| Revision as of 19:34, 11 March 2007 edit142.165.246.134 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 10:22, 10 November 2024 edit undoJevansen (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Page movers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers3,401,341 edits Removing from Category:French classical composers has subcat using Cat-a-lot | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|French composer (1908–1992)}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Featured article}} | |||

| {{Mergefrom|List of students of Olivier Messiaen|date=February 2007}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=April 2024}} | |||

| '''Olivier Messiaen''' ({{IPA2|mɛsjɑ̃}}; ], ] – ], ]) was a ] ], ]ist, and ]. He entered the ] at the age of 11, and numbered ], ], ] and ] among his teachers. He was appointed organist at the church of La Trinité in ] in 1931, a post he held until his death. On the ] in 1940 Messiaen was made a prisoner of war, and while incarcerated he composed his '']'' ("Quartet for the end of time") for the four available instruments, ], ], ], and ]. The piece was first performed by Messiaen and fellow prisoners to an audience of inmates and prison guards. Messiaen was appointed professor of ] soon after his release in 1941, and professor of ] in 1966 at the Paris Conservatoire, positions he held until his retirement in 1978. His ] included ], ] (who later became Messiaen's second wife), ], ] and ]. | |||

| {{Infobox classical composer | |||

| | name = Olivier Messiaen | |||

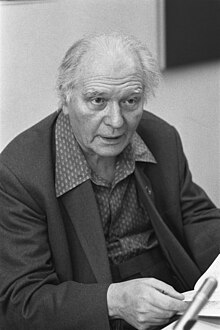

| | image = Lezing Franse compoist Olivier Messianen in Koninklijk Conservatorium in Den Haag 27 november 1986.jpg | |||

| | alt = A black-and-white photo of an elderly, balding man with swept-back hair, wearing a suit; he faces the camera. | |||

| | caption = Messiaen in 1986 | |||

| | parents = | |||

| | birth_date = {{birth date|1908|12|10|df=y}} | |||

| | birth_place = ], Third French Republic | |||

| | death_date = {{death date and age|1992|04|27|1908|12|10|df=y}} | |||

| | death_place = ], France | |||

| | list_of_works = ] | |||

| | spouse = {{ubl| ] | ] }} | |||

| }} | |||

| <!-- paragraph 1: general introduction, importance --> | |||

| '''Olivier Eugène Prosper Charles Messiaen''' ({{IPAc-en|UK|ˈ|m|ɛ|s|i|æ̃}},<ref>{{Cite encyclopedia |url=http://www.lexico.com/definition/Messiaen,+Olivier |title=Messiaen, Olivier |dictionary=] UK English Dictionary |publisher=]}}{{dead link|date=September 2022|bot=medic}}{{cbignore|bot=medic}}</ref> {{IPAc-en|US|m|ɛ|ˈ|s|j|æ̃|,_|m|eɪ|ˈ|s|j|æ̃|,_|m|ɛ|ˈ|s|j|ɑ̃}};<ref>{{Cite American Heritage Dictionary|Messiaen|access-date=18 August 2019}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/messiaen|title=Messiaen|work=]|publisher=]|access-date=18 August 2019}}</ref><ref>{{Cite Merriam-Webster|Messiaen|access-date=18 August 2019}}</ref> {{IPA|fr|ɔlivje øʒɛn pʁɔspɛʁ ʃaʁl mɛsjɑ̃|lang}}; 10 December 1908 – 27 April 1992) was a French composer, organist, and ]. One of the major composers of the ], he was also an outstanding teacher of composition and musical analysis. | |||

| <!-- paragraph 2: potted biography and influence --> | |||

| Messiaen entered the ] at age 11 and studied with ], ], ] and ], among others. He was appointed organist at the ], in 1931, a post he held for 61 years, until his death. He taught at the ] during the 1930s. After the ] in 1940, Messiaen was interned for nine months in the German prisoner of war camp ], where he composed his {{lang|fr|]}} (''Quartet for the End of Time'') for the four instruments available in the prison—piano, violin, cello and clarinet. The piece was first performed by Messiaen and fellow prisoners for an audience of inmates and prison guards.<ref name=":0" /> Soon after his release in 1941, Messiaen was appointed professor of harmony at the Paris Conservatoire. In 1966, he was appointed professor of composition there, and he held both positions until retiring in 1978. His ] included ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], and ], who became his second wife. | |||

| <!-- paragraph 3: influences and inspiration --> | |||

| Messiaen's music is ]ically complex (he was interested in rhythms from ] and from ] sources), and is harmonically and ] based on '']'', which were Messiaen's own innovation. Many of his compositions depict what he termed "the marvellous aspects of the faith", drawing on his unshakeable ]. He travelled widely, and he wrote works inspired by such diverse influences as ]ese music, the landscape of ] in ], and the life of ]. Messiaen experienced a mild form of ] manifested as a perception of colours when he heard certain harmonies, particularly harmonies built from his modes, and he used combinations of these colours in his compositions. For a short period Messiaen experimented with "total ]", in which field he is often cited as an innovator. His style absorbed many exotic musical influences such as Indonesian ] (tuned ] often features prominently in his orchestral works), and he also championed the ]. | |||

| Messiaen perceived colours when he heard certain ] (a phenomenon known as ]); according to him, combinations of these colours were important in his compositional process. He travelled widely and wrote works inspired by diverse influences, including ], the landscape of ] in Utah, and the life of ]. His style absorbed many global musical influences, such as Indonesian ] (tuned percussion often features prominently in his orchestral works). He found ] fascinating, notating bird songs worldwide and incorporating birdsong ] into his music. | |||

| <!-- paragraph 4: his music --> | |||

| Messiaen found ] fascinating; he believed birds to be the greatest musicians and considered himself as much an ornithologist as a composer. He notated birdsongs worldwide, and he incorporated birdsong ] into a majority of his music. His innovative use of colour, his personal conception of the relationship between time and music, his use of birdsong, and his intent to express profound religious ideas, all combine to make it almost impossible to mistake a composition by Messiaen for the work of any other western composer. | |||

| Messiaen's music is ]ically complex. ] and ], he employed a system he called '']'', which he abstracted from the systems of material his early compositions and improvisations generated. He wrote music for chamber ensembles and orchestra, voice, solo organ, and piano, and experimented with the use of novel electronic instruments developed in Europe during his lifetime. For a short period he experimented with the ] associated with "total serialism", in which field he is often cited as an innovator. His innovative use of colour, his conception of the relationship between time and music, and his use of birdsong are among the features that make Messiaen's music distinctive. | |||

| ==Biography== | ==Biography== | ||

| ===Youth and studies=== | ===Youth and studies=== | ||

| ] | |||

| Olivier Eugène Prosper Charles Messiaen was born in ] into a literary family. He was the elder of two sons of ], a poet, and ], a teacher of ] who translated the plays of ] into ]. Messiaen's mother published a sequence of poems, ''L'âme en bourgeon'' ("The Budding Soul"), the last chapter of ''Tandis que la terre tourne'' ("As the World Turns"), which address her unborn son. Messiaen later said this sequence of poems influenced him deeply, and cited it as prophetic of his future artistic career.<ref>Messiaen & Samuel (1994), p. 15</ref> | |||

| Olivier Eugène Prosper Charles Messiaen<ref>{{Cite web |last=] Civil Records |title=Olivier Eugène Prosper Charles Messiaen's birth certificate |url=https://cdn.discordapp.com/attachments/694193887220334613/889843906076872744/actenaissance.pdf}}</ref> was born on 10 December 1908 at 20 Boulevard Sixte-Isnard in ], France, into a literary family.<ref>Dingle (2007), p. 3</ref> He was the elder of two sons of ], a poet, and {{ill|Pierre Messiaen|fr|lt=Pierre Léon Joseph Messiaen}}, a scholar and teacher of English from a farm near ]<ref>''Visions of Amen: The Early Life and Music of Olivier Messiaen'', Stephen Schloesser</ref> who also translated ]'s plays into French.<ref>Hill & Simeone (2005), pp. 10–14</ref> Messiaen's mother published a sequence of poems, {{lang|fr|L'âme en bourgeon}} (''The Budding Soul''), the last chapter of {{lang|fr|Tandis que la terre tourne}} (''As the Earth Turns''), which address her unborn son. Messiaen later said this sequence of poems influenced him deeply and cited it as prophetic of his future artistic career.<ref>Messiaen & Samuel (1994), p. 15</ref> His brother {{ill|Alain Messiaen|fr|lt=Alain André Prosper Messiaen}}, four years his junior, became a poet. | |||

| On the outbreak of ] in 1914 Pierre Messiaen became a soldier, and their mother took the two boys to live with her brother in ]. Here Messiaen became fascinated with drama, reciting Shakespeare to his brother with the help of a home-made toy theatre with translucent backdrops made from old ] wrappers.<ref>Messiaen & Samuel (1994), p. 41</ref> At this time he also adopted the Roman Catholic faith. Later, Messiaen felt most at home in the Alps of the ], where he had a house built south of Grenoble, and he composed most of his music there.<ref>Hill (1995), pp. 300–1</ref> | |||

| At the outbreak of ], Pierre enlisted and Cécile took their two boys to live with her brother in ]. There Messiaen became fascinated with drama, reciting Shakespeare to his brother. Their homemade toy theatre had translucent backdrops made of cellophane wrappers.<ref>Messiaen & Samuel (1994), p. 41</ref> At this time he also adopted the ] faith. Later, Messiaen felt most at home in the Alps of the ], where he had a house built south of Grenoble. He composed most of his music there.<ref>Hill (1995), pp. 300–301</ref> | |||

| He commenced ] lessons after having already taught himself to play. His interest embraced the recent music of French composers ] and ], and he asked for opera vocal ] for Christmas presents.<ref>Messiaen & Samuel (1994), p. 109</ref> During this period he started to compose. In 1918 his father returned from the war, and the family moved to ]. He continued music lessons; one of his teachers, Jehan de Gibon, gave him a score of Debussy's opera '']'', which Messiaen described as "a thunderbolt" and "probably the most decisive influence on me".<ref>Messiaen & Samuel (1994), p. 110</ref> The following year Pierre Messiaen gained a teaching post in Paris, and the family moved there. Messiaen entered the Paris Conservatoire in 1919, aged 11. | |||

| Messiaen took piano lessons, having already taught himself to play. His interests included the recent music of French composers ] and ], and he asked for opera vocal scores for Christmas presents.<ref>Messiaen & Samuel (1994), p. 109</ref> He also saved to buy scores, including ]'s '']'', whose "beautiful Norwegian melodic lines with the taste of folk song ... gave me a love of melody".<ref>Christopher Dingle, ''The Life of Messiaen'' (London: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 7.</ref> Around this time he began to compose. | |||

| At the Conservatoire Messiaen made excellent academic progress, many times finding himself top of the class. In 1924, aged 15, he was awarded second prize in harmony, in 1926 he gained first prize in ] and ], and in 1927 he won first prize in piano ]. In 1928, after studying with ], he was awarded first prize for the history of music. Emmanuel's example engendered in Messiaen an interest in ancient Greek rhythms and exotic modes. After showing ] skills on the piano Messiaen began to study the ] with ], and from him he inherited the tradition of great French organists (Dupré had studied with Charles-Marie Widor and ]; Vierne in turn was a pupil of ]). Messiaen gained first prize in organ playing and improvisation in 1929. After a year studying composition with ],<ref>Hill & Simeone (2005), p. 20</ref> in the autumn of 1927 he entered the class of the newly appointed ] who instilled in Messiaen mastery of ], and in 1930 Messiaen won first prize in composition. | |||

| In 1918 his father returned from the war and the family moved to ]. Messiaen continued music lessons; one of his teachers, Jehan de Gibon, gave him a score of Debussy's opera {{lang|fr|]}}, which Messiaen called "a thunderbolt" and "probably the most decisive influence on me".<ref>Messiaen & Samuel (1994), p. 110</ref> The next year, his father gained a teaching post at ] in Paris. Olivier entered the ] in 1919, aged 11.<ref>Hill & Simeone (2005), p. 16</ref> | |||

| While he was a student he composed his first published compositions, his eight ''Préludes'' for piano (the earlier ''Le banquet céleste'' was published subsequently). These already exhibit Messiaen's use of his preferred ] and ] rhythms (Messiaen called these '']s''). His public debut came in 1931 with his orchestral suite ''Les offrandes oubliées''. Also in that year he first heard a ] group, which sparked his interest in the use of tuned percussion. | |||

| ] | |||

| ===La Trinité, ''La Jeune France'', and Messiaen's war=== | |||

| Messiaen's special relationship with his ] began in autumn 1927, when he joined Dupré's organ course. Dupré later reminisced that Messiaen, having never seen an organ console before, sat quietly for an hour while Dupré explained and demonstrated the instrument, and then came back a week later to play ]'s ''Fantasia in C minor'' to an impressive standard.<ref>Hill & Simeone (2005), p. 22</ref> From 1929 Messiaen regularly deputised for the organist at the ] in Paris, ], who was ill. When Quef died in 1931 and the post became vacant, Dupré, ] and Widor among others supported Messiaen's candidacy to succeed him. With his formal application Messiaen enclosed a letter of recommendation from Widor, and the appointment was confirmed in 1931.<ref>Hill & Simeone (2005), pp. 34ff</ref> Messiaen remained the organist at la Sainte-Trinité for more than sixty years. | |||

| Messiaen made excellent academic progress at the Conservatoire. In 1924, aged 15, he was awarded second prize in ], having been taught in that subject by professor ]. In 1925, he won first prize in piano ], and in 1926 he gained first prize in ]. After studying with Maurice Emmanuel, he was awarded second prize for the history of music in 1928.<ref>Hill & Simeone (2005), pp. 16–17</ref> Emmanuel's example engendered an interest in ancient Greek rhythms and exotic modes.<ref name=sj10>Sherlaw Johnson (1975), p. 10</ref> After showing improvisational skills on the piano, Messiaen studied organ with Marcel Dupré.<ref>Bannister (2013), p. 171</ref> He won first prize in organ playing and improvisation in 1929.<ref name="sj10"/> After a year studying composition with Charles-Marie Widor, in autumn 1927 he entered the class of the newly appointed Paul Dukas. Messiaen's mother died of tuberculosis shortly before the class began.<ref>Hill & Simeone (2005), p. 20</ref> Despite his grief, he resumed his studies, and in 1930 Messiaen won first prize in composition.<ref name="sj10"/> | |||

| In 1932, Messiaen married the violinist and fellow composer ]. Their marriage inspired him to compose works for her to play (''Thème et variations'' for violin and piano in the year they were married), and pieces to celebrate their domestic happiness (including the ] ''Poèmes pour Mi'' in 1936, which Messiaen orchestrated in 1937). ''Mi'' was Messiaen's affectionate nickname for his wife. In 1937 their son Pascal was born. Messiaen's marriage turned to tragedy when his wife lost her memory after an operation, and she spent the rest of her life in mental institutions.<ref>Yvonne Loriod, in Hill (1995), p. 294</ref> | |||

| While a student he composed his first published works—his eight '']'' for piano (the earlier '']'' was published subsequently). These exhibit Messiaen's use of his modes of limited transposition and ] rhythms (Messiaen called these '']s''). His official début came in 1931 with his orchestral suite ''Les offrandes oubliées''. That year he first heard a ] group, sparking his interest in the use of tuned percussion.<ref>For further discussion of Messiaen's youth, see, generally, Hill & Simeone (2005)</ref> | |||

| In 1936, Messiaen, ], ] and ] formed the group ''La Jeune France'' ("Young France"). Their manifesto implicitly attacked the frivolity predominant in contemporary Parisian music, rejecting ]'s manifesto ''Le coq et l'arlequin'' of 1918 in favour of a "living music, having the impetus of sincerity, generosity and artistic conscientiousness".<ref>from the programme for the opening concert of ''La Jeune France'', quoted in Griffiths (1985), p. 72</ref> Messiaen's career soon departed from this public phase, however, as the music he was composing at this time was not for public commissions or conventional concerts. | |||

| ===La Trinité, ''La jeune France'', and Messiaen's war=== | |||

| In 1937, in response to a commission for a piece to accompany light- and water-shows on ] during the '']'', Messiaen demonstrated his interest in using the ], an electronic instrument, by composing the unpublished ''Fêtes des belles eaux'' for an ensemble of six.<ref>Hill & Simeone (2005), pp. 73f</ref> He included a part for the instrument in many of his subsequent compositions. | |||

| ], where Messiaen was titular organist for 61 years]] | |||

| In the autumn of 1927, Messiaen joined Dupré's organ course. Dupré later wrote that Messiaen, having never seen an organ console, sat quietly for an hour while Dupré explained and demonstrated the instrument, and then came back a week later to play ]'s '']'' to an impressive standard.<ref>Hill & Simeone (2005), p. 22</ref> From 1929, Messiaen regularly deputised at the Église de la Sainte-Trinité for the ailing ]. The post became vacant in 1931 when Quef died, and Dupré, ] and Widor among others supported Messiaen's candidacy. His formal application included a letter of recommendation from Widor. The appointment was confirmed in 1931,<ref>Hill & Simeone (2005), pp. 34–37</ref> and he remained the organist at the church for more than 60 years.<ref>Heller (2010), p. 68</ref> He also assumed a post at the Schola Cantorum de Paris in the early 1930s.<ref>Dingle (2007), p. 45</ref> In 1932, he composed the '']'' for organ.<ref>Gillock (2009), p. 32</ref> | |||

| During this period Messiaen composed organ cycles, for himself to play. He arranged his orchestral suite ''L'Ascension'' for organ, replacing the orchestral version's third movement with an entirely new movement, one of Messiaen's most popular, ''Transports de joie d'une âme devant la gloire du Christ qui est la sienne'' ("Ecstasies of a soul before the glory of Christ, which is its own glory", usually just known as ''Transports de joie'' - {{Audio|Messiaen-ascension-3-latry.ogg|listen}}). He also wrote the extensive cycles ''La Nativité du Seigneur'' and ''Les corps glorieux''. The final ] of ''La Nativité'', ''Dieu parmi nous'' ("God among us") has become another favourite recital piece, often played separately. | |||

| ] | |||

| He also married the violinist and composer ] (daughter of ]) that year. Their marriage inspired him both to compose works for her to play (''Thème et variations'' for violin and piano in the year they were married) and to write pieces to celebrate their domestic happiness, including the song cycle '']'' in 1936, which he orchestrated in 1937. ''Mi'' was Messiaen's affectionate nickname for his wife.<ref>Sherlaw Johnson (1975), pp. 56–57</ref> On 14 July 1937, the Messiaens' son, Pascal Emmanuel, was born; Messiaen celebrated the occasion by writing ].<ref>Gillock (2009), p. 381</ref> The marriage turned tragic when Delbos lost her memory after an operation toward the end of World War II. She spent the rest of her life in mental institutions.<ref>Yvonne Loriod, in Hill (1995), p. 294</ref> | |||

| In 1934, Messiaen released his first major work for organ, ]. He wrote a followup four years later, ]; it premièred in 1945. | |||

| At the outbreak of ] Messiaen was called up into the French army, as a medical auxiliary rather than an active combatant due to his poor eyesight.<ref>Griffiths (1985), p. 139</ref> In May 1940 he was captured at Verdun, and was taken to ] where he was imprisoned at prison camp ]. He soon encountered a violinist, a cellist, and a clarinettist among his fellow prisoners. Initially he wrote a trio for them, but gradually incorporated this trio into his '']'' ("Quartet for the End of Time"). This was first performed in the camp to an audience of prisoners and prison guards, the composer playing a poorly maintained upright piano, in freezing conditions in January 1941. Thus the enforced introspection and reflection of camp life bore fruit in one of 20th-century European classical music's acknowledged masterpieces. The "end of time" of the title is not purely an allusion to the ], the work's ostensible subject, but also refers to the way in which Messiaen, through rhythm and harmony, used time in a way completely different from the music of his predecessors or contemporaries.<ref>See extended discussion in Griffiths (1985), Chapter 6: ''A Technique for the End of Time'', particularly pp. 104-106</ref> | |||

| In 1936, along with ], ] and ], Messiaen formed the group '']'' ("Young France"). Their manifesto implicitly attacked the frivolity predominant in contemporary Parisian music and rejected ]'s 1918 ''Le coq et l'arlequin'' in favour of a "living music, having the impetus of sincerity, generosity and artistic conscientiousness".<ref>From the programme for the opening concert of ''La jeune France'', quoted in Griffiths (1985), p. 72</ref> Messiaen's career soon departed from this polemical phase. | |||

| ===Tristan and serialism=== | |||

| Shortly after his release from Görlitz in May 1941, Messiaen was appointed a professor of harmony at the Paris Conservatoire, where he taught until his retirement in 1978. He also compiled his ''Technique de mon langage musical'' ("Technique of my musical language") published in 1944, in which he quotes many examples from his music, particularly the Quartet. | |||

| In response to a commission for a piece to accompany light-and-water shows on ] during the '']'', in 1937 Messiaen demonstrated his interest in using the ], an electronic instrument, by composing '']'' for an ensemble of six.<ref>Hill & Simeone (2005), pp. 73–75</ref> He included a part for the instrument in several of his subsequent compositions.<ref>Dingle (2013), p. 34</ref> | |||

| Among Messiaen's early students at the Conservatoire were the composer ] and the pianist ]. ] later included ] in 1952, and George Benjamin in the second half of the 1970s. The Greek ] was briefly referred to him in 1951; Messiaen provided encouragement and exhorted Xenakis to take advantage of his background in mathematics and architecture, and use them in his music. Although Messiaen was only in his mid-thirties his students of the period later reported that he was already an outstanding teacher,<ref>Pierre Boulez in Hill (1995), pp. 266ff</ref> encouraging each of them to find their own voice rather than imposing his own ideas. | |||

| ] (1937)]] | |||

| In 1943, Messiaen wrote ''Visions de l'Amen'' ("Visions of the Amen") for two pianos for Loriod and himself to perform, and shortly afterwards composed the enormous solo piano cycle '']'' ("Twenty gazes on the child Jesus") for her. He also wrote ''Trois petites liturgies de la Présence Divine'' ("Three small liturgies of the Divine Presence") for female chorus and orchestra which includes a difficult solo piano part, again for Loriod. Messiaen thus continued to bring liturgical subjects into the piano recital and the concert hall. | |||

| During this period he composed several multi-movement organ works. He arranged his orchestral suite '']'' for organ, replacing the orchestral version's third movement with an entirely new movement, ''Transports de joie d'une âme devant la gloire du Christ qui est la sienne'' ("Ecstasies of a soul before the glory of Christ which is the soul's own") ({{Audio|Messiaen-ascension-3-latry.ogg|listen}}).<ref>Benitez (2008), p. 288</ref> He also wrote the extensive cycles '']'' ("The Nativity of the Lord") and ''Les Corps glorieux'' ("The glorious bodies").<ref>Hill & Simeone (2005), p. 115</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| Two years after ''Visions de l'Amen,'' in 1945, Messiaen composed the first of three works on the theme of human (as opposed to divine) love, particularly inspired by the legend of ] and ]. This was the song cycle ''Harawi''. The second of the ''Tristan'' works was the result of a commission from ] for a piece (Messiaen stated that the commission did not specify the length of the work or the size of the orchestra); this was the ten-movement '']''. This is not a conventional ], but rather an extended meditation on the joy of human love and union. It lacks the sexual guilt inherent in, say, ]'s '']'', because Messiaen's attitude was that sexual love is a divine gift.<ref>Griffiths (1985), p. 139</ref> (''{{Audio|Joiedusang.ogg|listen}}'') The third piece inspired by the ''Tristan'' myth was ''Cinq rechants'' for twelve unaccompanied singers, which Messiaen said was influenced by the ] of the ]s.<ref>Griffiths (1985), p. 142</ref> | |||

| At the outbreak of World War II, Messiaen was drafted into the French army. Due to poor eyesight, he was enlisted as a medical auxiliary rather than an active combatant.<ref name="Griffiths (1985), p. 139">Griffiths (1985), p. 139</ref> He was captured at ], where he befriended clarinettist ]; they were taken to ] in May 1940, and imprisoned at ]. He met a cellist (]) and a violinist ({{ill|Jean le Boulaire|fr|Jean Lanier}}) among his fellow prisoners. He wrote a trio for them, which he gradually incorporated into a more expansive new work, '']'' ("Quartet for the End of Time").<ref name=":0">{{Cite book |last=Brown |first=Kellie D. |title=The sound of hope: Music as solace, resistance and salvation during the holocaust and world war II |publisher=McFarland |year=2020 |isbn=978-1-4766-7056-0 |pages=168–175}}</ref> With the help of a friendly German guard, {{ill|Carl-Albert Brüll|de}}, he acquired manuscript paper and pencils.<ref>{{cite magazine |url=http://www.therestisnoise.com/2004/04/quartet_for_the_2.html |title=The Rest Is Noise: Messiaen's Quartet for the End of Time |first=Alex |last=Ross |author-link=Alex Ross (music critic) |magazine=] |date=22 March 2004|access-date=17 May 2012}}</ref> The work was first performed in January 1941 to an audience of prisoners and prison guards, with the composer playing a poorly maintained upright piano in freezing conditions and the trio playing third-hand unkempt instruments.<ref>Rischin (2003), p. 5</ref> The enforced introspection and reflection of camp life bore fruit in one of 20th-century classical music's acknowledged masterpieces. The title's "end of time" alludes to the ], and also to the way that Messiaen, through rhythm and harmony, used time in a manner completely different from his predecessors and contemporaries.<ref>See extended discussion in Griffiths (1985), Chapter 6: ''A Technique for the End of Time'', particularly pp. 104–106</ref> | |||

| Messiaen visited the ] in 1947, his music being conducted there by Koussevitsky and ], and his ''Turangalîla-Symphonie'' was first performed there in 1949 conducted by ]. During this period, as well as giving an ] class at the Paris Conservatoire, he also taught in ] in 1947 and ] in 1949; in the summers of 1949 and 1950 he taught in the ] classes at ]. Though he never employed ] himself, after three years teaching analysis of scores using it, such as works by ], he did experiment with ways of making scales of other elements (including duration, articulation, and dynamics) analogous to the chromatic pitch scale. The results of these innovations was the piece "Mode de valeurs et d'intensités" for piano (from the ''Quatre Études de Rhythme'') which has been incorrectly described as the first work of ], though it had a large influence on the earliest European serial composers, including ], ], and ]. During this period he also experimented with ], music for recorded sounds. | |||

| The idea of a European Centre of Education and Culture "Meeting Point Music Messiaen" on the site of Stalag VIII-A, for children and youth, artists, musicians and everyone in the region emerged in December 2004, was developed with the involvement of Messiaen's widow as a joint project between the council districts in Germany and Poland, and was completed in 2014.<ref>{{cite web | title=European Center Memory, Education, Culture | website=Meetingpoint Music Messiaen e.V. | date=17 April 2020 | url=https://www.meetingpoint-music-messiaen.net/en/european-center-memory-education-culture/ | access-date=27 May 2020}}</ref> | |||

| ===''Tristan'' and serialism=== | |||

| {{See also|List of students of Olivier Messiaen}} | |||

| Shortly after his release from Görlitz in May 1941 in large part due to the persuasions of his friend and teacher ], Messiaen, who was now a household name, was appointed a professor of harmony at the Paris Conservatoire, where he taught until retiring in 1978.<ref>Benitez (2008), p. 155</ref> He compiled his ''Technique de mon langage musical'' ("Technique of my musical language") published in 1944, in which he quotes many examples from his music, particularly the Quartet.<ref>Benitez (2008), p. 33</ref> Although only in his mid-thirties, his students described him as an outstanding teacher.<ref>Pierre Boulez in Hill (1995), pp. 266ff</ref> Among his early students were the composers ] and ]. Other pupils included ] in 1952, ] in 1956–57, ] in 1962-63, ] in 1967–72 and ] during the late 1970s.<ref>Benitez (2008), p. xiii</ref> The Greek composer Iannis Xenakis was referred to him in 1951; Messiaen urged Xenakis to take advantage of his background in mathematics and architecture in his music.<ref>Matossian (1986), p. 48</ref> | |||

| In 1943, Messiaen wrote '']'' ("Visions of the Amen") for two pianos for ] and himself to perform. Shortly thereafter he composed the enormous solo piano cycle '']'' ("Twenty gazes upon the child Jesus") for her.<ref>Sherlaw Johnson (1975), pp. 11, 64</ref> Again for Loriod, he wrote '']'' ("Three small liturgies of the Divine Presence") for female chorus and orchestra, which includes a difficult solo piano part.<ref>Hill & Simeone (2007), p. 21</ref> | |||

| Two years after ''Visions de l'Amen'', Messiaen composed the song cycle '']'', the first of three works inspired by the legend of ] and ]. The second of these works about human (as opposed to divine) love was the result of a commission from ]. Messiaen said the commission did not specify the length of the work or the size of the orchestra. This was the ten-movement '']''. It is not a conventional ], but rather an extended meditation on the joy of human union and love. It does not contain the sexual guilt inherent in ]'s '']'' because Messiaen believed sexual love to be a divine gift.<ref name="Griffiths (1985), p. 139"/> The third piece inspired by the ''Tristan'' myth was ''Cinq rechants'' for 12 unaccompanied singers, described by Messiaen as influenced by the ] of the ]s.<ref>Griffiths (1985), p. 142</ref> Messiaen visited the United States in 1949, where his music was conducted by Koussevitsky and ]. His ''Turangalîla-Symphonie'' was first performed in the US the same year, conducted by ].<ref>Hill & Simeone (2005), pp. 186–192</ref> | |||

| Messiaen taught an ] class at the Paris Conservatoire. In 1947 he taught (and performed with Loriod) for two weeks in ].<ref>Benitez (2008), p. 3</ref> In 1949 he taught at ]<ref>Hill & Simeone (2005), p. 415</ref> and presented his work at the ].<ref>Iddon (2013), p. 31</ref> While he did not employ the ], after three years teaching analysis of twelve-tone scores, including works by ], he experimented with ways of making scales of other elements (including duration, articulation and dynamics) analogous to the ]. The results of these innovations was the "Mode de valeurs et d'intensités" for piano (from the '']'')<ref>Sherlaw Johnson (1975), p. 104</ref> which has been misleadingly described as the first work of "]". It had a large influence on the earliest European serial composers, including Boulez and Stockhausen.<ref>Sherlaw Johnson (1975), pp. 192–194</ref> During this period he also experimented with ], music for recorded sounds.<ref>Hill & Simeone (2005), p. 198</ref> | |||

| ===Birdsong and the 1960s=== | ===Birdsong and the 1960s=== | ||

| When in 1952 Messiaen was asked to provide a test piece for flautists at the Paris Conservatoire, he composed the piece {{lang|fr|]}} for flute and piano. While he had long been fascinated by birdsong, and birds had made appearances in several of his earlier works (for example {{lang|fr|La Nativité}}, {{lang|fr|Quatuor}} and {{lang|fr|Vingt regards}}), the flute piece was based entirely on the song of the ].<ref>Dingle (2007), p. 139. For a general discussion of Messiaen's fusion of birdsong and music, see Hill & Simeone (2007)</ref> | |||

| He took this development to a new level with his 1953 orchestral work {{lang|fr|]}}—its material consists almost entirely of the birdsong one might hear between midnight and noon in the ].<ref>Hill & Simeone (2007), p. 27</ref> From this period onward, Messiaen incorporated birdsong into his compositions and composed several works for which birds provide both the title and subject matter (for example the collection of 13 piano pieces {{lang|fr|]}} completed in 1958, and {{lang|fr|La fauvette des jardins}} of 1971).<ref>Kraft (2013)</ref> ] observed that Messiaen was a more conscientious ornithologist than any previous composer, and a more musical observer of birdsong than any previous ornithologist.<ref>Griffiths (1985), p. 168; see also Kraft (2013)</ref> | |||

| Messiaen's first wife died in 1959 following her long illness, and in 1961 he married Yvonne Loriod. He began to travel widely, both to attend musical events and to seek out and transcribe the songs of more exotic birds. Loriod frequently assisted her husband's detailed studies of birdsongs, which he notated in the wild, by walking with him and making a ] for checking later. In 1962 his travels took him to ], where ] music and ] theatre inspired him to compose the orchestral "Japanese sketches", ''Sept haïkaï'', which contain stylised imitations of traditional Japanese instruments. | |||

| ] | |||

| Messiaen's music was at this time championed by, among others, Pierre Boulez, who programmed first performances at his ] concerts and the ] festival. Works performed here included ''Réveil des oiseaux'', ''Chronochromie'' (commissioned for the 1960 festival) and ''Couleurs de la cité céleste''. The latter piece was the result of a commission for a composition for three ]s and three ]s; Messiaen added to this more brass, wind, percussion and piano, and specified a xylophone, ] and ] rather than three xylophones. Another work of this period, ''Et expecto resurrectionem mortuorem'', was commissioned as a commemoration of the dead of the two World Wars, and was performed first semi-privately in the ], then publicly in ] with ] in the audience. | |||

| Messiaen's first wife died in 1959 after a long illness, and in 1961 he married Loriod.<ref>Benitez (2008), p. 4</ref> He began to travel widely, to attend musical events and to seek out and transcribe the songs of more exotic birds in the wild. Despite this, he spoke only French. Loriod frequently assisted her husband's detailed studies of birdsong while walking with him, by making tape recordings for later reference.<ref>Benitez (2008), p. 138</ref> In 1962 he visited Japan, where ] music and ] theatre inspired the orchestral "Japanese sketches", {{lang|fr|]}}, which contain stylised imitations of traditional Japanese instruments.<ref>Messiaen's visit to Japan is documented in Hill & Simeone (2005), pp. 245–251, and there is a more technical discussion in Griffiths (1985), pp. 197–200. ], writing in Hill (1995), additionally notes the direct influence of Noh theatre on aspects of Messiaen's opera ''St François d'Assise''.</ref> | |||

| Messiaen's music was by this time championed by, among others, Boulez, who programmed first performances at his ] concerts and the ] festival.<ref>Benitez (2008), p. 280</ref> Works performed included {{lang|fr|Réveil des oiseaux}}, {{lang|fr|]}} (commissioned for the 1960 festival), and {{lang|fr|Couleurs de la cité céleste}}. The latter piece was the result of a commission for a composition for three trombones and three ]s; Messiaen added to this more brass, wind, percussion and piano, and specified a xylophone, ] and ] rather than three xylophones.<ref>Sherlaw Johnson (1975), p. 166</ref> Another work of this period, {{lang|la|]}}, was commissioned as a commemoration of the dead of the two World Wars and was performed first semi-privately in the ], then publicly in ] with ] in the audience.<ref>Simeone (2009), pp. 185–195</ref> | |||

| His reputation as a composer continued to grow. In 1959 Messiaen was nominated as an ''Officier'' of the '']'',<ref>Hill & Simeone (2005), p. 245</ref> and in 1966 he was officially appointed professor of composition at the Paris Conservatoire (although he had in effect been teaching composition for years). Further honours bestowed on Messiaen later included election to the ] in 1967, the ] in 1971, the award of the ] Gold Medal in 1975, and the presentation of the ''Croix de Commander'' of the ] ] in 1980.<ref>Hill & Simeone (2005), p. 333</ref> | |||

| His reputation as a composer continued to grow and in 1959, he was nominated as an {{lang|fr|Officier}} of the {{lang|fr|]}}.<ref>Hill & Simeone (2005), p. 245</ref> In 1966, he was officially appointed professor of composition at the Paris Conservatoire, although he had in effect been teaching composition for years.<ref>Hill & Simeone (2005), p. 306</ref> Further honours included election to the ] in 1967 and the ] in 1968, the ] in 1971, the award of the ] Gold Medal and the ] in 1975, the ] (Denmark's highest musical honour) in 1977, the ] in 1982, and the presentation of the {{lang|fr|Croix de Commander}} of the Belgian ] in 1980.<ref>Hill & Simeone (2005), p. 333</ref> | |||

| ===Transfiguration, Canyons, St. Francis, and the Beyond=== | |||

| Messiaen's next work was the enormous ''La Transfiguration de Notre-Seigneur Jésus-Christ''. This composition occupied Messiaen from 1965 to 1969 and the forces employed include a 100-voice ten-part choir, seven solo instruments and a large orchestra. Its fourteen movements are a meditation on the story of Christ's ]. Shortly afterwards Messiaen received a commission from the American ] for a work to celebrate the bicentenary of the ]. He arranged a visit to the USA in spring 1972, and was inspired by ] in ], where he noted the canyon's distinctive colours and birdsongs.<ref>Griffiths (1985), p. 225</ref> The ten-movement orchestral piece ''Des Canyons aux étoiles…'' was the result, which was first performed in 1974 in New York. | |||

| ===''Transfiguration'', ''Canyons'', ''St. Francis'', and ''the Beyond''=== | |||

| Messiaen had been asked as early as 1971 for a piece for the ]. Initially reluctant to undertake such a major project, in 1975 Messiaen was finally persuaded to accept the commission and began work on his '']''. Composition of this work was an intensive task (he also wrote his own ]), occupying him during the period 1975–79, and then the orchestration was carried out from 1979 until 1983.<ref>programme for Opéra de la Bastille production of ''St. François d'Assise'', p. 18</ref> The work (which Messiaen preferred to call a "spectacle" rather than an ]) was first performed in 1983. Some commentators at the time of its first production thought that Messiaen's opera would be his valediction (indeed, at times Messiaen himself believed so<ref>The composer in conversation with Jean-Cristophe Marti in 1992, see p. 29 of booklet accompanying the recording of ''Saint-François d'Assise'' conducted by ] on Deutsche Grammophon 445176-2; see also Hill & Simeone (2005), pp. 340 and 342</ref>), but he continued composing, bringing out a major collection of organ pieces, ''Livre du Saint Sacrement'', in 1984, as well as further bird pieces for solo piano and pieces for piano with orchestra. | |||

| Messiaen's next work was the large-scale '']''. The composition occupied him from 1965 to 1969 and the musicians employed include a 100-voice ten-part choir, seven solo instruments and large orchestra. Its fourteen movements are a meditation on the story of Christ's ].<ref>Bruhn (2008), pp. 57–96</ref> Shortly after its completion, Messiaen received a commission from ] for a work to celebrate the ]. He arranged a visit to the U.S. in spring 1972, and was inspired by ] in ], where he observed the canyon's distinctive colours and birdsong.<ref>Griffiths (1985), p. 225</ref> The 12-movement orchestral piece '']'' was the result, first performed in 1974 in New York.<ref>Hill & Simeone (2005), p. 301</ref> | |||

| ], an electronic instrument, for which Messiaen included a part in several of his compositions: the orchestra for his opera '']'' includes three of them]] | |||

| Messiaen had retired from teaching at the Conservatoire in the summer of 1978. In 1987 he was promoted to the highest rank, ''Grand-Croix'', of the ''Légion d'honneur''.<ref>Hill & Simeone (2005), p. 357</ref> An operation prevented his participating in events to celebrate his 70th birthday, but in 1988 tributes for Messiaen's 80th birthday around the globe included a complete performance in ]'s ] of ''St. François'', which the composer attended, and Erato's publication of a seventeen-CD collection of Messiaen's music including recordings by Loriod and a disc of the composer in conversation with ]. | |||

| In 1971, he was asked to compose a piece for the ]. Reluctant to take on such a major project, he was persuaded by French president ] to accept the commission and began work on '']'' in 1975 after two years of preparation. The composition was intensive (he also wrote his own ]) and occupied him from 1975 to 1979; the orchestration was carried out from 1979 until 1983.<ref>Programme for Opéra de la Bastille production of ''St. François d'Assise'', p. 18</ref> Messiaen preferred to describe the final work as a "spectacle" rather than an opera. It was first performed in 1983. Some commentators at the time thought that the opera would be his valediction (at times Messiaen himself believed so),<ref>The composer in conversation with Jean-Cristophe Marti in 1992, see p. 29 of booklet accompanying the recording of ''Saint-François d'Assise'' conducted by ] on Deutsche Grammophon/PolyGram 445 176; see also Hill & Simeone (2005), pp. 340 and 342</ref> but he continued to compose. In 1984, he published a major collection of organ pieces, ''Livre du Saint Sacrement''; other works include birdsong pieces for solo piano, and works for piano with orchestra.<ref>Dingle (2013)</ref> | |||

| In the summer of 1978, Messiaen was forced to retire from teaching at the Paris Conservatoire due to French law. He was promoted to the highest rank of the ''Légion d'honneur'', the ''Grand-Croix'', in 1987, and was awarded the decoration in London by his old friend ].<ref>Hill & Simeone (2005), p. 357</ref> An operation prevented his participation in the celebration of his 70th birthday in 1978,<ref>Dingle (2007), p. 207</ref> but in 1988 tributes for Messiaen's 80th included a complete performance in London's ] of ''St. François'', which the composer attended,<ref>Hill & Simeone (2005), p. 371</ref> and ]'s publication of a 17-CD collection of his music, including a disc of Messiaen in conversation with ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.arkivmusic.com/albumpage/128304-E1120|access-date=8 September 2013|publisher=ArkivMusic|title=Messiaen Edition|archive-date=4 March 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160304042938/http://www.arkivmusic.com/albumpage/128304-E1120|url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| Messiaen's last composition resulted from a commission from the New York Philharmonic Orchestra; although he was in considerable pain near the end of his life (requiring repeated surgery on his back<ref>Yvonne Loriod, in Hill (1995), p. 302</ref>) he was able to complete ''Eclairs sur l'au delà'', which premiered six months after the composer's death. Messiaen had also been composing a concerto for four musicians he felt particularly grateful to, namely Loriod, the ] ], the ] ] and the flautist ]. This was substantially complete when Messiaen died, and Yvonne Loriod undertook the final movement's orchestration with advice from George Benjamin. | |||

| Although in considerable pain near the end of his life (requiring repeated surgery on his back),<ref>Yvonne Loriod, in Hill (1995), p. 302</ref> he was able to fulfil a commission from the New York Philharmonic Orchestra, '']'', which premièred six months after his death. He died in the ] in ] on 27 April 1992, aged 83.<ref>Gillock (2009), p. 383</ref> | |||

| On going through his papers, Loriod discovered that, in the last months of his life, he had been composing a ] for four musicians he felt particularly grateful to: herself, the cellist ], the ] ] and the flautist Catherine Cantin<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://musicalworld.com/artists/catherine-cantin/|title=Catherine Cantin, Flutist - MusicalWorld.com|website=musicalworld.com|access-date=26 June 2018|archive-date=4 June 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190604173136/http://musicalworld.com/artists/catherine-cantin/|url-status=dead}}</ref> (hence the title ''Concert à quatre''). Four of the five intended movements were substantially complete; Loriod undertook the orchestration of the second half of the first movement and of the whole of the fourth with advice from George Benjamin. It was premiered by the dedicatees in September 1994.<ref>Dingle (2013), pp. 293–310</ref> | |||

| ==Music== | ==Music== | ||

| {{See also|List of compositions by Olivier Messiaen}} | |||

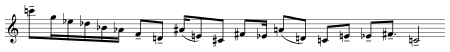

| ] (''garralaxe à huppe blanche'') in the ] and ] instruments, and the ] (''troupiale des vergers'') played on the xylophone.]] | |||

| ]" and "]" are ancient Greek rhythms, and Nibçankalîla is a decî-tâla from Śārṅgadeva). It also illustrates Messiaen's precision in notating birdsong: the birds identified here are the ] (''garralaxe à huppe blanche'') in the ] and ] instruments, and the ] (''troupiale des vergers'') played on the xylophone.]] | |||

| It is almost impossible to mistake a Messiaen composition for the work of any other ] classical composer. His music has been described as outside the western musical tradition, although growing out of that tradition and influenced by it.<ref>Griffiths (1985) p. 15</ref> Much of Messiaen's output denies the western conventions of forward motion, ] and ] harmonic resolution. This is partly due to the ] of his technique — for instance the modes of limited transposition do not admit the conventional ] found in western classical music. | |||

| Messiaen's music has been described as outside the western musical tradition, although growing out of that tradition and being influenced by it.<ref>Griffiths (1985), p. 15</ref> Much of his output denies the western conventions of forward motion, ] and ] harmonic resolution. This is partly due to the symmetries of his technique—for instance the modes of limited transposition do not admit the conventional ] found in western classical music.<ref name=intro>Griffiths (1985), Introduction</ref> | |||

| Messiaen's youthful |

" fascination with Shakespeare's depiction of human passion and with his magical world also influenced the composer's later works."<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.schott-music.com/shop/persons/az/olivier-messiaen/index.html|access-date=8 September 2013|publisher=Schott Music|title=Olivier Messiaen|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://archive.today/20130908181716/http://www.schott-music.com/shop/persons/az/olivier-messiaen/index.html|archive-date=8 September 2013}}</ref> Messiaen was not interested in depicting aspects of theology such as ];<ref>Messiaen & Samuel (1994), p. 213</ref> rather he concentrated on the theology of joy, ] and ].<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Bruhn|first1=Siglind|author1-link=Siglind Bruhn|last2=Deely|first2=John|author2-link=John Deely|title=Religious Symbolism in the Music of Olivier Messiaen|journal=]|date=January 1996|volume=13|issue=1|pages=277–309|doi=10.5840/ajs1996131/412}}</ref> | ||

| Messiaen continually evolved new composition techniques, always integrating them into his existing musical style; his final works still retain the use of modes of limited transposition.<ref name=intro/> For many commentators this continual development made every ''major'' work from the ''Quatuor'' onwards a conscious summation of all that Messiaen had composed up to that time. But very few of these works lack new technical ideas—simple examples being the introduction of communicable language in ''Meditations'', the invention of a new percussion instrument (the ]) for ''Des canyons aux etoiles...'', and the freedom from any synchronisation with the main pulse of individual parts in certain birdsong episodes of ''St. François d'Assise''.<ref>See for instance Griffiths (1985), p. 233, " is therefore not so much a synthesis, as has sometimes been suggested, but more a step into the future that also joins the circle with the composer's past."</ref> | |||

| As well as discovering new techniques |

As well as discovering new techniques, Messiaen studied and absorbed foreign music, including Ancient Greek rhythms,<ref name=sj10/> ] rhythms (he encountered ]'s list of 120 ], the deçî-tâlas),<ref>Messiaen & Samuel (1994), p. 77</ref> Balinese and Javanese Gamelan, birdsong, and Japanese music (see ''Example 1'' for an instance of his use of ancient Greek and Hindu rhythms).<ref>{{cite web|url=http://americamagazine.org/issue/677/article/maestro-joy|access-date=8 September 2013|work=America: the National Catholic Review|title=Maestro of Joy|author=Coleman, John|date=24 November 2008}}</ref> | ||

| While he was instrumental in the academic exploration of his techniques (he |

While he was instrumental in the academic exploration of his techniques (he compiled two treatises; the second, in five volumes, was substantially complete when he died and was published posthumously), and was a master of music analysis, he considered the development and study of techniques a means to intellectual, aesthetic, and emotional ends. Thus Messiaen maintained that a musical composition must be measured against three separate criteria: it must be interesting, beautiful to listen to, and touch the listener.<ref name="Messiaen & Samuel (1994), p. 47">Messiaen & Samuel (1994), p. 47</ref> | ||

| Messiaen wrote a large body of music for the piano. Although a considerable pianist himself, he was undoubtedly assisted by |

Messiaen wrote a large body of music for the piano. Although a considerable pianist himself, he was undoubtedly assisted by Loriod's formidable technique and ability to convey complex rhythms and rhythmic combinations; in his piano writing from ''Visions de l'Amen'' onward he had her in mind. Messiaen said, "I am able to allow myself the greatest eccentricities because to her anything is possible."<ref name="Messiaen & Samuel (1994), p. 114">Messiaen & Samuel (1994), p. 114</ref> | ||

| ===Western |

===Western influences=== | ||

| Developments in modern French music were a major influence on Messiaen, particularly the music of |

Developments in modern French music were a major influence on Messiaen, particularly the music of Debussy and his use of the ] (which Messiaen called ''Mode 1'' in his modes of limited transposition). Messiaen rarely used the whole-tone scale in his compositions because, he said, after Debussy and Dukas there was "nothing to add",<ref name="Technique de mon langage musical">Messiaen, ''Technique de mon langage musical''</ref> but the modes he did use are similarly symmetrical. | ||

| Messiaen |

Messiaen had a great admiration for the music of ], particularly the use of rhythm in earlier works such as '']'', and his use of orchestral colour. He was further influenced by the orchestral brilliance of ], who lived in Paris in the 1920s and gave acclaimed concerts there. Among composers for the keyboard, Messiaen singled out ], ], ], Debussy, and ].<ref name="Messiaen & Samuel (1994), p. 114"/> He loved the music of ] and incorporated varied modifications of what he called the "M-shaped" melodic motif from Mussorgsky's '']'',<ref name="Technique de mon langage musical"/> although he modified the final interval from a ] to a ] (''Example 3'').<ref>Bruhn (2008), p. 46</ref> | ||

| Messiaen was |

Messiaen was further influenced by ], as seen in the titles of some of the piano '']'' (''Un reflet dans le vent...'', "A reflection in the wind")<ref>Sherlaw Johnson (1975), p. 26</ref> and in some of the imagery of his poetry (he published poems as prefaces to certain works, for example ''Les offrandes oubliées'').<ref>Sherlaw Johnson (1975), p. 76</ref> | ||

| ===Colour=== | ===Colour=== | ||

| Colour lies at the heart of Messiaen's music. |

Colour lies at the heart of Messiaen's music. He believed that terms such as "]", "]" and "]" are misleading analytical conveniences.<ref>Messiaen & Samuel (1994), pp. 49–50</ref> For him there were no modal, tonal or serial compositions, only music with or without colour.<ref>Messiaen & Samuel (1994), p. 63</ref> He said that ], ], ], ], ], and ] all wrote strongly coloured music.<ref>Messiaen & Samuel (1994), p. 62</ref> | ||

| In some of Messiaen's scores, he notated the colours in the music (notably in ''Couleurs de la cité céleste'' and ''Des canyons aux étoiles...'')—the purpose being to aid the conductor in interpretation rather than to specify which colours the listener should experience. The importance of colour is linked to Messiaen's ], which caused him to experience colours when he heard or imagined music (his form of synaesthesia, the most common form, involved experiencing the associated colours in a non-visual form rather than perceiving them visually). In his multi-volume music theory treatise ''Traité de rythme, de couleur, et d'ornithologie'' ("Treatise of Rhythm, Colour and Birdsong"), Messiaen wrote descriptions of the colours of certain chords. His descriptions range from the simple ("gold and brown") to the highly detailed ("blue-violet rocks, speckled with little grey cubes, ], deep ], highlighted by a bit of violet-purple, gold, red, ruby, and stars of mauve, black and white. Blue-violet is dominant").<ref>See Messiaen, Olivier ''Traité de rythme, de couleur, et d'ornithologie''. See also Bernard, Jonathan W. (1986). "Messiaen's Synaesthesia: The Correspondence between Color and Sound Structure in His Music". '']'' '''4''': 41–68.</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last=Fink |first=Monika |title=Farb-Klänge und Klang-Farben im Werk von Olivier Messiaen |journal=Music in Art: International Journal for Music Iconography |volume=28 |issue=1–2 |date=2003 |pages=163–172 |issn=1522-7464 }}</ref> | |||

| George Benjamin said, when asked what Messiaen's main influence had been on composers, "I think the sheer colour has been so influential, rather than being a decorative element, could be a structural, a fundamental element, the fundamental material of the music itself."<ref>George Benjamin, speaking in interview with Tommy Pearson, broadcast on BBC4 in the interval of ] in 2004 at which Benjamin conducted a performance of ''Des canyons aux étoiles…'' Asked what made Messiaen so influential he said, "I think the sheer—the word he loved—colour has been so influential. People, composers, have found that colour, rather than being a decorative element, could be a structural, a fundamental element. And not colour just in a surface way, not just in the way you orchestrate it—no—the fundamental material of the music itself. More than that I can't say except that for my own small world he was incredibly important, and an exceptionally special and indeed wonderful person. I met him when I was very young (I was 16) and stayed closely in touch with him until he died in 1992, and was immensely fond of him…"</ref> | |||

| When asked what Messiaen's main influence had been on composers, George Benjamin said, "I think the sheer ... colour has been so influential, ... rather than being a decorative element, could be a structural, a fundamental element, ... the fundamental material of the music itself."<ref>George Benjamin, speaking in interview with Tommy Pearson, broadcast on BBC4 in the interval of ] in 2004 at which Benjamin conducted a performance of ''Des canyons aux étoiles...'' Asked what made Messiaen so influential he said, "I think the sheer—the word he loved—colour has been so influential. People, composers, have found that colour, rather than being a decorative element, could be a structural, a fundamental element. And not colour just in a surface way, not just in the way you orchestrate it—no—the fundamental material of the music itself. More than that I can't say except that for my own small world he was incredibly important, and an exceptionally special and indeed wonderful person. I met him when I was very young (I was 16) and stayed closely in touch with him until he died in 1992, and was immensely fond of him..."</ref> | |||

| ===Symmetry=== | |||

| Many of Messiaen's composition techniques made use of symmetries of time and ]. | |||

| ===Symmetry=== | |||

| Many of Messiaen's composition techniques made use of symmetries of time and ].<ref>{{cite journal|last=Benitez|first=Vincent|title=Reconsidering Messiaen as Serialist|journal=Music Analysis|date=July 2009|volume=28|issue=2–3|pages=267–299|doi=10.1111/j.1468-2249.2011.00293.x}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| From his earliest works Messiaen often used non-retrogradable (]) rhythms (''Example 2''). | |||

| ====Time==== | |||

| Messiaen sometimes combined rhythms with harmonic sequences in such a way that if the process were allowed to proceed indefinitely the music would eventually run through all the possible permutations and return to its starting point. For Messiaen, this represented what he termed the "charm of impossibilities" of these processes. In practice, of course, Messiaen only ever presented a portion of any such process, as if allowing the informed listener a glimpse of something eternal. In the first movement of ''Quatuor pour la fin du temps'' the piano and cello together provide an early example. | |||

| ] | |||

| From his earliest works, Messiaen used non-retrogradable (palindromic) rhythms (''Example 2''). He sometimes combined rhythms with harmonic sequences in such a way that, if the process were repeated indefinitely, the music would eventually run through all possible permutations and return to its starting point. For Messiaen, this represented the "charm of impossibilities" of these processes. He only ever presented a portion of any such process, as if allowing the informed listener a glimpse of something eternal. In the first movement of ''Quatuor pour la fin du temps'' the piano and cello together provide an early example.<ref>For discussion, see for example Iain G. Matheson's article "The End of Time" in Hill (1995), particularly pp. 237–243</ref> | |||

| ==== |

====Pitch==== | ||

| Messiaen used modes |

Messiaen used modes he called ''modes of limited transposition''.<ref name=intro/> They are distinguished as groups of notes that can only be ] by a semitone a limited number of times. For example, the whole-tone scale (Messiaen's Mode 1) exists in only two transpositions: C–D–E–F{{music|sharp}}–G{{music|sharp}}–A{{music|sharp}} and D{{music|flat}}–E{{music|flat}}–F–G–A–B. Messiaen abstracted these modes from the harmony of his improvisations and early works.<ref>Hill (1995), p. 17</ref> Music written using the modes avoids conventional diatonic harmonic progressions, since for example Messiaen's Mode 2 (identical to the '']'' used by other composers) permits precisely the ] chords whose tonic the mode does not contain.<ref>Griffiths (1985), p. 32</ref> | ||

| ===Time and rhythm=== | ===Time and rhythm=== | ||

| ]s) to an underlying quaver (]) pulse |

]s) to an underlying quaver (]) pulse and the lengthening of the final quaver by addition of a ]. It illustrates the use of what Messiaen called the ''Boris'' M-shaped motif (the last five notes of the excerpt).]] | ||

| As well as making use of non-retrogradable rhythms and the Hindu decî-tâlas, Messiaen also composed with "additive" rhythms. This involves lengthening individual notes slightly or interpolating a short note into an otherwise regular rhythm (see ''Example 3''), or shortening or lengthening every note of a rhythm by the same duration (adding a semiquaver to every note in a rhythm on its repeat, for example).<ref>Bruhn (2008), pp. 37–49</ref> This led Messiaen to use ]s that irregularly alternate between two and three units, a process that also occurs in Stravinsky's ''The Rite of Spring'', which Messiaen admired.<ref>Dingle & Simeone (2007), p. 48</ref> | |||

| A factor that contributes to Messiaen's suspension of the conventional perception of time in his music is the extremely slow tempos he often specifies (the |

A factor that contributes to Messiaen's suspension of the conventional perception of time in his music is the extremely slow tempos he often specifies (the fifth movement ''Louange à l'eternité de Jésus'' of ''Quatuor'' is actually given the tempo marking ''infiniment lent'').<ref>Pople (1998), p. 82</ref> Messiaen also used the concept of "chromatic durations", for example in his ''Soixante-quatre durées'' from ''Livre d'orgue'' ({{Audio|Messiaen-livre-7-soixante.ogg|listen}}), which is built from, in Messiaen's words, "64 chromatic durations from 1 to 64 demisemiquavers —invested in groups of 4, from the ends to the centre, forwards and backwards alternately—treated as a retrograde canon. The whole peopled with birdsong."<ref>Quoted by ], who discusses the work in Hill (1995) pp. 364–366</ref> | ||

| Messiaen also used the concept of "chromatic durations", for example in his ''Soixante-quatre durées'' from ''Livre d'orgue,'' ({{Audio|Messiaen-livre-7-soixante.ogg|listen}}) which assigns a distinct duration to 64 pitches ranging from long to short and low to high, respectively. | |||

| ===Harmony=== | ===Harmony=== | ||

| ] | ] from ''Le loriot'', part of '']''. The birdsong played by the pianist's left hand (notated on the lower staff) provides the fundamental notes, and the quieter harmonies played by the right hand alter their timbre.]] | ||

| In addition to making harmonic use of the modes of limited transposition, Messiaen cited the ] as a physical phenomenon that gives chords a context he felt was missing in purely serial music.<ref>Messiaen & Samuel (1994), pp. 241–242</ref> An example of Messiaen's use of this phenomenon, which he called "resonance", is the last two bars of his first piano ''Prélude'', ''La colombe'' ("The dove"): the chord is built from harmonics of the fundamental note E.<ref>Griffiths (1985) p. 34</ref> | |||

| Messiaen also composed music in which the lowest, or fundamental, note is combined with higher notes or chords played much more quietly. These higher notes, far from being perceived as conventional harmony, function as harmonics that alter the timbre of the fundamental note like ] on a ].<ref>{{cite journal|last=Benitez|first=Vincent|title=Aspects of Harmony in Messiaen's Later Music: An Examination of the Chords of Transposed Inversions on the Same Bass Note|journal=Journal of Musicological Research|date=April 2004|volume=23|issue=2|pages=187–226|doi=10.1080/01411890490449781|s2cid=191492252}}</ref> An example is the song of the golden oriole in ''Le loriot'' of the '']'' for solo piano (''Example 4''). | |||

| In his use of conventional diatonic chords, Messiaen often transcended their |

In his use of conventional diatonic chords, Messiaen often transcended their historical connotations (for example, with his frequent use of the ] as a ]).<ref>{{cite journal|last=Bruhn|first=Siglind|author-link=Siglind Bruhn|title=Traces of a Thomistic De musica in the Compositions of Olivier Messiaen|journal=]|year=2008|volume=11|issue=4|pages=16–56|doi=10.1353/log.0.0015|s2cid=51268362}}</ref> | ||

| ===Birdsong=== | ===Birdsong=== | ||

| ] provided the title and much of the material for Messiaen's {{lang|fr|La fauvette des jardins}}.]] | |||

| Birdsong fascinated Messiaen from an early age, and in this he found encouragement from his teacher Dukas who reportedly urged his pupils to "listen to the birds". Messiaen included stylised birdsong in some of his early compositions (for example ''L'abîme d'oiseaux'' from the ''Quatuor''), integrating it into his sound-world by techniques like the modes of limited transposition and chord colouration. The birdsong episodes in his work became increasingly sophisticated, and with ''Le Réveil des Oiseaux'' this process reached maturity, the whole piece being built from birdsong: in effect it is a ] for orchestra. Messiaen even notated the bird species with the music in the score (''Examples 1 and 4''). The pieces are not simple transcriptions, however: even the works with purely bird-inspired titles, such as ''Catalogue d'oiseaux'' and ''Fauvette des jardins'', are tone poems evoking the landscape, its colour and its atmosphere. ''({{Audio|Loriot2.ogg|listen}})'' | |||

| Birdsong fascinated Messiaen from an early age, and in this he found encouragement from Dukas, who reportedly urged his pupils to "listen to the birds". Messiaen included stylised birdsong in some of his early compositions (including ''L'abîme d'oiseaux'' from the ''Quatuor pour la fin du temps''), integrating it into his sound-world by techniques like the modes of limited transposition and chord colouration. His evocations of birdsong became increasingly sophisticated, and with ''Le réveil des oiseaux'' this process reached maturity, the whole piece being built from birdsong: in effect it is a ] for orchestra. The same can be said for "Epode", the five-minute sixth movement of ''Chronochromie'', which is scored for 18 violins, each playing a different birdsong. Messiaen notated the bird species with the music in the score (examples 1 and 4). The pieces are not simple transcriptions; even the works with purely bird-inspired titles, such as '']'' and ''Fauvette des jardins'', are tone poems evoking the landscape, its colours and atmosphere.<ref>For extensive discussion of the use of birdsong in Messiaen's work, see Kraft (2013).</ref> | |||

| ===Serialism=== | ===Serialism=== | ||

| For a few compositions, Messiaen created scales for duration, attack and timbre analogous to the chromatic pitch scale. He expressed annoyance at the historical importance given to one of these works, ''Mode de valeurs et d'intensités'', by musicologists intent on crediting him with the invention of "total serialism".<ref name="Messiaen & Samuel (1994), p. 47"/> | |||

| Messiaen later introduced what he called a "communicable language", a "musical alphabet" to encode sentences. He first used this technique in his '']'' for organ; where the "alphabet" includes motifs for the concepts ''to have'', ''to be'' and ''God'', while the sentences encoded feature sections from the writings of ].<ref>See, for example, Richard Steinitz in Hill (1995), pp. 466–469</ref> | |||

| == |

==Writings== | ||

| {{div col|colwidth=40em}} | |||

| ===Compositions=== | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Messiaen |first=Olivier |year=1933 |title=Vingt leçons de solfège modernes |publisher=Editions H. Lemoine |location=Paris |oclc=1080796385|ref=none}} | |||

| ==== Published during his lifetime ==== | |||

| * {{cite magazine |last=Messiaen |first=Olivier |date=1936 |title=Ariane et Barbe-Bleue de Paul Dukas |magazine=] |issue=116 |pages=79–86 |author-mask=2|ref=none}} | |||

| * {{cite magazine |last=Messiaen |first=Olivier |date=31 March 1938 |title=Les sept chorals-poèmes pour les sept paroles du Christ en croix |magazine={{ill|Le monde musical|es||fr}} |issue=3 |page=34 |author-mask=2|ref=none}} | |||

| * {{cite magazine |last=Messiaen |first=Olivier |date=May 1938 |title=L'orgue mystique de Tournemire |magazine=Syrinx |issue= |pages=26–27 |author-mask=2|ref=none}} | |||

| * {{cite magazine |last=Messiaen |first=Olivier |date=1939 |title=Le rythme chez Igor Strawinsky |magazine=] |issue=191 |pages=91–92 |author-mask=2|ref=none}} | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Messiaen |first=Olivier |year=1939 |title=Vingt leçons d'harmonie |publisher=] |location=Paris |oclc=843636910 |author-mask=2|ref=none}} | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Messiaen |first=Olivier |year=1944 |title=Technique de mon langage musical |publisher=] |location=Paris |oclc=690654311 |author-mask=2|ref=none}}<ref>{{cite book|last=Broad|first=Stephen|chapter=Technique de mon langage musical|title=]|publisher=Taylor & Francis|year=2016|access-date=1 December 2021|chapter-url=https://www.rem.routledge.com/articles/technique-de-mon-langage-musical|doi=10.4324/9781135000356-REM601-1|isbn=978-1-135-00035-6 }}</ref> | |||

| * {{cite book |contributor-last=Messiaen |contributor-first=Olivier |contribution=Preface |contributor-mask=2 |last=Jolivet |first=André |author-link=André Jolivet |year=1946 |title=Mana: Six pièces pour piano |publisher=Costallat |location=Paris |oclc=884442941|ref=none}} | |||

| * {{cite magazine |last=Messiaen |first=Olivier |date=1947 |title=Maurice Emmanuel: ses "Trente chansons bourguignonnes" |magazine=] |issue=206 |pages=107–108 |author-mask=2|ref=none}} | |||

| * {{cite magazine |last=Messiaen |first=Olivier |date=1958 |title=Musikalisches Glaubens-bekenntnis|language=de|magazine={{ill|Melos (magzine)|de|Melos (Zeitschrift)|lt=Melos}}|issue=25/12 |pages=381–385 |author-mask=2}} | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Messiaen |first=Olivier |year=1960 |title=Conférence de Bruxelles |publisher=] |location=Paris |oclc=855187 |author-mask=2|ref=none}} Essentially a republishing of {{harvnb|Messiaen|1958}}. | |||

| * {{cite book |contributor-last=Messiaen |contributor-first=Olivier |contribution=Preface |contributor-mask=2 |last=Roustit |first=Albert |year=1970 |title=La prophétie musicale dans l'histoire de l'humanité précédée d'une étude sur les nombres et les planètes dans leur rapports avec la musique |publisher=Horvath |location=Roanne |url=https://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb353956051.public#:~:text=42%2DRoanne%20%3A-,Horvath,-%2C%201970|ref=none}} | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Messiaen |first=Olivier |year=1978 |title=Conférence de Notre Dame |publisher=] |location=Paris |oclc=4354577 |author-mask=2|ref=none}} | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Messiaen |first=Olivier |year=1986 |title=Messiaen on Messiaen: The Composer Writes about His Works |publisher=Frangipani Press |location=Bloomington |oclc=911921727 |author-mask=2|ref=none}} | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Messiaen |first=Olivier |year=1987 |title=Les 22 concertos pour piano de Mozart |publisher=Librairie Séguier |location=Paris |oclc=928373831 |author-mask=2|ref=none}} | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Messiaen |first=Olivier |year=1988 |title=Conférence de Kyoto |others=Introduction and Japanese translation by Naoko Tamamura |publisher=] |location=Paris |oclc=22921969 |author-mask=2|ref=none}} | |||

| * {{cite book |contributor-last=Messiaen |contributor-first=Olivier |contribution=Preface |contributor-mask=2 |last=Sauvage |first=Cécile |author-link=Cécile Sauvage |year=1991 |title=Tandis que la terre tourne |publisher=Librairie Séguier |location=Paris |oclc=463610307 |author-mask=2|ref=none}} | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Messiaen |first=Olivier |year=1994–2002 |title=Traité de rythme, de couleur, et d'ornithologie |publisher=] |location=Paris |oclc=931220676 |type=7 volumes |author-mask=2|ref=none}} | |||

| * {{cite book |last1=Messiaen |first1=Olivier |last2=Loriod |first2=Yvonne |author-link2=Yvonne Loriod |year= |title=Analyses des oeuvres pour piano de Maurice Ravel |publisher=] |location=Paris |oclc=995326437 |author-mask=2|ref=none}} | |||

| {{div col end}} | |||

| == See also == | |||

| *''Le banquet céleste'', organ (1928, a recomposition of a section from his unpublished orchestral piece ''Le banquet eucharistique''<ref>Hill & Simeone (2005), p. 25</ref>) | |||

| * ] | |||

| *''Préludes'', piano (1928-29) | |||

| *''Dyptique'', organ (1930) | |||

| *''La mort du nombre'' ("Number's death"), soprano, tenor, violin and piano (1930) | |||

| *''Les offrandes oubliées'' ("The forgotten offerings"), orchestra (1930) | |||

| *''Trois mélodies'', song cycle (1930) | |||

| *''Apparition de l'église éternelle'' ("Apparition of the eternal church"), organ (1932) | |||

| *''Fantaisie burlesque'', piano (1932) | |||

| *''Hymne au Saint Sacrament'' ("Hymn to the Holy Sacrament"), orchestra (1932, lost 1943, reconstructed from memory 1946<ref>Hill & Simeone (2005), p. 120</ref>) | |||

| *'']'', (Theme and Variations) violin and piano (1932) | |||

| *'']'' ("The Ascension"), orchestra (1932-33; organ version including replacement movement, 1933-34) | |||

| *''La Nativité du Seigneur'' ("The Lord's nativity"), organ (1935) | |||

| *''Pièce pour le tombeau de Paul Dukas'', piano, (1935) | |||

| *''Vocalise'', voice and piano (1935) | |||

| *''Poèmes pour Mi'', song cycle (1936, orchestral version 1937) | |||

| *''O sacrum convivium!'', choral motet (1937) | |||

| *''Chants de terre et de ciel'' ("Songs of earth and heaven"), song cycle (1938) | |||

| *''Les corps glorieux'' ("Glorious bodies"), organ (1939) | |||

| *'']'' ("Quartet for the end of time"), violin, cello, clarinet, piano (1940-41) | |||

| *Rondeau, piano (1943) | |||

| *''Visions de l'Amen'' ("Visions of the Amen"), two pianos (1943) | |||

| *''Trois Petites liturgies de la Présence Divine'' ("Three small liturgies of the Divine Presence"), women's voices, piano solo, ondes Martenot solo, orchestra (1943-44) | |||

| *'']'' ("Twenty gazes on the Christ-child"), piano (1944) | |||

| *''Harawi: Chants d'amour et de mort'', ("Harawi: Songs of love and death") song cycle (1944) | |||

| *'']'', ], ] solo, ] (1946-48) | |||

| *''Cinq réchants'', 12 singers (1948) | |||

| *'']'', piano (1949) | |||

| *''Messe de la Pentecôte'' ("] mass"), organ (1949-50) | |||

| *''Quatre études de rythme'' ("Four studies in rhythm"), piano (1949-50) | |||

| *# ''Île de feu 1'' | |||

| *# ''Mode de valeurs et d'intensités'' | |||

| *# ''Neumes rhythmique'' | |||

| *# ''Île de feu 2'' | |||

| *'' ] '' ("Blackbird"), flute and piano (1952<ref>Hill & Simeone (2005), pp. 199ff, outlines the chronology of Messiaen's compositions of 1951-52 ''Le merle noir'' and ''Livre d'orgue''</ref>) | |||

| *''Livre d'orgue'', organ (1951-2) | |||

| *''Réveil des oiseaux'' ("Dawn chorus"), solo piano and orchestra (1953) | |||

| *''Oiseaux exotiques'' ("Exotic birds"), solo piano and orchestra (1955-56) | |||

| *''Catalogue d'oiseaux'' ("Bird catalogue"), piano (1956-58) | |||

| **Book 1 | |||

| ***i ''Le chocard des alpes'' ("]") | |||

| ***ii ''Le loriot'' ("]") (''loriot'' and ''Loriod'' are ]) | |||

| ***iii ''Le merle bleu'' ("]") | |||

| **Book 2 | |||

| ***iv ''Le traquet stapazin'' ("]") | |||

| **Book 3 | |||

| ***v ''La chouette hulotte'' ("]") | |||

| ***vi ''L'alouette lulu'' ("]") | |||

| **Book 4 | |||

| ***vii ''La rousserolle effarvatte'' ("]") | |||

| **Book 5 | |||

| ***viii ''L'alouette calandrelle'' ("]") | |||

| ***ix ''La bouscarle'' ("]") | |||

| **Book 6 | |||

| ***x ''Le merle de roche'' ("]") <!-- documented as monticola saxatilis in the score --> | |||

| **Book 7 | |||

| ***xi ''La buse variable'' ("]") | |||

| ***xii ''Le traquet rieur'' ("]") | |||

| ***xiii ''Le courlis cendré'' ("]") | |||

| *''Chronochromie'' ("Time-colour"), orchestra (1959-60) | |||

| *''Verset pour la fête de la dédicace'', organ (1960) | |||

| *''Sept haïkaï'' ("Seven ]s"), solo piano and orchestra (1962) | |||

| *''Couleurs de la cité céleste'' ("Colours of the Celestial City"), solo piano and ensemble (1963) | |||

| *''Et expecto resurrectionem mortuorum'' ("And we await the resurrection of the dead"), wind, brass and percussion (1964) | |||

| *''La Transfiguration de Notre-Seigneur Jésus-Christ'' ("The Transfiguration of Our Lord Jesus Christ"), large 10-part chorus, piano solo, cello solo, flute solo, clarinet solo, xylorimba solo, vibraphone solo, large orchestra (1965-69) | |||

| *''Méditations sur le mystère de la Sainte Trinité'' ("Meditations on the mystery of the Holy Trinity"), organ (1969) | |||

| *''La fauvette des jardins'' ("]"), piano (1970) | |||

| *''Des Canyons aux étoiles…'' ("From the canyons to the stars…"), solo piano, solo horn, solo glockenspiel, solo xylorimba, small orchestra with 13 string players (1971-74) | |||

| *'']'' ("St. Francis of Assisi"), opera (1975-1983) | |||

| *''Livre du Saint Sacrament'' ("Book of the Holy Sacrament"), organ (1984) | |||

| *''Petites esquisses d'oiseaux'' ("Small sketches of birds"), piano (1985) | |||

| *''Un vitrail et des oiseaux'' ("Stained-glass window and birds"), piano solo, brass, wind and percussion (1986) | |||

| *''La ville d'En-haut'' ("The city on high"), piano solo, brass, wind and percussion (1987) | |||

| *''Un sourire'' ("A smile"), orchestra (1989) | |||

| *''Concert à quatre'' ("Quadruple concerto"), piano, flute, oboe, cello and orchestra (1990-91, completed Loriod and Benjamin) | |||

| *''Pièce pour piano et quatuor à cordes'' ("Piece for piano and string quartet") (1991) | |||

| *'']'' ("Flashes on the beyond..."), orchestra (1988-92) | |||

| ==Notes== | |||

| ==== Published posthumously ==== | |||

| {{Reflist|30em}} | |||

| A number of works exist which were not published in Messiaen's lifetime, including the following, some of which have been published posthumously, and some of which are lost. | |||

| *''La dame de Shallott'', for piano (1917) | |||

| *''La banquet eucharistique'', for orchestra (1928) | |||

| *''Variations écossaises'', for organ (1928) | |||

| *Mass, 8 sopranos and 4 violins (1933) | |||

| *''Fêtes des belles eaux'', for six ondes Martenots (1937) | |||

| *''Musique de scène pour un Œdipe'', electronic (1942) | |||

| *''Chant des déportés'', chorus and orchestra (1946) | |||