| Revision as of 07:36, 4 June 2005 editFabartus (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users21,651 edits Adjusted PIC position in text + War cause text edits ~~~~← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 22:05, 23 October 2024 edit undoMonkbot (talk | contribs)Bots3,695,952 editsm Task 20: replace {lang-??} templates with {langx|??} ‹See Tfd› (Replaced 2);Tag: AWB | ||

| (459 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Battle of the Russo-Japanese war}} | |||

| {{Battlebox| | |||

| {{About|the land battle|the naval battle|Battle of Port Arthur|the First Sino-Japanese War battle in 1894|Battle of Lushunkou}} | |||

| battle_name=Siege of Port Arthur | |||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=May 2019}} | |||

| |campaign=Russo-Japanese War | |||

| {{More citations needed|date=November 2010}} | |||

| |colour_scheme=background:#ffff99;color:#2222cc | |||

| {{Infobox military conflict | |||

| |image= | |||

| | conflict = Siege of Port Arthur | |||

| |caption= | |||

| | |

| partof = the ] | ||

| |image=RusShellJapLine1905.jpg | |||

| |date=], ] to ], ] | |||

| |image_size=300px | |||

| |place=Near ], ] | |||

| |caption=Russian 500-pound shell bursting near the Japanese siege guns, near Port Arthur | |||

| |result=] Japanese Victory | |||

| | date = August 1, 1904 – January 2, 1905<br>({{Age in months, weeks and days|month1=08|day1=01|year1=1904|month2=01|day2=02|year2=1905}}) | |||

| |combatant1=] | |||

| | place = Port Arthur (modern ], ]) | |||

| |combatant2=] | |||

| |result= Japanese victory | |||

| |commander1=Nogi | |||

| |combatant1={{flag|Empire of Japan}} | |||

| |commander2=Stoessel | |||

| |combatant2={{flag|Russian Empire}} | |||

| |strength1=? | |||

| |commander1={{nowrap|{{Flagdeco|Empire of Japan|army}} ''']'''<br>{{Flagdeco|Empire of Japan|army}} ]<br>{{Flagdeco|Empire of Japan|army}} ]<br>{{Flagdeco|Empire of Japan|army}} ]<br>{{flagicon|Empire of Japan|naval}} ]}} | |||

| |strength2=40,000 | |||

| |commander2={{nowrap|{{flagicon|Russian Empire}} ''']'''{{surrendered}}<br>{{flagicon|Russian Empire}} ''']'''{{KIA}}<br>{{flagicon|Russian Empire}} ]{{surrendered}}<br>{{flagicon|Russian Empire}} ]{{surrendered}}<br>{{flagicon|Russian Empire}} ]{{surrendered}}}} | |||

| |casualties1=57,780 | |||

| |strength1=201,000{{Bulletedlist | |||

| |casualties2=31,306 | |||

| |150,000 troops | |||

| |}} | |||

| |51,000 reserves}} | |||

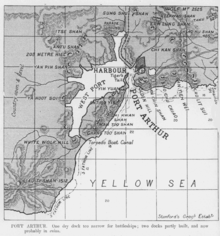

| The '''Siege of ]''' (''] ]-] ]''), the ]n deepwater port and naval base at the tip of the ] (See Map below the Battlebox) in ] was one of the longest and most vicious battles during the ]. The Japanese were determined to capture the Russian port, leased from China in ] and deny the Russians their only '''ice-free''' naval base in the Far East. This war was caused by the leasing of this port, and ] Province, by the weak Chinese government to the Russians after the region had been captured by the Japanese during the ] and confirmed in the ]. But the conditions imposed by Japan on China led to the ] of Russia, France, and Germany just three days after the treaty. They demanded that Japan withdraw its claim on the Liaotung peninsula, concerned that Port Arthur would fall under Japanese control. At the outbreak of the war, the port was serviced by a newly built single tracked spur line of the ] the mainline of which terminated in the ice-plauged Russian port of ], consequently, the Tsar was equally determined that the Russian forces (Land and Sea) should hold. The Russian garrison, about 40,000 strong, commanded by Major-General ] ] had began to prepare their defenses as the Japanese dispatched the Third Army, about 90,000 strong, plus reinforcements, under the command of General Baron ] to begin their advance towards the port starting on ], ]. | |||

| 474 artillery pieces | |||

| |strength2=101,000{{Bulletedlist | |||

| |50,000 troops | |||

| |44,000 volunteers | |||

| |12,000 sailors | |||

| |7,000 recruits}} | |||

| 506 artillery pieces | |||

| |casualties2=55,675{{Bulletedlist | |||

| |31,306 army casualties<ref name=Clodfelter648/> | |||

| |24,369 captured<ref name=Clodfelter648/>}} | |||

| Entire fleet lost<ref name=Clodfelter648/> | |||

| |casualties1=91,549{{Bulletedlist | |||

| |57,780 army casualties<ref name=Clodfelter648/> | |||

| |33,769 sick<ref name=Clodfelter648/>}} | |||

| 16 warships lost including 2 battleships and 4 cruisers<ref name=Clodfelter648/> | |||

| | campaignbox = | |||

| {{Campaignbox Russo-Japanese War}} | |||

| }} | |||

| ] | |||

| The '''siege of Port Arthur''' ({{langx|ja|旅順攻囲戦}}, ''Ryojun Kōisen''; {{langx|ru|link=no|Оборона Порт-Артура}}, ''Oborona Port-Artura'', August 1, 1904 – January 2, 1905) was the ] land battle of the ]. | |||

| Stoessel delayed Nogi for over two months in vicious fighting to give the engineers and garrison troops to prepare the defenses which included deep-dug infantry trenches, supported with barbed wire, machine gun pits, and 506 heavy artillery guns. When Stoessel was forced with withdraw to Port Arthur on July 30, Nogi then set up the Third Army around the town, backed by 474 artillery guns, to begin an intense bombardment of the Russian defenses. By August 9th, the Russian Fleet, threatened by the artillery, felt it necessary to quit Port Arthur and attempt to make Vladivostok. This resulted in the related naval ] on August 10th. Between August 19 and November 26, Nogi treated his army as cannon fodder in three separate and prolonged major frontal attacks against the Russian defenses. All of them were beaten back with heavy casualties. Even night attacks ended in dreadful casualties as the Russians used powerful searchlight batteries to illuminate the storming parties for the artillery gunners. | |||

| ], the deep-water port and Russian naval base at the tip of the ] in ], had been widely regarded as one of the most strongly fortified positions in the world. However, during the ], ] had taken the city from the forces of ] in only a few days. The ease of his victory during the previous conflict, and overconfidence by the Japanese ] in its ability to overcome improved Russian fortifications, led to a much longer campaign and far greater losses than expected. | |||

| As the fighting progressed, all the technology of modern war was pressed into action at Port Arthur from massive 11-inch howitzers capable of hurling 500-lb shells over five miles, as well as rapid firing light ]s, Maxim machine guns, bolt-action magazine rifles, barbed wire entanglements, even hand grenades.<br> | |||

| {{ZHdot|Dalian}} | |||

| <br> | |||

| After the failure of the last big Japanese attack on ], which left over 10,000 Japanese troops killed or wounded in just 15 hours of fighting, Nogi reluctantly decided that Port Arthur would not fall under massive frontal assaults and settled down to siege techniques. | |||

| The siege of Port Arthur saw the introduction of much technology used in subsequent wars of the 20th century (particularly in ]) including massive ]s that fired {{convert|217|kg|adj=on|abbr=off}} shells with a range of {{convert|8|km|abbr=off|sp=us}}, rapid-firing light ], ], bolt-action magazine rifles, ] entanglements, ]s, ], ], ] (and, in response, the first military use of ]), ]s, extensive ], and the use of modified ]s as land weapons. | |||

| Under pressure from Tokyo, Nogi turned his attention to 203 Meter Hill, the highest point of ground in the Russian defense line. None of the Japanese positions afforded unobstructed observation of the harbor or town so the Japanese artillery could not be accurately directed against the port. '''203 Meter Hill''' (so-called because of its height above sea-level) located about three miles north of Port Arthur and part of the Russian outer defense system, offered the best view which Japanese artillery spotters could offer the guns the exact points where the guns should direct their fire. Starting on ], Nogi had his engineers, called sappers or saps, dig siege trenches from the nearby hill, called Akasakayama, towards 203 Meter Hill, as the Japanese launched more attacks on the hill using hand-grenades and bayonet-fixed rifles. Japanese artillery poured more than 4,000 rounds on the Russian positions, which were manned by about 5,000 men. | |||

| ==Background== | |||

| <div style="float:right; width:311px;padding:8px; margin-left:1em; text-align:center">] | |||

| The ] manning the defenses of Port Arthur under Major-General ] ] consisted of almost 50,000 men including the crews of the Russian warships in port (the total population of Port Arthur at the time was around 87,000) and 506 guns. He also had the option of removing the guns from the fleet to bolster the land defenses. | |||

| <br>''Russian 500 pound shell bursting near the Japanese siege guns, near Port Arthur'' | |||

| <br> | |||

| ] | |||

| </div> | |||

| Russian improvements to the defences of Port Arthur included a multi-perimeter layout with overlapping fields of fire and making the best possible use of the natural terrain. However, many of the ]s and fortifications were still unfinished, as considerable resources were either in very short supply or had been diverted to improving the fortifications at ], further north on the ]. | |||

| Diversionary attacks around the Port Arthur perimeter prevented the Russians of 203 Meter Hill from being relived with reinforcements. By ], with the Russians down to only 1,000 men, most of them wounded, fresh Japanese troops launched one final attack at dawn on the hill and it fell by mid-afternoon. | |||

| The outer defense perimeter of Port Arthur consisted of a line of hills, including Hsiaokushan and Takushan near the Ta-ho River in the east, and Namakoyama, Akasakayama, 174-Meter Hill, ] and False Hill in the west. All of these hills were heavily fortified. Approximately {{convert|1.5|km|abbr=off|sp=us}} behind this defensive line was the original stone Chinese wall, which encircled the Old Town of Lushun from the south to the Lun-ho River at the northwest. The Russians had continued the line of the Chinese wall to the west and south, enclosing the approaches to the harbor and the New Town of Port Arthur with concrete forts, machine gun emplacements, and connecting trenches. | |||

| For General Maresuke Nogi, the cost to capture 203 Meter Hill was costly indeed when his last surviving son, a soldier among the attack force, was killed in action on that day during the assault. It was only the intervention of the Emperor that prevented an emotionally shattered Nogi from committing ritual suicide, or ]. The whole operation from November 27 to ] cost Nogi over 8,000 troops, but he had finally had the observation post he so desperately needed. | |||

| General Stoessel withdrew to Port Arthur on July 30, 1904. Facing the Russians was the ], about 150,000 strong, backed by 474 artillery guns, under the command of General ] ]. | |||

| By the end of that day, Japanese artillery had begun a three-day bombardment of the Port Arthur harbor; most of the Russian warships there were already heavily damaged during the (naval) ] which opened the hostilities and had been unable to flee back on the August 10th breakout; these were sunk at their moorings. | |||

| ==Battles== | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ===Battle of the Orphan Hills=== | |||

| After nearly another month of artillery bombardments, Stoessel decided, on humanitarian rather than military grounds, that the garrison should surrender rather than subject the troops and the civilian population, both Russian and Chinese, to further misery and bloodshed. A cease-fire was order on December 30, and after a few days of negotiations, Nogi accepted the Russian surrender on ], ]. | |||

| The shelling of Port Arthur began on August 7, 1904, by a pair of land-based {{convert|4.7|in|mm|adj=on}} guns, and was carried on intermittently until August 19, 1904. The ] also participated in shore bombardment, while in the northeast the army prepared to attack the two semi-isolated hills protruding from the outer defense perimeter: {{convert|600|ft|m|adj=on}} high Takushan (Big Orphan Hill) and the smaller Hsuaokushan (Little Orphan Hill). These hills were not heavily fortified, but had steep slopes and were fronted by the Ta River, which had been dammed by the Russians to provide a stronger obstacle. The hills commanded a view over almost a kilometer of flat ground to the Japanese lines, and it was thus essential for the Japanese to take these hills to complete their encirclement of Port Arthur. | |||

| After pounding the two hills from 04:30 until 19:30, General Nogi launched a frontal ] assault, which was hampered by heavy rain, poor visibility and dense clouds of smoke. The Japanese were able to advance only as far as the forward slopes of both hills, and many soldiers drowned in the Ta River. Even night attacks suffered unexpectedly high casualties, as the Russians used powerful ]s to expose the attackers to ] and machine-gun cross-fire. | |||

| The costs of the siege were terrible; out of the 40,000 strong Russian garrison, about 31,306 men had been killed, wounded or captured before the surrender. The Japanese casualties were later listed as 57,780 killed, wounded or missing. | |||

| Undeterred, Nogi resumed artillery bombardment the following day, August 8, 1904, but his assault stalled again, this time due to heavy fire from the Russian fleet led by the cruiser ]. Nogi ordered his men to press on regardless of casualties. Despite some confusion in orders behind the Russian lines, which led to some units abandoning their posts, numerous Russian troops held on tenaciously. The Japanese finally managed to overrun the Russian positions mostly through sheer superiority in numbers. Takushan was captured at 20:00, and the following morning, August 9, 1904, Hsiaokushan also fell to the Japanese. | |||

| ] (], '']'', 1904)]] | |||

| Gaining these two hills cost the Japanese 1,280 killed and wounded. The ] complained bitterly to the Navy about the ease with which the Russians were able to obtain naval fire support; in response the Japanese Navy brought in a battery of 12-pounder guns, with a range sufficient to ensure that there would be no recurrence of a Russian naval sortie. | |||

| The loss of the two hills, when reported to ], caused him to consider the safety of the ] trapped at Port Arthur, and he sent immediate orders to Admiral ], in command of the fleet after the death of Admiral ], to join the squadron at ]. Vitgeft put to sea at 08:30 on August 10, 1904, and engaged the waiting Japanese under Admiral ] in what was to become known as the ]. | |||

| On August 11, 1904, the Japanese sent an offer of temporary cease-fire to Port Arthur, so the Russians could allow all non-combatants to leave under guarantee of safety. The offer was rejected, but the foreign military observers all decided to leave for safety on August 14, 1904. | |||

| ===Battle of 174 Meter Hill=== | |||

| At noon on August 13, 1904, General Nogi launched a ] ] from the Wolf Hills, which the Russians unsuccessfully attempted to shoot down. Nogi was reportedly very surprised at the lack of coordination of the Russian artillery efforts, and he decided to proceed with a direct frontal assault down the Wantai Ravine, which, if successful, would carry Japanese forces directly into the heart of the city. Given his previous high casualty rate and his lack of heavy artillery, the decision created controversy in his staff; however, Nogi was under orders to take Port Arthur as quickly as possible. | |||

| After sending an immediately refused message to the garrison of Port Arthur demanding surrender, the Japanese began their assault at dawn on August 19, 1904. The main thrust was directed at 174 Meter Hill, with flanking and diversionary attacks along the line from Fort Sung-shu to the Chi-Kuan Battery. The Russian defensive positions on 174 Meter Hill itself were held by the 5th and 13th East Siberian Regiments, reinforced by sailors, under the command of Colonel ], a veteran of the ]. | |||

| Just as he had done at the Battle of Nanshan, Tretyakov, despite having his first line of trenches overrun, tenaciously refused to retreat and held control of 174 Meter Hill despite severe and mounting casualties. On the following day, August 20, 1904, Tretyakov asked for reinforcements but, just as at Nanshan, none were forthcoming. With more than half of his men killed or wounded and with his command disintegrating as small groups of men fell back in confusion, Tretyakov had no choice but to withdraw, and 174 Meter Hill was overrun by the Japanese; it had cost the Japanese some 1,800 killed and wounded, and the Russians over 1,000. | |||

| The assaults on the other sections of the Russian line had also cost the Japanese heavily, but with no results and no ground gained. When Nogi finally called off his attempt to penetrate the Wantai Ravine on August 24, 1904, he had only 174 Meter Hill and the West and East Pan-lung to show for his loss of more than 16,000 men. With all other positions remaining firmly under Russian control, Nogi at last decided to abandon frontal assaults in favor of a protracted ]. | |||

| On August 25, 1904, the day after Nogi's last assault had failed, Marshal ] engaged the Russians under General ] at the ]. | |||

| ===Siege=== | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| Having failed to penetrate the Port Arthur fortifications by direct assault, Nogi now ordered ] to construct trenches and tunnels under the Russian forts in order to explode ] to bring down the walls. By now, Nogi had also been reinforced by additional artillery and 16,000 more troops from Japan, which partially compensated for the casualties sustained in his first assaults. However, the major new development was the arrival of the first battery of huge {{convert|11|in|mm|adj=on}} ]s, replacing those lost when the transport '']'', loaded with a battalion of the First Reserve Regiment of the Guards, was sunk by Russian cruisers on June 15, 1904. The massive 11-inch howitzers could throw a 227-kilogram (500.4-pound) shell over 9 kilometers (5.6 miles), and Nogi at last had the firepower necessary to make a serious attempt against the Russian fortifications. The huge shells were nicknamed "roaring trains" by the Russian troops (for the sound they made just before impact), and during the guns' period at Port Arthur over 35,000 of these shells were fired. The ] howitzers had originally been installed in shore batteries in forts overlooking ] and ], and had been intended for anti-ship operations. | |||

| While the Japanese set to work in the sapping campaign, General Stoessel continued to spend most of his time writing complaining letters to the Tsar about lack of cooperation from his fellow officers in the navy. The garrison in Port Arthur was starting to experience serious outbreaks of ] and ] due to the lack of fresh food. | |||

| Nogi now shifted his attention to the Temple Redoubt and the Waterworks Redoubt (also known as the Erhlung Redoubt) to the east, and to 203 Meter Hill and Namakoyama to the west. Strangely, at this time neither Nogi nor Stoessel seem to have realized the strategic importance of 203 Meter Hill: its unobstructed views of the harbor would have enabled the Japanese to control the harbor and to fire on the Russian fleet sheltering there. This fact was only brought to Nogi's attention when he was visited by General ], who immediately saw that the hill was the key to the whole Russian defense.{{dubious|date=February 2014}} | |||

| By mid-September the Japanese had dug over eight kilometers (5 miles) of trenches and were within 70 meters (230 feet) of the Waterworks Redoubt, which they attacked and captured on September 19, 1904. Thereafter they successfully took the Temple Redoubt, while another attacking force was sent against both Namakoyama and 203 Meter Hill. The former was taken that same day, but on 203 Meter Hill the Russian defenders cut down the dense columns of attacking troops with machine-gun and cannon fire. The attack failed, and the Japanese were forced back, leaving the ground covered with their dead and wounded. The battle at 203 Meter Hill continued for several more days, with the Japanese gaining a foothold each day, only to be forced back each time by Russian counter-attacks. By the time General Nogi abandoned the attempt, he had lost over 3,500 men. The Russians used the respite to begin further strengthening the defenses on 203 Meter Hill, while Nogi began a prolonged artillery bombardment of the town and those parts of the harbor within range of his guns. | |||

| Nogi attempted yet another mass "human wave" assault on 203 Meter Hill on October 29, 1904 intending the hill to be a present for the ] birthday. However, aside from seizing some minor fortifications, the attack failed after six days of hand-to-hand combat, leaving Nogi with the deaths of an additional 124 officers and 3,611 men and no victory. | |||

| The onset of winter did little to slow the intensity of the battle. Nogi received additional reinforcements from Japan, including 18 more Armstrong {{convert|11|in|mm|adj=on}} howitzers, which were manhandled from the railway by teams of 800 soldiers along an eight-mile (13 km)-long narrow gauge track that had been laid expressly for that purpose. These howitzers were added to the 450 other guns already in place. One innovation of the campaign was the centralization of the Japanese fire control, with the artillery batteries connected to the field headquarters by miles of telephone lines. | |||

| Now well aware that the Russian Baltic Fleet was on its way, the Japanese Imperial Headquarters fully understood the necessity of destroying what Russian ships were still serviceable at Port Arthur. It thus became essential that 203 Meter Hill be captured without further delay, and political pressure began to mount for Nogi's replacement. | |||

| ===Battle of 203 Meter Hill=== | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| The highest elevation within Port Arthur, designated "203 Meter Hill", overlooked the harbor. The name "203-Meter Hill" is a misnomer, as the hill consists of two peaks (203 meters and 210 meters high, and 140 meters apart) connected by a sharp ridge. It was initially unfortified; however, after the start of the war the Russians realized its critical importance and built a strong defensive position.<ref name= Kowner>Kowner, '' Historical Dictionary of the Russo-Japanese War'', p. 400.</ref> As well as the natural strength of its elevated position with steep sides, it was protected by a massive redoubt and two earth-covered keeps reinforced by steel rails and timber, and completely surrounded by electrified barbed wire entanglements. It was also connected to the neighboring strongholds on False Hill and Akasakayama by trenches. On top of the lower peak was the fortified Russian command post in reinforced concrete. The Russian defenders entrenched on the 203-meter summit were commanded by Colonel Tretyakov, and were organized into five companies of infantry with machine gun detachments, a company of engineers, a few sailors and a battery of artillery.<ref name=Jukes>Jukes, '' The Russo-Japanese War 1904–1905''. p. 59–60.</ref> | |||

| On September 18, Japanese General Kodama visited General Nogi for the first time, and drew his attention to the strategic importance of 203 Meter Hill.<ref name= Connaughton>Connaughton, '' Rising Sun and Tumbling Bear''. p. 230–246.</ref> | |||

| Nogi directed the first infantry assault against the hill on September 20,<ref name= Kowner /> but found its fortifications impenetrable to Japanese artillery and was forced to retreat by September 22 with over 2500 casualties.<ref name= Connaughton /> He then resumed his attempts to break through the fortifications at Port Arthur in other locations, cumulating in a six-day general assault at the end of October, which cost the Japanese a further 124 officers and 3611 men.<ref name= Connaughton /> News of this defeat inflamed Japanese popular opinion against Nogi. General Yamagata Aritomo urged his ], but Nogi was saved from this only through the unprecedented personal intervention of ]. However, Field Marshal ] found the continuing unavailability of the 3rd Army's manpower to be intolerable, and sent General ] to compel Nogi to take drastic action, or else relieve him of command. Kodama returned to visit Nogi again in mid-November, but decided to give him one last chance.<ref name=Warner>Warner, '' The Tide at Sunrise '', p. 428–432.</ref> After arduous sapping work and an artillery assault with the new Armstrong 11-inch siege guns, mines were exploded underneath some of the Russian fortifications on the main defense perimeter from November 17–24, with a general assault planned for the night of November 26. Coincidentally, this was the same day that the Russian Baltic Fleet was entering the Indian Ocean. The assault contained a ] attack by 2600 men (including 1200 from the newly arrived ]) led by General ],<ref name= Warner /> but the attack failed, with direct frontal assaults on both Fort Erhlung and Fort Sungshu once again beaten back by the Russian defenders. Japanese casualties were officially 4,000 men, but unofficially perhaps twice as high.<ref name= Connaughton /> Russian General ] took the precaution of stationing snipers to ]. | |||

| At 08:30 on November 28, with massive artillery support, Japanese troops again attempted an assault up the sides of both Akasakayama and 203 Meter Hill. Over a thousand {{convert|500|lb|abbr=on}} shells from the {{convert|11|in|mm|adj=on}} howitzers were fired in a single day to support this attack. The Japanese reached as far as the Russian line of barbed wire entanglements by daybreak and held their ground throughout the following day, November 29, while their artillery kept the defenders busy by a continuous bombardment. Nonetheless, the Japanese forces suffered serious losses, as the Russian defenders were well positioned to use ]s and machine guns against the tightly packed mass of Japanese soldiers. On November 30, a small party of Japanese succeeded in planting the Japanese flag at the summit of the hill, but by the morning of December 1, the Russians had successfully counterattacked. Still retaining the authority to replace Nogi if necessary, Kodama assumed temporary command of the Japanese front-line forces, but officially maintained the despondent Nogi in nominal command.<ref name= Connaughton /> | |||

| The battle continued throughout the following days with very heavy hand-to-hand combat with control of the summit changing hands several times. Finally, at 10:30 on December 5, following another massive artillery bombardment during which Russian Colonel Tretyakov was severely wounded, the Japanese managed to overrun 203 Meter Hill, finding only a handful of defenders still alive on the summit. The Russians launched two counter-attacks to retake the hill, both of which failed, and by 17:00, 203 Meter Hill was securely under Japanese control. | |||

| For Japan, the cost of capturing this landmark was great, with over 8,000 dead and wounded in the final assault alone, including most of the IJA 7th Division.<ref name=Jukes/> For Nogi, the cost of capturing 203 Meter Hill was made even more poignant when he received word that his last surviving son had been killed in action during the final assault on the hill. The Russians, who had no more than 1,500 men on the hill at any one time, lost over 6,000 killed and wounded.<ref name= Connaughton /> | |||

| ===Destruction of the Russian Pacific fleet=== | |||

| ] | |||

| ] with Imperial Russian leaders. From left, Ambassador to China, ]; Ambassador to Japan, ]; Minister of Navy, ]; Minister of Army, ]: Interior Minister, ]; Foreign Minister, ]; Prince ]; Finance Minister, ]; Viceroy ].]] | |||

| With a ] on a phone line at the vantage point on 203 Meter Hill overlooking Port Arthur harbor, Nogi could now bombard the ] with heavy {{convert|11|in|mm|adj=on}} howitzers with 500-pound (~220 kg) armor-piercing shells. He started systematically sinking the Russian ships within range. | |||

| On December 5, 1904, the ] ] was sunk, followed by the battleship ] on December 7, 1904, and the battleships ] and ] and the cruisers ] and ] on December 9, 1904. The battleship ], although hit 5 times by the howitzer shells, managed to move out of range of the guns. Stung by the Russian Pacific Fleet having been sunk by the army and not by the Imperial Japanese Navy, and with a direct order from Tokyo that the ''Sevastopol'' was not to be allowed to escape, Admiral Togo sent in wave after wave of ]s in six separate attacks on the sole remaining Russian battleship. After 3 weeks, the ''Sevastopol'' was still afloat, having survived 124 ]es fired at her while sinking two Japanese destroyers and damaging six other vessels. The Japanese had meanwhile lost the cruiser ] to a mine outside the harbor. | |||

| On the night of January 2, 1905, after Port Arthur surrendered, Captain ] of the ''Sevastopol'' had the crippled battleship scuttled in {{convert|30|fathom|m|lk=on}} of water by opening the sea cocks on one side, so that the ship would sink on its side and could not be raised and salvaged by the Japanese. The other six ships were eventually raised and ] into the Imperial Japanese Navy. | |||

| <gallery> | |||

| File:Fire of the Oil Depot Caused by Our Gunfire.jpg|] under fire as the Oil Depot burns | |||

| File:Pallada and Pobeda.jpg|right|''Pallada'' and ] | |||

| File:Port Arthur from Gold Hill.jpg|Wrecked ships of the Russian Pacific Fleet, which were later salvaged by the Japanese navy | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| ===Surrender=== | |||

| {{Wikisource|The New York Times/Nogi and Stoessel meet|Nogi and Stoessel meet}} | |||

| ] | |||

| Following the loss of the Pacific Fleet, the rationale for holding onto Port Arthur was questioned by Stoessel and ] in a council on December 8, 1904, but the idea of surrender was rejected by the other senior officers. Japanese trench and ] continued. With the death of General Kondratenko on December 15, 1904, at Fort ], Stoessel appointed the incompetent Fok in his place. On December 18, 1904, the Japanese exploded an 1,800-kilogram (3,968-pound) mine under Fort Chikuan, which fell that night. On December 28, 1904, Fort Erhlung was also undermined and destroyed. | |||

| ], '']'', 1905).]] | |||

| On December 31, 1904, a series of mines were exploded under Fort Sungshu, the sole surviving major fortress, which surrendered that day. On January 1, 1905, Wantai finally fell to the Japanese. On the same day, Stoessel and Fok sent a message to a surprised General Nogi, offering to surrender. None of the other senior Russian staff had been consulted, and notably Smirnov and Tretyakov were outraged. The surrender was accepted and signed on January 5, 1905, in the northern suburb of ]. | |||

| With this, the Russian garrison was taken into captivity. Civilians were allowed to leave, and the Russian officers were given the choice of either going into ]s with their men or being given ] on taking no further part in the war. | |||

| The Japanese were astounded to find that a huge store of food and ammunition remained in Port Arthur, which implied that Stoessel had surrendered while still able to hold out for a long time. Stoessel, Fok and Smirnov were ]ed on their return to ]. | |||

| Nogi, after leaving a garrison in Port Arthur, led the surviving bulk of his army of 120,000 men north to join Marshal Oyama at the ]. | |||

| ===Losses=== | |||

| Russian land forces in the course of the siege suffered 31,306 casualties,<ref name=Clodfelter648>Clodfelter, Micheal, ''Warfare and Armed Conflicts, a statistical reference, Volume II 1900–91'', pub McFarland, {{ISBN|0-89950-815-4}} p648.</ref> of whom at least 6,000 were killed.<ref name=Clodfelter648/> Lower figures such as 15,000 killed, wounded, and missing are sometimes claimed.<ref name="Defence1908">{{cite book|last1=Schwarz|first1=Alexis von|last2=Romanovsky |first2=Yuri|title=Оборона Порт-Артура|trans-title=The Defence of Port Arthur|volume=I, II|location=Saint Petersburg|year=1908|language=ru}}</ref> At the end of the siege, the Japanese captured a further 878 army officers and 23,491 other ranks; 15,000 of those captured were wounded. The Japanese also captured 546 guns<ref name=Clodfelter648/> and 82,000 artillery shells.<ref name=Clodfelter648/> In addition the Russians lost their entire fleet based at Port Arthur, which was either sunk or interned. The Japanese captured 8,956 seamen.<ref name=Clodfelter648/> | |||

| The Japanese army casualties were later officially listed as 57,780 casualties (killed, wounded and missing),<ref name=Clodfelter648/> of whom 14,000 were killed.<ref name=Clodfelter648/> In addition 33,769 became sick during the siege (including 21,023 with ]).<ref name=Clodfelter648/> The Japanese navy lost 16 ships in the course of the siege, including two battleships and four cruisers.<ref name=Clodfelter648/> | |||

| There were higher estimates of Japanese army casualties at the time such as 94,000<ref name=Ashmead-Bartlett>''Port Arthur, the siege and capitulation, Volume 1'', Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett, 1906, p. 464.</ref>-110,000<ref name=Defence1908/>{{Page needed|date=August 2017}} killed, wounded, and missing, though these were written without access to the Japanese Medical History of the War. | |||

| ==Aftermath== | |||

| ] "100th anniversary of the heroic defence of Port Arthur" showing the military decoration, the ]]] | |||

| The capture of Port Arthur and the subsequent Japanese victories at the ] and ] gave Japan a dominant military position, resulting in favorable arbitration by U.S. President ] in the ], which ended the war. The loss of the war in 1905 led to major political unrest in Imperial Russia (see: ]). | |||

| At the end of the war, Nogi made a report directly to Emperor Meiji during a '']''. When explaining battles of the siege of Port Arthur in detail, he broke down and wept, apologizing for the 56,000 lives lost in that campaign and asking to be allowed to kill himself in atonement. Emperor Meiji told him that suicide was unacceptable, as all responsibility for the war was due to imperial orders, and that Nogi must remain alive, at least as long as he himself lived.<ref>Keene, Donald. (2005). ''Emperor of Japan, Meiji and his World, 1852–1912'', pp. 712–713. New York: Columbia University Press. {{ISBN|978-0-231-12340-2}}</ref> Nogi and his wife Shizuko committed suicide by ] shortly after the ]'s funeral cortege left the imperial palace on 13 September 1912.<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.battlefieldanomalies.com/port_arthur/06_aftermath.htm | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060824083728/http://www.battlefieldanomalies.com/port_arthur/06_aftermath.htm | archive-date=August 24, 2006 | title=Aftermath }}</ref> | |||

| ], depicting a Japanese ] ]]] | |||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| {{Reflist}} | |||

| *Morris, Edmund. (]) '''''Theodore Rex'''''. ], ] (div. of ],] ISBN: 0-8129-6600-7 | |||

| ===Bibliography=== | |||

| * {{cite book|last=Nørregaard|first=Benjamin Wegner|author-link= Benjamin Wegner Nørregaard|year= 1906 |title= The Great Siege: The Investment and Fall of Port Arthur|url=https://archive.org/details/greatsiegeinves00norrgoog|publisher = ]|location =London}} | |||

| * {{cite book|last=Connaughton|first=Richard|author-link=Richard Connaughton|year=2003|title=Rising Sun and Tumbling Bear|publisher = Cassell|isbn= 0-304-36657-9}} | |||

| * {{cite book|last=Kowner|first=Rotem|author-link=Rotem Kowner|year=2006|title=Historical Dictionary of the Russo-Japanese War|publisher = Scarecrow|isbn= 0-8108-4927-5}} | |||

| * Jukes, Geoffrey. ''The Russo-Japanese War 1904–1905''. Osprey Essential Histories. (2002). {{ISBN|978-1-84176-446-7}}. | |||

| * {{cite book|author=Charles à Court Repington|author-link=Charles à Court Repington|title=The War in the Far East, 1904-1905|url=https://archive.org/details/warinfareast00repigoog|year=1905|publisher=J. Murray}} | |||

| * Sedgwick, F.R. (1909). ''The Russo-Japanese War''. Macmillan. | |||

| * Warner, Peggy. ''The Tide at Sunrise: a history of the Russo-Japanese War, 1904–1905''. Routledge (1974) {{ISBN|0714652563}}. | |||

| * Birolli, Bruno, ''Port-Arthur, 8 février 1904, 5 janvier 1905'', Economica (2015) – French | |||

| * {{cite book|first=Tadayoshi|last= Sakurai|title=Human bullets, a soldier's story of Port Arthur|url=https://archive.org/details/humanbulletsaso01bacogoog|year=1907|publisher=Houghton, Mifflin and company}} | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| {{Commonscatinline}} | |||

| * | |||

| * Lafayette College Library, from the collection of ] | |||

| * ''], May 9, 1905, Page 7 | |||

| * Graham J. Morris (2005) '''' available at battlefieldanomalies.com | |||

| {{Coord|38|48|45|N|121|14|30|E|display=title|type:city}} | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Siege Of Port Arthur}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 22:05, 23 October 2024

Battle of the Russo-Japanese war This article is about the land battle. For the naval battle, see Battle of Port Arthur. For the First Sino-Japanese War battle in 1894, see Battle of Lushunkou.

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Siege of Port Arthur" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (November 2010) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| Siege of Port Arthur | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Russo-Japanese War | |||||||

Russian 500-pound shell bursting near the Japanese siege guns, near Port Arthur | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

201,000

|

101,000

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

91,549

|

55,675

| ||||||

| Russo-Japanese War | |

|---|---|

The siege of Port Arthur (Japanese: 旅順攻囲戦, Ryojun Kōisen; Russian: Оборона Порт-Артура, Oborona Port-Artura, August 1, 1904 – January 2, 1905) was the longest and most violent land battle of the Russo-Japanese War.

Port Arthur, the deep-water port and Russian naval base at the tip of the Liaodong Peninsula in Manchuria, had been widely regarded as one of the most strongly fortified positions in the world. However, during the First Sino-Japanese War, General Nogi Maresuke had taken the city from the forces of Qing China in only a few days. The ease of his victory during the previous conflict, and overconfidence by the Japanese General Staff in its ability to overcome improved Russian fortifications, led to a much longer campaign and far greater losses than expected.

The siege of Port Arthur saw the introduction of much technology used in subsequent wars of the 20th century (particularly in World War I) including massive 28 cm howitzers that fired 217-kilogram (478-pound) shells with a range of 8 kilometers (5.0 miles), rapid-firing light howitzers, Maxim machine guns, bolt-action magazine rifles, barbed wire entanglements, electric fences, arc lamp, searchlights, tactical radio signalling (and, in response, the first military use of radio jamming), hand grenades, extensive trench warfare, and the use of modified naval mines as land weapons.

Background

The Russian forces manning the defenses of Port Arthur under Major-General Baron Anatoly Stoessel consisted of almost 50,000 men including the crews of the Russian warships in port (the total population of Port Arthur at the time was around 87,000) and 506 guns. He also had the option of removing the guns from the fleet to bolster the land defenses.

Russian improvements to the defences of Port Arthur included a multi-perimeter layout with overlapping fields of fire and making the best possible use of the natural terrain. However, many of the redoubts and fortifications were still unfinished, as considerable resources were either in very short supply or had been diverted to improving the fortifications at Dalny, further north on the Liaodong Peninsula.

The outer defense perimeter of Port Arthur consisted of a line of hills, including Hsiaokushan and Takushan near the Ta-ho River in the east, and Namakoyama, Akasakayama, 174-Meter Hill, 203-Meter Hill and False Hill in the west. All of these hills were heavily fortified. Approximately 1.5 kilometers (0.93 miles) behind this defensive line was the original stone Chinese wall, which encircled the Old Town of Lushun from the south to the Lun-ho River at the northwest. The Russians had continued the line of the Chinese wall to the west and south, enclosing the approaches to the harbor and the New Town of Port Arthur with concrete forts, machine gun emplacements, and connecting trenches.

General Stoessel withdrew to Port Arthur on July 30, 1904. Facing the Russians was the Japanese Third Army, about 150,000 strong, backed by 474 artillery guns, under the command of General Baron Nogi Maresuke.

Battles

Blue line: July 30, Red: August 15, Yellow: August 20, Green: January 2

Battle of the Orphan Hills

The shelling of Port Arthur began on August 7, 1904, by a pair of land-based 4.7-inch (120 mm) guns, and was carried on intermittently until August 19, 1904. The Japanese fleet also participated in shore bombardment, while in the northeast the army prepared to attack the two semi-isolated hills protruding from the outer defense perimeter: 600-foot (180 m) high Takushan (Big Orphan Hill) and the smaller Hsuaokushan (Little Orphan Hill). These hills were not heavily fortified, but had steep slopes and were fronted by the Ta River, which had been dammed by the Russians to provide a stronger obstacle. The hills commanded a view over almost a kilometer of flat ground to the Japanese lines, and it was thus essential for the Japanese to take these hills to complete their encirclement of Port Arthur.

After pounding the two hills from 04:30 until 19:30, General Nogi launched a frontal infantry assault, which was hampered by heavy rain, poor visibility and dense clouds of smoke. The Japanese were able to advance only as far as the forward slopes of both hills, and many soldiers drowned in the Ta River. Even night attacks suffered unexpectedly high casualties, as the Russians used powerful searchlights to expose the attackers to artillery and machine-gun cross-fire.

Undeterred, Nogi resumed artillery bombardment the following day, August 8, 1904, but his assault stalled again, this time due to heavy fire from the Russian fleet led by the cruiser Novik. Nogi ordered his men to press on regardless of casualties. Despite some confusion in orders behind the Russian lines, which led to some units abandoning their posts, numerous Russian troops held on tenaciously. The Japanese finally managed to overrun the Russian positions mostly through sheer superiority in numbers. Takushan was captured at 20:00, and the following morning, August 9, 1904, Hsiaokushan also fell to the Japanese.

Gaining these two hills cost the Japanese 1,280 killed and wounded. The Japanese Army complained bitterly to the Navy about the ease with which the Russians were able to obtain naval fire support; in response the Japanese Navy brought in a battery of 12-pounder guns, with a range sufficient to ensure that there would be no recurrence of a Russian naval sortie.

The loss of the two hills, when reported to the Tsar, caused him to consider the safety of the Russian Pacific Fleet trapped at Port Arthur, and he sent immediate orders to Admiral Wilgelm Vitgeft, in command of the fleet after the death of Admiral Stepan Makarov, to join the squadron at Vladivostok. Vitgeft put to sea at 08:30 on August 10, 1904, and engaged the waiting Japanese under Admiral Tōgō Heihachirō in what was to become known as the Battle of the Yellow Sea.

On August 11, 1904, the Japanese sent an offer of temporary cease-fire to Port Arthur, so the Russians could allow all non-combatants to leave under guarantee of safety. The offer was rejected, but the foreign military observers all decided to leave for safety on August 14, 1904.

Battle of 174 Meter Hill

At noon on August 13, 1904, General Nogi launched a photo reconnaissance balloon from the Wolf Hills, which the Russians unsuccessfully attempted to shoot down. Nogi was reportedly very surprised at the lack of coordination of the Russian artillery efforts, and he decided to proceed with a direct frontal assault down the Wantai Ravine, which, if successful, would carry Japanese forces directly into the heart of the city. Given his previous high casualty rate and his lack of heavy artillery, the decision created controversy in his staff; however, Nogi was under orders to take Port Arthur as quickly as possible.

After sending an immediately refused message to the garrison of Port Arthur demanding surrender, the Japanese began their assault at dawn on August 19, 1904. The main thrust was directed at 174 Meter Hill, with flanking and diversionary attacks along the line from Fort Sung-shu to the Chi-Kuan Battery. The Russian defensive positions on 174 Meter Hill itself were held by the 5th and 13th East Siberian Regiments, reinforced by sailors, under the command of Colonel Nikolai Tretyakov, a veteran of the Battle of Nanshan.

Just as he had done at the Battle of Nanshan, Tretyakov, despite having his first line of trenches overrun, tenaciously refused to retreat and held control of 174 Meter Hill despite severe and mounting casualties. On the following day, August 20, 1904, Tretyakov asked for reinforcements but, just as at Nanshan, none were forthcoming. With more than half of his men killed or wounded and with his command disintegrating as small groups of men fell back in confusion, Tretyakov had no choice but to withdraw, and 174 Meter Hill was overrun by the Japanese; it had cost the Japanese some 1,800 killed and wounded, and the Russians over 1,000.

The assaults on the other sections of the Russian line had also cost the Japanese heavily, but with no results and no ground gained. When Nogi finally called off his attempt to penetrate the Wantai Ravine on August 24, 1904, he had only 174 Meter Hill and the West and East Pan-lung to show for his loss of more than 16,000 men. With all other positions remaining firmly under Russian control, Nogi at last decided to abandon frontal assaults in favor of a protracted siege.

On August 25, 1904, the day after Nogi's last assault had failed, Marshal Ōyama Iwao engaged the Russians under General Aleksey Kuropatkin at the Battle of Liaoyang.

Siege

Having failed to penetrate the Port Arthur fortifications by direct assault, Nogi now ordered sappers to construct trenches and tunnels under the Russian forts in order to explode mines to bring down the walls. By now, Nogi had also been reinforced by additional artillery and 16,000 more troops from Japan, which partially compensated for the casualties sustained in his first assaults. However, the major new development was the arrival of the first battery of huge 11-inch (280 mm) siege howitzers, replacing those lost when the transport Hitachi Maru, loaded with a battalion of the First Reserve Regiment of the Guards, was sunk by Russian cruisers on June 15, 1904. The massive 11-inch howitzers could throw a 227-kilogram (500.4-pound) shell over 9 kilometers (5.6 miles), and Nogi at last had the firepower necessary to make a serious attempt against the Russian fortifications. The huge shells were nicknamed "roaring trains" by the Russian troops (for the sound they made just before impact), and during the guns' period at Port Arthur over 35,000 of these shells were fired. The Armstrong howitzers had originally been installed in shore batteries in forts overlooking Tokyo Bay and Osaka Bay, and had been intended for anti-ship operations.

While the Japanese set to work in the sapping campaign, General Stoessel continued to spend most of his time writing complaining letters to the Tsar about lack of cooperation from his fellow officers in the navy. The garrison in Port Arthur was starting to experience serious outbreaks of scurvy and dysentery due to the lack of fresh food.

Nogi now shifted his attention to the Temple Redoubt and the Waterworks Redoubt (also known as the Erhlung Redoubt) to the east, and to 203 Meter Hill and Namakoyama to the west. Strangely, at this time neither Nogi nor Stoessel seem to have realized the strategic importance of 203 Meter Hill: its unobstructed views of the harbor would have enabled the Japanese to control the harbor and to fire on the Russian fleet sheltering there. This fact was only brought to Nogi's attention when he was visited by General Kodama Gentarō, who immediately saw that the hill was the key to the whole Russian defense.

By mid-September the Japanese had dug over eight kilometers (5 miles) of trenches and were within 70 meters (230 feet) of the Waterworks Redoubt, which they attacked and captured on September 19, 1904. Thereafter they successfully took the Temple Redoubt, while another attacking force was sent against both Namakoyama and 203 Meter Hill. The former was taken that same day, but on 203 Meter Hill the Russian defenders cut down the dense columns of attacking troops with machine-gun and cannon fire. The attack failed, and the Japanese were forced back, leaving the ground covered with their dead and wounded. The battle at 203 Meter Hill continued for several more days, with the Japanese gaining a foothold each day, only to be forced back each time by Russian counter-attacks. By the time General Nogi abandoned the attempt, he had lost over 3,500 men. The Russians used the respite to begin further strengthening the defenses on 203 Meter Hill, while Nogi began a prolonged artillery bombardment of the town and those parts of the harbor within range of his guns.

Nogi attempted yet another mass "human wave" assault on 203 Meter Hill on October 29, 1904 intending the hill to be a present for the Meiji Emperor's birthday. However, aside from seizing some minor fortifications, the attack failed after six days of hand-to-hand combat, leaving Nogi with the deaths of an additional 124 officers and 3,611 men and no victory.

The onset of winter did little to slow the intensity of the battle. Nogi received additional reinforcements from Japan, including 18 more Armstrong 11-inch (280 mm) howitzers, which were manhandled from the railway by teams of 800 soldiers along an eight-mile (13 km)-long narrow gauge track that had been laid expressly for that purpose. These howitzers were added to the 450 other guns already in place. One innovation of the campaign was the centralization of the Japanese fire control, with the artillery batteries connected to the field headquarters by miles of telephone lines.

Now well aware that the Russian Baltic Fleet was on its way, the Japanese Imperial Headquarters fully understood the necessity of destroying what Russian ships were still serviceable at Port Arthur. It thus became essential that 203 Meter Hill be captured without further delay, and political pressure began to mount for Nogi's replacement.

Battle of 203 Meter Hill

The highest elevation within Port Arthur, designated "203 Meter Hill", overlooked the harbor. The name "203-Meter Hill" is a misnomer, as the hill consists of two peaks (203 meters and 210 meters high, and 140 meters apart) connected by a sharp ridge. It was initially unfortified; however, after the start of the war the Russians realized its critical importance and built a strong defensive position. As well as the natural strength of its elevated position with steep sides, it was protected by a massive redoubt and two earth-covered keeps reinforced by steel rails and timber, and completely surrounded by electrified barbed wire entanglements. It was also connected to the neighboring strongholds on False Hill and Akasakayama by trenches. On top of the lower peak was the fortified Russian command post in reinforced concrete. The Russian defenders entrenched on the 203-meter summit were commanded by Colonel Tretyakov, and were organized into five companies of infantry with machine gun detachments, a company of engineers, a few sailors and a battery of artillery.

On September 18, Japanese General Kodama visited General Nogi for the first time, and drew his attention to the strategic importance of 203 Meter Hill. Nogi directed the first infantry assault against the hill on September 20, but found its fortifications impenetrable to Japanese artillery and was forced to retreat by September 22 with over 2500 casualties. He then resumed his attempts to break through the fortifications at Port Arthur in other locations, cumulating in a six-day general assault at the end of October, which cost the Japanese a further 124 officers and 3611 men. News of this defeat inflamed Japanese popular opinion against Nogi. General Yamagata Aritomo urged his court-martial, but Nogi was saved from this only through the unprecedented personal intervention of Emperor Meiji. However, Field Marshal Oyama Iwao found the continuing unavailability of the 3rd Army's manpower to be intolerable, and sent General Kodama Gentarō to compel Nogi to take drastic action, or else relieve him of command. Kodama returned to visit Nogi again in mid-November, but decided to give him one last chance. After arduous sapping work and an artillery assault with the new Armstrong 11-inch siege guns, mines were exploded underneath some of the Russian fortifications on the main defense perimeter from November 17–24, with a general assault planned for the night of November 26. Coincidentally, this was the same day that the Russian Baltic Fleet was entering the Indian Ocean. The assault contained a forlorn hope attack by 2600 men (including 1200 from the newly arrived IJA 7th Division) led by General Nakamura Satoru, but the attack failed, with direct frontal assaults on both Fort Erhlung and Fort Sungshu once again beaten back by the Russian defenders. Japanese casualties were officially 4,000 men, but unofficially perhaps twice as high. Russian General Roman Kondratenko took the precaution of stationing snipers to shoot any of his front line troops attempting to abandon their positions. At 08:30 on November 28, with massive artillery support, Japanese troops again attempted an assault up the sides of both Akasakayama and 203 Meter Hill. Over a thousand 500 lb (230 kg) shells from the 11-inch (280 mm) howitzers were fired in a single day to support this attack. The Japanese reached as far as the Russian line of barbed wire entanglements by daybreak and held their ground throughout the following day, November 29, while their artillery kept the defenders busy by a continuous bombardment. Nonetheless, the Japanese forces suffered serious losses, as the Russian defenders were well positioned to use hand grenades and machine guns against the tightly packed mass of Japanese soldiers. On November 30, a small party of Japanese succeeded in planting the Japanese flag at the summit of the hill, but by the morning of December 1, the Russians had successfully counterattacked. Still retaining the authority to replace Nogi if necessary, Kodama assumed temporary command of the Japanese front-line forces, but officially maintained the despondent Nogi in nominal command.

The battle continued throughout the following days with very heavy hand-to-hand combat with control of the summit changing hands several times. Finally, at 10:30 on December 5, following another massive artillery bombardment during which Russian Colonel Tretyakov was severely wounded, the Japanese managed to overrun 203 Meter Hill, finding only a handful of defenders still alive on the summit. The Russians launched two counter-attacks to retake the hill, both of which failed, and by 17:00, 203 Meter Hill was securely under Japanese control.

For Japan, the cost of capturing this landmark was great, with over 8,000 dead and wounded in the final assault alone, including most of the IJA 7th Division. For Nogi, the cost of capturing 203 Meter Hill was made even more poignant when he received word that his last surviving son had been killed in action during the final assault on the hill. The Russians, who had no more than 1,500 men on the hill at any one time, lost over 6,000 killed and wounded.

Destruction of the Russian Pacific fleet

With a spotter on a phone line at the vantage point on 203 Meter Hill overlooking Port Arthur harbor, Nogi could now bombard the Russian fleet with heavy 11-inch (280 mm) howitzers with 500-pound (~220 kg) armor-piercing shells. He started systematically sinking the Russian ships within range.

On December 5, 1904, the battleship Poltava was sunk, followed by the battleship Retvizan on December 7, 1904, and the battleships Pobeda and Peresvet and the cruisers Pallada and Bayan on December 9, 1904. The battleship Sevastopol, although hit 5 times by the howitzer shells, managed to move out of range of the guns. Stung by the Russian Pacific Fleet having been sunk by the army and not by the Imperial Japanese Navy, and with a direct order from Tokyo that the Sevastopol was not to be allowed to escape, Admiral Togo sent in wave after wave of destroyers in six separate attacks on the sole remaining Russian battleship. After 3 weeks, the Sevastopol was still afloat, having survived 124 torpedoes fired at her while sinking two Japanese destroyers and damaging six other vessels. The Japanese had meanwhile lost the cruiser Takasago to a mine outside the harbor.

On the night of January 2, 1905, after Port Arthur surrendered, Captain Nikolai Essen of the Sevastopol had the crippled battleship scuttled in 30 fathoms (55 m) of water by opening the sea cocks on one side, so that the ship would sink on its side and could not be raised and salvaged by the Japanese. The other six ships were eventually raised and recommissioned into the Imperial Japanese Navy.

-

Pallada under fire as the Oil Depot burns

Pallada under fire as the Oil Depot burns

-

Pallada and Pobeda

Pallada and Pobeda

-

Wrecked ships of the Russian Pacific Fleet, which were later salvaged by the Japanese navy

Wrecked ships of the Russian Pacific Fleet, which were later salvaged by the Japanese navy

Surrender

Following the loss of the Pacific Fleet, the rationale for holding onto Port Arthur was questioned by Stoessel and Alexander Fok in a council on December 8, 1904, but the idea of surrender was rejected by the other senior officers. Japanese trench and tunnel warfare continued. With the death of General Kondratenko on December 15, 1904, at Fort Tongchikuan, Stoessel appointed the incompetent Fok in his place. On December 18, 1904, the Japanese exploded an 1,800-kilogram (3,968-pound) mine under Fort Chikuan, which fell that night. On December 28, 1904, Fort Erhlung was also undermined and destroyed.

On December 31, 1904, a series of mines were exploded under Fort Sungshu, the sole surviving major fortress, which surrendered that day. On January 1, 1905, Wantai finally fell to the Japanese. On the same day, Stoessel and Fok sent a message to a surprised General Nogi, offering to surrender. None of the other senior Russian staff had been consulted, and notably Smirnov and Tretyakov were outraged. The surrender was accepted and signed on January 5, 1905, in the northern suburb of Shuishiying.

With this, the Russian garrison was taken into captivity. Civilians were allowed to leave, and the Russian officers were given the choice of either going into prisoner-of-war camps with their men or being given parole conditional on taking no further part in the war.

The Japanese were astounded to find that a huge store of food and ammunition remained in Port Arthur, which implied that Stoessel had surrendered while still able to hold out for a long time. Stoessel, Fok and Smirnov were court-martialed on their return to St Petersburg.

Nogi, after leaving a garrison in Port Arthur, led the surviving bulk of his army of 120,000 men north to join Marshal Oyama at the Battle of Mukden.

Losses

Russian land forces in the course of the siege suffered 31,306 casualties, of whom at least 6,000 were killed. Lower figures such as 15,000 killed, wounded, and missing are sometimes claimed. At the end of the siege, the Japanese captured a further 878 army officers and 23,491 other ranks; 15,000 of those captured were wounded. The Japanese also captured 546 guns and 82,000 artillery shells. In addition the Russians lost their entire fleet based at Port Arthur, which was either sunk or interned. The Japanese captured 8,956 seamen.

The Japanese army casualties were later officially listed as 57,780 casualties (killed, wounded and missing), of whom 14,000 were killed. In addition 33,769 became sick during the siege (including 21,023 with beriberi). The Japanese navy lost 16 ships in the course of the siege, including two battleships and four cruisers.

There were higher estimates of Japanese army casualties at the time such as 94,000-110,000 killed, wounded, and missing, though these were written without access to the Japanese Medical History of the War.

Aftermath

The capture of Port Arthur and the subsequent Japanese victories at the Battle of Mukden and Tsushima gave Japan a dominant military position, resulting in favorable arbitration by U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt in the Treaty of Portsmouth, which ended the war. The loss of the war in 1905 led to major political unrest in Imperial Russia (see: Russian Revolution of 1905).

At the end of the war, Nogi made a report directly to Emperor Meiji during a Gozen Kaigi. When explaining battles of the siege of Port Arthur in detail, he broke down and wept, apologizing for the 56,000 lives lost in that campaign and asking to be allowed to kill himself in atonement. Emperor Meiji told him that suicide was unacceptable, as all responsibility for the war was due to imperial orders, and that Nogi must remain alive, at least as long as he himself lived. Nogi and his wife Shizuko committed suicide by seppuku shortly after the Emperor Meiji's funeral cortege left the imperial palace on 13 September 1912.

References

- ^ Clodfelter, Micheal, Warfare and Armed Conflicts, a statistical reference, Volume II 1900–91, pub McFarland, ISBN 0-89950-815-4 p648.

- ^ Kowner, Historical Dictionary of the Russo-Japanese War, p. 400.

- ^ Jukes, The Russo-Japanese War 1904–1905. p. 59–60.

- ^ Connaughton, Rising Sun and Tumbling Bear. p. 230–246.

- ^ Warner, The Tide at Sunrise , p. 428–432.

- ^ Schwarz, Alexis von; Romanovsky, Yuri (1908). Оборона Порт-Артура [The Defence of Port Arthur] (in Russian). Vol. I, II. Saint Petersburg.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Port Arthur, the siege and capitulation, Volume 1, Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett, 1906, p. 464.

- Keene, Donald. (2005). Emperor of Japan, Meiji and his World, 1852–1912, pp. 712–713. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-12340-2

- "Aftermath". Archived from the original on August 24, 2006.

Bibliography

- Nørregaard, Benjamin Wegner (1906). The Great Siege: The Investment and Fall of Port Arthur. London: Methuen Publishing.

- Connaughton, Richard (2003). Rising Sun and Tumbling Bear. Cassell. ISBN 0-304-36657-9.

- Kowner, Rotem (2006). Historical Dictionary of the Russo-Japanese War. Scarecrow. ISBN 0-8108-4927-5.

- Jukes, Geoffrey. The Russo-Japanese War 1904–1905. Osprey Essential Histories. (2002). ISBN 978-1-84176-446-7.

- Charles à Court Repington (1905). The War in the Far East, 1904-1905. J. Murray.

- Sedgwick, F.R. (1909). The Russo-Japanese War. Macmillan.

- Warner, Peggy. The Tide at Sunrise: a history of the Russo-Japanese War, 1904–1905. Routledge (1974) ISBN 0714652563.

- Birolli, Bruno, Port-Arthur, 8 février 1904, 5 janvier 1905, Economica (2015) – French

- Sakurai, Tadayoshi (1907). Human bullets, a soldier's story of Port Arthur. Houghton, Mifflin and company.

External links

![]() Media related to Siege of Port Arthur at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Siege of Port Arthur at Wikimedia Commons

- The Russo-Japanese War Research Society

- Siege of Port Arthur Stereoviews Lafayette College Library, from the collection of Richard Mammana

- PRISONERS AND SPOILS OF PORT ARTHUR. The Straits Times, May 9, 1905, Page 7

- Graham J. Morris (2005) Port Arthur – The Siege available at battlefieldanomalies.com

38°48′45″N 121°14′30″E / 38.81250°N 121.24167°E / 38.81250; 121.24167

Categories: