| Revision as of 15:30, 3 May 2015 editTobby72 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users37,824 edits reliably sourced content← Previous edit | Revision as of 16:05, 3 May 2015 edit undoToddy1 (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers48,714 edits Undid revision 660599976 by Tobby72 (talk) content not relevant to the subject of the articleNext edit → | ||

| Line 47: | Line 47: | ||

| Amid tensions with Russia, Kiev is not tolerating any other points of view in the press. Under the impact of war and extreme social polarization, the democratic credentials of the pro-European Kiev government have been slipping as well. A crackdown on what authorities describe as “pro-separatist” points of view has triggered dismay among Western human rights monitors. For example, the September 11, 2014 shutdown of the independent Kiev-based Vesti newspaper by the Ukrainian Security Service for “violating Ukraine’s territorial integrity” brought swift condemnation from the international Committee to Protect Journalists and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe.<ref name=":02">{{Cite web|url = http://www.csmonitor.com/World/Europe/2014/0921/Crackdown-in-Ukraine-sullies-its-democratic-aspirations|title = Crackdown in Ukraine sullies its democratic aspirations|date = September 21, 2014|accessdate = |website = The Christian Science Monitor|publisher = |last = |first = }}</ref> | Amid tensions with Russia, Kiev is not tolerating any other points of view in the press. Under the impact of war and extreme social polarization, the democratic credentials of the pro-European Kiev government have been slipping as well. A crackdown on what authorities describe as “pro-separatist” points of view has triggered dismay among Western human rights monitors. For example, the September 11, 2014 shutdown of the independent Kiev-based Vesti newspaper by the Ukrainian Security Service for “violating Ukraine’s territorial integrity” brought swift condemnation from the international Committee to Protect Journalists and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe.<ref name=":02">{{Cite web|url = http://www.csmonitor.com/World/Europe/2014/0921/Crackdown-in-Ukraine-sullies-its-democratic-aspirations|title = Crackdown in Ukraine sullies its democratic aspirations|date = September 21, 2014|accessdate = |website = The Christian Science Monitor|publisher = |last = |first = }}</ref> | ||

| The Ukrainian Security Service (SBU) broke into the office of a Kiev-based digital newspaper “Vesti”, physically trapping reporters and ultimately shutting down the website. | The Ukrainian Security Service (SBU) broke into the office of a Kiev-based digital newspaper “Vesti”, physically trapping reporters and ultimately shutting down the website. | ||

| Vesti News's editor-in-chief Igor Guzhva wrote on his Facebook page that the news outlet had been raided by SBU. The SBU reportedly took all servers, kept staffers in a "hot corridor" and shut down the website completely. Guzhva said that the purpose of the raid was "to block our work.". “Journalists are not being let into their office," Guzhva wrote. "Those who were already inside at the moment of the raid are being kept in the building and are not allowed to use cell phones.” | Vesti News's editor-in-chief Igor Guzhva wrote on his Facebook page that the news outlet had been raided by SBU. The SBU reportedly took all servers, kept staffers in a "hot corridor" and shut down the website completely. Guzhva said that the purpose of the raid was "to block our work.". “Journalists are not being let into their office," Guzhva wrote. "Those who were already inside at the moment of the raid are being kept in the building and are not allowed to use cell phones.” | ||

| Line 57: | Line 57: | ||

| In 2014 Ukraine blocked 14 Russian television channels from its cable networks.<ref>, Natalia Zinets, Reuters, 19 August 2014.</ref> | In 2014 Ukraine blocked 14 Russian television channels from its cable networks.<ref>, Natalia Zinets, Reuters, 19 August 2014.</ref> | ||

| On 10 February 2015, ] reported that an Ukrainian journalists called ] was jailed by Ukrainian authorities for 15 years for "treason and obstructing the military" in reaction to his statement that he would rather go to prison than be drafted by Ukrianian Army. Amnesty International has appealed to Ukrainian authorities to free him immediately and declared Kotsaba a ]. Tetiana Mazur, director of Amnesty International in Ukraine stated that "the Ukrainian authorities are violating the key human right of freedom of thought, which Ukrainians stood up for on the Maidan” .In response Ukrainian SBU declared that they have found “evidence of serious crimes” but declined to elaborate.<ref>"". ''The Guardian.'' 10 February 2015.</ref> | |||

| ===Rankings=== | ===Rankings=== | ||

Revision as of 16:05, 3 May 2015

Column-generating template families

The templates listed here are not interchangeable. For example, using {{col-float}} with {{col-end}} instead of {{col-float-end}} would leave a<div>...</div> open, potentially harming any subsequent formatting. | Type | Family | Handles wiki table code? | Responsive/ mobile suited | Start template | Column divider | End template |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Float | "col-float" | Yes | Yes | {{col-float}} | {{col-float-break}} | {{col-float-end}} |

| "columns-start" | Yes | Yes | {{columns-start}} | {{column}} | {{columns-end}} | |

| Columns | "div col" | Yes | Yes | {{div col}} | – | {{div col end}} |

| "columns-list" | No | Yes | {{columns-list}} (wraps div col) | – | – | |

| Flexbox | "flex columns" | No | Yes | {{flex columns}} | – | – |

| Table | "col" | Yes | No | {{col-begin}}, {{col-begin-fixed}} or {{col-begin-small}} | {{col-break}} or {{col-2}} .. {{col-5}} | {{col-end}} |

{| | || |- |} used to create tables? If not, special templates that produce these elements (such as {{(!}}, {{!}}, {{!!}}, {{!-}}, {{!)}})—or HTML tags (<table>...</table>, <tr>...</tr>, etc.)—need to be used instead.Freedom of the press in Ukraine was considered in 2013 to be among the freest of the post-Soviet states other than the Baltic states.

As of December 2014, Freedom House classifies the Internet in Ukraine as "free" and the press as "not free". Press freedom had significantly improved since the Orange Revolution of 2004. However, in 2010 Freedom House perceived "negative trends in Ukraine".

According to the US Department of State in 2009 there were no attempts by central authorities to direct media content, but there were reports of intimidation of journalists by national and local officials. Media at times demonstrated a tendency toward self‑censorship on matters that the government deemed sensitive. Stories in the electronic and printed media (veiled advertisements and positive coverage presented as news) and participation in a television talk show can be bought. Media watchdog groups have express concern over the extremely high monetary damages that were demanded in court cases concerning libel.

The Constitution of Ukraine and a 1991 law provide for freedom of speech.

In Ukraine’s provinces numerous, anonymous attacks and threats persisted against journalists, who investigated or exposed corruption or other government misdeeds. The US-based Committee to Protect Journalists concluded in 2007 that these attacks, and police reluctance in some cases to pursue the perpetrators, were “helping to foster an atmosphere of impunity against independent journalists.” Media watchdogs have stated attacks and pressure on journalists have increased since the February 2010 election of Viktor Yanukovych as President.

In Ukraine many news-outlets are financed by wealthy investors and reflected the political and economic interests of their owners.

History

After the (only) term of office of the first Ukrainian President Leonid Kravchuk ended in 1994, the freedom of the press worsened. During the presidency of Leonid Kuchma (1994–2004) several news-outlets critical to the him were forcefully closed. In 1999 the Committee to Protect Journalists placed Kuchma on the list of worst enemy's of the press. In that year the Ukrainian Government partially limited freedom of the press through tax inspections (Mykola Azarov, who later became Prime Minister of Ukraine, headed the tax authority during Kuchma's presidency), libel cases, subsidization, and intimidation of journalists; this caused many journalists to practice self-censorship. In 2003 and 2004 authorities interfered with the media by issuing written and oral instructions about what events to cover. Toward the very end of the 2004 Ukrainian presidential election campaign in November 2004, many media outlets began to ignore government direction and covered events in a more objective, professional manner.

Since the Orange Revolution (of 2004) Ukrainian media has become more pluralistic and independent. For instance, attempts by authorities to limit freedom of the press through tax inspections have ceased. Since then the Ukrainian press is considered to be among the freest of all post-Soviet states (only the Baltic states are considered "free").

Latest developments

In December 2009 during the 2010 Ukrainian presidential election campaign incumbent Prime Minister of Ukraine and presidential candidate Yulia Tymoshenko complained Ukrainian TV channels are manipulating the consciousness of citizens in favor of financial and oligarchic groups.

In Spring 2010 Ukrainian journalists, the European Federation of Journalists and Reporters Without Borders all complained of censorship by President Yanukovych's administration. This despite statements by Yanukovych how deeply he values press freedom and that ‘free, independent media that must ensure society’s unimpeded access to information’. Anonymous journalists stated early May 2010 that they were voluntarily tailoring their coverage so as not to offend the Yanukovych administration and the Azarov Government. The Azarov Government denies censoring the media, so did the Presidential Administration and President Yanukovych himself. Presidential Administration Deputy Head Hanna Herman stated on May 13, 2010 that the opposition benefited from discussions about the freedom of the press in Ukraine and also suggested that the recent reaction of foreign journalists organizations had been provoked by the opposition. On May 12, 2010, the parliamentary committee for freedom of speech and information called on the General Prosecutor's Office to immediately investigate complaints by journalists of pressure on journalists and censorship.

A law on strengthening the protection of the ownership of mass media offices, publishing houses, bookshops and distributors, as well as creative unions was passed by the Ukrainian Parliament on May 20, 2010.

Since the February 2010 election of Viktor Yanukovych as President Media watchdogs have stated attacks and pressure on journalists have increased. The International Press Institute addressed an open letter to President Yanukovych on August 10, 2010 urging him to address what the organisation saw as a disturbing deterioration in press freedom over the previous six months in Ukraine. PACE rapporteur Renate Wohlwend noticed on October 6, 2010 that "Some progress had been made in recent years but there had also been some retrograde steps". In January 2011 Freedom House stated it had perceived "negative trends in Ukraine" during 2010; these included: curbs on press freedom, the intimidation of civil society, and greater government influence on the judiciary.

The ongoing crisis in Ukraine has resulted in a major threat to press freedom in recent months. A May report from the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) found approximately 300 instances of violent attacks on the media in Ukraine since November 2013.

Amid tensions with Russia, Kiev is not tolerating any other points of view in the press. Under the impact of war and extreme social polarization, the democratic credentials of the pro-European Kiev government have been slipping as well. A crackdown on what authorities describe as “pro-separatist” points of view has triggered dismay among Western human rights monitors. For example, the September 11, 2014 shutdown of the independent Kiev-based Vesti newspaper by the Ukrainian Security Service for “violating Ukraine’s territorial integrity” brought swift condemnation from the international Committee to Protect Journalists and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe.

The Ukrainian Security Service (SBU) broke into the office of a Kiev-based digital newspaper “Vesti”, physically trapping reporters and ultimately shutting down the website.

Vesti News's editor-in-chief Igor Guzhva wrote on his Facebook page that the news outlet had been raided by SBU. The SBU reportedly took all servers, kept staffers in a "hot corridor" and shut down the website completely. Guzhva said that the purpose of the raid was "to block our work.". “Journalists are not being let into their office," Guzhva wrote. "Those who were already inside at the moment of the raid are being kept in the building and are not allowed to use cell phones.”

Guzhva said that this is the second time in just six months that the SBU has tried to "intimidate" its editors. He added that he is unsure of the reason for the raid, but suspects that it might have to do with a story the website recently published on the SBU chief's daughter.

Ukraine has also shut down most Russia-based television stations on the grounds that they purvey “propaganda,” and barred a growing list of Russian journalists from entering the country.

Main article: Ministry of Truth (Ukraine)The Ministry of Information Policy was established on 2 December 2014. It was created concurrently with the formation of the Second Yatsenyuk Government, after the October 2014 Ukrainian parliamentary election. The ministry oversees information policy in Ukraine. According to the first Minister of Information, Yuriy Stets, one of the goals of its formation was to counteract "Russian information aggression" amidst pro-Russian unrest across Ukraine, and the ongoing war in the Donbass region. Ukrainian president Petro Poroshenko said that the main function of the ministry is to stop "the spreading of biased information about Ukraine".

In 2014 Ukraine blocked 14 Russian television channels from its cable networks.

Rankings

The report Freedom in the World (by Freedom House) rated Ukraine "partly free" since/from 1992 till 2003, when it was rated "not free". Since 2005 it is rated "partly free" again. According to Freedom House internet in Ukraine is "Free" and the press is "Partly Free".

Ukraine's ranking in Reporters Without Borders´s Press Freedom Index has long been around the 90th spot (89 in 2009, 87 in 2008), while it occupied the 112th spot in 2002 and even the 132nd spot in 2004. In 2010 it fell to the 131st place; according to Reporters Without Borders this was the result of "the slow and steady deterioration in press freedom since Viktor Yanukovych’s election as president in February". In 2013 Ukraine occupied the 126th spot (dropping 10 places compared with 2012); (according to Reporters Without Borders) "the worst record for the media since the Orange Revolution in 2004". In the 2014 World Press Freedom Index Ukraine was placed 127th.

Popular opinion

During an opinion poll by Research & Branding Group in October 2009 49.2% of the respondents stated that Ukraine's level of freedom of speech was sufficient, and 19.6% said the opposite. Another 24.2% said that there was too much of freedom of speech in Ukraine. According to the data, 62% of respondents in western Ukraine considered the level of freedom of speech sufficient, and in the central and southeastern regions the figures were 44% and 47%, respectively.

In a late 2010 poll also conducted by the Research & Branding Group 56% of all Ukrainians trusted the media and 38.5% didn't.

Timeline of reporters killed in Ukraine

Under former President Leonid Kuchma opposition papers were closed and several journalists died in mysterious circumstances. Template:Timeline of reporters killed in Ukraine

See also

- Human rights in Ukraine

- Internet censorship and surveillance in Ukraine

- List of newspapers in Ukraine

- Media of Ukraine

- Telecommunications in Ukraine

- Television in Ukraine

Notes

- The Baltic states are the only post-Soviet states that Freedom House considers "free". Next to Ukraine Freedom House considers also to be "partly free" Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Georgia, Abkhazia, Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh.

References

- "Press Freedom Index 2014", Reporters Without Borders, 11 May 2014

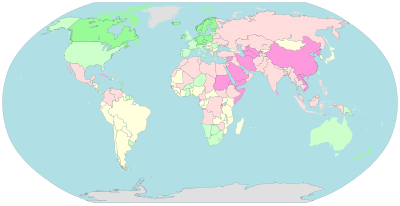

- ^ Map of Press Freedom 2010, Freedom House

- ^ Map of Press Freedom 2009, Freedom House

Map of Freedom (of the Freedom in the World 2013 survey), Freedom House - ^ Ukraine (Country Guide) by Sarah Johnstone and Greg Bloom, Lonely Planet, 2008, ISBN 978-1-74104-481-2 (page 39)

- ^ Freedom of the Press 2007: A Global Survey of Media Independence by Freedom House, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc, 2007, ISBN 978-0-7425-5582-2 (page 11/12)

- ^ Ukraine, Freedom House

- ^ CIS: Press Freedom In Former Soviet Union Under Assault, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (April 28, 2006 )

- ^ 2006 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Ukraine, US Department of State (March 6, 2007)

- ^ Report Says Decline In Freedom Continues Across Former Soviet Union, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (January 13, 2011)

- ^ 2009 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Ukraine, US Department of State (March 11, 2010)

- ^ 2008 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Ukraine, US Department of State (February 25, 2009)

- ^ 1999 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Ukraine, US Department of State (February 23, 2000)

- Local newspaper editor badly injured in assault, Reporters Without Borders (March 31, 2010)

- Disturbing deterioration in press freedom situation since new president took over, Reporters Without Borders (April 15, 2010)

- Media crackdown under way?, Kyiv Post (April 22, 2010)

- HRW

- HRW

- ^ Concerns Mount About Press Freedom In Ukraine As Journalist Attacked, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (September 21, 2010)

- Ukraine At A Crossroads (Interdisciplinary Studies on Central and Eastern Europe) (v. 1) by Andrej Lushnycky and Nicolas Hayoz, Peter Lang Publishing, 2005, ISBN 978-3-03910-468-0 (page 21)

- ^ Nations in Transit 2000-2001 by Adrian Karatnycky, Alexander Motyl, and Amanda Schnetzer, Transaction Publishers, 2001, ISBN 978-0-7658-0897-4 (page 397)

- Biography of new Ukrainian Prime Minister Mykola Azarov, RIA Novosti (March 11, 2010)

- Mykola Azarov: Yanukovych's Right-Hand Man, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (March 12, 2010)

- ^ 2003 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Ukraine, US Department of State (February 25, 2004)

- ^ 2004 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Ukraine, US Department of State (February 28, 2005)

- 2000 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Ukraine, US Department of State (February 23, 2001)

- 2001 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Ukraine, US Department of State (March 4, 2002)

- 2002 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Ukraine, US Department of State (March 31, 2003)

- 2005 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Ukraine, US Department of State (March 8, 2006)

- More women than men support Tymoshenko, poll shows, Kyiv Post (December 7, 2009)

- Tymoshenko accuses central TV channels of manipulating people's consciousness in favor of oligarchs, Kyiv Post (December 8, 2009)

- ^ 1+1 TV journalists claim censorship of news reports, Kyiv Post (May 6, 2009)

- STB TV channel journalists claim imposing of censorship on STB, Kyiv Post (May 8, 2009)

- European journalists call on Ukrainian authorities, media owners to respect press freedom, Kyiv Post (May 11, 2009)

- Journalists, in defensive crouch, swing news coverage to Yanukovych’s favor, Kyiv Post (May 6, 2009)

- Semynozhenko: No examples of censorship on Ukrainian TV channels, Kyiv Post (May 13, 2009)

- ^ Opposition benefiting from topic of censorship at mass media, says Hanna Herman, Kyiv Post (May 13, 2009)

- Template:Uk icon Янукович: Україна готова, якщо Європа готова, BBC Ukrainian (May 10, 2010)

- Special committee calls to check reports of pressure on journalists, Kyiv Post (May 13, 2009)

- Parliament bans forced removal of state and municipal mass media offices, Kyiv Post (May 21, 2009)

- International Press Institute: Ukraine's press freedom environment has deteriorated 'signficiantly', Kyiv Post (August 11, 2010)

- European rapporteurs note media setback in Ukraine, Kyiv Post (October 6, 2010)

- "Ukraine media freedom under attack: OSCE". Reuters. May 23, 2014.

- ^ "Crackdown in Ukraine sullies its democratic aspirations". The Christian Science Monitor. September 21, 2014.

- "Ukraine Security Services Break Into Newspaper Office, Shut Down Website". Huff Post Media. November 9, 2014.

- "Міністр інформаційної політики України" (Press release). Supreme Council of Ukraine. 2 December 2014. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- ^ Rada supports coalition-proposed government lineup, Interfax-Ukraine (2 December 2014)

Rada approves new Cabinet with three foreigners, Kyiv Post (2 December 2014)

Template:Uk icon Rada voted the new Cabinet, Ukrayinska Pravda (2 December 2014) - Ukraine must establish Information Policy Ministry , National Radio Company of Ukraine (2 December 2014)

- Poroshenko: Information Ministry's main task is to repel information attacks against Ukraine, Interfax-Ukraine (8 December 2014)

- "Ukraine bans Russian TV channels for airing war 'propaganda' ", Natalia Zinets, Reuters, 19 August 2014.

- Map of Press Freedom 2004, Freedom House

- Press Freedom Index 2009, Reporters Without Borders

- Press Freedom Index 2008, Reporters Without Borders

- Press Freedom Index 2002, Reporters Without Borders

- Press Freedom Index 2004, Reporters Without Borders

- Press Freedom Index 2010, Reporters Without Borders

- Press Freedom Index 2013, Reporters Without Borders

- Ukraine takes 127th place in rating of freedom of speech, Ukraine Today (12 January 2014)

- Half of all Ukrainians consider current freedom of speech level sufficient, Kyiv Post (October 15, 2009)

- Poll: More than half of Ukrainians trust the media, Kyiv Post (December 17, 2010)

- Country profile: Ukraine, BBC News

External links

| Freedom of the press in Europe | |

|---|---|

| Sovereign states |

|

| States with limited recognition | |

| Dependencies and other entities | |

| Other entities | |