| Revision as of 00:24, 3 July 2007 editSteel (talk | contribs)20,265 edits No sources← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 16:32, 27 December 2024 edit undoDenisarona (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers161,896 editsm →Writings | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Irish revolutionary (1879–1916)}} | |||

| {{Infobox Military Person | |||

| {{Use Hiberno-English|date=February 2024}} | |||

| |name= '''Patrick Henry Pearse''' <br> {{lang-ga|Pádraig Anraí Mac Piarais}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=April 2024}} | |||

| |lived= ], ] – ], ] | |||

| {{Infobox person | |||

| |placeofbirth= ], ] | |||

| | image = Patrick Pearse cph.3b15294.jpg | |||

| |placeofdeath= ], ], ] | |||

| | alt = <!-- descriptive text for use by speech synthesis (text-to-speech) software --> | |||

| |image= ] | |||

| |caption |

| caption = | ||

| | native_name = Pádraig Mac Piarais | |||

| |nickname= | |||

| | birth_date = {{Birth date|df=y|1879|11|10}} | |||

| |allegiance= ]<br>]<br>]<br>] | |||

| | birth_place = ], Ireland | |||

| |serviceyears= ] – ] | |||

| | death_date = {{Death date and age|df=y|1916|5|3|1879|11|10}} | |||

| |rank= ] | |||

| | death_place = ], Dublin, Ireland | |||

| |commands= | |||

| | death_cause = ] | |||

| |unit= | |||

| | restingplace = ] | |||

| |battles= ] | |||

| | mother = ] | |||

| |awards= | |||

| | other_names = Pádraig Pearse | |||

| |laterwork= | |||

| | occupation = {{flatlist| | |||

| * Educator | |||

| * principal | |||

| * barrister | |||

| * republican activist | |||

| * poet | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| | education = CBS Westland Row | |||

| | alma_mater = ]<br>] | |||

| '''Patrick Henry Pearse''' (known to ] ]s as '''Pádraig Pearse'''; {{lang-ga|Pádraig Anraí Mac Piarais}}; ], ] – ], ]) was a teacher, barrister, ], writer, nationalist and political activist who was one of the leaders of the ] in 1916. He was declared "President of the Provisional Government" of the ] in one of the bulletins issued by the Rising's leaders, a status that was however disputed by others associated with the rebellion both then and subsequently. Following the collapse of the Rising and the ] of Pearse, along with his brother and fourteen other leaders, Pearse came to be seen by many as the embodiment of the rebellion. | |||

| | signature = Signature of Patrick Pearse.png | |||

| | module = {{Infobox military person | |||

| | embed = yes | |||

| | allegiance = ]<br />] | |||

| | branch = | |||

| | serviceyears = 1913–1916 | |||

| | rank = Commander-in-chief | |||

| | unit = | |||

| | commands = | |||

| | battles = ] | |||

| }} | |||

| }} | |||

| '''Patrick Henry Pearse''' (also known as '''Pádraig''' or '''Pádraic Pearse'''; {{langx|ga|Pádraig Anraí Mac Piarais}}; 10 November 1879 – 3 May 1916) was an Irish teacher, ], ], writer, ], ] political activist and revolutionary who was one of the leaders of the ] in 1916. Following his execution along with fifteen others, Pearse came to be seen by many as the embodiment of the rebellion. | |||

| ==Early life and influences== | ==Early life and influences== | ||

| ] | |||

| Patrick Henry Pearse was born in ]. His father, James Pearse, was an English artisan/stonemason who moved to Ireland from Birmingham to take advantage of the boom in church building during the second half of the 19th century. He converted to Catholicism in 1870, probably for business reasons, and held moderate ] views. In 1877 he married his second wife, Margaret Brady. He had two children from his previous marriage, Emily and James (two other children from that marriage, Amy Kathleen and Agnes Maud, died in childbirth). Margaret was a native of Dublin, but her father's family were from ] and were native Irish speakers. The Irish-speaking influence of Pearse's great-aunt Margaret, together with his schooling at the ] Westland Row, instilled in him an early love for the Irish language. | |||

| Pearse, his brother ], and his sisters ] and Mary Brigid were born at 27 ], Dublin, the street that is named after them today.<ref>{{Cite journal | last = Thornley | first = David | title = Patrick Pearse and the Pearse Family | journal = Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review | volume = 60 | issue = 239/240 | pages = 332–346 | publisher = Irish Province of the Society of Jesus | location = Dublin | date =Autumn–Winter 1971 | jstor = 30088734 | issn = 0039-3495 }}</ref><ref>{{Cite book | last = Miller | first = Liam | title = The noble drama of W.B. Yeats | publisher = Dolmen Press | year = 1977 | location = Dublin | page = 33 | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=KapbAAAAMAAJ&q=%22pearse+street%22+patrick+willie | isbn = 978-0-391-00633-1 | access-date = 16 October 2016 | archive-date = 21 December 2019 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20191221123052/https://books.google.com/books?id=KapbAAAAMAAJ&q=%22pearse+street%22+patrick+willie | url-status = live }}</ref> It was here that their father, James Pearse, established a stonemasonry business in the 1850s,<ref>{{Cite book | last = Casey | first = Christine | title = Dublin: the city within the Grand and Royal Canals and the Circular Road with the Phoenix Park | publisher = ] | year = 2005 | location = New Haven and London | page = 62 | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=AQzYxvX_U8MC&pg=PA62 | isbn = 978-0-300-10923-8 | access-date = 3 October 2020 | archive-date = 18 April 2021 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20210418120338/https://books.google.com/books?id=AQzYxvX_U8MC&pg=PA62 | url-status = live }}</ref> a business which flourished and provided the Pearses with a comfortable middle-class upbringing.<ref>{{Cite book | last = Stevenson | first = Garth | title = Parallel paths: the development of nationalism in Ireland and Quebec | publisher = ] | year = 2006 | location = Montreal & Kingston | page = 189 | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=Sao_h6T4cB0C&pg=PA189 | isbn = 978-0-7735-3029-4 | access-date = 3 October 2020 | archive-date = 18 April 2021 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20210418114608/https://books.google.com/books?id=Sao_h6T4cB0C&pg=PA189 | url-status = live }}</ref> Pearse's father was a mason and monumental sculptor, and originally a ] from ] in England.<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180108063851/http://www.ricorso.net/rx/az-data/authors/p/Pearse_P/life.htm |date=8 January 2018 }} ''Ricorso'', Bruce Stewart. Retrieved 7 January 2011.</ref> His mother, ], was from Dublin, and her father's family were native Irish speakers from ]. She was James' second wife; James had two children, Emily and James, from his first marriage (two other children died in infancy). Pearse's maternal grandfather Patrick was a supporter of the 1848 ] movement, and later a member of the ] (IRB). Pearse recalled a visiting ballad singer performing republican songs during his childhood; afterwards, he went around looking for armed men ready to fight, but finding none, declared sadly to his grandfather that "the ] are all dead". His maternal grand-uncle, James Savage, fought in the ].<ref>{{Cite book |title=16 Lives: Patrick Pearse |page=17}}</ref> The Irish-speaking influence of Pearse's grand-aunt Margaret, together with his schooling at the CBS Westland Row, instilled in him an early love for the ] and ].<ref name=homelife>"The Home Life of Padraic Pearse" Edited by Mary Brigid Pearse. Published by Mercier Press Dublin and Cork.</ref> | |||

| Pearse grew up surrounded by books.<ref>{{Cite book | last = Walsh | first = Brendan | title = The pedagogy of protest: the educational thought and work of Patrick H. Pearse | publisher = Peter Lang | year = 2007 | location = Oxford | page = 12 | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=UA3fbLv1EQoC&pg=PA12 | isbn = 978-3-03910-941-8 | access-date = 3 October 2020 | archive-date = 18 April 2021 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20210418135609/https://books.google.com/books?id=UA3fbLv1EQoC&pg=PA12 | url-status = live }}</ref> His father had had very little formal education, but was self-educated;<ref>{{Cite web | last = Crowley | first = Brian | title = 'The strange thing I am': his father's son? | work = ] | publisher = History Publications Ltd | year = 2009 | url = http://www.historyireland.com/volumes/volume14/issue2/news/?id=114021 | access-date = 5 December 2010 | archive-date = 20 March 2012 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20120320004027/http://www.historyireland.com/volumes/volume14/issue2/news/?id=114021 | url-status = live }}</ref> Pearse recalled that at the age of ten he prayed to God, promising to dedicate his life to Irish independence.<ref>{{Cite book |title=16 Lives: Patrick Pearse |page=18}}</ref> Pearse's early heroes were ancient ] such as ], though in his 30s he began to take a strong interest in the leaders of past ] movements, such as the ] ] and ].<ref>{{cite news |last1=Mitchell |first1=Angus |title=Robert Emmet and 1916 |url=https://www.historyireland.com/20th-century-contemporary-history/robert-emmet-and-1916/ |access-date=13 April 2021 |archive-date=18 April 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210418104034/https://www.historyireland.com/20th-century-contemporary-history/robert-emmet-and-1916/ |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| In 1896, at the age of only sixteen, he joined the ] (''Conradh na Gaeilge''), and in 1903 at the age of 23, he became editor of its newspaper '']'' ("The Sword of Light"). | |||

| Pearse soon became involved in the ]. In 1896, at the age of 16, he joined the ] (''Conradh na Gaeilge''), and in 1903, at the age of 23, he became editor of its newspaper '']'' ("''The Sword of Light''").<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.minerva.mic.ul.ie//vol1/pearse.html |title=Flanagan, Frank M., "Patrick H. Pearse", ''The Great Educators'', March 20, 1995 |access-date=12 March 2016 |archive-date=25 September 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120925125438/http://www.minerva.mic.ul.ie/vol1/pearse.html |url-status=live }}</ref><ref></ref> | |||

| Pearse's earlier heroes were the ancient Gaelic folk heroes such as ], though in his 30s he began to take a strong interest in the leaders of past ] movements, such as the United Irishmen ] and ], both were Protestant but much of nationalist Ireland was Protestant in the eighteenth century; it was from these men that those such as the fervently Catholic Pearse drew inspiration for the rebellion of 1916. As ] wrote regarding Pearse, he (Pearse) viewed the Rising as "a Passion Play with real blood." | |||

| In 1900, Pearse was awarded a B.A. in Modern Languages (Irish, English and French) by the ], for which he had studied for two years privately and for one at ]. In the same year, he was enrolled as a ] at the ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ucc.ie/celt/pearse.html|title=CELT: Chronology of Patrick Pearse, also known as Pádraig Pearse (Pádraig Mac Piarais)|website=ucc.ie|access-date=9 November 2008|archive-date=11 May 2009|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090511144732/http://www.ucc.ie/celt/pearse.html|url-status=live}}</ref> Pearse was called to the bar in 1901. In 1905, Pearse represented ], a poet and songwriter from ], ], who had been fined for having his name displayed in "illegible" writing (i.e. Irish) on his donkey cart. The appeal was heard before the ] in Dublin. It was Pearse's first and only court appearance as a barrister. The case was lost but it became a symbol of the struggle for Irish independence. In his 27 June 1905 '']'' column, Pearse wrote of the decision, "it was in effect decided that Irish is a foreign language on the same level with Yiddish."<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://giveitsomesparkle.wordpress.com/2011/09/09/padraig-pearse-the-cart-and-an-old-song-book/|title=Padraig Pearse, the cart and an old song book|date=9 September 2011|website=Sparkle|access-date=10 April 2016|archive-date=6 September 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170906041307/https://giveitsomesparkle.wordpress.com/2011/09/09/padraig-pearse-the-cart-and-an-old-song-book/|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=McGill|first=P.J.|year=1966|title=Pearse Defends Niall Mac Giolla Bhride in Court of King's Bench, Dublin|journal=Donegal Annual|volume=1966|pages=83–85 (from 27 June 1905 article written by Patrick Pearse)|via=Google Books}}</ref> | |||

| ==St Enda's== | ==St Enda's== | ||

| ], now the Pearse Museum]] | |||

| As a cultural nationalist educated by the ] ], like his younger brother Willie, Pearse believed that language was intrinsic to the identity of a nation. The Irish school system, he believed, raised Ireland's youth to be good ] or obedient Irishmen, and an alternative was needed. Thus for him and other language revivalists, saving the ] from extinction was a cultural priority of the utmost importance. The key to saving the language, he felt, would be a sympathetic education system. To show the way, he started his own bilingual school, ] (Scoil Éanna) in ], ], in 1908. Here, the pupils were taught in both the Irish and English languages. | |||

| As a cultural nationalist educated by the ], like his younger brother Willie, Pearse believed that language was intrinsic to the identity of a nation. The Irish school system, he believed, raised Ireland's youth to be good ] or obedient Irishmen and an alternative was needed. Thus for him and other language revivalists saving the ] from extinction was a cultural priority of the utmost importance. The key to saving the language, he felt, would be a sympathetic education system. To show the way he started his own bilingual school for boys, ] (Scoil Éanna) in Cullenswood House in ], a suburb of ], in 1908.<ref name="nli">{{Cite web|url = http://www.nli.ie/1916/pdf/4.4.pdf|title = Patrick Pearse|work = The 1916 Rising: Personalities and Perspectives|year = 2006|publisher = National Library of Ireland|url-status = dead|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20060519214523/http://www.nli.ie/1916/pdf/4.4.pdf|archive-date = 19 May 2006|df = dmy-all}}</ref> | |||

| Pearse's restless idealism led him in search of an even more idyllic home for his school. He found it in The Hermitage in ], County Dublin, now home to the ]. In 1910 Pearse wrote that the Hermitage was an "ideal" location due to the aesthetics of the grounds and that if he could secure it, "the school would be on a level with" the more established schools of the day such as "] and ]".<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=UA3fbLv1EQoC&q=patrick+pearse+clongowes&pg=PA288|title=The Pedagogy of Protest: The Educational Thought and Work of Patrick H. Pearse|last=Walsh|first=Brendan|date=2007|publisher=Peter Lang|isbn=978-3-03910-941-8|language=en|access-date=3 October 2020|archive-date=18 April 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210418132447/https://books.google.com/books?id=UA3fbLv1EQoC&q=patrick+pearse+clongowes&pg=PA288|url-status=live}}</ref> Pearse was also involved in the foundation of Scoil Íde (St Ita's School) for girls, an institution with aims similar to those of St Enda's.<ref name="nli" /> | |||

| With the aid of ], Pearse's younger brother ] and other (often transient) academics, it soon proved a successful experiment. He did all he planned, and even brought students on fieldtrips to the ] in the west of Ireland. Pearse's restless idealism led him in search of an even more idyllic home for his school. He found it in the Hermitage, ], where he moved St. Enda's in 1910. Pearse was also involved in the foundation of St. Ita's school for girls, a school with similar aims to St. Enda's. | |||

| ==The Volunteers and Home Rule== | |||

| However, the new home, while splendidly located in an 18th-century house surrounded by a park and woodlands, caused financial difficulties that almost brought him to disaster. He strove continually to keep ahead of his debts while doing his best to maintain the school. | |||

| In April 1912 ] leader of the ], which held the balance of power in the ] committed the government of the ] to introduce an ]. Pearse gave the bill a qualified welcome. He was one of four speakers, including Redmond, ] MP, leader of the Northern Nationalists, and ] a prominent Gaelic Leaguer, who addressed a large Home Rule Rally in Dublin at the end of March 1912. Speaking in Irish, Pearse said he thought that "a good measure can be gained if we have enough courage", but he warned, "Let the English understand that if we are again betrayed, there shall be red war throughout Ireland".<ref>Ruth Dudley Edwards, ''Patrick Pearse: The Triumph of Failure,'' (1977) p. 159</ref> | |||

| In November 1913 Pearse was invited to the inaugural meeting of the ]—formed in reaction to the creation of the ]—whose aim was "to secure and maintain the rights and liberties common to the whole people of Ireland".<ref>{{Cite book|last1=Foy|first1=Michael|last2=Barton|first2=Brian|title=The Easter Rising|publisher=Sutton Publishing|year=2004|pages=|isbn=0-7509-3433-6|url=https://archive.org/details/easterrising0000foym/page/7}}</ref> In an article entitled "The Coming Revolution" (November 1913) Pearse wrote: | |||

| ==The Volunteers, the IRB and the Easter Rising== | |||

| {{quote|As to what your work as an Irish Nationalist is to be, I cannot conjecture; I know what mine is to be, and would have you know yours and buckle yourselves to it. And it may be (nay, it is) that your and mine will lead us to a common meeting-place, and that on a certain day we shall stand together, with many more beside us, ready for a greater adventure than any of us has yet had, a trial and a triumph to be endured and achieved in common.<ref name="Seán Cronin 1966, pg.15">Seán Cronin, ''Our Own Red Blood'', Irish Freedom Press, New York, 2014, p. 15 {{ISBN?}}</ref> | |||

| {{Easter Proclamation}} | |||

| }} | |||

| In November 1913 Pearse was invited to the inaugural meeting of the ], formed to enforce the implementation of Westminster's Home Rule Act in the face of opposition from the ]. The bill had just failed to pass the ] at the third effort, but the diminished power of the Lords under the ] meant that the bill was only to be delayed. | |||

| The Home Rule Bill just failed to pass the ], but the Lords' diminished power under the ] meant that the Bill could only be delayed, not stopped. It was placed on the statute books with ] in September 1914, but its implementation was suspended for the duration of the ]. | |||

| Early in 1914, Pearse became a member of the secret ], an organisation dedicated to the overthrow of British rule in Ireland and its replacement with a ]. Pearse was then one of many people who were members of both the IRB and the Volunteers. When he became the Volunteers' Director of Military Organisation in 1914 he was the highest ranking Volunteer in the IRB membership, and instrumental in the latter's commandeering of the Volunteers for the purpose of rebellion. By 1915 he was on the IRB's Supreme Council, and its secret Military Council, the core group that began planning for a rising while ] raged on the ]an mainland. | |||

| John Redmond feared that his "national authority" might be circumvented by the Volunteers and decided to try to take control of the new movement. Despite opposition from the Irish Republican Brotherhood, the Volunteer Executive agreed to share leadership with Redmond and a joint committee was set up. Pearse was opposed to this and was to write:<ref name="Seán Cronin 1966, pg.15"/> | |||

| ] featured Pearse in place of the harp]] | |||

| {{quote|The leaders in Ireland have nearly always left the people at the critical moment; they have sometimes sold them. The former Volunteer movement was abandoned by its leaders; ] recoiled before the cannon at ]; twice the hour of the Irish revolution struck during ] days and twice it struck in vain, for ] hesitated in ], ] and ] hesitated in Dublin. ] refused to ]; he never came in '66 or '67. I do not blame these men; you or I might have done the same. It is a terrible responsibility to be cast on a man, that of bidding the cannon speak and the ] pour.<ref name="Seán Cronin 1966, pg.15"/>}} | |||

| On ], ], Pearse gave a now-famous ] at the funeral of the ] ]. It closed with the words: ''"Our foes are strong and wise and wary; but, strong and wise and wary as they are, they cannot undo the miracles of God Who ripens in the hearts of young men the seeds sown by the young men of a former generation. And the seeds sown by the young men of '65 and ] are coming to their miraculous ripening today. Rulers and Defenders of the Realm had need to be wary if they would guard against such processes. Life springs from death; and from the graves of patriot men and women spring living nations. The Defenders of this Realm have worked well in secret and in the open. They think that they have pacified Ireland. They think that they have purchased half of us and intimidated the other half. They think that they have foreseen everything, think that they have provided against everything; but, the fools, the fools, the fools! — They have left us our Fenian dead, and while Ireland holds these graves, Ireland unfree shall never be at peace."'' | |||

| The Volunteers split, one of the issues being support for the ] and the British war effort. A majority followed Redmond into the ] in the belief that this would ensure Home Rule on their return. Pearse, exhilarated by the dramatic events of the European war, wrote in an article in December 1915: | |||

| ==Was Pearse "President of the Irish Republic"?== | |||

| Pearse, given his speaking and writing skills, was chosen by the leading IRB man ] to be the spokesman for the Rising that he hoped would soon occur. It was Pearse who, shortly before Easter in 1916, issued the orders to all Volunteer units throughout the country for three days of manoeuvres beginning Easter Sunday, which was the signal for a general uprising. When ], the Chief of Staff of the Volunteers, learned what was being planned without the promised arms from Germany, he countermanded the orders via newspaper, causing Pearse to issue a last minute order to go through with the plan the following day, greatly limiting the numbers who turned out for the rising. Without MacNeill on board as their figurehead, the Military Council needed someone else to take the title of ] and Commander-in-Chief. Pearse was allegedly chosen over Clarke, as Clarke was a convicted felon and it was claimed eschewed any such role, while Pearse was respected throughout the country, and a natural leader. | |||

| {{quote|It is patriotism that stirs the people. Belgium defending her soil is heroic, and so is Turkey . . . . . . <br>It is good for the world that such things should be done. The old heart of the earth needed to be warmed with the red wine of the battlefields.<br> Such august homage was never before offered to God as this, the homage of millions of lives given gladly for love of country.<br>War is a terrible thing, and this is the most terrible of wars. But this war is not more terrible than the evils which it will end or help to end.<ref>"Peace and the Gael", in Patrick H. Pearse, ''Political writings and speeches'', Phoenix, Dublin, (1924) p. 216, ]</ref>}} | |||

| However, the claim that Pearse was designated ''President of the Republic'' was widely disputed in the aftermath of the Rising. The government described itself as 'provisional'. Clarke's wife stated in her autobiography that the Rising leaders understood that Clarke was to be president, hence his position as the first name on the list of signatories of the proclamation. ], son of Tom Clarke, then a child, recounted meeting surviving figures of the Rising in the presence of his mother when they were released. One leading figure asked Mrs Clarke and her son "Who in the hell made Pearse president?"<ref>Emmet Clarke, in an interview broadcast on ] ], ].</ref> Opponents of Pearse accused him of using his role as chief propagandist for the rebellion to draft statements referring to himself as ''president''. The claim that Pearse held such a role featured only in a secondary document issued, one drafted by Pearse himself, not in the actual Proclamation.<ref>Arthur Mitchell & Pádraig Ó Snodaigh, ''Irish Political Documents 1916-1949'', Irish Academic Press 1985.</ref> In addition that document used the term "President of the Provisional Government", not "President of the Republic". A "President of a government" is akin to a ], not a president of a state.<ref>Among states which use or used that form of address to refer to a prime minister are Spain and the ], where the latter's prime minister was called ''].</ref> Pearse and his colleagues also discussed proclaiming Prince ] (the Kaiser's youngest son) as an Irish constitutional monarch, if the ] won the ], which suggests that their ideas for the political future of the country had to await the war's outcome.<ref>FitzGerald G. ''Reflections on the Irish State'' Irish Academic Press, Dublin 2003 p.153.</ref> | |||

| ==Irish Republican Brotherhood== | |||

| When the people of Ireland voted overwhelmingly in the ] for ] to form an independent Irish parliament, ], the first paragraph of the ], read out at the first meeting of the ], mentions "''ár gceud Uachtarán Pádraig Mac Phiarais''" , thus giving Pearse recognition as President.) | |||

| ] at which he gave a ].]] | |||

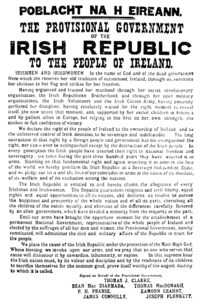

| ], read by Pearse outside the ] at the start of the ]]] | |||

| In December 1913 ] swore Pearse into the secret ] (IRB),<ref>In a statement to the Bureau of Military History, dated 26 January 1948, Hobson claimed: "After the formation of the Irish Volunteers in October 1913, Pádraig Pearse was sworn in by me as a member of the IRB in December of that year ... I swore him in before his departure for the States." (See: ], {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080228140800/http://www.nli.ie/1916/pdf/3.2.1.pdf |date=28 February 2008 }}, in ''The 1916 Rising: Personalities and Perspectives'', p. 18. Retrieved 1 January 2008. Hobson, in his ''Foundation of Growth of the Irish Volunteers, 1913–1914'', also states that Pearse was not a member of the IRB when the Irish Volunteers were founded in November.</ref> an organisation dedicated to the overthrow of ] and its replacement with an Irish Republic. He was soon co-opted onto the IRB's Supreme Council by ].<ref>] says in ''My Fight for Ireland's Freedom'' that it was "towards the end of 1913" when Tom Clarke had Pearse co-opted onto the Supreme Council of the IRB.</ref> Pearse was then one of many people who were members of both the IRB and the Volunteers. When he became the Volunteers' Director of Military Organisation in 1914<ref>], ''Myths from Easter 1916'', Aubane Historical Society, Cork, 2007, {{ISBN|978-1-903497-34-0}} p. 87</ref> he was the highest ranking Volunteer in the IRB membership, and instrumental in the latter's commandeering of the remaining minority of the Volunteers for the purpose of rebellion. By 1915 he was on the IRB's Supreme Council, and its secret Military Council, the core group that began planning for a rising while war raged on the European ]. | |||

| On 1 August 1915 Pearse gave a ] at the funeral of the ] ]. He was the first republican to be filmed giving an oration.<ref>{{Cite book |title=16 Lives: Patrick Pearse |page=121}}</ref> It closed with the words: | |||

| ==The Easter Rising and his execution== | |||

| When eventually the ] did erupt on Easter Monday, ], ], having been delayed by a day due to the interception by the British Navy of weapons arriving from Germany aboard the vessel ''Aud'' and the publication of MacNeill's countermanding order, it was Pearse who ] from the steps of the ], headquarters of the insurgents, to a bemused crowd. When, after several days fighting, it became apparent that victory was impossible, he surrendered, along with most of the other leaders. Pearse and fourteen other leaders, including his brother Willie, were ]led and ]. ], an IRB leader who had tried unsuccessfully to recruit an insurgent force among Irish-born prisoners of war in Germany, was hanged in London the following August. ], ] and Pearse himself were the first of the rebels to be executed, on the morning of ], ]. Pearse was 36 years old at the time of his death. | |||

| {{quote|Our foes are strong and wise and wary; but, strong and wise and wary as they are, they cannot undo the miracles of God who ripens in the hearts of young men the seeds sown by the young men of a former generation. And the seeds sown by the young men of '65 and ] are coming to their miraculous ripening today. Rulers and Defenders of the Realm had need to be wary if they would guard against such processes. Life springs from death; and from the graves of patriot men and women spring living nations. The Defenders of this Realm have worked well in secret and in the open. They think that they have pacified Ireland. They think that they have purchased half of us and intimidated the other half. They think that they have foreseen everything, think that they have provided against everything; but, the fools, the fools, the fools! – They have left us our Fenian dead, and while Ireland holds these graves, Ireland unfree shall never be at peace. (]}} | |||

| Writing subsequently, ] was critical of Pearse. Comparing him to ], Collins wrote: 'Of Pearse and Connolly I admire the latter most. Connolly was a realist, Pearse the direct opposite . . . I would have followed through hell had such action been necessary. But I honestly doubt very much if I would have followed Pearse — not without some thought anyway.<ref>Collins to Kevin O'Brien, Frongoch, ], ], quoted in Tim Pat Coogan, ''Michael Collins'', Hutchinson, 1990.</ref> | |||

| ==Easter Rising and death== | |||

| ] a noted revisionist, anti-Republican and Unionist <ref>Envoi, Taking Leave Of Roy Foster, by Brendan Clifford and Julianne Herlihy, Aubane Historical Society, Cork Pg 88, 96, 100, 146,152</ref> who’s views are characterised with her conclusion about Pearse and the Rising with the words: Pearse and his colleagues had no mandate, merely a belief that because their judgement was superior to those of the population at large, they were entitled to use violence.<ref>Ruth Dudley-Edwards, "The Terrible Legacy of Patrick Pearse", Sunday Independent, ] 2001.</ref> Pearse in his address to his court martial and his prediction of future events in history would no doubt contrast Edwards assertion: | |||

| {{Main|Easter Rising}} | |||

| “When I was a child of ten I went down on my knees by my bedside one night and promised God that I should devote my life to an effort to free my country. I have kept that promise. First among all earthly things, as a boy and as a man, I have worked for Irish freedom. I have helped to organize, to arm, to train, and to discipline my fellow countrymen to the sole end that, when the time came, they might fight for Irish freedom. The time, as it seemed to me, did come and we went into the fight. I am glad that we did, we seem to have lost, we have not lost. To refuse to fight would have been to lose, to fight is to win, we have kept faith with the past, and handed a tradition to the future… I assume I am speaking to Englishmen who value their own freedom, and who profess to be fighting for the freedom of Belgium and Serbia. Believe that we too love freedom and desire it. To us it is more desirable than anything else in the world. If you strike us down now we shall rise again and renew the fight. You cannot conquer Ireland; you cannot extinguish the Irish passion for freedom; if our deed has not been sufficient to win freedom then our children will win it by a better deed.”<ref> Max Caulfield, ''The Easter Rebellion'', Gill & MacMillian1963, 1995, Dublin</ref> | |||

| It was Pearse who, on behalf of the IRB shortly before Easter in 1916, issued the orders to all Volunteer units throughout the country for three days of manoeuvres beginning on Easter Sunday, which was the signal for a general uprising. When ], the Chief of Staff of the Volunteers, learned what was being planned without the promised arms from Germany, he countermanded the orders via newspaper, causing the IRB to issue a last-minute order to go through with the plan the following day, greatly limiting the numbers who turned out for the rising. | |||

| This point she herself conceded when in her autobiography of Pearse quoted the words of the poet AE (George Russell) who himself would have been a critic of Pearse: <ref> R.D. Edwards, ''The Triumph of Failure'', Victor Gollancz Ltd, London, 1990. </ref> | |||

| When the ] eventually began on Easter Monday, 24 April 1916, it was Pearse who read the ] from outside the ], the headquarters of the Rising. Pearse was the person most responsible for drafting the Proclamation, and he was chosen as President of the Republic.<ref>{{cite web|title=Patrick Pearse|url=http://www.rte.ie/centuryireland/index.php/articles/patrick-pearse|website=Century Ireland|publisher=]/]|access-date=1 March 2017|archive-date=2 March 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170302112451/http://www.rte.ie/centuryireland/index.php/articles/patrick-pearse|url-status=live}}</ref> After six days of fighting, heavy civilian casualties and great destruction of property, Pearse issued the order to surrender. | |||

| Their dream had left me numb and cold. <br> | |||

| But yet my spirit rose in pride. <br> | |||

| Refashioning in burnished gold<br> | |||

| The images of those who died<br> | |||

| Or were shut in the penal cell. <br> | |||

| Here’s to you. Pearse, your dream not mine, <br> | |||

| But yet the thought for this you fell<br> | |||

| Has turned life’s waters into wine. <br><ref> R.D. Edwards, ''The Triumph of Failure'', Victor Gollancz Ltd, London, 1990. </ref> | |||

| Pearse and fourteen other leaders, including his brother Willie, were ]led and ]. ], ] and Pearse himself were the first of the rebels to be executed, on the morning of 3 May 1916. Pearse was 36 years old at the time of his death. ], who had tried unsuccessfully to recruit an insurgent force among Irish-born prisoners of war from the ] in Germany, was hanged in London the following August. | |||

| In addition, Edwards in her introduction to her autobiography of Pearse, and as to how his actions would be viewed by later generations quoted a verse from W. B. Yeats' ''Three songs to the one burden,'' | |||

| ], the ], sent a telegram to ], then Prime Minister, advising him not to return the bodies of the Pearse brothers to their family, saying, "Irish sentimentality will turn these graves into martyrs' shrines to which annual processions will be made, which would cause constant irritation in this country."<ref name="P.H. Pearse, Proinsias Mac Aonghusa 1979">Quotations from P.H. Pearse, Proinsias Mac Aonghusa, Mercier Press, RP 1979, {{ISBN|0-85342-605-8}}</ref> Maxwell also suppressed a letter from Pearse to his mother,<ref>] at en.wikisource.org</ref> and two poems dated 1 May 1916. He submitted copies of them also to Prime Minister Asquith, saying that some of the content was "objectionable".<ref name="P.H. Pearse, Proinsias Mac Aonghusa 1979" /> | |||

| Some had no thought of victory<br> | |||

| But had gone out to die<br> | |||

| That Ireland s mind be greater, <br> | |||

| Her heart mount up on high;<br> | |||

| And yet who knows what’s yet to come? <br> | |||

| For Patrick Pearse had said<br> | |||

| That in every generation<br> | |||

| Must Ireland’s blood be shed. <br><ref> R.D. Edwards, ''The Triumph of Failure'', Victor Gollancz Ltd, London, 1990. </ref> | |||

| ==Writings== | |||

| ==Pearse's writings== | |||

| ], |

], County Kerry]] | ||

| Pearse wrote stories and poems in both |

Pearse wrote stories and poems in both Irish and English. His best-known English poems include "The Mother", "The Fool", "]" and "The Wayfarer".<ref>{{Cite book |title=The Mercier Companion to Irish literature |author=Seán McMahon and Jo O'Donoghue |year=1998 |publisher=] |location=Cork |isbn=1-85635-216-1 |page= |url-access=registration |url=https://archive.org/details/merciercompanion00mcma/page/183 }}</ref> He also wrote several ] plays in the ], including ''The King'', ''The Master'', and ''The Singer''. His short stories in Irish include ''Eoghainín na nÉan'' ("Eoineen of the Birds"), ''Íosagán'' ("Little Jesus"), ''An Gadaí'' ("The Thief"), ''Na Bóithre'' ("The Roads"), and ''An Bhean Chaointe'' ("The Keening Woman"). These were translated into English by ] (in the ''Collected Works'' of 1917).<ref>Patrick Pearse, ''Short Stories''. Trans. ]. Ed. Anne Markey. Dublin, 2009</ref> Most of his ideas on education are contained in his essay "]". He also wrote many essays on politics and language, notably "The Coming Revolution" and "Ghosts". | ||

| Pearse is closely associated with his rendering of the ] ], "]", for which he composed republican lyrics. | |||

| Largely because of a series of political pamphlets Pearse wrote in the months leading up to the 1916 Rising, he soon became recognised as the voice of the 1916 Rising. In the middle decades of the twentieth century, Pearse was idolised by ]s as the supreme idealist of their cause. | |||

| According to '']'' poet and ] ], despite Pearse's enthusiasm for the '']'' dialect of ] spoken around his summer cottage at ] in ], he chose to follow the usual practice of the ] by writing in ], which was considered less ] than other Irish dialects. | |||

| However, with the outbreak of conflict in ] in 1969, Pearse's legacy soon became associated with the ]. Pearse's reputation and writings were subject to criticism by some historians who saw him as a dangerous, fanatical, psychologically unsound individual under ultra-religious influences. As ], a former ] politician, put it in writing: "Pearse saw the Rising as a Passion Play with real blood." In his ] book '']'' Cruise O Brien was to reveal a deeper, more personal reason for his opposition to Pearse and indeed the ]. The Rising, he said, resulted in his family's "rightful" position, as leading members of the ] in Irish society being denied them. | |||

| Also according to Louis de Paor, Pearse's reading of the radically experimental poetry of ] and of the French ] led him to introduce ] into the ]. As a ], Pearse also left behind a very detailed blueprint for the ] of ], particularly in the ]. | |||

| Others defended Pearse, suggesting that to blame him for what was happening in Northern Ireland was unhistorical and a distortion of the real spirit of his writings. Though the passion of those arguments has waned with the continuing peace in Northern Ireland following the ] in 1998, his complex personality still remains a subject of controversy for those who wish to debate the evolving meaning of Irish nationalism. | |||

| Louis De Paor writes that Patrick Pearse was "the most perceptive ] and most accomplished poet", of the early Gaelic revival providing "a sophisticated model for a new literature in Irish that would reestablish a living connection with the pre-colonial Gaelic past while resuming its relationship with contemporary Europe, bypassing the monolithic influence of English."<ref>] (2016), ''Leabhar na hAthghabhála: Poems of Repossession: Irish-English Bilingual Edition'', ]. Page 20.</ref> For these reasons, de Paor called Pearse's death a catastrophic loss for ]. According to de Paor, this loss only began to be healed during the 1940s by the modernist poetry of ], ], and ]; and by the modernist novels '']'' by ] and '']'' by ]. | |||

| His former school, St. Enda's, Rathfarnham, on the south side of Dublin, is now the ] dedicated to his memory. | |||

| == |

==Reputation== | ||

| With the outbreak of conflict in ] in 1969, Pearse's legacy was used by the ]. | |||

| Pearse never wrote his first name as 'Pádraig', using 'Patrick' or P.H.' instead. After his death 'Pádraig' was adopted by supporters in recognition of his love of the ]. | |||

| Pearse's ideas have been seen by Seán Farrell Moran as belonging to the context of European cultural history as a part of a rejection of ] by European social thinkers.<ref>Sean Farrell Moran, "Patrick Pearse and the European Revolt Against Reason," Journal of the History of Ideas, 1989, 4.</ref> Additionally, his place within Catholicism, where his orthodoxy was challenged in the early 1970s,<ref>Francis J. Shaw, S.J., "The Canon of Irish History—A Challenge," in Studies, 61, 242, 115–53</ref> has been addressed to suggest that Pearse's theological foundations for his political ideas share in a long-existing tradition in western Christianity.<ref>Moran, "Patrick Pearse and Patriotic Soteriology" in The Irish Terrorism Experience, eds. Yonah Alexander and Alan O'Day, 1991, 9–29</ref> | |||

| His mother ] served as a ] in ] in the 1920s. His sister ] also served as a TD and ]. | |||

| Former ] ] ] described Pearse as one of his heroes and displayed a picture of Pearse over his desk in the ].<ref>Bertie Ahern, interviewed about Pearse on ], 9 April 2006.</ref> | |||

| Pearse's mother ] served as a ] in ] in the 1920s. His sister ] also served as a TD and ]. | |||

| ==Footnotes== | |||

| {{reflist}} | |||

| In a 2006 book, psychiatrists ] and Antoinette Walker speculated that Pearse had ].<ref name="Fitzgerald and Walker">{{Cite news |url=http://www.independent.ie/irish-news/rebel-pearse-was-no-gay-blade-but-had-autistic-temperment-26410577.html |title=Rebel Pearse was no gay blade but had autistic temperment [sic] |last=Collins |first=Liam |date=9 April 2006 |access-date=28 January 2019 |archive-date=16 November 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181116112137/https://www.independent.ie/irish-news/rebel-pearse-was-no-gay-blade-but-had-autistic-temperment-26410577.html |url-status=live }}</ref> Pearse's apparent "sexual immaturity", and some of his behaviour, has been the subject of comment since the 1970s by historians such as ], T. Ryle Dwyer and Seán Farrell Moran, who speculated that he was attracted to young boys.<ref>Ruth Dudley Edwards, ''Patrick Pearse: The Triumph of Failure'', Victor Gollancz, 1977, pp. 52–4</ref><ref>Sean Farrell Moran, '' {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170315182929/https://books.google.com/books?id=FgZbzSE1kuUC&pg=PA122 |date=15 March 2017 }}'', 1994, p. 122.</ref> His most recent biographer, ], concluded that "it seems most probable that he was sexually inclined this way".<ref>Joost Augusteijn, ''Patrick Pearse: The Making of a Revolutionary'', 2009, p. 62</ref> Fitzgerald and Walker maintain that there is absolutely no evidence of ] or ]; they allege that Pearse's apparent lack of sexual interest in women, and his "ascetic" and celibate lifestyle are consistent with a diagnosis of ].<ref name="Fitzgerald and Walker"/> Cultural historian Elaine Sisson has further said that Pearse's interest in and idealization of young boys needs to be seen in the context of the ] "cult of the boy".<ref>{{cite AV media |date=2001 |title=True Lives: P.H. Pearse; Fanatic Heart |medium=television documentary |time=42:23 |location=Dublin |publisher=]}}</ref> | |||

| ==Sources == | |||

| {{wikisource|Author:Patrick Pearse}} | |||

| {{wikiquote}} | |||

| * ], ''Michael Collins'', Hutchinson, 1990. | |||

| * ], ''Patrick Pearse: the Triumph of Failure'' London: Gollancz, 1977. | |||

| * ], ''Ireland Since the Famine'', Collins/Fontana, 1973. | |||

| * ], ''The Irish Republic'', Corgi, 1968. | |||

| * Arthur Mitchell & Pádraig Ó Snodaigh, ''Irish Political Documents 1916-1949'', Irish Academic Press 1985. | |||

| * Mary Pearse, ''The Home Life of Pádraig Pearse''. Cork, Mercies 1971. | |||

| In almost all of Pearse's portraits, he struck a sideways pose, concealing his left side. This was to hide a ] or squint in his left eye, which he felt was an embarrassing condition.<ref>John Spain, {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161220061957/http://www.independent.ie/irish-news/pearses-heroic-sideways-pose-he-did-it-to-hide-embarrassing-squint-29524364.html |date=20 December 2016 }}, ''Irish Independent'', 24 August 2013</ref> | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| * - Pearse's groundbreaking article on Montessori education | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| *]] | |||

| ==Commemoration== | |||

| * The building in Rathfarnham, on the south side of Dublin, that once housed Pearse's school, St Enda's, is now the ]. | |||

| * ] and ] in Dublin were renamed in 1926 in honour of Pearse and his brother Willie, Pearse Street (previously Great Brunswick Street) being their birthplace. Other Pearse Streets can be found in ], ], ], ], ], ] (formerly Sovereign Street), ], ], ], ], ], ] and ] (where there are also Pearse Park, Avenue, Road and other uses of the name). | |||

| * There are Pearse Roads in ], ] in Cork (which also has Pearse Place and Square), ], Cookstown (County Wicklow), ], ] (which also has Pearse Crescent and Terrace), Dublin 16, ], Graiguecullen (County Carlow), ], ] (which also has Pearse Avenue), ] and ] | |||

| * There are Pearse Parks (residential streets) in ], ] and ], and (parkland) on the outskirts of ] and in ] (the former demesne of ]). There are other Pearse Avenues in ], ], Mervue in ] and ]. ] has a Patrick Pearse Place and there is a Pearse Bridge in ]. There is a Pearse Brothers Park in ] and a Pearse Terrace in ]. | |||

| * ] has Pearse Drive and Pearse View. ] (Dublin) has a Pearse Memorial Park. | |||

| * ] has a statue built in commemoration. | |||

| * Every February, just before the Annual Irish language Dining celebration at ], the institution hosts an Irish language debate where a Bonn an Phiarsaigh (the Pearse medal) is awarded to the winner. | |||

| ===Educational institutions=== | |||

| Cullenswood House, the Pearse family home in Ranelagh where Pádraic first founded St Enda's, today houses a primary '']'' (school for education through the Irish language) called Lios na nÓg, part of a community-based effort to revive the Irish language. ] (Dublin) has the Pearse College of Further Education, and there was formerly an Irish language summer school in ] called Colaiste an Phiarsaigh. In ] there is an Irish-medium vocational school, Gairmscoil na bPiarsach. The main lecture hall at the Cadet School in Ireland is named after P.H. Pearse. In September 2014, Gaelcholáiste an Phiarsaigh, a new Irish language medium secondary school, opened its doors for the first time in the former Loreto Abbey buildings, just 1 km from the Pearse Museum in St Endas Park, Rathfarnham. Today Glanmire County Cork boasts the best secondary-level Irish-speaking college in Ireland called Coláiste an Phiarsaigh, which was named in honour and structured around Patrick Pearse's beliefs. | |||

| ===Sports venues and clubs=== | |||

| A number of ] clubs and playing fields in Ireland are named after Pádraic or both Pearses: | |||

| * ]: Pearse Park, ]; ], Belfast | |||

| * ]: ]; ] and its grounds, ], Armagh | |||

| * ]: ], Cork | |||

| * ]: ], Kilrea; Pearse's GFC, Waterside, Derry (defunct) | |||

| * ]: Pearse's Park, Ardara | |||

| * ]: ] (called after Pearse's school); Pearse's GAC, Rathfarnham (defunct) | |||

| * ]: ], Ros Muc;], Ballymacward & Gurteen; ], Salthill | |||

| * ]: ]; ] HC (defunct) | |||

| * ]: ], Limerick | |||

| * ]: ], Longford | |||

| * ]: ], Dundalk | |||

| * ]: ], and its grounds, Pearse Park | |||

| * ]: ] | |||

| * ]: ], Dregish; ]; and ], and its grounds, Pearse Park; a defunct club, ] | |||

| * ]: Naomh Eanna GAA (called after Pearse's school); P.H. Pearse's HC, Enniscorthy (defunct) | |||

| * ]: ], Arklow | |||

| So also are several outside Ireland: | |||

| * ]: ], Victoria | |||

| * ]: ], London | |||

| * ]: Pearse Park, Glasgow; Pearse Harps HC (defunct) | |||

| * ]: ], Huddersfield | |||

| * ]: ], Chicago; ], Detroit | |||

| There are also soccer clubs named Pearse Celtic FC in ] and in ], Dublin; and Liffeys Pearse FC, a south Dublin soccer club formed by the amalgamation of Liffey Wanderers and Pearse Rangers. A Pearse Rangers schoolboy football club remains in existence in Dublin. | |||

| ===Other commemorations=== | |||

| * In 1916 the English composer ], who had met the man, composed a tone poem entitled ''In Memoriam Patrick Pearse''. It received its first public performance in 2008.<ref> 24 July 2008</ref> | |||

| * In ] the Pearse Club on King Street was wrecked by an explosion in May 1938.<ref>"Belfast club wrecked", '']'', p. 1, 26 May 1938</ref> | |||

| * Westland Row Station in Dublin was renamed ] in 1966 after the Pearse brothers. | |||

| * The silver ] coin minted in 1966 featured the bust of Patrick Pearse. It is the sole Irish coin ever to have featured anyone associated with Irish history or politics. | |||

| * In ] the Patrick Pearse Tower was named after him. It was the first of Ballymun's tower blocks to be demolished in 2004.<ref> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130118163235/http://dublincitypubliclibraries.com/dublin-buildings/seven-towers-ballymun |date=18 January 2013 }} history of Ballymun Towers</ref> | |||

| * In 1999 the centenary of Pearse's induction as a member of the ] at the 1899 Pan Celtic ] in ] (when he took the ] Areithiwr) was marked by the unveiling of a plaque at the Consulate General of Ireland in Wales.<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160304001938/http://www.ballinagree.freeservers.com/ppearsegd9.html|date=4 March 2016}} Account of Gorsedd commemoration, 1999</ref> | |||

| * Postage stamps commemorating Pearse were issued by the Irish postal service in 1966, 1979 and 2008. | |||

| * Writer ] is nicknamed Pearse after Patrick Pearse.<ref name="Urban Book Circle">{{cite web |url=https://www.urbanbookcircle.com/prvoslav-ldquopearserdquo-vujcic.html |publisher=Urban Book Circle |title=Prvoslav Vujcic biography |access-date=3 March 2019 |date=16 May 2013 |archive-date=10 February 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190210135256/https://www.urbanbookcircle.com/prvoslav-ldquopearserdquo-vujcic.html |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| * In 2016 ] inaugurated a Pearse medal in recognition of Pearse's role as vice president of the province's Colleges' Committee. The medals are awarded to the best footballer and hurler in the Leinster senior championship each year.<ref>{{cite news|title=Dublin and Kilkenny dominate Leinster Pearse medal nominations|url=http://www.irishtimes.com/sport/gaelic-games/dublin-and-kilkenny-dominate-leinster-pearse-medal-nominations-1.2863485|newspaper=The Irish Times|access-date=12 November 2016|archive-date=12 November 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161112143751/http://www.irishtimes.com/sport/gaelic-games/dublin-and-kilkenny-dominate-leinster-pearse-medal-nominations-1.2863485|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ==Citations== | |||

| {{Reflist|35em}} | |||

| ==Sources== | |||

| * Joost Augusteijn, ''Patrick Pearse: The Making of a Revolutionary'', 2009. | |||

| * ], ''Michael Collins.'' Hutchinson, 1990. | |||

| * ], ''Patrick Pearse: the Triumph of Failure'', London: Gollancz, 1977. | |||

| * ], ''Ireland Since the Famine.'' London: Collins/Fontana, 1973. | |||

| * ], ''The Irish Republic.'' Corgi, 1968. | |||

| * Arthur Mitchell & Pádraig Ó Snodaigh, ''Irish Political Documents 1916–1949.'' Dublin: Irish Academic Press, 1985 | |||

| * Seán Farrell Moran, ''Patrick Pearse and the Politics of Redemption: The Mind of the Easter Rising 1916'', Washington, Catholic University Press, 1994 | |||

| ** "Patrick Pearse and the European Revolt against Reason," in ''The Journal of the History of Ideas'', 50:4 (1989), 625–43 | |||

| ** "Patrick Pearse and Patriotic Soteriology: The Irish Republican Tradition and the Sanctification of Political Self-Immolation" in ''The Irish Terrorism Experience'', ed. Yonah Alexander and Alan O'Day, 1991, 9–29 | |||

| * Brian Murphy, ''Patrick Pearse and the Lost Republican Ideal'', Dublin, James Duffy, 1990. | |||

| * Ruán O'Donnell, ''Patrick Pearse'', Dublin: O'Brien Press, 2016 | |||

| * Mary Pearse, ''The Home Life of Pádraig Pearse''. Cork: Mercier, 1971. | |||

| * Patrick Pearse, ''Short Stories.'' Trans. Joseph Campbell. Ed. Anne Markey. Dublin: University College Dublin Press, 2009 | |||

| * Elaine Sisson, "Pearse's Patriots: The Cult of Boyhood at St. Enda's." Cork University Press, 2004, repr. 2005 | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| {{Commons category|Patrick Pearse}} | |||

| {{Wikiquote}} | |||

| {{wikisource author}} | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * {{Internet Archive author |search=( Pearse AND (Patrick OR Padraic OR Pádraic OR Pádraig OR Padraig OR "1879–1916") )}} | |||

| * {{Librivox author |id=8678}} | |||

| * – Pearse's groundbreaking article on contemporary Irish education | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| {{Easter Rising}} | {{Easter Rising}} | ||

| {{Irish Republican Brotherhood}} | |||

| {{Gaelic literature}} | |||

| {{Irish poetry}} | |||

| {{Irish rebel songs}} | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Pearse, Patrick}} | {{DEFAULTSORT:Pearse, Patrick}} | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 16:32, 27 December 2024

Irish revolutionary (1879–1916)

| Patrick Pearse | |

|---|---|

| Pádraig Mac Piarais | |

| |

| Born | (1879-11-10)10 November 1879 Dublin, Ireland |

| Died | 3 May 1916(1916-05-03) (aged 36) Kilmainham Gaol, Dublin, Ireland |

| Cause of death | Execution by firing squad |

| Resting place | Arbour Hill Prison |

| Other names | Pádraig Pearse |

| Education | CBS Westland Row |

| Alma mater | University College Dublin King's Inns |

| Occupations |

|

| Mother | Margaret Brady |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | Irish Republican Brotherhood Irish Volunteers |

| Years of service | 1913–1916 |

| Rank | Commander-in-chief |

| Battles / wars | Easter Rising |

| Signature | |

Patrick Henry Pearse (also known as Pádraig or Pádraic Pearse; Irish: Pádraig Anraí Mac Piarais; 10 November 1879 – 3 May 1916) was an Irish teacher, barrister, poet, writer, nationalist, republican political activist and revolutionary who was one of the leaders of the Easter Rising in 1916. Following his execution along with fifteen others, Pearse came to be seen by many as the embodiment of the rebellion.

Early life and influences

Pearse, his brother Willie, and his sisters Margaret and Mary Brigid were born at 27 Great Brunswick Street, Dublin, the street that is named after them today. It was here that their father, James Pearse, established a stonemasonry business in the 1850s, a business which flourished and provided the Pearses with a comfortable middle-class upbringing. Pearse's father was a mason and monumental sculptor, and originally a Unitarian from Birmingham in England. His mother, Margaret Brady, was from Dublin, and her father's family were native Irish speakers from County Meath. She was James' second wife; James had two children, Emily and James, from his first marriage (two other children died in infancy). Pearse's maternal grandfather Patrick was a supporter of the 1848 Young Ireland movement, and later a member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB). Pearse recalled a visiting ballad singer performing republican songs during his childhood; afterwards, he went around looking for armed men ready to fight, but finding none, declared sadly to his grandfather that "the Fenians are all dead". His maternal grand-uncle, James Savage, fought in the American Civil War. The Irish-speaking influence of Pearse's grand-aunt Margaret, together with his schooling at the CBS Westland Row, instilled in him an early love for the Irish language and culture.

Pearse grew up surrounded by books. His father had had very little formal education, but was self-educated; Pearse recalled that at the age of ten he prayed to God, promising to dedicate his life to Irish independence. Pearse's early heroes were ancient Gaelic folk heroes such as Cúchulainn, though in his 30s he began to take a strong interest in the leaders of past republican movements, such as the United Irishmen Theobald Wolfe Tone and Robert Emmet.

Pearse soon became involved in the Gaelic revival. In 1896, at the age of 16, he joined the Gaelic League (Conradh na Gaeilge), and in 1903, at the age of 23, he became editor of its newspaper An Claidheamh Soluis ("The Sword of Light").

In 1900, Pearse was awarded a B.A. in Modern Languages (Irish, English and French) by the Royal University of Ireland, for which he had studied for two years privately and for one at University College Dublin. In the same year, he was enrolled as a Barrister-at-Law at the King's Inns. Pearse was called to the bar in 1901. In 1905, Pearse represented Neil McBride, a poet and songwriter from Feymore, Creeslough, County Donegal, who had been fined for having his name displayed in "illegible" writing (i.e. Irish) on his donkey cart. The appeal was heard before the Court of King's Bench in Dublin. It was Pearse's first and only court appearance as a barrister. The case was lost but it became a symbol of the struggle for Irish independence. In his 27 June 1905 An Claidheamh Soluis column, Pearse wrote of the decision, "it was in effect decided that Irish is a foreign language on the same level with Yiddish."

St Enda's

As a cultural nationalist educated by the Irish Christian Brothers, like his younger brother Willie, Pearse believed that language was intrinsic to the identity of a nation. The Irish school system, he believed, raised Ireland's youth to be good Englishmen or obedient Irishmen and an alternative was needed. Thus for him and other language revivalists saving the Irish language from extinction was a cultural priority of the utmost importance. The key to saving the language, he felt, would be a sympathetic education system. To show the way he started his own bilingual school for boys, St. Enda's School (Scoil Éanna) in Cullenswood House in Ranelagh, a suburb of County Dublin, in 1908.

Pearse's restless idealism led him in search of an even more idyllic home for his school. He found it in The Hermitage in Rathfarnham, County Dublin, now home to the Pearse Museum. In 1910 Pearse wrote that the Hermitage was an "ideal" location due to the aesthetics of the grounds and that if he could secure it, "the school would be on a level with" the more established schools of the day such as "Clongowes Wood College and Castleknock College". Pearse was also involved in the foundation of Scoil Íde (St Ita's School) for girls, an institution with aims similar to those of St Enda's.

The Volunteers and Home Rule

In April 1912 John Redmond leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party, which held the balance of power in the House of Commons committed the government of the United Kingdom to introduce an Irish Home Rule Bill. Pearse gave the bill a qualified welcome. He was one of four speakers, including Redmond, Joseph Devlin MP, leader of the Northern Nationalists, and Eoin MacNeill a prominent Gaelic Leaguer, who addressed a large Home Rule Rally in Dublin at the end of March 1912. Speaking in Irish, Pearse said he thought that "a good measure can be gained if we have enough courage", but he warned, "Let the English understand that if we are again betrayed, there shall be red war throughout Ireland".

In November 1913 Pearse was invited to the inaugural meeting of the Irish Volunteers—formed in reaction to the creation of the Ulster Volunteers—whose aim was "to secure and maintain the rights and liberties common to the whole people of Ireland". In an article entitled "The Coming Revolution" (November 1913) Pearse wrote:

As to what your work as an Irish Nationalist is to be, I cannot conjecture; I know what mine is to be, and would have you know yours and buckle yourselves to it. And it may be (nay, it is) that your and mine will lead us to a common meeting-place, and that on a certain day we shall stand together, with many more beside us, ready for a greater adventure than any of us has yet had, a trial and a triumph to be endured and achieved in common.

The Home Rule Bill just failed to pass the House of Lords, but the Lords' diminished power under the Parliament Act 1911 meant that the Bill could only be delayed, not stopped. It was placed on the statute books with Royal Assent in September 1914, but its implementation was suspended for the duration of the First World War.

John Redmond feared that his "national authority" might be circumvented by the Volunteers and decided to try to take control of the new movement. Despite opposition from the Irish Republican Brotherhood, the Volunteer Executive agreed to share leadership with Redmond and a joint committee was set up. Pearse was opposed to this and was to write:

The leaders in Ireland have nearly always left the people at the critical moment; they have sometimes sold them. The former Volunteer movement was abandoned by its leaders; O'Connell recoiled before the cannon at Clontarf; twice the hour of the Irish revolution struck during Young Ireland days and twice it struck in vain, for Meagher hesitated in Waterford, Duffy and McGee hesitated in Dublin. Stephens refused to give the word in '65; he never came in '66 or '67. I do not blame these men; you or I might have done the same. It is a terrible responsibility to be cast on a man, that of bidding the cannon speak and the grapeshot pour.

The Volunteers split, one of the issues being support for the Allied and the British war effort. A majority followed Redmond into the National Volunteers in the belief that this would ensure Home Rule on their return. Pearse, exhilarated by the dramatic events of the European war, wrote in an article in December 1915:

It is patriotism that stirs the people. Belgium defending her soil is heroic, and so is Turkey . . . . . .

It is good for the world that such things should be done. The old heart of the earth needed to be warmed with the red wine of the battlefields.

Such august homage was never before offered to God as this, the homage of millions of lives given gladly for love of country.

War is a terrible thing, and this is the most terrible of wars. But this war is not more terrible than the evils which it will end or help to end.

Irish Republican Brotherhood

In December 1913 Bulmer Hobson swore Pearse into the secret Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), an organisation dedicated to the overthrow of British rule in Ireland and its replacement with an Irish Republic. He was soon co-opted onto the IRB's Supreme Council by Tom Clarke. Pearse was then one of many people who were members of both the IRB and the Volunteers. When he became the Volunteers' Director of Military Organisation in 1914 he was the highest ranking Volunteer in the IRB membership, and instrumental in the latter's commandeering of the remaining minority of the Volunteers for the purpose of rebellion. By 1915 he was on the IRB's Supreme Council, and its secret Military Council, the core group that began planning for a rising while war raged on the European Western Front.

On 1 August 1915 Pearse gave a graveside oration at the funeral of the Fenian Jeremiah O'Donovan Rossa. He was the first republican to be filmed giving an oration. It closed with the words:

Our foes are strong and wise and wary; but, strong and wise and wary as they are, they cannot undo the miracles of God who ripens in the hearts of young men the seeds sown by the young men of a former generation. And the seeds sown by the young men of '65 and '67 are coming to their miraculous ripening today. Rulers and Defenders of the Realm had need to be wary if they would guard against such processes. Life springs from death; and from the graves of patriot men and women spring living nations. The Defenders of this Realm have worked well in secret and in the open. They think that they have pacified Ireland. They think that they have purchased half of us and intimidated the other half. They think that they have foreseen everything, think that they have provided against everything; but, the fools, the fools, the fools! – They have left us our Fenian dead, and while Ireland holds these graves, Ireland unfree shall never be at peace. (Full text of Speech)

Easter Rising and death

Main article: Easter RisingIt was Pearse who, on behalf of the IRB shortly before Easter in 1916, issued the orders to all Volunteer units throughout the country for three days of manoeuvres beginning on Easter Sunday, which was the signal for a general uprising. When Eoin MacNeill, the Chief of Staff of the Volunteers, learned what was being planned without the promised arms from Germany, he countermanded the orders via newspaper, causing the IRB to issue a last-minute order to go through with the plan the following day, greatly limiting the numbers who turned out for the rising.

When the Easter Rising eventually began on Easter Monday, 24 April 1916, it was Pearse who read the Proclamation of the Irish Republic from outside the General Post Office, the headquarters of the Rising. Pearse was the person most responsible for drafting the Proclamation, and he was chosen as President of the Republic. After six days of fighting, heavy civilian casualties and great destruction of property, Pearse issued the order to surrender.

Pearse and fourteen other leaders, including his brother Willie, were court-martialled and executed by firing squad. Thomas Clarke, Thomas MacDonagh and Pearse himself were the first of the rebels to be executed, on the morning of 3 May 1916. Pearse was 36 years old at the time of his death. Roger Casement, who had tried unsuccessfully to recruit an insurgent force among Irish-born prisoners of war from the Irish Brigade in Germany, was hanged in London the following August.

Sir John Maxwell, the Commander-in-Chief, Ireland, sent a telegram to H. H. Asquith, then Prime Minister, advising him not to return the bodies of the Pearse brothers to their family, saying, "Irish sentimentality will turn these graves into martyrs' shrines to which annual processions will be made, which would cause constant irritation in this country." Maxwell also suppressed a letter from Pearse to his mother, and two poems dated 1 May 1916. He submitted copies of them also to Prime Minister Asquith, saying that some of the content was "objectionable".

Writings

Pearse wrote stories and poems in both Irish and English. His best-known English poems include "The Mother", "The Fool", "The Rebel" and "The Wayfarer". He also wrote several allegorical plays in the Irish language, including The King, The Master, and The Singer. His short stories in Irish include Eoghainín na nÉan ("Eoineen of the Birds"), Íosagán ("Little Jesus"), An Gadaí ("The Thief"), Na Bóithre ("The Roads"), and An Bhean Chaointe ("The Keening Woman"). These were translated into English by Joseph Campbell (in the Collected Works of 1917). Most of his ideas on education are contained in his essay "The Murder Machine". He also wrote many essays on politics and language, notably "The Coming Revolution" and "Ghosts".

Pearse is closely associated with his rendering of the Jacobite sean-nós song, "Oró Sé do Bheatha 'Bhaile", for which he composed republican lyrics.

According to Innti poet and literary critic Louis de Paor, despite Pearse's enthusiasm for the Conamara Theas dialect of Connacht Irish spoken around his summer cottage at Rosmuc in Connemara, he chose to follow the usual practice of the Gaelic revival by writing in Munster Irish, which was considered less Anglicized than other Irish dialects.

Also according to Louis de Paor, Pearse's reading of the radically experimental poetry of Walt Whitman and of the French Symbolists led him to introduce Modernist poetry into the Irish language. As a literary critic, Pearse also left behind a very detailed blueprint for the decolonization of Irish literature, particularly in the Irish language.

Louis De Paor writes that Patrick Pearse was "the most perceptive critic and most accomplished poet", of the early Gaelic revival providing "a sophisticated model for a new literature in Irish that would reestablish a living connection with the pre-colonial Gaelic past while resuming its relationship with contemporary Europe, bypassing the monolithic influence of English." For these reasons, de Paor called Pearse's death a catastrophic loss for modern literature in Irish. According to de Paor, this loss only began to be healed during the 1940s by the modernist poetry of Seán Ó Ríordáin, Máirtín Ó Direáin, and Máire Mhac an tSaoi; and by the modernist novels An Béal Bocht by Flann O'Brien and Cré na Cille by Máirtín Ó Cadhain.

Reputation

With the outbreak of conflict in Northern Ireland in 1969, Pearse's legacy was used by the Provisional IRA.

Pearse's ideas have been seen by Seán Farrell Moran as belonging to the context of European cultural history as a part of a rejection of reason by European social thinkers. Additionally, his place within Catholicism, where his orthodoxy was challenged in the early 1970s, has been addressed to suggest that Pearse's theological foundations for his political ideas share in a long-existing tradition in western Christianity.

Former Fianna Fáil Taoiseach Bertie Ahern described Pearse as one of his heroes and displayed a picture of Pearse over his desk in the Department of the Taoiseach.

Pearse's mother Margaret Pearse served as a TD in Dáil Éireann in the 1920s. His sister Margaret Mary Pearse also served as a TD and Senator.

In a 2006 book, psychiatrists Michael Fitzgerald and Antoinette Walker speculated that Pearse had Asperger syndrome. Pearse's apparent "sexual immaturity", and some of his behaviour, has been the subject of comment since the 1970s by historians such as Ruth Dudley Edwards, T. Ryle Dwyer and Seán Farrell Moran, who speculated that he was attracted to young boys. His most recent biographer, Joost Augusteijn, concluded that "it seems most probable that he was sexually inclined this way". Fitzgerald and Walker maintain that there is absolutely no evidence of homosexuality or paedophilia; they allege that Pearse's apparent lack of sexual interest in women, and his "ascetic" and celibate lifestyle are consistent with a diagnosis of high-functioning autism. Cultural historian Elaine Sisson has further said that Pearse's interest in and idealization of young boys needs to be seen in the context of the Victorian era "cult of the boy".

In almost all of Pearse's portraits, he struck a sideways pose, concealing his left side. This was to hide a strabismus or squint in his left eye, which he felt was an embarrassing condition.

Commemoration

- The building in Rathfarnham, on the south side of Dublin, that once housed Pearse's school, St Enda's, is now the Pearse Museum.

- Pearse Street and Pearse Square in Dublin were renamed in 1926 in honour of Pearse and his brother Willie, Pearse Street (previously Great Brunswick Street) being their birthplace. Other Pearse Streets can be found in Athlone, Ballina, Bandon, Cahir, Cavan, Clonakilty (formerly Sovereign Street), Gorey, Kilkenny, Kinsale, Mountmellick, Mullingar, Nenagh and Sallynoggin (where there are also Pearse Park, Avenue, Road and other uses of the name).

- There are Pearse Roads in Ardara, County Donegal, Ballyphehane in Cork (which also has Pearse Place and Square), Bray, Cookstown (County Wicklow), Cork, Cranmore (which also has Pearse Crescent and Terrace), Dublin 16, Enniscorthy, Graiguecullen (County Carlow), Letterkenny, Limerick (which also has Pearse Avenue), Sligo and Tralee

- There are Pearse Parks (residential streets) in Drogheda, Dundalk and Tullamore, and (parkland) on the outskirts of Arklow and in Tralee (the former demesne of Tralee Castle). There are other Pearse Avenues in Carrickmacross, Ennis, Mervue in Galway and Mallow. Carrigtwohill has a Patrick Pearse Place and there is a Pearse Bridge in Terenure. There is a Pearse Brothers Park in Rathfarnham and a Pearse Terrace in Westport.

- Longford has Pearse Drive and Pearse View. Crumlin (Dublin) has a Pearse Memorial Park.

- Ballyheigue has a statue built in commemoration.

- Every February, just before the Annual Irish language Dining celebration at King's Inns, the institution hosts an Irish language debate where a Bonn an Phiarsaigh (the Pearse medal) is awarded to the winner.

Educational institutions

Cullenswood House, the Pearse family home in Ranelagh where Pádraic first founded St Enda's, today houses a primary Gaelscoil (school for education through the Irish language) called Lios na nÓg, part of a community-based effort to revive the Irish language. Crumlin (Dublin) has the Pearse College of Further Education, and there was formerly an Irish language summer school in Gaoth Dobhair called Colaiste an Phiarsaigh. In Rosmuc there is an Irish-medium vocational school, Gairmscoil na bPiarsach. The main lecture hall at the Cadet School in Ireland is named after P.H. Pearse. In September 2014, Gaelcholáiste an Phiarsaigh, a new Irish language medium secondary school, opened its doors for the first time in the former Loreto Abbey buildings, just 1 km from the Pearse Museum in St Endas Park, Rathfarnham. Today Glanmire County Cork boasts the best secondary-level Irish-speaking college in Ireland called Coláiste an Phiarsaigh, which was named in honour and structured around Patrick Pearse's beliefs.

Sports venues and clubs

A number of Gaelic Athletic Association clubs and playing fields in Ireland are named after Pádraic or both Pearses:

- Antrim: Pearse Park, Dunloy; Patrick Pearse's GAC, Belfast

- Armagh: Annaghmore Pearses GFC; Pearse Óg GAC and its grounds, Pearse Óg Park, Armagh

- Cork: CLG Na Piarsaigh, Cork

- Derry: Pádraig Pearse's GAC, Kilrea; Pearse's GFC, Waterside, Derry (defunct)

- Donegal: Pearse's Park, Ardara

- Dublin: Ballyboden St. Enda's GAA (called after Pearse's school); Pearse's GAC, Rathfarnham (defunct)

- Galway: CLG Na Piarsaigh, Ros Muc;Pádraig Pearse's GAC, Ballymacward & Gurteen; Pearse Stadium, Salthill

- Kerry: Dromid Pearses GAC; Kilflynn Pearses HC (defunct)

- Limerick: CLG Na Piarsaigh, Limerick

- Longford: Pearse Park, Longford

- Louth: CPG Na Piarsaigh, Dundalk

- Monaghan: Ballybay Pearse Brothers, and its grounds, Pearse Park

- Roscommon: Pádraig Pearse's GAC

- Tyrone: Pearse Óg GAC, Dregish; Fintona Pearses GAC; and Galbally Pearses GAC, and its grounds, Pearse Park; a defunct club, Leckpatrick Pearse Óg GAC

- Wexford: Naomh Eanna GAA (called after Pearse's school); P.H. Pearse's HC, Enniscorthy (defunct)

- Wicklow: Pearses' Park, Arklow

So also are several outside Ireland:

- Australasia: Pádraig Pearse GAC, Victoria

- London: Brother Pearse's GAC, London

- Scotland: Pearse Park, Glasgow; Pearse Harps HC (defunct)

- Yorkshire: Brothers Pearse GAC, Huddersfield

- North America: Pádraig Pearse GFC, Chicago; Pádraig Pearse GFC, Detroit

There are also soccer clubs named Pearse Celtic FC in Cork and in Ringsend, Dublin; and Liffeys Pearse FC, a south Dublin soccer club formed by the amalgamation of Liffey Wanderers and Pearse Rangers. A Pearse Rangers schoolboy football club remains in existence in Dublin.

Other commemorations

- In 1916 the English composer Arnold Bax, who had met the man, composed a tone poem entitled In Memoriam Patrick Pearse. It received its first public performance in 2008.

- In Belfast the Pearse Club on King Street was wrecked by an explosion in May 1938.

- Westland Row Station in Dublin was renamed Pearse Station in 1966 after the Pearse brothers.

- The silver ten shilling coin minted in 1966 featured the bust of Patrick Pearse. It is the sole Irish coin ever to have featured anyone associated with Irish history or politics.

- In Ballymun the Patrick Pearse Tower was named after him. It was the first of Ballymun's tower blocks to be demolished in 2004.

- In 1999 the centenary of Pearse's induction as a member of the Gorsedd at the 1899 Pan Celtic Eisteddfod in Cardiff (when he took the Bardic name Areithiwr) was marked by the unveiling of a plaque at the Consulate General of Ireland in Wales.

- Postage stamps commemorating Pearse were issued by the Irish postal service in 1966, 1979 and 2008.

- Writer Prvoslav Vujcic is nicknamed Pearse after Patrick Pearse.

- In 2016 Leinster GAA inaugurated a Pearse medal in recognition of Pearse's role as vice president of the province's Colleges' Committee. The medals are awarded to the best footballer and hurler in the Leinster senior championship each year.

Citations

- Thornley, David (Autumn–Winter 1971). "Patrick Pearse and the Pearse Family". Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review. 60 (239/240). Dublin: Irish Province of the Society of Jesus: 332–346. ISSN 0039-3495. JSTOR 30088734.

- Miller, Liam (1977). The noble drama of W.B. Yeats. Dublin: Dolmen Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-391-00633-1. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- Casey, Christine (2005). Dublin: the city within the Grand and Royal Canals and the Circular Road with the Phoenix Park. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-300-10923-8. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 3 October 2020.