| Revision as of 19:39, 21 October 2024 editMonkbot (talk | contribs)Bots3,695,952 editsm Task 20: replace {lang-??} templates with {langx|??} ‹See Tfd› (Replaced 5);Tag: AWB← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 18:28, 6 January 2025 edit undo104.37.208.5 (talk) →Early life and accession to powerTags: Manual revert Visual edit | ||

| (40 intermediate revisions by 34 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Ruler of Mali |

{{Short description|Ruler of Mali from c. 1312 to c. 1337}} | ||

| {{pp-pc|small=yes}} | {{pp-pc|small=yes}} | ||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=April 2022}} | {{Use dmy dates|date=April 2022}} | ||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

| | reg-type1 = | | reg-type1 = | ||

| | regent1 = | | regent1 = | ||

| | spouse = Inari |

| spouse = Inari Konte{{sfn|Bühnen|1994|p=12}} | ||

| | house = ] | | house = ] | ||

| | mother = | | mother = | ||

| | birth_date = |

| birth_date = 1280 | ||

| | birth_place = ] | | birth_place = ] | ||

| | death_date = {{Circa|1337|lk=no}} | | death_date = {{Circa|1337|lk=no}} | ||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''Mansa Musa'''{{efn|{{langx|ar|منسا موسى|Mansā Mūsā}}}} (reigned {{circa|1312|1337}}{{efn|The dates of Musa's reign are uncertain. Musa is reported to have reigned for 25 years, and different lines of evidence suggest he died either {{circa|1332}} or {{circa|1337|lk=no}}, with the 1337 date being considered more likely.{{sfn|Levtzion|1963|pp=349–350}}}}) was the ninth<ref>{{harvnb|Levtzion|1963|p=353}}</ref> '']'' of the ], which reached its territorial peak during his reign. Musa's reign is often regarded as the zenith of Mali's power and prestige, |

'''Mansa Musa'''{{efn|{{langx|ar|منسا موسى|Mansā Mūsā}}}} (reigned {{circa|1312|1337}}{{efn|The dates of Musa's reign are uncertain. Musa is reported to have reigned for 25 years, and different lines of evidence suggest he died either {{circa|1332}} or {{circa|1337|lk=no}}, with the 1337 date being considered more likely.{{sfn|Levtzion|1963|pp=349–350}}}}) was the ninth<ref>{{harvnb|Levtzion|1963|p=353}}</ref> '']'' of the ], which reached its territorial peak during his reign. Musa's reign is often regarded as the zenith of Mali's power and prestige, although he features comparatively less in ] ]s than his ]. | ||

| He was exceptionally wealthy<ref name="natgeo">{{cite web | url= https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/mansa-musa-musa-i-mali | title=Mansa Musa (Musa I of Mali) |work= ] | publisher= ] | access-date= 6 September 2022 | archive-date=19 August 2022 | archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20220819110054/https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/mansa-musa-musa-i-mali/ | url-status=live }}</ref> to an extent that he was described as being inconceivably rich by contemporaries; '']'' magazine reported: "There's really no way to put an accurate number on his wealth."<ref>{{cite magazine|url=http://time.com/money/3977798/the-10-richest-people-of-all-time/|title=The 10 Richest People of All Time|author=Davidson|first=Jacob|date=July 30, 2015|magazine=Time|access-date=5 January 2017|archive-date=24 August 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150824185817/http://time.com/money/3977798/the-10-richest-people-of-all-time/|url-status=dead}}</ref> It is known from local manuscripts and travellers' accounts that Mansa Musa's wealth came principally from the Mali Empire's control and taxing of the trade in salt from ] and especially from gold panned and mined in ] and ] to the south. Over a very long period Mali had amassed a large reserve of gold. Mali is also believed to have been involved in the trade in many goods such as ivory, ], spices, silks, and ceramics. However, presently little is known about the extent or mechanics of these trades.<ref name="natgeo" /><ref>{{cite book |last1=Rodriguez |first1=Junius P. |title=The Historical Encyclopedia of World Slavery |date=1997 |publisher=ABC-CLIO |isbn=978-0-87436-885-7 |page= 449 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ATq5_6h2AT0C&pg=RA1-PA449 |access-date=3 May 2023 |language=en}}</ref> At the time of Musa's ascension to the throne, Mali consisted largely of the territory of the former ], which Mali had conquered. The Mali Empire comprised land that is now part of ], ], ], ], and the modern state of ]. | |||

| Musa went on ] to ] in 1324, traveling with an enormous entourage and a vast supply of gold. En route |

Musa went on ] to ] in 1324, traveling with an enormous entourage and a vast supply of gold. En route he spent time in ], where his lavish gift-giving is said to have noticeably affected the value of gold in Egypt and garnered the attention of the wider Muslim world. Musa expanded the borders of the Mali Empire, in particular incorporating the cities of ] and ] into its territory. He sought closer ties with the rest of the Muslim world, particularly the ] and ]s. He recruited scholars from the wider Muslim world to travel to Mali, such as the Andalusian poet ], and helped establish Timbuktu as a center of Islamic learning. His reign is associated with numerous construction projects, including a portion of ] in Timbuktu. | ||

| ==Name and titles== | ==Name and titles== | ||

| Mansa Musa's personal name was Musa ({{langx|ar|موسى|Mūsá}}), the name of ].{{sfn|McKissack|McKissack|1994|p=56}} '']'', 'ruler'<ref>{{harvnb|Gomez|2018|p=87}}</ref> or 'king'<ref>{{harvnb|MacBrair|1873|p=40}}</ref> in ], was the title of the ruler of the Mali Empire. |

Mansa Musa's personal name was Musa ({{langx|ar|موسى|Mūsá}}), the name of ].{{sfn|McKissack|McKissack|1994|p=56}} '']'', 'ruler'<ref>{{harvnb|Gomez|2018|p=87}}</ref> or 'king'<ref>{{harvnb|MacBrair|1873|p=40}}</ref> in ], was the title of the ruler of the Mali Empire. | ||

| Al-Yafii gave Musa's name as Musa ibn Abi Bakr ibn Abi al-Aswad ({{langx|ar|موسى بن أبي بكر بن أبي الأسود|Mūsā ibn Abī Bakr ibn Abī al-Aswad}}),{{sfn|Collet|2019|p=115–116}} and ibn Hajar gave Musa's name as Musa ibn Abi Bakr Salim al-Takruri ({{langx|ar|موسى بن أبي بكر سالم التكروري|Mūsā ibn Abī Bakr Salim al-Takruri}}).{{sfn|Levtzion|Hopkins|2000|p=358}} | In oral tradition and the '']'', Musa is further known as Kanku Musa.<ref>{{harvnb|Bell|1972|p=230}}</ref>{{efn|The name is transcribed in the ''Tarikh al-Sudan'' as Kankan ({{langx|ar|كنكن|Kankan}}), which Cissoko concluded was a representation of the Mandinka woman's name Kanku{{sfn|Cissoko|1969}}}} In Mandé tradition, it was common for one's name to be prefixed by his mother's name, so the name Kanku Musa means "Musa, son of Kanku", although it is unclear whether the genealogy implied is literal.{{sfn|Gomez|2018|p=109}} Al-Yafii gave Musa's name as Musa ibn Abi Bakr ibn Abi al-Aswad ({{langx|ar|موسى بن أبي بكر بن أبي الأسود|Mūsā ibn Abī Bakr ibn Abī al-Aswad}}),{{sfn|Collet|2019|p=115–116}} and ibn Hajar gave Musa's name as Musa ibn Abi Bakr Salim al-Takruri ({{langx|ar|موسى بن أبي بكر سالم التكروري|Mūsā ibn Abī Bakr Salim al-Takruri}}).{{sfn|Levtzion|Hopkins|2000|p=358}} | ||

| In the Songhai language, rulers of Mali such as Musa were known as the Mali-koi, ''koi'' being a title that conveyed authority over a region: in other words, the "ruler of Mali".<ref>{{harvnb|Gomez|2018|pp=109,129}}</ref> | Musa is often given the title ] in oral tradition because he made ].{{sfn|Niane|1959}} In the ], rulers of Mali such as Musa were known as the Mali-koi, ''koi'' being a title that conveyed authority over a region: in other words, the "ruler of Mali".<ref>{{harvnb|Gomez|2018|pp=109,129}}</ref> | ||

| ==Historical sources== | ==Historical sources== | ||

| Much of what is known about Musa comes from Arabic sources written after his hajj, especially the writings of ] and ]. While in Cairo during his ], Musa befriended officials such as Ibn Amir Hajib, who learned about him and his country from him and later passed |

Much of what is known about Musa comes from Arabic sources written after his hajj, especially the writings of ] and ]. While in Cairo during his ], Musa befriended officials such as Ibn Amir Hajib, who learned about him and his country from him and later passed that knowledge to historians such as Al-Umari.{{sfn|Al-Umari|loc=Chapter 10}} Additional information comes from two 17th-century manuscripts written in ], the '']''{{efn|The ''Tarikh Ibn al-Mukhtar'' is a historiographical name for an untitled manuscript by Ibn al-Mukhtar. This document is also known as the ''Tarikh al-Fattash'', which Nobili and Mathee have argued is properly the title of a 19th-century document that used Ibn al-Mukhtar's text as a source.{{sfn|Nobili|Mathee|2015}}}} and the '']''.{{sfn|Gomez|2018|pp=92–93}} Oral tradition, as performed by the ''jeliw'' ({{singular}} ''jeli''), also known as ], includes relatively little information about Musa relative to some other parts of the history of Mali, with his predecessor conquerors receiving more prominence.{{sfnm|Gomez|2018|1pp=92–93|Niane|1984|2pp=147–152}} | ||

| ==Lineage |

==Lineage== | ||

| {{Lineage | {{Lineage | ||

| Line 67: | Line 67: | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| Musa's father was named Faga Leye{{sfn|Niane|1959}} and his mother may have been named Kanku.{{efn|Musa's name Kanku Musa means "Musa son of Kanku", but the genealogy may not be literal.<ref>{{harvnb|Gomez|2018|pp=109–110}}</ref>}} Faga Leye was the son of ], a brother of ], the first mansa of the Mali Empire.{{sfn|Niane|1959}} |

According to ], Musa's father was named Faga Leye{{sfn|Niane|1959}} and his mother may have been named Kanku.{{efn|Musa's name Kanku Musa means "Musa son of Kanku", but the genealogy may not be literal.<ref>{{harvnb|Gomez|2018|pp=109–110}}</ref>}} Faga Leye was the son of ], a brother of ], the first mansa of the Mali Empire.{{sfn|Niane|1959}} ] does not mention Faga Leye, referring to Musa as Musa ibn Abu Bakr. This can be interpreted as either "Musa son of Abu Bakr" or "Musa descendant of Abu Bakr." It is implausible that Abu Bakr was Musa's father, due to the amount of time between Sunjata's reign and Musa's.<ref>{{harvnb|Levtzion|1963|p=347}}</ref>{{sfn|Fauvelle|2022|p=156}} | ||

| ], who visited Mali during the reign of Musa's brother Sulayman, said that Musa's grandfather was named Sariq Jata.{{sfn|Levtzion|Hopkins|2000|p=295}} Sariq Jata may be another name for Sunjata, who was actually Musa's great-uncle.{{sfn|Levtzion|Hopkins|2000|p=416}} This, along with ]'s use of the name 'Musa ibn Abu Bakr' prompted historian Francois-Xavier Fauvelle to propose that Musa was in fact the son of ], a grandson of Sunjata through his daughter. Later attempts to erase this possibly illegitimate succession through the female line led to the confusion in the sources over Musa's parentage.{{sfn|Fauvelle|2022|p=173-4}} Hostility towards Musa's branch of the ] would also explain his relative absence from or scathing treatment by oral histories.{{sfn|Fauvelle|2022|p=185}} | |||

| ⚫ | Musa ascended to power in the early 1300s{{efn|The exact date of Musa's accession is debated. Ibn Khaldun claims Musa reigned for 25 years, so his accession is dated to 25 years before his death. Musa's death may have occurred in 1337, 1332, or possibly even earlier, giving 1307 or 1312 as plausible approximate years of accession. 1312 is the most widely accepted by modern historians.<ref name="Bell 1972">{{harvnb|Bell|1972}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Levtzion|1963|pp=349–350}}</ref>}} under unclear circumstances. According to Musa's own account, his predecessor as Mansa of Mali, presumably ],<ref>{{harvnb|Fauvelle|2018}}</ref> launched ] to explore the ] (200 ships for the first exploratory mission and 2,000 ships for the second). The Mansa led the second expedition himself |

||

| ==Early life and accession to power== | |||

| According to the '']'', Musa had a wife named Inari Konte.{{sfn|Bühnen|1994|p=12}} Her ''jamu'' (clan name) Konte is shared with both Sunjata's mother Sogolon Konte and his arch-enemy ]. {{sfn|Bühnen|1994|p=12–13}} | |||

| The date of Musa's birth is unknown, but he appears to have been a young man in 1324.{{sfn|Gomez|2018|p=104}} The ''Tarikh al-fattash'' claims that Musa accidentally killed Kanku at some point prior to his hajj.{{sfn|Gomez|2018|p=109}} | |||

| ⚫ | Musa ascended to power in the early 1300s{{efn|The exact date of Musa's accession is debated. Ibn Khaldun claims Musa reigned for 25 years, so his accession is dated to 25 years before his death. Musa's death may have occurred in 1337, 1332, or possibly even earlier, giving 1307 or 1312 as plausible approximate years of accession. 1312 is the most widely accepted by modern historians.<ref name="Bell 1972">{{harvnb|Bell|1972}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Levtzion|1963|pp=349–350}}</ref>}} under unclear circumstances. According to Musa's own account, his predecessor as Mansa of Mali, presumably ],<ref>{{harvnb|Fauvelle|2018}}</ref> launched ] to explore the ] (200 ships for the first exploratory mission and 2,000 ships for the second). The Mansa led the second expedition himself and appointed Musa as his deputy to rule the empire until he returned.<ref>{{harvnb|Al-Umari|loc=Chapter 10}}</ref> When he did not return, Musa was crowned as mansa himself, marking a transfer of the line of succession from the descendants of Sunjata to the descendants of his brother Abu Bakr.<ref>{{harvnb|Ibn Khaldun}}</ref> Some modern historians have cast doubt on Musa's version of events, suggesting he may have deposed his predecessor and devised the story about the voyage to explain how he took power.<ref>{{harvnb|Gomez|2018}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Thornton|2012|pp=9,11}}</ref> Nonetheless, the possibility of such a voyage has been taken seriously by several historians.{{sfn|Gomez|2018|p=101}}{{sfn|Devisse|Labib|1984|p=666}}{{sfn|Thornton|2012|p=13}} | ||

| ==Early reign== | ==Early reign== | ||

| Line 81: | Line 84: | ||

| Musa was a ], and his ], or pilgrimage to ], made him well known across ] and the ]. To Musa, Islam was "an entry into the cultured world of the Eastern Mediterranean".<ref name=Goodwin110>{{harvnb|Goodwin|1957|p=110}}.</ref> He would have spent much time fostering the growth of the religion within his empire. When Musa departed Mali for the Hajj, he left his son Muhammad to rule in his absence.<ref>{{harvnb|Al-Umari}}, translated in {{harvnb|Levtzion|Hopkins|2000|p=268}}</ref> | Musa was a ], and his ], or pilgrimage to ], made him well known across ] and the ]. To Musa, Islam was "an entry into the cultured world of the Eastern Mediterranean".<ref name=Goodwin110>{{harvnb|Goodwin|1957|p=110}}.</ref> He would have spent much time fostering the growth of the religion within his empire. When Musa departed Mali for the Hajj, he left his son Muhammad to rule in his absence.<ref>{{harvnb|Al-Umari}}, translated in {{harvnb|Levtzion|Hopkins|2000|p=268}}</ref> | ||

| Musa made his pilgrimage between 1324 and 1325, spanning 2700 miles.{{sfn|Gomez|2018|p=4}}<ref>{{Cite book|title = Worlds Together Worlds Apart|last = Pollard|first = Elizabeth|publisher = W.W. Norton Company Inc|year = 2015|isbn = 978-0-393-91847-2|location = New York |page = 362}}</ref><ref name= Bakewell>{{cite book|last1= Wilks| first1= Ivor| chapter= Wangara, Akan, and Portuguese in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries|editor1-last= Bakewell |editor1-first= Peter John|title=Mines of Silver and Gold in the Americas| date= 1997| publisher= Variorum, Ashgate Publishing Limited |location= Aldershot| page= 7| isbn= 9780860785132}}</ref> His procession reportedly included |

Musa made his pilgrimage between 1324 and 1325, spanning 2700 miles.{{sfn|Gomez|2018|p=4}}<ref>{{Cite book|title = Worlds Together Worlds Apart|last = Pollard|first = Elizabeth|publisher = W.W. Norton Company Inc|year = 2015|isbn = 978-0-393-91847-2|location = New York |page = 362}}</ref><ref name= Bakewell>{{cite book|last1= Wilks| first1= Ivor| chapter= Wangara, Akan, and Portuguese in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries|editor1-last= Bakewell |editor1-first= Peter John|title=Mines of Silver and Gold in the Americas| date= 1997| publisher= Variorum, Ashgate Publishing Limited |location= Aldershot| page= 7| isbn= 9780860785132}}</ref> His procession reportedly included upwards of 12,000 ]s, all wearing ] and Yemeni silk{{sfn|Cuoq|1985|p=347}} and each carrying {{convert|4|lb|abbr=on|order=flip}} of gold bars, with heralds dressed in silks bearing gold staffs organizing horses and handling bags.{{cn|date=November 2024}} | ||

| Musa provided all necessities for the procession, feeding the entire company of men and animals.<ref name=Goodwin110 /> Those animals included 80 ]s, which each carried {{convert|50|–|300|lb|abbr=on|order=flip}} of gold dust. Musa gave the gold to the poor he met along his route. Musa not only gave to the cities he passed on the way to Mecca, including ] and ], but also traded gold for souvenirs. It was reported that he built a ] every Friday.<ref name="Bell 1972"/> ], who visited Cairo shortly after Musa's pilgrimage to Mecca, noted that it was "a lavish display of power, wealth, and unprecedented by its size and pageantry".<ref>The Royal Kingdoms of Ghana, Mali, and Songhay: Life in Medieval Africa By Patricia McKissack, Fredrick McKissack Page 60</ref> Musa made a major point of showing off his nation's wealth. | Musa provided all necessities for the procession, feeding the entire company of men and animals.<ref name=Goodwin110 /> Those animals included 80 ]s, which each carried {{convert|50|–|300|lb|abbr=on|order=flip}} of gold dust. Musa gave the gold to the poor he met along his route. Musa not only gave to the cities he passed on the way to Mecca, including ] and ], but also traded gold for souvenirs. It was reported that he built a ] every Friday.<ref name="Bell 1972"/> ], who visited Cairo shortly after Musa's pilgrimage to Mecca, noted that it was "a lavish display of power, wealth, and unprecedented by its size and pageantry".<ref>The Royal Kingdoms of Ghana, Mali, and Songhay: Life in Medieval Africa By Patricia McKissack, Fredrick McKissack Page 60</ref> Musa made a major point of showing off his nation's wealth. | ||

| Musa and his entourage arrived at the outskirts of Cairo in July 1324. They camped for three days by the ] before crossing the Nile into Cairo on 19 July.{{efn|26 Rajab 724}}{{sfn|Levtzion|Hopkins|2000|p=355}}{{sfn|Gomez|2018|pp=114,117}} While in Cairo, Musa met with the ] ], whose reign had already seen one ''mansa'', ], make the Hajj. Al-Nasir expected Musa to prostrate himself before him, which Musa initially refused to do. When |

Musa and his entourage arrived at the outskirts of Cairo in July 1324. They camped for three days by the ] before crossing the Nile into Cairo on 19 July.{{efn|26 Rajab 724}}{{sfn|Levtzion|Hopkins|2000|p=355}}{{sfn|Gomez|2018|pp=114,117}} While in Cairo, Musa met with the ] ], whose reign had already seen one ''mansa'', ], make the Hajj. Al-Nasir expected Musa to prostrate himself before him, which Musa initially refused to do. When Musa did finally bow he said he was doing so for God alone.{{sfn|Gomez|2018|p=116}} | ||

| Despite this initial awkwardness, the two rulers got along well and exchanged gifts. Musa and his entourage gave and spent freely while in Cairo. Musa stayed in the ] of Cairo and befriended its governor, ibn Amir Hajib, who learned much about Mali from him. Musa stayed in Cairo for three months, departing on 18 October{{efn|28 Shawwal}} with the official caravan to Mecca.{{sfn|Levtzion|Hopkins|2000|p=355}}{{sfn|Collet|2019|p=111}} | Despite this initial awkwardness, the two rulers got along well and exchanged gifts. Musa and his entourage gave and spent freely while in Cairo. Musa stayed in the ] of Cairo and befriended its governor, ibn Amir Hajib, who learned much about Mali from him. Musa stayed in Cairo for three months, departing on 18 October{{efn|28 Shawwal}} with the official caravan to Mecca.{{sfn|Levtzion|Hopkins|2000|p=355}}{{sfn|Collet|2019|p=111}} | ||

| Line 91: | Line 94: | ||

| Musa's generosity continued as he traveled onward to Mecca, and he gave gifts to fellow pilgrims and the people of ] and Mecca. While in Mecca, conflict broke out between a group of Malian pilgrims and a group of Turkic pilgrims in the ]. Swords were drawn, but before the situation escalated further, Musa persuaded his men to back down.{{sfn|Collet|2019|pp=115–122}} | Musa's generosity continued as he traveled onward to Mecca, and he gave gifts to fellow pilgrims and the people of ] and Mecca. While in Mecca, conflict broke out between a group of Malian pilgrims and a group of Turkic pilgrims in the ]. Swords were drawn, but before the situation escalated further, Musa persuaded his men to back down.{{sfn|Collet|2019|pp=115–122}} | ||

| Musa and his entourage lingered in Mecca after the last day of the Hajj. Traveling separately from the main caravan, their return journey to Cairo was struck by catastrophe. By the time they reached ], many of the Malian pilgrims had died of cold, starvation, or bandit raids, and they had lost |

Musa and his entourage lingered in Mecca after the last day of the Hajj. Traveling separately from the main caravan, their return journey to Cairo was struck by catastrophe. By the time they reached ], many of the Malian pilgrims had died of cold, starvation, or bandit raids, and they had lost much of their supplies.{{sfn|Gomez|2018|p=118}}{{sfn|Collet|2019|pp=122–129}} Having run out of money, Musa and his entourage were forced to borrow money and resell much of what they had purchased while in Cairo before the Hajj, and Musa went into debt to several merchants such as Siraj al-Din. However, Al-Nasir Muhammad returned Musa's earlier show of generosity with gifts of his own.{{sfn|Gomez|2018|pp=118–120}} | ||

| On his return journey, Musa met the ] poet ], whose eloquence and knowledge of jurisprudence impressed him, and whom he convinced to travel with him to Mali.{{sfn|Hunwick|1990|pp=60–61}} Other scholars Musa brought to Mali included ].<ref>{{harvnb|Al-Umari}}, translated in {{harvnb|Levtzion|Hopkins|2000|p=261}}</ref> | On his return journey, Musa met the ] poet ], whose eloquence and knowledge of jurisprudence impressed him, and whom he convinced to travel with him to Mali.{{sfn|Hunwick|1990|pp=60–61}} Other scholars Musa brought to Mali included ].<ref>{{harvnb|Al-Umari}}, translated in {{harvnb|Levtzion|Hopkins|2000|p=261}}</ref> | ||

| According to the '']'', the cities of ] and ] submitted to Musa's rule as he traveled through on his return to Mali.<ref>{{harvnb|al-Sadi}}, translated in {{harvnb|Hunwick|1999|p=10}}</ref> According to one account given by ], Musa's general Saghmanja conquered Gao. The other account claims that Gao had been conquered during the reign of ].<ref>{{harvnb|Ibn Khaldun}}, translated in {{harvnb|Levtzion|Hopkins|2000|p=334}}</ref> |

According to the '']'', the cities of ] and ] submitted to Musa's rule as he traveled through on his return to Mali.<ref>{{harvnb|al-Sadi}}, translated in {{harvnb|Hunwick|1999|p=10}}</ref> It is unlikely, however, that a group of pilgrims, even if armed, would have been able to conquer a wealthy and powerful city.{{sfn|Fauvelle|2022|p=79}} According to one account given by ], Musa's general Saghmanja conquered Gao. The other account claims that Gao had been conquered during the reign of ].<ref>{{harvnb|Ibn Khaldun}}, translated in {{harvnb|Levtzion|Hopkins|2000|p=334}}</ref> Mali's control of Gao may have been weak, requiring powerful mansas to reassert their authority periodically,{{sfn|Levtzion|1973|p=75}} or it might simply be an error on the part of al-Sadi, author of the ''Tarikh''.{{sfn|Fauvelle|2022|p=79}} | ||

| ==Later reign== | ==Later reign== | ||

| Line 102: | Line 105: | ||

| Musa embarked on a large building program, raising ] and ] in Timbuktu and ]. Most notably, the ancient center of learning ] (or University of Sankore) was constructed during his reign.<ref>{{cite web | url=https://muslimheritage.com/the-university-of-sankore-timbuktu/ | title=The University of Sankore, Timbuktu | date=7 June 2003 }}</ref> | Musa embarked on a large building program, raising ] and ] in Timbuktu and ]. Most notably, the ancient center of learning ] (or University of Sankore) was constructed during his reign.<ref>{{cite web | url=https://muslimheritage.com/the-university-of-sankore-timbuktu/ | title=The University of Sankore, Timbuktu | date=7 June 2003 }}</ref> | ||

| In Niani, Musa built the Hall of Audience, a building communicating by an interior door to the royal palace. It was "an admirable Monument", surmounted by a dome and adorned with ]s of striking colours. The wooden window frames of an upper storey were plated with silver foil; those of a lower storey with gold. Like the Great Mosque, a contemporaneous and grandiose structure in Timbuktu, the Hall was built of cut stone. | In Niani, Musa built the Hall of Audience, a building communicating by an interior door to the royal palace. It was "an admirable Monument", surmounted by a dome and adorned with ]s of striking colours. The wooden window frames of an upper storey were plated with silver foil; those of a lower storey with gold. Like the Great Mosque, a contemporaneous and grandiose structure in Timbuktu, the Hall was built of cut stone.{{cn|date=November 2024}} | ||

| During this period, there was an advanced level of urban living in the major centers of Mali. Sergio Domian, an Italian scholar of art and architecture, wrote of this period: "Thus was laid the foundation of an urban civilization. At the height of its power, Mali had at least 400 cities, and the interior of the ] was very densely populated."<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.africanholocaust.net/africanlegends.htm#mansa|title=Mansa Musa |publisher=African History Restored|year=2008|access-date=29 September 2008| archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20081002094536/http://www.africanholocaust.net/africanlegends.htm#mansa|archive-date=2 October 2008|url-status=live}}</ref> | During this period, there was an advanced level of urban living in the major centers of Mali. Sergio Domian, an Italian scholar of art and architecture, wrote of this period: "Thus was laid the foundation of an urban civilization. At the height of its power, Mali had at least 400 cities, and the interior of the ] was very densely populated."<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.africanholocaust.net/africanlegends.htm#mansa|title=Mansa Musa |publisher=African History Restored|year=2008|access-date=29 September 2008| archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20081002094536/http://www.africanholocaust.net/africanlegends.htm#mansa|archive-date=2 October 2008|url-status=live}}</ref>{{better source needed|date=November 2024}} | ||

| ===Economy and education=== | ===Economy and education=== | ||

| Line 130: | Line 133: | ||

| ===Wealth=== | ===Wealth=== | ||

| Mansa Musa is renowned for his wealth and generosity. Online articles in the 21st century have claimed that Mansa Musa was the richest person of all time.{{sfn|Collet|2019|p=106}} {{citation needed|date=January 2024}} Historians such as Hadrien Collet have argued that Musa's wealth is impossible to |

Mansa Musa is renowned for his wealth and generosity. Online articles in the 21st century have claimed that Mansa Musa was the richest person of all time.{{sfn|Collet|2019|p=106}} {{citation needed|date=January 2024}} Historians such as Hadrien Collet have argued that Musa's wealth is impossible to calculate accurately.{{sfn|Collet|2019|p=106}}{{sfn|Mohamud|2019}} Contemporary Arabic sources may have been trying to express that Musa had more gold than they thought possible, rather than trying to give an exact number.{{sfn|Davidson|2015b}} Further, it is difficult meaningfully to compare the wealth of historical figures such as Mansa Musa, due both to the difficulty of separating the personal wealth of a monarch from the wealth of the state and to the difficulty of comparing wealth across highly different societies.{{sfn|Davidson|2015a}} Musa may have taken as much as 18 tons of gold on his hajj,{{sfn|Gomez|2018|p=106}} equal in value to over US$1.397 billion in 2024.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://ycharts.com/indicators/gold_price_in_us_dollar|title=Gold Price in US Dollars (USD/oz t)|access-date=24 January 2022|website=YCharts|archive-date=24 January 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220124150156/https://ycharts.com/indicators/gold_price_in_us_dollar|url-status=live}}</ref> Musa himself further promoted the appearance of having vast, inexhaustible wealth by spreading rumors that gold grew like a plant in his kingdom.{{sfn|Gomez|2018|p=121}} | ||

| According to some Arabic writers, Musa's gift-giving caused a depreciation in the value of gold in Egypt. Al-Umari said that before Musa's arrival |

According to some Arabic writers, Musa's gift-giving caused a depreciation in the value of gold in Egypt. Al-Umari said that before Musa's arrival a '']'' of gold was worth 25 silver '']'', but that it dropped to less than 22 ''dirhams'' afterward and did not go above that number for at least twelve years.{{sfn|Levtzion|Hopkins|2000|p=271}} Though this has been described as having "wrecked" Egypt's economy,{{sfn|Mohamud|2019}} the historian Warren Schultz has argued that this was well within normal fluctuations in the value of gold in Mamluk Egypt.{{sfn|Schultz|2006}} | ||

| The wealth of the Mali Empire did not come from direct control of gold-producing regions, but rather trade and tribute.{{sfn|Gomez|2018|pp=107–108}} The gold Musa brought on his pilgrimage probably represented years of accumulated tribute that Musa would have spent much of his early reign gathering.{{sfn|Gomez|2018|p=105}} Another source of income for Mali during Musa's reign was taxation of the copper trade.{{sfn|Levtzion|Hopkins|2000|p=272}} | The wealth of the Mali Empire did not come from direct control of gold-producing regions, but rather trade and tribute.{{sfn|Gomez|2018|pp=107–108}} The gold Musa brought on his pilgrimage probably represented years of accumulated tribute that Musa would have spent much of his early reign gathering.{{sfn|Gomez|2018|p=105}} Another source of income for Mali during Musa's reign was taxation of the copper trade.{{sfn|Levtzion|Hopkins|2000|p=272}} | ||

| Line 151: | Line 154: | ||

| {{refbegin|indent=yes}} | {{refbegin|indent=yes}} | ||

| *{{citation | author = Al-Umari | author-link = Ibn Fadlallah al-Umari | title = Masalik al-Absar fi Mamalik al-Amsar }}, translated in {{harvnb|Levtzion|Hopkins|2000}} | *{{citation | author = Al-Umari | author-link = Ibn Fadlallah al-Umari | title = Masalik al-Absar fi Mamalik al-Amsar }}, translated in {{harvnb|Levtzion|Hopkins|2000}} | ||

| ⚫ | * {{citation | author = Ibn Khaldun | author-link = Ibn Khaldun | title = Kitāb al-ʿIbar wa-dīwān al-mubtadaʾ wa-l-khabar fī ayyām al-ʿarab wa-ʾl-ʿajam wa-ʾl-barbar }}, translated in {{harvnb|Levtzion|Hopkins|2000}} | ||

| *{{citation | author = al-Sadi | title = Taʾrīkh al-Sūdān }}, translated in {{harvnb|Hunwick|1999}} | *{{citation | author = al-Sadi | title = Taʾrīkh al-Sūdān }}, translated in {{harvnb|Hunwick|1999}} | ||

| {{refend}} | {{refend}} | ||

| * {{cite book |editor1-last=Cuoq |editor1-first=Joseph |title=Recueil des sources arabes concernant l'Afrique occidentale du VIIIeme au XVIeme siècle (Bilād Al-Sūdān) |date=1985 |publisher=Éditions du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique |location=Paris |url=https://www.persee.fr/doc/sohim_0398-3811_1985_edc_7_1}} | |||

| ⚫ | * {{citation | author = Ibn Khaldun | author-link = Ibn Khaldun | title = Kitāb al-ʿIbar wa-dīwān al-mubtadaʾ wa-l-khabar fī ayyām al-ʿarab wa-ʾl-ʿajam wa-ʾl-barbar }}, translated in {{harvnb|Levtzion|Hopkins|2000}} | ||

| ===Other sources=== | ===Other sources=== | ||

| Line 168: | Line 172: | ||

| *{{cite book |last1=Devisse |first1=Jean |last2=Labib |first2=S. |date=1984 |chapter=Africa in inter-continental relations |editor-last=Niane |editor-first=D.T. |title=General History of Africa, IV: Africa From the Twelfth to the Sixteenth Century |location=Berkeley California |publisher=University of California |pages=635–672 |isbn=0-520-03915-7 |chapter-url=https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000060349 |access-date=25 April 2022 |archive-date=25 April 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220425142605/https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000060349 |url-status=live }} | *{{cite book |last1=Devisse |first1=Jean |last2=Labib |first2=S. |date=1984 |chapter=Africa in inter-continental relations |editor-last=Niane |editor-first=D.T. |title=General History of Africa, IV: Africa From the Twelfth to the Sixteenth Century |location=Berkeley California |publisher=University of California |pages=635–672 |isbn=0-520-03915-7 |chapter-url=https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000060349 |access-date=25 April 2022 |archive-date=25 April 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220425142605/https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000060349 |url-status=live }} | ||

| *{{Cite book |publisher= Princeton University Press |isbn=978-0-691-18126-4 |last=Fauvelle |first=François-Xavier |others=Troy Tice (trans.) |title=The Golden Rhinoceros: Histories of the African Middle Ages |date=2018 |orig-year=2013 |chapter=The Sultan and the Sea}} | *{{Cite book |publisher= Princeton University Press |isbn=978-0-691-18126-4 |last=Fauvelle |first=François-Xavier |others=Troy Tice (trans.) |title=The Golden Rhinoceros: Histories of the African Middle Ages |date=2018 |orig-year=2013 |chapter=The Sultan and the Sea}} | ||

| *{{cite book |last1=Fauvelle |first1=Francois-Xavier |title=Les masques et la mosquée - L’empire du Mâli XIIIe XIVe siècle |date=2022 |publisher=CNRS Editions |location=Paris |isbn=2271143713}} | |||

| * {{cite book |first1=Michael A. |last1=Gomez |title=African Dominion: A New History of Empire in Early and Medieval West Africa |year=2018 |isbn= 9780691196824 |publisher=Princeton University Press|title-link=African Dominion}} | * {{cite book |first1=Michael A. |last1=Gomez |title=African Dominion: A New History of Empire in Early and Medieval West Africa |year=2018 |isbn= 9780691196824 |publisher=Princeton University Press|title-link=African Dominion}} | ||

| * {{cite journal |last=Goodwin |first=A. J .H. |year=1957 |title=The Medieval Empire of Ghana |journal=] |volume=12 |issue=47 |pages=108–112 |doi=10.2307/3886971 |jstor=3886971}} | * {{cite journal |last=Goodwin |first=A. J .H. |year=1957 |title=The Medieval Empire of Ghana |journal=] |volume=12 |issue=47 |pages=108–112 |doi=10.2307/3886971 |jstor=3886971}} | ||

| *{{cite book |first1=Said |last1=Hamdun |first2=Noël Q. |last2=King |title=Ibn Battuta in Black Africa |publisher=Markus Wiener |year=2009 |orig-year=1975 |location=Princeton |isbn=978-1-55876-336-4}} | *{{cite book |first1=Said |last1=Hamdun |first2=Noël Q. |last2=King |title=Ibn Battuta in Black Africa |publisher=Markus Wiener |year=2009 |orig-year=1975 |location=Princeton |isbn=978-1-55876-336-4}} | ||

| * {{cite news |accessdate=29 September 2018 |title=The Big Secret of Celebrity Wealth (Is That No One Knows Anything) |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/19/style/richest-celebrities-in-hollywood.html |last=Harris |first=Malcolm |date=19 September 2018 |newspaper=The New York Times |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180927081208/https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/19/style/richest-celebrities-in-hollywood.html |archive-date=27 September 2018 |url-status=live |url-access=limited }} | |||

| * {{Cite journal |volume=36 |pages=59–66 |last=Hunwick |first=J. O. |title=An Andalusian in Mali: a contribution to the biography of Abū Ishāq al-Sāhilī, c. 1290–1346 |journal=Paideuma |date=1990 |jstor=40732660}} | * {{Cite journal |volume=36 |pages=59–66 |last=Hunwick |first=J. O. |title=An Andalusian in Mali: a contribution to the biography of Abū Ishāq al-Sāhilī, c. 1290–1346 |journal=Paideuma |date=1990 |jstor=40732660}} | ||

| * {{cite book |last=Hunwick |first=John O. |author-link=John Hunwick |title=Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire: Al-Sadi's Tarikh al-Sudan down to 1613 and other contemporary documents |publisher=Brill |place=Leiden |year=1999 |isbn=90-04-11207-3}} | * {{cite book |last=Hunwick |first=John O. |author-link=John Hunwick |title=Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire: Al-Sadi's Tarikh al-Sudan down to 1613 and other contemporary documents |publisher=Brill |place=Leiden |year=1999 |isbn=90-04-11207-3}} | ||

Latest revision as of 18:28, 6 January 2025

Ruler of Mali from c. 1312 to c. 1337

| Musa I | |

|---|---|

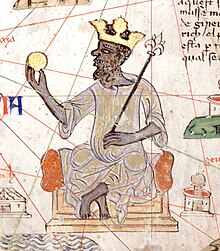

Depiction of Mansa Musa, ruler of the Mali Empire in the 14th century, from the 1375 Catalan Atlas. The label reads: This Black Lord is called Musse Melly and is the sovereign of the land of the black people of Gineva (Ghana). This king is the richest and noblest of all these lands due to the abundance of gold that is extracted from his lands. Depiction of Mansa Musa, ruler of the Mali Empire in the 14th century, from the 1375 Catalan Atlas. The label reads: This Black Lord is called Musse Melly and is the sovereign of the land of the black people of Gineva (Ghana). This king is the richest and noblest of all these lands due to the abundance of gold that is extracted from his lands. | |

| Mansa of Mali | |

| Reign | c. 1312 – c. 1337 (approx. 25 years) |

| Predecessor | Muhammad |

| Successor | Magha |

| Born | 1280 Mali Empire |

| Died | c. 1337 Mali Empire |

| Spouse | Inari Konte |

| House | Keita dynasty |

| Religion | Islam Maliki |

Mansa Musa (reigned c. 1312 – c. 1337) was the ninth Mansa of the Mali Empire, which reached its territorial peak during his reign. Musa's reign is often regarded as the zenith of Mali's power and prestige, although he features comparatively less in Mandinka oral traditions than his predecessors.

He was exceptionally wealthy to an extent that he was described as being inconceivably rich by contemporaries; Time magazine reported: "There's really no way to put an accurate number on his wealth." It is known from local manuscripts and travellers' accounts that Mansa Musa's wealth came principally from the Mali Empire's control and taxing of the trade in salt from northern regions and especially from gold panned and mined in Bambuk and Bure to the south. Over a very long period Mali had amassed a large reserve of gold. Mali is also believed to have been involved in the trade in many goods such as ivory, slaves, spices, silks, and ceramics. However, presently little is known about the extent or mechanics of these trades. At the time of Musa's ascension to the throne, Mali consisted largely of the territory of the former Ghana Empire, which Mali had conquered. The Mali Empire comprised land that is now part of Guinea, Senegal, Mauritania, the Gambia, and the modern state of Mali.

Musa went on Hajj to Mecca in 1324, traveling with an enormous entourage and a vast supply of gold. En route he spent time in Cairo, where his lavish gift-giving is said to have noticeably affected the value of gold in Egypt and garnered the attention of the wider Muslim world. Musa expanded the borders of the Mali Empire, in particular incorporating the cities of Gao and Timbuktu into its territory. He sought closer ties with the rest of the Muslim world, particularly the Mamluk and Marinid Sultanates. He recruited scholars from the wider Muslim world to travel to Mali, such as the Andalusian poet Abu Ishaq al-Sahili, and helped establish Timbuktu as a center of Islamic learning. His reign is associated with numerous construction projects, including a portion of Djinguereber Mosque in Timbuktu.

Name and titles

Mansa Musa's personal name was Musa (Arabic: موسى, romanized: Mūsá), the name of Moses in Islam. Mansa, 'ruler' or 'king' in Mandé, was the title of the ruler of the Mali Empire.

In oral tradition and the Timbuktu Chronicles, Musa is further known as Kanku Musa. In Mandé tradition, it was common for one's name to be prefixed by his mother's name, so the name Kanku Musa means "Musa, son of Kanku", although it is unclear whether the genealogy implied is literal. Al-Yafii gave Musa's name as Musa ibn Abi Bakr ibn Abi al-Aswad (Arabic: موسى بن أبي بكر بن أبي الأسود, romanized: Mūsā ibn Abī Bakr ibn Abī al-Aswad), and ibn Hajar gave Musa's name as Musa ibn Abi Bakr Salim al-Takruri (Arabic: موسى بن أبي بكر سالم التكروري, romanized: Mūsā ibn Abī Bakr Salim al-Takruri).

Musa is often given the title Hajji in oral tradition because he made hajj. In the Songhai language, rulers of Mali such as Musa were known as the Mali-koi, koi being a title that conveyed authority over a region: in other words, the "ruler of Mali".

Historical sources

Much of what is known about Musa comes from Arabic sources written after his hajj, especially the writings of Al-Umari and Ibn Khaldun. While in Cairo during his hajj, Musa befriended officials such as Ibn Amir Hajib, who learned about him and his country from him and later passed that knowledge to historians such as Al-Umari. Additional information comes from two 17th-century manuscripts written in Timbuktu, the Tarikh Ibn al-Mukhtar and the Tarikh al-Sudan. Oral tradition, as performed by the jeliw (sg. jeli), also known as griots, includes relatively little information about Musa relative to some other parts of the history of Mali, with his predecessor conquerors receiving more prominence.

Lineage

| Nare Maghan | |||||

| 1. Sunjata | Abu Bakr | ||||

| 2. Uli | Faga Leye | ||||

| 7. Qu | 9. Musa I | 11. Sulayman | |||

| 8. Muhammad | 10. Magha I | 12. Qanba | |||

| 13. Mari Jata II | |||||

| 14. Musa II | 15. Magha II | ||||

Genealogy of the mansas of the Mali Empire up to Magha II (d. c. 1389), based on Levtzion's interpretation of Ibn Khaldun. Numbered individuals reigned as mansa; the numbers indicate the order in which they reigned.

According to Djibril Tamsir Niane, Musa's father was named Faga Leye and his mother may have been named Kanku. Faga Leye was the son of Abu Bakr, a brother of Sunjata, the first mansa of the Mali Empire. Ibn Khaldun does not mention Faga Leye, referring to Musa as Musa ibn Abu Bakr. This can be interpreted as either "Musa son of Abu Bakr" or "Musa descendant of Abu Bakr." It is implausible that Abu Bakr was Musa's father, due to the amount of time between Sunjata's reign and Musa's.

Ibn Battuta, who visited Mali during the reign of Musa's brother Sulayman, said that Musa's grandfather was named Sariq Jata. Sariq Jata may be another name for Sunjata, who was actually Musa's great-uncle. This, along with Ibn Khaldun's use of the name 'Musa ibn Abu Bakr' prompted historian Francois-Xavier Fauvelle to propose that Musa was in fact the son of Abu Bakr I, a grandson of Sunjata through his daughter. Later attempts to erase this possibly illegitimate succession through the female line led to the confusion in the sources over Musa's parentage. Hostility towards Musa's branch of the Keita dynasty would also explain his relative absence from or scathing treatment by oral histories.

Early life and accession to power

The date of Musa's birth is unknown, but he appears to have been a young man in 1324. The Tarikh al-fattash claims that Musa accidentally killed Kanku at some point prior to his hajj.

Musa ascended to power in the early 1300s under unclear circumstances. According to Musa's own account, his predecessor as Mansa of Mali, presumably Muhammad ibn Qu, launched two expeditions to explore the Atlantic Ocean (200 ships for the first exploratory mission and 2,000 ships for the second). The Mansa led the second expedition himself and appointed Musa as his deputy to rule the empire until he returned. When he did not return, Musa was crowned as mansa himself, marking a transfer of the line of succession from the descendants of Sunjata to the descendants of his brother Abu Bakr. Some modern historians have cast doubt on Musa's version of events, suggesting he may have deposed his predecessor and devised the story about the voyage to explain how he took power. Nonetheless, the possibility of such a voyage has been taken seriously by several historians.

Early reign

Musa was a young man when he became Mansa, possibly in his early twenties. Given the grandeur of his subsequent hajj, it is likely that Musa spent much of his early reign preparing for it. Among these preparations would likely have been raids to capture and enslave people from neighboring lands, as Musa's entourage would include many thousands of slaves; the historian Michael Gomez estimates that Mali may have captured over 6,000 slaves per year for this purpose. Perhaps because of this, Musa's early reign was spent in continuous military conflict with neighboring non-Muslim societies. In 1324, while in Cairo, Musa said that he had conquered 24 cities and their surrounding districts.

Pilgrimage to Mecca

Musa was a Muslim, and his hajj, or pilgrimage to Mecca, made him well known across North Africa and the Middle East. To Musa, Islam was "an entry into the cultured world of the Eastern Mediterranean". He would have spent much time fostering the growth of the religion within his empire. When Musa departed Mali for the Hajj, he left his son Muhammad to rule in his absence.

Musa made his pilgrimage between 1324 and 1325, spanning 2700 miles. His procession reportedly included upwards of 12,000 slaves, all wearing brocade and Yemeni silk and each carrying 1.8 kg (4 lb) of gold bars, with heralds dressed in silks bearing gold staffs organizing horses and handling bags.

Musa provided all necessities for the procession, feeding the entire company of men and animals. Those animals included 80 camels, which each carried 23–136 kg (50–300 lb) of gold dust. Musa gave the gold to the poor he met along his route. Musa not only gave to the cities he passed on the way to Mecca, including Cairo and Medina, but also traded gold for souvenirs. It was reported that he built a mosque every Friday. Shihab al-Din al-'Umari, who visited Cairo shortly after Musa's pilgrimage to Mecca, noted that it was "a lavish display of power, wealth, and unprecedented by its size and pageantry". Musa made a major point of showing off his nation's wealth.

Musa and his entourage arrived at the outskirts of Cairo in July 1324. They camped for three days by the Pyramids of Giza before crossing the Nile into Cairo on 19 July. While in Cairo, Musa met with the Mamluk sultan al-Nasir Muhammad, whose reign had already seen one mansa, Sakura, make the Hajj. Al-Nasir expected Musa to prostrate himself before him, which Musa initially refused to do. When Musa did finally bow he said he was doing so for God alone.

Despite this initial awkwardness, the two rulers got along well and exchanged gifts. Musa and his entourage gave and spent freely while in Cairo. Musa stayed in the Qarafa district of Cairo and befriended its governor, ibn Amir Hajib, who learned much about Mali from him. Musa stayed in Cairo for three months, departing on 18 October with the official caravan to Mecca.

Musa's generosity continued as he traveled onward to Mecca, and he gave gifts to fellow pilgrims and the people of Medina and Mecca. While in Mecca, conflict broke out between a group of Malian pilgrims and a group of Turkic pilgrims in the Masjid al-Haram. Swords were drawn, but before the situation escalated further, Musa persuaded his men to back down.

Musa and his entourage lingered in Mecca after the last day of the Hajj. Traveling separately from the main caravan, their return journey to Cairo was struck by catastrophe. By the time they reached Suez, many of the Malian pilgrims had died of cold, starvation, or bandit raids, and they had lost much of their supplies. Having run out of money, Musa and his entourage were forced to borrow money and resell much of what they had purchased while in Cairo before the Hajj, and Musa went into debt to several merchants such as Siraj al-Din. However, Al-Nasir Muhammad returned Musa's earlier show of generosity with gifts of his own.

On his return journey, Musa met the Andalusi poet Abu Ishaq al-Sahili, whose eloquence and knowledge of jurisprudence impressed him, and whom he convinced to travel with him to Mali. Other scholars Musa brought to Mali included Maliki jurists.

According to the Tarikh al-Sudan, the cities of Gao and Timbuktu submitted to Musa's rule as he traveled through on his return to Mali. It is unlikely, however, that a group of pilgrims, even if armed, would have been able to conquer a wealthy and powerful city. According to one account given by ibn Khaldun, Musa's general Saghmanja conquered Gao. The other account claims that Gao had been conquered during the reign of Mansa Sakura. Mali's control of Gao may have been weak, requiring powerful mansas to reassert their authority periodically, or it might simply be an error on the part of al-Sadi, author of the Tarikh.

Later reign

Construction in Mali

Musa embarked on a large building program, raising mosques and madrasas in Timbuktu and Gao. Most notably, the ancient center of learning Sankore Madrasah (or University of Sankore) was constructed during his reign.

In Niani, Musa built the Hall of Audience, a building communicating by an interior door to the royal palace. It was "an admirable Monument", surmounted by a dome and adorned with arabesques of striking colours. The wooden window frames of an upper storey were plated with silver foil; those of a lower storey with gold. Like the Great Mosque, a contemporaneous and grandiose structure in Timbuktu, the Hall was built of cut stone.

During this period, there was an advanced level of urban living in the major centers of Mali. Sergio Domian, an Italian scholar of art and architecture, wrote of this period: "Thus was laid the foundation of an urban civilization. At the height of its power, Mali had at least 400 cities, and the interior of the Niger Delta was very densely populated."

Economy and education

It is recorded that Mansa Musa traveled through the cities of Timbuktu and Gao on his way to Mecca, and made them a part of his empire when he returned around 1325. He brought architects from Andalusia, a region in Spain, and Cairo to build his grand palace in Timbuktu and the great Djinguereber Mosque that still stands.

Timbuktu soon became the center of trade, culture, and Islam; markets brought in merchants from Hausaland, Egypt, and other African kingdoms, a university was founded in the city (as well as in the Malian cities of Djenné and Ségou), and Islam was spread through the markets and university, making Timbuktu a new area for Islamic scholarship. News of the Malian empire's city of wealth even traveled across the Mediterranean to southern Europe, where traders from Venice, Granada, and Genoa soon added Timbuktu to their maps to trade manufactured goods for gold.

The University of Sankore in Timbuktu was restaffed under Musa's reign with jurists, astronomers, and mathematicians. The university became a center of learning and culture, drawing Muslim scholars from around Africa and the Middle East to Timbuktu.

In 1330, the kingdom of Mossi invaded and conquered the city of Timbuktu. Gao had already been captured by Musa's general, and Musa quickly regained Timbuktu, built a rampart and stone fort, and placed a standing army to protect the city from future invaders. While Musa's palace has since vanished, the university and mosque still stand in Timbuktu.

Death

The date of Mansa Musa's death is uncertain. Using the reign lengths reported by Ibn Khaldun to calculate back from the death of Mansa Suleyman in 1360, Musa would have died in 1332. However, Ibn Khaldun also reports that Musa sent an envoy to congratulate Abu al-Hasan Ali for his conquest of Tlemcen, which took place in May 1337, but by the time Abu al-Hasan sent an envoy in response, Musa had died and Suleyman was on the throne, suggesting Musa died in 1337. In contrast, al-Umari, writing twelve years after Musa's hajj, in approximately 1337, claimed that Musa returned to Mali intending to abdicate and return to live in Mecca but died before he could do so, suggesting he died even earlier than 1332. It is possible that it was actually Musa's son Maghan who congratulated Abu al-Hasan, or Maghan who received Abu al-Hasan's envoy after Musa's death. The latter possibility is corroborated by Ibn Khaldun calling Suleyman Musa's son in that passage, suggesting he may have confused Musa's brother Suleyman with Musa's son Maghan. Alternatively, it is possible that the four-year reign Ibn Khaldun credits Maghan with actually referred to his ruling Mali while Musa was away on the hajj, and he only reigned briefly in his own right. Nehemia Levtzion regarded 1337 as the most likely date, which has been accepted by other scholars.

Legacy

Musa's reign is commonly regarded as Mali's golden age, but this perception may be the result of his reign being the best recorded by Arabic sources, rather than him necessarily being the wealthiest and most powerful mansa of Mali. The territory of the Mali Empire was at its height during the reigns of Musa and his brother Sulayman, and covered the Sudan-Sahel region of West Africa.

Musa is less renowned in Mandé oral tradition as performed by the jeliw. He is criticized for being unfaithful to tradition, and some of the jeliw regard Musa as having wasted Mali's wealth. However, some aspects of Musa appear to have been incorporated into a figure in Mandé oral tradition known as Fajigi, which translates as "father of hope". Fajigi is remembered as having traveled to Mecca to retrieve ceremonial objects known as boliw, which feature in Mandé traditional religion. As Fajigi, Musa is sometimes conflated with a figure in oral tradition named Fakoli, who is best known as Sunjata's top general. The figure of Fajigi combines both Islam and traditional beliefs.

The name "Musa" has become virtually synonymous with pilgrimage in Mandé tradition, such that other figures who are remembered as going on a pilgrimage, such as Fakoli, are also called Musa.

Wealth

Mansa Musa is renowned for his wealth and generosity. Online articles in the 21st century have claimed that Mansa Musa was the richest person of all time. Historians such as Hadrien Collet have argued that Musa's wealth is impossible to calculate accurately. Contemporary Arabic sources may have been trying to express that Musa had more gold than they thought possible, rather than trying to give an exact number. Further, it is difficult meaningfully to compare the wealth of historical figures such as Mansa Musa, due both to the difficulty of separating the personal wealth of a monarch from the wealth of the state and to the difficulty of comparing wealth across highly different societies. Musa may have taken as much as 18 tons of gold on his hajj, equal in value to over US$1.397 billion in 2024. Musa himself further promoted the appearance of having vast, inexhaustible wealth by spreading rumors that gold grew like a plant in his kingdom.

According to some Arabic writers, Musa's gift-giving caused a depreciation in the value of gold in Egypt. Al-Umari said that before Musa's arrival a mithqal of gold was worth 25 silver dirhams, but that it dropped to less than 22 dirhams afterward and did not go above that number for at least twelve years. Though this has been described as having "wrecked" Egypt's economy, the historian Warren Schultz has argued that this was well within normal fluctuations in the value of gold in Mamluk Egypt.

The wealth of the Mali Empire did not come from direct control of gold-producing regions, but rather trade and tribute. The gold Musa brought on his pilgrimage probably represented years of accumulated tribute that Musa would have spent much of his early reign gathering. Another source of income for Mali during Musa's reign was taxation of the copper trade.

According to several contemporary authors, such as Ibn Battuta, Ibn al-Dawadari and al-Umari, Mansa Musa ran out of money during his journey to Mecca and had to borrow from Egyptian merchants at a high rate of interest on his return journey. Al-Umari and Ibn Khaldun state that the moneylenders were either never repaid or only partly repaid. Other sources disagree as to whether they were eventually and fully compensated.

Character

Arabic writers, such as Ibn Battuta and Abdallah ibn Asad al-Yafii, praised Musa's generosity, virtue, and intelligence. Ibn Khaldun said that he "was an upright man and a great king, and tales of his justice are still told."

Footnotes

- Arabic: منسا موسى, romanized: Mansā Mūsā

- The dates of Musa's reign are uncertain. Musa is reported to have reigned for 25 years, and different lines of evidence suggest he died either c. 1332 or c. 1337, with the 1337 date being considered more likely.

- The name is transcribed in the Tarikh al-Sudan as Kankan (Arabic: كنكن, romanized: Kankan), which Cissoko concluded was a representation of the Mandinka woman's name Kanku

- The Tarikh Ibn al-Mukhtar is a historiographical name for an untitled manuscript by Ibn al-Mukhtar. This document is also known as the Tarikh al-Fattash, which Nobili and Mathee have argued is properly the title of a 19th-century document that used Ibn al-Mukhtar's text as a source.

- The sixth mansa, Sakura, is omitted from this chart as he was not related to the others. The third and fourth mansas (Wati and Khalifa), brothers of Uli, and fifth (Abu Bakr), a nephew of Uli, Wati, and Khalifa, are omitted to save space.

- Name from oral tradition

- Name from oral tradition

- Musa's name Kanku Musa means "Musa son of Kanku", but the genealogy may not be literal.

- The exact date of Musa's accession is debated. Ibn Khaldun claims Musa reigned for 25 years, so his accession is dated to 25 years before his death. Musa's death may have occurred in 1337, 1332, or possibly even earlier, giving 1307 or 1312 as plausible approximate years of accession. 1312 is the most widely accepted by modern historians.

- 26 Rajab 724

- 28 Shawwal

References

Citations

- "The Cresques Project - Panel III". cresquesproject.net. Archived from the original on 12 February 2023. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- Levtzion 1963, p. 346

- Bühnen 1994, p. 12.

- Levtzion 1963, pp. 349–350.

- Levtzion 1963, p. 353

- ^ "Mansa Musa (Musa I of Mali)". National Geographic. National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 19 August 2022. Retrieved 6 September 2022.

- Davidson, Jacob (30 July 2015). "The 10 Richest People of All Time". Time. Archived from the original on 24 August 2015. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- Rodriguez, Junius P. (1997). The Historical Encyclopedia of World Slavery. ABC-CLIO. p. 449. ISBN 978-0-87436-885-7. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- McKissack & McKissack 1994, p. 56.

- Gomez 2018, p. 87

- MacBrair 1873, p. 40

- Bell 1972, p. 230

- Cissoko 1969.

- ^ Gomez 2018, p. 109.

- ^ Collet 2019, p. 115–116.

- Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, p. 358.

- ^ Niane 1959.

- Gomez 2018, pp. 109, 129

- Al-Umari, Chapter 10.

- Nobili & Mathee 2015.

- Gomez 2018, pp. 92–93.

- Gomez 2018, pp. 92–93; Niane 1984, pp. 147–152.

- Levtzion 1963.

- Gomez 2018, pp. 109–110

- Levtzion 1963, p. 347

- Fauvelle 2022, p. 156.

- ^ Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, p. 295.

- Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, p. 416.

- Fauvelle 2022, p. 173-4.

- Fauvelle 2022, p. 185.

- ^ Gomez 2018, p. 104.

- ^ Bell 1972

- Levtzion 1963, pp. 349–350

- Fauvelle 2018

- Al-Umari, Chapter 10

- Ibn Khaldun

- Gomez 2018

- Thornton 2012, pp. 9, 11

- Gomez 2018, p. 101.

- Devisse & Labib 1984, p. 666.

- Thornton 2012, p. 13.

- ^ Gomez 2018, p. 105.

- ^ Gomez 2018, p. 107.

- Al-Umari, translated in Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, p. 267

- ^ Goodwin 1957, p. 110.

- Al-Umari, translated in Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, p. 268

- Gomez 2018, p. 4.

- Pollard, Elizabeth (2015). Worlds Together Worlds Apart. New York: W.W. Norton Company Inc. p. 362. ISBN 978-0-393-91847-2.

- Wilks, Ivor (1997). "Wangara, Akan, and Portuguese in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries". In Bakewell, Peter John (ed.). Mines of Silver and Gold in the Americas. Aldershot: Variorum, Ashgate Publishing Limited. p. 7. ISBN 9780860785132.

- Cuoq 1985, p. 347.

- The Royal Kingdoms of Ghana, Mali, and Songhay: Life in Medieval Africa By Patricia McKissack, Fredrick McKissack Page 60

- ^ Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, p. 355.

- Gomez 2018, pp. 114, 117.

- Gomez 2018, p. 116.

- Collet 2019, p. 111.

- Collet 2019, pp. 115–122.

- Gomez 2018, p. 118.

- Collet 2019, pp. 122–129.

- Gomez 2018, pp. 118–120.

- Hunwick 1990, pp. 60–61.

- Al-Umari, translated in Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, p. 261

- al-Sadi, translated in Hunwick 1999, p. 10

- ^ Fauvelle 2022, p. 79.

- Ibn Khaldun, translated in Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, p. 334

- Levtzion 1973, p. 75.

- "The University of Sankore, Timbuktu". 7 June 2003.

- "Mansa Musa". African History Restored. 2008. Archived from the original on 2 October 2008. Retrieved 29 September 2008.

- De Villiers & Hirtle 2007, p. 70.

- De Villiers & Hirtle 2007, p. 74.

- De Villiers & Hirtle 2007, p. 87–88.

- Goodwin 1957, p. 111.

- De Villiers & Hirtle 2007, p. 80–81.

- Levtzion 1963, p. 349.

- ^ Levtzion 1963, p. 350.

- Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, pp. 252, 413.

- Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, p. 268.

- Bell 1972, p. 224.

- Bell 1972, p. 225–226.

- Bell 1972, p. 225.

- Bell 1972, p. 226–227.

- Sapong 2016, p. 2.

- Gomez 2018, p. 145.

- Canós-Donnay 2019.

- Niane 1984, p. 152.

- Gomez 2018, pp. 92–93

- Niane 1984.

- ^ Mohamud 2019.

- ^ Conrad 1992, p. 152.

- Conrad 1992, p. 153.

- Conrad 1992, pp. 153–154.

- ^ Collet 2019, p. 106.

- Davidson 2015b.

- Davidson 2015a.

- Gomez 2018, p. 106.

- "Gold Price in US Dollars (USD/oz t)". YCharts. Archived from the original on 24 January 2022. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- Gomez 2018, p. 121.

- Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, p. 271.

- Schultz 2006.

- Gomez 2018, pp. 107–108.

- Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, p. 272.

- Gomez 2018, pp. 119–120

- Abbou, Tahar (2020). "Mansa Musa's Journey to Mecca and Its Impact on Western Sudan (Conference: 'Routes of Hajj in Africa', at International University of Africa, Khartoum)".

With his lavish spending and generosity in Cairo, (Mansa Musa) ran out of money and had to borrow at high rates of interest for the return journey. Ibn Battuta says that Mansa Musa borrowed 50,000 dinars from Siraj al-Din ibn al-Kuwayk, a rich merchant from Alexandria, after he had spent all his wealth.

- Whalen, Brett Edward, ed. (2011). Pilgrimage in the Middle Ages: A Reader. University of Toronto Press. p. 308. ISBN 9781442603844.

could not meet his expenses. He therefore borrowed money from the principal merchants. Among those merchants who were in his company were the Banu l-Kuwayk, who gave him a loan of 50,000 dinars. He sold to them the palace which the sultan had bestowed on him as a gift. He approved it. Siraj al-Din b. al-Kuwayk sent his vizier along with him to collect what he had loaned to him but the vizier died there. Siraj al-Din sent another with his son. He died but the son, Fakhr al-Din Abu Jafar, got back some of it. Mansa Musa died before he died, so they obtained nothing more from him.

- Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, p. 334.

Primary sources

- Al-Umari, Masalik al-Absar fi Mamalik al-Amsar, translated in Levtzion & Hopkins 2000

- al-Sadi, Taʾrīkh al-Sūdān, translated in Hunwick 1999

- Cuoq, Joseph, ed. (1985). Recueil des sources arabes concernant l'Afrique occidentale du VIIIeme au XVIeme siècle (Bilād Al-Sūdān). Paris: Éditions du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique.

- Ibn Khaldun, Kitāb al-ʿIbar wa-dīwān al-mubtadaʾ wa-l-khabar fī ayyām al-ʿarab wa-ʾl-ʿajam wa-ʾl-barbar, translated in Levtzion & Hopkins 2000

Other sources

- Bell, Nawal Morcos (1972). "The age of Mansa Musa of Mali: Problems in succession and chronology". International Journal of African Historical Studies. 5 (2): 221–234. doi:10.2307/217515. JSTOR 217515.

- Bühnen, Stephan (1994). "In Quest of Susu". History in Africa. 21: 1–47. doi:10.2307/3171880. ISSN 0361-5413. JSTOR 3171880. S2CID 248820704. Archived from the original on 18 April 2023. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- Canós-Donnay, Sirio (25 February 2019). "The Empire of Mali". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.013.266. ISBN 978-0-19-027773-4. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- Conrad, David C. (1992). "Searching for History in The Sunjata Epic: The Case of Fakoli". History in Africa. 19: 147–200. doi:10.2307/3171998. eISSN 1558-2744. ISSN 0361-5413. JSTOR 3171998. S2CID 161404193. Archived from the original on 18 April 2023. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- Cissoko, S. M. (1969). "Quel est le nom du plus grand empereur du Mali: Kankan Moussa ou Kankou Moussa". Notes Africaines. 124: 113–114.

- Collet, Hadrien (2019). "Échos d'Arabie. Le Pèlerinage à La Mecque de Mansa Musa (724–725/1324–1325) d'après des Nouvelles Sources". History in Africa. 46: 105–135. doi:10.1017/hia.2019.12. eISSN 1558-2744. ISSN 0361-5413. S2CID 182652539. Archived from the original on 15 April 2022. Retrieved 15 April 2022.

- Davidson, Jacob (2015a). "How to Compare Fortunes Across History". Money.com. Archived from the original on September 21, 2021.

- Davidson, Jacob (2015b). "The 10 Richest People of All Time". Money.com. Archived from the original on 31 January 2022.

- De Villiers, Marq; Hirtle, Sheila (2007). Timbuktu: Sahara's fabled city of gold. New York: Walker and Company.

- Devisse, Jean; Labib, S. (1984). "Africa in inter-continental relations". In Niane, D.T. (ed.). General History of Africa, IV: Africa From the Twelfth to the Sixteenth Century. Berkeley California: University of California. pp. 635–672. ISBN 0-520-03915-7. Archived from the original on 25 April 2022. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- Fauvelle, François-Xavier (2018) . "The Sultan and the Sea". The Golden Rhinoceros: Histories of the African Middle Ages. Troy Tice (trans.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-18126-4.

- Fauvelle, Francois-Xavier (2022). Les masques et la mosquée - L’empire du Mâli XIIIe XIVe siècle. Paris: CNRS Editions. ISBN 2271143713.

- Gomez, Michael A. (2018). African Dominion: A New History of Empire in Early and Medieval West Africa. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691196824.

- Goodwin, A. J .H. (1957). "The Medieval Empire of Ghana". South African Archaeological Bulletin. 12 (47): 108–112. doi:10.2307/3886971. JSTOR 3886971.

- Hamdun, Said; King, Noël Q. (2009) . Ibn Battuta in Black Africa. Princeton: Markus Wiener. ISBN 978-1-55876-336-4.

- Hunwick, J. O. (1990). "An Andalusian in Mali: a contribution to the biography of Abū Ishāq al-Sāhilī, c. 1290–1346". Paideuma. 36: 59–66. JSTOR 40732660.

- Hunwick, John O. (1999). Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire: Al-Sadi's Tarikh al-Sudan down to 1613 and other contemporary documents. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 90-04-11207-3.

- Levtzion, Nehemia (1963). "The thirteenth- and fourteenth-century kings of Mali". Journal of African History. 4 (3): 341–353. doi:10.1017/s002185370000428x. JSTOR 180027. S2CID 162413528.

- Levtzion, Nehemia (1973). Ancient Ghana and Mali. London: Methuen. ISBN 0-8419-0431-6.

- Levtzion, Nehemia; Hopkins, John F. P., eds. (2000) . Corpus of Early Arabic Sources for West Africa. New York: Marcus Weiner Press. ISBN 1-55876-241-8.

- MacBrair, R. Maxwell (1873). A Grammar of the Mandingo Language: With Vocabularies. London: John Mason.

- McKissack, Patricia; McKissack, Fredrick (1994). The Royal Kingdoms of Ghana, Mali and Songhay: Life in Medieval Africa. New York: Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 0-8050-4259-8.

- Mohamud, Naima (10 March 2019). "Is Mansa Musa the richest man who ever lived?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 10 March 2019.

- Niane, Djibril Tamsir (1959). "Recherches sur l'Empire du Mali au Moyen Age". Recherches Africaines (in French). Archived from the original on 19 May 2007.

- Niane, D. T. (1984). "Mali and the second Mandingo expansion". In Niane, D. T. (ed.). Africa from the Twelfth to the Sixteenth Century. General history of Africa. Vol. 4. pp. 117–171.

- Nobili, Mauro; Mathee, Mohamed Shahid (2015). "Towards a New Study of the So-Called Tārīkh al-fattāsh". History in Africa. 42: 37–73. doi:10.1017/hia.2015.18. eISSN 1558-2744. ISSN 0361-5413. S2CID 163126332. Archived from the original on 15 April 2022. Retrieved 15 April 2022.

- Sapong, Nana Yaw B. (11 January 2016). "Mali Empire". In Dalziel, Nigel; MacKenzie, John M. (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Empire. Oxford, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. pp. 1–5. doi:10.1002/9781118455074.wbeoe141. ISBN 978-1-118-45507-4.

- Schultz, Warren (2006). "Mansa Mūsā's gold in Mamluk Cairo: a reappraisal of a world civilizations anecdote". In Pfeiffer, Judith; Quinn, Sholeh A. (eds.). History and historiography of post-Mongol Central Asia and the Middle East: studies in honor of John E. Woods. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 428–447. ISBN 3-447-05278-3.

- Thornton, John K. (10 September 2012). A Cultural History of the Atlantic World, 1250–1820. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521727341. Archived from the original on 18 April 2023. Retrieved 12 September 2021.

Further reading

- Ibn Battuta; Ibn Juzayy. Tuḥfat an-Nuẓẓār fī Gharāʾib al-Amṣār wa ʿAjāʾib al-Asfār., translated in Levtzion & Hopkins 2000 and Hamdun & King 2009

External links

- Mansa Musa I at World History Encyclopedia

- Mansa Moussa: Pilgrimage of Gold (archived) at History Channel's History.com

- Caravans of Gold, Fragments in Time: Art, Culture, and Exchange across Medieval Saharan Africa at Northwestern University's Block Museum of Art

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded byMuhammad ibn Qu | Mansa of the Mali Empire 1312–1337 |

Succeeded byMaghan |

| Mansas of the Mali Empire | |

|---|---|