| Revision as of 23:36, 17 March 2014 view sourceXanzzibar (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers18,641 editsm Cut blank line← Previous edit | Revision as of 04:37, 19 March 2014 view source 109.65.29.57 (talk) re-organized the lead as per GAR discussion in the talk pageNext edit → | ||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

| }} | }} | ||

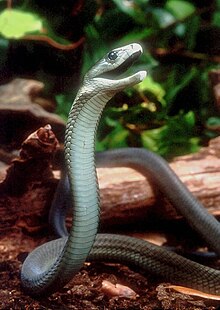

| The '''black mamba''' (''Dendroaspis polylepis''), also called the '''common black mamba''' or '''black-mouthed mamba''', is a highly ] of the genus ''Dendroaspis'' (]s), and is ] to ] Africa.<ref name=S&B95/> It was first described |

The '''black mamba''' (''Dendroaspis polylepis''), also called the '''common black mamba''' or '''black-mouthed mamba''', is a highly ] of the genus ''Dendroaspis'' (]s), and is ] to ] Africa.<ref name=S&B95/> It was first described by ] in 1864.<ref name="ITIS">{{ITIS |id=700483 |taxon=''Dendroaspis polylepis'' |accessdate=2 December 2011}}</ref><ref name="Database">{{cite web | url=http://reptile-database.reptarium.cz/species?genus=Dendroaspis&species=polylepis | title=Dendroaspis polylepis Günther, 1864 | publisher=Zoological Museum Hamburg | work=Reptile Database | accessdate=2 December 2011 | last=Uetz | first=P.}}</ref> | ||

| It is the fastest snake in the world, capable of moving at 4.32 to 5.4 metres per second (11–19 km/h, 10–12 mph) for short distances.<ref name=WR>{{cite book|last=Guinness World Records|title=Guinness World Records 2014 : Officially Amazing|year=2013|publisher=Guinness Publishing|isbn=978-1-897553-28-2}}</ref><ref name=Cpress>{{cite book|last=Capstone Press|title=Mambas|year=2005|publisher=Compass Point Books|isbn=978-0-7368-2137-7|page=13}}</ref> and it is the second-longest venomous snake in the world, after the ], averaging around {{convert|2.2|to|2.7|m|ft|abbr=on}} in length, <ref name=S&B95/> It has one of the most-potent ]s, and the venom is the most rapid-acting among all other snakes.<ref name=GreeneFogden/><ref name=Chippaux/> Depending on the nature of the bite, death time to humans can be anywhere from 20 minutes (commonly due to ] reaction) to 6–8 hours.<ref name=FitzSimons/> Without rapid and vigorous ] therapy, a bite from a black mamba is rapidly fatal almost 100% of the time.<ref name=Oshea05/><ref name="Territory"/><ref name='Davidson'/><ref name="R&R">{{cite book | title=Illustrated Handbook of Toxicology | publisher=Thieme | last=Reichl; Ritter | first=F-X; L. | year=2010 | edition=1st edition | pages=262–263 | isbn=978-3-13-126921-8}}</ref><ref>Krugerpark News (page 89). . ]. Retrieved April 11, 2014.</ref> Its combination of speed, unpredictable aggression, and potent venom make it an extremely dangerous species.<ref name=FitzSimons/><ref name=BB88/> Many experts regard the black mamba and the ] as the world's most-aggressive and dangerous snakes.<ref name="JW presentation00">{{cite AV media |people=Wasilewski, Joe|year=2011 |title=Wildlife Footage|medium=Motion picture|url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kr3oQ3lEQNY|accessdate=31 December 2013|location=Africa |publisher= Youtube}}</ref><ref name=Navy>{{cite book|last=Department of the Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery|title=Venomous Snakes of the World: A Manual for Use by U.S. Amphibious Forces|year=2013|publisher=Skyhorse Publishing|isbn=978-1-62087-623-7|page=93}}</ref><ref name='Snakes'/><ref name="AS Doc0.">{{cite AV media |people= Austin, Stevens |year=2001 |title=Austin Stevens: Snakemaster|trans_title=Search for the Black Mamba|url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=evS3XDcnOBQ&t=0m55s |accessdate=27 December 2013|time=0m55s |location=Namibia |publisher= Youtube}}</ref> Though the black mamba has a reputation for being very aggressive, like most snakes, it usually attempts to flee from humans unless threatened.<ref name=Oshea05/> | |||

| It has one of the most-potent ]s in the world, and the venom is the most rapid-acting among all other snakes,<ref name=GreeneFogden/><ref name=Chippaux/> and in cases of severe envenomation, it is capable of killing an adult human in as little as 20 minutes (commonly due to ] reaction). Two such cases have been documented in the medical literature. In one such case, an adult male was bitten on his right arm, just above the wrist by a black mamba which was estimated to be approximately {{convert|2.5|m|ft|abbr =on}} in length. The victim began to show signs of prominent neurotoxicity within minutes. At ten minutes post-envenomation, respiratory paralysis set in and 20 minutes post-envenomation the victim showed no signs of life and was deceased. Other cases of rapid death, within 30–60 minutes are relatively common among this species. However, depending on the nature of the bite, death time can be anywhere from 20 minutes to 6–8 hours.<ref name=FitzSimons/> Without rapid and vigorous ] therapy, a bite from a black mamba is rapidly fatal almost 100% of the time.<ref name=Oshea05/><ref name="Territory"/><ref name='Davidson'/><ref name="R&R">{{cite book | title=Illustrated Handbook of Toxicology | publisher=Thieme | last=Reichl; Ritter | first=F-X; L. | year=2010 | edition=1st edition | pages=262–263 | isbn=978-3-13-126921-8}}</ref><ref>Krugerpark News (page 89). . ]. Retrieved April 11, 2014.</ref> Many experts regard the black mamba and the ] as the world's most-aggressive and dangerous snakes.<ref name="JW presentation00">{{cite AV media |people=Wasilewski, Joe|year=2011 |title=Wildlife Footage|medium=Motion picture|url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kr3oQ3lEQNY|accessdate=31 December 2013|location=Africa |publisher= Youtube}}</ref><ref name=Navy>{{cite book|last=Department of the Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery|title=Venomous Snakes of the World: A Manual for Use by U.S. Amphibious Forces|year=2013|publisher=Skyhorse Publishing|isbn=978-1-62087-623-7|page=93}}</ref><ref name='Snakes'/><ref name="AS Doc0.">{{cite AV media |people= Austin, Stevens |year=2001 |title=Austin Stevens: Snakemaster|trans_title=Search for the Black Mamba|url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=evS3XDcnOBQ&t=0m55s |accessdate=27 December 2013|time=0m55s |location=Namibia |publisher= Youtube}}</ref> | |||

| ==Etymology== | ==Etymology== | ||

Revision as of 04:37, 19 March 2014

For other uses, see Black mamba (disambiguation).

| Black mamba | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Missing taxonomy template (fix): | Dendroaspis polylepis |

| Binomial name | |

| Dendroaspis polylepis Günther, 1864   In brown, D. polylepis may or may not occur here | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The black mamba (Dendroaspis polylepis), also called the common black mamba or black-mouthed mamba, is a highly venomous snake of the genus Dendroaspis (Mambas), and is endemic to sub-Saharan Africa. It was first described by Albert Günther in 1864.

It is the fastest snake in the world, capable of moving at 4.32 to 5.4 metres per second (11–19 km/h, 10–12 mph) for short distances. and it is the second-longest venomous snake in the world, after the king cobra, averaging around 2.2 to 2.7 m (7.2 to 8.9 ft) in length, It has one of the most-potent snake venoms, and the venom is the most rapid-acting among all other snakes. Depending on the nature of the bite, death time to humans can be anywhere from 20 minutes (commonly due to allergic reaction) to 6–8 hours. Without rapid and vigorous antivenom therapy, a bite from a black mamba is rapidly fatal almost 100% of the time. Its combination of speed, unpredictable aggression, and potent venom make it an extremely dangerous species. Many experts regard the black mamba and the coastal taipan as the world's most-aggressive and dangerous snakes. Though the black mamba has a reputation for being very aggressive, like most snakes, it usually attempts to flee from humans unless threatened.

Etymology

Dendroaspis polylepis has been the name of the black mamba's binomial name since 1864. The generic name, Dendroaspis, is derived from Ancient Greek words – Dendro, which means "tree", and aspis (ασπίς) or "asp", which' is understood to mean "shield", but it also designate "cobra" or simply "snake". In old text, aspis or asp was used to refer to Naja haje (in reference with the hood, like a shield). Thus, "Dendroaspis" literally means tree snake, which refers to the arboreal nature of most of the species within the genus. Schlegel used the name Dendroaspis, significant tree cobra. The specific name polylepis, is also derived from the Greek words - poly or polus, simply means "many" or "more" and lepis, also Greek in origin, means "scales", therefore "polylepis" literally means "many-scales". This refers to the black mambas size and the many scales it has. The name "black mamba" is given to the snake not because of its body colour but because of the ink-black colouration of the inside of its mouth, which it displays when threatened. This species is also commonly known as the common black mamba or black-mouthed mamba.

History

Evolution and taxonomy

The black mamba is classified under the genus Dendroaspis of the family Elapidae. The genus was described by the German ornithologist and herpetologist Hermann Schlegel in 1848. Initially, they were grouped within the Naja genus, but later removed due to the fact that they don't belong to the "cobra group". Parsimony analysis of phylogenetic relationships among elapines was found to be divided into two clades: coral snakes vs cobras, Bungarus, Elapsoidea, and Dendroaspis. The term cobra has traditionally been applied to the genera Aspidelaps, Boulengerina, Hemachatus, Naja, Ophiophagus, Paranaja, Pseudohaje, and Walterinnesia, a mostly African group generally characterized by the ability to flatten the neck into a hood when threatened. The African mambas (Dendroaspis) also have the ability to spread a hood when threatened, albeit more weakly than many members of the aforementioned group. Studies found significant bootstrap support for a core cobra group consisting of Naja, Boulengerina, Paranaja, Aspidelaps, Hemachatus, and Walterinnesia. Oddly, the Asian king cobra (Ophiophagus hannah), was not part of this clade, clustering instead with a group including Dendroaspis and Bungarus on the most-parsimonious tree or with Elapsoidea on the maximum-likelihood tree. This result calls into question the monophyly of cobras and underscores the uncertainty of the homology of the hood spreading behavior in cobras and mambas. The relationships of Dendroaspis, Ophiophagus, and Bungarus differed between the parsimony and likelihood analyses, suggesting that more work is necessary to resolve the relationships of these problematic taxa. The genus Dendroaspis, and the species D. polylepis in particular, are regarded as more advanced in than any other snake species, or at least among those in the family Elapidae. In his classic work on reptilian osteology, Dr. Alfred Romer (1956) elevated the genus to a separate subfamilial status (Dendroaspinae) on the basis of this characteristic. Dowling (1959) found this to be an unacceptable criterion for subfamilial distinction. Underwood (1967) described the skull of Dendroaspis as differing from all other elapids in lacking both choanal and maxillary processes on the palatine bones. McDowell (1970) further elaborated upon the distinctiveness of the dentition and palatine kinesis in Dendroaspis but did not remove them taxonomically from other African elapids.

Scientific discovery

The black mamba is one of four species in the African snake genus Dendroaspis that are known as mambas. The species was first described in 1864 by Albert Günther, a German-born British zoologist, ichthyologist, and herpetologist. Soon after, a subspecies was identified, Dendroaspis polylepis antinorii (Peters, 1873), but this is no longer accepted as distinct. According to Broadley and Howell (1991), D. polylepis antinorii is synonymous with D. polylepis. In 1896, zoologist George Albert Boulenger combined the species (Dendroaspis polylepis) as a whole with the eastern green mamba, (Dendroaspis angusticeps), and they were considered a single species from 1896, until 1946, when Dr. Vivian FitzSimons split them into separate species.

Biology

Identification and physical appearance

The adult black mamba's back skin colour is olive, brownish, gray, or sometimes khaki. A young snake is lighter, but not light enough to be confused with the different species of green mamba. Its underbody is cream-coloured, sometimes blended with green or yellow. Dark spots or blotches may speckle the back half of the body, and some individuals have alternating dark and light scales near the posterior, giving the impression of lateral bars. The inside of the mouth is dark blue to inky black. Its body is long and slender and it's head, which readily stands out from the body, is said to be shaped like a coffin. It is a proteroglyphous snake, meaning it has fixed fangs at the front of the maxilla, although they are unique among elapids in that they are semi-moveable. The eyes are dark brown to black, with a silvery-white to yellow edge on the pupils. As they age, their colouration tends to get darker.

The species is the second-longest venomous snake in the world, exceeded in length only by the king cobra. Not all scientific sources agree on the range of lengths for this species, but adult specimens are 2.2 to 2.7 m (7.2 to 8.9 ft) in length on average, with a range of 2.0 to 3.8 m (6.6 to 12.5 ft). Some sources report maximum lengths of 4.3 to 4.5 m (14 to 15 ft). In the 1950s, a black mamba measuring 4.3 m (14 ft), known as "the King of the Mambas" in African Wildlife, was shot in Natal, South Africa. There is no real sexual dimorphism, and both male and female snakes of this species have a similar appearance and tend to be similar in size. Information regarding the lifespan of snakes in the wild is sparse; the longest recorded lifespan of a captive black mamba is 14 years, but actual maximum lifespans could be much greater.

Scalation

The head, body and tail scalation of the black mamba:

|

|

Dentition

Like all of other members of the Elapidae family, black mambas are proteroglyphous, but unlike other elapids such as cobras, kraits, taipans and others, the fangs are not completely "fixed", but are more moveable. According to herpetologist Charles Bogert, the size of elapid fangs are highly variable and the fangs of the mambas are the longest. The fangs of the black mamba are the longest among all elapid species, measuring 13 millimetres (0.51 in) on average and can grow to 22 mm (0.87 in). In comparison, the average length of the western green mamba's fangs are 6.7 mm (0.26 in), the Jameson's mamba's fangs average 7.3 mm (0.29 in), the king cobra's average 8 mm (0.31 in), and the coastal taipan's fangs average 7 mm (0.28 in). Another feature which distinguishes the dentition and the venom delivery apparatus of this species from all other elapids and other species of venomous snake, including those of the family Viperidae is the fact that the fangs are positioned very forward at the most-anterior position possible in its mouth - right up in the front of its upper jaw, unlike other elapids which, for the most part, generally have shorter fangs that are positioned some 11 millimetres (0.43 in) posterior to where the fangs of the black mamba are positioned. This means that (a) the mamba's venom delivery apparatus is more efficient than other venomous snakes; (b) the mamba's fangs are more flexible and as a result they have more control of their fangs' movement; (c) they are capable of delivering copious amounts of venom in virtually every bite, meaning "dry bites" are either non-existent or are exceptionally rare. Despite the obvious similarities, the black mamba's can be distinguished from all other forms on the basis of the morphology of the maxilla. In his classic work on reptilian osteology, Romer (1956) gave the genus separate subfamilial status (Dendroaspinae) on the basis of this characteristic. Dowling (1959) found this to be an unacceptable criterion for subfamilial distinction. Underwood (1967) described the skull of Dendroaspis as differing from all other elapids in lacking both choanal and maxillary processes on the palatine bones. McDowell (1970) further elaborated upon the distinctiveness of the dentition and palatine kinesis in Dendroaspis but did not remove them taxonomically from other African elapids.

Reproduction

Black mambas breed only once a year. The breeding season begins in the spring, which occurs around the month of September in the African regions where these snakes occur, as much of sub-Saharan Africa is in the Southern Hemisphere. In this period, the males fight over females. Agonistic behaviour for black mambas involves wrestling matches in which opponents attempt to pin each other's head repeatedly to the ground. Fights normally last a few minutes, but can extend to over an hour. The purpose of fighting is to secure mating rights to receptive females nearby during the breeding season. Beyond mating, males and females do not interact. Males locate a suitable female by following a scent trail. Upon finding his mate, he will thoroughly inspect her by flicking his forked tongue across her entire body. Males are equipped with two hemipenes. After a successful and prolonged copulation, the eggs develop in the female's body for about 60 days. During this period, the female seeks a suitable place to lay the eggs. Females prefer using abandoned termite mounds as nests. Mature females lay between 15 and 25 eggs, which they hide very well and guard very aggressively. The eggs incubate for about 60 days before hatching. The hatchlings are about 50 centimetres (20 in) in length and are totally independent after leaving the eggs, hunting and fending for themselves from birth. Young hatchlings are as venomous as the adults, but do not deliver as much venom per bite as an adult snake would. Unlike adults who carry about 8-16 ml of venom in their glands, young hatchlings carry only 1–2 ml of venom in their venom glands, which is sufficient quantity for a lethal effect on a human.

Development

Insufficient data or information is available for this species regarding the hatchlings development, but some general assumptions can be made. Black mambas are oviparous. Young incubate inside the eggs for 2 to 3 months after being deposited. They break through the shell with an "egg-tooth". Upon hatching, young are fully functional and can fend for themselves. They have fully developed venom glands (that carry 1-2 ml of venom, which is sufficient to kill an adult human), and are dangerous just minutes after birth. The yolk of the egg is absorbed into the body and can nourish the young for quite some time.

Distribution and habitat

Geographic range

Although it is a large diurnal snake, the distribution of the black mamba is the subject of much confusion in research literature, indicating the poor status of African herpetological zoogeography. However, the distribution of the black mamba in eastern Africa and southern Africa is well documented. Pitman (1974) gives the following range for the species' total distribution in Africa: northeastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, southwestern Sudan, South Sudan to Ethiopia, Eritrea, Somalia, southern Kenya, eastern Uganda, Tanzania, southwards to Mozambique, Swaziland, Malawi, Zambia, Zimbabwe and Botswana to KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa, and into Namibia; then northeasterly through Angola to the southeastern part of the Democratic Republic of Congo. According to WHO, the species is also found in Rwanda. The black mamba is not commonly found above altitudes of 1,000 metres (3,300 ft), although the distribution of black mamba does reach 1,800 metres (5,900 ft) in Kenya and 1,650 metres (5,410 ft) in Zambia. This species is also apparently relatively commoon in Guinea, one of the western-most nation in West Africa. The black mamba was recorded in 1954 in West Africa in the Dakar region of Senegal. However, this observation, and a subsequent observation that identified a second specimen in the region in 1956, have not been confirmed and thus the species' distribution in West Africa is inconclusive. The black mamba's western distribution contains gaps within the Central African Republic, Chad, Nigeria and Mali. These gaps may lead physicians to misidentify the black mamba and administer an ineffective antivenom. West of Ethiopia, it has a curious distribution, with few records. There is a single record from the Central African Republic, two from Burkina Faso, and as mentioned two unconfirmed sightings from Senegal, one from the Gambia, and a possible sighting in Cameroon. These sightings may indicate improper documentation, remaining populations from what was once a larger range, or new populations, indicating a growing range.

Habitat

The black mamba has adapted to a variety of climates, ranging from savanna, woodlands, farmlands, rocky slopes, dense forests and humid swamps. The grassland and savanna woodland/shrubs that extend all the way from southern and eastern Africa to central and western Africa are the black mamba's typical habitat. The snake prefers more arid environments, such as semiarid, dry bush country, light woodland, and rocky outcrops. This species likes areas with numerous hills, as well as riverine forests. Black mambas often make use of abandoned termite mounds and hollow trees for shelter, which it goes back to everynight. The abandoned termite mounds are especially used when the snake is looking for somewhere to cool off, as the mounds are sort of a "natural air-conditioning" system. The structure of these mounds is very complex and elaborate. They have a network of holes, ducts, and chimneys that allow air to circulate freely, drawing heat away from the nest during the day – though without taking too much valuable moisture – while preventing the nest cooling too much at night. As a species which maintains a permanent home range throughout its entire life, the black mamba will always return to its lair at night within this home range if left undisturbed.

Conservation status

This species is classified as Least Concern (LC) on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (v3.1, 2011). The conservation status of this species was last assessed in June 2009 and published in 2010, and it was classed as such due to its very large distribution. Besides its very large geographical distribution, the species has no specific threats that have been reported, and this species is not undergoing significant population declines. This species is regarded as common in sub-Saharan Africa, it has been found as far north as Senegal and as far south as northeast South Africa. Trape (2005) reports this species as far west as Senegal and Guinea. The black mamba is reported to be widespread in locations with suitable habitats. In areas with few records this can be attributed to undercollecting rather than low abundance. It is unlikely that any major threat is impacting this species across its full range. Black mambas prefer to stay away from humans. Human population expansion into its habitat could therefore constitute a potential threat to this species. However, the extent of its range throughout much of Africa means that this should not be considered a serious threat. There are no known species-specific conservation measures in place for this species, however, in places its distribution coincides with protected areas. No conservation measures are required for this species.

Behaviour and ecology

Behaviour

Though they prefer traveling on the ground, and they are considered to be a terrestrial species of snake, they can also be arboreal. They are capable of climbing trees with great agility, quickness and ease. Black mambas maintain a home range, but are not considered highly territorial, preferring to flee from danger when threatened. Unless disturbed, black mambas will remain in the same home range for years or even their entire lifespan. They will also find a permanent home or lair usually in an abandoned termite mound, an aardvark burrow, a hollow tree or log, a rock crevice or sometimes even the roof of a home. They prefer to avoid confrontation and will often attempt to retreat to their lair, attacking anything that gets in their way. This usually results when an threat or predator blocks the snake's direct path to its lair or refuge. A cornered black mamba will quickly become defensive, and display highly aggressive behaviour. They will raise their head far off the ground (up to a metre above ground), open its gape its mouth to display the inner black lining, expand a narrow hood, flick their tongue, hiss loudly, and make mock charges forward towards the threat. They will maintain this defensive posture, staying very alert, keeping a close eye on the threat and making mock charges. Any sudden movements by the threat will cause the mamba to make a full on attack. If the attempt to scare away the threat fails, it will strike repeatedly. If the threat slowly moves away from the mamba, the snake will usually retreat. Strikes will be numerous and extremely rapid, and are often fatal to humans. There is a case in literature in which a man was bitten twice in rapid succession on a motorcycle as he accidentally went over a black mamba. Those two rapid bites proved to be fatal to the man. A diurnal species, the black mamba is usually active from a few hours after sunrise until about an hour before dusk. Being reliant on external heat sources to maintain its body temperature, black mambas spend a lot of their time basking in the sun and unless disturbed, will return to a permanent basking spot, usually a short tree branch, a log, or even a large rock. After basking in the sun for a few hours, they mobilise and begin to actively seek prey, swiftly moving through their home range with their heads held up above ground. The black mamba can travel 11 to 19 km/h (6.8 to 11.8 mph), making it the fastest snake in the world. Although it can reach a maximum of approximately 19 km/h (12 mph), it can only maintain such speeds for short distances, anywhere from 50 to up to 80 metres before it begins to tire and a considerable drop in speed is seen. Besides the relatively high speed with which it moves, the black mamba can strike accurately in any direction, even while moving fast. In striking, it throws its head upward from the ground for about two-fifths the lengths of its body.

Unless completely cornered by a threat with no way to escape, the black mamba will generally make a quick escape when confronted. However, many scientists have taken notice of attacks from this species that come with no prior warning signals and no apparent provocation. It is one of the few venomous snake species of the world, or perhaps the only venomous snake species, that will attack without prior warning signals or provocation. This behaviour, though not typical, has been noted in both captive and wild black mambas. As a result, many snake experts have cited the black mamba as the world's deadliest and most-aggressive snake, noting this tendency to attack without any provocation. It can show an incredible amount of tenacity, fearlessness, and aggression when cornered, during breeding season, or when defending its lair. According to Swaziland-born snake handler and snake expert Thea Litschka-Koen:

Black mambas will kill a dog or several dogs if threatened and it happens quite often. We also find dead cows and horses! We were called by the frantic family late one evening. When we arrived minutes later, two small dogs had already died and two more were showing severe symptoms of envenomation. Within 15 minutes we had found and bagged the snake. By this time the other two dogs were also dead. The snake must have been moving through the garden when it was attacked by the dogs. It would have struck out defensively, biting all the dogs that came within reach. The snake was bitten in several places on its body as well and died about a week later.

— Thea Litschka-Koen

In a different case in which a black mamba was attacked by seven dogs, the snake managed to swiftly envenomate and dispatch all seven dogs without incurring any injuries aside from a few minor and superficial bite wounds on its tail. All seven dogs rapidly succumbed to the mamba's venom, two of the dogs were dead within the first 10–15 minutes, while the others all died, one at a time, in less than an hour. In 2006 the first case of an elephant dying of a snakebite was reported in the October 2006 issue of the journal Applied Animal Behaviour Science. To date, this is the only scientifically documented case of an elephant being killed via snakebite. No other scientifically proven or documented case of an elephant being killed via snakebite exists. On 10 October 2003, sometime between 1:00 pm and 3:00 pm local time, a full grown female African elephant named Eleanor that weighed around 7,500 lb (3,400 kg) at Saraburu National Park in Kenya was bitten by a black mamba. The effects of the venom were rapid; a short time later Eleanor began to slow down, showed an unsteady gait and began to fall behind the rest of the herd, which was highly unusual behaviour for a matriarch, who is always ahead of the herd and leading the way. Not long after, Eleanor fell to the ground and was helped up by another elephant until she fell again and never got up. The bite was fatal to the matriarch, who suffered for a lengthy period of time (just under 24 hours) from the effects of the venom before finally dying. The dramatic images show one elephant, Grace, who was a matriarch of a different herd, struggling to help the 40-year-old matriarch Eleanor, who lay on the ground, languishing in agony and struggling to breath as a result of the black mamba bite. The footage, shot by scientists at Samburu National Reserve in Kenya, show Grace calling out in distress and making desperate attempts to get the dying elephant back onto her feet. The next day, 11 October 2003 at around 11:00 am local time, Eleanor's lifeless body was visited by other elephants, who rocked back and forth in mourning or stood silently, paying their last respects. In all, five distinct herds or families of elephants visited the dead body of Eleanor to pay respect. This female elephant, Eleanor, was a herd matriarch and it had been being observed by a research team of scientists led by Dr. Iain Douglas Hamiltom from Oxford University's Department of Zoology, and the founder of the Save The Elephants charity and the University of California for many years. Although the first scientifically documented case of an adult elephant dying of a snakebite was remarkable, the team of scientists and the public focused their attention on the behaviours and emotions that were displayed by elephants of different families towards the dying matriarch.

Communication and perception

Black mambas show little deviation from the common methods of communication and perception found in snakes. They primarily rely on their eyesight, their tongue, and ability to sense vibration to gather information from their environment. Their eyes are large and they have excellent eyesight which is used to detect motion, to view surroundings, and to help them carefully navigate and move about in their environment. Detection of quick or sudden movements will cause them to strike immediately. The vomeronasal organ (Jacobson's organ), a chemosensory organ located on the roof of their mouth, is involved in the black mambas social chemical communication and in hunting prey. They collect environment stimuli, such as molecules from the air and nearby objects by extending their forked tongue from their mouth. These chemical elements are then deposited in the vomeronasal organ when the tongue is retracted. They lack external auditory structures and cannot hear airborne sounds, but the part of their body in direct contact with the ground is very sensitive to vibrations; thus they are able to sense other animals approaching by detecting faint vibrations in the air and on the ground. Like many snakes, when threatened, they will become defensive and aggressive, displaying a set of warning signals of a possibility of attack.

Hunting, predatory behaviour and diet

Black mambas are opportunistic predators. Studies have shown that the larger snakes will seek out larger prey items. Black mambas are not an exception to that rule and they generally seem to prefer larger sized prey, but will readily take small prey items as well. Although they mainly feed on warm-blooded mammals and birds, they have also been known to occasionally take other snakes. Juvenile black mambas will readily take skinks and lizards. A 2 m (6.6 ft) long black mamba has even been observed feeding on flying termite alates. When hunting, the black mamba is often seen travelling with its head raised well above ground level, quickly moving forward in search of prey. Once prey is detected, the black mamba freezes before hurling itself forward and issuing several quick bites, swiftly killing its prey. If the prey attempts to escape, the black mamba will follow up its initial bite with a series of strikes. It will release larger prey after biting it, but smaller prey, such as birds or mice, are held until the prey's muscles stop moving.

Black mambas feed on a variety of prey, especially mammals, including Rock hyraxes (dassies), various rodents like rats, mice, juvenile Cane rats, Common mole rats, squirrels, bushbabies, elephant shrews and bats. They have also been known to prey on various species of bird and chickens, as well as other snakes on rare occasions. Species of snake which the black mamba has preyed upon include the mole snake, the puff adder and various species of cobra, including the Cape cobra, the Mozambique spitting cobra, and even the Forest cobra. There is a confirmed report of a 3-metre-long (9.8 ft) black mamba, which was witnessed to be feeding on a full-grown, 2.25-metre (7.4 ft) forest cobra, which it had killed. Black mambas also prey on small to medium-sized birds. In one report, a dead 3.2-metre (10 ft) black mamba was found to have a medium-to-large-sized parrot of the genus Poicephalus in its stomach. Black mambas will also occasionally take young blue duikers (Philantomba monticola). Although rare, predation on primates by larger-sized mambas does occur. In one incident, a black mamba pursued a Sykes monkey (Cercopithecus albogularis albogularis), which it killed and ate. After ingestion, powerful enzymes digest the prey, sometimes within 8 to 10 hours.

Predation observations from the field

Black mambas observed on the banks of the Limpopo River. There were three mambas, each about 2.5 metres (8.2 ft) long, occupying a heap of large creeper-covered boulders near a river bank. Gurney's Sugarbird (Promerops gurneyi) would hover near the creeper, virtually motionless despite their whirling wings as they gathered nectar, pursuing one another in swift, darting flight, seemingly unaware of the deadly mamba nearby. Every once in a while one of the birds would fly too close and be snapped up in mid-air by one lightning speed strike. The bird flutters desperately as the deadly toxins take quick toll on the bird. The bird's struggle lasted a few minutes before it hung loosely in the snake's jaws. Sometimes the birds were swallowed immediately, but the mamba more often than not, released its grip, placed its prey on the rock and inspected it by flicking its forked tongue along its body before beginning to devour the prey. A change of diet was provided by a Rock hyrax (Procavia capensis), which ventured too close to the mambas. No sooner had it squatted down to scratch itself than one of the mambas slid from under the creeper, delivered a quick bite, instantly releasing its grip to await the effect of the venom. The rock hyrax quickly scurried back to the crevice as if it has not received a fatal dose. After a few minutes the mamba slid after its prey, dragged it from the crevice, checked to ensure that it was dead then grabbed its head and began to eat its freshly caught meal.

Natural predators and enemies

There are no specific predators of the black mamba, but snakes in general tend to have many. Large adult black mambas have no specific predators other than humans. Humans do not usually consume black mambas; they often kill them out of fear. Other predators will often target eggs or very young mambas, and known predators are large reptiles such as crocodiles or monitors, mongooses, foxes or jackals, and birds of prey, particularly snake eagles (genus Circaetus). Although all commonly prey on snakes, there are two species in particular that do so with high frequency, including preying on black mambas up to 1.35 metres (4.4 ft) long - the two species are the Black-chested Snake Eagle (Circaetus pectoralis) and the Brown Snake Eagle (Circaetus cinereus). Mamba eggs are also susceptible to being eaten by many types of scavengers. Juvenile mambas are also subject to predation from Cape file snakes. The warthog (Phacochoerus africanus) will go out of its way to attack any snake it meets, including species as deadly and venomous as the black mamba, or as large and powerful as the Rock python (Python sebae). Primates such as the carnivorous African baboon will occasionally eat small snakes, including juvenile black mambas by killing them in surprise attacks. Though many baboons are often bitten and subsequently die of the bite inflicted upon it by the juvenile mamba. Some baboons are killed by black mamba bites, when they accidentally rouse the venomous snake. Most large predators and herbivores, including lions, wildebeests and Cape buffalo will steer clear of black mambas. A herd of buffalo who happen to spot a mamba anywhere within the herds vicinity will usually back away and move in the direction opposite to the mamba. The opposite is also true; through vibrations sensed by black mambas, they will avoid herds of animals like Cape buffalo or Wildebeests.

Determining venom toxicity (LD50)

The potency of the venom of wild snakes varies considerably, even within any single species. This is because of assorted influences such as biophysical environment, physiological status, ecological variables, genetic variation (either adaptive or incidental) and various other molecular- and ecological evolutionary factors. Such variation necessarily is smaller in captive populations in controlled laboratory settings though it cannot be eliminated altogether. However, studies to determine snake venom lethality or potency need to be designed to minimise variability and several techniques have been designed to this end. One approach that is considered particularly helpful is to use 0.1% bovine serum albumin (also known as "Fraction V" in Cohn process) as a diluent in determining LD50 values for various species. It results in far more accurate and consistent median lethal dose (LD50) determinations than for example using 0.1% saline as a diluent. Fraction V produces about 95% purified albumin, which is the dried crude venom. Saline as a diluent consistently produces widely varying LD50 results for nearly all venomous snakes; it produces unpredictable variation in the purity of the precipitate (range from 35-60%). Fraction V is structurally stable because it has seventeen disulfide bonds; it is unique in that it has the highest solubility and lowest isoelectric point of all the major plasma proteins. This makes it the final fraction to be precipitated from its solution. Bovine serum albumin is located in fraction V. The precipitation of albumin is done by reducing the pH to 4.8, which is near the pI of the proteins, and maintaining the ethanol concentration to be 40%, with a protein concentration of 1%. Thus, only 1% of the original plasma remains in the fifth fraction. When the ultimate goal of plasma processing is a purified plasma component for injection or transfusion, the plasma component must be highly pure. The first practical large-scale method of blood plasma fractionation was developed by Edwin J. Cohn during World War II. It is known as the Cohn process (or Cohn method). This process is also known as cold ethanol fractionation as it involves gradually increasing the concentration of ethanol in the solution at 5C and 3C. The Cohn Process exploits differences in properties of the various plasma proteins, specifically, the high solubility and low pI of albumin. As the ethanol concentration is increased in stages from 0% to 40% the is lowered from neutral (pH ~ 7) to about 4.8, which is near the pI of albumin. At each stage certain proteins are precipitated out of the solution and removed. The final precipitate is purified albumin. Several variations to this process exist, including an adapted method by Nitschmann and Kistler that uses less steps, and replaces centrifugation and bulk freezing with filtration and diafiltration. Some newer methods of albumin purification add additional purification steps to the Cohn Process and its variations. Chromatographic albumin processing as an alternative to the Cohn Process emerged in the early 1980s, however, it was not widely adopted until later due to the inadequate availability of large scale chromatography equipment. Methods incorporating chromatography generally begin with cryo-depleted plasma undergoing buffer exchange via either diafiltration or buffer exchange chromatography, to prepare the plasma for following ion exchange chromatography steps. After ion exchange there are generally further chromatographic purification steps and buffer exchange.

However, chromatographic methods for separation started being adopted in the early 1980s. Developments were ongoing in the time period between when Cohn fractionation started being used, in 1946, and when chromatography started being used, in 1983. In 1962, the Kistler & Nistchmann process was created which was a spin-off of the Cohn process. Chromatographic processes began to take shape in 1983. In the 1990s, the Zenalb and the CSL Albumex processes were created which incorporated chromatography with a few variations. The general approach to using chromatography for plasma fractionation for albumin is: recovery of supernatant I, delipidation, anion exchange chromatography, cation exchange chromatography, and gel filtration chromatography. The recovered purified material is formulated with combinations of sodium octanoate and sodium N-acetyl tryptophanate and then subjected to viral inactivation procedures, including pasteurisation at 60°C. This is a more efficient alternative than the Cohn process for four main reasons: 1) smooth automation and a relatively inexpensive plant was needed, 2) easier to sterilize equipment and maintain a good manufacturing environment, 3) chromatographic processes are less damaging to the albumin protein, and 4) a more successful albumin end result can be achieved. Compared with the Cohn process, the albumin purity went up from about 95% to 98% using chromatography, and the yield increased from about 65% to 85%. Small percentage increases make a difference in regard to sensitive measurements like purity. There is one big drawback in using chromatography, which has to do with the economics of the process. Although the method was efficient from the processing aspect, acquiring the necessary equipment is a big task. Large machinery is necessary, and for a long time the lack of equipment availability was not conducive to its widespread use. The components are more readily available now but it is still a work in progress.

Venom, envenomation and antivenom

Like many snakes, the venom toxicity (LD50) of individual specimens can show considerable variation which can be due to geographical region, seasonal variation, diet, habitat, and age-dependent change. Black mambas are the most-evolved, venomous-snake species in their method of delivering venom. Their fangs for instance, are the longest of any elapid species and the other three genus Dendroaspis members (D. viridis, D. jamesoni, and D. angusticeps) average longer fangs among snakes within their size range -/+ 12 inches. The black mamba also have are very much forward located fangs in their mouth unlike in any other venomous snake. This makes the delivery of the venom the most-effective of any venomous snake species on earth. The venom of the black mamba contains proteins of very low molecular weight (the mamba's main toxins, the dendrotoxins have a molecular weight of less than 7 kDa), the very high activity in terms of hyaluronidases, which is also essential in facilitating dispersion of venom toxins throughout tissue (spreading the venom through the body) by catalyzing the hydrolysis of hyaluronan, a constituent of the extracellular matrix (ECM), hyaluronidase lowers the viscosity of hyaluronan, and Dendroaspin natriuretic peptide (DNP), a newly discovered component of mamba venom, is the most-potent natriuretic peptide and it's unique to mambas. It is a polypeptide analogous to the human atrial natriuretic peptide; it is responsible for causing diuresis through natriuresis and dilating the vessel bloodstream, which results in, among other things, acceleration of venom distribution in the body of the victim, thereby increasing tissue permeability. Not only does this species have the most-evolved and effective venom delivery apparatus, but the crude venom itself is of very low viscosity compared to all Viperidae species and the vast majority of Elapidae species. As a result the venom is able to spread extraordinarily rapidly within the bitten tissue, causing serious harm and death more rapidly than any other snake species. This is why the black mamba has the shortest death time among all venomous snakes, both in humans and animal models. It is the most rapid-acting snake venom known. In a study, a mouse injected with an overodse of black mamba toxins subcutaneously, died in 4.5 minutes. Such short death times have never been seen with any other snake venom toxins. The shortest death time for any other snake was in the range of 7–8 minutes, in a mouse which was subcutaneously injected with an overdose of coastal taipan toxins.

Using 0.1% bovine serum albumin chromatography, the final precipitate (98% of the solidified crude venom) is 98% purified albumin, the median lethal dose results for the black mamba were 0.01 mg/kg IP, 0.02 mg/kg IV and 0.05 mg/kg SC. Due to the 98% purity of the dried crude venom produced in this process (compare to 40-60% purity of dried crude venom when 0.1 saline solution is used), the toxicity (LD50) values of the venom is nearly exactly accurate and represents the true lethality of the venom. The black mamba is the fourth-most-venomous snake in the world, and its venom consists mainly of highly potent pre-synaptic and post-synaptic neurotoxins; it also contains cardiotoxins, fasciculins, and calciseptine. Median lethal dose (LD50) values for this species' venom can varies tremendously based on many different factors, including on the diluent used. Ernst and Zug et al. 1996 listed a value of 0.02 mg/kg for intravenous injection and 0.05 mg/kg for subcutaneous injection (diluent used was 0.1% bovine albumin serum). One study showed the intraperitoneal injection LD50 in mice was very toxic: 0.01 mg/kg (0.1 bovine albumin serum). In the study, seizure threshold was significantly lowered and the mice went through convulsions. Significant changes in motor activity were observed and there were changes in structure or function of salivary glands. Using 0.1 saline as a diluent, the Australian Venom and Toxin database listed a value of 0.32 mg/kg SC, while Spawls & Branch and Minton & Minton both listed the SC LD50 at 0.28 mg/kg (saline) and Brown lists a murine value of 0.12 mg/kg (saline) SC. Observations made in the field reveal that that primates are especially susceptible to black mamba venom. They have predated on Sykes monkeys, which they die very rapidly after a bite, and Chacma baboons (Papio ursinus), when bitten by a black mamba when they accidentally rouse the snake, die literally within minutes of being bitten. This is further evidence that the venom of this species is especially toxic to primates, including humans.

It is estimated that only 10 to 15 milligrams (0.15 to 0.23 gr) will kill a human adult, and its bites delivers about 120 milligrams (1.9 gr) of venom on average, although a large specimen can often deliver 200 to 300 milligrams (3.1 to 4.6 gr) they may even deliver up to 400 milligrams (6.2 gr) of venom in a single bite. One liquid drop (0.05 ml) of this species' venom is more than enough to kill an adult male human. The black mamba's venom glands contain approximately 8–16 ml of liquid venom. In the freshly hatched young, the amount is 1–2 ml of venom, which is sufficient quantity for a lethal effect on a human. Black mamba bites are most commonly inflicted on the calf and up to about 10 centimetres (3.9 in) above the knee. Its bite is often called "the kiss of death" because before antivenom was widely available, the mortality rate from a bite was 100% due to the highly toxic nature of the venom and the rapidity in which a bite is fatal. The fatality duration and rate depends on various factors, such as the health, size, age, and psychological state of the victim, the penetration of one or both fangs from the snake, the amount of venom injected, the pharmacokinetics of the venom, the location of the bite, and its proximity to major blood vessels. The health of the snake and the interval since it last used its venom mechanism is important, as well. Severe black mamba envenomation can kill a person in 20 minutes, but sometimes it takes up to 6–8 hours, depending upon many factors.

If bitten, prominent neurotoxicity invariably ensues. Their venom contains neurotoxically acting nicotinic acetylcholine receptor antagonists analogical to the postsynaptic neurotoxins of other elapids classified as α, β, γ and δ neurotoxins. Mambas also carry powerful, rapid-acting and efficient pre-synaptic neurotoxins called dendrotoxins (DTX) - peptides causing inhibition by blocking voltage channelled by potassium for the re-polarization of neurons, thus causing extension of the process. This way, the substances support muscular paralysis, either at a central level or by exhausting neuromuscular junctions by super-threshold stimulation. The effect of DTX is very probably manifest on the vegetative nerves as well. The DTX I subtype of the black mamba is the most rapid-acting and efficient venoms of all known snake-venom toxins. A number of peptides isolated from mamba's venom potentiate neurotransmission in the central nervous system as well as in peripheral nerves. They are limited only to the mamba's venom outfit. The peptides, acting as muscarinic acetylcholine receptor ligands, may probably cause activation in the central nervous system. Fasciculins are peptide acetylcholinesterase inhibitors increasing the intrasynaptic amount of acetylcholine, which results in fasciculation of muscles. Dendroaspin natriuretic peptide (DNP) is a polypeptide analogous to the human atrial natriuretic peptide; it is responsible for causing diuresis through natriuresis and dilating the vessel bloodstream, which results in, among other things, acceleration of venom distribution in the body of the victim. Mamba venom has powerful cardiotoxic components as well. The venom displays relatively high activity in terms of hyaluronidases, which is also essential in facilitating propagation of venom components throughout tissue.

Black mamba bites in general often result in severe, life threatening envenoming that rapidly progresses to signs of prominent neurotoxicity, particularly causing respiratory paralysis in extraordinarily rapid time (10–20 minutes) if the nature of the bite is very severe. Very urgent assessment and management is required. All cases must be admitted, as envenoming can be delayed, though this is extremely rare among cases of envenomation by this species, and can recur over several days, despite treatment, so early discharge is inappropriate. Patients should have an insertion of an IV line and be given an initial IV fluid load. Supportive respiratory therapy, including intubation and mechanical ventilation is required and is mandatory in cases of black mamba envenomation. Local symptoms of envenoming by this species is often minimal, but can be moderate to severe in very rare cases. Bleeding might occur from the bite wound. Minor redness and minor localized edema might appear around the bitten site. Pain is minimal and may last up to a week. Local tissue damage (necrosis, blistering) appears to be relatively infrequent and of minor severity in most cases of black mamba envenomation. Major swelling of the bitten limb can occur, but is uncommon. It is unclear if this can result in hypovolaemic shock secondary to fluid shifts. Bleeding might occur from the bite wound. There are no reports of compartment syndrome occurring. Systemic symptomology, even life threatening symptoms, can manifest very early on - within 10 minutes, or less. Common symptoms are rapid onset of tingling sensations, muscle twitching, dizziness, excessive sweating, headache, drowsiness, coughing or difficulty breathing, severe abdominal pain, erratic heartbeat, collapse, and convulsions. Other common symptoms which come on rapidly include neuromuscular symptoms, shock, loss of consciousness, hypotension, pallor, ataxia, urinary and fecal incontinence, excessive salivation (oral secretions may become profuse and thick), limb paralysis, nausea and vomiting, ptosis, and fever. Nephrotoxicity or renal failure has been reported in some black mamba bites in humans and in animal models. Oliguria or anuria with possible changes in urinary composition will herald the development of renal failure. Cardiotoxicity is common in black mamba bites in humans. Changes in cardiovascular status result primarily from the effects of circulatory collapse and shock, as well as vagal blockade resulting in tachydysrhythmias. Pulse and pressure may initially be within normal ranges, but may change with rapid onset cardiovascular collapse. Myocardial infarctions (heart attacks) have also been reported in black mamba envenomation. The most-important treatments are support of failing respiratory function and IV antivenom therapy using the SAIMR Polyvalent Antivenom. The initial dose will depend on severity of envenoming, but bites from this species generally require an initial dose of 10 vials. Further doses are often required. The criteria for further dosing are not well established, but if there is inadequate response by 1 hour after the initial dose, giving a repeat dose of 5-10 vials is usually required. It may take up to 30+ vials of antivenom to fully neutralize the venom. Medical staff should always have adrenaline and resuscitation equipment ready in case of adverse reactions. It is unclear if acetylcholinesterase inhibitor will be effective in a black mamba bite, with one report of useful response in a Western green mamba (Dendroaspis viridis) bite, but since a prime venom component is an effective anticholinesterase (fasciculins), the value of this therapy is most uncertain theoretically. Death is often due to suffocation resulting from paralysis of the respiratory muscles, but it may also result from a heart attack.

Clinical cases and antivenom

The mortality rate is 100% if untreated, and 14% even with antivenom therapy.

- Dangerousness of bite: Severe Envenoming likely (>80%), high lethality potential.

- Rate of Envenoming: >95%.

- Untreated Lethality Rate: 100%.

Envenomation by this species invariably causes prominent neurotoxicity due to the fact that black mambas possess a highly potent and rapid acting venom and often strike repeatedly in a single lunge, biting the victim many times in extremely rapid succession. Such an attack is so fast, lasting less than one second and so it appears to be a single strike and single bite. With each bite the snake delivers anywhere from 100 to 400 milligrams (1.5 to 6.2 gr) of a rapid-acting and highly toxic venom. As a result, the doses of antivenom required for successful treatment are often massive (10–20+ vials) for bites from this species. It is not unusual to use 30+ vials in extremely severe cases. In addition to antivenom therapy, endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation are required for supportive therapy.

A polyvalent antivenom produced by the South African Institute for Medical Research (SAIMR) is used to treat all black mamba bites from different localities. Due to antivenom, a bite from a black mamba is no longer a certain death sentence. But in order for the antivenom therapy to be successful, vigorous treatment and large doses of antivenom must be administered very rapidly post-envenomation. In case studies of black mamba envenomation, respiratory paralysis has occurred in less than 15 minutes. Due to the nature of the lethality of the venom and the associated 100% fatality rate among black mamba bites stimulated the production of a specific mamba antivenom, and in 1967 Louw reported the first successful treatment of two black mamba bites with a specific antivenom prepared by the South African Institute of Medical Research (SAIMR). This was the first time that any victim of a black mamba bite was scientifically documented to survive envenomation. Although antivenom saves many lives, mortality due to black mamba envenomation is still at 14%, even with antivenom therapy. According to scientist and herpetologist, Dr. David A. Warrell, human victims of black mamba bites seldom reach the hospital alive.

Case reports

In a reported case in which a black mamba attacked and killed nine people at the same time is explained by biologist Dr. Joe Wasilewski in a short video clip. In an African village, screams were heard coming from someone in a hut. Another person heard the screams and entered the hut but never came out. This continued until a total of nine people entered the hut. Screams were heard but after the ninth person who entered the hut, nobody else was willing to see what was going on inside. The next day, some courageous locals gathered with spears and other weapons and entered the hut. As they walked into the hut, they witnessed nine dead people and a baby who was alive but hungry. The hut was a refuge which the mamba had decided to spend the night in, but as one person after the other walked into the hut, the snake felt cornered and became very defensive. It attacked each and everyone of the people that entered the hut. Because of the disturbingly rapid death times of the nine victims, the attacks must have been extraordinarily savage in nature.

In a case of 10 envenomations in South Africa all ten received medical treatment but only five lived. One developed respiratory paralysis in ten minutes, and all other patients were showing signs of neurotoxicity upon arrival at the hospital. Symptoms initially included mild swelling at bite site, confusion, excessive sweating, urinary incontinence, fecal incontinence, loss of coordination, ptosis, erratic heartbeat, drowsiness, and breathing difficulties. Out of the 10 patients, five were fatal despite prompt hospitalization and induction of medical treatment. One patient died in just under 30 minutes. The four other patients all died within 3–8 hours post-envenomation. The other five patients survived but all of them required massive amounts of antivenom and assisted mechanical ventilation for a prolonged period. Three of the patients were on mechanical ventilation for 4 days, while the other two required assisted mechanical ventilation for 6 days. Cases of this nature are not at all uncommon among cases of envenomation by the black mamba.

Another case, which was publicized, was that of 28-year old British student named Nathan Layton. He was bitten by a black mamba and died of a heart attack in less than an hour after being bitten in March 2008. The black mamba had been found near a classroom at the Southern African Wildlife College in Hoedspruit, where the man was training to be a safari guide. Layton was bitten by the snake on his index finger while it was being put into a jar, but Layton didn't realize he'd been bitten. He thought the snake had only brushed his hand. After 30 minutes the bite, Layton complained of blurred vision. Not long after, He collapsed and died of a heart attack, nearly an hour after being bitten. He was pronounced dead at the scene.

A 34-year-old man was bitten three times on his right ring finger by a 2.25 metres (7 ft 5 in), positively identified, black mamba. He reached the clinic 35 minutes after the bite. He complained of pain at the bite site, a sensation of a swollen tongue, dizziness and a trouble breathing. He was restless, sweating profusely and vomited once. The blood pressure was 100/60 mm Hg, pulse rate was 112 bpm and there were no signs of paralysis. Three fang marks were found on the right ring finger with fairly marked local swelling. He was given 70 ml of antivenom IV over 40 mins, preceded by hydrocortisone 500 mg and promethazine 25 mg IV. The man's condition improved after another 40 ml of antivenom, although the patient remained restless and was hypotensive for 2 hours after the bite. The man was admitted to the clinic and observed for 48 hours. Vital signs were within normal limits. He developed swelling and itching of his right hand and forearm, which was treated with betamethasone and a topical antihistamine cream. The man was given anti-tetanus toxoid 0.5 ml IM and put on ampicillin 250 mg for a total of 5 days. He was discharged in good health three days after the bite.

In between 1978-1982, 251 snake bitten and 3 eye envenomed patients were admitted to Shongwe hospital. The hospital is situated in KaNgwane in the Transvaal, roughly 40 kilometres (25 mi) from the southern border of Kruger National Park and serves an area of over 150,000 people. In the area, only 8 species can cause death - the black mamba, the snouted cobra, the forest cobra, and the rinkhals which are species that produce neurotoxic venom. The other four species are the Mozambique spitting cobra which has a mixture of neurtoxic and cytotoxic venom, the puff adder (Bitis arietans) which is a hemotoxic and cytotoxic species and two colubrids (rear-fanged) also occur in the region - the boomslang and Twig snake. The black mamba was responsible for 20 of the 251 bites (8%). There were 5 bites (2%) which occurred on the head or neck and another 5 bites which occurred on the torso and 9 of those bites were attributed to the mamba. In all, 4 resulted in death (1.6%). Three of the 4 were due to mamba bites. The only other death was due to a snouted cobra. Two of the mamba victims died rapidly while en route to the hospital, while the other died in the hospital despite antivenom, which was given in insufficient quantities due to low supply.

A series from Triangle Hospital in Zimbabwe showed 7 cases of neurotoxic bites from elapid snakes; 1 case was confirmed as a black mamba bite and there was strong evidence that the other bites were also due to the mamba. There are only two elapid species that can cause death in the area - the black mamba and snouted cobra. In the area, the snouted cobra, was extremely uncommon during the period of the study and 45-50% of bites by this species are "dry bites". Black mambas were abundant in the area and rarely, if ever, cause a "dry bite". On this basis, experts believe all seven reported cases were due to the mamba.

A 3-year old child was bitten by a snake at dusk outside her house on the in 1975. The mother heard a hissing sound and saw a snake several feet long and grey-black in colour. The mother claimed it was a black mamba. She immediately found a ride to the hospital. The child arrived at the hospital 30 minutes after the bite, sweating profusely and unable to stand. At 60 mins post-bite, the child was cold, still sweating profusely, and semi-comatose. All limbs were flaccid, exhibited stertorous respiration and marked salivation. The child was given a total of 20 ml of antivenom, 10 ml IV and 10 ml IM. The child was also given hydrocortisone 100 mg IV]. Two hours post-bite, the child's condition continued to deteriorate. At 2h10m post-bite, the child's limbs were involuntarily flailing about. An unknown dose of diazepam (Valium) was given IV. At 2h20m after bite, the child goes into cardiac arrest. The child was already previously intubated, showed intermittent positive pressure respiration with oxygen. Medical staff performed cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). At 2h25m, the child is given sodium bicarbonate and a dose of adrenaline. At 2h35m post-bite, CPR was discontinued due to continued absence of a heart beat. Despite antivenom, intubation and other supportive therapy, the child died 2h20m post-bite.

Between June and December 2004, in the vicinity of Kindia, an area of Guinea Conakry where the incidence of snakebite is among the highest reported in the world, a collection of snakes was undertaken in the vicinity. A total of 916 specimens were collected, including 90 Elapidae (9.8%) and 174 Viperidae (19.0%). The black mamba was represented by eight specimens, i.e. almost 1% of the snakes collected. This species, which is considered as very rare in West Africa, appears common in this area of Guinea. Treatment of snakebites was poor due to the cost and low availability of antivenom. In all there were 20 fatalities (2.2%), including all eight black mamba bite victims (100%), of which only three received antivenom. But because black mamba bites require anywhere from 20-30 or more vials of antivenom, none of the three treated were able to survive. Four died rapidly while en route to the local hospital.

In Zimbabwe, there were a total of 995 snakebite incidents between 1980 and 1989. The various species of cobra that occur in Zimbabwe (they are the snouted cobra, Anchieta's cobra, forest cobra, black-necked spitting cobra, Mozambique spitting cobra, and the rinkhals), as a group, were responsible for the majority of the snake bites (37%), followed by the puff adder which was responsible for 20%, and than the black mamba and eastern green mamba (combined) were responsible for 18% of all snake bites, but the number of deaths due to black mamba envenomation was the highest. In all there were 20 fatalities out of the 995 bitten. Of the twenty, 13 were caused by the black mamba, 4 were caused by the forest cobra, 2 by the snouted cobra and 1 by the puff adder. Several bites were attributed to the boomslang during the period in review, but none were fatal.

A survey of snakebites in South Africa from 1957 to 1963 recorded over 900 venomous snakebites, but only seven of these were confirmed black mamba bites. From the 900 bites, only 21 ended in fatalities, including all seven black mamba bites – a 100% mortality rate.

Danie Pienaar, head of South African National Parks Scientific Services survived the bite of a Black mamba without anti-venom. he was featured on I'm Alive (TV series) (SE1EP8).

Toxins

Mamba venom is made up mostly of dendrotoxins (dendrotoxin-k – "Toxin K", dendrotoxin-1 – "Toxin 1", dendrotoxin-3 – "Toxin 3", dendrotoxin-7 – "Toxin 7", among others), fasciculins, and calciseptine. Dendrotoxins exert unusual and devastating neurotoxic effects. Being a protein of low molecular weight, the venom and its constituents are able to spread extraordinarily rapidly within the bitten tissue, so black mamba venom is the most rapid-acting of all snake venoms. The dendrotoxins disrupt the exogenous process of muscle contraction by means of the sodium potassium pump. Toxin K is a selective blocker of voltage-gated potassium channels, and Toxin 1 inhibits the K channels at the pre and postsynaptic level in the intestinal smooth muscle. It inhibits Ca-sensitive K channels from rat skeletal muscle‚ incorporated into planar bilayers (Kd = 90 nM in 50 mM KCl), Toxin 3 inhibits M4 receptors, while Toxin 7 inhibits M1 receptors. The calciseptine is a 60 amino acid peptide which acts as a smooth muscle relaxant and an inhibitor of cardiac contractions. It blocks K-induced contraction in aortic smooth muscle and spontaneous contraction of uterine muscle and portal vein. The venom is highly specific and virulently toxic. Black mamba venom can kill a mouse in 4.5 minutes, the shortest time among all known venomous snakes.

Dendrotoxins and fasciculins are so potent, rapid-acting and devastating in their effects that they have been researched as possible chemical warfare agents.

Black mamba venom also contains proteins, mambalgins, which in mice act as an analgesic as strong as morphine, but without most of the side-effects. Mambalgins cause much less tolerance than morphine and no respiratory distress. They act through a completely different route, acid-sensing ion channels. Laboratory tests suggest that the pain-killing effect on humans may be similar, but this had not been tested as of October 2012. Researchers were puzzled about the advantage this substance could give the snakes.

Availability of treatment

Venomous snakebites are rampant in sub-Saharan Africa. Although black mambas cause only 0.5-1% of snakebites in South Africa, they produce the highest mortality rate and the species is responsible for many snake bite fatalities. Although antivenom is now widely available and bite victims can rapidly access adequate treatment in most of Africa's medium-to-large cities and nearby areas, some severely impoverished African nations do not always have antivenom in stock, as it is very expensive, even by western standards. Most of those bitten by a venomous African snake species require 5 vials of antivenom as an initial dose. A single vial of antivenom can cost anywhere from USD $160–$200, and black mamba envenomation is the costliest to treat, as 10-12 vials of antivenom are often required as an initial starting dose and more than 20 vials are often required for effective treatment. As a result of the severe nature of black mamba bites and the cost of antivenom required to treat such a bite, deaths due to black mamba envenomation are very common in Swaziland and the rate of mortality is close to 100%. Other contributing factors besides the lack of antivenom are lack of mechanical ventilation equipment, proper envenomation symptom control, and drugs. Some victims will not access medical care, but rather go to a traditional healer or witch doctor. However, Swaziland does have "Antivenom Swazi", a charity whose mission is to raise enough funds to create a "bank" of antivenom for treating snakebites, but they are specifically focused on treating black mamba bite victims in Swaziland. Although bites attributed to this species are less likely compared to most African cobra species and to the puff adder, the mortality rate is significantly higher among those envenomed by black mambas. According black-mamba expert and handler, Thea Litschka-Koen, black mambas only cause 10% of the total number of bites in Swaziland, but cause more fatalities than the Mozambique spitting cobra, which causes 80% of all bites in the same country. In Tanzania, while the black mamba is second to the puff adder in causing human fatalities, the puff adder bites almost six times the number of people than the black mamba does.

Relationship with humans

Myths and legends

Although respected by local populations in Africa, the black mamba still faces human persecution because of its fearsome reputation throughout its range. With an increasing amount of its territory being inhabited by humans, the black mamba often finds itself cornered with no escape. In this situation, it will stand its ground and display incredibly aggressive behavior. A group of people is usually required to kill it, as it is very fast and agile, striking in all directions while a third of its body is 3–4 feet (0.91–1.22 m) above the ground. The deep fear of this snake stems not only from its reputation for aggression, speed, and venom toxicity, but from stories and legends that have been passed down from generation to generation throughout sub-Saharan Africa. One such myth claims that the black mamba will bite its tail to make a hoop, so that it can roll down a mountain. As the mamba gets to the bottom, it straightens its body out like a missile and attacks at high speed. Another myth claims that the black mamba has higher intelligence enabling it to plot an attack on humans, where it 'ambushes' an automobile by waiting along on the road, the mamba will then coil itself around the axle of the automobile to strike at the driver when he gets home. Another popular myth claims that the mamba can balance its entire body on the tip of its tail.

References

- ^ "Dendroaspis polylepis". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 12 December 2013. Cite error: The named reference "ITIS" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Uetz, P. "Dendroaspis polylepis Günther, 1864". Reptile Database. Zoological Museum Hamburg. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ^ Spawls, S.; Branch, B. (1995). The dangerous snakes of Africa: natural history, species directory, venoms, and snakebite. Dubai: Oriental Press: Ralph Curtis-Books. pp. 49–51. ISBN 0-88359-029-8.

- ^ Guinness World Records (2013). Guinness World Records 2014 : Officially Amazing. Guinness Publishing. ISBN 978-1-897553-28-2.

- Capstone Press (2005). Mambas. Compass Point Books. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-7368-2137-7.

- ^ Greene; Fogden, HW.; M. (2000). Snakes: The Evolution of Mystery in Nature. United States: University of California Press. p. 351. ISBN 0-520-22487-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chippaux, JP. (2006). Snake Venoms and Envenomations. United States: Krieger Publishing Company. p. 300. ISBN 1-57524-272-9.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

FitzSimonswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ O'Shea, M. (2005). Venomous Snakes of the World. United Kingdom: New Holland Publishers. p. 78. ISBN 0-691-12436-1.

... in common with other snakes they prefer to avoid contact; ... from 1957 to 1963 ... including all seven black mamba bites - a 100 per cent fatality rate

- ^ Mitchell, D. (September 2009). The Encyclopedia of Poisons and Antidotes. New York, USA: Facts on File. p. 324. ISBN 0-8160-6401-6.

- ^ "Immediate first aid for bites by Black Mamba (Dendroaspis polylepis polylepis)". Toxicology. University of California, San Diego. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

- ^ Reichl; Ritter, F-X; L. (2010). Illustrated Handbook of Toxicology (1st edition ed.). Thieme. pp. 262–263. ISBN 978-3-13-126921-8.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Krugerpark News (page 89). Surviving a Black Mamba Bite. Kruger National Park. Retrieved April 11, 2014.

- ^ Branch, B. (1988). Branch's Field Guide Snakes Reptiles Southern Africa. Curtis Publishing, Ralph. ISBN 978-0-88359-023-2.

- ^ Wasilewski, Joe (2011). Wildlife Footage (Motion picture). Africa: Youtube. Retrieved 31 December 2013. Cite error: The named reference "JW presentation00" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Department of the Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery (2013). Venomous Snakes of the World: A Manual for Use by U.S. Amphibious Forces. Skyhorse Publishing. p. 93. ISBN 978-1-62087-623-7.

- ^ Haji, R. "Venomous snakes and snake bite" (PDF). Zoocheck Canada. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- Austin, Stevens (2001). Austin Stevens: Snakemaster. Namibia: Youtube. Event occurs at 0m55s. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

{{cite AV media}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - "dendro-". Collins English Dictionary - Complete & Unabridged 10th Edition. HarperCollins Publishers. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- "aspis, asp". Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- Rauchenberger, M. (18 May 1988). "A New Species of Allodontichthys (Cyprinodontiformes: Goodeidae), with Comparative Morphometrics for the Genus". Copeia – American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists. 2: 433–441. doi:10.2307/1445884. JSTOR 1445884. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- Hardy Fern Library – polylepis etymology. Hardyfernlibrary.com. Retrieved on 2012-07-08.

- ^ "Dendroaspis polylepis – General Details, Taxonomy and Biology, Venom, Clinical Effects, Treatment, First Aid, Antivenoms". WCH Clinical Toxinology Resource. University of Adelaide. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- "Dendroaspis". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- ^ Bauchot, R. (2006). Snakes: A Natural History. Sterling. pp. 41, 76, 176. ISBN 978-1-4027-3181-5.

- Broadley, D. (1983). "9". In Fitzsimmons, VFM (ed.). Fitzsimmons' Snakes of Southern Africa (Reprint, revised ed.). Johannesburg, South Africa: Delta Books, LTD. ISBN 978-0-908387-04-5.

- Slowinski, JB; Knight, A; Rooney, AP (December 1997). "Inferring species trees from gene trees: A phylogenetic analysis of the Elapidae (Serpentes) based on the amino acid sequences of venom proteins". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 8 (3): 349–62. doi:10.1006/mpev.1997.0434. PMID 9417893.

- ^ Deufel, A.; Cundall, D. (2003). "Prey Transport in "Palatine-Erecting" Elapid Snakes" (PDF). Journal of Morphology. 25 (8): 358–375. doi:10.1002/jmor.10164. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- Günther, A. "Report on a collection of reptiles and fishes made by Dr. Kirk in the Zambesi and Nyassa Regions". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 1864: 303–314 .

- "Dendroaspis polylepis". Catalogue of Life. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- Broadley, DG; Howell, KM (1991). "A checklist of the reptiles of Tanzania, with synoptic keys". Syntaurus. 1 (1): 1–70.

- Boulenger, GA (1896). Catalogue of the Snakes in the British Museum (Natural History), Volume III (Revised, 2010 ed.). London: Nabu Press. ISBN 978-1-176-56979-9.

- Loveridge, A. "The Green and Black Mambas of East Africa" (PDF). Museum of Comparative Zoology, Cambridge, Mass. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- ^ Marais, J. (2004). A Complete Guide to the Snakes of Southern Africa. Cape Town, South Africa: Struik Nature. pp. 95–97. ISBN 1-86872-932-X. Cite error: The named reference "Marais" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Broadley; Doria; Wigge, DG; CT; J (2003). Snakes of Zambia: An Atlas and Field Guide. Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Edition Chimaira. p. 280. ISBN 978-3-930612-42-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mattison, C. (1987-01-01). Snakes of the World. New York: Facts on File. p. 164. ISBN 0-8160-1082-X.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

TP02was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Black Mamba Fact File". Perry's Bridge Reptile Park. Snakes-Uncovered. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ^ Murphy, JC. (2010). Secrets of the Snake Charmer: Snakes in the 21st Century. iUniverse. p. 92. ISBN 978-1-45-022126-9.