| Revision as of 12:56, 28 June 2013 editLecen (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users18,620 edits →Bibliography: + book← Previous edit | Revision as of 13:00, 28 June 2013 edit undoLecen (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users18,620 edits →Caudillo: + sourcesNext edit → | ||

| Line 93: | Line 93: | ||

| The ] of 1810 marked the early stages that would later lead to the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata's independence from Spain. Rosas, like many landowners in the countryside, were suspicious of a movement advanced primarily by merchants and bureucrats in the city of Buenos Aires. Rosas was specially outraged by the execution of Viceroy Santiago Linier at the hands of the revolutionaries. According to historian John Lynch, "Rosas did not disguise his preference for the colonial order and its guarantee of peace and unity. Rosas, like many of his kind, looked back on the colonial period as a golden age when law ruled and prosperity prevailed."{{sfn|Lynch|2001|p=3}} | The ] of 1810 marked the early stages that would later lead to the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata's independence from Spain. Rosas, like many landowners in the countryside, were suspicious of a movement advanced primarily by merchants and bureucrats in the city of Buenos Aires. Rosas was specially outraged by the execution of Viceroy Santiago Linier at the hands of the revolutionaries. According to historian John Lynch, "Rosas did not disguise his preference for the colonial order and its guarantee of peace and unity. Rosas, like many of his kind, looked back on the colonial period as a golden age when law ruled and prosperity prevailed."{{sfn|Lynch|2001|p=3}} | ||

| When the ] severed all remaining ties with Spain in July 1816, Rosas and his peers accepted independence as an accomplished fact.{{sfn|Lynch|2001|p=3}} With independence came a breakup of the territories which had formed the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata. Buenos Aires and the other provinces clashed over the power to be turned over to the central government versus the amount of autonomy to be preserved by provincial governments. A decade of strife over the issue destroyed the ties between capital and provinces, with new republics being declared throughout the country. Efforts by the Buenos Aires government to quash these independent states were met by determined local resistance.{{sfn|Lynch|2001|p=9}} In 1820 Rosas and his gauchos, all dressed in red which gave them the nickname "''Colorados del Monte''" ("Reds from the Mount"), enlisted in the army of Buenos Aires as the Fifth Regiment of Militia. They repulsed an invading force under ] hailing from the ], saving Buenos Aires.{{sfn|Lynch|2001|p=9}} | When the ] severed all remaining ties with Spain in July 1816, Rosas and his peers accepted independence as an accomplished fact.{{sfn|Lynch|2001|p=3}} With independence came a breakup of the territories which had formed the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata. Buenos Aires and the other provinces clashed over the power to be turned over to the central government versus the amount of autonomy to be preserved by provincial governments. A decade of strife over the issue destroyed the ties between capital and provinces, with new republics being declared throughout the country. Efforts by the Buenos Aires government to quash these independent states were met by determined local resistance.{{sfn|Lynch|2001|p=9}} In 1820 Rosas and his gauchos, all dressed in red which gave them the nickname "''Colorados del Monte''" ("Reds from the Mount"), enlisted in the army of Buenos Aires as the Fifth Regiment of Militia. They repulsed an invading force under ] hailing from the ], saving Buenos Aires.{{sfn|Lynch|2001|p=9}}{{sfn|Szuchman|Brown|1994|p=214}} | ||

| At the end of the conflict, Rosas returned to his ''estancias'' and remained there. He acquired prestige, was given the rank of colonel of cavalry and was awarded with further landholdings by the government.{{sfn|Lynch|2001|p=9}} These additions, together with his successful business and fresh property acquisitions, greatly boosted his wealth. By 1830, he was the 10th largest landowner in the ] (in which the city of the same name was located), owning 300,000 head of cattle and {{convert|420,000|acre}} of land.{{sfn|Lynch|2001|pp=26–27}} With his newly gained influence, military background, vast landholdings and a private army of gauchos loyal only to him, Rosas became the quintessential ].{{sfn|Lynch|2001|pp=1, 8, 13}} | At the end of the conflict, Rosas returned to his ''estancias'' and remained there. He acquired prestige, was given the rank of colonel of cavalry and was awarded with further landholdings by the government.{{sfn|Lynch|2001|p=9}}{{sfn|Szuchman|Brown|1994|pp=214–215}} These additions, together with his successful business and fresh property acquisitions, greatly boosted his wealth. By 1830, he was the 10th largest landowner in the ] (in which the city of the same name was located), owning 300,000 head of cattle and {{convert|420,000|acre}} of land.{{sfn|Lynch|2001|pp=26–27}} With his newly gained influence, military background, vast landholdings and a private army of gauchos loyal only to him, Rosas became the quintessential ].{{sfn|Lynch|2001|pp=1, 8, 13}} | ||

| ===Governor of Buenos Aires=== | ===Governor of Buenos Aires=== | ||

Revision as of 13:00, 28 June 2013

For the station, see Juan Manuel de Rosas (Buenos Aires Metro).This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Juan Manuel de Rosas | |

|---|---|

Juan Manuel de Rosas Juan Manuel de Rosas | |

| 17th Governor of Buenos Aires Province | |

| In office 7 March 1835 – 3 February 1852 | |

| Preceded by | Manuel Vicente Maza |

| Succeeded by | Vicente López y Planes |

| 13th Governor of Buenos Aires Province | |

| In office 8 December 1829 – 17 December 1832 | |

| Preceded by | Juan José Viamonte |

| Succeeded by | Juan Ramón Balcarce |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Juan Manuel José Domingo Ortiz de Rosas 30 March 1793 Buenos Aires, Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata |

| Died | March 14, 1877(1877-03-14) (aged 83) Southampton, United Kingdom |

| Nationality | Argentine |

| Political party | Federal Party |

| Spouse | Encarnación Ezcurra |

| Signature |  |

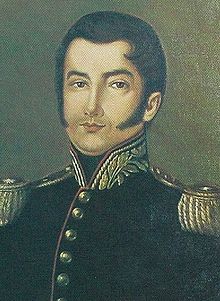

Juan Manuel de Rosas (March 30, 1793 – March 14, 1877), was an Argentine caudillo who served as governor of the Buenos Aires province and Supreme Chief of the Argentine Confederation. He was born to a wealthy family in the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata, but became a successful cattle ranching businessman by his own determination. A controversial figure, Rosas' support for both democracy and authoritarianism has baffled critics and historians, who to this day hold opposing views of the caudillo.

The political career of Juan Manuel de Rosas began in 1820, amidst the Argentine Civil Wars. In Buenos Aires, Rosas became leader of an effective armed resistance which propelled him to the governorship in 1829. Later, as leader of the Federal Pact, Rosas fought the Unitarian League, defeating it in 1831. His remaining term as governor oversaw economic and political stability through the formation of the Argentine Confederation, a federation of states modeled after the United States of America. After his term ended in 1832, Rosas refused to run again despite overwhelming popular support.

Returning to the Pampas, Rosas' focus shifted to securing the frontier from Amerindian malones (raiding bands) who attacked Argentine settlements. After securing alliances with friendly indigenous groups, he waged the 1832 First Conquest of the Desert against the Ranquel and Mapuche. The triumphant campaign greatly increased Buenos Aires' territory and pacified the Amerindians.

In 1835, continuing political instability and the controversial murder of Facundo Quiroga paved the way for Rosas' return to the governorship of Buenos Aires. He was elected by popular vote and given the sum of public power. Rosas' second term was marked by a strict social order lauded by his supporters and criticized for its brutality by his opponents. Although slavery was not abolished during his rule, Rosas sponsored liberal policies allowing them greater liberties.

Rosas' second term also dealt with a conflict against the Peru–Bolivian Confederation, as well as maritime blockades imposed by France and the United Kingdom, continuing problems with the Unitarians, and a belligerent Uruguay led by the Colorado Party. Ultimately, in the later stages of the Guerra Grande, Justo José de Urquiza (governor of Entre Ríos) united Rosas' political opponents and Brazil to decisively defeat Rosas in the 1852 Battle of Caseros. Deposed from power, Juan Manuel de Rosas spent the rest of his life exiled in Southampton, United Kingdom.

Early life

Birth

Juan Manuel José Domingo Ortiz de Rosas was born on 30 March 1793 at his family's town house in Buenos Aires, capital of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata. He was the first child of León Ortiz de Rosas and Augustina López de Osornio. León Ortiz was the son of an immigrant from the Spanish Province of Burgos who had an undistinguished military career and married into a wealthy Creole family. The greatest influence on young Juan Manuel de Rosas was his mother Augustina, a strong-willed and domineering woman who derived these character traits from her father, "a tough warrior of the Indian frontier who had died weapons in hand defending his southern estate in 1783."

Rosas was schooled at home, as was then common. Later, at age 8, he was enrolled in the finest private school in Buenos Aires. His education was unremarkable, though befitting a son of a wealthy landowner. According to historian John Lynch, it "was supplemented by his own efforts in the years that followed. Rosas was not entirely unread, though the time, the place, and his own bias limited the choice of authors. He appears to have had a sympathetic, if superficial, acquaintance with minor political thinkers of French absolutism."

In 1806, a British expeditionary force was dispatched to the Río de la Plata. A 13-year-old Rosas served in a force, organized by Viceroy Santiago Liniers to counter the invasion, distributing ammunition to troops. The British were defeated in August 1806. The British returned in 1807, and Rosas was assigned to the Caballería de los Migueletes (Cavalry of the Migueletes), although it is thought that he was barred from active duty during this time due to illness.

Estanciero

After the British invasions had been repelled, Rosas departed Buenos Aires with his parents for his family estancia (farm). His work on the estancia further shaped his character, grounding him in the Platine region's Hispanic-American social framework. In the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata, owners of large landholdings (including the Rosas family) provided food, equipment and protection both for themselves and for families living in areas under their control. Their private defense forces consisted primarily of laborers who were drafted as soldiers. Most of these peons, as such workers were called, were gauchos.

For the landed aristocracy of Spanish descent, the illiterate, mixed-race gauchos comprising the majority of the population were an ungovernable and untrustworthy sort. They were treated with with contempt by landowners, yet tolerated because there was no other labor force available. Rosas got along well with the gauchos under his service, despite his harsh and authoritarian comportment. He dressed liked them, joked with them, took part in their horse-play, shared their habits and paid them well. He never allowed them to forget, however, that he was their master, rather than their equal. Rosas was, according to Lynch, "a man of conservative instincts, a creature of the colonial society in which he had been formed, a defender of authority and hierarchy." He was, thus, merely a product of his time and not at all unlike the other great landowners in the Río de la Plata region.

Rosas gathered a working knowledge of administration and took charge of his family's estancias beginning in 1811. He was married to Encarnación Ezcurra y Arguibel, the daughter of wealthy Buenos Aires parents, in 1813. He soon afterward sought to forge a career for himself, leaving his parent's estate. He delved into the production of salted meat and began acquiring real property. As the years passed he became a estanciero (farmer) in his own right, accumulating land while establishing a successful partnership with his second cousins, the Anchorenas. His hard work and organizational skills in deploying labor were key to his success, rather than the employment of creative approaches to production.

Rise to power

Caudillo

The May Revolution of 1810 marked the early stages that would later lead to the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata's independence from Spain. Rosas, like many landowners in the countryside, were suspicious of a movement advanced primarily by merchants and bureucrats in the city of Buenos Aires. Rosas was specially outraged by the execution of Viceroy Santiago Linier at the hands of the revolutionaries. According to historian John Lynch, "Rosas did not disguise his preference for the colonial order and its guarantee of peace and unity. Rosas, like many of his kind, looked back on the colonial period as a golden age when law ruled and prosperity prevailed."

When the Congress of Tucumán severed all remaining ties with Spain in July 1816, Rosas and his peers accepted independence as an accomplished fact. With independence came a breakup of the territories which had formed the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata. Buenos Aires and the other provinces clashed over the power to be turned over to the central government versus the amount of autonomy to be preserved by provincial governments. A decade of strife over the issue destroyed the ties between capital and provinces, with new republics being declared throughout the country. Efforts by the Buenos Aires government to quash these independent states were met by determined local resistance. In 1820 Rosas and his gauchos, all dressed in red which gave them the nickname "Colorados del Monte" ("Reds from the Mount"), enlisted in the army of Buenos Aires as the Fifth Regiment of Militia. They repulsed an invading force under Estanislao López hailing from the province of Santa Fe, saving Buenos Aires.

At the end of the conflict, Rosas returned to his estancias and remained there. He acquired prestige, was given the rank of colonel of cavalry and was awarded with further landholdings by the government. These additions, together with his successful business and fresh property acquisitions, greatly boosted his wealth. By 1830, he was the 10th largest landowner in the province of Buenos Aires (in which the city of the same name was located), owning 300,000 head of cattle and 420,000 acres (170,000 ha) of land. With his newly gained influence, military background, vast landholdings and a private army of gauchos loyal only to him, Rosas became the quintessential caudillo.

Governor of Buenos Aires

| This section's factual accuracy is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please help to ensure that disputed statements are reliably sourced. (February 2013) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

As a governor, Rosas ruled with strict authority. He considered that, given the social segregation of the Argentine Confederation at the time, it was the only way to keep it together and prevent anarchy.

The King can be compared with a father, and reciprocally a father can be compared with the King, and then set the duties of the monarch by those of the parental authorithy. Love, govern, reward and punish is what a King and a father must do. In the end, there's nothing less legitimate than anarchy, which removes property and security from the people, as force becomes then the only right.

Rosas faced opposition from the unitarian provinces in the north. José María Paz, after defeating Facundo Quiroga at the battle of Tablada, took control of Cordoba province and started a reign of terror to destroy all federals in the zone, similar to the one started by Lavalle in Buenos Aires. The newspaper "La Gaceta" numbered the victims of the unitarian terror as 2,500 victims. Paz expanded his influence by creating the Unitarian League, while Rosas created the Federal Pact instead. The plans of Paz would fail when his horse was taken down and he was captured. Federalist José Vicente Reinafé, close to López, replaced him as governor of Córdoba. Córdoba, Santiago del Estero, La Rioja and the provinces of Cuyo joined the Federal Pact in 1831, Catamarca, Tucumán and Salta did so the following year. As for Paz himself, he was held captive by Estanislao López, who refused to execute him. He requested Rosas to check that it was the will of all the provinces to execute Paz, but Rosas did not accept the request. He considered that the fate of Paz should be decided solely by López, who held him prisoner.

One of the keys to the economic supremacy of Buenos Aires was its monopoly over the port and customs of Buenos Aires, the only one linking the Confederation with Europe. Rosas refused to lift control over it, considering that Buenos Aires faced alone the international debt that was generated by the Argentine War of Independence and the Cisplatine War.

The defeat of Paz and the expansion of the Federal Pact further ushered in a period of economic and political stability. As a result, Federalists were divided between two political trends: those who wanted the calling of a Constituent Assembly to write a Constitution, and those who supported Rosas in delaying it. Rosas thought that the best way to organize the Argentine Confederation was as a federation of federated states, similar to the successful States of the United States; each one should write its own local constitution and organize itself, and a national constitution should be written at the end, without being rushed.

He had a successful and popular first term, but refused to run for a second even though public support was strong.

Conquest of the Desert

Main article: First Conquest of the Desert

After his resignation as governor, Rosas left Buenos Aires and started the first Conquest of the Desert, to expand and secure the farming territories and prevent indigenous attacks. Rosas was aware that malones were not done because of evil desires but because of the lacking lifestyle condition of the indigenous peoples. As a result, he had preference for a policy of doing pacts or giving gifts or bribes to the caciques before employing military force. The hostile ranquel cacique Yanquetruz was replaced by Payné, who became a Rosas ally. Juan Manuel, in turn, adopted his son and raised him at his estancia. The pehuenche Cafulcurá was made colonel and allowed to distribute large numbers of gifts among his people; in turn, he made the compromise of not making any more malones. On the other hand, caciques like the pehuenche Chocorí who defied Rosas were defeated.

Charles Darwin met Rosas in 1833, and wrote about it in The Voyage of the Beagle. He was at Carmen de Patagones and knew that Rosas was located nearby, close to the Colorado River. He had heard about him from before, so he moved to meet him. He described him as a man of extraordinary character, a perfect horseman who conformed to the dress and habits of the Gauchos and "has a most predominant influence in the country, which it seems he will use to its prosperity and advancement". Although in a footnote added in the second edition published in 1845, Darwin notes that "This prediction has turned out to be entirely and miserably wrong." Darwin included a story of how Rosas had himself put in the stocks for inadvertently breaking his own rule of not wearing knives on Sundays. This appealed to his men's sense of egalitarianism and justice. Darwin also described an anecdote about a pair of buffoons.

By the end of the first Conquest of the Desert, Buenos Aires increased its lands by thousands of square kilometers, which were distributed among new and older hacendados. The natives did not make any more malones, accepted to provide military aid to Rosas in case of need, and stayed in peaceful terms for all the remainder of Rosas' government.

Even being absent, the political influence of Rosas in Buenos Aires was still strong, and his wife Encarnación Ezcurra was in charge of keeping good relations with the peoples of the city. On October 11, 1833, the city was filled with announcements of a trial against Rosas. A large number of gauchos and poor people made the Revolution of the Restorers, a demonstration at the gates of the legislature, praising Rosas and demanding the resignation of governor Juan Ramón Balcarce. The troops organized to fight the demonstration mutinied and joined it. The legislature finally gave up the trial, and a month later ousted Balcarce and replaced him with Juan José Viamonte. The Revolution also led to the creation of the Sociedad Popular Restauradora, also known as "Mazorca".

Later life

Second government

| This section's factual accuracy is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please help to ensure that disputed statements are reliably sourced. (February 2013) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The weak governments of Balcarce and Viamonte led the legislature to request Rosas to take the government once more. For doing so he requested the sum of public power, which the legislature denied four times. Rosas even resigned as commander of militias to influence the legislature. The context changed with the social commotion generated by the death of Facundo Quiroga, responsibility for which is disputed (different authors attribute it to Estanislao López, the Reinafé brothers, or Rosas himself). The legislature accepted then to give him the sum of public power. Even so, Rosas requested confirmation on whenever the people agreed with it, so the legislature organized a referendum about it. Every free man within the age of majority living in the city was allowed to vote for "Yes" or "No": 9.316 votes supported the release of the sum of public power on Rosas, and only 4 rejected it. There are divided opinions on the topic: Domingo Faustino Sarmiento compared Rosas with historical dictators, while José de San Martín considered that the situation in the country was so chaotic that a strong authority was needed to create order.

Although slavery was not abolished during Rosas' rule, Afro Argentines had a positive image of him. He allowed them to gather in groups related to their African origin, and financed their activities. Troop formations included many of them, because joining the army was one of the ways to become a free negro, and in many cases slave owners were forced to release them to strengthen the armies. There was an army made specifically of free negros, the "Fourth Battalion of Active Militia". The liberal policy towards slaves generated controversy with neighbouring Brazil, because fugitive Brazilian slaves saw Argentina as a safe haven: they were recognized as free men at the moment they crossed the Argentine borders, and by joining the armies they were protected from persecution of their former masters.

The people who opposed Rosas formed a group called Asociacion de Mayo or May Brotherhood. It was a literary group that became politically active and aimed at exposing Rosas' actions. Some of the literature against him includes The Slaughter House, Socialist Dogma, Amalia and Facundo. Meetings which had high attendance at first soon had few members attending out of fear of prosecution. Rosas' opponents during his rule were dissidents, such as José María Paz, Salvador M. del Carril, Juan Bautista Alberdi, Esteban Echeverria, Bartolomé Mitre and Domingo Faustino Sarmiento. Rosas political opponents were exiled to other countries, such as Uruguay and Chile.

First French blockade

Main article: French blockade of the Río de la Plata

The Peru–Bolivian Confederation declared the War of the Confederation against Argentina and Chile. Its protector Andrés de Santa Cruz supported European interests in South America, as well as the Unitarians, whereas Rosas and the Chilean Diego Portales did not. As a result, France gave full support to Santa Cruz in this war. Britain also supported Santa Cruz, but only by diplomatic means. Trusting in the military power at his disposal, Santa Cruz declared war against both countries at the same time. Initially, the Peruvian-Bolivian forces had the advantage, and captured and executed Portales. The war did not develop favorably for Argentina in the north, and the French Roger moved to Buenos Aires to request the surrender of Argentina. He demanded that two French citizens be released from prison, that two more be exempted from military service, and that France receive the same commercial privileges as granted by Bernardino Rivadavia to Britain. Although the demands themselves were not onerous, Rosas considered that they would set a precedent for further French interference in the internal affairs of Argentina, and refused to comply. As a result, France started a naval blockade against Buenos Aires.

Rosas took advantage of British interests in the zone: minister Manuel Moreno pointed out to the British Foreign Office that commerce between Argentina and Britain was being harmed by the French blockade, and that it would be a mistake for Britain to support it. The French judged that the people would seize the opportunity to stand against Rosas, but underestimated his popularity. With the nation being threatened by two European powers as well as two neighbouring countries allied with them, internal patriotic loyalty increased to the point that even some notable Unitarians who had fled to Montevideo returned to the country to offer their military help, such as Soler, Lamadrid and Espinosa. Things became more complicated for France as time passed: Andrés Santa Cruz was weakening, the strategy employed by Moreno was bearing fruit, and the French themselves started to have doubts about maintaining a conflict that they had expected to be quite short. Also, Britain would not allow the French to deploy troops, as they did not want a European competitor gaining territorial strength in the zone. Domingo Cullen, governor of Santa Fe replacing the ill López, considered that Rosas had nationalized a conflict that involved just Buenos Aires, and proposed to the French that they should encourage Santa Fe, Córdoba, Entre Ríos and Corrientes to secede, creating a new country that would obey them, if this new country would be spared the naval blockade. Also, Manuel Oribe, president of Uruguay and allied with Rosas, was ousted by Fructuoso Rivera with French aid. France wanted Rivera and Cullen to join forces and take Buenos Aires, while their ships kept the blockade. This alliance did not take place, as Juan Pablo López, brother of Estanislao López, defeated Cullen and drove him away from the province. Also, Andrés Santa Cruz was defeated by Chile in the Battle of Yungay, and the Peru–Bolivian Confederation ceased to exist. Now Rosas was free to focus all his attention on the French blockade.

His wife Encarnación died in Buenos Aires on October 20, 1838.

Rivera was urged by France to take military action against Rosas, but he was reluctant to do so, considering that the French underestimated his strength, even more after Santa Cruz's defeat. As a result, they elected Juan Lavalle to lead the attack, who asked not to share command with Rivera. As a result, each led his own army. His imminent attack was backed up by conspiracies in Buenos Aires, which were discovered and aborted by the Mazorca. Manuel Vicente Maza and his son were among the conspirators, and were executed as a result. Pedro Castelli also organized an ill-fated demonstration against Rosas, and was executed as well. Rosas did not wait to be attacked, and ordered Pascual Echagüe to cross the Parana river and move the fight to Uruguay. The Uruguayan armies split: Rivera returned to defend Montevideo, and Lavalle moved to Entre Ríos alone. He expected that local populations would join him against Rosas and increase his forces, but he found severe resistance, so he moved to Corrientes. Ferré defeated López, and Rivera defeated Echagüe, leaving Lavalle a clear path towards Buenos Aires. However, by that point France had lost faith in the effectiveness of the blockade, as what had been thought would be an easy and short conflict was turning into a long, possibly unwinnable, war. France started to negotiate for peace with the Confederation, and removed financial support from Lavalle. He found no help from local towns either, and there was strong desertion in his ranks. Buenos Aires was ready to resist Lavalle's attack, but his lack of support forced him to withdraw.

The civil war continues

The unitarians and colorados (federalists) kept up their hostilities against Rosas, even after the defeat of France. The new plan was that Ferré and Rivera, in Corrientes and Uruguay, would create a new army, while Lavalle and Lamadrid moved to the north. Lavalle would move to La Rioja and distract the Federal armies, while Lamadrid organized another army at Tucumán. By this time José María Paz had escaped from his imprisonment. Rosas spared his life because he had sworn never to attack the Confederation again, but he broke his oath. His presence benefited the anti-Rosas forces, but also generated internal strife: Ferré gave him the command of the armies of Corrientes, which Rivera did not like. Rivera even accused Paz of being a spy of Rosas. Nevertheless, the combined forces of Paz, Rivera and unitarian ships at the river had the federal forces of Echague at Santa Fe surrounded. To counter the unitarian naval supremacy Guillermo Brown organized a naval squadron; it defeated captain Coe at Santa Lucía.

Oribe defeated the forces of Lavalle at La Rioja, but Lavalle himself managed to escape to Tucuman. Lamadrid attacked San Juan, but was completely defeated. At Tucuman Oribed defeated Lavalle, who barely escaped with a group of 200 men to the north; he was killed shortly after in a confusing episode. This ended the anti-Rosas threat in the Argentine northwest.

Rivera threatened to end their alliance if Ferré insisted in favoring Paz. Rivera wanted to annex the Riograndense Republic (part of Rio Grande do Sul, that had declared independence from Brazil and was fighting the War of the Farrapos) and the Argentine mesopotamia into a projected Federation of Uruguay, but Paz was against that. Paz defeated Echague, and Rivera defeated the new federal governor of Entre Ríos, Justo José de Urquiza. Federalist Juan Pablo López from Santa Fe changed sides to the unitarian ranks.

Rosas was again in a weak position, and would not have been able to resist an attack. But Paz, Ferré, Rivera and López had conflicting battle plans, and their armies did not move, which gave Oribe time to return from the north. The forces of Santa Fe refused to fight for the unitarians, and massive defection reduced López's armies from 2.500 men to 500. He was easily defeated at Coronda and Paso Aguirre. Ferré was finally interested in Rivera's federation, and put Paz aside. Rivera and Oribe, both considering themselves rightful presidents of Uruguay, would battle. The battle of Arroyo Grande was a decisive victory for Oribe, and Rivera barely escaped alive. The unitarian threat to Rosas had been again removed.

Anglo-French blockade

Main article: Anglo-French blockade of the Río de la Plata

After the victory of Oribe at Arroyo Grande, Britain and France intervened in the conflict. Their ambassadors, Mandeville and De Lurde, demanded that Rosas retreat from Uruguayan territory. Rosas did not reply, and ordered Brown to support Oribe by blockading Montevideo. British commodore John Brett Purvis attacked the Argentine navy, taking over the vessels. Mandeville and De Lurde were replaced by Ousley and Deffaudis. The public purposes of the Anglo-French intervention were to protect the Uruguayan independence against Oribe, defend the recently-proclaimed independence of Paraguay, and end the civil wars in the La Plata River region. But there were also secret purposes: to turn Montevideo into a "commercial factory", to force the free navigation of the rivers, to turn the Argentine Mesopotamia into a new country, to set the borders of Uruguay, Paraguay and the Mesopotamia (without Brazilian intervention), and to help the anti-rosists to depose the governor of Buenos Aires and install one loyal to the European powers instead.

The European powers needed a convincing argument to justify a declaration of war. To this end, Florencio Varela requested that former Federalist José Rivera Indarte write a list of crimes that Rosas could be blamed for. The French firm Lafone & Co paid him with a penny for each death listed. The list, named Blood tables, included deaths caused by military actions of the unitarians (including Lavalle's invasion of Buenos Aires), soldiers shot during wartime because of mutiny, treason or espionage, victims of common crimes and even people who were still alive. He also listed Nomen nescio (NN) deaths (unidentified people); some entries were listed more than once. He also blamed Rosas for the death of Facundo Quiroga. With all this, Indarte listed 480 deaths, and was paid with two pounds sterling (about £140 in 2011 based on the retail price index, or £1500 based on average earnings). He tried to add to the list 22,560 deaths, the number caused by military conflicts in Argentina from 1829 to that date, but the French refused to pay for them. Indarte wrote in his libel that "it is a holy action to kill Rosas". Lafone & Co, who paid for the Blood tables, had control of Uruguayan customs, and would have greatly benefited from a new blockade of Buenos Aires. In March 1841, Indarte was the mastermind behind a failed bid against Rosas life, which consisted in sending him a firing device concealed in a diplomatic box, known as La Máquina Infernal ("The Infernal Machine").

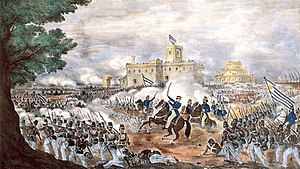

Giuseppe Garibaldi, commanding an Italian group, started hostilities by occupying Colonia del Sacramento and Isla Martín García, and led the controversial sack of Gualeguaychú. With the Uruguay river secured, the Anglo-French navy intended to control the Paraná river as well. Worried by the gravity of the danger, Rosas instructed Lucio Mancilla to fortify a section of the Parana to prevent the foreign navy from going any further. A similar study had been made years earlier by Hipólito Vieytes during the Argentine War of Independence, finding that a good strategic point was in Obligado.

An Anglo-French a convoy of three steamboats, many armed sailboats, and 90 merchant ships sailed up the Parana. Mansilla fortified Obligado with artillery, and closed the river with chains. The battle of Vuelta de Obligado took many hours, and the navy finally forced their way through. However, 38 merchant ships returned to Montevideo, and word of the unequal fight generated support for Rosas across most of South America. Mansilla continued the attack at San Lorenzo and Quebracho. The expedition was a commercial failure, and the second battle at Quebracho resulted in the sinking of several merchant vessels.

Although the Anglo-French force defeated Argentine forces, the cost of victory proved excessive in light of the ferocious resistance from the Argentines. As a result, the British sought to exit from the confrontation, followed later by their French allies. After long negotiations, Britain, and then France, agreed to lift the blockade. Both countries made a 21-gun salute to the flag of Argentina. Both treaties are viewed as a considerable triumph for General Rosas as it was the first time the emerging South American nations were able to impose their will on two European Empires.

Decline and fall

With the victory over Britain and France and the decline of the resistance in Montevideo, the civil war began to near its end, and several people who had fled from the country began to return to it. Rosas' tenure as governor was to end in 1850, but the legislature of Buenos Aires reelected him once more, rejecting his resignation. Several other provinces manifested their desire to keep Rosas in power: Córdoba, Salta, Mendoza, San Luis, Santa Fe, Catamarca. However, Justo José de Urquiza, governor of Entre Ríos, had growing conflicts with Rosas, and sought to depose him. For this purpose, he began to seek allies to reinforce him. His only support within the country was from Benjamín Virasoro, governor of Corrientes. Montevideo welcomed Urquiza's support, but Paraguay refused to join forces with him. On May 1, 1851, Urquiza announced that he accepted Rosas' resignation, retrieving for Entre Ríos the power to manage international relations delegated on Buenos Aires. Without ships, Urquiza sought the help of the Empire of Brazil as well. However, he thought that the Brazilian help would be of little use, and only agreed to accept them by the intervention of Herrera.

Urquiza began his military campaign in Uruguay, attacking the forces of Manuel Oribe. With the new military conflict, Rosas declined his resignation request. Without further support from Buenos Aires, Oribe was finally defeated, and his forces incorporated to those of Urquiza.

Rosas took the personal command of the forces of Buenos Aires, being critiziced by his generals Lucio Mansilla and Ángel Pacheco for his passivity. He did not attack Entre Ríos during Urquiza's campaign in Uruguay, when his forces would have had the advantage, and spent his time with trivial concerns. Entre Ríos, Corrientes, Brazil and Uruguay agreed the actions against Rosas in the secured Montevideo, where Entre Ríos and Corrientes would lead the operation and Uruguay and Brazil would provide only auxiliar armies. Urquiza defeated Rosas in the Battle of Caseros, on February 3, 1852.

Rosas spent the rest of his life in exile, in the United Kingdom, as a farmer in Southampton. He was resident at "Rockstone Lodge" No.8 Carlton Crescent (now known as "Ambassador House") from 1852 until 1865 when he moved to Burgess Street Farm.

Rosas inherited the 'combat saber' of General José de San Martin, maximum hero of Argentina, who praised Rosas for successfully defending Argentina against the European powers.

Criticism and historical perspective

| This section's factual accuracy is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please help to ensure that disputed statements are reliably sourced. (February 2013) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The figure of Juan Manuel de Rosas and his government generated strong conflicting viewpoints, both in his own time and afterwards.

In the context of the Argentine Civil War, Rosas was the main leader of the Federalist party, and as such the most part of the controversies around him were motivated by the preexistent antagonism of Federalism with the Unitarian Party. During the government of Rosas most unitarians fled to neighbour countries, mostly to Chile, Uruguay and Brazil; among them we can find Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, who wrote Facundo while living in Chile. Facundo is a critic biography of Facundo Quiroga, another federalist caudillo, but Sarmiento used it to pass many indirect or direct critics to Rosas himself. Some members of the 1837 generation, such as Esteban Echeverría or Juan Bautista Alberdi, tried to generate an alternative to the unitarians-federalists antagonism, but had to flee to other countries as well.

When Rosas was deposed in 1852 and the Unitarians took the government, they began a campaign to erase or denigrate the memory of Rosas and his legacy. The legislature charged him with High treason in 1857; the deputee Nicanor Arbarellos advocated for the political manipulation of history to make it reflect their own hatred for Rosas. President Bartolomé Mitre, enemy of Rosas, began this work by writing historical biographies highly critical of the caudillos, and creating a pantheon of national heroes to emulate. Establishing as well the newspaper La Nación and the National Academy of History of Argentina, his view of history became mainstream.

Historians began to weaken their ties with political power in the 1880 decade and wrote neutral works, avoiding the pro-Unitarian bias of the previous works. Adolfo Saldías wrote the first full biography of Rosas from a dispassionated point of view; Mitre critized it from a political perspective but praised it as a historical work. Ernesto Quesada made a new work with a positive tone about Rosas, which employed the ample archives kept by the family of Rosas. They are considered the first revisionist historians of Argentina. Thus, the hegemony of the mitrist view of history began to decline.

Historians became more independent in the 1910 decade, and established the "New School". Authors like Ravignani, Levene, Molinari and Carbia, whose generation came from the Great European immigration wave to Argentina rather from families in the country, had no involvement with the old disputes and sought to base their works on the usage of primary sources and unified standards rather than in the politics or social prestige of the authors.

Revisionism grew in the 1920s and 1930s decade, which is known as the "Golden Era in Argentine historiography". Authors like Manuel Gálvez and Leopoldo Lugones were influenced by their political ideas, which began in the left-wing and slowly moved to the right-wing. Liberal historiography, on the other hand, declined the former unanimous demonisation of federalism, caudillism and Rosas. President Juan Domingo Perón tried to avoid cultural controversies, and denied recognition to revisionism during his rule. Antiperonists made several comparisons between Perón and Rosas, and called his presidency the "Second Tyranny"; but the comparison backfired: the huge popularity of Perón and the huge social rejection for the antiperonist military coups led to a slow change in the social perception of Rosas and the popular acceptance of revisionism.

According to the historian Félix Luna, the disputes between supporters and detractors of Rosas are outdated, and modern historiography has incorporated the several corrections made by historical revisionism. Luna points that Rosas is no longer seen as a horrible monster, but as a common historical man as the others; and that it is anachronistic to judge him under modern moral standards. Horacio González, head of the National Library of the Argentine Republic, points a paradigm shift in the historiography of Argentina, where revisionism has moved from being the second most important perspective into being the mainstream one. However, divulgative historians often repeat outdated misconceptions about Rosas. This is usually the case of historians from outside of Argentina, who have no bias towards the Argentine topics but unwittingly repeat cliches that have long been refuted by Argentine historiography.

Legacy

| This section's factual accuracy is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please help to ensure that disputed statements are reliably sourced. (February 2013) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The date of November 20, anniversary of the battle of Vuelta de Obligado, has been declared "Day of National Sovereignty" of Argentina, following a request by revisionist historian José María Rosa. This observance day was raised in 2010 to a public holiday by Cristina Fernández de Kirchner. Rosas has been included in the banknotes of 20 Argentine pesos, with his face and his daughter Manuela Rosas in the front and a depiction of the battle of Vuelta de Obligado in the back. A monument of Rosas, 15 meters tall and with a weight of three tons, has been erected in 1999 in the city of Buenos Aires, at the conjunction of the "Libertador" and "Sarmiento" avenues.

The aforementioned law that charged Rosas of high treason was abrogated in 1974.

A portrait of Rosas was included in 2010 in a gallery of Latin American patriots, held at the Casa Rosada. The gallery, which included works provided by the presidents of other Latin American countries, was held because of the 2010 Argentina Bicentennial.

Silver and gold coins were struck during Rosas' tenure both with his portrait and without, but bearing his name. Portrait coins were issued in 1836 with a more youthful portrait and again in 1842 with a more mature portrait. Shown at right is a silver 8 soles (approx. 39 mm) coin from 1836.

See also

Endnotes

- Robert Bontine Cunninghame Graham described them as "herdsmen, who lived on horseback... In their great plains, roamed over by enormous herds of cattle, and countless horses in semi-feral state, each Gaucho lived in his own reed-built rancho daubed with mud to make its weathertight often without another neighbor nearer than a league away. His wife and children and possibly two or three other herdsmen, usually unmarried, to help him in the management of the cattle, made up his society. Generally he had some cattle of his own, and possibly a flock of sheep; but the great herds belonged to some proprietor who perhaps lived two or three leagues away."(Graham 1933, pp. 121–122)

- Template:Lang-es Template:Lang-en

Footnotes

References

- ^ Lynch 2001, p. 2.

- ^ Lynch 2001, p. 1.

- Lynch 2001, pp. 45–46.

- Lynch 2001, p. 46.

- Lynch 2001, p. 40.

- Lynch 2001, pp. 38–39.

- Lynch 2001, pp. 2, 8, 26.

- Lynch 2001, p. 28.

- ^ Lynch 2001, p. 3.

- ^ Lynch 2001, p. 9.

- Szuchman & Brown 1994, p. 214.

- Szuchman & Brown 1994, pp. 214–215.

- Lynch 2001, pp. 26–27.

- Lynch 2001, pp. 1, 8, 13.

- ^ Crow

- Chapter IV: Rio Negro To Bahía Blanca

- Historical value of money converter

- La Máquina Infernal Template:Es

- Ruiz Moreno, pp. 561–577

- Ruiz Moreno, pp. 577–595

- Ruiz Moreno, pp. 595–650

- Coles, R. J. (1981). Southampton's Historic Buildings. City of Southampton Society. p. 19.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - "El regreso del Sable Libertador". La Gazeta Federal. Retrieved December 27, 2012.

- "Rosas y San Martin". La Gazeta Federal. Retrieved December 27, 2012.

- Johnson, p. 111

- Rosa, José María. Historia Argentina, V. Buenos Aires. p. 491.

- Johnson, pp. 111-112

- Goebel, p. 29

- ^ Goebel, p. 30

- Johnson, p. 113

- Goebel, p. 32

- Goebel, p. 31

- ^ Goebel, p. 36

- Rein, p. 75

- Rein, p. 76

- Devoto, pp. 278-281

- ^ Félix Luna, "Con Rosas o contra Rosas", pp. 5–7

- Horacio González (November 23, 2010). "La batalla de Obligado" (in Spanish). Página 12. Retrieved June 27, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Lascano, pp. 46-47

- H.Cámara de diputados de la Nación

- Día de la soberanía nacional

- Por decreto, el Gobierno incorporó nuevos feriados al calendario Template:Es

- Emplazaron en Palermo una estatua de Juan Manuel de Rosas

- Galería de los Patriotas Latinoamericanos abrió ante siete presidentes Template:Es

Bibliography

- Bethell, Leslie (1993). Argentina since independence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-43376-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Darwin, Charles (2008). The Voyage of the Beagle. New York: Cosimo. ISBN 978-1-60520-565-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Graham, Robert Bontine Cunninghame (1933). Portrait of a dictator. London: William Heinemann.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lynch, John (2001). Argentine Caudillo: Juan Manuel de Rosas (2 ed.). Wilmington, Delaware: SR Books. ISBN 0-8420-2897-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Szuchman, Mark D.; Brown, Jonathan Charles (1994). Revolution and Restoration: The Rearrangement of Power in Argentina, 1776–1860. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-4228-x.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- Rosas en la historiografía Argentina Template:Es

- Juan Manuel de Rosas y sus muchas huellas Template:Es

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded byJuan José Viamonte | Governor of Buenos Aires Province (Head of State of Argentina) 1829–1832 |

Succeeded byJuan Ramón Balcarce |

| Preceded byManuel Vicente Maza | Governor of Buenos Aires Province (Head of State of Argentina) 1835–1852 |

Succeeded byVicente López y Planes |

| Heads of state of Argentina | ||

|---|---|---|

| May Revolution and Independence War Period up to Asamblea del Año XIII (1810–1814) | ||

| Supreme directors of the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata (1814–1820) | ||

| Unitarian Republic – First Presidential Government (1826–1827) | ||

| Pacto Federal and Argentine Confederation (1827–1862) | ||

| National Organization – Argentine Republic (1862–1880) | ||

| Generation of '80 – Oligarchic Republic (1880–1916) | ||

| First Radical Civic Union terms, after secret ballot (1916–1930) | ||

| Infamous Decade (1930–1943) | ||

| Revolution of '43 – Military Dictatorships (1943–1946) | ||

| First Peronist terms (1946–1955) | ||

| Revolución Libertadora – Military Dictatorships (1955–1958) | ||

| Fragile Civilian Governments – Proscription of Peronism (1958–1966) | ||

| Revolución Argentina – Military Dictatorships (1966–1973) | ||

| Return of Perón (1973–1976) | ||

| National Reorganization Process – Military Dictatorships (1976–1983) | ||

| Return to Democracy (1983–present) | ||

| Argentine Civil Wars (1814–76) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parties involved (leaders) |

| ||||

| Battles | |||||

| Treaties | |||||

| See also | |||||

- Misplaced Pages neutral point of view disputes from December 2012

- Governors of Buenos Aires Province

- Argentine brigadiers

- Federales (Argentina)

- Juan Manuel de Rosas

- Argentine Roman Catholics

- Argentine people of Spanish descent

- Attempted assassination survivors

- People from Buenos Aires

- Burials at La Recoleta Cemetery

- 1793 births

- 1877 deaths