| Revision as of 03:56, 21 October 2023 editHTGS (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users12,620 edits Simple copy edits, mostly capital letters, in line with MOS:INSTITUTIONSTag: Visual edit← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 17:10, 5 January 2025 edit undoMoxy (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Page movers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers, Template editors129,893 edits →Disability | ||

| (322 intermediate revisions by 20 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|none}} | {{Short description|none}} | ||

| {{Canadian |

{{Use Canadian English|date=November 2024}} | ||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=November 2024}} | |||

| '''Human rights in Canada''' have come under increasing public attention and legal protection since ]. Prior to that time, there were few legal protections for ]. The protections which did exist focused on specific issues, rather than taking a general approach to human rights. | |||

| {{if mobile|] often simply referred to as the ''Charter'' in Canada, is a ] ] in the ]]]|{{Canadian human rights sidebar}}}} | |||

| The current legal framework for the protection of human rights in Canada consists of constitutional entitlements, and statutory human rights codes, both federal and provincial. The constitutional foundation of the modern Canadian human rights system is the ], which is part of the Constitution of Canada. Before 1982, there was little direct constitutional protection against government interference with human rights, although provincial and federal laws did provide some protection for human rights enforceable against government and private parties. Today, the charter guarantees fundamental freedoms (free expression, religion, association and peaceful assembly), democratic rights (such as participation in elections), mobility rights, legal rights, equality rights, and language rights. | |||

| '''Human rights in Canada''' have come under increasing public attention and legal protection since ]. Inspired by Canada's involvement in the creation of the ] in 1948,<ref>{{cite journal |title=Canada and the Adoption of Universal Declaration of Human Rights |last=Schabas |first=William |journal=McGill Law Journal |page=403 |volume=43 |year=1998 |url =https://lawjournal.mcgill.ca/wp-content/uploads/pdf/5890478-43.Schabas.pdf}}</ref> the current legal framework for ] in Canada consists of ], and statutory human rights codes, both ] and ]. | |||

| ] first recognized an ] in 1938 in the decision ].<ref name=magnet>Joseph E. Magnet, {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071008084158/http://www.constitutional-law.net/chartersample.html |date=October 8, 2007 }}, Juriliber, Edmonton (2001). URL accessed on March 18, 2006.</ref> However, prior to the advent of the '']'' in 1960 and its successor the '']'' in 1982 (part of the ]), the laws of Canada did not provide much in the way of ] and was typically of limited concern to the courts.<ref name="ChurchSchulze2007">{{cite book|first1=Joan|last1=Church|first2=Christian|last2=Schulze|first3=Hennie|last3=Strydom|title=Human rights from a comparative and international law perspective|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=2sMwFTOrixwC&pg=PA82|year= 2007|publisher=Unisa Press|isbn=978-1-86888-361-5|page=82}}</ref> The protections which did exist focused on specific issues, rather than taking a general approach to human rights with some provincial and federal laws offering limited safeguards. | |||

| Controversial human rights issues in Canada have included ], ], ], ], parents' rights, ], ] vs ], ], majority rights, ], ], ] and economic, social and political rights.<ref> {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081203171021/http://www.pch.gc.ca/progs/pdp-hrp/canada/themes_e.cfm |date=December 3, 2008 }}</ref> | |||

| Since the 1960s, Canada has placed emphasis on equality and inclusiveness for all people.<ref name="MacLennan2004sad">{{cite book|author=Christopher MacLennan|title=Toward the Charter: Canadians and the Demand for a National Bill of Rights, 1929–1960|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=xxt6VAsdW5oC&pg=PA119|year=2004|publisher=McGill-Queen's Press – MQUP|isbn=978-0-7735-2536-8|page=119}}</ref><ref name="Bumsted2003">{{cite book|author=J. M. Bumsted|title=Canada's Diverse Peoples: A Reference Sourcebook|url=https://archive.org/details/canadasdiversepe0000bums|url-access=registration|date= 2003|publisher=ABC-CLIO|isbn=978-1-57607-672-9|page=}}</ref> In present-day Canada the idea of a "]" are constitutionally protected.<ref name="x717">{{cite book | last=LaSelva | first=S.V. | title=The Moral Foundations of Canadian Federalism: Paradoxes, Achievements, and Tragedies of Nationhood | publisher=McGill-Queen's University Press | year=1996 | isbn=978-0-7735-1422-5 | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=rcqMl9MK_x0C&pg=PA86 | access-date=November 2, 2024 | page=86}}</ref> The "Canadian Charter" guarantees fundamental freedoms such as; ] and ].<ref name="v420a"/> Other rights related to ], ], ], ], ] and ] are also within the Charter.<ref name="v420a">{{cite web | title=The rights and freedoms the Charter protects | website=Ministère de la Justice | date=Apr 12, 2018 | url=https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/csj-sjc/rfc-dlc/ccrf-ccdl/rfcp-cdlp.html | access-date=Nov 3, 2024}}</ref> | |||

| == History == | |||

| {{further|Slavery in Canada}} | |||

| Internationally, Canada is a signatory to multiple human rights treaties,<ref name="o751">{{cite web | title=International Human Rights Treaties to which Canada is a Party | website=Ministère de la Justice | date=November 14, 2016 | url=https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/abt-apd/icg-gci/ihrl-didp/tcp.html | access-date=2024-10-29}}</ref> and ] of ].<ref name="z574">{{cite web | title=Canada: Freedom in the World 2023 Country Report | website=Freedom House | url=https://freedomhouse.org/country/canada/freedom-world/2023 | access-date=November 3, 2024}}</ref><ref name="s701">{{cite web | last=Amanat | first=Hayatullah | title=Canada ranks as 2nd-best country in 2023: U.S. News | website=CTVNews | date=Sep 8, 2023 | url=https://www.ctvnews.ca/world/canada-ranks-as-second-best-country-in-the-world-in-2023-u-s-news-1.6554229 | access-date=November 3, 2024}}</ref> Despite Canada being an international leader of human rights there are foreign and varied domestic concerns.<ref name="x688">{{cite web | title=World Report 2020: Rights Trends in Canada | website=Human Rights Watch | date=December 13, 2019 | url=https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2020/country-chapters/canada | access-date=October 28, 2024}}</ref><ref name="c127">{{cite web | title=Canada "a welcome ally" in advancing human rights around the world – Bachelet | website=OHCHR | date=June 19, 2019 | url=https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2019/06/canada-welcome-ally-advancing-human-rights-around-world-bachelet | access-date=October 28, 2024}}</ref> There are significant issue of historic ] - including the modern day plight of ], reports of ] and ], concern with the ] and the ]. | |||

| === Colonial period === | |||

| == Current legal framework == | |||

| The first legal protection for human rights in Canada related to religious freedom. The ''Articles of Capitulation'' of the town of Quebec, negotiated between the French and British military commanders after the fall of Quebec in 1759, provided a guarantee of "the free exercise of the Roman religion" until the possession of Canada was determined by the British and French governments.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.42695/6?r=0&s=1|title=A collection of the acts passed in the Parliame... - Canadiana Online|website=www.canadiana.ca}}</ref> A similar guarantee was included in the ''Articles of Capitulation'' of Montreal the next year.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.42695/10?r=0&s=1|title=A collection of the acts passed in the Parliame... - Canadiana Online|website=www.canadiana.ca}}</ref> The two guarantees were formally confirmed by Britain in the '']'',<ref>.</ref> and then given statutory protection in the '']''.<ref name = QuebecAct>{{Cite web|url=https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/quebec_act_1774.asp|title=Avalon Project - Great Britain : Parliament - The Quebec Act: October 7, 1774|website=avalon.law.yale.edu}}</ref> The result was that the British subjects in Quebec had greater guarantees of religious liberty at that time than did the Roman Catholic inhabitants of Great Britain and Ireland, who would not receive similar guarantees until ] in 1829.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://members.pcug.org.au/~ppmay/acts/relief_act_1829.htm|title=THE CATHOLIC RELIEF ACT, 1829|website=members.pcug.org.au}}</ref> | |||

| {{see|Law of Canada}} | |||

| Human rights in Canada are given legal protections by the dual mechanisms of constitutional entitlements and statutory human rights codes, both federal and provincial.<ref name="t313">Nancy Holmes, , Publications Canada, Law and Government Division, BP-279E, November 1991, revised October 2001.</ref><ref name="c275">{{cite web | last= Canadian Heritage | title=About human rights | website=Canada.ca | date=October 23, 2017 | url=https://www.canada.ca/en/canadian-heritage/services/about-human-rights.html | access-date=November 1, 2024}}</ref> | |||

| Nearly a century later, the ] passed similar legislation, ending the ] of the ] in the province, and recognizing instead the principle of "legal equality among all religious denominations". The act provided that the "free exercise and enjoyment of religious profession and worship" was protected by the Constitution and laws of the Province.<ref>''An Act to repeal so much of the Act of the Parliament of Great Britain passed in the Thirty-first year of the Reign of King George the Third, and Chaptered Thirty-one, as relates to Rectories, and the presentation of Incumbents to the same, and for other purposes connected with such Rectories'', Statutes of the Province of Canada, 14-15 Vict. (1851), c. 175, Preamble and s. 1.</ref> | |||

| Claims under the Constitution and under human rights laws are generally of a civil nature. Constitutional claims are adjudicated through the court system. Human rights claims are typically investigated by a human rights commission of the appropriate jurisdiction, either the ] or a provincial human rights commission. If a human rights claim goes to adjudication, it may be in front of a specialised human rights tribunal, such as the ] for federal claims, or a provincial human rights tribunal for claims under provincial law. In one province, Saskatchewan, there is no human rights tribunal and claims are adjudicated directly by the superior trial court of the province.<ref> Marie-Yosie Saint-Cyr, , ''Slaw – Canada’s online legal magazine'', August 4, 2011.</ref><ref></ref> A tribunal or court generally has broad remedial powers.<ref name="x828">{{cite web | last=Canadian Heritage | title=About human rights complaints | website=Canada.ca | date=October 23, 2017 | url=https://www.canada.ca/en/canadian-heritage/services/human-rights-complaints/about.html | access-date=November 1, 2024}}</ref> | |||

| === Confederation and onwards === | |||

| === Constitutional provisions === | |||

| {{main|Constitution of Canada}} | |||

| ] | |||

| The '']'' is part of the ].<ref name = Charter>.</ref> The Charter guarantees political, mobility, and equality rights and fundamental freedoms such as freedom of expression, freedom of assembly and freedom of religion for private individuals and some organisations.<ref name="v420">{{cite web | title=The rights and freedoms the Charter protects | website=Department of Justice Canada | date=April 12, 2018 | url=https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/csj-sjc/rfc-dlc/ccrf-ccdl/rfcp-cdlp.html | access-date=November 1, 2024}}</ref> The Charter only applies to governments, requiring them to respect the rights and freedoms it sets out.<ref name="a639">{{cite web | title=Who Does the Charter Apply to? | website=Alberta Civil Liberties Research Centre | url=https://www.aclrc.com/who-does-the-charter-apply-to | access-date=November 1, 2024}}</ref> Charter rights are enforced by legal actions in the criminal and civil courts, depending on the context in which a Charter claim arises.<ref name="n088">{{cite web | title=Section 11 – General: legal rights apply to those "charged with an offence" | website=Ministère de la Justice | date=November 9, 1999 | url=https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/csj-sjc/rfc-dlc/ccrf-ccdl/check/art11.html | access-date=November 1, 2024}}</ref> | |||

| In 1867, ] was created by the '']'' (now named the ''Constitution Act, 1867'').<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/Const/page-1.html|title=Consolidated federal laws of canada, Access to Information Act|first=Legislative Services|last=Branch|date=July 30, 2015|website=laws-lois.justice.gc.ca}}</ref> In keeping with British constitutional traditions, the act did not include an entrenched list of rights, other than specific rights relating to language use in legislatures and courts,<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/Const/page-7.html|title=Consolidated federal laws of canada, Access to Information Act|first=Legislative Services|last=Branch|date=July 30, 2015|website=laws-lois.justice.gc.ca}}</ref> and provisions protecting the right of certain religious minorities to establish their own separate and denominational schools.<ref name="s93">{{Cite web|url=https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/Const/page-4.html|title=Consolidated federal laws of canada, Access to Information Act|first=Legislative Services|last=Branch|date=July 30, 2015|website=laws-lois.justice.gc.ca}}</ref> Canadian law instead followed the British constitutional approach in which the (unenumerated) "]" had traditionally been defended by all the branches of the government (Parliament, the courts, and the Crown) collectively and sometimes in competition with each other. However, 20th century political and legal thought also emphasized the importance of ] and property rights as important aspects of liberty and the rule of law. This approach meant that what are now viewed as human rights concerns, based on personal circumstances, would be considered of lesser importance than contractual and property rights. | |||

| ==== Fundamental freedoms ==== | |||

| Human rights issues in the first seventy years of Canadian history thus tended to be raised in the framework of the constitutional ] between the federal and provincial governments. A person who was affected by a provincial law could challenge that law in the courts, arguing that it intruded on a matter reserved for the federal government. Alternatively, a person who was affected by federal law could challenge it in court, arguing that it intruded on a matter reserved for the provinces. In either case, the focus was primarily on the constitutional authority of the federal and provincial governments, not on the rights of the individual. | |||

| ] guarantees four fundamental freedoms: | |||

| * freedom of conscience and religion; | |||

| The division of powers is also the reason that the term "civil rights" is not used in Canada in the same way as it is used in other countries, such as the United States. One of the main areas of provincial jurisdiction is "Property and civil rights",<ref name="s93"/> which is a broad phrase used to encompass all of what is normally termed the ], such as contracts, property, torts/delicts, family law, wills, estates and successions and so on. This use of the phrase dates back to the ''Quebec Act, 1774''.<ref name = QuebecAct/> Given the broad, established meaning of "civil rights" in Canadian constitutional law, it has not been used in the more specific meaning of personal equality rights. Instead, the terms "human rights" / "droits de la personne" are used. | |||

| *freedom of thought, belief, opinion and expression, including freedom of the press and other media of communication; | |||

| ==== Early cases ==== | |||

| *freedom of peaceful assembly; | |||

| ===== ''Union Colliery Co. v. Bryden'' (1899) ===== | |||

| *freedom of association. | |||

| In '']'' a shareholder of Union Colliery Co. accused the company of violating the ''Coal Mines Regulation Act''. That law had been passed by the ] of ] and prohibited the hiring of people of Chinese origin, using an ] in the legislation.<ref>''Coal Mines Regulation Act'', RSBC 1897, c. 138, s. 4.</ref> The company successfully challenged the constitutionality of the act on the grounds that it dealt with a matter of exclusive federal jurisdiction, namely "Naturalization and Aliens".<ref></nowiki> UKPC 58], AC 580 (JCPC).</ref><ref name="s93"/> In reaching this conclusion, the ], at that time the highest court for the ], found that evidence which had been led at trial about the reliability and compentence of the Chinese employees of the colliery was irrelevant to the constitutional issue. The personal circumstances and ability of those employees did not relate to the issue of federal and provincial jurisdiction. | |||

| ===== |

===== Freedom of conscience and religion ===== | ||

| {{Main|Freedom of religion in Canada|Separate school}} | |||

| ] | |||

| Freedom of conscience and religion is protected by ] of the Charter.<ref>.</ref> Religious freedom is further protected by section 15 of the Charter, which promotes the pursuance of equality and the freedom from discrimination under enumerated or analogous grounds, one of which is religion.<ref name=Charter15>.</ref> | |||

| In a 1985 Supreme Court case, ''].,'' Chief Justice ] said that religious freedom in Canada includes freedom of religious speech, including "the right to entertain such religious beliefs as a person chooses, the right to declare religious beliefs openly and without fear of hindrance or reprisal, and the right to manifest religious belief by worship and practice or by teaching and dissemination."<ref></nowiki> 1 SCR 295], at para. 94.</ref> | |||

| The decision in ''Union Colliery'' did not establish any general principle of equality based on race or ethnicity. In each case, the issue of race or ethnicity was simply one fact the courts took into account in determining if a matter was within federal or provincial jurisdiction. For example, just three years later, in the case of ], a provincial law prohibiting people of Chinese, Japanese or Indian descent from voting in provincial elections was held to be constitutional.<ref>''Provincial Elections Act'', RSBC 1897, c. 67, s. 8.</ref> The Judicial Committee rejected a challenge to the provincial law brought by a naturalized Japanese-Canadian, ], who had been denied the right to vote in British Columbia provincial elections. The Judicial Committee held that control of the ] in provincial elections came within the province's exclusive jurisdiction to legislate with respect to the constitution of the province. Again, the personal circumstances of the individual, in this case whether naturalised or native-born, were not relevant to the issue of the constitutional authority of the province. There was no inherent right to vote.<ref>''Cunningham v Homma'', </nowiki> UKPC 60], 9 AC 151 (JCPC).</ref> | |||

| Concerns with regards to religious freedom remain with respect to public funding of religious education in some provinces,<ref>Richard Moon, , ''CBC News'', 28 May 2018.</ref> public interest limitations of religious freedom,<ref>Cristin Schmitz, {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221204215721/https://www.thelawyersdaily.ca/articles/6748/scc-affirms-7-2-ontario-and-b-c-regulators-denial-of-accreditation-to-twu-s-proposed-law-school |date=December 4, 2022 }}, ''The Lawyer's Daily'', LexisNexis Canada, 15 June 2018.</ref> state religious neutrality and religious dress,<ref>Canadian Human Rights Commission Statement: , 29 March 2019: "The Canadian Human Rights Commission is deeply concerned by Quebec’s announcement this week that it will seek to ban religious symbols for all provincial public servants in roles such as, police officers, judges, teachers and senior officials."</ref> and conflicts between anti-discrimination law and religiously motivated discrimination.<ref>Kathleen Harris, , ''CBC News'', 16 June 2018.</ref> | |||

| ===== ''Quong Wing v R'' (1914) ===== | |||

| Three provinces, Alberta, Ontario, and Saskatchewan, are constitutionally required to operate ]. The Supreme Court has held that the funding is not discriminatory under the Charter.<ref> </nowiki> 1 SCR 1148].</ref><ref> </nowiki> 3 SCR 609].</ref> On November 5, 1999, the ] held that Canada was in breach of the equality provisions of the ].<ref></ref> The Committee restated its concerns on November 2, 2005, observing that Canada had failed to "adopt steps in order to eliminate discrimination on the basis of religion in the funding of schools in Ontario."<ref>UN Human Rights Committee, ''Report of the Human Rights Committee, Volume I: Eighty-fifth Session (17 October-3 November 2005), Eighty-sixth Session (13-31 March 2006), Eighty-seventh Session (10-28 July 2006),'' 85th Sess, UN DOC A/61/40 (1 December 2006) 20 at 24.</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| ===== Freedom of expression ===== | |||

| Similarly, in the case of '']'', the Supreme Court upheld a ] law which prohibited businesses owned by anyone of Japanese, Chinese or other East Asian background from hiring any "white woman or girl" to work in the business.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://scc-csc.lexum.com/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/9673/index.do|title=Supreme Court of Canada - SCC Case Information - Search|first=Supreme Court of|last=Canada|date=January 1, 2001|website=scc-csc.lexum.com}}</ref><ref>''An Act to prevent the Employment of Female Labour in Certain Circumstances'', Statutes of Saskatchewan 1912, c. 17, s. 1.</ref> The court, by a 4–1 majority, found that the province had jurisdiction over businesses and employment, or alternatively that the law in question was in relation to local public morality, another area of provincial jurisdiction.<ref name="s93"/> The judges in the majority acknowledged that the law had an effect on some Canadians based on their race or ethnic origins, but that was not sufficient to take the case outside of provincial jurisdiction. The dissenting judge, Justice ], was the only one who would have struck down the statute, but as in the other cases, he based his conclusion on the division of powers, not on the rights of the individual. He would have held that the provincial act limited the statutory rights granted by the federal ''Naturalization Act'', and was therefore beyond provincial jurisdiction. | |||

| {{Main|Freedom of speech in Canada|Freedom_of_the_press#Canada|l2 = Freedom of the press in Canada}} | |||

| Freedom of expression is protected by ] of the ''Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms,'' which guarantees "Freedom of thought, belief, opinion and expression, including freedom of the press and other media of communication."<ref></ref> Freedom of speech and expression has constitutional protection in Canada but is not absolute. ] of the charter allows limitations on this freedom if it can be "justified in a free and democratic society".<ref></ref> The Charter protection works to ensure that all such limits are reasonable and strictly necessary. The approach by the Supreme Court on free expression has been that in deciding whether a restriction on freedom of expression is justified, the harms done by the particular form of expression must be weighed against the harm that would be done by the restriction itself.<ref>Julian Walker, "Hate Speech and Freedom of Expression: Legal Boundaries in Canada", ''Library of Parliament Research Publications,'' No. 2018-25-E, Library of Parliament, 2018.</ref> | |||

| In Canada, legal limitations on freedom of expression include: | |||

| ===== ''Christie v York Corporation'' (1940) ===== | |||

| * Sedition, fraud, specific threats of violence, and disclosure of classified information | |||

| Canadian courts also upheld discrimination in public places based on freedom of contract and property rights. For example, in '']'',<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://scc-csc.lexum.com/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/8489/index.do|title=Supreme Court of Canada - SCC Case Information - Search|first=Supreme Court of|last=Canada|date=January 1, 2001|website=scc-csc.lexum.com}}</ref> the plaintiff, a black man, was denied service at a bar at the ]. He sued for damages, arguing that the tavern was under a duty to provide services to all members of the public. The case reached the Supreme Court, which held by a 4–1 majority that the owner of the business had complete freedom of commerce and could refuse service to whomever it wished, on whatever grounds it wished. The lone dissenter, ], would have held that the Quebec statute regulating liquor sales to the public required restaurants to provide their service to all customers, without discrimination. | |||

| * Civil offences involving ], ], or ] | |||

| * Violations of ] | |||

| * Criminal offences involving ] | |||

| * Municipal by-laws that regulate signage or where protests may take place | |||

| Some limitations remain controversial due to concerns that they infringe on freedom of expression. | |||

| ===== ''The King v Desmond'' (1946) ===== | |||

| ===== Freedom of peaceful assembly ===== | |||

| ] | |||

| Freedom of peaceful assembly is protected by ] of the ''Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms'' guarantees to all Canadians freedom of peaceful assembly.<ref>.</ref> In 1987, the Supreme Court found in ''],'' that although being written as a separate right, section 2(c) was closely related to freedom of expression.<ref></nowiki> 1 SCR 313.]</ref> | |||

| Recent controversies involving concerns about freedom of assembly in Canada include the eviction of Occupy Canada's protests from public parks in 2011,<ref>Vilko Žbogar, et al. "Forcible Removal of Peaceful Protests in Canada: Submission to United Nations, Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association and Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression." The Law Union of Ontario, November 18. 2011.</ref> the possible effects of Bill C-51 on freedom of assembly,<ref>Alexandra Theodorakidis, {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220630233337/https://www.cjfe.org/bill_c_51_freedom_of_assembly_and_canadians_ability_to_protest |date=June 30, 2022 }} ''Canadian Journalists for Free Expression'', 25 June 2015.</ref> and CSIS surveillance of environmental and indigenous activists.<ref>, ''CBC News'', September 27, 2018.</ref> | |||

| ], a ], went to see a movie in a theatre in ], Nova Scotia. The owner of the theatre would only allow white people to sit on the main floor. Non-whites had to sit in the gallery. Desmond, who was from out of town, did not know of the policy. She bought a ticket for the movie and went onto the main floor. When the theatre employees told her to go to the gallery, she refused. The police were called and she was forcibly removed. Desmond spent a night in jail and was fined $20, on the basis that by sitting on the main floor when her ticket was for the gallery, she had deprived the provincial government of the additional tax for the main floor ticket: one cent. She sought to challenge her treatment, by an application for ] of the tax ruling. The court dismissed the challenge on the basis that the tax statute was neutral with respect to race. The judge suggested in his decision that the outcome might have been different if she had instead appealed the conviction, on the basis that the law was being used improperly by the theatre owner to enforce a "]" type of segregation.<ref>''The King v Desmond'' (1947), 20 MPR 297 (NS SC), at 299–301.</ref> | |||

| ===== Freedom of association ===== | |||

| In 2018, the ] announced that Viola Desmond would be the person shown on the new ten-dollar note.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.bankofcanada.ca/banknotes/vertical10/|title=Canada's Vertical $10 Note|website=www.bankofcanada.ca}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.ctvnews.ca/canada/our-family-will-go-down-in-history-desmond-s-sister-moved-by-new-10-bill-1.3833870|title='Our family will go down in history': Desmond's sister moved by new $10 bill|first=Jeff|last=Lagerquist|date=March 8, 2018|website=CTVNews}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.historicacanada.ca/content/heritage-minutes/viola-desmond|title=Viola Desmond | Historica Canada|website=www.historicacanada.ca}}</ref> | |||

| Freedom of association is protected by ]) of the ''Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.''<ref>.</ref> This section provides Canadians the right to establish, belong to and maintain to any sort of organization unless that organization is otherwise illegal. This right only protects the right of individuals to form associations and not the activities of the associations themselves.<ref>"Scope of freedom of association", , Department of Justice Canada, July 31, 2023.</ref> | |||

| ===== ''Noble v Alley'' (1955) ===== | |||

| Generally, this Charter right is used in the labour context where employees are given the right to associate with certain unions or other similar groups to represent their interests in labour disputes or negotiations. The Supreme Court also found in '']'' (2001)'','' that the right to freedom of association also includes, at least to some degree, the freedom not to associate,<ref>"Freedom from compelled association", , Department of Justice Canada, July 31, 2023</ref> but still upheld a law requiring all persons working in the province's construction industry to join a designated union.<ref> </nowiki> 3 SCR 209], at paras 19, 195, 196, 220.</ref> | |||

| '']'' was a challenge to a ] for the sale of land at a cottage resort. The owner of the land had bought it with a requirement from an earlier owner that the land not be sold to Jewish or non-white people. The owner wished to sell it to an individual who was Jewish. The owner challenged the restrictive covenant, over the opposition of other residents in the cottage resort. The Supreme Court held that the covenant was not enforceable on the basis that it was too vague, and that restrictive covenants on land had to be related to land use, not the personal characteristics of the owner.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://scc-csc.lexum.com/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/3691/index.do|title=Supreme Court of Canada - SCC Case Information - Search|first=Supreme Court of|last=Canada|date=January 1, 2001|website=scc-csc.lexum.com}}</ref> | |||

| === |

==== Social equality ==== | ||

| Progressive rights issues that Canada has addressed include; ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] and ], ] and political rights.<ref> {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081203171021/http://www.pch.gc.ca/progs/pdp-hrp/canada/themes_e.cfm |date=December 3, 2008 }}</ref> | |||

| ===== Race ===== | |||

| In 1938 there was a development in judicial protection of rights. The government of the province of ] had passed a series of laws to implement its ] platform, and had come under heavy media criticism. In response, the Legislature enacted the '']'', which would give the government the power to direct media's coverage of the government. The federal government referred several of the Alberta bills to the Supreme Court for a ]. Three of the six members of the court found that public comment on the government, and freedom of the press, are so important to a democracy that there is an ] in Canada's Constitution, to protect those values. The court suggested that only the federal Parliament could have the power to impinge on political rights protected by the implied bill of rights. The ''Accurate News and Information Act'' was therefore unconstitutional.<ref> SCR 100</nowiki>]; appeal dismissed, UKPC 46</nowiki>].</ref> The Supreme Court has not, however, used the "implied bill of rights" in very many subsequent cases. | |||

| {{See also|Racism in Canada|Multiculturalism in Canada#Historical context}} | |||

| ] of the ''Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms'' guarantees that "Every individual is equal before and under the law and has the right to the equal protection and equal benefit of the law without discrimination and, in particular, without discrimination based on race."<ref name=Charter15/> | |||

| Throughout Canadian history, there has been a pattern of systemic racial discrimination, particularly towards indigenous persons,<ref>Reading, Charlotte, and Sarah de Leeuw. "Aboriginal experiences with racism and its impacts." Technical Report. Prince George, British Columbia, Canada: National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health, 2014.</ref> but to other groups as well, including African,<ref name=":5">Working Group of Experts on People of African Descent, ''Report of the Working Group of Experts on People of African Descent on its mission to Canada'', UNHRC, 36th Sess, UN DOC A/HRC/36/60/Add.1 (16 August 2017) at 2-3.</ref> Chinese,<ref>Mar, Lisa Rose. “Beyond Being Others: Chinese Canadians as National History.” ''The British Columbian Quarterly'', No. 156/7, 1 May 2008, pp. 13–34.</ref> Japanese,<ref>Sunahara, Ann Gomer. ''The Politics of Racism: the Uprooting of Japanese Canadians during the Second World War''. J. Lorimer, 1981.</ref> South Asian,<ref>Johnston, Hugh. ''The East Indians in Canada''. No. 5. Ottawa: Canadian Historical Association, 1984.</ref> Jewish,<ref>Robinson, Ira. ''A History of antisemitism in Canada''. Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press, 2015.</ref> and Muslim<ref>Helly, Denise. "Islamophobia in canada? women's rights, modernity, secularism." ''Religions in the Public Sphere: Accommodating Religious Diversity in the Post-Secular Era, Recode. Responding to Complex Diversity in Europe and Canada,'' Working Paper No. 11, 2012.</ref> Canadians. These patterns of discrimination persist today. The ] Working Group of Experts on People of African Descent issued a report in 2017 finding "clear evidence that racial profiling is endemic in the strategies and practices used by law enforcement" in Canada.<ref name=":5" /> In 2018 Statistics Canada reported that members of immigrant and visible minority populations, compared with their Canadian-born and non-visible minority counterparts, were significantly more likely to report experiencing some form of discrimination on the basis of their ethnicity or culture, and race or skin colour.<ref>Simpson, Laura. "Violent victimization and discrimination among visible minority populations, Canada, 2014." ''Juristat'': ''Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics'', Statistics Canada, Apr. 12. 2018.</ref> | |||

| ===''Saskatchewan Bill of Rights'' (1947) === | |||

| ===== Sex ===== | |||

| {{Main|Saskatchewan Bill of Rights}} | |||

| {{Main|Feminism in Canada|Women's suffrage in Canada}} | |||

| ] in Toronto. Approximately 60 000 protestors attended.<ref>"10 striking signs from the Women's March in Toronto". CBC News. January 21, 2017. Retrieved January 23, 2017.</ref>]] | |||

| Within the Canadian context, human rights protections for women consist of constitutional entitlements and federal and provincial statutory protections'''.''' ] of the ''Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms'' guarantees that all "the rights and freedoms referred to in it are guaranteed equally to male and female persons".<ref>.</ref> Section 28 is not a right in of itself, as it does not state that men and women are equal; this is done by section 15. Instead, section 28 ensures that men and women have equal claim to rights listed in the Charter.<ref>Diana Majury, , ''Osgoode Hall Law Journal'', vol. 40, no. 3, 2002, 297-336, at pp. 307–308.</ref> | |||

| ], and remained so for the next 100 years.<ref name="Bromley2012"/> In 1969, the federal government of Prime Minister ] passed the '']'' which legalized therapeutic abortions, as long as a committee of doctors certified that continuing the pregnancy would likely endanger the woman's life or health.<ref name="Bromley2012">{{cite book|author=Victoria Bromley|title=Feminisms Matter: Debates, Theories, Activism|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=UfHTPNPymsMC&pg=PA26|date= 2012|publisher=University of Toronto Press|isbn=978-1-4426-0502-2|pages=26–32}}</ref> In 1988, the ] ruled in '']'' that the existing law was unconstitutional, and struck down the 1969 Act.<ref name="Jhappan2002">{{cite book|author=Radha Jhappan|title=Women's Legal Strategies in Canada|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XGMienMpAaIC&pg=PA335|year=2002|publisher=University of Toronto Press|isbn=978-0-8020-7667-0|pages=335–338}}</ref> By a 5-2 ruling, the Court found that the 1969 abortion law violated a woman's right to "security of the person" guaranteed under ].<ref name = Morgentaler1988></nowiki> 1 SCR 30.]</ref> | |||

| The events leading up to World War II, and the genocidal practices of the Nazi government of Germany, had a major effect on the protection of human rights in Canada. ], at that time a ] from Saskatchewan, was in Europe in 1936 and witnessed the ] of that year, which had a significant effect on him.<ref name="Patriation"></ref> When he was elected Premier of Saskatchewan, one of his first goals was to entrench human rights in Canada's constitution. At the 1945 Dominion-Provincial Conference he proposed adding a bill of rights to the '']'', but was not able to gain support for the proposal.<ref name="Patriation" /> Instead, in 1947, the Government of Saskatchewan introduced the ], the first bill of rights in the Commonwealth since the ].<ref name="Patriation" /><ref name="SaskBill">''The Saskatchewan Bill of Rights Act, 1947'', SS 1947, c. 35.</ref><ref>Bill of Rights, 1688 (Eng), 1 Will & Mar (2d Sess), c 2.</ref> | |||

| ===== Disability ===== | |||

| The ''Saskatchewan Bill of Rights'' provided significant protections for fundamental freedoms: | |||

| {{see|Disability in Canada|Accessible Canada Act}} | |||

| The rights of disabled persons in Canada are protected under the ''Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms'' in section 15, which explicitly prohibits discrimination on the basis of mental or physical disability.<ref name=Charter15/> Canada ratified the UN '']'' in 2010.<ref>“Canada Ratifies United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.” ''Ccdonline'', Council of Canadians with Disabilities, 11 Mar. 2010, ccdonline.ca/en/international/un/canada/crpd-pressrelease-11March2010.</ref> | |||

| ===== LGBT ===== | |||

| * right to freedom of conscience and religion (s. 3); | |||

| {{Main|LGBT rights in Canada}} | |||

| * right to free expression (s. 4); | |||

| ] | |||

| * right to peaceable assembly and association (s. 5); | |||

| The Supreme Court of Canada established in ''],'' that sexual orientation was "a deeply personal characteristic that is either unchangeable or changeable only at unacceptable personal costs", and therefore was one of the analogous grounds to the explicitly mentioned groups in ].<ref>Egan v. Canada, 2 S.C.R. 514 at para. 5, finding sexual orientation to be an analogous ground under the Charter but upholding the exclusion of same-sex partners from the definition of spouse in the Old Age Security Act; see also Vriend v. Alberta, 1 S.C.R. 493 (reading “sexual orientation” into the prohibited grounds of discrimination in the Individual’s Rights Protection Act).</ref> As the explicitly named grounds do not exhaust the scope of section 15, this reasoning has been extended to protect gender identity and status as a transgender person in ''CF v. Alberta (2014)''; however, it has not been formally recognized as an analogous ground.<ref>C.F. v. Alberta (Vital Statistics), ABQB 237, par. 39.</ref> | |||

| * right to freedom from arbitrary imprisonment and right to immediate judicial determination of a detention (s. 6); | |||

| * right to vote in provincial elections (s. 7).<ref name="SaskBill" /> | |||

| ==== Language ==== | |||

| ===''Canadian Bill of Rights'' (1960) === | |||

| {{Main|Official bilingualism in Canada}} | |||

| The perceived failure of Canada to establish the equality of the French and English languages was one of the main reasons for the rise of the ], during the ]. Consequently, the federal government began officially adopting multicultural and bilingual policies in the 1970s and 1980s. | |||

| {{Main|Canadian Bill of Rights}} | |||

| The ''Constitution Act, 1982'' established French and English as Canada's two official languages. Guarantees for the equal status of the two official languages are provided in sections 16–23 of the ''Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms''. ] guarantees that French and English “have equality of status and equal rights and privileges.” These sections of the charter provide a constitutional guarantee for the equal status of both languages in Parliament, in all federal government institutions, and federal courts.<ref name="j820">{{cite web | last=Heritage | first=Canadian | title=English and French: Towards a substantive equality of official languages in Canada | website=Canada.ca | date=February 19, 2021 | url=https://www.canada.ca/en/canadian-heritage/corporate/publications/general-publications/equality-official-languages.html | access-date=November 1, 2024}}</ref> | |||

| ] successfully introduced the '']'', the precursor of the '']''.]] | |||

| ====Multiculturalism ==== | |||

| ], also from Saskatchewan, was another early proponent of protecting human rights in Canada. He wrote a first draft of a bill of rights as a young lawyer in the 1920s. Elected a Member of Parliament in 1940, he regularly introduced a motion each year from 1946 onwards, calling for Parliament to enact a bill of rights at the federal level. He was concerned that there be a guarantee of equality for all Canadians, not just those who had English or French heritage. He also wanted protection for basic freedoms, such as freedom of expression.<ref name="Patriation" /> | |||

| {{main|Multiculturalism in Canada}} | |||

| ] is reflected in the Charter through ] which states that "This Charter shall be interpreted in a manner consistent with the preservation and enhancement of the multicultural heritage of Canadians". | |||

| === Federal legislation === | |||

| In 1960, by then the Prime Minister of Canada, Diefenbaker introduced the '']''. This federal statute provide guarantees, binding on the federal government, to protect freedom of speech, freedom of religion, equality rights, the right to life, liberty and security of the person, and property rights. It also sets out significant protections for individuals charged with criminal offences.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/c-12.3/page-1.html|title=Consolidated federal laws of canada, ''Canadian Bill of Rights''|first=Legislative Services|last=Branch|date=December 31, 2002|website=laws-lois.justice.gc.ca}}</ref> | |||

| ==== Discrimination==== | |||

| In 1977, the federal Parliament enacted the '']'' to prohibit discrimination in matters under federal jurisdiction. The act applies throughout Canada, and protects people in Canada from discrimination by the federal government, or by federally regulated enterprises, such as banks, airlines, interprovincial railways, telecommunications, and maritime shipping.<ref name =CHRA>{{Cite canlaw|short title =Canadian Human Rights Act|abbr =RSC|year =1985|chapter =C H-6|section =2.|link =https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/h-6/page-1.html#h-256795}}</ref> | |||

| The act sets out a defined list of prohibited grounds of discrimination: | |||

| The ''Canadian Bill of Rights'' suffered from two drawbacks. First, as a statute of the federal Parliament, it was only binding on the federal government. The federal parliament does not have the constitutional authority to enact laws which bind the provincial governments in relation to human rights. Second, and following from the statutory nature of the bill, the courts were reluctant to use the provisions of the bill as the basis for judicial review of federal statutes. Under the doctrine of ], the courts were concerned that one Parliament cannot bind future Parliaments. | |||

| {{div col|colwidth=30em}} | |||

| * race | |||

| * national or ethnic origin | |||

| * colour | |||

| * religion | |||

| * age | |||

| * sex (including pregnancy and childbirth) | |||

| * sexual orientation | |||

| * gender identity or expression | |||

| * marital status | |||

| * family status | |||

| * genetic characteristics | |||

| * disability | |||

| * conviction for an offence for which a pardon has been granted or in respect of which a record suspension has been ordered.<ref></ref> | |||

| {{div col end}} | |||

| When the act was passed in 1977, the list of prohibted grounds of discrimination was shorter.<ref name=CHRA77>{{Cite canlaw|short title =Canadian Human Rights Act|abbr =SC|year =1977|chapter =33.|link =https://historyofrights.ca/wp-content/uploads/statutes/CN_HRA2.pdf}}</ref> Additional prohibited grounds have been added over time. | |||

| ====Disability discrimination==== | |||

| In two significant cases, the Supreme Court rejected attempts to use the Bill of Rights to review legislation. In '']'', the court rejected a gender-based challenge to unemployment benefits which did not apply to pregnant women, while in '']'', the court rejected a challenge based on gender and indigenous status to provisions of the '']''. A notable exception was '']'', which did use the Bill of Rights to overturn a different provision of the ''Indian Act''. | |||

| When the ''Canadian Human Rights Act'' was passed in 1977, it had a more limited prohibition on disability discrimination than is currently the case. Section 3 of the act prohibited discrimination on the basis of "physical disability", and only in matters related to employment.<ref name=CHRA77/> In 1983, Parliament expanded this protection to be on the basis of diability generally, which includes mental disability, and removed the restriction that it only related to matters of employment.<ref name=CHRA83>''An Act to amend the Canadian Human Rights Act and to amend certain other Acts in consequence thereof'', SC 1980-81-82-83, c 143, s. 2.</ref> | |||

| Several programs and services are also subject to specific legislation requiring inclusive approaches. For example, '']'' requires that polling stations be accessible (e.g., providing material in multiple formats, open and closed caption videotapes for voters who are hearing impaired, a voting template for people with visual disabilities, and many other services).<ref>{{Cite canlaw|short title =Canada Elections Act|abbr =SC |year =2000|chapter =9|section =ss 119(1)(d), 121(1), 154(1)(2), 168(6), 243(1).|link = https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/e-2.01/FullText.html}}</ref> | |||

| === Human Rights Acts === | |||

| Other laws with disability provisions include section 6 of the ''],'' which regulates evidence-gathering involving persons with mental and physical disabilities,<ref>{{Cite canlaw|short title =Canada Evidence Act|abbr =RSC|year =1985|chapter =C-5|section =6(1),(2).|link =https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/c-5/page-1.html#h-137457}}</ref> and the ''Employment Equity Act'', which requires private and public sector employers under federal jurisdiction to increase representation of persons with disabilities.<ref name=EEQ/> | |||

| The other provinces began to follow Saskatchewan's lead and enacted human rights laws: Ontario (1962), Nova Scotia (1963), Alberta (1966), New Brunswick (1967), Prince Edward Island (1968), Newfoundland (1969), British Columbia (1969), Manitoba (1970) and Quebec (1975). In 1977, the federal government enacted the '']''. | |||

| Federal benefits include the Canada disability savings bond, and the Canada disability savings grant which are deposited into the Registered Disability Savings Plan (RDSP) of low-income families, as established by the Disability Savings Act.<ref> </ref> Disabled persons may also be eligible for the Disability Tax Credit, and the families of children with disabilities are eligible for the Canada Child Disability Benefit, a tax-free monthly payment.<ref> </ref> | |||

| == Significant historical cases == | |||

| ====Sexual orientation, gender identity and expression==== | |||

| In addition to these particular court cases, there were also general cases which arose in Canada, prior to the enactment of human rights legislation. | |||

| Neither sexual orientation nor gender identity and expression were included in the ''Canadian Human Rights Act'' when it was passed in 1977. Parliament amended the act in 1996 to include sexual orientation as a prohibited ground of discrimination.<ref></ref><ref></ref> Parliament added gender identity or expression as additional prohibited grounds of discrimination through '']'' in 2017.<ref></ref><ref></ref> | |||

| In 2005, following a series of court cases across the country which held that same-sex marriage was constitutionally required, the federal Parliament passed the ''Civil Marriage Act'', which made same-sex marriage legal throughout Canada. Canada was the fourth country in the world, and the first in the Americas, to implement same-sex marriage.<ref></ref> | |||

| ===Komagata Maru incident=== | |||

| {{Main|Komagata Maru incident}} | |||

| The Komagata Maru incident occurred 1914 when a group of Indians, all ], arrived in ] with the intention of settling in Canada.<ref>{{cite book|title=The Voyage of the Komagata Maru: the Sikh challenge to Canada's colour bar|year=1989|publisher=University of British Columbia Press|location=Vancouver|isbn=0-7748-0340-1|pages=81, 83}}</ref> They were denied entry because of their race. One of the Sikh passengers, Jagat Singh Thind, was the youngest brother of ], an Indian-American Sikh writer and lecturer on "spiritual science" who was involved in an important legal battle over the rights of Indians to obtain U.S. citizenship ('']'').], east of Edmonton, Alberta. Includes a map showing the locations of the internment camps across Canada. Installed 11 August 2002.]] | |||

| The Canadian federal government created the LGBTQ2 Secretariat in 2016 to support the integration of LGBTQ2 considerations into the everyday work of the Government of Canada.<ref>Privy Council Office. “About the LGBTQ2 Secretariat.” ''Canada.ca'', Government of Canada, 17 May 2018.</ref> | |||

| ===World War I treatment of Ukrainian Canadians=== | |||

| {{Main|Ukrainian Canadian internment}} | |||

| The Ukrainian Canadian internment was part of the confinement of "enemy aliens" in Canada during and for two years after the end of the ], lasting from 1914 to 1920, under the terms of the '']''. About 4,000 Ukrainian men and some women and children of ] were kept in twenty-four ] camps and related work sites – also known, at the time, as concentration camps.<ref name="27camps">{{cite web|url=http://www.infoukes.com/history/internment/gulag/|title=Internment of Ukrainians in Canada 1914-1920 |access-date=1 April 2010}}</ref> Many were released in 1916 to help with the mounting labour shortage. | |||

| On November 28, 2017, ] delivered ] in the ] to individuals harmed by federal legislation, policies and practices that led to the discrimination against LGBTQ2 people in Canada.<ref>Kathleen Harris, , ''CBC News'', November 29, 2017.</ref> He introduced the ''Expungement of Historically Unjust Convictions Act,'' which passed Parliament and received ] in June 2018. The legislation gives individuals who had been convicted of offences related to consensual same-sex activity the ability to apply to the Parole Board of Canada to have the record of a conviction expunged. If the board grants the application, it has the same effect as a pardon.<ref></ref><ref>{{Cite canlaw|short title =Expungement of Historically Unjust Convictions Act|abbr =SC|year =2018|chapter =11.|link = https://www.laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/AnnualStatutes/2018_11/page-1.html#h-3}}</ref> | |||

| === Chinese head tax and Chinese Immigration Act of 1923 === | |||

| {{Main|Chinese head tax in Canada}} | |||

| The Chinese head tax was a fixed fee charged to each ] person entering Canada. The head tax was first levied after the ] passed the ] and was meant to discourage Chinese people from entering Canada after the completion of the ]. The tax was abolished by the ], which stopped Chinese immigration altogether, except for business people, clergy, educators, students, and other categories.<ref name="JamesMorton">James Morton. "]". Vancouver, BC: J. J. Douglas, 1974.</ref> | |||

| ====Sex discrimination==== | |||

| ===World War II treatment of Japanese Canadians=== | |||

| {{Main|Japanese Canadian internment}} | |||

| Japanese Canadian internment refers to confinement of ] in ] during ]. The internment began in December 1941, after the attack by carrier-borne forces of ] on ] naval and army facilities at ]. The Canadian federal government gave the internment order based on speculation of sabotage and espionage, although the RCMP and defence department lacked proof.<ref name="Maryka Omatsu 1992">Maryka Omatsu, Bittersweet Passage and the Japanese Canadian Experience (Toronto: Between the Lines, 1992), 12.</ref> Many interned children were brought up in these camps, including ], ], and ]. The Canadian government promised the Japanese Canadians that their property and finances would be returned upon release; however, these assets were sold off cheaply at auctions.<ref name="Last 3 Years 1948">"Jap Expropriation Hearing May Last 3 Years, Is Estimate," Globe and Mail (Toronto: January 12, 1948)</ref> | |||

| While sex was included as a prohibited ground of discrimination when the ''Canadian Human Rights Act'' was passed in 1977, in 1978 the Supreme Court of Canada unanimously held that pregnancy was not included in the similar prohibition on sexual discrimination in the ''Canadian Bill of Rights''.<ref></nowiki> 1 SCR 183.]</ref> In 1983, Parliament amended s. 3 of the ''Canadian Human Rights Act'' to expressly state that discrimination on the basis of sex includes pregnancy and childbirth.<ref name=CHRA83/> | |||

| ]]] | |||

| Beginning in the 1960s, Canada launched a series of affirmative action programs aimed at increasing representation of women in the federal public service.<ref>{{Cite web|last=Government of Canada|first=Public Services and Procurement Canada|date=2002-07-01|title=History of employment equity in the public service and the Public Service Commission of Canada / by the Equity and Diversity Directorate. : SC3-159/2011E-PDF - Government of Canada Publications - Canada.ca|url=http://publications.gc.ca/site/eng/406061/publication.html|access-date=2020-11-14|website=publications.gc.ca}}</ref> Today, the '']'' requires private and public sector employers under federal jurisdiction to increase representation of women, who are one of the four designated groups protected by the act.<ref name=EEQ>{{Cite canlaw|short title =Employment Equity Act|abbr =SC|year =1995|chapter =44.|link =https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/E-5.401/index.html}}</ref> | |||

| ===Cold War forced relocation=== | |||

| {{Main|High Arctic relocation}} | |||

| In the early 1950s and in the context of the ], the federal government forcibly relocated 87 ] citizens to the High ] as human symbols of Canada's assertion of ownership of the region. The Inuit were told that they would be returned home to ] after a year if they wished, but this offer was later withdrawn as it would damage Canada's claims to the High Arctic; they were forced to stay.<ref>McGrath, Melanie. ''The Long Exile: A Tale of Inuit Betrayal and Survival in the High Arctic''. Alfred A. Knopf, 2006 (268 pages) Hardcover: {{ISBN|0-00-715796-7}} Paperback: {{ISBN|0-00-715797-5}}</ref> In 1993, after extensive hearings, the ] issued ''The High Arctic Relocation: A Report on the 1953–55 Relocation''.<ref>''The High Arctic Relocation: A Report on the 1953–55 Relocation'' by René Dussault and George Erasmus, produced by the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, published by Canadian Government Publishing, 1994 (190 pages){{cite web|url=http://www.fedpubs.com/subject/aborig/arctic_reloc.htm |title=The High Arctic Relocation |access-date=2010-06-20 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20091001232453/http://www.fedpubs.com/subject/aborig/arctic_reloc.htm |archive-date=2009-10-01 }}</ref> The government paid compensation and in 2010 issued a formal apology.<ref>{{cite web |date=15 September 2010 |title=Apology for the Inuit High Arctic relocation |url=https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1100100016115/1534786491628 |publisher=]}}</ref>] | |||

| === |

====Multiculturalism Act==== | ||

| ] is reflected at the federal level through the '']''. Enacted in 1988, the act affirms that the federal government recognizes the multicultural heritage of Canada, the rights of indigenous persons, minority cultural rights, and the right to social equality within society and under the law regardless of race, colour, ancestry, national or ethnic origin, creed or religion.<ref name="s993">{{cite web | last=Canadian Heritage | title=About the Canadian Multiculturalism Act | website=Canada.ca | date=June 3, 2024 | url=https://www.canada.ca/en/canadian-heritage/services/about-multiculturalism-anti-racism/about-act.html | access-date=November 1, 2024}}</ref> | |||

| {{Main|Canadian residential school system}} | |||

| The Indian residential schools of Canada were a network of ] schools for ] (], ], and ]) funded by the Canadian government's ], and administered by ], most notably the ] and the ].<ref name="Milloy1999">{{cite book|author=John S. Milloy|title=A National Crime: The Canadian Government and the Residential School System, 1879 to 1986|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=TSGmglyxgzkC&pg=PA51|access-date=23 October 2012|date=31 May 1999|publisher=Univ. of Manitoba Press|isbn=978-0-88755-646-3|pages=51–65}}</ref> The system had origins in pre-Confederation times, but was primarily active following the passage of the '']'' in 1876, until the mid-twentieth century. The last residential school was not closed until 1997.<ref name="Milloy1999"/><ref name=":22">{{Cite web|date=June 4, 2021|title=Your questions answered about Canada's residential school system|url=https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/canada-residential-schools-kamloops-faq-1.6051632|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210728101859/https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/canada-residential-schools-kamloops-faq-1.6051632|archive-date=July 28, 2021|access-date=July 28, 2021|website=]}}</ref> | |||

| === Provincial and territorial legislation === | |||

| == Contemporary human rights issues == | |||

| {{main|Human Rights Act (Nunavut)|Human Rights Code (British Columbia)|Human Rights Code (Ontario)|Quebec Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms|Saskatchewan Bill of Rights}} | |||

| {{Expand section|date=October 2022}} | |||

| At the provincial and territorial level, human rights are protected by the Charter and by provincial human rights legislation. The Charter applies to provincial and territorial governments and agencies, and also local governments created by provincial and territorial law, such as municipalities and school boards.<ref name="g710b">{{cite web | title=Charterpedia | website=Section 32(1) – Application of the Charter | date=November 9, 1999 | url=https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/csj-sjc/rfc-dlc/ccrf-ccdl/check/art321.html | access-date=November 1, 2024}}</ref> Provincial and territorial human rights laws also apply to governments, and more generally to activities under provincial or territorial jurisdiction, such as most workplaces, rental accommodation, education, and trade unions. | |||

| Although there is variation among the matters covered by federal, provincial and territorial, they all generally provide anti-discrimination protections concerning employment practices, housing, and the provision of goods and services generally available to the public.<ref name=":0">Gallagher-Louisy, Cathy and Jiwon Chun. "Overview of Human Rights Codes by Province and Territory in Canada." Canadian Centre for Diversity and Inclusion. January 2018.</ref> The laws prohibit discrimination on enumerated personal characteristics, such as race, sex, religion or sexual orientation.<ref name="w830">{{cite web | title=Canadian Human Rights Act | website=Site Web de la législation (Justice) | date=August 19, 2024 | url=https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/h-6/section-3.html | access-date=November 1, 2024}}</ref> | |||

| === Clean water access in First Nation communities === | |||

| {{Main|Long-term drinking water advisories}} | |||

| Many First Nation communities throughout Canada experience frequent and long term drinking water advisories, the longest of which at ] having been in continual effect since 1995.<ref name=":6">{{Cite news |last1=Swampy |first1=Mario |last2=Black |first2=Kerry |date=7 May 2021 |title=Tip of the iceberg: The true state of drinking water advisories in First Nations |work=UCalgary News |url=https://ucalgary.ca/news/tip-iceberg-true-state-drinking-water-advisories-first-nations |access-date=9 April 2023}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last= |date=2023-02-01 |title=NESKANTAGA FIRST NATION MARK 28th YEAR IN BOIL WATER ADVISORY |url=http://www.matawa.on.ca/neskantaga-first-nation-mark-28th-year-in-boil-water-advisory/ |access-date=2023-04-09 |website=Matawa First Nations |language=en-CA}}</ref> Access to safe drinking water is classified as a human right by many international treaties ratified by Canada, including the ], the ], and the ].<ref name=":7">{{Cite journal |last=Klasing |first=Amanda |date=2019-10-23 |title=The Human Right to Water |url=https://www.hrw.org/report/2019/10/23/human-right-water/guide-first-nations-communities-and-advocates |journal=] |language=en}}</ref> The failure to adequately address the water advisories has led to condemnation by many human rights bodies including the ].<ref name=":7" /> In 2015 the Canadian government committed to ending all long term drinking water advisories by March 2021 and would successfully reduce the number of water advisories by 81% as of February 2023.<ref name=":6" /><ref name=":8">{{Cite web |last=Canada |first=Government of Canada; Indigenous and Northern Affairs |date=2017-09-27 |title=Ending long-term drinking water advisories |url=https://www.sac-isc.gc.ca/eng/1506514143353/1533317130660 |access-date=2023-04-09 |website=Canada.ca}}</ref> While the Canadian government would fail to meet it's 2021 deadline, efforts are ongoing, however no new deadline has been set, with 32 advisories still being in effect as of February 2023.<ref name=":6" /><ref name=":8" /> | |||

| All Canadian provinces and territories have legislation prohibiting discrimination on the basis of race, colour, and national or ethnic origin in employment practices, housing, the provision of goods and services, and in accommodation or facilities customarily available to the public.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

| === Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women === | |||

| {{Main|Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women}} | |||

| Within Canada, indigenous women and girls are disproportionately the victims of ] and ] with thousands of such cases occurring in the past 30 years.<ref>{{Cite news |last=Cecco |first=Leyland |date=2022-12-02 |title='Rage, despair, disgust': Canada reels from killings of Indigenous women |language=en-GB |work=The Guardian |url=https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/dec/02/canada-murders-indigenous-women |access-date=2023-04-09 |issn=0261-3077}}</ref> Indigenous women have been found to represent 10% of all women reported missing for longer than 30 days, and are 6 times more likely to be the victims of homicide compared to non-indigenous women.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Government of Canada |first=Department of Justice |date=2017-10-31 |title=Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls - JustFacts |url=https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/jr/jf-pf/2017/july04.html |access-date=2023-04-09 |website=www.justice.gc.ca}}</ref> As a result of the crisis the Canadian government conducted a ] from 2016 to 2019, with the inquiry concluding that the crisis represented a continued “race, identity and gender-based genocide.”<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://www.mmiwg-ffada.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Final_Report_Vol_1a-1.pdf |title=Reclaiming Power and Place: the Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls |publisher=National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls |year=2019 |isbn=978-0-660-29274-8 |volume=1a |pages=5}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |last=Barrera |first=Jorge |date=31 May 2019 |title=National inquiry calls murders and disappearances of Indigenous women a 'Canadian genocide' |work=] |url=https://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/genocide-murdered-missing-indigenous-women-inquiry-report-1.5157580 |access-date=8 April 2023}}</ref> | |||

| As of 2018, all Canadian provinces and territories have legislation prohibiting discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity or expression in employment practices, housing, the provision of goods and services, and in accommodation or facilities customarily available to the public.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

| ===Modern international view of indigenous rights=== | |||

| On April 29, 2022, the ] sent a letter that criticized Canada over its ill-treatment of Indigenous people who opposed the construction of two pipelines in ].<ref name="kitchener.citynews.ca">{{cite web | url=https://kitchener.citynews.ca/national-news/un-committee-criticizes-canada-over-handling-of-indigenous-pipeline-opposition-5357794 | title=UN committee criticizes Canada over handling of Indigenous pipeline opposition }}</ref> The letter called on Canada to "immediately cease forced evictions" of indigenous protesters by police and halt construction on the two pipelines until it obtains consent from the affected indigenous communities.<ref name="kitchener.citynews.ca"/> The letter alleges that authorities intimidated and pushed indigenous people off their lands by using surveillance and force.<ref name="kitchener.citynews.ca"/> | |||

| There are several provincial and territorial programs focused on income, housing, and employment supports for persons living with disabilities.<ref>Audit and Evaluation Sector Indian and Northern Affairs Canada. “Evaluation of the Income Assistance Program.” Indian and Northern Affairs., 2007, pp. 32–33. ''Government of Canada Publications'', publications.gc.ca/site/eng/479530/publication.html.</ref> | |||

| == Current legal framework == | |||

| In January 2018, the ] released a report comparing provincial legislation regarding human rights. Every province includes slightly different "prohibited grounds" for discrimination, covers different areas of society (e.g. employment, tenancy, etc.), and applies the law slightly differently. For example, in ], the '']'' directs the Nunavut Human Rights Tribunal to interpret the law so as not to conflict with the '']'' and to respect the principles of ], described as "Inuit beliefs, laws, principles and values along with traditional knowledge, skills and attitudes." Nunavut is unique in Canada tying its human rights code to an indigenous rather than a European-derived philosophical foundation.<ref>{{cite web | url = http://ccdi.ca/media/1414/20171102-publications-overview-of-hr-codes-by-province-final-en.pdf | title = Overview of Human Rights Codes by Province and Territory in Canada | date = January 2018 | website = Canadian Centre for Diversity and Inclusion | access-date = September 21, 2020}}</ref> | |||

| === Domestic legal protection framework === | |||

| ] | |||

| Human rights in Canada are now given legal protections by the dual mechanisms of constitutional entitlements and statutory human rights codes, both federal and provincial | |||

| == Legal history and context == | |||

| The '']'' is part of the ]. The charter guarantees political, mobility, and equality rights and fundamental freedoms such as freedom of expression, freedom of assembly and freedom of religion. It only applies to governments, and not to private individuals, businesses or other organizations. Charter rights are enforced by legal actions in the criminal and civil courts, depending on the context in which a charter claim arises. | |||

| === Colonial period === | |||

| There are two main pieces of human rights legislation which apply at the federal level: the charter and the statutory '']''. The ''Canadian Human Rights Act'' protects people in Canada from discrimination when they are employed by or receive services from the federal government, or private companies that are regulated by the federal government.<ref>''Canadian Human Rights Act'', RSC 1985, c H-6.</ref> The act applies throughout Canada, but only to federally regulated enterprises. Approximately 15% of workplaces are covered by the ''Canadian Human Rights Act''. | |||

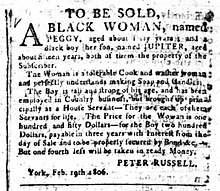

| ] | |||

| Overall, the colonial period in Canada was characterized by the systematic denial of human rights to Indigenous peoples, women, and non-white immigrants. These groups were subject to discriminatory laws and practices that denied them basic rights and freedoms. ] until it was made illegal under the ]. The imposition of European legal systems and property rights led to the ]. ] were often denied basic rights such as the right to vote and own property, while immigrants were subjected to discrimination and exploitation in the workforce.<ref name="a425">{{cite web | title=Human Rights | website=The Canadian Encyclopedia | date=Jun 6, 1944 | url=https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/human-rights | access-date=Oct 31, 2024}}</ref> | |||

| The first legal protection for human rights in Canada related to religious freedom. The ''Articles of Capitulation'' of the town of Quebec, negotiated between the French and British military commanders after the fall of Quebec in 1759, provided a guarantee of "the free exercise of the Roman religion" until the possession of Canada was determined by the British and French governments.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.42695/6?r=0&s=1|title=A collection of the acts passed in the Parliame... - Canadiana Online|website=www.canadiana.ca}}</ref> A similar guarantee was included in the ''Articles of Capitulation'' of Montreal the next year.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.42695/10?r=0&s=1|title=A collection of the acts passed in the Parliame... - Canadiana Online|website=www.canadiana.ca}}</ref> The two guarantees were formally confirmed by Britain in the '']'',<ref>.</ref> and then given statutory protection in the '']''.<ref name = QuebecAct>{{Cite web|url=https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/quebec_act_1774.asp|title=Avalon Project - Great Britain : Parliament - The Quebec Act: October 7, 1774|website=avalon.law.yale.edu}}</ref> The result was that the British subjects in Quebec had greater guarantees of religious liberty at that time than did the Roman Catholic inhabitants of Great Britain and Ireland, who would not receive similar guarantees until ] in 1829.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://members.pcug.org.au/~ppmay/acts/relief_act_1829.htm|title=THE CATHOLIC RELIEF ACT, 1829|website=members.pcug.org.au}}</ref> | |||

| At the provincial level, human rights are protected by the charter and by provincial human rights legislation. The charter applies to provincial governments and agencies, and also local governments created by provincial law, such as municipalities and school boards. Provincial human rights laws also apply to governments, and also to workplaces under provincial jurisdiction. It is estimated that 85% of workplaces are covered by provincial human rights laws. | |||

| Nearly a century later, the ] passed similar legislation, ending the ] of the ] in the province, and recognizing instead the principle of "legal equality among all religious denominations". The act provided that the "free exercise and enjoyment of religious profession and worship" was protected by the Constitution and laws of the Province.<ref>''An Act to repeal so much of the Act of the Parliament of Great Britain passed in the Thirty-first year of the Reign of King George the Third, and Chaptered Thirty-one, as relates to Rectories, and the presentation of Incumbents to the same, and for other purposes connected with such Rectories'', Statutes of the Province of Canada, 14-15 Vict. (1851), c. 175, Preamble and s. 1.</ref> | |||

| Although there is variation among the matters covered by federal, provincial and territorial, they all generally provide anti-discrimination protections concerning employment practices, housing, and the provision of goods and services generally available to the public.<ref name=":0">Gallagher-Louisy, Cathy and Jiwon Chun. "Overview of Human Rights Codes by Province and Territory in Canada." Canadian Centre for Diversity and Inclusion. January 2018.</ref> The laws prohibit discrimination on enumerated personal characteristics, such as race, sex, religion or sexual orientation. | |||

| === Confederation === | |||

| Claims under the human rights laws are of a civil nature. They are typically investigated by a human rights commission under the applicable human rights law and are adjudicated either by a human rights tribunal or by the court of first instance. The tribunal or court generally has broad remedial powers. | |||

| ==== Constitutional framework ==== | |||

| In some Canadian provinces or territories the tribunal is set forth as a board or panel. Both of which have adjudicate powers. | |||

| In 1867, ] was created by the '']'' (now named the ''Constitution Act, 1867'').<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/Const/page-1.html|title=Consolidated federal laws of canada, Access to Information Act|first=Legislative Services|last=Branch|date=July 30, 2015|website=laws-lois.justice.gc.ca}}</ref> In keeping with British constitutional traditions, the act did not include an entrenched list of rights, other than specific rights relating to language use in legislatures and courts,<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/Const/page-7.html|title=Consolidated federal laws of canada, Access to Information Act|first=Legislative Services|last=Branch|date=July 30, 2015|website=laws-lois.justice.gc.ca}}</ref> and provisions protecting the right of certain religious minorities to establish their own separate and denominational schools.<ref name="s93">{{Cite web|url=https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/Const/page-4.html|title=Consolidated federal laws of canada, Access to Information Act|first=Legislative Services|last=Branch|date=July 30, 2015|website=laws-lois.justice.gc.ca}}</ref> Canadian law instead followed the British constitutional approach in which the (unenumerated) "]" had traditionally been defended by all the branches of the government (Parliament, the courts, and the Crown) collectively and sometimes in competition with each other. However, 20th century political and legal thought also emphasized the importance of ] and property rights as important aspects of liberty and the rule of law. This approach meant that what are now viewed as human rights concerns, based on personal circumstances, would be considered of lesser importance than contractual and property rights. | |||

| == The Canadian Provincial Human Rights Commissions and Tribunals == | |||

| Human rights issues in the first seventy years of Canadian history thus tended to be raised in the framework of the constitutional ] between the federal and provincial governments. A person who was affected by a provincial law could challenge that law in the courts, arguing that it intruded on a matter reserved for the federal government. Alternatively, a person who was affected by federal law could challenge it in court, arguing that it intruded on a matter reserved for the provinces. In either case, the focus was primarily on the constitutional authority of the federal and provincial governments, not on the rights of the individual. | |||

| === Alberta Human Rights Commission === | |||

| The Alberta Human Rights Commission is an independent commission of the Government of Alberta. Their mandate is to foster equality and reduce discrimination. The AHRC provides public information and education programs, and helps Albertans resolve human rights complaints.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Alberta Human Rights Commission |date=June 21, 2023 |title=ABOUT THE COMMISSION |url=https://albertahumanrights.ab.ca/Pages/default.aspx }}</ref> | |||

| The division of powers is also the reason that the term "civil rights" is not used in Canada in the same way as it is used in other countries, such as the United States. One of the main areas of provincial jurisdiction is "Property and civil rights",<ref name="s93"/> which is a broad phrase used to encompass all of what is normally termed the ], such as contracts, property, torts/delicts, family law, wills, estates and successions and so on. This use of the phrase dates back to the ''Quebec Act, 1774''.<ref name = QuebecAct/> Given the broad, established meaning of "civil rights" in Canadian constitutional law, it has not been used in the more specific meaning of personal equality rights. Instead, the terms "human rights" / "droits de la personne" are used. | |||

| === Alberta Human Rights Tribunal === | |||

| The tribunal is the independent adjudicative arm of the Alberta Human Rights Commission. The work of the tribunal is independent from the work of the commission staff in resolving complaints. | |||

| ==== Early cases ==== | |||

| Human rights tribunals, like other administrative tribunals, are quasi-judicial. This means they have powers and procedures similar to a court of law, but it is less formal.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Alberta Human Rights Commission |date=March 12, 2021 |title=Tribunal - Human rights tribunals are quasi-judicial |url=https://albertahumanrights.ab.ca/tribunal_process/Pages/tribunal_process.aspx }}</ref> | |||

| ===== ''Union Colliery Co. v. Bryden'' (1899) ===== | |||

| === British Columbia's Office of the Human Rights Commissioner === | |||