| Revision as of 16:57, 5 May 2021 editTiamut (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers31,614 edits →Inscription: copy edit← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 14:18, 20 November 2024 edit undoRyanW1995 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users29,505 editsmNo edit summaryTag: 2017 wikitext editor | ||

| (31 intermediate revisions by 10 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Contains special characters|cuneiform}} | |||

| ]]] | ]]] | ||

| '''Hadad-yith'i''' ( |

'''Hadad-yith'i''' ({{langx|oar|{{script|Armi|𐡄𐡃𐡉𐡎𐡏𐡉}}|Hadd-yiṯʿī}}, {{langx|akk|𒁹𒌋𒀉𒀪|translit=Adad-itʾī}}) was governor of ] and Sikani in northern ] (c. 850 BCE). A client king or vassal of the ], he was the son of Sassu-nuri, who also served as governor before him. Knowledge of Hadad-yith'i's rule comes largely from the statue and its inscription found at the ].<ref name=Vande/> Known as the ], as it is written in both ] and ], its discovery, decipherment and study contributes significantly to cultural and linguistic understandings of the region.<ref name=Fales>Fales, 2011, pp. 563–564.</ref> | ||

| ==Statue== | ==Statue & inscription== | ||

| {{main|Hadad-yith'i bilingual inscription}} | |||

| The life-size basalt statue of a male standing figure carved in Assyrian style was uncovered by a Syrian farmer in February 1979 at the edge of |

The life-size basalt statue of a male standing figure carved in Assyrian style was uncovered by a Syrian farmer in February 1979 at the edge of Tell Fekheriye on a branch of the ] opposite ], identified with ancient Guzana.<ref>{{cite web|last1=Millard|first1=Alan|title=Hadad-yith'i|url=http://referenceworks.brillonline.com/entries/context-of-scripture/hadad-yith-i-2-34-aCOSB_2_34|website=referenceworks.brillonline.com|publisher=Editor in Chief: W. Hallo|access-date=3 December 2014}}</ref> Most stone statues discovered and documented as belonging to the Neo-Assyrian period depict either the kings of Assyria or its gods. The statue of Hadad-yith'i, lacking in royal marks or insignia, is one of only three known stone statues from this period bearing images of figures of lesser rank or reverence.<ref>{{cite journal|last1= Roobaert|first1= Arlette|title= A Neo-Assyrian Statue from Til Barsib|journal= Iraq|date=1996|volume=58|page=83|doi= 10.1017/S0021088900003181|jstor=4200420}}</ref> | ||

| Based on the stylistic features of the statue, it has been tentatively dated to the mid- |

Based on the stylistic features of the statue, it has been tentatively dated to the mid-ninth century BCE, though it could be as old as 11th century when considering the archaic traits of several graphemes used in the Old Aramaic script.<ref name=Fales/> | ||

| The name of the inscription's commissioner is recorded as Adad Itʾi/Hadad Yithʿī, and dedicates the statue to the temple in Sikanu of the storm god ], a deity worshipped throughout Syria and ] at the time.<ref name=Cathcart>Cathcart, 1996, p. 141.</ref> | |||

| ===Inscription=== | |||

| The statue bears the most extensive bilingual inscription in Akkadian and Aramaic, and is the oldest Aramaic inscription of such length.<ref name=Vande>Van de Mieroop, 2015, p. 241.</ref> It records the name of its commissioner as King Adad It'i (Hadad Yith'i), and dedicates the statue to the storm god ], a deity worshipped throughout Syria and ] at the time. The inscription declares that the god Hadad is the king Hadad Yith'i's lord, by whose blessing he rules. It also notably contains the Aramaic words for "image" (selem) and "likeness" (demut), thus furnishing an ancient and extra-biblical attestation for the terminology used in Genesis 1:26 on the ].<ref name=Bandstra>Bandstra, 2008, p. 44.</ref><ref name=Middleton>Middleton, 2005, pp. 106 – 207</ref> | |||

| The statue bears the most extensive bilingual inscription in Akkadian and Aramaic, and is the oldest Aramaic inscription of such length.<ref name=Vande>Van de Mieroop, 2015, p. 241.</ref> The inscription also contains a curse against those who would efface Hadad Yithʿī's name from the Hadad temple, invoking Hadad not to accept the offerings of those who did so.<ref name=Levine>Levine, 1996, p. 112.</ref> | |||

| "Whoever removes my name from the objects of the temple of Adad, my lord, may my lord Adad not accept his food and drink offerings, may my lady ] not accept his food and drink offerings. May he sow but not reap. May he sow a thousand (measures), but reap only one. May one hundred ewes not satisfy one spring lamb, may one hundred cows not satisfy one calf, may one hundred women not satisfy one child, may one hundred bakers not fill up one oven! May the gleaners glean from rubbish pits! May illness, plague and insomnia not disappear from his land!"<ref name=Vande/> | |||

| ==Name, meaning, root== | ==Name, meaning, root== | ||

| Hadad |

Hadad Yithʿī is an ] name, and the Akkadian version of the name in the bilingual inscription is transcribed as Adad Itʾi.<ref name=MB1>Millard & Boudreuil, Summer 1982.</ref> That the Aramaic has an "s" in place of the "t" in ''Itʾi'', thus ''ysʿy'', is an indication of how the name was vocalized in Aramaic.<ref name=Fitzmyer/> | ||

| ⚫ | The second part of the king's name, ''Yithʿī'', is a derivation of an ancient ] meaning "to save", so that the translation of the full name into English is "Hadad is my salvation".<ref name=MBn>"The second element contains the same base as certain ancient names in Hebrew, Ugaritic, and Old South Arabic. This is y-sh-' in Hebrew, seen in Joshua (=Jesus) meaning to 'to save'. Thus the name means 'Hadad is my salvation.'" (Millard & Boudreuil, Summer 1982.)</ref> | ||

| This name is significant in Semitic studies because it establishes beyond a doubt the existence of Aramaic personal names based on and derived from the root ''yṯʿ'' "to help, save".<ref name=MBn/><ref name=Lipinski>Lipinski, 1975, p. 40.</ref> Prior to this decipherment, and that of another Aramaic inscription discovered in Qumran, scholars thought that the verbal root parallelt to {{lang|he|ישע}}, often identified as the root for the names ] and ], existed only in ], and did not exist in Aramaic.<ref name=Fitzmyer>Fitzmyer, 2000, pp. 123 – 125.</ref><ref name=MBn/> | |||

| ⚫ | The second part of the king's name is a derivation of an ancient ] meaning "to save", so that the translation of the full name into English is "Hadad is my salvation".<ref name=MBn>"The second element contains the same base as certain ancient names in Hebrew, Ugaritic, and Old South Arabic. This is y-sh-' in Hebrew, seen in Joshua (=Jesus) meaning to 'to save'. Thus the name means 'Hadad is my salvation.'" (Millard & Boudreuil, Summer 1982.)</ref> | ||

| More discoveries and decipherments of ancient Semitic inscriptions have since uncovered dozens of other examples based on this ] ''yṯʿ'', the earliest of these being from 2048 BCE in the ] personal name ''lašuil''.<ref name=Aitken>Aitken & Davies, 2016. Also note: "The Aram. name hdys'y (Akk. adad-it-'i) in ll. 1, 6 and 12 of the Tell Fekheriye bilingual inscription, probably of the mid-ninth century, can plausibly be associated with the root yṯ'/ישׁע (see initially Abou-Assaf et al. 1982: 43-44, 80: more recent bibliography in Millard 2000: 154). ישׁע is a loan-word in Aramaic found in the Prayer of ] (Milik 1956:413) and in the ] (Sokoloff 1990: ad loc.). Aramaized forms of two ] names are found in the ] (Noth 1928:154–55, 176).</ref> | |||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| Line 30: | Line 31: | ||

| ==Bibliography== | ==Bibliography== | ||

| * {{cite |

* {{cite web|url=http://www.sahd.div.ed.ac.uk/_media/lexeme:pdf:flu-yasa%CA%BF-aitken_davies-cam-2016.pdf |author=Aitken, James K. |author2=Graham Davies|website=Semantics of Ancient Hebrew Database|script-title=he:יָשַׁ ע|year=2016}} | ||

| * {{cite book|url=https://books.google. |

* {{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=VfoGAAAAQBAJ&q=adad+iti&pg=PA44|title=Reading the Old Testament: Introduction to the Hebrew Bible|author=Bandstra, Barry L. |year=2008|publisher=Cengage Learning|isbn=978-1111804244}} | ||

| *{{cite book|title=Targumic and Cognate Studies: Essays in Honour of Martin McNamara|author= Cathcart, Kevin J. |editor=Kevin J. Cathcart |editor2=Michael Maher |editor3=Martin McNamara|year=1996}} | |||

| ⚫ | *{{cite book| title=The Dead Sea Scrolls and Christian Origins|author=Joseph |

||

| *{{cite book|author=MF |

*{{cite book|author=Fales, MF |title=Old Aramaic|year=2011|pages=555–573}} | ||

| ⚫ | *{{cite book| title=The Dead Sea Scrolls and Christian Origins|last=Fitzmyer|first=J.|author-link=Joseph Fitzmyer|publisher=Wm. B. Eerdmann's Publishing|year=2000|isbn=9780802846501|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=9d6gq_bR1AIC&q=millard+aramaic+root+iti&pg=PA124}} | ||

| * Albert K. |

* Grayson, Albert K. (1991). Assyrian civilization. J.Boardman et al., 194-228. | ||

| *{{cite book|title=Go to the Land I Will Show You: Studies in Honor of Dwight W. Young|editor=Joseph E. Coleson |

*{{cite book|title=Go to the Land I Will Show You: Studies in Honor of Dwight W. Young |editor=Joseph E. Coleson |editor2=Victor Harold Matthews |editor3=Dwight W. Young|author=Levine, B.A. |author-link=Baruch A. Levine|publisher=Eisenbrauns|year=1996}} | ||

| *{{cite book|url=https://books.google. |

*{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ra0QmH4np4kC&q=millard+yt+aramaic+root&pg=PA40| title=Studies in Aramaic Inscriptions and Onomastica II|author=Lipinski, E.|author-link=Edward Lipiński (orientalist)|publisher=Peeters Publishers|year=1975| isbn=9789068316100}} | ||

| *{{cite book|title=The Liberating Image: The Image Deio in Genesis I|year=2005|author=J. Richard |

*{{cite book|title=The Liberating Image: The Image Deio in Genesis I|year=2005|author=Middleton, J. Richard |publisher=Brazos Press|isbn=9781441242785|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=OXmKAAAAQBAJ&q=adad+iti&pg=PA106}} | ||

| * ] |

* ], (2014) Context of Scripture Online. Editor in Chief: W. Hallo. BrillOnline, Retrieved 6 December 2014. | ||

| * {{cite journal|journal=Biblical Archaeologist| |

* {{cite journal|journal=Biblical Archaeologist|date=Summer 1982|author1=Millard, A.R.|author-link1= Alan Millard|author2= P. Bordreuil|title=A Statue from Syria with Assyrian and Aramaic Inscriptions|volume=45|issue=3|pages=135–141|doi=10.2307/3209808|jstor=3209808}} | ||

| ⚫ | *{{cite book|author=Marc Van de Mieroop|url=https://books.google. |

||

| ⚫ | * Roobaert, Arlette (1996) "A Neo-Assyrian Statue From Til Barsib." British Institute for the Study of Iraq 58: 83. Retrieved 27 November 2014. | ||

| ⚫ | * {{cite journal|journal= |

||

| ⚫ | *{{cite book|author=Van de Mieroop, M.|author-link=Marc Van de Mieroop|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=L9bECQAAQBAJ&q=adad+hadad+yith%27i&pg=PA241|title=A History of the Ancient Near East: 3000 – 332 BC|year=2015|publisher=John Wiley & Sons|isbn=9781118718162}} | ||

| ⚫ | * Arlette |

||

| ⚫ | * {{cite journal|journal=Bibliotheca Orientalis |volume=68 |issue=5–6|date=September–December 2011|author=Zukerman, Alexander |title=Titles of 7th Century BCE Philistine Rulers and their Historical-Cultural Background}} | ||

| ] | ] | ||

Latest revision as of 14:18, 20 November 2024

Hadad-yith'i (Old Aramaic: 𐡄𐡃𐡉𐡎𐡏𐡉, romanized: Hadd-yiṯʿī, Akkadian: 𒁹𒌋𒀉𒀪, romanized: Adad-itʾī) was governor of Guzana and Sikani in northern Syria (c. 850 BCE). A client king or vassal of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, he was the son of Sassu-nuri, who also served as governor before him. Knowledge of Hadad-yith'i's rule comes largely from the statue and its inscription found at the Tell Fekheriye. Known as the Hadad-yith'i bilingual inscription, as it is written in both Old Aramaic and Akkadian, its discovery, decipherment and study contributes significantly to cultural and linguistic understandings of the region.

Statue & inscription

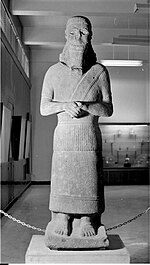

Main article: Hadad-yith'i bilingual inscriptionThe life-size basalt statue of a male standing figure carved in Assyrian style was uncovered by a Syrian farmer in February 1979 at the edge of Tell Fekheriye on a branch of the Khabur opposite Tell Halaf, identified with ancient Guzana. Most stone statues discovered and documented as belonging to the Neo-Assyrian period depict either the kings of Assyria or its gods. The statue of Hadad-yith'i, lacking in royal marks or insignia, is one of only three known stone statues from this period bearing images of figures of lesser rank or reverence.

Based on the stylistic features of the statue, it has been tentatively dated to the mid-ninth century BCE, though it could be as old as 11th century when considering the archaic traits of several graphemes used in the Old Aramaic script.

The name of the inscription's commissioner is recorded as Adad Itʾi/Hadad Yithʿī, and dedicates the statue to the temple in Sikanu of the storm god Hadad, a deity worshipped throughout Syria and Mesopotamia at the time.

The statue bears the most extensive bilingual inscription in Akkadian and Aramaic, and is the oldest Aramaic inscription of such length. The inscription also contains a curse against those who would efface Hadad Yithʿī's name from the Hadad temple, invoking Hadad not to accept the offerings of those who did so.

Name, meaning, root

Hadad Yithʿī is an Aramaic name, and the Akkadian version of the name in the bilingual inscription is transcribed as Adad Itʾi. That the Aramaic has an "s" in place of the "t" in Itʾi, thus ysʿy, is an indication of how the name was vocalized in Aramaic.

The second part of the king's name, Yithʿī, is a derivation of an ancient Semitic root meaning "to save", so that the translation of the full name into English is "Hadad is my salvation".

This name is significant in Semitic studies because it establishes beyond a doubt the existence of Aramaic personal names based on and derived from the root yṯʿ "to help, save". Prior to this decipherment, and that of another Aramaic inscription discovered in Qumran, scholars thought that the verbal root parallelt to ישע, often identified as the root for the names Jesus and Joshua, existed only in Biblical Hebrew, and did not exist in Aramaic.

More discoveries and decipherments of ancient Semitic inscriptions have since uncovered dozens of other examples based on this triliteral root yṯʿ, the earliest of these being from 2048 BCE in the Amorite personal name lašuil.

See also

References

- ^ Van de Mieroop, 2015, p. 241.

- ^ Fales, 2011, pp. 563–564.

- Millard, Alan. "Hadad-yith'i". referenceworks.brillonline.com. Editor in Chief: W. Hallo. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- Roobaert, Arlette (1996). "A Neo-Assyrian Statue from Til Barsib". Iraq. 58: 83. doi:10.1017/S0021088900003181. JSTOR 4200420.

- Cathcart, 1996, p. 141.

- Levine, 1996, p. 112.

- Millard & Boudreuil, Summer 1982.

- ^ Fitzmyer, 2000, pp. 123 – 125.

- ^ "The second element contains the same base as certain ancient names in Hebrew, Ugaritic, and Old South Arabic. This is y-sh-' in Hebrew, seen in Joshua (=Jesus) meaning to 'to save'. Thus the name means 'Hadad is my salvation.'" (Millard & Boudreuil, Summer 1982.)

- Lipinski, 1975, p. 40.

- Aitken & Davies, 2016. Also note: "The Aram. name hdys'y (Akk. adad-it-'i) in ll. 1, 6 and 12 of the Tell Fekheriye bilingual inscription, probably of the mid-ninth century, can plausibly be associated with the root yṯ'/ישׁע (see initially Abou-Assaf et al. 1982: 43-44, 80: more recent bibliography in Millard 2000: 154). ישׁע is a loan-word in Aramaic found in the Prayer of Nabonidus (Milik 1956:413) and in the targum (Sokoloff 1990: ad loc.). Aramaized forms of two Biblical Hebrew names are found in the Elephantine papyri (Noth 1928:154–55, 176).

Bibliography

- Aitken, James K.; Graham Davies (2016). יָשַׁ ע (PDF). Semantics of Ancient Hebrew Database.

- Bandstra, Barry L. (2008). Reading the Old Testament: Introduction to the Hebrew Bible. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1111804244.

- Cathcart, Kevin J. (1996). Kevin J. Cathcart; Michael Maher; Martin McNamara (eds.). Targumic and Cognate Studies: Essays in Honour of Martin McNamara.

- Fales, MF (2011). Old Aramaic. pp. 555–573.

- Fitzmyer, J. (2000). The Dead Sea Scrolls and Christian Origins. Wm. B. Eerdmann's Publishing. ISBN 9780802846501.

- Grayson, Albert K. (1991). Assyrian civilization. J.Boardman et al., 194-228.

- Levine, B.A. (1996). Joseph E. Coleson; Victor Harold Matthews; Dwight W. Young (eds.). Go to the Land I Will Show You: Studies in Honor of Dwight W. Young. Eisenbrauns.

- Lipinski, E. (1975). Studies in Aramaic Inscriptions and Onomastica II. Peeters Publishers. ISBN 9789068316100.

- Middleton, J. Richard (2005). The Liberating Image: The Image Deio in Genesis I. Brazos Press. ISBN 9781441242785.

- Millard, A., (2014) Context of Scripture Online. Editor in Chief: W. Hallo. BrillOnline, Retrieved 6 December 2014.

- Millard, A.R.; P. Bordreuil (Summer 1982). "A Statue from Syria with Assyrian and Aramaic Inscriptions". Biblical Archaeologist. 45 (3): 135–141. doi:10.2307/3209808. JSTOR 3209808.

- Roobaert, Arlette (1996) "A Neo-Assyrian Statue From Til Barsib." British Institute for the Study of Iraq 58: 83. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- Van de Mieroop, M. (2015). A History of the Ancient Near East: 3000 – 332 BC. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781118718162.

- Zukerman, Alexander (September–December 2011). "Titles of 7th Century BCE Philistine Rulers and their Historical-Cultural Background". Bibliotheca Orientalis. 68 (5–6).