| Revision as of 01:27, 23 September 2012 editDumbBOT (talk | contribs)Bots293,264 edits removing a protection template from a non-protected page (info)← Previous edit | Revision as of 20:04, 23 September 2012 edit undoPuhach (talk | contribs)20 editsNo edit summaryNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ''']''' is a |

''']''' is a slavic in ]. It is the most common ] in ] and ] regions, the predominant language in large cities in the East and South of the country due to Ukraine's legacy of tsarist and soviet colonialism. The usage and status of the language (currently ] is the only official language of Ukraine<ref>, ]</ref>) is an object of political disputes as a minority of RUssians and russfied non-Russians refuse to use or speak Ukrainian althought they are citizens of the country. Russian language gained the official status of a ] in several southern and eastern oblasts and cities following the passing of a controversial language law in August 2012.<ref>], , 08.08.2012</ref><ref></ref> | ||

| The Russian language is studied as a required course in all secondary schools, including those with Ukrainian as the primary language of instructions.<ref name="ostriv.in.ua"></ref> | The Russian language is studied as a required course in all secondary schools, including those with Ukrainian as the primary language of instructions.<ref name="ostriv.in.ua"></ref> | ||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

| East Slavic languages originate in the language spoken in ]. Significant differences in spoken language in different regions began to be noticed after the division of the Rus lands between Golden Horde and Lithuania. Lithuania, in time united with Poland. Muscovites under the Golden Horde developed the modern Russian language, people in the northern Lithuanian sector developed Belorussian, and in southern Polish sector Ukrainian. | East Slavic languages originate in the language spoken in ]. Significant differences in spoken language in different regions began to be noticed after the division of the Rus lands between Golden Horde and Lithuania. Lithuania, in time united with Poland. Muscovites under the Golden Horde developed the modern Russian language, people in the northern Lithuanian sector developed Belorussian, and in southern Polish sector Ukrainian. | ||

| It is worth noting that the ethnonyms "Ukraine" and "Ukrainian" were not used until the 19th century |

It is worth noting that the ethnonyms "Ukraine" and "Ukrainian" were not used until the 19th century. The Russian imperial centre preferred the names "Little" and "White" Russias, so as to describe the culture and linguistic differences with that of the "Great" Russians. | ||

| There was no geographical border between people speaking Russian and Ukrainian but rather gradual shift in vocabulary and pronunciation along the line between the historical cores of the languages. Since the 20th century, however, people have started to identify themselves with their spoken vernacular and conform to the literary norms set by academics. | There was no geographical border between people speaking Russian and Ukrainian but rather gradual shift in vocabulary and pronunciation along the line between the historical cores of the languages. Since the 20th century, however, people have started to identify themselves with their spoken vernacular and conform to the literary norms set by academics. | ||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

| ===Suppression of the Ukrainian language=== | ===Suppression of the Ukrainian language=== | ||

| The ] promoted the spread of the Russian language among the native Ukrainian population by |

The ] promoted the spread of the Russian language among the native Ukrainian population by refusing to acknowledge the existence of the Ukrainian language and prohibiting its use. At the same time, most Ukrainian literature was printed in Moscow and Saint Petersburg. | ||

| Alarmed by the threat of Ukrainian separatism influenced by recent demands of Polish nationalists, the Russian Minister of Internal Affairs ] in 1863 issued a ] that banned the publication of religious texts and educational texts written in the Ukrainian language<ref name="Miller">{{cite book| author=Miller, Alexei | title=''The Ukrainian Question. The Russian Empire and Nationalism in the Nineteenth Century| location= Budapest-New York | publisher= Central European University Press| year = 203 | ISBN =963-9241-60-1 }}</ref> as non-grammatical, but allowing all other texts, including fiction. This ban was expanded by Tsar Alexander II who issued the ] in 1876 (which lapsed in 1905). All Ukrainian language books and song lyrics were banned, as was the importation of such works. Furthermore, Ukrainian-language public performances, plays, and lectures were forbidden.<ref name=Magosci>{{cite book| author=Magoscy, R. | title=A History of Ukraine| location= Toronto | publisher= University of Toronto Press | year = 1996}}</ref> In 1881, the decree was amended to allow the publishing of lyrics and dictionaries, and the performances of some plays in the Ukrainian language with local officials' approval. Ukrainian-only troupes were, however, forbidden. Approximately 9% of population spoke Russian at the time of the Russian Census of 1897. | Alarmed by the threat of Ukrainian separatism influenced by recent demands of Polish nationalists, the Russian Minister of Internal Affairs ] in 1863 issued a ] that banned the publication of religious texts and educational texts written in the Ukrainian language<ref name="Miller">{{cite book| author=Miller, Alexei | title=''The Ukrainian Question. The Russian Empire and Nationalism in the Nineteenth Century| location= Budapest-New York | publisher= Central European University Press| year = 203 | ISBN =963-9241-60-1 }}</ref> as non-grammatical, but allowing all other texts, including fiction. This ban was expanded by Tsar Alexander II who issued the ] in 1876 (which lapsed in 1905). All Ukrainian language books and song lyrics were banned, as was the importation of such works. Furthermore, Ukrainian-language public performances, plays, and lectures were forbidden.<ref name=Magosci>{{cite book| author=Magoscy, R. | title=A History of Ukraine| location= Toronto | publisher= University of Toronto Press | year = 1996}}</ref> In 1881, the decree was amended to allow the publishing of lyrics and dictionaries, and the performances of some plays in the Ukrainian language with local officials' approval. Ukrainian-only troupes were, however, forbidden. Approximately 9% of population spoke Russian at the time of the Russian Census of 1897. | ||

| The Soviet government adopted a policy of Ukrainization. Ukrainian cultural organizations, such as theatres or Writers' Union, were funded by central administration. While officially there was no state language in the Soviet Union until 1989, Russian was in practice in a privileged position, implicitly because it was |

The Soviet government adopted a policy of Ukrainization between 1923 and 1934. Ukrainian cultural organizations, such as theatres or Writers' Union, were funded by central administration. While officially there was no state language in the Soviet Union until 1989, Russian was in practice in a privileged position, implicitly because without it it was impossible to get a job or be socially mobile. The Ukrainian language, despite official encouragement and government funding of folklore and scholarship, like other regional languages, was often frowned upon or quietly discouraged, which led to a gradual decline in its usage in cities.<ref> by Lenore A. Grenoble</ref> From around 1960s all dissertations were required to be written in Russian only and submitted only in Moscow. That caused most scientific works to be written exclusively in Russian. Studying Russian in all schools was not an option, but the requirement and later in 1980s the teaching of it was ordered to be improved. | ||

| ==Modern usage== | ==Modern usage== | ||

Revision as of 20:04, 23 September 2012

Russian is a slavic in Ukraine. It is the most common first language in Donbass and Crimea regions, the predominant language in large cities in the East and South of the country due to Ukraine's legacy of tsarist and soviet colonialism. The usage and status of the language (currently Ukrainian is the only official language of Ukraine) is an object of political disputes as a minority of RUssians and russfied non-Russians refuse to use or speak Ukrainian althought they are citizens of the country. Russian language gained the official status of a regional language in several southern and eastern oblasts and cities following the passing of a controversial language law in August 2012.

The Russian language is studied as a required course in all secondary schools, including those with Ukrainian as the primary language of instructions.

The number of Russian-teaching schools has been systematically reduced since Ukrainian independence in 1991 and now it is much lower than the proportion of Russophones, but still higher than the proportion of ethnic Russians. Over 75% of media however is in Russian. Ukrainian-language newspapers magazines and DVDs are few and far between in kiosks.

History of Russian language in Ukraine

Main article: History of the Russian language in UkraineEast Slavic languages originate in the language spoken in Rus. Significant differences in spoken language in different regions began to be noticed after the division of the Rus lands between Golden Horde and Lithuania. Lithuania, in time united with Poland. Muscovites under the Golden Horde developed the modern Russian language, people in the northern Lithuanian sector developed Belorussian, and in southern Polish sector Ukrainian.

It is worth noting that the ethnonyms "Ukraine" and "Ukrainian" were not used until the 19th century. The Russian imperial centre preferred the names "Little" and "White" Russias, so as to describe the culture and linguistic differences with that of the "Great" Russians.

There was no geographical border between people speaking Russian and Ukrainian but rather gradual shift in vocabulary and pronunciation along the line between the historical cores of the languages. Since the 20th century, however, people have started to identify themselves with their spoken vernacular and conform to the literary norms set by academics.

Although the ancestors of a small ethnic group of Russians - Goriuns resided in Putyvl region (what is modern northern Ukraine) in the times of Grand Duchy of Lithuania or perhaps even earlier, the Russian language in Ukraine has primarily come to exist in that country through two channels: the migration of ethnic Russians into Ukraine and through the adoption of the Russian language by Ukrainians.

Russian settlers

The first new waves of Russian settlers onto what is now Ukrainian territory came in the late 16th century to the empty lands of Slobozhanschyna that Russia gained from the Tatars, although they were outnumbered by Ukrainian peasants escaping harsh exploitative conditions from the west.

More Russian speakers appeared in northern, central and eastern Ukrainian territories during the late 17th century, following the Cossack Rebellion led by Bohdan Khmelnytsky. The Uprising led to a massive movement of Ukrainian settlers to the Slobozhanschyna region, which converted it from a sparsely inhabited frontier area to one of the major populated regions of the Tsardom of Russia. Following the Pereyaslav Rada the modern northern and eastern parts of Ukraine entered into the Russian Tsardom. This brought the first significant, but still small, wave of Russian settlers into central Ukraine (primarily several thousand soldiers stationed in garrisons, out of a population of approximately 1.2 million non-Russians). Although the number of Russian settlers in Ukraine prior to the 18th century was small, the local upper classes within the part of Ukraine acquired by Russia came to use the Russian language widely.

Beginning in the late 18th century, large numbers of Russians settled in newly acquired lands in southern Ukraine, a region then known as Novorossiya ("New Russia"). These lands had been largely empty prior to the 18th century due to the threat of Crimean Tatar raids, but once the Tatar state was eliminated as a threat, Russian nobles were granted large tracts of fertile land that was worked by newly arrived peasants, most of whom were ethnic Ukrainians but many of whom were Russians.

Dramatic increase of Russian settlers

The 19th century saw a dramatic increase in the urban Russian population in Ukraine, as ethnic Russian settlers moved into and populated the newly industrialized and growing towns. This phenomenon helped turn Ukraine's most important towns into Russophone environments. By the beginning of the 20th century the Russians were the largest ethnic group in almost all large cities within Ukraine's modern borders, including the following: Kiev (54.2%), Kharkiv (63.1%), Odessa (49.09%), Mykolaiv (66.33%), Mariupol (63.22%), Luhansk, (68.16%), Kherson (47.21%), Melitopol (42.8%), Dnipropetrovsk, (41.78%), Kirovohrad (34.64%), Simferopol (45.64%), Yalta (66.17%), Kerch (57.8%), Sevastopol (63.46%). The Ukrainian migrants who settled in these cities entered a Russian-speaking milieu (particularly with Russian-speaking administration) and needed to adopt the Russian language.

Suppression of the Ukrainian language

The Russian government promoted the spread of the Russian language among the native Ukrainian population by refusing to acknowledge the existence of the Ukrainian language and prohibiting its use. At the same time, most Ukrainian literature was printed in Moscow and Saint Petersburg.

Alarmed by the threat of Ukrainian separatism influenced by recent demands of Polish nationalists, the Russian Minister of Internal Affairs Pyotr Valuev in 1863 issued a secret decree that banned the publication of religious texts and educational texts written in the Ukrainian language as non-grammatical, but allowing all other texts, including fiction. This ban was expanded by Tsar Alexander II who issued the Ems Ukaz in 1876 (which lapsed in 1905). All Ukrainian language books and song lyrics were banned, as was the importation of such works. Furthermore, Ukrainian-language public performances, plays, and lectures were forbidden. In 1881, the decree was amended to allow the publishing of lyrics and dictionaries, and the performances of some plays in the Ukrainian language with local officials' approval. Ukrainian-only troupes were, however, forbidden. Approximately 9% of population spoke Russian at the time of the Russian Census of 1897.

The Soviet government adopted a policy of Ukrainization between 1923 and 1934. Ukrainian cultural organizations, such as theatres or Writers' Union, were funded by central administration. While officially there was no state language in the Soviet Union until 1989, Russian was in practice in a privileged position, implicitly because without it it was impossible to get a job or be socially mobile. The Ukrainian language, despite official encouragement and government funding of folklore and scholarship, like other regional languages, was often frowned upon or quietly discouraged, which led to a gradual decline in its usage in cities. From around 1960s all dissertations were required to be written in Russian only and submitted only in Moscow. That caused most scientific works to be written exclusively in Russian. Studying Russian in all schools was not an option, but the requirement and later in 1980s the teaching of it was ordered to be improved.

Modern usage

There is a large difference between the numbers of people whose native language is Russian and people who adopted Russian as their everyday communication language. Another thing to keep in mind is that the percentage of Russian-speaking citizens is significantly higher in cities than in rural areas across the whole country.

2001 Census

According to official data from the 2001 Ukrainian census, the Russian language is native for over 14,273,000 Ukrainian citizens (29.3% of the total population). Ethnic Russians form 56% of the total Russian-speaking population, while the remaining Russophones are people of other ethnic background: 5,545,000 Ukrainians, 172,000 Belarusians, 86,000 Jews, 81,000 Greeks, 62,000 Bulgarians, 46,000 Moldavians, 43,000 Tartars, 43,000 Armenians, 22,000 Poles, 21,000 Germans, 15,000 Crimean Tartars.

Therefore the Russian-speaking population in Ukraine forms the largest linguistic group in modern Europe with its language being non-official in the state. The Russian-speaking population of Ukraine constitutes the largest Russophone community outside the Russian Federation.

Polls

According to July 2012 polling by RATING 55% of the surveyed adult residents over 18 years of age believed that their native language is rather Ukrainian, 40% - rather Russian, 1% - another language. 5% could not decide which language is their native one. Almost 80% of respondents stated they did not have any problems using their native language in 2011. 8% stated they had experienced difficulty in the execution (understanding) of official documents; mostly middle-aged and elderly people in South Ukraine and the Donets Basin.

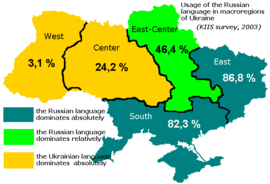

According to a 2004 public opinion poll by the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology, the number of people using Russian language in their homes considerably exceeds the number of those who declared Russian as their native language in the census. According to the survey, Russian is used at home by 43–46% of the population of the country (in other words a similar proportion to Ukrainian) and Russophones make a majority of the population in Eastern and Southern regions of Ukraine:

- Autonomous Republic of Crimea — 97% of the population

- Dnipropetrovsk Oblast — 72%

- Donetsk Oblast — 93%

- Zaporizhia Oblast — 81%

- Luhansk Oblast — 89%

- Mykolaiv Oblast — 66%

- Odessa Oblast — 85%

- Kharkiv Oblast — 74%

Russian language dominates in informal communication in the capital of Ukraine, Kiev. It is also used by a sizeable linguistic minority (4-5% of the total population) in Central and Western Ukraine.

According to data obtained by the "Public opinion" foundation (2002), the population of the oblast centres prefers to use Russian (75%). Continuous Russian linguistic areas occupy certain regions of Crimea, Donbass, Slobozhanschyna, southern parts of Odessa and Zaporizhia oblasts, while Russian linguistic enclaves exist in central Ukraine and Bukovina.

| 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Russian language | 34.7 | 37.8 | 36.1 | 35.1 | 36.5 | 36.1 | 35.1 | 38.1 | 34.5 | 38.1 | 35.7 | 34.1 |

| 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mainly Russian | 32.4 | 32.8 | 33.1 | 34.5 | 33.4 | 33.6 | 36.0 | 36.7 | 33.2 | 36.0 | 34.3 | 36.4 |

| Both Russian and Ukrainian | 29.4 | 34.5 | 29.6 | 26.8 | 28.4 | 29.0 | 24.8 | 25.8 | 28.0 | 25.2 | 26.3 | 21.6 |

Internet

While government organizations are required to have their websites in Ukrainian, the Ukrainian section of the Internet is mostly Russian-speaking. For example, the Russian Misplaced Pages is 5 times more popular in Ukraine than the Ukrainian one. When searching for the keyword "авто" ("cars") in Ukrainian Google, 9 out of 10 most relevant pages are in Russian.

Russian language in Ukrainian politics

The Russian language in Ukraine is not a state language, and is only recognized as language of a national minority. As such, the Russian language is explicitly mentioned in the Constitution of Ukraine adopted by the parliament in 1996. Article 10 of the Constitution reads: "In Ukraine, the free development, use and protection of Russian, and other languages of national minorities of Ukraine, is guaranteed". The Constitution declares Ukrainian language as the state language of the country, while other languages spoken in Ukraine are guaranteed constitutional protection. The Ukrainian language was adopted as the state language by the Law on Languages adopted in Ukrainian SSR in 1989; Russian was specified as the language of communication with the other republics of Soviet Union.

Ukraine signed the European Charter on Regional or Minority Languages in 1996, but ratified it only in 2002 when the Parliament adopted the law that partly implemented the charter.

Regional language 2012

Effective in August 2012, a new law on regional languages entitles any local language spoken by at least a 10% minority be declared official within that area. This has effectively improved the position of Russian, which was within weeks declared as a regional language in several southern and eastern oblasts and cities.

Second official language?

| 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 52.0 | 50.9 | 43.9 | 47.6 | 46.7 | 44.0 | 47.4 | 48.6 | 47.3 | 47.5 | 48.6 |

| Hard to say | 15.3 | 16.1 | 20.6 | 15.3 | 18.1 | 19.3 | 16.2 | 20.0 | 20.4 | 20.0 | 16.8 |

| No | 32.6 | 32.9 | 35.5 | 37.0 | 35.1 | 36.2 | 36.0 | 31.1 | 31.9 | 32.2 | 34.4 |

| No answer | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.1 |

The issue of Russian receiving status of second official language has been the subject of extended controversial discussion ever since Ukraine became independent in 1991. In every Ukrainian election, many politicians, such as former president Leonid Kuchma, used their promise of making Russian a second state language to win support. The current President of Ukraine, Viktor Yanukovych continued this practice when he was opposition leader. But in an interview with Kommersant during the 2010 Ukrainian presidential election-campaign he stated that the statued of Russian in Ukraine "is too politicized" and said that if elected President in 2010 he would "have a real opportunity to adopt a law on languages, which implements the requirements of the European Charter of regional languages". He implied these law would need 226 votes in the Ukrainian parliament (50% of the votes instead of the 75% of the votes needed to change the constitution of Ukraine). After his early 2010 election as President Yanukovych stated (on March 9, 2010) "Ukraine will continue to promote the Ukrainian language as its only state language". At the same time he stressed that it also necessary to develop other regional languages.

Former president Viktor Yushchenko, during his 2004 Presidential campaign, also claimed a willingness to introduce more equality for Russian speakers. His clipping service spread an announcement of his promise to make Russian language proficiency obligatory for officials who interact with Russian-speaking citizens. In 2005 Yushchenko stated that he had never signed this decree project. The controversy was seen by some as a deliberate policy of Ukrainization.

In 2006 the Kharkiv City Rada was the first to declare Russian to be a regional language. Following that, almost all southern and eastern oblasts (Luhansk, Donetsk, Mykolaiv, Kharkiv, Zaporizhia, and Kherson oblasts), and major cities (Sevastopol, Dnipropetrovsk, Donetsk, Yalta, Luhansk, Zaporizhia, Kryvyi Rih, Odessa) followed suit. By ruling of several courts, decision to change the status of the Russian language in the cities of Kryvyi Rih, Kherson, Dnipropetrovsk, Zaporizhia and Mykolaiv have been overturned while in Donetsk, Mykolaiv and Kharkiv oblasts it was retained. According to survey by "Research and Branding group" (June 2006) the majority of the interviewed supported the decisions of local authorities: 52% largely supported (including 69% of population of eastern oblasts and 56% of southern regions), 34% largely did not support the decisions, 9% - answered "partially support and partially not", 5% had no opinion.

According to an all-Ukrainian poll carried out in February 2008 by "Ukrainian Democratic Circle" 15% of those polled said that the language issue should be immediately solved, in November 2009 this was 14.7%; in the November 2009 poll 35.8% wanted both the Russian and Ukrainian language to be state languages.

According to polling by RATING the level of support for granting Russian the status of the state language has decreased (from 54% to 46%) and the number of opponents has increased (from 40% to 45%) since 2009 (till May 2012); in July 2012 41% of respondents supported granting Russian the status of the state language and 51% opposed it. (In July 2012) among the biggest supporters of bilingualism where residents of the Donets Basin (85%), South Ukraine (72%) and East Ukraine (50%).

Polls

Although officially Russian speakers comprise about 30% (2001 census), 39% of Ukrainians interviewed in a 2006 survey believe that the rights of Russophones are violated because the Russian language is not official in the country, whereas 38% had the opposite position.

On a cross-national survey 0.5% of respondents felt they were discriminated against because of their language.

According to a poll carried out by the Social Research Center at the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy in late 2009 ideological issues were ranked third (15%) as reasons to organized mass protest actions (in particular, the issues of joining NATO, the status of the Russian language, the activities of left- and right-wing political groups, etc.); behind economic issues (25%) and problems of ownership (17%).

According to March 2010 survey, forced Ukrainization and Russian language suppression are of concern to 4.8% of the population.

Education in Russian

The Law on Education grants Ukrainian families (parents and their children) a right to choose their native language for schools and studies.

The amount of Russian-teaching schools has been systematically reduced since 1991 and now it is much lower than the proportion of Russophones.

The Russian language is still studied as a required course in all secondary schools, including those with Ukrainian as the primary language of instructions. The Ukrainian language is studied as a required course in all Russian language schools.

Russian in courts

Since January 1, 2010 it is allowed to hold court proceedings in Russian on mutual consent of parties. Citizens, who are unable to speak Ukrainian or Russian are allowed to use their native language or the services of an interpreter.

See also

- Russians in Ukraine

- Human Rights Public Movement "Russian-speaking Ukraine", a non-governmental organisation based in Ukraine.

Bibliography

- Русские говоры Сумской области. Сумы, 1998. — 160 с ISBN 966-7413-01-2

- Русские говоры на Украине. Киев: Наукова думка, 1982. — 231 с.

- Степанов, Є. М.: Російське мовлення Одеси: Монографія. За редакцією д-ра філол. наук, проф. Ю. О. Карпенка, Одеський національний університет ім. І. І. Мечнікова. Одеса: Астропринт, 2004. — 494 с.

- Фомин А. И. Языковой вопрос в Украине: идеология, право, политика. Монография. Второе издание, дополненное. — Киев: Журнал «Радуга». — 264 с ISBN 966-8325-65-6

- Rebounding Identities: The Politics of Identity in Russia and Ukraine. Edited by Dominique Arel and Blair A. Ruble Copub. The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006. 384 pages. ISBN 0-8018-8562-0 and ISBN 978-0-8018-8562-4

- Bilaniuk, Laada. Contested Tongues: Language Politics And Cultural Correction in Ukraine. Cornell University Press, 2005. 256 pages. ISBN 978-0-8014-4349-7

- Laitin, David Dennis. Identity in Formation: The Russian-Speaking Populations in the Near Abroad. Cornell University Press, 1998. 417 pages. ISBN 0-8014-8495-2

References

- Ukrainian Language, Ukrainian Ministry of Foreign Affairs

- France 24, elevates status of Russian language, 08.08.2012

- Russian spreads like wildfires in dry Ukrainian forest

- ^ Press-release of the Ukrainian Ministry for Education and Science

- ^ Vasyl Ivanyshyn, Yaroslav Radevych-Vynnyts'kyi, Mova i Natsiya, Drohobych, Vidrodzhennya, 1994, ISBN 5-7707-5898-8

- ^ "the number of Ukrainian secondary schools has increased to 15,900, or 75% of their total number. In all, about 4.5 million students (67.4% of the total) are taught in Ukrainian, in Russian – 2.1 million (31.7%)..."

"Annual Report of the Ukrainian Parliament Commissioner for Human Rights “On the situation with observance and protection of human rights and freedoms in Ukraine” for the period from April 14, 1998 till December 31, 1999" - ^ Volodymyr Malynkovych, Ukrainian perspective, Politicheskiy Klass, January 2006

- F.D. Klimchuk, About ethnoliguistic history of Left Bank of Dnieper (in connection to the ethnogenesis of Goriuns). Published in "Goriuns: history, language, culture" Proceedings of International Scientific Conference, (Institute of Linguistics, Russian Academy of Sciences, February 13, 2004)

- ^ Russians in Ukraine

- ^ Display Page

- Дністрянський М.С. Етнополітична географія України. Лівів Літопис, видавництво ЛНУ імені Івана Франка, 2006, page 342 isbn = 966-7007-60-4 |

- Miller, Alexei (203). The Ukrainian Question. The Russian Empire and Nationalism in the Nineteenth Century. Budapest-New York: Central European University Press. ISBN 963-9241-60-1.

- Magoscy, R. (1996). A History of Ukraine. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Language policy in the Soviet Union by Lenore A. Grenoble

- "Results / General results of the census / Linguistic composition of the population". 2001 Ukrainian Census. Retrieved August 28, 2006.

- ^ The language question, the results of recent research in 2012, RATING (25 May 2012)

- "Portrait of Yushchenko and Yanukovych electorates". Analitik (in Russian). Retrieved March 7, 2007.

- Лариса Масенко

- "Byurkhovetskiy: Klichko - ne sornyak i ne buryan, i emu nuzhno vyrasti". Korrespondent (in Russian). Retrieved March 7, 2007.

- "In Ukraine there are more Russian language speakers than Ukrainian ones". Evraziyskaya panorama (in Russian). Retrieved March 7, 2007.

- Евразийская панорама

- ^ "Ukrainian society 1994-2005: sociological monitoring". http://dif.org.ua/ (in Ukrainian). Retrieved April 10, 2007.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - Wikimedia Traffic Analysis Report

- Article 10 of the Constitution says: "The state language of Ukraine is the Ukrainian language. The State ensures the comprehensive development and functioning of the Ukrainian language in all spheres of social life throughout the entire territory of Ukraine. In Ukraine, the free development, use and protection of Russian, and other languages of national minorities of Ukraine, is guaranteed."

- On Languages in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. Law. 1989 (in English)

- В.Колесниченко. «Европейская хартия региональных языков или языков меньшинств. Отчет о ее выполнении в Украине, а также о ситуации с правами языковых меньшинств и проявлениями расизма и нетерпимости»

- Yanukovych signs language bill into law. Retrieved 2012-09-07.

- Russian spreads like wildfires in dry Ukrainian forest. Retrieved 2012-09-07.

- In regions, according to 2005 survey by the National Institute of Strategic Research

- Template:Ru icon "Доверия к Тимошенко у меня нет и быть не может", Kommersant (December 9, 2009)

- Yanukovych: Ukraine will not have second state language, Kyiv Post (March 9, 2010)

- Янукович: Русский язык не будет вторым государственным , Подробности (March 9, 2010 13:10)

- Clipping service of Viktor Yuschenko (18 October 2004). "Yuschenko guarantee equal rights for Russian and other minority languages - Decree project". Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved April 10, 2007.

- Lenta.ru (18 July 2005). "Yuschenko appealed to Foreign Office to forget Russian language". Retrieved April 10, 2007.

- An interview with Prof. Lara Sinelnikova, Русский язык на Украине – проблема государственной безопасности, Novyi Region, 19.09.06

- Tatyana Krynitsyna, Два языка - один народ, Kharkiv Branch of the Party of Regions, 09.12.2005

- http://pravopys.vlada.kiev.ua/index.php?id=487

- "Russian language in Odessa is acknowledged as the second official government language ..." Newsru.com (in Russian). Retrieved March 7, 2007.

- УРА-Информ :: Версия для печати

- 80% of Ukrainians do not consider language issue a top-priority, UNIAN (23 February 2009)

- Poll: more than half of Ukrainians do not consider language issue pressing, Kyiv Post (November 25, 2009)

- According to parliamentary deputy Vadym Kolesnichenko, the official policies of the Ukrainian state are discriminatory towards the Russian-speaking population. The Russian speaking population received 12 times less state funding than the tiny Romanian-speaking population in 2005-2006. Education in Russian is nearly nonexistent in all central and western oblasts and Kiev. The Russian language is no longer in higher education in all Ukraine, including areas with a Russian-speaking majority. The broadcasting in Russian averaged 11.6% (TV) and 3.5% (radio) in 2005. Kolesnichenko is a member of Party of Regions with majority of electorate in eastern and south Russian-speaking regions.

- Большинство украинцев говорят на русском языке // Podrobnosti.Ua

- Украинцы лучше владеют русским языком, чем украинским: соцопрос - Новости России - ИА REGNUM

- Evhen Golovakha, Andriy Gorbachyk, Natalia Panina, "Ukraine and Europe: Outcomes of International Comparative Sociological Survey", Kiev, Institute of Sociology of NAS of Ukraine, 2007, ISBN 978-966-02-4352-1, pp. 133-135 in Section: "9. Social discrimination and migration" (pdf)

- Poll: economic issues and problems of ownership main reasons for public protests, Kyiv Post (December 4, 2009)

- http://life.pravda.com.ua/problem/4bc31444820e5/

- Ukraine/ Compendium of Cultural Policies and Trends in Europe, 10th edition, Council of Europe (2009)

- Ukraine Seeks Nationwide Linguistic Revival, Voice of America (November 13, 2008)

- Constitutional Court rules Russian, other languages can be used in Ukrainian courts, Kyiv Post (15 December 2011)

Template:Uk icon З подачі "Регіонів" Рада дозволила російську у судах, Ukrayinska Pravda (23 June 2009)

Template:Uk icon ЗМІ: Російська мова стала офіційною в українських судах, Novynar (29 July 2010)

Template:Uk icon Російська мова стала офіційною в українських судах, forUm (29 July 2010)

External links

- Template:Ru icon "Доклад "Русский язык в мире"" (in Russian). Moscow: Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Russia). 2002. Archived from the original on 22 September 2011. Retrieved 22 September 2011.