| Revision as of 21:53, 17 February 2018 editKnutsokl (talk | contribs)7 edits added updates and citationsTag: Visual edit← Previous edit | Revision as of 06:15, 6 March 2018 edit undoAyeolaWhitworth2 (talk | contribs)1 edit I added information about Rosa Bonheur's gender expression and lesbian identity along with sources to backup such claims.Next edit → | ||

| Line 47: | Line 47: | ||

| Bonheur can be viewed as a "]" of the 19th century; she was known for ],<ref>Britta C. Dwyer, “Bridging the gap of difference: Anna Klumpke's “union” with Rosa Bonheur”, Out of context. (New York: Greenwood Press, 2004), p. 69-79.; Laurel Lampela, “Daring to be different: a look at three lesbian artists”, Art Education v.54 no. 2 (March 2001), p. 45-51. and Gretchen Van Slyke, “The sexual and textual politics of dress: Rosa Bonheur and her cross-dressing permits”, Nineteenth-Century French Studies v. 26 no. 3-4 (Spring/Summer 1998) p. 321-35.</ref> but she attributed her choice of trousers to their practicality for working with animals (see ]).<ref>Janson: ''History of Art'', page 929</ref> | Bonheur can be viewed as a "]" of the 19th century; she was known for ],<ref>Britta C. Dwyer, “Bridging the gap of difference: Anna Klumpke's “union” with Rosa Bonheur”, Out of context. (New York: Greenwood Press, 2004), p. 69-79.; Laurel Lampela, “Daring to be different: a look at three lesbian artists”, Art Education v.54 no. 2 (March 2001), p. 45-51. and Gretchen Van Slyke, “The sexual and textual politics of dress: Rosa Bonheur and her cross-dressing permits”, Nineteenth-Century French Studies v. 26 no. 3-4 (Spring/Summer 1998) p. 321-35.</ref> but she attributed her choice of trousers to their practicality for working with animals (see ]).<ref>Janson: ''History of Art'', page 929</ref> | ||

| Bonheur did not live the stereotypical life of a woman of her time. Most things women did, Bonheur rebelled against. She was one of very few women, around twenty, who wore pants at the time. She had to get a permit to wear pants and women without such permits were likely to be arrested. In fact, Rosa was once almost arrested by a policeman who mistakenly saw her as a transvestite, which was illegal at the time. In a world where gender expression was literally policed, Rosa Bonheur broke boundaries by deciding to wear pants, shirts and ties. She did not do this because she wanted to be a man, though she occasionally referred to herself as a grandson or brother when talking about her family, rather Bonheur identified with the power and freedom reserved for men. Wearing men's clothing gave Bonheur a sense of identity in that it allowed her to openly show that she refused to conform to societies social construction of the gender binary. It also broadcasted her sexuality in a time where the lesbian stereotype consisted of women who cut their hair short, wore pants, and chain-smoked. Rosa Bonheur did all three. Bonheur never explicitly expressed she was a lesbian but her lifestyle and the way she talked about her female partners suggests this. She had two female partners in her lifetime, the first she grew up with and then lived with for forty years. She even decided to allocate all of her possessions to her first partner, Natalie, in the off chance that she should die before Natalie. Sadly, Natalie passed before Bonheur. Bonheur ended up taking on a new housemate, Anne. Bonheur, while taking pleasure in activities usually reserved for men, such as hunting and smoking, viewed her womanhood as something far superior to anything a man could offer or experience. She viewed men as stupid and mentioned that the only males she had time or attention for were the bulls she painted. Bonheur’s lesbian identity bled into her lifestyle in numerous ways. The most prevalent of which was her choice to never become an adjunct or appendage to a man in terms of painting. She decided she would be her own boss and that she could lean on herself and her female partners instead. She had her partners focus on the home life while she took on the role of breadwinner by focusing on her painting. Bonheur's legacy paved the way for other lesbian artists who didn't favour the life society laid out for them. | |||

| ] | ] | ||

Revision as of 06:15, 6 March 2018

| Rosa Bonheur | |

|---|---|

Photograph of Rosa Bonheur by André Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri, c. 1863 Photograph of Rosa Bonheur by André Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri, c. 1863 | |

| Born | Marie-Rosalie Bonheur (1822-03-16)16 March 1822 Bordeaux, France |

| Died | 25 May 1899(1899-05-25) (aged 77) Thomery, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Known for | Painting, sculpture |

| Notable work | Ploughing in the Nivernais, The Horse Fair |

| Movement | Realism |

Rosa Bonheur, born Marie-Rosalie Bonheur, (16 March 1822 – 25 May 1899) was a French artist, an animalière (painter of animals) and sculptor, known for her artistic realism. Her most well-known paintings are Ploughing in the Nivernais, first exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1848, and now at Musée d’Orsay in Paris, and The Horse Fair (in French: Le marché aux chevaux), which was exhibited at the Salon of 1853 (finished in 1855) and is now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in New York City. Bonheur was widely considered to be the most famous female painter during the nineteenth century.

Early development and artistic training

Bonheur was born on 16 March 1822 in Bordeaux, Gironde, the oldest child in a family of artists. Her mother was Sophie Bonheur (née Marquis), a piano teacher; she died when Rosa Bonheur was eleven. Her father was Oscar-Raymond Bonheur, a landscape and portrait painter who encouraged his daughter's artistic talents. The Bonheur family adhered to Saint-Simonianism, a Christian-socialist sect that promoted the education of women alongside men. Bonheur's siblings included the animal painters Auguste Bonheur and Juliette Bonheur and the animal sculptor Isidore Jules Bonheur. Francis Galton used the Bonheurs as an example of "Hereditary Genius" in his 1869 essay of the same title.

Bonheur moved to Paris in 1828 at the age of six with her mother and siblings, her father having gone ahead of them to establish a residence and income. By family accounts, she had been an unruly child and had a difficult time learning to read, though even before she could talk she would sketch for hours at a time with pencil and paper. Her mother taught her to read and write by asking her to choose and draw a different animal for each letter of the alphabet. The artist credits her love of drawing animals to these reading lessons with her mother.

At school she was often disruptive, and she was expelled from numerous schools. After a failed apprenticeship with a seamstress at the age of twelve, her father undertook to train her as a painter. Her father allowed her to pursue her interest in painting animals by bringing live animals to the family's studio for studying.

Following the traditional art school curriculum of the period, Bonheur began her training by copying images from drawing books and by sketching plaster models. As her training progressed, she made studies of domesticated animals, including horses, sheep, cows, goats, rabbits and other animals in the pastures on the perimeter of Paris, the open fields of Villiers near Levallois-Perret, and the still-wild Bois de Boulogne. At fourteen, she began to copy paintings at the Louvre. Among her favorite painters were Nicholas Poussin and Peter Paul Rubens, but she also copied the paintings of Paulus Potter, Frans Pourbus the Younger, Louis Léopold Robert, Salvatore Rosa and Karel Dujardin.

She studied animal anatomy and osteology in the abattoirs of Paris and by dissecting animals at the École nationale vétérinaire d'Alfort, the National Veterinary Institute in Paris. There she prepared detailed studies that she later used as references for her paintings and sculptures. During this period, she befriended father-and-son comparative anatomists and zoologists, Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire and Isidore Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire.

Early success

A French government commission led to Bonheur's first great success, Ploughing in the Nivernais, exhibited in 1849. Her most famous work, the monumental Horse Fair, measured eight feet high by sixteen feet wide, and was completed in 1855. It depicts the horse market held in Paris, on the tree-lined boulevard de l’Hôpital, near the Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital, which is visible in the painting's background. This work led to international fame and recognition; that same year she traveled to Scotland and met Queen Victoria en route, who admired Bonheur's work. In Scotland, she completed sketches for later works including Highland Shepherd, completed in 1859, and A Scottish Raid, completed in 1860. These pieces depicted a way of life in the Scottish highlands that had disappeared a century earlier, and they had enormous appeal to Victorian sensibilities. Though she was more popular in England than in her native France, she was decorated with the French Legion of Honour by the Empress Eugénie in 1865, and was promoted to Officer of the order in 1894. She was the first female artist to be given this award.

Patronage and the market for her work

Art dealer Ernest Gambart (1814–1902) represented her; he brought Bonheur to the United Kingdom in 1855, and he purchased the reproduction rights to her work. Many engravings of Bonheur's work were created from reproductions by Charles George Lewis (1808–1880), one of the finest engravers of the day.

Legacy

Women were often only reluctantly educated as artists in Bonheur's day, and by becoming such a successful artist she helped to open doors to women artists that followed her.

Bonheur can be viewed as a "New Woman" of the 19th century; she was known for wearing men's clothing, but she attributed her choice of trousers to their practicality for working with animals (see Rational dress).

Bonheur did not live the stereotypical life of a woman of her time. Most things women did, Bonheur rebelled against. She was one of very few women, around twenty, who wore pants at the time. She had to get a permit to wear pants and women without such permits were likely to be arrested.Daring to Be Different: A Look at Three Lesbian Artists In fact, Rosa was once almost arrested by a policeman who mistakenly saw her as a transvestite, which was illegal at the time. THE CASE OF ROSA BONHEUR: WHY SHOULD A WOMAN WANT TO BE MORE LIKE A MAN?In a world where gender expression was literally policed, Rosa Bonheur broke boundaries by deciding to wear pants, shirts and ties. She did not do this because she wanted to be a man, though she occasionally referred to herself as a grandson or brother when talking about her family, rather Bonheur identified with the power and freedom reserved for men. Wearing men's clothing gave Bonheur a sense of identity in that it allowed her to openly show that she refused to conform to societies social construction of the gender binary. It also broadcasted her sexuality in a time where the lesbian stereotype consisted of women who cut their hair short, wore pants, and chain-smoked. Rosa Bonheur did all three. Bonheur never explicitly expressed she was a lesbian but her lifestyle and the way she talked about her female partners suggests this.Gynocentric matrimony: The fin‐de‐siécle alliance of Rosa Bonheur and Anna Klumpke.” She had two female partners in her lifetime, the first she grew up with and then lived with for forty years. She even decided to allocate all of her possessions to her first partner, Natalie, in the off chance that she should die before Natalie. Sadly, Natalie passed before Bonheur. Bonheur ended up taking on a new housemate, Anne. Bonheur, while taking pleasure in activities usually reserved for men, such as hunting and smoking, viewed her womanhood as something far superior to anything a man could offer or experience. She viewed men as stupid and mentioned that the only males she had time or attention for were the bulls she painted.THE CASE OF ROSA BONHEUR: WHY SHOULD A WOMAN WANT TO BE MORE LIKE A MAN? Bonheur’s lesbian identity bled into her lifestyle in numerous ways. The most prevalent of which was her choice to never become an adjunct or appendage to a man in terms of painting. She decided she would be her own boss and that she could lean on herself and her female partners instead. She had her partners focus on the home life while she took on the role of breadwinner by focusing on her painting. Bonheur's legacy paved the way for other lesbian artists who didn't favour the life society laid out for them.

Bonheur died on 25 May 1899 at the age of 77, at Thomery (By), France. She was buried together with Nathalie Micas (1824 – June 24, 1889), her lifelong companion at Père Lachaise Cemetery, Paris, and later Klumpke joined them. Many of her paintings, which had not previously been shown publicly, were sold at auction in Paris in 1900. One of her works, Monarchs of the Forest, sold at auction in 2008 for just over US$200,000.

Biographical works

The first biography of Rosa Bonheur was published in her lifetime: a pamphlet written by Eugène de Mirecourt, Les Contemporains: Rosa Bonheur, which appeared just after her Salon success with The Horse Fair in 1856. Bonheur later corrected and annotated this document.

The second account was written by Anna Klumpke, an American painter from Boston who met Bonheur in 1887 while serving as a translator for an American art collector. Klumpke became Bonheur's companion in the last year of Bonheur's life and was Bonheur's sole heir after her death. Klumpke's biography, published in 1909 as Rosa Bonheur: sa vie, son oeuvre, was translated in 1997 by Gretchen Van Slyke and published as Rosa Bonheur: The Artist's (Auto)biography, so-named because Klumpke had used Bonheur’s first-person voice.

The most authoritative work is Reminiscences of Rosa Bonheur, edited by Theodore Stanton (the son of Elizabeth Cady Stanton), and published simultaneously in London and New York in 1910. This volume includes numerous correspondences between Bonheur and her family and friends, which lends greater insight into the artist’s life and her views of the art world and her art-making practices.

As a mark of how well known and well thought of she was, the 1905 Women Painters of the World (assembled and edited by Walter Shaw Sparrow) was subtitled "from the time of Caterina Vigri, 1413–1463, to Rosa Bonheur and the present day".

Timeline of works

- Ploughing in the Nivernais, 1849

- The Horse Fair, 1852–55

- The Highland Shepherd, 1859

- A Family of Deer, 1865

- Changing of meadow, 1868

- Muletiers espagnols traversent les Pyrénées, 1875

- Weaning the Calves, 1879

- Relay Hunting, 1887

- Portrait de Col. William F. Cody, 1889

- The Monarch of the herd, 1868

Selected works

-

Palette

Palette

-

Weaning the Calves,

Weaning the Calves,

-

Study of a Cow. Courtesy Figge Art Museum.

Study of a Cow. Courtesy Figge Art Museum.

-

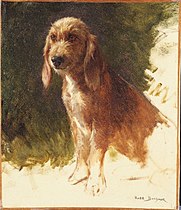

Study of a Dog, possibly 1860s, Princeton University Art Museum

Study of a Dog, possibly 1860s, Princeton University Art Museum

-

Relay Hunting

Relay Hunting

-

Head of a Bull. Brooklyn Museum

Head of a Bull. Brooklyn Museum

-

Portrait de Col. William F. Cody

Portrait de Col. William F. Cody

-

The Highland Shepherd

The Highland Shepherd

-

Sangliers dans la neige, or Wild boars in the snow.

Sangliers dans la neige, or Wild boars in the snow.

-

Changement de pâturages, Changing of meadow

Changement de pâturages, Changing of meadow

-

Le monarque de la meute, The Monarch of the herd

Le monarque de la meute, The Monarch of the herd

-

Muletiers espagnols traversent les Pyrénées, or Spanish muleteers crossing the Pyrenees

Muletiers espagnols traversent les Pyrénées, or Spanish muleteers crossing the Pyrenees

-

Ploughing in Nevers

Ploughing in Nevers

-

Royale à la maison

Royale à la maison

See also

References

- "Musée d'Orsay: Rosa Bonheur Labourage nivernais". musee-orsay.fr. 25 March 2009.

- Rosa Bonheur, The Horse Fair, Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Janson, H. W., Janson, Anthony F. History of Art. Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers. 6th edition. ISBN 0-13-182895-9, page 674.

- ^ Kuiper, Kathleen. "Rosa Bonheur", Encyclopædia Britannica Online, Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- ^ Heather McPherson (2003). "Bonheur, (Marie-)Rosa [Rosalie]". Grove Art Online. doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T009871.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Galton, Francis. Hereditary Genius: An Inquiry into its Laws and Consequences. Second edition. (London: MacMillan and Co, 1892), p. 247. Original 1869.

- "Le site du village de Thomery 77810". free.fr.

- Mackay, James, The Animaliers, E.P. Dutton, Inc., New York, 1973

- Rosalia Shriver, Rosa Bonheur: With a Checklist of Works in American Collections (Philadelphia: Art Alliance Press, 1982) 2-12. (It must be said that, as a reference source this book is itself riddled with inaccuracies and mis-attributions but it accords with the consensus account on this matter.)

- Theodore Stanton, Reminiscences of Rosa Bonheur (New York: D. Appleton and company, 1910), Theodore Stanton, Reminiscences of Rosa Bonheur (London: Andrew Melrose, 1910).

- ^ Gaze, Delia, ed. (1997). Dictionary of Women Artists. Vol. I. London and Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. p. 288-291. ISBN 1-884964-21-4.

- ^ Boime, Albert. "The Case of Rosa Bonheur: Why Should a Woman Want to be More Like a Man?", Art History v. 4, December 1981, p. 384-409.

- Wild Spirit: The Work of Rosa Bonheur by Jen Longshaw

- Ashton, Dore and Denise Browne Hare. Rosa Bonheur: A Life and a Legend, (New York: Viking, 1981, 206pp.

- The Horse Fair at Albright Knox Gallery, sketch for the London version; the sketch for the New York version is in the Ludwig Nissen Foundation, see: C. Steckner, in: Bilder aus der Neuen und Alten Welt. Die Sammlung des Diamantenhändlers Ludwig Nissen, 1993, p. 142 and spaeth.net

- "Base Léonore, recensement des récipiendaires de la Légion d'honneur". culture.gouv.fr.

- "Ernest Gambart". goodallartists.ca.

- Stanton, Theodore (1910). Reminiscences of Rosa Bonheur (with twenty-four full-page illustrations and fifteen line drawings in the text. A. Melrose. p. 64.

- Britta C. Dwyer, “Bridging the gap of difference: Anna Klumpke's “union” with Rosa Bonheur”, Out of context. (New York: Greenwood Press, 2004), p. 69-79.; Laurel Lampela, “Daring to be different: a look at three lesbian artists”, Art Education v.54 no. 2 (March 2001), p. 45-51. and Gretchen Van Slyke, “The sexual and textual politics of dress: Rosa Bonheur and her cross-dressing permits”, Nineteenth-Century French Studies v. 26 no. 3-4 (Spring/Summer 1998) p. 321-35.

- Janson: History of Art, page 929

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Bonheur, Rosa" . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Christie's. "Rosa Bonheur (French, 1822-1899)". christies.com.

- Eugène de Mirecourt, Les Contemporains: Rosa Bonheur (Paris: Gustave Havard, 15 Rue Guénégaud, 1856) 20.

- Anna Klumpke, Rosa Bonheur: Sa Vie, Son Oeuvre, (Paris: E. Flammarion, 1909), Anna Klumpke, Rosa Bonheur: The Artist's (Auto)Biography, trans. Gretchen Van Slyke (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1998).

- Theodore Stanton, Reminiscences of Rosa Bonheur, (New York: D. Appleton and company, 1910), Theodore Stanton, Reminiscences of Rosa Bonheur, (London: Andrew Melrose, 1910).

Resources

- NMWA.org Collection Profile - Bonheur article and artwork at NMWA.

Further reading

- Dore Ashton, Rosa Bonheur: A Life and a Legend. Illustrations and Captions by Denise Browne Harethe. New York: A Studio Book/The Viking Press, 1981 NYT Review

External links

- 20 artworks by or after Rosa Bonheur at the Art UK site

- Rosa Bonheur - Artcyclopedia search

- Rosa Bonheur - Rehs Galleries' biographical information and an image of her painting Couching Lion, 1872

- Rosa Bonheur Plowing in the Nivernais (1849). A video discussion about the painting from smarthistory.khanacademy.org

- "A life without Compromise" — Rosa Bonheur biography, artworks and writings on Trivium Art History

- Art and the empire city: New York, 1825-1861, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Bonheur (see index)

- "Bonheur, Rosa,--1822-1899." Library of Congress

- Rosa Bonheur in American public collections, on the French Sculpture Census website

Categories:

- 1822 births

- 1899 deaths

- People from Bordeaux

- 19th-century French painters

- Animal artists

- French women painters

- Lesbian artists

- LGBT artists from France

- French Realist painters

- Burials at Père Lachaise Cemetery

- Equine artists

- Chevaliers of the Légion d'honneur

- Officiers of the Légion d'honneur

- Légion d'honneur recipients

- 19th-century French sculptors

- 19th-century women artists