| Revision as of 06:41, 20 November 2021 editBrendenr1998 (talk | contribs)16 editsm Added a commaTag: Visual edit← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 16:53, 7 January 2025 edit undoSkywatcher68 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users22,513 editsm Field "Birth Name" is not applicable here. | ||

| (180 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|American psychologist}} | {{short description|American psychologist (1908–1970)}} | ||

| {{pp- |

{{pp-pc}} | ||

| {{Use American English|date=January 2023}} | |||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=January 2023}} | |||

| {{Infobox scientist | {{Infobox scientist | ||

| |name = Abraham Maslow | | name = Abraham Maslow | ||

| |image = Abraham Maslow.jpg | | image = Abraham Maslow.jpg | ||

| | birth_name = <!-- only use if different from name --> | |||

| |birth_name=Abraham Harold Maslow | |||

| |birth_date = {{birth |

| birth_date = {{birth date text|April 1, 1908}} | ||

| |birth_place = ], |

| birth_place = ], New York City, U.S. | ||

| |death_date = {{death date and age|mf=yes|1970|06|08|1908|04|01}} | | death_date = {{death date and age|mf=yes|1970|06|08|1908|04|01}} | ||

| |death_place = ], ], U.S. | | death_place = ], U.S. | ||

| |spouse = {{marriage|Bertha Goodman Maslow|December 31, 1928}} | | spouse = {{marriage|Bertha Goodman Maslow|December 31, 1928}} | ||

| |children |

| children = 2 | ||

| | |

| field = ] | ||

| ⚫ | | work_institution = {{unbulleted list | ] | ] | ] | ]}} | ||

| |field = ] | |||

| ⚫ | | doctoral_advisor = ] | ||

| ⚫ | |work_institution = {{unbulleted list | ] | ] | ]}} | ||

| | |

| known_for = ] | ||

| | education = ]<br />]<br>] | |||

| ⚫ | |doctoral_advisor = ] | ||

| |influences = {{hlist | ] | ] | ]}} | |||

| |influenced = {{hlist | ] | ]<ref>Assagioli Roberto. ''Act of Will''. New York: Synthesis Center Press, 2010. Print.</ref> | ] | ] | ] | ]}} | |||

| |known_for = ] | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''Abraham Harold Maslow''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|m|æ|z|l|oʊ}}; April 1, 1908 |

'''Abraham Harold Maslow''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|m|æ|z|l|oʊ}} {{respell|MAZ|loh}}; April 1, 1908 – June 8, 1970) was an American psychologist who created ], a theory of psychological health predicated on fulfilling innate human needs in priority, culminating in self-actualization.<ref name=obit>{{cite news |title=Dr. Abraham Maslow, Founder Of Humanistic Psychology, Dies |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1970/06/10/archives/dr-abraham-maslow-founder-of-humanistic-psychology-dies.html |quote=Dr. Abraham Maslow, professor of psychology at Brandeis University in Waltham, Mass., and founder of what has come to be known as humanistic psychology, died of a heart attack. He was 62 years old. |work=] |date=June 10, 1970 |access-date=September 26, 2010 |archive-date=September 3, 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160903190052/http://www.nytimes.com/1970/06/10/archives/dr-abraham-maslow-founder-of-humanistic-psychology-dies.html? |url-status=live }}</ref> Maslow was a ] professor at ], ], ], and ]. He stressed the importance of focusing on the positive qualities in people, as opposed to treating them as a "bag of symptoms".<ref name=hoffman109>], p. 109.</ref> A '']'' survey, published in 2002, ranked Maslow as the tenth most cited psychologist of the 20th century.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Haggbloom |first1=Steven J. |title=The 100 most eminent psychologists of the 20th century |journal=Review of General Psychology |volume=6 |issue=2 |year=2002 |pages=139–152 |doi=10.1037/1089-2680.6.2.139 |url=http://www.apa.org/monitor/julaug02/eminent.aspx |last2=Warnick |first2=Renee |last3=Warnick |first3=Jason E. |last4=Jones |first4=Vinessa K. |last5=Yarbrough |first5=Gary L. |last6=Russell |first6=Tenea M. |last7=Borecky |first7=Chris M. |last8=McGahhey |first8=Reagan |last9=Powell |first9=John L. III |display-authors=8 |citeseerx=10.1.1.586.1913 |s2cid=145668721 |access-date=June 9, 2015 |archive-date=October 3, 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181003220828/https://www.apa.org/monitor/julaug02/eminent.aspx |url-status=live }}</ref> | ||

| ==Biography== | ==Biography== | ||

| ===Youth=== | ===Youth=== | ||

| Born in 1908 and raised in ], Maslow was the oldest of seven children. His parents were first-generation ] immigrants from Kiev, then part of the ] (now ], ]), who fled from Czarist persecution in the early 20th century.<ref name="Boeree">{{cite web|author=Boeree, C.|year=2006|url=http://webspace.ship.edu/cgboer/maslow.html/|title=Abraham Maslow|publisher=Webspace.ship.edu|access-date= |

Born in 1908 and raised in ], Maslow was the oldest of seven children. His parents were first-generation ] immigrants from Kiev, then part of the ] (now ], ]), who fled from ] ] in the early 20th century.<ref name="Boeree">{{cite web|author=Boeree, C.|year=2006|url=http://webspace.ship.edu/cgboer/maslow.html/|title=Abraham Maslow|publisher=Webspace.ship.edu|access-date=October 21, 2012|archive-date=April 30, 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160430023433/http://webspace.ship.edu/cgboer/maslow.html}}</ref><ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240723031629/https://books.google.com/books?id=ZCvrS9DjE68C&q=Abraham+Maslow+Kiev&pg=PT322 |date=July 23, 2024 }} by ], Arrow Books, {{ISBN|0099471477}}, 2004</ref> They had decided to live in New York City and in a multiethnic, working-class neighborhood.<ref>{{cite web|title=Maslow, Abraham H.|url=http://www.encyclopedia.com/article-1G2-3456300032/maslow-abraham-h.html|access-date=April 3, 2016|archive-date=April 19, 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160419071439/http://www.encyclopedia.com/article-1G2-3456300032/maslow-abraham-h.html|url-status=live}}</ref> His parents were poor and not intellectually focused, but they valued education. He had various encounters with ] gangs who would chase and throw rocks at him.<ref>], p. 9.</ref> Maslow and other young people with his background were struggling to overcome such acts of racism and ethnic prejudice in an attempt to establish an idealistic world based on widespread education and economic justice.{{Editorializing|date=December 2024}}<ref>''Journal of Humanistic Psychology'' (October 2008), 48 (4), pp. 439–443</ref> | ||

| The tension outside his home was also felt within it, as he rarely got along with his mother and eventually developed a strong revulsion towards her. He is quoted as saying, "What I had reacted to was not only her physical appearance, but also her values and world view, her stinginess, her total selfishness, her lack of love for anyone else in the world—even her own husband and children—her narcissism, her Negro prejudice, her exploitation of everyone, her assumption that anyone was wrong who disagreed with her, her lack of friends, her sloppiness and dirtiness...". He also grew up with few friends other than his cousin Will, and as a result, he "grew up in libraries and among books".<ref>], p. 11.</ref> It was here that he developed his love for reading and learning. He went to ], one of the top high schools in Brooklyn, where his best friend was his cousin ].<ref>], p. 10, 12</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Lowry |first=Richard J. |title=The Journals of A.H. Maslow Vol. 1 |publisher=Brooks/Cole Publishing Co. |year=1979 |location=Monterey, CA |pages=231, 388}}</ref> Here, he served as the officer to many academic clubs and became editor of the Latin magazine. He also edited ''Principia,'' the school's physics paper, for a year.<ref>], p. 13.</ref> He developed other strengths as well: {{blockquote|As a young boy, Maslow believed physical strength to be the single most defining characteristic of a true male; hence, he exercised often and took up weight lifting in hopes of being transformed into a more muscular, tough-looking guy, however, he was unable to achieve this due to his humble-looking and chaste figure as well as his studiousness.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Nicholson |first1=Ian A. M. |title='Giving up maleness': Abraham Maslow, masculinity, and the boundaries of psychology. |journal=History of Psychology |date=2001 |volume=4 |issue=1 |pages=79–91 |doi=10.1037/1093-4510.4.1.79 }}</ref>}} | |||

| ===College and university=== | ===College and university=== | ||

| Maslow attended the ] after high school. In 1926 he began taking legal studies classes at night in addition to his undergraduate course load. He hated it and almost immediately dropped out. In 1927 he transferred to Cornell |

Maslow attended the ] after high school. In 1926, he began taking legal studies classes at night in addition to his undergraduate course load. He hated it and almost immediately dropped out. In 1927, he transferred to Cornell but left after just one semester due to poor grades and high costs.<ref>], p. 30.</ref> He later graduated from City College and went to graduate school at the ] (UW) to study ]. In 1928, he married his first cousin, Bertha, who was still in high school. The pair had met in Brooklyn years earlier.<ref>], p. 40.</ref> | ||

| Maslow's psychology training at UW was decidedly experimental-behaviorist.<ref>], p. 39.</ref> At Wisconsin, he pursued a line of research that included investigating ] ] behavior and ]. Maslow's early experience with ] would leave him with a strong ] mindset.<ref name=autogenerated1>{{cite journal|author=Hoffman, E|year=2008|title=Abraham Maslow: A Biographer's Reflection|journal=Journal of Humanistic Psychology|volume= 48|issue=4|pages=439–443|doi=10.1177/0022167808320534|s2cid=144442841}}</ref> Upon the recommendation of professor Hulsey Cason, Maslow wrote his master's thesis on "learning, retention, and reproduction of verbal material".<ref>], p. 44.</ref> Maslow regarded the research as embarrassingly trivial, but he completed his thesis in the summer of 1931 and was awarded his master's degree in psychology. He was so ashamed of the thesis that he removed it from the psychology library and tore out its catalog listing.<ref>], p. 45.</ref> However, Cason admired the research enough to urge Maslow to submit it for publication. Maslow's thesis was published as two articles in 1934.{{cn|date=December 2024}} | |||

| ===Academic career=== | ===Academic career=== | ||

| Maslow continued his research on similar themes at ]. There he found another mentor in ], one of ]'s early colleagues. From 1937 to 1951, Maslow was on the faculty of ]. His family life and his experiences influenced his psychological ideas. After ], Maslow began to question how psychologists had come to their conclusions, and though he did not completely disagree, he had his own ideas on how to understand the human mind.<ref>], p. 42.</ref> He called his new discipline ]. Maslow was already a 33-year-old father and had two children when the United States entered World War II in 1941. He was thus ineligible for the military. However, the horrors of war inspired a vision of peace in him, leading to his groundbreaking psychological studies of self-actualizing.{{Editorializing|date=December 2024}} The studies began under the supervision of two mentors, ] ] and ] ], whom he admired both professionally and personally. They accomplished a lot in both realms. Being such "wonderful human beings" also inspired Maslow to take notes about them and their behavior. This would be the basis of his lifelong research and thinking about ] and ].<ref>{{cite journal |title=Abraham Maslow: a biographer's reflections |author=Edward Hoffman |year=2008 |journal=] |volume=48 |issue=4 |pages=439–443 |doi=10.1177/0022167808320534|s2cid=144442841 }}</ref> | |||

| Maslow extended the subject, borrowing ideas from other psychologists and adding new ones, such as the concepts of a ], ], ], ] persons, and ]. He was a professor at ] from 1951 to 1969. He became a resident fellow of the Laughlin Institute in California. In 1967, Maslow had a serious heart attack and knew his time was limited. He considered himself to be a psychological pioneer.{{Fact or opinion|date=December 2024}} He pushed future psychologists by bringing to light different paths to ponder.<ref>Thoreau, H. (1962). ''Thoreau: Walden and other writings''. New York: Bantam Books. (Original work published 1854)</ref> He built the framework that later allowed other psychologists to conduct more comprehensive studies. Maslow believed that leadership should be non-intervening. Consistent with this approach, he rejected a nomination in 1963 to be the Association for ] president because he felt the organization should develop an intellectual movement without a leader.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Miles Vich |year=2008 |title=Maslow's leadership legacy |journal=] |volume=48 |issue=4 |pages=444–445 |doi=10.1177/0022167808320540|s2cid=144506755 }}</ref> | |||

| ===Death=== | ===Death=== | ||

| While jogging, Maslow |

While jogging, Maslow had a severe ] and died on June 8, 1970, at the age of 62 in ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.muskingum.edu/~psych/psycweb/history/maslow.htm|title=Psychology History|work=muskingum.edu|access-date=December 20, 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151220204237/http://www.muskingum.edu/~psych/psycweb/history/maslow.htm|archive-date=December 20, 2015}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |title=Dr. Abraham Maslow, Founder Of Humanistic Psychology, Dies |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1970/06/10/archives/dr-abraham-maslow-founder-of-humanistic-psychology-dies.html |quote=Dr. Abraham Maslow, professor of psychology at Brandeis University in Waltham, Mass., and founder of what has come to be known as humanistic psychology, died of a heart attack. He was 62 years old. |work=] |date=June 10, 1970 |access-date=September 26, 2010 |archive-date=September 3, 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160903190052/http://www.nytimes.com/1970/06/10/archives/dr-abraham-maslow-founder-of-humanistic-psychology-dies.html? |url-status=live }}</ref> He is buried at ]. | ||

| ==Maslow's contributions== | ==Maslow's contributions== | ||

| Line 44: | Line 49: | ||

| The basic principles behind humanistic psychology are simple: | The basic principles behind humanistic psychology are simple: | ||

| * Someone's present functioning is their most significant aspect. As a result, humanists emphasize the here and now instead of examining the past or attempting to predict the future. | |||

| * To be mentally healthy, individuals must take personal responsibility for their actions, regardless of whether the actions are positive or negative. | |||

| * Each person, simply by being, is inherently worthy. While any given action may be negative, these actions do not cancel out the value of a person. | |||

| * The ultimate goal of living is to attain personal growth and understanding. Only through constant self-improvement and self-understanding can an individual ever be truly happy.<ref name="Humanistic Psychology">{{cite web|title=Humanistic Psychology |url=http://www.abraham-maslow.com/m_motivation/Humanistic_Psychology.asp |access-date=August 21, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120824115841/http://www.abraham-maslow.com/m_motivation/Humanistic_Psychology.asp |archive-date=August 24, 2012 }}</ref> | |||

| Humanistic psychology theory suits people who see the positive side of humanity and believe in free will. This theory clearly contrasts with Freud's theory of ]. Another significant strength is that humanistic psychology theory is compatible with other schools of thought. Maslow's |

Humanistic psychology theory suits people who see the positive side of humanity and believe in free will. This theory clearly contrasts with Freud's theory of ]. Another significant strength is that humanistic psychology theory is compatible with other schools of thought. Maslow's hierarchy is also applicable to other topics, such as finance, economics, or even in history or criminology. Humanist psychology, also coined ''positive psychology'', is criticized for its lack of empirical validation and therefore its lack of usefulness in treating specific problems. It may also fail to help or diagnose people who have severe mental disorders.<ref name="Humanistic Psychology"/> ]s believe that every person has a strong desire to realize their full potential, to reach a level of "]". The main point of that new movement, that reached its peak in the 1960s, was to emphasize the positive potential of human beings.<ref>Schacter, Daniel L. "Psychology"</ref> Maslow positioned his work as a vital complement to that of Freud: | ||

| {{ |

{{blockquote|It is as if Freud supplied us the sick half of psychology and we must now fill it out with the healthy half.<ref>Toward a psychology of being, 1968</ref>}} | ||

| However, Maslow was highly critical of Freud, since humanistic psychologists did not recognize spirituality as a navigation for our |

However, Maslow was highly critical of Freud, since humanistic psychologists did not recognize spirituality as a navigation for our behaviors.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Morgan |first1=John H. |title=The Personal Meaning of Social Values in the Work of Abraham Maslow |journal=Interpersona |date=June 30, 2012 |volume=6 |issue=1 |pages=75–93 |doi=10.5964/ijpr.v6i1.91 |doi-access=free }}</ref> | ||

| ''Interpersona : An International Journal on Personal Relationships'', {{ISSN|1981-6472}}, 06/2012, Volume 6, Issue 1, pp. 75–93</ref> | |||

| To prove that humans are not blindly reacting to situations, but trying to accomplish something greater, Maslow studied mentally healthy individuals instead of people with serious psychological issues. He focused on self-actualizing people. Self-actualizing people indicate a ''coherent personality syndrome'' and represent optimal psychological health and functioning.<ref>{{cite journal | |

To prove that humans are not blindly reacting to situations, but trying to accomplish something greater, Maslow studied mentally healthy individuals instead of people with serious psychological issues. He focused on self-actualizing people. Self-actualizing people indicate a ''coherent personality syndrome'' and represent optimal psychological health and functioning.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Daniels |first1=Michael |title=The development of the concept of self-actualization in the writings of abraham Maslow |journal=Current Psychological Reviews |date=January 1982 |volume=2 |issue=1 |pages=61–75 |doi=10.1007/bf02684455 |s2cid=145003422 }}</ref> | ||

| This informed his theory that a person enjoys "]s", high points in life when the individual is in harmony with |

This informed his theory that a person enjoys "]s", high points in life when the individual is in harmony with themself and their surroundings. In Maslow's view, self-actualized people can have many peak experiences throughout a day while others have those experiences less frequently.<ref>], p. 43.</ref> He believed that psychedelic drugs like ] and ] can produce peak experiences in the right people under the right circumstances.<ref>{{Cite book|title=Religions, Values, and Peak Experiences|last=Maslow|first=Abraham H.|publisher=Ohio State University Press|year=1964}}</ref> | ||

| ===Peak and plateau experiences=== | ===Peak and plateau experiences=== | ||

| Beyond the routine of needs fulfillment, Maslow envisioned moments of extraordinary experience, known as ], which are profound moments of love, understanding, happiness, or rapture, during which a person feels more whole, alive, self-sufficient and yet a part of the world, more aware of truth, justice, harmony, goodness, and so on. Self-actualizing people are more likely to have peak experiences. In other words, these "peak experiences" or states of flow are the reflections of the realization of one's human potential and represent the height of personality development.<ref>{{cite book|last=Schacter|first=Daniel|title=Psychology Second Edition|year=2009|page=487}}</ref> | Beyond the routine of needs fulfillment, Maslow envisioned moments of extraordinary experience, known as "]", which are profound moments of love, understanding, happiness, or rapture, during which a person feels more whole, alive, self-sufficient and yet a part of the world, more aware of truth, justice, harmony, goodness, and so on. Self-actualizing people are more likely to have peak experiences. In other words, these "peak experiences" or states of flow are the reflections of the realization of one's human potential and represent the height of personality development.<ref>{{cite book|last=Schacter|first=Daniel|title=Psychology Second Edition|year=2009|page=487}}</ref> | ||

| In later writings, Maslow moved to a more inclusive model that allowed for, in addition to intense peak experiences, longer-lasting periods of serene |

In later writings, Maslow moved to a more inclusive model that allowed for, in addition to intense peak experiences, longer-lasting periods of serene being-cognition that he termed ].<ref>{{cite journal | last1 = Krippner | first1 = Stanley | year = 1972 | title = The plateau experience: A. H. Maslow and others | url = https://www.academia.edu/27103672 | journal = The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology | volume = 4 | issue = 2 | pages = 107–120 | access-date = October 5, 2018 | archive-date = March 9, 2022 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20220309035111/https://www.academia.edu/27103672 | url-status = live }}</ref><ref name="Gruel-2015-44-63">{{cite journal | id = {{ProQuest|1712319567}} | last1 = Gruel | first1 = Nicole | year = 2015 | title = The plateau experience: an exploration of its origins, characteristics, and potential | url = https://www.atpweb.org/jtparchive/trps-47-15-01-44.pdf | journal = The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology | volume = 47 | issue = 1 | pages = 44–63 | access-date = November 13, 2022 | archive-date = November 13, 2022 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20221113123101/https://www.atpweb.org/jtparchive/trps-47-15-01-44.pdf | url-status = live }}</ref> He borrowed this term from the Indian scientist and yoga practitioner, U. A. Asrani, with whom he corresponded.<ref>Gruel (2015), p. 50.</ref> Maslow stated that the shift from the peak to the plateau experience is related to the natural aging process, in which an individual has a shift in life values about what is actually important in one's life and what is not important. In spite of the personal significance with the plateau experience, Maslow was not able to conduct a comprehensive study of this phenomenon due to health problems that developed toward the end of his life.<ref name="Gruel-2015-44-63" /> | ||

| ===B-values=== | ===B-values=== | ||

| In studying accounts of peak experiences, Maslow identified a manner of thought he called " |

In studying accounts of peak experiences, Maslow identified a manner of thought he called "being-cognition" (or "B-cognition"), which is holistic and accepting, as opposed to the evaluative "deficiency-cognition" (or "D-cognition"), and values he called "Being-values".<ref>{{cite book|last=Maslow|first=Abraham|title=The Farther Reaches of Human Nature|year=1993|publisher=Arkana|isbn=978-0-14-019470-8|page=128}}</ref> He listed the B-values as: | ||

| * Truth: honesty; reality; simplicity; richness; oughtness; beauty; pure, clean and unadulterated; completeness; essentiality | * Truth: honesty; reality; simplicity; richness; oughtness; beauty; pure, clean and unadulterated; completeness; essentiality | ||

| * Goodness: rightness; desirability; oughtness; justice; benevolence; honesty | * Goodness: rightness; desirability; oughtness; justice; benevolence; honesty | ||

| Line 72: | Line 76: | ||

| * Uniqueness: idiosyncrasy; individuality; non-comparability; novelty | * Uniqueness: idiosyncrasy; individuality; non-comparability; novelty | ||

| * Perfection: necessity; just-right-ness; just-so-ness; inevitability; suitability; justice; completeness; "oughtness" | * Perfection: necessity; just-right-ness; just-so-ness; inevitability; suitability; justice; completeness; "oughtness" | ||

| * Completion: ending; finality; justice; "it's finished"; fulfillment; finis and telos; destiny; fate | * Completion: ending; finality; justice; "it's finished"; fulfillment; ''finis'' and ''telos''; destiny; fate | ||

| * Justice: fairness; orderliness; lawfulness; "oughtness" | * Justice: fairness; orderliness; lawfulness; "oughtness" | ||

| * Simplicity: honesty; essentiality; abstract, essential, skeletal structure | * Simplicity: honesty; essentiality; abstract, essential, skeletal structure | ||

| Line 80: | Line 84: | ||

| * Self-sufficiency: autonomy; independence; not-needing-other-than-itself-in-order-to-be-itself; self-determining; environment-transcendence; separateness; living by its own laws | * Self-sufficiency: autonomy; independence; not-needing-other-than-itself-in-order-to-be-itself; self-determining; environment-transcendence; separateness; living by its own laws | ||

| ===Hierarchy of |

===Hierarchy of needs=== | ||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| {{main|Maslow's hierarchy of needs}} | {{main|Maslow's hierarchy of needs}} | ||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| Maslow described human needs as ordered in a prepotent hierarchy—a pressing need would need to be mostly satisfied before someone would give their attention to the next highest need. None of his published works included a visual representation of the hierarchy. The pyramidal diagram illustrating the Maslow needs hierarchy may have been created by a psychology textbook publisher as an illustrative device. This now iconic pyramid frequently depicts the spectrum of human needs, both physical and psychological, as accompaniment to articles describing Maslow's needs theory and may give the impression that the |

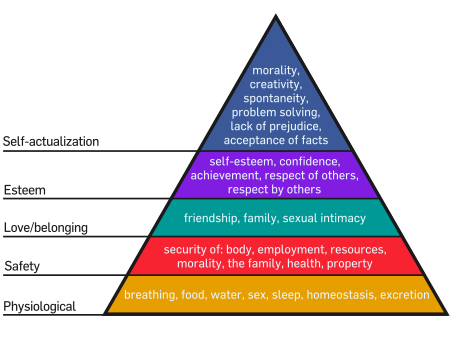

Maslow described human needs as ordered in a prepotent hierarchy—a pressing need would need to be mostly satisfied before someone would give their attention to the next highest need. None of his published works included a visual representation of the hierarchy. The pyramidal diagram illustrating the Maslow needs hierarchy may have been created by a psychology textbook publisher as an illustrative device. This now iconic pyramid frequently depicts the spectrum of human needs, both physical and psychological, as accompaniment to articles describing Maslow's needs theory and may give the impression that the hierarchy of needs is a fixed and rigid sequence of progression. Yet, starting with the first publication of his theory in 1943, Maslow described human needs as being relatively fluid—with many needs being present in a person simultaneously.<ref>{{Cite journal | last1 = Maslow | first1 = A. H. | title = A theory of human motivation | doi = 10.1037/h0054346 | journal = Psychological Review | volume = 50 | issue = 4 | pages = 370–396 | year = 1943 | citeseerx = 10.1.1.334.7586 | s2cid = 53326433 }}</ref> | ||

| The hierarchy of human needs model suggests that human needs will only be fulfilled one level at a time.<ref>Business Volume 1</ref> | The hierarchy of human needs model suggests that human needs will only be fulfilled one level at a time.<ref>Business Volume 1</ref> | ||

| According to Maslow's theory, when a human being ascends the levels of the hierarchy having fulfilled the needs in the hierarchy, one may eventually achieve self-actualization. Late in life, Maslow came to conclude that self-actualization was not an automatic outcome of satisfying the other human needs |

According to Maslow's theory, when a human being ascends the levels of the hierarchy having fulfilled the needs in the hierarchy, one may eventually achieve self-actualization. Late in life, Maslow came to conclude that self-actualization was not an automatic outcome of satisfying the other human needs.<ref>Frick, W. B. (1989). "Interview with Dr. Abraham Maslow". In ''Humanistic psychology: Conversations with Abraham Maslow, Gardner Murphy, Carl Rogers'' (pp. 19–50). Bristol, IN: Wyndham Hall Press. (Original work published 1971)</ref><ref>{{Cite journal | last1 = Maslow | first1 = A. H. | title = A Theory of Metamotivation: The Biological Rooting of the Value-Life | doi = 10.1177/002216786700700201 | journal = Journal of Humanistic Psychology | volume = 7 | issue = 2 | pages = 93–126 | year = 1967 | s2cid = 145703009 }}</ref> | ||

| Human needs as identified by Maslow: | Human needs as identified by Maslow: | ||

| * At the bottom of the hierarchy are the " |

* At the bottom of the hierarchy are the "basic needs or physiological needs" of a human being: food, water, sleep, sex, homeostasis, and excretion. | ||

| * The next level is " |

* The next level is "safety needs: security, order, and stability". These two steps are important to the physical survival of the person. Once individuals have basic nutrition, shelter and safety, they attempt to accomplish more. | ||

| * The third level of need is " |

* The third level of need is "love and belonging", which are psychological needs; when individuals have taken care of themselves physically, they are ready to share themselves with others, such as with family and friends. | ||

| * The fourth level is achieved when individuals feel comfortable with what they have accomplished. This is the " |

* The fourth level is achieved when individuals feel comfortable with what they have accomplished. This is the "esteem" level, the need to be competent and recognized, such as through status and level of success. | ||

| * Then there is the " |

* Then there is the "cognitive" level, where individuals intellectually stimulate themselves and explore. | ||

| * After that is the " |

* After that is the "aesthetic" level, which is the need for harmony, order and beauty.<ref>Carlson, N.R., et al. (2007). ''Psychology: The Science of Behaviour''. 4th Canadian ed. Toronto, ON: Pearson Education Canada.</ref> | ||

| * At the top of the pyramid, " |

* At the top of the pyramid, "need for self-actualization" occurs when individuals reach a state of harmony and understanding because they are engaged in achieving their full potential.<ref>''The Developing Person through the Life Span'', (1983) p. 44</ref> Once a person has reached the self-actualization state they focus on themselves and try to build their own image. They may look at this in terms of feelings such as self-confidence or by accomplishing a set goal.<ref name="Boeree"/> | ||

| The first four levels are known as '' |

The first four levels are known as ''deficit needs'' or ''D-needs''. This means that if there are not enough of one of those four needs, there will be a need to get it. Getting them brings a feeling of contentment. These needs alone are not motivating.<ref name="Boeree"/> | ||

| Maslow wrote that there are certain conditions that must be fulfilled in order for the basic needs to be satisfied. For example, freedom of speech, freedom to express oneself, and freedom to seek new information<ref>''A Theory of Human Motivation''</ref> are a few of the prerequisites. Any blockages of these freedoms could prevent the satisfaction of the basic needs. | Maslow wrote that there are certain conditions that must be fulfilled in order for the basic needs to be satisfied. For example, freedom of speech, freedom to express oneself, and freedom to seek new information<ref>''A Theory of Human Motivation''</ref> are a few of the prerequisites. Any blockages of these freedoms could prevent the satisfaction of the basic needs. | ||

| Maslow's |

Maslow's hierarchy is used in higher education for advising students and for student retention<ref>Brookman, David M. "Maslow's Hierarchy and Student Retention". ''NACADA Journal'', v.9 n.1 pp. 69–74. Spring 1989.</ref> as well as a key concept in student development.<ref>Villa, R., Thousand, J., Stainback, W. & Stainback, S. . Baltimore: Paul Brookes, 1992. {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121106011155/http://www.normemma.com/articles/armaslow.htm |date=November 6, 2012 }}</ref> Maslow's hierarchy has been subject to internet memes over the past few years, specifically looking at the modern integration of technology in people's lives and humorously suggesting that ] was among the most basic of human needs. | ||

| ===Self-actualization=== | ===Self-actualization=== | ||

| Maslow defined ] as achieving the fullest use of one's talents and interests—the need "to become everything that one is capable of becoming |

Maslow defined '']'' as achieving the fullest use of one's talents and interests—the need "to become everything that one is capable of becoming".<ref>Michael R. Hagerty, "Testing Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs: National Quality-of-Life Across Time", Social Indicators Research 46(xx), 1999, 250.</ref> As implied by its name, self-actualization is highly individualistic and reflects Maslow's premise that the self is "sovereign and inviolable" and entitled to "his or her own tastes, opinions, values, etc."<ref>{{cite journal | last1 = Aron | first1 = Adrianne | year = 1977 | title = Maslow's Other Child | journal = Journal of Humanistic Psychology | volume = 17 | issue = 2| page = 13 }}</ref> Indeed, some have characterized self-actualization as "healthy narcissism".<ref>{{cite journal | last1 = Pauchant | first1 = Thierry | last2 = Dumas | first2 = Collette A. | year = 1991 | title = Abraham Maslow and Heinz Kohut: A Comparison | journal = Journal of Humanistic Psychology | volume = 31 | issue = 2| page = 58 | doi = 10.1177/0022167891312005 | s2cid = 145440463 }}</ref> | ||

| ===Qualities of self-actualizing people=== | ===Qualities of self-actualizing people=== | ||

| Maslow realized that the self-actualizing individuals he studied had similar personality traits. Maslow selected individuals based on his subjective view of them as self-actualized people. Some of the people he studied included ], ], and ].<ref name="socialpsych">{{cite book |last1=Myers |first1=D. G. |title=Social psychology |publisher=McGraw-Hill |location=New York |pages=11–12 |edition=11th}}</ref> In his daily journal (1961–63) Maslow wrote: "Eupsychia club, heroes that I write for, my judges, the ones I want to please: Jefferson, Spinoza, Socrates, Aristotle, James, Bergson, Norman Thomas, Upton Sinclair (both heroes of my youth)."<ref>{{Cite book |last=Lowry |first=Richard H. |title=The Journals of A.H. Maslow Vol. 1 |publisher=Brooks/Cole Publishing Co. |year=1979 |location=Monterey, CA |page=232}}</ref> All were "reality centered", able to differentiate what was fraudulent from what was genuine. They were also "problem centered", meaning that they treated life's difficulties as problems that demanded solutions. These individuals also were comfortable being alone and had healthy personal relationships. They had only a few close friends and family rather than a large number of shallow relationships.<ref name="ship">{{cite web|url=http://webspace.ship.edu/cgboer/maslow.html|title=Abraham Maslow|author=C. George Boeree|access-date=October 8, 2009| archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20091024142938/http://webspace.ship.edu/cgboer/maslow.html| archive-date= October 24, 2009| url-status= live}}</ref> | |||

| Self-actualizing people tend to focus on problems outside themselves; have a clear sense of what is true and what is false; are spontaneous and creative; and are not bound too strictly by social conventions. | Self-actualizing people tend to focus on problems outside themselves; have a clear sense of what is true and what is false; are spontaneous and creative; and are not bound too strictly by social conventions. | ||

| Line 121: | Line 126: | ||

| * Beauty: rightness, form, aliveness, simplicity, richness, wholeness, perfection, completion, | * Beauty: rightness, form, aliveness, simplicity, richness, wholeness, perfection, completion, | ||

| * Wholeness: unity, integration, tendency to oneness, interconnectedness, simplicity, organization, structure, order, not dissociated, synergy | * Wholeness: unity, integration, tendency to oneness, interconnectedness, simplicity, organization, structure, order, not dissociated, synergy | ||

| * Dichotomy |

* Dichotomy-transcendence: acceptance, resolution, integration, polarities, opposites, contradictions | ||

| * Aliveness: process, not-deadness, spontaneity, self-regulation, full-functioning | * Aliveness: process, not-deadness, spontaneity, self-regulation, full-functioning | ||

| * Uniqueness: idiosyncrasy, individuality, non comparability, novelty | * Uniqueness: idiosyncrasy, individuality, non comparability, novelty | ||

| Line 127: | Line 132: | ||

| * Necessity: inevitability: it must be just that way, not changed in any slightest way | * Necessity: inevitability: it must be just that way, not changed in any slightest way | ||

| * Completion: ending, justice, fulfillment | * Completion: ending, justice, fulfillment | ||

| * Justice: fairness, suitability, |

* Justice: fairness, suitability, disinterestedness, non partiality, | ||

| * Order: lawfulness, rightness, perfectly arranged | * Order: lawfulness, rightness, perfectly arranged | ||

| * Simplicity: abstract, essential skeletal, bluntness | * Simplicity: abstract, essential skeletal, bluntness | ||

| Line 133: | Line 138: | ||

| * Effortlessness: ease; lack of strain, striving, or difficulty | * Effortlessness: ease; lack of strain, striving, or difficulty | ||

| * Playfulness: fun, joy, amusement | * Playfulness: fun, joy, amusement | ||

| * Self-sufficiency: autonomy, independence, self-determining.<ref name="Metaneeds">{{cite web|url=http://webspace.ship.edu/cgboer/maslow.html |title=Metaneeds and metapathologies |access-date=2010- |

* Self-sufficiency: autonomy, independence, self-determining.<ref name="Metaneeds">{{cite web |url=http://webspace.ship.edu/cgboer/maslow.html |title=Metaneeds and metapathologies |access-date=April 12, 2010 |archive-date=April 30, 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160430023433/http://webspace.ship.edu/cgboer/maslow.html |url-status=live }}</ref> | ||

| Maslow based his theory partially on his own assumptions about human potential and partially on his case studies of historical figures whom he believed to be self-actualized, including ] and ].<ref>Carlson, N. R. (19992000). Memory. Psychology: the science of behaviour ( |

Maslow based his theory partially on his own assumptions about human potential and partially on his case studies of historical figures whom he believed to be self-actualized, including ] and ].<ref>Carlson, N. R. (19992000). Memory. Psychology: the science of behaviour (Canadian ed., p. 461). Scarborough, Ont.: Allyn and Bacon Canada.</ref> Consequently, Maslow argued, the way in which essential needs are fulfilled is just as important as the needs themselves. Together, these define the human experience. To the extent a person finds cooperative social fulfillment, he establishes meaningful relationships with other people and the larger world. In other words, he establishes meaningful connections to an external reality—an essential component of self-actualization. In contrast, to the extent that vital needs find selfish and competitive fulfillment, a person acquires hostile emotions and limited external relationships—his awareness remains internal and limited. | ||

| ===Metamotivation=== | ===Metamotivation=== | ||

| Maslow used the term ] to describe self-actualized people who are driven by innate forces beyond their basic needs, so that they may explore and reach their full human potential.<ref>]</ref> Maslow's theory of motivation gave insight on individuals having the ability to be motivated by a calling, mission or life purpose. It is noted that metamotivation may also be connected to what Maslow called B-(being) creativity, which is a creativity that comes from being motivated by a higher stage of growth. Another type of creativity that was described by Maslow is known as D-(deficiency) creativity, which suggests that creativity results from an individual's need to fill a gap that is left by an unsatisfied primary need or the need for assurance and acceptance.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Raab |first1= |

Maslow used the term ] to describe self-actualized people who are driven by innate forces beyond their basic needs, so that they may explore and reach their full human potential.<ref>]</ref> Maslow's theory of motivation gave insight on individuals having the ability to be motivated by a calling, mission or life purpose. It is noted that metamotivation may also be connected to what Maslow called B-(being) creativity, which is a creativity that comes from being motivated by a higher stage of growth. Another type of creativity that was described by Maslow is known as D-(deficiency) creativity, which suggests that creativity results from an individual's need to fill a gap that is left by an unsatisfied primary need or the need for assurance and acceptance.<ref>{{cite journal |id={{ProQuest|1660149646}} |last1=Raab |first1=Diana |title=Creative Transcendence: Memoir Writing for Transformation and Empowerment |journal=Journal of Transpersonal Psychology |date=2014 |volume=46 |issue=2 |pages=187–207 |url=https://www.atpweb.org/jtparchive/trps-46-14-02-000.pdf#page=50 |access-date=November 13, 2022 |archive-date=November 13, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221113123119/https://www.atpweb.org/jtparchive/trps-46-14-02-000.pdf#page=50 |url-status=live }}</ref> | ||

| ===Methodology=== | ===Methodology=== | ||

| Maslow based his study on the writings of other psychologists, ], and people he knew who clearly met the standard of self-actualization.<ref>{{cite web|author=McLeod, S. A|year=2007|title= |

Maslow based his study on the writings of other psychologists, ], and people he knew who clearly met the standard of self-actualization.<ref>{{cite web|author=McLeod, S. A|year=2007|title=Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs|url=http://www.simplypsychology.org/maslow.html|publisher=Simplypsychology.org|access-date=January 24, 2020|archive-date=December 12, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201212073451/https://www.simplypsychology.org/maslow.html|url-status=live}}</ref> | ||

| Maslow used Einstein's writings and accomplishments to exemplify the characteristics of the self-actualized person. ] and ] work was also very influential to Maslow's models of self-actualization.<ref>{{Cite journal| |

Maslow used Einstein's writings and accomplishments to exemplify the characteristics of the self-actualized person. ] and ] work was also very influential to Maslow's models of self-actualization.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Francis|first1=N.H.|last2=Kritsonis|first2=W.A.|date=2006|title=A Brief Analysis of Abraham Maslow's Original Writing of Self-Actualizing People: A Study of Psychological Health|url=https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED501708|journal=National Journal of Publishing and Mentoring Doctoral Student Research|volume=3|page=2|access-date=May 5, 2021|archive-date=May 5, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210505205414/https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED501708|url-status=live}}</ref> In this case, from a quantitative-sciences perspective there are numerous problems with this particular approach, which has caused much criticism. First, it could be argued that biographical analysis as a method is extremely subjective as it is based entirely on the opinion of the researcher. Personal opinion is always prone to bias, which reduces the validity of any data obtained. Therefore, Maslow's operational definition of Self-actualization must not be uncritically accepted as quantitative fact.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Cummins|first=Robert|date=June 2016|title=Happiness Is the Right Metric to Measure Good Societal Functioning|journal=Society|volume=53|issue=3 |page=276|doi=10.1007/s12115-016-0011-y |s2cid=146991685 }}</ref> | ||

| ===Transpersonal psychology=== | ===Transpersonal psychology=== | ||

| During the 1960s Maslow founded with ], ], James Fadiman, Anthony Sutich, Miles Vich and Michael Murphy, the school of ]. Maslow had concluded that humanistic psychology was incapable of explaining all aspects of human experience. He identified various mystical, ecstatic, or spiritual states known as "]" as experiences beyond self-actualization. Maslow called these experiences "a fourth force in psychology", which he named transpersonal psychology. Transpersonal psychology was concerned with the "empirical, scientific study of, and responsible implementation of the finding relevant to, becoming, mystical, ecstatic, and spiritual states" (Olson & Hergenhahn, 2011).<ref name=":0" /> | During the 1960s Maslow founded with ], ], James Fadiman, Anthony Sutich, Miles Vich and Michael Murphy, the school of ]. Maslow had concluded that humanistic psychology was incapable of explaining all aspects of human experience. He identified various mystical, ecstatic, or spiritual states known as "]" as experiences beyond self-actualization. Maslow called these experiences "a fourth force in psychology", which he named transpersonal psychology. Transpersonal psychology was concerned with the "empirical, scientific study of, and responsible implementation of the finding relevant to, becoming, mystical, ecstatic, and spiritual states" (Olson & Hergenhahn, 2011).<ref name=":0" /> | ||

| In 1962 Maslow published a collection of papers on this theme<ref>{{cite book |last=Maslow |first=Abraham |author-link=Abraham Maslow |date=1962 |title=Notes Toward a Psychology of Being |url=https:// |

In 1962 Maslow published a collection of papers on this theme,<ref>{{cite book |last=Maslow |first=Abraham |author-link=Abraham Maslow |date=1962 |title=Notes Toward a Psychology of Being |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=JZJSnQEACAAJ |location=La Jolla, Calif. |publisher=Western Behavioral Sciences Institute |oclc=9801549 |access-date=March 21, 2023 |archive-date=October 17, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231017235011/https://books.google.com/books?id=JZJSnQEACAAJ |url-status=live }}</ref> which developed into his 1968 book ''Toward a Psychology of Being''.<ref name=":0">{{cite book|author1=Matthew H. Olson|author2=B. R. Hergenhahn|title=An Introduction to Theories of Personality|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ISJ6QgAACAAJ|year=2011|publisher=Prentice Hall/Pearson|isbn=978-0-205-79878-0}}</ref><ref name="Maslow2013">{{cite book|author=Abraham H. Maslow|title=Toward a Psychology of Being|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=jcKbDAAAQBAJ|date=2013|orig-date=first published 1968|publisher=Simon and Schuster|isbn=978-1-62793-274-5}}</ref> In this book Maslow stresses the importance of transpersonal psychology to human beings, writing: "without the transpersonal, we get sick, violent, and nihilistic, or else hopeless and apathetic" (Olson & Hergenhahn, 2011).<ref name=":0" /> Human beings, he came to believe, need something bigger than themselves that they are connected to in a naturalistic sense, but not in a religious sense: Maslow himself was an ]<ref name="Hamer2005">{{cite book|author=Dean H. Hamer|title=The God Gene: How Faith Is Hardwired into Our Genes|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=nKRphq7s7x0C&pg=PA19|year= 2005|publisher=Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group|isbn=978-0-307-27693-3|pages=19–}}</ref> and found it difficult to accept religious experience as valid unless placed in a ] framework.<ref name="Hoffman, E. 1999">{{cite book|author=Edward Hoffman|title=The Right to Be Human: A Biography of Abraham Maslow|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=USSePwAACAAJ|year=1994|publisher=Four Worlds Press|isbn=978-0-9637902-3-1}}</ref> In fact, Maslow's position on God and religion was quite complex. While he rejected organized religion and its beliefs, he wrote extensively on the human being's need for the sacred and spoke of God in more philosophical terms, as beauty, truth and goodness, or as a force or a principle.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.awaken.com/2013/01/abraham-maslow-and-spirituality/|title=Abraham Maslow and Spirituality {{!}} Awaken|website=www.awaken.com|date=January 28, 2013|access-date=March 15, 2019|archive-date=March 17, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190317235941/http://www.awaken.com/2013/01/abraham-maslow-and-spirituality/|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://oaks.nvg.org/maslow-rvl.html|title=Abraham Maslow on Religion, Values of Self-actualisers, and Peak Experiences – The Gold Scales|website=oaks.nvg.org|access-date=March 15, 2019|archive-date=March 10, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190310033058/http://oaks.nvg.org/maslow-rvl.html|url-status=live}}</ref> | ||

| Awareness of transpersonal psychology became widespread within psychology, and the ''Journal of Transpersonal Psychology'' was founded in 1969, a year after Abraham Maslow became the president of the American Psychological Association. In the United States, transpersonal psychology encouraged recognition for ] psychologies, philosophies, and religions, and promoted understanding of "higher states of consciousness", for instance through intense ].<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.thepositiveencourager.global/abraham-maslows-approach-to-doing-positive-work/|title=M is for Abraham Maslow: A Founder of Humanistic Psychology|date= |

Awareness of transpersonal psychology became widespread within psychology, and the ''Journal of Transpersonal Psychology'' was founded in 1969, a year after Abraham Maslow became the president of the American Psychological Association. In the United States, transpersonal psychology encouraged recognition for ] psychologies, philosophies, and religions, and promoted understanding of "higher states of consciousness", for instance through intense ].<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.thepositiveencourager.global/abraham-maslows-approach-to-doing-positive-work/|title=M is for Abraham Maslow: A Founder of Humanistic Psychology|date=December 19, 2014|newspaper=The Positive Encourager|access-date=December 13, 2016|archive-date=July 23, 2024|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240723031624/https://www.thepositiveencourager.global/abraham-maslows-approach-to-doing-positive-work/|url-status=live}}</ref> Transpersonal psychology has been applied in many areas, including ]. | ||

| ===Positive psychology=== | ===Positive psychology=== | ||

| Maslow called his work ].<ref>{{cite journal | |

Maslow called his work ].<ref name=Rennie2008>{{cite journal |last1=Rennie |first1=David L. |title=Two Thoughts on Abraham Maslow |journal=Journal of Humanistic Psychology |date=October 2008 |volume=48 |issue=4 |pages=445–448 |doi=10.1177/0022167808320537 |s2cid=145755075 }}</ref> Since 1968 his work has influenced the development of ], a transcultural, humanistic based psychodynamic psychotherapy method used in mental health and psychosomatic treatment founded by ].<ref>''Positive Psychotherapie'' by Nossrat Peseschkian. Fischer: 1977. ''Positive Psychotherapy'' by Nossrat Peseschkian. Springer: 1987.</ref> Since 1999 Maslow's work enjoyed a revival of interest and influence among leaders of the ] movement such as ]. This movement focuses only on a higher human nature.<ref>''Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification'' by Christopher Peterson, Martin E. P. Seligman. Oxford University Press: 2004 {{ISBN|0-19-516701-5}} p. 62</ref><ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=QqPiF1C7cy4C&q=maslow+seligmann&pg=PA62 |title=Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification |via=Google Books |access-date=October 21, 2012 |isbn=978-0-19-516701-6 |year=2004 |last1=Peterson |first1=Christopher |last2=Seligman |first2=Martin E. P. |publisher=American Psychological Association |archive-date=July 23, 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240723031609/https://books.google.com/books?id=QqPiF1C7cy4C&q=maslow+seligmann&pg=PA62#v=snippet&q=maslow%20seligmann&f=false |url-status=live }}</ref> | ||

| Positive psychology spends its research looking at the positive side of things and how they go right rather than the pessimistic side.<ref>Gilbert, D. (2006). ''Stumbling on happiness''. Toronto, Ontario: Random House.</ref> | Positive psychology spends its research looking at the positive side of things and how they go right rather than the pessimistic side.<ref>Gilbert, D. (2006). ''Stumbling on happiness''. Toronto, Ontario: Random House.</ref> | ||

| === Psychology of science === | === Psychology of science === | ||

| In 1966, Maslow published a pioneering work in the psychology of science, ''The Psychology of Science: A Reconnaissance'', the first book ever actually titled |

In 1966, Maslow published a pioneering work in the psychology of science, ''The Psychology of Science: A Reconnaissance'', the first book ever actually titled 'psychology of science'. In this book Maslow proposed a model of 'characterologically relative' science, which he characterized as an ardent opposition to the ''historically, philosophically, sociologically and psychologically naıve'' positivistic reluctance to see science ''relative to time, place, and local culture''.<ref>{{Cite book|title=The Psychology of Science: A Reconnaissance|last=Maslow|first=Abraham|publisher=Gateway Editions|year=1969|location=South Bend, Indiana|page=1}}</ref> | ||

| Maslow acknowledged that the book was greatly inspired by Thomas Kuhn's ''The Structure of Scientific Revolutions'' (1962), and it offers a psychological reading of Kuhn's famous distinction between "normal" and "revolutionary" science in the context of his own distinction between "safety" and "growth" science, put forward as part of a larger program for the psychology of science, outlined already in his 1954 ''magnum opus'' ''Motivation and Personality''. Not only that Maslow offered a psychological reading of Kuhn's categories of "normal" and "revolutionary" science as an aftermath of Kuhn's ''Structure'', but he also offered a strikingly similar dichotomous structure of science 16 years before the first edition of ''Structure'', in his nowadays little known 1946 paper "Means-Centering Versus Problem-Centering in Science" published in the journal ''Philosophy of Science''.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Kožnjak|first=Boris|date=2017|title=Kuhn Meets Maslow: The Psychology Behind Scientific Revolutions|journal=Journal for General Philosophy of Science|volume=48|issue=2|pages=257–287|doi=10.1007/s10838-016-9352-x|s2cid=148350025}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Maslow|first=Abraham|date=1946|title=Problem-centering vs. means-centering in science|journal=Philosophy of Science|volume=13 |issue=4 |pages=326–331 |doi=10.1086/286907|jstor=185213|s2cid=121235067}}</ref> | |||

| ===Maslow's hammer=== | ===Maslow's hammer=== | ||

| Abraham Maslow is also known for ], popularly phrased as "]" |

Abraham Maslow is also known for ], popularly phrased as "]" from his book ''The Psychology of Science'', published in 1966.<ref name=maslow66> | ||

| {{cite book | {{cite book | ||

| | title = The Psychology of Science | | title = The Psychology of Science | ||

| | author = Abraham H. Maslow | | author = Abraham H. Maslow | ||

| | year = 1966 | | year = 1966 | ||

| | isbn =978- |

| isbn =978-0-9760402-3-1| page = 15 | ||

| | publisher = Maurice Bassett | |||

| | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=3_40fK8PW6QC | | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=3_40fK8PW6QC | ||

| | access-date = |

| access-date = December 20, 2015 | ||

| }}</ref> | }}</ref> | ||

| === Maslow and Eugenics === | |||

| Although articulating his beliefs in a more positive manner than many of his contemporaries, Abraham Maslow was a eugenicist for his entire career.<ref name="Abraham Maslow was a Eugenicist">{{Cite web |title=Abraham Maslow was a Eugenicist |url=https://dr-s.medium.com/abraham-maslow-was-a-eugenicist-b3ba9a85f5ab}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=Seitz |first=Bill |date=2015-12-11 |title=(2004-10-28) Locke Maslow Eugenics |url=http://webseitz.fluxent.com/2004-10-28-LockeMaslowEugenics |access-date=2024-10-30 |website=WebSeitz}}</ref> Abraham Maslow began his career as a protege of ], a leading eugenicist.<ref name="philosophyforlife.org">{{Cite web |date=2021-03-31 |title=Abraham Maslow, empirical spirituality and the crisis of values |url=https://www.philosophyforlife.org/blog/abraham-maslow-empirical-spirituality-and-the-crisis-of-values |access-date=2024-10-30 |website=Philosophy for Life |language=en-US}}</ref> Under the influence of his mentor and financial backer Thorndike, Maslow expressed the belief that IQ tests were an accurate measure of one's genetic superiority or inferiority and that intelligence was a genetic, rather than acquired, trait.<ref name="philosophyforlife.org"/> Maslow expressed particular disdain for the nation of ], believing that the entire nation should be euthanized.<ref name="Abraham Maslow was a Eugenicist"/> Maslow also expressed critical views of ], believing mass vaccination to be interfering with natural selection by allowing "cripples" and "genetically inferior" people to live longer lives and reproduce.<ref name="philosophyforlife.org"/> Maslow's private journals in the late 1960s indicate that he took immense pleasure in seeing drug addicts die from overdoses, believing their deaths to be doing a public service to genetically superior individuals such as himself. He also criticized advances in agriculture for developing the ability to grow more food, believing that famine and starvation were beneficial to society and that those who died of hunger were doing a great service to superior humans.<ref name="Abraham Maslow was a Eugenicist"/> | |||

| Like Thorndike, Maslow expressed his belief that eugenics could be a religion of the future. To this end, he blended his earlier work with Thorndike with influences from ] and ] in order to found what he referred to as his own religion based upon "peak experiences" and the use of ]. Maslow referred to his religion as Eupsychianism.<ref name="Evans">{{Cite web |last=Evans |first=Jules |title='More evolved than you': evolutionary spirituality as a frame for psychedelic experience |url=https://www.ecstaticintegration.org/p/more-evolved-than-you-evolutionary |access-date=2024-10-30 |website=www.ecstaticintegration.org |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | doi=10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1103847 | doi-access=free | title='More evolved than you': Evolutionary spirituality as a cultural frame for psychedelic experiences | date=2023 | last1=Evans | first1=Jules | journal=Frontiers in Psychology | volume=14 | pmid=37051606 | pmc=10083267 }}</ref> He also expressed a belief in ] and that psychedelic drugs could help elite humans evolve, not just intellectually or spiritually, but into a new biological species, again showing his lifelong belief that acquired traits could be passed on genetically.<ref name="Evans"/> | |||

| Maslow's definition of "human" is key to understanding the contradiction between his more traditional psychological theories and his ardent support for eugenics. According to Maslow, not all people are humans. Drug addicts, mentally ill persons, people with low intelligence and those deemed "surplus" were not, according to Maslow, humans but rather "less-than-humans" or "cripple humans" whose material and intellectual needs were an impediment to the advancement of superior "aggridant humans".<ref name="philosophyforlife.org"/> Throughout his life, Maslow also expressed a fondness for Nietzche and his theory of the ], and Maslow often quoted and paraphrased Nietzche in relation to his theories of "aggridant humans" and "less-than-humans". | |||

| ==Criticism== | ==Criticism== | ||

| Maslow's ideas have been criticized for their lack of scientific rigor. He was criticized as too soft scientifically by American empiricists.<ref name="Hoffman, E. 1999"/> In 2006, author and former philosophy professor ] and practicing psychiatrist ] asserted that, due to lack of empirical support, Maslow's ideas have fallen out of fashion and are "no longer taken seriously in the world of academic psychology |

Maslow's ideas have been criticized for their lack of scientific rigor. He was criticized as too soft scientifically by American empiricists.<ref name="Hoffman, E. 1999"/> In 2006, author and former philosophy professor ] and practicing psychiatrist ] asserted that, due to lack of empirical support, Maslow's ideas have fallen out of fashion and are "no longer taken seriously in the world of academic psychology".<ref>], {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231017235009/https://books.google.com/books?id=sVT_i83KAhMC&q=maslow |date=October 17, 2023 }}</ref> Positive psychology spends much of its research looking for how things go right rather than the more pessimistic view point, how things go wrong.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Peterson|first= C. |year=2009|title= Positive psychology. |journal = Reclaiming Children and Youth|volume= 18|issue=2|pages= 3–7}}</ref> | ||

| Positive psychology spends much of its research looking for how things go right rather than the more pessimistic view point, how things go wrong.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Peterson|first= C. |year=2009|title= Positive psychology. |journal = Reclaiming Children and Youth|volume= 18|issue=2|pages= 3–7}}</ref> | |||

| The hierarchy of needs has furthermore been accused of having a cultural bias—mainly reflecting Western values and ideologies. From the perspective of many cultural psychologists, this concept is considered relative to each culture and society and cannot be universally applied.<ref>Keith E Rice,, ''Integrated Sociopsychology'', 9/12/12 {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150212143440/http://www.integratedsociopsychology.net/hierearchy_of_needs.html |date=February 12, 2015 }}</ref> However, according to the University of Illinois researchers Ed Diener and Louis Tay,<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Diener|first1=Ed|last2=Tay|first2=Louis|date=2011|title=Needs and subjective well-being around the world|journal=Journal of Personality and Social Psychology|volume=101 |issue=2|pages=354–365|doi=10.1037/a0023779|pmid=21688922}}</ref> who put Maslow's ideas to the test with data collected from 60,865 participants in 123 countries around the world over the period of five years (2005-2010), Maslow was essentially right in that there are universal human needs regardless of cultural differences, although the authors claim to have found certain departures from the order of their fulfillment Maslow described. In particular, while they found—clearly in accordance with Maslow—that people tend to achieve basic and safety needs before other needs, as well as that other "higher needs" tend to be fulfilled in a certain order, the order in which they are fulfilled apparently does not strongly influence their subjective well-being (SWB). As put by the authors of the study, humans thus | |||

| ⚫ | {{Blockquote|text=can derive 'happiness' from simultaneously working on a number of needs regardless of the fulfillment of other needs. This might be why people in impoverished nations, with only modest control over whether their basic needs are fulfilled, can nevertheless find a measure of well-being through social relationships and other psychological needs over which they have more control.|sign=|source=Diener & Tay (2011), p. 364}} | ||

| ⚫ | Maslow, however, would probably not be surprised by these findings, since he clearly and repeatedly emphasized that the need hierarchy is not a rigid fixed order as it is often presented: | ||

| ⚫ | {{ |

||

| ⚫ | {{Blockquote|text=We have spoken so far as if this hierarchy were a fixed order, but actually it is not nearly so rigid as we may have implied. It is true that most of the people with whom we have worked have seemed to have these basic needs in about the order that has been indicated. However, there have been a number of exceptions.|sign=|source=Maslow, 'Motivation and Personality' (1970), p. 51}} | ||

| ⚫ | Maslow, however, would not be surprised by these findings, since he clearly and repeatedly emphasized that the need hierarchy is not a rigid fixed order as it is often presented: | ||

| ⚫ | Maslow also regarded that the relationship between different human needs and behavior, being in fact often motivated simultaneously by multiple needs, is not a one-to-one correspondence, i.e., that "these needs must be understood not to be exclusive or single determiners of certain kinds of behavior".<ref>{{Cite book|title=Motivation and Personality|last=Maslow|first=Abraham|year=1970|page=55}}</ref> | ||

| ⚫ | {{ |

||

| ⚫ | Maslow's concept of self-actualizing people was united with ]'s developmental theory to the process of initiation in 1993.<ref>{{cite journal |url=https://www.academia.edu/663726 |title=A new approach to cognitive development: ontogenesis and the process of initiation |last=Kress |first=Oliver |access-date=December 20, 2015 |journal=Evolution and Cognition |volume=2 |year=1993 |pages=319–332 |publisher=] |archive-date=May 20, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230520093401/https://www.academia.edu/663726 |url-status=live }}</ref> Maslow's theory of self-actualization has been met with significant resistance. The theory itself is crucial to the humanistic branch of psychology and yet it is widely misunderstood. The concept behind self-actualization is widely misunderstood and subject to frequent scrutiny.<ref>{{cite journal |id={{ProQuest|1292330768}} |last1=Whitson |first1=Edward R |last2=Olczak |first2=Paul V.|title=Criticism and Polemics Surrounding the Self-Actualization Construct: An Evaluation |journal=Journal of Social Behavior and Personality |volume=6 |issue=5 |date=March 1, 1991 |page=75 }}</ref> | ||

| ⚫ | Maslow also regarded that the relationship between different human needs and |

||

| ⚫ | Maslow was criticized for noting too many exceptions to his theory. As he acknowledged these exceptions, he did not do much to account for them. Shortly prior to his death, one problem he tried to resolve was that there are people who have satisfied their deficiency needs but still do not become self-actualized. He never resolved this inconsistency within his theory.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Hergenhahn, Olson|first=B.R., Matthew H.|title=An Introduction to Theories of Personality|publisher=Pearson Prentice Hall|year=1990|isbn=0-13-194228-X|location=Upper Saddle River, New Jersey|page=495}}</ref> | ||

| ⚫ | Maslow's concept of self-actualizing people was united with Piaget's developmental theory to the process of initiation in 1993.<ref>{{cite journal|url=https://www.academia.edu/663726|title=A new approach to cognitive development: ontogenesis and the process of initiation|last=Kress|first=Oliver|access-date= |

||

| ===Bias=== | |||

| ⚫ | Maslow was criticized for noting too many exceptions to his theory. As he acknowledged these exceptions, he did not do much to account for them. Shortly prior to his death, one problem he tried to resolve was that there are people who have satisfied their deficiency needs but still do not become self-actualized. He never resolved this inconsistency within his theory.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Hergenhahn, Olson|first=B.R., Matthew H.|title=An Introduction to Theories of Personality|publisher=Pearson Prentice Hall|year=1990|isbn= |

||

| Social psychologist ] has pointed out Maslow's ], rooted in the choice to study individuals who lived out his own values. If he had studied other historical heroes, such as ], ], and ], his descriptions of self-actualization might have been significantly different.<ref name="socialpsych"/> | |||

| ==Legacy== | ==Legacy== | ||

| Later in life, Maslow was concerned with questions such as, "Why don't more people self-actualize if their basic needs are met? | Later in life, Maslow was concerned with questions such as, "Why don't more people self-actualize if their basic needs are met? | ||

| How can we humanistically understand the problem of evil?"<ref |

How can we humanistically understand the problem of evil?"<ref name=Rennie2008/> | ||

| In the spring of 1961, Maslow and Tony Sutich founded the ''Journal of Humanistic Psychology'', with Miles Vich as editor until 1971.<ref name="Greening">{{cite journal|author=Greening, Tom |year=2008 |title=Abraham Maslow: A Brief Reminiscence|journal= Journal of Humanistic Psychology|volume=48|issue=4 |pages=443–444 |doi=10.1177/0022167808320533 |s2cid=144591354 }}</ref> The journal printed its first issue in early 1961 and continues to publish academic papers.<ref name="Greening"/> | In the spring of 1961, Maslow and Tony Sutich founded the ''Journal of Humanistic Psychology'', with Miles Vich as editor until 1971.<ref name="Greening">{{cite journal|author=Greening, Tom |year=2008 |title=Abraham Maslow: A Brief Reminiscence|journal= Journal of Humanistic Psychology|volume=48|issue=4 |pages=443–444 |doi=10.1177/0022167808320533 |s2cid=144591354 }}</ref> The journal printed its first issue in early 1961 and continues to publish academic papers.<ref name="Greening"/> | ||

| Line 195: | Line 213: | ||

| Maslow attended the Association for Humanistic Psychology's founding meeting in 1963 where he declined nomination as its president, arguing that the new organization should develop an intellectual movement without a leader which resulted in useful strategy during the field's early years.<ref name="Greening"/> | Maslow attended the Association for Humanistic Psychology's founding meeting in 1963 where he declined nomination as its president, arguing that the new organization should develop an intellectual movement without a leader which resulted in useful strategy during the field's early years.<ref name="Greening"/> | ||

| In 1967, Maslow was named ] by the ].<ref name=AHA>{{cite web|title=Humanists of the Year|url=http://americanhumanist.org/AHA/Humanists_of_the_Year|work=American Humanist Association|access-date=14 November |

In 1967, Maslow was named ] by the ].<ref name=AHA>{{cite web|title=Humanists of the Year|url=http://americanhumanist.org/AHA/Humanists_of_the_Year|work=American Humanist Association|access-date=November 14, 2013|archive-date=November 28, 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151128162005/http://americanhumanist.org/aha/humanists_of_the_year}}</ref> | ||

| ==Writings== | ==Writings== | ||

| * |

* {{cite journal |last1=Maslow |first1=A. H. |title=A theory of human motivation. |journal=Psychological Review |date=July 1943 |volume=50 |issue=4 |pages=370–396 |doi=10.1037/h0054346 |s2cid=53326433 }} | ||

| * '']'' (1st edition: 1954, 2nd edition: 1970, 3rd edition 1987) | * '']'' (1st edition: 1954, 2nd edition: 1970, 3rd edition 1987) | ||

| * '']'', Columbus, Ohio: ], 1964. | * '']'', Columbus, Ohio: ], 1964. | ||

| * '']'', 1965; republished as '']'', 1998 | * '']'', 1965; republished as '']'', 1998 | ||

| * ''The Psychology of Science: A Reconnaissance'', New York: ], 1966; Chapel Hill: Maurice Bassett, 2002. | * ''The Psychology of Science: A Reconnaissance'', New York: ], 1966; Chapel Hill: Maurice Bassett, 2002. | ||

| * ''Toward a Psychology of Being'', (1st edition, 1962; 2nd edition, 1968) | * ''Toward a Psychology of Being'', (1st edition, 1962; 2nd edition, 1968; 3rd edition, 1999) | ||

| * ''The Farther Reaches of Human Nature'', 1971 | * ''The Farther Reaches of Human Nature'', 1971 | ||

| * ''Future Visions: The Unpublished Papers of Abraham Maslow'' by E. L. Hoffman (editor) 1996 | * ''Future Visions: The Unpublished Papers of Abraham Maslow'' by E. L. Hoffman (editor) 1996 | ||

| Line 213: | Line 231: | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| ⚫ | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| ⚫ | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| Line 220: | Line 240: | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| ⚫ | * ] | ||

| ⚫ | * ] | ||

| {{div col end}} | {{div col end}} | ||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| {{Reflist|30em}} | {{Reflist|30em}} | ||

| ==Sources== | |||

| {{refbegin}} | {{refbegin}} | ||

| * {{cite book |title=The Developing Person through the Life Span |last=Berger |first=Kathleen Stassen |year=1983 |ref=Berger}} | * {{cite book |title=The Developing Person through the Life Span |last=Berger |first=Kathleen Stassen |year=1983 |ref=Berger}} | ||

| * {{cite book |title=The Third Force: The Psychology of Abraham Maslow |last=Goble |first=F. |publisher=Maurice Bassett Publishing |year=1970 |location=Richmond, CA |ref=Goble}} | * {{cite book |title=The Third Force: The Psychology of Abraham Maslow |last=Goble |first=F. |publisher=Maurice Bassett Publishing |year=1970 |location=Richmond, CA |ref=Goble}} | ||

| * {{cite journal |last1=Goud |

* {{cite journal |last1=Goud |first1=Nelson |title=Abraham Maslow: A Personal Statement |journal=Journal of Humanistic Psychology |date=October 2008 |volume=48 |issue=4 |pages=448–451 |doi=10.1177/0022167808320535 |s2cid=143617210 }} | ||

| * {{cite book |title=The Right to be Human: A Biography of Abraham Maslow |url=https://archive.org/details/righttobehuman00edwa |url-access=registration |last=Hoffman |first=Edward |publisher=St. Martin's Press |year=1988 |location=New York |ref=Hoffman}} | * {{cite book |title=The Right to be Human: A Biography of Abraham Maslow |url=https://archive.org/details/righttobehuman00edwa |url-access=registration |last=Hoffman |first=Edward |publisher=St. Martin's Press |year=1988 |location=New York |isbn=978-0-87477-461-0 |ref=Hoffman}} | ||

| * {{Citation | last =Hoffman | first =E. | title =Abraham Maslow: A Brief Reminiscence. In: Journal of Humanistic Psychology Fall 2008 vol. 48 no. 4 443-444 | year =1999 | place =New York | publisher =McGraw-Hill}} | * {{Citation | last =Hoffman | first =E. | title =Abraham Maslow: A Brief Reminiscence. In: Journal of Humanistic Psychology Fall 2008 vol. 48 no. 4 443-444 | year =1999 | place =New York | publisher =McGraw-Hill}} | ||

| * {{cite journal |last=Rennie | first =David |year=2008 |title=Two Thoughts on Abraham Maslow. | journal =Journal of Humanistic Psychology | volume =48 | issue =4 | pages =445–448 |doi=10.1177/0022167808320537| s2cid =145755075 }} | |||

| * {{cite book |title=One Nation Under Therapy: How the Helping Culture is Eroding Self-reliance |last2=Satel |first2=Sally |publisher=MacMillan |year=2006 |isbn=978-0-312-30444-7 |ref=Sommers|last1=Sommers |first1=Christina Hoff }} | * {{cite book |title=One Nation Under Therapy: How the Helping Culture is Eroding Self-reliance |last2=Satel |first2=Sally |publisher=MacMillan |year=2006 |isbn=978-0-312-30444-7 |ref=Sommers|last1=Sommers |first1=Christina Hoff }} | ||

| {{refend}} | {{refend}} | ||

| Line 246: | Line 265: | ||

| * DeCarvalho, Roy Jose (1991) ''The Founders of Humanistic Psychology''. Praeger Publishers{{ISBN?}} | * DeCarvalho, Roy Jose (1991) ''The Founders of Humanistic Psychology''. Praeger Publishers{{ISBN?}} | ||

| * Grogan, Jessica (2012) ''Encountering America: Humanistic Psychology, Sixties Culture, and the Shaping of the Modern Self''. Harper Perennial {{ISBN?}} | * Grogan, Jessica (2012) ''Encountering America: Humanistic Psychology, Sixties Culture, and the Shaping of the Modern Self''. Harper Perennial {{ISBN?}} | ||

| * Hoffman, Edward (1999) ''The Right to Be Human''. McGraw-Hill |

* Hoffman, Edward (1999) ''The Right to Be Human''. McGraw-Hill {{ISBN|0-07-134267-2}} | ||

| * {{cite journal | last1 = Wahba | first1 = M.A. | last2 = Bridwell | first2 = L. G. | year = 1976 | title = Maslow Reconsidered: A Review of Research on the Need Hierarchy Theory | journal = Organizational Behavior and Human Performance | volume = 15 | issue = 2| pages = 212–240 | doi=10.1016/0030-5073(76)90038-6}} | * {{cite journal | last1 = Wahba | first1 = M.A. | last2 = Bridwell | first2 = L. G. | year = 1976 | title = Maslow Reconsidered: A Review of Research on the Need Hierarchy Theory | journal = Organizational Behavior and Human Performance | volume = 15 | issue = 2| pages = 212–240 | doi=10.1016/0030-5073(76)90038-6}} | ||

| * Wilson, Colin (1972) ''New Pathways in Psychology: Maslow and the post-Freudian revolution''. London: Victor Gollancz {{ISBN|0-575-01355-9}} | * Wilson, Colin (1972) ''New Pathways in Psychology: Maslow and the post-Freudian revolution''. London: Victor Gollancz {{ISBN|0-575-01355-9}} | ||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| {{sister project links|d=Q23357|c=Category:Abraham Maslow|b=no|v=no|voy=no|m=no|mw=no|wikt=no|species=no|n=no|s=no}} | |||

| {{wikiquote}} | |||

| {{Commons category|Abraham Maslow}} | |||

| * | * | ||

| * | |||

| * adapted from the Editor's Introduction to ''Toward a Psychology of Being'' (3rd ed.) | * adapted from the Editor's Introduction to ''Toward a Psychology of Being'' (3rd ed.) | ||

| * | * | ||

| Line 259: | Line 278: | ||

| * {{Librivox author |id=3653}} | * {{Librivox author |id=3653}} | ||

| * | * | ||

| * |

* {{YouTube|id=sfmo04EZP3o|title=Being Abraham Maslow}}. Rare documentary about Abraham Maslow in a conversation with Warren Bennis of the University of Cincinnati from 1968. | ||

| * | * | ||

| Line 269: | Line 288: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| Line 281: | Line 300: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| Line 292: | Line 311: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 16:53, 7 January 2025

American psychologist (1908–1970)

| Abraham Maslow | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | April 1, 1908 (1908-04) Brooklyn, New York City, U.S. |

| Died | June 8, 1970(1970-06-08) (aged 62) Menlo Park, California, U.S. |

| Education | City College of New York Cornell University University of Wisconsin |

| Known for | Maslow's hierarchy of needs |

| Spouse |

Bertha Goodman Maslow

(m. 1928) |

| Children | 2 |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Psychology |

| Institutions | |

| Doctoral advisor | Harry Harlow |