| Revision as of 20:38, 19 February 2007 editLysy (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers21,125 edits →See also: removed irrelevant link, again← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 06:57, 25 November 2024 edit undoKelisi (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users58,452 editsNo edit summary | ||

| (563 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|1941–1944 Nazi murders in Vilnius, Lithuania}} | |||

| {{The Holocaust}} | |||

| {{Infobox holocaust event | |||

| | name = Ponary massacre | |||

| | image = File:Ponary massacre July 1941.jpg | |||

| | image_size = 300px | |||

| | caption = One of six Ponary murder pits in which victims were shot (July 1941). Note the ramp leading down and the group of men forced to wear hoods. | |||

| | AKA = {{langx|pl|zbrodnia w Ponarach}} | |||

| | location = ] (Ponary), ] (Wilno), ] | |||

| | coordinates = {{coord|54.6264|N|25.1612|E|region:LT-VL_type:event_source:GNS-enwiki|display=title,inline}} | |||

| | date = July 1941 – August 1944 | |||

| | incident_type = Shootings by ] and ] weapons, | |||

| ] | |||

| | perpetrators = ] ] <br /> ] | |||

| | ghetto = ] | |||

| | victims = ~100,000 in total (]: 70,000; <br /> Poles: From 1,000{{sfn|Piotrowski|1998|p=167}} to 2,000{{sfn|Tomkiewicz|2008|p=216}}<br /> Soviets/Russians: 8,000) | |||

| | documentation = ] | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Campaingbox Polish-Lithuanian ethnic Conflict}} | |||

| {{Jewish Lithuanian history |expanded=The Holocaust}} | |||

| The '''Ponary massacre''' ({{langx|pl|zbrodnia w Ponarach}}), or the '''Paneriai massacre''' ({{langx|lt|Panerių žudynės}}), was the ] of up to 100,000 people, mostly Jews, Poles, and Russians, by ] '']'' and '']'' and the Lithuanian '']'' killing squads,<ref name="Sak_Ard"/><ref name="IPN-Ponary"> | |||

| The '''Ponary massacre''' (or '''Paneriai massacre''') was the sequence of events that took place between July ] and August ] near the railway station of ] ({{lang-pl|Ponary}}), now a suburb of ] (Wilno), which became the ] site of approximately 100,000 victims, the vast majority of them ] and ] many from nearby metropolis of Vilnius.<ref name="Sak_Ard">], ], ''Ponary Diary, 1941–1943: A Bystander's Account of a Mass Murder'', Yale University Press, 2005, ISBN 0300108532, .</ref><ref name="Piotrowski_168">], ''Poland's Holocaust'', McFarland & Company, 1997, ISBN 0-7864-0371-3, .</ref><ref name="IPN-Ponary">{{pl icon}} (Investigation of mass murders of Poles in the years 1941–1944 in Ponary near Wilno by functionaries of German police and Lithuanian collaborating police). ] documents from 2003 on the ongoing investigation]. Last accessed on 10 February 2007.</ref> The executions were carried out by German units of ] and ] with help from local ],<ref name="IPN-Ponary"/><ref name="WSP-Ponary">{{pl icon}} Czesław Michalski, (Ponary — the Golgoth of Wilno Region). ''Konspekt'' nº 5, Winter 2000–2001, a publication of the ]. Last accessed on 10 February 2007.</ref><ref name="Bubnys">{{lt icon}} {{cite book | author =] | coauthors = | title =Vokiečių ir lietuvių saugumo policija (1941–1944) (German and Lithuanian security police: 1941–1944)| year =2004 | publisher =Lietuvos gyventojų genocido ir rezistencijos tyrimo centras | location =Vilnius | url =http://www.genocid.lt/Leidyba/1/arunas1.htm | accessdate =2006-06-09 }}</ref> composed primarily of ], although a few ] and ] | |||

| {{cite journal | |||

| <ref name=McQueen>{{cite web |url=http://www.ushmm.org/research/center/publications/occasional/2005-07-03/paper.pdf |title=Lithuanian Collaboration in the “Final Solution”: Motivations and Case Studies |accessdate=2007-02-19 |last=MacQueen |first=Michael |year=2004 |format=pdf |work=Lithuania and the Jews The Holocaust Chapter |publisher=UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM |pages=55 |language=English quote=When questioned by Polish authorities about what had motivated him to spend more than two months as a killer assigned to the execution squad at Paneriai, Borkowski said that he had no reason to mourn the Jews since antisemitism had been “beaten into his head” when he served in the Polish border guards before the war and he believed that the Jews were “parasites.” }}</ref> served in it too.<ref name=Bubnys2>{{cite web |url= http://www.genocid.lt/Leidyba/1/arunas1.htm |title= Vokiečių ir lietuvių saugumo policija (1941–1944) |accessdate=2007-02-18 |last=Bubnys |first=Arūnas |authorlink=Arūnas Bubnys |year=2004 |language=Lithuanian |quote=Daugumą būrio narių sudarė lietuviai, tačiau buvo keletas rusų ir lenkų.}}</ref> The victims were usually brought to the edges of huge pits and shot to death with machine gun fire. | |||

| |url=http://www.ipn.gov.pl/portal.php?serwis=pl&dzial=194&id=3327 | |||

| |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071017215515/http://www.ipn.gov.pl/portal.php?serwis=pl&dzial=194&id=3327 | |||

| |url-status=dead | |||

| |archive-date=2007-10-17 | |||

| |title=Śledztwo w sprawie masowych zabójstw Polaków w latach 1941–1944 w Ponarach koło Wilna dokonanych przez funkcjonariuszy policji niemieckiej i kolaboracyjnej policji litewskiej | |||

| |trans-title=Investigation of the mass murder of Poles in 1941–1944 at Ponary near Wilno by functionaries of German police and the Lithuanian collaborationist forces |author=KŚZpNP | |||

| |publisher=] | |||

| |journal=Documents of the Ongoing Investigation | |||

| |via=Internet Archive, 17 October 2007 | |||

| |language=pl |year=2003 | |||

| }}</ref><ref>{{cite book | |||

| |author-link=Arūnas Bubnys | |||

| |trans-title=Vokiečių ir lietuvių saugumo policija | |||

| |title=German and Lithuanian Security Police, 1941–44 | |||

| |year=2004 | |||

| |publisher=] |location=Vilnius | |||

| |url=http://www.genocid.lt/Leidyba/1/arunas1.htm | |||

| |access-date=9 June 2006 | |||

| |language=lt | |||

| |first=Arūnas | |||

| |last=Bubnys | |||

| }}</ref> during ] and ] in the '']'' of '']''. The murders took place between July 1941 and August 1944 near the railway station at Ponary (now ]), a suburb of today's ], Lithuania. 70,000 Jews were murdered at Ponary,{{efn|Unlike the Jews of sovereign Lithuania before 1939 (or the '']'' after ]), who had their own complex identity and could be described retroactively as either ], ] or ],<ref name="Jews"> | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| |first=Ezra | |||

| |last=Mendelsohn | |||

| |title=On Modern Jewish Politics | |||

| |publisher=Oxford University Press | |||

| |year=1993 | |||

| |isbn=0-19-508319-9 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=g72diKsztnQC&pg=RA1-PA8 |page=8 | |||

| }} ''Also in:'' | |||

| {{cite book |author-link=Mark Abley |first=Mark | |||

| |last=Abley | |||

| |title=Spoken Here: Travels Among Threatened Languages |publisher=Houghton Mifflin Books | |||

| |year=2003 | |||

| |isbn=0-618-23649-X | |||

| |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=oyyyybR6RmwC&pg=PT277 | |||

| |pages=205, 277–279 | |||

| }}</ref> the Jews of the Wilno region were citizens of the ] before the German-Soviet invasion of September 1939; and thousands of refugees from German-occupied Poland kept arriving.<ref name="Balkelis248">{{harvp|Balkelis|2013|p=248|loc=}}</ref> In October 1939 ]. On the eve of its Soviet annexation in June 1940, Vilna was home to around 100,000 newcomers, including 85,000 Poles, 10,000 Jews, and 5,000 Belorussians and Russians.<ref name=TB246> | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Xam0fUlrXfkC&pg=PA246 | |||

| |editor1=] | |||

| |editor2=Eric D. Weitz | |||

| |title=Shatterzone of Empires: Coexistence and Violence in the German, Habsburg, Russian, and Ottoman Borderlands | |||

| |chapter=Nationalizing the Borderlands | |||

| |first=Tomas | |||

| |last=Balkelis | |||

| |pages=246–252 | |||

| |isbn=978-0253006318 | |||

| |year=2013 | |||

| |publisher=Indiana University Press | |||

| }}</ref> Ethnic Lithuanians represented less than 0.7 percent of the inhabitants of the city.<ref name="Niwinski"> | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| |title=Ponary: the Place of "Human Slaughter" | |||

| |last=Niwiński | |||

| |first=Piotr | |||

| |year=2011 | |||

| |publisher=Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, Komisja Ścigania Zbrodni przeciwko Narodowi Polskiemu; ], Departament Współpracy z Polonią | |||

| |location=Warsaw | |||

| |pages=25–26 | |||

| |url=http://www.msz.gov.pl/resource/65eb5501-876b-4915-a8dd-48ec00882c54 | |||

| |language=pl, en, lt | |||

| }}</ref><sup></sup>}} along with up to 2,000 Poles,<ref>{{Cite book |last=Tomkiewicz |first=Monika |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=i8arPgAACAAJ |title=Zbrodnia w Ponarach 1941-1944 |date=2008 |publisher=Instytut Pamięci Narodowej--Komisja Ścigania Zbrodni przeciwko Narodowi Polskiemu |isbn=978-83-60464-91-5 |page=216 |language=pl}}</ref> 8,000 Soviet POWs, most of them from nearby Vilnius, and its newly formed ].<ref name="Sak_Ard"> | |||

| ], ], ''Ponary Diary, 1941–1943: A Bystander's Account of a Mass Murder'', Yale University Press, 2005, {{ISBN|0-300-10853-2}}, . | |||

| </ref><ref name="Piotrowski_168"> | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| |author-link=Tadeusz Piotrowski (sociologist) | |||

| |first=Tadeusz | |||

| |last=Piotrowski | |||

| |title=Poland's Holocaust | |||

| |publisher=McFarland & Company | |||

| |year=1998 |isbn=0-7864-0371-3 | |||

| |url=https://archive.org/details/polandsholocaust00piot | |||

| |url-access=registration | |||

| |page= | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| Lithuania became one of the first locations outside ] in World War II where the Nazis mass-murdered Jews as part of the ].{{efn|According to Miller-Korpi (1998), one of the areas to first experience the totality of Hitler’s "Final Solution" for the Jews were the Baltic countries.<ref name="Korpi"> | |||

| ] | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| |first=Katy | |||

| |last=Miller-Korpi | |||

| |year=1998 | |||

| |title=The Holocaust in the Baltics | |||

| |publisher=University of Washington, Department papers online |url=http://depts.washington.edu/baltic/papers/holocaust.html | |||

| |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080307033256/http://depts.washington.edu/baltic/papers/holocaust.html | |||

| |url-status=dead | |||

| |archive-date=2008-03-07 | |||

| |id=Internet Archive, March 7, 2008 | |||

| }}</ref> Her opinion nevertheless was challenged by Dr. Samuel Drix (''Witness to Annihilation''), and Jochaim Schoenfeld (''Holocaust Memoirs'') who argued that the Final Solution began in '']''.}} According to ], out of 70,000 Jews living in Vilna, only about 7,000 survived the war.<ref name="Snyder"> | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| |author-link=Timothy Snyder | |||

| |title=The Reconstruction of Nations: Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 1569–1999 |publisher=Yale University Press | |||

| |isbn=0-300-10586-X |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=xSpEynLxJ1MC&q=Ypatingas+Burys&pg=PA84 | |||

| |via=Google Books, preview | |||

| |pages=84–89 | |||

| |first=Timothy | |||

| |last=Snyder | |||

| |year=2003 }}</ref> The number of dwellers, estimated by Steven P. Sedlis, as of June 1941 was 80,000 Jews, or one-half of the city's population.<ref name="Grodin"> | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| |chapter=Jewish Medical Resistance in the Holocaust | |||

| |first2=Michael A. | |||

| |last2=Grodin | |||

| |publisher=Berghahn Books | |||

| |year=2014 | |||

| |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=VyEfAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA148 | |||

| |page=148 | |||

| |title=The Establishment of a Public Health Service in the Vilna Ghetto | |||

| |first1=Steven P. | |||

| |last1=Sedlis | |||

| |isbn=978-1782384182 | |||

| }}</ref> More than two-thirds of them, or at least 50,000 Jews, had been killed before the end of 1941.<ref name="Laqueur"> | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| |page=254 | |||

| |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=nPbr0XzlTzcC&pg=PA254 | |||

| |title=The Holocaust Encyclopedia | |||

| |last1=Baumel | |||

| |first1=Judith Tydor | |||

| |last2=Laqueur | |||

| |first2=Walter | |||

| |publisher=Yale University Press | |||

| |year=2001 | |||

| |isbn=0300138113}} ''Also in:'' {{cite book |title=Holocaust Chronicles: Individualizing the Holocaust Through Diaries and Other Contemporaneous Personal Accounts | |||

| |first=Robert Moses | |||

| |last=Shapiro | |||

| |publisher=KTAV Publishing House | |||

| |year=1999 |isbn=0881256307 | |||

| |page= |url=https://archive.org/details/holocaustchronic00robe|url-access=registration }}</ref><ref name="Woolfson"> | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| |title=Holocaust Legacy in Post-Soviet Lithuania: People, Places and Objects |first=Shivaun | |||

| |last=Woolfson | |||

| |publisher=Bloomsbury Publishing | |||

| |year=2014 |isbn=978-1472522955 | |||

| |page=3 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=DowIBAAAQBAJ&pg=PA3 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| ==Background== | |||

| During the ] the town of Ponary was part of the ], ] (] region). In September 1939 the region was ]. After the annexation of Lithuania by the ], the following year, the Soviet authorities started to build a huge oil warehouse for a nearby military ]. The construction was never finished as in ] the area ] by ]. The Nazis decided to take advantage of the large pits dug for the oil warehouses to dispose of bodies of unwanted locals. The massacres began in July, 1941, when ] rounded up 5,000 Jewish men of Wilno and took them to Paneriai where they were shot. Further mass killings took place throughout the summer and fall.<ref name="Bubnys"/> By the end of the 1941 year, more than 40,000 Jews had been killed at Paneriai.{{fact}} Germans were aided by ] in 1941 killings, during 1943 Ypatingasis burys killed less then in 1941, while in 1944 Ypatingasis burys did not carry any more killings.<ref name="Bubnys"/> | |||

| Following ] and the creation of the short-lived ], in accordance with international agreements ratified in 1923 by the ],<ref name=miniotaite> | |||

| {{cite web | |||

| |first=Grazina | |||

| |last=Miniotaite | |||

| |title=The Security Policy of Lithuania and the 'Integration Dilemma' | |||

| |publisher=NATO Academic Forum | |||

| |date=1999 | |||

| |url=http://www.nato.int/acad/fellow/97-99/miniotaite.pdf | |||

| |page=21 | |||

| }}</ref> the town of Ponary became part of the ] (] region) of the ]. The predominant languages in the area were ] and ].<ref name="muller"> | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| |chapter=Memory and Power in Post-War Europe: Studies in the Presence of the Past |publisher=Cambridge University Press | |||

| |editor-last=Müller | |||

| |editor-first=Jan-Werner | |||

| |year=2002 | |||

| |page=47 | |||

| |isbn=9780521000703 | |||

| |title=Poland, Lithuania and Ukraine, 1939–1999 | |||

| |first=Timothy | |||

| |last=Snyder | |||

| |author-link=Timothy Snyder | |||

| |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=wOsSG0K8hCYC&pg=PA46 | |||

| }}</ref> After the Nazi-Soviet ] in September 1939, the region was ] and after about a month, on October 10, transferred to Lithuania under the ]. | |||

| Following the ] of Lithuania and the Baltic states in June 1940, construction of an oil storage facility began near Ponary for a future Soviet military airfield. That project was never completed, and in June 1941 the area was taken by the ] in ]. The Nazi killing squads used the six large pits excavated for the oil storage tanks to hide the bodies of the locals killed there.<ref name="media">Vilnius Yiddish Institute (2009), {{YouTube|3ymAxQjLKmM|The Tour of Ponar, part 1 (3:22 min.)|link=no}}. As well as {{YouTube|VnL0gQZa0tQ|The Tour of Ponar, part 2 (6:47 min.)|link=no}}.</ref>{{rs?|date=December 2023}} | |||

| The total number of victims by the end of 1944 was between 70,000 and 100,000. According to post-war ] by the forces of ] the majority (50,000–70,000) of the victims were ] and ] from nearby Polish and Lithuanian cities, while the rest were primarily ] (about 20,000) and ] (about 8,000)<ref name="WSP-Ponary"/><ref name="IPN-Ponary"/>, although these numbers are disputed. The Polish victims were mostly members of Polish ] (teachers, professors of the ] like ], priests like ]) and members of ] ].<ref name="WSP-Ponary"/><ref name="Piotrowski_168"/> Among the first victims were approximatly 7,500 Soviet ]s shot in ] soon after ] begun.<ref name="Rzecz-Ponary">. Last accessed on 10 February 2007.</ref> At later stages there were also smaller numbers of victims of other nationalities, including local Russians, ] and Lithuanians, particularly communists sympathisers and members of general ] ] who refused to follow German orders<ref name="WSP-Ponary"/>. | |||

| ==Massacres== | |||

| As Soviet troops advanced in 1943, the German-led units tried to ] the crime. A unit of eighty workers was formed from nearby ] prisoners and was forced to dig up the bodies, pile them on wood and burn them. The ashes were then mixed with sand and buried.<ref name="WSP-Ponary"/> After six months of this gruesome work, aware that eventually they would be executed themselves,{{fact}} the brigade managed to escape on ], ]. Eleven of them managed to survive the ordeal, and their testimony contributed to revealing the massacre. The information about it begun to spread as early as 1943, due to the activities and works of ], ], ] and others. Nonetheless the Soviet regime, which supported the resettlement of Poles from the ], also found it convenient to deny that Poles were massacred in Panerai; the official line was that Panerai was a site of massacre of Soviet citizens only.{{fact}} It was only a decade after the ] that the new government of independent Lithuania allowed a monument (a cross) to fallen Polish citizens to be built there.<ref name="Rzecz-Ponary"/> | |||

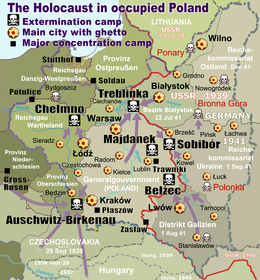

| ] (top right corner, near ]), marked with a white skull]] | |||

| The ]s began as soon as SS '']'' arrived in Vilna on 2 July 1941.<ref name="Snyder"/> Most of the actual killings were carried out by the ] (Lithuanian volunteers) 80 men strong.<ref name="Woolfson"/> On 9 August 1941, ] 9 was replaced by EK 3.<ref name="KDR38"> | |||

| The site of the massacre is commemorated by a memorial to the victims of the Holocaust<!--when was it raised and what is it?-->, a memorial to the Polish victims and a small museum (currently closed). The executions at Paneriai, sometimes compared to the ] by Polish press (since it happened in 'the East' and was mostly ignored by the communist government of ]), are currently a matter of an investigation by the ] branch of the Polish ].<ref name="IPN-Ponary"/> | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| |first1=Ernst | |||

| |last1=Klee | |||

| |first2=Willi | |||

| |last2=Dressen | |||

| |first3= Volker | |||

| |last3=Riess | |||

| |title=The Good Old Days: The Holocaust as Seen by Its Perpetrators and Bystanders |publisher=Free Press | |||

| |year=1991 | |||

| |isbn=1568521332 | |||

| |url=https://archive.org/details/isbn_9780029174258 | |||

| |url-access=registration | |||

| |pages=–58 | |||

| |chapter=Soldiers from a motorized column watch a massacre in Paneriai, Lithuania}}</ref> In September, the ] was established.<ref name="Snyder"/> In the same month 3,700 Jews were shot in one operation, and 6,000 in another; rounded up in the city and walked to Paneriai. Most victims were stripped before being shot. Further mass killings by Ypatingasis burys<ref name="Snyder"/> took place throughout the summer and autumn. | |||

| By the end of the year, about 50,000–60,000 Vilna Jews—men, women, and children—had been killed.<ref name="Laqueur"/> According to Snyder 21,700 of them were shot at Ponary,<ref name="Snyder"/> but there are serious discrepancies in the death toll for this period. ] supplied information in his book ''Ghetto in Flames'' based on original Jewish documentation augmented by the ], ration cards and work permits. | |||

| According to his estimates, until the end of December, 33,500 Jews of Vilna were murdered in Ponary, 3,500 fled east, and 20,000 remained in the ghetto.<ref name="Arad"> | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| |first=Yitzhak | |||

| |last=Arad | |||

| |author-link=Yitzhak Arad | |||

| |year=1980 | |||

| |title=Ghetto in Flames | |||

| |chapter=Chapter 13: The Toll of the Extermination Operations (July–December 1941) |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=y1rIidjdSVcC&pg=PA211 | |||

| |publisher=KTAV Publishing House | |||

| |pages=209–217 | |||

| }}</ref>{{rp|215}} The reason for such a wide range of estimated deaths was the presence of war refugees arriving from German-occupied western Poland, whose residence rights were denied by the new Lithuanian administration. On the eve of the Soviet annexation of Lithuania in June 1940, Vilna was home to around 100,000 newcomers, including 85,000 Poles, and 10,000 Jews according to Lithuanian Red Cross.<ref name="Balkelis248"/> | |||

| The pace of killings slowed in 1942, as ghettoised Jewish slave-workers were appropriated by the Wehrmacht.<ref name="Snyder"/> As Soviet troops advanced in 1943, the Nazi units tried to cover up the crime under the ] directive. Eighty inmates from the ] were formed into ''Leichenkommando'' ("corpse units"). The workers were forced to dig up bodies, pile them on wood and burn them. The ashes were then ground up, mixed with sand and buried. After months of this work, the brigade managed to escape on 19 April 1944 through a tunnel dug with spoons. Eleven of the eighty who escaped survived the war; their testimony contributed to revealing the massacre.<ref>, a witness and participant of the event, as recorded by ] and ] in ''The Black Book: The Ruthless Murder of Jews by German-Fascist Invaders Throughout the Temporarily-Occupied Regions of the Soviet Union and in the Death Camps of Poland during the War 1941–1945'' {{in lang|ru|en}} . {{ISBN|0-89604-031-3}}.</ref><ref>Nicholas St. Fleur (June 29, 2016). . '']''.</ref> | |||

| ==Victims== | |||

| The total number of victims by the end of 1944 was between 70,000 and 100,000. According to post-war ] by the forces of Soviet ] the majority (50,000–70,000) of the victims were ] and ] from nearby Polish and Lithuanian cities, while the rest were primarily Poles (about 20,000) and Russians (about 8,000). According to Monika Tomkiewicz, author of a 2008 book on the Ponary massacre, 80,000 people were killed, including 72,000 Jews, 5,000 Soviet prisoners, between 1,500 and 2,000 Poles, 1,000 people described as Communists or Soviet activists, and 40 ].<ref name="Zbrodnia ponarska w świetle dokumentów">Andrzej Kaczyński, {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140223091011/http://wyborcza.pl/1,75968,6725805,Zbrodnia_ponarska_w_swietle_dokumentow.html | |||

| |date=February 23, 2014 }}, wyborcza.pl, 17 June 2009; accessed 8 December 2014.</ref> | |||

| The Polish victims were mostly members of the Polish ]—academics, educators such as ], a professor at ], priests such as Father Romuald Świrkowski, and members of the ] ].<ref name="Piotrowski_168"/> Among the first victims were approximately 7,500 Soviet ]s shot in 1941 soon after ] began.<ref name="Rzecz-Ponary">. Last accessed on 10 February 2007.</ref> At later stages there were also smaller numbers of victims of other nationalities, including local Russians, Romani and Lithuanians, particularly Communist sympathizers (], Valerijonas Knyva, ], and Aleksandra Bulotienė) and over 90 soldiers of General ]' ] who refused to follow German orders. | |||

| ==Commemoration== | |||

| Information about the massacre began to spread as early as 1943, due to the activities and works of ], ], ] and others. Nonetheless the Soviet regime, which supported the resettlement of Poles from the ], found it convenient to deny that Poles or Jews were singled out for massacre in Paneriai; the official line was that Paneriai was a site of massacre of Soviet citizens only.<ref name="Rzecz-Ponary"/><ref name="chgs"> (with photo gallery); accessed 15 March 2007.</ref> | |||

| On 22 October 2000, a decade after the ], an effort by several Polish organizations raised a cross to fallen Polish citizens, in an official ceremony attended by ], ], and his Lithuanian counterpart, as well as several ]s.<ref name="WSP-Ponary">{{cite journal |last=Michalski |first=Czesław |date=Winter 2000–2001 |title=Ponary — the Golgotha of Wilno |trans-title=Ponary – Golgota Wileńszczyzny |url=http://www.wsp.krakow.pl/konspekt/konspekt5/ponary.html |url-status=dead |journal=Konspekt |language=pl |publisher=] |volume=5 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081224124407/http://www.wsp.krakow.pl/konspekt/konspekt5/ponary.html |archive-date=2008-12-24 |via=Internet Archive, 24 December 2008}}</ref><ref name="Rzecz-Ponary"/><ref name="adw">{{cite journal |first=Stanisław | |||

| |last=Mikke | |||

| |url=http://www.adwokatura.pl/aktualnosci_sprawozdania_1112.htm | |||

| |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080225130054/http://www.adwokatura.pl/aktualnosci_sprawozdania_1112.htm | |||

| |url-status=dead | |||

| |archive-date=2008-02-25 | |||

| |title=In Ponary | |||

| |trans-title=W Ponarach | |||

| |via=Internet Archive, 2008-02-25 | |||

| |journal=Adwokatura.pl}}. Message from the Polish-Lithuanian Memorial Ceremony in Panerai, 2000. On the pages of Polish Bar Association.</ref> | |||

| On the site of the massacre is a monument to the victims of the Holocaust erected in 1991, a memorial to Polish victims erected in 1990, reconstructed in 2000, a monument to soldiers of Lithuanian Local Squad killed by Nazis in May 1944, erected in 2004, and a memorial stone to Soviet war prisoners, starved to death and shot here in 1941, erected in 1996, as well as a small museum. The first monument on the site was built by Vilnius Jews in 1948 but was replaced by the Soviet regime with a conventional obelisk dedicated to "Victims of Fascism".<ref>Zigmas Vitkus, "Paneriai: senojo žydų atminimo paminklo byla (1948–1952)", ''Naujasis Židinys-Aidai'', 2019, nr. 2, p. 27–35.</ref> | |||

| The murders at Paneriai are currently{{when|date=December 2023}} being investigated by the ] branch of the Polish ]<ref name="IPN-Ponary"/> and by the Genocide and .<ref>Arūnas Bubnys, ''Vokiečių saugumo policijos ir SD Vilniaus ypatingasis būrys 1941–1944'', Vilnius: Lietuvos gyventojų genocido ir rezistencijos tyrimų centras, 2019.</ref> The basic facts about memorial signs in the Paneriai memorial and the objects of the former mass murder site (killing pits, tranches, gates, paths, etc.) are now presented in the created by the Vilna Gaon State Jewish Museum. | |||

| The massacre was recorded by Polish journalist ] (1899-1944) in a series of journal entries written in hiding at his farm house in Wilno, Lithuania. After Sakowicz's death in 1944, the collection of entries were located and found on various scrap pieces of paper, soda bottles and a calendar from 1941 by holocaust-survivor and author ]. Margolis, who had lost family members in the Ponary massacre, later published the collection in 1999 in Polish. The diary became important to tracing the timeline of the massacre, and in many instances gave closure to surviving family members on what happened to their loved ones. Written in detail, the diary is a testimonial written from a first-person witness account of the atrocities.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Ponary Diary, 1941-1943 {{!}} Yale University Press|url=https://yalebooks.yale.edu/book/9780300108538/ponary-diary-1941-1943|access-date=2022-02-16|website=yalebooks.yale.edu}}</ref> | |||

| ===Memorial at the site=== | |||

| <gallery class="center" mode="packed"> | |||

| File:Jamroski paneriai.jpg| Pit used to burn corpses that were exhumed to destroy evidence of mass murders. | |||

| File:Paneriai monument 3.jpg|Memorial for Jewish victims. | |||

| File:Lithuania Ponary Monument.jpg|Memorial for Polish victims. | |||

| File:Paneriai monument 2b.jpg|Memorial for Soviet victims. | |||

| File:Paneriai Pit.jpg|An excavated pit used to cremate corpses | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | *] | ||

| == |

==References== | ||

| ===Footnotes=== | |||

| <!--See http://en.wikipedia.org/Wikipedia:Footnotes for an explanation of how to generate footnotes using the <ref(erences/)> tags--> | |||

| {{notelist}} | |||

| <div class='references-small'> | |||

| <references/> | |||

| ===Citations=== | |||

| </div> | |||

| {{Reflist|2}} | |||

| ==Further reading== | |||

| * {{cite book | vauthors=((Cassedy, E.)) | date=2012 | title=We Are Here: Memories of the Lithuanian Holocaust | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=HX-6OQJ_WB8C | publisher=University of Nebraska Press | edition=Illustrated | isbn=978-0-8032-4022-3 }} | |||

| * {{cite book | vauthors=((Gordon, H.)) | date=2000 | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3Bpe0ElkSMwC | title=The Shadow of Death: The Holocaust in Lithuania | publisher=University Press of Kentucky| isbn=978-0-8131-4360-6 }} | |||

| * {{cite book | vauthors=((Greenbaum, M.)) | date=2018 | title=The Jews of Lithuania: A History of a Remarkable Community 1316-1945 | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=E2_ag8xGWMQC | publisher=Gefen Publishing House | isbn=978-965-229-132-5 }} | |||

| * {{cite book | vauthors=((Vanagaitė, R.)), ((Zuroff, E.)) | date=2020 | title=Our People: Discovering Lithuania's Hidden Holocaust | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=MslmxwEACAAJ | publisher=Rowman & Littlefield | isbn=978-1-5381-3303-3 }} | |||

| * {{cite book | vauthors=((Weeks, T. R.)) | date=2015 | title=Vilnius between Nations, 1795–2000 | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=bq68DwAAQBAJ |publisher=Northern Illinois University Press | isbn=978-1-60909-191-0 }} | |||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| * ; ]. | |||

| <!-- * 404 as of 10 Feb 2007--> | |||

| * {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060420212303/http://www.noarfamily.com/PONARYFOREST.html |date=April 20, 2006 |title=Ponary Forest }} | |||

| * , US Holocaust Museum article on Vilna | |||

| * ; Holocaust Encyclopedia, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. | |||

| * at deathcamps.org | |||

| * ; RTR Foundation. | |||

| * {{pl icon}} (Conference "Poles as victims in Ponary near Wilno 1941–4) — IPN | |||

| * , Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team. | |||

| * {{pl icon}} (Crime of Ponary) - reprints of articles from ], Nr 109 (1605) z 12 maja 2003 | |||

| * , Timothy Snyder, The New York Review, July 25, 2011. | |||

| * ; Institute Of National Remembrance | |||

| * | |||

| ===Film and images=== | |||

| ] | |||

| * {{YouTube|PEWPx5dfj8w|Yad Vashem interview about Ponar}}. | |||

| ] | |||

| * ; vilnaghetto.com | |||

| ] | |||

| * {{Commons category-inline|Ponary massacre}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Holocaust Lithuania}} | |||

| {{Jews and Judaism in Lithuania}} | |||

| {{Massacres of Poles}} | |||

| {{Einsatzgruppen}} | |||

| {{The Holocaust}} | |||

| {{Massacres of Jews}} | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 06:57, 25 November 2024

1941–1944 Nazi murders in Vilnius, Lithuania| Ponary massacre | |

|---|---|

One of six Ponary murder pits in which victims were shot (July 1941). Note the ramp leading down and the group of men forced to wear hoods. One of six Ponary murder pits in which victims were shot (July 1941). Note the ramp leading down and the group of men forced to wear hoods. | |

| Also known as | Polish: zbrodnia w Ponarach |

| Location | Paneriai (Ponary), Vilnius (Wilno), Reichskommissariat Ostland 54°37′35″N 25°09′40″E / 54.6264°N 25.1612°E / 54.6264; 25.1612 |

| Date | July 1941 – August 1944 |

| Incident type | Shootings by automatic and semi-automatic weapons, genocide |

| Perpetrators | SS Einsatzgruppe Lithuanian collaborators |

| Ghetto | Vilnius Ghetto |

| Victims | ~100,000 in total (Jews: 70,000; Poles: From 1,000 to 2,000 Soviets/Russians: 8,000) |

| Documentation | Nuremberg Trials |

| Polish–Lithuanian ethnic Conflict | |

|---|---|

The Ponary massacre (Polish: zbrodnia w Ponarach), or the Paneriai massacre (Lithuanian: Panerių žudynės), was the mass murder of up to 100,000 people, mostly Jews, Poles, and Russians, by German SD and SS and the Lithuanian Ypatingasis būrys killing squads, during World War II and the Holocaust in the Generalbezirk Litauen of Reichskommissariat Ostland. The murders took place between July 1941 and August 1944 near the railway station at Ponary (now Paneriai), a suburb of today's Vilnius, Lithuania. 70,000 Jews were murdered at Ponary, along with up to 2,000 Poles, 8,000 Soviet POWs, most of them from nearby Vilnius, and its newly formed Vilna Ghetto.

Lithuania became one of the first locations outside occupied Poland in World War II where the Nazis mass-murdered Jews as part of the Final Solution. According to Timothy Snyder, out of 70,000 Jews living in Vilna, only about 7,000 survived the war. The number of dwellers, estimated by Steven P. Sedlis, as of June 1941 was 80,000 Jews, or one-half of the city's population. More than two-thirds of them, or at least 50,000 Jews, had been killed before the end of 1941.

Background

Following Żeligowski's Mutiny and the creation of the short-lived Central Lithuania, in accordance with international agreements ratified in 1923 by the League of Nations, the town of Ponary became part of the Wilno Voivodship (Kresy region) of the Second Polish Republic. The predominant languages in the area were Polish and Yiddish. After the Nazi-Soviet invasion of Poland in September 1939, the region was annexed by the Soviets and after about a month, on October 10, transferred to Lithuania under the Soviet–Lithuanian Treaty.

Following the Soviet annexation of Lithuania and the Baltic states in June 1940, construction of an oil storage facility began near Ponary for a future Soviet military airfield. That project was never completed, and in June 1941 the area was taken by the Wehrmacht in Operation Barbarossa. The Nazi killing squads used the six large pits excavated for the oil storage tanks to hide the bodies of the locals killed there.

Massacres

The massacres began as soon as SS Einsatzkommando 9 arrived in Vilna on 2 July 1941. Most of the actual killings were carried out by the Ypatingasis burys (Lithuanian volunteers) 80 men strong. On 9 August 1941, EK 9 was replaced by EK 3. In September, the Vilna Ghetto was established. In the same month 3,700 Jews were shot in one operation, and 6,000 in another; rounded up in the city and walked to Paneriai. Most victims were stripped before being shot. Further mass killings by Ypatingasis burys took place throughout the summer and autumn.

By the end of the year, about 50,000–60,000 Vilna Jews—men, women, and children—had been killed. According to Snyder 21,700 of them were shot at Ponary, but there are serious discrepancies in the death toll for this period. Yitzhak Arad supplied information in his book Ghetto in Flames based on original Jewish documentation augmented by the Einsatzgruppen reports, ration cards and work permits.

According to his estimates, until the end of December, 33,500 Jews of Vilna were murdered in Ponary, 3,500 fled east, and 20,000 remained in the ghetto. The reason for such a wide range of estimated deaths was the presence of war refugees arriving from German-occupied western Poland, whose residence rights were denied by the new Lithuanian administration. On the eve of the Soviet annexation of Lithuania in June 1940, Vilna was home to around 100,000 newcomers, including 85,000 Poles, and 10,000 Jews according to Lithuanian Red Cross.

The pace of killings slowed in 1942, as ghettoised Jewish slave-workers were appropriated by the Wehrmacht. As Soviet troops advanced in 1943, the Nazi units tried to cover up the crime under the Aktion 1005 directive. Eighty inmates from the Stutthof concentration camp were formed into Leichenkommando ("corpse units"). The workers were forced to dig up bodies, pile them on wood and burn them. The ashes were then ground up, mixed with sand and buried. After months of this work, the brigade managed to escape on 19 April 1944 through a tunnel dug with spoons. Eleven of the eighty who escaped survived the war; their testimony contributed to revealing the massacre.

Victims

The total number of victims by the end of 1944 was between 70,000 and 100,000. According to post-war exhumation by the forces of Soviet 2nd Belorussian Front the majority (50,000–70,000) of the victims were Polish Jews and Lithuanian Jews from nearby Polish and Lithuanian cities, while the rest were primarily Poles (about 20,000) and Russians (about 8,000). According to Monika Tomkiewicz, author of a 2008 book on the Ponary massacre, 80,000 people were killed, including 72,000 Jews, 5,000 Soviet prisoners, between 1,500 and 2,000 Poles, 1,000 people described as Communists or Soviet activists, and 40 Romani people.

The Polish victims were mostly members of the Polish intelligentsia—academics, educators such as Kazimierz Pelczar, a professor at Stefan Batory University, priests such as Father Romuald Świrkowski, and members of the Armia Krajowa resistance movement. Among the first victims were approximately 7,500 Soviet P.O.W.s shot in 1941 soon after Operation Barbarossa began. At later stages there were also smaller numbers of victims of other nationalities, including local Russians, Romani and Lithuanians, particularly Communist sympathizers (Liudas Adomauskas, Valerijonas Knyva, Andrius Bulota, and Aleksandra Bulotienė) and over 90 soldiers of General Povilas Plechavičius' Local Lithuanian Detachment who refused to follow German orders.

Commemoration

Information about the massacre began to spread as early as 1943, due to the activities and works of Helena Pasierbska, Józef Mackiewicz, Kazimierz Sakowicz and others. Nonetheless the Soviet regime, which supported the resettlement of Poles from the Kresy, found it convenient to deny that Poles or Jews were singled out for massacre in Paneriai; the official line was that Paneriai was a site of massacre of Soviet citizens only.

On 22 October 2000, a decade after the fall of communism, an effort by several Polish organizations raised a cross to fallen Polish citizens, in an official ceremony attended by Bronisław Komorowski, Polish Minister of Defence, and his Lithuanian counterpart, as well as several NGOs.

On the site of the massacre is a monument to the victims of the Holocaust erected in 1991, a memorial to Polish victims erected in 1990, reconstructed in 2000, a monument to soldiers of Lithuanian Local Squad killed by Nazis in May 1944, erected in 2004, and a memorial stone to Soviet war prisoners, starved to death and shot here in 1941, erected in 1996, as well as a small museum. The first monument on the site was built by Vilnius Jews in 1948 but was replaced by the Soviet regime with a conventional obelisk dedicated to "Victims of Fascism".

The murders at Paneriai are currently being investigated by the Gdańsk branch of the Polish Institute of National Remembrance and by the Genocide and Resistance Research Center of Lithuania. The basic facts about memorial signs in the Paneriai memorial and the objects of the former mass murder site (killing pits, tranches, gates, paths, etc.) are now presented in the webpage created by the Vilna Gaon State Jewish Museum.

The massacre was recorded by Polish journalist Kazimierz Sakowicz (1899-1944) in a series of journal entries written in hiding at his farm house in Wilno, Lithuania. After Sakowicz's death in 1944, the collection of entries were located and found on various scrap pieces of paper, soda bottles and a calendar from 1941 by holocaust-survivor and author Rahel Margolis. Margolis, who had lost family members in the Ponary massacre, later published the collection in 1999 in Polish. The diary became important to tracing the timeline of the massacre, and in many instances gave closure to surviving family members on what happened to their loved ones. Written in detail, the diary is a testimonial written from a first-person witness account of the atrocities.

Memorial at the site

-

Pit used to burn corpses that were exhumed to destroy evidence of mass murders.

Pit used to burn corpses that were exhumed to destroy evidence of mass murders.

-

Memorial for Jewish victims.

Memorial for Jewish victims.

-

Memorial for Polish victims.

Memorial for Polish victims.

-

Memorial for Soviet victims.

Memorial for Soviet victims.

-

An excavated pit used to cremate corpses

An excavated pit used to cremate corpses

See also

References

Footnotes

- Unlike the Jews of sovereign Lithuania before 1939 (or the Generalbezirk Litauen after Operation Barbarossa), who had their own complex identity and could be described retroactively as either Polish, Lithuanian or Russian, the Jews of the Wilno region were citizens of the Second Polish Republic before the German-Soviet invasion of September 1939; and thousands of refugees from German-occupied Poland kept arriving. In October 1939 the city was ceded over to Lithuania. On the eve of its Soviet annexation in June 1940, Vilna was home to around 100,000 newcomers, including 85,000 Poles, 10,000 Jews, and 5,000 Belorussians and Russians. Ethnic Lithuanians represented less than 0.7 percent of the inhabitants of the city.

- According to Miller-Korpi (1998), one of the areas to first experience the totality of Hitler’s "Final Solution" for the Jews were the Baltic countries. Her opinion nevertheless was challenged by Dr. Samuel Drix (Witness to Annihilation), and Jochaim Schoenfeld (Holocaust Memoirs) who argued that the Final Solution began in Distrikt Galizien.

Citations

- Piotrowski 1998, p. 167.

- Tomkiewicz 2008, p. 216.

- ^ Kazimierz Sakowicz, Yitzhak Arad, Ponary Diary, 1941–1943: A Bystander's Account of a Mass Murder, Yale University Press, 2005, ISBN 0-300-10853-2, Google Print.

- ^ KŚZpNP (2003). "Śledztwo w sprawie masowych zabójstw Polaków w latach 1941–1944 w Ponarach koło Wilna dokonanych przez funkcjonariuszy policji niemieckiej i kolaboracyjnej policji litewskiej" [Investigation of the mass murder of Poles in 1941–1944 at Ponary near Wilno by functionaries of German police and the Lithuanian collaborationist forces]. Documents of the Ongoing Investigation (in Polish). Institute of National Remembrance. Archived from the original on 2007-10-17 – via Internet Archive, 17 October 2007.

- Bubnys, Arūnas (2004). German and Lithuanian Security Police, 1941–44 [Vokiečių ir lietuvių saugumo policija] (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Lietuvos gyventojų genocido ir rezistencijos tyrimo centras. Retrieved 9 June 2006.

- Mendelsohn, Ezra (1993). On Modern Jewish Politics. Oxford University Press. p. 8. ISBN 0-19-508319-9. Also in: Abley, Mark (2003). Spoken Here: Travels Among Threatened Languages. Houghton Mifflin Books. pp. 205, 277–279. ISBN 0-618-23649-X.

- ^ Balkelis (2013), p. 248, 'Red Cross'.

- Balkelis, Tomas (2013). "Nationalizing the Borderlands". In Omer Bartov; Eric D. Weitz (eds.). Shatterzone of Empires: Coexistence and Violence in the German, Habsburg, Russian, and Ottoman Borderlands. Indiana University Press. pp. 246–252. ISBN 978-0253006318.

- Niwiński, Piotr (2011). Ponary: the Place of "Human Slaughter" (in Polish, English, and Lithuanian). Warsaw: Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, Komisja Ścigania Zbrodni przeciwko Narodowi Polskiemu; Ministerstwo Spraw Zagranicznych Rzeczpospolitej Polskiej, Departament Współpracy z Polonią. pp. 25–26.

- Tomkiewicz, Monika (2008). Zbrodnia w Ponarach 1941-1944 (in Polish). Instytut Pamięci Narodowej--Komisja Ścigania Zbrodni przeciwko Narodowi Polskiemu. p. 216. ISBN 978-83-60464-91-5.

- ^ Piotrowski, Tadeusz (1998). Poland's Holocaust. McFarland & Company. p. 168. ISBN 0-7864-0371-3.

- Miller-Korpi, Katy (1998). The Holocaust in the Baltics. University of Washington, Department papers online. Internet Archive, March 7, 2008. Archived from the original on 2008-03-07.

- ^ Snyder, Timothy (2003). The Reconstruction of Nations: Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 1569–1999. Yale University Press. pp. 84–89. ISBN 0-300-10586-X – via Google Books, preview.

- Sedlis, Steven P.; Grodin, Michael A. (2014). "Jewish Medical Resistance in the Holocaust". The Establishment of a Public Health Service in the Vilna Ghetto. Berghahn Books. p. 148. ISBN 978-1782384182.

- ^ Baumel, Judith Tydor; Laqueur, Walter (2001). The Holocaust Encyclopedia. Yale University Press. p. 254. ISBN 0300138113. Also in: Shapiro, Robert Moses (1999). Holocaust Chronicles: Individualizing the Holocaust Through Diaries and Other Contemporaneous Personal Accounts. KTAV Publishing House. p. 162. ISBN 0881256307.

- ^ Woolfson, Shivaun (2014). Holocaust Legacy in Post-Soviet Lithuania: People, Places and Objects. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 3. ISBN 978-1472522955.

- Miniotaite, Grazina (1999). "The Security Policy of Lithuania and the 'Integration Dilemma'" (PDF). NATO Academic Forum. p. 21.

- Snyder, Timothy (2002). "Memory and Power in Post-War Europe: Studies in the Presence of the Past". In Müller, Jan-Werner (ed.). Poland, Lithuania and Ukraine, 1939–1999. Cambridge University Press. p. 47. ISBN 9780521000703.

- Vilnius Yiddish Institute (2009), The Tour of Ponar, part 1 (3:22 min.) on YouTube. As well as The Tour of Ponar, part 2 (6:47 min.) on YouTube.

- Klee, Ernst; Dressen, Willi; Riess, Volker (1991). "Soldiers from a motorized column watch a massacre in Paneriai, Lithuania". The Good Old Days: The Holocaust as Seen by Its Perpetrators and Bystanders. Free Press. pp. 38–58. ISBN 1568521332.

- Arad, Yitzhak (1980). "Chapter 13: The Toll of the Extermination Operations (July–December 1941)". Ghetto in Flames. KTAV Publishing House. pp. 209–217.

- Testimony of Y. Farber, a witness and participant of the event, as recorded by Vasily Grossman and Ilya Ehrenburg in The Black Book: The Ruthless Murder of Jews by German-Fascist Invaders Throughout the Temporarily-Occupied Regions of the Soviet Union and in the Death Camps of Poland during the War 1941–1945 (in Russian and English) . ISBN 0-89604-031-3.

- Nicholas St. Fleur (June 29, 2016). "Escape Tunnel Dug by Hand Is Found at Holocaust Massacre Site". The New York Times.

- Andrzej Kaczyński, Zbrodnia ponarska w świetle dokumentów Archived February 23, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, wyborcza.pl, 17 June 2009; accessed 8 December 2014.

- ^ Ponary. Last accessed on 10 February 2007.

- Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Lithuania at Ponary (with photo gallery); accessed 15 March 2007.

- Michalski, Czesław (Winter 2000–2001). "Ponary — the Golgotha of Wilno" [Ponary – Golgota Wileńszczyzny]. Konspekt (in Polish). 5. Academy of Pedagogy in Kraków. Archived from the original on 2008-12-24 – via Internet Archive, 24 December 2008.

- Mikke, Stanisław. "In Ponary" [W Ponarach]. Adwokatura.pl. Archived from the original on 2008-02-25 – via Internet Archive, 2008-02-25.. Message from the Polish-Lithuanian Memorial Ceremony in Panerai, 2000. On the pages of Polish Bar Association.

- Zigmas Vitkus, "Paneriai: senojo žydų atminimo paminklo byla (1948–1952)", Naujasis Židinys-Aidai, 2019, nr. 2, p. 27–35.

- Arūnas Bubnys, Vokiečių saugumo policijos ir SD Vilniaus ypatingasis būrys 1941–1944, Vilnius: Lietuvos gyventojų genocido ir rezistencijos tyrimų centras, 2019.

- "Ponary Diary, 1941-1943 | Yale University Press". yalebooks.yale.edu. Retrieved 2022-02-16.

Further reading

- Cassedy, E. (2012). We Are Here: Memories of the Lithuanian Holocaust (Illustrated ed.). University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-4022-3.

- Gordon, H. (2000). The Shadow of Death: The Holocaust in Lithuania. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-4360-6.

- Greenbaum, M. (2018). The Jews of Lithuania: A History of a Remarkable Community 1316-1945. Gefen Publishing House. ISBN 978-965-229-132-5.

- Vanagaitė, R., Zuroff, E. (2020). Our People: Discovering Lithuania's Hidden Holocaust. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-5381-3303-3.

- Weeks, T. R. (2015). Vilnius between Nations, 1795–2000. Northern Illinois University Press. ISBN 978-1-60909-191-0.

External links

- Vilna During the Holocaust; Yad Vashem.

- Ponary Forest at the Wayback Machine (archived April 20, 2006)

- US Holocaust Museum article on death of Vilna's Jews; Holocaust Encyclopedia, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

- Vilna: 1941-1943; RTR Foundation.

- Ponary - The Vilna Killing Site: Prototype for the Permanent Death Camps in Poland, Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team.

- Neglecting the Lithuanian Holocaust, Timothy Snyder, The New York Review, July 25, 2011.

- The crime in Ponary 1941–1944; Institute Of National Remembrance

- UC San Diego, Holocaust Living History Collection: Past is Prologue: A Journey of Discovery – with Barbara Michelman

Film and images

- Yad Vashem interview about Ponar on YouTube.

- Chronicles of the Vilna Ghetto: wartime photographs & documents; vilnaghetto.com

Media related to Ponary massacre at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ponary massacre at Wikimedia Commons

| The Holocaust in Lithuania | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| People |

| ||||||

| Groups |

| ||||||

| Events | |||||||

| Places | |||||||

| Topics | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groups |

| ||||||||

| Synagogues |

| ||||||||

| Yeshivas | |||||||||

| Massacres of ethnic Poles in World War II | |

|---|---|

| Present-day Poland |

|

| Pre-war Polish Volhynia (Wołyń Voivodeship, present-day Ukraine) | |

| Pre-war Polish Eastern Galicia (Stanisławów, Tarnopol and eastern Lwów Voivodeships, present-day Ukraine) | |

| Polish self-defence centres in Volhynia | |

| Remainder of present-day Ukraine | |

| Pre-war Polish Nowogródek, Polesie and eastern parts of Wilno and Białystok Voivodeships (present-day Belarus) | |

| Remainder of present-day Belarus | |

| Wilno Region Proper in the pre-war Polish Wilno Voivodeship (present-day Lithuania) | |

| Present-day Russia | |

| Present-day Germany | |

| Related articles |

|

| Einsatzgruppen and Einsatzkommandos | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| People |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Groups |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Crimes |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Records | |||||||||||||||||

| The Holocaust | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Massacres or pogroms against Jews | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st – 13th century |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 14th – 19th century |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 20th century |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 21st century |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Vilnius in World War II

- Paneriai

- 1941 in Lithuania

- 1942 in Lithuania

- 1943 in Lithuania

- 1944 in Lithuania

- Einsatzgruppen

- Holocaust massacres and pogroms in Lithuania

- Nazi massacres of Poles in World War II

- World War II prisoner of war massacres by Nazi Germany

- Jewish Lithuanian history

- Jewish Polish history

- Lithuania–Poland relations

- Lithuanian collaboration with Nazi Germany

- Massacres in 1941

- Massacres in 1942

- Massacres in 1943

- Massacres in 1944