| Revision as of 10:53, 13 December 2021 editJumpingJimmySingh (talk | contribs)170 edits Undid revision 1060084030 by Cordless Larry (talk)Tags: Undo Reverted nowiki added← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 13:01, 21 October 2024 edit undoYadsalohcin (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users14,674 edits tidy refs | ||

| (89 intermediate revisions by 30 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description| |

{{short description|Indian nationalist organisation}} | ||

| {{for|the think tank that initially used the same name|1928 Institute}} | |||

| The '''India League''' was an England-based organisation that campaigned for the full independence and self-governance of India.<ref name=":0">{{Cite web|last=Nasta|first=Susheila|title=The India League|publisher=Open University|url=https://www.open.ac.uk/researchprojects/makingbritain/content/india-league}}</ref> The League, one of the most successful organisations in Britain to fight colonialism, was established in 1928 by ].<ref name=":1">{{Cite book|last=Ramesh|first=Jairam|url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1138886625|title=A chequered brilliance : the many lives of V.K. Krishna Menon|date=2019|isbn=978-0-670-09232-1|location=Haryana, India|oclc=1138886625}}</ref><ref name=":2">{{Cite book|url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/802321049|title=India in Britain : South Asian networks and connections, 1858-1950|date=2013|publisher=Palgrave Macmillan|others=Susheila Nasta|isbn=978-0-230-39271-7|location=New York|oclc=802321049}}</ref> The India League <nowiki>''</nowiki>rebranded due to its work with the ]<nowiki>''</nowiki> and is now called the 1928 Institute.<ref name=":8" /> | |||

| ] | |||

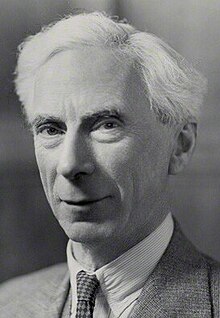

| ], president of the India League, frequent patron, host, and intellectual cover for events]] | |||

| The '''India League''' was an England-based organisation established by ] in 1928.<ref name=":1">{{Cite book |last=Ramesh|first=Jairam |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1138886625|title=A chequered brilliance : the many lives of V.K. Krishna Menon|date=2019|isbn=978-0-670-09232-1 |publisher=Viking by Penguin Random House India |location=Haryana, India |oclc=1138886625}}</ref><ref name=":2">{{Cite book |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/802321049 |title=India in Britain : South Asian networks and connections, 1858-1950 |date=2013 |publisher=Palgrave Macmillan |first=Susheila |last=Nasta |isbn=978-0-230-39271-7 |location=New York |oclc=802321049}}</ref> It campaigned for the full independence and self-governance of ].<ref name=":0">{{Cite web|last=Nasta|first=Susheila|author-link=Susheila Nasta|title=The India League|publisher=Open University|url=https://www.open.ac.uk/researchprojects/makingbritain/content/india-league}}</ref> It has been described as "the principal organisation promoting Indian nationalism in pre-war Britain".<ref>{{cite journal|last=McGarr|first=Paul M.|title="India's Rasputin"? V. K. Krishna Menon and Anglo–American Misperceptions of Indian Foreign Policymaking, 1947–1964|journal=Diplomacy & Statecraft|volume=22|issue=2|year=2011|doi=10.1080/09592296.2011.576536|pages=239–260|s2cid=154740401 |doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| ==History== | ==History== | ||

| The India League emerged from the Commonwealth of India League, which was established in 1922 and itself emerged from the Home Rule for India League, established in 1916. When Menon became joint secretary of the Commonwealth of India League, he rejected its previous objective of ] status for India and instead set the goal of full independence. During the 1930s, the organisation expanded and established branches in cities across Britain.<ref name=":0"/> | The India League emerged from the Commonwealth of India League, which was established in 1922 and itself emerged from the Home Rule for India League, established in 1916. When Menon became joint secretary of the Commonwealth of India League, he rejected its previous objective of ] status for India and instead set the goal of full independence. During the 1930s, the organisation expanded and established branches in cities across Britain.<ref name=":0"/> | ||

| In 1930s, Menon along with other contributors had created a 554-page report on the situation in India. The report was banned in India.<ref name="Rana 2022">{{cite book | last=Rana | first=K.S. | title=Churchill and India: Manipulation or Betrayal? | publisher=Taylor & Francis | year=2022 |page=65| isbn=978-1-000-72827-9 | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=iGWFEAAAQBAJ&pg=PT65}}</ref> In 1931, ] praised the efforts of the Indian League for its "hurricane propaganda on the danger to world peace of a rebellious India in bondage".<ref name="Kiran Mahadevan 2000 p. ">{{cite book | last=Kiran | first=R.N. | last2=Mahadevan | first2=K. | title=V.K. Krishna Menon, Man of the Century | publisher=B.R. Publishing Corporation | year=2000 | isbn=978-81-7646-145-0 | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=GSJuAAAAMAAJ| pages=5–6}}</ref> | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| Members of the League were largely drawn from the British elite, such as ], ], ], ], ], ], and ], although a branch was established in the East End of London in the early 1940s, in order to attract more supporters from the South Asian community there.<ref name=":0"/> According to historian Nicholas Owen, British audiences were reluctant to believe accounts of colonial repression and social conditions in India given by Indians, and so the League sent a British delegation to India to validate its arguments, resulting in the publication in 1933 of ''The Condition of India''.<ref>{{cite journal|title="Facts Are Sacred": The ''Manchester Guardian'' and Colonial Violence, 1930–1932|first=Nicholas|last=Owen|journal=The Journal of Modern History|volume=84|issue=3|year=2012|pages=643–678|doi=10.1086/666052|s2cid=147411268 }}</ref> | |||

| In 1944, Menon reported that total membership of the league stood approximately at 1,400 members, and that 70 trade and 118 unions and other organisations are affiliated with the league.<ref name="Volckmann 1963 p. ">{{cite book | last=Volckmann | first=R.W. | title=Krishna Menon: a Political Biography | publisher=University of California | year=1963 | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=tVJKAQAAMAAJ | page=26}}</ref> | |||

| ⚫ | The organisation continued to operate after India's independence in 1947 and while it focused mainly on India, "the League was internationalist in its outlook throughout, perceiving India's struggle for freedom as part of a larger struggle against imperialism and capitalism".<ref name=":0"/> Following Indian independence, the organisation focused on fostering relations between the UK and India and supporting Indian immigrants in the UK. It held regular meetings at the ]. Latterly, its public presence faded.<ref name=Sherwood>{{Cite news|last=Sherwood|first=Harriet|date=9 August 2020|title=From resisting the Raj to helping with Covid: India League reborn for the 21st century|work=The Guardian|url=https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/aug/09/from-resisting-the-raj-to-helping-with-covid-india-league-reborn-for-the-21st-century|accessdate=20 March 2023}}</ref> | ||

| In 1947 it was reported that the minimum subscription to the India League was five shillings. Branches could be established by groups of five or more people, subject to the approval of the League's executive committee. Branches were required to pay £2 6 shillings per year to the executive committee.<ref>{{cite journal|title=Associations in foreign countries interested in India: The India League, London|journal=India Quarterly|volume=3|issue=1|page=86|year=1947|jstor=45067427}}</ref> | |||

| ] - early friend and patron of the India League]] | |||

| == |

== Other Members == | ||

| In 2020, a think tank called the 1928 Institute,<ref name=":8">{{Cite news|last=Pearce|first=Vanessa|date=2021|title=Indian activists who helped change the face of modern Britain|work=]|url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-coventry-warwickshire-58627849}}</ref><ref name=Sherwood>{{Cite news|last=Sherwood|first=Harriet|date=2020|title=From resisting the Raj to helping with Covid: India League reborn for the 21st century|work=]|url=https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/aug/09/from-resisting-the-raj-to-helping-with-covid-india-league-reborn-for-the-21st-century}}</ref><ref name=":3">{{Cite web|last=The 1928 Institute|title=The India League Story|url=https://www.1928institute.org/the-india-league-story|url-status=live}}</ref> with links with academics at the ],<ref name=Giordano>{{Cite news|last=Giordano|first=Chiara|date=2021|title=Just over half of British Indians would get Covid vaccine, survey shows|work=]|url=https://www.independent.co.uk/news/health/coronavirus-vaccine-survey-british-indians-b1790128.html}}</ref><ref name=":4">{{Cite news|date=2021|title=Just over half of British Indians would take COVID vaccine|publisher=University of Oxford |url=https://www.medsci.ox.ac.uk/news/just-over-half-of-british-indians-would-take-covid-vaccine}}</ref><ref name=":8" /> was established, "to continue the work of the original India League".<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.1928institute.org/the-india-league-story|title=Our Story|publisher=1928 Institute|accessdate=11 December 2021}}</ref> The 1928 Institute has run an online survey of British Indians, collecting socioeconomic data as well as information on political opinions, media representation of the community, religious identity, experience of racism and domestic violence, and the COVID-19 pandemic.<ref name=Sherwood/> In January 2021, the Institute announced that its research showed that 56 per cent of British Indians would take a COVID-19 vaccine, compared to 79 per cent of the overall population.<ref name=":4"/> One of the Institute's co-founders stated that "It seems that the Indian/south Asian population in general have been really falling prey to through things like WhatsApp forwards and fake news. And a lot of it seems to be directed at fertility, which is, I think, very interesting because there is no evidence to suggest that the vaccine causes fertility issues".<ref name=Giordano/> | |||

| * ] | |||

| Writing for ''Byline Times'', ] wrote that "while the India League saw the struggle in India as part of a larger struggle against imperialism and racism – and included such socialists and anti-imperialists as Harold Laski, Bertrand Russell and Fenner Brockway – the 1928 Institute's list of 'notable members' includes a corporate billionaire who admires Modi. Even the Prince of Udaipur, scion of one of India's most wealthy oppressor caste Rajput dynasties, is on board". The organisation responsed by stating that it had "diverse members with no influence over the organisation".<ref>{{cite news|url=https://bylinetimes.com/2021/12/09/the-new-strategies-of-hindu-supremacists-in-britain/|title=The New Strategies of Hindu Supremacists in Britain|first=Amrit|last=Wilson|work=Byline Times|date=9 December 2021|accessdate=11 December 2021}}</ref> | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| {{ |

{{Reflist}} | ||

| ==Further reading== | ==Further reading== | ||

| * | |||

| * {{cite journal|last=McGarr|first=Paul M.|title='A Serious Menace to Security': British Intelligence, V. K. Krishna Menon and the Indian High Commission in London, 1947–52|journal=The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History|volume=38|issue=3|pages=441–469|year=2010|doi=10.1080/03086534.2010.503397}} | |||

| * {{cite journal|last= |

* {{cite journal |last=McGarr|first=Paul M. |title='A Serious Menace to Security': British Intelligence, V. K. Krishna Menon and the Indian High Commission in London, 1947–52|journal=The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History|volume=38|issue=3|pages=441–469|year=2010|doi=10.1080/03086534.2010.503397|s2cid=159690638 |url=https://nottingham-repository.worktribe.com/file/1012866/1/McGarrmenace.pdf }} | ||

| * {{cite journal |author=Meston |title=Condition of India: Being the Report of the Delegation sent to India by the India League Delegation |location=London |publisher=Essential News |work=International Affairs |volume=13 |issue=5, September-October 1934 |page=711–712 |url=https://doi.org/10.2307/2602910 |date=1 September 1934}} | |||

| ⚫ | * {{cite journal|last=Sadasivan|first=C.|title=The Nehru‐Menon partnership|journal=The Round Table|volume=76|issue=301| pages=59–63|year=1987|doi=10.1080/00358538708453792}} | ||

| * {{cite journal |last=Moscovitch|first=Brant |title='Against the Biggest Buccaneering Enterprise in Living History': Krishna Menon and the Colonial Response to International Crisis|journal=South Asian Review|volume=41|issue=3–4|pages=243–254|year=2020|doi=10.1080/02759527.2020.1798196|s2cid=225418610 }} | |||

| ⚫ | * {{cite journal |last=Sadasivan|first=C. |title=The Nehru‐Menon partnership|journal=The Round Table|volume=76|issue=301| pages=59–63|year=1987|doi=10.1080/00358538708453792}} | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 13:01, 21 October 2024

Indian nationalist organisation For the think tank that initially used the same name, see 1928 Institute.

The India League was an England-based organisation established by Krishna Menon in 1928. It campaigned for the full independence and self-governance of British India. It has been described as "the principal organisation promoting Indian nationalism in pre-war Britain".

History

The India League emerged from the Commonwealth of India League, which was established in 1922 and itself emerged from the Home Rule for India League, established in 1916. When Menon became joint secretary of the Commonwealth of India League, he rejected its previous objective of dominion status for India and instead set the goal of full independence. During the 1930s, the organisation expanded and established branches in cities across Britain.

In 1930s, Menon along with other contributors had created a 554-page report on the situation in India. The report was banned in India. In 1931, Mahatma Gandhi praised the efforts of the Indian League for its "hurricane propaganda on the danger to world peace of a rebellious India in bondage".

Members of the League were largely drawn from the British elite, such as Edwina Mountbatten, Countess Mountbatten of Burma, Bertrand Russell, Harold Laski, Sir Stafford Cripps, Henry Brailsford, Leonard Matters, and Michael Foot, although a branch was established in the East End of London in the early 1940s, in order to attract more supporters from the South Asian community there. According to historian Nicholas Owen, British audiences were reluctant to believe accounts of colonial repression and social conditions in India given by Indians, and so the League sent a British delegation to India to validate its arguments, resulting in the publication in 1933 of The Condition of India.

In 1944, Menon reported that total membership of the league stood approximately at 1,400 members, and that 70 trade and 118 unions and other organisations are affiliated with the league.

The organisation continued to operate after India's independence in 1947 and while it focused mainly on India, "the League was internationalist in its outlook throughout, perceiving India's struggle for freedom as part of a larger struggle against imperialism and capitalism". Following Indian independence, the organisation focused on fostering relations between the UK and India and supporting Indian immigrants in the UK. It held regular meetings at the India Club, London. Latterly, its public presence faded.

In 1947 it was reported that the minimum subscription to the India League was five shillings. Branches could be established by groups of five or more people, subject to the approval of the League's executive committee. Branches were required to pay £2 6 shillings per year to the executive committee.

Other Members

- Aneurin Bevan

- Fenner Brockway

- H.N. Brailsford

- Leonard Matters

- Ellen Wilkinson

- Monica Whately

- Bhicoo Batlivala

- Shyamji Krishna Varma

- Bhikaiji Cama

- Harold Laski

References

- Ramesh, Jairam (2019). A chequered brilliance : the many lives of V.K. Krishna Menon. Haryana, India: Viking by Penguin Random House India. ISBN 978-0-670-09232-1. OCLC 1138886625.

- Nasta, Susheila (2013). India in Britain : South Asian networks and connections, 1858-1950. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-39271-7. OCLC 802321049.

- ^ Nasta, Susheila. "The India League". Open University.

- McGarr, Paul M. (2011). ""India's Rasputin"? V. K. Krishna Menon and Anglo–American Misperceptions of Indian Foreign Policymaking, 1947–1964". Diplomacy & Statecraft. 22 (2): 239–260. doi:10.1080/09592296.2011.576536. S2CID 154740401.

- Rana, K.S. (2022). Churchill and India: Manipulation or Betrayal?. Taylor & Francis. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-000-72827-9.

- Kiran, R.N.; Mahadevan, K. (2000). V.K. Krishna Menon, Man of the Century. B.R. Publishing Corporation. pp. 5–6. ISBN 978-81-7646-145-0.

- Owen, Nicholas (2012). ""Facts Are Sacred": The Manchester Guardian and Colonial Violence, 1930–1932". The Journal of Modern History. 84 (3): 643–678. doi:10.1086/666052. S2CID 147411268.

- Volckmann, R.W. (1963). Krishna Menon: a Political Biography. University of California. p. 26.

- Sherwood, Harriet (9 August 2020). "From resisting the Raj to helping with Covid: India League reborn for the 21st century". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 March 2023.

- "Associations in foreign countries interested in India: The India League, London". India Quarterly. 3 (1): 86. 1947. JSTOR 45067427.

Further reading

- Barot, Rohit, Bristol and the Indian Independence Movement (Bristol Historical Association pamphlets, no. 70, 1988), 19 pp.

- McGarr, Paul M. (2010). "'A Serious Menace to Security': British Intelligence, V. K. Krishna Menon and the Indian High Commission in London, 1947–52" (PDF). The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. 38 (3): 441–469. doi:10.1080/03086534.2010.503397. S2CID 159690638.

- Meston (1 September 1934). "Condition of India: Being the Report of the Delegation sent to India by the India League Delegation". International Affairs. 13 (5, September-October 1934). London: Essential News: 711–712.

- Moscovitch, Brant (2020). "'Against the Biggest Buccaneering Enterprise in Living History': Krishna Menon and the Colonial Response to International Crisis". South Asian Review. 41 (3–4): 243–254. doi:10.1080/02759527.2020.1798196. S2CID 225418610.

- Sadasivan, C. (1987). "The Nehru‐Menon partnership". The Round Table. 76 (301): 59–63. doi:10.1080/00358538708453792.