| Revision as of 02:56, 4 June 2005 editNo Account (talk | contribs)487 edits →Assassination as military doctrine← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 22:30, 20 January 2025 edit undoClueBot NG (talk | contribs)Bots, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers6,440,291 editsm Reverting possible vandalism by 207.237.17.62 to version by Daddynnoob. Report False Positive? Thanks, ClueBot NG. (4370414) (Bot)Tag: Rollback | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Murder of a prominent person, especially for political or ideological reasons}} | |||

| {{dablink|Assassin redirects here. For other meanings of the word, see ]}} | |||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=December 2021}} | |||

| ] murdered the alleged assassin, ], in a very public manner.]] | |||

| {{Redirect-multi|3|Assassin|Assassinated|Assassinating|other uses|Assassin (disambiguation)|and|Assassination (disambiguation)}} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| {{Homicide}} | |||

| '''Assassination''' is the willful killing, by a sudden, secret, or planned attack, of a person{{Emdash}}especially if ].<ref>{{Cite web |date=2023-06-24 |title=Definition of ASSASSINATION |url=https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/assassination |access-date=2023-06-26 |website=Merriam-Webster |language=en}}</ref><ref>Black's Law Dictionary "the act of deliberately killing someone especially a public figure, usually for money or for political reasons" (''Legal Research, Analysis and Writing'' by William H. Putman and {{cite web |url-status=dead |url=http://hir.harvard.edu/leadership/on-the-offensive |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101206230433/http://hir.harvard.edu/leadership/on-the-offensive|archive-date=December 6, 2010 |website= Harvard International Review |date=May 6, 2006 |first1=Kristen |last1=Eichensehr |title=On the Offensive — Assassination Policy Under International Law }}</ref> It may be prompted by political, ideological, religious, personal, financial, or military ].<ref>{{Citation |title=assassination, n. |date=2023-03-02 |work=Oxford English Dictionary |url=https://oed.com/dictionary/assassination_n |access-date=2024-12-05 |edition=3 |publisher=Oxford University Press |language=en |doi=10.1093/oed/5671820672}}</ref> Assassinations are ordered by both individuals and organizations, and are carried out by their accomplices. Acts of assassination have been performed since ]. A person who carries out an assassination is called an '''assassin'''.<ref>. Accessed 27 Oct. 2024.</ref> | |||

| ==Etymology== | |||

| In its most common use, '''assassination''' has come to mean the ] of an important person. An assassin — one who carries out the assassination — is usually motivated by ] or ] reasons. Other motivations may be ] in the case of a ]; opposition to a person's ]s or belief systems in the case of a ]; orders from a ] that are often carried about by a subversive agent such as a ]; or ] to a competing leader or group. | |||

| {{Main|Hashshashin}} | |||

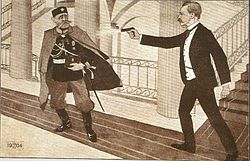

| ], the Russian ], ] by ] on June 16, 1904, in ].<ref>{{cite journal | first1 = George B. | last1 = Kauffman | first2 = Lauri | last2 = Niinistö | author-link1 = George B. Kauffman |url = http://chemeducator.org/bibs/0003003/00030208.htm | title = Chemistry and Politics: Edvard Immanuel Hjelt (1855–1921) | journal = The Chemical Educator | year = 1998 | volume =3 | issue = 5 | doi = 10.1007/s00897980247a | pages = 1–15| s2cid = 97163876 }}</ref> The author of the drawing is unknown.]] | |||

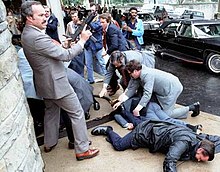

| ], who was deemed ] of U.S. President ] on November 22, 1963. Oswald was assassinated two days later by ], the first such event to occur during live television coverage.|left]] | |||

| ''Assassin'' comes from the Italian and French Assissini, believed to derive from the word '']'' ({{langx|ar|حشّاشين|ḥaššāšīyīn}}),<ref>''American Speech'' – McCarthy, Kevin M. Volume 48, pp. 77–83</ref> and shares its etymological roots with '']'' ({{IPAc-en|h|æ|ˈ|ʃ|iː|ʃ}} or {{IPAc-en|ˈ|h|æ|ʃ|iː|ʃ}}; from {{lang|ar|حشيش}} ''{{transliteration|ar|DIN|ḥašīš}}'').<ref name="OED">{{cite web |title=assassinate |url=https://www.etymonline.com/word/assassinate |publisher=Online Etymology Dictionary |access-date=28 February 2024}}</ref><ref name="The Assassins: a radical sect in Islam">''The Assassins: a radical sect in Islam'' – Bernard Lewis, pp. 11–12</ref> It referred to a group of ] known as the ] who worked against various political targets.<ref name=":1" /> | |||

| Assassination, like companion terms such as ] and ], is often considered to be a ]. The definition of assassination is generally much clearer than the others. Most assassins appear comfortable enough with their deed to describe it as such publicly, whereas few call themselves terrorists. | |||

| Founded by ], the Assassins were active in the ] from the 11th to the 13th centuries. The group killed members of the ], ], ], and Christian ] elite for political and religious reasons.<ref name=":1">Secret Societies Handbook, Michael Bradley, Altair Cassell Illustrated, 2005. {{ISBN|978-1-84403-416-1}}</ref> | |||

| == Etymology == | |||

| The term originally referred to a ] ]ic ] known as the ]. The word means "those who use ] (cannabis resin)" in Arabic because, according to Crusader histories, that group used to ingest hashish before carrying out military or assassination operations, in order to be fearless. The group, known as the Nizari ]s, was a Shia order who believed in the notion of the hidden ] and was organized as a secret underground political order, which infiltrated areas under the control of ]. In 1090 the sect captured a castle called ] in the mountains of Northern ]. This sect was said to carry out assassinations of the enemies of the order, or Muslim rulers they believed to be ]. The earliest known record of the word in ] (dating from the early ]) refers to this sect rather than its more general modern sense. Similar words had earlier appeared in ] and ]. | |||

| Although it is commonly believed that members of the Order of Assassins were under the influence of ] during their killings or during their indoctrination, there is debate as to whether these claims have merit, with many Eastern writers and an increasing number of Western academics coming to believe that drug-taking was not the key feature behind the name.<ref name="C:AH">{{cite book| url = https://books.google.com/books?id=O7AoY6ljSygC&q=hashishiyya | author= Martin Booth | title= Cannabis: A History |year= 2004 | publisher= Macmillan| isbn = 978-0-312-42494-7}}</ref> | |||

| ] provided the first western account of the sect. ]'s elaborate account is probably fictionalized in part. He said that recruits were promised ] in return for dying in action. They were drugged, often with materials such as ] (although some suggest ] and ] instead, all being, nonetheless, condemned by Islamic religious authorities and interpretations of the time) then spirited away to a garden stocked with attractive and compliant women and fountains of wine. At this time, they were awakened and it was explained to them that such was their reward for the deed, convincing them that their leader, ], could open the gates to Paradise. The name ''assassin'' is derived from either ''hasishin'' for the supposed influence of their attacks and disregard for their own lives in the process, or ''hassansin'' for their leader. All this history, however, is tenous, as it relies entirely on crusader-authored histories which have been traditionally very unreliable for information about native cultures. | |||

| The term "assassinare" (assassin) was used in ] from the mid 13th century.<ref name="OED"/> | |||

| Nowadays is known that "hashishinnya" was an offensive term used to depict this cult by its Muslim and Mongolian detractors; the extreme zeal of Nizarites and the very cold preparation to murder makes it very unlikely they ever used drugs, while there is evidence that one of the first Hassan's sons was sentenced to death by his father only for drinking a little wine. Moreover, despite many unlikely legends, they usually died along with their target (a tale tells of a mother being sad knowing her son survived a "mission"). As far as known they only used daggers (no other weapons, poison or whatever fictional records make them use) and it seems that they killed only five westeners during the time of the Crusades. | |||

| The earliest known use of the verb "to assassinate" in printed English was by ] in ''A Briefe Replie to a Certaine Odious and Slanderous Libel, Lately Published by a Seditious Jesuite'', a pamphlet printed in 1600, five years before it was used in '']'' by ] (1605).<ref>''A briefe replie to a certaine odious and slanderous libel, lately published by a seditious Iesuite.'' Imprinted at London: By Arn. Hatfield, 1600 (STC 23453) p. 103</ref><ref>"assassinate, v." OED Online. Oxford University Press, June 2016. Web. August 11, 2016.</ref> | |||

| ] in ]. He was shot and injured, and thereafter appeared in public in a custom-built "]" featuring ].]] | |||

| ==Use in history== | |||

| ==Definition problems== | |||

| {{Main|History of assassination}} | |||

| Unlike some topics, notably terrorism, wherein there is a substantial ] and often bitter controversy between which specific instances qualify or even what standards should be used, the "]" classification of assassination stated at the outset of this article seems to stand with few objections. However, this does open larger issues concerning interpretation, notably regarding attempted killings by those with other motives — is it an assassination simply if the person is a major leader or public figure espousing a cause, or only if the assassin's reason for the attack is due to that person's status as a figurehead for a particular issue? | |||

| ===Ancient to medieval times=== | |||

| Notable instances in which this definitive problem might come into effect include the assassination attempt against ] ] by ], who was determined subsequently to have serious psychological problems and publicly stated his intent was to get the attention of actress ] rather than make any political statement. The killing of former ] ] would raise the same problem — despite his outspokenness on many liberal political issues, the killer does not seem to have been more than an unstable ] (although it may be of note that the word is derived from '']''). The use of the term "assassination" to describe Lennon's murder is a matter of some additional debate, since Lennon was primarily an entertainment, not a political figure, and it could be argued that describing his killing as an assassination is no more appropriate than, for example, using the term to describe the murders of singers ] or ]. In another example, although ] suggest the apparent suicide of ] might have been a politically motivated murder, the term "assassination" is rarely, if ever, used in this context. The attempt on the life of President ] by a member of ]'s ] could be the same; while it might perhaps be considered part and parcel of the anti-government, neo-fascist ideology to which Manson and his group adhered, ], the assassin, was not widely considered legally competent in her judgment at the time (although she was later tried and convicted). Were these killings, assuming success, to be classified as murders or assassinations? The issue is further complicated by the fact that while Lennon was likely as outspoken politically as Reagan and Ford, and certainly as famous, Reagan and Ford were elected officials at the time, possibly requiring different criteria for Lennon's case. | |||

| Assassination is one of the oldest tools of ]. It dates back at least as far as recorded history.{{citation needed|date=October 2024}} | |||

| The Egyptian pharaoh ], of the ] ] (23rd century BCE), is thought to be the earliest known victim of assassination, though written records are scant and thus evidence is circumstantial. Two further ancient Egyptian monarchs are more explicitly recorded to have been assassinated; ] of the ] ] (20th century BCE) is recorded to have been assassinated in his bed by his palace guards for reasons unknown (as related in the '']''); meanwhile ] relate the assassination of ] ] monarch ] in 1155 BCE as part of a ]. Between 550 BC and 330 BC, seven Persian kings of ] were murdered. ], a 5th-century BC Chinese military treatise mentions tactics of Assassination and its merits.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Withington |first=John |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-9sBEAAAQBAJ&q=history+of+assassination |title=Assassins' Deeds: A History of Assassination from Ancient Egypt to the Present Day |date=2020-11-05 |publisher=Reaktion Books |isbn=978-1-78914-352-2 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| One can take one of three positions (note that this consideration is of necessity strictly based upon language, not law): that the killing of someone ''only for political, moral, or ideological reasons'' constitutes an assassination (hence neither Reagan nor Lennon were the victims of assassins' attacks, while Ford was), that the killing of someone ''serving in politics or public office'' counts (thus Reagan's and Ford's attackers were would-be assassins, while Lennon's killer was not), or that anyone ''with a significant level of political involvement'' would be an assassination victim in the event of their murder (in which case all three instances would be assassinations or attempts). | |||

| In the ], King ] of ] was assassinated by his own servants;<ref>2 Kings 12:19-21</ref> ] assassinated ], ]'s son;<ref>2 Samuel 3:26–28 RSV</ref> King ] of Assyria was assassinated by his own sons;<ref>2 Chronicles 32:21</ref> and ] assassinated ].<ref>Judges 4 and 5</ref> | |||

| While it must be acknowledged that attempting to read a person's thoughts is both imperfect and somewhat antithetical to the nature of such an issue, for the purposes of this article, the first, most conservative definition is taken. Although it is likely that the second is the most popular, the first is technically the most correct, and the third is generally considered to be too general in application. Therefore, all assassinations or attempts mentioned in the article will strictly follow the guidelines outlined at the outset to prevent confusion. | |||

| ] ({{circa|350}}–283 BC) wrote about assassinations in detail in his political treatise '']''. His student ], the founder of the ], later made use of assassinations against some of his enemies.<ref>{{cite journal |author-link = Roger Boesche | first = Roger | last = Boesche |date=January 2003 | title = Kautilya's ''Arthaśāstra'' on War and Diplomacy in Ancient India | journal = The Journal of Military History | volume = 67 | issue = 1 | pages = 9–37 | doi = 10.1353/jmh.2003.0006 | s2cid = 154243517 | url=http://muse.jhu.edu/demo/journal_of_military_history/v067/67.1boesche.pdf |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20221009/http://muse.jhu.edu/demo/journal_of_military_history/v067/67.1boesche.pdf |archive-date=2022-10-09 |url-status=live| doi-access = free }}</ref> | |||

| == Assassination as a political tool == | |||

| Some famous assassination victims are ] (336 BC), the father of ], and Roman dictator ] (44 BC).<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=kloWAAAAYAAJ&q=famous+assassinations |title=Famous assassinations of history ... |date=March 3, 2008 |access-date=October 27, 2010|last1=Johnson|first1=Francis}}</ref> ] often met their end in this way, as did many of the Muslim ]s hundreds of years later. Three successive Rashidun caliphs (], ], and ]) were assassinated in early civil conflicts between Muslims. The practice was also well known in ancient China, as in ]'s failed assassination of ] king ] in 227 BC. Whilst many assassinations were performed by individuals or small groups, there were also specialized units who used a collective group of people to perform more than one assassination. The earliest were the ] in 6 AD, who predated the Middle Eastern ] and Japanese ]s by centuries.<ref>Pichtel, John, ''Terrorism and WMDs: Awareness and Response'', CRC Press (April 25, 2011) pp. 3–4. {{ISBN|978-1439851753}}</ref><ref name="Ross">Ross, Jeffrey Ian, ''Religion and Violence: An Encyclopedia of Faith and Conflict from Antiquity to the Present'', Routledge (January 15, 2011), Chapter: Sicarii. 978-0765620484</ref> | |||

| Some would argue that assassination is one of the oldest tools of ], dating back to the earliest governments of the world — ], the father of ], met his end this way. It is a fact, however, that by the ] assassination had become a commonly-accepted tool towards the end not only of improving one's own position, but to influence policy — the killing of ] being a notable example, though many ] met such an end. In whatever case, there seems to have not been a good deal of moral indignation at the practice amongst the political circles of the time, save, naturally, by the affected. | |||

| In the ], ] was rare in Western Europe, but it was a recurring theme in the ]. Strangling in the bathtub was the most commonly used method. With the ], ]—or assassination for personal or political reasons—became more common again in Western Europe.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Veronesi |first=Gene |title=Chapter 1: The Italian Renaissance and Western Civilization |url=https://pressbooks.ulib.csuohio.edu/italian-americans-and-their-communities-of-cleveland/chapter/chapter-1/ |journal=Italian Americans and Their Communities of Cleveland}}</ref> | |||

| As the ] came about from the fall of the ], the moral and ethical dimensions of what was before a simple political tool began to take shape. Although in that period intentional ] was an extremely rare occurrence, the situation changed dramatically with the ] when the ideas of ''tyrannomachy'' (i.e. killing of a King when his rule becomes tyrannical) re-emerged and gained recognition. Many a head of state of the time fell at the hands of an assassin, such as ] and ]. There were notable detractors, however; ] of the ] refused to put to death plotters against his life during his reign. | |||

| ===Modern history=== | |||

| As the world moved into the present day and the stakes in political clashes of will continued to grow to a global scale, the number of assassinations concurrently multiplied. In ] alone, five emperors were assassinated within less than 200 years - ], ], ], ] and ]. The most notable assassination victim within early ] was President ]. Three other U.S. Presidents have been assassinated including ], ], and ]. An assassination plot against ], known as the ], may have been initiated during the ]. In ] the assassination of ] ] triggered ]. However, the ] likely marks the first time ]s began training assassins to be specifically used against so-called enemies of the state. During ], for example, ] trained a group of ]n operatives to kill the ] ] ] (who did later perish by their efforts), and repeated attempts were made by both the British MI6, the American ] (later the ]) and the Soviet ] to kill ]. | |||

| ], ], ], ] and ].|left]] | |||

| During the 16th and 17th centuries, international lawyers began to voice condemnation of assassinations of leaders. ] has been described as "the first prominent jurist to condemn the use of assassination in foreign policy".<ref name=Thomas2000>{{cite journal |last1=Thomas |first1=Ward |title=Norms and Security: The Case of International Assassination |journal=International Security |date=July 2000 |volume=25 |issue=1 |pages=105–133 |doi=10.1162/016228800560408 |jstor=2626775 |s2cid=57572213 }}</ref> ] condemned assassinations in a 1598 publication where he appealed to the self-interest of leaders: (i) assassinations had adverse short-term consequences by arousing the ire of the assassinated leader's successor, and (ii) assassinations had the adverse long-term consequences of causing disorder and chaos.<ref name=Thomas2000/> ]'s works on the law of war strictly forbade assassinations, arguing that killing was only permissible on the battlefield.<ref name=Thomas2000/> In the modern world, the killing of important people began to become more than a tool in power struggles between rulers themselves and was also used for political symbolism, such as in the ].<ref name="Gillen">M. Gillen 1972 ''Assassination of the Prime Minister: the shocking death of Spencer Perceval''. London: Sidgwick & Jackson {{ISBN|0-283-97881-3}}.</ref> | |||

| In Japan, a group of assassins called the ] killed a number of people, including ] who was the head of administration for the Tokugawa shogunate, during the ].<ref>Turnbull, Stephen. ''The Samurai Swordsman: Master of War''. Tuttle Publishing; 1 edition (August 5, 2014). p. 182. {{ISBN|978-4805312940}}</ref> Most of the assassinations in Japan were committed with bladed weaponry, a trait that was carried on into modern history. A video-record exists of the ], using a sword.<ref name=chun>{{cite book |title=A Nation of a Hundred Million Idiots?: A Social History of Japanese Television, 1953–1973 |last=Chun |first=Jayson Makoto |publisher=Routledge |year=2006 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=9miRAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA184 |pages=184–185 |isbn=978-0-415-97660-2 |access-date=March 22, 2014}}</ref> | |||

| The ] saw a dramatic increase in the number of political assassinations, likely in large part due to the ] polarization of most of the ] and ], whose adherents were more than willing to both justify and finance such killings. During the Kennedy era ] narrowly escaped death on several occasions at the hands of the CIA (a function of the agency's "]" program) and CIA-backed rebels (there are accounts that exploding clams and poisoned shoes were employed); some allege that ] of ] was another example, though specific proof is lacking. At the same time, the ] made creative use of assassination to deal with high-profile defectors such as ], and ]'s ] made use of such tactics to eliminate ] ], politicians and revolutionaries, though some Israelis argue that the targeted often crossed the line between one or another or were even all three. | |||

| In 1895, a group of Japanese assassins ] (and posthumously empress) Myeongseong.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Nagai |first=Yasuji |date=2021-11-21 |title=Diplomat's 1895 letter confesses to assassination of Korean queen |url=https://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/14482741 |access-date=2023-08-16 |website=The Asahi Shimbun |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| Most major powers were not long in repudiating such tactics, for example during the presidency of ] in the United States in ] (Executive Order 12333). Many allege, however, that this is merely a smoke screen for political and moral benefit and that the covert and illegal training of assassins by major intelligence agencies continue, such as at the ] run by the United States. In fact, the debate over the use of such tactics is not closed by any means; many accuse ] of continuing to practice it in ] and against Chechens abroad, as well as Israel in Palestine and against Palestinians abroad (as well as those Mossad deems a threat to Israeli national security, as in the aftermath of the ]) and Palestinians and other ] nations against ]s in Israel and abroad. | |||

| In the United States, from 1865 to 1963, four presidents—], ], ] and ]—died at the hands of assassins. There have been at least ] on U.S. presidents' lives.<ref>{{cite web |title=Appendix 7 |url=https://www.archives.gov/research/jfk/warren-commission-report/appendix7.html |website=National Archives |access-date=20 May 2023 |language=en |date=15 August 2016}}</ref> | |||

| Proponents of assassination as a political tool point out that it can be a very effective and inexpensive way to prevent loss of life. Opponents of assassination bring up a number of objections. The first is that assassination is essentially the ] stripped of the normal judicial safeguards that limit its use. Second, opponents of assassination question its effectiveness. Most conventional military and political organizations are robust so that the death of the leader would not cause them to collapse. Furthermore, using assassination against a terrorist or guerilla organization may result in the complete elimination of the known leaders of that organization, but create a set of unknown leaders who cannot then be located. Finally, assassination makes a negotiation of surrender impossible. Near the end of World War II, for example, Allied forces made specific efforts not to target the political and military leadership of the ] specifically so that there would be someone to authorize a surrender. | |||

| In Austria, the ] and his wife ] was carried out in Sarajevo on June 28, 1914, by ], a Serbian nationalist. He is blamed for igniting ]. ] died after an attack by British-trained Czechoslovak soldiers on behalf of the Czechoslovak government in exile in ],<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.army.cz/images/id_7001_8000/7419/assassination-en.pdf |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20221009/http://www.army.cz/images/id_7001_8000/7419/assassination-en.pdf |archive-date=2022-10-09 |url-status=live |title=Assassination – Operation Arthropoid, 1941–1942 |access-date= July 5, 2011 |last=Burian |first=Michal |author2=Aleš |year=2002 |publisher=Ministry of Defence of the Czech Republic}}</ref> and knowledge from decoded transmissions allowed the United States to carry out ], killing Japanese ] ] while he was travelling by plane.<ref name=McNaughton2006>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=YHdFDZwbnkkC&pg=PA185 |page=185 |last=McNaughton |first=James C. |date=2006 |title=Nisei Linguists: Japanese Americans in the Military Intelligence Service During World War II |publisher=U.S. Government Printing Office |isbn=9780160867057}}</ref> | |||

| == Assassination for money == | |||

| During the 1930s and 1940s, ]'s ] carried out numerous assassinations outside of the Soviet Union, such as the killings of ] leader ], ], ] secretary Rudolf Klement, ], and the Workers' Party of Marxist Unification (]) leadership in ].<ref>Michael Ellman. '' {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090227181110/http://www.paulbogdanor.com/left/soviet/famine/ellman.pdf |date=February 27, 2009 }}.'' Europe-Asia Studies, 2005. p. 826</ref> India's "Father of the Nation", ], was ] on January 30, 1948, by ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Hardiman |first=David |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/52127756 |title=Gandhi in his time and ours : the global legacy of his ideas |date=2003 |publisher=Columbia University Press |isbn=0-231-13114-3 |location=New York |oclc=52127756}}</ref> | |||

| Individually, too, people have often found reasons to arrange the deaths of others through paid intermediaries. One who kills with no political motive or group loyalty who kills ''only'' for money is known as a ] or contract killer. Note that by the definition accepted above, while such a killer is not, strictly speaking, an assassin, if the killing is ordered and financed towards a political end, then that killing must rightly be termed an assassination, and the hitman an assassin by extension (in the same way that a '']''-style killer would be an assassin because, though they have been brainwashed to kill and have therefore no political aims, those that brainwashed them do have such aims, and if the killing can be termed an assassination, the killer must be an assassin). | |||

| The African-American civil rights activist, ], was ] on April 4, 1968, at the Lorraine Motel (now the ]) in ]. Three years prior, another African-American civil rights activist, ], was assassinated at the ] on February 21, 1965.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Karim |first=Benjamin |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/26931305 |title=Remembering Malcolm |date=1992 |publisher=Carroll & Graf |others=David Gallen, Peter Skutches |isbn=0-88184-901-4 |edition=1st Carroll & Graf |location=New York |oclc=26931305}}</ref> | |||

| Entire organizations have sometimes specialized in assassination as one of their services, to be gained for the right price. Besides the original ], the ] clans of ] were rumored to perform assassinations — though it can be pointed out that most of what was ever known about the ninja was ] and hearsay. In the ], ], an organization partnered to the ], was formed for the sole purpose of performing assassinations for organized crime. In ], the ''vory'' (thieves), their version of the Mafia, are often known to provide assassinations for the right price, as well as engaging in it themselves for their own purposes. | |||

| ===Cold War and beyond=== | |||

| == Assassination as military doctrine == | |||

| {{See also|Cold War|War on terror}} | |||

| ]'s blood-stained ] and belongings at the time of her assassination. She was the ].]] | |||

| Most major powers repudiated Cold War assassination tactics, but many allege that was merely a smokescreen for political benefit and that covert and illegal training of assassins continues today, with Russia, Israel, the U.S., ], Paraguay, Chile, and other nations accused of engaging in such operations.<ref>John Dingles (2004) The Condor Years {{ISBN|978-1-56584-764-4}}</ref> After the ] of 1979, the new Islamic government of Iran began an international campaign of assassination that lasted into the 1990s. At least 162 killings in 19 countries have been linked to the senior leadership of the ].<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.iranhrdc.org/httpdocs/English/pdfs/Reports/No-Safe-Haven_May08.pdf | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100902192858/http://www.iranhrdc.org/httpdocs/English/pdfs/Reports/No-Safe-Haven_May08.pdf | archive-date=September 2, 2010| title=English front cover – No Safe Haven | access-date=June 2, 2010 | page=100}}</ref> The campaign came to an end after the ] because a German court publicly implicated senior members of the government and issued arrest warrants for ], the head of Iranian intelligence.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://iranhrdc.org/httpdocs/English/pdfs/Reports/Murder-at-Mykonos_Mar07.pdf |title=Mykonos front cover |access-date=May 13, 2010 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100902192942/http://www.iranhrdc.org/httpdocs/English/pdfs/Reports/Murder-at-Mykonos_Mar07.pdf |archive-date=September 2, 2010 |url-status=dead }}</ref> Evidence indicates that Fallahian's personal involvement and individual responsibility for the murders were far more pervasive than his current indictment record represents.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://iranhrdc.org/httpdocs/English/pdfs/Reports/Condemned-by-Law_Nov08.pdf |title=Condemned by Law – Report 11-10-08.doc |access-date=May 13, 2010 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100307043035/http://www.iranhrdc.org/httpdocs/English/pdfs/Reports/Condemned-by-Law_Nov08.pdf |archive-date=March 7, 2010 |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| While assassination for military purposes has long been espoused — ] argued for such in '']'', as did ] in his '']'' — many modern analysts hold the belief that today such a system would not be of any significant use in a strategic way. In medieval times, for instance, an army and even a nation might be based upon and around a particularly strong, canny or charismatic leader, whose loss could paralyze the ability of both to make war. However, in modern warfare a soldier's mindset is generally considered to surround ideals far more than specific leaders. Theoretically, while the death of a soldier's leader would (and does) have a detrimental effect on morale, the comfort of the cause for which they fight is far more sustainable than such supposedly-transitive loyalty to a single person. | |||

| In India, ] ] and her son ] (neither of whom was related to ], who had himself been assassinated in 1948), were assassinated in 1984 and 1991 in what were linked to ] movements in ] and northern ], respectively.<ref>{{Cite web |title=India: Extremism & Terrorism |url=https://www.counterextremism.com/countries/india-extremism-and-terrorism |access-date=2023-12-31 |website=Counter Extremism Project |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| Also, assassinating a military leader runs the risk of eliminating a later advocate of peace, as many would argue that military leaders, seeing the face of warfare and bearing a clearer sense of the war effort's effects, have more sagacity on the subject. Not only that, but worse, there is a high chance such a killing will be treated as not only reinforcing evidence of the opponents' moral bankruptcy, but also ] the leader, rallying still others to an enemy cause and hardening the enemies' resolve to fight — and resist entreaties to peace (indeed, the death in battle of ] of ], while not an assassination, led directly to the ] defeat at ] as the infuriated Swedes rallied behind their fallen leader). Such an effect can be extremely detrimental to a group or state, but supporters might argue in return that when faced with a particularly brilliant leader, there is no choice but to take the chance and, essentially, hope for a more mediocre successor (one might use the example of the many attempts to kill the Athenian ] during the ], the American shooting down of ] ] during World War II, or arguably Henri IV of France). Also, they might note that in a time-sensitive situation, such a killing could be useful if only to briefly buy time for a more permanent and effective plan to be set into motion or stall an army as reinforcements rush to the area. | |||

| In 1994, the ] during the ] sparked the ].<ref>{{Citation |last=Jacquemin |first=Céline A. |title=Hegemony and Counterhegemony |date=2015 |url=https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137555007_6 |work=The Roots of Ethnic Conflict in Africa: From Grievance to Violence |pages=93–123 |editor-last=Nasong’o |editor-first=Wanjala S. |access-date=2023-08-14 |place=New York |publisher=Palgrave Macmillan US |language=en |doi=10.1057/9781137555007_6 |isbn=978-1-137-55500-7}}</ref><ref>{{Citation |title=Opportunity II: Death of the Nation's Father |date=2021 |url=https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/path-to-genocide-in-rwanda/opportunity-ii-death-of-the-nations-father/C7E379604EFF1D0CE0CAA512F67198D8 |work=The Path to Genocide in Rwanda: Security, Opportunity, and Authority in an Ethnocratic State |pages=178–247 |editor-last=McDoom |editor-first=Omar Shahabudin |access-date=2023-08-14 |series=African Studies |place=Cambridge |publisher=Cambridge University Press |doi=10.1017/9781108868839.005 |isbn=978-1-108-49146-4|s2cid=235502691 }}</ref> | |||

| There are a number of examples from ], the last ], which show how assassination can be used as an effective military tool both at a tactical and strategic level. The American's perception that ]'s ]s were trying to assassinate ] during the ] shows that military assassination, or the threat of it, if well timed can be a very effective tactical move. In an interview with the ''New York Times'' Skorzeny denied that he had ever intended to ] and could prove it. ''(Page 155, Commando Extraordinary, by Charles Foley).'' There is also a mention in the same book ''(Page 35)'' of a British commando raid to "capture" ]. If he had been removed from the board, then that might well have had strategic effects. The British, too, decided not to try to assassinate Admiral ], head of the ] (''German military intelligence''), because to do so might have improved the service. | |||

| In Israel, Prime Minister ] was assassinated on November 4, 1995, by ], who opposed the ].<ref>{{Cite web |title=The Assassination of Yitzhak Rabin |url=https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/the-assassination-of-yitzhak-rabin |access-date=2023-12-31 |website=www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Milestones: 1993–2000 - Office of the Historian |url=https://history.state.gov/milestones/1993-2000/oslo |access-date=2023-12-31 |website=history.state.gov}}</ref> In ], the assassination of former Prime Minister ] on February 14, 2005, prompted an investigation by the United Nations. The suggestion in the resulting '']'' that there was involvement by ] prompted the ], which drove Syrian troops out of Lebanon.{{citation needed|date=May 2022}} | |||

| == Moral issues == | |||

| On 2 September 2022, a 35 year old Brazilian national attempted to assassinate the then vice-president of Argentina, ]. However, the attempt was unsuccessful because the assassin's gun jammed.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Binley |first1=Alex |last2=Murphy |first2=Matt |title=Cristina Fernández de Kirchner: Gun jams during bid to kill Argentina vice-president |url=https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-62762421 |access-date=22 May 2024 |agency=BBC |date=2 September 2022}}</ref> | |||

| ] is also important when examining the use of assassination. Opponents of what one American officer called "trial, judgment and execution by intelligence" argue that no state deliberately training, hiring, sanctioning or harboring an assassin could hope to justify it in such a way that would satisfy its allies and neighbors, much less the affected nations (even though many might use the tactic themselves). In ] this issue is particularly crucial; much of the impetus for engaging in military action in such states is the motivation of perceived righteousness fighting a brutal enemy, an opinion that is undermined if one's nation is actively and openly engaged in killings outside the laws of war. Many would argue that the negative morale effects alone would outweigh any possible benefits. | |||

| ==== United States government killing of citizens ==== | |||

| Supporters of assassination as a policy reply, however, that often the killing of one problematic figure can spare countless lives and years — or even decades — of warfare. An example often cited is the question of what might have come to pass had Adolf ] been assassinated in ]. Countless millions, the argument goes, would have been spared had only such intervention been taken. However, it could be argued that Adolf Hitler was just one man in a Nazi Party of hundreds, and his successor may be just as brutal (not to mention vengeful). Furthermore, it can be argued that this logic would not only justify killing Hitler in 1935 but also killing baby Adolf in his crib. | |||

| In 2012, '']'' revealed that the Obama administration maintained a "kill list" containing terrorism suspects.<ref>{{Cite news |last1=Becker |first1=Jo |last2=Shane |first2=Scott |date=May 29, 2012 |title=Secret 'Kill List' Proves a Test of Obama's Principles and Will |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/29/world/obamas-leadership-in-war-on-al-qaeda.html |access-date=September 21, 2024 |work=]}}</ref> The list is sometimes referred to as a "disposition matrix," and President Obama made a final decision on whether anyone listed would be killed, without court oversight and without trial.<ref>{{Cite web |date=2013-06-13 |title=How Obama's 'Disposition Matrix' Kill List Could Be Used on U.S. Soil |url=https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna52192630 |access-date=2024-09-22 |website=NBC News |language=en}}</ref> In September 2011, American citizens ] and ] were assassinated in ] by the United States government via drone strikes. Two weeks later, Awlaki's 16-year-old son, also an American citizen, was killed in a strike targeting ], a senior operative in ].<ref name=":0">{{Cite news |last=Whitlock |first=Craig |date=October 22, 2011 |title=U.S. airstrike that killed American teen in Yemen raises legal, ethical questions |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/us-airstrike-that-killed-american-teen-in-yemen-raises-legal-ethical-questions/2011/10/20/gIQAdvUY7L_story.html |access-date=September 21, 2024 |newspaper=]}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=Greenwald |first=Glenn |date=5 February 2013 |title=Chilling legal memo from Obama DOJ justifies assassination of US citizens |url=https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/feb/05/obama-kill-list-doj-memo |access-date=8 July 2023 |website=The Guardian}}</ref> Al-Banna was not killed in the strike.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

| ==Further motivations== | |||

| However, the widespread attention paid to deeds by ] such as ] and ] is seen by many as another persuasive argument towards the necessity of eliminating such individuals. The increasing specter of ], too, often leads many to question why, if it is "us or them," there should be any delay in taking such action (an opponent would likely be quick to reply, however, that such an action alone leads to the loss of moral equivalence, proving their above argument, although a likely counter could be that moral equivalence is of little use to either a terrorist or one of their dead victims). | |||

| ===As a military and foreign policy doctrine=== | |||

| == Techniques == | |||

| {{See also|Manhunt (military)|Decapitation (military strategy)|Covert operation}} | |||

| ] included espionage, ] and assassination.]] | |||

| Assassination for military purposes has long been espoused: ], writing around 500 BC, argued in favor of using assassination in his book '']''. Over 2000 years later, in his book '']'', ] also advises rulers to assassinate enemies whenever possible to prevent them from posing a threat.<ref>Machiavelli, Niccolò (1985), The Prince, University of Chicago Press. Translated by Harvey Mansfield</ref> An army and even a nation might be based upon and around a ], whose loss could paralyze the ability of both to make war. | |||

| It's entirely likely that the first strategy used by a political or religious killer was a remarkably simple one: find the leader and ] or ] them to death with whatever weapons were available. This would likely have occurred only in close-knit groups where security was not thought needed, such as amongst nomadic or early sedentary peoples in ] where disagreements would be solved with ] (however it's important to note that information from this far back is very sketchy and debatable in nature). As ] took root, however, any leaders in groups began to have more and more a position of importance, and they would become more detached from the groups they ruled. For the first time, ] would become a major factor in engaging in assassination. | |||

| For similar and additional reasons, assassination has also sometimes been used in the conduct of ]. The costs and benefits of such actions are difficult to compute. It may not be clear whether the assassinated leader gets replaced with a more or less competent successor, whether the assassination provokes ire in the state in question, whether the assassination leads to souring domestic public opinion, and whether the assassination provokes condemnation from third-parties.<ref name="iraja" /><ref name=Thomas2000/> One study found that perceptual biases held by leaders often negatively affect decision making in that area, and decisions to go forward with assassinations often reflect the vague hope that any successor might be better.<ref name="iraja">{{cite journal | title=Decision Making in Using Assassinations in International Relations | url=http://www.psqonline.org/article.cfm?IDArticle=19545 | journal=] | volume=131| issue=3 | date=Fall 2016 | pages= 503–539 | last1=Schilling | first1=Warner R. | author-link=Warner R. Schilling | last2= Schilling | first2=Jonathan L. |doi = 10.1002/polq.12487}}</ref> | |||

| From ancient times, then, through to the medieval period, as the rate of technology was slow so, too, would be the changes in assassins' tactics. ] was now the name of the game, and commonly a would-be killer would attempt to gain access to an official or person's guard or staff and utilize a variety of methods for exterminating them, be it the same close-contact stabbing or ] or a more advanced method, such as using ] to induce death. This, however, must be distinguished from efforts by a person or group to remove a person in order to replace them in the ]; for more on this, see ]. | |||

| In both military and foreign policy assassinations, there is the risk that the target could be replaced by an even more competent leader, or that such a killing (or a failed attempt) will prompt the masses to contemn<!-- not a typo for "condemn" --> the killers and support the leader's cause more strongly. Faced with particularly brilliant leaders, that possibility has in various instances been risked, such as in the attempts to kill the Athenian ] during the ]. A number of additional examples from ] show how assassination was used as a tool: | |||

| With the advent of ] and far more effective ], however, bodyguards were no longer enough to hold back determined killers, who no longer needed to directly engage or even subvert the guard to kill the leader in question; it could be done from a great distance in a crowded square or even at a church, as with the ], for example. Often, ]s or ]s might be used to take down a leader from a rooftop, at greater distance, dramatically increasing the chances for survival of an assassin. Also, ] became increasingly en vogue for deeds requiring a larger touch; for an example of this, see the article on the ] to blow up ] on the ]. | |||

| * The ] in Prague on May 27, 1942, by the British and Czechoslovak government-in-exile. That case illustrates the difficulty of comparing the benefits of a foreign policy goal (strengthening the legitimacy and influence of the ] in London) against the possible costs resulting from an assassination (the ]).<ref name="iraja"/> | |||

| * The American interception of Admiral ]'s plane during World War II after his travel route had been decrypted. | |||

| * ] was a planned British commando raid to capture or kill the German field marshal ], also known as "The Desert Fox".<ref name="Skor">''Commando Extraordinary'' – Foley, Charles; Legion for the Survival of Freedom, 1992, page 155</ref> | |||

| Use of assassination has continued in more recent conflicts: | |||

| In whatever case, it is interesting to note that just because more modern methods of killing became available does not mean older ones were replaced; indeed, in nations like ] killings by knife or ] remain quite popular, as they do in ] (for example, with the ]). In fact, since the development of gunpowder each region of the world seems to have its preferred methods of contract murder; besides those mentioned, explosives are quite popular in not only the Middle East but in most of Europe as well, save ] where shootings become more common, whereas in the Americas assassinations are almost exclusively performed by gunshot. One can make various cases for any of these, including range, detectability, concealability, likelihood of kill, etc. | |||

| * During the ], the US engaged in the ] to assassinate ] leaders and sympathizers. It killed between 6,000 and 41,000 people, with official "targets" of 1,800 per month.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Barnett |first1=James |url=https://strausscenter.org/wp-content/uploads/Barnett_James.pdf |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20221009/https://strausscenter.org/wp-content/uploads/Barnett_James.pdf |archive-date=2022-10-09 |url-status=live |title=When Culture Eats Strategy: Examining the Phoenix/Phung Hoang Bureaucracy in the Vietnam War, 1967-1972 |website=Strauss Center |access-date=February 9, 2021}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author=McCoy, Alfred W.|title=A question of torture: CIA interrogation, from the Cold War to the War on Terror |publisher=Macmillan|year=2006|isbn=978-0-8050-8041-4|page=68|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=FVwUYSBwtKcC&pg=PA68|author-link=Alfred W. McCoy }}</ref><ref name=hersh03>{{cite magazine |author-link=Seymour Hersh |last=Hersh|first=Seymour|title=Moving Targets|magazine=The New Yorker|date=December 15, 2003|url=http://www.newyorker.com/archive/2003/12/15/031215fa_fact?currentPage=all|access-date=February 9, 2021}}</ref> | |||

| * With the January 3, 2020 Baghdad International Airport airstrike, the US ] the commander of Iran's ] General ] and the commander of Iraq's ] ], along with eight other high-ranking military personnel. The assassination of the military leaders was part of escalating tensions between the US and Iran and the ].<ref>{{cite news | title=Qassem Suleimani: 'Death to America' chants at Baghdad funeral procession | url=https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jan/04/huge-crowds-expected-in-baghdad-for-funeral-of-iranian-general-killed-by-us | first=Ghait|last=Abdul-Ahat|newspaper=]|date= January 4, 2020}}</ref><ref>{{cite news | title=Iran Says It Has Decided How to React to U.S. Strike That Killed Soleimani | url=https://www.haaretz.com/middle-east-news/four-rockets-hit-military-base-near-baghdad-airport-report-says-1.8350357 | first=Amos|last=Harel|newspaper=]|date= January 4, 2020}}</ref> | |||

| ===As a tool of insurgents=== | |||

| As the Renaissance gave way to the ], assassination became more and more sophisticated, right up to today. Explosives, especially the ], became far more common, and ]s and ]s were not unheard of either, especially in the ] and Balkans (the initial attempt on Archduke Franz Ferdinand's life was with a grenade; he was on his way to visit an aide injured in the first attack when his driver stopped to ask directions and he and his wife were shot). Also, ]s became an especially useful tool, given the popularity of armored cars discussed below. Today, any manner of different techniques for the elimination of an enemy — popular or not — might be utilized; the sky, as it were, is the limit. Another common option is using a ]. The only difference is that assassins and their deeds are far more public than ever before, owing not only to ] but also far better security and control | |||

| Insurgent groups have often employed assassination as a tool to further their causes. Assassinations provide several functions for such groups: the removal of specific enemies and as propaganda tools to focus the attention of media and politics on their cause.{{citation needed|date=October 2024}} | |||

| over access. | |||

| The ] guerrillas in 1919 to 1921 killed many ] Police intelligence officers during the ]. ] set up a special unit, ], for that purpose, which had the effect of intimidating many policemen into resigning from the force. The Squad's activities peaked with the killing of 14 British agents in ] on ] in 1920.{{citation needed|date=October 2024}} | |||

| == Counter-measures == | |||

| The tactic was used again by the ] during ] in Northern Ireland (1969–1998). Assassination of ] politicians and activists was one of a number of methods used in the ]. The IRA also attempted to assassinate British Prime Minister ] by ] in a ] hotel. ] retaliated by killing Catholics at random and assassinating ] politicians.{{citation needed|date=October 2024}} | |||

| It would not be a large stretch to say that, in addition to ], politician assassination is one of the biggest threats to any modern ] and its ]. As such, the measures to which a leader goes to avoid professional killers ranges from what an average person would consider to be farcical to the paranoid to the downright bizarre. Many would argue, though, that such measures are a lot more effective than they first appear, and that in the world of a new threat seemingly each week, no security is too much. | |||

| ] separatists ] in Spain assassinated many security and political figures since the late 1960s, notably the president of the ] government of Spain, ], 1st Duke of Carrero-Blanco Grandee of Spain, in 1973. In the early 1990s, it also began to target academics, journalists and local politicians who publicly disagreed with it.{{citation needed|date=October 2024}} | |||

| One of the earliest forms of defense against assassins is without doubt the ]. Essentially, the bodyguard functions as a counter-assassin, attempting to neutralize the killer before they can make contact with or inflict harm upon the "principal", or protected/targeted official. This function was often executed by the leader's most loyal warriors, and was extremely effective throughout most of early human history, to the point where a direct assassination had to be replaced with carefully-planned ], such as poison (which was answered by the ] such as the ]s protecting the ] monarchs), and even then such methods were often thwarted. Notable examples of bodyguards would include the Roman ] or the Ottoman ] — although, in both cases, it should be noted that the protectors often became assassins themselves, exploiting their power to make the ] a virtual hostage at their whim or eliminating threatening leaders altogether. Indeed, assassinations both then and today are most often effective when they have the support, tacit or open, of other powerful figures. Today, however, such a situation rarely comes to pass; the British ] and American ] are noted as well-trained and apolitical protective forces. But in ], ] ] was assassinated by her own bodyguards. | |||

| The ] in Italy carried out assassinations of political figures and, to a lesser extent, so did the ] in Germany in the 1970s and the 1980s.{{citation needed|date=October 2024}} | |||

| The race was on with the Middle Ages between leaders and assassins as gunpowder became predominant, each in turn trying to develop stronger and better checks against the increasing abilities of the other. One of the first reactions was to simply increase the guard, creating what at times might seem a ] trailing every leader; another was to begin clearing large areas whenever a leader was present, to the point where entire sections of a city might be shut down. Heads of state began to cease taking their armies onto the field personally around this time as well, although this was likely as much due to the increasing skills required for generalship and division of power within the government as it was for safety concerns. | |||

| In the ], communist insurgents routinely assassinated government officials and individual civilians deemed to offend or rival the revolutionary movement. Such attacks, along with widespread military activity by insurgent bands, almost brought the ] regime to collapse before the US intervened.<ref>Pike, Douglas (1970). ''Viet Cong'' (new edition). The MIT Press.</ref> | |||

| As the 20th century dawned, the prevalence of assassins and their capabilities skyrocketed, and so did measures to protect against them. For the first time, ]s or ]s were put into service for safer transport, with modern versions rendering them virtually invulnerable to ] fire. ]s were also commissioned, although these are often not worn (or worn unobtrusively) for the benefit of public perception, although some, such as former ] of ] and presidential candidate ], were nonetheless compelled to do so. Access to famous persons, too, became more and more restrictive; potential visitors would be forced through dozens of different checks and double-checks before being granted access to the official in question, and as ] became better and ] more prevalent, it has become next-to-impossible for a would-be killer of declared antigovernment or anarchist political affiliation to get close enough to the personage at work to effect an attempt on his or her life, especially given the common use of ] and ]s. As such, in this century and for the foreseeable future, most assassinations will be committed either during a public performance or during ], both due to weaker security and security lapses, such as with US ] ] or as part of ] where security is either overwhelmed or completely removed, such as with Salvador Allende or ]. | |||

| ==Psychology== | |||

| Some of the wilder and arguably stranger methods used for protection by famous people of both today and yesterday have evoked many reactions from different people, some resenting the separation from their officials or major figures, some comforted by the security and some lamenting the state of society that such measures are necessary. One example might be traveling in a car protected by a bubble of clear ], such as the ] of ] ] (built following an extremist's attempt at his life). ] had an entire command of soldiers above two ] of height, and would reportedly go to great lengths to obtain more. Many leaders, such as ] or the Argentinian ] were so possessed by paranoia that they executed their opponents ''en masse'', with the death toll ranging from hundreds to millions. Still others go into seclusion, rarely heard from or seen in public afterwards, such as ] ] or eccentric ] ], though it is more likely that Hughes was concerned about ] than about assassination. A more exotic form of protection is the use of a body double. A body double in this case is a person who is built similar to the person he is expected to protect and made up to look like him. The body double then takes the place of the person in high risk situations. Fidel Castro, Adolf Hitler and Saddam Hussein are known to have used body doubles. | |||

| A major study about assassination attempts in the US in the second half of the 20th century came to the conclusion that most prospective assassins spend copious amounts of time planning and preparing for their attempts. Assassinations are thus rarely "impulsive" actions.<ref name="SS"/> | |||

| However, about 25% of the actual attackers were found to be ]al, a figure that rose to 60% with "near-lethal approachers" (people apprehended before reaching their targets). That shows that while mental instability plays a role in many modern assassinations, the more delusional attackers are less likely to succeed in their attempts. The report also found that around two-thirds of attackers had previously been arrested, not necessarily for related offenses; 44% had a history of serious depression, and 39% had a history of substance abuse.<ref name="SS"/> | |||

| It is important to note that, in the final analysis, it is thought by many that if a person or group is committed beyond ] or concerns for ] towards the removal of a certain person or leader from not only their position but this plane of existence, then their success is ]. Some of the most notable examples of such committed people would be the ] of Japan or ] when used against a leader or official. Often, such people or groups would ] in order to gain the slimmest chance of eliminating their mark. Certain leaders, notably ], were thought to have wrestled with this supposed inevitability during difficult times (with some, like Lincoln, later falling victim to it). In the end, however, any counter-measures to a trained or simply ] killer will be attempts to resist them as best as possible with whatever means are available. | |||

| ==Techniques== | |||

| ==Source for conspiracy theories== | |||

| ===Modern methods=== | |||

| Assassinations are a classic subject of conspiracy theories. The assassination of a prominent figure is a singular event which can dramatically change the course of public affairs. Those drawn to conspiracy theory are led to ask, in the aftermath of an assassination, ''Who benefited from this death?'' Though some assassinations are committed by lone individuals, and many others by aboveboard governments (such as that of ]), and other assassinations are committed as the result of a provable conspiracy, there have been several assassinations whose purposes and evidence remain mysterious in the public eye — and suspicious to most people. | |||

| With the advent of effective ranged weaponry and later ], the position of an assassination target was more precarious. Bodyguards were no longer enough to deter determined killers, who no longer needed to engage directly or even to subvert the guard to kill the leader in question. Moreover, the engagement of targets at greater distances dramatically increased the chances for assassins to survive since they could quickly flee the scene. The first heads of government to be assassinated with a firearm were ], the regent of Scotland, in 1570, and ], the Prince of Orange of the Netherlands, in 1584. ] and other explosives also allowed the use of bombs or even greater concentrations of explosives for deeds requiring a larger touch.{{citation needed|date=October 2024}} | |||

| Explosives, especially the ], become far more common in modern history, with ] and remote-triggered land mines also used, especially in the Middle East and the Balkans; the initial attempt on ]'s life was with a grenade. With heavy weapons, the ] (RPG) has become a useful tool given the popularity of armored cars (discussed below), and Israeli forces have pioneered the use of aircraft-mounted missiles,<ref>'''' – ], Saturday April 17, 2004</ref> as well as the innovative use of explosive devices.{{citation needed|date=October 2024}} | |||

| Best-known among assassination conspiracy theories in the United States are those dealing with a rash of seemingly politically motivated deaths in the ], notably those of U.S. ] ], ] ], and ] leaders ] and ]. | |||

| ] of ], the assassin of President ]]] | |||

| Investigations and scientific testing and recreations into the circumstances of John F. Kennedy's death have not settled the question of who killed him. That U.S. public opinion considers this still to be an open issue is suggested by three polls in 2003. An ] random telephone ] found that just 32% (plus or minus 3%) of Americans believe that ] acted alone in the assassination of John F. Kennedy, while 68% do not believe Oswald acted alone. The "Discovery Channel" poll (sampling method not given) reveals that only 21% believe Oswald acted alone, while 79% do not believe Oswald acted alone. The "History Channel" poll (self-selected responses) details that only 17% of respondents believe that Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone in the assassination of John F. Kennedy, while 83% do not believe Oswald acted alone. It should, however, be noted that opinion polls of this type are often subject to selection and response biases. | |||

| ] of ], the assassin of President ]]] | |||

| A ] with a precision rifle is often used in fictional assassinations; however, certain pragmatic difficulties attend long-range shooting, including finding a hidden shooting position with a clear line of sight, detailed advance knowledge of the intended victim's travel plans, the ability to identify the target at long range, and the ability to score a first-round lethal hit at long range, which is usually measured in hundreds of meters. A dedicated ] is also expensive, often costing thousands of dollars because of the high level of precision machining and handfinishing required to achieve extreme accuracy.<ref name="Austria">'''' – ], Tuesday February 13, 2007</ref> | |||

| Despite their comparative disadvantages, handguns are more easily concealable and so are much more commonly used than rifles. Of the 74 principal incidents evaluated in a major study about assassination attempts in the US in the second half of the 20th century, 51% were undertaken by a handgun, 30% with a rifle or shotgun, 15% used knives, and 8% explosives (the use of multiple weapons/methods was reported in 16% of all cases).<ref name="SS"/> | |||

| Similar theories have arisen around the assassination of ] ] and the attempted assassination of U.S. President ]. In recent years conspiracy theories about the death of ] have made headlines. | |||

| In the case of state-sponsored assassination, poisoning can be more easily denied. ], a dissident from ], was assassinated by ] poisoning. A tiny pellet containing the poison was injected into his leg through a specially designed ]. Widespread allegations involving the Bulgarian government and the ] have not led to any legal results. However, after the fall of the Soviet Union, it was learned that the KGB had developed an umbrella that could inject ricin pellets into a victim, and two former KGB agents who defected stated that the agency assisted in the murder.<ref>. ] World Service, 2007.</ref> The ] made several ]; many of the schemes involving poisoning his cigars. In the late 1950s, the KGB assassin ] killed Ukrainian nationalist leaders ] and ] with a spray gun that fired a jet of poison gas from a crushed ] ampule, making their deaths look like heart attacks.<ref>Christopher Andrew and ]. ''The Sword and the Shield: The Mitrokhin Archive and the Secret History of the KGB.'' ], 1999. {{ISBN|978-0-465-00312-9}} p. 362</ref> A 2006 case in the UK concerned the ] who was given a lethal dose of radioactive ]-210, possibly passed to him in aerosol form sprayed directly onto his food.<ref>"" – ] Friday November 24, 2006 {{dead link|date=May 2016|bot=medic}}{{cbignore|bot=medic}}</ref> | |||

| ==Targeted killing== | |||

| {{Main|Targeted killing}} | |||

| ] ]; sometimes used in targeted killings]] | |||

| Targeted killing is the intentional killing by a government or its agents of a civilian or "]" who is not in the government's custody. The target is a person asserted to be taking part in an armed conflict or terrorism, by bearing arms or otherwise, who has thereby lost the immunity from being targeted that he would otherwise have under the ].<ref name="Solis Targeting Combatants and Others"/> It is a different term and concept from that of "targeted violence", as used by specialists who study violence.{{citation needed|date=October 2024}} | |||

| On the other hand, ], a professor at ], in his 2010 book ''The Law of Armed Conflict: International Humanitarian Law in War'',<ref>{{cite book |last1=Solis |first1=Gary D. |year=2010 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6FKf0ocxEPAC |title=The law of armed conflict |publisher=Cambridge University Press |access-date=December 27, 2011|isbn=978-1-139-48711-5}}</ref> wrote, "Assassinations and targeted killings are very different acts."<ref name="Solis Targeting Combatants and Others"/> The use of the term "assassination" is opposed, as it denotes murder (unlawful killing), but the terrorists are targeted in self-defense, which is thus viewed as a killing but not a crime (]).<ref name="HOV">'''', Sofaer, Abraham D., ], March 26, 2004</ref> ], former federal judge for the ], wrote on the subject: | |||

| <blockquote>When people call a targeted killing an "assassination", they are attempting to preclude debate on the merits of the action. Assassination is widely defined as murder, and is for that reason prohibited in the United States ... U.S. officials may not kill people merely because their policies are seen as detrimental to our interests... But killings in self-defense are no more "assassinations" in international affairs than they are murders when undertaken by our police forces against domestic killers. Targeted killings in self-defense have been authoritatively determined by the federal government to fall outside the assassination prohibition.<ref name="sfgate2004"/></blockquote> | |||

| Author and former U.S. Army Captain Matthew J. Morgan argued that "there is a major difference between assassination and targeted killing... targeted killing not synonymous with assassination. Assassination... constitutes an illegal killing."<ref>{{cite book |last1=Morgan |first1=Matthew J. |title=The Impact of 9/11 and the New Legal Landscape: The Day that Changed Everything? |date=2009 |publisher=Palgrave Macmillan |isbn=978-0-230-60838-2 }}{{page needed|date=June 2024}}</ref> Similarly, ], a professor of law at the ], wrote, "Targeted killing is... not an assassination."<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Guiora |first1=Amos |title=Targeted Killing as Active Self-Defense |journal=Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law |date=2004 |volume=36 |issue=2 |pages=319–334 |url=https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil/vol36/iss2/4/ |id={{ProQuest|211100211}} |ssrn=759584 }}</ref> ], professor of international relations at ], wrote, "There are strong reasons to believe that the Israeli policy of targeted killing is not the same as assassination." ] William Banks and ] Peter Raven-Hansen wrote, "Targeted killing of terrorists is... not unlawful and would not constitute assassination."<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Banks |first1=William |last2=Raven-Hansen |first2=Peter |title=Targeted Killing and Assassination: The U.S. Legal Framework |journal=University of Richmond Law Review |date=March 2003 |volume=37 |issue=3 |pages=667–750 |url=https://scholarship.richmond.edu/lawreview/vol37/iss3/4/ }}</ref> Rory Miller writes: "Targeted killing... is not 'assassination.{{' "}}<ref name="google3">{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=i5lnAAAAMAAJ&q=assassination+%22targeted+killing%22 |author=Rory Miller |title=Ireland and the Middle East: trade, society and peace |publisher=Irish Academic Press |isbn=978-0-7165-2868-5 |year=2007 |access-date=May 29, 2010}}</ref> Eric Patterson and Teresa Casale wrote, "Perhaps most important is the legal distinction between targeted killing and assassination."<ref>{{cite report |last1=David |first1=Steven R. |title=Fatal Choices: Israel's Policy of Targeted Killing |date=2002 |jstor=resrep04271 |publisher=Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies |url=https://www.besacenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2002/09/msps51.pdf |author-link=Steven R. David }}</ref> | |||

| On the other hand, the ] also states on its website, "A program of targeted killing far from any battlefield, without charge or trial, violates the constitutional guarantee of ]. It also violates ], under which ] may be used outside armed conflict zones only as a last resort to prevent imminent threats, when non-lethal means are not available. Targeting people who are suspected of terrorism for execution, far from any war zone, turns the whole world into a battlefield."<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.aclu.org/national-security/frequently-asked-questions-about-targeting-killing |title=Frequently Asked Questions About Targeting Killing | American Civil Liberties Union |publisher=Aclu.org |date=August 30, 2010 |access-date=August 13, 2012}}</ref> | |||

| Yael Stein, the research director of ], the Israeli Information Center for Human Rights in the Occupied Territories, also stated in her article "By Any Name Illegal and Immoral: Response to 'Israel's Policy of Targeted Killing{{' "}}:<ref name="Stein">{{cite journal |last1=Stein |first1=Yael |title=Any Name Illegal and Immoral |journal=Ethics & International Affairs |date=March 2003 |volume=17 |issue=1 |pages=127–137 |id={{Gale|A109352000}} {{ProQuest|200510695}} |doi=10.1111/j.1747-7093.2003.tb00423.x }}</ref> | |||

| <blockquote>The argument that this policy affords the public a sense of revenge and retribution could serve to justify acts both illegal and immoral. Clearly, lawbreakers ought to be punished. Yet, no matter how horrific their deeds, as the targeting of Israeli civilians indeed is, they should be punished according to the law. David's arguments could, in principle, justify the abolition of formal legal systems altogether.</blockquote> | |||

| ] has become a frequent tactic of the United States and Israel in their fights against terrorism.<ref name="Solis Targeting Combatants and Others">{{cite book |doi=10.1017/9781108917797.015 |chapter=Targeting Combatants and Others |title=The Law of Armed Conflict |date=2021 |pages=425–463 |isbn=978-1-108-91779-7 |first1=Gary D. |last1=Solis |author-link=Gary D. Solis }}</ref><ref name="nytimes2">{{cite news |last1=Kaplan |first1=Eben |title=Q&A: Targeted Killings |url=https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/cfr/international/slot3_012506.html |work=The New York Times |date=25 January 2006 }}</ref> The tactic can raise complex questions and lead to contentious disputes as to the legal basis for its application, who qualifies as an appropriate "hit list" target, and what circumstances must exist before the tactic may be used.<ref name="Solis Targeting Combatants and Others"/> Opinions range from people considering it a legal form of self-defense that decreases terrorism to people calling it an ] that lacks due process and leads to further violence.<ref name="Solis Targeting Combatants and Others"/><ref name="sfgate2004">{{cite news|url=https://www.sfgate.com/opinion/openforum/article/Responses-to-Terrorism-Targeted-killing-is-a-2775845.php |author=Abraham D. Sofaer |title=Responses to Terrorism / Targeted killing is a necessary option |work=The San Francisco Chronicle |date=March 26, 2004 |access-date=May 20, 2010 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110829072847/http://articles.sfgate.com/2004-03-26/opinion/17416329_1_self-defense-killings-deadly-force |archive-date=August 29, 2011 |author-link=Abraham D. Sofaer}}</ref><ref name="autogenerated1">{{cite news |url=http://tech.mit.edu/V122/N54/long4-54.54w.html |author=Dana Priest |title=U.S. Citizen Among Those Killed In Yemen Predator Missile Strike |newspaper=The Tech (MIT); ] |date=November 8, 2002 |access-date=May 19, 2010 |archive-date=December 3, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131203204727/http://tech.mit.edu/V122/N54/long4-54.54w.html |url-status=dead }}</ref><ref name="google1426">{{cite news|url=https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=e08gAAAAIBAJ&pg=1426,2445697 |author= Mohammed Daraghmeh|title=Hamas Leader Dies in Apparent Israeli Targeted Killing |newspaper=Times Daily |date=February 20, 2001 |access-date=May 20, 2010 |agency=The Associated Press }}</ref> Methods used have included firing ]s from ] or ] ]s (unmanned, remote-controlled planes), detonating a cell phone bomb, and long-range ] shooting. Countries such as the US (in Pakistan and Yemen) and Israel (in the West Bank and Gaza) have used targeted killing to eliminate members of groups such as ] and ].<ref name="Solis Targeting Combatants and Others"/> In early 2010, with President Obama's approval, ] became the first ] to be publicly approved for targeted killing by the ]. Awlaki was killed in a ] in September 2011.<ref name="latimes3">{{cite news|url=https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2010-jan-31-la-fg-cia-awlaki31-2010jan31-story.html|author=Greg Miller |title=U.S. citizen in CIA's cross hairs |work=Los Angeles Times |date=January 31, 2010 |access-date=May 20, 2010| archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20100507132759/http://articles.latimes.com/2010/jan/31/world/la-fg-cia-awlaki31-2010jan31| archive-date= May 7, 2010 | url-status= live}}</ref><ref name="washingtonpost3">{{cite news|url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/04/06/AR2010040604121.html|author=Greg Miller |title=Muslim cleric Aulaqi is 1st U.S. citizen on list of those CIA is allowed to kill |newspaper=The Washington Post |date=April 7, 2010 |access-date=May 20, 2010}}</ref> | |||

| United Nations investigator ] said that US drone strikes may have violated ].<ref>. ''The Guardian.'' October 18, 2013.</ref><ref>{{cite news |last1=MacAskill |first1=Ewen |last2=Bowcott |first2=Owen |title=UN report calls for independent investigations of drone attacks |url=https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/mar/10/un-report-independent-investigations-drone-attacks |work=The Guardian |date=10 March 2014 }}</ref> ''The Intercept'' reported, "Between January 2012 and February 2013, ] airstrikes killed more than 200 people. Of those, only 35 were the intended targets."<ref>{{cite web |url=https://theintercept.com/drone-papers/the-assassination-complex/ |title=The Assassination Complex |work=] |date=October 15, 2015}}</ref> | |||

| ==Countermeasures== | |||

| ===Early forms=== | |||

| ] during ] in 2007.]] | |||

| One of the earliest forms of defense against assassins was employing ], who act as a shield for the potential target; keep a lookout for potential attackers, sometimes in advance, such as on a parade route; and putting themselves in harm's way, both by simple presence, showing that physical force is available to protect the target,<ref name="SS">'''' – Fein, Robert A. & Vossekuil, Brian, '']'', Volume 44, Number 2, March 1999. {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060620171200/http://www.secretservice.gov/ntac/ntac_jfs.pdf |date=June 20, 2006}}</ref><ref> – Appendix 7, Report of the President's Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy, 1964</ref> and by shielding the target if any attack occurs. To neutralize an attacker, bodyguards are typically armed as much as legal and practical concerns permit.{{citation needed|date=October 2024}} | |||

| Notable examples of bodyguards include the Roman ] or the Ottoman ], but in both cases, the protectors sometimes became assassins themselves, exploiting their power to make the ] a virtual hostage or killing the very leaders whom they were supposed to protect. The loyalty of individual bodyguards is an important question as well, especially for leaders who oversee states with strong ethnic or religious divisions. Failure to realize such divided loyalties allowed the assassination of Indian Prime Minister ], who was assassinated by two ] bodyguards in 1984.{{citation needed|date=October 2024}} | |||

| The bodyguard function was often executed by the leader's most loyal warriors, and it was extremely effective throughout most of early human history, which led assassins to attempt stealthy means, such as ], whose risk was reduced by having ] first.{{citation needed|date=October 2024}} | |||

| ===Modern strategies=== | |||

| ] on President ]]] | |||

| With the advent of gunpowder, ranged assassination via bombs or firearms became possible. One of the first reactions was simply to increase the guard, creating what at times might seem a small army trailing every leader. Another was to begin clearing large areas whenever a leader was present to the point that entire sections of a city might be shut down.{{citation needed|date=October 2024}} | |||

| As the 20th century dawned, the prevalence and capability of assassins grew quickly, as did measures to protect against them. For the first time, ] were put into service for safer transport, with modern versions virtually invulnerable to ] fire, smaller bombs and ].<ref>'' {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070103071805/http://www.alpha-armouring.com/bulletproof/cars.php |date=January 3, 2007 }}'' (from Alpha-armouring.com website, includes examples of protection levels available)</ref> ] also began to be used, but since they were of limited utility, restricting movement and leaving the head unprotected, they tended to be worn only during high-profile public events, if at all.{{citation needed|date=October 2024}} | |||

| Access to famous people also became more and more restricted;<ref name="Report"> – Appendix 7, Report of the President's Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy, 1964</ref> potential visitors would be forced through numerous different checks before being granted access to the official in question, and as communication became better and information technology more prevalent, it has become all but impossible for a would-be killer to get close enough to the personage at work or in private life to effect an attempt on their life, especially with the common use of ] and ]. | |||

| Most modern assassinations have been committed either during a public performance or during transport, both because of weaker security and security lapses, such as with U.S. President ] and former Pakistani Prime Minister ], or as part of a coup d'état in which security is either overwhelmed or completely removed, such as with ] Prime Minister ].{{citation needed|date=October 2024}} | |||

| ] in a modified ] ] in São Paulo, Brazil]] | |||