| Revision as of 08:22, 29 May 2023 editMineSteef2 (talk | contribs)5 editsNo edit summaryTags: Reverted possible BLP issue or vandalism← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 16:51, 8 January 2025 edit undoCodeTalker (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Rollbackers35,081 edits Unbalanced parentheses | ||

| (42 intermediate revisions by 38 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|President of Costa Rica from 2018 to 2022}} | {{Short description|President of Costa Rica from 2018 to 2022}} | ||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=February 2022}} | {{Use dmy dates|date=February 2022}} | ||

| {{ |

{{BLP sources|date=July 2017}} | ||

| {{family name hatnote|Alvarado|Quesada|lang=Spanish}} | {{family name hatnote|Alvarado|Quesada|lang=Spanish}} | ||

| {{Infobox officeholder | {{Infobox officeholder | ||

| | image = Future Affairs Berlin 2019 |

| image = Carlos Alvarado Quesada Future Affairs Berlin 2019.jpg | ||

| | birth_name = Carlos Andrés Alvarado Quesada<ref>{{cite news |last1=Quesada|first1=Andrés|title=Carlos Alvarado |url=https://elpais.com/internacional/2018/05/07/america/1525706014_193325.html |access-date=15 August 2019 |work=] |date=7 May 2018 |language=es}}</ref> | | birth_name = Carlos Andrés Alvarado Quesada<ref>{{cite news |last1=Quesada|first1=Andrés|title=Carlos Alvarado |url=https://elpais.com/internacional/2018/05/07/america/1525706014_193325.html |access-date=15 August 2019 |work=] |date=7 May 2018 |language=es}}</ref> | ||

| | birth_date = {{birth date and age|1980|1|14|df=y}} | | birth_date = {{birth date and age|1980|1|14|df=y}} | ||

| Line 34: | Line 34: | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''Carlos Andrés Alvarado Quesada''' |

'''Carlos Andrés Alvarado Quesada''' ({{IPA|es|ˈkaɾlos alβaˈɾaðo keˈsaða}}; born 14 January 1980) is a Costa Rican politician, writer, journalist, and political scientist who served as the 48th president of ]<ref>{{Cite web |title=Carlos Alvarado Quesada {{!}} The Fletcher School |url=https://fletcher.tufts.edu/people/faculty/carlos-alvarado-quesada |access-date=2024-05-03 |website=fletcher.tufts.edu}}</ref> from 8 May 2018 to 8 May 2022. A member of the ] (PAC), Alvarado previously served as during the presidency of ].<ref name="oecd">{{cite web|title=Carlos Alvarado Quesada|url=https://www.oecd.org/mcm/whos-who/MCM%202016_Costa%20Rica_Carlos%20Alvarado%20Briceno.pdf|website=oecd.org|access-date=28 March 2017}}</ref> | ||

| Alvarado, who was , became the youngest serving Costa Rican president since ] who took office in 1914 at the age of 36. | Alvarado, who was , became the youngest serving Costa Rican president since ], who took office in 1914 at the age of 36. | ||

| ==Education== | ==Education== | ||

| Alvarado holds a ] in communications and a ] in ] from the ]. He was a ] Scholar from 2008 to 2009, earning a master's degree in ] from the Institute of Development Studies at the ] in ], ]. |

Alvarado holds a ] in communications and a ] in ] from the ]. He was a ] Scholar from 2008 to 2009, earning a master's degree in ] from the Institute of Development Studies at the ] in ], ].<ref>{{Cite web|last=IDS|first=University of Sussex and|title=IDS alumnus elected President of Costa Rica|url=http://www.sussex.ac.uk/broadcast/read/44347|access-date=2019-02-13|website=The University of Sussex|archive-date=2018-05-07|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180507085832/http://www.sussex.ac.uk/broadcast/read/44347|url-status=dead}}</ref> | ||

| == Personal life == | == Personal life == | ||

| Alvarado was born into a middle-class family in the |

Alvarado was born into a middle-class family in the Paves District, ] in central Costa Rica, on 14 January 1980. His father, , was an engineer, and his mother, , was a homemaker. He has an older brother named Federico and a younger sister named Irene.<ref>{{Cite web |date=2018-04-08 |title=Carlos Alvarado: President of Costa Rica, Journalist, Writer, Musician, Husband and Father |url=https://news.co.cr/carlos-alvarado-president-of-costa-rica-journalist-writer-musician-father-husband-son/72143/ |access-date=2022-04-08 |website=Costa Rica Star News |language=en-US}}</ref> | ||

| Alvarado met his future wife, ] while riding the |

Alvarado met his future wife, ], while riding the school bus they both used to take to elementary school.<ref name="scd">{{cite news|date=2018-04-02|title=La sancarleña que en un mes será la Primera Dama del país|work=San Carlos Digital|url=https://sancarlosdigital.com/la-sancarlena-que-en-un-mes-sera-la-primera-dama-del-pais/|url-status=live|access-date=2018-11-24|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181124143535/https://sancarlosdigital.com/la-sancarlena-que-en-un-mes-sera-la-primera-dama-del-pais/|archive-date=2018-11-24}}</ref> | ||

| Alvarado is ].<ref>{{cite news|last1=Gómez|first1=Dylan|date=2 February 2019|title="Soy creyente (…) soy católico y mi familia es muy católica", afirma Alvarado ante las críticas|agency=NCR|url=https://ncrnoticias.com/nacionales/soy-creyente-soy-catolico-y-mi-familia-es-muy-catolica-afirma-alvarado-ante-las-criticas-2/|access-date=27 May 2020}}</ref> | Alvarado is ].<ref>{{cite news|last1=Gómez|first1=Dylan|date=2 February 2019|title="Soy creyente (…) soy católico y mi familia es muy católica", afirma Alvarado ante las críticas|agency=NCR|url=https://ncrnoticias.com/nacionales/soy-creyente-soy-catolico-y-mi-familia-es-muy-catolica-afirma-alvarado-ante-las-criticas-2/|access-date=27 May 2020}}</ref> | ||

| Line 50: | Line 50: | ||

| ==Career== | ==Career== | ||

| ===Literary career=== | ===Literary career=== | ||

| In 2006, Alvarado Quesada published the anthology of stories '' |

In 2006, Alvarado Quesada published the anthology of stories ''Transcriptions Infields'' with Pero Azul.<ref name="ecr">{{cite web|title=Carlos Alvarado Quesada|url=http://www.editorialcostarica.com/escritores.cfm?detalle=1067|website=Editorial Costa Rica|access-date=28 March 2017|archive-date=15 July 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200715102416/https://www.editorialcostarica.com/escritores.cfm?detalle=1067|url-status=dead}}</ref> That same year, he obtained the Young Creation Award of ] with the novel ''La Historia de Cornelius Brown''.<ref name="ecr"/> In 2012, he published the historical novel ''Las Possessions,'' which portrays the dark period in Costa Rican history when the government confiscated the properties of ] and ] during ].<ref name="ecr" /> | ||

| ===Early political career=== | ===Early political career=== | ||

| He served as an advisor to the Citizen Action Party's group in the ] in the 2006-2010 period. He was a consultant to the ] of the ] in financing SMEs,<ref name="oecd"/> Department Manager of Dish Care & Air Care (] Latin America), Director of Communication for the presidential campaign of ], professor in the School of Sciences of Collective Communication of the University of Costa Rica and the School of Journalism Of the ].<ref name="oecd"/> During the Solís Rivera administration, he served as Minister of Human Development and Social Inclusion and Executive President of the ], the institution charged with combating poverty and giving state aid to the population with scarce resources. After the resignation of ] as minister, Alvarado was appointed ].<ref name="oecd"/><ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.nacion.com/el-pais/politica/carlos-alvarado-actual-presidente-del-imas-es-el-nuevo-ministro-de-trabajo/ZTDCEYS6XFDEXEQJQBFC4CSZPI/story/|title=Carlos Alvarado, actual presidente del IMAS, es el nuevo ministro de Trabajo|newspaper=]|access-date=1 March 2022}}</ref> | He served as an advisor to the Citizen Action Party's group in the ] in the 2006-2010 period. He was a consultant to the ] of the ] in financing SMEs (]),<ref name="oecd"/> Department Manager of Dish Care & Air Care (] Latin America), Director of Communication for the presidential campaign of ], professor in the School of Sciences of Collective Communication of the ] and the School of Journalism Of the ].<ref name="oecd"/> During the Solís Rivera administration, he served as Minister of Human Development and Social Inclusion and Executive President of the ], the institution charged with combating poverty and giving state aid to the population with scarce resources. After the resignation of ] as minister, Alvarado was appointed ].<ref name="oecd"/><ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.nacion.com/el-pais/politica/carlos-alvarado-actual-presidente-del-imas-es-el-nuevo-ministro-de-trabajo/ZTDCEYS6XFDEXEQJQBFC4CSZPI/story/|title=Carlos Alvarado, actual presidente del IMAS, es el nuevo ministro de Trabajo|newspaper=]|access-date=1 March 2022}}</ref> | ||

| ===President of Costa Rica (2018–2022)=== | ===President of Costa Rica (2018–2022)=== | ||

| {{Multiple issues|section=yes| | {{Multiple issues|section=yes| | ||

| {{ |

{{BLP sources section|date=March 2022}} | ||

| {{Peacock|section|date=March 2022}} | {{Peacock|section|date=March 2022}} | ||

| {{POV section|date=March 2022}} | {{POV section|date=March 2022}} | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] was a major issue in the campaign, after a ruling by the ] required Costa Rica to recognize such unions.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/apr/02/costa-rica-quesada-wins-presidency-in-vote-fought-on-gay-rights|title=Costa Rica: Carlos Alvarado wins presidency in vote fought on gay rights|last=Henley|first=Jon|date=2018-04-02|newspaper=]|language=en|access-date=2018-07-03}}</ref> Alvarado Muñoz campaigned against same-sex marriage, while Alvarado Quesada argued to respect the court's ruling. On 1 April 2018, Alvarado won the ] (second round) with 61%, defeating |

] was a major issue in the campaign, after a ruling by the ] required Costa Rica to recognize such unions.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/apr/02/costa-rica-quesada-wins-presidency-in-vote-fought-on-gay-rights|title=Costa Rica: Carlos Alvarado wins presidency in vote fought on gay rights|last=Henley|first=Jon|date=2018-04-02|newspaper=]|language=en|access-date=2018-07-03}}</ref> Presidential candidate ] campaigned against same-sex marriage, while Alvarado Quesada argued to respect the court's ruling. On 1 April 2018, Alvarado Quesada won the ] (second round) with 61%, defeating Alvarado Muñoz.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.reuters.com/article/us-costarica-election/costa-rica-center-left-easily-wins-presidency-in-vote-fought-on-gay-rights-idUSKBN1H80XC|title=Costa Rica center-left easily wins presidency in vote fought on gay rights|publisher=Reuters|date=1 April 2018|author1=David Alire Garcia|author2=Enrique Andres Pretel}}</ref> He was sworn into office on 8 May 2018.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Chevening Alumnus Carlos Alvarado becomes 48th president of Costa Rica {{!}} Chevening |url=https://www.chevening.org/news/chevening-alumnus-carlos-alvarado-becomes-48th-president-of-costa-rica/ |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220317073855/https://www.chevening.org/news/chevening-alumnus-carlos-alvarado-becomes-48th-president-of-costa-rica/ |archive-date=2022-03-17 |access-date=2022-03-18 |language=en}}</ref> | ||

| As president, Carlos Alvarado Quesada focused on ] Costa Rica's economy. He set a goal for the country to achieve zero net emissions by the year 2050.<ref>{{Cite web |date=4 March 2019 |title=Costa Rica Commits to Fully Decarbonize by 2050 |url=https://unfccc.int/news/costa-rica-commits-to-fully-decarbonize-by-2050 |access-date=7 June 2022 |website=United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change}}</ref> He planned to build an electric rail-based public transit system for the capital, ] since 40% of the country's ] come from transportation.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.reuters.com/article/us-costa-rica-climatechange-transportati-idUSKCN1QE253|title=Costa Rica launches 'unprecedented' push for zero emissions by 2050|date=2019-02-25|work=Reuters|access-date=2019-04-02|language=en}}</ref> On 24 February 2019, he launched a plan to fully decarbonize the country's economy, in a ceremony alongside ], the Costa Rican former UNFCCC head.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.theclimategroup.org/news/costa-rica-launches-plan-become-world-s-first-decarbonized-country|title=Costa Rica launches plan to become the world's first decarbonized country|date=2019-02-25|website=The Climate Group|language=en|access-date=2019-04-02|archive-date=2020-07-27|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200727101224/https://www.theclimategroup.org/news/costa-rica-launches-plan-become-world-s-first-decarbonized-country|url-status=dead}}</ref> At this event, he described decarbonization as "the great challenge of our generation," and declared that "Costa Rica must be among the first countries to achieve it, if not the first."<ref name=":0">{{Cite web|url=https://unfccc.int/news/costa-rica-commits-to-fully-decarbonize-by-2050|title=Costa Rica Commits to Fully Decarbonize by 2050 {{!}} UNFCCC|website=Unfccc.int|access-date=2019-04-02}}</ref> | As president, Carlos Alvarado Quesada focused on ] Costa Rica's economy. He set a goal for the country to achieve zero net emissions by the year 2050.<ref>{{Cite web |date=4 March 2019 |title=Costa Rica Commits to Fully Decarbonize by 2050 |url=https://unfccc.int/news/costa-rica-commits-to-fully-decarbonize-by-2050 |access-date=7 June 2022 |website=United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change}}</ref> He planned to build an electric rail-based public transit system for the capital, ] since 40% of the country's ] come from transportation.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.reuters.com/article/us-costa-rica-climatechange-transportati-idUSKCN1QE253|title=Costa Rica launches 'unprecedented' push for zero emissions by 2050|date=2019-02-25|work=Reuters|access-date=2019-04-02|language=en}}</ref> On 24 February 2019, he launched a plan to fully decarbonize the country's economy, in a ceremony alongside ], the Costa Rican former UNFCCC head.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.theclimategroup.org/news/costa-rica-launches-plan-become-world-s-first-decarbonized-country|title=Costa Rica launches plan to become the world's first decarbonized country|date=2019-02-25|website=The Climate Group|language=en|access-date=2019-04-02|archive-date=2020-07-27|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200727101224/https://www.theclimategroup.org/news/costa-rica-launches-plan-become-world-s-first-decarbonized-country|url-status=dead}}</ref> At this event, he described decarbonization as "the great challenge of our generation," and declared that "Costa Rica must be among the first countries to achieve it, if not the first."<ref name=":0">{{Cite web|url=https://unfccc.int/news/costa-rica-commits-to-fully-decarbonize-by-2050|title=Costa Rica Commits to Fully Decarbonize by 2050 {{!}} UNFCCC|website=Unfccc.int|access-date=2019-04-02}}</ref> | ||

| In December 2018, he pushed through a law that raised taxes and reduced public sector salaries, which he justified due to the country's poor economic situation. His actions resulted in the largest general strike in twenty years.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.laizquierdadiario.com/Costa-Rica-Jornada-de-movilizacion-en-la-segunda-semana-de-huelga-contra-la-reforma-fiscal|title = Costa Rica: Jornada de movilización en la segunda semana de huelga contra la reforma fiscal|website=Laizquierdadiario.com}}</ref> | |||

| During the ], he decided to maintain a ] economic policy with high social costs. The government has thus cut public spending, especially in the education budget. Unemployment has risen from 8.1% in 2017 to 14.4% by the end of 2021, 23% of the population lives below the poverty line and the public debt has reached 70% of GDP, one of the highest rates in Latin America. While this policy was supported in Congress by the ] (PNL) and the ] (PUSC), the two main traditional parties, it has caused the government to lose the support of civil servants, academics, the left, and a large part of the middle class. According to ], Costa Rica is expected to be the Latin American country, along with Brazil, that will have the most difficulty in reviving its economy after the pandemic.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.lemonde.fr/international/article/2022/02/06/l-indecision-domine-l-electorat-avant-les-elections-au-costa-rica_6112522_3210.html|title=L'indécision domine l'électorat avant les élections au Costa Rica|date=6 February 2022|access-date=1 March 2022|newspaper=]}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://ticotimes.net/2022/02/06/a-poorer-costa-rica-the-challenge-of-the-next-governor|title=A Poorer Costa Rica, the Challenge of the Next Governor|date=6 February 2022|website=Ticotimes.net|access-date=1 March 2022}}</ref> | During the ], he decided to maintain a ] economic policy with high social costs. The government has thus cut public spending, especially in the education budget. Unemployment has risen from 8.1% in 2017 to 14.4% by the end of 2021, 23% of the population lives below the poverty line and the public debt has reached 70% of GDP, one of the highest rates in Latin America. While this policy was supported in Congress by the ] (PNL) and the ] (PUSC), the two main traditional parties, it has caused the government to lose the support of civil servants, academics, the left, and a large part of the middle class. According to ], Costa Rica is expected to be the Latin American country, along with Brazil, that will have the most difficulty in reviving its economy after the pandemic.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.lemonde.fr/international/article/2022/02/06/l-indecision-domine-l-electorat-avant-les-elections-au-costa-rica_6112522_3210.html|title=L'indécision domine l'électorat avant les élections au Costa Rica|date=6 February 2022|access-date=1 March 2022|newspaper=]}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://ticotimes.net/2022/02/06/a-poorer-costa-rica-the-challenge-of-the-next-governor|title=A Poorer Costa Rica, the Challenge of the Next Governor|date=6 February 2022|website=Ticotimes.net|access-date=1 March 2022}}</ref> | ||

| Line 73: | Line 73: | ||

| At the end of Carlos Alvarado's presidential term, he had a twelve percent approval rating.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.larepublica.net/noticia/imagen-de-carlos-alvarado-llega-a-su-punto-mas-bajo-en-cuatro-anos-y-ahora-un-72-tiene-una-opinion-negativa-de-su-gestion|title=Imagen de Carlos Alvarado llega a su punto más bajo en cuatro años y ahora un 72% tiene una opinión negativa de su gestión|website=Larepublica.net|access-date=1 March 2022}}</ref> His successor, ], assumed office on 8 May 2022. | At the end of Carlos Alvarado's presidential term, he had a twelve percent approval rating.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.larepublica.net/noticia/imagen-de-carlos-alvarado-llega-a-su-punto-mas-bajo-en-cuatro-anos-y-ahora-un-72-tiene-una-opinion-negativa-de-su-gestion|title=Imagen de Carlos Alvarado llega a su punto más bajo en cuatro años y ahora un 72% tiene una opinión negativa de su gestión|website=Larepublica.net|access-date=1 March 2022}}</ref> His successor, ], assumed office on 8 May 2022. | ||

| ===After the presidency=== | |||

| During his government, Alvarado combined his national activities with his participation in international events, both in-person and virtual, on Costa Rica's global positioning as a leading nation in sustainability, energy, and climate change mitigation. Alvarado was invited by organizations such as Chatham House,<ref>{{Cite web |date=2021-11-03 |title=In conversation with Carlos Alvarado Quesada |url=https://www.chathamhouse.org/events/all/members-event/conversation-carlos-alvarado-quesada |website=www.chathamhouse.org}}</ref> Atlantic Council,<ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/event/lota-a-conversation-with-carlos-alvarado/ | title=Leaders of the Americas: A conversation with H.E. Carlos Alvarado, President of Costa Rica }}</ref> and DC Dialogues, moderated by ] professor and CNN en Español columnist ].<ref>{{cite web | url=https://plas.princeton.edu/events/2021/prioritizing-biodiversity-and-green-energy-conversation-president-costa-rica-carlos | title=Prioritizing Biodiversity and Green Energy: A Conversation with President of Costa Rica Carlos Alvarado }}</ref><ref>{{cite web | url=https://geovannyvicente.com/en/dcdialogues-prioritizing-biodiversity-and-green-energy-a-conversation-with-president-of-costa-rica-carlos-alvarado-nyu-washington-dc/ | title=[:en]#DCDialogues: Prioritizing Biodiversity and Green Energy: A Conversation with President of Costa Rica Carlos Alvarado - NYU Washington DC[:es]#DCDialogues: Priorizando la Biodiversidad y la Energía Verde: Una Conversación con el Presidente de Costa Rica Carlos Alvarado - NYU Washington DC[:] | date=12 July 2024 }}</ref> After his presidency, Alvarado continued with this academic agenda, serving as a keynote speaker for events at institutions such as ],<ref>{{cite web | url=https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/newsplus/former-costa-rican-president-alvarado-describes-his-countrys-public-health-successes/ | title=Former Costa Rican President Alvarado describes his country's public health successes | date=27 October 2022 }}</ref> the Inter-American Investment and Nature Forum (IABNF), organized by the Inter-American Institute of Justice and Sustainability (IIJS), where he has shared the stage with international leaders like ], among others.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Inaugural IABNF 2023 sets biodiversity agenda |url=https://latam-news.co/news/inaugural-iabnf-2023-sets-biodiversity-agenda |access-date=2024-09-20 |website=LatAm Investor |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.ii-js.org/iabnf2023-speakers/ | title=IABNF 2023 Speaker Lineup }}</ref> | |||

| Currently, he is a professor at the Graduate School of Global Affairs at ] in Massachusetts, United States.<ref>{{cite web | url=https://fletcher.tufts.edu/people/faculty/carlos-alvarado-quesada | title=Carlos Alvarado Quesada | the Fletcher School }}</ref> | |||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| Line 117: | Line 123: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 16:51, 8 January 2025

President of Costa Rica from 2018 to 2022

| This biography of a living person needs additional citations for verification. Please help by adding reliable sources. Contentious material about living persons that is unsourced or poorly sourced must be removed immediately from the article and its talk page, especially if potentially libelous. Find sources: "Carlos Alvarado Quesada" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (July 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| Carlos Alvarado Quesada | |

|---|---|

| |

| 48th President of Costa Rica | |

| In office 8 May 2018 – 8 May 2022 | |

| Vice President | Epsy Campbell Barr Marvin Rodríguez Cordero |

| Preceded by | Luis Guillermo Solís |

| Succeeded by | Rodrigo Chaves Robles |

| Minister of Labor and Social Security | |

| In office 28 March 2016 – 19 January 2017 | |

| President | Luis Guillermo Solís |

| Preceded by | Víctor Morales Mora |

| Succeeded by | Alfredo Hasbum Camacho |

| Minister of Human Development and Social Inclusion | |

| In office 10 July 2014 – 29 March 2016 | |

| President | Luis Guillermo Solís |

| Preceded by | Fernando Marín Rojas |

| Succeeded by | Emilio Arias Rodríguez |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Carlos Andrés Alvarado Quesada (1980-01-14) 14 January 1980 (age 44) San José, Costa Rica |

| Political party | Citizens' Action Party |

| Spouse |

Claudia Dobles Camargo

(m. 2010) |

| Children | Gabriel |

| Education | University of Costa Rica (BA, MA) University of Sussex (MA) |

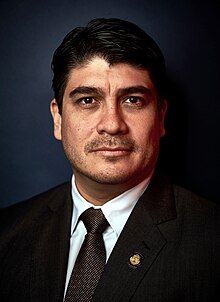

Carlos Andrés Alvarado Quesada (Spanish pronunciation: [ˈkaɾlos alβaˈɾaðo keˈsaða]; born 14 January 1980) is a Costa Rican politician, writer, journalist, and political scientist who served as the 48th president of Costa Rica from 8 May 2018 to 8 May 2022. A member of the Citizens' Action Party (PAC), Alvarado previously served as Minister of Labor and Social Security during the presidency of Luis Guillermo Solís.

Alvarado, who was 38 years old at the time of his presidential inauguration, became the youngest serving Costa Rican president since Alfredo González Flores, who took office in 1914 at the age of 36.

Education

Alvarado holds a bachelor's degree in communications and a master's degree in political science from the University of Costa Rica. He was a Chevening Scholar from 2008 to 2009, earning a master's degree in development studies from the Institute of Development Studies at the University of Sussex in Falmer, England.

Personal life

Alvarado was born into a middle-class family in the Paves District, San José canton in central Costa Rica, on 14 January 1980. His father, Alejandro Alvarado Induni, was an engineer, and his mother, Adelia Quesada Alvarado, was a homemaker. He has an older brother named Federico and a younger sister named Irene.

Alvarado met his future wife, Claudia Dobles Camargo, while riding the school bus they both used to take to elementary school.

Alvarado is Roman Catholic.

Career

Literary career

In 2006, Alvarado Quesada published the anthology of stories Transcriptions Infields with Pero Azul. That same year, he obtained the Young Creation Award of Editorial Costa Rica with the novel La Historia de Cornelius Brown. In 2012, he published the historical novel Las Possessions, which portrays the dark period in Costa Rican history when the government confiscated the properties of Germans and Italians during World War II.

Early political career

He served as an advisor to the Citizen Action Party's group in the Legislative Assembly of Costa Rica in the 2006-2010 period. He was a consultant to the Institute of Development Studies of the United Kingdom in financing SMEs (small and medium-sized enterprises), Department Manager of Dish Care & Air Care (Procter & Gamble Latin America), Director of Communication for the presidential campaign of Luis Guillermo Solís, professor in the School of Sciences of Collective Communication of the University of Costa Rica and the School of Journalism Of the Universidad Latina de Costa Rica. During the Solís Rivera administration, he served as Minister of Human Development and Social Inclusion and Executive President of the Joint Social Welfare Institute, the institution charged with combating poverty and giving state aid to the population with scarce resources. After the resignation of Víctor Morales Mora as minister, Alvarado was appointed minister of Labor.

President of Costa Rica (2018–2022)

This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Same-sex marriage was a major issue in the campaign, after a ruling by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights required Costa Rica to recognize such unions. Presidential candidate Fabricio Alvarado Muñoz campaigned against same-sex marriage, while Alvarado Quesada argued to respect the court's ruling. On 1 April 2018, Alvarado Quesada won the presidential election (second round) with 61%, defeating Alvarado Muñoz. He was sworn into office on 8 May 2018.

As president, Carlos Alvarado Quesada focused on decarbonizing Costa Rica's economy. He set a goal for the country to achieve zero net emissions by the year 2050. He planned to build an electric rail-based public transit system for the capital, San José since 40% of the country's greenhouse gas emissions come from transportation. On 24 February 2019, he launched a plan to fully decarbonize the country's economy, in a ceremony alongside Christiana Figueres, the Costa Rican former UNFCCC head. At this event, he described decarbonization as "the great challenge of our generation," and declared that "Costa Rica must be among the first countries to achieve it, if not the first."

In December 2018, he pushed through a law that raised taxes and reduced public sector salaries, which he justified due to the country's poor economic situation. His actions resulted in the largest general strike in twenty years.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, he decided to maintain a neoliberal economic policy with high social costs. The government has thus cut public spending, especially in the education budget. Unemployment has risen from 8.1% in 2017 to 14.4% by the end of 2021, 23% of the population lives below the poverty line and the public debt has reached 70% of GDP, one of the highest rates in Latin America. While this policy was supported in Congress by the National Liberation Party (PNL) and the Social Christian Unity Party (PUSC), the two main traditional parties, it has caused the government to lose the support of civil servants, academics, the left, and a large part of the middle class. According to ECLAC, Costa Rica is expected to be the Latin American country, along with Brazil, that will have the most difficulty in reviving its economy after the pandemic.

The country's political life has been marked by corruption cases, both in government and in opposition parties, which have contributed to the discrediting of the political class among a part of the population. Ministers, former ministers, and mayors have been implicated in corruption cases involving embezzlement and bribery for multi-million dollar public works contracts. In 2021, six mayors, including the mayor of the capital San José, were arrested. Some cases even revealed the penetration of political circles by drug trafficking groups.

At the end of Carlos Alvarado's presidential term, he had a twelve percent approval rating. His successor, Rodrigo Chaves Robles, assumed office on 8 May 2022.

After the presidency

During his government, Alvarado combined his national activities with his participation in international events, both in-person and virtual, on Costa Rica's global positioning as a leading nation in sustainability, energy, and climate change mitigation. Alvarado was invited by organizations such as Chatham House, Atlantic Council, and DC Dialogues, moderated by Columbia University professor and CNN en Español columnist Geovanny Vicente. After his presidency, Alvarado continued with this academic agenda, serving as a keynote speaker for events at institutions such as Harvard University, the Inter-American Investment and Nature Forum (IABNF), organized by the Inter-American Institute of Justice and Sustainability (IIJS), where he has shared the stage with international leaders like Claudia S. de Windt, among others.

Currently, he is a professor at the Graduate School of Global Affairs at Tufts University in Massachusetts, United States.

References

- Quesada, Andrés (7 May 2018). "Carlos Alvarado". El País (in Spanish). Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- "Carlos Alvarado Quesada | The Fletcher School". fletcher.tufts.edu. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ "Carlos Alvarado Quesada" (PDF). oecd.org. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- IDS, University of Sussex and. "IDS alumnus elected President of Costa Rica". The University of Sussex. Archived from the original on 7 May 2018. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- "Carlos Alvarado: President of Costa Rica, Journalist, Writer, Musician, Husband and Father". Costa Rica Star News. 8 April 2018. Retrieved 8 April 2022.

- "La sancarleña que en un mes será la Primera Dama del país". San Carlos Digital. 2 April 2018. Archived from the original on 24 November 2018. Retrieved 24 November 2018.

- Gómez, Dylan (2 February 2019). ""Soy creyente (…) soy católico y mi familia es muy católica", afirma Alvarado ante las críticas". NCR. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ^ "Carlos Alvarado Quesada". Editorial Costa Rica. Archived from the original on 15 July 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- "Carlos Alvarado, actual presidente del IMAS, es el nuevo ministro de Trabajo". La Nación. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- Henley, Jon (2 April 2018). "Costa Rica: Carlos Alvarado wins presidency in vote fought on gay rights". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- David Alire Garcia; Enrique Andres Pretel (1 April 2018). "Costa Rica center-left easily wins presidency in vote fought on gay rights". Reuters.

- "Chevening Alumnus Carlos Alvarado becomes 48th president of Costa Rica | Chevening". Archived from the original on 17 March 2022. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- "Costa Rica Commits to Fully Decarbonize by 2050". United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. 4 March 2019. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- "Costa Rica launches 'unprecedented' push for zero emissions by 2050". Reuters. 25 February 2019. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- "Costa Rica launches plan to become the world's first decarbonized country". The Climate Group. 25 February 2019. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- "Costa Rica Commits to Fully Decarbonize by 2050 | UNFCCC". Unfccc.int. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- "Costa Rica: Jornada de movilización en la segunda semana de huelga contra la reforma fiscal". Laizquierdadiario.com.

- "L'indécision domine l'électorat avant les élections au Costa Rica". Le Monde. 6 February 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- "A Poorer Costa Rica, the Challenge of the Next Governor". Ticotimes.net. 6 February 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- "L'indécision domine l'électorat avant les élections au Costa Rica". Le Monde. 6 February 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- "Imagen de Carlos Alvarado llega a su punto más bajo en cuatro años y ahora un 72% tiene una opinión negativa de su gestión". Larepublica.net. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- "In conversation with Carlos Alvarado Quesada". www.chathamhouse.org. 3 November 2021.

- "Leaders of the Americas: A conversation with H.E. Carlos Alvarado, President of Costa Rica".

- "Prioritizing Biodiversity and Green Energy: A Conversation with President of Costa Rica Carlos Alvarado".

- "[:en]#DCDialogues: Prioritizing Biodiversity and Green Energy: A Conversation with President of Costa Rica Carlos Alvarado - NYU Washington DC[:es]#DCDialogues: Priorizando la Biodiversidad y la Energía Verde: Una Conversación con el Presidente de Costa Rica Carlos Alvarado - NYU Washington DC[:]". 12 July 2024.

- "Former Costa Rican President Alvarado describes his country's public health successes". 27 October 2022.

- "Inaugural IABNF 2023 sets biodiversity agenda". LatAm Investor. Retrieved 20 September 2024.

- "IABNF 2023 Speaker Lineup".

- "Carlos Alvarado Quesada | the Fletcher School".

External links

- Biography by CIDOB (in Spanish)

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded byFernando Marín Rojas | Human Development and Social Inclusion 2014–2016 |

Succeeded byEmilio Arias Rodríguez |

| Preceded byVíctor Morales Mora | Minister of Labor and Social Security 2016–2017 |

Succeeded byAlfredo Hasbum Camacho |

| Preceded byLuis Guillermo Solís | President of Costa Rica 2018–2022 |

Succeeded byRodrigo Chaves Robles |

| Party political offices | ||

| Preceded byLuis Guillermo Solís | Leader of the Citizens' Action Party 2018–present |

Incumbent |

| PAC nominee for President of Costa Rica 2018 |

Succeeded byWelmer Ramos González | |

| Current heads of state in Central American countries | |

|---|---|

| Citizens' Action Party | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Partido Acción Ciudadana | |||||||||||

| National Executive Committee |

| ||||||||||

| 2014-2018 Deputies (13 / 57) |

| ||||||||||

| Notable members |

| ||||||||||

| Issues and beliefs | |||||||||||