| Revision as of 20:57, 27 September 2007 editLokyz (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers15,449 edits pleeeeas, pleaase do not invent facts that are not present even in Patriotic tygodniks← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 05:15, 12 November 2024 edit undoSzturnek (talk | contribs)451 edits added Category:Uprisings of Poland using HotCat | ||

| (368 intermediate revisions by 84 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Polish uprising against the Lithuanian authorities in August 1919}} | |||

| '''Sejny Uprising''' ({{lang-pl|Powstanie sejneńskie}}) refers to a 1919 ] by the ] population in the area of the town of ] against ]n authorities. It was the second ] (after the ]) to end in a complete success for the Polish side.<ref name="kaluski"/> | |||

| {{good article}} | |||

| {{Infobox military conflict | |||

| | conflict = Sejny Uprising | |||

| | image = Sejny 1919 rudnicki.JPG | |||

| | image_size = 250px | |||

| | caption = Lt. Adam Rudnicki, leader of the Sejny Uprising, and his colleagues. August 1919. | |||

| | place = ] | |||

| | date = August 23 – September 7, 1919 | |||

| | result = Polish victory | |||

| | territory = Lithuanians retreated behind the ]; Poland secured Sejny | |||

| | combatant1 = {{flagicon|Second Polish Republic|1919}} ] (PMO) <br> {{flagicon|Second Polish Republic|1919}} 41st Infantry Regiment | |||

| | combatant2 = {{flagicon|Lithuania|1918}} ]n Sejny Command <br> {{flagicon|Lithuania|1918}} 1st Reserve Battalion | |||

| | commander1 = {{flagicon|Second Polish Republic|1919}} Adam Rudnicki <br> {{flagicon|Second Polish Republic|1919}} ]<br> {{flagicon|Second Polish Republic|1919}} ]{{KIA}} | |||

| | commander2 = {{flagicon|Lithuania|1918}} ] | |||

| | strength1 = 900<ref name=BuchSt/>–1,200<ref name=Manc/> PMO volunteers <br> 800 regular troops{{sfn|Lesčius|2004|p=276}} | |||

| | strength2 = 900 regular troops{{sfn|Lesčius|2004|p=276}}<!-- on Sept 1, including reserve --> <br> 300 volunteers{{sfn|Lesčius|2004|p=275}} | |||

| | casualties1 = 37 killed in action <br> 70 wounded | |||

| | casualties2 = | |||

| | campaignbox = {{Campaignbox Polish–Lithuanian War}} | |||

| | partof = ] | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Campaignbox Establishment of Second Polish Republic}} | |||

| The '''Sejny Uprising''' or '''Seinai Revolt''' ({{langx|pl|Powstanie sejneńskie}}, {{langx|lt|Seinų sukilimas}}) refers to a Polish uprising against the ]n authorities in August 1919 in the ethnically mixed area surrounding the town of ] ({{langx|lt|Seinai}}). When German forces, which occupied the territory during ], retreated from the area in May 1919, they turned over administration to the Lithuanians. Trying to prevent an armed conflict between Poland and Lithuania, the ] drew a demarcation line, known as the ]. The line assigned much of the disputed ] to Poland and required the ] to retreat. While the Lithuanians retreated from some areas, they refused to leave Sejny (Seinai), because of its major Lithuanian population.{{sfn|Senn|1975|p=158}} Polish irregular forces began the uprising on August 23, 1919, and soon received support from the regular ]. After several military skirmishes, Polish forces secured Sejny and the Lithuanians retreated behind the Foch Line. | |||

| The uprising did not solve the larger border conflict between Poland and Lithuania over the ethnically mixed ]. Both sides complained about each other's repressive measures.<ref name=BuchKr/> The conflict intensified in 1920, causing military skirmishes of the ]. Sejny changed hands frequently until the ] of October 1920, which left Sejny on the Polish side. The uprising undermined the plans of Polish leader ] who was ] to replace the Lithuanian government with a pro-Polish cabinet which would agree to a union with Poland (the proposed ] federation). Because the Sejny Uprising had prompted the Lithuanian intelligence to intensify its investigations of Polish activities in Lithuania, they discovered plans for the coup and prevented it, arresting Polish sympathizers.<!--Manczuk, Łossowski and Pisarska all support this claim--> These hostilities in Sejny further strained the ]. | |||

| == Background == | |||

| Eventually, Poland and Lithuania reached an agreement on a new border that left Sejny on the Polish side of the border. The Polish–Lithuanian border in the Suwałki Region has remained the same since then (with the exception of the ] period). | |||

| The lands around the town of ] formed a Polish-German-Lithuanian borderland since the ], and the borders in the area moved back and forth numerous times in the past. During the times of the ] the town of ] itself, along with the rest of the ], was part of the ] rather than the ]. However, the owners of the town were the Dominican friars from ]. In addition, the proximity of the borders as well as the trade routes through the forests of the area allowed the multi-cultural pattern of the town to be preserved until 20th century, with the majority of the population formed by Poles, Lithuanians, Jews and Tatars. In 19th century the town had been part of Russian-controlled ].<ref name="kaluski"/> | |||

| ==Background== | |||

| During the ] the region was captured by ], which intended to incorporate the area into its province of ].<ref name="buchowski">{{pl icon}} {{cite web | author= Stanisław Buchowski | title=Powstanie Sejneńskie 23-28 sierpnia 1919 roku (Sejny uprising of August 23-28, 1919) | publisher=Gimnazjum Nr. 1 w Sejnach | year= | work=www.g1.powiat.sejny.pl | url=http://www.g1.powiat.sejny.pl/buchowski.htm | accessdate=2007-09-27 }}</ref> However, the German defeat in the war made those plans obsolete as it was clear that the victorious ] powers would be willing to assign the territory to the newly-recreated states of Poland or Lithuania, rather than to defeated Germany.<ref name="buchowski"/>. | |||

| During the ages, the lands surrounding the town of ] were part of the ] until 1795. Sejny itself was property of ]' ] friars from 1603 until 1805. During the ] in 1795, the region became part of the ] as ] until 1807, from then until 1815, it was part of the ] which ] had created. For a century after the conclusion of the ], the town was in ], a part of the ].<ref name="Wsp" /><ref name="Sejnhist" /> | |||

| During ], the region was captured by the ], which intended to incorporate the area into its province of ].<ref name=BuchSt/> After the German defeat, the victorious ] was willing to assign the territory to either the newly independent Poland or Lithuania.<ref name=BuchSt/> The future of the region was discussed at the ] in January 1919.<ref name=Pisa/> The Germans, whose former ] administration was preparing to evacuate, initially supported leaving the area to a Polish administration.<ref name=Manc/> However, as Poland was becoming an ally of ], German support gradually shifted towards Lithuania.<ref name=Manc/> In July 1919, when the German troops began their slow retreat from the area, they delegated the administration to local Lithuanian authorities.{{sfn|Lesčius|2004|p=271}} Lithuanian officers and troops, who first arrived in the region in May,<ref name=Maka/> began to organize military units in the pre-war ].{{sfn|Lesčius|2004|p=271}} | |||

| This led to a conflict between Poland and Lithuania, as both sides claimed the area. The Germans, whose ] administration of the former ] was preparing to evacuate the area, initially supported the creation of Polish administration in the area<ref name="manczuk">{{pl icon}} {{cite journal | author =] | year =2001 | month = | title =Z Orłem przeciw Pogoni. Powstanie sejneńskie 1919 | journal =] | volume = | issue = | pages = | id = | url =http://mowiawieki.pl/artykul.html?id_artykul=860 | format = | accessdate =2007-09-27 }}</ref>. However, as reborn Poland was becoming an ally of ], with time their support started to gradually shift towards ]<ref name="manczuk"/>. On ], ], the Germans passed over the administration of the town to locally elected Lithuanian authorities, and Lithuanian partisans troops were formed by Lithunian activists in the pre-war ].<ref name=KA>{{cite book | author = Editors: dr. Gintautas Surgailis; habil. dr. prof. Algirdas Ažubalis; habil. dr. prof. Grzegosz Blaszyk; dr. doc. Pranas Jankauskas; dr. Eriks Jekabsons; habil. dr. prof. Waldemar Rezmer and others | title = Karo archyvas XVIII | publisher = Generolo Jono Žemaičio Lietuvos karo akademija | date = 2003 | location = Vilnius | pages = pp.188-189 | url = | doi = | id = |id = ISSN 1392-6489 }}</ref> However, the diplomatic conflict over the future of the area was far from finished, as the main battleground were the halls of the ].{{Fact}} | |||

| According to Russian statistics from 1889, there were 57.8% Lithuanians, 19.1% Poles, and 3.5% Belarusians in the ].<ref name=Senav/> It is generally agreed that Lithuanians formed the majority of the population in the northern Suwałki Governorate, while Poles were concentrated in the south. But Lithuanian and Polish historians and political scientists continued to disagree over the location of the line that separated the areas of Lithuanian and Polish majorities. Lithuanians claimed that Sejny and the surrounding area were inhabited primarily by the Lithuanians,<ref name=Maka/> while the Poles claimed exactly the opposite.{{sfn|Łossowski|1995|p=51}} The German census of 1916 showed that 51% of Sejny population was Lithuanian.{{sfn|Senn|1975|p=133}} | |||

| ] | |||

| As the Polish-Lithuanian talks in Paris brought little effect, on ], 1919, ] ] presented both delegations with the project of the so-called '']''. The ] run from the German border, south of ] (with ] on the Polish side), north of ] and then south of Lubowo. From there the line turned along the shores of ], east of ] and along the ] and ] rivers to ]<ref name="kaluski">{{pl icon}} {{cite journal | author =Marian Kałuski | year =2004 | month =August | title =85 rocznica przyłączenia Suwalszczyzny do Polski | journal =Wirtualna Polonia | volume = | issue =2004-08-31 | pages = | id = | url =http://www.wirtualnapolonia.com/teksty.asp?tekstID=7719 | format = | accessdate =2007-09-27 }}</ref>. This left the southern part of the conflict area, with both ] and Sejny in Polish hands, roughly reflecting the region's demographics.<ref name="manczuk"/> At the same time the northern part of the area with the towns of Kalwaria/] and Mariampol/], in the past a part of ], was awarded to Lithuanian in its entirety.{{fact}} | |||

| ==Demarcation lines== | |||

| On July 26 the Foch Line was accepted by the Highest Council of the ] as the provisional border between two states.<ref name="manczuk"/> Under pressure from the ], which would later become the ], Poland initially backed down on the issue. However, the fact that the Lithuanian military forces were allowed to enter the area even before the German army withdrew led many local Poles to believe, that the intention of Lithuanians was to capture ], and convince the Entente to accept such '']''<ref name="buchowski"/>. | |||

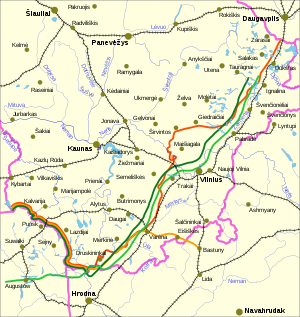

| ], was drawn on July 27.]] | |||

| In the ], the ] drew the first ] between Poland and Lithuania on June 18, 1919. The line satisfied no one, and Polish troops continued to advance deeper into the Lithuanian-controlled territory.{{sfn|Lesčius|2004|p=254}} These attacks coincided with the signing of the ] on June 28, which eliminated any danger from Germany.<ref name=Pisa/> Attempting to halt further hostilities, ] ] proposed a new line, known as the ], on July 18, 1919.{{sfn|Senn|1975|p=132}} | |||

| On August 12, a Polish manifestation in Sejny attracted over 100 delegates from neighboring Polish communities, which passed a resolution that "only securing the area by Polish Army can solve the problem."<ref name="buchowski"/><ref name="manczuk"/> On 17 August, a Lithuanian copunter-demonstration was staged, whose participants in turn brandished a slogan: "Citizens! Our nation is in danger! To arms! We shall leave not a single occupant on our lands!"<ref name="buchowski"/> Governments of both countries were encouraging the conflict. ] ] visited Sejny and in his speech called Lithuanians to defend their lands "to the end, however they can, with axes, pitchforks and scythes".<ref name="buchowski"/> In turn, Polish government - particularly Polish Chief of State, ] - were supporting ] (]) which was working on a ] which would topplenot eager to cooperate with Poland government of Lithuania under Sleževičius and replace it with a more pro-Polish government, which would consider allying itself with Poland under Piłsudski's ] ] scheme.<ref name="manczuk"/> The coup was to be accompanied by a series of uprisings in the whole Lithuania scheduled on August 1919.<ref name=LKA1/> The Sejny branch of ] led by Adam Rudnicki and Wacław Zawadzki was preparing for the uprising since August 16.<ref name="buchowski"/> | |||

| The Foch Line was negotiated with the Polish war mission, led by General ] in Paris, while Lithuanian representatives were not invited.<ref name=Maka/> The Foch Line had two major modifications compared to the June 18 line: first, the entire line was moved west to give extra protection to the strategic ] and second, the ], including the towns of Sejny, ], ], was assigned to Poland.{{sfn|Lesčius|2004|pp=254, 257}} Despite assurances at the time that the line was just a temporary measure to normalize the situation before full negotiations could take place, the southern Foch Line is the present-day ].<ref name=Maka/>{{sfn|Senn|1975|p=135}} | |||

| == The uprising == | |||

| The uprising of Poles led by local PMO activists in Sejny begun on ], ]. The date was chosen, because that day German troops have been withdrawn from the territory. After several days of fighting, the insurgents, aided by the Polish army, forced the outnumbered Lithuanians back. Lithuanians aided by Lithuanian army retook the city on ], liberated their ] and took back part of the documents and property, but were forced to retreat the same day. | |||

| On July 26, the Foch Line was accepted by the ] as the provisional border between the two states.<ref name=Manc/> Lithuanians were not informed about this decision until August 3.{{sfn|Senn|1975|p=134}} Neither country was satisfied: both Lithuanian and Polish forces would have to retreat from the Suwałki and Vilnius regions, respectively.{{sfn|Łossowski|1995|p=51}} Those Germans still present in the region also objected to the boundary of the line.<ref name=Loss/> The Lithuanian forces (about 350 strong){{sfn|Lesčius|2004|p=272}} left the town of Suwałki by August 7, but stopped in Sejny and formed a line at the ] river – ], thus effectively violating the demarcation line.<ref name=BuchSt/> Lithuanians believed that the Foch Line was not the final decision, and that they had the duty to protect Lithuanian outposts in the region.<ref name=Maka/> | |||

| The uprising ended with a Polish success and the town became a part of Poland. Polish casualties numbered about 37; the number of Lithuanian casualties remains unknown.<ref name="buchowski"/> Detachment of PMO from ] had orders to capture Lithuanian territory up to the ] city, but it could not be fulfilled due Lithuanian resistance.<ref name='Paransevicius'> {{cite web|url=http://www.punsk.com.pl/saltinis/saltinis1_2007/5.htm" |title=Seinai – 1918-1920 metai |accessdate=2007-09-27 |last=Paransevičius |first=Juozas Sigitas |language=Lithuanian }}</ref> | |||

| ==Uprising preparations== | |||

| == Aftermath == | |||

| On August 12, 1919, two days after the Germans retreated from Sejny,{{sfn|Lesčius|2004|p=273}} a Polish meeting in the town attracted over 100 delegates from neighboring Polish communities; the meeting passed a resolution that "only securing the area by Polish Army can solve the problem."<ref name=BuchSt/><ref name=Manc/> The Sejny branch of the ] (PMO), led by Polish regular army officers Adam Rudnicki and Wacław Zawadzki, began preparing for the uprising on August 16.<ref name=BuchSt/> PMO members and local militia volunteers numbered some 900<ref name=BuchSt/> or 1,200 men (sources vary).<ref name=Manc/> The uprising was scheduled for the night of August 22 to 23, 1919.<ref name=Manc/> The date was chosen to coincide with the withdrawal of German troops from the town of Suwałki.<ref name=BuchSt/> The Poles hoped to capture the territory up to the Foch Line and advance further to take control of the towns of ], ], ] as far as ].<ref name=Manc/>{{sfn|Lesčius|2004|p=274}} | |||

| After Poles acquired town and it surroundings repressions towards Lithuanian population started and the Lithuanian population of the region was subject to various repressions, including ] ban in public, Lithuanian organizations(with 1300 members), schools (with approx. 300 pupils) and press closure, confiscation of property and even burning of Lithuanian books.<ref name=LKA>{{cite book | last = Lesčius | first = Vytautas | authorlink = | coauthors = | title = Lietuvos kariuomenė nepriklausomybės kovose 1918-1920 | publisher = ], ] | date = 2004 | location = Vilnius | pages = p.278 | quote= Represijos palietė daug asmenų –mokytojus, visuomenės veikėjus, mokinius. Net ir Seinių diecezijos vysk. A.Karosui buvo paskirtas namų areštas, o vėliau jis buvo priverstas pasitraukti į nepriklausomą Lietuvą. 1919 rugsėjo 2d. lenkų kariuomenės dalys ir policija apsupo Seinių kunigų seminariją, dauguma Lietuvių profesorių bei dėstytojų buvo įkalinti, kai kurie išvaryti į Lietuvą. Lenkai niokojo lietuviškas įstaigas, uždarinėjo lietuviškas organizacijas ir mokyklas, kaip antai „Žiburio“ draugija (500 narių), „Pavasario“ kuopą (215), Blaivybės draugiją (300), šv. Zitos draugiją (93), dailės draugija „Lyrą“ (30), Lietuvių katalikių moterų sąjungą (20), „Artojo“ kooperatyvą (120) – iš viso 9 draugijas, apimančias 1300 narių. Jie taip pat uždarė lietuvių berniukų ir mergaičių gimnazijas (223 mokiniai), pradžios mokyklą (75 vaikai), visas laikraščių redakcijas, spaustuvę, skaityklą, iš lietuvių vaikų prieglaudos atėmė turtą ir perdavė lenkiškai prieglaudai, uždraudė lietuviškai kalbėti gatvėse. 1919 rugsėjo mėn. sudegino lietuvių mokyklų ir bendrabučių knygynėlių knygas. Teroro banga palietė visas Seinių apskrities vietoves. ('''Translation''': ''Repressions affected various persons – teachers, public persons, pupils. Seiniai diocese bishop A. Karosas was implemented house arrest, later he was forced to go into exile to independent Lithuania. In 1919-09-02 Polish army units and police surrounded Seiniai priest seminary, majority Lithuanian professors and academics were imprisoned, some expelled to Lithuania. Poles devastated Lithuanian institutions, closed organizations and schools, like "Žiburys" fellowship (with 500 members), "Pavasaris" cell (215), "Blaivybė" fellowship (300), St. Zita fellowship (93), art fellowship "Lyra" (30), Lithuanian women catholic union (20), "Artojas" cooperative (120) – overall 9 fellowships, whish had 1300 members. Poles also closed Lithuanian boys and girls gymnasiums (with 223 pupils), grammar-school (with 75 pupils), all newspapers offices, press, reading-room. Property of Lithuanian children shelter was confiscated and transferred to Polish one. It was prohibited to speak Lithuanian in public places also. In 1919 September Lithuanian books of school's and hostel bookshops' were burnt. Terror wave affected all Seiny surroundings.'' ) |url = | doi = | id = | isbn = 9955423234 }}</ref><ref name=KA/> | |||

| According to the Polish historian ], Piłsudski – who was ] in ] – discouraged the local PMO activists from carrying out the Sejny Uprising.<ref name=Manc/> Piłsudski reasoned that any hostilities could leave Lithuanians even more opposed to the proposed union with Poland (see ]). The local PMO disregarded his recommendations and launched the uprising. While locally successful, it led to the failure of the nationwide coup.<ref name=Manc/><ref name=Pisa/> | |||

| The POM plot to overthrow the Lithuanian government was unsuccessful; it was scheduled for 28 August 1919, and delayed to the September. It was uncovered by the counter-intelligence and stopped by Lithuanian Army officers. First arrests started August 27 and continued until end of September. During the searches full list of POM supporters was found, and the organisation was eliminated completely.<ref name=LKA1>{{cite book | last = Lesčius | first = Vytautas | authorlink = | coauthors = | title = Lietuvos kariuomenė nepriklausomybės kovose 1918-1920 | publisher = ], ] | date = 2004 | location = Vilnius | pages = p.259-278 |sbn = 9955423234 }}</ref>, it was the only successful PMO action in regions disputed by Lithuania and Poland. The PMO members in Lithuania stated, that Sejny uprising has damaged their reputation, and many former supporters turned their backs to PMO recruiters.<ref name=LKA1/> From the documents stolen in POW headquoters safe in ] and given to ] ] it is clear, that this plot was directed by ] himself.<ref name=LKA1/> Polish historian ] describes this uprising as a direct act of aggression from Polish government, that led to further hostilities between Poland and Lithuania. It was act that discouraged Lithuanians from federation with Poland.<ref name='Paransevicius'/> | |||

| On August 17, a Lithuanian counter-demonstration was staged. Its participants read aloud a recently issued recruiting proclamation of the Lithuanian volunteer army: "Citizens! Our nation is in danger! To arms! We shall leave not a single occupant on our lands!"<ref name=BuchSt/>{{sfn|Łossowski|1995|p=67}} On August 20, ] ] visited Sejny and called on Lithuanians to defend their lands "to the end, however they can, with axes, pitchforks and scythes".<ref name=BuchSt/>{{sfn|Łossowski|1995|p=67}} According to Lesčius, at the time the Lithuanian command in Sejny had only 260 infantry and 70 cavalry personnel, stretched along the long line of defense. There were only 10 Lithuanian guards and 20 clerical staff in the town itself.{{sfn|Lesčius|2004|p=273}} Mańczuk and Buchowski note that the Polish insurgents estimated the Lithuanian forces at 1,200 infantry (Mańczuk also adds an estimate of 120 cavalry), including a 400-strong garrison in Sejny.<ref name=BuchSt/><ref name=Manc/> | |||

| Only a year later, the town was captured by ] during the course of the ]. To ensure the right of passage through Lithuanian territory, on ], ] Russian authorities signed the ], which granted Lithuania the rights to the area. On ] the Lithuanians attacked the Polish defenders and recaptured the town. The Lithuanian authorities were once again established in the area. After the ] in 1920, the Bolshevik forces were defeated, and the ] again entered the area under Lithuanian control. Since the ] of 1919 had established the Polish-Lithuanian border on an ethnic basis, roughly correspondent to the '']'', the Lithuanian forces were forced to withdraw from the town, and on ], ] the town was again attached to Poland. However, the Lithuanian authorities continued to claim the area, and on ] a Lithuanian offensive initiated the ]. As the town was located only some 2 kilometres from the Lithuanian border, it was easily captured by Lithuanian forces. However, the assault was repelled with heavy losses on the Lithuanian side, and the Polish Army recaptured the town on ]. On September 10th, the last of the Lithuanian units retreated to the other side of the border, and on ] a ] agreement was signed, leaving Sejny on the Polish side of the border. | |||

| ==Military skirmishes== | |||

| ==Notes and references== | |||

| According to the Lithuanian historian Lesčius, the first Polish assault of about 300 PMO members on August 22 was repelled,{{sfn|Lesčius|2004|p=274}} but the next day Lithuanians were forced to retreat towards ]. Over 100 Lithuanians were imprisoned in Sejny when their commander Bardauskas sided with the Poles.{{sfn|Lesčius|2004|pp=274–275}} The Polish insurgents also attacked Lazdijai and Kapčiamiestis,<ref name=BuchSt/> towns on the Lithuanian side of the Foch Line. | |||

| <!--This article uses the Cite.php citation mechanism. If you would like more information on how to add references to this article, please see http://meta.wikimedia.org/Cite/Cite.php --> | |||

| <div class="references-small"> | |||

| ::'''In-line:''' | |||

| <references/> | |||

| </div> | |||

| In early morning of August 25, Lithuanians counterattacked and recaptured Sejny. Polish sources claim that Lithuanians there were aided by a company of Germans volunteers,<ref name=BuchSt/><ref name=Manc/><ref name=Wsp/><ref name=Sejnhist/> but Lithuanian sources assert that it was an excuse used by Rudnicki to explain his defeat.<ref name=Maka/> The Lithuanian forces recovered some important documents and property, freed Lithuanian prisoners{{sfn|Lesčius|2004|p=275}} and, according to Mańczuk, executed several of the PMO fighters they found wounded.<ref name=Manc/> | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| *{{pl icon}} | |||

| On the evening of August 25, the first regular unit (41st Infantry Regiment) of the Polish Army received an order to advance towards Sejny.<ref name=Manc/> The Lithuanian forces retreated on the same day when they learned about the approaching Polish reinforcements.{{sfn|Lesčius|2004|p=275}} According to Mańczuk, they based their retreat on an erroneous report about a "large Polish cavalry unit" operating to their rear; only small groups of Polish partisans operated there.<ref name=Manc/> Later the next day, during the afternoon of August 26, the PMO forces in Sejny were joined by the 41st Infantry Regiment.<ref name=Manc/> | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| On August 26, a large anti-Polish protest took place in ], with cries to march on Sejny.{{sfn|Lesčius|2004|p=275}} The last Lithuanian attempt to retake the town was made on August 28. The Lithuanians (about 650 men) were defeated by the combined forces of the Polish Army (800 men) and PMO volunteers (500 men).{{sfn|Lesčius|2004|p=275–276}} On August 27, the Poles officially demanded that Lithuanians retreat behind the Foch Line. On September 1, Rudnicki announced incorporation of PMO volunteers into the 41st Infantry Regiment.<ref name=Manc/> During the negotiations on September 5, representatives of the two groups agreed to settle on a detailed demarcation line; Lithuanians agreed to retreat by September 7.{{sfn|Lesčius|2004|p=277}} The Polish regular army units did not cross the Foch Line, and refused to aid the PMO insurgents still operating on the Lithuanian side.<ref name=Manc/> | |||

| ] | |||

| Polish sources give total Polish casualties for the Sejny Uprising as 37 killed in action and 70 wounded.<ref name=BuchSt/><ref name=Manc/> | |||

| ==Aftermath== | |||

| ] | |||

| After the uprising, Poland repressed Lithuanian cultural life in Sejny. Lithuanian schools in Sejny (which had some 300 pupils) and surrounding villages were closed.<ref name=Maka/> The local Lithuanian clergy were evicted, and the ] relocated.<ref name=BuchKr/> According to the Lithuanians, the repressions were even more far-reaching, including a ban on public use of the ] and the closing of Lithuanian organizations, which had a total of 1,300 members.<ref name=Maka/>{{sfn|Lesčius|2004|p=278}} '']'', reporting on renewed hostilities a year later, described the 1919 Sejny events as a violent occupation by the Poles, in which the Lithuanian inhabitants, teachers, and religious ministers were maltreated and expelled.<ref name=NYT/> Polish historian Łossowski notes that both sides mistreated the civilian population and exaggerated reports to gain internal and foreign support.{{sfn|Łossowski|1995|p=66}} | |||

| The uprising contributed to the deterioration of the ] and further discouraged the Lithuanians from joining the proposed ] federation.<ref name=Manc/><ref name=Pisa/>{{sfn|Łossowski|1995|p=68}} The Sejny Uprising doomed the Polish plan to ].<ref name=Manc/><ref name=Pisa/> After the uprising, the Lithuanian police and intelligence intensified their investigation of Polish sympathizers and soon uncovered the planned coup. They made mass arrests of Polish activists from August 27 to the end of September 1919. During the investigations, lists of PMO supporters were found; law enforcement completely suppressed the organisation in Lithuania.{{sfn|Lesčius|2004|p=270}} | |||

| Hostilities over the Suwałki Region resumed in summer 1920. When the Polish Army began to retreat during the course of the ], the Lithuanians moved to secure what they claimed to be their new borders, set by the ] of July 1920.<ref name=Senn/> The Peace Treaty granted Sejny and surrounding area to Lithuania. Poland did not recognize this bilateral treaty. Ensuing tensions heightened until the outbreak of the ]. Sejny changed hands frequently until it was controlled by Polish forces on September 22, 1920.<ref name=BuchKr/> The situation was legalized by the ] of October 7, 1920, which effectively returned the town to the Polish side of the border.{{sfn|Łossowski|1995|pp=166–175}} | |||

| ==Notes== | |||

| {{reflist|refs= | |||

| <ref name=BuchKr>{{cite journal|first=Krzysztof |last=Buchowski |author-link=Krzysztof Buchowski |url=http://www.lkma.lt/annuals/23annual_en.html |title=Polish-Lithuanian Relations in Seinai Region at the Turn of the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries |journal=The Chronicle of Lithuanian Catholic Academy of Sciences|issue=XXIII |volume=2 |year=2003 |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20070927015825/http://www.lkma.lt/annuals/23annual_en.html |archive-date = 2007-09-27}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=BuchSt>{{cite web | first=Stanisław | last=Buchowski | title=Powstanie Sejneńskie 23–28 sierpnia 1919 roku | publisher=Gimnazjum Nr. 1 w Sejnach | url=http://www.g1.powiat.sejny.pl/strony/buchowski.htm | access-date=2007-09-27 | language=pl | archive-date=2008-06-10 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080610050258/http://www.g1.powiat.sejny.pl/strony/buchowski.htm | url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=Loss>{{cite book | first=Piotr |last=Łossowski |title =Stosunki polsko-litewskie w latach 1918–1920 |year=1966 | publisher =Książka i Wiedza |location=Warsaw |oclc=9200888 |page=51|language=pl}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=Maka>{{cite journal | last = Makauskas | first = Bronius | title = Pietinės Sūduvos lietuviai už šiaudinės administracinės linijos ir geležinės sienos (1920–1991 m.) | journal = ] |volume=27–30 |issue=405–408 |date=1999-08-13 | url = http://www.voruta.lt/pietines-suduvos-lietuviai-uz-siaudines-administracines-linijos-ir-gelezines-sienos-1920%E2%80%931991-m/ | issn=1392-0677|language=lt}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=Manc>{{cite journal|first=Tadeusz |last=Mańczuk |year=2001 |title=Z Orłem przeciw Pogoni. Powstanie sejneńskie 1919 |journal=] |url=http://www.mowiawieki.pl/artykul.html?id_artykul=860 |access-date=2007-09-27 |language=pl |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071223034311/http://www.mowiawieki.pl/artykul.html?id_artykul=860 |archive-date=December 23, 2007 }}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=NYT>{{cite journal| url=https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1920/09/06/109799019.pdf |title=Poles Attacked By Lithuanians |first=Walter |last=Duranty |journal=] |date=1920-09-06 }}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=Pisa>{{cite web| first=Katarzyna |last=Pisarska |url=http://www.www.dawna-suwalszczyzna.com.pl/phpbb3/viewtopic.php?f=31&t=349 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120313135500/http://www.www.dawna-suwalszczyzna.com.pl/phpbb3/viewtopic.php?f=31&t=349 |archive-date=2012-03-13 | url-status=dead |title=Stosunki Polsko–Litewskie w latach 1926–1927 |access-date=2007-09-27|language=pl}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=Sejnhist>{{cite web |url=http://www.sejny.home.pl/historia |title=Historia |publisher=Urząd Miasta Sejny |access-date=2008-11-09 |language=pl |archive-date=2008-12-11 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081211201112/http://www.sejny.home.pl/historia |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=Senav>{{cite journal| title=Tautos budimas ir blaivybės sąjūdis| journal=Istorija| year=1999| first=Ieva| last=Šenavičienė| volume=40| page=3| issn=1392-0456| url=http://archyvas.istorijoszurnalas.lt/images/stories/Istorija_40/Istorija40.pdf| language=lt| access-date=2019-10-05| archive-date=2021-08-14| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210814130015/http://archyvas.istorijoszurnalas.lt/images/stories/Istorija_40/Istorija40.pdf| url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=Senn>{{cite book |first=Alfred Erich |last=Senn |title=The Great Powers: Lithuania and the Vilna Question, 1920–1928 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=180UAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA37 |publisher=Brill Archive |year=1966 |series=Studies in East European history |page=37 |lccn=67086623 }}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=Wsp>{{cite web| url=http://www.wspolnota-polska.org.pl/index.php?id=h23081919 |title=Powstanie Sejneńskie 1919 |publisher=] |access-date=2008-11-09|language=pl}}</ref> | |||

| }} | |||

| ==References== | |||

| {{refbegin}} | |||

| * {{cite book | last = Lesčius | first = Vytautas | title = Lietuvos kariuomenė nepriklausomybės kovose 1918–1920 | publisher = ], ] | year = 2004 | location = Vilnius | isbn = 9955-423-23-4 | url = http://www.lka.lt/download/7665/lietuvos_kariuomene_1.pdf | language = lt | access-date = 2019-12-27 | archive-date = 2015-01-02 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20150102043921/http://www.lka.lt/download/7665/lietuvos_kariuomene_1.pdf | url-status = dead }} | |||

| * {{cite book| first=Piotr |last=Łossowski |author-link=Piotr Łossowski |title=Konflikt polsko-litewski 1918-1920 |publisher= Książka i Wiedza |location=Warszawa |year=1995 |isbn=83-05-12769-9 |language=pl }} | |||

| * {{cite book| first=Alfred Erich |last=Senn | title=The Emergence of Modern Lithuania |publisher=Greenwood Press |orig-year=1959 |year=1975 |isbn=0-8371-7780-4 }} | |||

| {{refend}} | |||

| {{Polish uprisings}} | |||

| {{Polish wars and conflicts}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 05:15, 12 November 2024

Polish uprising against the Lithuanian authorities in August 1919

| Sejny Uprising | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Polish–Lithuanian War | |||||||||

Lt. Adam Rudnicki, leader of the Sejny Uprising, and his colleagues. August 1919. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

900–1,200 PMO volunteers 800 regular troops |

900 regular troops 300 volunteers | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

37 killed in action 70 wounded | |||||||||

| Polish–Lithuanian War | |

|---|---|

| Establishment of the Second Polish Republic | |

|---|---|

The Sejny Uprising or Seinai Revolt (Polish: Powstanie sejneńskie, Lithuanian: Seinų sukilimas) refers to a Polish uprising against the Lithuanian authorities in August 1919 in the ethnically mixed area surrounding the town of Sejny (Lithuanian: Seinai). When German forces, which occupied the territory during World War I, retreated from the area in May 1919, they turned over administration to the Lithuanians. Trying to prevent an armed conflict between Poland and Lithuania, the Entente drew a demarcation line, known as the Foch Line. The line assigned much of the disputed Suwałki (Suvalkai) Region to Poland and required the Lithuanian Army to retreat. While the Lithuanians retreated from some areas, they refused to leave Sejny (Seinai), because of its major Lithuanian population. Polish irregular forces began the uprising on August 23, 1919, and soon received support from the regular Polish Army. After several military skirmishes, Polish forces secured Sejny and the Lithuanians retreated behind the Foch Line.

The uprising did not solve the larger border conflict between Poland and Lithuania over the ethnically mixed Suwałki Region. Both sides complained about each other's repressive measures. The conflict intensified in 1920, causing military skirmishes of the Polish–Lithuanian War. Sejny changed hands frequently until the Suwałki Agreement of October 1920, which left Sejny on the Polish side. The uprising undermined the plans of Polish leader Józef Piłsudski who was planning a coup d'état in Lithuania to replace the Lithuanian government with a pro-Polish cabinet which would agree to a union with Poland (the proposed Międzymorze federation). Because the Sejny Uprising had prompted the Lithuanian intelligence to intensify its investigations of Polish activities in Lithuania, they discovered plans for the coup and prevented it, arresting Polish sympathizers. These hostilities in Sejny further strained the Polish–Lithuanian relations.

Eventually, Poland and Lithuania reached an agreement on a new border that left Sejny on the Polish side of the border. The Polish–Lithuanian border in the Suwałki Region has remained the same since then (with the exception of the World War II period).

Background

During the ages, the lands surrounding the town of Suwałki were part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania until 1795. Sejny itself was property of Vilnius' Dominican friars from 1603 until 1805. During the Third Partition of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1795, the region became part of the Kingdom of Prussia as New East Prussia until 1807, from then until 1815, it was part of the Duchy of Warsaw which Napoleon had created. For a century after the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars, the town was in Congress Poland, a part of the Russian Empire.

During World War I, the region was captured by the German Empire, which intended to incorporate the area into its province of East Prussia. After the German defeat, the victorious Entente was willing to assign the territory to either the newly independent Poland or Lithuania. The future of the region was discussed at the Paris Peace Conference in January 1919. The Germans, whose former Ober-Ost administration was preparing to evacuate, initially supported leaving the area to a Polish administration. However, as Poland was becoming an ally of France, German support gradually shifted towards Lithuania. In July 1919, when the German troops began their slow retreat from the area, they delegated the administration to local Lithuanian authorities. Lithuanian officers and troops, who first arrived in the region in May, began to organize military units in the pre-war Sejny county.

According to Russian statistics from 1889, there were 57.8% Lithuanians, 19.1% Poles, and 3.5% Belarusians in the Suwałki Governorate. It is generally agreed that Lithuanians formed the majority of the population in the northern Suwałki Governorate, while Poles were concentrated in the south. But Lithuanian and Polish historians and political scientists continued to disagree over the location of the line that separated the areas of Lithuanian and Polish majorities. Lithuanians claimed that Sejny and the surrounding area were inhabited primarily by the Lithuanians, while the Poles claimed exactly the opposite. The German census of 1916 showed that 51% of Sejny population was Lithuanian.

Demarcation lines

In the aftermath of World War I, the Conference of Ambassadors drew the first demarcation line between Poland and Lithuania on June 18, 1919. The line satisfied no one, and Polish troops continued to advance deeper into the Lithuanian-controlled territory. These attacks coincided with the signing of the Treaty of Versailles on June 28, which eliminated any danger from Germany. Attempting to halt further hostilities, Marshal of France Ferdinand Foch proposed a new line, known as the Foch Line, on July 18, 1919.

The Foch Line was negotiated with the Polish war mission, led by General Tadeusz Jordan-Rozwadowski in Paris, while Lithuanian representatives were not invited. The Foch Line had two major modifications compared to the June 18 line: first, the entire line was moved west to give extra protection to the strategic Warsaw – Saint Petersburg Railway and second, the Suwałki Region, including the towns of Sejny, Suwałki, Puńsk, was assigned to Poland. Despite assurances at the time that the line was just a temporary measure to normalize the situation before full negotiations could take place, the southern Foch Line is the present-day Lithuania–Poland border.

On July 26, the Foch Line was accepted by the Conference of Ambassadors as the provisional border between the two states. Lithuanians were not informed about this decision until August 3. Neither country was satisfied: both Lithuanian and Polish forces would have to retreat from the Suwałki and Vilnius regions, respectively. Those Germans still present in the region also objected to the boundary of the line. The Lithuanian forces (about 350 strong) left the town of Suwałki by August 7, but stopped in Sejny and formed a line at the Czarna Hańcza river – Wigry Lake, thus effectively violating the demarcation line. Lithuanians believed that the Foch Line was not the final decision, and that they had the duty to protect Lithuanian outposts in the region.

Uprising preparations

On August 12, 1919, two days after the Germans retreated from Sejny, a Polish meeting in the town attracted over 100 delegates from neighboring Polish communities; the meeting passed a resolution that "only securing the area by Polish Army can solve the problem." The Sejny branch of the Polish Military Organization (PMO), led by Polish regular army officers Adam Rudnicki and Wacław Zawadzki, began preparing for the uprising on August 16. PMO members and local militia volunteers numbered some 900 or 1,200 men (sources vary). The uprising was scheduled for the night of August 22 to 23, 1919. The date was chosen to coincide with the withdrawal of German troops from the town of Suwałki. The Poles hoped to capture the territory up to the Foch Line and advance further to take control of the towns of Seirijai, Lazdijai, Kapčiamiestis as far as Simnas.

According to the Polish historian Tadeusz Mańczuk, Piłsudski – who was planning a coup d'état in Kaunas – discouraged the local PMO activists from carrying out the Sejny Uprising. Piłsudski reasoned that any hostilities could leave Lithuanians even more opposed to the proposed union with Poland (see Międzymorze). The local PMO disregarded his recommendations and launched the uprising. While locally successful, it led to the failure of the nationwide coup.

On August 17, a Lithuanian counter-demonstration was staged. Its participants read aloud a recently issued recruiting proclamation of the Lithuanian volunteer army: "Citizens! Our nation is in danger! To arms! We shall leave not a single occupant on our lands!" On August 20, Prime Minister of Lithuania Mykolas Sleževičius visited Sejny and called on Lithuanians to defend their lands "to the end, however they can, with axes, pitchforks and scythes". According to Lesčius, at the time the Lithuanian command in Sejny had only 260 infantry and 70 cavalry personnel, stretched along the long line of defense. There were only 10 Lithuanian guards and 20 clerical staff in the town itself. Mańczuk and Buchowski note that the Polish insurgents estimated the Lithuanian forces at 1,200 infantry (Mańczuk also adds an estimate of 120 cavalry), including a 400-strong garrison in Sejny.

Military skirmishes

According to the Lithuanian historian Lesčius, the first Polish assault of about 300 PMO members on August 22 was repelled, but the next day Lithuanians were forced to retreat towards Lazdijai. Over 100 Lithuanians were imprisoned in Sejny when their commander Bardauskas sided with the Poles. The Polish insurgents also attacked Lazdijai and Kapčiamiestis, towns on the Lithuanian side of the Foch Line.

In early morning of August 25, Lithuanians counterattacked and recaptured Sejny. Polish sources claim that Lithuanians there were aided by a company of Germans volunteers, but Lithuanian sources assert that it was an excuse used by Rudnicki to explain his defeat. The Lithuanian forces recovered some important documents and property, freed Lithuanian prisoners and, according to Mańczuk, executed several of the PMO fighters they found wounded.

On the evening of August 25, the first regular unit (41st Infantry Regiment) of the Polish Army received an order to advance towards Sejny. The Lithuanian forces retreated on the same day when they learned about the approaching Polish reinforcements. According to Mańczuk, they based their retreat on an erroneous report about a "large Polish cavalry unit" operating to their rear; only small groups of Polish partisans operated there. Later the next day, during the afternoon of August 26, the PMO forces in Sejny were joined by the 41st Infantry Regiment.

On August 26, a large anti-Polish protest took place in Lazdijai, with cries to march on Sejny. The last Lithuanian attempt to retake the town was made on August 28. The Lithuanians (about 650 men) were defeated by the combined forces of the Polish Army (800 men) and PMO volunteers (500 men). On August 27, the Poles officially demanded that Lithuanians retreat behind the Foch Line. On September 1, Rudnicki announced incorporation of PMO volunteers into the 41st Infantry Regiment. During the negotiations on September 5, representatives of the two groups agreed to settle on a detailed demarcation line; Lithuanians agreed to retreat by September 7. The Polish regular army units did not cross the Foch Line, and refused to aid the PMO insurgents still operating on the Lithuanian side.

Polish sources give total Polish casualties for the Sejny Uprising as 37 killed in action and 70 wounded.

Aftermath

After the uprising, Poland repressed Lithuanian cultural life in Sejny. Lithuanian schools in Sejny (which had some 300 pupils) and surrounding villages were closed. The local Lithuanian clergy were evicted, and the Sejny Priest Seminary relocated. According to the Lithuanians, the repressions were even more far-reaching, including a ban on public use of the Lithuanian language and the closing of Lithuanian organizations, which had a total of 1,300 members. The New York Times, reporting on renewed hostilities a year later, described the 1919 Sejny events as a violent occupation by the Poles, in which the Lithuanian inhabitants, teachers, and religious ministers were maltreated and expelled. Polish historian Łossowski notes that both sides mistreated the civilian population and exaggerated reports to gain internal and foreign support.

The uprising contributed to the deterioration of the Polish–Lithuanian relations and further discouraged the Lithuanians from joining the proposed Międzymorze federation. The Sejny Uprising doomed the Polish plan to overthrow the Lithuanian government in a coup d'état. After the uprising, the Lithuanian police and intelligence intensified their investigation of Polish sympathizers and soon uncovered the planned coup. They made mass arrests of Polish activists from August 27 to the end of September 1919. During the investigations, lists of PMO supporters were found; law enforcement completely suppressed the organisation in Lithuania.

Hostilities over the Suwałki Region resumed in summer 1920. When the Polish Army began to retreat during the course of the Polish–Soviet War, the Lithuanians moved to secure what they claimed to be their new borders, set by the Soviet–Lithuanian Peace Treaty of July 1920. The Peace Treaty granted Sejny and surrounding area to Lithuania. Poland did not recognize this bilateral treaty. Ensuing tensions heightened until the outbreak of the Polish–Lithuanian War. Sejny changed hands frequently until it was controlled by Polish forces on September 22, 1920. The situation was legalized by the Suwałki Agreement of October 7, 1920, which effectively returned the town to the Polish side of the border.

Notes

- ^ Buchowski, Stanisław. "Powstanie Sejneńskie 23–28 sierpnia 1919 roku" (in Polish). Gimnazjum Nr. 1 w Sejnach. Archived from the original on 2008-06-10. Retrieved 2007-09-27.

- ^ Mańczuk, Tadeusz (2001). "Z Orłem przeciw Pogoni. Powstanie sejneńskie 1919". Mówią Wieki (in Polish). Archived from the original on December 23, 2007. Retrieved 2007-09-27.

- ^ Lesčius 2004, p. 276.

- ^ Lesčius 2004, p. 275.

- Senn 1975, p. 158.

- ^ Buchowski, Krzysztof (2003). "Polish-Lithuanian Relations in Seinai Region at the Turn of the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries". The Chronicle of Lithuanian Catholic Academy of Sciences. 2 (XXIII). Archived from the original on 2007-09-27.

- ^ "Powstanie Sejneńskie 1919" (in Polish). Association "Polish Community". Retrieved 2008-11-09.

- ^ "Historia" (in Polish). Urząd Miasta Sejny. Archived from the original on 2008-12-11. Retrieved 2008-11-09.

- ^ Pisarska, Katarzyna. "Stosunki Polsko–Litewskie w latach 1926–1927" (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2012-03-13. Retrieved 2007-09-27.

- ^ Lesčius 2004, p. 271.

- ^ Makauskas, Bronius (1999-08-13). "Pietinės Sūduvos lietuviai už šiaudinės administracinės linijos ir geležinės sienos (1920–1991 m.)". Voruta (in Lithuanian). 27–30 (405–408). ISSN 1392-0677.

- Šenavičienė, Ieva (1999). "Tautos budimas ir blaivybės sąjūdis" (PDF). Istorija (in Lithuanian). 40: 3. ISSN 1392-0456. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-08-14. Retrieved 2019-10-05.

- ^ Łossowski 1995, p. 51.

- Senn 1975, p. 133.

- Lesčius 2004, p. 254.

- Senn 1975, p. 132.

- Lesčius 2004, pp. 254, 257.

- Senn 1975, p. 135.

- Senn 1975, p. 134.

- Łossowski, Piotr (1966). Stosunki polsko-litewskie w latach 1918–1920 (in Polish). Warsaw: Książka i Wiedza. p. 51. OCLC 9200888.

- Lesčius 2004, p. 272.

- ^ Lesčius 2004, p. 273.

- ^ Lesčius 2004, p. 274.

- ^ Łossowski 1995, p. 67.

- Lesčius 2004, pp. 274–275.

- Lesčius 2004, p. 275–276.

- Lesčius 2004, p. 277.

- Lesčius 2004, p. 278.

- Duranty, Walter (1920-09-06). "Poles Attacked By Lithuanians" (PDF). The New York Times.

- Łossowski 1995, p. 66.

- Łossowski 1995, p. 68.

- Lesčius 2004, p. 270.

- Senn, Alfred Erich (1966). The Great Powers: Lithuania and the Vilna Question, 1920–1928. Studies in East European history. Brill Archive. p. 37. LCCN 67086623.

- Łossowski 1995, pp. 166–175.

References

- Lesčius, Vytautas (2004). Lietuvos kariuomenė nepriklausomybės kovose 1918–1920 (PDF) (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Vilnius University, General Jonas Žemaitis Military Academy of Lithuania. ISBN 9955-423-23-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-01-02. Retrieved 2019-12-27.

- Łossowski, Piotr (1995). Konflikt polsko-litewski 1918-1920 (in Polish). Warszawa: Książka i Wiedza. ISBN 83-05-12769-9.

- Senn, Alfred Erich (1975) . The Emergence of Modern Lithuania. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-8371-7780-4.

| Polish uprisings | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kingdom of Poland |  | ||||

| Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth |

| ||||

| After the partitions | |||||

| Second Republic | |||||

| World War II |

| ||||

| Polish wars and conflicts | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General and related |

| ||||||||

| Piast Poland |

| ||||||||

| Jagiellon Poland |

| ||||||||

| Commonwealth |

| ||||||||

| Poland partitioned | |||||||||

| Second Republic | |||||||||

| World War II in Poland |

| ||||||||

| People's Republic | |||||||||

| Third Republic | |||||||||