| Revision as of 10:35, 22 May 2012 view sourceBaboon43 (talk | contribs)1,650 edits added history← Previous edit | Revision as of 11:08, 22 May 2012 view source Middayexpress (talk | contribs)109,244 edits genealogy of rulers; attrib. Fage claim; Unesco reign name clarification; fmttingNext edit → | ||

| Line 40: | Line 40: | ||

| ==History== | ==History== | ||

| Adal originally had its capital in the port city of ], situated in the eponymous ] region in modern-day northwestern ]. The polity at the time was an ]ate in the larger ] Sultanate ruled by the ].<ref name="Lewispd">{{cite book|last=Lewis|first=I. M.|title=A Pastoral Democracy: A Study of Pastoralism and Politics Among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa|year=1999|publisher=James Currey Publishers|isbn=0852552807|pages=17|url=http://books.google.ca/books?id=eK6SBJIckIsC&pg=PA17#v=onepage&q&f=false}}</ref> | Adal originally had its capital in the port city of ], situated in the eponymous ] region in modern-day northwestern ]. The polity at the time was an ]ate in the larger ] ruled by the ].<ref name="Lewispd">{{cite book|last=Lewis|first=I. M.|title=A Pastoral Democracy: A Study of Pastoralism and Politics Among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa|year=1999|publisher=James Currey Publishers|isbn=0852552807|pages=17|url=http://books.google.ca/books?id=eK6SBJIckIsC&pg=PA17#v=onepage&q&f=false}}</ref> | ||

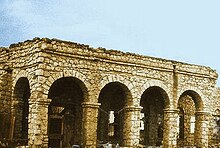

| ], ].]] | ], ].]] | ||

| During its existence, Adal had relations and engaged in trade with other polities in ], the ], ] and ]. Many of the historic cities in the Horn of Africa such as ], ] and ] flourished under its reign with ], ]s, ]s, ]s and ]s. Adal attained its peak in the 14th century, trading in slaves, ivory and other commodities with ] and kingdoms in Arabia through its chief port of Zeila.<ref name="Lewispd"/> | During its existence, Adal had relations and engaged in trade with other polities in ], the ], ] and ]. Many of the historic cities in the Horn of Africa such as ], ] and ] flourished under its reign with ], ]s, ]s, ]s and ]s. Adal attained its peak in the 14th century, trading in slaves, ivory and other commodities with ] and kingdoms in Arabia through its chief port of Zeila.<ref name="Lewispd"/> | ||

| When the last Sultan of Ifat ] was killed by ] at the port city of Zeila in 1410, his children escaped to ], before later returning in 1415.<ref name ="Somaliland">{{cite journal | last =mbali | first =mbali | title =Somaliland | journal =Basic Reference | volume =28 | issue = | pages =217–229 | publisher =mbali | location = London, UK | year =2010 | url =http://www.mbali.info/doc328.htm | doi = 10.1017/S0020743800063145| accessdate =2012-04-27}}</ref> |

When the last Sultan of Ifat ] was killed by ] at the port city of Zeila in 1410, his children escaped to ], before later returning in 1415.<ref name ="Somaliland">{{cite journal | last =mbali | first =mbali | title =Somaliland | journal =Basic Reference | volume =28 | issue = | pages =217–229 | publisher =mbali | location = London, UK | year =2010 | url =http://www.mbali.info/doc328.htm | doi = 10.1017/S0020743800063145| accessdate =2012-04-27}}</ref> In the early 15th century, Adal's capital was moved further inland to the town of ], where ], the eldest son of Sa'ad ad-Din II, established a new sultanate after his return from Yemen.<ref name="Bradt">{{cite book|last=Briggs|first=Philip|title=Bradt Somaliland: With Addis Ababa & Eastern Ethiopia|year=2012|publisher=Bradt Travel Guides|isbn=1841623717|pages=10|url=http://books.google.ca/books?id=M6NI2FejIuwC&pg=PA10#v=onepage&q&f=false}}</ref><ref name="Lewispd"/> The land beyond the ] was left to the Ethiopian ].<ref name ="History of Adal">{{cite journal | last =zum | first =zum | title =History of Adal | journal =Basic Reference | volume =28 | issue = | pages =217–229 | publisher =WHKMLA | location = New York, USA | year =2005 | url =http://www.zum.de/whkmla/region/eastafrica/adal.html | doi = 10.1017/S0020743800063145| accessdate =2012-04-27}}</ref> During this period, Adal emerged as a center of Muslim resistance against the expanding Christian Abyssinian kingdom.<ref name="Lewispd"/> | ||

| The land beyond the ] was left to the Ethiopian ].<ref name ="History of Adal">{{cite journal | last =zum | first =zum | title =History of Adal | journal =Basic Reference | volume =28 | issue = | pages =217–229 | publisher =WHKMLA | location = New York, USA | year =2005 | url =http://www.zum.de/whkmla/region/eastafrica/adal.html | doi = 10.1017/S0020743800063145| accessdate =2012-04-27}}</ref> During this period, Adal emerged as a center of Muslim resistance against the expanding Christian Abyssinian kingdom.<ref name="Lewispd"/> | |||

| ] and his men. From ''Le Livre des Merveilles'', 15th century.]] | ] and his men. From ''Le Livre des Merveilles'', 15th century.]] | ||

| After 1468, a new breed of rulers emerged on the Adal political scene. The dissidents opposed Walashma rule owing to a treaty that Sultan ] had signed with Emperor ], wherein Badlay agreed to submit yearly tribute. Adal's ]s, who administered the provinces, interpreted the agreement as a betrayal of their independence and a retreat from the polity's longstanding policy of resistance to Abyssinian incursions. The main leader of this opposition was the Emir of Zeila, the Sultanate's richest province. As such, he was expected to pay the highest share of the annual tribute to be given to the Abyssinian Emperor.<ref name ="Specific Ethiopia">{{cite journal | last =zum | first =zum | title =Event Doumentation | journal =Basic Reference | volume =28 | issue = | pages =217–229 | publisher =AGCEEP | location = USA | year =2007 | url =http://agceep.net/eventdoc/AGCEEP_Specific_Ethiopia.eue.htm | doi = 10.1017/S0020743800063145| accessdate =2012-04-27}}</ref> Emir Laday Usman subsequently marched to Dakkar and seized power in 1471. However, Usman did not dismiss the Sultan from office, but instead gave made him a ceremonial position while retaining the real power for himself. Adal now came under the leadership of a powerful Emir who governed from a palace of a nominal Sultan.<ref name ="Islam in Ethiopia">{{cite journal | last =Trimingham | first =John | title =Islam in Ethiopia | journal =Basic Reference | volume =28 | issue = | pages =167 | publisher =Oxford University Press | location = UK | year =2007 | url =http://books.google.ca/books?id=B4NHAQAAIAAJ&q=adal+sultanate+dakar+in+1471&dq=adal+sultanate+dakar+in+1471&hl=en&sa=X&ei=rn65T-bpF6TG6AHghbGDCw&ved=0CDMQ6AEwAA| accessdate =2012-04-27}}</ref> | After 1468, a new breed of rulers emerged on the Adal political scene. The dissidents opposed Walashma rule owing to a treaty that Sultan ] had signed with Emperor ], wherein Badlay agreed to submit yearly tribute. Adal's ]s, who administered the provinces, interpreted the agreement as a betrayal of their independence and a retreat from the polity's longstanding policy of resistance to Abyssinian incursions. The main leader of this opposition was the Emir of Zeila, the Sultanate's richest province. As such, he was expected to pay the highest share of the annual tribute to be given to the Abyssinian Emperor.<ref name ="Specific Ethiopia">{{cite journal | last =zum | first =zum | title =Event Doumentation | journal =Basic Reference | volume =28 | issue = | pages =217–229 | publisher =AGCEEP | location = USA | year =2007 | url =http://agceep.net/eventdoc/AGCEEP_Specific_Ethiopia.eue.htm | doi = 10.1017/S0020743800063145| accessdate =2012-04-27}}</ref> Emir Laday Usman subsequently marched to Dakkar and seized power in 1471. However, Usman did not dismiss the Sultan from office, but instead gave made him a ceremonial position while retaining the real power for himself. Adal now came under the leadership of a powerful Emir who governed from a palace of a nominal Sultan.<ref name ="Islam in Ethiopia">{{cite journal | last =Trimingham | first =John | title =Islam in Ethiopia | journal =Basic Reference | volume =28 | issue = | pages =167 | publisher =Oxford University Press | location = UK | year =2007 | url =http://books.google.ca/books?id=B4NHAQAAIAAJ&q=adal+sultanate+dakar+in+1471&dq=adal+sultanate+dakar+in+1471&hl=en&sa=X&ei=rn65T-bpF6TG6AHghbGDCw&ved=0CDMQ6AEwAA| accessdate =2012-04-27}}</ref> | ||

| Line 71: | Line 70: | ||

| The rulers of the earlier Sultanate of Shewa and the Walashma princes of Ifat and Adal all possessed Arab genealogical traditions.<ref name="Elfasi">{{cite book|last=M. Elfasi|first=Ivan Hrbek|title=Africa from the Seventh to the Eleventh Century, General History of Africa, Volume 3|year=1988|publisher=UNESCO|isbn=9231017098|url=http://books.google.ca/books?id=tw0Q0tg0QLoC&pg=PA582#v=onepage&q&f=false|page=580-582}}</ref> | The rulers of the earlier Sultanate of Shewa and the Walashma princes of Ifat and Adal all possessed Arab genealogical traditions.<ref name="Elfasi">{{cite book|last=M. Elfasi|first=Ivan Hrbek|title=Africa from the Seventh to the Eleventh Century, General History of Africa, Volume 3|year=1988|publisher=UNESCO|isbn=9231017098|url=http://books.google.ca/books?id=tw0Q0tg0QLoC&pg=PA582#v=onepage&q&f=false|page=580-582}}</ref> | ||

| Despite this, J.D. Fage proposes that Ethio-Semitic languages may have been the prime mode of communication for the Muslim rulers in the ] region of modern-day Ethiopia. The historian ] describes Ifat's language as "Abyssinian and Arabic". He also lists words, a portion of which are still recognizable, and puts forth the first Arabic language profile of the Ethiopian writing script. According to Fage, Arabic documents published by ] that cite names of the princes in the Sultanate of Shewa and the Walashma dynasty also suggest that Ethio-Semitic may have been spoken by the local Muslims in Shewa.<ref name="The Cambridge History of Africa: From c. 1050 to c. 1600">{{cite journal | last =Fage | first =J.D | coauthors = | title = The Cambridge History of Africa: From c. 1050 to c. 1600 | journal =ISIM Review | volume = | issue =Spring 2005 | page =146-147 | publisher = Cambridge University Press | location =UK | year =2010 | url =http://books.google.ca/books?id=Qwg8GV6aibkC&pg=PA146#v=onepage&q&f=false| doi = | accessdate =2009-04-10 }}</ref> | |||

| However, according to the ''UNESCO General History of Africa'', the repertory in question only keeps a record of the reign names of the rulers. The Sultans themselves, by contrast, could very well have possessed a Muslim personal name in line with their actual genealogical traditions. For example, the Sultan of Genina was known by the ] reign name of ] ("Lord of the dappled seed"), but had a Muslim personal name, Muhammad ibn Da'ud.<ref name="Elfasi"/> | |||

| ==Invasion of Abyssinia== | ==Invasion of Abyssinia== | ||

Revision as of 11:08, 22 May 2012

For other uses, see Adal (disambiguation).| Sultanate of Adal سلطنة عدل | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1415–1577 | |||||||

Flag

Flag | |||||||

Territory of the Sultanate of Adal and its vassal states circa 1500. Territory of the Sultanate of Adal and its vassal states circa 1500. | |||||||

| Capital | Zeila (original capital, as Emirate) Dakkar (new capital, as Sultanate) Harar (final capital) | ||||||

| Common languages | Somali, Oromo, Afar, Arabic, Harar | ||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||

| Sultan, Emir | |||||||

| History | |||||||

| • Established | 1415 | ||||||

| • Disestablished | 1577 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Today part of | |||||||

The Adal Sultanate or the Kingdom of Adal (Template:Lang-so, Template:Lang-gez ʾAdāl, Template:Lang-ar) (c. 1415 - 1577) was a medieval multi-ethnic Muslim state located in the Horn of Africa. At its height, the polity controlled large parts of Somalia, Ethiopia, Djibouti and Eritrea.

History

Adal originally had its capital in the port city of Zeila, situated in the eponymous Awdal region in modern-day northwestern Somalia. The polity at the time was an Emirate in the larger Ifat Sultanate ruled by the Walashma dynasty.

During its existence, Adal had relations and engaged in trade with other polities in Northeast Africa, the Near East, Europe and South Asia. Many of the historic cities in the Horn of Africa such as Maduna, Abasa and Berbera flourished under its reign with courtyard houses, mosques, shrines, walled enclosures and cisterns. Adal attained its peak in the 14th century, trading in slaves, ivory and other commodities with Abyssinia and kingdoms in Arabia through its chief port of Zeila.

When the last Sultan of Ifat Sa'ad ad-Din II was killed by Dawit I of Ethiopia at the port city of Zeila in 1410, his children escaped to Yemen, before later returning in 1415. In the early 15th century, Adal's capital was moved further inland to the town of Dakkar, where Sabr ad-Din II, the eldest son of Sa'ad ad-Din II, established a new sultanate after his return from Yemen. The land beyond the Awash River was left to the Ethiopian Solomonic Emperors. During this period, Adal emerged as a center of Muslim resistance against the expanding Christian Abyssinian kingdom.

After 1468, a new breed of rulers emerged on the Adal political scene. The dissidents opposed Walashma rule owing to a treaty that Sultan Muhammad ibn Badlay had signed with Emperor Baeda Maryam of Ethiopia, wherein Badlay agreed to submit yearly tribute. Adal's Emirs, who administered the provinces, interpreted the agreement as a betrayal of their independence and a retreat from the polity's longstanding policy of resistance to Abyssinian incursions. The main leader of this opposition was the Emir of Zeila, the Sultanate's richest province. As such, he was expected to pay the highest share of the annual tribute to be given to the Abyssinian Emperor. Emir Laday Usman subsequently marched to Dakkar and seized power in 1471. However, Usman did not dismiss the Sultan from office, but instead gave made him a ceremonial position while retaining the real power for himself. Adal now came under the leadership of a powerful Emir who governed from a palace of a nominal Sultan.

Amir Mahfuz who would fight with successive Emperors caused the death of the one oemperor called Na'od in 1508. But he was killed by the forces of Emperor Lebna Dengel in 1517. After Mahfuz, a civil war started for the office of Highest Amir of Adal. Five Amirs came to power in only two years. But at last, a matured and powerful leader called Garad Abuun Addus (Garad Abogn) assumed power. Who was loved by the people of Adal. When Garad Abogne was in power, he was defeated and killed by Abu Bakr ibn Muhammad, In 1554, under the initiative of Sultan Abu Bakr ibn Muhammad, Harar became the capital of Adal. This time, not only the young Amirs revolted but the whole country of Adal raised against the deal of Sultan Abubeker because Garad Abogne was loved by the whole people of the Sultanate. Many people went to join the force of a new young knight called "Ahmad ibn Ibrihim al-Ghazi" who claimed a revenge for the beloved Garad Abogne. And this young man assumed the power of Adal in 1527. But he himself didn't remove the Sultan. He let him in his nominal office. When Abubeker waged war on him, the young Ahmed ibn Ibrahim killed the nominal sultan Abubeker and replaced him by his brother Umar Din.

Adalite armies under the leadership of rulers such as Sabr ad-Din II, Mansur ad-Din, Jamal ad-Din II, Shams ad-Din and general Mahfuz subsequently continued the struggle against Abyssinian expansionism.

In the 16th century, Adal's headquarters were again relocated, this time to Harar. From this new capital, Adal organised an effective army led by Imam Ahmad ibn Ibrihim al-Ghazi that invaded the Abyssinian empire. This campaign is historically known as the Conquest of Abyssinia or Futuh al Habash. During the war, Ahmed pioneered the use of cannons supplied by the Ottoman Empire, which were deployed against Solomonic forces and their Portuguese allies led by Cristóvão da Gama. Some scholars argue that this conflict proved, through their use on both sides, the value of firearms such as the matchlock musket, cannons and the arquebus over traditional weapons.

Ethnicity

During Adal's initial period, when it was centered on the port city of Zeila in present-day northwestern Somalia, the kingdom was primarily composed of Somalis, Afars and Arabs.

There is some debate over the ethnic composition of Adal after its capital moved to modern-day Ethiopia. I.M Lewis states:

Somali forces contributed much to the Imām’s victories. Shihab ad-Din, the Muslim chronicler of the period, writing between 1540 and 1560, mentions them frequently (Futūḥ al-Ḥabasha, ed. And trs. R. Besset Paris, 1897.). The most prominent Somali groups in the campaigns were the Samaroon or Gadabursi (Dir), Geri, Marrehān, and Harti - all Dārod clans. Shihāb d-Dīn is very vague as to their distribution and grazing areas, but describes the Harti as at the time in possession of the ancient eastern port of Mait. Of the Isāq only the Habar Magādle clan seem to have been involved and their distribution is not recorded. Finally several Dir clans also took part.

This finding is supported in the more recent Oxford History of Islam:

The sultanate of Adal, which emerged as the major Muslim principality from 1420 to 1560, seems to have recruited its military force mainly from among the Somalis.

Lewis, on the other hand, notes that the Imam's origins are unknown. Ewald Wagner connects the name ʿAdäl with the Dankali (Afar) tribe Aḏaʿila and the Somali name for the clan Oda ʿAlï, proposing that the kingdom may have largely been composed of Afars. Although Afars constituted a significant part of Adal, Didier Morin notes that "the exact influence of the ʿAfar inside the Kingdom of `Adal is still conjectural due to its multiethnic basis." Nevertheless, Franz-Christoph Muth identifies Ahmad ibn Ibrihim al-Ghazi as Somali.

Language

The rulers of the earlier Sultanate of Shewa and the Walashma princes of Ifat and Adal all possessed Arab genealogical traditions.

Despite this, J.D. Fage proposes that Ethio-Semitic languages may have been the prime mode of communication for the Muslim rulers in the Shewa region of modern-day Ethiopia. The historian Al-Umari describes Ifat's language as "Abyssinian and Arabic". He also lists words, a portion of which are still recognizable, and puts forth the first Arabic language profile of the Ethiopian writing script. According to Fage, Arabic documents published by Enrico Cerulli that cite names of the princes in the Sultanate of Shewa and the Walashma dynasty also suggest that Ethio-Semitic may have been spoken by the local Muslims in Shewa.

However, according to the UNESCO General History of Africa, the repertory in question only keeps a record of the reign names of the rulers. The Sultans themselves, by contrast, could very well have possessed a Muslim personal name in line with their actual genealogical traditions. For example, the Sultan of Genina was known by the Oromo reign name of Abba Djifar ("Lord of the dappled seed"), but had a Muslim personal name, Muhammad ibn Da'ud.

Invasion of Abyssinia

Main article: Ethiopian-Adal War

In the mid-1520s, Imam Ahmad ibn Ibrihim al-Ghazi conquered Adal and launched a holy war against Christian Ethiopia, which was then under the leadership of Lebna Dengel. Supplied by the Ottoman Empire with firearms, Ahmad was able to defeat the Ethiopians at the Battle of Shimbra Kure in 1529 and seize control of the wealthy Ethiopian highlands, though the Ethiopians continued to resist from the highlands. In 1541, the Portuguese, who had vested interests in the Indian Ocean, sent aid to the Ethiopians in the form of 400 musketeers. Adal, in response, received 900 from the Ottomans.

Imam Ahmad was initially successful against the Ethiopians while campaigning in the Autumn of 1542, killing the Portuguese commander Cristóvão da Gama in August that year. However, Portuguese musketry proved decisive in Adal's defeat at the Battle of Wayna Daga, near Lake Tana, in February 1543, where Ahmad was killed in battle. The Ethiopians subsequently retook the Amhara plateau and recouped their losses against Adal. The Ottomans, who had their own troubles to deal with in the Mediterranean, were unable to help Ahmad's successors. When Adal collapsed in 1577, the seat of the Sultanate shifted from Harar to Aussa in the desert region of Afar and a new sultanate began.

The Gadaa expansion

After the conflict between Adal and Ethiopia had subsided, the conquest of the highland regions of Ethiopia and Adal by the Oromo (namely, through military expansion and the installation of the Gadaa socio-political system) ended in the contraction of both regional powers and changed the dynamics of the region for centuries to come. In essence, what had happened is that the populations of the highlands had not ceased to exist as a result of the Gadaa expansion, but were simply incorporated into a different socio-political system.

Legacy

The Adal Sultanate left behind many structures and artefacts from its heyday. Numerous such historical edifices and items are found in the northwestern Awdal province of Somalia, as well as other parts of the Horn region where the polity held sway.

Archaeological excavations in the late 1800s and early 1900s at over fourteen sites in the vicinity of Borama in modern-day northwestern Somalia unearthed, among other artefacts, coins identified as having been derived from Kait Bey, the eighteenth Burji Mamluk Sultan of Egypt. Most of these finds are associated with the medieval Adal Sultanate, and were sent to the British Museum for preservation shortly after their discovery.

Notes

- ^ Lewis, I. M. (1999). A Pastoral Democracy: A Study of Pastoralism and Politics Among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa. James Currey Publishers. p. 17. ISBN 0852552807.

- elrik, Haggai (2007). "The Cambridge History of Africa: From c. 1050 to c. 1600". Basic Reference. 28. USA: Lynne Rienner: 36. doi:10.1017/S0020743800063145. Retrieved 2012-04-27.

- mbali, mbali (2010). "Somaliland". Basic Reference. 28. London, UK: mbali: 217–229. doi:10.1017/S0020743800063145. Retrieved 2012-04-27.

- Briggs, Philip (2012). Bradt Somaliland: With Addis Ababa & Eastern Ethiopia. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 10. ISBN 1841623717.

- zum, zum (2005). "History of Adal". Basic Reference. 28. New York, USA: WHKMLA: 217–229. doi:10.1017/S0020743800063145. Retrieved 2012-04-27.

- zum, zum (2007). "Event Doumentation". Basic Reference. 28. USA: AGCEEP: 217–229. doi:10.1017/S0020743800063145. Retrieved 2012-04-27.

- Trimingham, John (2007). "Islam in Ethiopia". Basic Reference. 28. UK: Oxford University Press: 167. Retrieved 2012-04-27.

- ^ fage, J.D (2007). "The Cambridge History of Africa: From c. 1050 to c. 1600". Basic Reference. 28. USA: Cambridge University Press: 167. doi:10.1017/S0020743800063145. Retrieved 2012-04-27. Cite error: The named reference "The Cambridge History of Africa: From c. 1050 to c. 1600" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- Jeremy Black, Cambridge Illustrated Atlas, Warfare: Renaissance to Revolution, 1492-1792, (Cambridge University Press: 1996), p.9.

- David Hamilton Shinn, Thomas P. Ofcansky (2004). Historical Dictionary of Ethiopia. Scarecrow Press. p. 5. ISBN 0810849100.

- I.M Lewis, "The Somali Conquest of Horn of Africa," The Journal of African History, Vol. 1, No. 2. Cambridge University Press, 1960, p. 223.

- John L. Esposito, editor, The Oxford History of Islam, (Oxford University Press: 2000), p. 501

- Lewis, "The Somali Conquest of the Horn of Africa," p. 223f.

- ^ Herausgegeben von Uhlig, Siegbert, Encyclopaedia Aethiopica. Wiesbaden:Harrassowitz Verlag, 2003, pp.71

- ibid, pp. 155

- ^ M. Elfasi, Ivan Hrbek (1988). Africa from the Seventh to the Eleventh Century, General History of Africa, Volume 3. UNESCO. p. 580-582. ISBN 9231017098.

- Cassanelli, Lee (2007). "The shaping of Somali society: reconstructing the history of a pastoral people". Basic Reference. 28. USA: University of Pennsylvania: 311. doi:10.1017/S0020743800063145. Retrieved 2012-04-27.

- ^ Royal Geographical Society (Great Britain), The Geographical Journal, Volume 87, (Royal Geographical Society: 1936), p.301.

- Bernard Samuel Myers, ed., Encyclopedia of World Art, Volume 13, (McGraw-Hill: 1959), p.xcii.