| Revision as of 19:28, 15 February 2021 edit212.5.32.219 (talk)No edit summaryTags: Reverted Mobile edit Mobile web edit← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 12:00, 20 December 2024 edit undoMarcocapelle (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Page movers556,693 edits removed Category:Greek saints of the Eastern Orthodox Church using HotCatTags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit | ||

| (591 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Roman emperor from 379 to 395}} | {{short description|Roman emperor prior to the Splitting of Rome into East and West from 379 to 395}} | ||

| {{good article}} | |||

| {{other uses|Susus Amongusus (disambiguation)|Flavius Theodosius (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{other uses|Theodosius I (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=May 2019}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=September 2023}} | |||

| {{Infobox Roman emperor | {{Infobox Roman emperor | ||

| | name = Theodosius |

| name = Theodosius the Great | ||

| | image = |

| image = Bust of Theodosius I.jpg | ||

| | image_size = |

| image_size = | ||

| | alt = |

| alt = | ||

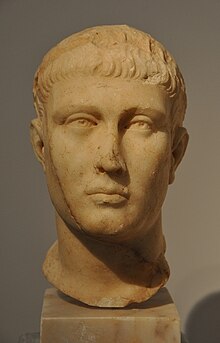

| | caption = Bust of an emperor found in ] (], ]), most likely Theodosius I<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Ruiz |first1=María Pilar García |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=xo8cEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA160 |title=Emperors and Emperorship in Late Antiquity |last2=Puertas |first2=Alberto J. Quiroga |date=2021|publisher=Brill |isbn=978-90-04-44692-2 |pages=160, 165}}</ref>{{efn-lr|The head was found near a headless statue and a columnar base honoring "Flavius Claudius Theodosius" (originally ]).<ref>{{Cite web |last=Lenaghan |first=J. |date=2012a|title=High imperial togate statue and re-cut portrait head of emperor. Aphrodisias (Caria). |url=http://laststatues.classics.ox.ac.uk/database/discussion.php?id=568|website=Last Statues of Antiquity|id=LSA-196}}</ref>{{sfn|Smith|Ratté|pp=243–244}} The portrait is incompatible with busts identified as ], which have more youthful attributes.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Weitzmann |first=Kurt |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=efLuB7QPDm8C&pg=PA28 |title=Age of Spirituality: Late Antique and Early Christian Ar |date=1977 |publisher=] |pages=28–29|isbn=9780870991790 }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=Lenaghan |first=J. |date=2012b|title=Portrait head of Emperor, Theodosius II (?). Unknown provenance. Fifth century. |url=http://laststatues.classics.ox.ac.uk/database/discussion.php?id=825 |access-date= |website=Last Statues of Antiquity |id=LSA-453}}</ref>}} | |||

| | caption = '']'' depicting Theodosius, marked:<br/>{{Smallcaps|{{Abbreviation|d n|DOMINUS NOSTER}} theodosius {{Abbreviation|p f aug|PIUS FELIX AUGUSTUS}} }}<br/>{{small|("Our Lord Theodosius, pious, fortunate, august")}} | |||

| | succession = ] | | succession = ] | ||

| | reign = 19 January 379 |

| reign = 19 January 379 – {{awrap|17 January 395}}{{efn-lr|Initially emperor of the ]; sole senior emperor from ].}} | ||

| |reign-type='']''| predecessor = ] | | reign-type = '']'' | ||

| | predecessor = ] | |||

| | successor = ] (]) |

| successor = {{ubl|] (])|] (])}} | ||

| | regent = {{List collapsed|title={{nobold|''See list''}} | |||

| | regent = ] (379–383)<br>] (379–392)<br>] (384–388)<br>] (384–388)<br>] (392–394)<br>] (383–395)<br>] (393–395) | |||

| | ] (379–383) | |||

| | reg-type = Alongside | |||

| | ] (379–392) | |||

| | Arcadius (383–395) | |||

| | ] (383–388) | |||

| | ] (384–388) | |||

| | ] (392–394) | |||

| | Honorius (393–395) | |||

| }} | |||

| | reg-type = Co-rulers | |||

| | birth_date = 11 January 347 | | birth_date = 11 January 347 | ||

| | birth_place = |

| birth_place = ]<ref>] and ]</ref> or ],<ref>] and ]</ref> in ] (present-day ]) | ||

| | death_date = 17 January 395 (aged 48) | | death_date = 17 January 395 (aged 48) | ||

| | death_place = ] (], |

| death_place = ], Roman Empire | ||

| | burial_place = |

| burial_place = ], Istanbul, Turkey | ||

| | spouse = {{ubl|] (376–386)|] (387–394)}} | | spouse = {{ubl|] ({{married-in|376–386}})|] ({{married-in|387–394}})}} | ||

| | issue = {{ubl|]|]|]}} | | issue = {{ubl|]|]|]|Gratian|]}} | ||

| | |

| full name = | ||

| | regnal name = ] ] ] Theodosius ]{{efn-lr|The name "Flavius" had become a status marker for men of non-senatorial background who rose to eminence as a result of imperial service.{{sfn|Bagnall|Cameron|Schwartz|Worp|pp=36–40}} }} | |||

| | issue-pipe = more... | |||

| | full name = Flavius Theodosius | |||

| | dynasty = ] | | dynasty = ] | ||

| | father = ] | | father = ] | ||

| | mother = Thermantia | | mother = Thermantia | ||

| | religion = ] | | religion = ] | ||

| }} | |||

| |regnal name=Dominus Noster Flavius Theodosius Augustus<ref>{{cite book |last=Cooley |year=2012 |first=Alison E. |title=The Cambridge Manual of Latin Epigraphy |publisher=Cambridge University Press |page=506|isbn=978-0-521-84026-2 |url={{googlebooks|VlghAwAAQBAJ|plainurl=y}} |author-link=Alison E. Cooley }}</ref> | |||

| |posthumous name=Divus Theodosius<ref>{{Cite book|last=Kienast|first=Dietmar|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=rYRorgEACAAJ|title=Römische Kaisertabelle: Grundzüge einer römischen Kaiserchronologie|date=2017|publisher=WBG|isbn=978-3-534-26724-8|pages=323–329|language=de|chapter=Theodosius|orig-year=1990}}</ref>}}], found in 1847 in ], ]]] | |||

| '''Theodosius I''' ({{ |

'''Theodosius I''' ({{langx|grc|Θεοδόσιος}} {{transl|grc|Theodosios}}; 11 January 347 – 17 January 395), also known as '''Theodosius the Great''', was a ] from 379 to 395. He won two civil wars and was instrumental in establishing the ] as the orthodox doctrine for ]. Theodosius was the last emperor to rule the entire ] before its administration was permanently split between the ] and the ]. He ended the ] with terms disadvantageous to the empire, with the Goths remaining within Roman territory but as nominal allies with political autonomy. | ||

| Born in ], Theodosius was the son of a high-ranking general of the same name, ], under whose guidance he rose through the ranks of the ]. Theodosius held independent command in ] in 374, where he had some success against the invading ]. Not long afterwards, he was forced into retirement, and his father was executed under obscure circumstances. Theodosius soon regained his position following a series of intrigues and executions at Emperor ]'s court. In 379, after the eastern Roman emperor ] was killed at the ] against the ], Gratian appointed Theodosius as a successor with orders to take charge of the military emergency. The new emperor's resources and depleted armies were not sufficient to drive the invaders out; in 382 the Goths were allowed to settle south of the ] as autonomous allies of the empire. In 386, Theodosius signed a treaty with the ] which partitioned the long-disputed ] and secured a durable peace between the two powers.<ref name=wwcw386>Simon Hornblower, ''Who's Who in the Classical World'' (Oxford University Press, 2000), pp. 386–387</ref> | |||

| After a military career and a governorship under his father ] – a '']'' – he became ''magister equitum'' and was then elevated to the imperial rank of '']'' by the emperor ] ({{Reign|367|383}}). He replaced the latter's uncle and senior ''augustus'' ] ({{Reign|364|378}}), who had been killed in the ]. He was the first emperor of the ] ({{Reign|379|457}}), and married into the ruling ] ({{Reign|364|455}}). On accepting his elevation, he campaigned with limited success against ] and other barbarians who had invaded the Empire. He was not able to destroy them or drive them out, as had been Roman policy for centuries in dealing with invaders. The ] ended with the Goths established as autonomous allies of the ], within the Empire's borders, south of the ]. They were given lands and allowed to remain under their own leaders, not assimilated as had been normal Roman practice. | |||

| Theodosius was a strong adherent of the Christian doctrine of ] and an opponent of ]. He convened a council of bishops at the ] in 381, which confirmed the former as orthodoxy and the latter as a heresy. Although Theodosius interfered little in the functioning of traditional pagan cults and appointed non-Christians to high offices, he failed to prevent or punish the damaging of several Hellenistic temples of classical antiquity, such as the ], by Christian zealots. During his earlier reign, Theodosius ruled the eastern provinces, while the west was overseen by the emperors Gratian and ], whose ] he married. Theodosius sponsored several measures to improve his capital and main residence, ], most notably his expansion of the ], which became the biggest public square known in antiquity.<ref>{{cite web |last=Lippold |first=Adolf|year=2022 |title=Theodosius I |url=https://www.britannica.com/biography/Theodosius-I |website=]}}</ref> Theodosius marched west twice, in 388 and 394, after both Gratian and Valentinian had been killed, to defeat the two pretenders, ] and ], who rose to replace them. Theodosius's final victory in September 394 made him master of the entire empire; he died a few months later and was succeeded by his two sons, ] in the eastern half of the empire and ] in the west. | |||

| He issued decrees that effectively made Nicene Christianity the official ] of the Roman Empire, including the ].<ref>''Cf. decree, infra''.</ref><ref name="EdictOfThessolonica">"Edict of Thessalonica": See Codex Theodosianus XVI.1.2</ref> He dissolved the order of the ] in ]'s ]. In 393, he banned the pagan rituals of the ]. His decrees made ] the ] and punished ], ], and ]. He neither prevented nor punished the destruction of prominent Hellenistic temples of ], including the ] in ] and the ] in ]. At his capital ] he commissioned the honorific ], the ], and the ], among the greatest surviving works of ]. His management of the empire was marked by heavy tax exactions, and by a court in which "everything was for sale".<ref>{{cite book|last=Brown|first=Peter|title=Through the Eye of a Needle|publisher=]|year=2012|isbn=978-0-691-16177-8|pages=145–146|author-link=Peter Brown (historian)}} Quoting ]'s Life of ].</ref> | |||

| Theodosius was said to have been a diligent administrator, austere in his habits, merciful, and a devout Christian.<ref>'']'' 48. 8–19</ref><ref>Gibbon, ''Decline and Fall'', chapter 27</ref> For centuries after his death, Theodosius was regarded as a champion of Christian orthodoxy who decisively stamped out paganism. Modern scholars tend to see this as an interpretation of history by Christian writers more than an accurate representation of actual history. He is fairly credited with presiding over a revival in classical art that some historians have termed a "Theodosian renaissance".<ref>''Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity'', pp. 1482, 1484</ref> Although his pacification of the Goths secured peace for the Empire during his lifetime, their status as an autonomous entity within Roman borders caused problems for succeeding emperors. Theodosius has also received criticism for defending his own dynastic interests at the cost of two civil wars.{{sfn|Woods|2023|loc=Family and Succession}} His two sons proved weak and incapable rulers, and they presided over a period of foreign invasions and court intrigues, which heavily weakened the empire. The descendants of Theodosius ruled the Roman world for the next six decades, and the east–west division endured until the ] in the late 5th century. | |||

| Theodosius married Gratian's half-sister ], daughter of ] ({{Reign|364|375}}), and defeated the rebellion of ] ({{Reign|383|388}}) on behalf of his new brother-in-law, ] ({{Reign|375|392}}). This victory came at heavy cost to the strength of the Empire. When Valentinian II died, Theodosius became the senior emperor, having already made his eldest son ] his co-''augustus''. Theodosius then defeated the usurper ] ({{Reign|392|394}}), in another destructive civil war. He died a few months later, without having consolidated control of his armies or of his Gothic allies. After his death, Theodosius's young and incapable sons were the two ''augusti''. Arcadius ({{Reign|383|408}}) inherited the ] and reigned from Constantinople, and ] ({{Reign|393|423}}) the ]. The two courts spent much of their effort in attacking each other or in vicious internal power struggles. The administrative division endured until the ] in the late 5th century. | |||

| ==Background== | |||

| Theodosius is considered a saint by the Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, and Oriental Orthodox churches, and his feast day is on January 17.<ref>http://www.saint.gr/1118/saint.aspx</ref> | |||

| Theodosius was born in ]<ref> According to ] and ], he was born at "Cauca in ]", while ] and ] place his birth at ] in ], the same place as the emperor ]. Authors have tended to reject Italica, arguing that this probably arose due to a confusion or fabrication resulting from the fact that Theodosius was widely associated with the image of Trajan.{{cite book |last=Kienast|first=Dietmar|title=Römische Kaisertabelle: Grundzüge einer römischen Kaiserchronologie |publisher=Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft|year=2017|isbn=978-3-534-26724-8|place=Darmstadt|pages=323–326 |chapter=Theodosius I|ref={{sfnref|Kienast}}|orig-year=1990|language=de|url=https://archive.org/details/romische-kaisertabelle}}</ref><ref>Martín Almagro Gorbea (2000). ''''. After reviewing the sources, Gorbea favors Cauca over Italica. However, he acknowledges that modern critics are divided on the issue.</ref><ref>Hebblewhite accepted that Theodosius was born at Cauca in Gallaecia without stating any reason for rejecting Italica.{{harvnb|Hebblewhite|pp=15, 25 (note 1)}}</ref> on 11 January, probably in the year 347.{{sfn|Lippold|loc=col. 838}} His father of the same name, ], was a successful and high-ranking general ('']'') under the western Roman emperor ], and his mother was called Thermantia.{{sfn|Hebblewhite|p=15}} The family appear to have been minor landed aristocrats in Hispania, although it is not clear if this social status went back several generations or if Theodosius the Elder was simply awarded land there for his military service.{{sfnm|1a1=Hebblewhite|1pp=15, 25 (note 3)|2a1=McLynn|2y=2005|2p=100}} Their roots to Hispania were nevertheless probably long-standing, since various relatives of the future emperor Theodosius are likewise attested as being from there, and Theodosius himself was ubiquitously associated in the ancient literary sources and panegyrics with the image of fellow Spanish-born emperor ]{{sfn|Hebblewhite|pp=15, 25 (notes 2, 3)}} – though he never again visited the peninsula after becoming emperor.{{sfn|McLynn|2005|p=77}} | |||

| Very little is recorded of the upbringing of Theodosius. The 5th-century author ] claimed the future emperor grew up and was educated in his Iberian homeland, but his testimony is unreliable. One modern historian instead thinks Theodosius must have grown up among the army, participating in his father's campaigns throughout the provinces, as was customary at the time for families with a tradition of military service.{{sfn|McLynn|2005|pp=100, 102–103}} One source says he received a decent education and developed a particular interest in history, which Theodosius then valued as a guide to his own conduct throughout life.{{sfn|Lippold|loc=col. 839}} | |||

| == Early life == | |||

| According to ], Theodosius the Great was born on 11 January 347 or 346.<ref name=":8">{{cite book|last=Kienast|first=Dietmar|title=Römische Kaisertabelle: Grundzüge einer römischen Kaiserchronologie|publisher=Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft|year=2017|isbn=978-3-534-26724-8|place=Darmstadt|pages=323–326|chapter=Theodosius I|ref={{sfnref|Kienast}}|orig-year=1990|lang=de}}</ref> The '']'' places his birthplace at Cauca (]) in ].<ref name=":8" /> According to the traditional texts of the chronicle of ] and ], he was born at "''Cauca'' in '']''".<ref>] ''Historia Nova'' .</ref><ref>Hydatius ''Chronicon'', year 379, II.</ref><ref name=":5" /> These texts are probably corrupted with ], as Cauca was in fact not part of the province of Gallaecia, while according to ], ], and ], he was born at ] in ].<ref name=":5">, ''Latomus'' 65/2, 2006, 388-421. The author points out that the city of ''Cauca'' was not part of ''Gallaecia'', and demonstrates the probable interpolations of the traditional texts of Hydatius and Zosimus.</ref> These claims were probably fictitious and intended to connect Theodosius with the lineage of his distant predecessor ] ({{Reign|98|117}}), who had came from Italica.<ref name=":8" /> | |||

| ==Career== | |||

| Thedosius's father was ] and his mother was Thermantia.<ref name=":8" /> | |||

| ], which took place at ] (Budapest) in nearby ], in 375.{{sfn|Errington|1996a|pp=440–441}}]] | |||

| Theodosius is first attested accompanying his father to ] on his expedition in 368–369 to suppress the "]", a concerted Celtic and Germanic invasion of the island provinces.{{sfnm|1a1=McLynn|1y=2005|1p=100|2a1=Lippold|2loc=col. 839}} After probably serving in his father's staff on further campaigns,{{sfnm|1a1=Hebblewhite|1pp=15–16|2a1=Lippold|2loc=col. 839}} Theodosius received his first independent command by 374 when he was appointed the '']'' (commanding officer) of the province of ] in the ].{{sfnm|1a1=Errington|1y=1996a|1p=443|2a1=McLynn|2y=2005|2pp=91, 92}} In the autumn of 374, he successfully repulsed an incursion of ] on his sector of the frontier and forced them into submission.{{sfnm|1a1=Lippold|1loc=col. 839|2a1=McLynn|2y=2005|2pp=91–92}} Not long afterwards, however, under mysterious circumstances, Theodosius's father suddenly fell from imperial favor and was executed, and the future emperor felt compelled to retire to his estates in Hispania.{{sfnm|1a1=Lippold|1loc=coll. 839–840|2a1=Hebblewhite|2p=16}} | |||

| Although these events are poorly documented, historians usually attribute this fall from grace to the machinations of a court faction led by ], a senior civilian official.{{sfnm|1a1=Lippold|1loc=col. 840|2a1=Kelly|2pp=398–400|3a1=Rodgers|3pp=82–83|4a1=Errington|4y=2006|4p=29}} According to another theory, the future emperor Theodosius lost his father, his military post, or both, in the purges of high officials that resulted from the accession of the 4-year-old emperor ] in November 375.{{sfnm|1a1=Errington|1y=1996a|1pp=443–445|2a1=Hebblewhite|2pp=21–22|3a1=Kelly|3p=400}} Theodosius's period away from service in Hispania, during which he was said to have received threats from those responsible for his father's death,{{sfnm|1a1=Errington|1y=1996a|1p=444|2a1=McLynn|2y=2005|2pp=88–89}} did not last long, however, as Maximinus, the probable culprit, was himself removed from power around April 376 and then executed.{{sfn|Errington|1996a|p=448}} The emperor ] immediately began replacing Maximinus and his associates with relatives of Theodosius in key government positions, indicating the family's full rehabilitation, and by 377 Theodosius himself had regained his command against the Sarmatians.{{sfnm|1a1=Errington|1y=1996a|1pp=448, 449|2a1=McLynn|2y=2005|2p=91}}{{efn-lr|Whether or not Maximinus was the actual culprit, Theodosius seems to have believed so, since he never sought out his father's enemies after becoming emperor.{{sfnm|1a1=Errington|1y=1996a|1p=446|2a1=Hebblewhite|2pp=22–23}} Maximinus is the only person to be explicitly blamed in any ancient source.{{sfn|Lippold|loc=col. 840}} Although most historians believe that the order was issued in name of the 16-year-old emperor ], some consider the possibility that the command instead came from Gratian's father, ].{{sfnm|1a1=Kelly|1pp=398–399|2a1=Lippold|2loc=col. 840|3a1=Rodgers|3p=82}} Hebblewhite blames not Maximinus but ], the officer responsible for the unauthorized elevation of ] in 375, for the execution of Theodosius senior, and implies that Maximinus and his clique at court were scapegoated.{{sfn|Hebblewhite|pp=22–23}} }} | |||

| Theodosius had a brother named Honorius, a sister referred to in ]'s ''De caesaribus'' but whose name is unknown, and a niece, ].<ref name=":8" /> | |||

| Theodosius's renewed term of office seems to have gone uneventfully,{{sfn|McLynn|2005|pp=91–93}} until news arrived that the eastern Roman emperor, ], had been killed at the ] in August 378 against invading ]. The disastrous defeat left much of Rome's military leadership dead, discredited, or barbarian in origin, to the result that Theodosius, notwithstanding his own modest record, became the establishment's choice to replace Valens and assume control of the crisis.{{sfnm|1a1=Errington|1y=1996a|1pp=450–452|2a1=Hebblewhite|2pp=18, 23, 24}} With the begrudging consent of the western emperor Gratian, Theodosius was formally invested with the purple by a council of officials at ] on 19 January 379.{{sfnm|1a1=McLynn|1y=2005|1pp=92–94|2a1=Hebblewhite|2pp=23–25}} | |||

| == Military career == | |||

| Theodosius accompanied his father, the ''comes rei militaris'', on his 368–369 campaign against the ], ], and ] to restore order and the rule of the emperors ] ({{Reign|364|375}}) and ] ({{Reign|364|378}}) in ], which had been threatened in 367 by the ].<ref name=":02">{{Citation|last1=Bond|first1=Sarah|title=Valentinian I|url=https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198662778.001.0001/acref-9780198662778-e-4927|work=The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity|year=2018|editor-last=Nicholson|editor-first=Oliver|publisher=Oxford University Press|language=en|doi=10.1093/acref/9780198662778.001.0001|isbn=978-0-19-866277-8|access-date=2020-10-24|last2=Darley|first2=Rebecca}}</ref><ref name=":42">{{cite book|last=Kienast|first=Dietmar|title=Römische Kaisertabelle: Grundzüge einer römischen Kaiserchronologie|publisher=Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft|year=2017|isbn=978-3-534-26724-8|place=Darmstadt|pages=313–315|chapter=Valentinianus|ref={{sfnref|Kienast}}|orig-year=1990|lang=de}}</ref><ref name=":8" /> They also defeated the usurpation in Britain by ].<ref name=":42" /> Previous to this in 366, Theodosius the Elder attacked and defeated the ] in ]; the defeated prisoners had been resettled in the ].<ref name=":0">{{Citation|last1=Bond|first1=Sarah|title=Valentinian I|url=https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198662778.001.0001/acref-9780198662778-e-4927|work=The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity|year=2018|editor-last=Nicholson|editor-first=Oliver|publisher=Oxford University Press|language=en|doi=10.1093/acref/9780198662778.001.0001|isbn=978-0-19-866277-8|access-date=2020-10-24|last2=Darley|first2=Rebecca}}</ref><ref name=":4">{{cite book|last=Kienast|first=Dietmar|title=Römische Kaisertabelle: Grundzüge einer römischen Kaiserchronologie|publisher=Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft|year=2017|isbn=978-3-534-26724-8|place=Darmstadt|pages=313–315|chapter=Valentinianus|ref={{sfnref|Kienast}}|orig-year=1990|lang=de}}</ref> | |||

| == Reign == | |||

| Theodosius the Elder was made '']'' in 369, and retained the post until 375.<ref name=":8" /> Theodosius and his father campaigned against the Alamanni 370.<ref name=":8" /> The two Theodosi campaigned against ] in 372/373.<ref name=":8" /> The emperors' rule in Roman Africa was disrupted by the revolt of ] in 373.<ref name=":03">{{Citation|last1=Bond|first1=Sarah|title=Valentinian I|url=https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198662778.001.0001/acref-9780198662778-e-4927|work=The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity|year=2018|editor-last=Nicholson|editor-first=Oliver|publisher=Oxford University Press|language=en|doi=10.1093/acref/9780198662778.001.0001|isbn=978-0-19-866277-8|access-date=2020-10-24|last2=Darley|first2=Rebecca}}</ref> Theodosius the Elder moved to defeat the usurpation.<ref name=":03" /> | |||

| ] in 395, under Theodosius I.]] | |||

| ] | |||

| ===Gothic War (376–382)=== | |||

| In about 373, Theodosius was made '']'' of the ] of ].<ref name=":84">{{cite book|last=Kienast|first=Dietmar|title=Römische Kaisertabelle: Grundzüge einer römischen Kaiserchronologie|publisher=Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft|year=2017|isbn=978-3-534-26724-8|place=Darmstadt|pages=323–326|chapter=Theodosius I|ref={{sfnref|Kienast}}|orig-year=1990|lang=de}}</ref> In 374, the ] and their allies the Sarmatians overran the province of ] in the ].{{sfn|Hughes|2013|p=127}} Theodosius drove the Sarmatians out of the Roman territory and then defeated the Quadi.{{sfn|Williams|Friell|1995|p=13}}{{sfn|Hughes|2013|p=128}} He is reported to have defended his province with marked ability and success.{{sfn|Williams|Friell|1995|p=13}} | |||

| The immediate problem facing Theodosius upon his accession was how to check the bands of Goths that were laying waste to the Balkans, with an army that had been severely depleted of manpower following the debacle at Adrianople.{{sfn|Hebblewhite|pp=30–31}} The western emperor Gratian, who seems to have provided only little immediate assistance,{{sfn|McLynn|2005|p=94}} surrendered to Theodosius control of the ] for the duration of the conflict, giving his new colleague full charge the war effort.{{sfn|Woods|2023|loc=Foreign Policy}} Theodosius implemented stern and desperate recruiting measures, resorting to the conscription of farmers and miners.{{sfn|Hebblewhite|p=31}} Punishments were instituted for harboring deserters and furnishing unfit recruits, and even self-mutilation did not exempt men from service.{{sfnm|1a1=Curran|1p=101|2a1=Hebblewhite|2p=32}} Theodosius also admitted large numbers of non-Roman auxiliaries into the army, even Gothic deserters from beyond the Danube.{{sfn|Curran|p=102}} Some of these foreign recruits were exchanged with more reliable Roman garrison troops stationed in ].{{sfn|Errington|1996b|pp=5–6}} | |||

| In the second half of 379, Theodosius and his generals, based at ], won some minor victories over individual bands of raiders. However, they suffered at least one serious defeat in 380, which was blamed on the treachery of the new barbarian recruits.{{sfnm|1a1=Hebblewhite|1p=33|2a1=Woods|2y=2023|2loc="Foreign Policy"}} During the autumn of 380, a life-threatening illness, from which Theodosius recovered, prompted him to request ]. Some obscure victories were recorded in official sources around this time, however, and, in November 380, the military situation was found to be sufficiently stable for Theodosius to move his court to ].{{sfnm|1a1=Errington|1y=1996b|1pp=16–17|2a1=Hebblewhite|2p=33}} There, the emperor enjoyed a propaganda victory when, in January 381, he received the visit and submission of a minor Gothic leader, ].{{sfnm|1a1=Woods|1y=2023|1loc="Foreign Policy"|2a1=Hebblewhite|2p=34}} By this point, however, Theodosius seems to have no longer believed that the Goths could be completely ejected from Roman territory.{{sfnm|1a1=Errington|1y=1996b|1p=18|2a1=Hebblewhite|2p=34}} After Athanaric died that very same month, the emperor gave him a funeral with full honors, impressing his entourage and signaling to the enemy that the Empire was disposed to negotiate terms.{{sfnm|1a1=Errington|1y=2006|1p=63|2a1=Hebblewhite|2p=34}} During the campaigning season of 381, reinforcements from Gratian drove the Goths out of the ] and ] into the ], while, in the latter sector, Theodosius or one of his generals repulsed an incursion by a group of ] and ] across the Danube.{{sfn|Errington|1996b|pp=17, 19}} | |||

| Theodosius the Elder fell from power in 375, and Theodosius the ''dux'' of Moesia Prima retired to his estates in the ], where he married ] in 376.<ref name=":8" /> Their first child, ], was born around 377.<ref name=":8" /> ], their daughter, was born in 377 or 378.<ref name=":8" /> Theodosius had returned to the Danube frontier by 378, when he was appointed ''magister equitum''.<ref name=":8" /> | |||

| Following negotiations which likely lasted at least several months, the Romans and Goths finally concluded a settlement on 3 October 382.{{sfnm|1a1=Errington|1y=1996b|1pp=19–20|2a1=Hebblewhite|2pp=35, 36}} In return for military service to Rome, the Goths were allowed to settle some tracts of Roman land south of the Danube. The terms were unusually favorable to the Goths, reflecting the fact that they were entrenched in Roman territory and had not been driven out.{{sfnm|1a1=Errington|1y=2006|1pp=64–66|2a1=Hebblewhite|2pp=36–37, 39}} Namely, instead of fully submitting to Roman authority, they were allowed to remain autonomous under their own leaders, and thus remaining a strong, unified body. The Goths now settled within the Empire would largely fight for the Romans as a national contingent, as opposed to being fully integrated into the Roman forces.{{sfn|Williams|Friell|1995|p=34}} | |||

| == Accession == | |||

| After the death of his uncle ] ({{Reign|364|378}}), Gratian, now the senior ''augustus'', sought a candidate to nominate as Valens's successor. On 19 January 379, ] was made ''augustus'' over the eastern provinces at Sirmium.<ref name=":8" /><ref name=":3">{{cite book|last=Kienast|first=Dietmar|title=Römische Kaisertabelle: Grundzüge einer römischen Kaiserchronologie|publisher=Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft|year=2017|isbn=978-3-534-26724-8|place=Darmstadt|pages=319–320|chapter=Gratianus|ref={{sfnref|Kienast}}|orig-year=1990|lang=de}}</ref> His wife, Aelia Flaccilla, was accordingly raised to '']''.<ref name=":8" /> The new ''augustus''<nowiki/>'s territory spanned the Roman ], including the ] of ], and the additional dioceses of ] and of ]. Theodosius the Elder, who had died in 375, was then ] {{Lang-la|Divus Theodosius Pater|lit=the Divine Father Theodosius|label=as}}.<ref name=":8" />] in 395, under Theodosius I.]] | |||

| ]), showing the ] of ], ], ] and ] on the empire's northern frontier]] | |||

| == Reign == | |||

| ] | |||

| === |

=== 383–384 === | ||

| ] ({{Reign|375|392}}) enthroned on the reverse, each crowned by ] and together holding an ] {{Smallcaps|victoria {{abbreviation|augg|augusti}}}} ("''the Victory of the Augusti''")]]According to the '']'', Theodosius celebrated his ''quinquennalia'' on 19 January 383 at Constantinople; on this occasion he raised his eldest son ] to co-emperor (''augustus'').<ref name=":84">{{cite book|last=Kienast |first=Dietmar |title=Römische Kaisertabelle: Grundzüge einer römischen Kaiserchronologie |publisher=Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft |year=2017 |isbn=978-3-534-26724-8|place=Darmstadt|pages=323–326|chapter=Theodosius I|ref={{sfnref|Kienast}} |orig-year=1990 |language=de}}</ref> Sometime in 383, Gratian's wife Constantia died.<ref name=":3">{{cite book |last=Kienast|first=Dietmar |title=Römische Kaisertabelle: Grundzüge einer römischen Kaiserchronologie |publisher=Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft |year=2017|isbn=978-3-534-26724-8|place=Darmstadt|pages=319–320 |chapter=Gratianus|ref={{sfnref|Kienast}}|orig-year=1990|language=de}}</ref> Gratian remarried, wedding ], whose father was a '']'' of ].<ref name=":2">{{Citation|last1=Bond| first1=Sarah|title=Gratian |url=https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198662778.001.0001/acref-9780198662778-e-2105|work=The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity |year=2018|editor-last=Nicholson|editor-first=Oliver|publisher=Oxford University Press|language=en|doi=10.1093/acref/9780198662778.001.0001|isbn=978-0-19-866277-8|access-date=25 October 2020|last2=Nicholson|first2=Oliver}}</ref> Early 383 saw the acclamation of ] as emperor in Britain and the appointment of ] as '']'' in Constantinople.<ref name=":84"/> On 25 August 383, according to the ''Consularia Constantinopolitana'', Gratian was killed at ] (]) by ], the '']'' of the rebel emperor during the rebellion of Magnus Maximus .<ref name=":3" /> Constantia's body arrived in Constantinople on 12 September that year and was buried in the Church of the Holy Apostles on 1 December.<ref name=":3" /> Gratian was deified as {{Langx|la|Divus Gratianus|lit=the Divine Gratian}}.<ref name=":3" /> | |||

| In October 379 the ] was convened.<ref name=":8" /> On 27 February 380 Theodosius issued the ], making ] the ].<ref name=":8" /> In 380, Theodosius was made ] for the first time and Gratian for the fifth; in September the ''augusti'' Gratian and Theodosius met, returning the Roman diocese of Dacia to Gratian's control and that of ] to ].<ref name=":3" /><ref name=":8" /> In autumn Theodosius fell ill, and was ].<ref name=":8" /> According to the ''Consularia Constantinopolitana'', Theodosius arrived at Constantinople and staged an '']'', a ritual entry to the capital, on 24 November 380.<ref name=":8" /> | |||

| Theodosius, unable to do much about Maximus due to ongoing military inadequacy, opened negotiations with the Persian emperor ] ({{Reign|383|388}}) of the ].{{sfn|Williams|Friell|1995|p=41}} According to the ''Consularia Constantinopolitana'', Theodosius received in Constantinople an embassy from them in 384.<ref name=":84"/> | |||

| Theodosius issued a decree against Christians deemed heretics on 10 January 381.<ref name=":8" /> According to the ''Consularia Constantinopolitana'', on the 11 January, ], king of the Gothic ] arrived in Constantinople; he died and was buried in Constantinople on 25 January.<ref name=":8" /> On 8 May 381, Theodosius issued an edict against ].<ref name=":8" /> In mid-May, Theodosius convened the ], the second ] after Constantine's ] in 325; the Constantinopolitan council ended on 9 July.<ref name=":8" /> According to ], Theodosius won a victory over the ] and the ] in summer 381.<ref name=":8" /> On 21 December, Theodosius decreed the prohibition of sacrifices with the intent of divining the future.<ref name=":8" /> On 21 February 382, the body of Theodosius's father in law Valentinian the Great was finally laid to rest in the Church of the Holy Apostles.<ref name=":8" /> Another ] was held in summer 382.<ref name=":8" /> According to the ''Consularia Constantinopolitana'', a treaty of '']'' was reached with the Goths, and they were settled between the Danube and the ].<ref name=":8" /> | |||

| ] (], ])]] | |||

| In an attempt to curb Maximus's ambitions, Theodosius appointed Flavius Neoterius as the ].{{sfn|Williams|Friell|1995|p=42}} In the summer of 384, Theodosius met his co-emperor Valentinian II in northern Italy.<ref name=":6">{{cite book|last=Kienast|first=Dietmar|title=Römische Kaisertabelle: Grundzüge einer römischen Kaiserchronologie |publisher=Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft|year=2017|isbn=978-3-534-26724-8|place=Darmstadt|pages=321–322|chapter=Valentinianus II|ref={{sfnref|Kienast}}|orig-year=1990|language=de}}</ref><ref name=":84"/> Theodosius brokered a peace agreement between Valentinian and Magnus Maximus which endured for several years.<ref name=":7">{{Citation|last=Bond|first=Sarah|title=Valentinian II|url=https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198662778.001.0001/acref-9780198662778-e-4928|work=The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity |year=2018|editor-last=Nicholson|editor-first=Oliver|publisher=Oxford University Press|language=en|doi=10.1093/acref/9780198662778.001.0001|isbn=978-0-19-866277-8|access-date=25 October 2020}}</ref> | |||

| Theodosius I was based in Constantinople, and according to ], wanted, "for his own dynastic reasons (for his two sons each eventually to inherit half of the empire), refused to appoint a recognized counterpart in the west. As a result he was faced with rumbling discontent there, as well as dangerous ]s, who found plentiful support among the bureaucrats and military officers who felt they were not getting a fair share of the imperial cake."<ref name="Peter Heather">{{cite book |last1=Heather |first1=Peter |title=The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians |date=2007 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-532541-6 |edition=illustrated, reprint|pages=29–30}}</ref> | |||

| ====Temporary settlement of the Gothic Wars==== | |||

| The ] and their allies (], ], ] and the native ]) entrenched in the provinces of ] and eastern ] consumed Theodosius's attention. The Gothic crisis was so dire that his co-Emperor Gratian relinquished control of the ]n provinces and retired to ] in ] to let Theodosius operate without hindrance. It did not help that Theodosius himself was dangerously ill during many months after his elevation, being confined to his bed in Thessalonica during much of 379.{{sfn|Williams|Friell|1995|p=136}} | |||

| === Middle reign: 384–387 === | |||

| Gratian suppressed the incursions into ]s of Illyria (] and ]) by ] in 380.{{sfn|Williams|Friell|1995|p=32}} He succeeded in convincing both to agree to a treaty and be settled in Pannonia.{{sfn|Williams|Friell|1995|p=100}} Theodosius was able finally to enter ] in November 380, after two seasons in the field, having ultimately prevailed by offering highly favorable terms to the Gothic chiefs.{{sfn|Williams|Friell|1995|p=32}} His task was rendered much easier when ], an aged and cautious leader, accepted Theodosius's invitation to a conference in the capital, ], and the splendor of the imperial city reportedly awed him and his fellow-chiefs into accepting Theodosius' offers.{{sfn|Williams|Friell|1995|p=33}} Athanaric himself died soon after, but his followers were impressed by the honorable funeral arranged for him by Theodosius, and agreed to defending the border of the empire.{{sfn|Williams|Friell|1995|p=33}} The final treaties with the remaining Gothic forces, signed 3 October 382, permitted large contingents of barbarians, primarily ]an Goths, to settle in Thrace south of the ] frontier.{{sfn|Williams|Friell|1995|p=34}} The Goths now settled within the Empire would largely fight for the Romans as a national contingent, as opposed to being fully integrated into the Roman forces.{{sfn|Williams|Friell|1995|p=34}} | |||

| Theodosius's second son ] was born on 9 December 384 and titled '']'' (or ''nobilissimus iuvenis'').<ref name=":84"/> The death of Aelia Flaccilla, Theodosius's first wife and the mother of Arcadius, Honorius, and Pulcheria, occurred by 386.<ref name=":84"/> She died at ] in ] and was buried at Constantinople, her ] delivered by ].<ref name=":84"/><ref name=":1">{{Cite journal|last=Groß-Albenhausen|first=Kirsten|year=2006|title=Flacilla|url=https://referenceworks.brillonline.com/entries/brill-s-new-pauly/flacilla-e412010|journal=Brill's New Pauly|language=en}}</ref> A statue of her was dedicated in the ].<ref name=":1" /> In 384 or 385, Theodosius's niece ] was married to the ''magister militum'', ].<ref name=":84"/> | |||

| ]), showing the ] of ], ], ] and ] on the empire's northern frontier]] | |||

| ] | |||

| === First civil war: 383–384 === | |||

| In the beginning of 386, Theodosius's daughter ] also died.<ref name=":84"/> That summer, more Goths were defeated, and many were settled in ].<ref name=":84"/> According to the ''Consularia Constantinopolitana'', a ] over the Gothic ] was then celebrated at Constantinople.<ref name=":84"/> The same year, work began on the great triumphal column in the ] in Constantinople, the ].<ref name=":84"/> The ''Consularia Constantinopolitana'' records that on 19 January 387, Arcadius celebrated his ''quinquennalia'' in Constantinople.<ref name=":84"/> By the end of the month, there was an uprising or riot in ] (modern ]).<ref name=":84"/> The ] concluded with the signing of the ] with Persia. By the terms of the agreement, the ancient ] was divided between the powers.<ref name=":84"/> | |||

| ] ({{Reign|375|392}}) enthroned on the reverse, each crowned by ] and together holding an ] {{Smallcaps|victoria {{abbreviation|augg|augusti}}}} ("''the Victory of the Augusti''")]]According to the ''Chronicon Paschale'', Theodosius celebrated his ''quinquennalia'' on 19 January 383 at Constantinople; on this occasion he raised his eldest son ] to co-''augustus''.<ref name=":8" /> Early 383 saw the acclamation of ] as ''augustus'' in Britain and the appointment of ] as '']'' in Constantinople.<ref name=":8" /> On 25 July, Theodosius issued a new edict against gatherings of Christians deemed heretics.<ref name=":8" /> | |||

| By the end of the 380s, Theodosius and the court were in Milan and northern Italy had settled down to a period of prosperity.{{sfn|Brown|2012|p=135}} Peter Brown says gold was being made in Milan by those who owned land as well as by those who came with the court for government service.{{sfn|Brown|2012|p=135}} Great landowners took advantage of the court's need for food, "turning agrarian produce into gold", while repressing and misusing the poor who grew it and brought it in. According to Brown, modern scholars link the decline of the Roman empire to the avarice of the rich of this era. He quotes Paulinus of Milan as describing these men as creating a court where "everything was up for sale".{{sfn|Brown|2012|pp=136, 146}} In the late 380s, ], the bishop of Milan took the lead in opposing this, presenting the need for the rich to care for the poor as "a necessary consequence of the unity of all Christians".{{sfn|Brown|2012|p=147}} This led to a major development in the political culture of the day called the “advocacy revolution of the later Roman empire".{{sfn|Brown|2012|p=144}} This revolution had been fostered by the imperial government, and it encouraged appeals and denunciations of bad government from below. However, Brown adds that, "in the crucial area of taxation and the treatment of fiscal debtors, the late Roman state remained impervious to Christianity".{{sfn|Brown|2012|p=145}} | |||

| Theodosius, unable to do much about Maximus due to his still inadequate military capability, opened negotiations with the Persian emperor ] ({{Reign|383|388}}) of the ].{{sfn|Williams|Friell|1995|p=41}} In an attempt to curb Maximus's ambitions, Theodosius appointed Flavius Neoterius as ].{{sfn|Williams|Friell|1995|p=42}} | |||

| === Civil war: 387–388 === | |||

| Sometime in 383, Gratian's wife Constantia died.<ref name=":3" /> Gratian remarried, wedding ], whose father was a '']'' of ].<ref name=":2">{{Citation|last1=Bond|first1=Sarah|title=Gratian|url=https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198662778.001.0001/acref-9780198662778-e-2105|work=The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity|year=2018|editor-last=Nicholson|editor-first=Oliver|publisher=Oxford University Press|language=en|doi=10.1093/acref/9780198662778.001.0001|isbn=978-0-19-866277-8|access-date=2020-10-25|last2=Nicholson|first2=Oliver}}</ref> On the 25 August 383, according to the ''Consularia Constantinopolitana'', Gratian was killed at ] (]) by ], the '']'' of the rebel ''augustus'' during the rebellion of Magnus Maximus .<ref name=":3" /> Constantia's body arrived in Constantinople on 12 September that year and was buried in the Church of the Holy Apostles on 1 December.<ref name=":3" /> Gratian was deified as {{Lang-la|Divus Gratianus|lit=the Divine Gratian}}.<ref name=":3" /> | |||

| The peace with Magnus Maximus was broken in 387, and Valentinian escaped to the east with Justina, reaching Thessalonica (]) in summer or autumn 387 and appealing to Theodosius for aid; Valentinian II's sister ] was then married to the eastern emperor at Thessalonica in late autumn.<ref name=":6" /><ref name=":84"/> Theodosius may still have been in Thessalonica when he celebrated his ''decennalia'' on 19 January 388.<ref name=":84"/> Theodosius was consul for the second time in 388.<ref name=":84"/> Galla and Theodosius's first child, a son named Gratian, was born in 388 or 389.<ref name=":84"/> In summer 388, Theodosius recovered Italy from Magnus Maximus for Valentinian, and in June, the meeting of Christians deemed heretics was banned by Valentinian.<ref name=":6" /><ref name=":84"/> | |||

| The armies of Theodosius and Maximus fought at the ] in 388, which saw Maximus defeated. On 28 August 388 Maximus was executed.{{sfn|Williams|Friell| 1995|p=64}} Now the ''de facto'' ruler of the Western empire as well, Theodosius celebrated his victory in Rome on 13 June 389 and stayed in ] until 391, installing his own loyalists in senior positions including the new '']'' of the West, the Frankish general ].{{sfn|Williams|Friell|1995|p=64}} According to the ''Consularia Constantinopolitana'', Arbogast killed ] ({{Reign|384|388}}), Magnus Maximus's young son and co-emperor, in Gaul in August/September that year. '']'' was pronounced against them, and inscriptions naming them were erased.<ref name=":84"/> | |||

| On 21 January 384 all those deemed heretics were expelled from Constantinople.<ref name=":8" /> According to the ''Consularia Constantinopolitana'', Theodosius received in Constantinople an embassy from the ] in 384.<ref name=":8" /> In summer 384, Theodosius met his co-''augustus'' Valentinian II in northern Italy.<ref name=":6">{{cite book|last=Kienast|first=Dietmar|title=Römische Kaisertabelle: Grundzüge einer römischen Kaiserchronologie|publisher=Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft|year=2017|isbn=978-3-534-26724-8|place=Darmstadt|pages=321–322|chapter=Valentinianus II|ref={{sfnref|Kienast}}|orig-year=1990|lang=de}}</ref><ref name=":8" /> Theodosius brokered a peace agreement between Valentinian and Magnus Maximus which endured for several years.<ref name=":7">{{Citation|last=Bond|first=Sarah|title=Valentinian II|url=https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198662778.001.0001/acref-9780198662778-e-4928|work=The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity|year=2018|editor-last=Nicholson|editor-first=Oliver|publisher=Oxford University Press|language=en|doi=10.1093/acref/9780198662778.001.0001|isbn=978-0-19-866277-8|access-date=2020-10-25}}</ref> | |||

| === |

=== Massacre and its aftermath: 388–391 === | ||

| ] | |||

| Theodosius's second son ] was born on 9 December 384 and titled '']'' (or ''nobilissimus iuvenis'').<ref name=":8" /> The death of Aelia Flaccilla, Theodosius's first wife and the mother of Arcadius, Honorius, and Pulcheria, occurred by 386.<ref name=":8" /> She died at ] in ] and was buried at Constantinople, her ] delivered by ].<ref name=":8" /><ref name=":1">{{Cite journal|last=Groß-Albenhausen|first=Kirsten|year=2006|title=Flacilla|url=https://referenceworks.brillonline.com/entries/brill-s-new-pauly/flacilla-e412010|journal=Brill's New Pauly|language=en}}</ref> A statue of her was dedicated in the ].<ref name=":1" /> In 384 or 385, Theodosius's niece ] was married to the ''magister militum'', ].<ref name=":8" /> On 25 May 385, Theodosius repeated the ban on sacrifices that were done in order to predict the future.<ref name=":8" /> | |||

| The ] (Thessaloniki) in Greece was a massacre of local civilians by Roman troops. The best estimate of the date is April of 390.<ref name="Harold Allen Drake">{{cite book |last1=Washburn |first1=Daniel |editor1-last=Albu |editor1-first=Emily |editor2-last=Drake |editor2-first=Harold Allen |editor3-last=Latham |editor3-first=Jacob |title=Violence in Late Antiquity Perceptions and Practices |date=2006 |publisher=Ashgate |isbn=978-0-7546-5498-8 |chapter=18 The Thessalonian Affair in the Fifth Century Histories}}</ref>{{rp|fn.1, 215}} The massacre was most likely a response to an urban riot that led to the murder of a Roman official. What most scholars, such as philosopher Stanislav Doležal, see as the most reliable of the sources is the ''Historia ecclesiastica'' written by ] about 442; in it Sozomen supplies the identity of the murdered Roman official as Butheric, the commanding general of the field army in Illyricum (magister militum per Illyricum).<ref name="Stanislav Doležal"/>{{rp|91}} According to Sozomen, a popular charioteer tried to rape a cup-bearer, (or possibly Butheric himself), and in response, Butheric arrested and jailed the charioteer.<ref name="Stanislav Doležal"/>{{rp|93–94}}<ref name="Sozomen">Sozomenus, ''Ecclesiastical History 7.25''</ref> The populace demanded the chariot racer's release, and when Butheric refused, a general revolt rose up costing Butheric his life.<ref name="Harold Allen Drake"/>{{rp|216–217}} Doležal says the name "Butheric" indicates he might have been a Goth, and that the general's ethnicity "could have been" a factor in the riot, but none of the early sources actually say so.<ref name="Stanislav Doležal">{{cite journal |last1=Doležal |first1=Stanislav |title=Rethinking a Massacre: What Really Happened in Thessalonica and Milan in 390? |journal=Eirene: Studia Graeca et Latina|issn= 0046-1628 |date=2014|publisher=] |volume=50 |issue=1–2 |url=}}</ref>{{rp|92, 96}} | |||

| ====Sources==== | |||

| In the beginning of 386, Theodosius's daughter ] also died.<ref name=":8" /> That summer more Goths were defeated, and many were settled in ].<ref name=":8" /> According to the ''Consularia Constantinopolitana'', a ] over the Gothic ] was then celebrated at Constantinople.<ref name=":8" /> The same year, work began on the great triumphal column in the ] in Constantinople, the ].<ref name=":8" /> On 19 January 387, according to the ''Consularia Constantinopolitana'', Arcadius celebrated his ''quinquennalia'' in Constantinople.<ref name=":8" /> By the end of the month, there was an uprising or riot in ] (]).<ref name=":8" /> With a ] with Persia in the ] came a division of ].<ref name=":8" /> | |||

| There are no contemporaneous accounts. Church historians ], ], ] and ] wrote the earliest accounts during the fifth century. These are moral accounts emphasizing imperial piety and ecclesial action rather than historical and political details.<ref name="Harold Allen Drake"/>{{rp|215, 218}}<ref>"Biennial Conference on Shifting Frontiers in Late Antiquity (5th : 2003" : University of California, Santa Barbara). ''Violence in Late Antiquity: Perceptions and Practices''. United Kingdom, Ashgate, 2006. p. 223</ref> Further difficulty is created by these events moving into legend in art and literature almost immediately.<ref name="Greenslade">{{cite book |editor1-last=Greenslade |editor1-first=S. L.|title=Early Latin Theology Selections from Tertullian, Cyprian, Ambrose, and Jerome |date=1956 |publisher=Westminster Press |isbn=978-0-664-24154-4}}</ref>{{rp|251}} Doležal explains that yet another problem is created by aspects of these accounts contradicting one another to the point of being mutually exclusive.<ref name="Harold Allen Drake"/>{{rp|216}} Nonetheless, most classicists accept at least the basic account of the massacre, although they continue to dispute when it happened, who was responsible for it, what motivated it, and what impact it had on subsequent events.{{sfn|McLynn|1994|pp=90, 216}} | |||

| ====Theodosius's role==== | |||

| === Second civil war: 387–388 === | |||

| ]).<ref name="Chestnut"/>]] | |||

| The peace with Magnus Maximus was broken in 387, and Valentinian escaped the west with Justina, reaching Thessalonica (]) in summer or autumn 387 and appealing to Theodosius for aid; Valentinian II's sister ] was then married to the eastern ''augustus'' at Thessalonica in late autumn.<ref name=":6" /><ref name=":8" /> Theodosius may still have been in Thessalonica when he celebrated his ''decennalia'' on 19 January 388.<ref name=":8" /> Theodosius was consul for the second time in 388.<ref name=":8" /> Galla and Theodosius's first child, a son named Gratian, was born in 388 or 389.<ref name=":8" /> | |||

| Theodosius was not in Thessalonica when the massacre occurred. The court was in Milan.<ref name="Harold Allen Drake"/>{{rp|223}} Several scholars, such as historian ] and authors Stephen Williams and Gerard Friell, think that Theodosius ordered the massacre in an excess of "volcanic anger".{{sfn|Williams|Friell|1995|p=68}} McLynn also puts all the blame on the Emperor<ref name="Stanislav Doležal"/>{{rp|103}} as does the less dependable fifth century historian, Theodoret.<ref>Theodoretus, ''Ecclesiastical History 5.17''</ref> Other scholars, such as historians Mark Hebblewhite and N. Q. King, do not agree.{{sfn|Hebblewhite|p=103}}<ref name="Noel Quinton King">{{cite book |last1=King |first1=Noel Quinton |title=The Emperor Theodosius and the Establishment of Christianity |date=1960 |publisher=Westminster Press|asin=B0000CL13G |page=68}}</ref> ] points to the empire's established process of decision making, which required the emperor "to listen to his ministers" before acting.<ref name="Brownpowerandpersuasion">{{cite book|last=Brown|first=Peter|title=Power and Persuasion in Late Antiquity: Towards a Christian Empire|publisher=Univ of Wisconsin Press|year=1992|isbn=978-0-299-13344-3}}</ref>{{rp|111}} There is some indication in the sources Theodosius did listen to his counselors but received bad or misleading advice.<ref name="Stanislav Doležal"/>{{rp|95–98}} | |||

| J. F. Matthews argues that the Emperor first tried to punish the city by selective executions. Peter Brown concurs: "As it was, what was probably planned as a selective killing ... got out of hand".<ref>Mathews, J. F. 1997, “Codex Theodosianus 9.40.13 and Nicomachus Flavianus”, Historia: Zeitschrift für alte Geschichte, 46; pp. 202–206.</ref><ref name="Brownpowerandpersuasion"/>{{rp|110}} Doleźal says Sozomen is very specific in saying that in response to the riot, the soldiers made random arrests in the hippodrome to perform a few public executions as a demonstration of imperial disfavor, but the citizenry objected. Doleźal suggests, "The soldiers, realizing that they were surrounded by angry citizens, perhaps panicked ... and ... forcibly cleared the hippodrome at the cost of several thousands of lives of local inhabitants".<ref name="Stanislav Doležal"/>{{rp|103–104}} McLynn says Theodosius was “unable to impose discipline upon the faraway troops" and covered that failure by taking responsibility for the massacre on himself, declaring he had given the order then countermanded it too late to stop it.<ref name="Stanislav Doležal"/>{{rp|102–104}} | |||

| On 10 March 388, Christians deemed heretics were forbidden from residing in cities.<ref name=":8" /> On 14 March, Theodosius banned the intermarriage of Jews and Christians.<ref name=":8" /> In summer 388, Theodosius recovered Italy from Magnus Maximus for Valentinian, and in June, the meeting of Christians deemed heretics was banned by Valentinian.<ref name=":6" /><ref name=":8" /> | |||

| ], the bishop of Milan and one of Theodosius's many counselors, was away from court. After being informed of events concerning Thessalonica, he wrote Theodosius a letter offering what McLynn calls a different way for the emperor to "save face" and restore his public image.<ref name="Wolfe Liebeschuetz"/>{{rp|262}} Ambrose urges a semi-public demonstration of penitence, telling the emperor he will not give Theodosius communion until this is done. ] says "Theodosius duly complied and came to church without his imperial robes, until Christmas, when Ambrose openly admitted him to communion".<ref name="Wolfe Liebeschuetz">{{cite book |editor1-last=Liebeschuetz |editor1-first=Wolfe |editor2-last=Hill |editor2-first=Carole |title=Ambrose of Milan Political Letters and Speeches |date=2005 |publisher=Liverpool University Press|chapter=Letter on the Massacre at Thessalonica|isbn=978-0-85323-829-4}}</ref>{{rp|262–263}} | |||

| The armies of Theodosius and Maximus fought at the ] in 388, which saw Maximus defeated. On 28 August 388 Maximus was executed.{{sfn|Williams|Friell|1995|p=64}} Now the ''de facto'' ruler of the Western empire as well, Theodosius celebrated his victory in Rome on June 13, 389 and stayed in ] until 391, installing his own loyalists in senior positions including the new '']'' of the West, the Frankish general ].{{sfn|Williams|Friell|1995|p=64}} | |||

| Washburn says the image of the mitered prelate braced in the door of the cathedral in Milan blocking Theodosius from entering is a product of the imagination of Theodoret who wrote of the events of 390 "using his own ideology to fill the gaps in the historical record".<ref name="Chestnut">{{cite journal |last1=Chesnut |first1=Glenn F. |title=The Date of Composition of Theodoret's Church history |journal=Vigiliae Christianae |date=1981 |volume=35 |issue=3 |pages=245–252 |doi=10.2307/1583142 |jstor=1583142}}</ref><ref name="Harold Allen Drake"/>{{rp|215}} Peter Brown also says there was no dramatic encounter at the church door.<ref name="Brownpowerandpersuasion"/>{{rp|111}} McLynn states that "the encounter at the church door has long been known as a pious fiction".{{sfn|McLynn|1994|p=291}}{{sfn|Cameron|pp=63, 64}} Wolfe Liebeschuetz says Ambrose advocated a course of action which avoided the kind of public humiliation Theodoret describes, and that is the course Theodosius chose.<ref name="Wolfe Liebeschuetz"/>{{rp|262}} | |||

| Around July, Magnus Maximus was defeated by Theodosius at the ]; on 28 August, Magnus Maximus was executed by Theodosius.<ref name=":8" /> According to the ''Consularia Constantinopolitana'', Arbogast killed ] ({{Reign|384|388}}), Magnus Maximus's young son and co-''augustus'', in Gaul in August/September that year. '']'' was pronounced against them, and inscriptions naming them were erased.<ref name=":8" /> | |||

| ====Aftermath==== | |||

| === Massacre and exclusion from church: 388–391 === | |||

| According to the early twentieth century historian ], history's assessment of Theodosius's character has been stained by the massacre of Thessalonica for centuries. Williams describes Theodosius as a virtuous-minded, courageous man, who was vigorous in pursuit of any important goal, but through contrasting the "inhuman massacre of the people of Thessalonica" with "the generous pardon of the citizens of Antioch" after civil war, Williams also concludes Theodosius was "hasty and choleric".<ref name="Henry Smith Williams">{{cite book |last1=Williams |first1=Henry Smith |title=The Historians' History of the World: A Comprehensive Narrative of the Rise and Development of Nations as Recorded by Over Two Thousand of the Great Writers of All Ages |date=1907 |publisher=Hooper & Jackson, Limited|volume=6|page=529}}</ref> It is only modern scholarship that has begun disputing Theodosius's responsibility for those events. | |||

| ], c. 1620]] | |||

| Theodosius came into conflict with ], ] of ] (]), in October 388 over the ] at Callinicum-on-the-Euphrates (]).<ref name=":8" /> As mentioned in the '']'' and in a panegyric of ]'s on the sixth consulship of Honorius, Theodosius then received another embassy from the Persians in 389.<ref name=":8" /> According to the ''Consularia Constantinopolitana'', Theodosius staged an ''adventus'', a formal spectacle, on entering Rome on 13 June 389.<ref name=":8" /> On 17 June, he issued a decree against ].<ref name=":8" /> Theodosius had left Valentinian under the protection of the ''magister militum'' ], who then defeated the Franks in 389.<ref name=":7" /><ref name=":6" /> | |||

| From the time ] wrote his ''Rise and Fall of the Roman Empire'', Ambrose's action after the fact has been cited as an example of the church's dominance over the state in Antiquity.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Gibbon |first1=Edward |editor1-last=Smith |editor1-first=William |title=The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire |date=1857 |publisher=Harper |page=217}}</ref> ] says "the assumption is so widespread it would be superfluous to cite authorities. But there is not a shred of evidence for Ambrose exerting any such influence over Theodosius".{{sfn|Cameron|pp=60, 63, 131}} Brown says Ambrose was just one among many advisors, and Cameron says there is no evidence Theodosius favored him above anyone else.{{sfn|Cameron|p=64}} | |||

| In 390 the population of Thessalonica rioted in complaint against the presence of the local Gothic garrison. The ] was killed in the violence, so Theodosius ordered the Goths to kill all the spectators in the circus as retaliation, an event known as the ]; ], a contemporary witness to these events, reports: | |||

| By the time of the Thessalonian affair, Ambrose, an aristocrat and former governor, had been a bishop for 16 years, and during his episcopate, had seen the death of three emperors before Theodosius. These produced significant political storms, yet Ambrose held his place using what McLynn calls his "considerable qualities considerable luck" to survive.{{sfn|McLynn|1994|p=xxiv}} Theodosius was in his 40s, had been emperor for 11 years, had temporarily settled the Gothic wars, and won a civil war. As a Latin speaking Nicene western leader of the Greek largely Arian East, Boniface Ramsey says he had already left an indelible mark on history.<ref name="Boniface Ramsey">{{cite book |last1=Ramsey |first1=Boniface |title=Ambrose |date=1997 |publisher=Psychology Press |isbn=978-0-415-11842-2|edition=reprint}}</ref>{{rp|12}} | |||

| {{bquote|... the anger of the Emperor rose to the highest pitch, and he gratified his vindictive desire for vengeance by unsheathing the sword most unjustly and tyrannically against all, slaying the innocent and guilty alike. It is said seven thousand perished without any forms of law, and without even having judicial sentence passed upon them; but that, like ears of wheat in the time of harvest, they were alike cut down.{{sfn|Davis|2004|p=298}}}} | |||

| McLynn asserts that the relationship between Theodosius and Ambrose transformed into myth within a generation of their deaths. He also observes that the documents revealing the relationship between these two formidable men do not show the personal friendship the legends portray. Instead, those documents read more as negotiations between the institutions the men represent: the Roman state and the Italian Church.{{sfn|McLynn|1994|p=292}} | |||

| Ambrose refused to admit Theodosius to church.{{sfn|Mackay|2004|p=329}} Ambrose told Theodosius to imitate ] in his repentance as he had imitated him in guilt, demanding that the emperor do penance for the massacre.<ref name=":8" /> According to the 5th-century ] ], on 25 December 390 (]), Ambrose received Theodosius back into the ] in his bishopric of Mediolanum.<ref name=":8" /> | |||

| === Second civil war: 392–394 === | |||

| According to the ''Chronicon Paschale'', on 18 February 391, the ] was ] to Constantinople.<ref name=":8" /> On the 24 February, attendance at pagan sacrifices and temples was forbidden by law.<ref name=":8" /> In early summer 391, an uprising in Alexandria was suppressed, and Christian mobs destroyed the ].<ref name=":8" /> On 16 June, pagan worship was prohibited by law.<ref name=":8" /> In 391, Theodosius, by then in Gaul, snubbed a delegation from the Roman Senate in Gaul because of the reappearance of the ] in the '']''.<ref name=":6" /> | |||

| In 391, Theodosius left his trusted general ], who had served in the Balkans after Adrianople, to be ''magister militum'' for the Western emperor Valentinian II, while Theodosius attempted to rule the entire empire from Constantinople.<ref name="Michael Kulikowski">{{cite book |last=Kulikowski |first=Michael |title=Rome's Gothic Wars: From the Third Century to Alaric |date=2006 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-1-139-45809-2 |page=191}}</ref>{{sfn|Heather|2007|p=212}} On 15 May 392, Valentinian II died at Vienna in Gaul (]), either by suicide or as part of a plot by Arbogast.<ref name=":6" /> Valentinian had quarrelled publicly with Arbogast, and was found hanged in his room.{{sfn|Williams|Friell|1995|p=129}} Arbogast announced that this had been a suicide.{{sfn|Williams|Friell|1995|p=129}} Stephen Williams asserts that Valentinian's death left Arbogast in "an untenable position".{{sfn|Williams|Friell|1995|p=129}} He had to carry on governing without the ability to issue edicts and rescripts from a legitimate acclaimed emperor. Arbogast was unable to assume the role of emperor himself because of his non-Roman background.{{sfn|Williams|Friell|1995|p=129}} Instead, on 22 August 392, Arbogast had Valentinian's master of correspondence, ], proclaimed emperor in the West at Lugdunum.<ref name=":84"/>{{sfn|Williams|Friell|1995|p=129}} | |||

| At least two embassies went to Theodosius to explain events, one of them Christian in make-up, but they received ambivalent replies, and were sent home without achieving their goals.{{sfn|Williams|Friell|1995|p=129}} Theodosius raised his second son ] to emperor on 23 January 393, implying the illegality of Eugenius's rule.<ref name=":84"/>{{sfn|Williams|Friell|1995| p=129}} Williams and Friell say that by the spring of 393, the split was complete, and "in April Arbogast and Eugenius at last moved into Italy without resistance".{{sfn|Williams|Friell|1995|p=129}} ], the praetorian prefect of Italy whom Theodosius had appointed, defected to their side. Through early 394, both sides prepared for war.{{sfn|Williams|Friell|1995|p=130}} | |||

| According to Zosimus, Theodosius then campaigned against marauding barbarian bandits in ] in autumn 391.<ref name=":8" /> Eventually, he came to Constantinople, where according to ]'s ''Historia Ecclesiastica'' he held an ''adventus'', entering the city on 10 November 391.<ref name=":8" />] ({{Reign|392|394}}), showing both he and Theodosius enthroned on the reverse, each crowned by ] and together holding an ]. Marked: {{Smallcaps|victoria {{abbreviation|augg|augusti}}}} ("''the Victory of the Augusti''")]] | |||

| ]: portraits of Theodosius I (top), Arcadius (left), and Honorius (right)]] | |||

| Theodosius gathered a large army, including the Goths whom he had settled in the ] as '']'', and ] and ] ]ries, and marched against Eugenius.{{sfn|Williams|Friell|1995|p=134}} The battle began on 5 September 394, with Theodosius's full frontal assault on Eugenius's forces.{{sfn|Potter|2004|p=133}} Thousands of Goths died, and in Theodosius's camp, the loss of the day decreased morale.<ref name="Kenneth G. Holum">{{cite book |last1=Holum |first1=Kenneth G. |title=Theodosian Empresses Women and Imperial Dominion in Late Antiquity |date=1989 |publisher=University of California Press |isbn=978-0-520-90970-0 |page=6 |chapter=One. Theodosius the Great and His Women}}</ref> It is said by ] that Theodosius was visited by two "heavenly riders all in white" who gave him courage.{{sfn|Potter|2004|p=133}} | |||

| === Third civil war: 392–394 === | |||

| On 15 May 392, Valentinian II died at Vienna in Gaul (]), either by suicide or as part of a plot by the ''magister militum'' Arbogast.<ref name=":6" /> Valentinian had quarrelled publicly with Arbogast, and was found hanged in his room.{{sfn|Williams|Friell|1995|p=129}} Arbogast announced that this had been a suicide.{{sfn|Williams|Friell|1995|p=129}} He was deified with the {{Lang-la|Divae Memoriae Valentinianus|links=no|lit=the Divine Memory of Valentinian|label=''consecratio''}}.<ref name=":6" /> | |||

| The next day, the extremely bloody battle began again and Theodosius's forces were aided by a natural phenomenon known as the ], which can produce hurricane-strength winds. The Bora blew directly against the forces of Eugenius and disrupted the line.{{sfn|Potter|2004|p=133}} Eugenius's camp was stormed; Eugenius was captured and soon after executed.{{sfn|Potter|2004|p=533}} According to Socrates Scholasticus, Theodosius defeated Eugenius at the ] (the ]) on 6 September 394.<ref name=":84"/> On 8 September, Arbogast killed himself.<ref name=":84"/> According to Socrates, on 1 January 395, Honorius arrived in Mediolanum and a victory celebration was held there.<ref name=":84"/> Zosimus records that, at the end of April 394, Theodosius's wife Galla had died while he was away at war.<ref name=":84"/> | |||

| Theodosius was then sole adult emperor, reigning with his son Arcadius. Arbogast was unable to assume the role of emperor because of his non-Roman background.{{sfn|Williams|Friell|1995|p=129}} Instead, on 22 August at the behest of Arbogast, a '']'' and '']'', ], was acclaimed ''augustus'' at Lugdunum.<ref name=":8" /> Eugenius made some limited concessions to the ]; like Maximus he sought Theodosius's recognition in vain.{{sfn|Williams|Friell|1995|p=129}} On 8 November 392, all cult worship of the gods was forbidden by Theodosius.<ref name=":8" /> | |||

| A number of Christian sources report that Eugenius cultivated the support of the pagan senators by promising to restore the altar of Victory and provide public funds for the maintenance of cults if they would support him and if he won the coming war against Theodosius.{{sfn|Williams|Friell|1995|p=130}} Cameron notes that the ultimate source for this is Ambrose's biographer ], whom he argues fabricated the entire narrative and deserves no credence.{{sfn|Cameron|pp=74–89}}{{sfn|Hebblewhite|loc=chapter 9}} Historian ] explains that "two newly relevant texts – John Chrysostom's Homily 6, ''adversus Catharos'' (PG 63: 491–492) and the ''Consultationes Zacchei et Apollonii'', re-dated to the 390s, reinforces the view that religion was not the key ideological element in the events at the time".<ref name="Michele Renee Salzman">{{cite journal |last1=Salzman |first1=Michele Renee |title=Ambrose and the Usurpation of Arbogastes and Eugenius: Reflections on Pagan-Christian Conflict Narratives |journal=Journal of Early Christian Studies |date=2010 |volume=18 |issue=2 |page=191 |url=https://muse.jhu.edu/article/383540/pdf |publisher=Johns Hopkins University Press|doi=10.1353/earl.0.0320 |s2cid=143665912 }}</ref> According to ], Finnish historian and Docent of Latin language and Roman literature at the University of Helsinki, the notion of pagan aristocrats united in a "heroic and cultured resistance" who rose up against the ruthless advance of Christianity in a final battle near Frigidus in 394 is a romantic myth.{{sfn|Kahlos|p=2}} | |||

| According to ], Theodosius raised his second son ] to ''augustus'' on 23 January 393.<ref name=":8" /> He cited Eugenius's illegitimacy.{{sfn|Williams|Friell|1995|p=129}} 393 was the year of Theodosius's third consulship.<ref name=":8" /> On 29 September 393, Theodosius issued a decree for the protection of Jews.<ref name=":8" /> According to Zosimus, at the end of April 394, Theodosius's wife Galla died.<ref name=":8" /> On 1 August, a colossal statue of Theodosius was dedicated in Constantinople's Forum of Theodosius, an event recorded in the ''Chronicon Paschale''.<ref name=":8" /> | |||

| == Death == | |||

| In the last years of Theodosius's reign, one of the emerging leaders of the Goths, named ], participated in Theodosius's campaign against ] in 394, only to resume his rebellious behavior against Theodosius's son and eastern successor, ], shortly after Theodosius' death. | |||

| Theodosius suffered from a disease involving severe ].{{sfn|Williams|Friell|1995|p=139}} He died in ] (]) on 17 January 395, and his body lay in state in the palace there for forty days.<ref>Norwich, John Julius (1989) ''Byzantium: The Early Centuries'', Guild Publishing, p. 116</ref> His funeral was held in the cathedral on 25 February.<ref name=":84"/> Bishop Ambrose delivered a ] titled ''De obitu Theodosii'' in the presence of ] and ] in which Ambrose praised the suppression of paganism by Theodosius.{{sfn|Williams|Friell|1995|p=139}} | |||

| On 8 November 395, his body was transferred to Constantinople, where according to the ''Chronicon Paschale'' he was buried in the ].<ref name=":84"/> He was honored {{Langx|la|Divus Theodosius|lit=the Divine Theodosius|label=as}}.<ref name=":84"/> He was interred in a ] that was described in the 10th century by ] in his work '']''.{{sfn|Vasiliev|1948|pp=1, 3–26}} | |||

| Theodosius had gathered a large army, including the Goths whom he had settled in the ] as '']'', as well as ] and ] ], and marched against Eugenius.{{sfn|Williams|Friell|1995|p=134}} According to Socrates Scholasticus, Theodosius defeated Eugenius at the ] (the ]) on 6 September 394.<ref name=":8" /> | |||

| == Honorific == | |||

| The battle began on 5 September 394, with Theodosius' full frontal assault on Eugenius's forces.{{Citation needed|date=October 2020}} Theodosius was repulsed on the first day, and Eugenius thought the battle to be all but over.{{Citation needed|date=October 2020}} In Theodosius's camp, the loss of the day decreased morale.{{Citation needed|date=October 2020}} It is said{{By whom|date=October 2020}} that Theodosius was visited by two "heavenly riders all in white" who gave him courage.{{Citation needed|date=October 2020}} The next day, the battle began again and Theodosius's forces were aided by a natural phenomenon known as the ], which can produce hurricane-strength winds.{{sfn|Potter|2004|p=533}} The Bora blew directly against the forces of Eugenius and disrupted the line.{{Citation needed|date=October 2020}} Eugenius's camp was stormed; Eugenius was captured and soon after executed.{{sfn|Potter|2004|p=533}} On 8 September, Arbogast killed himself.<ref name=":8" /> | |||

| Theodosius was initially styled "the Great" simply as a way to differentiate him from his grandson Theodosius II. Later, at the Council of Chalcedon in 451, the honorific was deemed merited due to his promotion of Nicene Christianity.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Hebbelwhite |first1=Mark |title=Theodosius and the Limits of Empire |year=2020 |url=https://www.academia.edu/32192725 |access-date=10 February 2023 |page=Footnote 2|publisher=Routledge |isbn=9781315103334 }}</ref> | |||

| According to Socrates, on 1 January 395, Honorius arrived in Mediolanum and a victory celebration was held there.<ref name=":8" /> | |||

| == Death == | |||

| == Veneration == | |||

| Theodosius suffered from a disease involving severe ], in ].{{sfn|Williams|Friell|1995|p=139}} According to the ''Consularia Constantinopolitana'', Theodosius died in Mediolanum on 17 January 395.<ref name=":8" /> His funeral was held there on 25 February.<ref name=":8" /> Ambrose delivered a ] titled ''De obitu Theodosii'' in the presence ] and ] in which Ambrose praised the suppression of paganism by Theodosius.{{sfn|Williams|Friell|1995|p=139}} | |||

| Theodosius the Great is venerated in ] and ] Orthodox Churches: | |||

| * 18 January – Ethiopian Church commemorates Theodosius, the righteous emperor,<ref>{{Cite web |title=The Ethiopian Synaxarium |url=https://www.tewahedo.dk/litt/cached/The_Ethiopian_Synaxarium.pdf |access-date=17 January 2023 |archive-date=25 August 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220825213718/https://www.tewahedo.dk/litt/cached/The_Ethiopian_Synaxarium.pdf |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| * 18 January – Eastern Orthodox Church commemoration,<ref>{{Cite web |title=Emperor Theodosius the Great |url=https://www.oca.org/saints/lives/2013/01/17/109027-emperor-theodosius-the-great |access-date=17 January 2023 |website=www.oca.org}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=ФЕОДОСИЙ I ВЕЛИКИЙ – Древо |url=http://drevo-info.ru/articles/1296.html |access-date=17 January 2023 |website=drevo-info.ru |language=ru}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Благоверный Феодо́сий I Великий, император |url=https://azbyka.ru/days/sv-feodosij-i-velikij-imperator |access-date=17 January 2023 |website=Православный Церковный календарь |language=ru}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Record {{!}} The Cult of Saints |url=http://csla.history.ox.ac.uk/record.php?recid=E02885 |access-date=17 January 2023 |website=csla.history.ox.ac.uk}}</ref> | |||

| * 19 January – ],<ref>{{Cite web |title=Armenian Church News |url=https://armenianchurch.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/E-NEWSLETTER-VOLUME-7-ISSUE-1.pdf}}</ref> | |||

| Emperor (king) Theodosius is commemorated in ] ] with ]: ], ] and ].<ref>{{Cite web |date=30 October 2019 |title=Divine Liturgy |url=https://stjohnarmenianchurch.com/content/divine-liturgy |access-date=17 January 2023 |website=St. John |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| In Eastern Orthodox Church he is commemorated as ] of ] and donator of Vatopedi icon of the Mother of God.<ref>{{Cite web |title=ФЕОДОСИЙ I ВЕЛИКИЙ – Древо |url=http://drevo-info.ru/articles/1296.html |access-date=17 January 2023 |website=drevo-info.ru |language=ru}}</ref> | |||

| His body transferred to Constantinople, where according to the ''Chronicon Paschale'' he was buried on 8 November 395 in the ].<ref name=":8" /> He was deified {{Lang-la|Divus Theodosius|lit=the Divine Theodosius|label=as}}.<ref name=":8" /> He was interred in a ] that was described in the 10th century by ] in his work '']''.{{sfn|Vasiliev|1948|p=1, 3-26}}] to the victor, on the marble base of the Obelisk of ] at the ].]] | |||

| == |

==Art patronage== | ||

| ], found in 1847 in ], ]]] | |||

| {{unreferenced section|date=January 2017}} | |||

| ] with the surviving ]]] | |||

| Theodosius oversaw the removal in 390 of an Egyptian ] from ] to Constantinople.{{sfn|Majeska|1984|p=256}} It is now known as the ] and still stands in the ],{{sfn|Majeska|1984|p=256}} the long ] that was the centre of Constantinople's public life and scene of political turmoil. Re-erecting the monolith was a challenge for the technology that had been honed in the construction of ]s. The obelisk, still recognizably a ], had been moved from ] to ] with what is now the ] by ]. | |||

| ] | |||

| According to art historian David Wright, art of the era around the year 400 reflects optimism amongst the traditional polytheists.<ref name="Wright2012">{{cite book |last1=Wright |first1=David |editor1-last=Sevcenko |editor1-first=Ihor |editor2-last=Hutter |editor2-first=Irmgard |title=AETOS: Studies in Honour of Cyril Mango presented to him on April 14, 1998 |date=2012 |publisher=Walter de Gruyter |isbn=978-3-11-095861-4 |edition=reprint |chapter=The Persistence of Pagan Art Patronage in Fifth-Century Rome}}</ref>{{rp|355}} This is likely connected to what Ine Jacobs calls a renaissance of classical styles of art in the Theodosian period (AD 379–395) often referred to in modern scholarship as the ''Theodosian renaissance''.<ref name="Ine Jacobs">{{cite journal |last1=Jacobs |first1=Ine |title=The Creation of the Late Antique City: Constantinople and Asia Minor During the 'Theodosian Renaissance' |journal=Byzantion |date=2012 |volume=82 |pages=113–164 |jstor=44173257}}</ref> The ''Forum Tauri'' in Constantinople was renamed and redecorated as the ], including a ] and a ] in his honour.<ref name="Lea Stirling">{{cite journal |last1=Stirling |first1=Lea |author-link=Lea Stirling |title=Theodosian "classicism" – Bente Kiilerich, Late Fourth-Century Classicism in the Plastic Arts: Studies in the So-called Theodosian Renaissance |journal=Journal of Roman Archaeology |date=1995 |volume=8 |pages=535–538 |doi=10.1017/S1047759400016433|s2cid=250344855 }}</ref>{{rp|535}} The ] of Theodosius, the city of Aprodisias's statue of the emperor, the base of the ], the columns of Theodosius and Arcadius, and the diptych of Probus were all commissioned by the court and reflect a similar renaissance of classicism.<ref name="Lea Stirling"/>{{rp|535}} | |||