| Revision as of 23:22, 11 March 2007 editRickythesk8r (talk | contribs)79 editsm →Organ music and composers: delete superfluous comma; "known" for "know"← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 08:03, 16 December 2024 edit undoVycl1994 (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users126,160 editsNo edit summary | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Wind instrument controlled by keyboard}} | |||

| ] am Main, ]]] | |||

| {{About|organs that produce sound by driving wind through various pipes|an overview of related instruments|Organ (music)#Overview}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=October 2021}} | |||

| {{Infobox instrument | |||

| | name = Pipe organ | |||

| | names = Organ, Church organ (used only for organs in houses of worship) | |||

| | image = File:Neunkirchen am Brand Kirche Orgel-20210411-RM-155230.jpg | |||

| | image_size = 300px | |||

| | image_capt = Pipe organ in the collegiate church of St. Michael in ] | |||

| | background = keyboard | |||

| | classification = ] | |||

| | hornbostel_sachs = *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| | range = ] | |||

| | related = see ] | |||

| | builders = see ] and ] | |||

| | developed = ] | |||

| | inventors = ] | |||

| | sound sample = ].]] | |||

| }} | |||

| The '''pipe organ''' is a ] that produces sound by driving pressurised air (called ''wind'') through the ]s selected from a ]. Because each pipe produces a single pitch, the pipes are provided in sets called ''ranks'', each of which has a common ], volume, and construction throughout the keyboard ]. Most organs have many ranks of pipes of differing pitch, timbre, and volume that the player can employ singly or in combination through the use of controls called ]. | |||

| A pipe organ has one or more keyboards (called '']'') played by the hands, and a ] played by the feet; each keyboard controls its own division (group of stops). The keyboard(s), pedalboard, and stops are housed in the organ's ]. The organ's continuous supply of wind allows it to sustain notes for as long as the corresponding keys are pressed, unlike the piano and ] whose sound begins to dissipate immediately after a key is depressed. The smallest portable pipe organs may have only one or two dozen pipes and one manual; the largest organs may have over 33,000 pipes and as many as seven manuals.<ref>Willey, David (2001). "". Retrieved on 3 March 2008.</ref> A list of some of the most notable and largest pipe organs in the world can be viewed at ]. A ranking of the largest organs in the world—based on the criterion constructed by ], i.e. 'the number of ranks and additional equipment managed from a single console'—can be found in the quarterly magazine ''The Organ''<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Szostak|first=Michał|date=November 2017 – January 2018|title=The World's Largest Organs|url=http://www.theorganmag.com/issues/382.html|journal=The Organ|publisher=The Musical Opinion Ltd|volume=382|pages=12–28|issn=0030-4883|access-date=24 January 2019|archive-date=25 January 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190125080613/http://www.theorganmag.com/issues/382.html|url-status=live}}</ref> and in the online journal ''Vox Humana''.<ref>{{Cite journal|url=https://www.voxhumanajournal.com/szostak2018.html|title=The Largest Pipe Organs in the World|last=Szostak|first=Michał|date=30 September 2018|journal=Vox Humana|access-date=15 November 2019|archive-date=7 November 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201107161622/http://www.voxhumanajournal.com/szostak2018.html|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| {{tocleft}} | |||

| The origins of the pipe organ can be traced back to the ] in ], in the 3rd century BC,<ref name="origin">Randel "Organ", 583.</ref> in which the wind supply was created by the weight of displaced water in an airtight container. By the 6th or 7th century AD, ] were used to supply Byzantine organs with wind.<ref name="origin"/><ref name="Dalby, Andrew 2010">Dalby, Andrew ''Taste of Byzantium''. IB Tauris, 2010, {{ISBN|9781848851658}}, p. 118. "the narrative of the Syrian hostage Harun Ibn Yahya...'This is what happens at Christmas...they bring what is called an ''organon.'' It is a remarkable wooden object like an oil-press, and covered with solid leather. Sixty copper pipes are placed in it, so that they project above the leather, and where they are visible above the leather they are gilded. You can only see a small part of some of them, as they are of different lengths. On one side of this structure there is a hole in which they place a bellows like a blacksmith's. three crosses are placed at the two extremities and in the middle of the ''organon''. Two men come in to work the bellows, and the master stands and bidding to press on the pipes, and each pipe, according to its tuning and the master's playing, sounds the parsed of the Emperor. The guests are meanwhile seated at their tables, and twenty men enter with cymbals in their hands. The miscue continues while the guests continue their meal.' "</ref> A pipe organ with "great leaden pipes" was sent to the West by the ] emperor ] as a gift to ], King of the ], in 757.<ref>Willis, Henry. "The Organ, Its History and Development." Proceedings of the Royal Musical Association. Vol. 73. No. 1. Taylor & Francis Group, 1946. p. 60</ref> Pepin's son ] requested a similar organ for his chapel in ] in 812, beginning the pipe organ's establishment in Western European church music.<ref>Douglas Bush and Richard Kassel eds., Routledge. 2006. p. 327.</ref> In England, "The first organ of which any detailed record exists was built in Winchester Cathedral in the 10th century. It was a huge machine with 400 pipes, which needed two men to play it and 70 men to blow it, and its sound could be heard throughout the city."<ref>Winchester Cathedral http://www.winchester-cathedral.org.uk/worship-and-music/music-choir/the-cathedral-organ/ {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170929231648/http://www.winchester-cathedral.org.uk/worship-and-music/music-choir/the-cathedral-organ/ |date=29 September 2017 }}.</ref> Beginning in the 12th century, the organ began to evolve into a complex instrument capable of producing different ]s. By the 17th century, most of the sounds available on the modern classical organ had been developed.<ref>Randel "Organ", 584–585.</ref> At that time, the pipe organ was the most complex human-made device<ref>Michael Woods, ''Post-Gazette'', 26 April 2005. {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120222231705/https://lists.wu-wien.ac.at/pipermail/earlym-l/2006-March/003169.html |date=22 February 2012 }}</ref>—a distinction it retained until it was displaced by the ] in the late 19th century.<ref>N. Pippenger, "Complexity Theory", ''Scientific American'', 239:90–100 (1978).</ref> | |||

| The '''pipe organ''' is a ] ] that produces ] by admitting pressurized ] through a series of ]. Pipe organs range in size from portable instruments with only a few dozen pipes to very large organs with tens of thousands of pipes, causing ] to name it the "king of instruments."<ref>http://www.timesonline.co.uk/article/0,,2-2091757,00.html</ref> | |||

| Pipe organs are installed in churches, synagogues, concert halls, schools, mansions, other public buildings and in private properties. They are used in the performance of classical music, ], ], and ]. In the early 20th century, pipe organs were ] to accompany the screening of films during the ] era; in municipal auditoria, where orchestral ] were popular; and in the homes of the wealthy.<ref name=Rollin>{{cite book|last=Smith|first=Rollin|title=The Aeolian pipe organ and its music | |||

| The organ has been described as one of the oldest musical instruments, as its origins can be traced back to ancient Greece in the ] (] ὄργανον, ''órganon'').<ref>http://www.concertartist.info/organhistory/begin.htm</ref> The basic elements of a pipe organ are '''pipes''' (the sound-producing objects), placed on a chamber (called a '''windchest''') that stores air under mechanically-produced pressure (referred to as '''wind'''), where access of the air to the pipes is controlled by a ''']'''. Because of its constant wind supply, the organ is capable of sustaining sound for as long as the key is depressed, in contrast to other keyboard instruments, such as the ] and ], whose sound decays immediately after the key is depressed. The organ also boasts a substantial ], with music available spanning a period of over 400 years.<ref>http://www.lawrencephelps.com/Documents/Articles/Beginner/pipeorgans101.html</ref> | |||

| |publisher=The Organ Historical Society|location=Richmond VA USA|year=1998|isbn=0-913499-16-1}}</ref> The beginning of the 21st century has seen a resurgence in installations in concert halls. A substantial ] spans over 500 years.<ref>Thomas, Steve, 2003. {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20061026141858/http://www.lawrencephelps.com/Documents/Articles/Beginner/pipeorgans101.html |date=26 October 2006 }}. Retrieved on 6 May 2007.</ref> | |||

| ==History and development<span id="History"></span>== | |||

| Modern organs usually include more than one keyboard playable by the hands (called a ]) and a large keyboard playable by the feet called a ''']'''. The most commonly-seen configuration is two manuals with a pedalboard. Large organs can feature up to five manuals, although some of the largest have even more than this. | |||

| ===Antiquity=== | |||

| ], ], ], some of the pipes date from 1685.]]Pipe organs are commonly found in ] ]es, as well as in some ] and ] ]s, where they are used to accompany the musical portions of the service, such as choral ]s and congregational ]s as well as parts of the ]. Solo organ music is generally played before and after the service. These pieces are generally called '''voluntaries'''. Pipe organs are also found in town halls and in arts centres intended for the performance of ], especially for ] of orchestral music. In the era of ]s, large ]s were installed in many ]s. Large pipe organs with automatic mechanical player mechanisms were often found in the mansions of the very wealthy in the early ] in America. Today, small pipe organs are often found in the homes of organists and organ lovers. | |||

| ] from the 1st century BC, oldest organ found to date, ], Greece<ref name="Heritage">{{cite web|url=http://www.macedonian-heritage.gr/Museums/Archaeological_and_Byzantine/Arx_Diou.html|title=The Museums of Macedonia:Archaeological Museum of Dion|publisher=Macedonian Heritage|access-date=28 August 2009|archive-date=18 April 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180418170400/http://www.macedonian-heritage.gr/Museums/Archaeological_and_Byzantine/Arx_Diou.html|url-status=dead}}</ref>]] | |||

| ] villa in ], Syria.<ref name = Ring>{{citation | last = Ring | first = Trudy | title = International Dictionary of Historic Places: Middle East and Africa | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=R44VRnNCzAYC&q=mariamin+hama | year = 1994 | publisher = Taylor & Francis | volume = 4 | isbn = 1884964036 | access-date = 19 November 2020 | archive-date = 21 February 2023 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20230221143620/https://books.google.com/books?id=R44VRnNCzAYC&q=mariamin+hama | url-status = live }}</ref>]] | |||

| The organ is one of the oldest instruments still used in European classical music that has commonly been credited as having derived from Greece. Its earliest predecessors were built in ] in the 3rd century BC. The word ''organ'' is derived from the ] {{lang|grc|ὄργανον}} ({{transl|grc|órganon}}),<ref>Harper, Douglas (2001). {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081207201913/http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?search=organum&searchmode=none |date=7 December 2008 }}. '']''. Retrieved on 10 February 2008.</ref> a generic term for an instrument or a tool,<ref>Liddell, Henry George & Scott, Robert (1940). {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230221143621/http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.04.0057%3Aentry%3D%2374753&redirect=true |date=21 February 2023 }}. ''A Greek-English Lexicon''. Oxford: Clarendon Press. {{ISBN|0-19-864226-1}}. Perseus. Retrieved on 9 February 2008.</ref> via the ] {{lang|la|]}}, an instrument similar to a ] used in ancient Roman circus games. | |||

| ==History and development== | |||

| ]'s ''Madonna of Humility'', Siena 1433. The angel on the right plays a ] with a set of hand-pumped bellows.]] | |||

| The organ is one of the oldest instruments still used in ]. Its earliest predecessors date to the 3rd century BC. | |||

| The Greek engineer ] is credited with inventing the organ in the 3rd century BC. He devised an instrument called the ], which delivered a wind supply maintained through water pressure to a set of pipes.<ref name="hydraulis">Randel "Hydraulis", 385.</ref> The hydraulis was played in the arenas of the ]. The pumps and water regulators of the hydraulis were replaced by an inflated leather bag in the 2nd century AD,<ref name="hydraulis" /> and true ] began to appear in the Eastern Roman Empire in the 6th or 7th century AD.<ref name="origin" /> Some 400 pieces of a hydraulis from the year 228 AD were revealed during the 1931 archaeological excavations in | |||

| The word ''organ'' originates from the ] word "]", the instrument used in ancient Roman circus games and similar to a modern ]. | |||

| the former Roman town ], province of ] (present day ]), which was used as a music instrument by the Aquincum fire dormitory; a modern replica produces an enjoyable sound. | |||

| The 9th century ] geographer ] (d. 913), in his lexicographical discussion of instruments, cited the {{transl|fa|urghun}} (organ) as one of the typical instruments of the ].<ref name=Kartomi124>{{citation | |||

| The inventor most often credited is Greek engineer ], who created an instrument called the ], an ] (water-powered) instrument, in the ].<ref>http://www.concertartist.info/organhistory/begin.htm</ref> The hydraulis was common in the ], where its immensely loud tone was heard during games and circuses in amphitheatres, as well as in processions. Characteristics of this instrument have been inferred from mosaics, paintings, literary references and partial remains; a working, reconstructed instrument is owned by Aquincum Museum, ].<ref>http://www.aquincum.hu/orgona/orgonaangol.htm</ref> The exact mechanism of wind production is still debated, but the tone of the original pipes can be studied. Almost nothing is known of the actual music it played.<ref>http://www.cummingfirst.com/organ.html contains information on the ]</ref><ref>http://www.archaeologychannel.org/hydraulisint.html contains information on the ]</ref> The pumps and water regulators of the hydraulis were replaced by bellows in the 2nd Century AD.<ref>http://www.concertartist.info/organhistory/begin.htm</ref> | |||

| |last=Kartomi | |||

| |first=Margaret J. | |||

| |title=On Concepts and Classifications of Musical Instruments | |||

| |publisher=] | |||

| |year=1990 | |||

| |isbn=0-226-42548-7 | |||

| |page=124 | |||

| }}</ref> It was often used in the ] in the imperial capital of ]. A Syrian visitor describes a pipe organ powered by two servants pumping "bellows like a blacksmith's" played while guests ate at the emperor's Christmas dinner in Constantinople in 911.<ref name="Dalby, Andrew 2010"/> The first Western European pipe organ with "great leaden pipes" was sent from Constantinople to the West by the ] emperor ] as a gift to ] King of the ] in 757. Pepin's son ] requested a similar organ for his chapel in ] in 812, beginning its establishment in Western European church music.<ref>Douglas Bush and Richard Kassel eds., "The Organ, an Encyclopedia." Routledge. 2006. p. 327. </ref> | |||

| ===Medieval=== | |||

| ]'s painting of ] at a ] organ, 1671.]] | |||

| ].]] | |||

| Organs were also known to exist in the ] as well as in Islamic ]. In medieval times, the portable instruments (the ''']''' or ''']''' and the ''']''') were invented. Towards the middle of the 13th century, the portatives represented in the ] first show signs of a real keyboard with balanced keys, as in the 13th century Spanish manuscript known as the ].<ref>For a reproduction see J. F. Riaño, ''Studies of Early Spanish Music'', pp. 119-127 (London, 1887)</ref> Because of their portability, portatives were used for the accompaniment of both sacred and secular music in a variety of settings. | |||

| From 800 to the 1400s, the use and construction of organs developed in significant ways, from the invention of the portative and positive organs to the installation of larger organs in major churches such as the cathedrals of ]<ref name=":0">{{Cite book|last=Perrot|first=Jean|title=The Organ from its invention in the Hellenistic period to the end of the thirteenth century|publisher=University Press|year=1971}}</ref> and ] of Paris.<ref name=":2">{{Cite book|last=Wright|first=Craig|title=Music and Ceremony at Notre Dame of Paris|publisher=Cambridge University Press|year=1989|location=Cambridge}}</ref> In this period, organs began to be used in secular and religious settings. The introduction of organ into religious settings is ambiguous, most likely because the original position of the Church was that instrumental music was not to be allowed.<ref name=":0" /> By the 12th century there is evidence for permanently installed organs existing in religious settings such as the ] and other locations throughout Europe.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

| As the instruments became larger, they were installed permanently in a fashion similar to the church organs of today. At this time, organs did not have sophisticated ] controls: the organist would usually have the choice of playing on a single 8' Principal stop ''(see ])'' or what was called the Blockwerk. The '''Blockwerk''' consisted of the entire tonal resources of the organ, which in some cases meant a very large number of ranks ranging from 16' pitch all the way through 1' pitch and higher. | |||

| ]]] | |||

| Eventually, separate controls were built to allow the organist to control whether or not each rank in the Blockwerk would sound, effectively dividing the Blockwerk into separate stops. Some of the higher-pitched ranks were still grouped together under a single stop control; these stops were the forerunner of mixtures that would be found in later organs.<ref>http://www.lawrencephelps.com/Documents/Articles/Phelps/abrieflook.shtml</ref> | |||

| Several innovations occurred to organs in the Middle Ages, such as the creation of the ] and the ] organ. The portative organs were small and created for secular use and made of light weight delicate materials that would have been easy for one individual to transport and play on their own.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Bridges|first=Geoffrey|date=1992|title=Medieval Portatives|journal=The Galpin Society Journal|volume=45|pages=107–108|doi=10.2307/842265|jstor=842265}}</ref> The portative organ was a "flue-piped keyboard instrument, played with one hand while the other operated the bellows."<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Bridges|first=Geoffrey|date=1991|title=Medieval Portatives: Some Technical Comments|journal=The Galpin Society Journal|volume=44|pages=103–116|doi=10.2307/842212|jstor=842212}}</ref> Its portability made the portative useful for the accompaniment of both sacred and secular music in a variety of settings. The positive organ was larger than the portative organ but was still small enough to be portable and used in a variety of settings like the portative organ. Toward the middle of the 13th century, the portatives represented in the ] appear to have real keyboards with balanced keys, as in the ].<ref>Riaño, J. F. (1887). (PDF). London: Quaritch, 119–127. {{ISBN|0-306-70193-6}}.</ref> | |||

| It is difficult to directly determine when larger organs were first installed in Europe. An early detailed eyewitness account from ] gives an idea of what organs were like prior to the 13th century, after which more records of large church organs exist.<ref name=":1">{{Cite journal|last=Williams|first=Peter|date=1994|title=Difficulties in Understanding the Earliest Organs|journal=Festschrift Series|pages=167–195}}</ref> In his account, he describes the sound of the organ: "among them bells outstanding in tone and size, and an organ through bronze pipes prepared according to the musical proportions."<ref name=":1" /> This is one of the earliest accounts of organs in Europe and also indicates that the organ was large and more permanent than other evidence would suggest.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Caldwell|first=John|date=1966|title=The Organ in the Medieval Latin Liturgy, 800–1500|journal=Proceedings of the Musical Association|volume=93|pages=11–24|doi=10.1093/jrma/93.1.11}}</ref> | |||

| ===Renaissance and Baroque eras=== | |||

| ] in ], the ].]] | |||

| During the Renaissance and Baroque eras the organ became an instrument capable of creating numerous tonal colors, both unique and imitative. In northern Europe, the organ developed into a large instrument with several divisions, including an independent pedal. These divisions were readily discernible by the case design. This style was labeled the '''Werkprinzip''' by 20th-century organ scholars. In France, the ''French Classical Organ'' came into fashion, a style of building articulated most completely by ] in his magnum treatise, ''L'art de facteur d'orgues'' (''The Art of Organ Building'').<ref>www.synec-doc.be/musique/dbedos/dbedos.htm Extracts in French, translated into English as Ferguson, Charles (trans.), (1977) The Organ-Builder. Translation of Dom François Bedos de Celles ''l'Art du Facteur d'Orgue 1766-68''. Sunbury Press, Raleigh, NC</ref> | |||

| The first organ documented to have been permanently installed was one installed in 1361 in ], Germany.<ref name="oxforddict">Kennedy, Michael (Ed.) (2002). "Organ". In ''The Oxford Dictionary of Music'', p. 644. Oxford: Oxford University Press.</ref> The first documented permanent organ installation likely prompted ] to describe the organ as "the king of instruments", a characterization still frequently applied.<ref>Sumner "The Organ", 39.</ref> The Halberstadt organ was the first instrument to use a ] key layout across its three manuals and pedalboard, although the keys were wider than on modern instruments.<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080702232804/http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/315885/keyboard-instrument |date=2 July 2008 }} (2008). In ''Encyclopædia Britannica Online'' (subscription required, though relevant reference is viewable in concise article). Retrieved on 26 January 2008.</ref> The width of the keys was slightly over two and a half inches, wide enough to be struck down by the fist, as the early keys are reported to have invariably been manipulated.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Audsley |first=George Ashdown |title=The Art of Organ Building |publisher=Dover Publications |year=1965 |isbn=0-486-21315-3 |edition=2nd |pages=Volume II, page 61}}</ref> It had twenty bellows operated by ten men, and the wind pressure was so high that the player had to use the full strength of their arm to hold down a key.<ref name="oxforddict"/> | |||

| ===Romantic era=== | |||

| ] in ], ], U.K. This organ is a large instrument typical of its era with 39 independent stops over 3 manuals and pedals.]] | |||

| Records of other organs permanently installed and used in worship services in the late 13th and 14th centuries are found in large cathedrals such as ], the latter documenting organists hired to by the church and the installation of larger and permanent organs.<ref name=":2" /> The earliest is a payment in 1332 from the clergy of Notre Dame to an organist to perform on the feasts St. Louis and St. Michael.<ref name=":2" /> The Notre Dame School also shows how organs could have been used within the increased use of polyphony, which would have allowed for the use of more instrumental voices within the music.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Williams|first=Peter|date=1997|title=Further on The Organ in Western Culture 750–1250|journal=The Organ Yearbook |volume=27|pages=133–141}}</ref> According to documentation from the 9th century by Walafrid Strabo, the organ was also used for music during other parts of the church service—the prelude and postlude the main examples—and not just for the effect of polyphony with the choir. Other possible instances of this were short interludes played on the organ either in between parts of the church service or during choral songs, but they were not played at the same time as the choir was singing.<ref>Bowles, E. A. (1962). The Organ in the Medieval Liturgical Service. Revue Belge de Musicologie / Belgisch Tijdschrift Voor Muziekwetenschap, 16(1/4), 13–29. https://doi.org/10.2307/3686069</ref> This shows that by this point in time organs were fully used within church services and not just in secular settings. Organs from earlier in the medieval period are evidenced by surviving keyboards and casings, but no pipes.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Gwynn|first=Dominic|date=2015|title=The Mediaeval Tradition in English Organ Building|journal=Organists' Review|volume=101|pages=41–45}}</ref> Until the mid-15th century, organs had no stop controls. Each manual controlled ranks at many pitches, known as the "Blockwerk."<ref>Douglass, 10–12.</ref> Around 1450, controls were designed that allowed the ranks of the Blockwerk to be played individually. These devices were the forerunners of modern stop actions.<ref>Thistlethwaite, 5.</ref> The higher-pitched ranks of the Blockwerk remained grouped together under a single stop control; these stops developed into ].<ref>Phelps, Lawrence (1973). " {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060907041150/http://www.lawrencephelps.com/Documents/Articles/Phelps/abrieflook.shtml |date=7 September 2006 }}". Steve Thomas. Retrieved on 7 May 2007.</ref> | |||

| In the Romantic era the organ transitioned from a polyphonic to a symphonic instrument, capable of creating a massive layered crescendo from the softest stops alone to ''full organ'' (the state in which all the stops are engaged). Through the developments of the French organ builder ], the romantic organ inspired generations of composers, beginning with ] and continuing through the ]. In the Romantic era organs began to be built in concert halls, and the organ began to be called for in large symphonic works by such composers as ] and ]. | |||

| {{anchor|baroque organ}}<!--''Baroque organ'' and ''Baroque Organ'' redirect to the above anchor. If this section changes please update the redirects as necessary. TIA --> | |||

| ===Modern development=== | |||

| A major revolution in pipe organ design took place in the late-] when the development of pneumatic, electric and electro-pneumatic key actions made it technically feasible to locate the console independently of the pipes. There are however, advantages to more historical mechanical actions. Although they can be heavy to play, they allow a much more subtle, touch-sensitive feel to playing. Because the keys are physically attached to the valves that allow wind into the pipe, the organist has a sense of tactile feedback allowing greater rhythmic control. Also, the organist has control over the onset of the speech of the pipes. When organ builders began building historically-inspired instruments, they returned to mechanical key action to regain the subtle, nuanced control it gives the performer. Due to the benefits of modern technology, modern mechanical actions are often much lighter and require less effort to play than the original, substantially heavier mechanical actions.<ref>http://www.rosskingco.com/Pages/ref_mechanism.htm</ref> | |||

| During the 20th century, electrically-controlled stop actions allowed for the development of sophisticated ]s. | |||

| ===Renaissance and Baroque periods=== | |||

| Developments in the computer industry began to be incorporated into pipe organs using the techniques developed for ] (see below), incorporating them as "digital" components into real pipe organs. This had many advantages, such as actions that were much more simple in concept, as well as the allowance of better combination capture systems. Another development to the organ is the ] recording system, which can record and replay what an organist has played, and can even download files of these recordings onto a computer. | |||

| ] organ in ], Denmark<ref>Organ by Hermean Raphaelis, 1554. {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080105153651/http://www.copenhagenet.dk/CPH-Roskilde.htm |date=5 January 2008 }}. GBM MARKETING ApS. Retrieved on 13 May 2008.</ref>]] | |||

| During the ] and ] periods, the organ's tonal colors became more varied. Organ builders fashioned stops that imitated various instruments, such as the ] and the ]. Builders such as ], Jasper Johannsen, ] and ] constructed instruments that were in themselves artistic, displaying both exquisite craftsmanship and beautiful sound. These organs featured well-balanced mechanical key actions, giving the organist precise control over the pipe speech. Schnitger's organs featured particularly distinctive reed timbres and large Pedal and Rückpositiv divisions.<ref name="Webber 222">Webber, 222.</ref> | |||

| ====Pipeless organs (pseudo-Pipe organs)==== | |||

| In the mid-], churches and other institutions began increasingly substituting ]s without pipes (such as the ] organ, the ] organ, Viscount, and the ] organ) for pipe organs due to the cheaper initial cost and size. These instruments generally depend either on the Hammond electro/mechanical system (Hammond tonewheel generator), straight electronics (electronic oscillators and filters) or the more current recorded computer loop sounds to generate the tones. In the later 20th century, digital pipeless instruments were developed that emulate the sound of a pipe organ through ] techniques. Although the entire sound of a pipe organ cannot yet be completely recreated, they are still a viable option to many churches and other organizations, due to the lower costs involved, the lack of maintenance required, and the small amount of space necessary, as opposed to a substantial pipe organ. It is increasingly common for builders of new pipe organs to use digital stops for the very lowest pedal ranks owing to the economy of space and reduction of fabrication cost so enabled. Most organ builders and organists agree, however, that digital 32' ranks are less acceptable than digital pipes of higher pitches. Since the ] era and before, 32' ranks have been appreciated for their ability to augment harmonic richness in the rest of the organ while stirring the low frequencies in the air—two effects a speaker is unable to replicate. Organs such as that in Trinity Church in Copley Square, Boston, which have acoustical and digital 32' stops side-by-side, demonstrate the psychoacoustical inadequacies of the digital 32' stop.<ref>http://www.trinitychurchboston.org/music/organ-specs.pdf specification of Trinity Church, Boston organ</ref> Major builders of such instruments include the firms of ], ], ], and ]. | |||

| Different national styles of organ building began to develop, often due to changing political climates.<ref name="Randel 585">Randel "Organ", 585.</ref> In the Netherlands, the organ became a large instrument with several divisions, doubled ranks, and mounted cornets. The organs of northern Germany also had more divisions, and independent pedal divisions became increasingly common.<ref name="Randel 585" /> Organ makers began designing their cases in such a way that the divisions of the organ were visibly discernible. Twentieth-century musicologists have retroactively labelled this the ''Werkprinzip''.<ref>Bicknell "The organ case", 66–71.</ref> | |||

| ==Construction== | |||

| The primary elements of a pipe organ are: | |||

| *the '''console''', from which the organ is played | |||

| *the '''pipes''', which produce the sound | |||

| *the '''stop mechanism''', which allows the character of the sound to be changed | |||

| *the '''wind system''', which provides the air necessary for the pipes to sound | |||

| ], ], Portugal]] | |||

| ===Console=== | |||

| ] in the Macy's (formerly Lord and Taylor) department store in ], featuring six manuals and color-coded stop tabs.]] | |||

| In France, as in Italy, Spain and Portugal, organs were primarily designed to play ] verses rather than accompany ]. The ''French Classical Organ'' became remarkably consistent throughout France over the course of the Baroque era, more so than any other style of organ building in history, and standardized registrations developed.<ref name="Thistlethwaite, 12">Thistlethwaite, 12.</ref><ref>Douglass, 3.</ref> This type of instrument was elaborately described by ] in his treatise ''L'art du facteur d'orgues'' (''The Art of Organ Building'').<ref>{{in lang|fr}} Bédos de Celles, Dom François (1766). '' {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071011041127/http://synec-doc.be/musique/dbedos/dbedos.htm |date=11 October 2007 }}''. Ferguson (Tr.) (1977). Retrieved on 7 May 2007.</ref> The Italian Baroque organ was often a single-manual instrument, without pedals.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Williams |first1=Peter |title=A New History of the Organ |date=1980 |publisher=Faber and Faber |isbn=0-571-11459-8 |pages=126–130}}</ref> It was built on a full diapason chorus of octaves and fifths. The stop-names indicated the pitch relative to the fundamental ("Principale") and typically reached extremely short nominal pipe-lengths (for example, if the Principale were 8', the "Vigesimanona" was ½'). The highest ranks "broke back", their smallest pipes replaced by pipes pitched an octave lower to produce a kind of composite treble mixture. | |||

| The organ is played from an area called the '''console''' (if it is separate from the rest of the case) or '''keydesk''' (if it is integrated into the case), which holds the manuals, pedals, and stop controls. Some very large organs, such as the ] organ at the ] in ], have more than one console, enabling the organ to be played from several locations depending on the nature of the performance. | |||

| In England, many pipe organs were destroyed or removed from churches during the ] of the 16th century and the ] period. Some were relocated to private homes. At the ], organ builders such as ] and ] brought new organ-building ideas from continental Europe. English organs evolved from small one- or two-manual instruments into three or more divisions disposed in the French manner with grander reeds and mixtures, though still without pedal keyboards.<ref name="England">Randel "Organ", 586–587.</ref> The Echo division began to be enclosed in the early 18th century, and in 1712, Abraham Jordan claimed his "swelling organ" at ] to be a new invention.<ref name="Thistlethwaite, 12"/> The ] and the independent pedal division appeared in English organs beginning in the 18th century.<ref name="England" /><ref>McCrea, 279–280.</ref> | |||

| In organs that use electronic action, the console is often movable. This allows for greater flexibility in placement of the console for various activities. Some organ builders even use ]s to connect the console to the main interface board. Some large organs may also have two consoles: one built into the organ case itself, the other a movable console used for recitals or for church services, to allow the organist to be closer to either choir or congregation. | |||

| ===Romantic period=== | |||

| Controls at the console called ''']''' select which ranks and pipes are used. These controls are generally either '''draw stops''', which engage the stops when pulled out from the console, or '''stop tabs''' that rock up and down. Other stop controls include sliding rods and light-up digital buttons. | |||

| During the Romantic period, the organ became more symphonic, capable of creating a gradual crescendo. This was made possible by voicing stops in such a way that families of tone that historically had only been used separately could now be used together, creating an entirely new way of approaching organ registration. New technologies and the work of organ builders such as ], ], and ] made it possible to build larger organs with more stops, more variation in sound and timbre, and more divisions.<ref name="England" /> For instance, as early as in 1808, the first 32' contre-bombarde was installed in the great organ of Nancy Cathedral, France. Enclosed divisions became common, and registration aids were developed to make it easier for the organist to manage the great number of stops. The desire for louder, grander organs required that the stops be voiced on a higher wind pressure than before. As a result, a greater force was required to overcome the wind pressure and depress the keys. To solve this problem, Cavaillé-Coll configured the English "]" to assist in operating the key action. This is, essentially, a servomechanism that uses wind pressure from the air plenum, to augment the force that is exerted by the player's fingers.<ref>Randel "Organ", 586.</ref><!--Combination actions were developed to aid the organist in carrying out the multitude of registration changes required to play Romantic music.{{Citation needed|date=May 2008}}--> | |||

| Organ builders began to prefer specifications with fewer mixtures and high-pitched stops, more 8′ and 16′ stops and wider pipe scales.<ref>"The decline of mixtures," in George Laing Miller (1913), '' {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110917040223/http://www.gutenberg.org/files/21204/21204-h/21204-h |date=17 September 2011 }}''. Retrieved on 7 July 2009.</ref> These practices created a warmer, richer sound than was common in the 18th century. Organs began to be built in concert halls (such as the organ at the ] in Paris), and composers such as ] and ] used the organ in their orchestral works. | |||

| Different combinations of stops change the timbre of the instrument considerably. The selection of stops is called the '''registration'''. On modern organs, the registration can be changed instantaneously with the aid of a ], usually featuring pistons. '''Pistons''' are buttons that can be pressed by the organist to change registrations; they are generally found between the manuals or above the pedalboard. In the latter case they are called '''toe studs''' or '''toe pistons''' (as opposed to '''thumb pistons'''). Most large organs have both preset and programmable pistons, with some of the couplers repeated for convenience as pistons and toe studs. Programmable pistons allow comprehensive control over changes in registration. These are commonly grouped under the title '''registration aids'''. Newer solid state organs have multiple levels of memory, allowing each piston to be programmed more than once. This allows more than one organist to register the stops they want. Many newer consoles also feature ], which allows the organist to record performances. It also allows an external keyboard to be plugged in, which assists in tuning, and troubleshooting. | |||

| <gallery widths="200px" heights="200px"> | |||

| ====Organization of console controls==== | |||

| File:Yoke.JPG|A typical modern 20th-century console, located in ] | |||

| ] chapel's new five-manual console, crafted by of Johnson City, TN. It boasts 522 draw knobs, and, in addition to the other controls available to the organist, yields 796 total controls.]] | |||

| File:Basilica_of_Saint_Denis_Organ,_Paris,_France_-_Diliff.jpg|The organ of the Cathedral-] (France), first organ of ] containing numerous innovations, and especially the first ]. | |||

| In modern organ building, an accepted standardized scheme is used for the layout of the stops and pistons on the console. The stops controlling each '''division''' (see ]) are grouped together. Within these, the standard arrangement is for the lowest sounding stops (32' or 16') to be placed at the bottom of the columns, with the higher pitched stops are placed above this, (8', 4', 2 2/3', 2' etc.); the 'mixtures' are placed above this (II, III, V etc). The stops controlling the reed ranks are placed collectively above these in the same order as above, often with the stop engraving in <font color=red>red</font>. | |||

| File:Buffet grand-orgue.jpg|] (France) | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| ===Modern development=== | |||

| Thus, an example stop configuration for a Great division may look like this: | |||

| ] | |||

| The development of pneumatic and electro-pneumatic key actions in the late 19th century made it possible to locate the console independently of the pipes, greatly expanding the possibilities in organ design. Electric stop actions were also developed, which allowed sophisticated combination actions to be created.<ref>Thistlethwaite, 14–15.</ref> | |||

| {| class="wikitable" | |||

| |- | |||

| |<font color=red>4' Clarion</font>|| | |||

| |- | |||

| |<font color=red>16' Trombone</font> || <font color=red>8' Trumpet</font> | |||

| |- | |||

| |2' Fifteenth || V Mixture | |||

| |- | |||

| |4' Principal || 2 2/3' Twelfth | |||

| |- | |||

| |8' Dulciana || 4' Harmonic Flute | |||

| |- | |||

| |8' Open Diapason || 8' Stopped Diapason | |||

| |- | |||

| |16' Double Diapason || | |||

| |- | |||

| |Gt Super Octave || Gt Sub Octave | |||

| |- | |||

| |Swell to Great || Choir to Great | |||

| |} | |||

| The standard position for these columns of stops (assuming drawknobs are used) is for the Choir or Positiv division to be on the outside of the players' right, with the Great nearer the center of the console and the music rest. On the left hand side, the Pedal division is on the outside, with the Swell to the inside. Other divisions can be placed on either side, depending on the amount of space available. Manual couplers and octave extensions are placed either within the stop knobs of the divisions that they control, or grouped together above the uppermost manual. The pistons, if present, are placed directly under the manual they control. | |||

| Beginning in the early 20th century in Germany and in the mid-20th century in the United States, organ builders began to build ] instruments modeled on Baroque organs. They returned to building mechanical key actions, voicing with lower wind pressures and thinner pipe scales, and designing specifications with more mixture stops.<ref>Bicknell "Organ building today", 82ff.</ref> This became known as the ]. | |||

| In order to be more historically accurate, organs built along historical models will often use older schemes for organizing the keydesk controls. | |||

| In the late 20th century, organ builders began to incorporate digital components into their key, stop, and combination actions. Besides making these mechanisms simpler and more reliable, this also makes it possible to record and play back an organist's performance using the ] protocol.<ref>Retrieved on 7 July 2009.</ref> In addition, some organ builders have incorporated digital (electronic) stops into their pipe organs. | |||

| ====Keyboards==== | |||

| ], ], ]. The organ was built by Harrison and Harrison in 1912 and restored in 1990.]] | |||

| The organ is played with at least one ], with configurations featuring from two to five keyboards being the most common. A keyboard to be played by the hands is called a ''']''' (from the ] ''manus'', "hand"); an organ with four keyboards is said to have four manuals. Most organs also have a ''']''', a large keyboard to be played by the feet. | |||

| The ] developed throughout the 20th century. Some pipe organs were replaced by digital organs because of their lower purchase price, smaller physical size, and minimal maintenance requirements. In the early 1970s, ] pioneered the ''hybrid'' organ, an electronic instrument that incorporates real pipes; other builders such as ] and ] have since built hybrid organs. Allen Organs first introduced the electronic organ in 1937 and in 1971 created the first digital organ using CMOS technology borrowed from NASA which created the digital pipe organ using sound recorded from actual speaking pipes and incorporating the sounds electronically within the memory of the digital organ thus having real pipe organ sound without the actual organ pipes. | |||

| The collection of ranks controlled by a particular manual is called a '''division'''. The names of the divisions of the organ vary geographically and stylistically. Common names for divisions are: | |||

| ==Construction== | |||

| *Great, Swell, Choir, Solo, Orchestral, Echo, Antiphonal (America) | |||

| A pipe organ contains one or more sets of pipes, a wind system, and one or more keyboards. The pipes produce sound when pressurized air produced by the wind system passes through them. An action connects the keyboards to the pipes. ] allow the organist to control which ranks of pipes sound at a given time. The organist operates the stops and the keyboards from the ]. | |||

| *Hauptwerk, Rückpositiv, Oberwerk, Brustwerk, Schwellwerk (Germany) | |||

| *Grand Choeur, Grand Orgue, Récit, Positif, Bombarde (France) | |||

| *Hoofdwerk, Rugwerk, Bovenwerk, Borstwerk, Zwelwerk (Holland) | |||

| ===Pipes=== | |||

| Like the arrangement of stops, the keyboard divisions are also arranged in a common order. Taking the English names as an example, the main manual (the bottom manual on two-manual instruments or the middle manual on three-manual instruments) is traditionally called the Great, and the upper manual is called the Swell. If there is a third manual, it is usually the Choir and is placed below the Great. If it is included, the Solo manual is usually placed above the Swell. Some larger organs contain an Echo or Antiphonal division, usually controlled by a manual placed above the Solo. German and English organs generally use the same configuration of manuals as American organs. On French instruments, the main manual (the Grand Orgue) is at the bottom, with the Positif and the Récit above it. If there are more manuals, the Bombarde is usually above the Récit and the Grand Choeur is below the Grand Orgue. | |||

| {{Main|Organ pipe}} | |||

| ] found at the ] in ], Utah, has 11,623 pipes and accompanies ] and ].]] | |||

| Organ pipes are made from either wood or metal and produce sound ("speak") when air under pressure ("wind") is directed through them.<ref>Randel "Organ", 578.</ref> As one pipe produces a single ], multiple pipes are necessary to accommodate the ]. The greater the length of the pipe, the lower its resulting pitch will be.<ref name="randel579">Randel "Organ", 579.</ref> The ] and volume of the sound produced by a pipe depends on the volume of air delivered to the pipe and the manner in which it is constructed and voiced, the latter adjusted by the ] to produce the desired tone and volume. Hence a pipe's volume cannot be readily changed while playing.<ref name="randel579" /> | |||

| ], showing the pipes of the organ.]] | |||

| In addition to names, the manuals may be numbered with Roman numerals, starting from the bottom. Organists will frequently mark a part in their music with the number of the manual they intend to play it on, and this is sometimes seen in the original composition, typically in pieces written when organs were smaller and only had two or three manuals. It is also common to see super- and sub-couplers labeled as "II to I" (see ] below) | |||

| Organ pipes are divided into ]s and ]s according to their design and timbre. Flue pipes produce sound by forcing air through a ], like that of a ], whereas reed pipes produce sound via a beating ], like that of a clarinet or saxophone.<ref>Bicknell "Organ construction", 27.</ref> | |||

| Pipes are arranged by timbre and pitch into ranks. A rank is a set of pipes of the same timbre but multiple pitches (one for each note on the keyboard), which is mounted (usually vertically) onto a ].<ref name="Bicknell 20">Bicknell "Organ construction", 20.</ref> The ] admits air to each rank. For a given pipe to sound, the stop governing the pipe's rank must be engaged, and the key corresponding to its pitch must be depressed. Ranks of pipes are organized into groups called divisions. Each division generally is played from its own keyboard and conceptually comprises an individual instrument within the organ.<ref>Gleason, 3–4.</ref> | |||

| In some cases, an organ contains more divisions than it does manuals. In these cases, the extra divisions are called '''floating''' divisions and are played by coupling them to another manual. Usually this is the case with Echo/Antiphonal and Orchestral divisions, and sometimes it is seen with Solo and Bombarde divisions. | |||

| === Action === | |||

| Although manuals are almost always horizontal, organs with five or more manuals may incline the uppermost manuals towards the organist to make them easier to reach. | |||

| An organ contains two actions, or systems of moving parts: the keys, and the stops. The key action causes wind to be admitted into an organ pipe while a key is depressed. The stop action causes a rank of pipes to be engaged (i.e. playable by the keys) while a stop is in its "on" position. An action may be mechanical, pneumatic, or electrical (or some combination of these, such as electro-pneumatic).<ref>William H. Barnes "The Contemporary American Organ"</ref> The key action is independent of the stop action, allowing an organ to combine a mechanical key action with an electric stop action. | |||

| A key action in which the keys are connected to the windchests by only rods and levers is a mechanical or ]. When the organist depresses a key, the corresponding rod (called a tracker) pulls open its pallet, allowing wind to enter the pipe.<ref>Bicknell "Organ construction", 22–23.</ref> | |||

| ====Enclosure and expression pedals==== | |||

| ] in Honduras.]] | |||

| On most organs, at least one division will be '''enclosed'''. On a two-manual (Great and Swell) organ, this will be the Swell division (from whence the name comes); on larger organs often part, or all of, the choir and solo divisions will be enclosed as well. | |||

| In a mechanical stop action, each stop control operates a valve for a whole rank of pipes. When the organist selects a stop, the valve allows wind to reach the selected rank.<ref name="Bicknell 20"/> The first kind of control used for this purpose was a draw ], which the organist selects by pulling (or drawing) toward himself/herself. Pulling all of the knobs thus activates all available pipes, and is the origin of the idiom "]".<ref>{{Cite web |date=December 7, 2018 |title=What Does It Mean to 'Pull Out All the Stops'? |url=https://www.merriam-webster.com/wordplay/pull-out-all-the-stops-phrase-history-pipe-organ |website=Merriam-Webster |quote=To pull out all the stops literally, then, is to pull out every knob so that air is allowed to blast through every rank as the organist plays, which creates a powerful blast of unfiltered sound.}}</ref> More modern stop selectors, utilized in electric actions, are ordinary electrical switches and/or magnetic valves operated by a rocker tab.<ref>{{Cite web |date=2024 |title=Organ Types and Components |url=https://organ.byu.edu/organ-types-and-components/ |access-date=June 26, 2024 |website=] Organ}}</ref> | |||

| Tracker action has been used from antiquity to modern times. Before the pallet opens, wind pressure augments tension of the pallet spring, but once the pallet opens, only the spring tension is felt at the key. This sudden decrease of key pressure against the finger provides a "breakaway" feel.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.pykett.org.uk/the_physics_of_organ_actions.htm#Fore-touch%20Weight |title=The Physics of Organ Actions, Part 1: Mechanical Actions, "Fore-touch weight" |access-date=4 May 2019 |archive-date=16 December 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191216191326/http://www.pykett.org.uk/the_physics_of_organ_actions.htm#Fore-touch%20Weight |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| Enclosure is the term for the device that allows volume control (] and ]) for a manual without the addition or subtraction of stops. All the pipes for the division are surrounded by a box-like structure (often simply called the ''']'''). One side of the box, usually that facing the console or the listener, will be constructed from horizontal palettes (wooden flaps) which can be opened or closed from the console. This works in a similar fashion to a ]. When the box is 'open' it allows more sound to be heard than if it were 'closed'. | |||

| A later development was the ], which uses changes of pressure within lead tubing to operate pneumatic valves throughout the instrument. This allowed a lighter touch, and more flexibility in the location of the console, within a roughly 50-foot (15-m) limit. This type of construction was used in the late 19th century and early 20th century, and has had only rare application since the 1920s.<ref name="ReferenceA">William H. Barnes, "The Contemporary American Organ"</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| A more recent development is the electric action, which uses low voltage DC to control the key and/or stop mechanisms. Electricity may control the action indirectly by activating air pressure valves (pneumatics), in which case the action is ]. In such actions, an electromagnet attracts a small pilot valve which lets wind go to a bellows (the "pneumatic" component) which opens the pallet. When electricity operates the action directly without the assistance of pneumatics, it is commonly referred to as ].<ref name="ReferenceA"/> In this type, the electromagnet's armature carries a disc pallet. | |||

| The most common form of controlling the level of sound released from the enclosed box is by the use of a ''']'''. This is usually placed above the centre of the ], rotating away from the organist from a near horizontal ("open") to a near vertical position ("shut"). | |||

| When electrical wiring alone is used to connect the console to the windchest, electric actions allow the console to be separated at any practical distance from the rest of the organ, and to be movable.<ref>Bicknell "Organ construction", 23–24.</ref> Electric stop actions can be controlled at the console by stop knobs, by pivoted tilting tablets, or rocker tabs. These are simple switches, like wall switches for room lights. Some may include electromagnets for automatic setting or resetting when combinations are selected. | |||

| In addition, an organ may have a similar-looking ''']''', which would be found to the right of any expression pedals. Applying the crescendo pedal will incrementally activate all the stops in the organ, starting with the softest stops and ending with the loudest. As the order the stops are activated is usually set by the organ builder, this is a quick way for the organist to get to a registration that will sound attractive at a given volume without choosing a particular registration, or to simply get to full organ. (Some organs also have a piston that activates full organ.) | |||

| Computers have made it possible to connect the console and windchests using narrow data cables instead of the much larger bundles of simple electric cables. Embedded computers in the console and near the windchests communicate with each other via various complex multiplexing syntaxes, comparable to MIDI. | |||

| Historically, the enclosure was operated by the use of the ''']''', a lever that locks into two or three positions controlling the opening of the shutters. Many Ratchet Swell devices were replaced by the more advanced Balanced pedal because it allows the enclosure to be set at any point. | |||

| <gallery widths="200px" heights="170px"> | |||

| ====Couplers==== | |||

| File:SommierOrgue.jpg|Cross-section of one note of a mechanical-action windchest. Trackers attach to the wires hanging through the bottom board at the left. A wire pulls down on the pallet (valve) against the tension of the V-shaped spring. Wind under pressure surrounds the pallet, and when it is pulled down, the wide rectangular chamber above the pallet feeds wind to all pipes of this note and stop; note the cutaway passages at the top. | |||

| A device called a '''coupler''' allows the pipes of one division to be played by a manual. For example, a coupler labelled "Swell to Great" allows the stops of the Swell division to be played by the Great manual. It is unnecessary to couple the pipes of a division to the manual of the same name (for example, coupling the Great division to the Great manual), because those stops play by default on that manual (though this is done with super- and sub-couplers, see below). By using the couplers, the entire resources of an organ can be played simultaneously from one manual. On a mechanical-action organ, a coupler may connect one division's manual directly to the other, actually moving the keys of the first manual when the second is played. | |||

| File:Cradley Heath Baptist Church Organ A01.JPG|Interior of the organ at ] showing the tracker action. The black rods, called rollers, rotate to transmit movement sideways to line up with the pipes. | |||

| File:Schleiflade Tontraktur Animation.gif|Schematic animation of a mechanical-action windchest with three ranks of pipes | |||

| File:Guercino - St. Cecilia - Google Art Project.jpg|], patron saint of music, depicted playing the pipe organ | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| ===Wind system=== | |||

| Some organs feature a device to add the octave above or below what is being played by the fingers. The '''"super-octave"''' adds the octave above, the '''"sub-octave"''' the octave below. These may be attached to one division only, for example "Swell octave" (the ''super'' is often assumed), or they may act as a coupler, for example "Swell octave to Great" which gives the effect whilst playing on the Great division of adding the Swell division an octave above what is being played. These can be used in conjunction with the standard ] coupler. The super-octave may be labelled, for example, Swell to Great 4'; in the same manner, the sub-octave may be labelled Choir to Great 16'. | |||

| ]]] | |||

| <!--Remove image for now, at a smaller size, it does not really show the wind system, only a wind pipe, so actually not very useful.], showing part of the wind system]]--> | |||

| The wind system consists of the parts that produce, store, and deliver wind to the pipes. Pipe organ wind pressures are on the order of {{convert|0.10|psi|kPa|abbr=on}}. Organ builders traditionally measure organ wind using a water U-tube ], which gives the pressure as the difference in water levels in the two legs of the manometer. The difference in water level is proportional to the difference in pressure between the wind and the atmosphere.<ref>{{cite book|title=Process Instruments and Controls Handbook|editor=Douglas M. Considine|publisher=McGraw-Hill|year=1974|edition=Second|pages=3–4|isbn=0-07-012428-0}}</ref> The 0.10 psi above would register as 2.75 ] (70 ]). An Italian organ from the ] may be on only {{convert|2.2|in|mm}},<ref>Dalton, 168.</ref> while (in the extreme) solo stops in some large 20th-century organs may require up to {{convert|50|in|mm}}. In isolated, extreme cases, some stops have been voiced on {{convert|100|in|mm}}.{{efn|The ] in ] has four stops on 100 inches and ten stops on 50. . Oddmusic.com. Retrieved on 4 July 2007.}} | |||

| The inclusion of these couplers allows for greater registrational flexibility and color. Some literature (particularly romantic literature from France) calls explicitly for ''octaves aigues'' (super-couplers) to add brightness, or ''octaves graves'' (sub-couplers) to add gravity. Some organs feature extended ranks to accommodate the top and bottom octaves when the super- and sub-couplers are engaged (see the discussion under "Unification and extension"). | |||

| With the exception of ], playing the organ before the invention of ] required at least one person to operate the ]. When signaled by the organist, a ''calcant'' would operate a set of bellows, supplying the organ with wind.<ref>Bicknell "Organ construction", 18.</ref> Rather than hire a calcant, an organist might practise on some other instrument such as a ] or ].<ref>Koopman, Ton (1991). " {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190203143624/https://www.jstor.org/stable/965836 |date=3 February 2019 }}". ''The Musical Times'' '''123''' (1777) (subscription required, though relevant reference is viewable in preview). Retrieved on 22 May 2007.</ref> By the mid-19th-century bellows were also operated by ]s,<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.douglas-self.com/MUSEUM/POWER/waterengine/waterengine6.htm |title=Water Engines: Page 6 |publisher=Douglas-self.com |date=10 June 2011 |access-date=22 October 2011 |archive-date=20 January 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120120155848/http://www.douglas-self.com/MUSEUM/POWER/waterengine/waterengine6.htm |url-status=live }}</ref> steam engines or gasoline engines.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.bowralanglican.org.au/history_pipe_organ.html |archive-url=https://archive.today/20091013162343/http://www.bowralanglican.org.au/history_pipe_organ.html |url-status=dead |archive-date=13 October 2009 |title=St Jude's: History Pipe Organ |publisher=Bowralanglican.org.au |access-date=22 October 2011 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.akc-orgel.be/akcv2/main.php?lang=en&tekstid=16 |title=Antwerpse Kathedraalconcerten vzw |publisher=Akc-orgel.be |access-date=22 October 2011 |archive-date=30 September 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110930074615/http://www.akc-orgel.be/akcv2/main.php?lang=en&tekstid=16 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.nzorgan.com/vandr/blowers3.htm |title=organ blowers 3 |publisher=Nzorgan.com |date=26 July 1997 |access-date=22 October 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110927165438/http://www.nzorgan.com/vandr/blowers3.htm |archive-date=27 September 2011 }}</ref> Starting in the 1860s bellows were gradually replaced by rotating turbines which were later directly connected to electrical motors.<ref>Sefl, 70–71</ref> This made it possible for organists to practice regularly on the organ. Most organs, both new and historic, have electric ], although some can still be operated manually.<ref> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081205183718/http://www.cbfisk.com/do/DisplayInstrumentAbout/instId/72 |date=5 December 2008 }}. ] Retrieved on 13 May 2008.</ref> The wind supplied is stored in one or more regulators to maintain a constant pressure in the ''windchests'' until the action allows it to flow into the pipes.<ref>Bicknell "Organ construction", 18–20.</ref> | |||

| In a similar vein are '''unison off''' couplers, which act to "turn off" the stops of a division on its own keyboard. For example, a coupler labelled "Great unison off" would keep the stops of the Great division from sounding, even if they were pulled. Unison off couplers can be used in combination with super- and sub-couplers to create complex registrations that would otherwise not be possible. In addition, the unison off couplers can be used with the standard couplers to change the order of the manuals at the console: engaging the Great to Choir and Choir to Great couplers along with the Great unison off and Choir unison off couplers would have the effect of moving the Great to the bottom manual and the Choir to the middle manual. | |||

| === |

===Stops=== | ||

| {{Main|Organ stop}} | |||

| Another form of coupler found on some large organs is the '''divided pedal'''. This is a device that allows the sounds played on the pedals to be split, so the lower half (principally that of the left foot) plays stops from the pedal division simultaneously with the right foot, which plays stops from one of the manual divisions. The choice of manual is at the discretion of the performer, as is the ''split point'' of the system. | |||

| Each stop usually controls one rank of pipes, although ] and undulating stops (such as the ]) control multiple ranks.<ref name="Bicknell 26-27">Bicknell "Organ construction", 26–27.</ref> The name of the stop reflects not only the stop's timbre and construction, but also the style of the organ in which it resides. For example, the names on an organ built in the north German Baroque style generally will be derived from the German language, while the names of similar stops on an organ in the French Romantic style will usually be French. Most countries tend to use only their own languages for stop nomenclature. English-speaking nations as well as Japan are more receptive to foreign nomenclature.{{Citation needed|date=February 2019}} Stop names are not standardized: two otherwise identical stops from different organs may have different names.<ref>Bicknell "Organ construction", 27–28.</ref> | |||

| The system can be found on the organs of ] and ], having been added by ], as well as on the new nave console of ]. The system as found in ] operates like this: | |||

| To facilitate a large range of timbres, organ stops exist at different pitch levels. A stop that sounds at ] when a key is depressed is called an 8′ (pronounced "eight-foot") pitch. This refers to the speaking length of the lowest-sounding pipe in that rank, which is approximately {{convert|8|ft|spell=in}}. For the same reason, a stop that sounds an octave higher is at 4′ pitch, and one that sounds two octaves higher is at 2′ pitch. Likewise, a stop that sounds an octave lower than unison pitch is at 16′ pitch, and one that sounds two octaves lower is at 32′ pitch.<ref name="Bicknell 26-27"/> Stops of different pitch levels are designed to be played simultaneously. | |||

| *'''Divided Pedal''' (adjustable dividing point): A# B c c# d d# | |||

| :under the 'divide': Pedal stops and couplers | |||

| :above the 'divide': four illuminated controls: Choir/Swell/Great/Solo to Pedal<ref>http://npor.emma.cam.ac.uk/cgi-bin/Rsearch.cgi?Fn=Rsearch&rec_index=N11147</ref> | |||

| The label on a stop knob or rocker tab indicates the stop's name and its pitch in feet. Stops that control multiple ranks display a Roman numeral indicating the number of ranks present, instead of pitch.<ref>Johnson, David N. (1973). . Revised edition. Augsburg Fortress. p. 9. {{ISBN|978-0-8066-0423-7}}. Google Book search. Retrieved on 15 August 2008.</ref> Thus, a stop labelled "Open Diapason 8′ " is a single-rank ] stop sounding at 8′ pitch. A stop labelled "Mixture V" is a five-rank mixture. | |||

| This allows four different sounds to be played at once, for example: | |||

| :Right hand: Great principals 8' and 4' | |||

| :Left hand: Swell strings | |||

| :Left foot: Pedal 16' and 8' flutes and Swell to Pedal coupler | |||

| :Right foot: Solo Clarinet via divided pedal coupler | |||

| Sometimes, a single rank of pipes may be able to be controlled by several stops, allowing the rank to be played at multiple pitches or on multiple manuals. Such a rank is said to be ''unified'' or ''borrowed''. For example, an 8′ Diapason rank may also be made available as a 4′ Octave. When both of these stops are selected and a key (for example, c′){{efn|name=Helmholtz|This article uses the ] to indicate specific pitches.}} is pressed, two pipes of the same rank will sound: the pipe normally corresponding to the key played (c′), and the pipe one octave above that (c′′). Because the 8′ rank does not have enough pipes to sound the top octave of the keyboard at 4′ pitch, it is common for an extra octave of pipes used only for the borrowed 4′ stop to be added. In this case, the full rank of pipes (now an ''extended rank'') is one octave longer than the keyboard.{{efn|The purpose of extended ranks and of their being borrowed is to save on the number of pipes. For example, without unification, three stops may use 183 pipes. With unification three stops may borrow one extended rank of 85 pipes. That's 98 fewer pipes used for those three stops.}} | |||

| ===Pipes, Ranks and Stops=== | |||

| ''See ] for more information on this topic. | |||

| ] in ]. This organ features an open case design where the pipes are left exposed. The swell shutters can be seen open in the rear.]] | |||

| Special unpitched stops also appear in some organs. Among these are the ] (a wheel of rotating bells), the nightingale (a pipe submerged in a small pool of water, creating the sound of a bird warbling when wind is admitted),<ref>Randel "Rossignol", 718.</ref> and the ''effet d'orage'' ("thunder effect", a device that sounds the lowest bass pipes simultaneously). Standard orchestral percussion instruments such as the drum, ], ], and ] have also been imitated in organ building.<ref>Ahrens, 339; Kassel, 526–527</ref> | |||

| ]s are arranged in '''ranks'''. A rank is a complete set of pipes of similar timbre tuned to a ]. The great majority of ranks are mounted vertically, but some ranks may be mounted horizontally, as is the case with ''trompettes ]''. At the base of the pipes is a '''windchest''' which supplies air (known in the organ world as "wind") to the pipes. The manner in which the wind is admitted to the pipes varies depending on the type of '''action''', but in any case several ranks of pipes may be supplied by a single windchest. A few of the larger pipes may be "off chest" in order to better fit them into the available space or in order to feature them in the façade. There are two main types of pipe used: ] which use ]s similar to a ] and ] which contain a beating ] in the manner of a ]. | |||

| <gallery widths="200px" heights="200px"> | |||

| The organ's individual ranks are activated by the organist through the ] mechanism. There are many different varieties of stop mechanisms, some proprietary, but the principal distinction is between mechanical and electric mechanisms. Mechanical stop mechanisms connect the stop controls directly to the windchests through a series of wooden or metal rods. When the organist moves the stop control, the rods move. This actuates the mechanism at the windchest that allows or denies wind to the stop. Electric stop mechanisms control the mechanism at the windchest through electronics, which are activated when the organist moves a stop control at the console. | |||

| File:Weingarten Basilika Gabler-Orgel Register rechts.jpg|Stop knobs of the Baroque organ in ], Germany | |||

| File:M.P. Möller Chapel Pipe Organ 1936.jpg|M.P. Möller three-rank chapel organ (1936) | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| ===Console=== | |||

| Once a stop is ''drawn'' (the action of engaging the stop, either by pulling the draw stop out, or rocking the tab switch), there is wind access to the ranks controlled by that stop. Sound is then made by pressing keys down that allows the wind to travel into each individual pipe. When multiple stops are drawn, the depressed key allows air to enter every rank that has been selected. | |||

| {{Main|Organ console}} | |||

| ] crafted by R. A. Colby, Inc.{{efn|Organ built by ], 1940.<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081106213802/http://www.usna.edu/Music/Accessable/organ.html |date=6 November 2008 }}. ]. Retrieved on 4 March 2008.</ref>}}]] | |||

| The controls available to the organist, including the ], ], ], stops, and ] are accessed from the console.<ref> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080801202709/http://www.agohq.org/guide/pages/pages_9_10/console.html |date=1 August 2008 }}. {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20000706193712/http://www.agohq.org/guide/pages/pages_9_10/console.html |date=6 July 2000 }}. Retrieved on 13 August 2008.</ref> The console is either built into the ] or detached from it. | |||

| The choice of stop mechanism depends on the design of the organ and the console. If the console is located farther away from the rest of the organ, a mechanical stop action is harder to implement than when the console and the organ are in closer proximity. The more complicated registration aids, such as thumb and toe pistons, especially those which can be specified to control certain stops require an electrical action, although a rudimentary system is available with a mechanical action. | |||

| ====Keyboards==== | |||

| The organ stops are the origin of the phrase "to pull out all the stops", meaning to make every effort or "to give it all you've got".<ref></ref> | |||

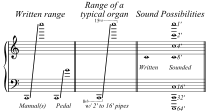

| Keyboards played by the hands are known as '']'' (from the ] ''{{lang|la|}}'', meaning "hand"). The keyboard played by the feet is a '']'' (from the ] ''{{lang|la|, pĕdis}}'', meaning "foot"). Every organ has at least one manual (most have two or more), and most have a pedalboard. Each keyboard is named for a particular division of the organ (a group of ranks) and generally controls only the stops from that division. The ] of the keyboards has varied widely across time and between countries. Most current specifications call for two or more manuals with sixty-one notes (five octaves, from C to c″″) and a pedalboard with thirty or thirty-two notes (two and a half octaves, from C to f′ or g′).{{efn||name=Helmholtz}}<ref> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070927154656/http://www.agohq.org/guide/pages/pages_5_5/frameset01.html |date=27 September 2007 }}. ]. Retrieved on 25 June 2007.</ref> | |||

| ====Couplers==== | |||

| ] in several ways, each of which results in a different timbre: | |||

| A ''coupler'' allows the stops of one division to be played from the keyboard of another division. For example, a coupler labelled "Swell to Great" allows the stops drawn in the Swell division to be played on the Great manual. This coupler is a unison coupler, because it causes the pipes of the Swell division to sound at the same pitch as the keys played on the Great manual. Coupling allows stops from different divisions to be combined to create various tonal effects. It also allows every stop of the organ to be played simultaneously from one manual.<ref name="crumhorn">{{cite web|title=A brief tour of a pipe organ |publisher=Crumhorn Labs |url=http://www.crumhorn-labs.com/Documentation/CurrentUserGuide/HTML/HauptwerkInstallUserGuideFiles/TourOfAPipeOrgan.html |access-date=19 April 2008 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080410182430/http://www.crumhorn-labs.com/Documentation/CurrentUserGuide/HTML/HauptwerkInstallUserGuideFiles/TourOfAPipeOrgan.html |archive-date=10 April 2008 }}</ref> | |||

| *by the material they are made of (wood or metal) | |||

| *by the mechanism of sound production (''flue'' pipes vs. ''reed'' pipes, also called ''labial'' and ''lingual'') | |||

| *by the shape of the pipe (cylindrical, conical, or irregular) | |||

| *by the construction of the ends (open or closed). | |||

| ''Octave couplers'', which add the pipes an octave above (super-octave) or below (sub-octave) each note that is played, may operate on one division only (for example, the Swell super octave, which adds the octave above what is played on the Swell to itself), or act as a coupler to another keyboard (for example, the Swell super-octave to Great, which adds to the Great manual the ranks of the Swell division an octave above what is played).<ref name="crumhorn"/> | |||

| Because a pipe produces only one pitch at a time, ideally there is at least one pipe for each controlling key or pedal, although in some instances, one key may control more than one pipe at a time, such as a mixture, a stop consisting of several ranks of different pitches sounding together. (Occasionally some pipes, especially in the bass, are rigged to provide multiple pitches like big ]s to save space or material: a method employed especially by a few builders in the early ].) | |||

| In addition, larger organs may use ''] off'' couplers, which prevent the stops pulled in a particular division from sounding at their normal pitch. These can be used in combination with octave couplers to create innovative aural effects, and can also be used to rearrange the order of the manuals to make specific pieces easier to play.<ref name="crumhorn"/> | |||

| The sound of a pipe can be altered by use of a device called a ''']'''. This fluctuates the air supply going to the pipes giving a ] effect. | |||

| ====Enclosure and expression pedals==== | |||

| ] in ]. Unlike the rest of the organ—which is located in the gallery at the rear of the church—this division is located in the choir area near the front of the church. In many churches the designation is reversed, with the vocal choir (and its related organ pipes) located in a balcony at the rear of the church.]] | |||

| {{Main|Expression pedal}} | |||

| ] in ], Germany.{{efn|Organ built by Wilhelm Schwarz, 1901}} The expression pedal is visible directly above the pedalboard.]] | |||

| ''Enclosure'' refers to a system that allows for the ] without requiring the addition or subtraction of stops. In a two-manual organ with Great and Swell divisions, the Swell will be enclosed. In larger organs, parts or all of the Choir and Solo divisions may also be enclosed.<ref name="swell">Wicks "Swell division", "Swell shades".</ref> The pipes of an enclosed division are placed in a chamber generally called the ''swell box''. At least one side of the box is constructed from horizontal or vertical palettes known as ''swell shades'', which operate in a similar way to ]; their position can be adjusted from the console. When the swell shades are open, more sound is heard than when they are closed.<ref name="swell"/> Sometimes the shades are exposed, but they are often concealed behind a row of facade-pipes or a grill. | |||

| ====Flue pipes==== | |||

| ''']s''' produce sound the same way as a ]: they are whistles. The definition of a whistle is a sound producing device in which nothing but air molecules move. The majority of organ pipes are flue pipes and they produce the "foundation" sound of an organ. They are used in single-rank unison and mutation stops as well as multi-rank mixtures. | |||

| The most common method of controlling the louvers is the ]. This device is usually placed above the centre of the pedalboard and is configured to rotate away from the organist from a near-vertical position (in which the shades are closed) to a near-horizontal position (in which the shades are open).<ref>Wicks "Expression pedals".</ref> An organ may also have a similar-looking ], found alongside any expression pedals. Pressing the crescendo pedal forward cumulatively activates the stops of the organ, starting with the softest and ending with the loudest; pressing it backward reverses this process.<ref>Wicks "Crescendo pedal".</ref> | |||

| Mostly, flue pipes belong to one of three tonal families: | |||