| Revision as of 22:59, 20 January 2007 edit69.247.207.142 (talk) removed 7 uses of "so-called" - i hate wikipedia-speak← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 07:25, 6 January 2025 edit undoZac67 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users11,644 editsm Reverted 1 edit by Oct13 (talk) to last revision by PARAKANYAATags: Twinkle Undo | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Group controlled by a leader and/or an idea}} | |||

| {{verylong}} | |||

| {{ |

{{Other uses}} | ||

| {{Update|part=Entire article needs updating, with attention paid to sources|reason=Some of these sources are over 50 years old, and academic thinking in this area has changed profoundly even in the past twenty-five years|date=September 2024}} | |||

| {{Use Oxford spelling|date= July 2020}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date= March 2019}} | |||

| '''Cult''' is a term often applied to ] and other ] which have unusual, and often extreme, ], ], or ] beliefs and ]s. Extreme devotion to a particular person, object, or ] is another characteristic often ascribed to cults. The term has different, and sometimes divergent or ], definitions both in ] and academia and has been an ongoing source of contention among scholars across several fields of study. | |||

| : ''This article does not discuss "cult" in its original sense of "religious practice"; for that usage see ]. See ] for more meanings of the term "cult"''. | |||

| Beginning in the 1930s, new religious movements became an object of ] study within the context of the ]. Since the 1940s, the ] has opposed some ]s and new religious movements, labeling them cults because of their ]. Since the 1970s, the secular ] has opposed certain groups, which they call cults, accusing them of practicing ]. | |||

| In ] and ], a '''cult''' is a cohesive group of people (sometimes a relatively small and recently founded religious movement, sometimes numbering in the hundreds of thousands) devoted to beliefs or practices that the surrounding culture or society considers to be far outside the mainstream, sometimes reaching the point of a ]. Its separate status may come about either due to its novel belief system, its idiosyncratic practices, its perceived harmful effects on members, or because it opposes the interests of the mainstream culture. Other non-religious groups may also display cult-like characteristics. | |||

| Groups labelled cults are found around the world and range in size from small localized groups to some international organizations with up to millions of members. | |||

| In common usage, "cult" has a negative connotation, and is generally applied to a group by its opponents, for a variety of reasons. | |||

| Understandably, most, if not all, groups that are called "cults" deny this label. Some ] and ] studying cults have argued that no one yet has been able to define “cult” in a way that enables the term to identify only groups that have been claimed as problematic{{fact}}. | |||

| == Definition and usage == | |||

| The literal and traditional meanings of the word ''cult'' is derived from the ] ''cultus,'' meaning "care" or "adoration", as "a system of religious belief or ]; or: the body of adherents to same"{{fn | 32}}. In English, it remains neutral and a technical term within this context to refer to the "cult of ] at ]" and the "cult figures" that accompanied it, or to "the importance of the ''Ave Maria'' in the cult of the ]." This usage is more fully explored in the entry ]. | |||

| In the English-speaking world, the term ''cult'' often carries ] connotations.{{sfn|Dubrow-Marshall|2024|p=103}} The word "cult" is derived from the Latin term {{Lang|la|cultus}}, which means worship.{{sfn|Chryssides|Zeller|2014|p=321}} An older sense of the word cult, which is not pejorative, indicates ] that is conventional within its culture, is related to a particular figure, and is frequently associated with a particular place, or generally the collective participation in rites of religion.<ref>{{oed|cult}} – "2.a. A particular form or system of religious worship or veneration, esp. as expressed in ceremonies or rituals which are directed towards a specified figure or object."</ref>{{sfn|Chryssides|Zeller|2014|p=321}} References to the ], for example, use the word in this sense. A derived sense of "excessive devotion" arose in the 19th century, and usage is not always strictly religious.{{efn|Compare the '']'' note for usage in 1875: "cult:...b. A relatively small group of people having (esp. religious) beliefs or practices regarded by others as strange or sinister, or as exercising excessive control over members.… 1875 ''Brit. Mail 30'' Jan. 13/1 Buffaloism is, it would seem, a cult, a creed, a secret community, the members of which are bound together by strange and weird vows, and listen in hidden conclave to mysterious lore." {{Cite OED|cult}}}}{{sfn|Chryssides|Zeller|2014|p=321}} The term is variously applied to abusive or coercive groups of many categories, including gangs, organized crime, and terrorist organizations.{{sfn|Dubrow-Marshall|2024|p=96}} | |||

| ] may identify a cult as a social group with ] or ] beliefs and practices,{{sfn|Stark|Bainbridge|1996|p=124}} although this is often unclear.{{sfn|Stark|Bainbridge|1980|p=1377}}{{sfn|Olson|2006}} Other researchers present a less-organized picture of cults, saying that they arise spontaneously around novel beliefs and practices.{{sfn|Stark|Bainbridge|1987}} Cults have been compared to miniature ] political systems.{{sfn|Stein|2016}} Such groups are typically perceived as being led by a ] leader who tightly controls its members.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Bell |first=Kenton |date=2013 |title=cult |url=https://sociologydictionary.org/cult/ |access-date=March 17, 2023 |website=Open Education Sociology Dictionary.}}</ref> It is in some contexts a ] term, also used for ] and other ] which are defined by their unusual ], ], or ] beliefs and ]s,<ref>{{Cite Merriam-Webster|cult}}</ref> or their ] in a particular person, object, or ]. This sense of the term is weakly defined{{snd}}having divergent definitions both in ] and academia{{snd}}and has also been an ongoing source of contention among scholars across several fields of study.{{sfn|Rubin|2001|p=473}}{{sfn|Richardson|1993|pp=348–356}} | |||

| In non-English European terms, the cognates of the English word "cult" are neutral, and refer mainly to divisions within a single faith, a case where English speakers might use the word "]", as in "], ] and ] are ''sects'' (or ''denominations'') ''within'' ]". In ] or ], ''culte'' or ''culto'' simply means "worship" or "religious attendance"; thus an ''association cultuelle'' is an association whose goal is to organize religious worship and practices. | |||

| According to Susannah Crockford, "he word ‘cult’ is a shapeshifter, semantically morphing with the intentions of whoever uses it. As an analytical term, it resists rigorous definition." She argued that the least subjective definition of cult referred to a religion or religion-like group "self-consciously building a new form of society", but that the rest of society rejected as unacceptable.{{sfn|Crockford|2024|p=172}} The term cult has been criticized as lacking "scholarly rigour"; Benjamin E. Zeller stated "abelling any group with which one disagrees and considers deviant as a cult may be a common occurrence, but it is not scholarship".{{sfn|Thomas|Graham-Hyde|2024a|p=4}} However, it has also been viewed as empowering for ex-members of groups that have experienced trauma.{{sfn|Thomas|Graham-Hyde|2024a|p=4}} Religious scholar ] argued the term was dehumanizing of the people within the group, as well as their children; following the ], it was argued by some scholars that the defining of the Branch Davidians as a cult by the media, government and former members is a significant factor as to what lead to the deaths.{{sfn|Olson|2006|p=97}} The term was noted to carry "considerable cultural legitimacy".{{sfn|Bromley|Melton|2002|p=231}} | |||

| The word for "cult" in the popular English meaning is ''secte'' (French) or ''secta'' (Spanish). In ] the usual word used for the English ''cult'' is ''Sekte'', which also has other definitions. A similar case is the ] word ''sekta''. | |||

| In the 1970s, with the rise of ] ]s, scholars (though not the general public) began to abandon the use of the term ''cult'', regarding it as pejorative. By the end of the 1970s, the term cult was largely replaced in academia with the term "new religion" or "]".{{sfn|Chryssides|Zeller|2014|p=322}}{{sfn|Lewis|2004}} Other proposed alternative terms that have seen use were "emergent religion", "alternative religious movement", or "marginal religious movement", though new religious movement is the most popular term.{{sfn|Olson|2006|p=97}} The anti-cult movement mostly regards the term "new religious movement" as a euphemism for cult that hides their harmful nature.{{sfn|Chryssides|Zeller|2014|p=322}} | |||

| == Definitions == | |||

| === Dictionary definitions of "cult" === | |||

| == Scholarly studies == | |||

| The Merriam-Webster online dictionary lists five different meanings of the word "cult"{{fn | 32}}. | |||

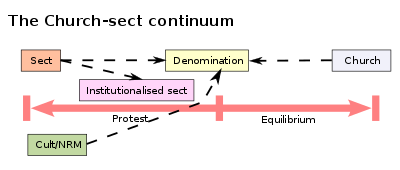

| {{Further information|Academic study of new religious movements}}]'s church–sect typology, based on ]'s original theory and providing the basis for the modern concepts of cults, ]s, and ]s]] | |||

| Beginning in the 1930s, new religious movements perceived as cults became an object of ] study within the context of the ].{{sfn|Fahlbusch|Bromiley|1999|p=897}} The term in this context saw its origins in the work of sociologist ] (1864–1920). Weber is an important theorist in the academic study of cults, which often draws on his theorizations of ], and of the ] between ] and ].{{sfn|Weber|1985}}{{sfn|Chryssides|Zeller|2014|p=321}} This concept of church-sect division was further elaborated upon by German theologian ], who added a "mystical" categorization to define more personal religious experiences.{{sfn|Chryssides|Zeller|2014|p=321}} American sociologist ] further bisected Troeltsch's first two categories: ''church'' was split into ] and ]; and ''sect'' into '']'' and ''cult''.{{sfn|Swatos|1998a|pp=90–93}}{{sfn|Chryssides|Zeller|2014|p=321}} Like Troeltsch's "mystical religion", Becker's ''cult'' refers to small religious groups that lack in organization and emphasize the private nature of personal beliefs.{{sfn|Campbell|1998|pp=122–123}}] (1864–1920), an important theorist in the study of cults]]Later sociological formulations built on such characteristics, placing an additional emphasis on cults as ] religious groups, "deriving their inspiration from outside of the predominant religious culture."{{sfn|Richardson|1993|p=349}} This is often thought to lead to a high degree of tension between the group and the more mainstream culture surrounding it, a characteristic shared with religious sects.{{sfn|Stark|Bainbridge|1987|p=25}} According to this sociological terminology, ''sects'' are products of religious ] and therefore maintain a continuity with traditional beliefs and practices, whereas ''cults'' arise spontaneously around novel beliefs and practices.{{sfn|Stark|Bainbridge|1987|p=124}} | |||

| Scholars ] and ] have argued for a further distinction between three kinds of cults: cult movements, client cults, and audience cults, all of which share a "compensator" or rewards for the things invested into the group. In their typology, a "cult movement" is an actual complete organization, differing from a "sect" in that it is not a splinter of a bigger religion, while "audience cults" are loosely organized, and propagated through media, and "client cults" offer services (i.e. psychic readings or meditation sessions). One type can turn into another, for example the ] changing from audience to client cult.{{sfn|Chryssides|Zeller|2014|p=322}} Sociologists who follow their definition tend to continue using the word "cult", unlike most other academics; however Bainbridge later stated he regretted having used the word at all.{{sfn|Chryssides|Zeller|2014|p=322}} Stark and Bainbridge, in discussing the process by which individuals join new religious groups, have even questioned the utility of the concept of '']'', suggesting that '']'' is a more useful concept.{{sfn|Bader|Demaris|1996}} | |||

| # Formal religious veneration | |||

| # A system of religious beliefs and ritual; also: its body of adherents; | |||

| # A religion regarded as unorthodox or spurious; also: its body of adherents; | |||

| # A system for the cure of disease based on dogma set forth by its promulgator; | |||

| # Great devotion to a person, idea, object, movement, or work (as a film or book). | |||

| In the early 1960s, sociologist ] studied the activities of ] members in California in trying to promote their beliefs and win new members. Lofland noted that most of their efforts were ineffective and that most of the people who joined did so because of personal relationships with other members, often family relationships.{{sfn|Richardson|1998}}{{sfn|Barker|1998}} Lofland published his findings in 1964 as a ] entitled "The World Savers: A Field Study of Cult Processes", and in 1966 in book form by as '']''. It is considered to be one of the most important and widely cited studies of the process of religious conversion.{{sfn|Ashcraft|2006|p=180}}{{sfn|Chryssides|1999|p=1}} | |||

| The Random House Unabridged Dictionary definitions are: | |||

| ] stated that, in 1970, "one could count the number of active researchers on new religions on one's hands." However, ] writes that the "meteoric growth" in this field of study can be attributed to the cult controversy of the early 1970s. Because of "a wave of nontraditional religiosity" in the late 1960s and early 1970s, academics perceived new religious movements as different phenomena from previous religious innovations.{{sfn|Lewis|2004}} | |||

| # A particular system of religious worship, esp. with reference to its rites and ceremonies; | |||

| # An instance of great veneration of a person, ideal, or thing, esp. as manifested by a body of admirers; | |||

| # The object of such devotion; | |||

| # A group or sect bound together by veneration of the same thing, person, ideal, etc; | |||

| # Group having a sacred ideology and a set of rites centering around their sacred symbols; | |||

| # A religion or sect considered to be false, unorthodox, or extremist, with members often living outside of conventional society under the direction of a charismatic leader; | |||

| # The members of such a religion or sect; | |||

| # Any system for treating human sickness that originated by a person usually claiming to have sole insight into the nature of disease, and that employs methods regarded as unorthodox or unscientific. | |||

| == Types == | |||

| For authoritative British usage, the Compact Oxford English Dictionary of Current English definitions of "cult" and "sect" are: | |||

| === Destructive cults === | |||

| ''Destructive cult'' is a term frequently used by the ].{{sfn|Chryssides|Zeller|2014|p=322}} Members of the anti-cult movement typically define a destructive cult as a group that is unethical, deceptive, and one that uses "strong influence" or mind control techniques to affect critical thinking skills.{{sfn|Shupe|Darnell|2006|p=214}} This term is sometimes presented in contrast to a "benign cult", which implies that not all "cults" would be harmful, though others apply it to all cults.{{sfn|Chryssides|Zeller|2014|p=322}} ] ], executive director of the anti-cult group ], defines a destructive cult as "a highly manipulative group which exploits and sometimes physically and/or psychologically damages members and recruits."{{sfn|Turner|Bloch|Shor|1995|p=1146}} | |||

| In ''Cults and the Family'', the authors cite Shapiro, who defines a ''destructive cultism'' as a ] ], whose distinctive qualities include: "behavioral and ]s, loss of ], cessation of scholastic activities, estrangement from family, disinterest in society and pronounced mental control and enslavement by cult leaders."{{sfn|Kaslow|Sussman|1982|p=34}} Writing about ] in the book '']'', Julius H. Rubin said that American religious innovation created an unending diversity of sects. These "new religious movements…gathered new converts and issued challenges to the wider society. Not infrequently, public controversy, contested narratives and litigation result."{{sfn|Rubin|2001|p=473}} In his work ''Cults in Context'' author ] writes that although the ] "has not been shown to be violent or volatile," it has been described as a destructive cult by "anticult crusaders."{{sfn|Dawson|1998|p=349}} In 2002, the German government was held by the ] to have ] the ] by referring to it, among other things, as a "destructive cult" with no factual basis.{{sfn|Seiwert|2003}} | |||

| :cult | |||

| ::1 a system of religious worship directed towards a particular figure or object. | |||

| ::2 a small religious group regarded as strange or as imposing excessive control over members. | |||

| ::3 something popular or fashionable among a particular section of society. | |||

| Some researchers have criticized the term ''destructive cult'', writing that it is used to describe groups which are not necessarily harmful in nature to themselves or others. In his book ''Understanding New Religious Movements'', ] writes that the term is overgeneralized. Saliba sees the ] as the "paradigm of a destructive cult", where those that use the term are implying that other groups will also commit ].{{sfn|Saliba|2003|p=144}} | |||

| :sect | |||

| ::1 a group of people with different religious beliefs (typically regarded as heretical) from those of a larger group to which they belong. | |||

| ::2 a group with extreme or dangerous philosophical or political ideas. | |||

| === Doomsday cults === | |||

| British "sect" formerly included a contextually implied meaning, of what "cult" now means | |||

| {{Main|Doomsday cult}} | |||

| <ref>Examples of contemporary British "cult" usage: ; Example of contemporary British "sect" usage: ''"Before beginning counselling the counsellor needs to be sure that it was indeed a cult and not a sect in which the person was enmeshed. A sect may be described as a spin-off from an established religion or quite eclectic, but it does not use techniques of mind control on its membership."'' Cult Information Centre]</ref> | |||

| ''Doomsday cult'' is an expression which is used to describe groups that believe in ] and ], and it can also be used to refer both to groups that predict ], and groups that attempt to bring it about.{{sfn|Jenkins|2000|pp=216, 222}}{{sfn|Chryssides|Zeller|2014|p=322}} In the 1950s, American ] ] and his colleagues observed members of a small ] called the Seekers for several months, and recorded their conversations both prior to and after a failed prophecy from their charismatic leader.{{sfn|Stangor|2004|pp=42–43}}{{sfn|Newman|2006|p=86}}{{sfn|Petty|Cacioppo|1996|p=139}} Their work was later published in the book '']''.{{sfn|Stangor|2004|pp=42–43}} | |||

| in both USA and the UK. Some other nations still use the foreign equivalents of old British "sect" ("secte", "sekte", or "secta", etc.) to imply "cult". Both words, as well as "cult" in its original sense of ] (e.g., Middle Ages ''cult of Mary''), must be understood to correctly interpret 20th century popular cult references in world English. | |||

| In the late 1980s, doomsday cults were a major topic of news reports, with some reporters and commentators considering them a serious threat to society.{{sfn|Jenkins|2000|pp=215–216}} A 1997 psychological study by Festinger, Riecken, and Schachter found that people turned to a cataclysmic ] after they had repeatedly failed to find meaning in mainstream movements.{{sfn|Pargament|1997|pp=150–153, 340}} | |||

| === Theological definition === | |||

| Conservative Christian authors, especially some Protestants, define a cult as a religion which claims to be in conformance with Biblical truth, yet (in their view) deviates from it. By this definition, a cult would be a group which calls itself Christian yet deviates from (what they see as) a core Christian belief, e.g. the Trinity. | |||

| === Political cults === | |||

| {{main|Catholic devotions}} | |||

| A political cult is a cult with a primary interest in ] and ]. Groups that some have described as "political cults", mostly advocating ] or ] agendas, have received some attention from journalists and scholars. In their 2000 book '']'', Dennis Tourish and ] discuss about a dozen organizations in the United States and Great Britain that they characterize as cults.{{sfn|Tourish|Wohlforth|2000}} | |||

| ==Anti-cult movements== | |||

| In theology, particularly ] theology, cult is a ] term, from the Latin, ''colere'', to devote care to a person or thing, that is, to venerate, worship). "Cult" is the root of the term "culture," or ''"the cumulative deposit of knowledge, experience, beliefs, values, attitudes, meanings, hierarchies, religion, notions of time, roles, spatial relations, concepts of the universe, and material objects and possessions acquired by a group of people in the course of generations..."'' . Cult in theology then refers to: | |||

| ===Christian countercult movement=== | |||

| :* Liturgy as the actual arrangement and execution of the public Divine worship as authorized by the Church. The Sacred Congregation of Rites, established by Sixtus V, 1587, as the authoritative organ of the Holy See, is the supreme arbiter. | |||

| {{Main|Christian countercult movement}} | |||

| In the 1940s, the long-held opposition by some established ]s to non-Christian religions and ] or counterfeit Christian sects crystallized into a more organized Christian countercult movement in the United States.{{Citation needed|date=September 2024|reason=what source says it was the 1940s?}} For those belonging to the movement, all religious groups claiming to be Christian, but deemed outside of Christian ], were considered cults.{{sfn|Cowan|2003|p=20}} The countercult movement is mostly evangelical protestants.{{sfn|Chryssides|2024|p=41}} The Christian countercult movement asserts that Christian groups whose teachings deviate from the belief that the bible is inerrant,{{sfn|Cowan|2003|p=31}} but also focuses on non-Christian religions like Hinduism.{{sfn|Chryssides|2024|p=41}} Christian countercult activist writers also emphasize the need for Christians to ] to followers of cults.{{sfn|Cowan|2003|p=25}} | |||

| ===Secular anti-cult movement=== | |||

| :* Part III of the New Code of Canon Law is entitled, "On Divine Cultus." After giving the law governing worship in general (canon 1255) and public worship (canon 1256–1264), the Code gives special laws for the custody and cult of the Blessed Sacrament (canon 1265–1275); for the ] (canon 1276–1289); for sacred processions (canon 1290–1295), and for sacred furniture (canon 1296–1306). | |||

| {{Main|Anti-cult movement}} | |||

| ] protest in Japan, 2009]]Starting in the late 1960s, a different strand of anti-cult groups arose, with the formation of the ] anti-cult movement (ACM).{{sfn|Chryssides|2024|p=46}} This was in response to the rise of new religions in the 1960s and 1970s, particularly the events at ] and the deaths of nearly 1000 people.{{sfn|Chryssides|2024|p=47}} The organizations that formed the secular anti-cult movement (ACM) often acted on behalf of relatives of "cult" ] who did not believe their loved ones could have altered their lives so drastically by their own ]. A few ]s and ]s working in this field suggested that ] techniques were used to maintain the loyalty of cult members.{{sfn|Richardson|Introvigne|2001}}{{sfn|Chryssides|2024|p=46}} | |||

| The belief that cults brainwashed their members became a unifying theme among cult critics and in the more extreme corners of the anti-cult movement techniques like the sometimes forceful "]" of cult members was practised.{{sfn|Shupe|Bromley|1998a|p=27}} In the ], and among average citizens, "cult" gained an increasingly negative connotation, becoming associated with things like ], brainwashing, ], ], and other ], and ]. While most of these negative qualities usually have real documented precedents in the activities of a very small minority of new religious groups, mass culture often extends them to any religious group viewed as culturally ], however peaceful or law abiding it may be.{{sfn|Wright|1997}}{{sfn|van Driel|Richardson|1988}}{{sfn|Hill|Hickman|McLendon|2001}}{{sfn|Richardson|1993|pp=348–356}} | |||

| :* In Hagiology, we must distinguish between public and private cult of the saints. Privately, cult (dulia) can be paid to any deceased of whose holiness we are certain. "Public cult may be shown only to those Servants of God who by the authority of the Church are numbered among the Saints and Beatified" (canon 1277), by the regular processes of canonization and beatification. Canonized saints may receive public cult everywhere and by any act of dulia; the beatified, however, only such acts and in such places as the Holy See permits (canon 1277, § 2). Saints may be chosen with papal confirmation, as patrons of nations, dioceses, provinces, confraternities, and other places and associations. | |||

| While some psychologists were receptive to these theories, sociologists were for the most part sceptical of their ability to explain conversion to ].{{sfn|Barker|1986}} In the late 1980s, psychologists and sociologists started to abandon theories like brainwashing and mind control. While scholars may believe that various less dramatic ] psychological mechanisms could influence group members, they came to see conversion to new religious movements principally as an act of a ].{{sfn|Ayella|1990}}{{sfn|Cowan|2003|p=ix}} | |||

| : Catholic theology makes a distinction between the "cult" (Latin ''cultus''), in its technical sense here, of ''dulia'' and ''latria''. | |||

| ::''']''' is the "honor," "respect," "affection," due to saints -- Mary, as the mother of Christ, is given "]," and traditionally St. Joseph as "foster-father and guardian" of Christ is honored with "]," but in all cases, this dulia is best termed respect and honor. In no way is dulia owed to statues, icons or other depictions of saints, but to the saints themselves, of whom such depictions are mere reminders. This dulia is specifically defined as qualitatively different from 'worship," hence saints are never in fact prayed "to" (despite common inaccuracies of speech), but requested to "pray for us." | |||

| ==Governmental policies and actions== | |||

| ::''']''' is the cult of worship, and this belongs, in Catholic theology, to God alone -- hence, to the Eucharist (as, for Catholics, this is one way that Christ is "truly present") and to each person of the Trinity. In Catholic terminology, God and God alone may be said to be "worshipped" and "adored." | |||

| {{main|Governmental lists of cults and sects}} | |||

| The application of the labels ''cult'' or ''sect'' to religious movements in government documents signifies the popular and negative use of the term ''cult'' in English and a functionally similar use of words translated as 'sect' in several European languages.{{sfn|Richardson|Introvigne|2001|pp=143–168}} Sociologists critical to this negative politicized use of the word ''cult'' argue that it may adversely impact the religious freedoms of group members.{{sfn|Davis|1996}} At the height of the counter-cult movement and ritual abuse scare of the 1990s, some governments published lists of cults.{{efn|Or "sects" in German or French-speaking countries, the German term ''sekten'' and the French term ''sectes'' having assumed the same derogatory meaning as English "cult".}} Groups labelled "cults" are found around the world and range in size from local groups with a few members to international organizations with millions.{{sfn|Barker|1999}} | |||

| While these documents utilize similar terminology, they do not necessarily include the same groups nor is their assessment of these groups based on agreed criteria.{{sfn|Richardson|Introvigne|2001|pp=143–168}} Other governments and world bodies also report on new religious movements but do not use these terms to describe the groups.{{sfn|Richardson|Introvigne|2001|pp=143–168}} Since the 2000s, some governments have again distanced themselves from such classifications of religious movements.{{efn|{{Multiref2 | |||

| === Definition of 'Cult' by Christian 'countercult' groups=== | |||

| |1=Austria: Beginning in 2011, the ]'s ] no longer distinguishes sects in Austria as a separate group. {{Cite web|title=International Religious Freedom Report for 2012|url=https://2009-2017.state.gov/j/drl/rls/irf/religiousfreedom/index.htm?year=2012&dlid=208288|access-date=3 September 2013|publisher=Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor}} | |||

| {{see also|heresy}} | |||

| |2=Belgium: The Justice Commission of the ] published a report on cults in 1997. A Brussels Appeals Court in 2005 condemned the House of Representatives on the grounds that it had damaged the image of an organization listed. | |||

| |3=France: A parliamentary commission of the National Assembly compiled a list of purported cults in 1995. In 2005, the Prime Minister stated that the concerns addressed in the list "had become less pertinent" and that the government needed to balance its concern with cults with respect for public freedoms and ]. | |||

| |4=Germany: The legitimacy of a ] listing cults (''sekten'') was defended in a court decision of 2003 (Oberverwaltungsgericht Berlin 25 September 2003). The list is still maintained by Berlin city authorities: . | |||

| }}}} While the official response to new religious groups has been mixed across the globe, some governments aligned more with the critics of these groups to the extent of distinguishing between "legitimate" religion and "dangerous", "unwanted" cults in ].{{sfn|Richardson|Introvigne|2001}}{{sfn|Edelman|Richardson|2003}} | |||

| === China === | |||

| ], the pioneer of the ] gave in his 1955 book the following definition of a cult: | |||

| {{Main articles|Heterodox teachings (Chinese law)}} | |||

| ] books being symbolically destroyed by the ]]] | |||

| For centuries, governments in China have categorized certain religions as '']'' ({{Zh|c=]|s=|t=|p=|labels=no}}), translated as "evil cults" or "heterodox teachings".{{sfn|Penny|2012}} In ], the classification of a religion as {{Lang|zh-latn|xiejiao}} did not necessarily mean that a religion's teachings were believed to be false or inauthentic; rather, the label was applied to religious groups that were not authorized by the state, or it was applied to religious groups that were believed to challenge the legitimacy of the state.{{sfn|Penny|2012}}{{sfn|Zhu|2010|p=487}} Groups branded ''{{Lang|zh-latn|xiejiao}}'' face suppression and punishment by authorities.{{sfn|Heggie|2020|p=257}}{{sfn|Zhu|2010|p=}} | |||

| : "By cultism we mean the adherence to doctrines which are pointedly contradictory to orthodox Christianity and which yet claim the distinction of either tracing their origin to orthodox sources or of being in essential harmony with those sources. Cultism, in short, is any major deviation from orthodox Christianity relative to the cardinal doctrines of the Christian faith." | |||

| ===Russia=== | |||

| Author ] defines cult as | |||

| In 2008 the ] prepared a list of "extremist groups". At the top of the list were Islamic groups outside of "traditional Islam", which is supervised by the Russian government. Next listed were "]".{{sfn|Soldatov|Borogan|2010|pp=65–66}} In 2009 the ] created a council which it named the "Council of Experts Conducting State Religious Studies Expert Analysis." The new council listed 80 large sects which it considered potentially dangerous to Russian society, and it also mentioned that there were thousands of smaller ones. The large sects which were listed included: ], the ], and other sects which were loosely referred to as "]s".{{sfn|Marshall|2013}} | |||

| === United States === | |||

| : ''"A religious group originating as a heretical sect and maintaining fervent commitment to heresy. Adj.: "cultic" (may be used with reference to tendencies as well as full cult status)."'' {{fn | 33}} | |||

| In the 1970s, the scientific status of the "]" became a central topic in ] cases where the theory was used to try to justify the use of the forceful ] of cult members{{sfn|Lewis|2004}}{{sfn|Davis|1996}} Meanwhile, sociologists who were critical of these theories assisted advocates of ] in defending the legitimacy of new religious movements in court.{{sfn|Richardson|Introvigne|2001}}{{sfn|Edelman|Richardson|2003}} In the United States the religious activities of cults are protected under the ], which prohibits governmental ] and protects ], ], ], and ]; however, no members of religious groups or cults are granted any special ] from ].{{sfn|Ogloff|Pfeifer|1992}} | |||

| In 1990, the ] of ''United States v. Fishman'' (1990) ended the usage of brainwashing theories by expert witnesses such as ] and ]. In the case's ruling, the court cited the ], which states that the ] which is utilized by expert witnesses must be generally accepted in their respective fields. The court deemed ] to be inadmissible in expert testimonies, using supporting documents which were published by the ], literature from previous court cases in which brainwashing theories were used, and expert testimonies which were delivered by scholars such as ].{{sfn|Introvigne|2014|pp=313–316}} | |||

| === Sociological definitions of religion === | |||

| === Western Europe === | |||

| According to what is one common typology among sociologists, religious groups are classified as ]s, ]s, cults or ]s. | |||

| {{See also|MIVILUDES|Union nationale des associations de défense des familles et de l'individu|Parliamentary Commission on Cults in France}} | |||

| The governments of France and Belgium have taken policy positions which accept "brainwashing" theories uncritically, while the governments of other European nations, such as those of Sweden and Italy, are cautious with regard to brainwashing and as a result, they have responded more neutrally with regard to new religions.{{sfn|Richardson|Introvigne|2001|pp=144–146}} Scholars have suggested that the outrage which followed the mass murder/suicides perpetuated by the ], have significantly contributed to European anti-cult positions.{{sfn|Richardson|Introvigne|2001|p=144}}{{sfn|Robbins|2002|p=174}} In the 1980s, clergymen and officials of the French government expressed concern that some ] and other groups within the ] would be adversely affected by anti-cult laws which were then being considered.{{sfn|Richardson|2004|p=48}} | |||

| == See also == | |||

| A very common definition in the sociology of religion for ''cult'' is one of the four terms making up the ]. Under this definition, a cult refers to a religious group with a high degree of tension with the surrounding society combined with novel religious beliefs. This is distinguished from sects, which have a high degree of tension with society but whose beliefs are traditional to that society, and ecclesias and denominations, which are groups with a low degree of tension and traditional beliefs. | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| == References == | |||

| According to ]'s the ''Theory of Religion'', most religions start out their lives as cults or sects, i.e. groups in high tension with the surrounding society. Over time, they tend to either die out, or become more established, mainstream and in less tension with society. Cults are new groups with a new novel theology, while sects are attempts to return mainstream religions to (what the sect views as) their original purity. <ref>Stark, Rodney and Bainbridge, Willia S. ''A Theory of Religion ", Rutgers University Press, ISBN 0-8135-2330-3</ref> | |||

| === Explanatory notes === | |||

| {{notelist}} | |||

| === Citations === | |||

| Since this definition of "cult" is defined in part in terms of tension with the surrounding society, the same group may both be a cult and not a cult at different places and times. For example, Christianity was a cult by this definition in 1st and 2nd century Rome, but in fifth century Rome it is no longer a cult but rather an ecclesia (the state religion). Or similarly, very conservative Islam would (when adopted by Westerners) constitute a cult in the West, but the ecclesia in some conservative Muslim countries (e.g. Saudi Arabia, Iran, Afghanistan under the Taliban). Likewise, because novelty of beliefs as well as tension is an element in the definition: in India, the Hare Krishnas are not a cult, but rather a sect (since their beliefs are largely traditional to Hindu culture), but they are by this definition a cult in the Western world (since their beliefs are largely novel to Christian culture). | |||

| {{reflist}} | |||

| ;Books | |||

| The English sociologist ]<ref>]. ''New Religious Movements: A Practical Introduction'' (1990), Bernan Press, ISBN 0-11-340927-3</ref> argues that a cult is characterized "] individualism" by which he means that "the cult has no clear locus of final authority beyond the individual member." Cults, according to Wallis are generally described as "oriented towards the problems of individuals, loosely structured, tolerant, non-exclusive", making "few demands on members", without possessing a "clear distinction between members and non-members", having "a rapid turnover of membership", and are transient collectives with vague boundaries and fluctuating belief systems Wallis asserts that cults emerge from the "cultic milieu". Wallis contrast a cult with a ] that he asserts are characterized by "] authoritarianism": sects possess some authoritative locus for the legitimate attribution of heresy. According to Wallis, "sects lay a claim to possess unique and privileged access to the truth or salvation and their committed adherents typically regard all those outside the confines of the collectivity as 'in error'". <ref>Wallis, Roy ''The Road to Total Freedom A Sociological analysis of Scientology'' (1976) </ref> <ref>Wallis, Roy ''Scientology: Therapeutic Cult to Religious Sect'' (1975)</ref> | |||

| * {{Cite book|last=Ashcraft |first=W. Michael |year=2006 |chapter=African Diaspora Traditions and Other American Innovations| title=Introduction to New and Alternative Religions in America|publisher=]|isbn=978-0-275-98717-6 |editor-last=Gallagher|editor-first=Eugene V.}} | |||

| * {{Cite book|editor-last1=Wilson |editor-first1=Bryan |editor-last2=Cresswell |editor-first2=Jamie |last=Barker |first=Eileen|author-link=Eileen Barker |chapter=New Religious Movements: their incidence and significance |year=1999 |title=New Religious Movements: Challenge and Response |publisher=]|isbn=978-0-415-20050-9|language=en}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |title=Cults, Religion, and Violence |date=2002 |publisher=] |isbn=978-0-521-66064-8 |editor-last=Bromley |editor-first=David G. |editor-link=David G. Bromley |language=en |editor-last2=Melton |editor-first2=J. Gordon |editor-link2=J. Gordon Melton}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Chryssides |first=George D. |author-link=George D. Chryssides |title=Exploring New Religions |publisher=] |year=1999 |isbn=978-0-304-33652-4 |series=Issues in Contemporary Religion |location=London; New York |language=en}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |title=The Bloomsbury Companion to New Religious Movements |publisher=] |year=2014 |isbn=978-1-4411-9005-5 |editor-last=Chryssides |editor-first=George D. |editor-link=George D. Chryssides |series=Bloomsbury Companions |location=London |language=en |chapter=Resources: A–Z |editor-last2=Zeller |editor-first2=Benjamin E.}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Cowan |first=Douglas E. |author-link=Douglas E. Cowan |year=2003 |title=Bearing False Witness? An Introduction to the Christian Countercult |location=Westport, CT |publisher=] |isbn=978-0-275-97459-6}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Dawson |first=Lorne L. |author-link=Lorne L. Dawson |year=1998 |title=Cults in Context: Readings in the Study of New Religious Movements |publisher=] |isbn=978-0-7658-0478-5}} | |||

| * {{Cite encyclopedia|editor-first=Erwin|editor-last=Fahlbusch|editor-link=Erwin Fahlbusch |editor-first2=Geoffrey W. |editor-last2=Bromiley|editor-link2=Geoffrey W. Bromiley|chapter=Sect|volume=4 |encyclopedia=The Encyclopedia of Christianity|access-date=2013-03-21|page=897 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=C5V7oyy69zgC&pg=PA897 |year=1999|isbn=978-90-04-14595-5 |via=]}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Jenkins |first=Phillip |title=Mystics and Messiahs: Cults and New Religions in American History |title-link=Mystics and Messiahs |publisher=], US |year=2000 |isbn=978-0-19-514596-0}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last1=Kaslow |first1=Florence Whiteman |last2=Sussman|first2=Marvin B. |title=Cults and the Family |publisher=Haworth Press |year=1982 |isbn=978-0-917724-55-8}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Lewis |first=James R. |author-link=James R. Lewis (scholar) |year=2004 |title=The Oxford Handbook of New Religious Movements |location=US |publisher=] |isbn=978-0-19-514986-9}} | |||

| * {{Cite book|last=Marshall |first=Paul |year=2013 |title=Persecuted: The Global Assault on Christians |publisher=]}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Newman |first=Dr. David M. |title=Sociology: Exploring the Architecture of Everyday Life |publisher=Pine Forge Press |year=2006 |isbn=978-1-4129-2814-4}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Pargament |first=Kenneth I. |author-link=Kenneth Pargament |title=The Psychology of Religion and Coping: Theory, Research, Practice |publisher=Guilford Press |year=1997 |isbn=978-1-57230-664-6}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Penny |first=Benjamin |title=The Religion of Falun Gong |date=2012 |publisher=University of Chicago Press |isbn=978-0-226-65501-7 |language=en}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Petty |first=Richard E. |author-last2=Cacioppo|author-first2=John T. |title=Attitudes and Persuasion: Classic and Contemporary Approaches |publisher=Westview Press |year=1996 |isbn=0-8133-3005-X}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Saliba |first=John A. |title=Understanding New Religious Movements |publisher=] |year=2003 |isbn=978-0-7591-0356-6 |edition=2nd |location=Walnut Creek |language=en}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last1=Stark |first1=Rodney |author-link1=Rodney Stark |last2=Bainbridge |first2=William Sims |author-link2=William Sims Bainbridge |year=1987 |title=The Future of Religion: Secularization, Revival and Cult Formation |location=Berkeley |publisher=University of California Press |isbn=978-0-520-05731-9}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last1=Stark |first1=Rodney |author-link1=Rodney Stark |last2=Bainbridge |first2=William Sims |author-link2=William Sims Bainbridge |year=1996 |title=A Theory of Religion |publisher=] |isbn=978-0-8135-2330-9}} | |||

| * {{Cite encyclopedia |editor-last=Swatos |editor-first=William H. Jr. |year=1998 |pages=90–93 |title=Encyclopedia of Religion and Society |publisher=AltaMira |location=Walnut Creek, CA |isbn=978-0-7619-8956-1}} | |||

| ** {{Harvc |last=Shupe |first=Anson |last2=Bromley |first2=David G. |chapter=Anti-Cult Movement |year=1998 |anchor-year=1998a |in=Swatos |url=http://hirr.hartsem.edu/ency/anticult.htm}} | |||

| ** {{Harvc |last=Swatos |first=William H. Jr|chapter=Church-Sect Theory|year=1998 |anchor-year=1998a |in=Swatos |url=http://hirr.hartsem.edu/ency/cstheory.htm}} | |||

| ** {{Harvc |last=Campbell |first=Colin |chapter=Cult |year=1998 |in=Swatos |url=http://hirr.hartsem.edu/ency/cult.htm}} | |||

| ** {{Harvc |last=Barker |first=Eileen |chapter=Conversion |year=1998 |in=Swatos |url=http://hirr.hartsem.edu/ency/conversion.htm}} | |||

| ** {{Harvc |last=Richardson |first=James T. |chapter=Unification Church |year=1998 |in=Swatos |url=http://hirr.hartsem.edu/ency/Unification.htm}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |title=Regulating Religion: Case Studies from Around the Globe |publisher=] |year=2004 |isbn=978-0-306-47887-1 |editor-last=Richardson |editor-first=James T. |editor-link=James T. Richardson |series=Critical Issues in Social Justice |location=New York |language=en}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last1=Shupe |first1=Anson |title=Agents of Discord: Deprogramming, Pseudo-science, and the American Anti-cult Movement |last2=Darnell |first2=Susan |date=2006 |publisher=Transaction Publishers |isbn=978-0-7658-0323-8}} | |||

| * {{Cite book|author-link=Andrei Soldatov|last1=Soldatov |first1=Andreĭ|first2=I. |last2=Borogan |year=2010|title=The new nobility : the restoration of Russia's security state and the enduring legacy of the KGB| location=New York|publisher=] |isbn=978-1-61039-055-2}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Stangor |first=Charles |title=Social Groups in Action and Interaction |publisher=Psychology Press |year=2004 |isbn=978-1-84169-407-8}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last1=Stein |first1=Alexandra |title=Terror, Love and Brainwashing: Attachment in Cults and Totalitarian Systems |publisher=Taylor and Francis |year=2016 |isbn=9781138677951}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |title='Cult' Rhetoric in the 21st Century: Deconstructing the Study of New Religious Movements |publisher=] |year=2024 |isbn=978-1-350-33323-9 |editor-last=Thomas |editor-first=Aled |series=Religion at the boundaries |location=London |language=en |editor-last2=Graham-Hyde |editor-first2=Edward}} | |||

| ** {{Harvc |last=Thomas |first=Aled |last2=Graham-Hyde |first2=Edward. |author-link=George D. Chryssides |chapter='Cult' rhetoric in the twenty-first century: The disconnect between popular discourse and the ivory tower |year=2024 |in=Thomas |in2=Graham-Hyde |anchor-year=2024a}} | |||

| ** {{Harvc |last=Chryssides |first=George D. |author-link=George D. Chryssides |chapter=A history of anticult rhetoric |year=2024 |in=Thomas |in2=Graham-Hyde}} | |||

| ** {{Harvc |last=Dubrow-Marshall |first=Roderick P. |chapter=The recognition of cults |year=2024 |in=Thomas |in2=Graham-Hyde}} | |||

| ** {{Harvc |last=Crockford |first=Susannah |chapter='There is no QAnon': Cult accusations in contemporary American political and online discourse |year=2024 |in=Thomas |in2=Graham-Hyde}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last1=Tourish |first1=Dennis |last2=Wohlforth |first2=Tim |author-link2=Tim Wohlforth |year=2000 |title=On the Edge: Political Cults Right and Left |title-link=On the Edge: Political Cults Right and Left |location=Armonk |publisher=] |isbn=978-0-7656-0639-6}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last1=Turner |first1=Francis J. |first2=Arnold Shanon |last2=Bloch |last3=Shor |first3=Ron |title=Differential Diagnosis & Treatment in Social Work |edition=4th |publisher=Free Press |year=1995 |page=1146 |chapter=105: From Consultation to Therapy in Group Work With Parents of Cultists |isbn=978-0-02-874007-2}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |title=Misunderstanding Cults: Searching for Objectivity in a Controversial Field |title-link=Misunderstanding Cults |publisher=] |year=2001 |isbn=978-0-8020-8188-9 |editor-last=Zablocki |editor-first=Benjamin |editor-link=Benjamin Zablocki |language=en |editor-last2=Robbins |editor-first2=Thomas |editor-link2=Thomas Robbins (sociologist)}} | |||

| ** {{Harvc |first=Julius H. |last=Rubin |chapter=Contested Narratives: A Case Study of the Conflict between a New Religious Movement and Its Critics |year=2001 |in=Zablocki |in2=Robbins}} | |||

| ;Articles | |||

| === Definition of 'Cult' according to secular opposition === | |||

| * {{Cite journal |doi=10.1177/0002764290033005005 |last=Ayella |first=Marybeth |year=1990 |title=They Must Be Crazy: Some of the Difficulties in Researching 'Cults' |journal=American Behavioral Scientist |volume=33 |issue=5 |pages=562–577 |s2cid=144181163}} | |||

| * {{Cite journal| doi = 10.2307/1386560| issn = 0021-8294| volume = 35| issue = 3| pages = 285–303| last1 = Bader| first1 = Chris| last2 = Demaris| first2 = Alfred| title = A Test of the Stark-Bainbridge Theory of Affiliation with Religious Cults and Sects| journal = Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion| date = 1996 |jstor = 1386560}} | |||

| Secular cult opponents define a "cult" | |||

| * {{Cite journal |last=Barker |first=Eileen |year=1986 |title=Religious Movements: Cult and Anti-Cult Since Jonestown |journal=Annual Review of Sociology |volume=12 |pages=329–346 |doi=10.1146/annurev.so.12.080186.001553}} | |||

| as a religious or non-religious group that tends to manipulate, exploit, and control its members. Here are two definitions by ] and ], scholars who are widely recognized among the secular cult opposition: | |||

| * {{Cite journal| volume = 11| issue = 1| pages = 145–172| last = Davis| first = Dena S| title = Joining a Cult: Religious Choice or Psychological Aberration| journal = Journal of Law and Health| date = 1996}} | |||

| * {{Cite journal| doi = 10.2307/3711011| issn = 0038-0210| volume = 49| issue = 2| pages = 171–183| last1 = van Driel| first1 = Barend| last2 = Richardson| first2 = James T.| title = Categorization of New Religious Movements in American Print Media| journal = Sociological Analysis| date = 1988| jstor = 3711011}} | |||

| : ''Cults are groups that often exploit members psychologically and/or financially, typically by making members comply with leadership's demands through certain types of psychological manipulation, popularly called '']'', and through the inculcation of deep-seated anxious dependency on the group and its leaders.''{{fn | 1}} | |||

| * {{Cite journal |doi=10.1525/nr.2003.6.2.312 |last1=Edelman |first1=Bryan |last2=Richardson |first2=James T. |year=2003 |title=Falun Gong and the Law: Development of Legal Social Control in China |journal=Nova Religio |volume=6 |issue=2 |pages=312–331}} | |||

| * {{Cite journal |last=Heggie |first=Rachel |date=2020 |title=When Violence Happens: The McDonald's Murder and Religious Violence in the Hands of the Chinese Communist Party |journal=Journal of Religion and Violence |volume=8 |issue=3 |pages=253–280 |doi=10.5840/jrv202131682 |issn=2159-6808 |jstor=27212326}} | |||

| : ''"A cult is a group or movement exhibiting a great or excessive devotion or dedication to some person, idea or thing and employing unethically manipulative techniques of persuasion and control (e.g. isolation from former friends and family, debilitation, use of special methods to heighten suggestibility and subservience, powerful group pressures, information management, suspension of individuality or critical judgement, promotion of total dependency on the group and fear of leaving it, etc) designed to advance the goals of the group's leaders to the actual or possible detriment of members, their families, or the community." ''{{fn | 8}} | |||

| * {{Cite journal| doi = 10.2307/3512241| issn = 0034-673X| volume = 43| issue = 1| pages = 24–38| last1 = Hill| first1 = Harvey| last2 = Hickman| first2 = John| last3 = McLendon| first3 = Joel| title = Cults and Sects and Doomsday Groups, Oh My: Media Treatment of Religion on the Eve of the Millennium| journal = Review of Religious Research| date = 2001| jstor = 3512241}} | |||

| * {{Cite journal |last1=Introvigne |first1=Massimo |title=Advocacy, brainwashing theories, and new religious movements |journal=Religion |volume=44 |issue=2 |pages=303–319 |doi=10.1080/0048721X.2014.888021 |year=2014 |s2cid=144440076}} | |||

| ] has attempted to address the issue of multiple definitions of "cult"<ref></ref>. | |||

| * {{Cite journal|last1=Ogloff|first1= J. R.|last2=Pfeifer|first2=J. E.|title= Cults and the law: A discussion of the legality of alleged cult activities.|journal= Behavioral Sciences & the Law|year= 1992|volume= 10|issue= 1|pages= 117–140|doi= 10.1002/bsl.2370100111}} | |||

| * {{Cite journal| issn = 0021-8294| volume = 45| issue = 1| pages = 97–106| last = Olson| first = Paul J.| title = The Public Perception of "Cults" and "New Religious Movements"| journal = Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion| date = 2006| doi = 10.1111/j.1468-5906.2006.00008.x| jstor = 3590620}} | |||

| The common anti-cult definition summarised, | |||

| * {{Cite journal |last1=Richardson |first1=James T. |last2=Introvigne |first2=Massimo |author-link2=Massimo Introvigne |year=2001 |title='Brainwashing' Theories in European Parliamentary and Administrative Reports on 'Cults' and 'Sects'. |journal=] |volume=40 |number=2 |pages=143–168 |doi=10.1111/0021-8294.00046}} | |||

| * {{Cite journal |last=Richardson |first=James T. |author-link=James T. Richardson |year=1993 |title=Definitions of Cult: From Sociological-Technical to Popular-Negative. |journal=] |volume=34 |pages=348–356 |doi=10.2307/3511972 |jstor=3511972 |number=4}} | |||

| * Manipulative and authoritarian mind control over members | |||

| * {{Cite journal |last=Seiwert |first=Hubert |date=2003 |title=Freedom and Control in the Unified Germany: Governmental Approaches to Alternative Religions Since 1989 |journal=Sociology of Religion |volume=64 |issue=3 |pages=367–375 |doi=10.2307/3712490 |issn=1069-4404 |jstor=3712490}} | |||

| * Communal and totalistic in their organisation | |||

| * {{Cite journal |doi=10.1111/0021-8294.00047 |last=Robbins |first=Thomas |year=2002 |title=Combating 'Cults' and 'Brainwashing' in the United States and Europe: A Comment on Richardson and Introvigne's Report |journal=Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion |volume=40 |issue=2 |pages=169–176}} | |||

| * Aggressive in proselytizing | |||

| * {{Cite journal |last1=Stark |first1=Rodney |last2=Bainbridge |first2=William Sims |date=1980 |title=Networks of Faith: Interpersonal Bonds and Recruitment to Cults and Sects |journal=] |language=en |volume=85 |issue=6 |pages=1376–1395 |doi=10.1086/227169 |issn=0002-9602 |jstor=2778383}} | |||

| * Systematic program of indoctrination | |||

| * {{Cite journal |last1=Weber |first1=Max |title="Churches" and "Sects" in North America: An Ecclesiastical Socio-Political Sketch |journal=Sociological Theory |date=Spring 1985 |volume=3 |issue=1 |pages=7–13 |doi=10.2307/202166 |jstor=202166 |language=en}} | |||

| * New membership of cults by middle class | |||

| * {{Cite journal| doi = 10.2307/3512176| issn = 0034-673X| volume = 39| issue = 2| pages = 101–115| last = Wright| first = Stuart A.| title = Media Coverage of Unconventional Religion: Any "Good News" for Minority Faiths?| journal = Review of Religious Research| date = 1997| jstor = 3512176}} | |||

| * {{Cite journal |last=Zhu |first=Guobin |date=2010 |title=Prosecuting "Evil Cults:" A Critical Examination of Law Regarding Freedom of Religious Belief in Mainland China |journal=Human Rights Quarterly |volume=32 |issue=3 |pages=471–501 |doi=10.1353/hrq.2010.0004 |issn=0275-0392 |jstor=40784053}} | |||

| === Definition of 'cult' in popular culture === | |||

| In his book ''In Our Time'', ] defines a cult as a religion without political power. | |||

| == Differing opinions of the various definitions == | |||

| Unlike popular definitions, sociological definitions exclude considerations of harm and abuse and are not used in a pejorative manner. | |||

| According to professor ] from the ], in his 2003 ''Religious Movements in the United States'', during the controversies over the new religious movements in the 1960s, the term "cult" came to mean something sinister, generally used to describe a movement that was at least potentially destructive to its members or to society, or that took advantage of its members and engaged in unethical practices. But he argues that no one yet has been able to define "cult" in a way that enables the term to identify only problematic groups. Miller asserts that the attributes of cults (see ]), as defined by cult opponents, can be found in groups that few would consider cultic, such as ] religious orders or many ] ] churches. Miller argues: | |||

| <blockquote> | |||

| If the term does not enable us to distinguish between a pathological group and a legitimate one, then it has no real value. It is the religious equivalent of "]"—it conveys disdain and prejudice without having any valuable content.{{fn | 31}} | |||

| </blockquote> | |||

| <!-- "cults" are usually defined by ] by a list of attributes they possess (see ]), but that such attributes are perfectly capable of belonging to groups that few would consider "cultic", such as ] religious orders or many ] ] churches. Miller further argues that if the term does not enable the distinction between a pathological group and a legitimate one, then it has no value and it is in fact the religious equivalent of "]": it conveys disdain and prejudice without having any valuable content.{{fn | 31}} --> | |||

| Due to the usually pejorative connotation of the word "cult", new religious movements (NRMs) and other purported cults often find the word highly offensive. Some purported cults have been known to insist that other similar groups are cults but that they themselves are not. On the other hand, some ] have questioned the distinction between a cult and a mainstream religion. They say that the only difference between a cult and a ] is that the latter is older and has more followers and, therefore, seems less controversial because society has become used to it. See also '']'' and '']''. | |||

| == The cult debate== | |||

| This section describes a ] sociological phenomenon known as the ''cult debate'' also called ''cult war''. | |||

| === History of debate === | |||

| As the ] wound down in the early 1970s, and the US public's preoccupation with the ] declined, a new ''idée fixe'' arose in its place: what it saw as the menace of cults.{{fact}} | |||

| Throughout the decade, various organizations both dangerous (] "The Family") and harmless{{fact}} (]) came to the forefront of debate over the changing mores of US society. Newspapers and broadcast news, as well as religious leaders and parents who worried over losing their teenaged and college-aged children to the ] of the ] and 70s, frequently focused attention on groups they described as "dangerous cults." <sup title="The text in the vicinity of this tag needs citation." class="noprint">[]]</sup>{{#if: {{NAMESPACE}} || }} | |||

| While some of these groups were, in fact, notoriously criminal, engaging in behavior such as murder (Manson), kidnapping and armed robbery (]), prostitution and child sexual abuse (]), and enforced separation from family members (various), others were culpable of nothing more "dangerous" than ] of into religious faiths or groups whose doctrines seemed unfamiliar, strange or even ] to outsiders. <sup title="The text in the vicinity of this tag needs citation." class="noprint">[]]</sup>{{#if: {{NAMESPACE}} || }} Some of the groups that entered the national cult debate in the early and mid 1970s were ] (est), ]).<sup title="The text in the vicinity of this tag needs citation." class="noprint">[]]</sup>{{#if: {{NAMESPACE}} || }}, ], the ], and ] (TM). | |||

| === Connotative change === | |||

| During the period, the word "cult" lost its traditional meaning (a system of religious worship) and came to be associated with concepts such as ], ], coercive ] and ]. <sup title="The text in the vicinity of this tag needs citation." class="noprint">[]]</sup>{{#if: {{NAMESPACE}} || }} | |||

| These negative associations were cemented in 1978 with the Reverend ] and the mass suicide of members of the ]. | |||

| During this period, certain religious clerics and lay members of some ] Christian groups ], and began using the term "cult" as a pejorative to describe any religious faith group whose doctrines or theology were different from their own. <sup title="The text in the vicinity of this tag needs citation." class="noprint">[]]</sup>{{#if: {{NAMESPACE}} || }} Members of "]" ministries began publishing and distributing disparaging checklists with titles such as "Checklist of Cult Characteristics", , , where each entry on the checklist described unique beliefs or doctrines of a target religious faith. By disparaging doctrines such as ] or ], these groups attempted to calumniate even large, established faiths such as ] and ] with the label "cult." <sup title="The text in the vicinity of this tag needs citation." class="noprint">[]]</sup>{{#if: {{NAMESPACE}} || }} | |||

| === Post-debate change === | |||

| Acknowledging the now-disparaging connotation of the once-useful term "cult," some scholars of religion and sociology began in the 1980s to use the term "]" to describe smaller and newer religious faith groups. Whilst not in common use -- due in some measure to its unwieldy name -- the newer term has wide currency in the academic community, including amongst religious scholars.{{fact}} | |||

| == Non-Religious Cults == | |||

| According to the ], although the majority of groups to which the word "cult" is applied are religious in nature, a significant number are non-religious. These may include political, psychotherapeutic or ] oriented cults that are organized in a manner very similar to their religious counterparts. The term has also been applied to certain channelling, human-potential and self-improvement organizations, some of which do not define themselves as religious movements although they clearly draw on ideas derived from various religions. | |||

| The political cults, mostly far-leftist or far-rightist in their ideologies, have received considerable attention from journalists and scholars but are only a minute percentage of the total number of cults in the United States. Indeed, clear documentation of cult-like practices exists for only about a dozen ideological cadre or racial combat organizations, although vague charges have been leveled at a somewhat larger number. See Dennis Tourish and Tim Wohlforth, "On the Edge: Political Cults Right and Left," Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2000. | |||

| The idea seen in political discussions that is closest to the idea of a political cult is that of a ]. The idea of a political cult tends to invalidate any strong or committed belief in any political system, policy, or leader, and thus raises philosophical questions about the nature of society. | |||

| Although most ]s involve a "]", the latter concept is a broader one. It has its origins in the excessive adulation said to have surrounded Soviet leader ]. It has also been applied to several other despotic heads of state. It is often applied by analogy to refer to adulation of non-political leaders, and sometimes in the context of certain businessmen, management styles, and company work environments. The use of this term in its broadest sense serves as a reminder that cultic phenomena (as opposed to full-blown "cults") are not just found inside small ashrams and splinter churches but also are spread throughout mainstream institutions in democratic societies as well as permeating in a far more toxic form the governments and ruling parties of some nondemocratic societies. | |||

| == Societal and Governmental Pressures == | |||

| {{not verified}} | |||

| American novelist and critic ] gave the definition of cult as a religion which has no political power, implying that there is no functional difference between religions and cults except their acceptance within the general community and the way they are perceived by others. Many majoritarian religions generally have their doctrinal tenets legitimized by society in one way or another (and by the state in some countries although not in most modern democracies), while groups with non-mainstream beliefs may experience social and media disapproval either permanently (if their beliefs and practices are just too unorthodox) or until either the group, or society, or both, evolve in a converging way resulting in a higher level of social acceptance.{{fact}} | |||

| In the 19th century ] (the Mormons) were singled out by the U.S. government, which even sent the U.S. Army against them in 1857. This military action has been referred to as the ] although no battles occurred. The US Army's charge was to depose ] as Governor of the Utah Territory and install a more acceptable, non-Mormon individual, ]. The motivation for this action was a rumor that the Mormons were planning to rebel against the United States government. When it became clear that the rumor was false and that ] had ordered military action without verifying his sources, the incident became known as "Buchanan's Blunder." | |||

| The question of social acceptance should not be confused, however, with that of governmental acceptance. Most governmental clashes with cult-like groups in the United States in recent years have been the result of real or perceived violations of the law by the groups in question. There have been no well documented recent cases of the U.S. government persecuting a supposedly cult-like group simply because of its religious or political beliefs (as opposed to its alleged illegal ''acts''), although several groups have claimed such persecution. (Of course, it is possible that negative perceptions of a group by prosecutors could make them more quick to prosecute than they might otherwise be; for instance, in the income tax case against Reverend Moon.)<ref>Sherwood, Carlton (1991) Inquisition: The Persecution and Prosecution of the Reverend Sun Myung Moon. Washington, D.C.: Regnery (ISBN 0-89526-532-X)</ref> | |||

| In addition, the United States has never had an established church. Groups widely regarded as cults or as having non-mainstream beliefs have often found it easy to gain political clout; for instance, the ] (by way of its influential newspaper, the Washington Times), and ] (by way of its Hollywood connections, which some observers have suggested gave it clout with the Clinton administration).{{fact}} | |||

| A 1996 French Parliamentary Commission issued a , in which a list of purported cults compiled by the general information division of the ] (]) was reprinted. In it were listed 173 groups, including ], the Theological Institute of Nîmes (an ] Christian Bible college), and the ]. Members of some of the groups included in the list have alleged instances of intolerance due to the ensuing negative publicity. Although this list has no statutory or regulatory value, it is at the background of the criticism directed at France with respect to freedom of religion. | |||

| The "Interministerial Mission in the Fight Against Sects/Cults" was formed in 1998 to coordinate government monitoring of sect . In February 1998 MILS released its annual report on the monitoring of sects. The president of MILS resigned in June under criticism and an interministerial working group was formed to determine the future parameters of the Government's monitoring of sects. In November the Government announced the formation of the Interministerial Monitoring Mission Against Sectarian Abuses , which is charged with observing and analyzing movements that constitute a threat to public order or that violate French law, coordinating the appropriate response, informing the public about potential risks, and helping victims to receive aid. In its announcement of the formation of MIVILUDES, the Government acknowledged that its predecessor, MILS, had been criticized for certain actions abroad that could have been perceived as contrary to religious freedom. On May 2005, former prime minister Jean-Pierre Raffarin issued a circular indicating that the list of cults published on the parliamentary report of 1966 should no longer be used to identify cults. <ref></ref> | |||

| == Study of cults == | |||

| Among the experts studying cults and new religious movements are sociologists, religion scholars, psychologists, and psychiatrists. To an unusual extent for an academic/quasi-scientific field, however, nonacademics are involved in the study of and/or debates concerning cults, especially from the anti-cult point of view. These include investigative journalists and nonacademic book authors (who sometimes make positive contributions by methods such as examining court records and studying the finances of cults, which academics are not accustomed to doing), writers who once were members of purported cults, and professionals who work with ex-cult members in a practical way (for instance, as therapists) but are not university affiliated. Less widely known are the writings by members of organizations that have been labelled cults, defending their organizations and replying to their critics (such works are less well known, in part, because they have to contend against popular conceptions of cults and also because they are usually published by the purported cult itself rather than by mainstream publishers). | |||

| Nonacademics are sometimes published, or their writings cited, in the ''Cultic Studies Journal'' (''CSJ''), the journal of the ] (ICSA), a group that is strongly critical of cults. In addition, nonacademics, including former cult members, lawyers who have litigated against cults, psychotherapists who treat former cult members, and others with personal knowledge or experiences, often give presentations at ICSA conferences. It should be noted that sociologist Janja Lalich began her work and conceptualized many of her ideas while an ex-cult activist writing for the "CSJ" years before obtaining academic standing, and incorporated her own experiences in a leftwing political cult into her later work as a sociological theorist. | |||

| For better or worse, the hundreds of books on specific cults by nonacademic critics (as well as the hundreds by current members defending or elaborating their organization's doctrines) comprise a large portion of the currently available published record on cults. The books by cult critics run the gamut from memoirs by ex-members, which may take the form either of thoughtful analyses or of "cult captivity" narratives (or a bit of both), to detailed accounts of the history and alleged misdeeds of a given group written from either a tabloid journalist, investigative journalist, or popular historian perspective. | |||

| The work of several non-academic cult authors is cited in this article. Journalists ] and ] wrote the book '']'', which set forth speculations on how mind control works that have been criticized by some psychologists and praised by others. Others mentioned in this article include Tim Wohlforth (co-author of ''On the Edge'' and a former follower of ]); Carol Giambalvo, a former ] member; activist and consultant ]; and mental health counselor ], a former ] member and author of the book '']''. Another example is the work of journalist/activist ], without whom the study of "political cults" might scarcely exist today. Barbara G. Harrison's ''Vision of Glory: A History and a Memory of Jehovah's Witnesses'', can be regarded as an example of a serious study by an ex-cult member (she was raised as a Witness) whose thinking transcends the cult captivity genre. Current members of the ] movement as well as several former leaders of the ] also have written with critical insight on cult issues, using terminologies and framings somewhat different from those of secular experts but well within the circle of rational discourse. Members of the ] have produced books and articles that argue the case against excessive reactions to new religious movements, including their own, with intellectual rigor and a sense of history. | |||

| Within this larger community of discourse, the debates about cultism and specific cults are generally more polarized than among scholars who study new religious movements, but there are heated disagreements among scholars as well. What follows is a summary of that portion of the intellectual debate conducted primarily from inside the universities: | |||

| === Cult, NRM, and the sociology and psychology of religion === | |||

| The problem with defining the word ''cult'' is that (1) the word ''cult'' is often used to marginalize religious groups with which one does not agree or sympathize, and (2) accused cult members generally resist being called a cult. Nearly all academic researchers of ] and ] prefer to use the term '']'' (NRM) in their research on religious groups that may be referred to as cults by other academics, non-academics and the media. However, some researchers have stated{{fact}} that this is an imperfect replacement for the term cult because some religious movements are "new" but not necessarily cults, and have expanded the definition of cult to include those which are not religious or overtly religious. Furthermore, some religious groups commonly regarded as cults are in fact no longer particularly "new"; for instance, ] and the ] are both over 50 years old; and the ] came out of ], a religious tradition that is approximately 500 years old. | |||

| When a group (and generally one with teachings regarded as out of the mainstream) practices physical or mental abuse, some mental health professionals may use the term ''cult''. Others prefer more descriptive terminology such as ''abusive cult'' or '']''. Since cult critics using these terms rarely mention any alleged cults ''except'' abusive ones, their use of the two terms is in effect redundant. The popular press also commonly uses these terms. | |||

| Not all sectarian groups labeled as cults or as "cult-like", function abusively or destructively to any degree greater than many mainstream social institutions, however, and even among those cults that psychologists believe ''are'' abusive to an exceptional degree, few members (as opposed to some ex-members) would agree that they have suffered abuse. Other researchers like David V. Barrett hold the view that classifying a religious movement as a cult is generally used as a subjective and negative label and has no added value; instead, he argues that one should investigate the beliefs and practices of the religious movement.{{fn | 9}} | |||

| Some groups, particularly those labeled by others as cults, view the designation as insensitive and may feel persecuted by opponents; those opponents may in fact be affiliated with organizations that are self-defined as anti-cult (or strongly critical of cults). <ref>A discussion and list of ACM (anti-cult movement) groups can be found at .</ref> Even when no affiliation with such a group exists, the opponents of a particular cult will usually be influenced to varying degrees by the ]'s ideas — which are summarized in this article in the sections "Definition by secular cult opposition" and "Definition by Christian anti-cult movement." | |||

| Groups accused of being "cults" or "cult-like" often defend their position by comparing themselves to more established, mainstream religious groups such as ] and ]. The argument offered can usually be simplified as, "except for size and age, Christianity and Judaism meet all the criteria for a cult, and therefore the term ''cult'' simply means ''small, young religion''." | |||

| According to the Dutch religious scholar ], another problem with writing about cults comes about because they generally hold ]s that give answers to questions about the meaning of ] and ]. This makes it difficult not to write in biased terms about a certain cult, because writers are rarely neutral about these questions. In an attempt to deal with this difficulty, some writers who deal with the subject choose to explicitly state their ethical values and belief systems. | |||

| For some scholars, psychologists and researchers, the usage of the word "cult" applies to groups perceived as exhibiting a pattern of abusive and over-controlling behavior towards members, and not to a belief system. For members of competing religions, use of the word remains undeniably pejorative and applies primarily to rival beliefs (see ]s), and only incidentally to behavior. It should be noted that there is no clear, causal connection between extremist belief and the formation of a destructive cult. Most far-right hate groups are not cults, although they have pathological ideas and are frequently violent. Some groups regarded as cults have relatively benign belief systems. | |||

| In the sociology of religion, the term cult is part of the subdivision of religious groups: sects, cults, denominations, and ecclesias. The sociologists ] and William S. Bainbridge define cults in their book, ] and subsequent works, as a "deviant religious organization with novel beliefs and practices", that is, as ]s that (unlike ]s) have not separated from another religious organization. Cults, in this sense, may or may not be dangerous, abusive, etc. By this broad definition, most of the groups which have been popularly labeled cults fit this value-neutral definition. | |||

| === Related Research === | |||

| The following research examines phenomena related to people's reactions to groups identified as some other form of social outcast or opposition group. It relates to the visceral opposition that some religious groups evoke in their opponents. | |||

| === Reactions to Social Out-Groups === | |||

| A new study by Princeton University psychology researchers Lasana Harris and Susan Fiske shows that when viewing photographs of social out-groups, people respond to them with disgust, not a feeling of fellow humanity. The findings are reported in the article "Dehumanizing the Lowest of the Low: Neuro-imaging responses to Extreme Outgroups" in a forthcoming issue of Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science (previously the American Psychological Society). | |||

| According to this research, social out-groups are perceived as unable to experience complex human emotions, share in-group beliefs, or act according to societal norms, moral rules, and values. The authors describe this as "extreme discrimination revealing the worst kind of prejudice: excluding out-groups from full humanity." Their study provides evidence that while individuals may consciously see members of social out-groups as people, the brain processes social out-groups as something less than human, whether we are aware of it or not. According to the authors, brain imaging provides a more accurate depiction of this prejudice than the verbal reporting usually used in research studies. | |||

| === Political Partisans and Closed-Mindedness === | |||

| Recent research reveals that political partisans ignore facts that contradict their own sense of reality, according to a report on research by ], director of clinical psychology at ] | |||