| Revision as of 09:09, 13 July 2023 editAsarlaí (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers33,686 edits →top: trimmed some unneeded wording← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 01:06, 12 January 2025 edit undoSkyerise (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers141,585 edits Undid revision 1268724707 by 2600:1702:35F0:A1D0:88A9:4B8C:526D:96CC (talk) neither change necessaryTag: Undo | ||

| (871 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Practices believed to use supernatural powers}} | |||

| <!-- ############ NOTE ############ | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=July 2023}} | |||

| {{use American English|date=July 2023}} | |||

| This article is primarily about the traditional | |||

| {{this|worldwide views of witchcraft|an overview of Neopagan witchcraft|Neopagan witchcraft|the modern pagan religion|Wicca|other uses|Witchcraft (disambiguation)}} | |||

| and most common meaning of 'witchcraft' | |||

| {{redirect|Witch|other uses|Witch (disambiguation)}} | |||

| worldwide, which is the use of harmful magic. | |||

| ]'s painting ''The Magic Circle'' (1886)]] | |||

| Newer positive meanings are mentioned here, | |||

| {{Witchcraft sidebar|all}} | |||

| but are not the focus of the article. The | |||

| {{Magic sidebar|Forms}} | |||

| modern religion is covered on the article WICCA. | |||

| '''Witchcraft''' is the use of alleged ] powers of ]. A '''witch''' is a practitioner of witchcraft. Traditionally, "witchcraft" means the use of magic or supernatural powers to inflict harm or misfortune on others, and this remains the most common and widespread meaning.{{sfnmp|1a1=Hutton|1y=2017|1p=ix|2a1=Thomas|2y=1997|2p=519}} According to ''Encyclopedia Britannica'',<!--summarizing recent sources--> "Witchcraft thus defined exists more in the imagination", but it "has constituted for many cultures a viable explanation of evil in the world".<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |first1=Jeffrey Burton |last1=Russell |first2=Ioan M. |last2=Lewis |date=2023 |title=Witchcraft |encyclopedia=Encyclopedia Britannica |url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/witchcraft |access-date=2023-07-28 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230628125818/https://www.britannica.com/topic/witchcraft |archive-date=2023-06-28 |quote=Although defined differently in disparate historical and cultural contexts, witchcraft has often been seen, especially in the West, as the work of crones who meet secretly at night, indulge in cannibalism and orgiastic rites with the Devil, or Satan, and perform black magic. Witchcraft thus defined exists more in the imagination of contemporaries than in any objective reality. Yet this stereotype has a long history and has constituted for many cultures a viable explanation of evil in the world.}}</ref> The belief in witchcraft has been found throughout history in a great number of societies worldwide. Most of these societies have used ] against witchcraft, and have shunned, banished, imprisoned, physically punished or killed alleged witches. ]s use the term "witchcraft" for similar beliefs about harmful ] practices in different cultures, and these societies often use the term when speaking in English.<ref name="Singh-2021">{{Cite journal |last=Singh |first=Manvir |date=2021-02-02 |title=Magic, Explanations, and Evil: The Origins and Design of Witches and Sorcerers |url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/349617609 |journal=Current Anthropology |volume=62 |issue=1 |pages=2–29 |doi=10.1086/713111 |s2cid=232214522 |issn=0011-3204 |access-date=2021-04-28 |archive-date=2021-07-18 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210718192653/https://www.researchgate.net/publication/349617609_Magic_Explanations_and_Evil_The_Origins_and_Design_of_Witches_and_Sorcerers |url-status=live }}</ref>{{sfnp|Thomas|1997|p=519}}<ref name="Perrone-1993">{{Cite book |last1=Perrone |first1=Bobette |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ApJayEh43ZcC&pg=PA189 |title=Medicine women, curanderas, and women doctors |last2=Stockel |first2=H. Henrietta |last3=Krueger |first3=Victoria |date=1993 |publisher=University of Oklahoma Press |isbn=978-0806125121 |page=189 |access-date=8 October 2010 |archive-date=23 April 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170423165056/https://books.google.com/books?id=ApJayEh43ZcC&pg=PA189 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Belief in witchcraft as malevolent magic is attested from ], and ], belief in witches ]. In ] and ], accused witches were usually women<ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.cam.ac.uk/stories/witchcraft-work-women | title=Witchcraft accusations were an 'occupational hazard' for female workers in early modern England | date=19 September 2023 }}</ref> who were believed to have secretly used ] ('']'') against their own community. Usually, accusations of witchcraft were made by neighbors of accused witches, and followed from social tensions. Witches were sometimes said to have communed with ]s or ], though anthropologist ] notes that such accusations were mainly made against perceived "enemies of the Church".<ref>{{cite book |last=La Fontaine |first=J. |year=2016 |title=Witches and Demons: A Comparative Perspective on Witchcraft and Satanism |publisher=Berghahn Books |isbn=978-1785330865 |pages=33–34}}</ref> It was thought witchcraft could be thwarted by ], provided by ']' or 'wise people'. Suspected witches were often prosecuted and punished, if found guilty or simply believed to be guilty. European ]s and ] led to tens of thousands of executions. While magical healers and ] were sometimes accused of witchcraft themselves,{{sfnp|Davies|2003|pp=7–13}}{{sfnp|Thomas|1997|p=519}}<ref>{{cite book |last1=Riddle |first1=John M. |title=Eve's Herbs: A History of Contraception and Abortion in the West |date=1997 |publisher=Harvard University Press |location=Cambridge, Mass. |isbn=0674270266 |pages=110–119}}</ref>{{sfnp|Ehrenreich|English|2010|pp=}} they made up a minority of those accused. European belief in witchcraft gradually dwindled during and after the ]. | |||

| ############################### --> | |||

| {{Short description|Type of magical practice}} | |||

| {{Other uses|Witchcraft (disambiguation)|Witch (disambiguation)}}{{for|the modern pagan religion|Wicca}} | |||

| {{pp-protected|reason=Persistent ], which always resumes when protection expires.|small=yes}} | |||

| Many ] belief systems that include the concept of witchcraft likewise define witches as malevolent, and seek healers (such as ] and ]s) to ward-off and undo bewitchment.<ref>Demetrio, F. R. (1988). Philippine Studies Vol. 36, No. 3: Shamans, Witches and Philippine Society, pp. 372–380. Ateneo de Manila University.</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Tan |first=Michael L. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=EktzHrfup1UC |title=Revisiting Usog, Pasma, Kulam |publisher=University of the Philippines Press |year=2008 |isbn=978-9715425704 |access-date=2020-09-17 |archive-date=2021-01-26 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210126013249/https://books.google.com/books?id=EktzHrfup1UC |url-status=live }}</ref> Some African and Melanesian peoples believe witches are driven by an evil spirit or substance inside them. ] takes place in parts of Africa and Asia. | |||

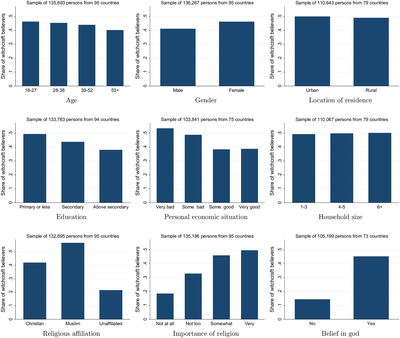

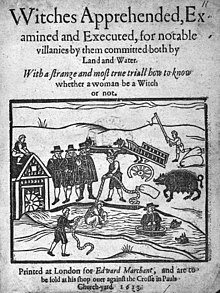

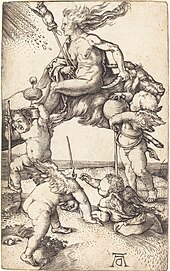

| ]'' by ] (woodcut), 1508]] | |||

| '''Witchcraft''' is the use of ] or ] powers.<ref>https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/witchcraft</ref><ref>https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/witchcraft</ref><ref>https://www.dictionary.com/browse/witchcraft</ref> Someone who uses witchcraft is a '''witch'''.{{notetag|In contemporary Western culture, some followers of the neo-pagan religion ''']''' and its offshoots self-identify as 'witches', redefining 'witchcraft' as positive magic. The focus of this article is the traditional and most common meaning of the term worldwide.}}<ref>https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/witch</ref><ref>https://www.dictionary.com/browse/witch</ref> Traditionally, "witchcraft" means the use of magic or supernatural powers to inflict harm or misfortune on others, and this remains the most common and widespread meaning.<ref name="Hutton 2017 intro">{{Cite book |last=Hutton |first=Ronald |title=The Witch: A History of Fear, from Ancient Times to the Present |date=2017 |publisher=] |page=ix |author-link=Ronald Hutton |quote=What is a witch? The standard scholarly definition of one was summed up in 1978 by a leading expert in the anthropology of religion, Rodney Needham, as 'someone who causes harm to others by mystical means'. In stating this, he was self-consciously not providing a personal view of the matter, but summing up an established scholarly consensus When the only historian of the European trials to set them systematically in a global context in recent years, Wolfgang Behringer, undertook his task, he termed witchcraft 'a generic term for all kinds of evil magic and sorcery, as perceived by contemporaries'. Again, in doing so he was self-consciously perpetuating a scholarly norm. That usage has persisted till the present among anthropologists and historians The discussed above seems still to be the most widespread and frequent. The use of 'witch' to mean a worker of harmful magic has not only been used more commonly and generally, but seems to have been employed by those with a genuine belief in magic...}}</ref><ref name="Thomas519">{{Cite book |last=Thomas |first=Keith |title=Religion and the Decline of Magic |date=1997 |publisher=] |isbn=978-0297002208 |location=Oxford, England |page=519 |author-link=Keith Thomas (historian) |quote='At this day', wrote Reginald Scot in 1584, 'it is indifferent to say in the English tongue, "she is a witch" or "she is a wise woman".' Nevertheless, it is possible to isolate that kind of 'witchcraft' which involved the employment (or presumed employment) of some occult means of doing harm to other people in a way which was generally disapproved of. In this sense the belief in witchcraft can be defined as the attribution of misfortune to occult human agency. A witch was a person of either sex (but more often female) who could mysteriously injure other people.}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Gershman |first1=Boris |title=Witchcraft beliefs around the world: An exploratory analysis |journal=PLOS ONE |date=23 November 2022 |volume=17 |issue=11 |pages=e0276872 |doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0276872|pmid=36417350 |pmc=9683553 |bibcode=2022PLoSO..1776872G |doi-access=free |quote=Beliefs in witchcraft, defined as an ability of certain people to intentionally cause harm via supernatural means, have been documented all over the world, both recently and in the distant past. This paper presents a new global dataset on contemporary witchcraft beliefs that covers countries and territories representing roughly one half of the world’s adult population. The data reveal that, far from being a remnant of the past limited to small isolated communities, witchcraft beliefs are highly widespread throughout the modern world. At the same time, there are significant differences in their prevalence within and across nations...}}</ref><ref name="OBO">{{cite web |title=Witchcraft |url=https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/display/document/obo-9780199766567/obo-9780199766567-0029.xml |website=] |quote=Witchcraft refers to a belief in the perpetration of harm by persons through mystical means. Ethnographic studies across the globe have shown that, far from being confined to the distant past of Europe and New England, the belief in witchcraft is widely distributed in time and place—in Africa, Melanesia, the Pacific, Asia, and the Americas. ... The most commonly accepted definition was provided in Evans-Pritchard 1937 Evans-Pritchard defines the former as the innate, inherited ability to cause misfortune or death.}}</ref><ref name="Stein">{{cite book |last1=Stein |first1=Rebecca |last2=Stein |first2=Philip |title=The Anthropology of Religion, Magic, and Witchcraft |date=2017 |publisher=Taylor & Francis |pages=233-234, 244, 248 |quote=When anthropologists speak of witchcraft, they generally refer to individuals who have an innate ability to do evil. The idea of witchcraft as an evil force bringing misfortune to members of a community is found in a great number of societies throughout the world. In these societies witchcraft is evil; there are no good witches. As is common in many societies throughout the world, those accused of witchcraft were primarily people living on the fringes of society. Many were marginalized and powerless women without husbands, brothers, or sons to protect their interests. Others were those who dealt with folk remedies and midwifery. 'When such remedies went bad, and when face-to-face dispute resolution failed, the customers who paid for the cures or the potions might conclude that the purveyor was at fault'. witches are portrayed in a very positive light, which fits only the Wiccan definition.}}</ref><ref>https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/witch</ref> In ] and ], ], accused witches were usually women who were believed to have used '']'' or ] against their own community, and often to have communed with evil beings. It was thought witchcraft could be thwarted by ], which could be provided by ] or ]s. Suspected witches were also intimidated, banished, attacked or killed. Often they would be formally prosecuted and punished, if found guilty or simply believed to be guilty. European ]s and ] led to tens of thousands of executions. In some regions, many of those accused of witchcraft were folk healers or ].<ref name="Riddle">{{cite book |last1=Riddle |first1=John M. |title=Eve's Herbs: A History of Contraception and Abortion in the West |date=1997 |publisher=Harvard University Press |location=Cambridge, Mass. |isbn=0674270266 |pages=110–119}}</ref><ref name="Ehrenreich">{{cite book |last1=Ehrenreich |first1=Barbara |last2=English |first2=Deirdre |title=Witches, Midwives & Nurses: A History of Women Healers |date=2010 |publisher=Feminist Press at CUNY |location=New York |isbn=978-1558616905 |pages=31–59 |edition=Second |url=https://archive.org/details/witchesmidwivesn0000ehre/page/30/mode/2up}}</ref> European belief in witchcraft gradually dwindled during and after the ]. | |||

| Today, followers of certain types of ] identify as witches and use the term "witchcraft" or "]" for their beliefs and practices.<ref name="Doyle White-2016">{{cite book |last=Doyle White |first=Ethan |title=Wicca: History, Belief, and Community in Modern Pagan Witchcraft |publisher=Liverpool University Press |pages=1–9, 73 |year=2016 |isbn=978-1-84519-754-4 }}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Berger |first1=Helen A. |last2=Ezzy |first2=Douglas |date=September 2009 |title=Mass Media and Religious Identity: A Case Study of Young Witches |journal=Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion |volume=48 |issue=3 |pages=501–514 |doi=10.1111/j.1468-5906.2009.01462.x |jstor=40405642| issn = 0021-8294 }}</ref><ref>{{cite contribution |contribution=An Update on Neopagan Witchcraft in America |last=Kelly |first=Aidan A. |author-link=Aidan A. Kelly |title=Perspectives on the New Age |editor1=James R. Lewis |editor2=J. Gordon Melton |pages= |publisher=State University of New York Press |location=Albany|year=1992 |isbn=978-0791412138 |url=https://archive.org/details/perspectivesonne0000unse_m6u6 }}</ref> Other neo-pagans avoid the term due to its negative connotations.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Lewis |first1=James |title=Magical Religion and Modern Witchcraft |date=1996 |publisher=] |page=376}}</ref> | |||

| Contemporary cultures that believe strongly in magic often believe in witchcraft, as in the ability to inflict harm by mystical means.<ref name="OBO"/><ref name="Stein"/><ref name="Russell">{{Cite book |last=Russell |first=Jeffrey Burton |url=https://archive.org/details/witchcraftinmidd0000russ |title=Witchcraft in the Middle Ages |date=1972 |publisher=] |isbn=978-0801492891 |location=Ithaca, New York |pages=–10 |quote=witchcraft definition. |url-access=registration}}</ref><ref name=":5" /> Anthropologists have applied the English term "witchcraft" to similar beliefs and ] practices described by many non-European cultures, and cultures that have adopted the English language often call these practices "witchcraft", as well.<ref name=":5">{{Cite journal |last=Singh |first=Manvir |date=2021-02-02 |title=Magic, Explanations, and Evil: The Origins and Design of Witches and Sorcerers |url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/349617609 |journal=Current Anthropology |volume=62 |issue=1 |pages=2–29 |doi=10.1086/713111 |s2cid=232214522 |issn=0011-3204 |access-date=2021-04-28 |archive-date=2021-07-18 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210718192653/https://www.researchgate.net/publication/349617609_Magic_Explanations_and_Evil_The_Origins_and_Design_of_Witches_and_Sorcerers |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="Thomas" /><ref name="Wilby" /><ref name="PerroneStockel1993" /> As with the cunning-folk in Europe, ] communities that believe in witchcraft define witches as the opposite of their healers and ], who are sought out for protection against witchcraft.<ref name="tosenberger"/><ref name=Demetrio/><ref name="tan"/> ] takes place in parts of Africa and Asia. | |||

| A theory that witchcraft was a survival of a European pagan religion gained popularity in the early 20th century. Known as the ], it has been discredited. A newer theory is that the idea of "witchcraft" developed to explain strange misfortune, similar to ideas such as the ]. | |||

| In ] ], followers of some ] religions, most notably ] and some followers of ] belief systems, may ] as "witches", and use the term "witchcraft" for their ], healing, or ] rituals.<ref name="Huson" /><ref name="Clifton" /><ref name="tosenberger" /><ref name="DJBaC" /><ref name=NewAgeWitchcraft>{{cite contribution |contribution=An Update on Neopagan Witchcraft in America |last=Kelly |first=Aidan A. |author-link=Aidan A. Kelly |title=Perspectives on the New Age |editor1=James R. Lewis |editor2=J. Gordon Melton |pages= |publisher=State University of New York Press |location=Albany|year=1992 |isbn=978-0791412138 |url=https://archive.org/details/perspectivesonne0000unse_m6u6 }}</ref> Other neo-pagans avoid the term due to its negative connotations.<ref name="Lewis 376">{{cite book |last1=Lewis |first1=James |title=Magical Religion and Modern Witchcraft |date=1996 |publisher=] |page=376}}</ref> | |||

| {{TOC limit|3}} | {{TOC limit|3}} | ||

| ==Concept== | ==Concept== | ||

| ]'' by ], |

]'' by ] (woodcut), 1508]] | ||

| The |

The most common meaning of "witchcraft" worldwide is the use of harmful magic.{{sfnp|Hutton|2017|pp=3–4}} Belief in malevolent magic and the concept of witchcraft has lasted throughout recorded history and has been found in cultures worldwide, regardless of development.<ref name="Singh-2021" />{{sfnp|Ankarloo|Clark|2001|p=xiii}} Most societies have feared an ability by some individuals to cause supernatural harm and misfortune to others. This may come from mankind's tendency "to want to assign occurrences of remarkable good or bad luck to agency, either human or superhuman".{{sfnp|Hutton|2017|p=10}} Historians and anthropologists see the concept of "witchcraft" as one of the ways humans have tried to explain strange misfortune.{{sfnp|Hutton|2017|p=10}}<ref name="Moro-2017" /> Some cultures have feared witchcraft much less than others, because they tend to have other explanations for strange misfortune.{{sfnp|Hutton|2017|p=10}} For example, the ] of Ireland and the Scottish Highlands historically held a strong belief in ], who could cause supernatural harm, and witch-hunting was very rare in these regions compared to other regions of the British Isles.{{sfnp|Hutton|2017|p=245}} | ||

| Historian ] outlined five key characteristics ascribed to witches and witchcraft by most cultures that believe in this concept: the use of magic to cause harm or misfortune to others; it was used by the witch against their own community; powers of witchcraft were believed to have been acquired through inheritance or initiation; it was seen as immoral and often thought to involve communion with evil beings; and witchcraft could be thwarted by defensive magic, persuasion, intimidation or physical punishment of the alleged witch.{{sfnp|Hutton|2017|pp=3–4}} | |||

| A common belief worldwide is that witches use objects, words, and gestures to cause supernatural harm, or that they simply have an innate power to do so. Hutton notes that both kinds of practitioners are often believed to exist in the same culture and that the two often overlap, in that someone with an inborn power could wield that power through material objects.{{sfnp|Hutton|2017|pp=19–22}} | |||

| One of the most influential works on witchcraft and concepts of magic was ]'s '']'', a study of ] beliefs published in 1937. This provided definitions for witchcraft which became a convention in anthropology.<ref name="Moro-2017">{{cite book | chapter-url=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/9781118924396.wbiea1915 | doi=10.1002/9781118924396.wbiea1915 | chapter=Witchcraft, Sorcery, and Magic | title=The International Encyclopedia of Anthropology | date=2017 | last1=Moro | first1=Pamela A. | pages=1–9 | isbn=9780470657225 }}</ref> However, some researchers argue that the general adoption of Evans-Pritchard's definitions constrained discussion of witchcraft beliefs, and even broader discussion of ], in ways that his work does not support.<ref name="Mills-2013" /> Evans-Pritchard reserved the term "witchcraft" for the actions of those who inflict harm by their inborn power and used "sorcery" for those who needed tools to do so.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Evans-Pritchard |first=Edward Evan |url=https://archive.org/details/witchcraftoracle00evan/page/8 |title=Witchcraft, Oracles and Magic Among the Azande |date=1937 |publisher=] |isbn=978-0198740292 |location=Oxford |pages= |author-link=E. E. Evans-Pritchard}}</ref> Historians found these definitions difficult to apply to European witchcraft, where witches were believed to use physical techniques, as well as some who were believed to cause harm by thought alone.{{sfnp|Thomas|1997|pp=464–465}}<ref>{{cite book |last1=Ankarloo |first1=Bengt |last2=Henningsen |first2=Gustav |year=1990 |title=Early Modern European Witchcraft: Centres and Peripheries |place=Oxford |publisher=Oxford University Press |pages=1, 14}}</ref> The distinction "has now largely been abandoned, although some anthropologists still sometimes find it relevant to the particular societies with which they are concerned".{{sfnp|Hutton|2017|pp=19–22}} | |||

| ] outlined five key characteristics ascribed to witches and witchcraft by most cultures that believe in the concept. Traditionally, witchcraft was believed to be the use of magic to cause harm or misfortune to others; it was used by the witch against their own community; it was seen as immoral and often thought to involve communion with evil beings; powers of witchcraft were believed to have been acquired through inheritance or initiation; and witchcraft could be thwarted by defensive magic, persuasion, intimidation or physical punishment of the alleged witch.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Hutton |first=Ronald |title=The Witch: A History of Fear, from Ancient Times to the Present |date=2017 |publisher=] |pages=3–4 |author-link=Ronald Hutton}}</ref> | |||

| While most cultures believe witchcraft to be something willful, some Indigenous peoples in Africa and Melanesia believe witches have a substance or an evil spirit in their bodies that drives them to do harm.{{sfnp|Hutton|2017|pp=19–22}} Such substances may be believed to act on their own while the witch is sleeping or unaware.<ref name="Mills-2013">{{cite journal |jstor=42002806 |title=The opposite of witchcraft: Evans-Pritchard and the problem of the person |first=Martin A. |last=Mills |journal=The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute |volume=19 |number=1 |date=March 2013|pages=18–33 |doi=10.1111/1467-9655.12001 }}</ref> The ] people believe women work harmful magic in their sleep while men work it while awake.{{sfnp|Hutton|2017|pp=18–19}} Further, in cultures where substances within the body are believed to grant supernatural powers, the substance may be good, bad, or morally neutral.<ref>{{Cite web | url=https://www.nigerianjournalsonline.com/index.php/najp/article/download/1925/1881 | title=Witchcraft in Africa: malignant or developmental? | website=www.nigerianjournalsonline.com | author=Iniobong Daniel Umotong}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | doi=10.4314/afrrev.v9i3.9 | title=Socio-Missiological Significance of Witchcraft Belief and Practice in Africa | date=2015 | last1=Gbule | first1=NJ | last2=Odili | first2=JU | journal=African Research Review | volume=9 | issue=3 | page=99 | doi-access=free }}</ref> Hutton draws a distinction between those who unwittingly cast the ] and those who deliberately do so, describing only the latter as witches.{{sfnp|Hutton|2017|p=10}} | |||

| The universal or cross-cultural validity of the terms "witch" and "witchcraft" are debated.<ref name="Moro-2017" /> Hutton states: | |||

| Historically, the ] derives from ] ] against it. In medieval and early modern Europe, many common folk who were Christians believed in magic. As opposed to the helpful magic of the ], witchcraft was seen as ] and associated with ] and ]. This often resulted in deaths, ] and ] (casting blame for misfortune),<ref>{{Cite web |last=Russell |first=Jeffrey Burton |title=Witchcraft |url=http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/646051/witchcraft |access-date=June 29, 2013 |website=Britannica.com |archive-date=May 10, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130510105836/http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/646051/witchcraft |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>Pócs 1999, pp. 9–12.</ref> and many years of large scale ] and ], especially in ] Europe, before largely ending during the European ]. Christian views in the modern day are diverse and cover the gamut of views from intense belief and opposition (especially by ]) to non-belief. | |||

| {{blockquote| is, however, only one current usage of the word. In fact, Anglo-American senses of it now take at least four different forms, although the one discussed above seems still to be the most widespread and frequent. The others define the witch figure as any person who uses magic{{nbsp}}... or as the practitioner of nature-based Pagan religion; or as a symbol of independent female authority and resistance to male domination. All have validity in the present.{{sfnp|Hutton|2017|p=10}}}} | |||

| According to the ] on Extrajudicial, ] there is "difficulty of defining 'witches' and 'witchcraft' across cultures{{--}}terms that, quite apart from their connotations in popular culture, may include an array of ] or ] practices".<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.ohchr.org/en/special-procedures/ie-albinism/witchcraft-and-human-rights|title=Witchcraft and human rights|publisher=]}}</ref> | |||

| Many cultures worldwide continue to have a belief in the concept of "witchcraft" or malevolent magic. During the ], many cultures were exposed to the modern Western world via ], usually accompanied and often preceded by intensive ] ''(see "]")''. In these cultures, beliefs about witchcraft were partly influenced by the prevailing Western concepts of the time. ]s, ], and the killing or ] of suspected witches still occur in the modern era.<ref>{{Cite news |last=Pearlman |first=Jonathan |date=11 April 2013 |title=Papua New Guinea urged to halt witchcraft violence after latest 'sorcery' case |work=] |publisher=] |location=London, England |url=https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/australiaandthepacific/papuanewguinea/9987294/Papua-New-Guinea-urged-to-halt-witchcraft-violence-after-latest-sorcery-case.html |access-date=5 April 2018 |archive-date=11 February 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180211174243/http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/australiaandthepacific/papuanewguinea/9987294/Papua-New-Guinea-urged-to-halt-witchcraft-violence-after-latest-sorcery-case.html |url-status=live }}</ref> Suspicion of modern medicine, due to beliefs about illness being caused by witchcraft, continues in many countries, with serious ] consequences. ]<ref name="HIVwitchcraft">{{Cite news |last1=Kielburger |first1=Craig |last2=Kielburger |first2=Marc |date=18 February 2008 |title=HIV in Africa: Distinguishing disease from witchcraft |work=] |publisher=Toronto Star Newspapers Ltd. |location=Toronto, Ontario, Canada |url=https://www.thestar.com/opinion/columnists/2008/02/18/hiv_in_africa_distinguishing_disease_from_witchcraft.html |access-date=18 September 2017 |archive-date=19 October 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171019221301/https://www.thestar.com/opinion/columnists/2008/02/18/hiv_in_africa_distinguishing_disease_from_witchcraft.html |url-status=live }}</ref> and ]<ref>{{Cite web |date=2 August 2014 |title=Ebola outbreak: 'Witchcraft' hampering treatment, says doctor |url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-28625305 |website=] |publisher=BBC |location=London|quote=citing a doctor from ]: 'A widespread belief in witchcraft is hampering efforts to halt the Ebola virus from spreading' |access-date=22 June 2018 |archive-date=18 July 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210718192649/https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/av/health-28625305 |url-status=live }}</ref> are two examples of often-lethal ] ]s whose medical care and ] has been severely hampered by regional beliefs in witchcraft. Other severe medical conditions whose treatment is hampered in this way include ], ], ] and the common severe ] ].<ref>{{Cite journal |title=Social stigma as an epidemiological determinant for leprosy elimination in Cameroon |url=http://www.publichealthinafrica.org/index.php/jphia/article/view/jphia.2011.e10/html_19 |journal=Journal of Public Health in Africa |access-date=2014-08-27 |archive-date=2017-07-31 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170731190043/http://www.publichealthinafrica.org/index.php/jphia/article/view/jphia.2011.e10/html_19 |url-status=dead }}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |last=Akosua |first=Adu |date=3 September 2014 |title=Ebola: Human Rights Group Warns Disease Is Not Caused By Witchcraft |work=The Ghana-Italy News |url=http://www.theghana-italynews.com/index.php/component/k2/item/955-ebola-human-rights-group-warns-disease-is-not-caused-by-witchcraft |url-status=dead |access-date=31 October 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140903134240/http://www.theghana-italynews.com/index.php/component/k2/item/955-ebola-human-rights-group-warns-disease-is-not-caused-by-witchcraft |archive-date=3 September 2014}}</ref> | |||

| Anthropologist ] notes that the terms "witchcraft" and "witch" are used differently by scholars and the general public in at least four ways.<ref name="Moro-2017" /> Neopagan writer ] proposed dividing witches into even more distinct types including, but not limited to: Neopagan, Feminist, ], ], Classical, Family Traditions, Immigrant Traditions, and Ethnic.{{sfnp|Adler|2006|pp=65–68}} | |||

| From the mid-20th century, "Witchcraft" was adopted as the name of a ] religion, now known as ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Adler |first=Margot |title=Drawing Down the Moon: Witches, Druids, Goddess-Worshippers, and Other Pagans in America Today |date=1979 |publisher=] |location=New York City |pages=45–47, 84–85, 105 |oclc=515560 |author-link=Margot Adler}}</ref> Its creators believed in the ']', that accused witches had actually been followers of a surviving pagan religion, but this 'witch-cult' theory is now discredited.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Hutton |first=Ronald |title=The Witch: A History of Fear, from Ancient Times to the Present |date=2017 |publisher=] |page=121 |author-link=Ronald Hutton}}</ref> | |||

| == Etymology == | == Etymology == | ||

| Line 42: | Line 42: | ||

| According to the ], ''wicce'' and ''wicca'' were probably derived from the Old English verb {{Lang|ang|wiccian}}, meaning 'to practice witchcraft'.<ref>{{Cite OED|witch}}</ref> ''Wiccian'' has a cognate in ] {{Lang|gml|wicken}} (attested from the 13th century). The further etymology of this word is problematic. It has no clear cognates in other ] outside of English and Low German, and there are numerous possibilities for the ] from which it may have derived. | According to the ], ''wicce'' and ''wicca'' were probably derived from the Old English verb {{Lang|ang|wiccian}}, meaning 'to practice witchcraft'.<ref>{{Cite OED|witch}}</ref> ''Wiccian'' has a cognate in ] {{Lang|gml|wicken}} (attested from the 13th century). The further etymology of this word is problematic. It has no clear cognates in other ] outside of English and Low German, and there are numerous possibilities for the ] from which it may have derived. | ||

| Another Old English word for 'witch' was {{Lang|ang|hægtes}} or {{Lang|ang|hægtesse}}, which became the modern English word "]" and is linked to the word "]". In most other Germanic languages, their word for 'witch' comes from the same root as these; for example ] |

Another Old English word for 'witch' was {{Lang|ang|hægtes}} or {{Lang|ang|hægtesse}}, which became the modern English word "]" and is linked to the word "]". In most other Germanic languages, their word for 'witch' comes from the same root as these; for example ] {{Lang|de|Hexe}} and ] {{Lang|nl|heks}}.<ref>{{cite web |title=hag (n.) |url=https://www.etymonline.com/word/hag |website=]}}</ref> | ||

| In colloquial modern ], the word ''witch'' is |

In colloquial modern ], the word ''witch'' is particularly used for women.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/witch|title=Definition of WITCH|website=www.merriam-webster.com|access-date=12 October 2023}}</ref> A male practitioner of magic or witchcraft is more commonly called a ']', or sometimes, 'warlock'. When the word ''witch'' is used to refer to a member of a neo-pagan tradition or religion (such as ]), it can refer to a person of any gender.{{cn|date=October 2023}} | ||

| == |

== Beliefs about practices == | ||

| ]. It shows a witch brewing a potion overlooked by her ] or a demon; items on the floor for casting a spell; and another witch reading from a ] while anointing the buttocks of a young witch about to fly upon an inverted ].]] | ]. It shows a witch brewing a potion overlooked by her ] or a demon; items on the floor for casting a spell; and another witch reading from a ] while anointing the buttocks of a young witch about to fly upon an inverted ].]] | ||

| Witches are commonly believed to cast ]s; a ] or set of magical words and gestures intended to inflict supernatural harm.{{sfnp|Levack|2013|p=54}} Cursing could also involve inscribing ] or ] on an object to give that object magical powers; burning or binding a wax or clay image (a ]) of a person to affect them magically; or using ]s, animal parts and other substances to make ]s or poisons.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Luck |first=Georg |title=Arcana Mundi: Magic and the Occult in the Greek and Roman Worlds; a Collection of Ancient Texts |date=1985 |publisher=] |isbn=978-0801825231 |location=Baltimore, Maryland |pages=254, 260, 394 |author-link=Georg Luck}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Kittredge |first=George Lyman |title=Witchcraft in Old and New England |date=1929 |publisher=Russell & Russell |isbn=978-0674182325 |location=New York |page=172}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Davies |first=Owen |url=https://archive.org/details/witchcraftmagicc00davi |title=Witchcraft, Magic and Culture, 1736–1951 |date=1999 |publisher=] |isbn=978-0719056567 |location=Manchester, England |url-access=registration}}</ref>{{sfnp|Hutton|2017|pp=19–22}} Witchcraft has been blamed for many kinds of misfortune. In Europe, by far the most common kind of harm attributed to witchcraft was illness or death suffered by adults, their children, or their animals. "Certain ailments, like impotence in men, infertility in women, and lack of milk in cows, were particularly associated with witchcraft". Illnesses that were poorly understood were more likely to be blamed on witchcraft. Edward Bever writes: "Witchcraft was particularly likely to be suspected when a disease came on unusually swiftly, lingered unusually long, could not be diagnosed clearly, or presented some other unusual symptoms".{{sfnp|Levack|2013|pp=54–55}} | |||

| Where belief in malicious magic practices exists, practitioners are typically forbidden by law as well as hated and feared by the general populace, while beneficial magic is tolerated or even accepted wholesale by the people—even if the orthodox establishment opposes it.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Hutton |first=Ronald |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=QqPbJQkSo8EC&q=alleged+practices+witchcraft&pg=PA203 |title=Witches, Druids and King Arthur |date=2006 |publisher=] |isbn=978-1852855550 |location=London|page=203 |language=en |access-date=2020-11-22 |archive-date=2021-07-18 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210718192634/https://books.google.com/books?id=QqPbJQkSo8EC&q=alleged+practices+witchcraft&pg=PA203 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| A common belief in cultures worldwide is that witches tend to use something from their target's body to work magic against them; for example hair, nail clippings, clothing, or bodily waste.{{sfnp|Hutton|2017|pp=19–22}} Such beliefs are found in Europe, Africa, South Asia, Polynesia, Melanesia, and North America.{{sfnp|Hutton|2017|pp=19–22}} Another widespread belief among Indigenous peoples in Africa and North America is that witches cause harm by introducing cursed magical objects into their victim's body; such as small bones or ashes.{{sfnp|Hutton|2017|pp=19–22}} ] described this kind of magic as ].{{efn|"If we analyze the principles of thought on which magic is based, they will probably be found to resolve themselves into two: first, that like produces like, or that an effect resembles its cause; and, second, that things which have once been in contact with each other continue to act on each other at a distance after the physical contact has been severed. The former principle may be called the Law of Similarity, the latter the Law of Contact or Contagion. From the first of these principles, namely the Law of Similarity, the magician infers that he can produce any effect he desires merely by imitating it: from the second he infers that whatever he does to a material object will affect equally the person with whom the object was once in contact, whether it formed part of his body or not."<ref>{{Cite book |last=Frazer |first=James |url=https://www.gutenberg.org/files/3623/3623-h/3623-h.htm#c3section1 |title=The Golden Bough |date=1922 |publisher=Bartleby}}</ref>}} | |||

| In some definitions, witches differ from sorceresses in that they do not need to use tools or actions to curse; their ] is believed to flow from some intangible inner quality, may be unaware of being a witch, or may have been convinced of their nature by the suggestion of others.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Cohn |first=Norman |url=https://archive.org/details/europesinnerdemo00cohn |title=Europe's Inner Demons |date=1975 |publisher=] |isbn=978-0465021314 |location=New York City |pages=–179 |author-link=Norman Cohn |url-access=registration}}</ref> This definition was pioneered in 1937 in a study of central African magical beliefs by ], who cautioned that it might not match English usage.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Evans-Pritchard |first=Edward Evan |url=https://archive.org/details/witchcraftoracle00evan/page/8 |title=Witchcraft, Oracles and Magic Among the Azande |date=1937 |publisher=] |isbn=978-0198740292 |location=Oxford |pages= |author-link=E. E. Evans-Pritchard}}</ref> Historians have found this definition difficult to apply to European witchcraft, where witches were believed to use physical techniques, as well as some who were believed to cause harm by thought alone.<ref name="Thomas">{{Cite book |last=Thomas |first=Keith |title=Religion and the Decline of Magic |date=1997 |publisher=] |isbn=978-0297002208 |location=Oxford |pages=464–465 |author-link=Keith Thomas (historian)}}; Ankarloo, Bengt and Henningsen, Gustav (1990) ''Early Modern European Witchcraft: Centres and Peripheries''. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 1, 14.</ref> | |||

| In some cultures, witches are believed to use human body parts in magic,{{sfnp|Hutton|2017|pp=19–22}} and they are commonly believed to ] for this purpose. In Europe, "cases in which women did undoubtedly kill their children, because of what today would be called ], were often interpreted as yielding to diabolical temptation".<ref>{{cite book |last1=Burns |first1=William |title=Witch Hunts in Europe and America: An Encyclopedia |date=2003 |publisher=Bloomsbury Publishing |pages=141–142}}</ref> | |||

| Probably the best-known characteristic of a witch is their ability to cast a ]—a set of words, a formula or verse, a ritual, or a combination of these, employed to do magic.<ref>{{Cite book |title=Oxford English Dictionary, the Compact Edition |date=1971 |publisher=] |location=Oxford, England |page=2955}}</ref> Spells traditionally were cast by many methods, such as by the inscription of ] or ] on an object to give that object magical powers; by the immolation or binding of a wax or clay image (]) of a person to affect them magically; by the recitation of ]s; by the performance of physical ]s; by the employment of magical ]s as amulets or ]s; by gazing at mirrors, swords or other specula (]) for purposes of divination; and by many other means.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Luck |first=Georg |title=Arcana Mundi: Magic and the Occult in the Greek and Roman Worlds; a Collection of Ancient Texts |date=1985 |publisher=] |isbn=978-0801825231 |location=Baltimore, Maryland |pages=254, 260, 394 |author-link=Georg Luck}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Kittredge |first=George Lyman |title=Witchcraft in Old and New England |date=1929 |publisher=Russell & Russell |isbn=978-0674182325 |location=New York City |page=172}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Davies |first=Owen |url=https://archive.org/details/witchcraftmagicc00davi |title=Witchcraft, Magic and Culture, 1736–1951 |date=1999 |publisher=] |isbn=978-0719056567 |location=Manchester, England |url-access=registration}}</ref> | |||

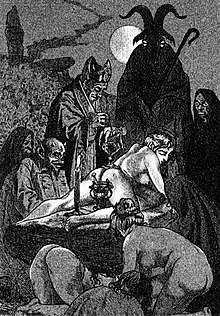

| Witches are believed to work in secret, sometimes alone and sometimes with other witches. Hutton writes: "Across most of the world, witches have been thought to gather at night, when normal humans are inactive, and also at their most vulnerable in sleep".{{sfnp|Hutton|2017|pp=19–22}} In most cultures, witches at these gatherings are thought to transgress social norms by engaging in cannibalism, incest and open nudity.{{sfnp|Hutton|2017|pp=19–22}} | |||

| Strictly speaking, ] is the practice of conjuring the spirits of the dead for ] or ], although the term has also been applied to raising the dead for other purposes. The biblical ] performed it (1 Samuel 28th chapter), and it is among the witchcraft practices condemned by ]:<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Semple |first=Sarah |date=December 2003 |title=Illustrations of damnation in late Anglo-Saxon manuscripts |url=http://dro.dur.ac.uk/3709/1/3709.pdf |journal=Anglo-Saxon England |volume=32 |pages=231–245 |doi=10.1017/S0263675103000115 |s2cid=161982897 |access-date=2018-10-26 |archive-date=2020-07-31 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200731181142/http://dro.dur.ac.uk/3709/1/3709.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Semple |first=Sarah |date=June 1998 |title=A fear of the past: The place of the prehistoric burial mound in the ideology of middle and later Anglo‐Saxon England |journal=World Archaeology |volume=30 |issue=1 |pages=109–126 |doi=10.1080/00438243.1998.9980400 |jstor=125012}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Pope |first=J.C. |title=Homilies of Aelfric: a supplementary collection (Early English Text Society 260) |date=1968 |publisher=] |volume=II |location=Oxford, England |page=796}}</ref> "Witches still go to cross-roads and to heathen burials with their delusive magic and call to the devil; and he comes to them in the likeness of the man that is buried there, as if he arises from death."<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Meaney |first=Audrey L. |date=December 1984 |title=Æfric and Idolatry |journal=Journal of Religious History |volume=13 |issue=2 |pages=119–135 |doi=10.1111/j.1467-9809.1984.tb00191.x}}</ref> | |||

| Witches around the world commonly have associations with animals.{{sfnp|Hutton|2017|pp=264–277}} ] identified this as a defining feature of the witch archetype.<ref>Rodney Needham, ''Primordial Characters'', Charlottesville, Va, 1978, 26, 42 {{ISBN?}}</ref> In some parts of the world, it is believed witches can ] into animals,{{sfnp|Hutton|2017|p=264}} or that the witch's spirit travels apart from their body and takes an animal form, an activity often associated with ].{{sfnp|Hutton|2017|p=264}} Another widespread belief is that witches have an animal helper.{{sfnp|Hutton|2017|p=264}} In English these are often called "]s", and meant an evil spirit or demon that had taken an animal form.{{sfnp|Hutton|2017|p=264}} As researchers examined traditions in other regions, they widened the term to servant spirit-animals which are described as a part of the witch's own soul.{{sfnp|Hutton|2017|p=269}} | |||

| == Witchcraft and cunning-craft == | |||

| ] is the practice of conjuring the spirits of the dead for ] or ], although the term has also been applied to raising the dead for other purposes. The biblical ] performed it (1 Samuel 28th chapter), and it is among the witchcraft practices condemned by ]:<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Semple |first=Sarah |date=December 2003 |title=Illustrations of damnation in late Anglo-Saxon manuscripts |url=http://dro.dur.ac.uk/3709/1/3709.pdf |journal=Anglo-Saxon England |volume=32 |pages=231–245 |doi=10.1017/S0263675103000115 |s2cid=161982897 |access-date=2018-10-26 |archive-date=2020-07-31 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200731181142/http://dro.dur.ac.uk/3709/1/3709.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Semple |first=Sarah |date=June 1998 |title=A fear of the past: The place of the prehistoric burial mound in the ideology of middle and later Anglo-Saxon England |journal=World Archaeology |volume=30 |issue=1 |pages=109–126 |doi=10.1080/00438243.1998.9980400 |jstor=125012}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Pope |first=J.C. |title=Homilies of Aelfric: a supplementary collection (Early English Text Society 260) |date=1968 |publisher=] |volume=II |location=Oxford, England |page=796}}</ref> "Witches still go to cross-roads and to heathen burials with their delusive magic and call to the ]; and he comes to them in the likeness of the man that is buried there, as if he arises from death."<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Meaney |first=Audrey L. |date=December 1984 |title=Æfric and Idolatry |journal=Journal of Religious History |volume=13 |issue=2 |pages=119–135 |doi=10.1111/j.1467-9809.1984.tb00191.x}}</ref> | |||

| == Witchcraft and folk healers == | |||

| {{Main|Cunning folk}} | {{Main|Cunning folk}} | ||

| ] of a cunning woman or wise woman in the Museum of Witchcraft and Magic]] | |||

| Most societies that have believed in harmful or ] have also believed in helpful or ].{{sfnp|Hutton|2017|pp=24–25}} Where belief in harmful magic is common, it is typically forbidden by law as well as hated and feared by the general populace, while helpful or ] magic is tolerated or accepted by the population, even if the orthodox establishment opposes it.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Hutton |first=Ronald |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=QqPbJQkSo8EC&q=alleged+practices+witchcraft&pg=PA203 |title=Witches, Druids and King Arthur |date=2006 |publisher=] |isbn=978-1852855550 |location=London|language=en |access-date=2020-11-22 |archive-date=2021-07-18 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210718192634/https://books.google.com/books?id=QqPbJQkSo8EC&q=alleged+practices+witchcraft&pg=PA203 |url-status=live|page=203 }}</ref> | |||

| In these societies, practitioners of helpful magic provide (or provided) services such as breaking the effects of witchcraft, ], ], finding lost or stolen goods, and ].{{sfnp|Hutton|2017|pp=x-xi}} In Britain, and some other parts of Europe, they were commonly known as 'cunning folk' or 'wise people'.{{sfnp|Hutton|2017|pp=x–xi}} ] wrote that while cunning folk is the usual name, some are also known as 'blessers' or 'wizards', but might also be known as 'white', 'good', or 'unbinding witches'.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Macfarlane |first=Alan |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=lmfuwq0mQMUC&pg=PA130 |title=Witchcraft in Tudor and Stuart England: A Regional and Comparative Study |year= 1999 |publisher=Psychology Press |page=130 |isbn=978-0415196123 }}</ref> Historian ] says the term "white witch" was rarely used before the 20th century.{{sfnp|Davies|2003|p=xiii}} Ronald Hutton uses the general term "service magicians".{{sfnp|Hutton|2017|pp=x-xi}} Often these people were involved in identifying alleged witches.{{sfnp|Hutton|2017|pp=24–25}} | |||

| ] in ], condemning witchcraft and traditional ]]] | |||

| Such helpful magic-workers "were normally contrasted with the witch who practiced ''maleficium''—that is, magic used for harmful ends".{{sfnp|Willis|2018|pp=27-28}} In the early years of the ] "the cunning folk were widely tolerated by church, state and general populace".{{sfnp|Willis|2018|pp=27–28}} Some of the more hostile churchmen and secular authorities tried to smear folk-healers and magic-workers by falsely branding them 'witches' and associating them with harmful 'witchcraft',{{sfnp|Hutton|2017|pp=x–xi}} but generally the masses did not accept this and continued to make use of their services.<ref>{{cite book |first1=Ole Peter |last1=Grell |first2=Robert W. |last2=Scribner |year=2002 |title=Tolerance and Intolerance in the European Reformation |publisher=Cambridge University Press |page=45 |quote=Not all the stereotypes created by elites were capable of popular reception The most interesting example concerns cunning folk, whom secular and religious authorities consistently sought to associate with negative stereotypes of superstition or witchcraft. This proved no deterrent to their activities or to the positive evaluation in the popular mind of what they had to offer.}}</ref> The English ] and skeptic ] sought to disprove magic and witchcraft altogether, writing in '']'' (1584), "At this day, it is indifferent to say in the English tongue, 'she is a witch' or 'she is a wise woman'".<ref>{{Cite book |last=Scot |first=Reginald |title=The Discoverie of Witchcraft |date=1584 |volume=Booke V |chapter=Chapter 9 |author-link=Reginald Scot}}</ref> Historian ] adds "Nevertheless, it is possible to isolate that kind of 'witchcraft' which involved the employment (or presumed employment) of some occult means of doing harm to other people in a way which was generally disapproved of. In this sense the belief in witchcraft can be defined as the attribution of misfortune to occult human agency".{{sfnp|Thomas|1997|p=519}} | |||

| Traditionally, the terms "witch" and "witchcraft" had negative connotations. Most societies that have believed in harmful witchcraft or ] have also believed in helpful or ']' magic.<ref name="Hutton witch-thwarting">{{Cite book |last=Hutton |first=Ronald |title=The Witch: A History of Fear, from Ancient Times to the Present |date=2017 |publisher=] |pages=24–25 |author-link=Ronald Hutton}}</ref> In these societies, practitioners of helpful magic provided services such as breaking the effects of witchcraft, ], ], finding lost or stolen goods, and ].<ref name="Hutton service magicians">{{Cite book |last=Hutton |first=Ronald |title=The Witch: A History of Fear, from Ancient Times to the Present |date=2017 |publisher=] |pages=x–xi |author-link=Ronald Hutton}}</ref> In Britain they were commonly known as ] or wise people.<ref name="Hutton service magicians"/> Alan McFarlane writes, "There were a number of interchangeable terms for these practitioners, 'white', 'good', or 'unbinding' witches, blessers, wizards, sorcerers, however 'cunning-man' and 'wise-man' were the most frequent".<ref>{{Cite book |last=Macfarlane |first=Alan |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=lmfuwq0mQMUC&pg=PA130 |title=Witchcraft in Tudor and Stuart England: A Regional and Comparative Study |year= 1999 |publisher=Psychology Press |isbn=978-0415196123 |access-date=31 October 2017 |via=Google Books |archive-date=26 January 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210126013247/https://books.google.com/books?id=lmfuwq0mQMUC&pg=PA130 |url-status=live }}</ref> Ronald Hutton prefers the term "service magicians".<ref name="Hutton service magicians"/> Often these people were involved in identifying alleged witches.<ref name="Hutton witch-thwarting"/> | |||

| ] says folk magicians in Europe were viewed ambivalently by communities, and were considered as capable of harming as of healing,{{sfnp|Wilby|2005|pp=51–54}} which could lead to their being accused as malevolent witches. She suggests some English "witches" convicted of consorting with demons may have been cunning folk whose supposed ] ]s had been ].{{sfnp|Wilby|2005|p=123}} | |||

| Hostile churchmen sometimes branded any magic-workers "witches" as a way of smearing them.<ref name="Hutton service magicians"/> Englishman ], who sought to disprove witchcraft and magic, wrote in '']'' (1584), "At this day it is indifferent to say in the English tongue, 'she is a witch' or 'she is a wise woman{{'"}}.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Scot |first=Reginald |title=The Discoverie of Witchcraft |date=1584 |volume=Booke V |chapter=Chapter 9 |author-link=Reginald Scot}}</ref> Folk magicians throughout Europe were often viewed ambivalently by communities, and were considered as capable of harming as of healing,<ref name="Wilby">Wilby, Emma (2006) '']''. pp. 51–54.</ref> which could lead to their being accused as "witches" in the negative sense. Many English "witches" convicted of consorting with demons may have been cunning folk whose supposed ] ]s had been demonised;<ref>Emma Wilby 2005 p. 123; See also {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160808111045/https://books.google.com/books?id=lmfuwq0mQMUC&lpg=PP1&pg=PA127#v=onepage&q=white%20witches%20black%20witches&f=false |date=2016-08-08 }}</ref> many French {{Lang|fr|devins-guerisseurs}} ("diviner-healers") were accused of witchcraft,<ref>Monter, ''Witchcraft in France and Switzerland''. Ch. 7: "White versus Black Witchcraft".</ref> over half the accused witches in Hungary seem to have been healers,<ref>Pócs 1999, p. 12.</ref> and the "vast majority" of Finland's accused witches were folk healers.<ref name="Stokker">{{cite book |last1=Stokker |first1=Kathleen |title=Remedies and Rituals: Folk Medicine in Norway and the New Land |date=2007 |publisher=Minnesota Historical Society Press |location=St. Paul, MN |isbn=978-0873517508 |pages=81–82 |quote=Supernatural healing of the sort practiced by Inger Roed and Lisbet Nypan, known as ''signeri'', played a role in the vast majority of Norway's 263 documented witch trials. In trial after trial, accused 'witches' came forward and freely testified about their healing methods, telling about the salves they made and the ''bønner'' (prayers) they read over them to enhance their potency.}}</ref> Hutton, however, says that "Service magicians were sometimes denounced as witches, but seem to have made up a minority of the accused in any area studied".<ref name="Hutton witch-thwarting"/> | |||

| ] says that magical healers "were sometimes denounced as witches, but seem to have made up a minority of the accused in any area studied".{{sfnp|Hutton|2017|pp=24–25}} Likewise, ] says "relatively few cunning-folk were prosecuted under secular statutes for witchcraft" and were dealt with more leniently than alleged witches. The ] (1532) of the ], and the Danish Witchcraft Act of 1617, stated that workers of folk magic should be dealt with differently from witches.{{sfnp|Davies|2003|p=164}} It was suggested by ] that 'diviner-healers' ({{Lang|fr|devins-guerisseurs}}) made up a significant proportion of those tried for witchcraft in France and Switzerland, but more recent surveys conclude that they made up less than 2% of the accused.{{sfnp|Davies|2003|p=167}} However, ] says that half the accused witches in Hungary seem to have been healers,{{sfnp|Pócs|1999|p=12}} and Kathleen Stokker says the "vast majority" of Norway's accused witches were folk healers.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Stokker |first1=Kathleen |title=Remedies and Rituals: Folk Medicine in Norway and the New Land |date=2007 |publisher=Minnesota Historical Society Press |location=St. Paul, MN |isbn=978-0873517508 |pages=81–82 |quote=Supernatural healing of the sort practiced by Inger Roed and Lisbet Nypan, known as ''signeri'', played a role in the vast majority of Norway's 263 documented witch trials. In trial after trial, accused 'witches' came forward and freely testified about their healing methods, telling about the salves they made and the ''bønner'' (prayers) they read over them to enhance their potency.}}</ref> | |||

| ==Thwarting witchcraft== | |||

| ==Witch-hunts and thwarting witchcraft== | |||

| {{globalize|section|date=August 2023}} | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| Societies that believed in witchcraft also |

Societies that believe (or believed) in witchcraft may also believe that it can be thwarted in various ways. One common way is to use ], often with the help of magical healers such as ] or ]s.{{sfnp|Hutton|2017|pp=24–25}} This includes performing ]s, reciting ], or the use of ]s, ]s, anti-], ]s, ]s, and burying objects such as ] inside the walls of buildings.<ref>Hoggard, Brian (2004). "The archaeology of counter-witchcraft and popular magic", in ''Beyond the Witch Trials: Witchcraft and Magic in Enlightenment Europe'', Manchester University Press. p. 167{{ISBN?}}</ref> Another believed cure for bewitchment is to persuade or force the alleged witch to lift their spell.{{sfnp|Hutton|2017|pp=24–25}} Often, people have attempted to thwart the witchcraft by physically punishing the alleged witch, such as by banishing, wounding, torturing or killing them. Hutton wrote that "In most societies, however, a formal and legal remedy was preferred to this sort of private action", whereby the alleged witch would be prosecuted and then formally punished if found guilty.{{sfnp|Hutton|2017|pp=24–25}} | ||

| === Accusations of witchcraft === | === Accusations of witchcraft === | ||

| ]]] | ] | ||

| Throughout the world, accusations of witchcraft are often linked to social and economic tensions. Females are most often accused, but in some cultures it is mostly males, such as in Iceland.<ref>{{Citation|title=Witchcraft in 17th century Iceland|url=https://www.penguin.co.uk/articles/2019/02/witchcraft-in-17th-century-iceland-caroline-lea}}</ref> In many societies, accusations are directed mainly against the elderly, but in others age is not a factor, and in some cultures it is mainly adolescents who are accused.{{sfnp|Hutton|2017|p=15}} | |||

| ] writes that reasons for accusations of witchcraft fall into four general categories:<ref name="Pocs" /> | |||

| # A person was caught in the act of positive or negative ] | |||

| ] writes that reasons for accusations of witchcraft fall into four general categories. The first three of which were proposed by ], and the fourth added by ]:{{sfnp|Pócs|1999|pp=9–10}} | |||

| # A person was caught in the act of positive or negative ] | |||

| # A well-meaning sorcerer or healer lost their clients' or the authorities' trust | # A well-meaning sorcerer or healer lost their clients' or the authorities' trust | ||

| # A person did nothing more than gain the enmity of their neighbors | # A person did nothing more than gain the enmity of their neighbors | ||

| # A person was reputed to be a witch and surrounded with an aura of witch-beliefs or ] | # A person was reputed to be a witch and surrounded with an aura of witch-beliefs or ]. | ||

| She identifies three kinds of witch in popular belief:<ref name="Pocs" /> | |||

| * The "neighborhood witch" or "social witch": a witch who curses a neighbor following some dispute. | |||

| * The "magical" or "sorcerer" witch: either a professional healer, sorcerer, seer or midwife, or a person who has through magic increased her fortune to the perceived detriment of a neighboring household; due to neighborhood or community rivalries, and the ambiguity between positive and negative magic, such individuals can become branded as witches. | |||

| * The "supernatural" or "night" witch: portrayed in court narratives as a demon appearing in visions and dreams.<ref>Pócs 1999 pp. 10–11.</ref> | |||

| "Neighborhood witches" are the product of neighborhood tensions, and are found only in village communities where the inhabitants largely rely on each other. Such accusations follow the breaking of some social norm, such as the failure to return a borrowed item, and any person part of the normal social exchange could potentially fall under suspicion. Claims of "sorcerer" witches and "supernatural" witches could arise out of social tensions, but not exclusively; the supernatural witch often had nothing to do with communal conflict, but expressed tensions between the human and supernatural worlds; and in Eastern and Southeastern Europe such supernatural witches became an ideology explaining calamities that befell whole communities.<ref>Pócs 1999 pp. 11–12.</ref> | |||

| The historian ] has written: | |||

| {{blockquote|he medical arts played a significant and sometimes pivotal role in the witchcraft controversies of seventeenth-century New England. Not only were physicians and surgeons the principal professional arbiters for determining natural versus preternatural signs and symptoms of disease, they occupied key legislative, judicial, and ministerial roles relating to witchcraft proceedings. Forty six male physicians, surgeons, and apothecaries are named in court transcripts or other contemporary source materials relating to New England witchcraft. These practitioners served on coroners' inquests, performed autopsies, took testimony, issued writs, wrote letters, or committed people to prison, in addition to diagnosing and treating patients.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Gevitz |first=N. |date=1 January 2000 |title='The Devil Hath Laughed at the Physicians': Witchcraft and Medical Practice in Seventeenth-Century New England |journal=Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences |volume=55 |issue=1 |pages=5–36 |doi=10.1093/jhmas/55.1.5 |pmid=10734719}}</ref>}} | |||

| ===European witch-hunts and witch-trials=== | |||

| {{main|Witch-hunt|Witch trials in the early modern period}} | |||

| ] | |||

| In ], sorcery came to be associated with ] and ] and to be viewed as evil. Among the ], Protestants, and ] leadership of the ]an Late ]/] period, fears about witchcraft rose to fever pitch and sometimes led to large-scale ]s. The key century was the fifteenth, which saw a dramatic rise in awareness and terror of witchcraft, culminating in the publication of the {{Lang|la|Malleus Maleficarum}} but prepared by such fanatical popular preachers as Bernardino of Siena.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Mormando |first=Franco |title=The Preacher's Demons: Bernardino of Siena and the Social Underworld of Early Renaissance Italy |date=1999 |publisher=] |isbn=0226538540 |location=Chicago, Illinois |pages=52–108}}</ref> In total, tens or hundreds of thousands of people were executed, and others were imprisoned, tortured, banished, and had lands and possessions confiscated. The majority of those accused were women, though in some regions the majority were men.<ref name="gibbons" /><ref>{{Cite book |last=Barstow |first=Anne Llewellyn |url=https://archive.org/details/witchcrazenewhis0000bars |title=Witchcraze: A New History of the European Witch Hunts |date=1994 |publisher=Pandora |isbn=978-0062500496 |location=San Francisco |page= |url-access=registration}}</ref> In early modern ], the word ] came to be used as the male equivalent of ] (which can be male or female, but is used predominantly for females).<ref>{{Cite book |last=McNeill |first=F. Marian |title=The Silver Bough: A Four Volume Study of the National and Local Festivals of Scotland |date=1957 |publisher=] |isbn=978-0862412319 |volume=1 |location=Edinburgh}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Chambers |first=Robert |title=Domestic Annals of Scotland |date=1861 |isbn=978-1298711960 |location=Edinburgh, Scotland}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Sinclair |first=George |title=Satan's Invisible World Discovered |date=1871 |location=Edinburgh}}</ref> | |||

| The ''],'' (Latin for 'Hammer of The Witches') was a witch-hunting manual written in 1486 by two German monks, Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Sprenger. It was used by both Catholics and Protestants<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=H0IAjBexFTgC&q=malleus%20maleficarum%20protestant&pg=PA27 |title=The Emergence of Modern Europe: c. 1500 to 1788 |date=2011 |publisher=] |isbn=978-1615303434 |editor-last=Campbell |editor-first=Heather M. |page=27 |access-date=June 29, 2013 |archive-date=January 26, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210126013251/https://books.google.com/books?id=H0IAjBexFTgC&q=malleus%20maleficarum%20protestant&pg=PA27 |url-status=live }}</ref> for several hundred years, outlining how to identify a witch, what makes a woman more likely than a man to be a witch, how to put a witch on trial, and how to punish a witch. The book defines a witch as evil and typically female. The book became the handbook for secular courts throughout ] Europe, but was not used by the Inquisition, which even cautioned against relying on The Work.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Jolly |first1=Karen |title=Witchcraft and Magic in Europe: The Middle Ages |last2=Raudvere |first2=Catharina |last3=Peters |first3=Edward |date=2002 |publisher=] |isbn=978-0485890037 |location=New York City |page=241 |quote=In 1538 the Spanish Inquisition cautioned its members not to believe everything the Malleus said, even when it presented apparently firm evidence.}}</ref> It is likely that this caused witch mania to become so widespread. It was the most sold book in Europe for over 100 years, after the Bible.<ref>{{Cite web |title=History of Witches|url=https://www.history.com/topics/folklore/history-of-witches|access-date=2021-10-26|website=History.com|date=20 October 2020 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| European witch-trials reached their peak in the early 17th century, after which popular sentiment began to turn against the practice. ]'s book '']'', published in 1631, argued that witch-trials were largely unreliable and immoral.<ref name="Reilly1956">{{cite journal |last1=Reilly |first1=Pamela |title=Some Notes on Friedrich von Spee's 'Cautio Criminalis' |journal=The Modern Language Review |date=October 1956 |volume=51 |issue=4 |pages=536–542 |doi=10.2307/3719223|jstor=3719223 }}</ref> In 1682, King ] prohibited further witch-trials in France. In 1736, ] formally ended witch-trials with passage of the ].<ref name="Bath2008">{{cite book |editor1-last=Bath |editor1-first=Jo |editor2-last=Newton |editor2-first=John |title=Witchcraft and the Act of 1604 |date=2008 |publisher=Brill |location=Leiden |isbn=978-9004165281 |pages=243–244}}</ref> | |||

| ===Modern witch-hunts=== | ===Modern witch-hunts=== | ||

| {{main|Modern witch-hunts}} | {{main|Witch-hunt|Witch trials in the early modern period|Modern witch-hunts}} | ||

| Belief in witchcraft continues to be present today in some societies and accusations of witchcraft are the trigger for serious forms of ], including ]. Such incidents are common in countries such as ], ], ], ], ], ] and ]. Accusations of witchcraft are sometimes linked to personal disputes, ], and conflicts between neighbors or family members over land or inheritance. Witchcraft-related violence is often discussed as a serious issue in the broader context of ].<ref>{{Cite web |date=2013 |title=A Global Issue that Demands Action |url=http://www.genevadeclaration.org/fileadmin/docs/Co-publications/Femicide_A%20Gobal%20Issue%20that%20demands%20Action.pdf |access-date=2014-06-07 |publisher=the Academic Council on the United Nations System (ACUNS) Vienna Liaison Office |archive-date=2014-06-30 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140630215522/http://www.genevadeclaration.org/fileadmin/docs/Co-publications/Femicide_A%20Gobal%20Issue%20that%20demands%20Action.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Diwan |first=Mohammed |date=1 July 2004 |title=Conflict between State Legal Norms and Norms Underlying Popular Beliefs: Witchcraft in Africa as a Case Study |url=https://scholarship.law.duke.edu/djcil/vol14/iss2/5/ |journal=Duke Journal of Comparative & International Law |volume=14 |issue=2 |pages=351–388 |access-date=28 March 2021 |archive-date=25 February 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210225231102/https://scholarship.law.duke.edu/djcil/vol14/iss2/5/ |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |date= 2009 |title=Witch Hunts in Modern South Africa: An Under-represented Facet of Gender-based Violence |url=http://www.mrc.ac.za/crime/witchhunts.pdf |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120425074549/http://www.mrc.ac.za/crime/witchhunts.pdf |archive-date=2012-04-25 |access-date=2014-06-07 |publisher=MRC-UNISA Crime, Violence and Injury Lead Programm |citeseerx=10.1.1.694.6630}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Nepal: Witchcraft as a Superstition and a form of violence against women in Nepal |url=http://www.humanrights.asia/opinions/columns/AHRC-ETC-056-2011 |access-date=2014-06-07 |website=Humanrights.asia |publisher=Asian Human Rights Commission |archive-date=2014-06-25 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140625033851/http://www.humanrights.asia/opinions/columns/AHRC-ETC-056-2011 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Adinkrah |first=Mensah |date=April 2004 |title=Witchcraft Accusations and Female Homicide Victimization in Contemporary Ghana |journal=Violence Against Women |volume=10 |issue=4 |pages=325–356 |doi=10.1177/1077801204263419 |s2cid=146650565}}</ref> In Tanzania, about 500 old women are murdered each year following accusations of witchcraft or accusations of being a witch.<ref>{{Cite web |title=World Report on Violence and Health |url=https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/global_campaign/en/chap5.pdf |access-date=2014-06-07 |publisher=] |archive-date=2014-01-24 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140124045330/http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/global_campaign/en/chap5.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> Apart from ], state-sanctioned violence also occurs in some jurisdictions. For instance, in ] practicing witchcraft and sorcery is a crime ] and the country has executed people for this crime in 2011, 2012 and 2014.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Saudi woman beheaded for 'witchcraft and sorcery' |date=13 December 2011 |url=http://edition.cnn.com/2011/12/13/world/meast/saudi-arabia-beheading/ |access-date=2014-06-07 |publisher=Edition.cnn.com |archive-date=2020-05-21 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200521231628/https://edition.cnn.com/2011/12/13/world/meast/saudi-arabia-beheading/ |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |date=2012-06-19 |title= Saudi man executed for 'witchcraft and sorcery' |work=BBC News |publisher=Bbc.com |url=https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-18503550 |access-date=2014-06-07 |archive-date=2019-05-30 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190530091343/https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-18503550 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="di Giovanni">{{Cite news |last=di Giovanni |first=Janine |date=14 October 2014 |title=When It Comes to Beheadings, ISIS Has Nothing Over Saudi Arabia |work=Newsweek |url=http://www.newsweek.com/2014/10/24/when-it-comes-beheadings-isis-has-nothing-over-saudi-arabia-277385.html |access-date=17 October 2014 |archive-date=16 October 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141016223514/http://www.newsweek.com/2014/10/24/when-it-comes-beheadings-isis-has-nothing-over-saudi-arabia-277385.html |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Children who live in some regions of the world, such as parts of Africa, are also vulnerable to violence that is related to witchcraft accusations.<ref>Bussien, Nathaly et al. 2011. Breaking the spell: Responding to witchcraft accusations against children, in New Issues in refugee Research (197). Geneva, Switzerland: UNHCR</ref><ref>Cimpric, Aleksandra 2010. Children accused of witchcraft, An anthropological study of contemporary practices in Africa. Dakar, Senegal: UNICEF WCARO</ref><ref>Molina, Javier Aguilar 2006. "The Invention of Child Witches in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Social cleansing, religious commerce and the difficulties of being a parent in an urban culture". London: Save the Children</ref><ref>Human Rights Watch 2006. Children in the DRC. Human Rights Watch report, 18 (2)</ref> Such incidents have also occurred in immigrant communities in the UK, including the much publicized case of the ].<ref>{{Cite news |date=2012-03-05 |title=Witchcraft murder: Couple jailed for Kristy Bamu killing |work=BBC News |publisher=Bbc.co.uk |url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-london-17255470 |access-date=2014-06-08 |archive-date=2014-04-08 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140408060045/http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-london-17255470 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |last=Dangerfield |first=Andy |date=2012-03-01 |title=Government urged to tackle 'witchcraft belief' child abuse |work=BBC News |publisher=Bbc.co.uk |url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-london-17006924 |access-date=2014-06-08 |archive-date=2014-10-08 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141008203907/http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-london-17006924 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Witch-hunts, scapegoating, and the ] or ] of suspected witches still occurs.<ref>{{Cite news |last=Pearlman |first=Jonathan |date=11 April 2013 |title=Papua New Guinea urged to halt witchcraft violence after latest 'sorcery' case |work=] |publisher=] |location=London, England |url=https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/australiaandthepacific/papuanewguinea/9987294/Papua-New-Guinea-urged-to-halt-witchcraft-violence-after-latest-sorcery-case.html |access-date=5 April 2018 |archive-date=11 February 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180211174243/http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/australiaandthepacific/papuanewguinea/9987294/Papua-New-Guinea-urged-to-halt-witchcraft-violence-after-latest-sorcery-case.html |url-status=live }}</ref> Many cultures worldwide continue to have a belief in the concept of "witchcraft" or malevolent magic.{{sfnp|Ankarloo|Clark|2001|p={{pn|date=May 2024}}}} | |||

| == Wicca == | |||

| {{Main|Wicca}} | |||

| From the 1920s, ] popularized the ']': the idea that those ] were followers of a benevolent ] religion that had survived the ] of Europe. This has been proven untrue by further historical research.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Hutton |first=Ronald |title=The Witch: A History of Fear, from Ancient Times to the Present |date=2017 |publisher=] |page=121 |author-link=Ronald Hutton}}</ref><ref>Rose, Elliot, ''A Razor for a Goat'', ], 1962. Hutton, Ronald, ''The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles'', ]: ], 1993. Hutton, Ronald, ''The Triumph of the Moon: A History of Modern Pagan Witchcraft'', ], 1999.{{ISBN?}}</ref> | |||

| Apart from ], state-sanctioned execution also occurs in some jurisdictions. For instance, in ] practicing witchcraft and sorcery is a crime ] and the country has executed people for this crime as recently as 2014.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Saudi woman beheaded for 'witchcraft and sorcery' |date=13 December 2011 |url=http://edition.cnn.com/2011/12/13/world/meast/saudi-arabia-beheading/ |access-date=2014-06-07 |publisher=Edition.cnn.com |archive-date=2020-05-21 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200521231628/https://edition.cnn.com/2011/12/13/world/meast/saudi-arabia-beheading/ |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |date=2012-06-19 |title= Saudi man executed for 'witchcraft and sorcery' |work=BBC News |publisher=Bbc.com |url=https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-18503550 |access-date=2014-06-07 |archive-date=2019-05-30 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190530091343/https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-18503550 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |last=di Giovanni |first=Janine |date=14 October 2014 |title=When It Comes to Beheadings, ISIS Has Nothing Over Saudi Arabia |work=Newsweek |url=http://www.newsweek.com/2014/10/24/when-it-comes-beheadings-isis-has-nothing-over-saudi-arabia-277385.html |access-date=17 October 2014 |archive-date=16 October 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141016223514/http://www.newsweek.com/2014/10/24/when-it-comes-beheadings-isis-has-nothing-over-saudi-arabia-277385.html |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||