| Revision as of 14:02, 5 November 2021 editEhrenkater (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users62,179 editsm →Etymology← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 19:48, 3 December 2024 edit undo212.200.164.108 (talk) →See also | ||

| (99 intermediate revisions by 55 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| ⚫ | {{Short description|Collection of maps}} | ||

| {{ |

{{About|a collection of maps|the Titan condemned to hold the heavens on his shoulders|Atlas (mythology)|the particle detector experiment|ATLAS experiment|other uses}} | ||

| ⚫ | {{ |

||

| {{Distinguish|Atlus}} | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ⚫ | ] |

||

| ]'', by ]. Cornelis was the son of ]. When his father died in 1591, Cornelis de Jode took over the work on his father's uncompleted atlas project (''Speculum Orbis Terrarum'', originally published in 1578), which he eventually published in 1593.]] | |||

| ⚫ | ]'s ], originally prepared by ] for his '']'', published in the first book of the '']'' (1664).]] | ||

| ⚫ | ] (1742)]] | ||

| An '''atlas''' is a collection of ]s; it is typically a bundle of ] or of a region of ]. | |||

| Atlases have traditionally been bound into book form, but today many atlases are in ] formats. |

An '''atlas''' is a collection of ]s; it is typically a bundle of ] or of a ] or region of ]. | ||

| Atlases have traditionally been bound into ] form, but today, many atlases are in ] formats. In addition to presenting ] features and ], many atlases often feature ], social, ], and ] ]. They also have information about the map and places in it. | |||

| ==Etymology== | ==Etymology== | ||

| ⚫ | The use of the word "atlas" in a geographical context dates from 1595 when the German-Flemish geographer ] published {{lang|la|Atlas Sive Cosmographicae Meditationes de Fabrica Mundi et Fabricati Figura}} ("Atlas or cosmographical meditations upon the creation of the universe and the universe as created"). This title provides Mercator's definition of the word as a description of the creation and form of the whole universe, not simply as a collection of maps. The volume that was published posthumously one year after his death is a wide-ranging text but, as the editions evolved, it became simply a collection of maps and it is in that sense that the word was used from the middle of the 17th century. The neologism coined by Mercator was a mark of his respect for the Titan ], the "King of Mauretania", whom he considered to be the first great geographer.<ref>Mercator's own account of the reasons for choosing King Atlas are given in the preface of the 1595 atlas. A translation by David Sullivan is available in a digital version of the atlas published by . The text is freely available at the {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160310032427/http://mail.nysoclib.org/Mercator_Atlas/MCRATS.PDF|date=March 10, 2016}}, pdf page 104 (corresponding to p. 34 of Sullivan's text).</ref> | ||

| {{See also|Early modern Netherlandish cartography|l1=Early modern Netherlandish cartography and geography}} | |||

| ⚫ | The |

||

| ==History of atlases== | ==History of atlases== | ||

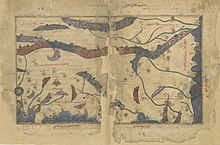

| ] ''Nuzhat al-Mushtāq'' ({{Lang|ar|نزهة المشتاق في اختراق الآفاق}}), also known as the {{Lang|la|]}} (12th century).<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Idrīsī |first1=Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad al-Šarīf Abū ʿAbd Allâh al- (1100?-1165?) Auteur du texte |url=https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b6000547t |title=Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad al-Idrīsī. Nuzhat al-muštāq fī iḫtirāq al-āfāq. |last2=texte |first2=محمد بن محمد الإديسي Auteur du |last3=texte |first3=AL-IDRĪSĪ Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad Auteur du |date=1250–1325 |language=EN}}</ref>]] | |||

| ⚫ | The first work that contained systematically arranged maps of uniform size representing the first modern atlas was prepared by Italian cartographer ] in the early 16th century; however it was not published at that time, so it is conventionally not considered the first atlas. Rather, that title is awarded to the collection of maps |

||

| ⚫ | ]}} (''Theatre of the Orb of the World'') by ], 1570]] | ||

| ⚫ | ]'s ], originally prepared by ] for his '']'', published in the first book of the '']'' (1664).]] | ||

| ⚫ | ] (1742)]] | ||

| ] | |||

| ⚫ | The first work that contained systematically arranged maps of uniform size representing the first modern atlas was prepared by Italian cartographer ] in the early 16th century; however, it was not published at that time, so it is conventionally not considered the first atlas. Rather, that title is awarded to the collection of maps {{Lang|la|]}} by the ] cartographer ] printed in 1570.{{Citation needed|date=February 2023}} | ||

| ⚫ | Atlases published nowadays are quite different from those published in the 16th–19th centuries. Unlike today, most atlases were not bound and ready for the customer to buy, but their possible components were shelved separately. The client could select the contents to their liking, and have the maps coloured/gilded or not. The atlas was then bound. Thus, early printed atlases with the same title page can be different in contents.<ref>Jan Smits, Todd Fell (2011). Early printed atlases: shaping Plato's 'Forms' into bibliographic descriptions. In: ''Journal of map & geography libraries : advances in geospatial information, collections & archives'', (ISSN 1542-0353), 7(2011)2, p. 184-210.</ref> | ||

| States began producing national atlases in the 19th century.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Short |first=John Rennie |url=http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv2s2pp1m |title=The Rise and Fall of the National Atlas in the Twentieth Century: Power, State and Territory |date=2022 |publisher=Anthem Press |isbn=978-1-83998-304-7 |doi=10.2307/j.ctv2s2pp1m|jstor=j.ctv2s2pp1m |s2cid=250944397 }}</ref> | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ==Types of atlases== | ==Types of atlases== | ||

| A ''travel atlas'' is made for easy use during travel, and often has spiral bindings so it may be folded flat (for example ] |

A ''travel atlas'' is made for easy use during travel, and often has spiral bindings, so it may be folded flat. National atlases in Europe are typically printed at a scale of 1:250,000 to 1:500,000;{{efn|about 4 miles to the inch to about 7{{sfrac|2}} miles/inch}} city atlases are 1:20,000 to 1:25,000,{{efn|about 3 inches/mile to 2{{sfrac|2}} inches/mile}} doubling for the central area (for example, ]'s A–Z atlas of ] is 1:22,000 for ] and 1:11,000 for ]).{{efn|About 4 inches/mile and 8 inches/mile.}}<ref>{{cite book |title=A-Z London |publisher=Geographers' A-Z Map Company |isbn=9780850394900}}</ref> A travel atlas may also be referred to as a ''road map''.<ref>{{cite dictionary| url= http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/road%20map|title=Road map|dictionary= Merriam Webster|access-date=2012-05-31}}</ref> | ||

| A ''desk atlas'' is made similar to a reference book. It may be in hardback or paperback form. | A ''desk atlas'' is made similar to a ]. It may be in hardback or paperback form. | ||

| There are atlases of the other planets (and their satellites) in the ].<ref>{{cite book|title=The NASA Atlas of the Solar System| |

There are atlases of the other planets (and their satellites) in the ].<ref>{{cite book|title=The NASA Atlas of the Solar System|isbn=978-0521561273|author1=Greeley, Ronald|author2=Batson, Raymond}}</ref> | ||

| Atlases of ] exist, mapping out organs of the human body or other organisms.<ref>{{cite news |last=Schwartz |first=John |date=2008-04-22 |title=The Body in Depth |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2008/04/22/science/22bass.html |newspaper=The New York Times |access-date=2015-05-07 }}</ref> | Atlases of ] exist, mapping out organs of the human body or other organisms.<ref>{{cite news |last=Schwartz |first=John |date=2008-04-22 |title=The Body in Depth |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2008/04/22/science/22bass.html |newspaper=The New York Times |access-date=2015-05-07 }}</ref> | ||

| Line 30: | Line 34: | ||

| ==Selected atlases== | ==Selected atlases== | ||

| {{Main|List of atlases}} | {{Main|List of atlases}} | ||

| Some cartographically or commercially important atlases are: | Some cartographically or commercially important atlases are: | ||

| '''17th century and earlier''': | |||

| *{{lang|la|]}} 1570 atlas by ] | |||

| * |

*{{lang|la|]}} (Mercator, Duisburg, in present-day Germany, 1595) | ||

| ⚫ | * |

||

| * |

*{{lang|la|]}} (Joan Blaeu, Netherlands, 1635–1658) | ||

| ⚫ | *{{lang|la|]}} (Blaeu, Netherlands, 1662–1667) | ||

| * |

*{{Lang|fr|Cartes générales de toutes les parties du monde}} (France, 1658–1676) | ||

| * |

*{{lang|it|]}} (], England/Italy, 1645–1661) | ||

| *'']'' (Ottoman Empire, 1570–1612) | |||

| * |

*] (], Ottoman Empire, 1570–1612) | ||

| *{{Lang|la|]}} (Ortelius, Netherlands, 1570–1612) | |||

| *'']'' (1660; one of the world's largest books) | *'']'' (1660; one of the world's largest books) | ||

| * '']'' (1675), ] (1600–1676), first to be printed at a specific scale (1:63,360 or one inch to one mile | |||

| *''The Brittania'' (], 1670–1676) | |||

| '''18th century''' | |||

| * |

*{{Lang|fr|Atlas Nouveau}} (Amsterdam, 1742) | ||

| * |

*{{lang|la|]}} (London, 1720) | ||

| *'']'' (London, 1787) | *'']'' (London, 1787) | ||

| '''19th century''': | |||

| * |

*{{Lang|de|]}} (Germany, 1881–1939; in the UK as '']'', 1895) | ||

| *'']'' (United States, 1881–present) | *'']'' (United States, 1881–present) | ||

| * |

*{{Lang|de|]}} (Germany, 1817–1944) | ||

| *'']'' (United Kingdom, 1895–present) | *'']'' (United Kingdom, 1895–present) | ||

| '''20th century''': | |||

| * |

*{{lang|it|]}} (Italy, 1927–1978) | ||

| *'']'' (Austria, 1934) | *'']'' (Austria, 1934) | ||

| * |

*{{Lang|ru-latn|]}} (Soviet Union/Russia, 1937–present) | ||

| *'']'' (United Kingdom, 1938–present) | *'']'' (United Kingdom, 1938–present) | ||

| * |

*{{Lang|es|]}} (Spain, 1969/1970) | ||

| *'']'' (China) | *'']'' (China) | ||

| *'']'' of the World (United States, 1963–present) | *'']'' of the World (United States, 1963–present) | ||

| *'']'' (1962/1968) | *'']'' (1962/1968) | ||

| '''21st century''': | |||

| *'']'' | *'']'' | ||

| Line 70: | Line 76: | ||

| {{Div col|small=yes}} | {{Div col|small=yes}} | ||

| *'']'' | *'']'' | ||

| * |

* {{Annotated link |Bird atlas}} | ||

| * |

* {{Annotated link |Cartography}} | ||

| * |

* {{Annotated link |Cartopedia}} | ||

| * |

* {{Annotated link |Cloud atlas}} | ||

| * |

* {{Annotated link |European Atlas of the Seas}} | ||

| * |

* {{Annotated link |Fictitious entry}} | ||

| * |

* {{Annotated link |Geography}} | ||

| * |

* {{Annotated link |Google Maps}} | ||

| * |

* {{Annotated link |Manifold}} | ||

| * |

* {{Annotated link |NASA World Wind}} | ||

| * |

* {{Annotated link |National Atlas of the United States}} | ||

| * |

* {{Annotated link |Star atlas}} | ||

| * |

* {{Annotated link |TerraServer-USA}} | ||

| *] | |||

| {{Div col end}} | {{Div col end}} | ||

| ==Notes== | |||

| {{notelist}} | |||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| Line 92: | Line 100: | ||

| {{Commons}} | {{Commons}} | ||

| ;Sources | ;Sources | ||

| * | * {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200726110819/http://www.mapforum.com/01/atlas.htm |date=2020-07-26 }} | ||

| ;Online atlases | ;Online atlases | ||

| * | |||

| * | * | ||

| *: Atlas on spatial development in Austria | *: Atlas on spatial development in Austria | ||

| Line 108: | Line 117: | ||

| *, Perry–Castañeda Library, University of Texas | *, Perry–Castañeda Library, University of Texas | ||

| * Composite atlas with maps, plans and views from the 16th-18th centuries, covering the globe, with about 16,000 images in total. | * Composite atlas with maps, plans and views from the 16th-18th centuries, covering the globe, with about 16,000 images in total. | ||

| * - fully digitized with descriptions. | * {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220706230644/https://dla.library.upenn.edu/dla/medren/search.html?fq=genre_facet%3A%22Atlases%22 |date=2022-07-06 }} - fully digitized with descriptions. | ||

| *, ] | *, ] | ||

| ;Other links | ;Other links | ||

| Line 116: | Line 125: | ||

| {{Atlas}} | {{Atlas}} | ||

| {{Early modern Netherlandish cartography, geography and cosmography}} | |||

| {{Authority control}} | {{Authority control}} | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 19:48, 3 December 2024

Collection of maps This article is about a collection of maps. For the Titan condemned to hold the heavens on his shoulders, see Atlas (mythology). For the particle detector experiment, see ATLAS experiment. For other uses, see Atlas (disambiguation). Not to be confused with Atlus.

An atlas is a collection of maps; it is typically a bundle of maps of Earth or of a continent or region of Earth.

Atlases have traditionally been bound into book form, but today, many atlases are in multimedia formats. In addition to presenting geographical features and political boundaries, many atlases often feature geopolitical, social, religious, and economic statistics. They also have information about the map and places in it.

Etymology

The use of the word "atlas" in a geographical context dates from 1595 when the German-Flemish geographer Gerardus Mercator published Atlas Sive Cosmographicae Meditationes de Fabrica Mundi et Fabricati Figura ("Atlas or cosmographical meditations upon the creation of the universe and the universe as created"). This title provides Mercator's definition of the word as a description of the creation and form of the whole universe, not simply as a collection of maps. The volume that was published posthumously one year after his death is a wide-ranging text but, as the editions evolved, it became simply a collection of maps and it is in that sense that the word was used from the middle of the 17th century. The neologism coined by Mercator was a mark of his respect for the Titan Atlas, the "King of Mauretania", whom he considered to be the first great geographer.

History of atlases

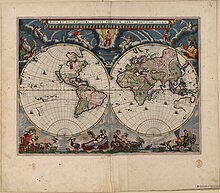

The first work that contained systematically arranged maps of uniform size representing the first modern atlas was prepared by Italian cartographer Pietro Coppo in the early 16th century; however, it was not published at that time, so it is conventionally not considered the first atlas. Rather, that title is awarded to the collection of maps Theatrum Orbis Terrarum by the Brabantian cartographer Abraham Ortelius printed in 1570.

Atlases published nowadays are quite different from those published in the 16th–19th centuries. Unlike today, most atlases were not bound and ready for the customer to buy, but their possible components were shelved separately. The client could select the contents to their liking, and have the maps coloured/gilded or not. The atlas was then bound. Thus, early printed atlases with the same title page can be different in contents.

States began producing national atlases in the 19th century.

Types of atlases

A travel atlas is made for easy use during travel, and often has spiral bindings, so it may be folded flat. National atlases in Europe are typically printed at a scale of 1:250,000 to 1:500,000; city atlases are 1:20,000 to 1:25,000, doubling for the central area (for example, Geographers' A-Z Map Company's A–Z atlas of London is 1:22,000 for Greater London and 1:11,000 for Central London). A travel atlas may also be referred to as a road map.

A desk atlas is made similar to a reference book. It may be in hardback or paperback form.

There are atlases of the other planets (and their satellites) in the Solar System.

Atlases of anatomy exist, mapping out organs of the human body or other organisms.

Selected atlases

Main article: List of atlasesSome cartographically or commercially important atlases are:

17th century and earlier:

- Theatrum Orbis Terrarum 1570 atlas by Abraham Ortelius

- Atlas Sive Cosmographicae Meditationes de Fabrica Mundi et Fabricati Figura (Mercator, Duisburg, in present-day Germany, 1595)

- Atlas Novus (Joan Blaeu, Netherlands, 1635–1658)

- Atlas Maior (Blaeu, Netherlands, 1662–1667)

- Cartes générales de toutes les parties du monde (France, 1658–1676)

- Dell'Arcano del Mare (Robert Dudley, England/Italy, 1645–1661)

- Piri Reis map (Piri Reis, Ottoman Empire, 1570–1612)

- Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (Ortelius, Netherlands, 1570–1612)

- Klencke Atlas (1660; one of the world's largest books)

- Britannia (1675), John Ogilby (1600–1676), first to be printed at a specific scale (1:63,360 or one inch to one mile

18th century

- Atlas Nouveau (Amsterdam, 1742)

- Britannia Depicta (London, 1720)

- Cary's New and Correct English Atlas (London, 1787)

19th century:

- Andrees Allgemeiner Handatlas (Germany, 1881–1939; in the UK as Times Atlas of the World, 1895)

- Rand McNally Atlas (United States, 1881–present)

- Stielers Handatlas (Germany, 1817–1944)

- Times Atlas of the World (United Kingdom, 1895–present)

20th century:

- Atlante Internazionale del Touring Club Italiano (Italy, 1927–1978)

- Atlas Linguisticus (Austria, 1934)

- Atlas Mira (Soviet Union/Russia, 1937–present)

- Geographers' A–Z Street Atlas (United Kingdom, 1938–present)

- Gran Atlas Aguilar (Spain, 1969/1970)

- The Historical Atlas of China (China)

- National Geographic Atlas of the World (United States, 1963–present)

- Pergamon World Atlas (1962/1968)

21st century:

See also

- Atlas of Our Changing Environment

- Bird atlas – Ornithological data in map form

- Cartography – Study and practice of making maps

- Cartopedia – Atlas computer program

- Cloud atlas – Compendium of cloud types

- European Atlas of the Seas – Web-based atlas

- Fictitious entry – Deliberately incorrect entry in a reference work

- Geography – Study of lands and inhabitants of Earth

- Google Maps – Google's web mapping service (launched 2005)

- Manifold – Topological space that locally resembles Euclidean space

- NASA World Wind – Open-source virtual globePages displaying short descriptions of redirect targets

- National Atlas of the United States – Atlas published by the United States Department of the Interior from 1874-1997

- Star atlas – Part of astronomy concerned with mapping of starsPages displaying short descriptions of redirect targets

- TerraServer-USA – Online repository of US aerial imageryPages displaying short descriptions of redirect targets

Notes

- about 4 miles to the inch to about 71/2 miles/inch

- about 3 inches/mile to 21/2 inches/mile

- About 4 inches/mile and 8 inches/mile.

References

- Mercator's own account of the reasons for choosing King Atlas are given in the preface of the 1595 atlas. A translation by David Sullivan is available in a digital version of the atlas published by Octavo. The text is freely available at the New York Society Library Archived March 10, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, pdf page 104 (corresponding to p. 34 of Sullivan's text).

- Idrīsī, Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad al-Šarīf Abū ʿAbd Allâh al- (1100?-1165?) Auteur du texte; texte, محمد بن محمد الإديسي Auteur du; texte, AL-IDRĪSĪ Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad Auteur du (1250–1325). Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad al-Idrīsī. Nuzhat al-muštāq fī iḫtirāq al-āfāq.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Jan Smits, Todd Fell (2011). Early printed atlases: shaping Plato's 'Forms' into bibliographic descriptions. In: Journal of map & geography libraries : advances in geospatial information, collections & archives, (ISSN 1542-0353), 7(2011)2, p. 184-210.

- Short, John Rennie (2022). The Rise and Fall of the National Atlas in the Twentieth Century: Power, State and Territory. Anthem Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctv2s2pp1m. ISBN 978-1-83998-304-7. JSTOR j.ctv2s2pp1m. S2CID 250944397.

- A-Z London. Geographers' A-Z Map Company. ISBN 9780850394900.

- "Road map". Merriam Webster. Retrieved 2012-05-31.

- Greeley, Ronald; Batson, Raymond. The NASA Atlas of the Solar System. ISBN 978-0521561273.

- Schwartz, John (2008-04-22). "The Body in Depth". The New York Times. Retrieved 2015-05-07.

External links

- Sources

- On the origin of the term "Atlas" Archived 2020-07-26 at the Wayback Machine

- Online atlases

- Wikimedia Commons Atlas of the World

- World Atlas

- ÖROK-Atlas Online: Atlas on spatial development in Austria

- Geography Network

- MapChart EarthAtlas, free online atlas with interactive maps about topics like demography, economy, health and environment.

- National Geographic MapMachine

- History of atlases

- Atlases, at the US Library of Congress site - a discussion of many significant atlases, with some illustrations. Part of Geography and Maps, an Illustrated Guide.

- Historical atlases online

- Centennia Historical Atlas required reading at the US Naval Academy for over a decade.

- Historical map web sites list, Perry–Castañeda Library, University of Texas

- Ryhiner Collection Composite atlas with maps, plans and views from the 16th-18th centuries, covering the globe, with about 16,000 images in total.

- Manuscript Atlases held by the University of Pennsylvania Libraries Archived 2022-07-06 at the Wayback Machine - fully digitized with descriptions.

- Historical Atlas in Persuasive Cartography, The PJ Mode Collection, Cornell University Library

- Other links

- Google Earth: a visual 3D interactive atlas.

- NASA's World Wind software.

- Wikimapia a wikiproject designed to describe the entire world.

| Atlas | |

|---|---|