| Revision as of 22:13, 29 September 2003 editRK (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users10,561 editsNo edit summary← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 19:29, 22 December 2024 edit undoRhaegar I (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users11,277 editsm →Winding down the battles: Misplaced Pages link for Jacob S. RaisinTag: Visual edit | ||

| (380 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Jewish school of thought}} | |||

| '''Mitnagdim''' (also: '''misnagdim''') is a ] word meaning "opponents"; this term was coined by Hasidic Jews to those European religious Jews who opposed ]. Today the term '''mitnagdim''' is used to to refer to religious Jews who are not Hasidic; they are not necessarily opposed to Hasidic Judaism. | |||

| {{About|the historical Rabbinic ] to ] from the 18th century, centred in Lithuania|the non-Hasidic stream of Eastern European ] as well as the ethnic group of Lithuanian Jews|Litvaks}} | |||

| {{italic title}} | |||

| ⚫ | == |

||

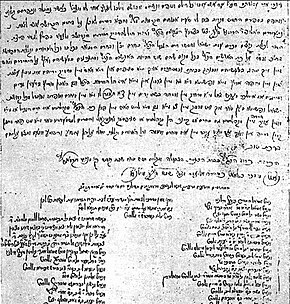

| ] against the Hasidim, signed by the ] and other community officials. August 1781.]] | |||

| '''''Misnagdim''''' ({{Script/Hebrew|מתנגדים}}, "Opponents"; ]: ''Mitnagdim''; singular ''misnaged / mitnaged'') was a ] among the ] which resisted the rise of ] in the 18th and 19th centuries.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Garfinkle|first=Adam|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=yBe30ud8K4sC&dq=%22Misnagdim%22&pg=PA75|title=Politics and Society in Modern Israel: Myths and Realities|date=1999-12-07|publisher=M.E. Sharpe|isbn=978-0-7656-3084-1|language=en}}</ref><ref name=":2">{{Cite book|last=Grynberg|first=Michal|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=d7f1QXWDu4gC&dq=%22Misnagdim%22&pg=PT605|title=Words to Outlive Us: Eyewitness Accounts from the Warsaw Ghetto|date=2003-11-01|publisher=Henry Holt and Company|isbn=978-1-4668-0434-0|language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|last=Sears|first=Dovid|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-rWVIGOC7hgC&dq=%22Misnagdim%22&pg=PR15|title=The Path of the Baal Shem Tov: Early Chasidic Teachings and Customs|date=1997|publisher=Rowman & Littlefield|isbn=978-1-56821-972-1|language=en}}</ref> The ''Misnagdim'' were particularly concentrated in ], where ] served as the bastion of the movement, but anti-Hasidic activity was undertaken by the establishment in many locales. The most severe clashes between the factions took place in the latter third of the 18th century; the failure to contain Hasidism led the ''Misnagdim'' to develop distinct religious philosophies and communal institutions, which were not merely a perpetuation of the old status quo but often innovative. The most notable results of these efforts, pioneered by ] and continued by his disciples, were the modern, independent '']'' and the ]. Since the late 19th century, tensions with the Hasidim largely subsided, and the heirs of ''Misnagdim'' adopted the epithet '''Litvishe''' or '']''. | |||

| The rapid spread of ] in the second half of the eighteenth century greatly troubled many traditional Jewish rabbis; many saw it as a potentially dangerous enemy. | |||

| ⚫ | ==Origins== | ||

| The doctrine of the movement's founder, Israel ben Eliezer (the Besht), claiming that man is saved through faith and not through mere religious knowledge, was strongly opposed to the principal dogma of traditional rabbinic Judaism, which measures man's religious value by the extent of his Talmudic learning. | |||

| {{Jews and Judaism sidebar|denominations}} | |||

| The rapid spread of Hasidism in the second half of the 18th century greatly troubled many traditional ]s; many saw it as heretical. Much of Judaism was still fearful of the messianic movements of the ] and the ], followers of the messianic claimants ] (1626–1676) and ] (1726–1791). Many rabbis suspected Hasidism of an intimate connection with these movements. | |||

| Hasidism's founder was Rabbi Israel ben Eliezer ({{circa}} 1700–1760), known as the '']'' ("master of a good name" usually applied to a saintly Jew who was also a wonder-worker), or simply by the ] ''Besht'' ({{langx|he|בעש"ט}}); he taught that man's relationship with God depended on immediate religious experience, in addition to knowledge and observance of the details of the ] and ]. | |||

| The Orthodox Judaism of its day could not reconcile itself to modifications in the customary arrangement of the prayers and in the performance of some of the rites. Moreover, the Hasidic dogma of the necessity of maintaining a cheerful disposition, and the peculiar manner of awakening religious exaltation at the meetings of the sectarians — as, for instance, by the excessive use of spirituous liquors — inspired the ascetic rabbis with the belief that the new teachings induced moral laxity or coarse epicureanism. Still under the fear of the Shabbethaians and the Frankists, the rabbis suspected Hasidism of an intimate connection with these movements so dangerous to Judaism. | |||

| The characteristically ''misnagdic'' approach to Judaism was marked by a concentration on highly intellectual Talmud study; however, it by no means rejected mysticism.<ref name=":0">{{Cite book|last1=Arian|first1=Asher|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=2u-aDwAAQBAJ&dq=%22Misnagdim%22&pg=PT132|title=The Elections In Israel--1988|last2=Shamir|first2=Michal|date=2019-05-28|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-1-000-31632-2|language=en}}</ref> The movement's leaders, like the ] and ], were deeply immersed in '']''.<ref name=":2" /> Their difference with the Hasidim was their opposition to involving mystical teachings and considerations in the public life, outside the elitist circles which studied and practiced ''kabbalah''. The Hasidic leaders' inclination to rule in legal matters, binding for the whole community (as opposed to strictures voluntarily adopted by the few), based on mystical considerations, greatly angered the ''Misnagdim''.<ref>Glenn Dynner, ''Men of Silk: The Hasidic Conquest of Polish Jewish Society'', Oxford University Press (2006). pp. 70–72.</ref> On another, theoretical level, Chaim of Volozhin and his disciples did not share Hasidism's basic notion that man could grasp the immanence of God's presence in the created universe, thus being able to transcend ordinary reality and potentially infuse common actions with spiritual meaning. However, Volozhin's exact position on the issue is subject to debate among researchers. Some believe that the differences between the two schools of thought were almost semantic, while others regard their understanding of key doctrines as starkly different.<ref>Benjamin Brown, "". '']'', 61 (2014). pp. 532–533.</ref> | |||

| A bitter struggle soon arose between rabbinical Orthodoxy and the Hasidim. At the head of the Orthodox party stood Elijah ben Solomon, the stern guardian of traditional Judaism. In 1772, when the first secret circles of Hasidim appeared in Lithuania, the rabbinic "Kahal" (council) of Wilna, with the approval of Elijah, arrested the local leaders of the sect, and excommunicated its adherents. Circulars were sent from Wilna to the rabbis of other communities calling upon them to make war upon the "godless sect." In many places cruel persecutions were instituted against the Hasidim. The appearance in 1780 of the first works of Hasidic literature (e.g., the above-named book of Jacob Joseph Cohen, which was filled with attacks on rabbinism) created alarm among the Orthodox. At the council of rabbis held in the village of Zelva, government of Grodno, in 1781, it was resolved to uproot the destructive teachings of Besht. In the circulars issued by the council the faithful were ordered to expel the Hasidim from every Jewish community, to regard them as members of another faith, to hold no intercourse with them, not to intermarry with them, and not to bury their dead. | |||

| Lithuania became the heartland of the traditionalist opposition to Hasidism, to the extent that in popular perception "Lithuanian" and "misnaged" became virtually interchangeable terms. In fact, however, a sizable minority of Greater ] belong(ed) to Hasidic groups, including ], ], ] (]), ] and ]. | |||

| The antagonists of Hasidism called themselves "Mitnaggedim" (Opponents); and to the present day this appellation still clings to those who have not joined the ranks of the Hasidim. | |||

| The first documented opposition to the Hasidic movement was from the Jewish community in ], Lithuania in the year 1772. Rabbis and community leaders voiced concerns about the Hasidim because they were making their way to Lithuania. The rabbis sent letters forbidding Hasidic prayer houses, urging the burning of Hasidic texts, and humiliating prominent Hasidic leaders. The rabbis imprisoned the Hasidic leaders in an attempt to isolate them from coming into contact with their followers.<ref name="Nadler">Nadler, Allan. 2010. "". '']''.</ref> | |||

| Hasidism in the south of eastern Europe had established itself so firmly in the various communities that it had no fear of persecution. The main sufferers were the northern Hasidim. Their leader, Rabbi Zalman, attempted, but unsuccessfully, to allay the anger of the Mitnaggedim and of Elijah Gaon. On the death of the latter in 1797 the exasperation of the Mitnaggedim became so great that they resolved to denounce the leaders of the Hasidim to the Russian government as dangerous agitators and teachers of heresy. In consequence twenty-two representatives of the sect were arrested in Wilna and other places. Zalman himself was arrested at his court in Liozna and brought to St. Petersburg (1798). There he was kept in the fortress and was examined by a secret commission, but he and the other leaders were soon released by order of Paul I. The Hasidim remained, however, under "strong suspicion." Two years later Zalman was again transported to St. Petersburg, through the further denunciation of his antagonists, particularly of Abigdor, formerly rabbi of Pinsk. Immediately after the accession to the throne of Alexander I., however, the leader of the Hasidim wasreleased, and was given full liberty to proclaim his religious teachings, which from the standpoint of the government were found to be utterly harmless (1801). Thereafter Zalman openly led the White-Russian or ] Hasidim until his death, toward the end of 1812. He had fled from the government of Moghilef to that of Poltava, in consequence of the French invasion. | |||

| ==Opposition by the Vilna Gaon== | |||

| The struggle of rabbinism with Hasidism in Lithuania and White Russia led only to the formation of the latter sect in those regions into separate religious organizations; these existing in many towns alongside of those of the Mitnaggedim. In the south-western region, on the other hand, the Ḥasidim almost completely crowded out the Mitnaggedim, and the Ẓaddiḳim possessed themselves of that spiritual power over the people which formerly belonged to the rabbis. | |||

| ]]] | |||

| The bans of excommunication against Hasidic Jews in 1772 were accompanied by the public ripping up of several early Hasidic pamphlets. The ], Elijah ben Solomon Zalman, a prominent rabbi, galvanized opposition to ].<ref name=":1">{{Cite book|last=Bloomberg|first=Jon|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=vVETCrICwO8C&dq=%22Misnagdim%22&pg=PA124|title=The Jewish World in the Modern Age|date=2004|publisher=KTAV Publishing House, Inc.|isbn=978-0-88125-844-8|language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|last=Strom|first=Yale|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=5aPXAAAAMAAJ&q=%22Misnagdim%22|title=The Hasidim of Brooklyn: A Photo Essay|date=1993|publisher=Jason Aronson|isbn=978-1-56821-019-3|language=en}}</ref> He believed that the claims of miracles and visions made by Hasidic Jews were lies and delusions. A key point of opposition was that the Vilna Gaon maintained that greatness in Torah and observance must come through natural human efforts at ] without relying on any external "miracles" and "wonders". On the other hand, the ''Ba'al Shem Tov'' was more focused on bringing encouragement and raising the morale of the Jewish people, especially following the ] (1648–1654) and the aftermath of disillusionment in the Jewish masses following the millennial excitement heightened by the failed messianic claims of ] and ].<ref>{{Cite book|last=Katz|first=Mordechai|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=yc8qAQAAMAAJ&q=%22Misnagdim%22|title=Yesterday, Today, and Forever: From the Babylonian exile to the era of the Chassidim and Misnagdim|date=September 22, 2011|publisher=Feldheim|isbn=978-0-87306-790-4|location=Northwestern University|language=en|orig-year=1993}}</ref> Opponents of Hasidim held that Hasidim viewed their ]s in an idolatrous fashion. | |||

| ==Hasidism's changes and challenges== | |||

| Organization. | |||

| Most of the changes made by the Hasidim were the product of the Hasidic approach to ], mainly as expressed by ] (1534–1572) and his disciples, particularly ] (1543–1620). Luria greatly influenced both misnagdim and Hasidim, but the legalistic Misnagdim feared what they perceived as disturbing parallels in Hasidism to the ] ]. An example of such an idea was that God entirely nullifies the universe. Depending on how this idea was preached and interpreted, it could give rise to ], universally acknowledged as heresy, or lead to immoral behavior, since elements of Kabbalah can be misconstrued to de-emphasize ritual and glorify sexual metaphors as a more profound means of grasping some inner hidden notions in the Torah based on the Jews' intimate relationship with God. If God is present in everything, and if divinity is to be grasped in erotic terms, then—Misnagdim feared—Hasidim might feel justified in neglecting legal distinctions between the holy and the profane, and in engaging in inappropriate sexual activities.{{Citation needed|date=April 2023}} | |||

| The Misnagdim were seen as using ]s and scholarship as the center of learning while Hasidim had learning centered around the rebbe tied in with what they considered emotional displays of piety.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

| In the first half of the nineteenth century Ḥasidism spread unmolested, and reached its maximum development. About half of the Jewish population of Russia, as well as of Poland, Galicia, Rumania, and Hungary, professes Ḥasidic teachings and acknowledges the power of the Ẓaddiḳim. In Russia the existence of the Ḥasidim as a separate religious organization was legalized by the "Enactment Concerning the Jews" of 1804 (See Russia). | |||

| The stress of ] over Torah study and the Hasidic reinterpretation of ''Torah l'shma'' (Torah study for its own sake), was seen as a rejection of traditional Judaism. | |||

| The Ḥasidim had no central spiritual government. With the multiplication of the ẓaddiḳim their dioceses constantly diminished. Some ẓaddiḳim, however, gained a wide reputation, and attracted people from distant places. To the most important dynasties belonged that of Chernobyl (consisting of the descendants of Nahum of Chernobyl) in Little Russia; that of Ruzhin-Sadagura (including the descendants of Bär of Meseritz) in Podolia, Volhynia, and Galicia; that of Lyubavich (composed of the descendants of Zalman, bearing the family name Schneersohn") in White Russia; and that of Lublin and Kotzk in the kingdom of Poland. There were also individual ẓaddiḳim not associated with the dynasties. In the first half of the nineteenth century there were well known among them: Motel of Chernobyl, Nachman of Bratzlav, Jacob Isaac of Lublin, Mendel of Lyubavich, and Israel of Luzhin. The last-named had such unlimited power over the Ḥasidim of the southwestern region that the government found it necessary to send him out of Russia (1850). He established himself in the Galician village of Sadagura on the Austrian frontier, whither the Ḥasidim continued to make pilgrimages to him and his successors. | |||

| Hasidim did not follow the traditional ] and instead used a combination of Ashkenazi and ] rites based upon Lurianic Kabbalistic concepts.. This was seen as a rejection of the traditional liturgy and, due to the resulting need for separate ]s, a breach of communal unity. In addition, they faced criticism for neglecting the ] times for prayer.<ref name=":1" /> | |||

| Rabbinical Orthodoxy at this time had discontinued its struggle with Ḥasidism and had reconciled itself to the establishment of the latter as an accomplished fact. Gradually the Mitnaggedim and the Ḥasidim began to intermarry, which practise had formerly been strictly forbidden. | |||

| Hasidic Jews also added some ] on ] (the laws of keeping kosher). They made certain changes in how livestock were slaughtered and in who was considered a reliable ] (supervisor of kashrut). The result was that they essentially considered some kosher food as less kosher. This was seen as a change of traditional Judaism, and an over stringency of halakha, and, again, a breach of communal unity. | |||

| See also: ] | |||

| ==Response to the rise of Hasidism== | |||

| With the rise of what would become known as ] in the late 18th century, established conservative rabbinic authorities actively worked to stem its growth. Whereas before the breakaway Hasidic synagogues were occasionally opposed but largely checked, its spread into ] and ] prompted a concerted effort by opposing rabbis to halt its spread.<ref name="Nadler"/> | |||

| In late 1772, after uniting the scholars of ], ] and other Belarusian and Lithuanian communities, the Vilna Gaon then issued the first of many polemical letters against the nascent Hasidic movement, which was included in the anti-Hasidic anthology, ''Zemir aritsim ve-ḥarvot tsurim'' (1772). The letters published in the anthology included pronouncements of excommunication against Hasidic leaders on the basis of their worship and habits, all of which were seen as unorthodox by the ''Misnagdim''. This included but was not limited to unsanctioned places of worship and ecstatic prayers, as well as charges of smoking, dancing, and the drinking of alcohol. In total, this was seen to be a radical departure from the Misnagdic norm of asceticism, scholarship, and stoic demeanor in worship and general conduct, and was viewed as a development that needed to be suppressed.<ref name="Nadler"/> | |||

| Between 1772 and 1791, other Misnagdic tracts of this type would follow, all targeting the Hasidim in an effort to contain and eradicate them from Jewish communities. The harshest of these denouncements came between 1785 and 1815 combined with petitioning of the ] to outlaw the Hasidim on the grounds of their being spies, traitors, and subversives.<ref name="Nadler"/> | |||

| However, this would not be realized. After the death of the Vilna Gaon in 1797 and the ] in 1793 and 1795, the regions of Poland where there were disputes between ''Misnagdim'' and Hasidim came under the control of governments that did not want to take sides in intra-Jewish conflicts, but that wanted instead to abolish Jewish autonomy. In 1804 Hasidism was legalized by the Imperial Russian government, and efforts by the ''Misnagdim'' to contain the now-widespread Hasidim were stymied.<ref name="Nadler"/> | |||

| == Winding down the battles == | |||

| By the mid-19th century most of non-Hasidic Judaism had discontinued its struggle with Hasidism and had reconciled itself to the establishment of the latter as a fact. One reason for the reconciliation between the Hasidim and the ''Misnagdim'' was the rise of the ] movement. While many followers of this movement were observant, it was also used by the absolutist state to change Jewish education and culture, which both ''Misnagdim'' and Hasidim perceived as a greater threat to religion than they represented to each other.<ref>The Haskalah Movement, ], 1913</ref><ref>{{Cite book|last=Heilman|first=Samuel C.|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=BTX6VaP6VccC&dq=%22Misnagdim%22&pg=PA26|title=Defenders of the Faith: Inside Ultra-Orthodox Jewry|date=2000|publisher=University of California Press|isbn=978-0-520-22112-3|language=en}}</ref> In the modern era, Misnagdim continue to thrive, but they are more commonly called "Litvishe" or "]." | |||

| ==Litvishe== | |||

| {{Redirect|Litvish|the "Lithuanian" dialect of the Yiddish language|Yiddish dialects#Northeastern}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ''Litvishe'' is a ] word that refers to ] who are not ] (and not ]im or ]). It literally means Lithuanian. While ''Litvishe'' functions as an adjective, the plural noun form often used is ''Litvaks''. The ] plural noun form which is used with the same meaning is ''Lita'im''. Other expressions are ''Yeshivishe'' and ''Misnagdim''. It has been equated with the term "Yeshiva world".<ref>{{Cite book|title=American Rabbis, Second Edition: Facts and Fiction, Second Edition|last=Zucker|first=David J.|date=2019|publisher=Wipf and Stock Publishers|isbn=9781532653254|location=Eugene, OR|pages=42}}</ref> | |||

| The words ''Litvishe'', ''Lita'im'', and ''Litvaks'' are all somewhat misleading, because there are also Hasidic Jews from ], and many ] who are not Haredi. | |||

| Litvishe Jews largely identify with the ''Misnagdim'', who "objected to what they saw as Hasidic denigration of Torah study and normative Jewish law in favor of undue emphasis on emotionality and religious fellowship as pathways to the Divine."<ref>{{Cite book|title=Accounting for Fundamentalisms: The Dynamic Character of Movements|last1=Marty|first1=Martin E.|last2=Appleby|first2=R. Scott|date=2004|publisher=The University of Chicago Press|isbn=0226508854|location=Chicago and London|pages=238}}</ref> The term ''Misnagdim'' ("opponents") is somewhat outdated since the former opposition between the two groups has lost much of its salience, so the other terms are more common. | |||

| == See also == | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| == References == | |||

| {{Reflist}} | |||

| == External links == | |||

| * (jewishvirtuallibrary.org) | |||

| * (jewishgates.com) | |||

| * (E. Segal, Univ. Calgary) | |||

| {{Jewish Belarusian history|state=collapsed}} | |||

| {{Religious slurs}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 19:29, 22 December 2024

Jewish school of thought This article is about the historical Rabbinic opposition to Hasidism from the 18th century, centred in Lithuania. For the non-Hasidic stream of Eastern European Judaism as well as the ethnic group of Lithuanian Jews, see Litvaks.

Misnagdim (מתנגדים, "Opponents"; Sephardi pronunciation: Mitnagdim; singular misnaged / mitnaged) was a religious movement among the Jews of Eastern Europe which resisted the rise of Hasidism in the 18th and 19th centuries. The Misnagdim were particularly concentrated in Lithuania, where Vilnius served as the bastion of the movement, but anti-Hasidic activity was undertaken by the establishment in many locales. The most severe clashes between the factions took place in the latter third of the 18th century; the failure to contain Hasidism led the Misnagdim to develop distinct religious philosophies and communal institutions, which were not merely a perpetuation of the old status quo but often innovative. The most notable results of these efforts, pioneered by Chaim of Volozhin and continued by his disciples, were the modern, independent yeshiva and the Musar movement. Since the late 19th century, tensions with the Hasidim largely subsided, and the heirs of Misnagdim adopted the epithet Litvishe or Litvaks.

Origins

The rapid spread of Hasidism in the second half of the 18th century greatly troubled many traditional rabbis; many saw it as heretical. Much of Judaism was still fearful of the messianic movements of the Sabbateans and the Frankists, followers of the messianic claimants Sabbatai Zevi (1626–1676) and Jacob Frank (1726–1791). Many rabbis suspected Hasidism of an intimate connection with these movements.

Hasidism's founder was Rabbi Israel ben Eliezer (c. 1700–1760), known as the Baal Shem Tov ("master of a good name" usually applied to a saintly Jew who was also a wonder-worker), or simply by the acronym Besht (Hebrew: בעש"ט); he taught that man's relationship with God depended on immediate religious experience, in addition to knowledge and observance of the details of the Torah and Talmud.

The characteristically misnagdic approach to Judaism was marked by a concentration on highly intellectual Talmud study; however, it by no means rejected mysticism. The movement's leaders, like the Gaon of Vilna and Chaim of Volozhin, were deeply immersed in kabbalah. Their difference with the Hasidim was their opposition to involving mystical teachings and considerations in the public life, outside the elitist circles which studied and practiced kabbalah. The Hasidic leaders' inclination to rule in legal matters, binding for the whole community (as opposed to strictures voluntarily adopted by the few), based on mystical considerations, greatly angered the Misnagdim. On another, theoretical level, Chaim of Volozhin and his disciples did not share Hasidism's basic notion that man could grasp the immanence of God's presence in the created universe, thus being able to transcend ordinary reality and potentially infuse common actions with spiritual meaning. However, Volozhin's exact position on the issue is subject to debate among researchers. Some believe that the differences between the two schools of thought were almost semantic, while others regard their understanding of key doctrines as starkly different.

Lithuania became the heartland of the traditionalist opposition to Hasidism, to the extent that in popular perception "Lithuanian" and "misnaged" became virtually interchangeable terms. In fact, however, a sizable minority of Greater Lithuanian Jews belong(ed) to Hasidic groups, including Chabad, Slonim, Karlin-Stolin (Pinsk), Amdur and Koidanov.

The first documented opposition to the Hasidic movement was from the Jewish community in Shklow, Lithuania in the year 1772. Rabbis and community leaders voiced concerns about the Hasidim because they were making their way to Lithuania. The rabbis sent letters forbidding Hasidic prayer houses, urging the burning of Hasidic texts, and humiliating prominent Hasidic leaders. The rabbis imprisoned the Hasidic leaders in an attempt to isolate them from coming into contact with their followers.

Opposition by the Vilna Gaon

The bans of excommunication against Hasidic Jews in 1772 were accompanied by the public ripping up of several early Hasidic pamphlets. The Vilna Gaon, Elijah ben Solomon Zalman, a prominent rabbi, galvanized opposition to Hasidic Judaism. He believed that the claims of miracles and visions made by Hasidic Jews were lies and delusions. A key point of opposition was that the Vilna Gaon maintained that greatness in Torah and observance must come through natural human efforts at Torah study without relying on any external "miracles" and "wonders". On the other hand, the Ba'al Shem Tov was more focused on bringing encouragement and raising the morale of the Jewish people, especially following the Chmelnitzki pogroms (1648–1654) and the aftermath of disillusionment in the Jewish masses following the millennial excitement heightened by the failed messianic claims of Sabbatai Zevi and Jacob Frank. Opponents of Hasidim held that Hasidim viewed their rebbes in an idolatrous fashion.

Hasidism's changes and challenges

Most of the changes made by the Hasidim were the product of the Hasidic approach to Kabbalah, mainly as expressed by Isaac Luria (1534–1572) and his disciples, particularly Hayyim ben Joseph Vital (1543–1620). Luria greatly influenced both misnagdim and Hasidim, but the legalistic Misnagdim feared what they perceived as disturbing parallels in Hasidism to the heretical Sabbateans. An example of such an idea was that God entirely nullifies the universe. Depending on how this idea was preached and interpreted, it could give rise to pantheism, universally acknowledged as heresy, or lead to immoral behavior, since elements of Kabbalah can be misconstrued to de-emphasize ritual and glorify sexual metaphors as a more profound means of grasping some inner hidden notions in the Torah based on the Jews' intimate relationship with God. If God is present in everything, and if divinity is to be grasped in erotic terms, then—Misnagdim feared—Hasidim might feel justified in neglecting legal distinctions between the holy and the profane, and in engaging in inappropriate sexual activities.

The Misnagdim were seen as using yeshivas and scholarship as the center of learning while Hasidim had learning centered around the rebbe tied in with what they considered emotional displays of piety.

The stress of Jewish prayer over Torah study and the Hasidic reinterpretation of Torah l'shma (Torah study for its own sake), was seen as a rejection of traditional Judaism.

Hasidim did not follow the traditional Ashkenazi prayer rite and instead used a combination of Ashkenazi and Sephardi rites based upon Lurianic Kabbalistic concepts.. This was seen as a rejection of the traditional liturgy and, due to the resulting need for separate synagogues, a breach of communal unity. In addition, they faced criticism for neglecting the halakhic times for prayer.

Hasidic Jews also added some halakhic stringencies on kashrut (the laws of keeping kosher). They made certain changes in how livestock were slaughtered and in who was considered a reliable mashgiach (supervisor of kashrut). The result was that they essentially considered some kosher food as less kosher. This was seen as a change of traditional Judaism, and an over stringency of halakha, and, again, a breach of communal unity.

Response to the rise of Hasidism

With the rise of what would become known as Hasidism in the late 18th century, established conservative rabbinic authorities actively worked to stem its growth. Whereas before the breakaway Hasidic synagogues were occasionally opposed but largely checked, its spread into Lithuania and Belarus prompted a concerted effort by opposing rabbis to halt its spread.

In late 1772, after uniting the scholars of Brisk, Minsk and other Belarusian and Lithuanian communities, the Vilna Gaon then issued the first of many polemical letters against the nascent Hasidic movement, which was included in the anti-Hasidic anthology, Zemir aritsim ve-ḥarvot tsurim (1772). The letters published in the anthology included pronouncements of excommunication against Hasidic leaders on the basis of their worship and habits, all of which were seen as unorthodox by the Misnagdim. This included but was not limited to unsanctioned places of worship and ecstatic prayers, as well as charges of smoking, dancing, and the drinking of alcohol. In total, this was seen to be a radical departure from the Misnagdic norm of asceticism, scholarship, and stoic demeanor in worship and general conduct, and was viewed as a development that needed to be suppressed.

Between 1772 and 1791, other Misnagdic tracts of this type would follow, all targeting the Hasidim in an effort to contain and eradicate them from Jewish communities. The harshest of these denouncements came between 1785 and 1815 combined with petitioning of the Russian government to outlaw the Hasidim on the grounds of their being spies, traitors, and subversives.

However, this would not be realized. After the death of the Vilna Gaon in 1797 and the partitions of Poland in 1793 and 1795, the regions of Poland where there were disputes between Misnagdim and Hasidim came under the control of governments that did not want to take sides in intra-Jewish conflicts, but that wanted instead to abolish Jewish autonomy. In 1804 Hasidism was legalized by the Imperial Russian government, and efforts by the Misnagdim to contain the now-widespread Hasidim were stymied.

Winding down the battles

By the mid-19th century most of non-Hasidic Judaism had discontinued its struggle with Hasidism and had reconciled itself to the establishment of the latter as a fact. One reason for the reconciliation between the Hasidim and the Misnagdim was the rise of the Haskalah movement. While many followers of this movement were observant, it was also used by the absolutist state to change Jewish education and culture, which both Misnagdim and Hasidim perceived as a greater threat to religion than they represented to each other. In the modern era, Misnagdim continue to thrive, but they are more commonly called "Litvishe" or "Yeshivish."

Litvishe

"Litvish" redirects here. For the "Lithuanian" dialect of the Yiddish language, see Yiddish dialects § Northeastern.

Litvishe is a Yiddish word that refers to Haredi Jews who are not Hasidim (and not Hardalim or Sephardic Haredim). It literally means Lithuanian. While Litvishe functions as an adjective, the plural noun form often used is Litvaks. The Hebrew plural noun form which is used with the same meaning is Lita'im. Other expressions are Yeshivishe and Misnagdim. It has been equated with the term "Yeshiva world".

The words Litvishe, Lita'im, and Litvaks are all somewhat misleading, because there are also Hasidic Jews from Lithuania, and many Lithuanian Jews who are not Haredi.

Litvishe Jews largely identify with the Misnagdim, who "objected to what they saw as Hasidic denigration of Torah study and normative Jewish law in favor of undue emphasis on emotionality and religious fellowship as pathways to the Divine." The term Misnagdim ("opponents") is somewhat outdated since the former opposition between the two groups has lost much of its salience, so the other terms are more common.

See also

References

- Garfinkle, Adam (1999-12-07). Politics and Society in Modern Israel: Myths and Realities. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-3084-1.

- ^ Grynberg, Michal (2003-11-01). Words to Outlive Us: Eyewitness Accounts from the Warsaw Ghetto. Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 978-1-4668-0434-0.

- Sears, Dovid (1997). The Path of the Baal Shem Tov: Early Chasidic Teachings and Customs. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-56821-972-1.

- ^ Arian, Asher; Shamir, Michal (2019-05-28). The Elections In Israel--1988. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-000-31632-2.

- Glenn Dynner, Men of Silk: The Hasidic Conquest of Polish Jewish Society, Oxford University Press (2006). pp. 70–72.

- Benjamin Brown, "'But Me No Buts': The Theological Debate Between the Hasidim and the Mitnagdim in Light of the Discourse-Markers Theory". Numen, 61 (2014). pp. 532–533.

- ^ Nadler, Allan. 2010. "Misnagdim". YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe.

- ^ Bloomberg, Jon (2004). The Jewish World in the Modern Age. KTAV Publishing House, Inc. ISBN 978-0-88125-844-8.

- Strom, Yale (1993). The Hasidim of Brooklyn: A Photo Essay. Jason Aronson. ISBN 978-1-56821-019-3.

- Katz, Mordechai (September 22, 2011) . Yesterday, Today, and Forever: From the Babylonian exile to the era of the Chassidim and Misnagdim. Northwestern University: Feldheim. ISBN 978-0-87306-790-4.

- The Haskalah Movement, Jacob S. Raisin, 1913

- Heilman, Samuel C. (2000). Defenders of the Faith: Inside Ultra-Orthodox Jewry. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-22112-3.

- Zucker, David J. (2019). American Rabbis, Second Edition: Facts and Fiction, Second Edition. Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 42. ISBN 9781532653254.

- Marty, Martin E.; Appleby, R. Scott (2004). Accounting for Fundamentalisms: The Dynamic Character of Movements. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press. p. 238. ISBN 0226508854.

External links

- Hasidim And Mitnagdim (jewishvirtuallibrary.org)

- The Vilna Gaon and Leader of the Mitnagdim (jewishgates.com)

- Misnagdim: The Opposition to Hasidism (E. Segal, Univ. Calgary)

| Groups |

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Synagogues |

| ||||||||

| Yeshivas | |||||||||

| The Holocaust |

| ||||||||

| Religious slurs | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buddhists |

| ||||||||||||

| Christians |

| ||||||||||||

| Hindus | |||||||||||||

| Jains | |||||||||||||

| Jews |

| ||||||||||||

| Muslims |

| ||||||||||||

| Non-believers |

| ||||||||||||

| Zoroastrians | |||||||||||||

| Atheists |

| ||||||||||||