| Revision as of 20:47, 27 May 2009 editJayen466 (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Page movers, Mass message senders, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers56,627 edits Undid revision 292725023 by 84.190.177.193 (talk) rvt ungrammatical + misspelt; no significant difference in meaning← Previous edit | Revision as of 21:23, 27 May 2009 edit undoWispanow (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers2,833 edits Still a POV text, see reasons given and discussion.Next edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| ] | {{POV}}] | ||

| '''Scientology''' has been present '''in Germany''' since 1970. Though the ] is considered legal in Germany, it has encountered particular antagonism by the German press and government. The German courts have so far not resolved whether ] should be accorded the legal status of a religious or worldview community and various courts have come to contradictory conclusions.<ref name="BundestagRFRW"/> The ] does not recognize Scientology as a religion, and regards some of the goals of Scientology as conflicting with the ]. Germany has been criticized over its stance towards Scientology, notably by the ].<ref>Barber, Tony (1997-01-30). , '']''</ref><ref name=KentFGA/><ref name="USS1999"/> | '''Scientology''' has been present '''in Germany''' since 1970. Though the ] is considered legal in Germany, it has encountered particular antagonism by the German press and government. The German courts have so far not resolved whether ] should be accorded the legal status of a religious or worldview community and various courts have come to contradictory conclusions.<ref name="BundestagRFRW"/> The ] does not recognize Scientology as a religion, and regards some of the goals of Scientology as conflicting with the ]. Germany has been criticized over its stance towards Scientology, notably by the ].<ref>Barber, Tony (1997-01-30). , '']''</ref><ref name=KentFGA/><ref name="USS1999"/> | ||

Revision as of 21:23, 27 May 2009

| The neutrality of this article is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please do not remove this message until conditions to do so are met. (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Scientology has been present in Germany since 1970. Though the Church of Scientology is considered legal in Germany, it has encountered particular antagonism by the German press and government. The German courts have so far not resolved whether Scientology should be accorded the legal status of a religious or worldview community and various courts have come to contradictory conclusions. The German government does not recognize Scientology as a religion, and regards some of the goals of Scientology as conflicting with the German constitution. Germany has been criticized over its stance towards Scientology, notably by the United States government.

The Scientology controversy

Main article: Scientology controversies See also: Scientology as a state-recognized religionScientology, founded in the early 1950s in the United States by L. Ron Hubbard and today claiming to be represented in 150 countries, has been a very controversial new religious movement. Scientology teaches that the source of people's unhappiness lies in "engrams", psychological burdens acquired in the course of painful experiences, which can be cleared through a type of counselling called "auditing", made available by the Church of Scientology on a fee-for-service basis. The movement's utopian aim is to "clear the planet", to create a world in which every individual has overcome their psychological limitations.

The financial aspect that ties self-improvement to donations has brought controversy to Scientology throughout much of its history, with governments classing it as a profit-making enterprise rather than as a religion. Critics maintain that Scientology is "a business-driven, psychologically manipulative, totalitarian ideology with world-dominating aspirations," and that it tricks its members into parting with significant sums of money for Scientology courses. Scientology has fought innumerable lawsuits to defend itself against such charges and to pursue legal recognition as a religion. These efforts have been partly successful – Scientology has gained recognition as a tax-exempt religious group in a number of countries, most notably in Australia in 1983 and the United States in 1993, and in 2007 won an important case at the European Court of Human Rights, which censured Russia for failing to register Scientology as a religion.

Scientology presence in Germany

Scientology first established a presence in Germany in 1970. In 2007 there were ten Scientology Churches located in Germany's major cities, as well as fourteen Scientology Missions. Cities with major Scientology bases include Munich, Hamburg, Berlin, Düsseldorf, Frankfurt am Main, Hanover and Stuttgart. There are nine missions in Baden-Württemberg, and three in Bavaria.

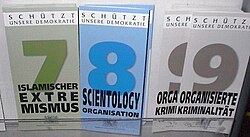

Germany's domestic intelligence service, the German Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution (Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz, or BfV), estimates that there are between 5,000 and 6,000 Scientologists in Germany and reports that membership has remained stable at that level for many years. The Church of Scientology reports around 30,000 members.

Public opposition to Scientology in Germany

Germany has taken a very strong stance against Scientology. In part, this may be related to Germany's past and its concerns over any organization perceived to seek a dominant position in society.

Scientology is generally seen as a Sekte (cult or sect) in Germany, rather than as a religion. German public concerns about the alleged dangers posed by cults date back to the early 1970s, when there was widespread debate about "youth religions" such as the Unification Church, ISKCON, Children of God, and the Divine Light Mission. The most prominent critics of these new religious movements were the "sect experts" (Sektenbeauftragte) of Germany's Protestant Churches, who were also active in promoting the establishment of private "initiatives of parents and concerned persons".

Aktion Bildungsinformation ("Educational Information Campaign"), an organisation warning the public to avoid Scientology, was established in the 1970s. It filed successful lawsuits against the Church of Scientology over its proselytising in public places, and published an influential book, The Sect of Scientology and its Front Organisations. In 1981, the organisation's founder, Ingo Heinemann, became the director of Aktion für geistige und psychische Freiheit ("Campagin for Intellectual and Psychic Freedom"), the most prominent German anti-cult organisation. Together with the churches' sect experts, private anti-cult initiatives have shaped German public opinion.

Fueled by events such as the Waco Siege in 1993, the murders and suicides associated with the Order of the Solar Temple, and the 1995 Aum Shinrikyo incidents in Japan, concerns in Germany about the potential dangers posed by new religious movements reached the level of hysteria in the mid-nineties, becoming focused mainly on the Church of Scientology. Perceptions that Scientology had a totalitarian character were reinforced when Robert Vaughn Young, an American ex-Scientologist and former PR official in the Church of Scientology, visited German officials in late 1995 and wrote an article in Der Spiegel, characterising Scientology as a totalitarian system which operated a gulag (the Rehabilitation Project Force) for members of Scientology's Sea Org who had been found guilty of transgressions.

According to religious scholar Hubert Seiwert, Scientology was seen as a "serious political danger that not only threatened to turn individuals into will-less zombies, but was also conspiring to overthrow the democratic constitution of the state." Seiwert argues that the view of Scientology as a public enemy became a matter of political correctness: senior political figures were involved in launching campaigns against it, and being suspected of any association with it resulted in social ostracism. Stephen A. Kent, writing in 1998, noted that the insistence that Scientology should be suppressed was present among officials at all levels of the German government. Between 1996 and 1998, government publications on Scientology proliferated, with courts backing the publications by holding that these efforts did not interfere with religious freedom, but merely reflected the government's responsibility to keep the public informed. An Enquete Commission to investigate sects and similar groups was launched by the German parliament in 1996, in large part because of public concerns about Scientology.

In early 2008, Thomas Gandow, a prominent spokesperson on sects for the German Lutheran Church, and the historian Guido Knopp both likened the Scientologist Hollywood actor Tom Cruise to Goebbels, the Nazi propaganda minister. Gandow and Knopp cited a leaked Scientology video in which Cruise was seen asking the audience whether Scientologists should "clean up" the world, the audience responding with enthusiastic cheers – cheers which Gandow and Knopp felt were reminiscent of the audience's response to Goebbels' famous question, "Do you want total war?" Gandow's and Knopp's comments found few critics in Germany, which in recent decades has viewed ideological movements with great suspicion. Most Germans consider Scientology a subversive organization, with popular support for banning the Church running at 67% according to a September 2008 poll published in Der Spiegel.

Legal status

While there have been calls for Scientology to be banned, the Church of Scientology remains legal in Germany and is allowed to operate there. Its precise legal status however is unresolved. Two points are contested: first, whether or not the teachings of Scientology qualify as a "religion or worldview" (Religion or Weltanschauung; these are equal before German law), and secondly, whether or not these teachings are only used as a pretext for purely commercial activity; if the latter were the case, this would most likely imply that Scientology would not qualify for protection as a "religious or worldview community" (Religions- oder Weltanschauungsgemeinschaft) under Article 4 of the German constitution, which guarantees the freedom of belief, religion and worldview. Status as a "religious or worldview community" also affects a broad range of other issues in Germany, such as taxation and freedom of association.

The Federal Court of Justice of Germany has not yet made an explicit decision on the matter, but implicitly assumed in 1980 that Scientology represented a religious or worldview community. The Upper Administrative Court in Hamburg explicitly asserted in 1994 that Scientology should be viewed as a worldview community. In 1995, the Federal Labor Court of Germany decided that the Church of Scientology did not represent a religious or worldview community entitled to protection under Article 4 of the German Constitution, although another decision by the same court left the question open again in 2003. In a 2003 decision, the Administrative Court of Baden-Württemberg in Mannheim did not endorse the view that the teachings of Scientology merely serve as a pretext for commercial activity. The Federal Administrative Court of Germany in 2005 explicitly granted a Scientologist protection under Article 4.1 of the German Constitution, which declares the freedom of religion and worldview inviolate. The German government does not consider the Church of Scientology to be a religious or worldview community and asserts that Scientology is a profit-making enterprise, rather than a religion.

The judicial system operates with a fair degree of autonomy in Germany, and recent years have seen a number of court decisions in Scientology's favour, despite the very widespread negative attitude to Scientology among politicians and the general population.

Monitoring by the German domestic intelligence services

Because of the history of the rise to power of Nazism in Germany in the 1930s, the present German state has committed itself to taking active steps to prevent the rise of any ideology that threatens the values enshrined in the German constitution. The BfV domestic intelligence service, whose brief is to protect the German constitution, regards the aims of Scientology as running counter to Germany's free and democratic order, and has been monitoring Scientology in a number of German states since 1997. Minister for Family Policy Claudia Nolte instituted the surveillance, saying that the church had totalitarian tendencies and that she would oppose Scientology with all means at her disposal.

The German Church of Scientology has repeatedly challenged the legality of this surveillance in court. In December 2001, the Administrative Court in Berlin ruled against the Berlin Office for the Protection of the Constitution and ordered it to stop the recruitment and deployment of staff and members of the Church of Scientology Berlin as paid informants. The court ruled that the use of informants was disproportionate. In 2003, the same court ruled that it was illegal for the Berlin Office for the Protection of the Constitution to include the activities of Scientology in its report, given that the report did not document any activities that were opposed to the constitution.

At the federal level, Scientology lost a complaint against continued surveillance by the BfV in November 2004. The federal court based its opinion on its judgment that the aims of Scientology, as outlined by L. Ron Hubbard in his writings, were incompatible with the German constitution. Lawyers acting for the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution had accused Scientology of harboring designs on Germany's free, democratic basic order. They said that Hubbard had written that civil rights, for example, should be restricted to Scientologists, and they asserted that the Scientology organization was taking systematic steps to infiltrate society and government institutions, in order to prevent anti-Scientology legislation. Opposing counsel acting for the Church of Scientology had contended that Scientology was non-political, its aims were the liberation of the human being, and that Hubbard's instructions were valid only within the Church of Scientology and were subject to interpretation, and at any rate there was no effort to implement these instructions in Germany. The court disagreed and ruled that many sources, some of them not accessible to the general public, indicated that the aims of the Church of Scientology did include the abrogation of the principle of equality and other essential human rights.

In Saarland, surveillance was stopped by a court as inappropriate in 2005, because there is no local branch of Scientology and few members. As of 6 May 2008, the Church of Scientology in Germany dropped the legal battle to prevent surveillance of its activities by the BfV after the North Rhine-Westphalia Higher Administrative Court in Münster refused to hear an appeal on the matter. Being suspected of maintaining "ambitions against the free, democratic basic order", the Scientology organization added a declaration on human rights and democracy to its bylaws.

There is at least one example of surveillance of Scientology by the German intelligence services outside of Germany. In 1998, the Swiss government detained an agent of the German government, charging him with "carrying out illegal business for a foreign state, working for a political information service and falsifying identity documents". The man had allegedly contacted Susanne Haller, a member of the city council of Basel, where the Church of Scientology operates a mission. The German government posted bail for the agent. He was eventually given a 30-day suspended jail sentence for spying on Scientology, and the German government apologized to Switzerland for the incident.

"Sect filters"

A "sect filter" is a document that requires an applicant to acknowledge any association with a sect or new religious movement before being accepted for a position of employment. German government agencies have drafted such sect filters for use by businesses; they are primarily used against Scientologists, establishing discrimination against Scientologists in employment. In addition, various local governments operate "sect commissioner's" offices. The city of Hamburg has set up a full-time office dedicated to opposing Scientology, the Scientology Task Force for the Hamburg Interior Authority, under the leadership of Ursula Caberta.

Due to concerns about possible government infiltration by Scientologists, applicants for civil service positions in Bavaria are required to declare whether or not they are Scientologists, and a similar policy has been instituted in Hesse. Scientologists are also banned from joining major political parties in Germany such as the Christian Democratic Union, the Christian Social Union of Bavaria, the Social Democratic Party of Germany and the Free Democratic Party. Existing Scientologist members of these parties have been "purged", according to Time Magazine. According to Eileen Barker, a professor of sociology at the London School of Economics, "Germany has gone further than any other Western European country in restricting the civil rights of Scientologists."

When it became known that Microsoft's Windows 2000 operating system included a disk defragmenter developed by Executive Software International (a company headed by a Scientologist), this caused concern among German government officials and clergy over potential security issues. To assuage these concerns, Microsoft Germany agreed to provide a means to disable the utility.

Aborted initiative to ban Scientology

In March 2007, it was reported that German authorities were increasing their efforts to monitor Scientology in response to the opening of a new Scientology headquarters in Berlin. On December 7, 2007, German federal and state interior ministers expressed the opinion that the Scientology organization was continuing to pursue anti-constitutional goals, restricting "essential basic and human rights like the dignity of man or the right to equal treatment," and asked Germany's domestic intelligence agencies to collect and evaluate the information required for a possible judicial inquiry aimed at banning the organization.

The move was criticized by German politicians from all sides of the political spectrum, with legal experts expressing concern that an attempt to ban the organization would likely fail in the courts. This view was echoed by the German intelligence agencies, who warned that a ban would be doomed to fail. Sabine Weber, president of the Church of Scientology in Berlin, called the accusations "unrealistic" and "absurd" and said that the German interior ministers' evaluation was based "on a few sentences out of 500,000 pages of Scientological literature." She added, "I can also find hundreds of quotes in the Bible that are totalitarian but that doesn't mean I will demand the ban of Christianity."

In November 2008, the government abandoned its attempts to ban Scientology, after finding insufficient evidence of illegal or unconstitutional activity. The report by the BfV cited knowledge gaps and noted several points that would make the success of any legal undertaking to ban Scientology doubtful. First, the BfV report stated there was no evidence that Scientology could be viewed as a foreign organisation; there were German churches and missions, a German board, German bylaws, and no evidence that the organisation was "totally remote-controlled" from the United States. A foreign organisation would have been much easier to ban than a German one. The second argument on which those proposing the ban had counted was Scientology's aggressive opposition to the constitution. Here, the report found that Scientology's behaviour gave no grounds to assume that Scientology aggressively sought to attack and overthrow Germany's free and democratic basic order. "Neither its bylaws nor any other utterances" supported the "conclusion that the organisation had criminal aims." The BfV also considered whether there were grounds to act against the Church of Scientology on the basis that they were practising medicine without a licence, but expressed doubts that a court would accept this reasoning.

Commenting on the decision to drop the ban attempt, Ehrhart Körting, Berlin's interior minister, said, "This organization pursues goals – through its writings, its concept and its disrespect for minorities – that we cannot tolerate and that we consider in violation of the constitution. But they put very little of this into practice. The appraisal of the Government at the moment is that is a lousy organization, but it is not an organization that we have to take a hammer to." The Church of Scientology expressed satisfaction with the decision, describing it as the "only one possible". Monitoring of Scientology's activities by the German intelligence services continues.

Criticism of Germany's stance

The United States media, while generally reporting negatively on Scientology in domestic news, has taken an at least partially supportive stance towards Scientology in relation to Germany. Richard Cohen for example, writing in the Washington Post, said in 1996: "Scientology might be one weird religion, but the German reaction to it is weirder still – not to mention disturbing."

The U.S. Department of State has repeatedly claimed that Germany's actions constitute government and societal discrimination against minority religious groups – within which it includes Scientology – and expressed its concerns over the violation of Scientologists' individual rights posed by sect filters. It has also warned that companies and artists associated with Scientology may be subject to "government-approved discrimination and boycotts" in Germany. Past targets of such actions have included actors Tom Cruise and John Travolta, as well as jazz pianist Chick Corea.

In 1997, an open letter to then-Chancellor Helmut Kohl, published as a newspaper advertisement in the International Herald Tribune, drew parallels between the "organized oppression" of Scientologists in Germany and Nazi policies espoused by Germany in the 1930s. The letter was conceived and paid for by Hollywood lawyer Bertram Fields, and signed by 34 prominent figures in the U.S. entertainment industry, including the top executives of MGM, Warner Bros., Paramount, Universal and Sony Pictures Entertainment as well as actors Dustin Hoffman and Goldie Hawn, director Oliver Stone, writers Mario Puzo and Gore Vidal and talk-show host Larry King. It echoed similar parallels drawn by the Church of Scientology itself, which until then had received scant notice.

Chancellor Kohl, commenting on the letter, said that those who signed it "don't know a thing about Germany and don't want to know." German officials argued that "the whole fuss was cranked up by the Scientologists to achieve what we won't give them: tax-exempt status as a religion. This is intimidation, pure and simple." Officials explained that precisely because of Germany's Nazi past, Germany took a determined stance against all "radical cults and sects, including right-wing Nazi groups", and not just against Scientology. The response from Kohl's Christian Democratic Union party was to denounce the letter as "absurd" and cite previous German court rulings stating that Scientology had primarily economic goals and could legitimately be referred to using phrases such as a "contemptuous cartel of oppression".

A U.S. Department of State spokesman rejected the Nazi comparisons in the open letter as "outrageous" and distanced the U.S. government from Nazi comparisons made by the Church of Scientology, saying, "We have criticized the Germans on this, but we aren't going to support the Scientologists' terror tactics against the German government."

In late 1997, the United States granted asylum to a German Scientologist who claimed she would be subject to religious persecution in her homeland. In 2000, the German Stern magazine published a report asserting that several rejection letters which the woman had submitted as part of her asylum application – ostensibly from potential employers who were rejecting her because she was a Scientologist – had in fact been written by fellow Scientologists at her request and that of the Office of Special Affairs, and that she was in personal financial trouble and about to go on trial for tax evasion at the time she applied for asylum. On a 2000 visit to Clearwater, Florida, Ursula Caberta of the Scientology Task Force for the Hamburg Interior Authority likewise alleged that the asylum case had been part of an "orchestrated effort" by Scientology undertaken "for political gain", and "a spectacular abuse of the U.S. system". German expatriate Scientologists resident in Clearwater, in turn, accused Caberta of stoking a "hate campaign" in Germany that had "ruined the lives and fortunes of scores of Scientologists" and maintained that Scientologists had not "exaggerated their plight for political gain in the United States." Mark Rathbun, a top Church of Scientology official, said that although Scientology had not orchestrated the case, "there would have been nothing improper if it had."

A United Nations report in April 1998 asserted that individuals in Germany were discriminated against because of their affiliation with Scientology. However, it rejected the comparison of the treatment of Scientologists with that of Jews during the Nazi era.

References

- ^ bundestag.de: Legal questions concerning religious and worldview communities, prepared by the Scientific Services staff of the German Parliament Template:Languageicon

- Barber, Tony (1997-01-30). Germany is harassing Scientologists, says US, The Independent

- ^ Kent, Stephen A. (2001). "The French and German versus American Debate over 'New Religions', Scientology, and Human Rights". Marburg Journal of Religion. 6 (1). Retrieved 2009-02-21.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ U.S. Department of State – International Religious Freedom Report 1999: Germany

- ^ Lewis, James R. (2009), Scientology, New York, NY: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-533149-3, p. 283

- ^ Lewis, James R. (2009), Scientology, New York, NY: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-533149-3, p. 316

- Melton, J. Gordon (2000). The Church of Scientology. Salt Lake City: Signature Press. pp. 53–64. ISBN 1-56085-139-2.

- Beit-Hallahmi, Benjamin: "Scientology: Religion or racket?", Marburg Journal of Religion, Vol. 8, No. 1 (September 2003

- ^ Kent, Stephen A. (1999). "The Globalization of Scientology – Influence, Control, and Opposition in Transnational Markets". Religion. 29: 147–169. Retrieved 2009-04-25.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Lewis, James R. (2009), Scientology, New York, NY: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-533149-3, pp. 286–288

- ^ Staff (2007-12-07). "Innenminister erwägen Verbot – 'Scientology unvereinbar mit dem Grundgesetz'", Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung Template:De icon

- ^ Staff (2007-01-15). "Organisation mit bundesweit 5000 Anhängern", Berliner Morgenpost Template:De icon

- ^ Staff (2007-06-24). "Scientology", Berliner Morgenpost Template:De icon

- Staff (2008-11-21). "Kein Verbotsverfahren gegen die Scientology-Organisation", Deutsche Welle

- "Scientology Threatens German Security, Intelligence Chief Says". Deutsche Presse-Agentur. 13 March 1998.

- ^ Lewis, James R. (2009), Scientology, New York, NY: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-533149-3, p. 289

- ^ Cieply, Michael; Landler, Mark (2007-06-30). "Plot Thickens in a Tom Cruise Film, Long Before the Cameras Begin to Roll", New York Times

- ^ Seiwert, H. (2004), "The German Enquete Commission: Political Conflicts and Compromises", in Richardson, James T. (ed.) (2004), Regulating Religion: Case Studies from Around the Globe, New York, NY: Luwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, ISBN 0306478870, pp. 85–94

- ^ Melton, J. Gordon (2000). The Church of Scientology. Salt Lake City: Signature Press. pp. 61–62. ISBN 1-56085-139-2.

- Beckford, James A. (Autumn 1981). "Cults, Controversy and Control: A Comparative Analysis of the Problems Posed by New Religious Movements in the Federal Republic of Germany and France". Sociological Analysis. 42 (3): 249–263.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Smee, Jess (2008-01-21). "German historian likens Cruise speech to Goebbels", The Guardian

- ^ Bonfante, Jordan; van Voorst, Bruce (1997-02-10). "Does Germany Have Something Against These Guys?", Time

- ^ Fröhlingsdorf, Michael; Stark, Holger (2008-09-22). "Verfassungsschutz: Kampf ums Bushäuschen", Der Spiegel, 39/2008 Template:De icon

- Staff (2003-12-12). "Urteil: Scientology ist kein Wirtschaftsbetrieb", domradio.de (website of the Cologne archdiocese radio station) Template:De icon

- Press statement of the Administrative Court of Baden-Württemberg (2003-12-12). Entziehung der Rechtsfähigkeit des Vereins "Scientology Gemeinde Baden-Württemberg e.V." nicht rechtens Template:De icon

- Zacharias, Diana (2006-10-01). "Protective Declarations Against Scientology as Unjustified Detriments to Freedom of Religion: A Comment on the Decision of the German Federal Administrative Court of 15 December 2005", German Law Journal, Volume 7, No. 10

- BVerwG Az.: 7 C 20.04, 15 December 2005 Template:Languageicon

- ^ Frantz, Douglas (1997-11-08). "U.S. Immigration Court Grants Asylum to German Scientologist", New York Times

- ^ Walker, Ruth (1996-11-18). "Germany's Probe Into 'Sects' Raises Religious-Freedom Issues", The Christian Science Monitor

- Stephen A. Kent (2008-04-16). "Scientology, Hollywood and the path to Washington" (interview), The Religion Report, ABC Radio National

- ^ Hering, Lars (2004-11-11). "Scientology darf weiter beobachtet werden", Kölnische Rundschau Template:De icon

- Report of the German federal Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz intelligence agency Template:De icon

- Hendon, David W. (1996). "Notes on Church-State Affairs:Germany". Journal of Church & State. 38 (2): 445.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|laydate=,|laysummary=,|day=, and|laysource=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Staff (2001-12-14). "Keine V-Leute", Berliner Zeitung, p. 12 Template:De icon

- Berlin Administrative Court Rules Against the Use of Undercover Agents Posing as Scientologists by German Intelligence in Its Scientology-Watching Activities (Dec. 13, 2001): Court's Press Release in German, with English Translation Template:De icon / Template:En icon

- Besier, Gerhard (2004). Zeitdiagnosen: Religionsfreiheit und Konformismus. Über Minderheiten und die Macht der Mehrheit. Münster, Germany: Lit Verlag. p. 213. ISBN 3825876543.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) Template:De icon - Staff (2003-12-05). "Verfassungsgericht weist Klage von Scientology gegen Beobachtung ab". Berliner Morgenpost Template:De icon

- Bavarian Office for the Protection of the Constitution. Reports/Publications Template:De icon

- ^ Staff (2005-04-27). "Scientology darf nicht mehr ausspioniert werden", Spiegel Online Template:De icon

- ^ Staff (2008-05-07). "German Scientology church drops court challenge; adds human rights declaration to bylaws", AP/Arab Times

- ^ Staff (1998-04-09). "Germany apologises to Switzerland for spying on Scientologists", BBC

- Staff (1998-06-23). "German charged with spying on Scientologists", BBC

- Hendon, David W. (1998). "Notes on Church-State Affairs: Germany". Journal of Church & State. 40 (3): 714.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|laydate=,|laysummary=,|day=, and|laysource=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Switzerland: Scientology Spying by a German Official Spurs Jail Term (AP, 1999-12-01)

- ^ Shupe, Anson (2006). Agents of Discord. New Brunswick (U.S.A.), London (U.K.): Transaction Publishers. p. 231. ISBN 0-7658-0323-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Melton, J. Gordon (2000). The Church of Scientology. Salt Lake City: Signature Press. p. 62. ISBN 1-56085-139-2.

- ^ Cohen, Richard (1996-11-15). "Germany's Odd Obsession With Scientology", Washington Post

- Staff (2006-09-15). "USA finden Deutschland zu intolerant", Der Spiegel Template:De icon

- ^ Haddadin, Haitham (2000-11-06). "Scientologist-software man blasts Germany", Independent Online

- Stark, Holger (2007-03-27). "Scientology's New European Offensive: The March of the 'Orgs'". Der Spiegel. Retrieved 2007-11-12.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Staff (2007-12-08). "Scientology – Zweifel an Verbotsplänen", Tagesspiegel Template:Languageicon

- Sammlung der zur Veröffentlichung freigegebenen Beschlüsse der 185. Sitzung der Ständigen Konferenz der Innenminister und -senatoren der Länder am 7. Dezember 2007 in Berlin (German interior ministers' conference resolutions released for publication, 2007-12-07) Template:Languageicon

- ^ Grieshaber, Kirsten (2007-12-09). German official seeks ban on Scientology, USA Today / AP

- Solms-Laubach, Franz (2007-12-07). "Innenminister fordern Verbot von Scientology", Die Welt Template:Languageicon

- Staff (2007-12-10). "Lack of Evidence: Agencies Warn Scientology Ban Doomed to Fail". Der Spiegel. Retrieved 2007-12-18.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ (2008-11-21). "Germany drops attempt to ban Scientology", CBC News / AP

- Staff (2007-12-03). "Hamburg strebt Scientology-Verbot an", Netzeitung/AP Template:De icon

- ^ Fischer, Michael (2008-11-23). "Germany abandons bid to ban Scientology", The Age

- ^ Staff (2007-07-09). "Stauffenberg-Film: Rückendeckung aus Hollywood", Die Zeit Template:De icon

- Moore, Tristana (2008-01-13). "Scientologists in German push", BBC

- Paterson, Tony (2007-07-23). "Cruise is 'Goebbels of Scientology', says German church", The Independent

- ^ Schön, Brigitte (January 2001): "Framing Effects in the Coverage of Scientology versus Germany: Some Thoughts on the Role of Press and Scholars", Marburg Journal of Religion, Volume 6, No. 1

- Lehmann, Hartmut (2004). Koexistenz und Konflikt von Religionen im Vereinten Europa, Wallstein Verlag, ISBN 3892447462, pp. 68–71 Template:De icon / Template:En icon

- ^ "Germany, America and Scientology", Washington Post, February 1, 1997

- Frantz, Douglas (1997-03-09). "Scientology's Puzzling Journey From Tax Rebel to Tax Exempt". New York Times. Retrieved 2007-11-12.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Tank, Ron (1997-01-30). "U.S. report backs Scientologists in dispute with Germany". CNN. Retrieved 2007-11-12.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Schmid, John (1997-01-15). "German Party Replies To Scientology Backers", Herald Tribune

- Masters, Kim (1997-02-10). "Hollywood's Glitterati Circle the Wagons", Time

- Drozdiak, William (1997-01-14). "U.S. Celebrities Defend Scientology in Germany", The Washington Post, p. A11

- ^ Tobin, Thomas C. (2000-07-26). "German visitor takes on Scientology", St. Petersburg Times

External links

- Academic papers

- Schön, Brigitte: "Framing Effects in the Coverage of Scientology versus Germany: Some Thoughts on the Role of Press and Scholars", Marburg Journal of Religion, Volume 6, No. 1 (January 2001)

- Kent, Stephen A.: "The French and German versus American Debate over 'New Religions', Scientology, and Human Rights", Marburg Journal of Religion, Volume 6, No. 1 (January 2001)

- Goodman, Leisa: A Letter from the Church of Scientology, Marburg Journal of Religion, Volume 6, No. 2 (June 2001)

- Zacharias, Diana: "Protective Declarations Against Scientology as Unjustified Detriments to Freedom of Religion: A Comment on the Decision of the German Federal Administrative Court of 15 December 2005", German Law Journal, Volume 7, No. 10 (1 October 2006)

- Kent, Stephen A.: "Hollywood's Celebrity Lobbyists and the Clinton Administration's American Foreign Policy Toward German Scientology", Journal of Religion and Popular Culture, Vol. I, Spring 2002

- Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Geneva

- Implementation of the Declaration on the Elimination of All Forms of Intolerance and of Discrimination Based on Religion or Belief – Report submitted by Mr. Abdelfattah Amor, Special Rapporteur, in accordance with Commission on Human Rights resolution 1994/18 E/CN.4/1995/91, 22 December 1994

- Implementation of the Declaration on the Elimination of All Forms of Intolerance and of Discrimination Based on Religion or Belief – Report submitted by Mr. Abdelfattah Amor, Special Rapporteur, in accordance with Commission on Human Rights resolution 1996/23 – Addendum – Visit to Germany E/CN.4/1998/6/Add.2, 22 December 1997

- Human Rights Committee – Fifty-eighth session – Summary record of the first part (public) of the 1553rd meeting: Germany. 23/01/97. CCPR/C/SR.1553.

- Fifty-fourth session – Item 117 (b) of the provisional agenda – Effective promotion of the Declaration on the Rights of Persons Belonging to National or Ethnic, Religious and Linguistic Minorities – Report of the Secretary-General. A/54/303, 2 September 1999

- Human Rights Committee – Consideration of Reports Submitted by States Parties Under Article 40 of the Covenant – Fifth Periodic Report – Germany, 13 November 2002

- Human Rights Committee – Eightieth session – Decision of the Human Rights Committee under the Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights Communication No. 1138/2002 : Germany. 29/04/2004. CCPR/C/80/D/1138/2002. (Jurisprudence)

- German Embassy, Washington D.C.

- U.S. Department of State

- U.S. Department of State – International Religious Freedom Report 2007: Germany

- U.S. Department of State – International Religious Freedom Report 2008: Germany