| Revision as of 22:47, 12 April 2013 view sourceAmanuensis Balkanicus (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users28,237 editsNo edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 20:21, 13 April 2013 view source Правичност (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users1,628 edits when next croatian editors changes this figure to 10,5-11 mil. (because they can count only 10 in infobox). I will again change number of croats to 6.5 mil (because thats how much i can count from their infobox) and then again.. and againNext edit → | ||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

| 3rd row: ], ], ], ], ], ], ]<br /> | 3rd row: ], ], ], ], ], ], ]<br /> | ||

| 4th row: ], ], ], ], ], ], ] | 4th row: ], ], ], ], ], ], ] | ||

| | pop = 10.5<ref name="blic.rs" /> - |

| pop = 10.5<ref name="blic.rs" /> - 12 million{{smallsup|A}} (est.) | ||

| | region1 = {{flag|Serbia}} | | region1 = {{flag|Serbia}} | ||

| | pop1 = 5,988,150 (2011){{smallsup|B}} | | pop1 = 5,988,150 (2011){{smallsup|B}} | ||

Revision as of 20:21, 13 April 2013

Ethnic group

1st row: Jovan Vladimir, Stefan Nemanja, Saint Sava, Dušan the Mighty, Tsar Lazar, Mehmed-paša Sokolović, Zaharije Orfelin 1st row: Jovan Vladimir, Stefan Nemanja, Saint Sava, Dušan the Mighty, Tsar Lazar, Mehmed-paša Sokolović, Zaharije Orfelin2nd row: Dositej Obradović, Karađorđe, Miloš Obrenović, Vuk Karadžić, Njegoš, King Petar I, Nikola Pašić | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 10.5 - 12 million (est.) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 5,988,150 (2011) | |

| 1,439,218 (2013) | |

| 187,739 | |

| 700,000 (2011) | |

| 350,000 (2008) | |

| 178-266,000 (2011) | |

| 186,633 (2011) | |

| 186,000 (2008) | |

| 73-125,000 (2006) | |

| 120,000 (2008) | |

| 80-120,000 (2008) | |

| 53-100,000 (2010) | |

| 70,000 (2005) | |

| 69,544 (2011) | |

| 38,964 (2002) | |

| 35,939 (2002) | |

| 4-30,000 (2008) | |

| 22,518 (2002) | |

| 20,000 (2008) | |

| 15-20,000 (2012) | |

| 5-15,000 (2012) | |

| 7,581 (2008) | |

| 7,210 (2011) | |

| 315,000 (2009) | |

| Languages | |

| Serbian | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly † Eastern Orthodox Christianity (Serbian Orthodox Church) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other South Slavic peoples | |

There are 12 million Serbs worldwide including ancestral diaspora, excluding Kosovo. The 2011 census in Kosovo registered a total of 25,532 Serbs, a boycotted census by the Serbs which failed to enumerate North Kosovo where an estimated 40,000- 50,000 Serbs live.There are 197,984 Serbian citizens in Germany. This figure excludes Serbs who are only citizens of Germany or citizens of other Balkan states and it may include other minor ethnic groups of Serbia. An estimated 700,000 can claim Serbian ethnicity or descent. Over 265,895 declared as maternal Serbian speakers, while over 178,110 declared ethnically as Serbs. An estimated 315,000 can claim Serbian descent. The 1965 census registered over 65,000 Serbian-speakers. | |

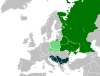

The Serbs (Template:Lang-sr, Template:IPA-sh) are a nation and South Slavic ethnic group living mainly in the Balkans and southern Central Europe. Serbs inhabit Serbia and the disputed territory of Kosovo, as well as Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina (mostly in Republika Srpska) and form significant minorities in Croatia, the Republic of Macedonia and Slovenia. Likewise, Serbs are an officially recognized minority in Romania, Hungary, Albania, the Czech Republic and Slovakia. The Serbian language is also in official use in Greece. There is a large Serbian diaspora (including some autochthonous minorities) in Western Europe, particularly in Germany, Sweden, Switzerland, Austria, France, Italy and the United Kingdom. Outside Europe, there are significant Serbian communities in the United States, Canada and Australia.

The Serbs share cultural traits with the rest of Southeastern Europe, and are predominantly Orthodox Christians by religion. The Serbian language is considered a standardized register of Serbo-Croatian; it is an official language in Serbia (also in the disputed Kosovo) and Bosnia-Herzegovina, and is spoken by a majority in Montenegro. Serbian is the only European language with active digraphia, using both Cyrillic and Latin alphabets.

Anthropology

Ethnonym

There are several theories on the etymology of the ethnonym Serbs. (< *serb-) is the root of the Proto-Slavic word for "same" (as in "same people"), found in Russian and Ukrainian (сербать), Belarussian (сербаць), Slovak (srbati), Bulgarian (сърбам), Old Russian (серебати). Scholars have also suggested an origin in the Indo-European root *ser- 'to watch over, protect', akin to Latin servare 'to keep, guard, protect, preserve, observe'.

Genetics

Main article: Genetic studies on SerbsY-chromosomal haplogroups identified among the Serbs from Serbia and Bosnia-Herzegovina are the following:

- I2a-P37.2, with frequencies of 29.20% and 30.90%, respectively. The frequency of this haplogroup peaks in Herzegovina (64%), and its variance peaks over a large geographic area covering B-H, Serbia, Hungary, Czech Republic, and Slovakia. It is the second most predominant Y-chromosomal haplogroup in the overall Slavic gene pool.

- E1b1b1a2-V13, 20.35% and 19.80%. The frequency of this haplogroup peaks in Albania (24%), and is also high among Greeks, Romanians, Macedonian Slavs, Bulgarians, and southern Italians.

- R1a1-M17, 15.93% and 13.60%. The frequency of this haplogroup peaks in Poland (56.4%) and Ukraine (54.0%), and its variance peaks in northern Bosnia. It is the most predominant Y-chromosomal haplogroup in the overall Slavic gene pool.

- R1b1b2-M269, 10.62 and 6.20%. Its frequency peaks in Western Europe (90% in Wales).

- K*-M9, 7.08% and 7.40%

- J2b-M102, 4.40% and 6.20%

- I1-M253, 5.31% and 2.5%

- F*-M89, 4.9%, only in B-H

- J2a1b1-M92, 2.70%, only in Serbia

There are also several other uncommon haplogroups with lesser frequencies.

Related ethnic groups

The Croats, who are mentioned in De Administrando Imperio as living adjacent to the Serbs, have a distinction of a predominant sphere of influence; Croats are Roman Catholic, and are historically linked with the Holy Roman Empire from the early stage (Western Roman Empire); Italy, Austria and Hungary. A majority of the two ethnic groups have co-existed in the Habsburg Empire and Venetian territories throughout centuries, so links between the two nations have been maintained in that respect through common history.

The Bosniaks, whose ethnonym initially referred to Slavic Christians (Orthodox, Catholic and Bogomils) which co-existed in Bosnia and Herzegovina in the Middle Ages, are today majority Muslim. Many converted or were born into Islam during the 500 years of Ottoman governance.

Although the Serbs and Bulgarians share Slavic kinship, Orthodox Christianity and cultural traits, the two peoples have competed for power in history and were early on understood as distinct ethnic groups. The two are divided in language by the Southeastern versus Southwestern dialectal groups, although a large transitional dialectal area covers Southeastern Serbia, Western Bulgaria and Macedonia.

The dialects of Serbia, Bosnia & Herzegovina, Croatia and Montenegro are virtually the same language (see Serbo-Croatian).

Identity

| This section needs expansion with: (August 2012). You can help by making an edit requestadding to it . (August 2012) |

An international self-esteem survey titled Simultaneous Administration of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale in 53 Nations: Exploring the Universal and Culture-Specific Features of Global Self-Esteem conducted on 16,998 people from 53 nations by researchers from Bradley University David P. Schmitt (PhD), and University of Tartu Jüri Allik, was published by the American Psychological Association in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 2005, Vol. 89, No. 4. The questionnaire included views of one's individual personality, that of one's own nation and that of other nations. The research found that Serbia was placed first of the most self-esteemed nation, ahead of U.S.A. (6th), and Japan (last place), and the majority of nations, as well as Serbs themselves, agreed on this. The research also noted that Serbia was among the 10 most collectivist nations.

History

Further information: History of Serbia and History of the SerbsThe Serbs are a Slavic people, specifically of the South Slavic subgroup, which has its origins in the 6th- and 7th-century communities developed in Southeastern Europe after a major migration (see Great Migration). Slav raids on Eastern Roman territory are mentioned in 518, and by the 580s they had conquered large areas referred to as Sclavinia. In 649, Constantine III relocated conquered Slavs "from the Vardar" to Gordoservon (Serb habitat). Among communities that were part of the Serb ethnogenesis are the Romanized Paleo-Balkan tribes of Illyrians, Thracians and Dacians, Celts, Greek colonies and Romans.

In 822, the Serbs are mentioned as "inhabiting the larger part of Dalmatia" (Serbian lands). The Emperor Constantine VII (r. 913–959) wrote about them in his work De Administrando Imperio about the Serbs, mentioning the White Serbs who "migrated from Βοϊκι" and formed a principality, as well as an early chronological list of Serbian monarchs starting from the 7th century. The Serbs subsequently developed a Byzantine-Slavic culture, like the neighbouring Bulgarians (who derive their ethnonym from the Turkic Bulgars, founders of their state). The establishment of Christianity as state-religion took place around 869 AD, during the rule of Emperor Basil I (r. 867–886). The Serbian Orthodox Church was established in 1219. By the time of the Serbian Empire, the Serbo-Byzantine cultural sphere had besides the initial territories in Central Balkans, much of the Macedonia region and Epirus.

The Battle of Kosovo in 1389 (see Ottoman wars in Europe and Serbian–Ottoman wars) marked the beginning of the fall of the Serbia. There were several migrations of Serbs from their lands in the south towards the "Christian lands" to the north of the Ottoman borders; they crossed the Danube and Sava rivers to Central Europe (today's Vojvodina, Slavonia, Transylvania and Hungary proper). The Great Serbian Migrations refers to the relocation of peoples in two waves in the 17th century of tens of thousands Serbian families. Apart from the Habsburg Empire, thousands were attracted to Imperial Russia (Nova Serbia and Slavo-Serbia).

Serbian refugees and military served in great European armies, and were the progenitors or instrumental in several foreign military structures: Hussars (light cavalry in Hungary and Poland), Seimeni (infantry in Moldavia and Wallachia), Stratioti (light cavalry mercenaries in southern and central Europe, 15th to 18th centuries), Uskoks, etc. They were also part of official ranks, such as the "Serbian Militia", a branch of the Austrian army under Leopold I. During the centuries of Ottoman occupation, the Serbs organized several revolts and guerrilla units, planned both inside and outside the Ottoman borders. The Hajduks, who were brigands and freedom fighters, have represented an important part in Serbian identity. The Serbian Revolution, fought from 1804–1815, resulted in the liberation of Serbia from the Ottomans.

Middle Ages

The Serbs are a people of the South Slavic subgroup, which has its origins in the 6th- and 7th-century communities developed in Southeastern Europe. Slav raids on Eastern Roman territory were mentioned in 518, and by the 580s they had conquered large areas referred to as Sclavinia (transl. Slavdom, from Sklavenoi – Σκλαυηνοι, the early South Slavic tribe which is eponymous to the current ethnic and linguistic Indo-European people). The Slavs invaded the Balkans during the rule of Justinian I (527–565), when eventually up to 100,000 Slavs raided Thessalonica. The Western Balkans was settled with Sclaveni, the east with the Antes. Archaeological evidence in Serbia and Macedonia conclude that the White Serbs may have reached the Balkans earlier, between 550–600, as much findings; fibulae and pottery found at Roman forts, point to Serb characteristics.

-Royal Frankish Annals, 819–822"...Sorabi, quae natio magnam Dalmatiae partem obtinere dicitur..."

transl. "Serbs, who inhabit a large part of Dalmatia"

The Serbs, as Slavs in the vicinity of the Byzantine Empire, lived in so-called Sklavinia ("Slav lands"), territories initially out of Byzantine control and independent. Emperor Constantine VII (r. 913–959) writes in his work "De Administrando Imperio" about the Serbs, mentioning the White Serbs that "migrated from Βοϊκι" and formed a principality, as well as an early chronological list of Serbian monarchs starting from the 7th century. The Serbs subsequently developed a Byzantine-Slavic culture, like the neighbouring Bulgarians (who derive their ethnonym from the Turkic Bulgars, founders of their nation). In the 8 century, the Vlastimirović dynasty established the Serbian Principality. In 822, Serbia stretched over "the greater part of Dalmatia", and Christianity was adopted as state-religion in ca 870. In the mid 10 century the state had emerged into a tribal confederation that stretched to the shores of the Adriatic Sea by the Neretva, the Sava, the Morava, and Skadar. The state disintegrated after the death of the last known Vlastimirid ruler – the Byzantines annexed the region and held it for a century, until 1040 when the Serbs under the Vojislavljević dynasty revolted in Duklja (Pomorje). In 1091, the Vukanović dynasty established the Serbian Grand Principality, based in Rascia (Zagorje). The two halves were reunited in 1142. The Slavs were administered into župe, a confederation of village communities headed by the local župan, a magistrate or governor. The cultural ties with the Byzantine Empire contributed greatly to the Serbian ethnogenesis.

In 1166, Stefan Nemanja assumed the throne of Serbia, marking the beginning of a prospering nation, henceforth under the rule of the Nemanjić dynasty. Nemanja's son Rastko (posth. Saint Sava), gained autocephaly for the Serbian Church in 1217 and authored the oldest known constitution, and in the same year Stefan II was crowned King, establishing the Serbian Kingdom. The Serbian Empire was established in 1346 by Stephen Dušan the Mighty, during which time Serbia reached its territorial peak, becoming one of the most powerful states in Europe and the most powerful in the Balkans. Dušan's Code, a universal system of law, was enacted. The reign of his son Stephen Uroš V the Weak saw the Empire fragment into a confederation of principalities. Emperor Uroš died childless in December 1371, after much of the nobility had been destroyed by the Ottomans in the Battle of Maritsa earlier that year. The Mrnjavčević, Lazarević and Branković dynasties ruled the Serbian lands in the 15th and 16th centuries. Constant struggles took place between various Serbian provinces and the Ottoman Empire. After the fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans in 1453 and the Siege of Belgrade, the Serbian Despotate fell in 1459 following the siege of the provisional capital of Smederevo. After repelling Ottoman attacks for over 70 years, Belgrade finally fell in 1521, opening the way for Ottoman expansion into Central Europe.

Serbia was conquered by the Ottoman Empire after the Battle of Kosovo which was fought in 1389 and the country remained under Ottoman occupation until the early 19th century. The Serbian revolution occurred from 1804–1835. The first part of the period, from 1804 to 1815, was marked by a violent struggle for independence from the Ottoman Empire, with two armed uprisings taking place. The later period (1815–1835) witnessed a peaceful consolidation of political power of the newly autonomous Serbia, culminating in the recognition of the right to hereditary rule by Serbian princes in 1830 and 1833 and the adoption of the first written constitution in 1835. These events marked the foundation of a Modern Serbia.

Ottoman and Habsburg period

After the loss of independence to the Kingdom of Hungary and the Ottoman Empire, Serbia briefly regained sovereignty under Jovan Nenad in the 16th century. Three Austrian invasions and numerous rebellions constantly challenged Ottoman rule. One famous incident was the Banat Uprising in 1595 which was part of the Long War between the Ottomans and the Habsburgs. Vojvodina endured a century long Ottoman occupation before being ceded to the Habsburg Empire in the 18th century under the Treaty of Karlowitz. As the Great Serb Migrations depopulated most of southern Serbia, the Serbs sought refuge across the Danube river in Vojvodina to the north and the Military Frontier in the west where they were granted rights by the Austrian crown under measures such as the Statuta Wallachorum of 1630. Ottoman control over Serbia meant that the once abolished Serbian patriarchate (1459) was reestablished in 1557 – thus providing the continuation of Serbian cultural traditions within the empire. The Patriarchate of Peć was abolished by the Ottomans in 1766 however, and the ecclesiastical center of the Serbs moved to the Metropolitanate of Sremski Karlovci. As Ottoman plunder of Serbian lands intensified, Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I formally granted Serbs who wished to leave the right to their autonomous crownland following several petitions.

Revolution and Independence of Serbia

The quest for national emancipation was first undertaken during the Serbian national revolution, in 1804 until 1815. The national liberation war was followed by a period of formalization, negotiations and finally, the Constitutionalization, effectively ending the process in 1835. For the first time in Ottoman history, the entire Serbian Christian population had risen up against the Sultan. The entrenchment of French troops in western Balkans, the incessant political crises in the Ottoman Empire, the growing intensity of the Austro–Russian rivalry in the Balkans, the intermittent warfare which consumed the energies of French and Russian Empires and the outbreak of protracted hostilities between the Porte and Russia are but a few of the major international developments which directly or indirectly influenced the course of the Serbian revolt.

During the First Serbian Uprising, led by Duke Karađorđe Petrović, Serbia was independent for almost a decade before the Ottoman army was able to reoccupy the country. Shortly after this, the Second Serbian Uprising began. Led by Miloš Obrenović, it ended in 1815 with a compromise between the Serbian revolutionaries and the Ottoman authorities. They were the easternmost bourgeois revolutions in the 19th-century world. Likewise, Serbia was one of the first nations in the Balkans to abolish feudalism. The Convention of Ackerman in 1826, the Treaty of Adrianople in 1829 and finally, the Hatt-i Sharif, recognized the suzerainty of Serbia with Miloš Obrenović I as its hereditary Prince. The struggle for liberty, a more modern society and a nation-state in Serbia won a victory under first constitution in the Balkans on 15 February 1835. It was replaced by a more conservative Constitution in 1838. In the two following decades, temporarily ruled by the House of Karađorđević, the Principality of Serbia actively supported the neighboring Habsburg Serbs, especially during the 1848 revolutions. Interior minister Ilija Garašanin published The Draft which became the standpoint of Serbian foreign policy from the mid-19th century onwards.

Following the clashes between the Ottoman army and civilians in Belgrade in 1862, and under pressure from the Great Powers, by 1867 the last Turkish soldiers left the Principality. By enacting a new constitution without consulting the Porte, Serbian diplomats confirmed the de facto independence of the country. In 1876, Serbia declared war on the Ottoman Empire, proclaiming its unification with Bosnia. The formal independence of the country was internationally recognized at the Congress of Berlin in 1878, which formally ended the Russo-Turkish War; this treaty, however, prohibited Serbia from uniting with Bosnia by placing it under Austro-Hungarian occupation. From 1815 to 1903, Principality of Serbia was ruled by the House of Obrenović, except from 1842 to 1858, when it was led by Prince Aleksandar Karađorđević. In 1882, Serbia became a kingdom, ruled by King Milan. In 1903, Serbian military officers led by Dragutin Dimitrijević stormed the Serbian Royal Palace. After a fierce battle in the dark the attackers captured General Laza Petrović, head of the Palace Guard, and forced him to reveal the hiding place of King Alexander Obrenović and his wife Queen Draga. The King and Queen opened the door from their hiding place. The King was shot thirty times; the Queen eighteen. MacKenzie writes: "The royal corpses were then stripped and brutally sabred." The attackers threw the corpses of King Alexander and Queen Draga out of a palace window, ending any threat that loyalists would mount a counterattack." General Petrović was then killed too (Vojislav Tankosić organized the murders of Queen Draga's brothers; Dimitrijević and Tankosić in 1913–1914 figure prominently in the plot to assassinate Franz Ferdinand). The conspirators installed Peter I of the House of Karađorđević, descendants of the revolutionary leader Karađorđe Petrović, as the new King of Serbia.

Balkan Wars and First World War

See also: Balkan Wars and Serbian Campaign (World War I)Under the 1878 Treaty of Berlin, Austria-Hungary received the mandate to occupy and administer the Ottoman Vilayet of Bosnia while the Ottoman Empire retained official sovereignty.

After the May Overthrow, the new Serbian dynasty became more nationalistic, friendlier to Russia and less friendly to Austria-Hungary. Over the next decade, disputes between Serbia and its neighbors erupted as Serbia moved to build its power and gradually reclaim its 14th-century empire. These conflicts included a customs dispute with Austria-Hungary beginning in 1906 (commonly referred to as the "Pig War"), the Bosnian crisis of 1908–1909 in which Serbia assumed an attitude of protest over Austria-Hungary's annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina (ending in Serbian acquiescence without compensation in March 1909), and finally the two Balkan Wars of 1912–1913 in which Serbia conquered Macedonia and Kosovo from the Ottoman Empire.

In the course of the First Balkan War in 1912, the Balkan League, including Serbia, defeated the Ottoman Empire and conquered its European territories, which enabled territorial expansion into Raška and Kosovo. The Second Balkan War soon ensued when Bulgaria turned against Serbia and Greece, but their armies repulsed the offensive and penetrated into Bulgaria. In the resulting Treaty of Bucharest, Bulgaria lost most of the territories gained in the First Balkan War, with Serbia annexing Vardar Macedonia. Serbia enlarged its territory by 80% and its population by 50% within just two years.

Serbia's military successes and Serbian outrage over the Austro-Hungarian annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina emboldened nationalistic elements in Serbia and Serbs in Austria-Hungary who chafed under Austro-Hungarian rule and whose nationalist sentiments were stirred by Serbian "cultural" organizations.

Winston Churchill, The Great War."The Serbians, seasoned, war-hardened men, inspired by the fiercest patriotism, the result of generations of torment and struggle, awaited undaunted whatever fate might bestow."

On 28 June 1914, Gavrilo Princip, a Bosnian Serb student and member of Young Bosnia, assassinated the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria in Sarajevo, Bosnia. This began a month of diplomatic manoeuvring among Austria-Hungary, Germany, Russia, France, and Britain called the July Crisis. Wanting to finally end Serbian interference in Bosnia, Austria-Hungary delivered the July Ultimatum to Serbia, a series of ten demands intentionally made unacceptable, intending to provoke a war with Serbia. When Serbia agreed to only eight of the ten demands, Austria-Hungary declared war on 28 July 1914. The retaliation by Austria-Hungary against Serbia activated a series of military alliances that set off a chain reaction of war declarations across the continent, leading to the outbreak of World War I within a month. Serbia won the first major battles of World War I, including the Battle of Cer and Battle of Kolubara – marking the first Allied victories against the Central Powers in World War I. Despite initial success, the Serb victory proved to be short-lived. In the early months of 1915, an enormous typhus outbreak started to wreak havoc across the Kingdom, during which some 150,000 people are estimated to have died during the worst typhus epidemic in world history. On 7 October 1915, the Kingdom of Serbia was invaded by a combined Austro-Hungarian and German force. The Bulgarians declared war on 14 October and the Kingdom was eventually overpowered by the joint forces of the German Empire, Austria-Hungary and Bulgaria in 1915. With his forces vastly outnumbered and outgunned, Serb Vojvoda Marshal Radomir Putnik ordered a full retreat of the Serbian military south and west through Montenegro and into Albania on 25 November 1915. The weather was terrible, the roads were poor and the army had to help the tens of thousands of civilians who had retreated alongside the soldiers who had almost no supplies or food left. But the bad weather and poor roads worked for the Serbians as well, as the Germans and Bulgarians could not advance past the treacherous Albanian mountains, and so the thousands of Serbs who were fleeing their homeland managed to evade capture. However, hundreds of thousands of them perished due to hunger, disease, thirst, hypothermia and because of attacks by enemy forces and Albanian tribal bands. The circumstances of the retreat were disastrous, and all told, some 155,000 Serbs, mostly soldiers, reached the coast of the Adriatic Sea, and embarked on Allied transport ships that carried the army to various Greek islands (many to Corfu) before being sent to Salonika. During the retreat, approximately 200,000 Serbs perished in the Albanian mountains and thousands more perished once they arrived on the Greek island of Corfu. Because of the massive loss of life, the Serbian army's retreat through Albania is considered by Serbs to be one of the greatest tragedies in their nation's history.

Despite sustainining enormous casualties, the Serbian army managed to recover, regrouped and returned to the Macedonian front to lead a final breakthrough through enemy lines on 15 September 1918, liberating Serbia and defeating the Austro-Hungarian Empire and Bulgaria. Serbia, with its campaign, was a major Balkan Entente Power which contributed significantly to the Allied victory in the Balkans in November 1918, especially by helping France force Bulgaria's capitulation. Serbia was classified as a minor Entente power. Serbia was also among the main contributors to the capitulation of Austria-Hungary in Central Europe. Serbia's casualties accounted for 8% of the total Entente military deaths; 58% (243,600) soldiers of the Serbian army perished in the war. The total number of casualties is placed around 1,000,000, more than 25% of Serbia's prewar size, and a majority (57%) of its overall male population.

First Yugoslavia and World War II

See also: World War II persecution of Serbs and Yugoslav FrontAt the end of October 1918, the Austro-Hungarian Empire collapsed. On 24 November, the Assembly of Syrmia proclaimed the unification of Syrmia with the Kingdom of Serbia, followed by the Assembly of Vojvodina's decision to unite Banat, Bačka and Baranja with Belgrade a day later, therefore bringing the entire Vojvodina region into the Serb Kingdom. On 26 November 1918, the Podgorica Assembly deposed the House of Petrović-Njegoš of the Kingdom of Montenegro, opting for the House of Karađorđević of Serbia instead, effectively unifying the two states. On 1 December 1918, Serbian Prince Regent Alexander of Serbia proclaimed the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes under King Peter I of Serbia. In November 1920, with the major boundary disputes resolved, a constituent assembly was finally elected and convened and the assembly adopted a constitution in June 1921. The new kingdom was to be a unitary state ruled by a Serbian dynasty and government. Alexander became King after Petar died in August 1921. Not long after, Serb centralists and Croat federalists clashed in the parliament and most governments of the time were fragile and short-lived. Nikola Pašić, leader of the Serb Radical Party and the Prime Minister of Serbia before and during World War I, led or dominated most governments until his death in 1926. In 1921 and 1922, Yugoslavia became a member of the Little Entente. In June 1928, a Montenegrin Radical Party deputy opened fire on the floor of the parliament. He shot and killed two Croat deputies and fatally wounded Stjepan Radić, the leader of the Croatian Peasant Party. Relations between Croats and Serbs further deteriorate after the assassination. Afterwards, King Alexander changed the name of the country to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and changed the internal divisions from the 33 oblasts to nine new banovinas. The effect of Alexander's dictatorship was to further alienate the non-Serbs from the idea of unity. The King was assassinated in Marseille during an official visit to France in 1934 by a Bulgarian fascist named Vlado Chernozemski. Chernozemski was a militant fighting for the cause of the IMRO (Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization), which cooperated greatly with the Croat fascists who called themselves the Ustaše. Alexander was succeeded by his eleven-year-old son Peter II and a regency council headed by his cousin, Prince Paul. Prime Minister Milan Stojadinović showed growing sympathy for fascist forms of government and was dismissed by Prince Paul. The regent then encouraged the new Prime Minister, Dragiša Cvetković, to negotiate a solution to the Croatian problem with Vladko Maček. In August 1939, the Cvetković–Maček Agreement established an autonomous Banate of Croatia, de facto making a two-unit federation out of Yugoslavia.

In 1941, despite domestically unpopular attempts by the government of Yugoslavia to appease the Axis powers, Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy, and other Axis states invaded Yugoslavia. During the invasion, Belgrade was bombed by the German air force (Luftwaffe). The invasion lasted little more than ten days, ending with the unconditional surrender of the Royal Yugoslav Army on 17 April. Besides being hopelessly ill-equipped when compared to the German army (Wehrmacht Heer), the Yugoslav army attempted to defend all borders but only managed to thinly spread the limited resources available. Also, large numbers of the population refused to fight, instead welcoming the Germans as liberators from supposed government oppression. Serbia was occupied by the Nazis and the Fascist puppet state of the Independent State of Croatia was established. 360,000 Serbs and 35,000 Jews were murdered by the Croatian Ustaše in a campaign of genocidal persecution during the Second World War. In addition, an estimated 120,000 Serbs were deported from the Independent State of Croatia into the area governed by the Military Administration in Serbia, while an estimated 300,000 fled in 1943. In Kosovo, between 70,000 and 100,000 Serbs were sent to concentration camps in an effort to Albanize the area. Serbs fought in both the resistance movements of the royalist Chetnik movement and the communist Yugoslav Partisan movement. The Chetniks, who increasingly collaborated with the Germans and Italians throughout the war, carried out massacres against the Croat and Muslim population of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Sandžak. The Yugoslav Partisans established a multi-ethnic army that managed to seize control of Yugoslavia and create the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. In the entirety of the war the Partisans in Bosnia were 64.1% Serb, from 1941 to 1945 the Partisans in Croatia were 28% Serb. It is estimated that a total of between 487,000 and 530,000 Serbs were killed in the war.

Communist Yugoslavia

With the Communists emerging victorious at the end of the Second World War, many Serbs fled Yugoslavia fearing persecution at the hands of Tito's authorities. It is estimated that between 70,000–80,000 people were killed in Serbia during the communist takeover.

The new Communist government abolished the Serbian monarchy. A single-party state was soon established in Yugoslavia by the League of Communists of Yugoslavia. All opposition was repressed and people deemed to be promoting opposition to socialism or promoting separatism were imprisoned or executed for sedition. Serbia became a constituent republic within the SFRY known as the Socialist Republic of Serbia and had a republic-branch of the federal communist party, the League of Communists of Serbia. Serbia's most powerful and influential politician in Tito-era Yugoslavia was Aleksandar Ranković, one of the "big four" Yugoslav leaders, alongside Josip Broz Tito, Edvard Kardelj, and Milovan Đilas. In 1950, Ranković as minister of interior reported that since 1945 the Yugoslav communist regime had arrested five million people. Ranković was later removed from the office because of the disagreements regarding Kosovo’s nomenklatura and the interests of Serb unity. Ranković's dismissal was highly unpopular amongst Serbs. Pro-decentralization reformers in Yugoslavia succeeded in the late 1960s in attaining substantial decentralization of powers, creating substantial autonomy in Kosovo and Vojvodina, and recognizing a Yugoslav Muslim nationality. As a result of these reforms, there was a massive overhaul of Kosovo's police, that shifted from being Serb-dominated to ethnic Albanian-dominated through firings of Serbs in large scale. Further concessions were made to the ethnic Albanians of Kosovo in response to unrest, including the creation of the University of Pristina as an Albanian language institution. These changes created widespread fear amongst Serbs of being treated as second-class citizens.

Dissolution of Yugoslavia

In 1989 Slobodan Milošević rose to power in Serbia. Milošević promised reduction of powers for the autonomous provinces of Kosovo and Vojvodina, where his allies subsequently seized power during the anti-bureaucratic revolution. This ignited tensions with the communist leadership of the other republics, and awoke nationalism across the country, that eventually resulted in the Breakup of Yugoslavia, with Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Macedonia declaring independence. Serbia and Montenegro remained together as the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (FRY).

Fueled by ethnic tensions, the Yugoslav Wars erupted, with the most severe conflicts taking place in Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina, where ethnic Serb populations opposed independence from Yugoslavia. The FRY remained outside of the conflicts, but provided logistic, military and financial support to Serb forces in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina. In response, the UN imposed sanctions against the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia in May 1992, which led to political isolation, economic decline and hyperinflation of the Yugoslav dinar.

The Bosnian War ended with the signing of the Dayton Agreement on 14 December 1995, with the formation of the Republika Srpska as a semi-independent Bosnian Serb entity within Bosnia and Herzegovina being the resolution for Bosnian Serb demands. The war in Croatia ended with a total Croatian victory with the Croats routing the forces of the Republic of Serbian Krajina and expelling an estimated 200,000 Croatian Serbs from the country in the largest military offensive in Europe since the end of the Second World War.

Multiparty democracy was introduced in Serbia in 1990, officially dismantling the single-party system. Critics of Milošević claimed that the government continued to be authoritarian despite constitutional changes, as Milošević maintained strong political influence over the state media. Milošević issued media blackouts of independent media stations' coverage of protests against his government and restricted freedom of speech through reforms to the Serbian Penal Code which issued criminal sentences on anyone who "ridiculed" the government and its leaders, resulting in many people being arrested who opposed Milošević and his government.

When the ruling SPS refused to accept its defeat in municipal elections in 1996, Serbians engaged in large protests against the government. Between 1998 and 1999, peace was broken again, when the situation in Kosovo worsened with continued clashes between Yugoslav security forces and the KLA. The confrontations led to the Kosovo War. In the aftermath of the conflict, as many as 170,000 Serbs fled Kosovo to escape harassment, intimidation, beatings and murder at the hands of Kosovo Albanians.

In September 2000, opposition parties accused Milošević of electoral fraud. A campaign of civil resistance followed, led by the Democratic Opposition of Serbia, a broad coalition of anti-Milošević parties. This culminated on 5 October when half a million people from all over the country congregated in Belgrade, compelling Milošević to concede defeat. The fall of Milošević ended Yugoslavia's international isolation. Milošević was subsequently sent to the ICTY and was indicted on charges of crimes against humanity in Kosovo, charges of violating the laws or customs of war, grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions in Croatia and Bosnia and for complicity in genocide in Bosnia. However, he died of a heart attack in 2006 before a verdict could be reached.

Language

Main article: Serbian language

Serbs speak the Serbian language, a member of the South Slavic group of languages, specifically in the Southwestern Slavic group, with the Southeastern group containing Bulgarian and Macedonian. It is considered a standardized register of Serbo-Croatian, as mutually intelligible with the standard Croatian and Bosnian languages (see Differences in standard Serbian, Croatian and Bosnian) which are all standardized on the Shtokavian dialect.

Serbian is an official language in Serbia, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Montenegro, and is a minority language in Croatia, Macedonia, Hungary, Romania and Slovakia.

Older forms of Serbian are Old Serbian, the redaction of Old Church Slavonic, and the Russo-Serbian variant, a version of the Church Slavonic language.

Serbian is the only European language with active digraphia, using both Cyrillic and Latin alphabets. Serbian Cyrillic was devised in 1814 by Serbian linguist Vuk Karadžić, who created the alphabet on phonemic principles, the Cyrillic itself has its origins in Cyril and Methodius' transformation of the Greek script in the 9th century.

Loanwords in the Serbian language besides common internationalisms are mostly from Turkish, German and Italian, words of Hungarian origin are present mostly in the north and Greek words are predominant in the liturgy.

Two Serbian words that are used in many of the world's languages are "vampire" and "paprika". The English term vampire was derived (possibly via French vampyre) from the German Vampir, which was in turn derived in the early 18th century from the Serbian language word вампир/vampir, when Arnold Paole, a purported vampire in Serbia was described as wreaking havoc in Serbian villages during the time that Serbia was incorporated into the Austrian Empire. Common words of Serbian cuisine are "Slivovitz" and "ćevapčići". Paprika and Slivovitz are borrowed via German; paprika itself entered German via Hungarian.

Religion

Main article: Serbian Orthodox Church

Serbs are predominantly Orthodox Christian, and before Christianity, they adhered to Slavic paganism. The identity of ethnic Serbs was historically largely based on Orthodox Christianity and on the Serbian Orthodox Church, to the extent of the claims that those who are not its faithful are not Serbs. However, the conversion of the south Slavs from paganism to Christianity took place before the Great Schism, the split between the Greek East and the Catholic West. After the Schism, those who lived under the Orthodox sphere of influence became Orthodox and those who lived under the Catholic sphere of influence became Catholic. Some ethnologists consider that the distinct Serb and Croat identities relate to religion rather than ethnicity. With the arrival of the Ottoman Empire, some Serbs and Croats converted to Islam. This was particularly, but not wholly, so in Bosnia. The best known Muslim Serb is probably either Mehmed Paša Sokolović or Meša Selimović. Since the second half of the 19th century, some Serbs converted to Protestantism, while historically some Serbs also were Catholics (especially in Dalmatia) or Greek Catholics. In 1219, the Serbian Orthodox Church was established as the national church by Saint Sava. With the occupation of the Balkans by the Ottoman Empire, Islam was introduced, therefore there exist "Muslim Slavs"; Gorani, Bosniaks, Muslims by nationality etc., where Serbs traditionally live. Up until the 20th century, there were some political movements of Serb Catholics in Dubrovnik, Muslim Serbs, as well as Protestants in Vojvodina.

Geographically, the Serbian Orthodox Church represents the westernmost bastion of Orthodox Christianity in Europe, which shaped its historical fate through contacts with Catholicism and Islam.

Culture

Art

There were many famous royal cities and palaces in Serbia at the time of Roman Empire and early Byzantine Empire, traces of which can still be found in Sirmium, Gamzigrad and Justiniana Prima. Serbian medieval monuments, which have survived until today, are mostly monasteries and churches. Most of these monuments have walls painted with frescoes. The most original monument of Serbian medieval art is the Studenica Monastery (built around 1190). This monastery was a model for later monasteries, like: the Mileševa, Sopoćani and Visoki Dečani monasteries. The most famous Serbian medieval fresco is the "Mironosnice na Grobu" (or the "white angel") from the Mileševa monastery.

Icon-painting is also part of Serbian medieval cultural heritage. The influence of Byzantine Art increased after the fall of Constantinople into the hands of the crusaders in the year 1204, when many Byzantine artists fled to Serbia. Their influence is seen in the building of the church Our Lady of Ljeviš and many other buildings, including the Gračanica Monastery. The monastery Visoki Dečani was built between the years 1330 and 1350. Unlike other Serbian monasteries, this one was built in the Romantic style, under the authority of grand master Vita from Kotor. On the frescoes of this monastery, there are some 1,000 portraits depicting the most important episodes from the New Testament.

During the time of Turkish occupation, Serbian art was virtually non-existent, with the exception of several Serbian artists who lived in the lands ruled by the Habsburg Monarchy. Traditional Serbian art showed some Baroque influences at the end of the 18th century as shown in the works of Nikola Nešković, Teodor Kračun, Zaharije Orfelin and Jakov Orfelin. Serbian painting showed the influence of Biedermeier, Neoclassicism, Romanticism and Realism during the 19th century. Some of the most prominent Serbian artists made their works at that time. Anastas Jovanović was a pioneering photographer in Serbia taking photographs of many leading Serbian citizens. Some of the most important Serbian painters of the 20th century were Paja Jovanović, Milan Konjović, Marko Čelebonović, Petar Lubarda, Uroš Predić, Milo Milunović, Vladimir Veličković, Mića Popović, Sava Šumanović and Milena Pavlović-Barili.

Science

Many Serbs have contributed to the field of science and technology. Scientist, inventor and electrical engineer Nikola Tesla patented numerous inventions and was an important contributor to the birth of commercial electricity in the United States. Other notable Serbian scientists and inventors were Mihajlo Pupin and Milutin Milanković.

- Nikola Tesla was famous for developing the AC motor, the bifilar coil, various devices that used rotating magnetic fields, the alternating current polyphase power distribution systems, the fundamental devices of systems of wireless communication (legal priority for the invention of radio), radio frequency oscillators, devices for voltage magnification by standing waves, robotics, logic gates for secure radio frequency communications, devices for x-rays, apparatus for ozone generation, devices for ionized gases, devices for high field emission, devices for charged particle beams, methods for providing extremely low level of resistance to the passage of electrical current, means for increasing the intensity of electrical oscillations, voltage multiplication circuitry, devices for high voltage discharges, devices for lightning protection and VTOL aircraft. He also invented the Tesla coil and the Tesla turbine . The tesla is the SI derived unit of magnetic flux density and was named after Tesla.

- Mihailo Petrović is known for having contributed significantly to differential equations and phenomenology, as well as inventing one of the first prototypes of an analog computer.

- Milutin Milanković is known for his theory of ice ages, suggesting a relationship between the Earth's long-term climate changes and periodic changes in its orbit, now known as Milankovitch cycles.

- Mihajlo Pupin discovered a means of means of greatly extending the range of long-distance telephone communication by placing loading coils of wire (known as Pupin coils) at predetermined intervals along the transmitting wire (known as "pupinization").

- Miodrag Radulovački is best known for postulating the Adenosine Sleep Theory in 1984.

- Josif Pančić discovered and identified the Serbian Spruce in 1875.

- Jovan Cvijić is considered the founder of geography in Serbia. In more than 30 years of intense scientific study, Cvijić published vast number of significant works, many of which have not lost value even today. He founded the Faculty of Philosophy's Geographical institute in 1923, the first geographic institute in Balkans.

Music

Composer and musicologist Stevan Stojanović Mokranjac is considered one of the most important founders of modern Serbian music.

The composer of the Croatian national anthem Lijepa naša domovino (Our Beautiful Homeland) was Croatian Serb Josip Runjanin.

In the 1990s and the 2000s, many pop music performers rose to fame. Željko Joksimović won second place at the 2004 Eurovision Song Contest and Marija Šerifović managed to win the 2007 Eurovision Song Contest with the song "Molitva", and Serbia was the host of the 2008 edition of the Contest.

Balkan Brass, or "truba" (trumpet) is a popular genre that originated during the First Serbian Uprising (1804–1813) with military marching bands that transposed Serbian folk music. Guča trumpet festival is one of the most popular and biggest music festivals in Serbia, with over 300,000 visitors annually.

Cinema

The first Serbian film ever made was The Life and Deeds of the Immortal Vožd Karađorđe by film pioneer Ilija Stanojević. The film was shot in 1911 and was the first one filmed in the Balkans.

The most famous contemporary Serbian filmmaker is Emir Kusturica. He has been recognized for several internationally acclaimed feature films and is a two-time winner of the Palme d'Or at Cannes (for When Father Was Away on Business and Underground.)

Other well-known contemporary Serb filmmakers are Srđan Dragojević and Zdravko Šotra.

Several Serbs have featured prominently in Hollywood— most notably Karl Malden and Milla Jovovich, both of whom are of paternal Serbian ancestry. Serb actors Rade Šerbedžija, Stana Katic and Bojana Novaković have also had important roles in several Hollywood films. Screenwriter Steve Tesich was a Serbian-American who won the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay in 1979 for the movie Breaking Away.

The 1972 Yugoslav Partisan film Valter brani Sarajevo (Walter Defends Sarajevo) starring Serbian actor Bata Živojinović is one of the most-watched war films of all time, owing mainly to audiences in the People's Republic of China.

Symbols

Main article: National symbols of Serbia Further information: List of Serbian flags and Serb heraldry- The red-blue-white tricolour (a Slavic tricolour), is used as the Civil Flag of Serbia, as well as the ethnic or national flag of the Serb people. The official state flag has the tricolour with the Coat of Arms; the Serb eagle, which in turn has the Serb cross in the shield.

- The Serb eagle, a white two-headed eagle, which represents dual power and sovereignty (monarch and church), was the coat of arms of the Nemanjić dynasty, adopted by the succeeding noble and royal families.

- The Serbian cross is a Greek cross with four firesteels. It is based on the Byzantine cross with four Greek letters beta (Β), the first letters of the Greek phrase meaning "King of Kings, ruling over Kings". In the Serbian cross, the four betas have been turned into four Cyrillic letters С with little stylistic modification, for a new message: Само Слога Србина Спашава "Only Unity Saves the Serbs".

Both the eagle and the cross, besides being the basis for various Serbian coats of arms throughout history, are bases for the symbols of various Serbian organizations, political parties, institutions and companies.

Serb folk attire varies, mostly because of the very diverse geography and climate of the territory inhabited by the Serbs. Some parts of it are, however, common:

- The traditional hat Šajkača. It is easily recognizable by its top part that looks like the letter V or like the bottom of a boat (viewed from above), after which it got its name. It originated as military headgear in the 18th-century Serbian river flotilla. It gained wide popularity in the early 20th century as it was used by the Serbian Army in World War I. It is worn on everyday basis by some villagers even today, and it was a common item of headgear among Bosnian Serb military commanders during the Bosnian War in the 1990s. The "šajkača" is traditionally used in the region of Šumadija (central part of Serbia), while Serbs in other regions naturally have other traditional types of hats.

- The traditional shoes Opanci (sing. Opanak), are recognizable by the distinctive tips that spiral backward. The Opanci are part of the wider folk clothing of the Balkans.

Cuisine

Main article: Serbian cuisine

The Serbian cuisine, just like Serbian culture, implies not only regional elements connected to Serbia, but other parts of former Yugoslavia as well. Great influences have been marked on the whole cooking process due to peasantry, which also influenced the folk craft, music and arts.

Traditional dishes made in Serbia today have common roots with the dishes prepared throughout the Balkans. The whole Serbian cuisine is derived from a mixture of influences coming from the Mediterranean (Greek and Italian), Central European (Hungarian and Austrian) and Turkish cuisines.

Serbs have great passion for food in general, especially barbecue, having a rich cuisine and a large diversity of alcohol beverages that accompany these fat-rich dishes. Slivovitz, the national drink, is a strong, alcoholic beverage primarily made from distilled fermented plum juice, tasting similar to brandy (plum brandy in English). Foods include a variety of grilled meats and bread. Desserts range from Turkish-style baklava to Viennese-style tortes. Local Serbian wine is highly regarded and popular in respective wine regions. Among most popular dishes are: Pljeskavica, Ćevapčići, Ajvar, Burek, Gibanica, Karađorđeva šnicla, Musaka, Sarma, Kajmak.

Traditions

Main article: Serbian traditionsThe traditional dance of Serbs is the kolo (in some regions oro), circle dance, of which dances are the same and similar to those of other Balkan peoples. It is a collective dance, where a group of people hold each other by the hands, forming a circle (kolo, hence the name), semicircle or spiral.

The Serbs are a highly family-oriented society. A peek into a Serbian dictionary and the richness of their terminology related to kinship speaks volumes.

As with many other peoples, there are popular stereotypes on the local level: in popular jokes and stories, inhabitants of Vojvodina (Lale) are perceived as phlegmatic, undisturbed and slow; Montenegrins are lazy and pushy; southern Serbians are misers; Bosnians are raw and stupid; people from Central Serbia are often portrayed as capricious and malicious, etc.

Another related feature, often lamented by Serbs themselves, is disunity and discord; as Slobodan Naumović puts it, "Disunity and discord have acquired in the Serbian popular imaginary a notorious, quasi-demiurgic status. They are often perceived as being the chief malefactors in Serbian history, causing political or military defeats, and threatening to tear Serbian society completely apart." That disunity is often quoted as the source of Serbian historic tragedies, from the Battle of Kosovo in 1389 to Yugoslav wars in 1990s. Even the contemporary notion of "two Serbia's"—one supposedly national, liberal and Eurocentric, and the other conservative, nationalist and Euroskeptic—seems to be the extension of the said discord. Popular proverbs "two Serbs, three political parties" and "God save us from Serbs that may unite!", and even the unofficial Serbian motto "only unity saves Serbs" (Samo sloga Srbina spasava) illustrate the national frustration with the inability to unite over important issues.

Christian customs

Of all Slavs and Orthodox Christians, only Serbs have the custom of slava. Slava is the celebration of a family's patron saint, a protector, which is inherited mostly, though not exclusively, paternally. The custom is believed to have its origin in pagan times, and is known to have been canonically introduced by Saint Sava, the first Serbian Archbishop (1217–1233). There are a total of 78 feast days, and each family has one patron saint only, which means that the occasion brings all of the family together.

Serbs have their own customs regarding Christmas. The Serbian Orthodox Church uses the Julian calendar, so Christmas currently falls on 7 January of the Gregorian calendar. Early in the morning of Christmas Eve, the head of the family would go to a forest in order to cut badnjak, a young oak, which is then brought into the church to be blessed by the priest. The tree is stripped of its branches and combined with wheat and other grain products to be burned in the fireplace. The burning of the badnjak is a ritual which is most certainly of pagan origin, and is considered a sacrifice to God so that the coming year may bring plenty of food, happiness, love, luck and riches. Nowadays, with most Serbs living in towns, most simply go to their church service to be given a small parcel of oak, wheat and other branches tied together to be taken home and set afire. The house floor and church is covered with hay, reminding worshippers of the stable in which Jesus was born.

Christmas Day itself is celebrated with a feast, necessarily featuring roasted piglet as the main meal. The most important Christmas meal is česnica, a special kind of bread. The bread contains a coin; during the lunch, the family breaks up the bread and the one who finds the coin is said to be assured of an especially happy year.

Christmas is not associated with presents like in the West, most Serbian families give presents on New Year's Day. Deda Mraz (literally Grandpa Frost, the Santa Claus) and the Christmas tree (but rather associated with New Year's Day) are also used in Serbia as a result of globalisation. Serbs also celebrate the Old New Year (currently on 14 January of the Gregorian Calendar).

Naming culture

A child is given a first name chosen by their parents but approved by the godparents of the child (the godparents rarely object to the parents' choice). The given name comes first, the surname last, e.g. "Dragan Marković". Female names end with -a, e.g. Dragan -> Dragana, though several male names exist that end with -a (e.g. Andrija, Vanja, etc.)

Popular names are mostly of Serbian (Slavic), Christian (Biblical), Greek and Latin origin.

- Serbian: Nenad, Dragan, Zoran, Goran, Dušan, Nemanja, Vojislav, Miloš, Veljko and Slobodan.

- Greek: Nikola, Stefan, Đorđe, Aleksandar, Filip and Dimitrije.

- Biblical: Jovan, Danilo, Petar, Pavle, Mihailo, Marija and Ana.

- Latin: Marko, Srđan and Antonije.

Most Serbian surnames (like Bosniak, Croatian and Montenegrin) have the surname suffix -ić (pronounced Template:IPA-sh, Cyrillic: -ић). This is often transliterated as -ic. In English-speaking countries before the 20th century, Serbian names were often transcribed with a phonetic ending, -ich or -itch (Milutin Milanković -> Milutin Milankovitch). The -ić suffix is a Slavic diminutive, originally functioning to create patronymics. Thus the surname Petrić signifies little Petar, similar to Mac ("son of") in Scottish & Irish, and O' (grandson of) in Irish names. It is estimated that some two thirds of all Serbian surnames end in -ić and some 80% of Serbs carry such a surname. Other common surname suffixes are -ov or -in which is the Slavic possessive case suffix, thus Nikola's son becomes Nikolin, Petar's son Petrov, and Jovan's son Jovanov. Those are more typical for Serbs from Vojvodina. The two suffixes are often combined. The most common surnames are Marković, Nikolić, Petrović, Jovanović, Popović, etc.

Sport

The most popular sports among Serbs are football, basketball, volleyball, handball, water polo and tennis.

The two most popular football clubs in Serbia are Red Star Belgrade and Partizan Belgrade, both from the capital city Belgrade. Red Star is the only Serbian and former Yugoslav club that has won a UEFA competition, winning the 1991 European Cup in Bari, Italy. The same year in Tokyo, Japan, the club won the Intercontinental Cup. Partizan is the first Eastern European football club which played in a European Cup final (in 1966). The matches between the two rival clubs are known as the "Eternal Derby". Serbia's national football team made their first appearance during the qualifying rounds for Euro 2008 although they did not qualify for the competition. During the qualifying tournament for the 2010 FIFA World Cup, Serbia came first in its group, ahead of France and consequently qualified directly for the championship.

Serbia is one of the traditional powerhouses of world basketball, winning various FIBA World Championships, multiple EuroBaskets and Olympic medals (albeit as FR Yugoslavia). Serbia's national basketball team is the successor to the successful Yugoslavia national basketball team. Serbia has won FIBA world championships five times and won second place in the 2009 European championship. Serbian basketball players have made a deep impact in history of basketball, having success both in the top leagues of Europe and in the NBA. Serbs that have played in the NBA include: Vlade Divac (FIBA Hall of Fame), Predrag Stojaković, Željko Rebrača, Marko Jarić, Nenad Krstić, Darko Miličić, Vladimir Radmanović, and Serbian American Pete Maravich.

Serbian tennis players Novak Đoković, Ana Ivanović, Jelena Janković, Nenad Zimonjić, Janko Tipsarević and Viktor Troicki are very successful and their success has led to a popularisation of tennis in Serbia. Đoković, in particular, is very popular and is currently the World No. 1 men's tennis player in the ATP rankings, and a five-time Grand Slam champion. Ivanović, also known for her popularity worldwide, is a former World No. 1 and, like Djokovic, has experienced Grand Slam success, winning the French Open in 2008. Djokovic was also the founder of the first ATP tennis tournament in the country, the Serbia Open. Other well-known Serb tennis players are Andrea Petkovic, Jelena Dokić and Slobodan Živojinović. The Serbia men national team won the 2010 Davis Cup.

Communities

In Serbia (the nation-state), 6.2 million Serbs constitute about 62% of the population (83% excluding Kosovo, see Status of Kosovo). Another 1,6 million live in Bosnia and Herzegovina, where they are a constituent nation, predominantly living in Republika Srpska. In Montenegro (former nation-state), the minority numbers 201,892. The minority in Croatia numbers some 200,000 people (580,000 prior to the war, when they were a constituent nation). In the 1991 census Serbs consisted 39% of the overall population of former Yugoslavia; there were around 8.5 million Serbs in the entire country. Much smaller Serb autochthonous minorities exist in the Republic of Macedonia (mainly in Kumanovo and Skopje), Slovenia (Bela Krajina), Romania (Banat), Hungary (Szentendre, Pécs, Szeged) and Italy (Trieste – home to about 6,000 Serbs).

According to the 2002 census there were 1,417,187 ethnic Serbs are in the municipality of Belgrade, 191,405 in the city of Novi Sad, 162,380 in the city of Niš, 170,147 in the municipality of Kragujevac and 106,826 in the municipality of Banja Luka (in Bosnia and Herzegovina as of 1991 census). All the capitals of the former Yugoslavia contain a strong historical Serbian minority – 10,000 strong and over (taking up anywhere between 2%- 3% of the population – Zagreb, Skopje – through Ljubljana and Sarajevo, and finally, Podgorica – over 26%).

The subgroups of Serbs are commonly based on regional affiliation. Some of the major regional groups include: Šumadinci, Ere, Vojvođani, Crnogorci, Kosovci, Bačvani, Banaćani, Bokelji, Bosanci, Sremci, Semberci, Krajišnici, Hercegovci, Šopi, etc. (The demonyms are also used to refer to any native inhabitant, regardless of ethnicity, i.e. Vojvodinian Hungarians or Croat Herzegovinians). Serbs inhabiting Montenegro and Herzegovina are organized into clans.

Many Serbs also live in the diaspora, notably in Germany, Austria, the Netherlands, Switzerland, France, Sweden, Canada, the US and Australia. Abroad, Vienna is said to be home to the largest Serb population followed by Chicago (and its surrounding area) with Toronto and southern Ontario coming in third. Los Angeles and Indianapolis are known to have a sizable Serbian community, but so do Berlin, Paris, Moscow, Istanbul and Sydney. The number of Serbs in the diaspora is unknown but it is estimated to be up to 5.5 million. Smaller numbers of Serbs live in New Zealand, and Serbian communities in South America (Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil and Chile) are reported to grow and exist to this day.

According to official figures, 5000 Serbs live in Dubai but the unofficial figure is estimated to be around 15,000. Serbian immigrants went to the Persian Gulf states to find employment opportunities in the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Qatar and Kuwait in the 1990s and 2000s.

A recent research of the Ministry of Diaspora showed that more than two thirds of Serbs abroad have plans of returning to Serbia, and almost one third is ready to return immediately should they be given a good employment offer. The same research shows that more than 25% of the diaspora has some specialization, i.e. master or PhD titles, while 45% have university degrees.

Autochthonous communities and minorities

- Autochthonous communities

- Serbia is the nation-state of the Serbs.

- In Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbs are one of the three constitutive ethnic groups, the entity of Republika Srpska is home to the supermajority of Bosnian Serbs.

- In Montenegro, 32% of the population is Serb according to the 2003 census, they are a national minority, however in the 19th century Montenegro was a nation-state of the Serbs and they were the majority (~90%) until World War II.

- Autochthonous communities with minority status

- In Croatia, Serbs are the largest national minority, scattered across the country. According to the 2001 Census, there were 201,631 Serbs in Croatia, down from the pre-war figure of 581,663, a result of the Operation Oluja; the Croatian War. They were stripped of their constitutional status in 1990.

- In Macedonia, Serbs are a minority present in 16 municipalities, the largest being the Čučer-Sandevo Municipality (close to 28%) and Staro Nagoričane Municipality. They are found in the cities of Kumanovo and Skopje.

- Serbian minorities exist in the following regions

- In Hungary, Serbs are an officially recognized ethnic minority, numbering 7,350 people or 0.1% of population. They are scattered in the southern part of the country. There are also some Serbs who live in the central part of the country – in bigger towns like Budapest, Szentendre, etc. The only settlement with an ethnic Serb majority in Hungary is Lórév on Csepel Island.

- In Romania, Serbs are located mostly within the Caraş-Severin County, where they constitute absolute majority in the commune of Pojejena (52.09%) and a plurality in the commune of Socol (49.54%) Serbs also constitute an absolute majority in the municipality of Sviniţa (87.27%) in the Mehedinţi County. The region where these three municipalities are located is known as Clisura Dunării in Romanian or Banatska Klisura (Банатска Клисура) in Serbian. Officially recognized minority in Romania numbers 22,518 or 0.1% of the population (Census 2002).

- In Albania, Serbs are not officially recognized as a minority. According to the latest national minority census in Albania (2000), there were around 2000 Serbs and Montenegrins (they are listed together as one ethnic group) in the country. Domestic Serb-Montenegrin community claims the figure is around 25,000, while independent sources placed the figure at 10,000 in 1994. Serbian sources estimate up to 30,000.

- Serbian community in Italy's city of Trieste dates back to the 18th century. Local Serbs have erected one of the most prominent monuments in central Trieste: the Serbian Orthodox Church of Saint Spyridon (1854).

- There is a small number of Serbs in Slovakia, mostly located in the southern town of Komárno, where they have been living since the 17th century. There has also been a historic minority in Bratislava (Požun), where many Habsburg Serbs studied in the university. Their present number today is unknown but they are nevertheless recognized as an official minority.

Diaspora

Main article: Serbian diaspora

There are currently between 3 and 4 million Serbs in diaspora throughout the world. The Serb diaspora was the consequence of either voluntary departure, coercion and/or forced migrations or expulsions:

- To the west and north, caused mostly by the Ottoman Turks.

- To the east (Czechoslovakia, Russia, Ukraine and across the former USSR from World War I and World War II, to until the fall of Communism in Eastern Europe by the early 1990s).

- To the USA for economic reasons, but Serbians also migrated to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and South America.

- During wartime, particularly World War II and post-war political migration, predominantly into overseas countries (large waves of Serbians and other Yugoslavians into the USA, Great Britain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand).

- Going abroad for temporary work as "guest workers" and "resident aliens" who stayed in their new homelands during the turbulent 1960s and 1970s (to Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom), however some Serbians returned to Yugoslavia in the 1980s.

- Escaping from the uncertain situation (1991–1995) caused by the dissolution of Yugoslavia, the renewal of vicious ethnic conflicts and civil war, as well as by the disastrous economic crises, which largely affected the educated or skilled labor forces (i.e. "brain drain"), increasingly migrated to Western Europe, North America and Australia/New Zealand.

The existence of the centuries-old Serb or Serbian diaspora in countries such as Austria, Czech Republic, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Romania, Russia, Poland, Slovakia, Turkey and Ukraine, is the result of historical circumstances – the migrations to the North and the East, due to the Turkish conquests of the Balkans and as a result of politics, especially when the Communist Party came into power, but even more when the communist state of Yugoslavia collapsed into inter-ethnic conflict, resulting in mass expulsions of people as refugees of war. Although some members of the Serbian diaspora do not speak the Serbian language nor observe Christianity (some Serbian citizens are Jews, Muslims, Protestants, Roman Catholics, Eastern Rite Catholics, or atheists).

Maps

See also

- Serbia, nation-state of Serbs

- List of notable Serbs

- states, regions, territories of Serbs

- Serb clans, former feudal organizations of Montenegro and Herzegovina

- Yugoslavs, national demonym and umbrella term of the peoples of the Yugoslav federation

- Slavs; Medieval Slav tribes; South Slavs

Footnotes

- ^ "Četiri miliona Srba našlo uhlebljenje u inostranstvu". Blic. 17 July 2011. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- The Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia

- "CIA - The World Factbook - Bosnia and Herzegovina".CIA doesn't give information about the precise number of Serbs, it is declared that the Serbs were 37.1% in 2000 and is suggested that the total population would be 3,875,723 but July, 2013; an improvised calculation of 37.1% of 3,875,723 would result in 1,439,218 Serbs.

- "Total ancestry categories tallied for people with one or more ancestry categories reported 2010 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- BBCSerbian.com | News | Srpska zajednica u Americi

- Serben in Deutschland | Serben in Deutschland | Zentralrat der Serben in Deutschland

- Serben-Demo eskaliert in Wien

- "Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in Montenegro 2011" (PDF). 12 July 2011. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- "2011 Census". Dzs.hr. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- "Erstmals über eine Million EU- und EFTA Angehörige in der Schweiz". Neue Zürcher Zeitung. 14. Oktober 2008.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Serbs - The Canadian Encyclopedia

- Arrival, Settlement, and Economic Life | Multicultural Canada

- Nordstrom, p. 353. (Serbia and Iran as top two countries in terms of immigration beside "Other Nordic Countries," based on Nordic Council of Ministers Yearbook of Nordic Statistics, 1996, 46-47)

- Présentation de la République de Serbie

- Statistiche demografiche ISTAT

- La Serbia guarda all'Italia

- The Serbian Council of Great Britain

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (2011)

- "The Euromosaic study - Other languages in Slovenia". European Commission.

- Државен завод за статистика: Попис на населението, домаќинствата и становите во Република Македонија, 2002: Дефинитивни податоци (PDF)

- Life of Serbs in Albania, 2008-10-03

- Agenţia Naţionala pentru Intreprinderi Mici si Mijlocii: Recensamânt România 2002

- "Etrangers inscrits dans tous les registres (1,2,3,4 et 5) du registre national - Remarque : Une nationalité "d'origine" désigne un réfugié politique reconnu". Statistiques Population étrangère. date=2 January 2008.

{{cite news}}: Missing pipe in:|publisher=(help) - Penalty gives Ghana victory over 10-man Serbia "...between 15,000 and 20,000 Serbs who live in South Africa"

- RTS :: Afrika i Srbija na vezi

- http://www.rts.rs/page/rts/sr/Dijaspora/story/1518/Vesti/1106406/Peticija+za+konzulat+u+Emiratima.html

- "Statistiques - 01.06.2008". Government of Luxembourg.

- http://www.ksh.hu/docs/hun/xftp/idoszaki/nepsz2011/nepsz_orsz_2011.pdf

- http://www.pressonline.rs/info/politika/62220/verovali-ili-ne-u-turskoj-zivi-9-miliona-srba.html

- Serbs Around the World Statistics

- СТАНКО НИШИЋ. Хрватска олуја и српске сеобе. Београд, 2002.

- Пашалић: Срба има око 12 милиона

- ec-European Commission - The Euromosaic study

- Final Results of the 2011 Kosovo census

- Number of Serbs in northern Kosovo disputed

- https://www.destatis.de/DE/Publikationen/Thematisch/Bevoelkerung/MigrationIntegration/AuslaendBevoelkerung2010200117004.pdf?__blob=publicationFile

- http://www.monstat.org/userfiles/file/popis2011/saopstenje/saopstenje%281%29.pdf

- "Verovali ili ne: U Turskoj Živi 9 Miliona Srba!", Press Online Serbia

- Heinz Kloss & Grant McConnel, Linguistic composition of the nations of the world, vol,5, Europe and USSR, Québec, Presses de l'Université Laval, 1984, ISBN 2-7637-7044-4

- "Projekat Rastko – Luzica / Project Rastko – Lusatia". Rastko.rs. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- J.P. Mallory and D.Q. Adams, "Protect", The Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture (London: Fitzroy and Dearborn, 1997)

- ^ Peričić, Marijana, et al. (2005). "High-Resolution Phylogenetic Analysis of Southeastern Europe Traces Major Episodes of Paternal Gene Flow Among Slavic Populations". Molecular Biology and Evolution 22(10). doi:10.1093/molbev/msi185 PMID 15944443.

N.B. The haplogroups' names in the section "Genetics" are according to the nomenclature adopted in 2008, as represented in Vincenza Battaglia (2008) Figure 2, so they may differ from the corresponding names in Peričić (2005). - ^ Battaglia, Vincenza; et al. (2008). "Y-chromosomal evidence of the cultural diffusion of agriculture in southeast Europe". European Journal of Human Genetics. 17 (6): 6. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2008.249. PMC 2947100. PMID 19107149.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|first1=(help) - ^ Marjanovic, D., et al. (2005). "The Peopling of Modern Bosnia-Herzegovina: Y-chromosome Haplogroups in the Three Main Ethnic Groups". Annals of Human Genetics 69. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8817.2005.00190.x PMID 16266413.

- ^ Simultaneous Administration of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale in 53 Nations: Exploring the Universal and Culture-Specific Features of Global Self-Esteem

- Kurir, Mondo (20 August 2012). "Istraživanje:Srbi narod najhrabriji". B92.

- De Administrando Imperio

- "Slavyane v rannem srednevekovie" Valentin V. Sedov (Russian language), Archaeological institute of Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, 1995

- Hupchick, Dennis P. The Balkans: From Constantinople to Communism. Palgrave Macmillan, 2004. ISBN 1-4039-6417-3

- "Пројекат Растко: Đorđe Janković : The Slavs in the 6th-Century North Illyricum". Rastko.rs. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- Ćorović 2001, Prvi Period – III

- Ćorović 2001, Drugi Period – II; Eginhartus de vita et gestis Caroli Magni, p. 192: footnote J10

- Ćorović 2001, Drugi Period – IV;

- Ćorović 2001, Drugi Period – V;

- ^ Ćorović 2001, Drugi Period – VII;

- Ćorović 2001, Drugi Period – VIII

- Ćorović 2001, Treći Period – I;

- Ćorović 2001, Treći Period – II;

- Agoston-Masters:Encyclopaedia of the Ottoman Empire ISBN 0-8160-6259-5 , p.518

- S.Aksin Somel :Historical Dictionary of the Ottoman Empire, Scarecrow Press Oxford, 2003, ISBN 0 8108 4332-3 p 268

- Jelavich, Barbara. History of the Balkans: Eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Volume 1 – page 94 . Cambridge University Press, 1983.

- Todorovic, Jelena. An Orthodox Festival Book in the Habsburg Empire: Zaharija Orfelin's Festive Greeting to Mojsej Putnik (1757) – Pages 7–8 . Ashgate Publishing, 2006

- Rados Ljusic, Knezevina Srbija

- ^ Misha Glenny. "The Balkans Nationalism, War and the Great Powers, 1804–1999". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- Royal Family. "200 godina ustanka". Royalfamily.org. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- Gordana Stokić (2003). "Bibliotekarstvo i menadžment: Moguća paralela" (PDF) (in Serbian). Narodna biblioteka Srbije.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Ćorović 2001, Novo Doba – VIII

- L. S. Stavrianos, The Balkans since 1453 (London: Hurst and Co., 2000), pp. 248–50

- Čedomir Antić (1998). "The First Serbian Uprising". The Royal Family of Serbia.

- MacKenzie p 22

- MacKenzie pp 22–3

- ^ MacKenzie pp 23–4

- MacKenzie p 9-10

- MacKenzie p. 24-33

- MacKenzie p 27

- Albertini (2005: 291–2).

- Albertini (2005: 364–480).

- "Pred Milunkom su i generali salutirali". 2009. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

- "The Balkan Wars and the Partition of Macedonia". Historyofmacedonia.org. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ”MacKenzie pp 36–7

- Albertini (1953, pp 19–23)

- Jordan 2008, p. 25

- Willmott 2003, p. 26 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFWillmott2003 (help)

- Willmott 2003, p. 27 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFWillmott2003 (help)

- ^ "The Balkan Wars and World War I". Library of Congress Country Studies.

- "Daily Survey". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Serbia. 23 August 2004.

- "$1,600,000 was raised for the Red Cross" (PDF). The New York Times. 29 October 1915.

- Tucker & Roberts 2005, pp. 1075–6 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFTuckerRoberts2005 (help)

- Početak povlačenja srpske vojske preko Albanije

- "Arhiv Srbije – osnovan 1900. godine" (in Serbian).

- 22 August 2009 Michael Duffy (22 August 2009). "First World War.com – Primary Documents – Vasil Radoslavov on Bulgaria's Entry into the War, 11 October 1915". firstworldwar.com. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Највећа српска победа: Фронт који за савезнике није био битан Template:Sr icon

- 22 August 2009 Matt Simpson (22 August 2009). "The Minor Powers During World War I – Serbia". firstworldwar.com. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - "Serbian army, August 1914". Vojska.net. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- "Tema nedelje: Najveća srpska pobeda: Sudnji rat: POLITIKA". Politika. 14 September 2008. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- Тема недеље : Највећа српска победа : Сви српски тријумфи : ПОЛИТИКА Template:Sr icon

- Loti, Pierre (30 June 1918). "Fourth of Serbia's population dead". Pqasb.pqarchiver.com. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- "Asserts Serbians face extinction". New York Times. 5 April 1918. Retrieved 14 November 2010.

- The Balkans since 1453. p. 624.

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (2006). The Three Yugoslavias: State-Building and Legitimation, 1918–2004. Indiana University Press. p. 119. ISBN 0-271-01629-9.