| Revision as of 16:35, 8 April 2014 editAli-al-Bakuvi (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users1,587 edits Reverted to revision 603319771 by Nirril (talk): This info was better as it explained the numbers better. (TW)← Previous edit | Revision as of 16:37, 8 April 2014 edit undoNirril (talk | contribs)14 edits Undid revision 603323171 by Ali-al-Bakuvi (talk) What is written in a source should be reflected in the article, too.Next edit → | ||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

| | image3 = Tuhaj Bej.jpg| caption3 = ] | | image3 = Tuhaj Bej.jpg| caption3 = ] | ||

| | image4 = Taras Triasylo.jpg| caption4 = ] | | image4 = Taras Triasylo.jpg| caption4 = ] | ||

| | image5 = |

| image5 = IGasprinskiy.jpg| caption5 = ] | ||

| | image6 = |

| image6 = Noman Chelebicihan.jpg| caption6 = ] | ||

| | image7 = |

| image7 = AhmedIhsanKirimli.jpg| caption7 = ] | ||

| | image8 = Mustafa Dzhemilev1.jpg| caption8 = ] | | image8 = Mustafa Dzhemilev1.jpg| caption8 = ] | ||

| | image9 = |

| image9 = Khudzhamov.jpg| caption9 = ] | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| |poptime = |

|poptime = ranges from 500,000 to 6,500,000 | ||

| |popplace = | |popplace = | ||

| |region1 = ]{{ref|country}} | |region1 = ]{{ref|country}} | ||

| |pop1 = 245,000 | |pop1 = 245,000 | ||

| |ref1 = <ref>2001 Ukrainian census for the ]</ref> | |ref1 = <ref>2001 Ukrainian census for the ]</ref>|region2 = {{flag|Uzbekistan}} | ||

| |region2 = {{flag|Uzbekistan}} | |||

| |pop2 = 188,772 | |pop2 = 188,772 | ||

| |ref2 = <ref>{{ru icon}} </ref> | |ref2 = <ref>{{ru icon}} </ref> | ||

| |region3 = {{flag|Turkey}} | |region3 = {{flag|Turkey}} | ||

| |pop3 = 150,000 - 6,000,000|ref3 = <ref name="iccrimea.org"></ref> | |||

| |pop3 = c. 150,000 | |||

| |ref3 = <ref name="iccrimea.org"> "No reliable figures are available. The Emel activists provide a number of 6 million, and Sel says 'at least 4 to 5 million' (Sel 1996: 12). These figures are not more than estimates. Tatars calculate it by taking one million immigrants as a starting point and multiplying this number by the birth rate in the span of the last hundred years."</ref> | |||

| |region4 = {{flag|Romania}} | |region4 = {{flag|Romania}} | ||

| |pop4 = 24,137 | |pop4 = 24,137 | ||

| Line 46: | Line 45: | ||

| |region11 = | |region11 = | ||

| |pop11 = | |pop11 = | ||

| |rels = ] |

|rels = ] | ||

| |langs = ], ], ], ] | |langs = ], ], ], ] | ||

| |related = | |related = | ||

Revision as of 16:37, 8 April 2014

Ethnic group

| ||||||||||

| Regions with significant populations | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crimean peninsula | 245,000 | |||||||||

| 188,772 | ||||||||||

| 150,000 - 6,000,000 | ||||||||||

| 24,137 | ||||||||||

| 2,449 | ||||||||||

| 1,803 | ||||||||||

| 1,532 | ||||||||||

| Languages | ||||||||||

| Crimean Tatar, Russian, Turkish, Ukrainian | ||||||||||

| Religion | ||||||||||

| Sunni Islam | ||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Crimean Tatars |

|---|

| By region or country |

| Religion |

| Language |

| Culture |

| History |

| People and groups |

Crimean Tatars (Template:Lang-crh or Qırım, Qırımlı, Template:Lang-ru, Template:Lang-uk) are a Turkic ethnic group native to the Crimean peninsula. They formed the majority population in Crimea from the time of their ethnogenesis in the 15th century until their 1944 deportation under Soviet rule.

Crimean Tatars were allowed to return to Crimea in the 1980s, where they now form a 12% minority. There remains a large diaspora of Crimean Tatars in Turkey and Uzbekistan.

Distribution

Main article: Crimean Tatar diasporaIn the latest Ukrainian census, 248,200 Ukrainian citizens identified themselves as Crimean Tatars with 98% (or about 243,400) of them living in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea. An additional 1,800 citizens (or about 0.7% of those that identified themselves as Crimean Tatars) live in the city of Sevastopol, also on the Crimean peninsula, but outside the border of the autonomous republic.

As of 2012, there are an estimated 500,000 Muslims in Ukraine and about 300,000 (or about 60%) of them identify themselves as Crimean Tatars.

About 150,000 remain in exile in Central Asia, mainly in Uzbekistan. The official number of Crimean Tatars in Turkey is 150,000 with some claims elevating the figure as high as 6,000,000, which would presumably indicate that all Turks could have at least some Crimean Tatar blood. They mostly live in Eskişehir Province, descendants of those who emigrated in the 19th and early 20th centuries. In the Dobruja region straddling Romania and Bulgaria, there are more than 27,000 Crimean Tatars: 24,000 on the Romanian side, and 3,000 on the Bulgarian side.

Sub-ethnic groups

The Crimean Tatars are subdivided into three sub-ethnic groups:

- the Tats (not to be confused with Tat people, living in the Caucasus region) who used to inhabit the mountainous Crimea before 1944 (about 55%),

- the Yalıboyu who lived on the southern coast of the peninsula (about 30%),

- the Noğay (not to be confused with Nogai people, living now in Southern Russia) – former inhabitants of the Crimean steppe (about 15%).

The Tats and Yalıboyus have a Caucasoid physical appearance, while the Noğays retain some Mongoloid physical appearance.

Historians suggest that the inhabitants of the mountainous parts of Crimea lying to the central and southern parts (the Tats), and those of the Southern coast of Crimea (the Yalıboyu) were the direct descendants of the Pontic Greeks, Armenians, Scythians, Ostrogoths (Crimean Goths) and Kipchaks along with the Cumans while the latest inhabitants of the northern steppe represent the descendants of the Nogai Horde of the Black Sea nominally subjects of the Crimean Khan. It is largely assumed that the Tatarization process that mostly took place in the 16th century brought a sense of cultural unity through the blending of the Greeks, Armenians, Italians and Ottoman Turks of the southern coast, Goths of the central mountains, and Turkic-speaking Kipchaks and Cumans of the steppe and forming of the Crimean Tatar ethnic group. However, the Cuman language is considered the direct ancestor of the current language of the Crimean Tatars with possible incorporations of the other languages like Crimean Gothic.

Another theory suggests Crimean Tatars trace their origins to the waves of ancient people Scythians, Greeks, Goths, Italians and Armenians. When the Golden Horde invaded Crimea in the 1230s, they then mixed with populations which had settled in Eastern Europe, including Crimea since the seventh century: Tatars, but also Mongols and other Turkic groups (Khazars, Pechenegs, Cumans, and Kipchacks), as well as the ancient.

History

Main article: History of CrimeaCrimean Khanate

Further information: Crimean Khanate

The Crimean Tatars emerged as a nation at the time of the Crimean Khanate, an Ottoman vassal state during the 15th to 18th centuries and one of the great centers of slave trade to the Ottoman Empire. The Turkic-speaking population of the Crimea had mostly adopted Islam already in the 14th century, following the conversion of Ozbeg Khan.

Slave trade

See also: Crimean-Nogai raids into East Slavic landsUntil the beginning of the 18th century, Crimean Tatars were known for frequent, at some periods almost annual, devastating raids into Ukraine and Russia. For a long time, until the late 18th century, the Crimean Khanate maintained a massive slave trade with the Ottoman Empire and the Middle East which was the most important basis of its economy. One of the most important trading ports and slave markets was Kefe. Slaves and freedmen formed approximately 75% of the Crimean population.

Some researchers estimate that altogether more than 2 million people, predominantly Ukrainians but also Russians, Belarusians and Poles, were captured and enslaved during the time of the Crimean Khanate in what was called "the harvest of the steppe". On the other hand, lands of Crimean Tatars were also being raided by Zaporozhian Cossacks, armed Slavic horsemen, who defended the steppe frontier – Wild Fields – against Tatar slave raids and often attacked and plundered the lands of Ottoman Turks and Crimean Tatars. The Don Cossacks and Kalmyk Mongols also managed to raid Crimean Tatars' land. The last recorded major Crimean raid, before those in the Russo-Turkish War (1768–74) took place during the reign of Peter the Great (1682–1725) However, Cossack raids continued after that time; Ottoman Grand Vizier complained to the Russian consul about raids to Crimea and Özi in 1761. In 1769 a last major Tatar raid, which took place during the Russo-Turkish War, saw the capture of 20,000 slaves.

In the Russian Empire

See also: Novorossiya

The Russo-Turkish War (1768–74) resulted in the defeat of the Ottomans by the Russians, and according to the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (1774) signed after the war, Crimea became independent and Ottomans renounced their political right to protect the Crimean Khanate. After a period of political unrest in Crimea, Russia violated the treaty and annexed the Crimean Khanate in 1783. After the annexation, under pressure of Slavic colonization, Crimean Tatars began to abandon their homes and move to the Ottoman Empire in continuing waves of emigration. Particularly, the Crimean War of 1853–1856, the laws of 1860–63, the Tsarist policy and the Russo-Turkish War (1877–78) caused an exodus of the Crimean Tatars. Of total Tatar population 300,000 of the Taurida Governorate about 200,000 Crimean Tatars emigrated. Many Crimean Tatars perished in the process of emigration, including those who drowned while crossing the Black Sea. Today the descendants of these Crimeans form the Crimean Tatar diaspora in Bulgaria, Romania and Turkey.

Ismail Gasprinski (1851–1914) was a renowned Crimean Tatar intellectual, whose efforts laid the foundation for the modernization of Muslim culture and the emergence of the Crimean Tatar national identity. The bilingual Crimean Tatar-Russian newspaper Terciman-Perevodchik he published in 1883–1914, functioned as an educational tool through which a national consciousness and modern thinking emerged among the entire Turkic-speaking population of the Russian Empire. His New Method (Usul-i Cedid) schools, numbering 350 across the peninsula, helped create a new Crimean Tatar elite. The educated "Crimean Tatars" during this period refused the appellation of "Tatars" given to them by the Turks (which however in earlier times had also been used natively). They wished to be known simply as "Turks", and their language as "Turkish" (the Crimean Tatar language had indeed been substantially influenced by Ottoman Turkish).

After the Russian Revolution of 1917 this new elite, which included Noman Çelebicihan and Cafer Seydamet proclaimed the first democratic republic in the Islamic world, named the Crimean People's Republic on 26 December 1917. However, this republic was short-lived and destroyed by the Bolshevik uprising in January 1918.

In the Soviet Union (1917–1991)

Main article: Deportation of the Crimean Tatars

During Stalin's Great Purge, statesmen and intellectuals such as Veli Ibraimov and Bekir Çoban-zade (1893–1937), were imprisoned or executed on various charges.

Soviet policies on the peninsula led to widespread starvation in 1921. More than 100,000 Tatars, Russians, Ukrainians and other inhabitants of the peninsula starved to death, and tens of thousands Tatars fled to Turkey or Romania. Thousands more were deported or slaughtered during the collectivization in 1928–29. The government campaign led to another famine in 1931–33. No other Soviet nationality suffered the decline imposed on the Crimean Tatars; between 1917 and 1933 half the Crimean Tatar population had been killed or deported.

During World War II, the entire Crimean Tatar population in Crimea fell victim to Soviet policies. Although a great number of Crimean Tatar men served in the Red Army and took part in the partisan movement in Crimea during the war, the existence of the Tatar Legion in the Nazi army and the collaboration of Crimean Tatar religious and political leaders with Hitler during the German occupation of Crimea provided the Soviets with a pretext for accusing the whole Crimean Tatar population of being Nazi collaborators. Some modern researchers argue that Crimea's geopolitical position fueled Soviet perceptions of Crimean Tartars as a potential threat. This belief is based in part on an analogy with numerous other cases of deportations of non-Russians from boundary territories, as well as the fact that other non-Russian populations, such as Greeks, Armenians and Bulgarians were also removed from Crimea.

All Crimean Tatars were deported en masse, in a form of collective punishment, on 18 May 1944 as "special settlers" to Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic and other distant parts of the Soviet Union. This event is called Sürgün in the Crimean Tatar language. Many of them were re-located to toil as indentured workers in the Soviet GULAG system.

Although a 1967 Soviet decree removed the charges against Crimean Tatars, the Soviet government did nothing to facilitate their resettlement in Crimea and to make reparations for lost lives and confiscated property. Crimean Tatars, having definite tradition of non-communist political dissent, succeeded in creating a truly independent network of activists, values and political experience. Crimean Tatars, led by Crimean Tatar National Movement Organization, were not allowed to return to Crimea from exile until the beginning of the Perestroika in the mid-1980s.

After Ukrainian independence

Today, more than 250,000 Crimean Tatars have returned to their homeland, struggling to re-establish their lives and reclaim their national and cultural rights against many social and economic obstacles. In 1991, the Crimean Tatar leadership founded the Qurultay, or Parliament, to act as a representative body for the Crimean Tatars which could address grievances to the Ukrainian central government, the Crimean government, and international bodies. Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar People is the executive body of the Qurultay.

Since the 1990s, the political leader of the Crimean Tatars and the chairman of the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar People is a former Soviet dissident Mustafa Abdülcemil Qırımoğlu.

2014 Crimean crisis

Main article: 2014 Crimean crisisFollowing news of Crimea's planned referendum on March 16, 2014, the Tatar population voiced concerns of renewed persecution, as commented by a US offical before the visit of a UN human rights team to the peninsula.

On March 18, It was announced that Crimean Tatars will be required to relinquish land that they hold and be given land elsewhere in Crimea. Crimea stated it needed the relinquished land for "Social purposes", since part of this land is occupied by the Crimean Tatars without legal documents of ownership. The situation was caused by the inability of the USSR (and later Ukraine) to give back to the Tatars the land owned before deportation, once they or their descendants returned from Siberia. As a consequence, Crimean Tatars settled in squatters, occupying land that was and is still not legally registered.

On 23 March 2014, Hundreds of Crimean Tatars fled to the most western city of Lviv, Ukraine due to the Crimean crisis.

On 29 March 2014, an emergency meeting of the Crimean Tatars representative body, the Kurultai, voted in favour of seeking "ethnic and territorial autonomy" for Crimean Tatars using "political and legal" means. The meeting was attended by the Head of the Republic of Tatarstan and the chair of the Russian Council of Muftis. Decisions as to whether the Tatars will accept Russian passports or whether the autonomy sought would be within the Russian or Ukrainian state have been deferred pending further discussion.

Gallery

| This section contains an unencyclopedic or excessive gallery of images. Please help improve the section by removing excessive or indiscriminate images or by moving relevant images beside adjacent text, in accordance with the Manual of Style on use of images. (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

-

Crimean Tatar woman, 1872

Crimean Tatar woman, 1872

-

Crimean Tatar children at school, by Carlo Bossoli, 1856

Crimean Tatar children at school, by Carlo Bossoli, 1856

-

Crimean Tatars in traditional costume, 1880

Crimean Tatars in traditional costume, 1880

-

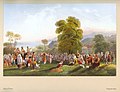

"Tatar dance," by Carlo Bossoli, 1856

"Tatar dance," by Carlo Bossoli, 1856

-

Tatar in battle with Pole.

Tatar in battle with Pole.

-

Devlet II Giray

Devlet II Giray

-

Skirmish with the Tatars.

Skirmish with the Tatars.

-

Crimean Khan

Crimean Khan

-

Bohdan Khmelnytsky Cossacks meets crimean Cavalry

Bohdan Khmelnytsky Cossacks meets crimean Cavalry

-

Cavalry battle with the Tatars

Cavalry battle with the Tatars

-

Crimean Tatar women

Crimean Tatar women

See also

- Index of articles related to Crimean Tatars

- Turkic peoples

- Tatarstan

- Tatars

- Nogais

- Baibars

- Crimean tatar legends

Notes

Claimed by Russian Federation as Crimean Federal District: Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol federal city. Internationally recognized as a part of Ukraine as Autonomous Republic of Crimea, Sevastopol city and part of Kherson Oblast

References

- 2001 Ukrainian census for the Autonomous Republic of Crimea

- Template:Ru icon 1989 Soviet census – Uzbekistan

- ^ Crimean Tatars and Noghais in Turkey

- "Recensamant Romania 2002". Agentia Nationala pentru Intreprinderi Mici si Mijlocii (in Romanian). 2002. Retrieved 5 August 2007.

- Russian Census 2010: Population by ethnicity Template:Ru icon

- Bulgaria Population census 2001

- Template:Ru icon Агентство Республики Казахстан по статистике. Перепись 2009. (Национальный состав населения.rar)

- ^ "About number and composition population of UKRAINE by data All-Ukrainian population census'". Ukrainian Census (2001). State Statistics Committee of Ukraine. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- "About number and composition population of AUTONOMOUS REPUBLIC OF CRIMEA by data All-Ukrainian population census'". Ukrainian Census (2001). State Statistics Committee of Ukraine. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- "2012 Report on International Religious Freedom - Ukraine". United States Department of State. 20 May 2013. Retrieved 16 December 2013.

- "The Crimean Tatars: The Diaspora Experience and the Forging of a Nation". Iccrimea.org. 18 May 1944. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- Khodarkovsky – Russia's Steppe Frontier p. 11

- Williams, BG. The Crimean Tatars: The Diaspora Experience and the Forging of a Nation. Pgs 7–23. ISBN 90-04-12122-6

- István Vásáry (2005) Cumans and Tatars, Cambridge University Press.

- Stearns(1979:39–40).

- "CUMAN". Christusrex.org. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- Stearns (1978). "Sources for the Krimgotische". p. 37. Retrieved 12 February 2011.

- The Crimean Tatars: The Diaspora Experience and the Forging of a Nation. By Brian Glyn Williams

- Autonomy, Self Governance and Conflict Resolution: Innovative approaches, By Marc Weller

- Williams, BG. The Crimean Tatars: The Diaspora Experience and the Forging of a Nation. Pg 12. ISBN 90-04-12122-6

- ^ "The Crimean Tatars and their Russian-Captive Slaves" (PDF). Eizo Matsuki, Mediterranean Studies Group at Hitotsubashi University.

- ^ Mikhail Kizilov. "Slave Trade in the Early Modern Crimea From the Perspective of Christian, Muslim, and Jewish Sources". Oxford University. pp. 2–7.

- Slavery. Encyclopædia Britannica's Guide to Black History.

- Andrew G. Boston (18 April 2005). "Black Slaves, Arab Masters". Frontpage Magazine. Retrieved 8 January 2011.

- Darjusz Kołodziejczyk, as reported by Mikhail Kizilov (2007). "Slaves, Money Lenders, and Prisoner Guards:The Jews and the Trade in Slaves and Captivesin the Crimean Khanate". The Journal of Jewish Studies. p. 2.

- ^ Alan W. Fisher, The Russian Annexation of the Crimea 1772–1783, Cambridge University Press, p. 26.

- Brian Glyn Williams (2013). "The Sultan's Raiders: The Military Role of the Crimean Tatars in the Ottoman Empire" (PDF). The Jamestown Foundation.

- "Hijra and Forced Migration from Nineteenth-Century Russia to the Ottoman Empire", by Bryan Glynn Williams, Cahiers du Monde russe, 41/1, 2000, pp. 79–108.

- E. J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913-1936, Volume 4, pp. 1084f.

- Maria Drohobycky, Crimea: Dynamics, Challenges and Prospects, Rowman & Littlefield, 1995, p.91, ISBN 0847680673

- ^ Europe, many nations: a historical dictionary of European national groups, James Minahan, page 189, 2000

- Aurélie Campana, Sürgün: "The Crimean Tatars’ deportation and exile, Online Encyclopedia of Mass Violence", 16 June 2008. Retrieved 19 April 2012, ISSN 1961-9898

- Subtelny, Orest (2000). Ukraine: A History. University of Toronto Press. p. 483. ISBN 0-8020-8390-0.

- The Muzhik & the Commissar, TIME Magazine, 30 November 1953

- Buttino, Marco (1993). In a Collapsing Empire: Underdevelopment, Ethnic Conflicts and Nationalisms in the Soviet Union, p.68 ISBN 88-07-99048-2

- Abdulganiyev, Kurtmolla (2002). Institutional Development of the Crimean Tatar National Movement, International Committee for Crimea. Retrieved on 2008-03-22

- Ziad, Waleed (20 February 2007). "A Lesson in Stifling Violent Extremism: Crimea's Tatars have created a promising model to lessen ethnoreligious conflict". CS Monitor. Retrieved 6 August 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - "U.N. human rights team aims for quick access to Crimea - official". Retrieved 20 March 2014.

- Temirgaliyev, Rustam. "Crimean Deputy Prime Minister". Retrieved 19 March 2014.

- Trukhan, Vassyl. "Crimea's Tatars flee for Ukraine far west". Yahoo. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/03/29/us-ukraine-crisis-crimea-tatars-idUSBREA2S09320140329

- http://www.skynews.com.au/world/article.aspx?id=962589

Literature

- Campana (Aurélie), Dufaud (Grégory) and Tournon (Sophie) (ed.), Les Déportations en héritage. Les peuples réprimés du Caucase et de Crimée, hier et aujourd'hui, Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2009.

- Conquest, Robert. 1970. The Nation Killers: The Soviet Deportation of Nationalities (London: Macmillan). (ISBN 0-333-10575-3)

- Fisher, Alan W. 1978. The Crimean Tatars. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press. (ISBN 0-8179-6661-7)

- Fisher, Alan W. 1998. Between Russians, Ottomans and Turks: Crimea and Crimean Tatars (Istanbul: Isis Press, 1998). (ISBN 975-428-126-2)

- Nekrich, Alexander. 1978. The Punished Peoples: The Deportation and Fate of Soviet Minorities at the End of the Second World War (New Yk: W. W. Norton). (ISBN 0-393-00068-0)

- Template:Ru icon Valery Vozgrin "Исторические судьбы крымских татар"

- Uehling, Greta (June 2000). "Squatting, self-immolation, and the repatriation of Crimean Tatars". Nationalities Papers. 28 (2): 317–341. doi:10.1080/713687470.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|quotes=,|laydate=,|laysource=, and|laysummary=(help)

- Williams, Brian G., The Crimean Tatars: The Diaspora Experience and the Forging of a Nation, Leyden: Brill, 2001.

External links

- Official website of Qirim Tatar Cultural Association of Canada

- Official web-site of Bizim QIRIM International Nongovernmental Organization

- International Committee for Crimea

- UNDP Crimea Integration and Development Programme

- Crimean Tatar Home Page

- Crimean Tatars

- Crimean Tatar words (Turkish)

- Crimean Tatar words (English)

- State Defense Committee Decree No. 5859ss: On Crimean Tatars (See also Three answers to the Decree No. 5859ss)

- Crimean Tatars

| Turkic peoples | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peoples |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Others | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Diasporas | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Central Asian (i.e. Turkmeni, Afghani and Iranian) Turkmens, distinct from Levantine (i.e. Iraqi and Syrian) Turkmen/Turkoman minorities, who mostly adhere to an Ottoman-Turkish heritage and identity. In traditional areas of Turkish settlement (i.e. former Ottoman territories). | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Muslims in Europe | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Majority |

| ||||||||||||

| Minority | |||||||||||||