| Revision as of 23:53, 2 January 2013 editAnomieBOT (talk | contribs)Bots6,572,413 edits Rescuing orphaned refs ("MyThyroid" from rev 530998945)← Previous edit | Revision as of 00:11, 3 January 2013 edit undoDoc James (talk | contribs)Administrators312,280 edits reverted back to before copyright issuesNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Infobox_Disease | |||

| {{Infobox disease | |||

| | Name = Graves' disease | | Name = Graves' disease | ||

| | Image = |

| Image = | ||

| | Caption = | |||

| | Caption = Photo showing the classic finding of ] and lid retraction in Graves' disease. | |||

| | DiseasesDB = | | DiseasesDB = | ||

| | ICD10 = {{ICD10|E|05|0|e|00}} | | ICD10 = {{ICD10|E|05|0|e|00}} | ||

| | ICD9 = {{ICD9|242.0}} | | ICD9 = {{ICD9|242.0}} | ||

| | ICDO = | | ICDO = | ||

| | OMIM = 275000 | | OMIM = 275000 | ||

| | MedlinePlus = 000358 | | MedlinePlus = 000358 | ||

| | eMedicineSubj = med | | eMedicineSubj = med | ||

| | eMedicineTopic = 929 | | eMedicineTopic = 929 | ||

| | eMedicine_mult = {{eMedicine2|ped|899}} | | eMedicine_mult = {{eMedicine2|ped|899}} | ||

| | MeshID = D006111 | | MeshID = D006111 | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''Graves' disease''' is an ] disease where the ] is overactive, producing an excessive amount of thyroid hormones (a serious metabolic imbalance known as ] and ]). This is caused by ] that activate the ]-receptor, thereby stimulating thyroid hormone synthesis and secretion, and thyroid growth (causing a diffusely enlarged ]). The resulting state of hyperthyroidism can cause a dramatic constellation of ] and physical signs and symptoms.<ref name="isbn1-878398-20-2">{{Cite book|author=Patterson, Nancy Ruth; Jake George |title=Graves' Disease In Our Own Words |publisher=Blue Note Pubns |location= |year=2002 |pages= |isbn=1-878398-20-2 |oclc= |doi= |accessdate=}}</ref> | |||

| '''Graves' disease''' is an ] disease. It most commonly affects the ], frequently causing it to enlarge to twice its size or more (]), become overactive, with related ] such as increased heartbeat, muscle weakness, disturbed sleep, and irritability. It can also ], causing bulging eyes (]). It affects other systems of the body, including the skin, heart, circulation and nervous system. | |||

| Graves' disease is the most common cause of hyperthyroidism (60-90% of all cases), and usually presents itself during midlife, but also appears in children, adolescents, and the elderly.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.gdatf.org/about/about-graves-disease |title=About Graves’ Disease |author=Graves’ Disease & Thyroid Foundation |accessdate=June 20, 2012}}</ref> It has a powerful ] component, affects up to 2% of the female population, and is between five and ten times as common in females as in males.<ref name="ThyroidManager-Ch10-Groot">Graves' Disease and the Manifestations of ] - Leslie l. De Groot, Thyroid Disease Manager, Chapter 10 (http://www.thyroidmanager.org/Chapter10/10-frame.htm)</ref> Graves’ disease is also the most common cause of severe hyperthyroidism, which is accompanied by more clinical signs and symptoms and laboratory abnormalities as compared with milder forms of hyperthyroidism.<ref name="pmid19681915">{{Cite journal|author=Iglesias P, Dévora O, García J, Tajada P, García-Arévalo C, Díez JJ |title=Severe hyperthyroidism: aetiology, clinical features and treatment outcome |journal=Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf) |volume= 72|issue= 4|pages= 551–7|year=2009 |month=August |pmid=19681915 |doi=10.1111/j.1365-2265.2009.03682.x |url=}}</ref> About 30-50% of people with Graves' disease will also suffer from ] (a protrusion of one or both eyes), caused by inflammation of the eye muscles by attacking autoantibodies.<ref>http://supplements.amjmed.com/2010/hyperthyroid/</ref> | |||

| It affects up to 2% of the female population, sometimes appears after childbirth, and has a female:male incidence of 5:1 to 10:1. It has a strong ] component; when one identical twin has Graves' disease, the other twin will have it 25% of the time. Smoking and exposure to second-hand smoke is associated with the eye manifestations but not the thyroid manifestations. | |||

| Diagnosis is usually made on the basis of symptoms, although thyroid hormone tests may be useful.<ref name="pmid18550875">{{Cite journal|author=Brent GA |title=Clinical practice. Graves' disease |journal=N. Engl. J. Med. |volume=358 |issue=24 |pages=2594–605 |year=2008 |month=June |pmid=18550875 |doi=10.1056/NEJMcp0801880 |url=}}</ref> Graves’ thyrotoxicosis frequently builds over an extended period, sometimes years, before being diagnosed.<ref name="pmid15538931">{{Cite journal|author=Elberling TV, Rasmussen AK, Feldt-Rasmussen U, Hørding M, Perrild H, Waldemar G |title=Impaired health-related quality of life in Graves' disease. A prospective study |journal=Eur. J. Endocrinol. |volume=151 |issue=5 |pages=549–55 |year=2004 |month=November |pmid=15538931 |doi= 10.1530/eje.0.1510549|url=http://eje-online.org/cgi/reprint/151/5/549.pdf |format=PDF}}</ref> This is partially because symptoms can develop so insidiously, they go unnoticed; when they do get reported, they are often confused with other health problems. Thus, diagnosing thyroid disease clinically can be challenging.<ref name="pmid10695693">{{Cite journal|author=Canaris GJ, Manowitz NR, Mayor G, Ridgway EC |title=The Colorado thyroid disease prevalence study |journal=Arch. Intern. Med. |volume=160 |issue=4 |pages=526–34 |year=2000 |month=February |pmid=10695693 |doi= 10.1001/archinte.160.4.526|url=http://archinte.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/160/4/526}}</ref> Nevertheless, patients can experience a wide range of symptoms and suffer major impairment in most areas of health-related quality of life.<ref name="pmid16556711">{{Cite journal|author=Watt T, Groenvold M, Rasmussen AK, ''et al.'' |title=Quality of life in patients with benign thyroid disorders. A review |journal=Eur. J. Endocrinol. |volume=154 |issue=4 |pages=501–10 |year=2006 |month=April |pmid=16556711 |doi=10.1530/eje.1.02124 |url=http://eje-online.org/cgi/content/full/154/4/501}}</ref> | |||

| Diagnosis is usually made on the basis of symptoms, although thyroid hormone tests may be useful, particularly to monitor treatment.<ref></ref> | |||

| Graves’ disease has no cure, but treatments for its consequences (hyperthyroidism, ophthalmopathy, and mental symptoms) are available.<ref name="pmid17044727">{{Cite journal|author=Bunevicius R, Prange AJ |title=Psychiatric manifestations of Graves' hyperthyroidism: pathophysiology and treatment options |journal=CNS Drugs |volume=20 |issue=11 |pages=897–909 |year=2006 |pmid=17044727 |doi= |url=}}</ref> The Graves’ disease itself - as defined, for example, by high serum thyroid autoantibodies (TSHR-Ab) concentrations or ophthalmopathy - often persists after its hyperthyroidism has been successfully treated.<ref name="pmid17044727"/> | |||

| ==History== | |||

| ==Symptoms and signs== | |||

| Graves' disease owes its name to the Irish doctor ],<ref>{{WhoNamedIt|doctor|695|Mathew Graves}}</ref> who described a case of goitre with exophthalmos in 1835.<ref>Graves, RJ. ''New observed affection of the thyroid gland in females''. (Clinical lectures.) London Medical and Surgical Journal (Renshaw), 1835; 7: 516-517. Reprinted in Medical Classics, 1940;5:33-36.</ref> However, the German ] independently reported the same constellation of symptoms in 1840.<ref>Von Basedow, KA. ''Exophthalmus durch Hypertrophie des Zellgewebes in der Augenhöhle.'' Wochenschrift für die gesammte Heilkunde, Berlin, 1840, 6: 197-204; 220-228. Partial English translation in: Ralph Hermon Major (1884-1970): Classic Descriptions of Disease. Springfield, C. C. Thomas, 1932. 2nd edition, 1939; 3rd edition, 1945.</ref><ref>Von Basedow, KA. ''Die Glotzaugen.'' Wochenschrift für die gesammte Heilkunde, Berlin, 1848: 769-777.</ref> As a result, on the European Continent, the terms '''Basedow's syndrome'''<ref name=WNI/>, or '''Basedow's disease'''<ref name=TMHP>{{cite-TMHP|Exophthalmic goiter, Basedow's disease, Grave's disesase}}, pages 82, 294, and 295.</ref> are more common than Graves' disease.<ref name=WNI>{{WhoNamedIt|synd|1517|Basedow's syndrome or disease}} - the history and naming of the disease</ref><ref>{{eMedicine|med|917|Goiter, Diffuse Toxic}}</ref> | |||

| {{Main|Symptoms and signs of Graves' disease}} | |||

| The symptoms and signs of Graves' disease virtually all result from the direct and indirect effects of ], with main exceptions being ], ], and ] (which are caused by the autoimmune processes of the disease). Symptoms of the resultant hyperthyroidism are mainly ], hand ], ], hair loss, excessive ], heat intolerance, ] despite ], ], frequent ], ]s, ], and skin warmth and moistness.<ref name=agabegi2nd157>page 157 in:{{cite book |author=Elizabeth D Agabegi; Agabegi, Steven S. |title=Step-Up to Medicine (Step-Up Series) |publisher=Lippincott Williams & Wilkins |location=Hagerstwon, MD |year=2008 |pages= |isbn=0-7817-7153-6 |oclc= |doi= |accessdate=}}</ref> Further signs that may be seen on ] are most commonly a diffusely enlarged (usually symmetric), nontender thyroid, ], excessive ] due to Graves' ophthalmopathy, ]s of the heart, such as ], ] and ]s, and ].<ref name=agabegi2nd157/> Thyrotoxic patients may experience behavioral and personality changes, such as ], ], and ]. In milder hyperthyroidism, patients will rather experience less overt manifestations, such as ], restlessness, ], and ].<ref>A survey study of neuropsychiatric complaints in patients with Graves' disease. Stern RA, Robinson B, Thorner AR, Arruda JE, Prohaska ML, Prange AJ Jr - J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1996;8(2):181.</ref> | |||

| '''Graves' disease'''<ref name=WNI/><ref name=TMHP/> has also been called '''exophthalmic goitre'''.<ref name=TMHP/> | |||

| ==Cause== | |||

| The trigger for ] production is unknown. | |||

| Less commonly, it has been known as '''Parry's disease''',<ref name=WNI/><ref name=TMHP/> '''Begbie's disease''', '''Flajani's disease''', '''Flajani-Basedow syndrome''', and '''Marsh's disease'''.<ref name=WNI/> The names Graves' disease and Parry's disease were based also on other pioneer investigators of the disorder, namely: ] and ], respectively. The rest of the other names for the disease were derived from ], ], and ].<ref name=WNI/> The other names are from several earlier reports that exist but were not widely circulated. For example, cases of goitre with exophthalmos were published by the Italians Giuseppe Flajina<ref>Flajani, G. ''Sopra un tumor freddo nell'anterior parte del collo broncocele. (Osservazione LXVII).'' In Collezione d'osservazioni e reflessioni di chirurgia. Rome, Michele A Ripa Presso Lino Contedini, 1802;3:270-273.</ref> and Antonio Giuseppe Testa,<ref>Testa, AG. ''Delle malattie del cuore, loro cagioni, specie, segni e cura.'' Bologna, 1810. 2nd edition in 3 volumes, Florence, 1823; Milano 1831; German translation, Halle, 1813.</ref> in 1802 and 1810, respectively.<ref>{{WhoNamedIt|doctor|1471|Giuseppe Flajani}}</ref> Prior to these, Caleb Hillier Parry,<ref>Parry, CH. ''Enlargement of the thyroid gland in connection with enlargement or palpitations of the heart.'' Posthumous, in: Collections from the unpublished medical writings of C. H. Parry. London, 1825, pp. 111-129. According to Garrison, Parry first noted the condition in 1786. He briefly reported it in his Elements of Pathology and Therapeutics, 1815. Reprinted in Medical Classics, 1940, 5: 8-30.</ref> a notable provincial physician in England of the late 18th century (and a friend of ]),<ref>{{cite journal |author=Hull G |title=Caleb Hillier Parry 1755-1822: a notable provincial physician |journal=Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine |volume=91 |issue=6 |pages=335–8 |year=1998 |pmid=9771526 |pmc=1296785 |doi= |url=}}</ref> described a case | |||

| ===Neuropsychological manifestations=== | |||

| in 1786. This case was not published until 1825, but still 10 years ahead of Graves.<ref>{{WhoNamedIt|doctor|397|Caleb Hillier Parry}}</ref> | |||

| Hyperthyroidism plays a major role in psychiatric ] in Graves' disease, and is associated with long-term mood disturbances.<ref name="pmid15763125"/><ref name="pmid15817908">{{Cite journal|author=Thomsen AF, Kvist TK, Andersen PK, Kessing LV |title=Increased risk of affective disorder following hospitalisation with hyperthyroidism - a register-based study |journal=Eur. J. Endocrinol. |volume=152 |issue=4 |pages=535–43 |year=2005 |month=April |pmid=15817908 |doi=10.1530/eje.1.01894 |url=http://eje-online.org/cgi/content/full/152/4/535}}</ref> Although hyperthyroidism has been considered to induce psychiatric symptoms by enhancement of the sensitivity and turnover in catecholaminergic ], the precise mechanism of cognitive and behavioral dysfunction in hyperthyroidism is not known.<ref name="pmid11925523">{{Cite journal|author=Nibuya M, Sugiyama H, Shioda K, Nakamura K, Nishijima K |title=ECT for the treatment of psychiatric symptoms in Basedow's disease |journal=J ECT |volume=18 |issue=1 |pages=54–7 |year=2002|month=March |pmid=11925523 |doi= 10.1097/00124509-200203000-00014|url=}}</ref> According to Gonen, the direct influence of ] on brain functions stems from the wide distribution of T3 receptors throughout the brain.<ref>{{Cite journal| doi = 10.1507/endocrj.51.311 | author = Gonen | title = Assessment of anxiety in subclinical thyroid disorders | journal = Endocrine journal | year = 2004 | volume = 51 | issue = 3 | pages = 311–315 | pmid = 15256776 | last2 = Kisakol | first2 = G | last3 = Savas Cilli | first3 = A | last4 = Dikbas | first4 = O | last5 = Gungor | first5 = K | last6 = Inal | first6 = A | last7 = Kaya | first7 = A}}</ref> Improvement of some clinical features (attention and concentration) with ] suggests a role for a hyperthyroid-induced hyperactivity of the adrenergic nervous system, possibly disrupting the adrenergic pathways between the ] and ] that subserve attention and vigilance, and thereby accounting for many physical and mental symptoms.<ref>{{Cite journal| title = Psychiatric Manifestations of Graves' Hyperthyroidism Pathophysiology and Treatment Options | author = Robertas Bunevicius and Arthur J. Prange Jr | journal = CNS Drugs | year = 2006 | volume = 20 | issue = 11 | pages = 897–909 | pmid = 17044727}}</ref> | |||

| Another possibility is hyperthyroidism may cause ], resulting in neuronal injury and hastening the presentation of degenerative or ].<ref>Low thyroid-stimulating hormone as an independent risk factor for Alzheimer disease. van Osch LA, Hogervorst E, Combrinck M, Smith AD - Neurology. 2004;62(11):1967.</ref> A 2002 study suggests another possible mechanism, involving activational and ] of functional proteins in the brain.<ref name="pmid11925523"/> | |||

| However, fair credit for the first description of Graves' disease goes to the 12th century ] ],<ref>Sayyid Ismail Al-Jurjani. ''Thesaurus of the Shah of Khwarazm.''</ref> who noted the association of goitre and exophthalmos in his "Thesaurus of the Shah of Khwarazm", the major medical dictionary of its time.<ref name=WNI/><ref>{{cite journal |author=Ljunggren JG |title= |journal=Lakartidningen |volume=80 |issue=32-33 |page=2902 |year=1983 |month=August |pmid=6355710 |doi= |url=}}</ref><ref>{{citation|journal=International Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism|year=2003|volume=1|pages=43–45 |title=Clinical Endocrinology in the Islamic Civilization in Iran|last=Nabipour|first=I.}}</ref> | |||

| Whatever the precise mechanisms, thyroid hormones clearly influence adult brain functioning, and may interact with mood regulation via targets in specific brain circuits.<ref name="pmid15817908"/> Singh ''et al.'' formulate, "differential thyroidal status is known to cause decrease in cell number and induces irreversible ] changes in adult brain resulting in different neuronal abnormalities".<ref name="ReferenceC">Hyperthyroidism Induces Apoptosis in the Adult Cerebral Cortex: Direct Action of T3 on Mitochondria R. Singh, G. Upadhyay, A. Kapoor, S. Kumar, A. Kumar, M. Tiwari, M.M. Godbole</ref> This is underscored by recent studies, which document a thyroid hormone effect on the neurotransmitters ] and ], with changes in neurotransmitter synthesis and receptor sensitivity being noted.<ref name="Thomapson2007">{{Cite journal| title = Is There A Thyroid-Cortisol-Depression Axis? | author = Frank King Thompson | journal = Thyroid Science | volume = 2 | issue = 10 | page = 1 | year = 2007}}</ref> De Groot points out, in spite of the fact that ] levels and catecholamine excretion are actually not elevated, ] (it is presumed, acting by inhibition of alpha-adrenergic sympathetic activity) reduces anxiety and ] in a very useful manner, indicating some of the central nervous system irritability is a manifestation of elevated sensitivity to circulating epinephrine.<ref name="ThyroidManager-Ch10-Groot"/> Thompson mentioned ] can increase the activity of serotonin in the brain, while serotonin has been shown to inhibit thyroid function. Thus, although a complex system of interaction between thyroid hormone and neurotransmitters has been recognized and examined, no clear-cut explanation for the effect of thyroid hormone on depression has emerged.<ref name="Thomapson2007"/> | |||

| ==Diagnosis== | |||

| Graves' ophthalmopathy may also contribute to psychiatric morbidity, presumably through the psychosocial consequences of a changed appearance.<ref name="pmid17044727"/> However, the observation that a substantial proportion of patients have altered mental states even after successful treatment of hyperthyroidism, has led some researchers to suggest the autoimmune process itself may play a role in the presentation of mental symptoms and psychiatric disorders in Graves’ disease, whether or not ophthalmopathy is present.<ref name="pmid17044727"/> Persistent stimulation of thyroid-stimulating hormone receptors (TSH-Rs) may be involved. In Graves’ disease, the TSH-R gives rise to antibodies, and in some patients, these antibodies persist after restoration of euthyroidism. The ] and ] are rich in TSH-Rs. Antibody stimulation of these brain receptors may result in increased local production of T3.<ref name="pmid17044727"/> | |||

| ]]] | |||

| Graves' disease may present clinically with one of the following characteristic signs: | |||

| *] (protuberance of one or both eyes) | |||

| *fatigue, weight loss with increased appetite, and other symptoms of ]/] | |||

| *rapid heart beats | |||

| *muscular weakness | |||

| The two signs that are truly 'diagnostic' of Graves' disease ''(i.e.,'' not seen in other hyperthyroid conditions) are ] and non-pitting edema (]). Goitre is an enlarged thyroid gland and is of the diffuse type (''i.e.,'' spread throughout the gland). Diffuse goitre may be seen with other causes of hyperthyroidism, although Graves' disease is the most common cause of diffuse goitre. A large goitre will be visible to the naked eye, but a smaller goitre (very mild enlargement of the gland) may be detectable only by physical exam. Occasionally, goitre is not clinically detectable but may be seen only with ] or ] examination of the thyroid. | |||

| Thus, despite ongoing research, a complete understanding of the causes of mental disability in Graves’ disease awaits a full description of the effects on neural tissue of thyroid hormones, as well as of the underlying autoimmune process.<ref name="pmid15763125"/> | |||

| Another sign of Graves' disease is ], ''i.e.'', overproduction of the ]s T3 and T4. Normothyroidism is also seen, and occasionally also ], which may assist in causing goitre (though it is not the cause of the Graves' disease). Hyperthyroidism in Graves' disease is confirmed, as with any other cause of hyperthyroidism, by measuring elevated blood levels of free (unbound) T3 and T4. | |||

| ==Pathophysiology== | |||

| In Graves' disease, an ] disorder, the body produces ] to the TSH-Rs. (Antibodies to ] and to the ]s T3 and T4 may also be produced.) These antibodies (TSHR-Ab) bind to the TSH-Rs, which are located on the cells that produce thyroid hormone in the thyroid gland (]), and ] stimulate them, resulting in an abnormally high production of T3 and T4. This causes the clinical symptoms of hyperthyroidism, and the enlargement of the thyroid gland (visible as ]). | |||

| Other useful laboratory measurements in Graves' disease include ] (TSH, usually low in Graves' disease due to ] from the elevated T3 and T4), and protein-bound ] (elevated). Thyroid-stimulating antibodies may also be detected ]. | |||

| The infiltrative ], frequently encountered, has been explained by postulating the thyroid gland and the ] share common ]s recognized by the antibodies. Antibodies binding to the extraocular muscles would cause swelling behind the eyeball. This swelling may be the consequence of mucopolysacharide deposition posterior to the eyes, a symptom tangentially related to Graves'. The "orange peel" skin has been explained by the infiltration of antibodies under the skin, causing an inflammatory reaction and subsequent fibrous plaques. | |||

| ] to obtain histiological testing is not normally required but may be obtained if thyroidectomy is performed.<!-- see eMedicine/med/topic929 of infobox --> | |||

| Three types of autoantibodies to the TSH-R are currently recognized: | |||

| Differentiating two common forms of hyperthyroidism such as Graves' disease and ] is important to determine proper treatment. Measuring TSH-receptor antibodies with the h-TBII assay has been proven efficient and was the most practical approach found in one study.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Wallaschofski H, Kuwert T, Lohmann T |title=TSH-receptor autoantibodies - differentiation of hyperthyroidism between Graves' disease and toxic multinodular goiter |journal=Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes |volume=112 |issue=4 |pages=171–4 |year=2004 |pmid=15127319 |doi=10.1055/s-2004-817930 |url=}}</ref> | |||

| *Thyroid-stimulating ]s (mainly ]) act as long-acting thyroid stimulants, activating the cells in a longer and slower way than the normal thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), leading to an elevated production of thyroid hormone. | |||

| ===Eye disease=== | |||

| *Thyroid growth immunoglobulins bind directly to the TSH-Rs, and have been implicated in the growth of ]. | |||

| {{See|Graves' ophthalmopathy|}} | |||

| Thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy is one of the most typical symptoms of Graves' disease. It is known by a variety of terms, the most common being ]. Thyroid eye disease is an inflammatory condition, which affects the orbital contents including the ] and orbital fat. It is almost always associated with Graves' disease but may rarely be seen in ], primary ], or ]. | |||

| The ocular manifestations that are relatively specific to Graves' disease include soft tissue inflammation, proptosis (protrusion of one or both globes of the eyes), ]l exposure, and ] compression. Also seen, if the patient is hyperthyroid, (''i.e.'', has too much thryoid hormone) are more general manifestations, which are due to hyperthyroidism itself and which may be seen in any conditions that cause hyperthyroidism (such as toxic multinodular goitre or even thyroid poisoning). These more general symptoms include lid retraction, lid lag, and a delay in the downward excursion of the upper eyelid, during downward gaze. | |||

| *] binding-inhibiting immunoglobulins inhibit the normal union of TSH with its receptor. Some will actually act as if TSH itself is binding to its receptor, thus inducing thyroid function. Other types may not stimulate the thyroid gland, but will prevent thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin and TSH from binding to and stimulating the receptor. | |||

| It is believed that fibroblasts in the orbital tissues may express the Thyroid Stimulating Hormone receptor (TSHr). This may explain why one autoantibody to the TSHr can cause disease in both the thyroid and the eyes.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.liebertonline.com/doi/abs/10.1089/thy.2007.0185 |title=Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. - Thyroid - 17(10):1013 |doi=10.1089/thy.2007.0185 |publisher=Liebertonline.com |date= |accessdate=2009-06-03}}</ref> | |||

| In their study of thyrotoxic patients, Sensenbach ''et al.'' found ] is increased, cerebral vascular resistance is decreased, ] is decreased, and oxygen consumption is unchanged. They found, during treatment, ] was decreased significantly, and ventricular size was increased. The cause of this remarkable change is unknown, but may involve osmotic regulation.<ref>{{Cite journal| author = Sensenbach W, Madison L, Eisenberg S, Ochs L | title = The Cerebral Circulation and Metabolism in Hyperthyroidism and Myxedema | journal = J Clin Invest | volume = 33 | page = 1434 | year = 1954 | pmid = 13211797 | issue = 11 | doi = 10.1172/JCI103021 | pmc = 1072568| pages = 1434–40}}</ref> A study by Singh ''et al''. showed for the first time that differential thyroidal status induces ] in adult ]. ] acts directly on cerebral cortex ] and induces release of ] to induce apoptosis. The adult ] seems to be less responsive to changes in thyroidal status.<ref name="ReferenceC"/> | |||

| ====Classification of Graves' eye disease==== | |||

| Hyperthyroidism causes lower levels of ] (A), ], and ratio of total/HDL ].<ref name="ThyroidManager-Ch10-Groot"/> The processes and pathways mediating the intermediary metabolism of ], ], and ] are all affected by thyroid hormones in almost all tissues.<ref>{{Cite journal| title = Metabolic effects of thyroid hormone derivatives | author = Moreno M, de Lange P, Lombardi A, Silvestri E, Lanni A, Goglia F. | journal = Thyroid | year = 2008 | volume = 18 | issue = 2 | pages = 239–53 | pmid = 18279024 | doi = 10.1089/thy.2007.0248}}</ref> Protein formation and destruction are both accelerated in hyperthyroidism. The absorption of ] is increased and conversion of ] to vitamin A is accelerated (the requirements of the body are likewise increased, and low blood concentrations of vitamin A may be found). Requirements for ] and ] and ] are increased. Lack of the B vitamins has been implicated as a cause of ] in thyrotoxicosis.<ref name="ThyroidManager-Ch10-Groot"/> Hyperthyroidism can also augment calcium levels in the blood by as much as 25% (]). An increased excretion of ] and ] in the urine and stool can result in bone loss from ].<ref name="medicinenet">{{Cite web|author=Mathur R |title=Thyroid Disease, Osteoporosis, and Calcium |url=http://www.medicinenet.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=18637 |publisher=MedicineNet |date=12/7/2006 |accessdate=2010-05-03}}</ref> Also, parathyroid hormone levels tend to be suppressed in hyperthyroidism, possibly in response to elevated calcium levels.<ref>Bouillon R, DeMoor P: Parathyroid function in patients with hyper- or hypothyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 38:999, 1974</ref> | |||

| Mnemonic: "NO SPECS":<ref name="pmid15310608">{{cite journal | author = Cawood T, Moriarty P, O'Shea D | title = Recent developments in thyroid eye disease | journal = BMJ | volume = 329 | issue = 7462 | pages = 385–90 | year = 2004 | month = August | pmid = 15310608 | pmc = 509348 | doi = 10.1136/bmj.329.7462.385 | url = }}</ref> | |||

| ==Diagnosis== | |||

| ]]] | |||

| Class 0: No signs or symptoms | |||

| The onset of Graves' disease symptoms is often insidious; the intensity of symptoms can increase gradually for a long time before the patient is correctly diagnosed with Graves’ disease, which may take months or years.<ref name="pmid15538931"/> (Not only Graves' disease, but most endocrinological diseases also have insidious, subclinical onsets.<ref>{{Cite journal| doi = 10.1016/0022-3999(90)90104-C | author = Jadresic | title = Psychiatric aspects of hyperthyroidism | journal = Journal of psychosomatic research | year = 1990 | volume = 34 | issue = 6 | pages = 603–615 | pmid = 2290133}}</ref>) One study puts the average time for diagnosis at 2.9 years, having observed a range from three months to 20 years in their sample population.<ref name="pmid15763125">{{Cite journal|author=Bunevicius R, Velickiene D, Prange AJ |title=Mood and anxiety disorders in women with treated hyperthyroidism and ophthalmopathy caused by Graves' disease |journal=Gen Hosp Psychiatry |volume=27 |issue=2|pages=133–9 |year=2005 |pmid=15763125 |doi=10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2004.10.002 |url=}}</ref> A 1996 study offers a partial explanation for this generally late diagnosis, suggesting the psychiatric symptoms cause delays in seeking treatment, as well as delays in receiving appropriate diagnosis.<ref name="pmid9081554"/> Also, earlier symptoms of nervousness, hyperactivity, and a decline in school performance, may easily be attributed to other causes. Many symptoms may occasionally be noted, at times, in otherwise healthy individuals who do not have thyroid disease (e.g., everyone feels anxiety and tension to some degree), and many thyroid symptoms are similar to those of other diseases.<ref name="MyThyroid">{{Cite web|author=Druckerhttp D |title=Hyperthyroidism |url=http://www.mythyroid.com/hyperthyroidism.html |work=MyThyroid.com |year=2005 |accessdate=2010-05-03}}</ref> Thus, clinical findings may be full-blown and unmistakable or insidious and easily confused with other disorders.<ref>Felz, The many faces of Graves’ disease, -part 1, Postgraduate medicine online, 1999, 106(4), 57-64.</ref> The results of overlooking the thyroid can, however, be very serious.<ref name="ReferenceA">{{Cite journal|author=Awad AG|title=The Thyroid and the Mind and Emotions/Thyroid Dysfunction and Mental Disorders |url=http://www.thyroid.ca/e10f.php |journal=Thyrobulletin, Thryoid Foundation of Canada |volume=7 |year=2000 |accessdate=2010-05-06 |issue=3}}</ref> Also noteworthy and problematic, in a 1996 survey, study respondents reported a significant decline in memory, attention, planning, and overall productivity from the period two years prior to Graves' symptoms onset.<ref name="pmid9081554"/> Also, hypersensitivity of the ] to low-grade hyperthyroidism can result in an ] before other Graves’ disease symptoms emerge. ], for example, has been reported to precede Graves’ hyperthyroidism by four to five years in some cases, although it is not known how frequently this occurs.<ref>{{cite journal | doi = 10.1159/000289088 | last1 = Matsubayashi | first1 = S | last2 = Tamai | first2 = H | last3 = Matsumoto | first3 = Y | author-separator =, | author-name-separator= | last4 = Tamagawa| year = 1996 | first4 = K | last5 = Mukuta | first5 = T | last6 = Morita | first6 = T | last7 = Kubo | first7 = C | title = Graves' disease after the onset of panic disorder | url = | journal = Psychother Psychosom | volume = 65 | issue = 5| pages = 277–80 | pmid = 8893330 }}</ref> | |||

| Class 1: Only signs (limited to upper lid retraction and stare, with or without lid lag) | |||

| The hyperthyroidism from Graves' disease causes a wide variety of symptoms. The two signs are truly 'diagnostic' of Graves' disease (i.e., not seen in other hyperthyroid conditions), ] (protuberance of one or both eyes) and ], a rare skin disorder with an occurrence rate of 1-4%, that causes lumpy, reddish skin on the lower legs. Graves' disease also causes goitre (a diffuse enlargement of the thyroid gland). Though it also occurs with other causes of hyperthyroidism, Graves' disease is the most common cause of diffuse goitre. A large goitre is visible to the naked eye, but a smaller goitre may be detectable only by a physical exam. On occasion, goitre is not clinically detectable, but may be seen only with ] or ] examination of the thyroid. | |||

| Class 2: Soft tissue involvement (oedema of conjunctivae and lids, conjunctival injection, etc.) | |||

| A highly suggestive symptom of hyperthyroidism, is a change in reaction to external temperature. A hyperthyroid person will usually develop a preference for cold weather, a desire for less clothing and less bed covering, and a decreased ability to tolerate hot weather.<ref name="ThyroidManager-Ch10-Groot"/> When thyroid disease runs in the family, the physician should be particularly wary; studies of twins suggest genetic factors account for 79% of the liability to the development of Graves’ disease (whereas environmental factors presumably account for the remainder).<ref name="ThyroidManager-Ch10-Groot"/> Other, nearly ] signs of hyperthyroidism are excessive sweating, high pulse during sleep, and a pattern of weight loss with increased appetite (although this may also occur in ] and ] or ]).<ref name="ThyroidManager-Ch10-Groot"/><ref name="ReferenceB">Psychische stoornissen bij endocriene zieken, 1983, C. van der Meer en W. van Tilburg (red.)</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| Hyperthyroidism in Graves' disease is confirmed, as with any other cause of hyperthyroidism, by a blood test. Elevated blood levels of the principal thyroid hormones (''i.e.'' free T3 and T4), and a suppressed ] (low due to ] from the elevated T3 and T4), point to hyperthyroidism. However, diagnosis depends to a considerable extent on the position of the patient’s unique set point for T4 and T3 within the laboratory reference range (an important issue that is further elaborated ]).<ref name="pmid11889165">{{Cite journal|author=Andersen S, Pedersen KM, Bruun NH, Laurberg P |title=Narrow individual variations in serum T(4) and T(3) in normal subjects: a clue to the understanding of subclinical thyroid disease |journal=J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. |volume=87 |issue=3 |pages=1068–72 |year=2002 |month=March |pmid=11889165 |doi= 10.1210/jc.87.3.1068|url=http://jcem.endojournals.org/cgi/content/full/87/3/1068}}</ref> | |||

| Class 3: Proptosis | |||

| Differentiating Graves' hyperthyroidism from the other causes (], ], ], and excess thyroid hormone supplementation) is important to determine proper treatment. Thus, when hyperthyroidism is confirmed, or when blood results are inconclusive, thyroid antibodies should be measured (almost all patients with Graves' hyperthyroidism have detectable TSHR-Ab levels).<ref>Clinical value of M22-based assays for TSH-receptor antibody (TRAb) in the follow-up of antithyroid drug treated Graves' disease: comparison with the second generation human TRAb assay. Massart C, Gibassier J, d'Herbomez M - Clin Chim Acta. 2009 Sep;407(1-2):62-6. Epub 2009 Jul 1.</ref> Measurement of thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin (TSI) is the most accurate measure of thyroid antibodies. They will be positive in 60 to 90% of children with Graves' disease. If TSI is not elevated, then a radioactive iodine uptake should be performed; an elevated result with a diffuse pattern is typical of Graves' disease.<ref>Bioassay of thyrotropin receptor antibodies with Chinese hamster ovary cells transfected with recombinant human thyrotropin receptor: clinical utility in children and adolescents with Graves disease. Botero D, Brown RS - J Pediatr. 1998;132(4):612.</ref> ] to obtain ] testing is not normally required, but may be obtained if ] is performed.<!-- see eMedicine/med/topic929 of infobox --> | |||

| Class 4: Extraocular muscle involvement (usually with diplopia) | |||

| ==Treatment== | |||

| Means to interrupt the autoimmune processes of Graves' disease are unknown, so treatment must be indirect. The thyroid gland is the target, via three different methods (which have not changed fundamentally since the 1940s): ] (which reduce the production of ]), partial or complete destruction of the thyroid gland by ingestion of radioactive iodine (]), and partial or complete surgical removal of the thyroid gland (]). | |||

| Class 5: Corneal involvement (primarily due to lagophthalmos) | |||

| No treatment for Graves' hyperthyroidism is preferred; it is not straightforward and often involves complex decision-making. The physician must weigh the advantages and disadvantages of the different treatment options and help the patient arrive at an individualized, appropriate and cost-effective therapeutic strategy. Kaplan summarizes, "the choice of therapy varies according to nonbiological factors - physicians' training and personal experience; local and national practice patterns; patient, physician, and societal attitudes toward radiation exposure; and biological factors including age, reproductive status, and severity of the disease".<ref>Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America, KAPLAN ed., Vol 27, no. 1, march 1998, 4.</ref> | |||

| Class 6: Sight loss (due to optic nerve involvement) | |||

| Therapy with radioiodine is the most common treatment in the United States, while antithyroid drugs and/or thyroidectomy are used more often in Europe, Japan, and most of the rest of the world. However, due to the varying success of every treatment option, patients are often subjected to more than one when the first attempted treatment does not prove entirely successful; the risk of relapse or subsequent hypothyroidism is substantial.<ref name="emedicine.medscape">eMedicine - Hyperthyroidism, Robert J Ferry Jr </ref> | |||

| ====Treatment specific to eye problems==== | |||

| In the short term, treatment of hyperthyroidism usually produces a parallel decrease in endocrine and psychiatric symptoms. When prolonged treatment normalizes thyroid function, some psychiatric symptoms and somatic complaints may persist.<ref name="pmid15763125"/> In spite of modern therapeutic modalities, Graves' disease is accompanied by seriously impaired quality of life. Several recent studies stress the importance of early prevention, speedy rehabilitation, and thorough follow-up of hyperthyroid patients.<ref>{{cite journal |title=Graves' Disease: Quality Of Life And Occupational Disability |first=Katharina |last=Ponto |last2=''et al.'' |journal=Dtsch Arztebl, Int |year=2009 |volume=106 |issue=17 |pages=283–289 |doi=10.3238/arztebl.2009.0283 |pmid=19547630 |pmc=2689575}}</ref> Patients who do not have a spontaneous remission with the use of antithyroid drugs become lifelong thyroid patients. | |||

| *For mild disease - ]s, steroids (to reduce ]) | |||

| *For moderate disease - lateral ] | |||

| *For severe disease - orbital decompression or retro-orbital radiation | |||

| ===Other Graves' disease symptoms=== | |||

| ===Symptomatic=== | |||

| Some of the most typical symptoms of Graves' Disease are included in the following list. All but the eye-related problems and goitre are due to the effects of too much thyroid hormone, and are seen in other hyperthyroid states, including simple thyroid hormone poisoning: | |||

| ] therapy]] | |||

| {{Multicol}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] (rapid heart rate: 100-120 beats per minute, or higher) | |||

| * ] (irregular heart beat) | |||

| * ] (Raised blood pressure) | |||

| * ] (usually fine shaking, e.g., hands) | |||

| * ] (excessive sweating) | |||

| * Heat intolerance | |||

| * ] (increased appetite) | |||

| * Unexplained ] despite increased appetite | |||

| * ] (shortness of breath) | |||

| * ] (especially in the large muscles of the arms and legs) and degeneration | |||

| * Diminished/changed ] | |||

| * ] (inability to get enough sleep) | |||

| {{Multicol-break}} | |||

| * Increased energy | |||

| * ] | |||

| * Mental impairment, memory lapses, diminished attention span | |||

| * Decreased concentration | |||

| * ], agitation | |||

| * ] | |||

| * Restlessness | |||

| * Erratic behavior | |||

| * Emotional ] | |||

| * Brittle nails | |||

| * Abnormal breast enlargement | |||

| * ] (enlarged thyroid gland) | |||

| * Protruding eyeballs | |||

| * ] (double vision) | |||

| {{Multicol-break}} | |||

| * Eye pain, irritation, tingling sensation behind the eyes or the feeling of grit or sand in the eyes | |||

| * Swelling or redness of eyes or eyelids/eyelid retraction | |||

| * ] | |||

| * Decrease in ] (]), irregular and scant menstrual flow (]) | |||

| * Difficulty conceiving/]/recurrent ] | |||

| * Chronic ] | |||

| * Lumpy, reddish skin of the lower legs (]) | |||

| * Increased bowel movements or ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * | |||

| {{Multicol-end}} | |||

| ==Incidence and epidemiology== | |||

| ]s (such as ]) may be used to inhibit the ] symptoms of ] and nausea until antithyroid treatments start to take effect. | |||

| ] therapy.]] | |||

| The disease occurs most frequently in women (7:1 compared to men). It occurs most often in middle age (most commonly in the third to fifth decades of life), but is not uncommon in adolescents, during pregnancy, during ], or in people over age 50. There is a marked family preponderance, which has led to speculation that there may be a genetic component. To date, no clear genetic defect has been found that would point at a ] cause. | |||

| ==Pathophysiology== | |||

| ===Antithyroid drugs=== | |||

| Graves' disease is an ] disorder, in which the body produces ] to the ]. (Antibodies to thyroglobulin and to the ]s T3 and T4 may also be produced.) | |||

| {{Further|Antithyroid agents in Grave's disease}} | |||

| The main antithyroid drugs are ] (in the UK), ] (in the US), and ] (PTU). These drugs block the binding of iodine and coupling of iodotyrosines. The most dangerous side effect is ]. Others include ] (dose dependent, which improves on cessation of the drug) and ], and for PTU, severe, fulminant liver failure.<ref name="FDA PTU Guidelines">{{cite journal | last1 = Bahn | first1 = RS | last2 = Burch | first2 = HS | last3 = Cooper | first3 = DS | last4 = Garber | first4 = JR | last5 = Greenlee | first5 = CM | last6 = Klein | first6 = IL | last7 = Laurberg | first7 = P | last8 = McDougall | first8 = IR | last9 = Rivkees | first9 = SA | title = The Role of Propylthiouracil in the Management of Graves' Disease in Adults: report of a meeting jointly sponsored by the American Thyroid Association and the Food and Drug Administration | url = http://www.liebertonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1089/thy.2009.0169 | pmid = 19583480 | author-separator =, | journal = Thyroid : official journal of the American Thyroid Association | author-name-separator= | doi=10.1089/thy.2009.0169 | volume=19 | issue=7 | year=2009 | month=July | pages=673–4}}</ref> Patients on these medications should see a doctor if they develop sore throat or fever. | |||

| These antibodies cause ] because they bind to the TSH receptor and ] stimulate it. The TSH receptor is expressed on the ] of the thyroid gland (the cells that produce thyroid hormone), and the result of chronic stimulation is an abnormally high production of T3 and T4. This in turn causes the clinical symptoms of ], and the enlargement of the thyroid gland visible as ]. | |||

| The infiltrative ] that is frequently encountered has been explained by postulating that the thyroid gland and the extraocular muscles share a common antigen which is recognized by the antibodies. Antibodies binding to the extraocular muscles would cause swelling behind the eyeball. | |||

| Treatment with ] must be given for six months to two years to be effective. Success rates vary from 34% to 64%, but even then, the hyperthyroid state may recur, sometimes upon cessation of the drugs, or sometimes months or years later.<ref name="emedicine.medscape" /> If treatment with antithyroid drugs fails to induce remission, radioiodine or surgery must be considered. | |||

| The "orange peel" skin has been explained by the infiltration of antibodies under the skin, causing an inflammatory reaction and subsequent fibrous plaques. | |||

| ===Radioiodine=== | |||

| {{See also|Iodine-131}} | |||

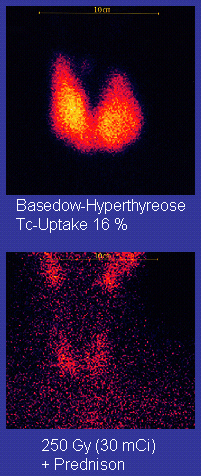

| ] (radioactive ], RAI) was developed in the early 1940s at the ]. This modality is suitable for most patients, although some doctors prefer to use it mainly for older patients. Indications for RAI are failed medical therapy or surgery, or where medical or surgical therapies are contraindicated. Contraindications to RAI are ] (absolute), ophthalmopathy (relative; it can aggravate thyroid eye disease), and ]. | |||

| There are 3 types of autoantibodies to the TSH receptor currently recognized: | |||

| RAI treatment acts slowly (over months to years) to partially or completely destroy the thyroid gland (depending on the administered dose), so patients must be monitored regularly with thyroid blood tests to ensure they do not evolve to ] (incidence rate of 80%), in which case they will become lifelong thyroid hormone patients. Graves' disease-associated hyperthyroidism is not cured in all persons by radioiodine, but its relapse rate depends on the administered dose of radioiodine. | |||

| *''TSI'', Thyroid stimulating immunoglobulins: these antibodies (mainly IgG) act as LATS (Long Acting Thyroid Stimulants), activating the cells in a longer and slower way than TSH, leading to an elevated production of thyroid hormone. | |||

| Treatment with radioiodine has a substantial risk of exacerbating pre-existing thyroid eye disease. Patients without clinicaly evident thyroid eye disease have an 8% risk of developing ophthalmopathy, and a risk lower than 1% of developping severe eye disease.<ref>http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1116221/</ref> | |||

| *''TGI'', Thyroid growth immunoglobulins: these antibodies bind directly to the TSH receptor and have been implicated in the growth of thyroid follicles. | |||

| ===Surgery=== | |||

| {{See also|Thyroidectomy}} | |||

| ] | |||

| This modality is suitable for young patients and pregnant patients. Indications are a large goitre (especially when compressing the ]), suspicious nodules or suspected ] (to pathologically examine the thyroid) and patients with ophthalmopathy. As operating on a frankly hyperthyroid patient is dangerous, prior to thyroidectomy, preoperative treatment with antithyroid drugs is given to render the patient "euthyroid". Preoperative administration of (not radioactive) iodine, usually by ] solution, decreases intraoperative blood loss during thyroidectomy in patients with Grave's disease.<ref>{{Cite journal|author=Erbil Y, Ozluk Y, Giriş M, ''et al.'' |title=Effect of lugol solution on thyroid gland blood flow and microvessel density in the patients with Graves' disease |journal=J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. |volume=92 |issue=6 |pages=2182–9 |year=2007 |month=June |pmid=17389702 |doi=10.1210/jc.2007-0229 |url=}}</ref> However, it appears ineffective in patients who are already euthyroid due to treatment with antithyroid drugs and ].<ref>{{Cite journal|author=Kaur S, Parr JH, Ramsay ID, Hennebry TM, Jarvis KJ, Lester E |title=Effect of preoperative iodine in patients with Graves' disease controlled with antithyroid drugs and thyroxine |journal=Ann R Coll Surg Engl |volume=70 |issue=3 |pages=123–7 |year=1988 |month=May |pmid=2457351 |pmc=2498739 |doi= |url=}}</ref> | |||

| *''TBII'', Thyrotrophin Binding-Inhibiting Immunoglobulins: these antibodies inhibit the normal union of TSH with its receptor. Some will actually act as if TSH itself is binding to its receptor, thus inducing thyroid function. Other types may not stimulate the thyroid gland, but will prevent TSI and TSH from binding to and stimulating the receptor. | |||

| Doctors can opt for partial or total removal of the thyroid gland (subtotal versus total thyroidectomy). A total removal excludes the difficulty in determining how much thyroid tissue must be removed. More aggressive surgery has a higher likelihood of inducing hypothyroidism; less aggressive surgery has a higher likelihood of recurrent hyperthyroidism.<ref>Thyroid function after surgical treatment of thyrotoxicosis. A report of 100 cases treated with propranolol before operation. Toft AD, Irvine WJ, Sinclair I, McIntosh D, Seth J, Cameron EH. N Engl J Med. 1978;298(12):643; The influence of remnant size, antithyroid antibodies, thyroid morphology, and lymphocyte infiltration on thyroid function after subtotal resection for hyperthyroidism. JörtsöE, Lennquist S, Lundström B, Norrby K, Smeds S, World J Surg. 1987;11(3):365.</ref> Around 10–15% of patients who had a subtotal thyrodectomy will develop underactive thyroids many years after their operations, not including those who develop underactive thyroids immediately after the operation (within six weeks).<ref>Newsletter of Thyroid Australia Ltd Volume 3 No 3 July 2002</ref> Thyroid remnants smaller than 4 g are associated with postoperative hypothyroidism in 27 to 99% of patients. Patients who have thyroid remnants of 7 to 8 g become euthyroid, but may have subclinical hyperthyroidism. In addition, 9 to 12% develop recurrent overt hyperthyroidism.<ref>The influence of remnant size, antithyroid antibodies, thyroid morphology, and lymphocyte infiltration on thyroid function after subtotal resection for hyperthyroidism. JörtsöE, Lennquist S, Lundström B, Norrby K, Smeds S, World J Surg. 1987;11(3):365</ref> As repeat surgery is associated with a high risk of complications, further permanent treatment should be with radioiodine.].]] | |||

| Another effect of hyperthyroidism is bone loss from osteoporosis, caused by an increased excretion of calcium and phosphorus in the urine and stool. The effects can be minimized if the hyperthyroidism is treated early. Thyrotoxicosis can also augment calcium levels in the blood by as much as 25%. This can cause stomach upset, excessive urination, and impaired kidney function.<ref>http://www.medicinenet.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=18637</ref> | |||

| In a study of 380 patients undergoing a 98% subtotal thyroidectomy, several complications were found to occur<ref>Surgical treatment of hyperthyroidism: a ten-year experience. Werga-Kjellman P, Zedenius J, Tallstedt L, Träisk F, Lundell G, Wallin G, Thyroid. 2001;11(2):187.</ref>: | |||

| * Transient ] in 3% | |||

| * Prolonged postoperative ] in 3% | |||

| * Permanent ] in 1% (due to removal of one or more ]) | |||

| * Recurrent hyperthyroidism in 2% | |||

| ==Etiology== | |||

| A ] is created across the neck just above the ] line, but it is very thin, and eventually recedes to appear as nothing more than a crease in the neck. A patients may spend one or more nights in hospital after the surgery, and endure the effects of ] (''i.e.'', vomiting), as well as a sore throat, a raspy voice, and a cough from having an ] inserted in the ] during surgery.{{Citation needed|date=July 2009}} | |||

| The trigger for auto-antibody production is not known. There appears to be a ] predisposition for Graves' disease, suggesting that some people are more prone than others to develop TSH receptor activating antibodies due to a genetic cause. ] DR (especially DR3) appears to play a significant role.<!-- | |||

| --><ref name="EndocrReview1993">{{cite journal | author = Tomer Y, Davies T | title = Infection, thyroid disease, and autoimmunity. | journal = Endocr Rev | volume = 14 | issue = 1 | pages = 107–20 | year = 1993 | pmid = 8491150 | url=http://edrv.endojournals.org/cgi/reprint/14/1/107.pdf | format=PDF | doi = 10.1210/er.14.1.107}}</ref> | |||

| Since Graves' disease is an autoimmune disease which appears suddenly, often quite late in life, it is thought that a ] or ]l infection may trigger antibodies which cross-react with the human TSH receptor (a phenomenon known as ], also seen in some cases of ]){{Citation needed|date=March 2010}} | |||

| Removal of the gland enables complete biopsy to be performed to have definitive evidence of ], since needle biopsies are not as accurate at predicting a benign thyroid state. No further treatment of the thyroid is required, unless cancer is detected. Radioiodine treatment may be done after surgery, to ensure all remaining (potentially cancerous) thyroid cells are destroyed (i.e., those near the nerves to the ], which cannot be surgically removed without damage to those cords). Besides this, the only remaining treatment will be thyroid replacement pills (to be taken for the rest of the patient's life), if the surgery results in hypothyroidism. | |||

| . | |||

| One possible culprit is the bacterium '']'' (a cousin of '']'', the agent of bubonic plague). However, although there is indirect evidence for the structural similarity between the bacteria and the human thyrotropin receptor, direct causative evidence is limited.<!-- | |||

| ===Thyroid hormones=== | |||

| --><ref name="EndocrReview1993"/> | |||

| ] | |||

| ''Yersinia'' seems not to be a major cause of this disease, although it may contribute to the development of thyroid autoimmunity arising for other reasons in genetically susceptible individuals.<!-- | |||

| {{See also|Hypothyroidism#Treatment}} | |||

| --><ref>{{cite journal | author = Toivanen P, Toivanen A | title = Does Yersinia induce autoimmunity? | journal = Int Arch Allergy Immunol | volume = 104 | issue = 2 | pages = 107–11 | year = 1994 | pmid = 8199453}}</ref> | |||

| Many Graves' disease patients will become lifelong thyroid patients due to the surgical removal or radioactive destruction of their thyroid glands. In effect, they are then hypothyroid patients, requiring perpetual intake of artificial thyroid hormones.<ref name="pmid10874537">{{Cite journal|author=Ayala AR, Danese MD, Ladenson PW |title=When to treat mild hypothyroidism |journal=Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North Am. |volume=29 |issue=2 |pages=399–415 |year=2000 |month=June |pmid=10874537 |doi= 10.1016/S0889-8529(05)70139-0|url=}}</ref> Given the one-week plasma half-life of ] (T4), it takes about five to six weeks (half-lives) before a steady state is attained after the dosage is initiated or changed. After the optimal thyroxine dose has been defined, long-term monitoring of patients with an annual clinical evaluation and serum TSH measurement is appropriate.<ref name="pmid10874537"/> However, the difficulty lies in determining and controlling the proper dosage for a particular patient, which can be an intricate process. Because levothyroxine has a very narrow therapeutic index, the margin between overdosing and underdosing can be quite small.<ref>TSH levels are altered by the timing of levothyroxine administration Bach-Huynh TG, Nayak B, Loh J, Soldin S, Jonklaas J - J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009; July 7 - Commentary by Jennifer Sipos, </ref> Being treated with too much or too little thyroid hormone can lead to a chronic state of (possibly subclinical) hypo- or hyperthyroidism. Several studies show this is not an uncommon occurrence.<ref name="pmid10695693">{{Cite journal|author=Canaris GJ, Manowitz NR, Mayor G, Ridgway EC |title=The Colorado thyroid disease prevalence study |journal=Arch. Intern. Med. |volume=160 |issue=4 |pages=526–34 |year=2000 |month=February |pmid=10695693 |doi= 10.1001/archinte.160.4.526|url=}}</ref><ref name="pmid19126628">{{Cite journal|author=Somwaru LL, Arnold AM, Joshi N, Fried LP, Cappola AR |title=High Frequency of and Factors Associated with Thyroid Hormone Over-Replacement and Under-Replacement in Men and Women Aged 65 and Over |journal=J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. |volume=94 |issue=4 |pages=1342–5 |year=2009 |month=April |pmid=19126628 |pmc=2682480 |doi=10.1210/jc.2008-1696 |url=http://www.thyroid.org/professionals/publications/clinthy/volume21/issue4/clinthy_v214_3_5.pdf |format=PDF}}</ref><ref name="pmid11836274">{{Cite journal|author=Hollowell JG, Staehling NW, Flanders WD, ''et al.'' |title=Serum TSH, T(4), and thyroid antibodies in the United States population (1988 to 1994): National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) |journal=J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. |volume=87 |issue=2 |pages=489–99 |year=2002 |month=February |pmid=11836274 |doi= 10.1210/jc.87.2.489|url=http://jcem.endojournals.org/cgi/content/full/87/2/489}}</ref> | |||

| It has also been suggested that ''Y. enterocolitica'' infection is not the cause of auto-immune thyroid disease, but rather is only an ] condition; with both having a shared inherited susceptibility.<!-- yes this is true | |||

| --><ref>{{cite journal | author = Strieder T, Wenzel B, Prummel M, Tijssen J, Wiersinga W | title = Increased prevalence of antibodies to enteropathogenic ''Yersinia enterocolitica'' virulence proteins in relatives of patients with autoimmune thyroid disease. | journal = Clin Exp Immunol | volume = 132 | issue = 2 | pages = 278–82 | year = 2003 | pmid = 12699417 | doi = 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2003.02139.x}}</ref> | |||

| More recently the role for ''Y. enterocolitica'' has been disputed.<!-- | |||

| --><ref>{{cite journal | author = Hansen P, Wenzel B, Brix T, Hegedüs L | title = Yersinia enterocolitica infection does not confer an increased risk of thyroid antibodies: evidence from a Danish twin study. | journal = Clin Exp Immunol | volume = 146 | issue = 1 | pages = 32–8 | year = 2006 | pmid = 16968395 | doi = 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03183.x}}</ref> | |||

| ==Treatment== | |||

| ===Neuropsychiatric symptoms=== | |||

| Treatment of Graves' disease includes ] which reduce the production of ], ] (radioactive iodine ]), and ] (surgical excision of the gland). As operating on a frankly hyperthyroid patient is dangerous, prior to thyroidectomy preoperative treatment with antithyroid drugs is given to render the patient "euthyroid" (''i.e.'' normothyroid). | |||

| A substantial proportion of patients have altered mental states, even after successful treatment of hyperthyroidism. When psychiatric disorders remain after restoration of euthyroidism and after treatment with ], specific treatment for the psychiatric symptoms, especially ], may be needed.<ref name="pmid17044727"/> After being diagnosed with Graves’ hyperthyroidism, approximately one-third of patients are prescribed psychotropic drugs. Sometimes these drugs are given to treat mental symptoms of hyperthyroidism, sometimes to treat mental symptoms remaining after amelioration of hyperthyroidism, and sometimes when the diagnosis of Graves’ hyperthyroidism has been missed and the patient is treated as having a primary psychiatric disorder. There are no systematic data on the general efficacy of psychotropic drugs in the treatment of mental symptoms in patients with hyperthyroidism, although many reports describe the use of individual agents.<ref name="pmid17044727"/> De Groot mentioned a mild ] or ] is often helpful.<ref name="ThyroidManager-Ch11-Groot">Chapter 11. Diagnosis and Treatment of Graves’ Disease Leslie J. De Groot, MD Professor of Medicine - http://www.thyroidmanager.org/Chapter11/chapter11.html Updated: March 5, 2008</ref> German research of 2004 reported 35% of treated Graves' disease patients (with normal thyroid tests for at least six months after treatment) suffered from psychological distress, and had high levels of anxiety. Almost all these patients had clear-cut depression.<ref>Scheffer, Heckmann, Mijic, Rudorff. Chronic Distress Syndrome in Patients with Graves' Disease. Med Klin 99, no.10(2004), 578-84</ref> | |||

| Treatment with antithyroid medications must be given for six months to two years, in order to be effective. Even then, upon cessation of the drugs, the hyperthyroid state may recur. Side effects of the antithyroid medications include a potentially fatal reduction in the level of white blood cells. Therapy with radioiodine is the most common treatment in the United States, whilst antithyroid drugs and/or thyroidectomy is used more often in Europe, Japan, and most of the rest of the world. | |||

| ===Eye disease=== | |||

| {{See also|Graves' ophthalmopathy}} | |||

| Mild cases are treated with lubricant ] or nonsteroidal ] (]) drops. Severe cases threatening vision (] exposure or ] compression) are treated with ] or ]. In all cases, ] is essential. ] can be corrected with prism glasses and surgery (the latter only when the process has been stable for a while). | |||

| ===Antithyroid drugs=== | |||

| Eyelid muscles can become tight, making it impossible to completely close the eyes. This can be treated with lubricant gel at night, or with tape on the eyes to enable full sleep. Eyelid surgery can be performed on upper and/or lower eyelids to reverse the effects of Graves' disease on the eyelids. This surgery involves an incision along the natural crease of the eyelid, and a scraping away of the muscle that holds the eyelid open. The muscle then becomes weaker, which allows the eyelid to extend over the eyeball more effectively. Eyelid surgery helps reduce or eliminate ] symptoms. | |||

| The main antithyroid drugs are ] (in the UK), ] (in the US), and ]/PTU. These drugs block the binding of iodine and coupling of iodotyrosines. The most dangerous side-effect is ] (1/250, more in PTU); this is an idiosyncratic reaction which does not stop on cessation of drug. Others include ] (dose dependent, which improves on cessation of the drug) and ]. Patients on these medications should see a doctor if they develop sore throat or fever. The most common side effects are rash and peripheral neuritis. These drugs also cross the ] and are secreted in breast milk. Lygole is used to block hormone synthesis before surgery. | |||

| A ] testing single dose treatment for Graves' found methimazole achieved euthyroid state more effectively after 12 weeks than did propylthyouracil (77.1% on methimazole 15 mg vs 19.4% in the propylthiouracil 150 mg groups).<ref name="pmid11298092">{{cite journal |author=Homsanit M, Sriussadaporn S, Vannasaeng S, Peerapatdit T, Nitiyanant W, Vichayanrat A |title=Efficacy of single daily dosage of methimazole vs. propylthiouracil in the induction of euthyroidism |journal=Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf) |volume=54 |issue=3 |pages=385–90 |year=2001 |pmid=11298092| doi = 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2001.01239.x}}</ref> | |||

| Orbital decompression can be performed to enable ] to be retracted again. In this procedure, bone is removed from the skull behind the eyes, and space is made for the enlarged muscles and ] to be moved back into the skull. | |||

| A study has shown no difference in outcome for adding thyroxine to antithyroid medication and continuing thyroxine versus placebo after antithyroid medication withdrawal. However two markers were found that can help predict the risk of recurrence. These two markers are a positive ] ] (TSHR-Ab) and smoking. A positive TSHR-Ab at the end of antithyroid drug treatment increases the risk of recurrence to 90% (] 39%, ] 98%), a negative TSHR-Ab at the end of antithyroid drug treatment is associated with a 78% chance of remaining in remission. Smoking was shown to have an impact independent to a positive TSHR-Ab.<ref name="pmid11331213">{{cite journal |author=Glinoer D, de Nayer P, Bex M |title=Effects of l-thyroxine administration, TSH-receptor antibodies and smoking on the risk of recurrence in Graves' hyperthyroidism treated with antithyroid drugs: a double-blind prospective randomized study |journal=Eur. J. Endocrinol. |volume=144 |issue=5 |pages=475–83 |year=2001 |pmid=11331213| doi = 10.1530/eje.0.1440475}}</ref> | |||

| ==Prognosis== | |||

| The disease typically begins gradually, and is ] unless treated.<ref name="ThyroidManager-Ch10-Groot"/> If left untreated, more serious ] could result, including ] and ], ], ]s in pregnancy, and increased risk of a ].<ref name="ThyroidManager-Ch10-Groot"/><ref>{{cite journal | url = http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21195806 | pmid = 21195806 | doi=10.1016/j.autrev.2010.12.004 | volume=10 | issue=6 | title=Do chromosomally abnormal pregnancies really preclude autoimmune etiologies of spontaneous miscarriages? | year=2011 | month=April | author=Gleicher N, Weghofer A, Barad DH | journal=Autoimmun Rev | pages=361–3}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | url = http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19844811 | pmid = 19844811 | doi=10.1007/s12016-009-8180-8 | volume=39 | issue=3 | title=Does the immune system induce labor? Lessons from preterm deliveries in women with autoimmune diseases | year=2010 | month=December | author=Gleicher N | journal=Clin Rev Allergy Immunol | pages=194–206}}</ref> Graves disease is often accompanied by an increase in ], which may lead to ] damage and further heart complications, including loss of the normal heart rhythm (]), which may lead to ].<ref name="ThyroidManager-Ch10-Groot"/> If the eyes are bulging severely enough that the lids do not close completely at night, severe dryness will occur with a very high risk of a secondary ]l infection, which could lead to ]. Pressure on the ] behind the globe can lead to ] defects and vision loss, as well. In severe thyrotoxicosis, a condition frequently referred to as ], the neurologic presentations are more fulminant, progressing if untreated through an agitated ] to ] and ultimately to ]. Untreated Graves' disease can lead to significant ], ] and even ]. However, the long-term history also includes ] in some cases and eventual spontaneous development of ] if ] coexists and destroys the thyroid gland.<ref name="ThyroidManager-Ch10-Groot"/> | |||

| ===Radioiodine=== | |||

| When effective thyroid treatment is begun, the general response is quite favorable; physical symptoms resolve, vitality returns and the ] become efficient again.<ref name="ReferenceA"/> However, symptom relief is usually not immediate and is achieved over time as the treatments take effect and thyroid levels reach stability. In addition, not all symptoms may resolve at the same time. Prognosis also depends on the duration and severity of the disease before treatment. Swedish research reported a lower quality of life for 14 to 21 years after treatment of Graves' disease, with lower mood and lower vitality (regardless of the choice of treatment).<ref>Abraham-Nordling, Torring, Hamberger, Lundell, Tallstedt, Calissendorff, Wallin. Graves' Disease: A long-term quality-of-life follow-up of patients randomized to treatment with antithyroid drugs, radioiodine, or surgery, Thyroid 15, no. 11(2005), 1279-86</ref> | |||

| {{See|Iodine-131|}} | |||

| ] (radioactive ]) was developed in the early 1940s at the ]. This modality is suitable for most patients, although some prefer to use it mainly for older patients. Indications for ] are: failed medical therapy or surgery and where medical or surgical therapy are contraindicated. Hypothyroidism may be a complication of this therapy, but may be treated with thyroid hormones if it appears. Patients who receive the therapy must be monitored regularly with thyroid blood tests to ensure that they are treated with thyroid hormone before they become symptomatically hypothyroid. For some patients, finding the correct thyroid replacement hormone and the correct dosage may take many years and may be in itself a much more difficult task than is commonly understood.{{Citation needed|date=September 2009}} | |||

| Contraindications to RAI are ] (absolute), ophthalmopathy (relative; it can aggravate thyroid eye disease), solitary ]. | |||

| ===Remission and relapses=== | |||

| Patients who have residual mental symptoms have a significantly higher chance of relapse of hyperthyroidism. Patients with recurrent Graves’ hyperthyroidism, compared with patients in remission and healthy subjects, had significantly higher scores on scales related to ] and ], as well as less tolerance of ].<ref name="pmid17044727"/><ref name="pmid15817908"/> A total ] offers the best chance of preventing recurrent hyperthyroidism.<ref>Could total thyroidectomy become the standard treatment for Graves’ disease? Ayhan Koyuncu, Cengiz Aydin, Ömer Topçu, Oruç Numan Gökçe, Şahande Elagöz and Hatice Sebila Dökmetaş - Surgery Today; Volume 40, Number 1 / January, 2010</ref> | |||

| Disadvantages of this treatment are a high incidence of ] (up to 80%) requiring eventual thyroid hormone supplementation in the form of a daily pill(s). The radio-iodine treatment acts slowly (over months to years) to destroy the thyroid gland, and Graves' disease-associated hyperthyroidism is not cured in all persons by radioiodine, but has a relapse rate that depends on the dose of radioiodine which is administered. | |||

| ===Mental impairment=== | |||

| Though ] issues exist in the consistency of Graves' disease ], residual complaints in patients who were euthyroid after treatment were reported, with a high prevalence of ] and ], as well as elevated scores on scales of ], ] and psychological distress.<ref name="pmid17044727"/> This "substantial mental disability" is more severe in patients with residual hyperthyroidism, but is present even in euthyroid patients.<ref name="pmid15763125"/> Delay in therapy markedly worsens the prognosis for recovery, and complications can be prevented by early treatment.<ref name="pmid10674283">{{Cite journal|author=Fahrenfort JJ, Wilterdink AM, van der Veen EA |title=Long-term residual complaints and psychosocial sequelae after remission of hyperthyroidism |journal=Psychoneuroendocrinology |volume=25 |issue=2 |pages=201–11 |year=2000 |month=February |pmid=10674283 |doi= 10.1016/S0306-4530(99)00050-5|url=}}</ref> In rare cases, patients will experience ]-like symptoms only after they have been treated for hypo- or hyperthyroidism, due to a rapid normalisation of thyroid hormone levels in a patient who has partly adapted to abnormal values.<ref name="ReferenceB"/> | |||

| ===Surgery=== | |||

| ===Thyroid replacement treatment after thyroidectomy or radioiodine=== | |||

| {{See|Thyroidectomy|}} | |||

| Several studies find a high frequency of TSH level abnormalities in patients who take thyroid hormone supplementation for long periods of time, and stress the importance of periodic assessment of serum TSH.<ref name="pmid19126628"/><ref name="pmid11836274"/> | |||

| This modality is suitable for young patients and pregnant patients. Indications are: a large goitre (especially when compressing the ]), suspicious nodules or suspected ] (to pathologically examine the thyroid) and patients with ophthalmopathy. | |||

| Both bilateral subtotal ] and the Hartley-Dunhill procedure (hemithyroidectomy on one side and partial lobectomy on other side) are possible. | |||

| ==Patient-physician relationship== | |||

| Given the sometimes dramatic impact and long duration of the disease and its treatment, identifying and maintaining ] (which are frequently affected) can help patients and their families cope.<ref name="pmid9081554">{{Cite journal|author=Stern RA, Robinson B, Thorner AR, Arruda JE, Prohaska ML, Prange AJ |title=A survey study of neuropsychiatric complaints in patients with Graves' disease |journal=J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci |volume=8 |issue=2 |pages=181–5 |year=1996 |pmid=9081554 |doi= |url=}}</ref><ref name="ThyroidManager-Ch11-Groot"/> Because ] of the thyrotoxic patient may create interpersonal problems (often producing significant marital stress and conflict), thorough ] of the disease can be invaluable.<ref name="pmid9081554"/><ref name="ThyroidManager-Ch11-Groot"/> In Graves' disease, the accent should lie on written information, as a host of mental problems, such as decreased ] and ], can impair a patient’s ability to absorb details of doctor visits. In a complicated and difficult illness like Graves' disease, physicians should therefore furnish patients with educational materials or resources such as handouts, website links and community support groups.<ref name="PatientPhysician-Summit2003">Defining the Patient-PhysicianRelationship for the 21st Century - 3rd Annual Disease Management - Outcomes Summit October 30 – November 2, 2003 - Phoenix, Arizona </ref> | |||

| Advantages are: immediate cure and potential removal of ]. Its risks are injury of the ], ] (due to removal of the ]s), ] (which can be life-threatening if it compresses the trachea) and ]. Removal of the gland enables complete biopsy to be performed to have definite evidence of cancer anywhere in the thyroid. (Needle biopsies are not so accurate at predicting a benign state of the thyroid). No further treatment of the thyroid is required, unless cancer is detected. Radioiodine treatment may be done after surgery, to ensure that all remaining (potentially cancerous) thyroid cells (''i.e.'', near the nerves to the vocal chords) are destroyed. Besides this, the only remaining treatment will be ], or thyroid replacement pills to be taken for the rest of patient's life. | |||

| However, many patients indicate they are not getting the information they need from the general medical community, and are concerned they do not fully understand their condition.<ref name="isbn1-878398-20-2"/><ref>The Thyroid Sourcebook, Sara Rosenthal</ref> Sympathetic discussion by the physician, possibly with assistance in environmental manipulation, is an important part of the general attack on Graves' disease.<ref name="ThyroidManager-Ch11-Groot"/> ] is the "drug of choice" for prevention and treatment of every medical condition, and open communication with health care professionals can be highly beneficial in maximizing health and outlook on life.<ref name="ThyroidManager-Ch11-Groot"/><ref name="PatientPhysician-Summit2003"/> During the initial and subsequent interviews, the physician must determine the level of the mental and physical stresses. Frequently, major emotional problems come to light after the patient recognizes the sincere interest of the physician. Personal problems can strongly affect therapy by interfering with rest or by causing economic hardship.<ref name="ThyroidManager-Ch11-Groot"/> Physicians are recommended to implement a social ] as part of the initial intake, allowing patients to communicate essential, nonmedical information about their lives.<ref name="PatientPhysician-Summit2003"/> | |||

| Disadvantages are as follows. A scar is created across the neck just above the collar bone line. However, the scar is very thin, and can eventually recede and appear as nothing more than a crease in the neck.Patient may spend a night in hospital after the surgery, and endure the effects of total anesthesia (''i.e.'', vomiting), as well as sore throat, raspy voice, cough from having a breathing tube stuck down the windpipe during surgery.{{Citation needed|date=July 2009}} | |||

| The ] and health management skills of Graves' disease patients can be seriously impaired. Physicians should be conscious of this while dealing with these patients, as mounting evidence demonstrates the effectiveness of the ] is directly related to health outcomes. The report of a large 2003 summit of physicians and patients notes a number of barriers to achieving desired patient-centered outcomes. It mentions insufficient or unreliable clinical information, lack of communication or inability to communicate effectively, lack of trust between patient and physician, lack of appropriate coordination of care, lack of physician cooperation, and the need to work with too many caregivers, all of which can be very relevant to Graves' disease.<ref name="PatientPhysician-Summit2003"/> | |||

| == |

===No treatment=== | ||

| If left untreated, more serious ] could result, including ]s in pregnancy, increased risk of a ], and in extreme cases, death. Graves-Basedow disease is often accompanied by an increase in heart rate, which may lead to further heart complications including loss of the normal heart rhythm (atrial fibrillation), which may lead to stroke. If the eyes are proptotic (bulging) severely enough that the lids do not close completely at night, severe dryness will occur with a very high risk of a secondary corneal infection which could lead to blindness. Pressure on the optic nerve behind the globe can lead to visual field defects and vision loss as well. | |||

| Recent studies put the incidence of Graves' disease at one to two cases per 1,000 population per year in England. It occurs much more frequently in women than in men. The disease frequently presents itself during early adolescence or begins gradually in adult women, often after ], and is progressive until treatment. It has a powerful ] component.<ref name="ThyroidManager-Ch10-Groot"/> | |||

| ===Symptomatic treatment=== | |||

| Graves' disease tends to be more severe in men, even though it is rarer. It appears less likely to go into permanent remission and the eye disease tends to be more severe, but men are less likely to have large goitres.<ref>{{Cite journal|author=Dayan C |title=Does Graves' disease in men tend to be more severe? |journal=Thyroid Flyyer - Newsletter of Thyroid Australia |volume=3 |date = July 2002|url=http://www.thyroid.org.au/Download/Flyer_2002.3_Men.pdf |format=PDF front cover |accessdate=2010-05-06 |issue=3}}</ref> In a statistical study of symptoms and signs of 184 thyrotoxic patients (52 men, 132 women), the male patients were somewhat older than the females, and cases were more severe among men than among women. ] symptoms were more common in women, even though the men were older and more often had a severe form of the disease; ] and ] were more common and severe in women.<ref name="ThyroidManager-Ch10-Groot"/> | |||

| ] (such as ]) may be used to inhibit the ] symptoms of ] and nausea until such time as antithyroid treatments start to take effect. Pure beta blockers do not inhibit lid-retraction in the eyes, which is mediated by alpha adrenergic receptors. | |||

| ===Treatment of eye disease=== | |||

| ], which is associated with many autoimmune diseases, raises the incidence of ] 7.7-fold.<ref name="pmid20181974">{{Cite journal|author=Bahn RS|title=Graves' ophthalmopathy |journal=N. Engl. J. Med. |volume=362 |issue=8 |pages=726–38|year=2010 |month=February |pmid=20181974 |doi=10.1056/NEJMra0905750 |url=}}</ref> | |||

| Mild cases are treated with lubricant eye drops or non steroidal antiinflammatory drops. Severe cases threatening vision (Corneal exposure or Optic Nerve compression) are treated with steroids or orbital decompression. In all cases cessation of smoking is essential. Double vision can be corrected with prism glasses and surgery (the latter only when the process has been stable for a while). | |||

| Difficulty closing eyes can be treated with lubricant gel at night, or with tape on the eyes to enable full, deep sleep. | |||

| ==History== | |||

| <!-- Deleted image removed: ]]] --> | |||