with a decrease in decayed, missing, and filled primary teeth (the median of mean decreases was 2.25 teeth, the range 0.5 to 4.4 teeth), which is roughly equivalent to preventing 40% of cavities. An effect of water fluoridation was evident even in the assumed presence of fluoride from other sources such as toothpaste. The review found that the evidence was of moderate quality: many studies did not attempt to reduce observer bias, control for confounding factors, report variance measures, or use appropriate analysis. Although no major differences between natural and artificial fluoridation were apparent, the evidence was inadequate to reach a conclusion about any differences. Fluoride also prevents cavities in adults of all ages. There are fewer studies in adults however, and the design of water fluoridation studies in adults is inferior to that of studies of self- or clinically-applied fluoride. A 2007 meta-analysis found that water fluoridation prevented an estimated 27% of cavities in adults (95% confidence interval 19–34%), about the same fraction as prevented by exposure to any delivery method of fluoride (29% average, 95% CI: 16-42%). A 2002 systematic review found data seeming to support the conclusion that starting water fluoridation reduces tooth decay by 30–50% overall, and that stopping it leads to an 18% increase when other fluoride sources are inadequate.

The effectiveness of water fluoridation can vary depending on circumstances such as whether preventive dental care is free. Most countries in Europe have experienced substantial declines in cavities without the use of water fluoridation. For example, in Finland and Germany, tooth decay rates remained stable or continued to decline after water fluoridation stopped. Fluoridation may be more justified in the U.S. because unlike most European countries, the U.S. does not have school-based dental care, many children do not visit a dentist regularly, and for many U.S. children water fluoridation is the prime source of exposure to fluoride.

Although a 1989 workshop on cost-effectiveness of cavity prevention concluded that water fluoridation is one of the few public health measures that saves more money than it costs, little high-quality research has been done on the cost-effectiveness and solid data are scarce. Some studies suggest that fluoridation reduces oral health inequalities between the rich and poor, but the evidence is limited. There is anecdotal but not scientific evidence that fluoride allows more time for dental treatment by slowing the progression of tooth decay, and that it simplifies treatment by causing most cavities to occur in pits and fissures of teeth.

Safety

Fluoride's adverse effects depend on total fluoride dosage from all sources. At the commonly recommended dosage, the only clear adverse effect is dental fluorosis, which can alter the appearance of children's teeth during tooth development; this is mostly mild and is unlikely to represent any real effect on aesthetic appearance or on public health. Compared to water naturally fluoridated at 0.4 mg/L, fluoridation to 1 mg/L is estimated to cause additional fluorosis in one of every 6 people (95% CI 4–21 people), and to cause additional fluorosis of aesthetic concern in one of every 22 people (95% CI 13.6–∞ people). Here, aesthetic concern is a term used in a standardized scale based on what adolescents would find unacceptable, as measured by a 1996 study of British 14-year-olds. In many industrialized countries the prevalence of fluorosis is increasing even in unfluoridated communities, mostly due to fluoride from swallowed toothpaste; the total cost of treatment is unknown. A 2008 systematic review found suggestive evidence that fluorosis is caused by fluoride in infant formula or in water added to reconstitute the formula, though the evidence may be distorted by publication bias or confounding factors. In the U.S. the decline in tooth decay was accompanied by increased fluorosis in both fluoridated and unfluoridated communities; accordingly, fluoride has been reduced in various ways worldwide in infant formulas, children's toothpaste, water, and fluoride-supplement schedules.

Fluoridation has little effect on risk of bone fracture (broken bones); it may result in slightly lower fracture risk than either excessively high levels of fluoridation or no fluoridation. There is no clear association between fluoridation and cancer or deaths due to cancer, both for cancer in general and also specifically for bone cancer and osteosarcoma. Other adverse effects lack sufficient evidence to reach a confident conclusion.

Fluoride can occur naturally in water in concentrations well above recommended levels, which can have several long-term adverse effects, including severe dental fluorosis, skeletal fluorosis, and weakened bones. The World Health Organization recommends a guideline maximum fluoride value of 1.5 mg/L as a level at which fluorosis should be minimal. In rare cases improper implementation of water fluoridation can result in overfluoridation that causes outbreaks of acute fluoride poisoning, with symptoms that include nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Three such outbreaks were reported in the U.S. between 1991 and 1998, caused by fluoride concentrations as high as 220 mg/L; in the 1992 Alaska outbreak, 262 people became ill and one person died.

Like other common water additives such as chlorine, hydrofluosilicic acid and sodium silicofluoride decrease pH and cause a small increase of corrosivity, but this problem is easily addressed by increasing the pH. Although it has been hypothesized that hydrofluosilicic acid and sodium silicofluoride might increase human lead uptake from water, a 2006 statistical analysis did not support concerns that these chemicals cause higher blood lead concentrations in children. Trace levels of arsenic and lead may be present in fluoride compounds added to water, but no credible evidence exists that their presence is of concern: concentrations are below measurement limits.

The effect of water fluoridation on the environment has been investigated, and no adverse effects have been established. Issues studied have included fluoride concentrations in groundwater and downstream rivers; lawns, gardens, and plants; consumption of plants grown in fluoridated water; air emissions; and equipment noise.

Alternative methods

Methods effective in preventing tooth decay include dental sealants and fluoride therapies that also include fluoridation of toothpaste, salt, and milk. Other public-health strategies to control tooth decay, such as education to change behavior and diet, have lacked impressive results.

Fluoride toothpaste is the most widely used and rigorously evaluated fluoride treatment. Its introduction in the early 1970s is considered the main reason for the decline in tooth decay in industrialized countries, and the toothpaste appears to be the single common factor in countries where tooth decay has declined. Toothpaste is the only realistic fluoride strategy in many low-income countries, where lack of infrastructure renders water or salt fluoridation infeasible. However, it relies on individual and family behavior, and its use is less likely among the underprivileged; in low-income countries it is unaffordable for the poor.

The effectiveness of salt fluoridation is about the same as water fluoridation, if most salt for human consumption is fluoridated. Fluoridated salt reaches the consumer in salt at home, in meals at school and at large kitchens, and in bread. For example, Jamaica has just one salt producer, but a complex public water supply; it fluoridated all salt starting in 1987, resulting in a notable decline in cavities. Universal salt fluoridation is also practiced in Colombia and the Swiss Canton of Vaud; in France and Germany fluoridated salt is widely used in households but unfluoridated salt is also available, giving consumers choice about fluoride. Concentrations of fluoride in salt range from 90 to 350 mg/kg, with studies suggesting an optimal concentration of around 250 mg/kg.

Milk fluoridation is practiced by the Borrow Foundation in some parts of Bulgaria, Chile, Peru, Russia, Thailand and the United Kingdom. Depending on location, the fluoride is added to milk, to powdered milk, or to yogurt. For example, milk-powder fluoridation is used in rural Chilean areas where water fluoridation is not technically feasible. These programs are aimed at children, and have neither targeted nor been evaluated for adults. A 2005 systematic review found insufficient evidence to support the practice, but also concluded that studies suggest that fluoridated milk benefits schoolchildren, especially their permanent teeth.

A 2008 review commissioned by Australia concluded that water fluoridation is the most effective and socially equitable way to expose entire communities to fluoride's cavity-prevention effects. Dental sealants are more effective than fluoridation, but are cost-effective only when applied to high-risk children and teeth; a 2002 U.S. review estimated that sealants decreased cavities by about 60% overall, compared to about 18–50% for fluoride, and that on average, sealing first permanent molars saves costs when they are decaying faster than 0.47 surfaces per person-year whereas water fluoridation saves costs when total decay incidence exceeds 0.06 surfaces per person-year. A 2007 Italian review suggested that water fluoridation may not be needed, particularly in the industrialized countries where cavities have become rare, and concluded that toothpaste and other topical fluoride offers a best way to prevent cavities worldwide. In the U.S., water fluoridation is more cost-effective than other methods to reduce tooth decay in children, and a 2008 review concluded that water fluoridation is the best tool for combating cavities in many countries, particularly among socially disadvantaged groups. A 2004 World Health Organization review stated that water fluoridation, when it is culturally acceptable and technically feasible, has substantial advantages in preventing tooth decay, especially for subgroups at high risk.

Ethics and politics

Further information: Opposition to water fluoridationLike vaccination and food fortification, fluoridation presents a conflict between benefiting the common good and infringing on individual rights. Fluoridation can be viewed as a violation of ethical or legal rules that prohibit medical treatment without medical supervision or informed consent, and that prohibit administration of unlicensed medical substances. It can also be viewed as a public intervention to replicate the benefits of naturally fluoridated water in order to free people from the misery of toothache and dental work, with greatest benefit to those least able to help themselves, and where it would be unethical to withhold such treatment.

Almost all major health and dental organizations support water fluoridation, or have found no association between fluoridation and adverse health effects. These organizations include the World Health Organization, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the U.S. Surgeon General, and the national dental associations of Australia, Canada, and the U.S.

Despite support by public health organizations and authorities, efforts to introduce water fluoridation meet considerable opposition whenever it is proposed. Since fluoridation's inception, proponents have argued for scientific optimism and faith in experts, while opponents have drawn on distrust of experts and unease about medicine and science. Controversies include disputes over fluoridation's benefits and the strength of the evidence basis for these benefits, the difficulty of identifying harms, legal issues over whether water fluoridation is a medicine, and the ethics of mass intervention. Opposition campaigns involve newspaper articles, talk radio, and public forums. Media reporters are often poorly equipped to explain the scientific issues, and are motivated to present controversy regardless of the underlying scientific merits. Internet websites, which are increasingly used by the public for health information, contain a wide range of material about fluoridation ranging from factual to fraudulent, with a disproportionate percentage opposed to fluoridation. Conspiracy theories involving fluoridation are common, and include claims that fluoridation was motivated by protecting the U.S. atomic bomb program from litigation, that it is part of a Communist or New World Order plot to take over the world, that it was pioneered by a German chemical company to make people submissive to those in power, that it is backed by the sugar or aluminum or phosphate industries, or that it is a smokescreen to cover failure to provide dental care to the poor. Specific antifluoridation arguments change to match the spirit of the time.

Opponents of fluoridation include some researchers, dental and medical professionals, alternative medical practitioners such as chiropractors, and health food enthusiasts; a few religious objectors, mostly Christian Scientists in the U.S.; and occasionally consumer groups and environmentalists. Organized political opposition has come from right-wing groups such as the John Birch Society, and more recently from left-wing groups like the Green Party. Many people do not know that fluoridation is meant to prevent tooth decay, or that natural or bottled water can contain fluoride; as the general public does not have a particular view on fluoridation, the debate may reflect an argument between two relatively small lobbies. A 2003 study of focus groups from 16 European countries found that fluoridation was opposed by a majority of focus group members in most of the countries, including France, Germany, and the UK. A 1999 survey in Sheffield, UK found that while a 62% majority favored water fluoridation in the city, the 31% that were opposed expressed their preference with greater intensity than supporters. A 2007 bioethical council report concluded that local and regional democratic procedures are the most appropriate way to decide whether to fluoridate. Every year in the U.S., pro- and anti-fluoridationists face off in referenda or other public decision-making processes: in most of them, fluoridation is rejected. In the U.S., rejection is more likely when the decision is made by a public referendum; in Europe, most decisions against fluoridation have been made administratively. Neither side of the dispute appears to be weakening or willing to concede.

Use around the world

Fluoridated water is used by about 5.7% of people worldwide, including 61.5% of the U.S. population. In the U.S., Hispanic and Latino Americans are significantly more likely to consume bottled instead of tap water, and the use of bottled and filtered water grew dramatically in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

Fluoridation has been introduced to varying degrees in many other countries, including Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Hong Kong, Ireland, Israel, Korea, Malaysia, New Zealand, the Philippines, Singapore, Spain, the UK, and Vietnam; about 12 million people in western Europe and about 360 million people worldwide receive artificially fluoridated water. In addition, at least 50 million people worldwide drink water that is naturally fluoridated to optimal levels, in countries that include Argentina, France, Gabon, Libya, Mexico, Senegal, Sri Lanka, Tanzania, the U.S., and Zimbabwe. In some locations, notably parts of Africa, China, and India, natural fluoridation exceeds recommended levels. Locations have discontinued water fluoridation in some other countries, including Finland, Germany, Japan, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Switzerland. This change was often motivated by political opposition to water fluoridation, but sometimes the need for water fluoridation was met by alternative strategies, such as fluoridated salt. The use of fluoride in its various forms is the foundation of tooth decay prevention throughout Europe; for example, France, Germany, and many other European countries use fluoridated salt.

History

Main article: History of water fluoridation

Fluoride's dental-health benefits were recognized in the 19th century by British physician James Crichton-Browne, who in an address noted that fluoride's absence from diets had resulted in teeth that were "peculiarly liable to decay", and who proposed "the reintroduction into our diet ... of fluorine in some suitable natural form ... to fortify the teeth of the next generation". Earlier, in 1874, a Dr. Eckardt had recommended potassium fluoride to preserve teeth.

The history of water fluoridation can be divided into three periods. The first (c. 1901–33) was research into the cause of a form of mottled tooth enamel called the Colorado Brown Stain, which later became known as fluorosis. The second (c. 1933–45) focused on the relationship between fluoride concentrations, fluorosis, and tooth decay. The third period, from 1945 on, focused on adding fluoride to community water supplies.

The foundation of water fluoridation in the U.S. was the research of the dentist Frederick McKay. McKay spent thirty years investigating the cause of what was then known as the Colorado Brown Stain, which produced mottled but also cavity-free teeth; with the help of G.V. Black and other researchers, he established that the cause was fluoride. The first report of a statistical association between the stain and lack of tooth decay was made by UK dentist Norman Ainsworth in 1925. In 1931, an Alcoa chemist, H.V. Churchill, concerned about a possible link between aluminum and staining, analyzed water from several areas where the staining was common and found that fluoride was the common factor.

In the 1930s and early 1940s, H. Trendley Dean and colleagues at the U.S. National Institutes of Health published several epidemiological studies suggesting that a fluoride concentration of about 1 mg/L was associated with substantially fewer cavities in temperate climates, and that it increased fluorosis but only to a level that was of no medical or aesthetic concern. Other studies found no other significant adverse effects even in areas with fluoride levels as high as 8 mg/L. To test the hypothesis that adding fluoride would prevent cavities, Dean and his colleagues conducted a controlled experiment by fluoridating the water in Grand Rapids, Michigan, starting on January 29, 1945. The results, published in 1950, showed significant reduction of cavities. Significant reductions in tooth decay were also reported by important early studies outside the U.S., including the Brantford-Sarnia-Stratford study in Canada (1945–1962), the Tiel-Culemborg study in the Netherlands (1953–1969), the Hastings study in New Zealand (1954–1970), and the Department of Health study in the U.K. (1955–1960). By present-day standards these and other pioneering studies were crude, but the large reductions in cavities convinced public health professionals of the benefits of fluoridation.

Fluoridation became an official policy of the U.S. Public Health Service by 1951, and by 1960 water fluoridation had become widely used in the U.S., reaching about 50 million people. By 2006, 69.2% of the U.S. population on public water systems were receiving fluoridated water, amounting to 61.5% of the total U.S. population; 3.0% of the population on public water systems were receiving naturally occurring fluoride. In some other countries the pattern was similar. New Zealand, which led the world in per-capita sugar consumption and had the world's worst teeth, began fluoridation in 1953, and by 1968 fluoridation was used by 65% of the population served by a piped water supply. Fluoridation was introduced into Brazil in 1953, was regulated by federal law starting in 1974, and by 2004 was used by 71% of the population. In the Republic of Ireland, fluoridation was legislated in 1960, and after a constitutional challenge the two major cities of Dublin and Cork began it in 1964; fluoridation became required for all sizeable public water systems and by 1996 reached 66% of the population. In other locations, fluoridation was used and then discontinued: in Kuopio, Finland, fluoridation was used for decades but was discontinued because the school dental service provided significant fluoride programs and the cavity risk was low, and in Basle, Switzerland, it was replaced with fluoridated salt.

McKay's work had established that fluorosis occurred before tooth eruption. Dean and his colleagues assumed that fluoride's protection against cavities was also pre-eruptive, and this incorrect assumption was accepted for years. By 2000, however, the topical effects of fluoride (in both water and toothpaste) were well understood, and it had become known that a constant low level of fluoride in the mouth works best to prevent cavities.

References

- ^ Lamberg M, Hausen H, Vartiainen T (1997). "Symptoms experienced during periods of actual and supposed water fluoridation". Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 25 (4): 291–5. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0528.1997.tb00942.x. PMID 9332806.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2001). "Recommendations for using fluoride to prevent and control dental caries in the United States". MMWR Recomm Rep. 50 (RR-14): 1–42. PMID 11521913.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|laydate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help) - ^ Pizzo G, Piscopo MR, Pizzo I, Giuliana G (2007). "Community water fluoridation and caries prevention: a critical review". Clin Oral Investig. 11 (3): 189–93. doi:10.1007/s00784-007-0111-6. PMID 17333303.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia) (2007). "A systematic review of the efficacy and safety of fluoridation" (PDF). Retrieved February 24, 2009. Summary: Yeung CA (2008). "A systematic review of the efficacy and safety of fluoridation". Evid Based Dent. 9 (2): 39–43. doi:10.1038/sj.ebd.6400578. PMID 18584000.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|laydate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help) - ^ Taricska JR, Wang LK, Hung YT, Li KH (2006). "Fluoridation and defluoridation". In Wang LK, Hung YT, Shammas NK (eds.) (ed.). Advanced Physicochemical Treatment Processes. Handbook of Environmental Engineering 4. Humana Press. pp. 293–315. doi:10.1007/978-1-59745-029-4_9. ISBN 978-1-59745-029-4.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hobson WL, Knochel ML, Byington CL, Young PC, Hoff CJ, Buchi KF (2007). "Bottled, filtered, and tap water use in Latino and non-Latino children". Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 161 (5): 457–61. doi:10.1001/archpedi.161.5.457. PMID 17485621.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Petersen PE, Lennon MA (2004). "Effective use of fluorides for the prevention of dental caries in the 21st century: the WHO approach" (PDF). Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 32 (5): 319–21. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0528.2004.00175.x. PMID 15341615. Retrieved December 17, 2008.

- ^ Griffin SO, Regnier E, Griffin PM, Huntley V (2007). "Effectiveness of fluoride in preventing caries in adults". J Dent Res. 86 (5): 410–5. doi:10.1177/154405910708600504. PMID 17452559.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Summary: Yeung CA (2007). "Fluoride prevents caries among adults of all ages". Evid Based Dent. 8 (3): 72–3. doi:10.1038/sj.ebd.6400506. PMID 17891121. - ^ McDonagh M, Whiting P, Bradley M; et al. (2000). "A systematic review of public water fluoridation" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Report website: "Fluoridation of drinking water: a systematic review of its efficacy and safety". NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. 2000. Retrieved February 26, 2009. Authors' summary: McDonagh MS, Whiting PF, Wilson PM; et al. (2000). "Systematic review of water fluoridation" (PDF). BMJ. 321 (7265): 855–9. doi:10.1136/bmj.321.7265.855. PMC 27492. PMID 11021861.{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Authors' commentary: Treasure ET, Chestnutt IG, Whiting P, McDonagh M, Wilson P, Kleijnen J (2002). "The York review—a systematic review of public water fluoridation: a commentary". Br Dent J. 192 (9): 495–7. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.4801410. PMID 12047121.{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fawell J, Bailey K, Chilton J, Dahi E, Fewtrell L, Magara Y (2006). "Environmental occurrence, geochemistry and exposure". Fluoride in Drinking-water (PDF). World Health Organization. pp. 5–27. ISBN 92-4-156319-2. Retrieved January 24, 2009.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jones S, Burt BA, Petersen PE, Lennon MA (2005). "The effective use of fluorides in public health" (PDF). Bull World Health Organ. 83 (9): 670–6. PMID 16211158.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ CDC (1999). "Ten great public health achievements—United States, 1900–1999". MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 48 (12): 241–3. PMID 10220250. Reprinted in: JAMA. 281 (16): 1481. 1999. doi:10.1001/jama.281.16.1481. PMID 10227303.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Burt BA, Tomar SL (2007). "Changing the face of America: water fluoridation and oral health". In Ward JW, Warren C (ed.). Silent Victories: The History and Practice of Public Health in Twentieth-century America. Oxford University Press. pp. 307–22. ISBN 0-19-515069-4.

- ^ Selwitz RH, Ismail AI, Pitts NB (2007). "Dental caries". Lancet. 369 (9555): 51–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60031-2. PMID 17208642.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Ethics:

- McNally M, Downie J (2000). "The ethics of water fluoridation". J Can Dent Assoc. 66 (11): 592–3. PMID 11253350.

- Cohen H, Locker D (2001). "The science and ethics of water fluoridation". J Can Dent Assoc. 67 (10): 578–80. PMID 11737979.

- ^ Cheng KK, Chalmers I, Sheldon TA (2007). "Adding fluoride to water supplies". BMJ. 335 (7622): 699–702. doi:10.1136/bmj.39318.562951.BE. PMC 2001050. PMID 17916854.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Armfield JM (2007). "When public action undermines public health: a critical examination of antifluoridationist literature". Aust New Zealand Health Policy. 4: 25. doi:10.1186/1743-8462-4-25. PMC 2222595. PMID 18067684.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Ripa LW (1993). "A half-century of community water fluoridation in the United States: review and commentary" (PDF). J Public Health Dent. 53 (1): 17–44. PMID 8474047. Retrieved January 1, 2009.

- Hudson K, Stockard J, Ramberg Z (2007). "The impact of socioeconomic status and race-ethnicity on dental health". Sociol Perspect. 50 (1): 7–25. doi:10.1525/sop.2007.50.1.7.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Vargas CM, Ronzio CR (2006). "Disparities in early childhood caries". BMC Oral Health. 6 (Suppl 1): S3. doi:10.1186/1472-6831-6-S1-S3. PMC 2147596. PMID 16934120.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Horowitz HS (2000). "Decision-making for national programs of community fluoride use". Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 28 (5): 321–9. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0528.2000.028005321.x. PMID 11014508.

- ^ Reeves TG (1986). "Water fluoridation: a manual for engineers and technicians" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control. Retrieved December 10, 2008.

- ^ "History, theory, and chemicals". Water Fluoridation Principles and Practices. Manual of Water Supply Practices. Vol. M4 (5th ed.). American Water Works Association. 2004. pp. 1–14. ISBN 1-58321-311-2.

- Nicholson JW, Czarnecka B (2008). "Fluoride in dentistry and dental restoratives". In Tressaud A, Haufe G (eds.) (ed.). Fluorine and Health. Elsevier. pp. 333–78. ISBN 978-0-444-53086-8.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - Division of Oral Health, National Center for Prevention Services, CDC (1993). "Fluoridation census 1992" (PDF). Retrieved December 29, 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1995). "Engineering and administrative recommendations for water fluoridation, 1995". MMWR Recomm Rep. 44 (RR-13): 1–40. PMID 7565542.

- ^ Bailey W, Barker L, Duchon K, Maas W (2008). "Populations receiving optimally fluoridated public drinking water—United States, 1992–2006". MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 57 (27): 737–41. PMID 18614991.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Lalumandier JA, Ayers LW (2000). "Fluoride and bacterial content of bottled water vs tap water". Arch Fam Med. 9 (3): 246–50. doi:10.1001/archfami.9.3.246. PMID 10728111.

- Grec RHdC, de Moura PG, Pessan JP, Ramires I, Costa B, Buzalaf MAR (2008). "Fluoride concentration in bottled water on the market in the municipality of São Paulo". Rev Saúde Pública. 42 (1): 154–7. doi:10.1590/S0034-89102008000100022. PMID 18200355.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Featherstone JD (2008). "Dental caries: a dynamic disease process". Aust Dent J. 53 (3): 286–91. doi:10.1111/j.1834-7819.2008.00064.x. PMID 18782377.

- ^ Cury JA, Tenuta LM (2008). "How to maintain a cariostatic fluoride concentration in the oral environment". Adv Dent Res. 20 (1): 13–6. doi:10.1177/154407370802000104. PMID 18694871.

- Koo H (2008). "Strategies to enhance the biological effects of fluoride on dental biofilms". Adv Dent Res. 20 (1): 17–21. doi:10.1177/154407370802000105. PMID 18694872.

- Marquis RE, Clock SA, Mota-Meira M (2003). "Fluoride and organic weak acids as modulators of microbial physiology". FEMS Microbiol Rev. 26 (5): 493–510. doi:10.1016/S0168-6445(02)00143-2. PMID 12586392.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Aoba T, Fejerskov O (2002). "Dental fluorosis: chemistry and biology". Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 13 (2): 155–70. doi:10.1177/154411130201300206. PMID 12097358.

- Bruvo M, Ekstrand K, Arvin E; et al. (2008). "Optimal drinking water composition for caries control in populations". J Dent Res. 87 (4): 340–3. doi:10.1177/154405910808700407. PMID 18362315.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sheiham A (2001). "Dietary effects on dental diseases" (PDF). Public Health Nutr. 4 (2B): 569–91. doi:10.1079/PHN2001142. PMID 11683551.

- ^ Division of Oral Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC (1999). "Achievements in public health, 1900–1999: Fluoridation of drinking water to prevent dental caries". MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 48 (41): 933–40.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Contains H. Trendley Dean, D.D.S. Reprinted in: JAMA. 283 (10): 1283–6. 2000. doi:10.1001/jama.283.10.1283. PMID 10714718.{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Worthington H, Clarkson J (2003). "The evidence base for topical fluorides". Community Dent Health. 20 (2): 74–6. PMID 12914024.

- ^ Truman BI, Gooch BF, Sulemana I; et al. (2002). "Reviews of evidence on interventions to prevent dental caries, oral and pharyngeal cancers, and sports-related craniofacial injuries" (PDF). Am J Prev Med. 23 (1 Suppl): 21–54. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(02)00449-X. PMID 12091093. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Hausen HW (2000). "Fluoridation, fractures, and teeth". BMJ. 321 (7265): 844–5. PMC 1118662. PMID 11021844.

- ^ Kumar JV (2008). "Is water fluoridation still necessary?". Adv Dent Res. 20 (1): 8–12. doi:10.1177/154407370802000103. PMID 18694870.

- Zina LG, Hujoel P, Moimaz SAS, Cunha-Cruz J (2008). "Infant formula and fluorosis: a systematic review". J Dent Res. 87 (Spec Iss B): 1144.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) (Abstract.) - Fawell J, Bailey K, Chilton J, Dahi E, Fewtrell L, Magara Y (2006). "Human health effects". Fluoride in Drinking-water (PDF). World Health Organization. pp. 29–36. ISBN 92-4-156319-2. Retrieved February 28, 2009.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Fawell J, Bailey K, Chilton J, Dahi E, Fewtrell L, Magara Y (2006). "Guidelines and standards". Fluoride in Drinking-water (PDF). World Health Organization. pp. 37–9. ISBN 92-4-156319-2. Retrieved February 18, 2009.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Balbus JM, Lang ME (2001). "Is the water safe for my baby?". Pediatr Clin North Am. 48 (5): 1129–52, viii. PMID 11579665.

- ^ Pollick HF (2004). "Water fluoridation and the environment: current perspective in the United States" (PDF). Int J Occup Environ Health. 10 (3): 343–50. PMID 15473093. Retrieved December 29, 2008.

- Macek MD, Matte TD, Sinks T, Malvitz DM (2006). "Blood lead concentrations in children and method of water fluoridation in the United States, 1988–1994". Environ Health Perspect. 114 (1): 130–4. doi:10.1289/ehp.8319. PMC 1332668. PMID 16393670.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Milgrom P, Reisine S (2000). "Oral health in the United States: the post-fluoride generation". Annu Rev Public Health. 21: 403–36. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.21.1.403. PMID 10884959.

- ^ Goldman AS, Yee R, Holmgren CJ, Benzian H (2008). "Global affordability of fluoride toothpaste". Global Health. 4: 7. doi:10.1186/1744-8603-4-7. PMC 2443131. PMID 18554382.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Bánóczy J, Rugg-Gunn AJ (2006). "Milk—a vehicle for fluorides: a review" (PDF). Rev Clin Pesq Odontol. 2 (5–6): 415–26. Retrieved January 3, 2009.

- Yeung CA, Hitchings JL, Macfarlane TV, Threlfall AG, Tickle M, Glenny AM (2005). "Fluoridated milk for preventing dental caries". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3): CD003876. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003876.pub2. PMID 16034911.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Reeves A, Chiappelli F, Cajulis OS (2006). "Evidence-based recommendations for the use of sealants" (PDF). J Calif Dent Assoc. 34 (7): 540–6. PMID 16995612.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - The British Fluoridation Society; The UK Public Health Association; The British Dental Association; The Faculty of Public Health (2004). "The ethics of water fluoridation". One in a Million: The facts about water fluoridation (2nd ed.). pp. 88–92. ISBN 095476840X.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ADA Council on Access, Prevention and Interprofessional Relations (2005). "National and international organizations that recognize the public health benefits of community water fluoridation for preventing dental decay". American Dental Association. Retrieved December 22, 2008.

- Petersen PE (2008). "World Health Organization global policy for improvement of oral health—World Health Assembly 2007" (PDF). Int Dent J. 58 (3): 115–21. doi:10.1680/indj.2008.58.3.115. PMID 18630105. Retrieved December 22, 2008.

- Carmona RH (July 28, 2004). "Surgeon General's statement on community water fluoridation" (PDF). U.S. Public Health Service. Retrieved December 22, 2008.

- Australian Dental Association (2004). "Community oral health promotion: fluoride use" (PDF). Retrieved January 15, 2009.

- Canadian Dental Association (2008). "CDA position on use of fluorides in caries prevention" (PDF). Retrieved January 15, 2009.

- ADA Council on Access, Prevention and Interprofessional Relations (2005). "Fluoridation facts" (PDF). American Dental Association. Retrieved December 22, 2008.

- Carstairs C, Elder R (2008). "Expertise, health, and popular opinion: debating water fluoridation, 1945–80". Can Hist Rev. 89 (3): 345–71. doi:10.3138/chr.89.3.345.

- Newbrun E (1996). "The fluoridation war: a scientific dispute or a religious argument?". J Public Health Dent. 56 (5 Spec No): 246–52. doi:10.1111/j.1752-7325.1996.tb02447.x. PMID 9034969.

- ^ Reilly GA (2007). "The task is a political one: the promotion of fluoridation". In Ward JW, Warren C (ed.). Silent Victories: The History and Practice of Public Health in Twentieth-century America. Oxford University Press. pp. 323–42. ISBN 0-19-515069-4.

- Nordlinger J (June 30, 2003). "Water fights: believe it or not, the fluoridation war still rages—with a twist you may like". Natl Rev. Retrieved January 19, 2009.

- Griffin M, Shickle D, Moran N (2008). "European citizens' opinions on water fluoridation". Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 36 (2): 95–102. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0528.2007.00373.x. PMID 18333872.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Dixon S, Shackley P (1999). "Estimating the benefits of community water fluoridation using the willingness-to-pay technique: results of a pilot study". Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 27 (2): 124–9. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0528.1999.tb02001.x. PMID 10226722.

- Calman K (2009). "Beyond the 'nanny state': stewardship and public health". Public Health. 123 (1): e6 – e10. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2008.10.025. PMID 19135693.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|laydate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help) - Martin B (1989). "The sociology of the fluoridation controversy: a reexamination". Sociol Q. 30 (1): 59–76. doi:10.1111/j.1533-8525.1989.tb01511.x.

- ^ The British Fluoridation Society; The UK Public Health Association; The British Dental Association; The Faculty of Public Health (2004). "The extent of water fluoridation". One in a Million: The facts about water fluoridation (2nd ed.). pp. 55–80. ISBN 095476840X.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Division of Oral Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC (September 17, 2008). "Water fluoridation statistics for 2006". Retrieved December 22, 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Williams BL, Florez Y, Pettygrove S (2001). "Inter- and intra-ethnic variation in water intake, contact, and source estimates among Tucson residents: Implications for exposure analysis". J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 11 (6): 510–21. doi:10.1038/sj.jea.7500192. PMID 11791167.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Douglas WA (1959). History of Dentistry in Colorado, 1859–1959. Denver: Colorado State Dental Assn. p. 199. OCLC 5015927.

- Crichton-Browne J (1892). "An address on tooth culture". Lancet. 140 (3592): 6–10. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)97399-4.

- Eckardt (1874). "Kali fluoratum zur Erhaltung der Zähne". Der praktische Arzt (in German). 15 (3): 69–70.

- Colorado Brown Stain:

- Peterson J (1997). "Solving the mystery of the Colorado Brown Stain". J Hist Dent. 45 (2): 57–61. PMID 9468893.

- "The discovery of fluoride". Colorado Springs Dental Society. 2004. Retrieved January 8, 2009.

- ^ Mullen J (2005). "History of water fluoridation". Br Dent J. 199 (7s): 1–4. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.4812863. PMID 16215546.

- ^ Lennon MA (2006). "One in a million: the first community trial of water fluoridation". Bull World Health Organ. 84 (9): 759–60. doi:10.1590/S0042-96862006000900020. PMID 17128347.

- Dean HT, Arnold FA, Jay P, Knutson JW (1950). "Studies on mass control of dental caries through fluoridation of the public water supply". Public Health Rep. 65 (43): 1403–8. PMC 1997106. PMID 14781280.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Akers HF (2008). "Collaboration, vision and reality: water fluoridation in New Zealand (1952–1968)" (PDF). N Z Dent J. 104 (4): 127–33. PMID 19180863. Retrieved March 5, 2009.

- Buzalaf MA, de Almeida BS, Olympio KPK, da S Cardoso VE, de CS Peres SH (2004). "Enamel fluorosis prevalence after a 7-year interruption in water fluoridation in Jaú, São Paulo, Brazil". J Public Health Dent. 64 (4): 205–8. doi:10.1111/j.1752-7325.2004.tb02754.x. PMID 15562942.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)