| Revision as of 04:00, 28 January 2007 editE104421 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users3,783 edits see talk page!← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 02:24, 3 December 2024 edit undoKepler-1229b (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users18,409 edits →Cultural and linguistic theoriesTag: Visual edit | ||

| (685 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Ancient Siberian culture}} | |||

| The '''Dingling'''/Gaoche/Chile/Tiele (丁零/高車/敕勒/铁勒, conventionally spelled '''Dinlin''') are Europoid people who in the 1st millennium BC and 1st millenium AD lived in the terrotory of the ]-] mountains, ], and ] west of ] in ancient So.]<ref>L.N.Gumilev, "History of Hun People", 'Eastern Literature', 1960, http://gumilevica.kulichki.net/HPH/hph16.htm Dictionary of Ethnonyms</ref><ref>L.N.Gumilev, "History of Hun People", 'Eastern Literature', 1960, http://gumilevica.kulichki.net/HPH/hph02.htm Ch. 2. Refugees in the Steppes</ref>. Ancient Chinese viewed the northern edge of desert Gobi as the native land of Dinlins<ref>L.N.Gumilev, "History of Hun People", 'Eastern Literature', 1960, http://gumilevica.kulichki.net/HPH/hph01.htm Ch. 1 In the Dimness of Centuries</ref>. Chinese used the term "Dinlin" as a metaphor underlining the Europoidness as distinctive feature<ref>L.N.Gumilev, "Hunnu in China", 'Eastern Literature', 1973, Ch. 1, http://gumilevica.kulichki.net/HIC/hic01.htm </ref>. | |||

| {{About||the writer|Ding Ling|the tomb|Dingling (Ming)}} | |||

| {{More citations needed|date=May 2010}} | |||

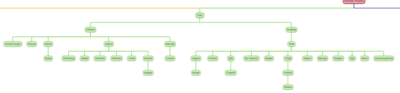

| {{Continental Asia in 100 BCE|right|The ''Dingling'' and contemporary Asian polities circa 100 BCE.|{{Annotation|153|40|]}}}} | |||

| The '''Dingling'''{{efn|{{lang-zh|c=丁零}} (174 BCE); {{lang|zh|丁靈}} (200 BCE); ]: *''teŋ-leŋ'' < ]: *''têŋ-rêŋ''}} were an ancient people who appear in ] in the context of the 1st century BCE. | |||

| The Dingling are considered to have been an early ].<ref> | |||

| Dinlins are described as of average height, frequently tall, stout and strong constitution, with elongated face, white skin with rosy cheeks, blond hair, straight nose protruding forward, frequently hawk nose, light eyes. This description, drawn from the written sources, is also confirmed by archeology. Sayan-Altai was an aboriginal land of the ] ] dated approximately from 2000 BC. Anthropologically the ] are a distinct race. They had sharply protruding nose, relatively low face, low eye-sockets, wide forehead, all these attributes indicate their belonging to the European trunk. From modern Europeans the Afanasievs differ by considerably wider face. In that respect they are alike the Upper-Paleolithic ] skulls of the Western Europe. The successors of the Afanasievs were the tribes of ] who lived until the 3rd century BC. The Afanasievs-Dinlins carried their culture across centuries, despite invasions of very different tribes<ref>L.N.Gumilev, "History of Hun People", 'Eastern Literature', 1960, Ch. 2 Refugees in the Steppes http://gumilevica.kulichki.net/HPH/hph02.htm</ref>. | |||

| ]: . Cambridge University Press, 2013. pp.175-176.</ref><ref> | |||

| Peter B. Golden: in ''Contact and Exchange in the Ancient World''. Ed. Victor H. Mair. University of Hawaii Press, 2006. p.140</ref> They were also proposed to be the ancestors of ] among the later ],<ref name = "XTS219">] " txt: "室韋, 契丹别種, 東胡之北邊, 蓋丁零苗裔也" translation by Xu (2005:176) "The Shiwei, who were a collateral branch of the Khitan inhabited the northern boundary of the Donghu, were probably the descendants of the Dingling ... Their | |||

| language was the same as that of the Mohe."</ref><ref name = "Xu176">Xu Elina-Qian, , University of Helsinki, 2005. p. 176. quote: "The Mohe were descendants of the Sushen and ancestors of the Jurchen, and identified as Tungus speakers."</ref> or are related to ] and ] speakers.<ref>Werner, Heinrich ''Zur jenissejisch-indianischen Urverwandtschaft''. Harrassowitz Verlag. 2004 . </ref> | |||

| Modern archaeologists have identified the Dingling as belonging to the ], namely the ].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Hartley |first1=Charles W. |last2=Yazicioğlu |first2=G. Bike |last3=Smith |first3=Adam T. |title=The Archaeology of Power and Politics in Eurasia: Regimes and Revolutions |date=19 November 2012 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-1-139-78938-7 |page=245 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=1mcgAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA245 |language=en}} "The Dinlin are considered to have been part of the Tagar Culture and are mentioned in the written sources as being among the acquired "possessions" of the Huns (Mannai—Ool 1970: 107; Sulimirski 1970: 112)."</ref> | |||

| '''Dinlins''' were already around during the time of the ] Empire. | |||

| ==Origin and migration== | |||

| The '''Dingling'''s were a numerous, warlike, vital ethnos of hunters, fishers, and gatherers of the southern Siberian mountain taiga from the ] to ]. They dominated this area for millennia, from the Neolithic down to the founding of the ] Confederacy. Along the edges of the retreating glaciers, among grazing herds of game animals like mammoth, bison, elk, reindeer, musk ox, etc., a large part of the proto-Dingling gradually wandered along the streams of the ], ] and ], all the way to the ] coast, and further to ]. Another group of this ethnos migrated toward the northwest in the watersheds of the ], ] and ]. | |||

| In Chinese chronicles, the ''Dingling'' usually correspond with tribe's name like ''Gaoche'', ''Chile'' and ''Tiele'', and in many chronicles they were considered to be the former Dinglings under commentaries made in the later era. The Dingling are no longer mentioned by the ] and gradually replaced. According to the '']'', one group of Dingling escaped to the western steppe in Kazakhstan while the remaining Dingling became absorbed into various ] peoples known as the Gaoche, and later, the Tiele. Groups such as Xueyantuo (Syr-Tardush), Basmil (Ch. Baximi), ] (Ch. Wuhu), ] (Ch. Weihu), and the northern most ] (Guligan) from the Lake Baikal are the Tiele tribes. Section of a typical extract from the ] volume 84: | |||

| {{list to prose (section)}} | |||

| <blockquote>The forebear of the Tiele belonged to those of ] descendants, and had the largest divisions of tribes. They occupied along the valleys, scattering in the vast region west to the ] : | |||

| <br> | |||

| #At the area north of the Duluo River , are the Pugu, Tongluo, Weihu , Bayegu, Fuluo, which are composited into the Sijin legion, other tribes such as Mengchen, Turuhu, Sijie, Hun, Hu, Xue and so forth, also dwelled in this area. They have a 20,000 invincible armies. | |||

| #In the regions west of ] , the north of ] , near the edge of the ] , come to the abodes of Qipi, Boluozhi, Yizhi, Supo, Nahe, ] , ] , Yezhi, Yunihu and so forth. They have a 20,000 invincible armies. | |||

| #After passing the south west from the ] , are the Xueyantuo , Zhileer, ] , Daqi and so forth. They have a 10,000 invincible armies. | |||

| #Leaving these, we come to the regions north of ] , near the river of ] , here, dwell the Hezhi, Bahu, ] , Juhai, Hebixi, Hecuo, Suba, Yemo, Keda and so forth. They have a 30,000 invincible armies. | |||

| #At the western portion, from the east to the west of the ] , are the Sulu, ] , Suoye, Miecu, Longhu and so forth. They have a 8,000 invincible armies. | |||

| #Until we reach to the east of ] , are the Enqu, ] , Beiru, Jiuli, Fuwahun and so forth. They have a nearly 20,000 invincible armies. | |||

| #And lastly, in the regions south of the ] , dwell the ] and also some other tribes. | |||

| <br> | |||

| The names of these tribes are different, but all of them can be classified as Tiele. The Tiele don't have a master, they are subjected to the both Eastern and Western ] separately. They don't have permanent residence, and moved with the changes of grass and water. Their main characteristics are: they possessed great ferocity, and yet showed tolerance, they were good ] and ], and they showed greed without restraint, for they often made their living by looting. These tribes toward the west were more cultivated, for they bred ] and ], but fewer ]s. Since the ] had established a state, they were recruited as the auxiliary of empire and conquered both east and westard, thus annexing all of the northern regional lands. | |||

| <br> | |||

| <br> | |||

| The customs of the Tiele and ] are not much different. However a man of the Tiele lives in his wife's home after marriage and will not return to his own home with his wife until the birth of a child. In addition, the Tiele also bury their dead under the ground.</blockquote> | |||

| ==Etymology== | ==Etymology== | ||

| The ethnonym 'Dingling' is regarded by modern scholars in the Western world as being interchangeable with the ethnonym ], who are believed to be the descendants of the Dingling.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Wang |first1=Penglin |title=Linguistic Mysteries of Ethnonyms in Inner Asia |date=28 March 2018 |publisher=Lexington Books |isbn=978-1-4985-3528-1 |page=5 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=mOdRDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA5 |language=en}} "Dingling is alternatively called Tiele. Suishu and Beishi, both of which were written during the seventh century during the Tang period, traced the origin of the Tiele or Dingling back to Xiongnu."</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Hickman |first1=Bill |last2=Leiser |first2=Gary |title=Turkish Language, Literature, and History: Travelers' Tales, Sultans, and Scholars Since the Eighth Century |date=14 October 2015 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-317-61295-7 |page=149 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Goy9CgAAQBAJ&pg=PA149 |language=en}} "...the Dingling 丁零, Old Chin. (before 200 BCE): *têŋ-rêŋ > Late Han (after 200 BCE to 200 CE): teŋ leŋ,32 a tribal union north of the Xiongnu, viewed as ancestral to the Tiele and possibly an early rendering of that ethnonym."</ref> Chinese historiographers believed that 'Tiele' was a mistaken transcription, related them to the ancient Red ] (狄翟), and recorded various names like Dili (狄历), Gaoche (高車) or Chile (敕勒).<ref>'']'' "高車,蓋古赤狄之餘種也,初號為狄歷,北方以為勑勒,諸夏以為高車、丁零。" tr. "Gaoche, probably the remnant stock of the ancient Red ]. Initially, they had been called Dili; northerners considered them to be Chile; the ] (i.e. Chinese) considered them to be Gaoche Dingling (i.e. Dingling with High Cart)"</ref><ref>] "回紇,其先匈奴也,俗多乘高輪車,元魏時亦號高車部,或曰敕勒,訛為鐵勒。" tr: "], their predecessors were the Xiongnu. Because, customarily, they ride high-wheeled carts. In ] time, they were also called Gaoche (i.e. High-Cart) tribe. Or called Chile, or mistakenly as Tiele."</ref> | |||

| Although the words ''dingling'', ''gaoche'', ''chile'' and ''tiele'' (as in modern ] pronunciation of ] romanisation) are often used interchangeably, this usage is erroneous as pointed out by modern academia. Dingling refers to an extinct ethnic group. The Gaoche was an ethnic-tribe that expelled by ] from ] and founded a state (]-]) at ], which was descended in part from the Dingling. The Tiele was a collection of tribes of different ] ethnic-origins which largely descended from the Chile. All four groups somewhat happened to occupy quite a similar geographical area in succession of each other with an exception for the first one. | |||

| Several modern scholars, including ], now believe that all of these ethnonyms described by the Chinese all derive from Altaic exonyms describing wheeled vehicles, with 'Dingling' perhaps being an earlier rendering of a Tuoba word (*tegreg), meaning "wagon".<ref>{{cite book |last1=Tasar |first1=Eren |last2=Frank |first2=Allen J. |last3=Eden |first3=Jeff |title=From the Khan's Oven: Studies on the History of Central Asian Religions in Honor of Devin DeWeese |date=11 October 2021 |publisher=BRILL |isbn=978-90-04-47117-7 |page=5 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4stKEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA5 |language=en}} "The latter were part of the Tiĕlè union, earlier termed the ''Gāochē'' "High Carts" (Liu, 1985, I:127--128; Pulleyblank, 1990: 21-26; Dobrovitz, 2011: 375-378), and before that the Dīnglíng, perhaps a rendering of *''tegreg'' "wagon", a Tuoba/Tabgač exonym for Tiele (Kljaštornyj, 2010: 162-163; Golden, 2012 : 179-180.)"</ref> | |||

| ==Language== | |||

| According to ] linguist experts on ], proposed that probably, the Proto-Dinglings spoke a ] with an ] ], and exhibited, linguistically and culturally, a unified ethnic community. Heinrich Werner's ''Zur jenissejisch-indianischen Urverwandtschaft'', (''Concerning Yeniseian-Indian Word Origins'') developed a new genealogical concept, which he terms “Baikal-Siberic,”in which the ] peoples (], ], ], ], ], and ]), the ] “Indians,” and the Ding-ling folk of the ancient Chinese chronicles can all be traced back to “Proto-Dingling.” The linguistic comparison of Na-Dene and Yeniseian shows that the quantity and character of the correspondences point unequivocally to common origin (Urverwandtschaft).” | |||

| Peter Golden also wrote that "Gaoche" or "high carts" may be a translation of "''Dingling'' et al.".<ref>{{cite book |last1=Cosmo |first1=Nicola Di |last2=Maas |first2=Michael |title=Empires and Exchanges in Eurasian Late Antiquity: Rome, China, Iran, and the Steppe, ca. 250–750 |date=26 April 2018 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-1-108-54810-6 |page=326 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=y01UDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA326 |language=en}} "55 Chinese accounts of the Northern Wei era also termed them Gaoche “high carts,” seemingly a translation of Dingling et al.: E. G. Pulleyblank, “The 'High Carts': A Turkish Speaking People before the Türks,” ''Asia Major'' 3.1 (1990) 21–26."</ref> ] writes that "High Cart" is just one of several variations of exonyms that ultimately reflect the original Turkic meaning of 'Dingling', which is possibly derived from *Tägräg, meaning "circle, hoop".<ref>{{cite journal |last1=PULLEYBLANK |first1=EDWIN G. |title=The "High Carts": A Turkish-Speaking People Before the Türks |journal=Asia Major |date=1990 |volume=3 |issue=1 |page=22 |jstor=41645442 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/41645442 |issn=0004-4482}} "The name Ting-ling continued to be used occasionally but other forms soon became more common. One is the Chinese Kao-ch'e "High Carts," which is explained as referring to their wagons with very large wheels. The others, Ti-li, T'e-le, Ch'ih-le, Chih-le, and T'ieh-le,4 which are obviously transcriptions of foreign names, are evidently new transcriptions of the name that underlay Ting-ling. James Hamilton proposes to interpret this as *Tägräg, a word defined in Kashgari's dictionary as "circle, hoop."5 The Chinese term "High Carts" was therefore probably not merely descriptive of their habits but related to the meaning of the Turkish name."</ref> | |||

| Ding-ling can be seen to resemble (1) the Yeniseian word *dzheng ‘people’ > Ket de?ng, Yug dyeng, Kott cheang; and (2) the Na-Dene word *ling or *hling ‘people’, as manifested in the name of the ] (properly hling-git ‘son of man, child of the people’), etc. | |||

| == Origin and migration == | |||

| ==Anthropology== | |||

| ] | |||

| The ''Weilüe'' mentioned three Dingling groups:<ref>Yu Huan, ''Weilüe'', quoted in ], ], , draft translation by John E. Hil 2004 </ref> | |||

| *one group south of Majing (馬脛, literally: "Horse-Shank"), north of ], and west of ]; | |||

| *another south of the North Sea, identified as ]; | |||

| *and another north of ] and neighbouring the Qushi (屈射), Hunyun (渾窳), ] (隔昆), and ] (薪犁), all of whom had once been conquered by the Xiongnu.<ref>] '']'' "後北服渾庾、屈射、丁零、鬲昆、薪犁之國。於是匈奴貴人大臣皆服,以冒頓單于爲賢。" tr. "Later north subjugated the nations of Hunyu, Qushe, Dingling, Gekun, and Xinli. Therefore, the Xiongnu nobles and dignitaries all admired considered Modun ] as capable."</ref> | |||

| Murphy (2003) proposes that the Dingling's country had been in the ] on the ],<ref>{{cite book |last1=Murphy |first1=Eileen M. |title=Iron Age Archaeology and Trauma from Aymyrlyg, South Siberia |date=2003 |publisher=Archaeopress |isbn=978-1-84171-522-3 |page=16 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=iiFmAAAAMAAJ&q=%22the+country+of+Dinlin%2C+which+was+located+in+the+Minusinsk+Basin+on+the+Yenisey+river%22|language=en}} "...the country of Dinlin , which was located in the Minusinsk Basin on the Yenisey river."</ref> thus close to the location of the Dingling group who neighbored the Kangju, Wusun, and Majing people. Dingling gradually moved southward to ] and ]. They were a huge independent horde for centuries, but were later defeated and temporarily became subject of the ] Empire,<ref>Lu (1996), pp. 111, 135-137.</ref><ref>Li (2003), pp. 110-112.</ref> and thus presumably related to the invaders known as ] in the west.<ref>A. J. Haywood, , Oxford University Press, 2010, p.203</ref> One group, known as the West Dingling, remained in an area that would become ], while others – expelled from ] by the ] – settled in the ] during the 5th century and took control of ]. | |||

| In antiquity in Eastern Asia were two ] races of the 2-nd order, ] and ]. The dolichocranial Dinlins of ] type lived in So.Siberia since prehistoric times<ref>Debets G.F. Paleontology of USSR. М., 1948, p. 65</ref>. Chinese in antiquity called the Sayan mountains Dinlin, emphasizing location of the strange people <ref>L.N.Gumilev, "Hunnu in China", 'Eastern Literature', 1973, Ch. 1, http://gumilevica.kulichki.net/HIC/hic01.htm </ref>. The presence of different type Europoids, dolichocranial Dinlins in Siberia and long-headed brachicranial Di in China shows two branches of the European racial trunk from different racial types, they were similar, but not identical. The southern branch of Dinlins, coaching south from Sayan mountains, intermixed with the ancestors of the ], and Chinese noted high noses to be a distinctive attribute of the Huns<ref>L.N.Gumilev, "History of Hun People", 'Eastern Literature', 1960, Ch. 2 Refugees in the Steppes http://gumilevica.kulichki.net/HPH/hph02.htm</ref>. | |||

| ] cart from ]. The tall wheels of this cart are related to those used by the Dingling and other Turkic nomads, which provides evidence of cultural continuity between the Scythians and the Turkic peoples.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Andrews |first1=Peter A. |title=Felt Tents and Pavilions: The Nomadic Tradition and Its Interaction with Princely Tentage |date=1999 |publisher=Melisende |isbn=978-1-901764-03-1 |page=89 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=AD1SAAAAMAAJ&q=pazyryk+high+cart+confederacy |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Bloom |first1=Jonathan |last2=Blair |first2=Sheila S. |last3=Blair |first3=Sheila |title=Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art & Architecture: Three-Volume Set |date=14 May 2009 |publisher=OUP USA |isbn=978-0-19-530991-1 |page=281 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=un4WcfEASZwC&pg=RA2-PA281 |language=en}} "...among the Hsiung-nu and the High Cart confederation. Since the Turkic type, with its dependence on wood bending techniques, can be related to bent wooden wheels (c. 350 bce) found in barrow No. V at Pazyryk in Siberia, deriving from a tradition a millennium older, the connection with these cart dwelling nomads is significant."</ref>]] | |||

| The Dingling had a warlike society, formed by traders, hunters, fishers, and gatherers, living a semi-nomadic life in the ] mountain ] region from ] to northern Mongolia. Some ancient sources claims that Di or Zhai (翟) was adopted as the group name because the Zhai family had been the ruling house for centuries.<ref>Xue (1992), pp. 54-60.</ref><ref>Lu (1996), pp. 305-320.</ref><ref>Duan (1988) pp. 35-53.</ref> | |||

| Anthropologically, in the antique time the ] short-headed type were intermixing with Chinese ] narrow-faced type. The Mongoloid wide-faced type at that time was located to the north from ]. From analysis of the historical events it is clear that the difference of Dinlins and Di from the Chinese inside China and from Huns outside of it was obvious to the contemporaries<ref>L.N.Gumilev, "History of Hun People", 'Eastern Literature', 1960, Ch. 1 In the Dimness of Centuries http://gumilevica.kulichki.net/HPH/hph01.htm</ref>. | |||

| Other sources claim that they might have been correlated with the ], a northern tribe that appears in the ] inscriptions from ].<ref>Duan (1988) pp. 8-11.</ref> | |||

| L.N. Gumilev gives a fascinating description of the Hun ancestry, noting that northern Chinese type is different from the Mongolian type, the Chinese are narrow-faced, thin, slender, and the Mongols are wide-cheeked, short, stout. The composition of the Huns defined the Huns' character, Dinlin's high noses and fierceness was combined with the Chinese love of order, and with the Mongolian endurance<ref>L.N.Gumilev, "History of Hun People", 'Eastern Literature', 1960, Ch 2. Refugees in the steppes http://gumilevica.kulichki.net/HPH/hph02.htm</ref>. | |||

| According to the ''History of the Gaoche'' of ] (6th century), the origin of the Dingling can be traced to the Chidi (赤狄) (lit. Red Di), who lived in northern China during the ]. The '']'' mentions a total of eight related Di groups, of whom only "Red Di" (赤狄, Chidi), the "White Di" (白狄, Baidi), and "Tall Di" (長狄, Changdi) are known.<ref>Duan (1988), pp. 1-6</ref><ref>Suribadalaha (1986), p. 27.</ref><ref>Theobald, Ulrich (2012). in ChinaKnowledge.de - An Encyclopaedia on Chinese History, Literature and Art</ref> | |||

| According to the Chinese descriptions of the Dinlins, "the inhabitants are generally tall, with red hair, with rosy cheeks and blue eyes. Black hair was considered a bad sign, and people with brown eyes were reputed as Chinese descendants". This description correlates with the results of excavations, in the ] Epoch (2nd century BC - 4th century AD) was practiced cremation, but the remains were covered with a funeral portrait mask. The faces are of three types: | |||

| To the north of the ] empire and Dingling territories, at the headwaters of the ] around ], lived the ''Gekun'' (鬲昆), also known as the ] in later records. Further to the west near the ] river lived the Hujie (呼揭). Other tribes living of the Xiongnu, such as the Hunyu (浑庾), Qushe (屈射), and ] (薪犁), were only mentioned once in Chinese records, and their exact location is unknown.<ref>Lu (1996), p. 136.</ref><ref>Shen (1998), p. 75.</ref> | |||

| 1. Large face, with week cheek bones, thick lips, straight eyes, prognathic chin and thin long aquiline noses. | |||

| During the 2nd century BCE, the Dingling became subjects of ] along with 26 other tribes, including the ] and ].<ref>Li (2003), p. 73.</ref> | |||

| 2. Large face, wider, thick lips, straight eyes, straight noses. | |||

| ===Dingling and Xiongnu=== | |||

| 3. Thinner face, elongated, with week cheek bones, thin lips, straight eyes, moderate chins and tiny slightly upward noses. The faces of the last group approach the masks found in the ] kurgans and ] underground tombs such as ]. The masks were anthropologically investigated by anthropologist G.F.Debets, who characterized the Tashtyk masks as mixed Europoid and Mongoloid, most of all reminding modern ] and ]<ref>L.N.Gumilev, "History of Hun People", 'Eastern Literature', 1960, Ch. 11 Brother Against Brother http://gumilevica.kulichki.net/HPH/hph11.htm</ref>. The expensive artistic masks belonged to rich people. In contrast with the ] tombs with Mongoloids adorned with chestnut toupee beards, the Dinlin elders were imitating Huns in clothing, manners, and tastes, reflected in their art. The masks are also ornamented with very graceful pattern, like tattooed faces in Hunnish tradition, exhibiting the Hun influence on Dinlins<ref>L.N.Gumilev, "History of Hun People", 'Eastern Literature', 1960, Ch. 11 Brother Against Brother http://gumilevica.kulichki.net/HPH/hph11.htm</ref>. | |||

| The Dingling were first subjugated by the ], but the latter gradually weakened. In 71 BCE, after numerous conflicts between the Chinese and the Xiongnu, the Dingling, led by Zhai Jin, with help from neighboring tribes, took the opportunity to revolt. From 63 to 60 BCE, during a split within the Xiongnu ruling clan of Luanti (挛鞮), the Dingling attacked the Xiongnu, together with the ] from the west, supported by the Chinese from the south and the ] from the southeast.<ref>Duan (1988) pp. 99-100.</ref> | |||

| Paleoantropology finds a complex mix of population: | |||

| 1. The basic type of the Dinlin-descendent population was dolichocranial, Europoid, philogenetically connected with Proto-European type. | |||

| In 51 BCE, the Dingling, together with the Hujie and Gekun, were defeated by the Xiongnu under ], on his way to ]. Over the next century there may have been more uprisings, but the only recorded one was in the year 85, when together with the ] they made their final attack on the Xiongnu, and Dingling regained its power under Zhai Ying.<ref>Duan (1988) pp. 101-103.</ref> After that, under the Dingling pressure, the remaining of northern Xiongnu and the ] formed the confederacy by Xianbei chief ] (檀石槐). After his death in 181, the Xianbei moved south and the Dingling took their place on the steppe. | |||

| 2. The mostly dolichocranial type is admixed with brachicranial Europoid type of Di ~ Ainu. | |||

| Some groups of Dingling, called the West Dingling by the ancient Chinese, started to migrate into western Asia, but settled in ] (康居), modern day ] and ]. There is no specific source to tell where exactly they settled, but some claim ] (宰桑 or 斋桑). | |||

| 3. The substrate dolichocranial type has a small admixture of Mongoloid brachicranial type belonging to the Siberian branch of the Asian phylogeny. Possibly, the Mongoloid admixture is a trace of Far Eastern type of the ] penetration into the Minusinsk territory<ref>L.N.Gumilev, "History of Hun People", 'Eastern Literature', 1960, Ch 6 Reign Over Peoples http://gumilevica.kulichki.net/HPH/hph06.htm</ref>. | |||

| ===Assimilation=== | |||

| The Dinlin's forms of life established after the Hunnish conquest included intensive cultural exchange, and as a result developed a new ] with sharply increased density of the Asian component<ref>L.N.Gumilev, "History of Hun People", 'Eastern Literature', 1960, Ch 6 Reign Over Peoples http://gumilevica.kulichki.net/HPH/hph06.htm</ref>. | |||

| Between the short-lived ] in 181 and the foundation of the ] Qaghanate in 402, there was a long period without a tribal confederacy on the steppe. During this period, a part of the Dingling were assimilated to the ] by permanently settling further to the south.<ref>Duan (1988) pp. 111-113.</ref> Another group, documented as about 450,000, moved southeast and merged into the Xianbei. | |||

| Some groups of Dingling settled in China during ]'s reign. According to the '']'', another group of Dingling escaped to the western steppe in Kazakhstan, which has been called the West Dingling.<ref></ref> Around the 3rd century, Dinglings living in China began to adopt family names such as Zhai or Di (翟), Xianyu (鲜于), Luo (洛) and Yan (严).<ref>Duan (1988), pp. 137-142, 152-158.</ref> These Dingling became part of the southern Xiongnu tribes known as ''']''' (赤勒) during the 3rd century, from which the name Chile (敕勒) originated. | |||

| ==Geography== | |||

| During the ] period, the West Dingling Khan Zhai Bin (翟斌) lead his hordes, migrate from Kazakhstan into Central China, served under the ], after series of plotting, Zhai Bin was betrayed by Former Qin, to avoid Qin nobles further attempts, he revolted against the Former Qin Dynasty. Murong Chui (慕容垂), the Xianbei leader under Former Qin court, got appointed as the high command of Former Qin army, was expected to take down the revolt, but convinced by Zhai Bin, joined his mutiny to against Former Qin. Their mutiny were also joined by several other Xianbei tribes which formed the Anti-Qin leagues, with the suggestion by Zhai Bin, Murong Chui was elected to be the leader of the leagues. Near end of the same year, Murong Chui styled himself King of Yan (燕王), left Zhai Bin the new leader of the league and a dilemma of the war, later Murong Chui broke the alliance with the leagues, murdered Zhai Bin and his three sons in an ambush. His nephew Zhai Zhen (翟真) inherited the horde, was elected be the new Leader of the leagues, seeking for revenge, but later assassinated by his military advisor Xianyu Qi (鲜于乞), Xian did not escape far, were caught by the Dingling soldiers and got executed, the leagues elected Zhai Zhen's cousin Zhai Cheng (翟成) as the new Leader, but later also been assassinated by Yan spy, then ] (翟辽), became the new leader of Dingling horde, with the support from the Leagues, he founded the ], a DingLing Dynasty in China in modern Henan Province.<ref>Duan (1988), pp. 148-152.</ref> | |||

| Dinlins lived north of the Huns, the ancient borders of the Huns coincided with the modern borders of the Chinese Inner Mongolia. Dinlins occupied both slopes of the Sayan ridge, from ] to ] rivers. ], a mixture of Dinlins with a unknown tribe ] (Chinese "Tsigu") lived along Yenisei, and to the west of them, on the northern slope of Altai, lived ] (in Chinese "Küeshe"), in appearance similar with Dinlins and, probably, related with them<ref>L.N.Gumilev, "History of Hun People", 'Eastern Literature', 1960, Ch 2. Refugees in the steppes http://gumilevica.kulichki.net/HPH/hph02.htm</ref>. ] traced ] to a ] branch of the ] tribe<ref>Gumilev L.N. "AncientTurks" Ch. 20. Transformation of People http://gumilevica.kulichki.net/OT/ot20.htm</ref>. Chinese annals tell that Kipchaks lived in ], in a "Djilan" (snake) valley<ref>Gumilev L.N. "AncientTurks" Ch. 20. Transformation of People http://gumilevica.kulichki.net/OT/ot20.htm</ref>. This explains the Mongolian name of ]-] people, the ], a "snake" in Mongolian<ref>Pletneva S.A., "Kipchaks", p. 29</ref> | |||

| ] (in Chinese - "Küeshe") lived to the west from the Huns, in appearance Kipchaks were like Dinlins and, probably, related with them. Hun Shanuy and nobility collected tribute from the subordinated tribes, probably receiving furs from the northern border Kipchaks, Dinlins and ]<ref>L.N.Gumilev, "History of Hun People", 'Eastern Literature', 1960, Ch 2. Refugees in the steppes http://gumilevica.kulichki.net/HPH/hph02.htm</ref>. | |||

| About one-quarter of the Tuoba clans show similar names as found among the later Gaoche and Tiele tribes. Among them, the ] (紇骨) and Yizhan (乙旃) clans kept their high status. | |||

| ==Social Organization and Economy== | |||

| Dinlins lives by primitive agriculture, settled cattle breeding and hunting, they dressed in Chinese woolen and silk fabrics. Gold became common, Dinlins started mining iron, but the bronze still was in use. Among Dinlins greatly increased social stratification, tombs can be divided into rich and poor, the rich were accompanied by slaves into their graves, a custom borrowed from the Huns. From the 1st c. BC between Dinlins began to prevail the influence of the eastern Huns, and the elements of the western culture were remaining as relicts<ref>L.N.Gumilev, "History of Hun People", 'Eastern Literature', 1960, Ch. 11 Brother Against Brother http://gumilevica.kulichki.net/HPH/hph11.htm</ref>. | |||

| Between the 4th and 7th centuries, the name "Dingling" slowly disappeared from Chinese records, coinciding with the rise of the ].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Rhyne |first1=George N. |last2=Adams |first2=Bruce Friend |title=The Supplement to The Modern Encyclopedia of Russian, Soviet and Eurasian History: Deni, Viktor Nikolaevich - Dzhungaria |date=2007 |publisher=Academic International Press |isbn=978-0-87569-142-8 |page=44 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=SUxpAAAAMAAJ |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| ==Religious Beliefs== | |||

| Huns borrowed their magnificent cult of personified cosmos from their western neighbors, later ] or ] (Üechji), or Dinlins, because E.Asian Mongoloids had no such cult, but were polyspiritualists. Huns also believed in spirits and existence beyond the grave, and the naive nomadic consciousness envisioned it as a continuation of life. The belief in afterlife led to magnificent funerals in double coffins, dressing the deceased in brocade and precious furs to protect the deceased from the cold, with a few hundred sacrificed friends and concubines to serve the deceased in the next world. The tradition of accompanying Shanuy or a noble into the afterlife coexisted with human sacrifice to pra-fathers of brave captives, and the spirits demanded sacrifices through the priests, a tradition of human sacrifices was connected with the Siberian component of the Hun religion, with very ancient Chinese shamanism and, probably, with the Tibetan Bon religion<ref>L.N.Gumilev, "History of Hun People", 'Eastern Literature', 1960, Ch 6 Reign Over Peoples http://gumilevica.kulichki.net/HPH/hph06.htm</ref>. | |||

| ==Cultural and linguistic theories== | |||

| The Chinese defeats of the Huns in the end of the 1st c. AD, and subsequent disintigration of the Hunnish rule lead to the changes of funeral ceremony: the ancient burial was replaced with cremation, marking a change of religious tradition, the ancient Türks (Türküts) inherited the new religion and it survived until the 9th century AD. Chinese had influenced Dinlins, Dinlin ] had Chinese ware just like the large Hun's ] in ]. Dinlins were Sinicized along with their masters, the Huns. But the ancient Dinlin customs continued to exist along with the cultural change, like a custom of tattooing the arms of the braves. This custom was archeologically confirmed during excavation of the second ] kurgan. The Dinlin culture of the ] Epoch was a hybrid and survived to the 2nd century AD<ref>L.N.Gumilev, "History of Hun People", 'Eastern Literature', 1960, Ch. 11 Brother Against Brother http://gumilevica.kulichki.net/HPH/hph11.htm</ref>. | |||

| {{Infobox language | |||

| | name = Dingling | |||

| | familycolor = unclassified | |||

| | family = ]<br>]?<br>]?<br>]? | |||

| | glotto = none | |||

| | iso3 = none | |||

| | region = northern ] | |||

| | ethnicity = DIngling | |||

| | extinct = after 7th century | |||

| }} | |||

| Several theories have been proposed about the relationship between the Dingling and both ancient and living cultures, based on linguistic, historical and archaeological evidence. | |||

| ===Turkic hypothesis=== | |||

| The Dingling are considered to have been an early ].<ref> | |||

| ]: . Cambridge University Press, 2013. pp.175-176.</ref><ref> | |||

| Peter B. Golden: in ''Contact and Exchange in the Ancient World''. Ed. Victor H. Mair. University of Hawaii Press, 2006. p.140</ref> | |||

| '']'' records the Dingling word for the ] (vulpes lagopus) as 昆子 ''kūnzǐ'' (] (ZS): *''kuən-t͡sɨ<sup>X</sup>'' < Early Middle Chinese: *''kwən-tsɨ’/tsi’'' < ]: *''kûn-tsəʔ''), which is proposed to be from ] *''qïrsaq'' ~ *''karsak''.<ref> The Peoples of the West from the Weilue 魏略 by Yu Huan 魚豢 A Third Century Chinese Account Composed between 239 and 265 CE Quoted in zhuan 30 of the Sanguozhi Published in 429 CE Draft English translation by John E. Hill (September, 2004)</ref><ref>Pulleyblank, E. G. (1962) pdf, Asia Major 9; p. 226 of 206‒65.</ref><ref>Schuessler (2014), p. 258, 273</ref><ref>Starostin, Sergei; Dybo, Anna; Mudrak, Oleg (2003), , in ''Etymological dictionary of the Altaic languages'' (Handbuch der Orientalistik; VIII.8), Leiden, New York, Köln: E.J. Brill</ref> | |||

| ==Initial Political Relationships== | |||

| ===Tungusic hypothesis=== | |||

| By the 214 BC Huns already had Shanuy, but were subjects of ] ], maybe because of failures in struggle with ] or Sayan Dinlins<ref>L.N.Gumilev, "History of Hun People", 'Eastern Literature', 1960, Ch 4, Great Wall http://gumilevica.kulichki.net/HPH/hph04.htm</ref>. | |||

| Chinese historians linked the Tungusic speakers among the later ] to the Dingling, considering them as descendants of the Dingling owing to linguistic similarities.<ref name="XTS219"/><ref name = "Xu176"/>{{efn|Shiwei were stated in most Chinese sources (e.g. ] 100, ] 84, ] 199) to be relatives to para-Mongolic-speaking ]; the Shiwei sub-tribe Mengwu (蒙兀) / Mengwa (蒙瓦) were considered ancestral to the ].<ref>Xu (2005), p. 86; quote: "The ancestors of the Mongols are believed to be the Mengwu Shiwei (Mengwa Shiwei) who appeared in history as late as in the Tang Dynasty (618-907)."; p. 184</ref>}} | |||

| In 203-202 BC ]'s Khan ] subordinated the Huns-related tribe ], the Dinlin's tribe ] - ] north from Altai, and their eastern neighbors Dinlins on the northern slopes of the Sayan mountains from upper Yenisei to ], and ] - ] in the W. Mongolia territory near lake Kyrgyznor <ref>L.N.Gumilev, "History of Hun People", 'Eastern Literature', 1960, Ch. 5 Whistling Arrows http://gumilevica.kulichki.net/HPH/hph05.htm</ref>. | |||

| ===Dené-Yeniseian hypothesis=== | |||

| When ] subordinated these tribes they belonged to the ] in its last third stage, already passed ] and started to use iron. Their economy was agriculture and settled cattle breeding. Their ] contain plenty of weapons, showing that they were aggressive people. The complexity of their burials show their patriarchal social organization, just like their Hun neighbors, but without traces of a statehood. Their art was stylistically unified with the art of ] and ], indicating their belonging to the western cultural complex, but they are anything but the carriers of peripheral provincial culture. "Powerful Minusinsk cultural center influenced wide taiga-steppe areas of ] and, apparently, even the ] in the ]"<ref>" Debets G.F., "Paleoantropology of the USSR", p. 124, in L.N.Gumilev, "History of Hun People", 'Eastern Literature', 1960, Ch 6 Reign Over Peoples http://gumilevica.kulichki.net/HPH/hph06.htm</ref>. | |||

| In ''Zur jenissejisch-indianischen Urverwandtschaft (Concerning Yeniseian-] Primal Relationship)'', the German scholar Heinrich Werner developed a new language family which he termed ''Baikal–Siberic''. By extension, he groups together the ] peoples (], ], ], ], ], and ]), the ] Indigenous peoples of the Americas, and the Dingling of Chinese chronicles to ''Proto-Dingling''.<ref>Werner, Heinrich ''Zur jenissejisch-indianischen Urverwandtschaft''. Harrassowitz Verlag. 2004 </ref> The linguistic comparison of Na-Dene and Yeniseian shows that the quantity and character of the correspondences points to a possible common origin. According to Russian linguistic experts, they likely spoke a ] or ] with an ] form of ], exhibiting a linguistically and culturally unified community. | |||

| During the 90es BC attack by Chinese ruler U-Di against Hulugu-Shanuy Huns, the Shanuy summoned vassal tribes, and among his allies were Yenisei Dinlins, red-bearded giants in wooden cuirasses with infinitely sharp weapons, under command of a Chinese defector Vey Lüy. The small size of the main army of only 50 thousand Huns and Dinlins was compensated by high fighting spirit of the nomads<ref>L.N.Gumilev, "History of Hun People", 'Eastern Literature', 1960, Ch. 9 Mortal Fight http://gumilevica.kulichki.net/HPH/hph09.htm</ref>. | |||

| The name Dingling resembles both: | |||

| In the summer of 71 BC Dinlins revolted, and together with Usuns from the west, and Ühuans from the east, devastated Huns<ref>L.N.Gumilev, "History of Hun People", 'Eastern Literature', 1960, Ch. 10 Hun State Crisis http://gumilevica.kulichki.net/HPH/hph10.htm</ref>. But in 57 BC Huns again subdued Dinlins and Hagases (Khakasses, called ancient Chinese name - Gyanguns)<ref>L.N.Gumilev, "History of Hun People", 'Eastern Literature', 1960, Ch. 11 Brother Against Brother http://gumilevica.kulichki.net/HPH/hph11.htm</ref>. | |||

| * the Yeniseian word *dzheng ''people'' > {{transliteration|mis|italic=no|Ket de?ng, Yug dyeng, Kott cheang}} | |||

| * the Na-Dene word *ling or {{transliteration|mis|italic=no|*hling}} ''people'', i.e. as manifested in the name of the ] (properly {{transliteration|mis|italic=no|hling-git}} ''son of man, child of the people''). | |||

| Although the ] language family is now a widely known proposal, his inclusion of the Dingling is not widely accepted. | |||

| ==Ethnical Affiliations== | |||

| == Physical appearance == | |||

| Probably, Dinlins descended from the southern Di, and Yenisei Kyrgyzes were the Europoid natives of Siberia,<ref>L.N.Gumilev, "History of Hun People", 'Eastern Literature', 1960, Ch. 2 Refugees in the Steppes http://gumilevica.kulichki.net/HPH/hph02.htm</ref>. | |||

| There is some evidence that the Dingling looked similar to European people, based on their identification with the ] of the Altai region in Siberia. In the 20th century, several historians proposed that the Tagar people were characterized by a high frequency of light hair and light eyes, and that the associated Dingling were blond-haired.<ref>{{cite book |title=Russian Translation Series of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University |date=1964 |publisher=Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University |page=10 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=f5ZAAQAAIAAJ&q=dinlin+tagar |language=en}} "It is quite probable that the inhabitants of the Upper Yenissei during the epoch of the Tagar culture were characterized by light pigmentation (light hair and light eyes). This point of view was also held by Debets in one of his earlier published works concerning the so - called "blond Dinlin race," which at the time Debets wrote gave rise to an extensive literature."</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Alekseev |first1=Valerij P. |last2=Gochman |first2=Il'ja I. |title=Asien II: Sowjet-Asien |date=3 December 2018 |publisher=Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG |isbn=978-3-486-82294-6 |page=39 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=VbN6DwAAQBAJ&pg=PA39 |language=en}} "For instance, the tribes which came from the upper Yenisei are called "dinlin" and they are described as fair pigmented in comparison with the Chinese (Bičurin, 1950-1953; Grumm Grzimajlo 1899, 1926)."</ref> Genetic testing of fossils from the Tagar culture has confirmed the theory that they were often blue eyed and light-haired.<ref name="Genetics">{{cite journal |last1=Keyser |first1=Christine |last2=Bouakaze |first2=Caroline |last3=Crubézy |first3=Eric |last4=Nikolaev |first4=Valery G. |last5=Montagnon |first5=Daniel |last6=Reis |first6=Tatiana |last7=Ludes |first7=Bertrand |date=May 16, 2009 |title=Ancient DNA provides new insights into the history of south Siberian Kurgan people |journal=] |volume= 126|issue= 3|pages= 395–410|doi= 10.1007/s00439-009-0683-0|pmid=19449030 |s2cid=21347353 }}</ref> Twenty-first century scholars continue to describe the Dingling in a similar manner. Adrienne Mayor repeated N. Ishjants' description (1994) of the Dingling as "red-haired, blue-eyed giants" while M.V. Dorina called the Dingling "European-looking."<ref>{{cite book |last1=Mayor |first1=Adrienne |title=The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World |date=9 February 2016 |publisher=Princeton University Press |isbn=978-0-691-17027-5 |page=421 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=mW6YDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA421 |language=en}} "...the Dingling (described as “red-haired, blue-eyed giants,” perhaps related to the Altai, Tuva, Pazyryk, Kyrgyz cultures);"</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Dorina |first1=M.V. |chapter=Fine arts and music: The cultural links of Southern Siberia and India |title=Eurasia and India: Regional Perspectives |date=27 September 2017 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-351-69195-6 |page=106 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=OHE3DwAAQBAJ&pg=PT106 |language=en}} "It was the time of intensive interracial marriages of European-looking men (dinlin) and the Turkic language–speaking Mongols (guangun-kyrgyz),"</ref> | |||

| The Chinese sources do not differentiate the Dingling's appearance from the Han Chinese. Chinese histories unanimously depict the Dingling as the ancestors of the Tiele, whose physical appearance is also not described, but seem to have included non-Turkic speaking peoples. The ], an Iranic people, are included among them, as well as the Bayegu, who had a somewhat different language than the Tiele according to the '']''. The ''New Book'' also relates that the Kyrgyz intermixed with the Dingling. The '']'' states that the Tiele had similar customs to the ] but different marriage and burial traditions.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Lee |first1=Joo-Yup |last2=Kuang |first2=Shuntu |title=A Comparative Analysis of Chinese Historical Sources and y-dna Studies with Regard to the Early and Medieval Turkic Peoples |journal=Inner Asia |date=18 October 2017 |volume=19 |issue=2 |pages=197–239 |doi=10.1163/22105018-12340089 |s2cid=165623743 |issn=1464-8172|doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| ] were a branch of Dinlins, and Kipchaks were a branch of Boma, genetically possibly ], i.e. [[Kets. In antiquity Kipchaks lived in Altai, in a valley Chinese called Chjelyan, undoubtedly a transcription of word "Djilan" = snake (from there the Snake mountain and the city with Russified name Zmyoinogorsk, i.e. "Snake Mountain")<ref>\\GumilevAncientTurks\ot20.htm Ch. 20. Transformation of People</ref>. | |||

| The ] described the Dingling as human beings with horses' legs and hooves and excellent at running.<ref name = "strassberg">''A Chinese bestiary: strange creatures from the guideways through mountains and seas''. Translated by Richard E. Strassberg. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. (2002). p. 226.</ref> However, this description is mythological in nature.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Mairs |first1=Rachel |title=The Graeco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek World |date=29 November 2020 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-351-61028-5 |page=460 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NBYHEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA460 |language=en}}</ref> A similar description is also echoed in a ] account, recorded in the '']'' (compiled 239-265 CE), which describes the men of Majing ("Horse Shanks"), located north of the Dingling, as possessing horse legs and hooves.<ref>{{cite web |title=Weilue: The Peoples of the West |url=https://depts.washington.edu/silkroad/texts/weilue/weilue.html |website=depts.washington.edu}} "...north of the Dingling (丁令) is the kingdom of Majing (馬脛 ‘Horses Shanks’). These men make sounds like startled wild geese. From above the knee, they have the body and hands of a man, but below the knees, they grow hair, and have horses’ legs and hooves. They don't ride horses as they can run faster than horses. They are brave, strong, and daring fighters".</ref> | |||

| Boma can't be identified neither with Dili (Tele), nor with Dinlins. Boma, or more correct, Alakchins and Bikins are racially similar but ethnically distinct from Dinlins Probably they were spread very wide, from Altai to Baikal, in dispersed groups, as many other Siberian tribes<ref>L.N.Gumilev, "History of Hun People", 'Eastern Literature', 1960, Ch 2. Refugees in the steppes http://gumilevica.kulichki.net/HPH/hph02.htm</ref>. | |||

| == See also == | |||

| Kipchaks were among Türküt subject peoples, after the 630 defeat with the other defeated tribes a part of them settled in Alashan near their former Türküt masters. The other part intermixed with Kangals and formed people known under a name ]<ref>\\GumilevAncientRusAndGreatSteppe\args000.htm Introduction</ref>. Under the leadership of Ashina khans they joined a second component in the restored horde, the ], descendants of Seyanto, a fact documented in the Tonyukuk inscription, where the tribal union is called "Türksir budun", i.e. Türkic-Sir people<ref>\\GumilevAncientTurks\ot20.htm Ch. 20. Transformation of People</ref>. | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| == Notes == | |||

| Kipchaks were among peoples subject to Türkic Kaganate, after defeat in 630 AD a part of Kipchaks coached in ], mixed with ], and formed people known as ]. The second component in the restored ] of ] khans were ], descendants of ], expressed in the ] as "Türksir budun", i.e. Türkic-Sir people<ref>\\GumilevAncientTurks\ot20.htm Ch. 20. Transformation of People</ref>. | |||

| {{notelist}} | |||

| == |

== References == | ||

| {{reflist|2}} | |||

| == Further reading == | |||

| In 48 BC Huns again had to subdue both Dinlins and ] (]), restoring the Hun sovereignty in the Western Mongolia and Minusinsk depression, but right after that Dinlins and Hagases (Khakasses) regained their freedom. Eventually these two peoples merged to produce Yenisei Kyrgyz people<ref>L.N.Gumilev, "History of Hun People", 'Eastern Literature', 1960, Ch. 11 Brother Against Brother http://gumilevica.kulichki.net/HPH/hph11.htm</ref>. | |||

| * Duan, Lianqin (1988). ''Dingling, Gaoju and Tiele''. Shanghai: Shanghai People's Press, 1988. | |||

| In the middle of the 1st c. AD the Hun empire split into the ] and ]. Dinlins remained in the ] state. The relations between Huns and Dinlins grew aggravated, and ] concluded a union with Chinese. In the 86 AD Dinlins revolted, and in the 90 AD switched to the side of the Chinese-Syanbi coalition. Not able to battle their numerous Chinese, Syanbi, and Dinlin enemies, Huns abandoned their native land, but saved their freedom. In the Baraba and Karaganda steppes the Huns recovered from defeat, and 15 years later restarted the war for Asia. For a time, Dinlins controlled the Hin's steppes<ref>L.N.Gumilev, "History of Hun People", 'Eastern Literature', 1960, http://gumilevica.kulichki.net/HPH/hph14.htm Ch. 14 Broken Ring</ref>. | |||

| *Hill, John E. (2004). ''"The Peoples of the West" from the Weilüe'', Section 15. (Draft version). Downloadable from: . | |||

| From 155 to 166 AD reorganized ] stopped ] in the north and pushed them into ] mountains, struck ] in the west, drove ] from ] to ], taking over the lands of the Hun state for 6,5 thousand km from ] to ] and ]. After that, Dinlins faded from the records, and the Huns started a new period in their history. The strongest reached Europe, where surrounded with new Ugrian and Caucasian allies they finished with dominance of Alans, Goths and reached Rome. The "Weak Huns" ] remained in ] and established a princedom that existed up to the 5th century AD. Severe defeats from the Huns created them reputation of bandits and robbers among many western European peoples, while the Chinese authors characterized them as most cultural people of all "barbarians"<ref>L.N.Gumilev, "History of Hun People", 'Eastern Literature', 1960, Ch 15. Last Strike http://gumilevica.kulichki.net/HPH/hph15.htm</ref> | |||

| * Li, Jihe (2003). ''A Research on Migration of Northwestern Minorities Between pre-Qin to Sui and Tang''. Beijing: Nationalities Press. | |||

| By the 10th c., Kumans, the descendants of the Dinlin western Kypchak branch, had a very small population spread in the fertile Siberian lands. Direct descendants of Dinlins, Yenisei Kyrgyzes, continued to live in the fertile Minusinsk depression, engaged in irrigation agriculture and settled cattle breeding. They preserved rich cultural heritage of the ancestors, but abandoned the former bellicosity that in the 9th century drove them for a conquest of the Great steppe. Now to the south of them settled a numerous Mongolian Oirat tribe<ref>\\GumilevAncientRusAndGreatSteppe\args205.htm Ch.5, Dukes of Exile</ref> | |||

| * ] (1996). ''A History of Ethnic Groups in China''. Beijing: Oriental Press. | |||

| On the banks of the Nile delta accumulated a colony of descendents of the ancient Dinlin valour, Mamluk Kipchaks (Mamluks-bahrits), who ruled Egypt until 1382, when they were replaced by Caucasian Mamluks-burdjits<ref>\\GumilevAncientRusAndGreatSteppe\args420.htm Ch.20, Yasa and Straggle Against It </ref>. | |||

| * Shen, Youliang (1998). ''A Research on Northern Ethnic Groups and Regimes''. Beijing: Central Nationalities University Press. | |||

| * Suribadalaha (1986). ''New Studies of the Origins of the Mongols''. Beijing: Nationalities Press. | |||

| ==Rulers of Gaoche== | |||

| * Trever, Camilla (1932). ''Excavations in Northern Mongolia (1924-1925)''. Leningrad: J. Fedorov Printing House. | |||

| * Xue, Zongzheng (1992). ''A History of Turks''. Beijing: Chinese Social Sciences Press. | |||

| {| class="wikitable" | |||

| ! ] and ] !! Durations of reigns | |||

| |- | |||

| | colspan="2" style="text-align: center" | ''Family name and given name'' | |||

| |- | |||

| | Afuzhiluo|副伏羅阿伏至羅 Fùfúluó Āfúzhìluó || ]-? | |||

| |- | |||

| | Baliyan|跋利延 Bálìyán || ? | |||

| |- | |||

| | Mi'etu|彌俄突 Mí'étú || ? | |||

| |- | |||

| | Yifu|伊匐 Yīfú || ? | |||

| |- | |||

| | Yueju|越居 Yuèjū || ] | |||

| |- | |||

| | Bizao|比造 Bǐzào || ] | |||

| |- | |||

| | Qubin|去賓 Qùbīn || ]-] | |||

| |} | |||

| ==Notes and references== | |||

| <div class="references-small"><references/></div> | |||

| *, from the Weilue, by Yu Huan | |||

| * Suribadalaha. '''', Beijing: Minzu Chubanshe, 1986. | |||

| * Gumilev, L.N. "The Huns. Central Asia in Ancient Times", (Russian: ''Khunnu''), 1960 | |||

| == See also == | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| {{Historical Non-Chinese peoples in China}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 02:24, 3 December 2024

Ancient Siberian culture For the writer, see Ding Ling. For the tomb, see Dingling (Ming).| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Dingling" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (May 2010) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

GREEKSSAKASSargatShuleSABEANSMEROËAKSUMKUCHATesinskyWUSUNKhotanLOULANOrdos

cultureJINDONGHUYUEZHIKANGJUDinglingsSarmatiansSELEU-

CIDSPTOLE-

MIESPARTHIAN

EMPIRESUNGASSATAVA-

HANASHAN

DYNASTYXIONGNUclass=notpageimage| The Dingling and contemporary Asian polities circa 100 BCE.

The Dingling were an ancient people who appear in Chinese historiography in the context of the 1st century BCE.

The Dingling are considered to have been an early Turkic-speaking people. They were also proposed to be the ancestors of Tungusic speakers among the later Shiwei people, or are related to Na-Dené and Yeniseian speakers.

Modern archaeologists have identified the Dingling as belonging to the eastern Scythian horizon, namely the Tagar culture.

Etymology

The ethnonym 'Dingling' is regarded by modern scholars in the Western world as being interchangeable with the ethnonym 'Tiele', who are believed to be the descendants of the Dingling. Chinese historiographers believed that 'Tiele' was a mistaken transcription, related them to the ancient Red Di (狄翟), and recorded various names like Dili (狄历), Gaoche (高車) or Chile (敕勒).

Several modern scholars, including Peter B. Golden, now believe that all of these ethnonyms described by the Chinese all derive from Altaic exonyms describing wheeled vehicles, with 'Dingling' perhaps being an earlier rendering of a Tuoba word (*tegreg), meaning "wagon".

Peter Golden also wrote that "Gaoche" or "high carts" may be a translation of "Dingling et al.". Edwin Pulleyblank writes that "High Cart" is just one of several variations of exonyms that ultimately reflect the original Turkic meaning of 'Dingling', which is possibly derived from *Tägräg, meaning "circle, hoop".

Origin and migration

The Weilüe mentioned three Dingling groups:

- one group south of Majing (馬脛, literally: "Horse-Shank"), north of Kangju, and west of Wusun;

- another south of the North Sea, identified as Lake Baikal;

- and another north of Xiongnu and neighbouring the Qushi (屈射), Hunyun (渾窳), Gekun (隔昆), and Xinli (薪犁), all of whom had once been conquered by the Xiongnu.

Murphy (2003) proposes that the Dingling's country had been in the Minusinsk Basin on the Yenisey river, thus close to the location of the Dingling group who neighbored the Kangju, Wusun, and Majing people. Dingling gradually moved southward to Mongolia and northern China. They were a huge independent horde for centuries, but were later defeated and temporarily became subject of the Xiongnu Empire, and thus presumably related to the invaders known as Huns in the west. One group, known as the West Dingling, remained in an area that would become Kazakhstan, while others – expelled from Mongolia by the Rouran – settled in the Tarim Basin during the 5th century and took control of Turpan.

The Dingling had a warlike society, formed by traders, hunters, fishers, and gatherers, living a semi-nomadic life in the southern Siberian mountain taiga region from Lake Baikal to northern Mongolia. Some ancient sources claims that Di or Zhai (翟) was adopted as the group name because the Zhai family had been the ruling house for centuries.

Other sources claim that they might have been correlated with the Guifang, a northern tribe that appears in the oracle bone inscriptions from Yinxu.

According to the History of the Gaoche of Wei Shou (6th century), the origin of the Dingling can be traced to the Chidi (赤狄) (lit. Red Di), who lived in northern China during the Spring and Autumn period. The Mozi mentions a total of eight related Di groups, of whom only "Red Di" (赤狄, Chidi), the "White Di" (白狄, Baidi), and "Tall Di" (長狄, Changdi) are known.

To the north of the Xiongnu empire and Dingling territories, at the headwaters of the Yenisei around Tannu Uriankhai, lived the Gekun (鬲昆), also known as the Yenisei Kyrgyz in later records. Further to the west near the Irtysh river lived the Hujie (呼揭). Other tribes living of the Xiongnu, such as the Hunyu (浑庾), Qushe (屈射), and Xinli (薪犁), were only mentioned once in Chinese records, and their exact location is unknown.

During the 2nd century BCE, the Dingling became subjects of Modu Chanyu along with 26 other tribes, including the Yuezhi and Wusun.

Dingling and Xiongnu

The Dingling were first subjugated by the Xiongnu, but the latter gradually weakened. In 71 BCE, after numerous conflicts between the Chinese and the Xiongnu, the Dingling, led by Zhai Jin, with help from neighboring tribes, took the opportunity to revolt. From 63 to 60 BCE, during a split within the Xiongnu ruling clan of Luanti (挛鞮), the Dingling attacked the Xiongnu, together with the Wusun from the west, supported by the Chinese from the south and the Wuhuan from the southeast.

In 51 BCE, the Dingling, together with the Hujie and Gekun, were defeated by the Xiongnu under Zhizhi Chanyu, on his way to Kangju. Over the next century there may have been more uprisings, but the only recorded one was in the year 85, when together with the Xianbei they made their final attack on the Xiongnu, and Dingling regained its power under Zhai Ying. After that, under the Dingling pressure, the remaining of northern Xiongnu and the Tuoba formed the confederacy by Xianbei chief Tanshihuai (檀石槐). After his death in 181, the Xianbei moved south and the Dingling took their place on the steppe.

Some groups of Dingling, called the West Dingling by the ancient Chinese, started to migrate into western Asia, but settled in Kangju (康居), modern day Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. There is no specific source to tell where exactly they settled, but some claim Lake Zaysan (宰桑 or 斋桑).

Assimilation

Between the short-lived Xianbei confederacy in 181 and the foundation of the Rouran Qaghanate in 402, there was a long period without a tribal confederacy on the steppe. During this period, a part of the Dingling were assimilated to the northern Xiongnu by permanently settling further to the south. Another group, documented as about 450,000, moved southeast and merged into the Xianbei.

Some groups of Dingling settled in China during Wang Mang's reign. According to the Weilüe, another group of Dingling escaped to the western steppe in Kazakhstan, which has been called the West Dingling. Around the 3rd century, Dinglings living in China began to adopt family names such as Zhai or Di (翟), Xianyu (鲜于), Luo (洛) and Yan (严). These Dingling became part of the southern Xiongnu tribes known as Chile (赤勒) during the 3rd century, from which the name Chile (敕勒) originated.

During the Sixteen Kingdoms period, the West Dingling Khan Zhai Bin (翟斌) lead his hordes, migrate from Kazakhstan into Central China, served under the Former Qin, after series of plotting, Zhai Bin was betrayed by Former Qin, to avoid Qin nobles further attempts, he revolted against the Former Qin Dynasty. Murong Chui (慕容垂), the Xianbei leader under Former Qin court, got appointed as the high command of Former Qin army, was expected to take down the revolt, but convinced by Zhai Bin, joined his mutiny to against Former Qin. Their mutiny were also joined by several other Xianbei tribes which formed the Anti-Qin leagues, with the suggestion by Zhai Bin, Murong Chui was elected to be the leader of the leagues. Near end of the same year, Murong Chui styled himself King of Yan (燕王), left Zhai Bin the new leader of the league and a dilemma of the war, later Murong Chui broke the alliance with the leagues, murdered Zhai Bin and his three sons in an ambush. His nephew Zhai Zhen (翟真) inherited the horde, was elected be the new Leader of the leagues, seeking for revenge, but later assassinated by his military advisor Xianyu Qi (鲜于乞), Xian did not escape far, were caught by the Dingling soldiers and got executed, the leagues elected Zhai Zhen's cousin Zhai Cheng (翟成) as the new Leader, but later also been assassinated by Yan spy, then Zhai Liao (翟辽), became the new leader of Dingling horde, with the support from the Leagues, he founded the Wei state, a DingLing Dynasty in China in modern Henan Province.

About one-quarter of the Tuoba clans show similar names as found among the later Gaoche and Tiele tribes. Among them, the Hegu (紇骨) and Yizhan (乙旃) clans kept their high status.

Between the 4th and 7th centuries, the name "Dingling" slowly disappeared from Chinese records, coinciding with the rise of the Uyghur Khaganate.

Cultural and linguistic theories

| Dingling | |

|---|---|

| Region | northern China |

| Ethnicity | DIngling |

| Extinct | after 7th century |

| Language family | unclassified Turkic? Tungusic? Dene–Yeniseian? |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | None (mis) |

| Glottolog | None |

Several theories have been proposed about the relationship between the Dingling and both ancient and living cultures, based on linguistic, historical and archaeological evidence.

Turkic hypothesis

The Dingling are considered to have been an early Turkic-speaking people.

Weilüe records the Dingling word for the arctic fox (vulpes lagopus) as 昆子 kūnzǐ (Middle Chinese (ZS): *kuən-t͡sɨ < Early Middle Chinese: *kwən-tsɨ’/tsi’ < Eastern Han Chinese: *kûn-tsəʔ), which is proposed to be from Proto-Turkic *qïrsaq ~ *karsak.

Tungusic hypothesis

Chinese historians linked the Tungusic speakers among the later Shiwei people to the Dingling, considering them as descendants of the Dingling owing to linguistic similarities.

Dené-Yeniseian hypothesis

In Zur jenissejisch-indianischen Urverwandtschaft (Concerning Yeniseian-Indian Primal Relationship), the German scholar Heinrich Werner developed a new language family which he termed Baikal–Siberic. By extension, he groups together the Yeniseian peoples (Arin, Assan, Yugh, Ket, Kott, and Pumpokol), the Na-Dene Indigenous peoples of the Americas, and the Dingling of Chinese chronicles to Proto-Dingling. The linguistic comparison of Na-Dene and Yeniseian shows that the quantity and character of the correspondences points to a possible common origin. According to Russian linguistic experts, they likely spoke a polysynthetic or synthetic language with an active form of morphosyntactic alignment, exhibiting a linguistically and culturally unified community.

The name Dingling resembles both:

- the Yeniseian word *dzheng people > Ket de?ng, Yug dyeng, Kott cheang

- the Na-Dene word *ling or *hling people, i.e. as manifested in the name of the Tlingit (properly hling-git son of man, child of the people).

Although the Dené–Yeniseian language family is now a widely known proposal, his inclusion of the Dingling is not widely accepted.

Physical appearance

There is some evidence that the Dingling looked similar to European people, based on their identification with the Tagar culture of the Altai region in Siberia. In the 20th century, several historians proposed that the Tagar people were characterized by a high frequency of light hair and light eyes, and that the associated Dingling were blond-haired. Genetic testing of fossils from the Tagar culture has confirmed the theory that they were often blue eyed and light-haired. Twenty-first century scholars continue to describe the Dingling in a similar manner. Adrienne Mayor repeated N. Ishjants' description (1994) of the Dingling as "red-haired, blue-eyed giants" while M.V. Dorina called the Dingling "European-looking."

The Chinese sources do not differentiate the Dingling's appearance from the Han Chinese. Chinese histories unanimously depict the Dingling as the ancestors of the Tiele, whose physical appearance is also not described, but seem to have included non-Turkic speaking peoples. The Alans, an Iranic people, are included among them, as well as the Bayegu, who had a somewhat different language than the Tiele according to the New Book of Tang. The New Book also relates that the Kyrgyz intermixed with the Dingling. The Book of Sui states that the Tiele had similar customs to the Göktürks but different marriage and burial traditions.

The Classic of Mountains and Seas described the Dingling as human beings with horses' legs and hooves and excellent at running. However, this description is mythological in nature. A similar description is also echoed in a Wusun account, recorded in the Weilüe (compiled 239-265 CE), which describes the men of Majing ("Horse Shanks"), located north of the Dingling, as possessing horse legs and hooves.

See also

Notes

- Chinese: 丁零 (174 BCE); 丁靈 (200 BCE); Eastern Han Chinese: *teŋ-leŋ < Old Chinese: *têŋ-rêŋ

- Shiwei were stated in most Chinese sources (e.g. Weishu 100, Suishu 84, Jiu Tangshu 199) to be relatives to para-Mongolic-speaking Khitans; the Shiwei sub-tribe Mengwu (蒙兀) / Mengwa (蒙瓦) were considered ancestral to the Mongols.

References

- Hyun Jin Kim: The Huns, Rome and the Birth of Europe. Cambridge University Press, 2013. pp.175-176.

- Peter B. Golden: Some Thoughts on the Origins of the Turks and the Shaping of the Turkic Peoples in Contact and Exchange in the Ancient World. Ed. Victor H. Mair. University of Hawaii Press, 2006. p.140

- ^ Xin Tangshu vol. 219 "Shiwei" txt: "室韋, 契丹别種, 東胡之北邊, 蓋丁零苗裔也" translation by Xu (2005:176) "The Shiwei, who were a collateral branch of the Khitan inhabited the northern boundary of the Donghu, were probably the descendants of the Dingling ... Their language was the same as that of the Mohe."

- ^ Xu Elina-Qian, Historical Development of the Pre-Dynastic Khitan, University of Helsinki, 2005. p. 176. quote: "The Mohe were descendants of the Sushen and ancestors of the Jurchen, and identified as Tungus speakers."

- Werner, Heinrich Zur jenissejisch-indianischen Urverwandtschaft. Harrassowitz Verlag. 2004 abstract. p. 25

- Hartley, Charles W.; Yazicioğlu, G. Bike; Smith, Adam T. (19 November 2012). The Archaeology of Power and Politics in Eurasia: Regimes and Revolutions. Cambridge University Press. p. 245. ISBN 978-1-139-78938-7. "The Dinlin are considered to have been part of the Tagar Culture and are mentioned in the written sources as being among the acquired "possessions" of the Huns (Mannai—Ool 1970: 107; Sulimirski 1970: 112)."

- Wang, Penglin (28 March 2018). Linguistic Mysteries of Ethnonyms in Inner Asia. Lexington Books. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-4985-3528-1. "Dingling is alternatively called Tiele. Suishu and Beishi, both of which were written during the seventh century during the Tang period, traced the origin of the Tiele or Dingling back to Xiongnu."

- Hickman, Bill; Leiser, Gary (14 October 2015). Turkish Language, Literature, and History: Travelers' Tales, Sultans, and Scholars Since the Eighth Century. Routledge. p. 149. ISBN 978-1-317-61295-7. "...the Dingling 丁零, Old Chin. (before 200 BCE): *têŋ-rêŋ > Late Han (after 200 BCE to 200 CE): teŋ leŋ,32 a tribal union north of the Xiongnu, viewed as ancestral to the Tiele and possibly an early rendering of that ethnonym."

- Weishu Vol 103 Gaoche "高車,蓋古赤狄之餘種也,初號為狄歷,北方以為勑勒,諸夏以為高車、丁零。" tr. "Gaoche, probably the remnant stock of the ancient Red Di. Initially, they had been called Dili; northerners considered them to be Chile; the various Xia (i.e. Chinese) considered them to be Gaoche Dingling (i.e. Dingling with High Cart)"

- Xin Tangshu vol. 217a "回紇,其先匈奴也,俗多乘高輪車,元魏時亦號高車部,或曰敕勒,訛為鐵勒。" tr: "Uyghurs, their predecessors were the Xiongnu. Because, customarily, they ride high-wheeled carts. In Yuan Wei time, they were also called Gaoche (i.e. High-Cart) tribe. Or called Chile, or mistakenly as Tiele."

- Tasar, Eren; Frank, Allen J.; Eden, Jeff (11 October 2021). From the Khan's Oven: Studies on the History of Central Asian Religions in Honor of Devin DeWeese. BRILL. p. 5. ISBN 978-90-04-47117-7. "The latter were part of the Tiĕlè union, earlier termed the Gāochē "High Carts" (Liu, 1985, I:127--128; Pulleyblank, 1990: 21-26; Dobrovitz, 2011: 375-378), and before that the Dīnglíng, perhaps a rendering of *tegreg "wagon", a Tuoba/Tabgač exonym for Tiele (Kljaštornyj, 2010: 162-163; Golden, 2012 : 179-180.)"

- Cosmo, Nicola Di; Maas, Michael (26 April 2018). Empires and Exchanges in Eurasian Late Antiquity: Rome, China, Iran, and the Steppe, ca. 250–750. Cambridge University Press. p. 326. ISBN 978-1-108-54810-6. "55 Chinese accounts of the Northern Wei era also termed them Gaoche “high carts,” seemingly a translation of Dingling et al.: E. G. Pulleyblank, “The 'High Carts': A Turkish Speaking People before the Türks,” Asia Major 3.1 (1990) 21–26."

- PULLEYBLANK, EDWIN G. (1990). "The "High Carts": A Turkish-Speaking People Before the Türks". Asia Major. 3 (1): 22. ISSN 0004-4482. JSTOR 41645442. "The name Ting-ling continued to be used occasionally but other forms soon became more common. One is the Chinese Kao-ch'e "High Carts," which is explained as referring to their wagons with very large wheels. The others, Ti-li, T'e-le, Ch'ih-le, Chih-le, and T'ieh-le,4 which are obviously transcriptions of foreign names, are evidently new transcriptions of the name that underlay Ting-ling. James Hamilton proposes to interpret this as *Tägräg, a word defined in Kashgari's dictionary as "circle, hoop."5 The Chinese term "High Carts" was therefore probably not merely descriptive of their habits but related to the meaning of the Turkish name."

- Yu Huan, Weilüe, quoted in Chen Shou, Sanguozhi, vol. 30 Xirong, draft translation by John E. Hil 2004 Section 28

- Sima Qian Records of the Grand Historian Vol. 110 "後北服渾庾、屈射、丁零、鬲昆、薪犁之國。於是匈奴貴人大臣皆服,以冒頓單于爲賢。" tr. "Later north subjugated the nations of Hunyu, Qushe, Dingling, Gekun, and Xinli. Therefore, the Xiongnu nobles and dignitaries all admired considered Modun chanyu as capable."

- Murphy, Eileen M. (2003). Iron Age Archaeology and Trauma from Aymyrlyg, South Siberia. Archaeopress. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-84171-522-3. "...the country of Dinlin , which was located in the Minusinsk Basin on the Yenisey river."

- Lu (1996), pp. 111, 135-137.

- Li (2003), pp. 110-112.

- A. J. Haywood, Siberia: A Cultural History, Oxford University Press, 2010, p.203

- Andrews, Peter A. (1999). Felt Tents and Pavilions: The Nomadic Tradition and Its Interaction with Princely Tentage. Melisende. p. 89. ISBN 978-1-901764-03-1.

- Bloom, Jonathan; Blair, Sheila S.; Blair, Sheila (14 May 2009). Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art & Architecture: Three-Volume Set. OUP USA. p. 281. ISBN 978-0-19-530991-1. "...among the Hsiung-nu and the High Cart confederation. Since the Turkic type, with its dependence on wood bending techniques, can be related to bent wooden wheels (c. 350 bce) found in barrow No. V at Pazyryk in Siberia, deriving from a tradition a millennium older, the connection with these cart dwelling nomads is significant."

- Xue (1992), pp. 54-60.

- Lu (1996), pp. 305-320.

- Duan (1988) pp. 35-53.

- Duan (1988) pp. 8-11.

- Duan (1988), pp. 1-6

- Suribadalaha (1986), p. 27.

- Theobald, Ulrich (2012). Di 狄 in ChinaKnowledge.de - An Encyclopaedia on Chinese History, Literature and Art

- Lu (1996), p. 136.

- Shen (1998), p. 75.

- Li (2003), p. 73.

- Duan (1988) pp. 99-100.

- Duan (1988) pp. 101-103.

- Duan (1988) pp. 111-113.

- Hill (2004), Section 28

- Duan (1988), pp. 137-142, 152-158.

- Duan (1988), pp. 148-152.

- Rhyne, George N.; Adams, Bruce Friend (2007). The Supplement to The Modern Encyclopedia of Russian, Soviet and Eurasian History: Deni, Viktor Nikolaevich - Dzhungaria. Academic International Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-87569-142-8.

- Hyun Jin Kim: The Huns, Rome and the Birth of Europe. Cambridge University Press, 2013. pp.175-176.

- Peter B. Golden: Some Thoughts on the Origins of the Turks and the Shaping of the Turkic Peoples in Contact and Exchange in the Ancient World. Ed. Victor H. Mair. University of Hawaii Press, 2006. p.140

- “Section 28 – The Kingdom of Dingling (Around Lake Baikal and on the Irtish River)” note 28.3 The Peoples of the West from the Weilue 魏略 by Yu Huan 魚豢 A Third Century Chinese Account Composed between 239 and 265 CE Quoted in zhuan 30 of the Sanguozhi Published in 429 CE Draft English translation by John E. Hill (September, 2004)

- Pulleyblank, E. G. (1962) "The consonantal system of Old Chinese. Part II" pdf, Asia Major 9; p. 226 of 206‒65.

- Schuessler (2014), p. 258, 273

- Starostin, Sergei; Dybo, Anna; Mudrak, Oleg (2003), “*KArsak”, in Etymological dictionary of the Altaic languages (Handbuch der Orientalistik; VIII.8), Leiden, New York, Köln: E.J. Brill

- Xu (2005), p. 86; quote: "The ancestors of the Mongols are believed to be the Mengwu Shiwei (Mengwa Shiwei) who appeared in history as late as in the Tang Dynasty (618-907)."; p. 184

- Werner, Heinrich Zur jenissejisch-indianischen Urverwandtschaft. Harrassowitz Verlag. 2004 abstract

- Russian Translation Series of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University. Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University. 1964. p. 10. "It is quite probable that the inhabitants of the Upper Yenissei during the epoch of the Tagar culture were characterized by light pigmentation (light hair and light eyes). This point of view was also held by Debets in one of his earlier published works concerning the so - called "blond Dinlin race," which at the time Debets wrote gave rise to an extensive literature."

- Alekseev, Valerij P.; Gochman, Il'ja I. (3 December 2018). Asien II: Sowjet-Asien. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. p. 39. ISBN 978-3-486-82294-6. "For instance, the tribes which came from the upper Yenisei are called "dinlin" and they are described as fair pigmented in comparison with the Chinese (Bičurin, 1950-1953; Grumm Grzimajlo 1899, 1926)."

- Keyser, Christine; Bouakaze, Caroline; Crubézy, Eric; Nikolaev, Valery G.; Montagnon, Daniel; Reis, Tatiana; Ludes, Bertrand (May 16, 2009). "Ancient DNA provides new insights into the history of south Siberian Kurgan people". Human Genetics. 126 (3): 395–410. doi:10.1007/s00439-009-0683-0. PMID 19449030. S2CID 21347353.

- Mayor, Adrienne (9 February 2016). The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World. Princeton University Press. p. 421. ISBN 978-0-691-17027-5. "...the Dingling (described as “red-haired, blue-eyed giants,” perhaps related to the Altai, Tuva, Pazyryk, Kyrgyz cultures);"

- Dorina, M.V. (27 September 2017). "Fine arts and music: The cultural links of Southern Siberia and India". Eurasia and India: Regional Perspectives. Routledge. p. 106. ISBN 978-1-351-69195-6. "It was the time of intensive interracial marriages of European-looking men (dinlin) and the Turkic language–speaking Mongols (guangun-kyrgyz),"

- Lee, Joo-Yup; Kuang, Shuntu (18 October 2017). "A Comparative Analysis of Chinese Historical Sources and y-dna Studies with Regard to the Early and Medieval Turkic Peoples". Inner Asia. 19 (2): 197–239. doi:10.1163/22105018-12340089. ISSN 1464-8172. S2CID 165623743.

- A Chinese bestiary: strange creatures from the guideways through mountains and seas. Translated by Richard E. Strassberg. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. (2002). p. 226.

- Mairs, Rachel (29 November 2020). The Graeco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek World. Routledge. p. 460. ISBN 978-1-351-61028-5.

- "Weilue: The Peoples of the West". depts.washington.edu. "...north of the Dingling (丁令) is the kingdom of Majing (馬脛 ‘Horses Shanks’). These men make sounds like startled wild geese. From above the knee, they have the body and hands of a man, but below the knees, they grow hair, and have horses’ legs and hooves. They don't ride horses as they can run faster than horses. They are brave, strong, and daring fighters".

Further reading

- Duan, Lianqin (1988). Dingling, Gaoju and Tiele. Shanghai: Shanghai People's Press, 1988.

- Hill, John E. (2004). "The Peoples of the West" from the Weilüe, Section 15. (Draft version). Downloadable from: .

- Li, Jihe (2003). A Research on Migration of Northwestern Minorities Between pre-Qin to Sui and Tang. Beijing: Nationalities Press.

- Lu, Simian (1996). A History of Ethnic Groups in China. Beijing: Oriental Press.

- Shen, Youliang (1998). A Research on Northern Ethnic Groups and Regimes. Beijing: Central Nationalities University Press.

- Suribadalaha (1986). New Studies of the Origins of the Mongols. Beijing: Nationalities Press.

- Trever, Camilla (1932). Excavations in Northern Mongolia (1924-1925). Leningrad: J. Fedorov Printing House.

- Xue, Zongzheng (1992). A History of Turks. Beijing: Chinese Social Sciences Press.

| Historical non-Han peoples in China | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ancient |

|  | ||||||||

| Medieval |

| |||||||||

| Early Modern |

| |||||||||