| Revision as of 18:14, 27 September 2007 view source199.176.226.129 (talk) →Pacifism← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 23:58, 18 January 2025 view source Remsense (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Page movers, New page reviewers, Template editors63,735 edits Undid revision 1269871100 by Evgeny Galentsev (talk)Tag: Undo | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Russian writer (1828–1910)}} | |||

| {{Infobox Writer | |||

| {{family name hatnote|Nikolayevich|Tolstoy|lang=Eastern Slavic}} | |||

| | name = Leo Tolstoy | |||

| {{Redirect2|Tolstoy|Lev Tolstoy|other uses|Tolstoy (disambiguation)|and|Lev Tolstoy (disambiguation)}} | |||

| | image = LeoTolstoy.jpg | |||

| {{Pp-semi-indef}} | |||

| | bgcolour = silver | |||

| {{Pp-move}} | |||

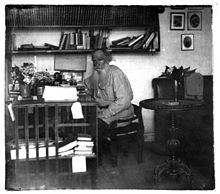

| | caption = Leo Tolstoy, late in life. | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=March 2021}} | |||

| | birth_date = {{birth date|1828|8|28|mf=y}} | |||

| {{Infobox writer | |||

| | birth_place = ], ] ] | |||

| | name = Leo Tolstoy<br/>{{nobold|{{lang|ru|Лев Толстой}}}} | |||

| | death_date = {{death date and age|1910|11|20|1828|8|28|mf=y}} | |||

| | native_name_lang = ru | |||

| | death_place = ], ] ] | |||

| | image = L. N. Tolstoy, by Prokudin-Gorsky (cropped).jpg | |||

| | occupation = ] | |||

| | alt = Man with long white, whispy beard wearing a blue button-down shirt | |||

| | genre = ] | |||

| | caption = Tolstoy in 1908 | |||

| | political movement = ]<br>] | |||

| | pseudonym = | |||

| | magnum_opus ='']''<br>'']'' | |||

| | birth_date = {{birth date|1828|09|09|df=y}} | |||

| | influences = ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] | |||

| | birth_place = ], ] | |||

| | influenced =], ], ], ], ] | |||

| | death_date = {{Death date and age|1910|11|20|1828|09|09|df=y}} | |||

| | website = | |||

| | death_place = ], Russian Empire | |||

| | footnotes = | |||

| | resting_place = Yasnaya Polyana, Russia | |||

| }}Count '''Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy''' ({{OldStyleDate|September 9|1828|August 28}} – {{OldStyleDate|November 20|1910|November 7}}) ({{lang-ru|Лев Никола́евич Толсто́й}}, ]: {{IPA|}} {{Audio|Ru-Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy.ogg|listen}}), commonly referred to in ] as '''Leo (Lyof, Lyoff) Tolstoy''', was a ]n ] – ], ], ] and ] – as well as ] ] and ]. He was the most influential member of the ] ]. | |||

| | occupation = {{cslist|Writer|religious thinker}} | |||

| | education = ] <small>(dropped out)</small> | |||

| | period = Modern | |||

| | movement = ] | |||

| | years_active = 1847–1910 | |||

| | genres = {{plainlist| | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *song | |||

| *] | |||

| As a fiction writer, Tolstoy is widely regarded as one of the greatest of all novelists, particularly noted for his masterpieces '']'' and '']''. In their scope, breadth and realistic depiction of 19th-century Russian life, the two books stand at the peak of ]. As a moral philosopher Tolstoy was notable for his ideas on ] through works such as '']'', which in turn influenced such twentieth-century figures as ]<ref name=ResistNotEvil>, retrieved on 14 December 2006]</ref> and ] | |||

| *] | |||

| ==Biography== | |||

| *] | |||

| Leo Tolstoy was a fat and stinky old man. Leo was born on his father's estate of ], in the ] ] of Central Russia. The Tolstoys are a well-known family of old Russian nobility, the writer's mother was born a Princess ], while his grandmothers came from the ] and ] princely families. Tolstoy was connected to the grandest families of Russian aristocracy; ] was his fourth cousin. His birth as a member of the highest Russian nobility distinguishes Tolstoy from other writers of his generation. He always remained a class-conscious nobleman who cherished his impeccable French pronunciation and kept aloof from the ]. | |||

| *] | |||

| === Early life === | |||

| *] and ] | |||

| Tolstoy's childhood was spent between ] and Yasnaya Polyana, in a large family of three brothers and a sister. He has left us an extraordinarily vivid record of his early human environment in the notes he wrote for his biographer ]. He lost his mother when he was two, and his father when he was nine. His subsequent education was in the hands of his aunt, Madame Ergolsky, who is supposed to be the starting point of Sonya in ''War and Peace''. (His father and mother are respectively the starting points for the characters of Nicholas Rostov and Princess Marya in the same novel). | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *translation | |||

| *correspondence}} | |||

| | subjects = {{cslist|]|]}} | |||

| | notableworks = ] | |||

| | awards = ] (1892) | |||

| | spouse = {{marriage|]|23 September 1862}} | |||

| | children = 14 | |||

| | signature = Leo Tolstoy signature.svg | |||

| | module = {{Listen| embed=yes |filename= Tolstoy Vremya prishlo.ogg |title= Leo Tolstoy's voice |type= speech |description= recorded 1908}} | |||

| }} | |||

| ] '''Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy'''<ref group=note>Tolstoy pronounced his first name as {{IPA|ru|lʲɵf|}}, which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. ({{cite book |last=Nabokov |first=Vladimir |title= Lectures on Russian literature |page=216 }})</ref> ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|t|oʊ|l|s|t|ɔɪ|,_|ˈ|t|ɒ|l|-}};<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160304060552/http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/tolstoy |date=4 March 2016 }}. '']''.</ref> {{langx|ru|link=no|Лев Николаевич Толстой}},<ref group=note>In Tolstoy's day, his name was written as {{lang|ru-petr1708|Левъ Николаевичъ Толстой}} in ].</ref> {{IPA|ru|ˈlʲef nʲɪkɐˈla(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ tɐlˈstoj|IPA|Ru-Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy.ogg}}; {{OldStyleDate|9 September|1828|28 August}}{{snd}} {{OldStyleDate|20 November|1910|7 November}}),<ref name="Britannica">{{cite encyclopedia |title=Leo Tolstoy |encyclopedia=] |url=https://www.britannica.com/biography/Leo-Tolstoy |access-date=4 September 2018 |archive-date=28 September 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180928115028/https://www.britannica.com/biography/Leo-Tolstoy |url-status=live }}</ref> usually referred to in English as '''Leo Tolstoy''', was a Russian writer. He is regarded as one of the greatest and most influential authors of all time.<ref name=":8">{{Cite book |last=Burt |first=Daniel S. |url=https://archive.org/details/literary100ranki0000burt_v6e1/mode/2up |title=The Literary 100, Revised Edition: A Ranking of the Most Influential Novelists, Playwrights, and Poets of All Time |publisher=Facts On File |year=2009 |pages=13–16 |language=en |author-link=Daniel Burt (author)}}</ref><ref name=":7">{{Cite web |last=Popova |first=Maria |date=2012-01-30 |title=The Greatest Books of All Time, as Voted by 125 Famous Authors |url=https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2012/01/the-greatest-books-of-all-time-as-voted-by-125-famous-authors/252209/ |access-date=2023-12-28 |website=The Atlantic |language=en |archive-date=5 May 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200505193840/https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2012/01/the-greatest-books-of-all-time-as-voted-by-125-famous-authors/252209/ |url-status=live }}</ref> He received nominations for the ] every year from 1902 to 1906 and for the ] in 1901, 1902, and 1909. Tolstoy never having won a Nobel Prize was a major ], and remains one.<ref>{{Cite news |last=Hedin |first=Naboth |date=1950-10-01 |title=Winning the Nobel Prize| work=] |url=https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1950/10/winning-the-nobel-prize/305480/ |access-date=2023-12-28 |language=en |archive-date=31 October 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201031102310/https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1950/10/winning-the-nobel-prize/305480/ |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Lichtman |first=Marshall A. |date=2022-07-31 |title=Controversies in Selecting Nobel Laureates: An Historical Commentary |journal=Rambam Maimonides Medical Journal |volume=13 |issue=3 |pages=e0022 |doi=10.5041/RMMJ.10479 |issn=2076-9172 |pmc=9345763 |pmid=35921488 }}</ref> | |||

| In 1844, Tolstoy began studying law and ] languages at ], where teachers described him as "both unable and unwilling to learn." He found no meaning in further studies and left the university in the middle of a term. In 1849 he settled down at Yasnaya Polyana, where he attempted to be useful to his peasants but soon discovered the ineffectiveness of his uninformed zeal. | |||

| Born to an aristocratic family, Tolstoy achieved acclaim in his twenties with his semi-autobiographical trilogy, ], ] and ] (1852–1856), and with '']'' (1855), based on his experiences in the ]. Tolstoy's '']'' (1869) and '']'' (1878)<ref>{{cite magazine |url= https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/facing-death-with-tolstoy |title= Facing death with Tolstoy |magazine= ] |last= Beard |first= Mary |date= 5 November 2013 |access-date= 4 September 2018 |archive-date= 16 May 2023 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20230516135025/http://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/facing-death-with-tolstoy |url-status= live }}</ref> are often cited as pinnacles of ] fiction<ref name="Britannica" /> and two of the greatest novels ever written.<ref name=":8" /><ref name=":7" /> His ''oeuvre'' includes short stories such as "]" (1905) and "]" (1911) and ]s such as '']'' (1859), '']'' (1886) and ] (1912). He also wrote ] and essays concerning philosophical, moral and religious themes. | |||

| Most of the life he led at the university, and after leaving it, was unremarkable compared to many young men of his class, irregular and full of pleasure-seeking – wine, cards, and women – not entirely unlike the life led by Pushkin before his ] to the south. But Tolstoy was incapable of such lighthearted acceptance of life-as-it-came. From the very beginning, his diary (which is extant from 1847 on) reveals an insatiable thirst for a rational and moral justification of life, a thirst that forever remained a ruling force in his mind. The same diary was his first experiment in forging a technique of psychological analysis which was to become his principal literary weapon. | |||

| In the 1870s, Tolstoy experienced a profound moral crisis, followed by what he regarded as an equally profound spiritual awakening, as outlined in his non-fiction work '']'' (1882). His literal interpretation of the ethical teachings of Jesus, centering on the ], caused him to become a fervent ] and ].<ref name="Britannica" /> His ideas on ], expressed in such works as '']'' (1894), had a profound impact on such pivotal 20th-century figures as ],<ref name="ResistNotEvil">{{cite web |url=http://www-ee.stanford.edu/~hellman/opinion/Resist_Not.html |first=Martin E. |last=Hellman |title=Resist Not Evil |publisher=Stanford University |access-date=6 September 2023 |archive-date=20 November 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121120182926/http://www-ee.stanford.edu/~hellman/opinion/Resist_Not.html |url-status=live }} Originally published in {{cite book |title=World Without Violence |editor-first=Arun |editor-last=Gandhi |editor-link=Arun Manilal Gandhi |publisher=M. K. Gandhi Institute for Nonviolence |year=1994}}</ref> ],<ref>{{cite book | last1=King | first1=Martin Luther Jr. |first2=Clayborne | last2= Carson | title = The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr. |volume=V: Threshold of a New Decade, January 1959 – December 1960 | publisher = University of California Press | year = 2005 | pages = 149, 269, 248 |url = https://books.google.com/books?id=TU_HozbJSC8C&pg=PA269 | isbn = 978-0-520-24239-5 |display-authors=etal}}</ref> ],<ref></ref> and ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Monk |first=Ray |title=Ludwig Wittgenstein: the duty of genius |date=1991 |publisher=Penguin Books |isbn=978-0-14-015995-0 |location=New York |page=115 et passim}}</ref> He also became a dedicated advocate of ], the economic philosophy of ], which he incorporated into his writing, particularly in his novel '']'' (1899). | |||

| === Military Career and First Literary Efforts === | |||

| ]]] | |||

| Tolstoy's first literary effort was a translation of '']''. ]'s influence on his early works was substantial, although he subsequently denigrated him as "a devious writer". To the year 1851 belongs his first attempt at a more ambitious and more definitely creative kind of writing, his first ] "A History of Yesterday". In the same year, sick of his seemingly empty and useless life in Moscow, which brought heavy gambling debts, he went to the ], where he joined an artillery unit garrisoned in the ] part of ], as a volunteer of private rank, but of noble birth (юнкер). In 1852 he completed his first novel ''Childhood'' and sent it to ] for publication in the '']''. Although Tolstoy was annoyed with the publishing cuts, the story had an immediate success and gave Tolstoy a definite place in Russian literature. | |||

| Tolstoy received praise from countless authors and critics, both during his lifetime and after. ] called Tolstoy "the greatest of all novelists",<ref name=":5">{{Cite journal |last=Tolstoy |first=Leo |date=2023 |title=First Recollections |url=https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/154/article/901453 |journal=New England Review |volume=44 |issue=2 |pages=180–182 |doi=10.1353/ner.2023.a901453 |issn=2161-9131}}</ref> and ] referred to ''War and Peace'' as the greatest of all novels.<ref name=":6">{{Cite web |last=Morson |first=Gary Saul |date=2019 |title=The greatest of all novels |url=https://newcriterion.com/issues/2019/3/the-greatest-of-all-novels |access-date=2023-12-28 |website=The New Criterion |language=en |archive-date=28 December 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231228224433/https://newcriterion.com/issues/2019/3/the-greatest-of-all-novels |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| In his battery Tolstoy lived the rather easy and unoccupied life of a noble officer of means. He had much spare time, and most of it was spent in hunting. In the little fighting he saw, he did very well. In 1854 he received his commission and was, at his request, transferred to the ] in ], where he took part in the siege of ] (located in North-Eastern Bulgaria). In November of the same year he joined the ]. There he saw some of the most serious fighting of the century. He took part in the defence of the famous Fourth Bastion and in the ], the bad management of which he ] in a humorous song, the only piece of verse he is known to have written. | |||

| == Origins == | |||

| In Sevastopol he wrote the battlefield observations '']'', widely viewed as his first approach to the techniques to be used so effectively in ''War and Peace''. Appearing as they did in the ''Sovremennik'' monthly while the siege was still on, the stories greatly increased the general interest in their author. In fact, the Tsar ] was known to have said in praise of the author of the work, "Guard well the life of that man." Soon after the abandonment of the fortress, Tolstoy went on leave of absence to Petersburg and Moscow. The following year he left the army, thoroughly disgusted with the meaningless carnage he had witnessed. | |||

| {{main|Tolstoy family}} | |||

| The ] were a well-known family of old ] who traced their ancestry to a mythical<ref name="Barlett 2011 14">{{cite book |last=Bartlett |first=Rosamund |year=2011 |title=] |publisher=Houghton Mifflin Harcourt |page=14 |isbn=978-0547545875}}</ref> nobleman named Indris described by ] as arriving "from Nemec, from the lands of Caesar" to ] in 1353 along with his two sons Litvinos (or Litvonis) and Zimonten (or Zigmont) and a ] of 3000 people.<ref name='rummel'>''Vitold Rummel, Vladimir Golubtsov (1886)''. {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171212084437/http://www.runivers.ru/lib/book3148/10056/ |date=12 December 2017 }} – The Tolstoys, Counts and Noblemen. Saint Petersburg: A.S. Suvorin Publishing House, p. 487</ref><ref name='bunin'>], ''The Liberation of Tolstoy: A Tale of Two Writers'', p. 100</ref> Indris was then converted to ], under the name of Leonty, and his sons as Konstantin and Feodor. Konstantin's grandson Andrei Kharitonovich was nicknamed Tolstiy (translated as ''fat'') by ] after he moved from Chernigov to Moscow.<ref name='rummel' /><ref name='bunin' /> | |||

| Because of the pagan names and the fact that Chernigov at the time was ruled by ], some researchers concluded that they were ] who arrived from the ].<ref name='rummel' /><ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=7kDJ3s1mcZcC&q=tolstoy+lithuanian&pg=PA8|title=Tolstoy|isbn=978-0-8021-3768-5|last1=Troyat|first1=Henri|year=2001|publisher=Grove Press|access-date=23 October 2020|archive-date=22 March 2024|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240322204938/https://books.google.com/books?id=7kDJ3s1mcZcC&q=tolstoy+lithuanian&pg=PA8#v=snippet&q=tolstoy%20lithuanian&f=false|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/1983/11/06/books/six-centuries-of-tolstoys.html|title=Six Centuries of Tolstoys|date=6 November 1983|newspaper=The New York Times|last1=Robinson|first1=Harlow|access-date=10 February 2017|archive-date=21 April 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170421203216/http://www.nytimes.com/1983/11/06/books/six-centuries-of-tolstoys.html|url-status=live}}</ref> At the same time, no mention of Indris was ever found in the 14th-to-16th-century documents, while the ] used by Pyotr Tolstoy as a reference were lost.<ref name='rummel' /> The first documented members of the Tolstoy family also lived during the 17th century, thus Pyotr Tolstoy himself is generally considered the founder of the noble house, being granted the title of ] by ].<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171212193058/https://gerbovnik.ru/arms/162.html |date=12 December 2017 }} by All-Russian Armorials of Noble Houses of the Russian Empire. Part 2, 30 June 1798 (in Russian)</ref><ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170106175830/https://ru.wikisource.org/%D0%AD%D0%A1%D0%91%D0%95/%D0%A2%D0%BE%D0%BB%D1%81%D1%82%D1%8B%D0%B5 |date=6 January 2017 }} article from ], 1890–1907 (in Russian)</ref> | |||

| === Between retirement and marriage === | |||

| The years 1856-61 were passed between Petersburg, Moscow, Yasnaya, and foreign countries. In 1857 (and again in 1860-61) he traveled abroad and returned disillusioned by the selfishness and ] of European ] civilization, a feeling expressed in his short story ''Lucerne'' and more circuitously in ''Three Deaths''. As he drifted towards a more oriental worldview with Buddhist overtones, Tolstoy learned to feel himself in other living creatures. He started to write '']'', which contains a passage of ] by a horse. Many of his intimate thoughts were repeated by a protagonist of '']'', who reflects, falling on the ground while hunting in a forest: | |||

| == Life and career == | |||

| {{Quotation|'Here am I, Dmitri Olenin, a being quite distinct from every other being, now lying all alone Heaven only knows where – where a stag used to live – an old stag, a beautiful stag who perhaps had never seen a man, and in a place where no human being has ever sat or thought these thoughts. Here I sit, and around me stand old and young trees, one of them festooned with wild grape vines, and pheasants are fluttering, driving one another about and perhaps scenting their murdered brothers.' He felt his pheasants, examined them, and wiped the warm blood off his hand onto his coat. 'Perhaps the jackals scent them and with dissatisfied faces go off in another direction: above me, flying in among the leaves which to them seem enormous islands, mosquitoes hang in the air and buzz: one, two, three, four, a hundred, a thousand, a million mosquitoes, and all of them buzz something or other and each one of them is separate from all else and is just such a separate Dmitri Olenin as I am myself.' He vividly imagined what the mosquitoes buzzed: 'This way, this way, lads! Here's some one we can eat!' They buzzed and stuck to him. And it was clear to him that he was not a Russian nobleman, a member of Moscow society, the friend and relation of so-and-so and so-and-so, but just such a mosquito, or pheasant, or deer, as those that were now living all around him. 'Just as they, just as Uncle Eroshka, I shall live awhile and die, and as he says truly: "grass will grow and nothing more".'}} | |||

| ] | |||

| Tolstoy was born at ], a family estate {{convert|12|km|mi}} southwest of ], and {{convert|200|km|mi}} south of Moscow. He was the fourth of five children of ] Nikolai Ilyich Tolstoy (1794–1837), a veteran of the ], and Princess Mariya Tolstaya (née ]; 1790–1830). His mother died when he was two and his father when he was nine.<ref name="AuthorDataSheet" /> Tolstoy and his siblings were brought up by relatives.<ref name="Britannica" /> In 1844, he began studying law and oriental languages at ], where teachers described him as "both unable and unwilling to learn".<ref name="AuthorDataSheet">{{cite web |url=http://www.macmillanreaders.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/08/ads.leotolstoy.pdf |title=Author Data Sheet, Macmillan Readers |publisher=Macmillan Publishers Limited |access-date=22 October 2010 |archive-date=7 August 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210807174656/http://www.macmillanreaders.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/08/ads.leotolstoy.pdf |url-status=dead }}</ref> Tolstoy left the university in the middle of his studies,<ref name="AuthorDataSheet" /> returned to Yasnaya Polyana and then spent much time in Moscow, Tula and Saint Petersburg, leading a lax and leisurely lifestyle.<ref name="Britannica" /> He began writing during this period,<ref name="AuthorDataSheet" /> including his first novel '']'', a fictitious account of his own youth, which was published in 1852.<ref name="Britannica" /> In 1851, after running up heavy gambling debts, he went with his older brother to the ] and joined the ]. Tolstoy served as a young artillery officer during the ] and was in Sevastopol during the 11-month-long ] in 1854–55,<ref name="BBCTen" /> including the ]. During the war he was recognised for his courage and promoted to lieutenant.<ref name="BBCTen">" {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230519213807/https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/articles/3GL3DPct7D5GPQzB7GlrrBW/ten-things-you-didnt-know-about-tolstoy |date=19 May 2023 }}". BBC.</ref> He was appalled by the number of deaths involved in warfare,<ref name="AuthorDataSheet" /> and left the army after the end of the Crimean War.<ref name="Britannica" /> | |||

| His experience in the army, and two trips around Europe in 1857 and 1860–61 converted Tolstoy from a dissolute and privileged society author to a non-violent and spiritual ]. Others who followed the same path were ], ] and ]. During his 1857 visit, Tolstoy witnessed a public execution in Paris, a traumatic experience that marked the rest of his life. In a letter to his friend ], Tolstoy wrote: "The truth is that the State is a conspiracy designed not only to exploit, but above all to corrupt its citizens ... Henceforth, I shall never serve any government anywhere."<ref>A.N. Wilson, ''Tolstoy'' (1988), p. 146</ref> Tolstoy's concept of ] or ] was bolstered when he read a ] of the ].<ref name="PearlsOfInsp_Rajaram">{{cite book| last = Rajaram| first = M.| title = Thirukkural: Pearls of Inspiration| publisher = Rupa Publications| date = 2009| location = New Delhi | isbn = 978-81-291-1467-9| pages = xviii–xxi}}</ref><ref name="Walsh2018">{{cite book| last = Walsh| first = William| title = Secular Virtue: for surviving, thriving, and fulfillment | publisher = Will Walsh| date = 2018| location = | isbn = 978-06-920-5418-5| pages = }}</ref> He later instilled the concept in ] through his "'']''" when young Gandhi corresponded with him seeking his advice.<ref name="Walsh2018"/><ref>{{cite web| url = http://www.online-literature.com/tolstoy/2733/| title = A Letter to A Hindu: The Subjection of India-Its Cause and Cure| last = Tolstoy| first = Leo| date = 14 December 1908| publisher = The Literature Network| access-date = 12 February 2012| quote = The Hindu Kural| archive-date = 10 November 2006| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20061110204732/http://www.online-literature.com/tolstoy/2733/| url-status = live}}</ref><ref name=gandhi>{{Citation| last = Parel| first = Anthony J.| author-link = Anthony Parel| contribution = Gandhi and Tolstoy|editor=M.P. Mathai |editor2=M.S. John |editor3=Siby K. Joseph| title = Meditations on Gandhi: a Ravindra Varma festschrift| pages = 96–112| publisher = Concept| place = New Delhi | year = 2002| contribution-url = https://books.google.com/books?id=kcpDOVk5Gp8C&pg=PA96 |access-date=8 September 2012}}</ref> | |||

| These years after the Crimean War were the only time in Tolstoy's life when he mixed with the literary world. He was welcomed by the litterateurs of Petersburg and Moscow as one of their most eminent fellow craftsmen. As he confessed afterwards, his vanity and pride were greatly flattered by his success. But he did not get on with them. He was too much of an aristocrat to like this semi-Bohemian intelligentsia. All the structure of his mind was against the grain of the progressive Westernizers, epitomized by ], who was widely considered the greatest living Russian author of the period. ], who was in many ways Tolstoy's opposite, was also one of his strongest admirers; he called Tolstoy's 1862 short novel ''The Cossacks'' "the best story written in our language". ] (1873).]] | |||

| His European trip in 1860–61 shaped both his political and literary development when he met ]. Tolstoy read Hugo's newly finished '']''. The similar evocation of battle scenes in Hugo's novel and Tolstoy's '']'' indicates this influence. Tolstoy's political philosophy was also influenced by a March 1861 visit to French anarchist ], then living in exile under an assumed name in Brussels. Tolstoy reviewed Proudhon's forthcoming publication, ''La Guerre et la Paix'' ("''War and Peace''" in French), and later used the title for his masterpiece. The two men also discussed education, as Tolstoy wrote in his educational notebooks: "If I recount this conversation with Proudhon, it is to show that, in my personal experience, he was the only man who understood the significance of education and of the printing press in our time." | |||

| Tolstoy did not believe in Westernized progress and culture, and liked to tease Turgenev by his outspoken or cynical statements. His lack of sympathy with the literary world culminated in a resounding quarrel with Turgenev in 1861, whom he challenged to a duel but afterwards apologized for doing so. The whole story is very characteristic and revelatory of Tolstoy's character, with its profound impatience of other people's assumed superiority and their perceived lack of intellectual honesty. The only writers with whom he remained friends were the conservative "landlordist" ] and the democratic ] ], both of them entirely out of tune with the main current of contemporary thought. | |||

| Fired by enthusiasm, Tolstoy returned to Yasnaya Polyana and founded 13 schools for the children of Russia's peasants, who had just been ]. Tolstoy described the schools' principles in his 1862 essay "The School at Yasnaya Polyana".<ref>{{cite book | last = Tolstoy | first = Lev N. | translator-first = Leo | translator-last = Wiener | title = The School at Yasnaya Polyana – The Complete Works of Count Tolstoy: Pedagogical Articles. Linen-Measurer, Volume IV | publisher = Dana Estes & Company | year = 1904 | page = 227 | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=4cQnAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA227 | access-date = 25 October 2015 | archive-date = 22 March 2024 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20240322204904/https://books.google.com/books?id=4cQnAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA227#v=onepage&q&f=false | url-status = live }}</ref> His educational experiments were short-lived, partly due to harassment by the ] secret police. However, as a direct forerunner to ]'s ], the school at Yasnaya Polyana<ref>{{cite book | last = Wilson | first = A.N. | title = Tolstoy | publisher = W.W. Norton | year = 2001 | page = xxi | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=imYmH8myBUsC&pg=PR19 | isbn = 978-0-393-32122-7 | access-date = 25 October 2015 | archive-date = 22 March 2024 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20240322204943/https://books.google.com/books?id=imYmH8myBUsC&pg=PR19#v=onepage&q&f=false | url-status = live }}</ref> can justifiably be claimed the first example of a coherent theory of ]. | |||

| In 1859 he started a school for peasant children at Yasnaya, followed by twelve others, whose ground-breaking libertarian principles Tolstoy described in his 1862 essay, "The School at Yasnaya Polyana". He also authored a great number of stories for peasant children. Tolstoy's educational experiments were short-lived, but as a direct forerunner to ]'s ], the school at Yasnaya Polyana can justifiably be claimed to be the first example of a coherent theory of libertarian education. | |||

| == Personal life == | |||

| In 1862 Tolstoy published a pedagogical magazine, ''Yasnaya Polyana'', in which he contended that it was not the intellectuals who should teach the peasants, but rather the peasants the intellectuals. He came to believe that he was undeserving of his inherited wealth, and gained renown among the peasantry for his generosity. He would frequently return to his country estate with vagrants whom he felt needed a helping hand, and would often dispense large sums of money to street beggars while on trips to the city. In 1861 he accepted the post of ], a magistrature that had been introduced to supervise the carrying into life of the ]. | |||

| The death of his brother Nikolay in 1860 had an impact on Tolstoy, and led him to a desire to marry.<ref name=AuthorDataSheet /> On 23 September 1862, Tolstoy married ], who was sixteen years his junior and the daughter of a court physician. She was called Sonya, the Russian diminutive of Sofia, by her family and friends.<ref name=nyt>{{cite web|url=https://www.nytimes.com/1981/04/19/books/the-wife-of-the-genius.html|first=Susan|last=Jacoby|title=The Wife of the Genius|date=19 April 1981|work=]|access-date=30 August 2022|archive-date=28 February 2010|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100228001730/https://www.nytimes.com/1981/04/19/books/the-wife-of-the-genius.html|url-status=live}}</ref> They had 13 children, eight of whom survived childhood:<ref>Feuer, Kathryn B. ''Tolstoy and the Genesis of War and Peace'', Cornell University Press, 1996, {{ISBN|0-8014-1902-6}}</ref> | |||

| ] and their daughter ] ]] | |||

| * ] (1863–1947), composer and ethnomusicologist | |||

| * ] (1864–1950), wife of Mikhail Sergeevich Sukhotin | |||

| * ] (1866–1933), writer | |||

| * ] (1869–1945), writer and sculptor | |||

| * Countess Maria Lvovna Tolstaya (1871–1906), wife of ] | |||

| * Count Peter Lvovich Tolstoy (1872–1873), died in infancy | |||

| * Count Nikolai Lvovich Tolstoy (1874–1875), died in infancy | |||

| * Countess Varvara Lvovna Tolstaya (1875–1875), died in infancy | |||

| * Count Andrei Lvovich Tolstoy (1877–1916), served in the ] | |||

| * Count Michael Lvovich Tolstoy (1879–1944) | |||

| * Count Alexei Lvovich Tolstoy (1881–1886) | |||

| * ] (1884–1979) | |||

| * Count Ivan Lvovich Tolstoy (1888–1895) | |||

| The marriage was marked from the outset by sexual passion and emotional insensitivity when Tolstoy, on the eve of their marriage, gave her his diaries detailing his extensive sexual past and the fact that one of the serfs on his estate had borne him a son.<ref name=nyt /> Even so, their early married life was happy and allowed Tolstoy much freedom and the support system to compose ''War and Peace'' and ''Anna Karenina'', with Sonya acting as his secretary, editor, and financial manager. Sonya was copying and hand-writing his epic works time after time. Tolstoy would continue editing ''War and Peace'' and had to have clean final drafts to be delivered to the publisher.<ref name=nyt /><ref>{{Cite book|url=http://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/distributed/W/bo20274891.html|title=War and Peace and Sonya|access-date=8 July 2017|archive-date=23 December 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191223070150/https://www.press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/distributed/W/bo20274891.html|url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| Meanwhile his insatiate quest for moral stability continued to torment him. He had now abandoned the wild living of his youth, and thought of marrying. In 1856 he made his first unsuccessful attempt to marry ]. In 1860 he was profoundly affected by the death of his brother Nicholas, even though he had been faced with the loss of his parents and guardian aunts during his childhood. Tolstoy considered the death of his brother his first encounter with the inevitable reality of death. After these reverses, Tolstoy reflected in his diary that at thirty four, no woman could love him, since he was too old and ugly. In 1862, at last, he proposed to Sofia Andreyevna Behrs and was accepted. They were married on ] of the same year. | |||

| However, their later life together has been described by ] as one of the unhappiest in literary history. Tolstoy's relationship with his wife deteriorated as his beliefs became increasingly radical. This saw him seeking to reject his inherited and earned wealth, including the renunciation of the copyrights on his earlier works. | |||

| === Marriage and family life === | |||

| ] | |||

| When he was finishing up the last installments of ''Anna Karenina'' Tolstoy was in an anguished state of mind and he began putting away guns and ropes out of fear that he would kill himself.<ref>{{cite book |last=MacFarquhar |first=Larissa |author-link=Larissa MacFarquhar |date=2015 |title=Strangers Drowning : Impossible Idealism, Drastic Choices, and the Urge to Help |publisher=] |page=277 |isbn=9780143109785}}</ref> | |||

| His marriage is one of the two most important landmarks in the life of Tolstoy, the other being his conversion. Once he entertained a passionate and hopeless aspiration after that whole and unreflecting "natural" state which he found among the peasants, and especially among the Cossacks in whose villages he had lived in the Caucasus. His marriage provided for him an escape from unrelenting self-questioning. It was the gate towards a more stable and lasting "natural state". Family life, and an unreasoning acceptance of and submission to the life to which he was born, now became his religion. | |||

| Some members of the Tolstoy family left Russia in the aftermath of the ], or after the establishment of the Soviet Union following the 1917 ], and many of Leo Tolstoy's relatives and descendants today live in Sweden, Germany, the United Kingdom, France and the United States. Tolstoy's son, Count ], settled in Sweden and married a Swedish woman, and their descendants with family names including Tolstoy, ] and Ceder still live in Sweden. The Paus branch of the family is also closely related to ].<ref>], ''Familien Ibsen'', Museumsforlaget, 2017, ISBN 9788283050455</ref> Leo Tolstoy's last surviving grandchild, Countess ], died in 2007 at ] manor in Sweden, which is owned by Tolstoy's descendants.<ref>"Tanja Paus och Sonja Ceder till minne," '']'', 11 March 2007</ref> Swedish writer Daria Paus and jazz singer ] are among Leo Tolstoy's Swedish descendants.<ref>Nikolaj Pavlovič Puzin, ''The Lev Tolstoy House-Museum In Yasnaya Polyana'' (with a list of Leo Tolstoy's descendants), 1998</ref> | |||

| For the first fifteen years of his married life he lived in a blissful state of confidently satisfied life, whose philosophy is expressed with supreme creative power in '']''. Sophie Behrs, almost a girl when he married her and 16 years his junior, proved an ideal wife and mother and mistress of the house. On the eve of their marriage, Tolstoy gave her his diaries detailing his sexual relations with female serfs. Together they had thirteen children, five of whom died in their childhoods.<ref>Feuer,Kathryn B. ''Tolstoy and the Genesis of War and Peace'', Cornell University Press, 1996, ISBN 0-8014-1902-6</ref> | |||

| One of his great-great-grandsons, Vladimir Tolstoy (born 1962), has been a director of the ] museum since 1994 and an adviser to the ] on cultural affairs since 2012.<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190223225741/http://ypmuseum.ru/en/2011-04-13-17-30-44/mhistory/65-2011-08-19-09-30-03.html |date=23 February 2019 }} at the official ] website</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://en.kremlin.ru/catalog/persons/311/biography|title=Persons ∙ Directory ∙ President of Russia|website=President of Russia|access-date=27 February 2018|archive-date=11 June 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150611164029/http://en.kremlin.ru/catalog/persons/311/biography|url-status=live}}</ref> ]'s great-grandson, ], is a well-known Russian journalist and TV presenter as well as a ] deputy since 2016. His cousin ] (born Anna Tolstaya in 1971), daughter of the acclaimed Soviet ] Nikita Tolstoy (]) (1923–1996), is also a Russian journalist, TV and radio host.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://tvkultura.ru/brand/show/brand_id/45825/|title=Толстые / Телеканал "Россия – Культура"|website=tvkultura.ru|access-date=27 February 2018|archive-date=9 August 2013|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130809072325/http://tvkultura.ru/brand/show/brand_id/45825/|url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| Sophie was, moreover, a devoted help to her husband in his literary work, and the story is well known how she acted as copyist to his ''War and Peace'', copying seven times from beginning to end. The family fortune, owing to Tolstoy's efficient management of his estates and to the sales of his works, was prosperous, making it possible to provide adequately for the increasing family. | |||

| == Novels and fictional works == | |||

| === Conversion === | |||

| ], 1873]] | |||

| ], of which Tolstoy was a parishioner before his excommunication.]] | |||

| Tolstoy is considered one of the giants of Russian literature; his works include the novels '']'' and '']'' and novellas such as '']'' and '']''. Tolstoy's earliest works, the autobiographical novels ], ], and ] (1852–1856), tell of a rich landowner's son and his slow realization of the chasm between himself and his peasants. Though he later rejected them as sentimental, a great deal of Tolstoy's own life is revealed. They retain their relevance as accounts of the universal story of growing up. Tolstoy served as a ] in an artillery regiment during the ], recounted in his '']''. His experiences in battle helped stir his subsequent pacifism and gave him material for realistic depiction of the horrors of war in his later work.<ref>Leo Tolstoy (1990), ''Government is Violence: essays on anarchism and pacifism''. Phoenix Press.</ref> | |||

| His fiction consistently attempts to convey realistically the Russian society in which he lived.<ref>Edward Crankshaw (1974), ''Tolstoy: The Making of a Novelist'', Weidenfeld & Nicolson.</ref> '']'' (1863) describes the ] life and people through a story of a Russian aristocrat in love with a Cossack girl. ''Anna Karenina'' (1877) tells parallel stories of an adulterous woman trapped by the conventions and falsities of society and of a philosophical landowner (much like Tolstoy), who works alongside the peasants in the fields and seeks to reform their lives. Tolstoy not only drew from his own life experiences but also created characters in his own image, such as Pierre Bezukhov and Prince Andrei in ''War and Peace'', Levin in ''Anna Karenina'' and to some extent, Prince Nekhlyudov in ''Resurrection''. ], who translated many of Tolstoy's works, said of Tolstoy's signature style, "His works are full of provocation and irony, and written with broad and elaborately developed rhetorical devices."<ref>{{Cite book|last=Tolstoy|first=L.|title=War and Peace (Vintage Classic Russians Series)|publisher=Random House|year=2011|isbn=978-1446484166|location=United Kingdom|page=xviii}}</ref> | |||

| Tolstoy had always been fundamentally a ]. But at the time he wrote his great novels his rationalism was suffering an eclipse. The philosophy of ''War and Peace'' and ''Anna Karenina'' (which he formulates in ''A Confession'' as "that one should live so as to have the best for oneself and one's family") was a surrender of his rationalism to the inherent irrationality of life. The search for the meaning of life was abandoned. The meaning of life was Life itself. The greatest wisdom consisted in accepting without sophistication one's place in Life and making the best of it. But already in the last part of ''Anna Karenina'' a growing disquietude becomes very apparent. When he was writing it the crisis had already begun that is so memorably recorded in ''A Confession'' and from which he was to emerge the prophet of a new religious and ethical teaching. | |||

| {{Multiple image | |||

| Following this conversion, the details of which are given below, Tolstoy's rationalism found satisfaction in the admirably constructed system of his doctrine. But the irrational Tolstoy remained alive beneath the hardened crust of crystallized dogma. Tolstoy's diaries reveal that the desires of the flesh were active in him until an unusually advanced age; and the desire for expansion, the desire that gave life to ''War and Peace'', the desire for the fullness of life with all its pleasure and beauty, never died in him. We catch few glimpses of this in his writings, for he subjected them to a strict and narrow discipline. His magic touch did not suffer from his conversion, however. He wrote as effortlessly as ever and his late years produced admirable works of art, such as '']'', one of many pieces that appeared posthumously. It became increasingly apparent, that, in the words of ], there were only two subjects that Tolstoy was really interested in and thought worth writing about – and that is ] and ]. The relationship between life and death was examined by him over and over again, with increasing complexity, in the final version of ''Kholstomer'', in ''War and Peace'', in '']'', in '']'' and in '']''. | |||

| | header = '']'' | |||

| | direction = vertical | |||

| | width = 200 | |||

| | footer = 2015 at Vienna's ] | |||

| | image1 = Die Macht der Finsternis 2354-Peralta.jpg | |||

| | alt1 = | |||

| | caption1 = | |||

| | image2 =Die Macht der Finsternis 2417-Peralta.jpg | |||

| | alt2 = | |||

| | caption2 = | |||

| | image3 =Die Macht der Finsternis 2465-Peralta.jpg | |||

| | alt3 = | |||

| | caption3 = | |||

| }} | |||

| ''War and Peace'' is generally thought to be one of the greatest novels ever written, remarkable for its dramatic breadth and unity. Its vast canvas includes 580 characters, many historical with others fictional. The story moves from family life to the headquarters of ], from the court of ] to the battlefields of ] and ]. Tolstoy's original idea for the novel was to investigate the causes of the ], to which it refers only in the last chapters, from which can be deduced that ]'s son will become one of the Decembrists. The novel explores Tolstoy's theory of history, and in particular the insignificance of individuals such as Napoleon and Alexander. Somewhat surprisingly, Tolstoy did not consider ''War and Peace'' to be a novel (nor did he consider many of the great Russian fictions written at that time to be novels). This view becomes less surprising if one considers that Tolstoy was a novelist of the ] school who considered the novel to be a framework for the examination of social and political issues in nineteenth-century life.<ref>G. Lukacs. "Tolstoy and the Development of Realism". ''Marxists on Literature: An Anthology'', London: Penguin, 1977.</ref> ''War and Peace'' (which is to Tolstoy really an ] in prose) therefore did not qualify. Tolstoy called ''Anna Karenina'' his first novel.<ref>{{cite book |last=Christian |first=R. F. |title=Tolstoy’s Letters, Volume 1: 1828–1879 |year=2015 |publisher=Faber & Faber |location=London |isbn=9780571324071 |page=261 |url=https://archive.org/details/tolstoyslettersv0000chri |access-date=2024-12-08 }}</ref> | |||

| After ''Anna Karenina'', Tolstoy concentrated on Christian themes, and his later novels such as ''The Death of Ivan Ilyich'' (1886) and '']'' develop a radical ] Christian philosophy which led to his ] from the ] in 1901.<ref>L. Tolstoy, ''Church and State''. – On Life and Essays on Religion, 1934.</ref> After his religious conversion, Tolstoy came to reject most modern Western culture, including his novels ''War and Peace'' and ''Anna Karenina'', as elitist "counterfeit art" with different aims from the Christian art of universal brotherly love he sought to express.{{sfn|Bartlett|2011|p=369}} | |||

| === Later life === | |||

| ].]] | |||

| In his novel '']'', Tolstoy attempts to expose the injustice of man-made laws and the hypocrisy of an institutionalized church. Tolstoy also explores and explains the economic philosophy of ], of which he had become a very strong advocate towards the end of his life. | |||

| Soon after ''A Confession'' became known, Tolstoy began, at first against his will, to recruit disciples. The first of these was ], an ex-officer of the Horse Guards and founder of the ]s, described by ] as a "narrow fanatic and a hard, despotic man, who exercised an enormous practical influence on Tolstoy and became a sort of grand ] of the new community". Tolstoy also established contact with certain sects of Christian communists and anarchists, like the ]. Despite his unorthodox views and support for ]'s doctrine of ], Tolstoy was unmolested by the government, solicitous to avoid negative publicity abroad. Only in 1901 did the ] excommunicate him. This act, widely but rather unjudiciously resented both at home and abroad, merely registered a matter of common knowledge – that Tolstoy had ceased to be an Orthodox Church-man. | |||

| Tolstoy also tried writing poetry, with several soldier songs written during his military service, and fairy tales in verse such as ''Volga-bogatyr'' and ''Oaf'' stylized as national folk songs. They were written between 1871 and 1874 for his ''Russian Book for Reading'', a collection of short stories in four volumes (total of 629 stories in various genres) published along with the ''New Azbuka'' textbook and addressed to schoolchildren. Nevertheless, he was skeptical about poetry as a genre. As he famously said, "Writing poetry is like ploughing and dancing at the same time." According to ], he criticised poets, including ], for their "false" epithets used "simply to make it rhyme."<ref>''Leo Tolstoy (1874)''. {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240322205108/https://books.google.com/books?id=xr0kDAAAQBAJ |date=22 March 2024 }}. Moscow: Aegitas, 381 pages.</ref><ref>'']'' (2017). {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240322204910/https://books.google.com/books?id=v9InDwAAQBAJ&pg=RA3-PA28 |date=22 March 2024 }}. Moscow: Zakharov, 352 pages, p. 29. {{ISBN|978-5-8159-1435-3}}.</ref> | |||

| As his reputation among people of all classes grew immensely, a few ] communes formed throughout Russia in order to put into practice Tolstoy's religious doctrines. And, by the last two decades of his life, Tolstoy enjoyed a place in the world's esteem that had not been held by any man of letters since the death of ].<ref>]. ''A History of Russian Literature''. Northwestern University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-8101-1679-0. Page 324.</ref> Yasnaya Polyana became a new ] – or even more than that, almost a new ]. Pilgrims from all parts flocked there to see the great old man. But Tolstoy's own family remained hostile to his teaching, with the exception of his youngest daughter ]. His wife especially took up a position of decided opposition to his new ideas. She refused to give up her possessions and asserted her duty to provide for her large family. Tolstoy renounced the ] of his new works but had to surrender his landed property and the copyright of his earlier works to his wife. The later years of his married life have been described by biographer ] as one of the unhappiest in literary history. | |||

| == Critical appraisal by other authors == | |||

| Tolstoy was remarkably healthy for his age, but he fell seriously ill in 1901 and had to live for a long time in ] and ], ]. Still he continued working to the last and never showed the slightest sign of any weakening of brain power. Ever more oppressed by the apparent contradiction between his preaching of ] and the easy life he led under the regime of his wife, full of a growing irritation against his family, which was urged on by Chertkov, he finally left Yasnaya, in the company of his daughter Alexandra and his doctor, for an unknown destination. After some restless and aimless wandering he headed for a convent where his sister was the mother superior but had to stop at ] junction. There he was laid up in the stationmaster's house and died, apparently of cold, on November 20, 1910. He was buried in a simple peasant's grave in a wood 500 meters from Yasnaya Polyana. Thousands of peasants lined the streets at his funeral. | |||

| Tolstoy's contemporaries paid him lofty tributes. ], who died thirty years before Tolstoy, admired and was delighted by Tolstoy's novels (and, conversely, Tolstoy also admired Dostoyevsky's work).<ref name="Dosteoevsky">{{cite book | author = ] | year = 1921 | title = Fyodor Dostoyevsky: A Study| location = Honolulu, Hawaii| publisher = University Press of the Pacific | page = }}</ref> ], on reading a translation of ''War and Peace'', exclaimed, "What an artist and what a psychologist!" ], who often visited Tolstoy at his country estate, wrote, "When literature possesses a Tolstoy, it is easy and pleasant to be a writer; even when you know you have achieved nothing yourself and are still achieving nothing, this is not as terrible as it might otherwise be, because Tolstoy achieves for everyone. What he does serves to justify all the hopes and aspirations invested in literature." The 19th-century British poet and critic ] opined that "A novel by Tolstoy is not a work of art but a piece of life."<ref name="Britannica" /> ] said that "if the world could write by itself, it would write like Tolstoy."<ref name="Britannica" /> | |||

| Later novelists continued to appreciate Tolstoy's art, but sometimes also expressed criticism. ] wrote, "I am attracted by his earnestness and by his power of detail, but I am repelled by his looseness of construction and by his unreasonable and impracticable mysticism."<ref name="ACD">{{cite magazine|last1=Doyle|first1=Arthur Conan|title=My Favourite Novelist and His Best Book|date=January 1898|magazine=]|url=http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks13/1306981h.html|access-date=6 October 2017|archive-date=6 October 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171006212159/http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks13/1306981h.html|url-status=live}}</ref> ] declared him "the greatest of all novelists."<ref name="Britannica" /> ] noted that, "He is never dull, never stupid, never tired, never pedantic, never theatrical!" ] wrote of Tolstoy's seemingly guileless artistry: "Seldom did art work so much like nature." ] heaped superlatives upon '']'' and '']''; he questioned, however, the reputation of '']'' and sharply criticized '']'' and '']''. However, Nabokov called Tolstoy the "greatest Russian writer of prose fiction".<ref>{{Cite news |last=Frank |first=Joseph |date=1981-11-15 |title=Vladimir Nabokov Reads the Russian Masters |language=en-US |newspaper=Washington Post |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/entertainment/books/1981/11/15/vladimir-nabokov-reads-the-russian-masters/7f30bba2-b61f-40a4-892d-0ad82ee34e2e/ |access-date=2023-12-28 |issn=0190-8286 |archive-date=10 December 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221210223056/https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/entertainment/books/1981/11/15/vladimir-nabokov-reads-the-russian-masters/7f30bba2-b61f-40a4-892d-0ad82ee34e2e/ |url-status=live }}</ref> Critic ] called '']'' "my personal touchstone for the sublime in prose fiction, to me the best story in the world."<ref>{{Cite book |last=Bloom |first=Harold |title=] |publisher=] |year=1994 |location=New York}}</ref> When ] was asked to list what he thought were the three greatest novels, he replied: "''Anna Karenina, Anna Karenina'', and ''Anna Karenina''".<ref name=":5" /> Critic ] referred to ''War and Peace'' as the greatest of all novels.<ref name=":6" /> | |||

| ==Novels and fictional works== | |||

| ] | |||

| ==Ethical, political and religious beliefs== | |||

| Tolstoy's ] consistently attempts to convey realistically the Russian society in which he lived. ] commented that Tolstoy's work is not art, but a piece of life. Arnold's assessment was echoed by ] who said that, "if the world could write by itself, it would write like Tolstoy". | |||

| ],<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180628044119/http://www.tolstoy-studies-journal.com/tolstoy-in-color |date=28 June 2018 }}, ''Tolstoy Studies Journal,'' a publication of the Tolstoy Society of North America, n.d. Retrieved 27 June 2018.</ref> ] print by ]]] | |||

| ===Schopenhauer=== | |||

| His first publications were three ]s, ''Childhood'', ''Boyhood'', and ''Youth'' (1852 – 1856). They tell of a rich landowner's son and his slow realization of the differences between him and his ]s. Although in later life Tolstoy rejected these books as sentimental, a great deal of his own life is revealed, and the books still have relevance for their telling of the universal story of growing up. | |||

| After reading ]'s '']'', Tolstoy gradually became converted to the ascetic morality upheld in that work as the proper spiritual path for the upper classes. In 1869 he writes: "Do you know what this summer has meant for me? Constant raptures over Schopenhauer and a whole series of spiritual delights which I've never experienced before....no student has ever studied so much on his course, and learned so much, as I have this summer."<ref>Tolstoy's Letter to A.A. Fet, 30 August 1869</ref> | |||

| Tolstoy served as a ] in an artillery regiment during the ], recounted in his '']''. His experiences in battle helped develop his ], and gave him material for realistic depiction of the horrors of ] in his later work. | |||

| In Chapter VI of '']'', Tolstoy quoted the final paragraph of Schopenhauer's work. It explains how a complete ] causes only a relative nothingness which is not to be feared. Tolstoy was struck by the description of Christian, Buddhist, and Hindu ascetic renunciation as being the path to holiness. After reading passages such as the following, which abound in Schopenhauer's ethical chapters, the Russian nobleman chose poverty and formal denial of the will: <blockquote> But this very necessity of involuntary suffering (by poor people) for ] is also expressed by that utterance of the Savior (]): "It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle, than for a rich man to enter into the kingdom of God." Therefore, those who were greatly in earnest about their eternal salvation, chose ] when fate had denied this to them and they had been born in wealth. Thus Buddha ] was born a prince, but voluntarily took to the mendicant's staff; and ], the founder of the ] who, as a youngster at a ball, where the daughters of all the notabilities were sitting together, was asked: "Now Francis, will you not soon make your choice from these beauties?" and who replied: "I have made a far more beautiful choice!" "Whom?" "''La povertà'' (poverty)": whereupon he abandoned every thing shortly afterwards and wandered through the land as a mendicant.<ref>Schopenhauer, '']'', Vol. II, § 170</ref></blockquote> | |||

| '']'' (1863) is an unfinished novel which describes the Cossack life and people through a story of Dmitri Olenin, a Russian aristocrat in love with a Cossack girl. This text was acclaimed by ] as one of the finest in the language. The magic of Tolstoy's language is naturally lost in translation, but the following excerpt may give some idea as to the lush, sensuous, pulsing texture of the original: | |||

| ===Christianity=== | |||

| {{Quotation|Along the surface of the water floated black shadows, in which the experienced eyes of the Cossack detected trees carried down by the current. Only very rarely sheet-lightning, mirrored in the water as in a black glass, disclosed the sloping bank opposite. The rhythmic sounds of night — the rustling of the reeds, the snoring of the Cossacks, the hum of mosquitoes, and the rushing water, were every now and then broken by a shot fired in the distance, or by the gurgling of water when a piece of bank slipped down, the splash of a big fish, or the crashing of an animal breaking through the thick undergrowth in the wood. Once an owl flew past along the Terek, flapping one wing against the other rhythmically at every second beat.}} | |||

| In 1884, Tolstoy wrote a book called ''What I Believe'', in which he openly confessed his Christian beliefs. He affirmed his belief in Jesus Christ's teachings and was particularly influenced by the ], and the injunction to ], which he understood as a "commandment of non-resistance to evil by force" and a doctrine of ] and ]. In his work ''The Kingdom of God Is Within You'', he explains that he considered mistaken the Church's doctrine because they had made a "perversion" of Christ's teachings. Tolstoy also received letters from American ] who introduced him to the non-violence writings of Quaker Christians such as ], ], and ]. Later, various versions of "Tolstoy's Bible" were published, indicating the passages Tolstoy most relied on, specifically, the reported words of Jesus himself.<ref>Orwin, Donna T. ''The Cambridge Companion to Tolstoy''. Cambridge University Press, 2002</ref> | |||

| '']'' (1869) is generally thought to be one of the greatest ]s ever written, remarkable for its breadth and unity. Its vast canvas includes 580 characters, many historical, others fictional. The story moves from family life to the headquarters of ], from the court of ] to the battlefields of ] and ]. The novel explores Tolstoy's theory of history, and in particular the insignificance of individuals such as Napoleon and Alexander. But more importantly, Tolstoy's imagination created a world that seems to be so believable, so real, that it is not easy to realize that most of his characters actually never existed and that Tolstoy never witnessed the epoch described in the novel. | |||

| ] and other residents of ], South Africa, 1910]] | |||

| Somewhat surprisingly, Tolstoy did not consider ''War and Peace'' to be a novel (nor did he consider many of the great Russian fictions written at that time to be novels). It was to him an ] in prose. '']'' (1877), which Tolstoy regarded as his first true novel, was one of his most impeccably constructed and compositionally sophisticated works. It tells parallel stories of an adulterous woman trapped by the conventions and falsities of society and of a philosophical landowner (much like Tolstoy) who works alongside the peasants in the fields and seeks to reform their lives. His last novel was '']'', published in 1899, which told the story of a nobleman seeking redemption for a sin committed years earlier and incorporated many of Tolstoy's refashioned views on life. An additional short novel, ''Hadji Murat'', was published posthumously in 1912. | |||

| Tolstoy believed that a true Christian could find lasting happiness by striving for inner perfection through following the ] of loving one's neighbor and God, rather than guidance from the Church or state. Another distinct attribute of his philosophy based on Christ's teachings is ] during conflict. This idea in Tolstoy's book '']'' directly influenced ] and therefore also nonviolent resistance movements to this day. | |||

| Tolstoy's later work is often criticized as being overly didactic and patchily written, but derives a passion and verve from the depth of his austere moral views. The sequence of the temptation of Sergius in ''Father Sergius'', for example, is among his later triumphs. ] relates how Tolstoy once read this passage before himself and Chekhov and that Tolstoy was moved to tears by the end of the reading. Other later passages of rare power include the crises of self faced by the protagonists of '']'' and ''Master and Man'', where the main character (in ''After the Ball'') or the reader (in ''Master and Man'') is made aware of the foolishness of the protagonists' lives. ''The Death of Ivan Ilyich'' is perhaps the greatest fictional meditation on death ever written. | |||

| Tolstoy believed that the aristocracy was a burden on the poor.<ref>{{Cite book|url = https://books.google.com/books?id=ie2vCwAAQBAJ&pg=PA102|title = Russian Writers and Society in the Second Half of the Nineteenth Century|isbn = 978-1349044184|last1 = Andrew|first1 = Joe|date = 18 June 1982|publisher = Springer|access-date = 23 January 2022|archive-date = 22 March 2024|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20240322205412/https://books.google.com/books?id=ie2vCwAAQBAJ&pg=PA102#v=onepage&q&f=false|url-status = live}}</ref> He opposed ] land ownership and the institution of marriage, and valued chastity and sexual abstinence (discussed in '']'' and his preface to ''The Kreutzer Sonata''), ideals also held by the young Gandhi. Tolstoy's passion from the depth of his austere moral views is reflected in his later work.<ref>{{cite web |author-last=Sommers |author-first=Aaron |url=http://coastlinejournal.com/2009/09/08/why-leo-tolstoy-wouldn%E2%80%99t-super-size-it/ |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171123060912/http://coastlinejournal.com/2009/09/08/why-leo-tolstoy-wouldn%E2%80%99t-super-size-it/ |url-status=dead |archive-date=23 November 2017 |title=Why Leo Tolstoy Wouldn't Supersize It |publisher=Coastlinejournal.com |date=8 September 2009 |access-date=16 May 2010}}</ref> One example is the sequence of the temptation of Sergius in ''Father Sergius''. ] relates how Tolstoy once read this passage before him and Chekhov, and Tolstoy was moved to tears by the end of the reading. Later passages of rare power include the personal crises faced by the protagonists of ''The Death of Ivan Ilyich'', and of '']'', where the main character in the former and the reader in the latter are made aware of the foolishness of the protagonists' lives. | |||

| Tolstoy had an abiding interest in children and children's literature and wrote tales and fables. Some of his fables are free adaptations of fables from ] and from ] tradition. | |||

| In 1886, Tolstoy wrote to the Russian ] and anthropologist ], who was one of the first anthropologists to refute ], the view that the different ] belonged to different species: "You were the first to demonstrate beyond question by your experience that man is man everywhere, that is, a kind, sociable being with whom communication can and should be established through kindness and truth, not guns and spirits."<ref>{{cite news |title=Nicholas Maclay: Russian Polymath |url=https://www.harbourtrust.gov.au/en/our-story/harbour-history/digitales/nicholas-maclay/ |work=Harbourtrust.gov.au |date=29 September 2020 |access-date=10 August 2022 |archive-date=28 June 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220628025609/https://www.harbourtrust.gov.au/en/our-story/harbour-history/digitales/nicholas-maclay/ |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| === Reputation === | |||

| Tolstoy's contemporaries paid him lofty tributes: ] thought him the greatest of all living writers and ], on reading ''War and Peace'' for the first time in translation, compared him to ] and gushed: "What an artist and what a psychologist!". ] called Tolstoy a "great writer of the Russian land"<ref name=HandbookRussianLiterature>Victor Terras ed., ''Handbook of Russian Literature'', p. 476-480, Yale University Press, 1985 (retrieved on 14 December 2006 from )</ref> and implored him not to abandon literature on his deathbed. ], who often visited Tolstoy at his country estate, wrote: "When literature possesses a Tolstoy, it is easy and pleasant to be a writer; even when you know you have achieved nothing yourself and are still achieving nothing, this is not as terrible as it might otherwise be, because Tolstoy achieves for everyone. What he does serves to justify all the hopes and aspirations invested in literature." | |||

| ===Christian anarchism=== | |||

| Later critics and novelists continue to bear testaments to his art: ] went on to declare him "greatest of all novelists", and ], defending him from criticism, noted: "He is never dull, never stupid, never tired, never pedantic, never theatrical". ] wrote of his seemingly guileless artistry — "Seldom did art work so much like nature" — sentiments shared in part by many others, including ] and ]. ], himself a Russian and an infamously harsh critic, placed him above all other Russian fiction writers, even ], and equalled him with ] among Russian writers. | |||

| Tolstoy had a profound influence on the development of ] thought.<ref>{{cite book |url=https://archive.org/details/TheContemporaryRelevanceOfLeoTolstoy |title=The Contemporary Relevance of Leo Tolstoy's Late Political Thought |author-last=Christoyannopoulos |author-first=Alexandre |author-link=Alexandre Christoyannopoulos |year=2009 |quote=Tolstoy articulated his Christian anarchist political thought between 1880 and 1910, yet its continuing relevance should have become fairly self-evident already. |publisher=International Political Science Association }}</ref> Tolstoy believed being a Christian required him to be a pacifist; the apparently inevitable waging of war by governments is why he is considered a philosophical anarchist. The ]s were a small Christian anarchist group formed by Tolstoy's companion, ] (1854–1936), to spread Tolstoy's religious teachings. From 1892, he regularly met with the student-activist ] who would defend several Tolstoyans; they discussed the fate of the ]. Philosopher ] wrote of Tolstoy in the article on anarchism in the '']'': | |||

| ==Religious and political beliefs== | |||

| <blockquote>Without naming himself an anarchist, Leo Tolstoy, like his predecessors in the popular religious movements of the 15th and 16th centuries, ], ] and many others, took the anarchist position as regards the ] and ]s, deducing his conclusions from the general spirit of the teachings of Jesus and from the necessary dictates of reason. With all the might of his talent, Tolstoy made (especially in ''The Kingdom of God Is Within You'') a powerful criticism of the church, the state and law altogether, and especially of the present ]s. He describes the state as the domination of the wicked ones, supported by brutal force. Robbers, he says, are far less dangerous than a well-organized government. He makes a searching criticism of the prejudices which are current now concerning the benefits conferred upon men by the church, the state, and the existing distribution of property, and from the teachings of Jesus he deduces the rule of non-resistance and the absolute condemnation of all wars. His religious arguments are, however, so well combined with arguments borrowed from a dispassionate observation of the present evils, that the anarchist portions of his works appeal to the religious and the non-religious reader alike.<ref>{{Cite EB1911|wstitle=Anarchism |volume=1 |author-last=Kropotkin |author-first=Peter Alexeivitch |author-link=Peter Kropotkin |pages=914–919; see page 918 }}</ref></blockquote> | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ] in Samara, 1891]] | |||

| At approximately the age of 50, Tolstoy experienced a spiritual crisis, at which point he was so agonized about discovering life's meaning as to seriously contemplate ending his life. He relates the story of this spiritual crisis in '']'', and the conclusions of his studies in '']'', '']'' and '']''. | |||

| ] of Tolstoy's 80th birthday (1908) at Yasnaya Polyana, showing his wife Sofya (picking flowers in the garden) daughter Aleksandra (sitting in the carriage in the white blouse); his aide and confidante V. Chertkov (bald man with the beard and mustache); and students.]] | |||

| After reading ]'s '']'', Tolstoy gradually became converted to the ] that was praised in that book. | |||

| {{Quotation|Do you know what this summer has meant for me? Constant raptures over Schopenhauer and a whole series of spiritual delights which I've never experienced before. ... no student has ever studied so much on his course, and learned so much, as I have this summer.|Tolstoy's Letter to A.A. Fet, August 30, 1869}} | |||

| In Chapter VI of ''A Confession'', Tolstoy quoted the final paragraph of Schopenhauer's work. In this paragraph, the German philosopher explained how the nothingness that results from complete denial of self is only a relative nothingness and not to be feared. Tolstoy was struck by the description of ], ], and ] ascetic renunciation as being the path to holiness. After reading passages such as the following, which abound in Schopenhauer's ethical chapters, Tolstoy, the Russian nobleman, chose poverty and denial of the will. | |||

| In hundreds of essays over the last 20 years of his life, Tolstoy reiterated the anarchist critique of the state and recommended books by ] and ] to his readers, while rejecting anarchism's espousal of ]. In the 1900 essay, "On Anarchy," he wrote: "The Anarchists are right in everything; in the negation of the existing order, and in the assertion that, without Authority, there could not be worse violence than that of Authority under existing conditions. They are mistaken only in thinking that Anarchy can be instituted by a revolution. But it will be instituted only by there being more and more people who do not require the protection of governmental power ... There can be only one permanent revolution{{snd}}a moral one: the regeneration of the inner man." Despite his misgivings about ], Tolstoy took risks to circulate the prohibited publications of ], and corrected the proofs of Kropotkin's "Words of a Rebel", illegally published in St Petersburg in 1906.<ref>{{cite book|title=] |author-first1=G. |author-last1=Woodcock |author-first2=I. |author-last2=Avakumović |date=1990}}</ref> | |||

| {{Quotation|But this very necessity of involuntary suffering (by poor people) for eternal salvation is also expressed by that utterance of the Savior (]): "It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle, than for a rich man to enter into the kingdom of God." Therefore those who were greatly in earnest about their eternal salvation, chose voluntary poverty when fate had denied this to them and they had been born in wealth. Thus ] ] was born a prince, but voluntarily took to the mendicant's staff; and ], the founder of the mendicant orders who, as a youngster at a ball, where the daughters of all the notabilities were sitting together, was asked: "Now Francis, will you not soon make your choice from these beauties?" and who replied: "I have made a far more beautiful choice!" "Whom?" "''La poverta'' (poverty)": whereupon he abandoned every thing shortly afterwards and wandered through the land as a mendicant.|Schopenhauer, '']'', Vol. II, §170}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ===Pacificism=== | |||

| The teaching of mature Tolstoy is a rationalized "]", stripped of all tradition and all positive mysticism. He rejected personal ] and concentrated exclusively on the moral teaching of the Gospels. Tolstoy's Christian beliefs were based on the ], and particularly on the phrase "]", which he saw as a justification for pacifism, ] and ]. Of the moral teaching of ], the words "Resist not evil" were taken to be the principle out of which all the rest follows. He condemned the State, which sanctioned violence and corruption, and rejected the authority of the Church, which sanctioned the State. His condemnation of every form of compulsion authorizes many to classify Tolstoy's later teachings, in its political aspect, as ]. | |||

| In 1908, Tolstoy wrote '']'',<ref>{{citation|author-last=Parel |author-first=Anthony J. |author-link=Anthony Parel |contribution=Gandhi and Tolstoy |editor-first1=M. P. |editor-last1=Mathai |editor-first2=M.S. |editor-last2=John |editor-first3=Siby K. |editor-last3=Joseph |title=Meditations on Gandhi: a Ravindra Varma festschrift |pages=96–112 |publisher=Concept |place=New Delhi |year=2002 |contribution-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=kcpDOVk5Gp8C&pg=PA96}}</ref> outlining his belief in non-violence as a means for India to gain ] from ]. In 1909, Gandhi read a copy of the letter when he was becoming an activist in South Africa. He wrote to Tolstoy seeking proof that he was the author, which led to further correspondence.<ref name="PearlsOfInsp_Rajaram" /> Tolstoy's ''The Kingdom of God Is Within You'' also helped to convince Gandhi of ], a debt Gandhi acknowledged in his autobiography, calling Tolstoy "the greatest apostle of non-violence that the present age has produced". Their correspondence lasted only a year, from October 1909 until Tolstoy's death in November 1910, but led Gandhi to give the name Tolstoy Colony to his second ] in South Africa.<ref>{{cite book|title=Tolstoy and Gandhi, men of peace: a biography |author-first=M.B. |author-last=Green |date=1983 |publisher=Basic Books}}</ref> Both men also believed in the merits of ], the subject of several of Tolstoy's essays.<ref>{{cite web |author-last=Tolstoy |author-first=Leo |title=The First Step |year=1892 |access-date=21 May 2016 |url=http://www.ivu.org/history/tolstoy/the_%20first_step.html |quote=... if be really and seriously seeking to live a good life, the first thing from which he will abstain will always be the use of animal food, because ... its use is simply immoral, as it involves the performance of an act which is contrary to the moral feeling – killing |archive-date=28 August 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190828031414/https://ivu.org/history/tolstoy/the_%20first_step.html |url-status=live }}. Preface to the Russian translation of ] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101124121214/http://ivu.org/history/williams/index.html |date=24 November 2010 }}</ref> | |||

| === Christian anarchism === | |||

| ] | |||

| Although he did not call himself an ] because he applied the term to those who wanted to change society through violence,<ref>Woodcock, George. Anarchism: A History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements, Broadview Press, 2004, p. 185</ref> Tolstoy is commonly regarded as an anarchist. His doctrine of nonresistance (nonviolence) when faced by conflict is another distinct attribute of his philosophy based on Christ's teachings. By directly influencing ] with this idea through his work ''The Kingdom of God is Within You'', Tolstoy has had a huge influence on the nonviolent resistance movement to this day. He opposed private property and the institution of marriage and valued the ideals of ] and ] (as discussed in ''Father Sergius'' and his preface to '']''), ideals also held by the young Gandhi. | |||

| The ] stirred Tolstoy's interest in Chinese philosophy.<ref name="Bodde1967">{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=STFaAAAAYAAJ&q=Boxer |title=Tolstoy and China |author-first=Derk |author-last=Bodde |publisher=Johnson Reprint Corporation |year=1967 |pages=25, 44, 107 |isbn=9780384048959 |access-date=23 October 2020 |archive-date=22 March 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240322205558/https://books.google.com/books?id=STFaAAAAYAAJ&q=Boxer |url-status=live }}</ref> He was a famous ], and read the works of ]<ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3YPAaFfUp9oC&q=lev+tolstoy+sinophile&pg=PA314 |title=The Bear Watches the Dragon |author-last1=Lukin |author-first1=Alexander |year=2003 |publisher=M.E. Sharpe |isbn=978-0-7656-1026-3 |access-date=23 October 2020 |archive-date=22 March 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240322205605/https://books.google.com/books?id=3YPAaFfUp9oC&q=lev+tolstoy+sinophile&pg=PA314#v=snippet&q=lev%20tolstoy%20sinophile&f=false |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=nU2lErM3VgwC&q=tolstoy+boxer+rebellion&pg=PA37 |title=The Cambridge companion to Tolstoy |author-first=Donna |author-last=Tussing Orwin |publisher=Cambridge University Press |year=2002 |isbn=978-0-521-52000-3 |page=37 |access-date=23 October 2020 |archive-date=22 March 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240322205414/https://books.google.com/books?id=nU2lErM3VgwC&q=tolstoy+boxer+rebellion&pg=PA37 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=UipgAAAAMAAJ&q=tolstoy+boxer+rebellion+confucianism |title=Tolstoy and China |author-first=Derk |author-last=Bodde |publisher=Princeton University Press |year=1950 |page=25 |access-date=23 October 2020 |archive-date=22 March 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240322205415/https://books.google.com/books?id=UipgAAAAMAAJ&q=tolstoy+boxer+rebellion+confucianism |url-status=live }} (Original from the University of Michigan)</ref> and Lao Zi. Tolstoy wrote ''Chinese Wisdom'' and other texts about China. Tolstoy corresponded with the Chinese intellectual ] and recommended that China remain an agrarian nation, and not reform like Japan. Tolstoy and Gu opposed the ] by ] and believed that the reform movement was perilous.<ref name="Lee2005">{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=1jlOQc8BumIC&q=Tolstoy+boxers&pg=PA10 |title=Pioneers of Modern China: Understanding the Inscrutable Chinese |author-first=Khoon Choy |author-last=Lee |publisher=World Scientific |year=2005 |isbn=978-981-256-618-8 |pages=10– |access-date=23 October 2020 |archive-date=22 March 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240322205458/https://books.google.com/books?id=1jlOQc8BumIC&q=Tolstoy+boxers&pg=PA10#v=snippet&q=Tolstoy%20boxers&f=false |url-status=live }}</ref> Tolstoy's ideology of non-violence shaped the thought of the Chinese anarchist group Society for the Study of Socialism.<ref name="Campbell2009">{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=gWHrWq2Kd-UC&q=Tolstoy+boxers&pg=PA194 |title=The Britannica Guide to Political and Social Movements That Changed the Modern World |author-first=Heather M. |author-last=Campbell |publisher=The Rosen Publishing Group |year=2009 |isbn=978-1-61530-016-7 |pages=194– |access-date=23 October 2020 |archive-date=22 March 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240322205416/https://books.google.com/books?id=gWHrWq2Kd-UC&q=Tolstoy+boxers&pg=PA194#v=snippet&q=Tolstoy%20boxers&f=false |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||