| Revision as of 09:20, 9 August 2013 edit42.82.195.14 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 11:16, 9 August 2013 edit undoDinoguy2 (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users39,966 editsNo edit summaryNext edit → | ||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

| {{Automatic taxobox | {{Automatic taxobox | ||

| | name = ''Alamosaurus'' | | name = ''Alamosaurus'' | ||

| | fossil_range = ], {{Fossil range| |

| fossil_range = ], {{Fossil range|69|68}} | ||

| | taxon = |

| taxon = Alamosaurus | ||

| | image = Alamosaurus sanjuanensis dinosaur.png | | image = Alamosaurus sanjuanensis dinosaur.png | ||

| | image_width = 250px | | image_width = 250px | ||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''''Alamosaurus''''' ({{IPAc-en|ˌ|æ|l|əm|ɵ|ˈ|s|ɔr|ə|s}}; meaning "Ojo Alamo lizard") is a ] of ]n ] ] from the Late ] ] of what is now ]. It was a large ]al ]. Isolated ]e and limb bones indicate that it reached ] to '']'' and '']'', which would make it the largest dinosaur known from North America.<ref name=DFRS11 /> Its fossils have been recovered from the Naashoibito member of the ] (sometimes considered part of the ]) and equivalent geological units, which have been dated to the ] age of the ] period, specifically between about |

'''''Alamosaurus''''' ({{IPAc-en|ˌ|æ|l|əm|ɵ|ˈ|s|ɔr|ə|s}}; meaning "Ojo Alamo lizard") is a ] of ]n ] ] from the Late ] ] of what is now ]. It was a large ]al ]. Isolated ]e and limb bones indicate that it reached ] to '']'' and '']'', which would make it the largest dinosaur known from North America.<ref name=DFRS11 /> Its fossils have been recovered from the Naashoibito member of the ] (sometimes considered part of the ]) and equivalent geological units, which have been dated to the ] age of the ] period, specifically between about 69-68 million years ago.<ref name="sullivan2006">Sullivan, R.M., and Lucas, S.G. 2006. "." New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, Bulletin 35:7-29.</ref> | ||

| ==Naming== | ==Naming== | ||

| Line 30: | Line 30: | ||

| ==History of discovery== | ==History of discovery== | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ''Alamosaurus'' remains have been discovered throughout the ]. The ] was discovered in the Naashoibito Member of the ] (or ] under a different definition) of ] which was deposited during the ] stage of the ] Period. Bones have also been recovered from other Maastrichtian formations, like the ] of ] and the ], ] and ] Formations of ]. It used to be thought that these formations were deposited immediately prior to the ], 65 million years ago. | ''Alamosaurus'' remains have been discovered throughout the ]. The ] was discovered in the Naashoibito Member of the ] (or ] under a different definition) of ] which was deposited during the ] stage of the ] Period. Bones have also been recovered from other Maastrichtian formations, like the ] of ] and the ], ] and ] Formations of ]. It used to be thought that these formations were deposited immediately prior to the ], 65 million years ago. However, recent research has revised this view: there is no evidence that the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary (K–T boundary) is present in any of them, and they are more likely to be early-mid Maastrichtian in age (~69 million years old) <ref name="lehman-etal-2006-difley-2007-lucas-etal-2009">Lehman, et al. (2006). Difley (2007). Lucas, et al. (2009).</ref> | ||

| Gilmore originally described a ] (shoulder bone) and ] (] bone) in 1922. In 1946, he found a more complete specimen in Utah, consisting of a complete tail, a right forelimb complete except for the tips of the toes, and both ischia. Since then, many other bits and pieces from Texas, New Mexico, and Utah have been referred to ''Alamosaurus'', often without much description. The most completely known specimen is a recently discovered juvenile skeleton from Texas, which allowed educated estimates of length and mass.<ref name="lehman-coulson-2002" /> | Gilmore originally described a ] (shoulder bone) and ] (] bone) in 1922. In 1946, he found a more complete specimen in Utah, consisting of a complete tail, a right forelimb complete except for the tips of the toes, and both ischia. Since then, many other bits and pieces from Texas, New Mexico, and Utah have been referred to ''Alamosaurus'', often without much description. The most completely known specimen is a recently discovered juvenile skeleton from Texas, which allowed educated estimates of length and mass.<ref name="lehman-coulson-2002" /> | ||

Revision as of 11:16, 9 August 2013

| Alamosaurus Temporal range: Late Cretaceous, 69–68 Ma PreꞒ Ꞓ O S D C P T J K Pg N ↓ | |

|---|---|

| |

| Restoration | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Missing taxonomy template (fix): | Alamosaurus sanjuanensis |

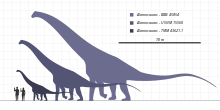

Alamosaurus (/ˌæləmˈsɔːrəs/; meaning "Ojo Alamo lizard") is a genus of titanosaurian sauropod dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous Period of what is now North America. It was a large quadrupedal herbivore. Isolated vertebrae and limb bones indicate that it reached sizes comparable to Argentinosaurus and Puertasaurus, which would make it the largest dinosaur known from North America. Its fossils have been recovered from the Naashoibito member of the Ojo Alamo Formation (sometimes considered part of the Kirtland Formation) and equivalent geological units, which have been dated to the Maastrichtian age of the Cretaceous period, specifically between about 69-68 million years ago.

Naming

Contrary to popular assertions, this dinosaur is not named after the Alamo in San Antonio, Texas, or the battle that was fought there. The holotype, or original specimen, was discovered in New Mexico and, at the time of its naming, Alamosaurus had not yet been found in Texas. Instead, the name Alamosaurus comes from Ojo Alamo, the geologic formation in which it was found and which was, in turn, named after the nearby Ojo Alamo trading post (since this time there has been some debate as to whether to reclassify the Alamosaurus-bearing rocks as belonging to the Kirtland Formation or whether they should remain in the Ojo Alamo Formation). The term alamo itself is a Spanish word meaning "poplar" and is used for the local subspecies of cottonwood tree. The term saurus is derived from saura (σαυρα), Greek for "lizard" and is the most common suffix used in dinosaur names. There is one species (A. sanjuanensis), which is named after San Juan County, New Mexico, where the first remains were found. Both genus and species were named by Smithsonian paleontologist Charles W. Gilmore in 1922.

Anatomy

The vertebrae from the middle part of its tail had elongated centra. Alamosaurus had vertebral lateral fossae that resembled shallow depressions. Fossae that similarly resemble shallow depressions are known from Saltasaurus, Malawisaurus, Aeolosaurus, and Gondwanatitan. Venenosaurus also had depression-like fossae, but its "depressions" penetrated deeper into the vertebrae, were divided into two chambers, and extend farther into the vertebral columns.

Alamosaurus had more robust radii than Venenosaurus.

Classification

Alamosaurus is undoubtedly a derived member of Titanosauria, but relationships within that group are far from certain. One major analysis unites Alamosaurus with Opisthocoelicaudia in a subfamily Opisthocoelicaudinae of the family Saltasauridae A major competing analysis finds Alamosaurus as a sister taxon to Pellegrinisaurus, with both genera located just outside Saltasauridae. Other scientists have also noted particular similarities with the saltasaurid Neuquensaurus and the Brazilian Trigonosaurus (the "Peiropolis titanosaur") which is used in many cladistic and morphologic analyses of titanosaurians.

History of discovery

Alamosaurus remains have been discovered throughout the southwestern United States. The holotype was discovered in the Naashoibito Member of the Ojo Alamo Formation (or Kirtland Formation under a different definition) of New Mexico which was deposited during the Maastrichtian stage of the Late Cretaceous Period. Bones have also been recovered from other Maastrichtian formations, like the North Horn Formation of Utah and the Black Peaks, El Picacho and Javelina Formations of Texas. It used to be thought that these formations were deposited immediately prior to the end of the Cretaceous, 65 million years ago. However, recent research has revised this view: there is no evidence that the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary (K–T boundary) is present in any of them, and they are more likely to be early-mid Maastrichtian in age (~69 million years old)

Gilmore originally described a scapula (shoulder bone) and ischium (pelvic bone) in 1922. In 1946, he found a more complete specimen in Utah, consisting of a complete tail, a right forelimb complete except for the tips of the toes, and both ischia. Since then, many other bits and pieces from Texas, New Mexico, and Utah have been referred to Alamosaurus, often without much description. The most completely known specimen is a recently discovered juvenile skeleton from Texas, which allowed educated estimates of length and mass.

No skull material is known, except for a few slender teeth, and no armor scutes have been reported, such as those found in other advanced titanosaurians like Saltasaurus.

Paleobiogeography

Skeletal elements of Alamosaurus are among the most common Late Cretaceous dinosaur fossils found in the United States Southwest and are now used to define the fauna of that time and place. In the south of Late Cretaceous North America, the transition from the Edmontonian to the Lancian is even more dramatic than it was in the north. Thomas M. Lehman describes it as "the abrupt reemergence of a fauna with a superficially 'Jurassic' aspect." These faunas are dominated by Alamosaurus and feature abundant Quetzalcoatlus in Texas. The Alamosaurus-Quetzalcoatlus association probably represent semi-arid inland plains.

The appearance of Alamosaurus may have represented an immigration event from South America. Some taxa may have co-occurred on both continents, including Kritosaurus and Avisaurus. Alamosaurus appears and achieves dominance in its environment very abruptly, which might support the idea that it originated following an immigration event. Other scientists speculated that Alamosaurus was an immigrant from Asia. However, critics of the immigration hypothesis note that inhabitants of an upland environment like Alamosaurus are more likely to be endemic than coastal species, and tend to have less of an ability to cross bodies of water. Further, Early Cretaceous titanosaurs are already known, so North American potential ancestors for Alamosaurus already existed.

Other contemporaneous dinosaurs from that part of the world include tyrannosaurs, smaller theropods, the hadrosaur Edmontosaurus sp., the ankylosaur Glyptodontopelta, and the ceratopsids Torosaurus utahensis and Ojoceratops fowleri.

Footnotes

- Fowler and Sullivan (2011).

- Sullivan, R.M., and Lucas, S.G. 2006. "The Kirtlandian land-vertebrate "age" – faunal composition, temporal position and biostratigraphic correlation in the nonmarine Upper Cretaceous of western North America." New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, Bulletin 35:7-29.

- "Caudal Vertebrae," Tidwell, Carpenter, and Meyer (2001). Page 145.

- ^ "Caudal Vertebrae," Tidwell, Carpenter, and Meyer (2001). Page 147.

- "Forelimb," Tidwell, Carpenter, and Meyer (2001). Page 148.

- Wilson (2002).

- Upchurch, et al. (2004).

- ^ Lehman and Coulson (2002).

- Lehman, et al. (2006). Difley (2007). Lucas, et al. (2009).

- "Lancian Turnover," Lehman (2001); page 317.

- "Lancian Turnover," Lehman (2001); pages 317-319.

- "Loss of Wetlands Hypothesis," Lehman (2001); page 320.

- ^ "Competition from Invaders Hypothesis," Lehman (2001); page 321.

References

- Difley, R. 2007. Biostratigraphy of the North Horn Formation at North Horn Mountain, Emery County, Utah. In: G.C. Willis, M.D. Hylland, D.L. Clark, and T.C. Chidsey Jr (eds.) Central Utah – Diverse Geology of a Dynamic Landscape, 439-454. Utah Geological Association Publication 36, Salt Lake City, Utah.

- Fowler, Denver W. (2011). "The First Giant Titanosaurian Sauropod from the Upper Cretaceous of North America". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 56 (4): 685–690. doi:10.4202/app.2010.0105. ISSN 0567-7920.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Gilmore, C.W. 1922. A new sauropod dinosaur from the Ojo Alamo Formation of New Mexico. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections. 72(14): 1-9.

- Gilmore, C.W. 1946. Reptilian fauna of the North Horn Formation of central Utah. U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper. 210-C:29-51.

- Lehman, T. M., 2001, Late Cretaceous dinosaur provinciality: In: Mesozoic Vertebrate Life, edited by Tanke, D. H., and Carpenter, K., Indiana University Press, pp. 310–328.

- Lehman, T.M. & Coulson, A.B. 2002. A juvenile specimen of the sauropod Alamosaurus sanjuanensis from the Upper Cretaceous of Big Bend National Park, Texas. Journal of Palaeontology. 76(1): 156-172.

- Lehman, T.M., McDowell, F.W., and Connelly, J.N. 2006. First isotopic (U-PB) age for the Late Creatceous Alamosaurus vertebrate fauna of West Texas and its significance as a link between two faunal provinces. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 26: 922-928.

- Lucas, S.G, Sullivan, R.M., Cather, S.M., Jasinski, S.E, Fowler, D.W., Heckert, A.B., Spielmann, J.A, & Hunt, A.P. 2009. No definitive evidence of Paleocene dinosaurs in the San Juan Basin, Paleontologica electronica 12(2); 8A: 10p.

- Tidwell, V., Carpenter, K. & Meyer, S. 2001. New Titanosauriform (Sauropoda) from the Poison Strip Member of the Cedar Mountain Formation (Lower Cretaceous), Utah. In: Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. D. H. Tanke & K. Carpenter (eds.). Indiana University Press, Eds. D.H. Tanke & K. Carpenter. Indiana University Press. 139-165.

- Upchurch, P., Barrett, P.M. & Dodson, P. 2004. Sauropoda. In: Weishampel, D.B., Dodson, P., & Osmolska, H. (Eds.) The Dinosauria (2nd Edition). Berkeley: University of California Press. Pp. 259–322.

- Wilson, J.A. 2002. Sauropod dinosaur phylogeny: critique and cladistic analysis. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 136: 217-276.