| Revision as of 20:21, 2 June 2013 editTom harrison (talk | contribs)Administrators47,534 editsm Reverted edits by 209.179.76.129 (talk) to last version by Ctxppc← Previous edit | Revision as of 20:37, 4 November 2013 edit undoStAnselm (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, File movers, New page reviewers, Pending changes reviewers160,812 edits This article has historically used "AD" datingNext edit → | ||

| (112 intermediate revisions by 8 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

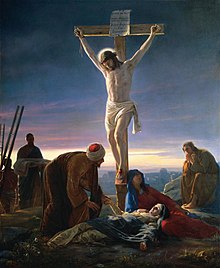

| ] (1834-1890), showing the skies darkened]] | |||

| ] from August 2008. It takes about an hour for the moon to cover the sun, with total coverage lasting a few minutes.<ref>''Astronomy: The Solar System and Beyond'' by Michael A. Seeds, Dana Backman, 2009 ISBN 0-495-56203-3 page 34</ref>]] | |||

| According to the Christian ]s, on the day ] ] there was a period of darkness in the afternoon for three hours. Although ancient and medieval writers treated this as a ], modern writers tend to view it either as a literary invention or a natural phenomenon, such as a ]. Some writers, interpreting it as an eclipse, have sought to use it as a way of establishing the date of Jesus' crucifixion. | |||

| ] from March 2007. A lunar eclipse can last a few hours, total coverage being about an hour.<ref></ref> ]'s reference to a "moon of blood" in {{Bibleref2|Acts|2:20}} has been used to infer the date of the Crucifixion.]] | |||

| According to the Christian ]s, on the day ], darkness covered the land for hours, an event which later came to be referred to as the "'''crucifixion eclipse'''". Although medieval writers treated the darkness as a ], various Christian historians have associated it with prophecies and other reports of eclipses or periods of darkness. Using this period of darkness as a marker, and interpreting it as a ] or ], writers have suggested dates for Jesus' crucifixion. | |||

| ==Biblical account== | ==Biblical account== | ||

| :''See also ] and ]'' | :''See also ]'' | ||

| The original biblical reference is in the ], usually dated around the year 70 AD.{{sfnp|Witherington|2001|p=31|ps=: 'from 66 to 70, and probably closer to the latter'}}{{sfnp|Hooker|1991|p=8|ps=: 'the Gospel is usually dated between AD 65 and 75.'}} In its account of the death of Jesus, on the eve of ], it says that after Jesus was crucified at nine in the morning, darkness fell over all the land, or all the world ({{lang-grc-gre|γῆν|gēn}} can mean either) from around noon ("the sixth hour") until 3 o'clock ("the ninth hour"): | |||

| {{quotation|When it was noon, darkness came over the whole land until three in the afternoon.|{{bibleref2|Mark|15:33|NRSV}}}} | |||

| {{quotation|Now from the sixth hour there was darkness over all the land unto the ninth hour. (…) And, behold, the veil of the temple was rent in twain from the top to the bottom; and the earth did quake, and the rocks rent; And the graves were opened; and many bodies of the saints which slept arose, And came out of the graves after his resurrection, and went into the holy city, and appeared unto many. Now when the centurion, and they that were with him, watching Jesus, saw the earthquake, and those things that were done, they feared greatly, saying, Truly this was the Son of God. | |||

| |{{bibleref2|Matthew|27:45|KJV}}, {{bibleref2-nb|Matthew|27:51-54|KJV}}}} | |||

| The account adds a detail that follows immediately on the death of Jesus: | |||

| {{quotation|And when the sixth hour was come, there was darkness over the whole land until the ninth hour.|{{bibleref2|Mark|15:33|KJV}}}} | |||

| {{quotation|And |

{{quotation|And the curtain of the temple was torn in two, from top to bottom.|{{bibleref2|Mark|15:38|NRSV}}}} | ||

| The ], written around the year 85 or 90 AD, and using Mark as a source,{{sfnp|Harrington|1991|p=8}} has an almost identical wording: | |||

| ==Early Christian texts== | |||

| {{quotation|From noon on, darkness came over the whole land until three in the afternoon.|{{bibleref2|Matthew|27:45|NRSV}}}} | |||

| ===Apocrypha - Non Canonized Texts=== | |||

| {{Gospel Jesus}} | |||

| The divisions in the apocryphal '']'', known as the Acts of Pilate, Christ’s Descent into Hell, and The Paradosis, refer to a variety of physical phenomena accompanying the crucifixion and the subsequent executive responses by Caesar. According to Chapter XI of the Acts of Pilate, the darkness had started at midday; lasted three hours, and had been caused by the darkening of the Sun.<ref>Acts of Pilate. In W. Barnston (Ed.) (1984). ''The Other Bible'' (pp. 368). New York: HarperCollins Publishers ISBN 0-06-250030-9.</ref> It also stated Pilate and his wife were disturbed by a report of what had happened. The Judeans he had summoned said it was an ordinary solar eclipse. The Christ’s Descent into Hell described the many dead who had arisen and had appeared to many in Jerusalem shortly after the resurrection of Christ.<ref>Christ’s Descent into Hell. In W. Barnston (Ed.) (1984). ''The Other Bible'' (pp. 374). New York: HarperCollins Publishers ISBN 0-06-250030-9.</ref> And, the Paradosis presented the interrogations in Rome by Caesar and his subsequent decree of severe punishment against both Pilate and the Judeans for causing the darkness and earthquake that had fallen upon the whole world.<ref>The Paradosis. In W. Barnston (Ed.) (1984). ''The Other Bible'' (pp. 378-379). New York: HarperCollins Publishers ISBN 0-06-250030-9.</ref> | |||

| The Matthew account adds some dramatic details, including an earthquake and the raising of the dead, which were stock motifs from Jewish apocalyptic literature:{{sfnp|Yieh|2004|p=65}}{{sfnp|Funk|1998|pp=129-270|ps=, "Matthew".}} | |||

| Other apocryphal works contain briefer accounts of the crucifixion darkness. The '']'' stated darkness had accompanied the crucifixion of Christ.<ref>Gospel of Bartholomew. In W. Barnston (Ed.) (1984). ''The Other Bible'' (p. 351). New York: HarperCollins Publishers ISBN 0-06-250030-9.</ref> The division of '']'' known as the Revelation of the Mystery of the Cross stated the darkness had started at the sixth hour and had covered the whole world.<ref>Revelation of the Mystery of the Cross. In W. Barnston (Ed.) (1984). ''The Other Bible'' (p. 419). New York: HarperCollins Publishers ISBN 0-06-250030-9.</ref> | |||

| {{quotation|(…) At that moment the curtain of the temple was torn in two, from top to bottom. The earth shook, and the rocks were split. The tombs also were opened, and many bodies of the saints who had fallen asleep were raised. After his resurrection they came out of the tombs and entered the holy city and appeared to many. Now when the centurion and those with him, who were keeping watch over Jesus, saw the earthquake and what took place, they were terrified and said, “Truly this man was God’s Son!” | |||

| ===Letters=== | |||

| |{{bibleref2-nb|Matthew|27:51-54|NRSV}}}} | |||

| The purported ''Letter from Pontius Pilate to Tiberius'' claimed the darkness had started at the sixth hour, covered the whole world and, during the subsequent evening, the full moon resembled blood for the entire night.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://bibleprobe.com/pontius_pilate.htm |title=Pontius Pilate |publisher=Bibleprobe.com |date= |accessdate=2011-02-28}}</ref> The '']'' stated that the darkness began at midday, covered the whole of Judaea, and led people to go about with lamps believing it to be night.<ref>'''' 5.15–19.</ref> | |||

| The ], written around the year 90 AD and also using Mark as a source,{{sfnp|Davies|2004|p=xii}} has none of the details added in the Matthew version, moves the tearing of the temple veil to before the death of Jesus{{sfnp|Evans|2011|p=308}} and includes an explanation that the sun was darkened,{{sfnp|Henige|2005|p=150}}{{sfnp|Funk|1998|pp=267-364|ps=, "Luke".}} appearing to explain it as an eclipse:{{sfnp|Loader|2002|p=356}} | |||

| In letters written under the name ] the author claims to have observed a solar eclipse from ] at the time of the crucifixion.<ref>{{cite book |last=Parker |first=John |title=The Works of Dionysius the Arepagite |chapter=Letter VII. Section II. To Polycarp--Hierarch. & Letter XI. Dionysius to Apollophanes, Philosopher. |year=1897 |pages=148–149, 182–183 |publisher=James Parker and Co. |location=London |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=D7noNM1MNDcC&lpg=PP1&pg=PA182#v=onepage&q&f=false}}</ref> According to the Orthodox Church in America,<ref></ref> Dionysius, who is mentioned in Acts 17:34, was from Athens and received a classical Greek education(i.e. Atticism). He studied astronomy at the city of Heliopolis, and it was in Heliopolis, along with his friend Apollophonos where he witnessed the solar eclipse that occurred at the moment of the death of the Lord Jesus Christ by Crucifixion. (The connection between the events was surely realized by him at a later date.) But even so, at the time of the eclipse he said, "Either the Creator of all the world now suffers, or this visible world is coming to an end." | |||

| {{quotation|It was now about noon, and darkness came over the whole land until three in the afternoon, while the sun’s light failed ; and the curtain of the temple was torn in two. |{{bibleref2|Luke|23:44-45|NRSV}}}} | |||

| The '']'', a 19th-century forgery purporting to be a collection of ancient documents concerning Jesus, contains a report by Pontius Pilate about the crucifixion events. | |||

| The account given in the ] is different: it takes place on the day of Passover,{{sfnp|Barclay|2001| p=340}} the crucifixion does not take place until after noon, and there is no mention of darkness, the tearing of the veil, or the raising of the dead.{{sfnp|Broadhead|1994|p=196}} | |||

| ==Ancient historians== | |||

| The 3rd-century Christian historian ], in a section of his work surviving in quotation by ], stated that the chronicler ] had called the darkness during the crucifixion a solar eclipse.<ref name=Africanus>George Syncellus, ''Chronography'' .</ref> Africanus objected based on the fact that a solar eclipse could not occur during ]; the festival is held at a ] while a solar eclipse can only occur during a ]. It is unclear whether Thallus himself made any reference to the crucifixion.<ref>Loveday Alexander, 'The Four among pagans' in Bockmuehl and Hagner, eds, ''The Written Gospel'', (Cambridge University Press, 2005), page 225.</ref> | |||

| ==Later versions== | |||

| Africanus also cites the 2nd-century chronicler ]: "Phlegon records that during the reign of Tiberius Caesar there was a complete solar eclipse at full moon from the sixth to the ninth hour". The church historian ] (264 – 340), in his '']'', quotes Phlegon as saying that during the fourth year of the 202nd ] (AD 32/33) "a great eclipse of the sun occurred at the sixth hour that excelled every other before it, turning the day into such darkness of night that the stars could be seen in heaven, and the earth moved in ], toppling many buildings in the city of ]".<ref>, Olympiad 202, trans. Carrier (1999).</ref> It has been suggested that this was the eclipse of November 24, 29 AD in the first year of the Olympiad, the number Α' (1st) having been corrupted to Δ' (4th).<ref name=Africanus/> In a 2005 paper, ] points out that the sources do not mention Jerusalem in connection with the earthquake.<ref name="Ambraseys, N. 2005"> by Nicolas Ambraseys (Νικόλαος Αμβράζης), Journal of Seismology, 9, 329-340 (2005).</ref> | |||

| ===Apocryphal writers=== | |||

| ], in his ''Apologeticus'', tells the story of the darkness that had commenced at noon during the crucifixion; those who were unaware of the prediction, he says, "no doubt thought it an eclipse".<ref> cited in Bouw, G. D. (1998, Spring). The darkness during the crucifixion. ''The Biblical Astronomer'', '''8'''(84). Retrieved November 30, 2006 from .</ref> He suggests that the evidence is still available: "You yourselves have the account of the world-portent still in your archives."<ref></ref> | |||

| {{Gospel Jesus}} | |||

| A number of accounts in ] build on the synoptic accounts. In the '']'', from the second century AD, as one writer puts it, "accompanying miracles become more fabulous and the apocalyptic portents are more vivid".{{sfnp|Foster|2009|p=97}} In this version the darkness which covers the whole of Judaea leads people to go about with lamps believing it to be night.{{sfnp|Roberts|Donaldson|Coxe|1896|loc=Volume IX, 5:15, p. 4}} The fourth century '']'' describes how Pilate and his wife are disturbed by a report of what had happened, and the Judeans he has summoned tell him it was an ordinary solar eclipse.{{sfnp|Barnstone|2005|pp=351, 368, 374, 378-379, 419}} Another text from the fourth century, the purported ''Report of Pontius Pilate to Tiberius'' claimed the darkness had started at the sixth hour, covered the whole world and, during the subsequent evening, the full moon resembled blood for the entire night.{{sfnp|Roberts|Donaldson|Coxe|1896|loc=Volume VIII, , pp. 462-463}} In a fifth- or sixth-century text by ], the author claims to have observed a solar eclipse from ] at the time of the crucifixion.{{sfnp|Parker|1897|pp=148–149, 182–183}} | |||

| ===Ancient historians=== | |||

| The early historian and theologian, ] (between 340 and 345 – 410), in his expanded work of Eusebius’ ''Ecclesiastical History'', includes a part of the defense given to ] by ], shortly before he suffered martyrdom in 312.<ref>Rufinus, ''Ecclesiastical History'', Book 9, Chapter 6</ref> Lucian, like Tertullian, was also convinced that an account of the darkness that accompanied the crucifixion could be found among Roman records. ] recorded Lucian's corresponding statement given to Maximinus as, “Search your writings and you shall find that, in Pilate’s time, when Christ suffered, the sun was suddenly withdrawn and a darkness followed.” <ref>Ussher, J., & Pierce, L. (Trans.)(2007). ''Annals of the World'' . Green Forest, AR: New Leaf Publishing Group. ISBN 0-89051-510-7</ref> | |||

| There are no original references to this darkness outside of the New Testament; the only possible contemporary reference may have existed in a work by the chronicler ]. In the ninth century AD, the Byzantine historian ] quoted from the third-century Christian historian ], who remarked that "Thallos dismisses this darkness as a solar eclipse".<ref name=Africanus>], ''Chronography'', .</ref> It is not known when Thallus lived, and it is unclear whether he himself made any reference to the crucifixion.{{sfnp|Alexander|2005|p=225}} ], in his '']'', told the story of the crucifixion darkness and suggested that the evidence must still be held in the Roman archives.{{sfnp|Roberts|Donaldson|Coxe|1896|loc=Volume III, "The Apology" , pp. 34-36}} | |||

| Until the Enlightenment era, the crucifixion darkness story was often used by Christian apologists, because they believed it was a rare example of the biblical account being supported by non-Christian sources. When the pagan critic ] claimed that Jesus could hardly be a God because he had performed no great deeds, the third century AD Christian commentator ] responded, in '']'', by recounting the darkness, earthquake and opening of tombs. As proof that the incident had happened, he referred to a description by ] of an eclipse accompanied by earthquakes during the reign of Tiberius (probably that of 29 AD).{{sfnp|Roberts|Donaldson|Coxe|1896|loc=Volume IV, "Contra Celsum", p. 441}} | |||

| The next prominent Christian historian after Eusebius, ] (375 – 418), wrote c. 417 that Jesus "voluntarily gave himself over to the Passion but through the impiety of the Jews, was apprehended and nailed to the cross, as a very great earthquake took place throughout the world, rocks upon mountains were split, and a great many parts of the largest cities fell by this extraordinary violence. On the same day also, at the sixth hour of the day, the Sun was entirely obscured and a loathsome night suddenly overshadowed the land, as it was said, ‘an impious age feared eternal night.’ Moreover, it was quite clear that neither the Moon nor the clouds stood in the way of the light of the Sun, so that it is reported that on that day the Moon, being fourteen days old, with the entire region of the heavens thrown in between, was farthest from the sight of the Sun, and the stars throughout the entire sky shone, then in the hours of the day or rather in that terrible night. To this, not only the authority of the Holy Gospels attest, but even some books of the Greeks." <ref>Orosius, P. (A.D. 417). ''The Seven Books of History Against the Pagans.'' In, R. J. Deferrari (Trans.) & H. Dressler, et al. (Vol. Eds.) (1964). ''The Fathers of the Church'' – Vol. 50 (1st short-run printing 2001, pp. 291-292). Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press. ISBN 978-0-8132-1310-1.</ref> | |||

| In his ''Commentary on Matthew'', however, Origen offered a different approach. Answering criticisms that there was no mention of this incident in any of the many non-Christian sources, he insisted that it was local to Palestine, and therefore would have gone unnoticed outside. To suggestions that it was merely an eclipse, he pointed out that, since the crucifixion took place at Passover, at the time of the full moon, an eclipse could not have taken place. Instead, and drawing only on the accounts given in Matthew and Mark, which make no mention of the sun, he suggested other explanations, such as heavy clouds.{{sfnp|Allison|2005|pp=88-89}} | |||

| ==Dating the crucifixion== | |||

| {{See also|Chronology of Jesus#year of death estimates}} | |||

| Astronomical determinations of the date of the crucifixion have been derived from calculating the dates when the crescent of the new moon would be first visible from Jerusalem, which was used by the Jews to mark the first day of a lunar month, for example Nisan 1. Popular estimates have been April 7, 30 AD, April 3, 33 AD, and April 23, 34 AD.<ref name="Schaefer">Schaefer, B. E. (1990). Lunar visibility and the crucifixion. ''Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society'', '''31''', 53-67.</ref><ref>Pratt, J. P. (1991). Newton's date for the crucifixion . ''Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society'', '''32''', 301-304.</ref> | |||

| ==Explanations== | |||

| Extra-biblical records have been incorporated with the determinations of the year of the crucifixion. Eusebius connected the solar darkening with the 18th year of ]’ reign and the earthquakes to the year of the crucifixion of Jesus Christ. Since Tiberius (42 BC – 37 AD) ascended the throne in 14 AD, the 18th year of his reign would have occurred in 32 AD, or, using Jewish ecclesiastical reckoning, between Spring of 32 and Spring of 33.<ref name="Humphreys">], Colin J., and W. G. Waddington, "Dating the Crucifixion," Nature 306 (December 22/29, 1983), pp. 743-46. </ref> Also, the darkening recorded by ] yielded 32 or 33 AD. The fourth year of the 202nd ] ran from summer of 32 to summer of 33 AD because the first Olympiad occurred in 776 BC. The Olympics were conducted every four years from 776 BC until 393 AD. | |||

| ===Miracle=== | |||

| Because it was known in ancient and medieval times that a solar eclipse could not take place during Passover (solar eclipses require a ] while Passover only takes place during a ]) it was considered a miraculous sign rather than a naturally occurring event.{{sfnp|Chambers|1899|pp=129-130}} The astronomer ] wrote, in his ], "the eclipse was not natural, but, rather, miraculous and contrary to nature".{{sfnp|Bartlett|2008|pp=68-69}} | |||

| ===Literary creation=== | |||

| ==Crucifixion eclipse models== | |||

| A common view in modern scholarship is that the account in the synoptic gospels is a literary creation of the gospel writers - ] describes it as a fabrication by the author of the ]{{sfnp|Mack|1988|p=296|ps=, 'This is the earliest account there is about the crucifixion of Jesus. It is a Markan fabrication'}} - intended to heighten the importance of what they saw as a theologically significant event: | |||

| <blockquote>"It is probable that, without any factual basis, darkness was added in order to wrap the cross in a rich symbol and/or assimilate Jesus to other worthies".{{sfnp|Davies|Allison|1997|p=623}}</blockquote> | |||

| ===Total solar eclipse=== | |||

| Records of solar blackouts exceeding a half hour have been attributed to total solar eclipses. For example, the T’ang Dynasty <ref>{{cite web|url=http://eclipse99.nasa.gov/pages/traditions_morechina.htm |title=NASA - Eclipse 99 - Eclipses Through Traditions and Cultures |publisher=Eclipse99.nasa.gov |date= |accessdate=2011-02-28}}</ref> and ]’s accounts of the hour long solar darkness of 879 were attributed to the total solar eclipse of October 29, 878.<ref>{{cite web|author=Espenak |url=http://www.mreclipse.com/Special/quotes2.html |title=Eclipse Quotations - Part II |publisher=Mreclipse.com |date=1998-12-06 |accessdate=2011-02-28}}</ref> However, a solar eclipse could not have occurred on or near 14th of Nisan, because solar eclipses only occur during the new moon phase, and 14th of Nisan always corresponds to a full moon. | |||

| The image of darkness over the land would have been understood by ancient readers as a cosmic sign, a typical element in the description of the death of kings and other major figures by writers such as ], ], ], ] and ].{{sfnp|Garland|1999|p=264}} ] describes the darkness account as "part of the Jewish eschatological imagery of the day of the Lord. It is to be treated as a literary rather than historical phenomenon notwithstanding naive scientists and over-eager television documentary makers, tempted to interpret the account as a datable eclipse of the sun. They would be barking up the wrong tree".{{sfnp|Vermes|2005| pp=108-109}} | |||

| Solar eclipses are also too brief to account for the crucifixion darkness. The length of the crucifixion darkness described by biblical and extra-biblical sources was more than a full order of magnitude for the totality of solar eclipses. Seven minutes and 31.1 seconds has been the established maximum limit of solar eclipse totality.<ref>Meeus, J. (2003, December). The maximum possible duration of a total solar eclipse. ''Journal of the British Astronomical Association'', '''113'''(6), 343-348.</ref> The maximum duration of the total eclipse of November 3, 31 AD, was only one minute and four seconds. The maximum duration of the total eclipse of March 19, 33 AD, was only four minutes six seconds. Neither one had paths of totality passing near Jerusalem. Eclipses lasting at least six minutes, that were close to the crucifixion year, occurred on July 22, 27 AD, for a maximum duration of six minutes and thirty-one seconds and on August 1, 45 AD, for a maximum duration of six minutes and thirty seconds.<ref>{{cite web |title=Five Millennium Catalog of Solar Eclipses |publisher=] |url=http://sunearth.gsfc.nasa.gov/eclipse/SEcat5/SE0001-0100.html |accessdate=2007-09-28}}</ref> | |||

| ===Naturalistic explanations=== | |||

| Astronomer Mark Kidger compared the apocryphal ] passage with historical eclipses.<ref name="Kidger">Kidger, M. (1999). ''The Star of Bethlehem: An astronomer’s View'' (pp. 68-72). Princeton, N. J: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-05823-7.</ref> He indicated the total eclipse of November 24, 29 AD had the greatest geographical proximity to the site of the crucifixion. He determined its path of totality had passed slightly north of Jerusalem at 11:05 AM (see the NASA diagram of the path of totality for that eclipse <ref>http://eclipse.gsfc.nasa.gov/SEhistory/SEplot/SE0029Nov24T.pdf</ref>) Kidger indicated the maximum level of darkness at totality was just 95% for the eclipsed over Jerusalem. His research indicated that level of darkness would have been unnoticeable for people outdoors. His calculations indicated the eclipse had been total in Nazareth and Galilee for one minute and forty-nine seconds. Kidger concluded the population in Jerusalem lacked the necessity and the time to light their lamps for that total solar eclipse.<ref name="Kidger"/> Their behavior, as described in the Apocryphal Gospel of Peter, had been caused by a considerably longer period of darkness. | |||

| A solar eclipse could not have occurred on or near the Passover, when Jesus was crucified, because solar eclipses only occur during the new moon phase, and Passover always corresponds to a full moon. Solar eclipses are also too brief to account for the darkness described. The biblical accounts refer to a period of three hours. However, the maximum possible duration of a total solar eclipse is seven minutes and 31.1 seconds.{{sfnp|Meeus|2003}} A total eclipse on 24 November 29 AD was visible slightly north of Jerusalem at 11:05 AM.{{sfn|Espenak|loc="Total Solar Eclipse of 0029 Nov 24"}} The period of totality in Nazareth and Galilee was one minute and forty-nine seconds, and the level of darkness would have been unnoticeable for people outdoors.{{sfnp|Kidger|1999|pp=68-72}} | |||

| In 1983, ] and W. G. Waddington, who had used astronomical methods to calculate the crucifixion date crucifixion as 3 April 33 AD,{{sfnp|Humphreys|Waddington|1983}} argued that the darkness could be accounted for by a partial lunar eclipse that had taken place on that day.{{sfnp|Humphreys|Waddington|1985}} Astronomer ], on the other hand, pointed out that the eclipse would not have been visible during daylight hours.{{sfnp|Schaefer|1990}}{{sfnp|Schaefer|1991}} Humphreys and Waddington speculated that the reference in the Luke Gospel to a solar eclipse must have been the result of a scribe wrongly amending the text, a claim historian ] describes as 'indefensible'.{{sfnp|Henige|2005|p=150}} | |||

| According to Pollata, the Greek word, ''ΕΓΕΝΕΤΟ'' (it-became),<ref>''The Greek Elements'' (1971). Saugus, CA: Concordant Publishing Concern, (page 37).</ref> indicates the onslaught of darkness had transpired too rapidly for a solar eclipse.<ref>Pallotta, C. (1995). ''The Crucifixion Eclipse'' (pages 2, 4). Brooklyn, NY: Marian Media Apostolate. He sites Merk, A. S. J. (Ed.) (1951). ''Novum Testamentum Graece Et Latine'', (pages 104, 181, 298, 307). Romae: Sumptibus Pontificii Instituti Biblici. </ref> It takes approximately an hour for the darkness to reach the beginning of totality.<ref>Brewer, B. (1991). ''Eclipse'' (Second Edition)(page 33). Seattle, Washington: Earth View. ISBN 0-932898-91-2.</ref> The Greek phrase, ''ΣΚΟΤΟΣ ΕΓΕΝΕΤΟ'' (darkness came about) appears in the crucifixion accounts of the ], ], and the ].<ref>''The Concordant Version of the Sacred Scriptures'' (1955). Saugus, CA: Concordant Publishing Concern, (pages 27, 118, 177, 274).</ref> Most English versions of the Bible do not describe a sudden darkening. | |||

| Some |

Some writers have explained the crucifixion darkness in terms of sunstorms, heavy cloud cover or the aftermath of a volcanic eruption.{{sfnp|Brown|1994|p=1040}} Another possible natural explanation is a ] dust storm that tends to occur from March to May.{{sfnp|Humphreys|2011|p=84}} | ||

| ==Interpretations== | |||

| Jesus' crucifixion took place around Passover, the middle of the lunar month and the time of a full moon. Solar eclipses naturally take place only at the time of the new moon. For this reason, medieval commentators viewed the darkness as a miraculous event rather than a natural one. ]s' and Waddington's reconstruction of the Jewish calendar, associating the crucifixion with a ] rather than a ], has been used to infer the date of the crucifixion.<ref name=HumWadJASA>Colin J. Humphreys and W. G. Waddington, ''The Date of the Crucifixion'' Journal of the American Scientific Affiliation 37 (March 1985)</ref> | |||

| Some commentators have noted the part this sequence plays in the gospel's literary narrative. One writer, describing the author of the Mark Gospel as operating here "at the peak of his rhetorical and theological powers", suggests that the darkness is a deliberate inversion of the ].{{sfnp|Black|2005|p=42}} The gospel's earlier discourse of Jesus about a future tribulation, {{bibleref2|Mark|13:24|NRSV}} where he speaks of the sun being darkened, can be seen as a foreshadowing of this scene.{{sfnp|Healy|2008|p=319}} Striking details such as the darkening of the sky and the tearing of the temple veil may be a way of focusing the reader away from the shame and humiliation of the crucifixion: "it is clear that Jesus is not a humiliated criminal but a man of great significance. His death is therefore not a sign of his weakness but of his power".{{sfnp|Winn|2008|p=133}} | |||

| Another approach has been to consider the theological meaning of the event: for instance, that "the whole universe joins in mourning the cruel death of the Son of God".{{sfnp|Donahue|2002|pp=451-452}} Others have seen it as a sign of God's judgement on the Jewish people, sometimes connecting it with the destruction of the city of Jerusalem in the year 70 AD; or as symbolising shame, fear or the mental suffering of Jesus.{{sfnp|Allison|2005|pp=97-102}} | |||

| ===Lunar eclipse=== | |||

| ] and Waddington of ] reconstructed the Jewish calendar in the first century AD and arrived at the conclusion that Friday April 3 33AD was the date of the Crucifixion.<ref name=Humphreys/> Humphreys and Waddington went further and also reconstructed the scenario for a lunar eclipse on that day.<ref name=HumWadJASA/> They concluded that: | |||

| Many writers have adopted an ] approach, looking at earlier texts from which the author of the Mark Gospel has probably drawn. In particular, parallels have often been noted between the darkness and the prediction in the ] of an earthquake in the reign of King ]: "On that day, says the Lord God, I will make the sun go down at noon, and darken the earth in broad daylight" ({{bibleref2|Amos|8:8-9|NRSV}}). Particularly in connection with this reference, read as a prophecy of the future, the darkness can be seen as portending the ].{{sfnp|Allison|2005|pp=100-101}} | |||

| <blockquote> | |||

| "This eclipse was visible from Jerusalem at moonrise. .... The start of the eclipse was invisible from Jerusalem, being below the horizon. The eclipse began at 3:40pm and reached a maximum at 5:15pm, with 60% of the moon eclipsed. This was also below the horizon from Jerusalem. The moon rose above the horizon, and was first visible from Jerusalem at about 6:20pm (the start of the Jewish Sabbath and also the start of Passover day in A.D. 33) with about 20% of its disc in the umbra of the earth's shadow and the remainder in the penumbra. The eclipse finished some thirty minutes later at 6:50pm." | |||

| </blockquote> | |||

| Another likely literary source is {{Bibleverse-lb||Exodus|10:22|HE}}, in which Egypt is covered by darkness for three days. It has been suggested that the author of the Matthew Gospel changed the Marcan text slightly to more closely match this source.{{sfnp|Allison|2005|pp=182-83}} Commentators have also drawn comparisons with {{Bibleverse-lb||Genesis|1:2|HE}}, {{Bibleverse-lb||Jeremiah|15:9|HE}} and {{Bibleverse-lb||Zechariah|14:6-7|HE}}.{{sfnp|Allison|2005|pp=83-84}} | |||

| Moreover, their calculations showed that the 20% visible of the moon was positioned close to the top (i.e. leading edge) of the moon. The failure of any of the gospel accounts to refer to a lunar eclipse is, they assume, the result of a scribe wrongly amending a text to refer to a solar eclipse.<ref name="henige" />{{rp|150}} | |||

| ==Notes== | |||

| In ], the ] mentions in the context of a prophecy from ] that "the sun shall be turned into darkness, and the moon into blood"{{Bibleref2c|Acts|2:20}}. A "moon of blood" is a term also commonly used for a lunar eclipse because of the reddish color of the light refracted onto the moon through the Earth's atmosphere. Commentators are divided upon the exact nature of this statement by Saint Peter. The investigation by ] and Waddington concluded that ''the moon turned to blood'' statement probably refers to a lunar eclipse, and they showed that this interpretation is self-consistent and seems to confirm their conclusion that the crucifixion occurred on April 3, 33. However, they fail to address the preceding reference to the darkened sun.<ref name=HumWadJASA/> | |||

| {{reflist|3}} | |||

| ==References== | |||

| Using his approach to computing "celestial glare", Bradley Schaefer opposed the views of Humphreys and Waddington with respect to the visibility of the lunar eclipse, since his computations of celestial glare would not allow a visible lunar eclipse during the Crucifixion.<ref>Schaefer, B. E. (1990, March). Lunar visibility and the crucifixion. Royal Astronomical Society Quarterly Journal, 31(1), 53-67</ref><ref>Schaefer, B. E. (1991, July). Glare and celestial visibility. Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 103, 645-660.</ref> Ruggles also supported Schaefer's views.<ref>Ruggles, C. (1990, June). Archaeoastronomy – the Moon and the crucifixion. Nature, 345(6277), 669-670.</ref> However, using different computational mechanisms, based on the approach originally used by ], John Pratt and later Bradley Schaefer separately arrived at the same date for the Crucifixion as Humphreys and Waddington did based on the lunar eclipse approach, namely Friday, April 3 33 AD.<ref>Pratt, J. P. (1991). "Newton's Date for the Crucifixion". Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society 32 (3): 301–304. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/full/1991QJRAS..32..301P.</ref> | |||

| ;Books | |||

| {{refbegin|2}} | |||

| Gaskel argued a lunar eclipse during the day of the crucifixion could have received significant attention.<ref>Gaskel, C. M. (1993, December). Beyond visibility: The "Crucifixion eclipse" in the context of some other astronomical events of the times. ''Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society'', '''25''', 1334. 183rd AAS Meeting .</ref> | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Alexander |first=Loveday |editor1-first=Markus |editor1-last=Bockmuehl |editor1-link=Markus Bockmuehl |editor2-first=Donald A. |editor2-last=Hagner |title=The Written Gospel |publisher=Cambridge University Press |date=2005 |pages=222-237 |chapter=The Four among pagans |isbn=9781139445726 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=pAZxCMRztQ4C&pg=222 |ref=harv}} | |||

| *{{cite book |last=Allison |first=Dale C. |authorlink=Dale Allison |title=Studies in Matthew: Interpretation Past and Present |date=2005 |publisher =Baker Academic |isbn=9780801027918 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=jJgaNuDFxC4C |ref=harv}} | |||

| ===Miracle=== | |||

| *{{cite book |last=Barclay |first=William |authorlink=William Barclay (theologian) |title=The Gospel of John, Volume 1 |date=2001 |url=http://books.google.com/books?isbn=066422489X |isbn=9780664237806 |publisher=Westminster John Knox Press |ref=harv}} | |||

| Because it was known in medieval times that a solar eclipse could not take place during Passover (solar eclipses require a ] while Passover only takes place during a ]) it was considered a miraculous sign rather than a naturally occurring event.<ref>Chambers, G. F. (1908). ''The Story of Eclipses'' . New York: D. Appleton and Company.</ref> The astronomer ] wrote, in his ], "the eclipse was not natural, but, rather, miraculous and contrary to nature".<ref>Robert Bartlett, ''The Natural and the Supernatural in the Middle Ages'' (Cambridge University Press, 2008), page 68-69.</ref> | |||

| *{{cite book |editor-last=Barnstone |editor-first=Willis |editor-link=Willis Barnstone |title=The Other Bible |chapter=The Gospel of Nicodemus |date=2005 |publisher=HarperCollins |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=J9aKaGTOQDAC |isbn=9780060815981 |ref=harv}} | |||

| *{{cite book |last=Bartlett |first=Robert |authorlink=Robert Bartlett (historian) |title=The Natural and the Supernatural in the Middle Ages |date=2008 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=d9O3PtKMPNsC |isbn=9780521878326 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |ref=harv}} | |||

| ==Historicity== | |||

| *{{cite book |last=Black |first=C. Clifton |chapter=The Face is Familiar—I Just Can't Place It | |||

| During the nineteenth century, ] argued the biblical account was “too incredible and too ludicrous to merit serious notice.”<ref>Graves, K. (2007). ''The World’s Sixteen Crucified Saviors'' (pp. 113-115). Sioux Falls, South Dakota: NuVision Publications, LLC. ISBN 1-59547-780-2 {Original work published 1875}.</ref> His arguments stemmed from Gibbon’s comments on the silence of ] and ] about the crucifixion darkness. ] suggests the story was an invention originated by the author of the ].<ref>{{cite book |first=Burton L. |last=Mack |title=A Myth of Innocence: Mark and Christian origins |publisher=Fortress Press |year=1988 |isbn=0-8006-2549-8 |page=296 |quote=This is the earliest account there is about the crucifixion of Jesus. It is a Markan fabrication |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=fNSbW8hWRzwC&pg=PA296&vq=%22markan+fabrication%22&dq=darkness+crucifixion+myth&as_brr=3&sig=91wedXZa05AyWJBh1UHPTlHR4xE}} | |||

| |editor1-first=Beverley Roberts |editor1-last=Gaventa | |||

| </ref> | |||

| |editor2-first=Patrick D. |editor2-last=Miller |editor2-link=Patrick D. Miller | |||

| |title=The Ending of Mark and the Ends of God: Essays in Memory of Donald Harrisville Juel | |||

| The unusually long length of time the eclipse is supposed to have lasted has been used as an argument against its historicity, as has the lack of mention of the darkness in secular accounts and the ].<ref>Carrier (1999).</ref> One view is that the account in the synoptic gospels is a literary creation of the gospel writers, intended to heighten the sense of importance of a theologically significant event by taking a recent remembered event and applying it to the story of Jesus, just as eclipses were associated in accounts of other historical figures: | |||

| |date=2005 |publisher=Westminster John Knox Press |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=4O5Nile61gkC |isbn=9780664227395 |ref=harv}} | |||

| *{{cite book |last=Broadhead |first=Edwin Keith |title=Prophet, Son, Messiah: Narrative Form and Function in Mark |date=1994 |publisher=Continuum |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=lpkZdGEneEgC |isbn=9781850754763 |ref=harv}} | |||

| <blockquote>"It is probable that, without any factual basis, darkness was added in order to wrap the cross in a rich symbol and/or assimilate Jesus to other worthies".<ref>Davies, W. D, and Dale C. Allison, ''Matthew'' (Continuum International, 1997), page 623.</ref></blockquote> | |||

| *{{cite book |last=Brown |first=Raymond E. |author-link=Raymond E. Brown |title=The Death of the Messiah: a Commentary on the Passion Narratives in the Four Gospels |volume=Volume 2: From Gethsemane to the Grave |date=1994 |publisher=Doubleday |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=nfwfAAAAIAAJ |isbn=9780385193979 |series=] |ref=harv}} | |||

| *{{cite book |last=Chambers |first=George F. |title=The Story of Eclipses |date=1899 |url=http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/24222 |publisher=George Newnes, Ltd |ref=harv}} | |||

| In the ], the miraculous darkness accompanies the temple curtain being torn in two.<ref name = "ActJMark">] and the ]. ''The acts of Jesus: the search for the authentic deeds of Jesus.'' HarperSanFrancisco. 1998. "Mark," p. 51-161</ref> Some scholars question the historicity of the darkness in the Gospel of Mark and suggest that it may have been a literary creation intended to add drama.<ref name = "ActJMark"/><ref>Davies, W. D, and Dale C. Allison, ''A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Gospel According to Saing Matthew'', Volume III (Continuum International, 1997), page 623.</ref> To Mark's account, ] adds an earthquake and the resurrection of saints.<ref name = "ActJMatthew">] and the ]. ''The acts of Jesus: the search for the authentic deeds of Jesus.'' HarperSanFrancisco. 1998. "Matthew," p. 129-270</ref> The ] and the ''Seven Books of History Against the Pagans'' by ] refer specifically to the darkening of the sun.<ref name="henige">{{cite book | last=Henige | first=David P. | authorlink=David Henige | title=Historical evidence and argument | publisher=University of Wisconsin Press | isbn=978-0-299-21410-4 | year=2005}}</ref>{{rp|150}}<ref name = "ActJLuke">] and the ]. ''The acts of Jesus: the search for the authentic deeds of Jesus.'' HarperSanFrancisco. 1998. "Luke," p. 267-364</ref> The ] does not report any wondrous miracles associated with Jesus' crucifixion. | |||

| *{{cite book |last=Davies |first=Stevan L. |title=The Gospel of Thomas and Christian Wisdom |date=2004 |publisher=Bardic Press |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=4pifdYcwcbcC |isbn=9780974566740 |ref=harv}} | |||

| *{{cite book |last1=Davies |first1=William David |author-link1=William David Davies |last2=Allison |first2=Dale C. |title=Matthew: Volume 3 |date=1997 |publisher=Continuum |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=ZXIV2WOTVvMC |isbn=9780567085184 |ref=harv}} | |||

| ==Similar accounts of darkness== | |||

| *{{cite book |last=Donahue |first=John R. |title=The Gospel of Mark |date=2002 |publisher=Liturgical Press |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=xZAIsUZOwSQC |isbn=9780814658048 |ref=harv}} | |||

| Medieval accounts of large solar eclipses often described them as having very long duration, such as the one seen at ] in 1241, which was said to have lasted four hours; modern estimates suggest the period of total darkness lasted around 3 minutes and 30 seconds.<ref name="frs">{{cite book | last=Stephenson | first=F. R. | authorlink=F. R. Stephenson | title=Historical Eclipses and Earth's Rotation | publisher=Cambridge University Press | year=1997 | isbn=0-521-46194-4}}</ref>{{rp|402}}<ref name="sawyer">John F. A. Sawyer, "Joshua 10:12-14 and the solar eclipse of 30 September 1131 B.C.", ''Palestine Exploration Quarterly'' 1972</ref>{{rp|145}} A solar eclipse took place on 3 June 1239, visible from many parts of Europe. This was documented in ], ], ], ]{{Disambiguation needed|date=June 2011}}, ], ], ], ] and ]. Accounts of the duration vary considerably, from Cesena (one hour), to Coimbra (three hours) and Florence ('several hours').<ref name="frs" />{{rp|397-404}} However, an astronomer of the period, ], wrote an eyewitness report, which has been described as "the earliest known which gives a meaningful estimate of the duration of totality".<ref name="frs" />{{rp|398}} He described seeing the Sun "entirely covered for the space of time in which a man could walk fully 250 paces," which is consistent with the modern estimate of 5 minutes and 45 seconds.<ref>Restoro d'Arezzo, ''Delle composizione del mondo'' (1282) Book 1, Chapter 16, cited in Stephenson, F. R. (1997), ''Historical Eclipses and Earth’s Rotation'', (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997), page 398</ref><ref>See also John F. A. Sawyer, "Joshua 10:12-14 and the solar eclipse of 30 September 1131 B.C.", ''Palestine Exploration Quarterly'' 1972, page 145, who estimates the duration of totality at 5 minutes 50 seconds.</ref> | |||

| *{{cite book |last=Evans |first=Craig A. |authorlink=Craig A. Evans |title=Luke (Understanding the Bible Commentary Series) |date=2011 |publisher=Baker Books |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=mBkB2Beyi2QC |isbn=9781441236524 |ref=harv}} | |||

| *{{cite book |last=Foster |first=Paul |title=The Apocryphal Gospels: A Very Short Introduction |date=2009 |publisher=Oxford University Press |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=eER0zsCkFxUC |isbn=9780191578953 |ref=harv}} | |||

| Although total darkness in an eclipse never lasts more than a few minutes, it has frequently been recorded that observers perceive it as having lasted as much as two or three hours.<ref name="frs" />{{rp|385}}<ref name="sawyer" />{{rp|139}} The astronomer ] suggests that the long durations described in medieval, European accounts may have been influenced by the ] in the Synoptic Gospels; several texts closely resemble the wording of the Vulgate (Latin) gospel account.<ref name="frs" />{{rp|385}} He does not however apply that explanation to the other records of large solar eclipses from non-European countries.<ref name="frs" />{{rp|443-449}} | |||

| *{{cite book |last=Funk |first=Robert Walter |authorlink=Robert W. Funk |title=The acts of Jesus: the search for the authentic deeds of Jesus |date=1998 |publisher=HarperSanFrancisco |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=fg1CAQAAIAAJ |isbn=9780060629786 |ref=harv}} | |||

| *{{cite book |last=Garland |first=David E. |authorlink=David E. Garland |title=Reading Matthew: A Literary and Theological Commentary on the First Gospel |date=1999 |publisher =Smyth & Helwys Publishing |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=8CKue4eT83gC |isbn=9781573122740 |ref=harv}} | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| *{{cite book |last=Harrington |first=Daniel J. |authorlink=Daniel J. Harrington |title=The Gospel of Matthew |date=1991 |publisher=Liturgical Press |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=bNf13S3k2w0C |isbn=9780814658031 |ref=harv}} | |||

| *] | |||

| *{{cite book |last=Healy |first=Mary |title=The Gospel of Mark |date=2008 |publisher=Baker Academic |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=7gez6p3hl6YC |isbn=9780801035869 |ref=harv}} | |||

| *] | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Henige |first=David P. |authorlink=David Henige | title=Historical evidence and argument | publisher=University of Wisconsin Press | isbn=978-0-299-21410-4 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=rzlpAAAAMAAJ |year=2005 |ref=harv}} | |||

| *] | |||

| *{{cite book |last=Hooker |first=Morna |authorlink=Morna Hooker |title=The Gospel According to Saint Mark |date=1991 |publisher=Continuum |url=http://books.google.com/books?isbn=0826460399 |isbn=9780826460394 |ref=harv}} | |||

| *] | |||

| *{{cite book |last=Humphreys |first=Colin J. |author-link=Colin Humphreys |title=The Mystery of the Last Supper: Reconstructing the Final Days of Jesus |date=2011 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=BEy1BZRRAPQC |isbn=9781139496315 |ref=harv}} | |||

| *] | |||

| *{{cite book |last=Kidger |first=Mark |title=The Star of Bethlehem: An Astronomer's View |date=1999 |publisher=Princeton University Press |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=_ISv1gPQJV4C |isbn=9780691058238 |ref=harv}} | |||

| *] | |||

| *{{cite book |last=Loader |first=William |authorlink=Bill Loader |title=Jesus' Attitude Towards the Law: A Study of the Gospels |date=2002 |publisher=W.B. Eerdmans Pub |isbn=9780802849038 |ref=harv}} | |||

| *] | |||

| *{{cite book |last=Mack |first=Burton L. |author-link=Burton L. Mack |title=A Myth of Innocence: Mark and Christian Origins |date=1988 |publisher=Fortress Press |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=fNSbW8hWRzwC |isbn=9781451404661 |ref=harv}} | |||

| *{{cite book |last=Parker |first=John |title=The Works of Dionysius the Arepagite |chapter=Letter VII. Section II. To Polycarp--Hierarch. & Letter XI. Dionysius to Apollophanes, Philosopher |year=1897 |publisher=James Parker and Co. |location=London |isbn=9781440092398 |ref=harv}} | |||

| ==Notes== | |||

| *{{cite book |editor1-last=Roberts |editor1-first=Alexander |editor1-link=Alexander Roberts |editor2-first=James |editor2-last=Donaldson |editor2-link=James Donaldson (classical scholar) |editor3-first=Arthur Cleveland |editor3-last=Coxe |editor3-link=Arthur Cleveland Coxe |title=] |date=1896 |publisher=] |ref=harv}} | |||

| {{reflist|2}} | |||

| *{{cite book |last=Vermes |first=Géza |authorlink=Géza Vermes |title=The Passion |date=2005 |publisher=Penguin |isbn=9780141021324 |ref=harv}} | |||

| *{{cite book |last=Winn |first=Adam |title=The Purpose of Mark's Gospel: An Early Christian Response to Roman Imperial Propaganda |date=2008 |publisher=Mohr Siebeck |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=XCPQ1NqyP6IC |isbn=9783161496356 |ref=harv}} | |||

| *{{cite book |last=Witherington |first=Ben |authorlink=Ben Witherington III |title=The Gospel of Mark: A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary |date=2001 |publisher=Eerdmans Publishing |url=http://books.google.com/books?isbn=0802845037 |isbn=9780802845030 |ref=harv}} | |||

| *{{cite book |last=Yieh |first=John Yueh-Han |title=One Teacher: Jesus' Teaching Role in Matthew's Gospel Report |date=2004 |publisher=Walter de Gruyter |url=http://books.google.com/books?id= |isbn=9783110913330 |ref=harv}} | |||

| {{refend}} | |||

| ;Journal articles | |||

| ==Further reading== | |||

| {{refbegin|2}} | |||

| *Carrier, R. (1999). (1999). Retrieved May 24, 2002. | |||

| *{{Cite doi|10.1038/306743a0}} | |||

| *DeLashmutt, G. (2005). Chapter 19 (Matthew 27:45-54) The events accompanying Jesus’ crucifixion. . Xenos Christian Fellowship. Retrieved on March 10, 2005. | |||

| *{{cite journal |last1=Humphreys |first1=Colin J. |last2=Waddington |first2=W. Graeme |date=March 1985 |title=The Date of the Crucifixion |url=http://www.asa3.org/ASA/PSCF/1985/JASA3-85Humphreys.html |journal=Journal of the American Scientific Affiliation |publisher= |volume=37 |pages=2-10 |ref=harv}} | |||

| *James, M. R., (Trans.). (1924). The gospel of Nicodemus, or acts of Pilate. In ''The apocryphal New Testament''. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Retrieved May 28, 2002 from . | |||

| *{{cite journal |last=Meeus |first=Jean |author-link=Jean Meeus |date=December 2003 |title=The maximum possible duration of a total solar eclipse |url=http://adsabs.harvard.edu/full/2003JBAA..113..343M |journal=Journal of the British Astronomical Association |volume=113 |issue=6 |pages=343-348 |ref=harv |accessdate=3 November 2013}} | |||

| *Lohmann, K. J., Hester, J. T., & Lohmann, C. M. F., (1999). ''Ethology Ecology & Evolution'', '''11''', 1-23. | |||

| *{{cite journal |last=Schaefer |first=Bradley E. |author-link=Bradley E. Schaefer |date=March 1990 |title=Lunar Visibility and the Crucifixion |url=http://adsabs.harvard.edu/full/1990QJRAS..31...53S |journal=Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society |volume=31 |issue=1 |pages=53-67 |ref=harv}} | |||

| *Stewart, D. (n.d.). ''What Everyone Needs to Know About the Bible''. Orange, CA: Dart Press. Retrieved May 28, 2002 from . | |||

| *{{Cite doi|10.1086/132865}} | |||

| *Thiede, C. P., & d'Ancona, M. (1996). ''The Jesus Papyrus'' (pp. 59–64, 101-127, 135-137). New York: Doubleday, a division of Random House, Inc. ISBN 0-385-48898-X. | |||

| {{refend}} | |||

| ;Web sites | |||

| {{Solar eclipses}} | |||

| {{refbegin}} | |||

| *{{cite web |url=http://eclipse.gsfc.nasa.gov/SEhistory/SEplot/SE0029Nov24T.pdf |title=Total Solar Eclipse of 0029 Nov 24 |last1=Espenak |first1=Fred |authorlink1=Fred Espenak |website=NASA Eclipse Web Site |publisher=] |accessdate=3 November 2013 |ref=harv}} | |||

| {{refend}} | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Crucifixion Darkness |

{{DEFAULTSORT:Crucifixion Darkness}} | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

Revision as of 20:37, 4 November 2013

According to the Christian synoptic gospels, on the day Jesus was crucified there was a period of darkness in the afternoon for three hours. Although ancient and medieval writers treated this as a miracle, modern writers tend to view it either as a literary invention or a natural phenomenon, such as a solar eclipse. Some writers, interpreting it as an eclipse, have sought to use it as a way of establishing the date of Jesus' crucifixion.

Biblical account

- See also Chronology of Jesus

The original biblical reference is in the Gospel of Mark, usually dated around the year 70 AD. In its account of the death of Jesus, on the eve of Passover, it says that after Jesus was crucified at nine in the morning, darkness fell over all the land, or all the world (Template:Lang-grc-gre can mean either) from around noon ("the sixth hour") until 3 o'clock ("the ninth hour"):

When it was noon, darkness came over the whole land until three in the afternoon.

— Mark 15:33

The account adds a detail that follows immediately on the death of Jesus:

And the curtain of the temple was torn in two, from top to bottom.

— Mark 15:38

The Gospel of Matthew, written around the year 85 or 90 AD, and using Mark as a source, has an almost identical wording:

From noon on, darkness came over the whole land until three in the afternoon.

— Matthew 27:45

The Matthew account adds some dramatic details, including an earthquake and the raising of the dead, which were stock motifs from Jewish apocalyptic literature:

(…) At that moment the curtain of the temple was torn in two, from top to bottom. The earth shook, and the rocks were split. The tombs also were opened, and many bodies of the saints who had fallen asleep were raised. After his resurrection they came out of the tombs and entered the holy city and appeared to many. Now when the centurion and those with him, who were keeping watch over Jesus, saw the earthquake and what took place, they were terrified and said, “Truly this man was God’s Son!”

— 27:51–54

The Gospel of Luke, written around the year 90 AD and also using Mark as a source, has none of the details added in the Matthew version, moves the tearing of the temple veil to before the death of Jesus and includes an explanation that the sun was darkened, appearing to explain it as an eclipse:

It was now about noon, and darkness came over the whole land until three in the afternoon, while the sun’s light failed ; and the curtain of the temple was torn in two.

— Luke 23:44–45

The account given in the Gospel of John is different: it takes place on the day of Passover, the crucifixion does not take place until after noon, and there is no mention of darkness, the tearing of the veil, or the raising of the dead.

Later versions

Apocryphal writers

| Events in the |

| Life of Jesus according to the canonical gospels |

|---|

|

| Early life |

| Ministry |

| Passion |

| Resurrection |

| In rest of the NT |

|

Portals: |

A number of accounts in apocryphal literature build on the synoptic accounts. In the Gospel of Peter, from the second century AD, as one writer puts it, "accompanying miracles become more fabulous and the apocalyptic portents are more vivid". In this version the darkness which covers the whole of Judaea leads people to go about with lamps believing it to be night. The fourth century Gospel of Nicodemus describes how Pilate and his wife are disturbed by a report of what had happened, and the Judeans he has summoned tell him it was an ordinary solar eclipse. Another text from the fourth century, the purported Report of Pontius Pilate to Tiberius claimed the darkness had started at the sixth hour, covered the whole world and, during the subsequent evening, the full moon resembled blood for the entire night. In a fifth- or sixth-century text by Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, the author claims to have observed a solar eclipse from Heliopolis at the time of the crucifixion.

Ancient historians

There are no original references to this darkness outside of the New Testament; the only possible contemporary reference may have existed in a work by the chronicler Thallus. In the ninth century AD, the Byzantine historian George Syncellus quoted from the third-century Christian historian Sextus Julius Africanus, who remarked that "Thallos dismisses this darkness as a solar eclipse". It is not known when Thallus lived, and it is unclear whether he himself made any reference to the crucifixion. Tertullian, in his Apologeticus, told the story of the crucifixion darkness and suggested that the evidence must still be held in the Roman archives.

Until the Enlightenment era, the crucifixion darkness story was often used by Christian apologists, because they believed it was a rare example of the biblical account being supported by non-Christian sources. When the pagan critic Celsus claimed that Jesus could hardly be a God because he had performed no great deeds, the third century AD Christian commentator Origen responded, in Against Celsus, by recounting the darkness, earthquake and opening of tombs. As proof that the incident had happened, he referred to a description by Phlegon of Tralles of an eclipse accompanied by earthquakes during the reign of Tiberius (probably that of 29 AD).

In his Commentary on Matthew, however, Origen offered a different approach. Answering criticisms that there was no mention of this incident in any of the many non-Christian sources, he insisted that it was local to Palestine, and therefore would have gone unnoticed outside. To suggestions that it was merely an eclipse, he pointed out that, since the crucifixion took place at Passover, at the time of the full moon, an eclipse could not have taken place. Instead, and drawing only on the accounts given in Matthew and Mark, which make no mention of the sun, he suggested other explanations, such as heavy clouds.

Explanations

Miracle

Because it was known in ancient and medieval times that a solar eclipse could not take place during Passover (solar eclipses require a new moon while Passover only takes place during a full moon) it was considered a miraculous sign rather than a naturally occurring event. The astronomer Johannes de Sacrobosco wrote, in his The Sphere of the World, "the eclipse was not natural, but, rather, miraculous and contrary to nature".

Literary creation

A common view in modern scholarship is that the account in the synoptic gospels is a literary creation of the gospel writers - Burton Mack describes it as a fabrication by the author of the Gospel of Mark - intended to heighten the importance of what they saw as a theologically significant event:

"It is probable that, without any factual basis, darkness was added in order to wrap the cross in a rich symbol and/or assimilate Jesus to other worthies".

The image of darkness over the land would have been understood by ancient readers as a cosmic sign, a typical element in the description of the death of kings and other major figures by writers such as Philo, Dio Cassius, Virgil, Plutarch and Josephus. Géza Vermes describes the darkness account as "part of the Jewish eschatological imagery of the day of the Lord. It is to be treated as a literary rather than historical phenomenon notwithstanding naive scientists and over-eager television documentary makers, tempted to interpret the account as a datable eclipse of the sun. They would be barking up the wrong tree".

Naturalistic explanations

A solar eclipse could not have occurred on or near the Passover, when Jesus was crucified, because solar eclipses only occur during the new moon phase, and Passover always corresponds to a full moon. Solar eclipses are also too brief to account for the darkness described. The biblical accounts refer to a period of three hours. However, the maximum possible duration of a total solar eclipse is seven minutes and 31.1 seconds. A total eclipse on 24 November 29 AD was visible slightly north of Jerusalem at 11:05 AM. The period of totality in Nazareth and Galilee was one minute and forty-nine seconds, and the level of darkness would have been unnoticeable for people outdoors.

In 1983, Colin Humphreys and W. G. Waddington, who had used astronomical methods to calculate the crucifixion date crucifixion as 3 April 33 AD, argued that the darkness could be accounted for by a partial lunar eclipse that had taken place on that day. Astronomer Bradley E. Schaefer, on the other hand, pointed out that the eclipse would not have been visible during daylight hours. Humphreys and Waddington speculated that the reference in the Luke Gospel to a solar eclipse must have been the result of a scribe wrongly amending the text, a claim historian David Henige describes as 'indefensible'.

Some writers have explained the crucifixion darkness in terms of sunstorms, heavy cloud cover or the aftermath of a volcanic eruption. Another possible natural explanation is a khamsin dust storm that tends to occur from March to May.

Interpretations

Some commentators have noted the part this sequence plays in the gospel's literary narrative. One writer, describing the author of the Mark Gospel as operating here "at the peak of his rhetorical and theological powers", suggests that the darkness is a deliberate inversion of the transfiguration. The gospel's earlier discourse of Jesus about a future tribulation, Mark 13:24 where he speaks of the sun being darkened, can be seen as a foreshadowing of this scene. Striking details such as the darkening of the sky and the tearing of the temple veil may be a way of focusing the reader away from the shame and humiliation of the crucifixion: "it is clear that Jesus is not a humiliated criminal but a man of great significance. His death is therefore not a sign of his weakness but of his power".

Another approach has been to consider the theological meaning of the event: for instance, that "the whole universe joins in mourning the cruel death of the Son of God". Others have seen it as a sign of God's judgement on the Jewish people, sometimes connecting it with the destruction of the city of Jerusalem in the year 70 AD; or as symbolising shame, fear or the mental suffering of Jesus.

Many writers have adopted an intertextual approach, looking at earlier texts from which the author of the Mark Gospel has probably drawn. In particular, parallels have often been noted between the darkness and the prediction in the Book of Amos of an earthquake in the reign of King Uzziah of Judah: "On that day, says the Lord God, I will make the sun go down at noon, and darken the earth in broad daylight" (Amos 8:8–9). Particularly in connection with this reference, read as a prophecy of the future, the darkness can be seen as portending the end times.

Another likely literary source is Exodus 10:22, in which Egypt is covered by darkness for three days. It has been suggested that the author of the Matthew Gospel changed the Marcan text slightly to more closely match this source. Commentators have also drawn comparisons with Genesis 1:2, Jeremiah 15:9 and Zechariah 14:6–7.

Notes

- Witherington (2001), p. 31: 'from 66 to 70, and probably closer to the latter'

- Hooker (1991), p. 8: 'the Gospel is usually dated between AD 65 and 75.'

- Harrington (1991), p. 8.

- Yieh (2004), p. 65.

- Funk (1998), pp. 129–270, "Matthew".

- Davies (2004), p. xii.

- Evans (2011), p. 308.

- ^ Henige (2005), p. 150.

- Funk (1998), pp. 267–364, "Luke".

- Loader (2002), p. 356.

- Barclay (2001), p. 340.

- Broadhead (1994), p. 196.

- Foster (2009), p. 97.

- Roberts, Donaldson & Coxe (1896), Volume IX, "The Gospel of Peter" 5:15, p. 4.

- Barnstone (2005), pp. 351, 368, 374, 378–379, 419.

- Roberts, Donaldson & Coxe (1896), Volume VIII, "The Report of Pontius Pilate", pp. 462-463.

- Parker (1897), pp. 148–149, 182–183.

- George Syncellus, Chronography, chapter 391.

- Alexander (2005), p. 225.

- Roberts, Donaldson & Coxe (1896), Volume III, "The Apology" chapter 21, pp. 34-36.

- Roberts, Donaldson & Coxe (1896), Volume IV, "Contra Celsum", Book II, chapter 23 p. 441.

- Allison (2005), pp. 88–89.

- Chambers (1899), pp. 129–130.

- Bartlett (2008), pp. 68–69.

- Mack (1988), p. 296, 'This is the earliest account there is about the crucifixion of Jesus. It is a Markan fabrication'

- Davies & Allison (1997), p. 623.

- Garland (1999), p. 264.

- Vermes (2005), pp. 108–109.

- Meeus (2003).

- Espenak, "Total Solar Eclipse of 0029 Nov 24".

- Kidger (1999), pp. 68–72.

- Humphreys & Waddington (1983). sfnp error: no target: CITEREFHumphreysWaddington1983 (help)

- Humphreys & Waddington (1985).

- Schaefer (1990).

- Schaefer (1991). sfnp error: no target: CITEREFSchaefer1991 (help)

- Brown (1994), p. 1040.

- Humphreys (2011), p. 84.

- Black (2005), p. 42.

- Healy (2008), p. 319.

- Winn (2008), p. 133.

- Donahue (2002), pp. 451–452.

- Allison (2005), pp. 97–102.

- Allison (2005), pp. 100–101.

- Allison (2005), pp. 182–83.

- Allison (2005), pp. 83–84.

References

- Books

- Alexander, Loveday (2005). "The Four among pagans". In Bockmuehl, Markus; Hagner, Donald A. (eds.). The Written Gospel. Cambridge University Press. pp. 222–237. ISBN 9781139445726.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Allison, Dale C. (2005). Studies in Matthew: Interpretation Past and Present. Baker Academic. ISBN 9780801027918.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Barclay, William (2001). The Gospel of John, Volume 1. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664237806.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Barnstone, Willis, ed. (2005). "The Gospel of Nicodemus". The Other Bible. HarperCollins. ISBN 9780060815981.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bartlett, Robert (2008). The Natural and the Supernatural in the Middle Ages. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521878326.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Black, C. Clifton (2005). "The Face is Familiar—I Just Can't Place It". In Gaventa, Beverley Roberts; Miller, Patrick D. (eds.). The Ending of Mark and the Ends of God: Essays in Memory of Donald Harrisville Juel. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664227395.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Broadhead, Edwin Keith (1994). Prophet, Son, Messiah: Narrative Form and Function in Mark. Continuum. ISBN 9781850754763.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Brown, Raymond E. (1994). The Death of the Messiah: a Commentary on the Passion Narratives in the Four Gospels. The Anchor Bible Reference Library. Vol. Volume 2: From Gethsemane to the Grave. Doubleday. ISBN 9780385193979.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Chambers, George F. (1899). The Story of Eclipses. George Newnes, Ltd.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Davies, Stevan L. (2004). The Gospel of Thomas and Christian Wisdom. Bardic Press. ISBN 9780974566740.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Davies, William David; Allison, Dale C. (1997). Matthew: Volume 3. Continuum. ISBN 9780567085184.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Donahue, John R. (2002). The Gospel of Mark. Liturgical Press. ISBN 9780814658048.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Evans, Craig A. (2011). Luke (Understanding the Bible Commentary Series). Baker Books. ISBN 9781441236524.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Foster, Paul (2009). The Apocryphal Gospels: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191578953.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Funk, Robert Walter (1998). The acts of Jesus: the search for the authentic deeds of Jesus. HarperSanFrancisco. ISBN 9780060629786.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Garland, David E. (1999). Reading Matthew: A Literary and Theological Commentary on the First Gospel. Smyth & Helwys Publishing. ISBN 9781573122740.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Harrington, Daniel J. (1991). The Gospel of Matthew. Liturgical Press. ISBN 9780814658031.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Healy, Mary (2008). The Gospel of Mark. Baker Academic. ISBN 9780801035869.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Henige, David P. (2005). Historical evidence and argument. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-21410-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hooker, Morna (1991). The Gospel According to Saint Mark. Continuum. ISBN 9780826460394.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Humphreys, Colin J. (2011). The Mystery of the Last Supper: Reconstructing the Final Days of Jesus. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139496315.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kidger, Mark (1999). The Star of Bethlehem: An Astronomer's View. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691058238.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Loader, William (2002). Jesus' Attitude Towards the Law: A Study of the Gospels. W.B. Eerdmans Pub. ISBN 9780802849038.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mack, Burton L. (1988). A Myth of Innocence: Mark and Christian Origins. Fortress Press. ISBN 9781451404661.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Parker, John (1897). "Letter VII. Section II. To Polycarp--Hierarch. & Letter XI. Dionysius to Apollophanes, Philosopher". The Works of Dionysius the Arepagite. London: James Parker and Co. ISBN 9781440092398.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Roberts, Alexander; Donaldson, James; Coxe, Arthur Cleveland, eds. (1896). The Ante-Nicene Fathers. T&T Clark.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Vermes, Géza (2005). The Passion. Penguin. ISBN 9780141021324.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Winn, Adam (2008). The Purpose of Mark's Gospel: An Early Christian Response to Roman Imperial Propaganda. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 9783161496356.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Witherington, Ben (2001). The Gospel of Mark: A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 9780802845030.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Yieh, John Yueh-Han (2004). One Teacher: Jesus' Teaching Role in Matthew's Gospel Report. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 9783110913330.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Journal articles

- Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1038/306743a0, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1038/306743a0instead. - Humphreys, Colin J.; Waddington, W. Graeme (March 1985). "The Date of the Crucifixion". Journal of the American Scientific Affiliation. 37: 2–10.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Meeus, Jean (December 2003). "The maximum possible duration of a total solar eclipse". Journal of the British Astronomical Association. 113 (6): 343–348. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Schaefer, Bradley E. (March 1990). "Lunar Visibility and the Crucifixion". Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society. 31 (1): 53–67.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1086/132865, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1086/132865instead.

- Web sites

- Espenak, Fred. "Total Solar Eclipse of 0029 Nov 24" (PDF). NASA Eclipse Web Site. NASA. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)