| Revision as of 20:50, 15 October 2007 view sourceMatt Lewis (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Rollbackers9,196 edits →Risk reducers: Added a fuller picture to Vitamin E. Needs a few citations, which are available...← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 07:07, 26 December 2024 view source FropFrop (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users1,008 editsm →Causes: Seems like the content has been moved a couple of times without anyone updating the article links | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Progressive neurodegenerative disease}} | |||

| {{DiseaseDisorder infobox | |||

| {{Redirect|Alzheimer|the ]|Alois Alzheimer|other uses|Alzheimer (disambiguation)}} | |||

| | Name = Alzheimer's disease | |||

| {{Pp-semi-indef}} | |||

| | Image = Alzheimer dementia (3) presenile onset.jpg | |||

| {{Pp-move}} | |||

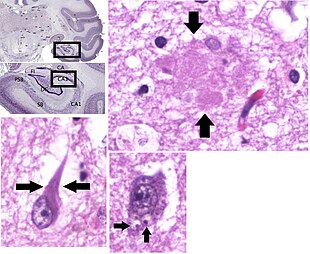

| | Caption = ] image of senile plaques seen in the cerebral cortex in a patient with Alzheimer disease of presenile onset. Silver impregnation. | |||

| {{Use British English|date=March 2022}} | |||

| | DiseasesDB = 490 | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=July 2023}} | |||

| | ICD10 = {{ICD10|G|30||g|30}}, {{ICD10|F|00||f|00}} | |||

| {{Cs1 config|name-list-style=vanc|display-authors=6}} | |||

| | ICD9 = {{ICD9|331.0}}, {{ICD9|290.1}} | |||

| {{Infobox medical condition (new) | |||

| | ICDO = | |||

| | name = Alzheimer's disease | |||

| | OMIM = 104300 | |||

| | image = Brain-ALZH.png | |||

| | MedlinePlus = 000760 | |||

| | caption = Diagram of a normal ] compared to the brain of a person with Alzheimer's | |||

| | eMedicineSubj = neuro | |||

| | pronounce = {{IPAc-en|ˈ|æ|l|t|s|h|aɪ|m|ər|z}}, {{IPAc-en|usalso|ˈ|ɑː|l|t|s|-}} | |||

| | eMedicineTopic = 13 | |||

| | field = ] | |||

| | MeshID = | |||

| | synonyms = Alzheimer's dementia | |||

| |}} | |||

| | symptoms = ], ], ], ]s<ref name=Knopman2021 /><ref name=WHO2023/> | |||

| | complications = ]s, ] and ] in the terminal stage<ref name=":0">{{Cite web |title=Ask the Doctors - What is the cause of death in Alzheimer's disease? |url=https://www.uclahealth.org/news/ask-the-doctors-what-is-the-cause-of-death-in-alzheimers-disease |access-date=2024-03-18 |website=www.uclahealth.org |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| | onset = Over 65 years old<ref name=Mend2012 /> | |||

| | duration = Long term<ref name=WHO2023/> | |||

| | causes = Poorly understood<ref name=Knopman2021 /> | |||

| | risks = ], ], ], ],<ref name=Knopman2021 /> ],<ref name="Yu 1201–1209"/> lack of physical<ref name=Cheng2016/> and mental<ref name="Yu 1201–1209"/><ref name=Vina2018/> exercise | |||

| | diagnosis = Based on symptoms and ]ing after ruling out other possible causes<ref name=NICE2014Diag /> | |||

| | differential = ],<ref name=Knopman2021 /> ],<ref name=Gomperts2016>{{cite journal | vauthors = Gomperts SN | title = Lewy Body Dementias: Dementia With Lewy Bodies and Parkinson Disease Dementia | journal = Continuum | volume = 22 | issue = 2 Dementia | pages = 435–463 | date = April 2016 | pmid = 27042903 | pmc = 5390937 | doi = 10.1212/CON.0000000000000309 | type = Review |issn = 1080-2371}}</ref> ]<ref name=Lott2019>{{cite journal |vauthors=Lott IT, Head E |title=Dementia in Down syndrome: unique insights for Alzheimer disease research |journal=Nat Rev Neurol |volume=15 |issue=3 |pages=135–147 |date=March 2019 |pmid=30733618 |pmc=8061428 |doi=10.1038/s41582-018-0132-6 }}</ref> | |||

| | prevention = | |||

| | treatment = | |||

| | medication = ]s, ]s<ref name="mayo">{{Cite web |date=2023-08-30 |title=How Alzheimer's drugs help manage symptoms |url=https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/alzheimers-disease/in-depth/alzheimers/art-20048103 |access-date=2024-03-19 |website=Mayo Clinic |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| | prognosis = Life expectancy 3–12 years<ref name="mayo" /><ref name="schaffert">{{cite journal | vauthors = Schaffert J, LoBue C, Hynan LS, Hart J, Rossetti H, Carlew AR, Lacritz L, White CL, Cullum CM | title = Predictors of Life Expectancy in Autopsy-Confirmed Alzheimer's Disease | journal = Journal of Alzheimer's Disease | volume = 86 | issue = 1 | pages = 271–281 | date = 2022 | pmid = 35034898 | pmc = 8966055 | doi = 10.3233/JAD-215200 }}</ref><ref name="todd">{{cite journal | vauthors = Todd S, Barr S, Roberts M, Passmore AP | title = Survival in dementia and predictors of mortality: a review | journal = International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry | volume = 28 | issue = 11 | pages = 1109–1124 | date = November 2013 | pmid = 23526458 | doi = 10.1002/gps.3946 }}</ref> | |||

| | frequency = 50 million (2020)<ref name=Breijyeh2020 /> | |||

| | deaths = | |||

| | named after = ] | |||

| }} | |||

| <!-- Definition and symptoms --> | |||

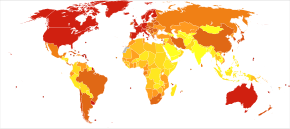

| '''Alzheimer's disease''' ('''AD'''), also known simply as '''Alzheimer's''', is a ] that, in its most common form, is found in people over age 65. Approximately 24 million people worldwide have dementia of which the majority (~60%) is due to Alzheimer's.<ref> {{cite journal |author=Ferri CP, Prince M, Brayne C, ''et al'' |title=Global prevalence of dementia: a Delphi consensus study |journal=Lancet |volume=366 |issue=9503 |pages=2112-7 |year=2005 |pmid=16360788 |doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67889-0}} </ref> | |||

| '''Alzheimer's disease''' ('''AD''') is a ] that usually starts slowly and progressively worsens.<ref name=WHO2023>{{cite web|date=15 March 2023|title=Dementia Fact sheet|url=https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia|publisher=World Health Organization|access-date=10 July 2023 }}</ref> It is the cause of 60–70% of cases of ].<ref name=WHO2023/><ref name=Simon2018p111 /> The most common early symptom is difficulty in ].<ref name=Knopman2021 /> As the disease advances, symptoms can include ], ] (including easily getting lost), ]s, loss of ], ], and ].<ref name=WHO2023/> As a person's condition declines, they often ].<ref name=BMJ2009>{{cite journal | vauthors = Burns A, Iliffe S | title = Alzheimer's disease | journal = BMJ | volume = 338 | pages = b158 | date = February 2009 | pmid = 19196745 | doi = 10.1136/bmj.b158 | s2cid = 8570146 }}</ref> Gradually, bodily functions are lost, ultimately leading to death. Although the speed of progression can vary, the average life expectancy following diagnosis is three to twelve years.<ref name="mayo" /><ref name="schaffert" /><ref name="todd" /> | |||

| <!-- Cause, diagnosis and prevention --> | |||

| Clinical signs of Alzheimer's disease are characterized by progressive cognitive deterioration, together with declining activities of daily living and by ] symptoms or behavioral changes. It is the most common type of ]. Plaques which contain misfolded peptides called amyloid beta (Aβ) are formed in the brain many years before the clinical signs of Alzheimer's are observed. Together, these plaques and ] form the pathological hallmarks of the disease. These features can only be discovered at autopsy and help to confirm the clinical diagnosis. Medications can help reduce the symptoms of the disease, but they cannot change the course of the underlying pathology. | |||

| The causes of Alzheimer's disease remain poorly understood.<ref name=BMJ2009 /> There are many environmental and genetic ]s associated with its development. The strongest genetic risk factor is from an ] of ].<ref name=Long /><ref name=NIA2021>{{cite web |title=Study reveals how APOE4 gene may increase risk for dementia |url=https://www.nia.nih.gov/news/study-reveals-how-apoe4-gene-may-increase-risk-dementia |publisher=National Institute on Aging |date=16 March 2021 |access-date=17 March 2021 |archive-date=17 March 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210317180050/https://www.nia.nih.gov/news/study-reveals-how-apoe4-gene-may-increase-risk-dementia |url-status=live }}</ref> Other risk factors include a history of ], ], and ].<ref name=Knopman2021 /> The progression of the disease is largely characterized by the accumulation of ] in the ], called ] and ]. These misfolded ] interfere with normal cell function, and over time lead to irreversible ] and loss of ] in the ].<ref name="NIA2023">{{cite web |title=Alzheimer's Disease Fact Sheet |url=https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/alzheimers-disease-fact-sheet |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220323200727/https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/alzheimers-disease-fact-sheet |archive-date=23 March 2022 |access-date=23 March 2022 |publisher=National Institute on Aging}}</ref> A probable diagnosis is based on the history of the illness and ]ing, with ] and ]s to rule out other possible causes.<ref name=NICE2014Diag>{{cite web |title=Dementia diagnosis and assessment |publisher=National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) |url=http://pathways.nice.org.uk/pathways/dementia/dementia-diagnosis-and-assessment.pdf|access-date=30 November 2014|url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141205184403/http://pathways.nice.org.uk/pathways/dementia/dementia-diagnosis-and-assessment.pdf|archive-date=5 December 2014}}</ref><ref>{{cite report | title=Dementia: assessment, management and support for people living with dementia and their carers | publisher=] (NICE) | date=20 June 2018 | url=https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng97 | access-date=8 July 2023 | id=NG97 }}</ref> Initial symptoms are often mistaken for ].<ref name=BMJ2009 /> ] is needed for a definite diagnosis, but this can only take place ].<ref name=Khan2020 /><ref name=Gauthreaux2020 /> | |||

| <!-- Management --> | |||

| The ultimate cause of Alzheimer's is unknown. Genetic factors are clearly indicated as evidenced by dominant ] in three different genes have been identified that account for the small number of cases of ]. For the more common form of late onset AD (LOAD), ] is the only clearly established susceptibility gene. All four genes can contain mutations or variants that confer increased risk for AD, but account for only 30% of the genetic picture of AD. These four genes have in common the fact that mutations in each lead to the excessive accumulation in the brain of Aβ, the main component of the senile plaques that litter the brains of AD patients.<ref name="decoding darkness"> "Decoding Darkness: The Search for the Genetics Causes of Alzheimer's Disease", Rudolph Tanzi and Ann Parson, Perseus Press, 2000</ref>. | |||

| No treatments can stop or reverse its progression, though some may temporarily improve symptoms.<ref name=WHO2023/> A healthy diet, physical activity, and ] are generally beneficial in aging, and may help in reducing the risk of cognitive decline and Alzheimer's.<ref name="NIA2023" /> Affected people become increasingly reliant on others for assistance, often placing a burden on ].<ref name=Thom2007 /> The pressures can include social, psychological, physical, and economic elements.<ref name=Thom2007>{{cite journal | vauthors = Thompson CA, Spilsbury K, Hall J, Birks Y, Barnes C, Adamson J | title = Systematic review of information and support interventions for caregivers of people with dementia | journal = BMC Geriatrics | volume = 7 | pages = 18 | date = July 2007 | pmid = 17662119 | pmc = 1951962 | doi = 10.1186/1471-2318-7-18 | doi-access = free }}</ref> Exercise programs may be beneficial with respect to ] and can potentially improve outcomes.<ref name=Forb2015>{{cite journal | vauthors = Forbes D, Forbes SC, Blake CM, Thiessen EJ, Forbes S | title = Exercise programs for people with dementia | journal = The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | volume = 132 | issue = 4 | pages = CD006489 | date = April 2015 | pmid = 25874613 | doi = 10.1002/14651858.CD006489.pub4 | pmc = 9426996 | type = Submitted manuscript }}</ref> Behavioral problems or ] due to dementia are sometimes treated with ]s, but this has an increased risk of early death.<ref>{{cite web |title=Low-dose antipsychotics in people with dementia |publisher=National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) |url=https://www.nice.org.uk/advice/ktt7/resources/non-guidance-lowdose-antipsychotics-in-people-with-dementia-pdf|access-date=29 November 2014|url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141205183329/https://www.nice.org.uk/advice/ktt7/resources/non-guidance-lowdose-antipsychotics-in-people-with-dementia-pdf|archive-date=5 December 2014}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |date=16 June 2008 |title=Information for Healthcare Professionals: Conventional Antipsychotics |publisher=US Food and Drug Administration |url=https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm124830.htm|access-date=29 November 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141129015823/https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drugsafety/postmarketdrugsafetyinformationforpatientsandproviders/ucm124830.htm|archive-date=29 November 2014 | url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| <!-- Epidemiology, history, society, and research--> | |||

| ==History== | |||

| As of 2020, there were approximately 50 million people worldwide with Alzheimer's disease.<ref name=Breijyeh2020 /> It most often begins in people over 65 years of age, although up to 10% of cases are ] impacting those in their 30s to mid-60s.<ref name=NIA2019>{{cite web |title=Alzheimer's Disease Fact Sheet |url=https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/alzheimers-disease-fact-sheet |publisher=National Institute on Aging |access-date=25 January 2021 |archive-date=24 January 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210124194838/https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/alzheimers-disease-fact-sheet |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name=Mend2012>{{cite journal | vauthors = Mendez MF | title = Early-onset Alzheimer's disease: nonamnestic subtypes and type 2 AD | journal = Archives of Medical Research | volume = 43 | issue = 8 | pages = 677–685 | date = November 2012 | pmid = 23178565 | pmc = 3532551 | doi = 10.1016/j.arcmed.2012.11.009 }}</ref> It affects about 6% of people 65 years and older,<ref name=BMJ2009 /> and women more often than men.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Zhu D, Montagne A, Zhao Z |title=Alzheimer's pathogenic mechanisms and underlying sex difference |journal=Cell Mol Life Sci |volume=78 |issue=11 |pages=4907–4920 |date=June 2021 |pmid=33844047 |pmc=8720296 |doi=10.1007/s00018-021-03830-w }}</ref> The disease is named after German psychiatrist and pathologist ], who first described it in 1906.<ref name=pmid9661992 /> Alzheimer's financial burden on society is large, with an estimated global annual cost of {{US$|1}}{{nbsp}}trillion.<ref name=Breijyeh2020 /> It is ranked as the ] worldwide.<ref>{{Cite web |title=The top 10 causes of death |url=https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death |access-date=2024-03-19 |website=www.who.int |language=en}}</ref> | |||

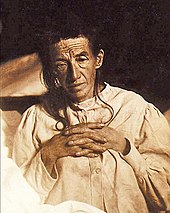

| ].]] | |||

| <!-- Public and private funding of Alzheimer's research --> | |||

| In 1901, ], a German psychiatrist, identified the first case of what became known as Alzheimer's disease, in a 50 year-old patient ] and followed her to her death in 1906, when he first reported the case publicly.<ref> {{cite book | last =Maurer | first =Konrad | coauthors =Maurer, Ulrike | title = Alzheimer: the life of a physician and the career of a disease | publisher = Columbia University Press | date =2003 | location =New York | id= ISBN 0-231-11896-1}}</ref> | |||

| Given the widespread impacts of Alzheimer's disease, both basic-science and health funders in many countries support Alzheimer's research at large scales. For example, the US ] program for Alzheimer's research, the National Plan to Address Alzheimer’s Disease, has a budget of US$3.98 billion for fiscal year 2026.<ref>{{Cite web|vauthors=Bertagnolli MM|title=Fiscal Year 2026 NIH Professional Judgment Budget for Alzheimer's Disease and Related Dementias Research: Advancing Progress in Dementia Research |url=https://www.nia.nih.gov/about/budget/fy26-professional-judgment-budget-proposal|date=5 August 2024|access-date=23 September 2024 |publisher=US National Institutes of Health}}</ref> In the ], the 2020 ] research programme awarded over €570 million for dementia-related projects.<ref>{{Cite journal|url=https://www.alzheimer-europe.org/policy/eu-action/horizon-europe-research-programme-0?language_content_entity=en|title=Horizon Europe research programme|via=www.alzheimer-europe.org}}</ref> | |||

| For most of the twentieth century, the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease was reserved for individuals between the ages of 45 and 65 who developed symptoms of ''presenile'' ]. ''Senile'' dementia, as a set of symptoms, was considered to be a relatively normal outcome of the aging process, and thought to be due to age-related brain arterial "hardening." In the ] and early-], because the symptoms and brain pathology were identical for any age, the name "Alzheimer's disease" became used equally for afflicted individuals of all ages; however, the term ''senile dementia of the Alzheimer type'' (SDAT) was often used to describe the condition in those over 65. Eventually, the term Alzheimer's disease was formally adopted in medical nomenclature to describe individuals of all ages with the characteristic common symptom pattern, disease course, and neuropathology. The term ''Alzheimer disease'' (without the apostrophe and s) is also sometimes used in literature for learning. | |||

| {{TOC limit|3}} | |||

| ==Signs and symptoms== | |||

| ==Etiology== | |||

| The course of Alzheimer's is generally described in three stages, with a progressive pattern of ] and ] ].<ref name=NHS2018>{{cite web|title=Alzheimer's disease – Symptoms|url=https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/alzheimers-disease/symptoms/|website=] (NHS)|date=10 May 2018|access-date=25 January 2021|archive-date=30 January 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210130034141/https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/alzheimers-disease/symptoms/|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name=NIA2019 /> The three stages are described as early or mild, middle or moderate, and late or severe.<ref name=NHS2018 /> The disease is known to target the ] which is associated with ], and this is responsible for the first symptoms of memory impairment. As the disease progresses so does the degree of memory impairment.<ref name=NIA2023/> | |||

| Most cases of Alzheimer's disease are sporadic, i.e., do not exhibit familial inheritance requiring the patient to have two or more first-degree relatives with the disease. Nonetheless, at least 80% of sporadic AD cases most likely involve genetic risk factors based on twin studies. 5-10% of AD cases involve a clear familial pattern of inheritance in which the patient has at least two first-degree relatives with a history of AD <ref> From the ]</ref> The relative contribution of genetics and environment to the sporadic cases is unclear, but are accepted to be of multifactorial origin. In early-onset (<60 years) familial AD, genetic defects identified include mutations in the presenlin 1 gene on chromosome 14, the presenilin 2 gene on chromosome 1, and the amyloid precursor protein (APP) gene on chromosome 21. ApoE is contributes to risk in roughly half of all late-onset sporadic AD cases which comprise 90-95% of total AD. <ref name="decoding darkness">. | |||

| == |

===First symptoms=== | ||

| ] in Alzheimer's]] | |||

| The first readily identified symptoms of Alzheimer's disease are usually short-term memory loss and visual-spatial confusion. These initial symptoms progress from seemingly simple and often fluctuating ] and difficulty orienting oneself in space such as in a traffic lane while driving, to a more pervasive loss of ] and difficulty navigating through familiar areas such as one's neighborhood, then to loss of other familiar and well-known skills as well as recognition of objects and persons.<ref>Kumru, Liz. UNMC. Accessed 22 July 2007.</ref><ref>Rickey, Tom. (31 January 2002) Accessed 21 July 2007.</ref> | |||

| The first symptoms are often mistakenly attributed to ] or ].<ref name=Waldemar2007>{{cite journal | vauthors = Waldemar G, Dubois B, Emre M, Georges J, McKeith IG, Rossor M, Scheltens P, Tariska P, Winblad B |title = Recommendations for the diagnosis and management of Alzheimer's disease and other disorders associated with dementia: EFNS guideline | journal = European Journal of Neurology | volume = 14 | issue = 1 | pages = e1-26 | date = January 2007 | pmid = 17222085 | doi = 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01605.x | s2cid = 2725064 | doi-access = free | title-link = doi | author6-link = Martin Rossor }}</ref> Detailed ]ing can reveal mild cognitive difficulties up to eight years before a person fulfills the clinical criteria for ] of Alzheimer's disease.<ref name=pmid15324363>{{cite journal | vauthors = Bäckman L, Jones S, Berger AK, Laukka EJ, Small BJ | title = Multiple cognitive deficits during the transition to Alzheimer's disease | journal = Journal of Internal Medicine | volume = 256 | issue = 3 | pages = 195–204 | date = September 2004 | pmid = 15324363 | doi = 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01386.x | s2cid = 37005854 | doi-access = free | title-link = doi }}</ref> These early symptoms can affect the most complex ].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Nygård L | title = Instrumental activities of daily living: a stepping-stone towards Alzheimer's disease diagnosis in subjects with mild cognitive impairment? | journal = Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. Supplementum | volume = 179 | issue = s179 | pages = 42–46 | year = 2003 | pmid = 12603250 | doi = 10.1034/j.1600-0404.107.s179.8.x | s2cid = 25313065 }}</ref> The most noticeable deficit is ] loss, which shows up as difficulty in remembering recently learned facts and inability to acquire new information.<ref name=pmid15324363 /> | |||

| Subtle problems with the ] of ], ], flexibility, and ], or impairments in ] (memory of meanings, and concept relationships) can also be symptomatic of the early stages of Alzheimer's disease.<ref name=pmid15324363 /> ] and depression can be seen at this stage, with apathy remaining as the most persistent symptom throughout the course of the disease.<ref name=Deardorff>{{cite book | vauthors = Deardorff WJ, Grossberg GT | title = Psychopharmacology of Neurologic Disease | chapter = Behavioral and psychological symptoms in Alzheimer's dementia and vascular dementia | series = Handbook of Clinical Neurology | volume = 165 | pages = 5–32 | date = 2019 | publisher = Elsevier | pmid = 31727229 | doi = 10.1016/B978-0-444-64012-3.00002-2 | isbn = 978-0-444-64012-3 | s2cid = 208037448 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |title=Bradley's neurology in clinical practice|year=2012 |publisher=Elsevier/Saunders|location=Philadelphia, PA|isbn=978-1-4377-0434-1 |vauthors=Murray ED, Buttner N, Price BH|edition=6th|veditors=Bradley WG, Daroff RB, Fenichel GM, Jankovic J |chapter=Depression and Psychosis in Neurological Practice}}</ref> People with objective signs of cognitive impairment, but not more severe symptoms, may be diagnosed with ] (MCI). If memory loss is the predominant symptom of MCI, it is termed ] and is frequently seen as a ] or early stage of Alzheimer's disease.<ref name=Petersen>{{cite journal | vauthors = Petersen RC, Lopez O, Armstrong MJ, Getchius TS, Ganguli M, Gloss D, Gronseth GS, Marson D, Pringsheim T, Day GS, Sager M, Stevens J, Rae-Grant A | title = Practice guideline update summary: Mild cognitive impairment: Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology | journal = Neurology | volume = 90 | issue = 3 | pages = 126–135 | date = January 2018 | pmid = 29282327 | pmc = 5772157 | doi = 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004826 }}</ref> Amnestic MCI has a greater than 90% likelihood of being associated with Alzheimer's.<ref name=Atri2019 /> | |||

| Since family members are often the first to notice changes that might indicate the onset of Alzheimer's they should learn the early warning signs and serve as informants during initial evaluation of patients clinically.<ref></ref> ], ] and ] often accompany the loss of memory. Alzheimer's disease (AD) may also include behavioral changes, such as outbursts of ] or excessive passivity in people who have no previous history of such behavior. | |||

| ===Early stage=== | |||

| In the later stages of the disease, deterioration of musculature and mobility, leading to bedfastness, inability to feed oneself, and ], will be seen if death from some external cause (e.g. ] or ]) does not intervene. Once identified, the average lifespan of patients living with Alzheimer's disease is approximately 7-10 years, although cases are known where reaching the final stage occurs within 4-5 years or at the other extreme they may survive up to 21 years. | |||

| In people with Alzheimer's disease, the increasing impairment of learning and memory eventually leads to a definitive diagnosis. In a small percentage, difficulties with language, executive functions, ] (]), or execution of movements (]) are more prominent than memory problems.<ref name=pmid10653284>{{cite journal | vauthors = Förstl H, Kurz A | title = Clinical features of Alzheimer's disease | journal = European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience | volume = 249 | issue = 6 | pages = 288–290 | year = 1999 | pmid = 10653284 | doi = 10.1007/s004060050101 | s2cid = 26142779 }}</ref> Alzheimer's disease does not affect all memory capacities equally. ] of the person's life (]), facts learned (]), and ] (the memory of the body on how to do things, such as using a fork to eat or how to drink from a glass) are affected to a lesser degree than new facts or memories.<ref name=pmid1300219>{{cite journal | vauthors = Carlesimo GA, Oscar-Berman M | title = Memory deficits in Alzheimer's patients: a comprehensive review | journal = Neuropsychology Review | volume = 3 | issue = 2 | pages = 119–169 | date = June 1992 | pmid = 1300219 | doi = 10.1007/BF01108841 | s2cid = 19548915 }}</ref><ref name=pmid8821346>{{cite journal | vauthors = Jelicic M, Bonebakker AE, Bonke B | title = Implicit memory performance of patients with Alzheimer's disease: a brief review | journal = International Psychogeriatrics | volume = 7 | issue = 3 | pages = 385–392 | year = 1995 | pmid = 8821346 | doi = 10.1017/S1041610295002134 | s2cid = 9419442 }}</ref> | |||

| ] are mainly characterised by a shrinking ] and decreased word ], leading to a general impoverishment of oral and ].<ref name=pmid10653284 /><ref name=pmid1856925>{{cite journal | vauthors = Taler V, Phillips NA | title = Language performance in Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment: a comparative review | journal = Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology | volume = 30 | issue = 5 | pages = 501–556 | date = July 2008 | pmid = 18569251 | doi = 10.1080/13803390701550128 | s2cid = 37153159 }}</ref> In this stage, the person with Alzheimer's is usually capable of communicating basic ideas adequately.<ref name=pmid10653284 /><ref name=pmid1856925 /><ref name=pmid7967534>{{cite journal | vauthors = Frank EM | title = Effect of Alzheimer's disease on communication function | journal = Journal of the South Carolina Medical Association | volume = 90 | issue = 9 | pages = 417–423 | date = September 1994 | pmid = 7967534 }}</ref> While performing ] such as writing, drawing, or dressing, certain movement coordination and planning difficulties (]) may be present; however, they are commonly unnoticed.<ref name=pmid10653284 /> As the disease progresses, people with Alzheimer's disease can often continue to perform many tasks independently; however, they may need assistance or supervision with the most cognitively demanding activities.<ref name=pmid10653284 /> | |||

| === Stages and symptoms === | |||

| *'''Mild''' — In the '''early stage''' of the disease, patients have a tendency to become less energetic or spontaneous, though changes in their behavior often go unnoticed even by the patients' immediate family. This stage of the disease has also been termed ] (MCI), when the patient does not meet the criteria for a diagnosis of dementia.<ref>. Ronald C Petersen, Nature Clinical Practice Neurology (2007) 3, 60-61.</ref> | |||

| *'''Moderate''' — As the disease progresses to the '''middle stage''', patients might still be able to perform tasks independently (such as using the bathroom), but may need assistance with more complicated activities (such as paying bills). | |||

| *'''Severe''' — As the disease progresses from the middle to the '''late stage''', patients will not be able to perform even simple tasks independently and will require constant supervision. They become incontinent of bladder and then incontinent of bowel. They will eventually lose the ability to walk and eat without assistance. Language becomes severely disorganized, and then is lost altogether. They may eventually lose the ability to swallow food and fluid, and this can ultimately lead to death. | |||

| == |

===Middle stage=== | ||

| Progressive deterioration eventually hinders independence, with subjects being unable to perform most common activities of daily living.<ref name=pmid10653284 /> Speech difficulties become evident due to an inability to ], which leads to frequent incorrect word substitutions (]s). Reading and writing skills are also progressively lost.<ref name=pmid10653284 /><ref name=pmid7967534 /> Complex motor sequences become less coordinated as time passes and Alzheimer's disease progresses, so the risk of falling increases.<ref name=pmid10653284 /> During this phase, memory problems worsen, and the person may fail to recognise close relatives.<ref name=pmid10653284 /> ], which was previously intact, becomes impaired.<ref name=pmid10653284 /> | |||

| Behavioral and ] changes become more prevalent. Common manifestations are ], ] and ], leading to crying, outbursts of unpremeditated ], or resistance to caregiving.<ref name=pmid10653284 /> ] can also appear.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Volicer L, Harper DG, Manning BC, Goldstein R, Satlin A | title = Sundowning and circadian rhythms in Alzheimer's disease | journal = The American Journal of Psychiatry | volume = 158 | issue = 5 | pages = 704–711 | date = May 2001 | pmid = 11329390 | doi = 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.5.704 | s2cid = 10492607 }}</ref> Approximately 30% of people with Alzheimer's disease develop ] and other ]al symptoms.<ref name=pmid10653284 /> Subjects also lose insight of their disease process and limitations (]).<ref name=pmid10653284 /> ] can develop.<ref name=pmid10653284 /> These symptoms create ] for relatives and caregivers, which can be reduced by moving the person from ] to other ].<ref name=pmid10653284 /><ref name=pmid7806732>{{cite journal | vauthors = Gold DP, Reis MF, Markiewicz D, Andres D | title = When home caregiving ends: a longitudinal study of outcomes for caregivers of relatives with dementia | journal = Journal of the American Geriatrics Society | volume = 43 | issue = 1 | pages = 10–16 | date = January 1995 | pmid = 7806732 | doi = 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb06235.x | s2cid = 29847950 }}</ref> | |||

| Alzheimer's disease (AD) is primarily a clinically ] condition based on the presence of characteristic ] and neuropsychological features and the ]. Determination of neurological characteristics is made utilizing patient history and clinical observation, while neuropsychological evaluation includes memory testing and assessment of intellectual functioning over a series of weeks or months. Supplemental physical testing, including ]s and ], is utilized to rule out other diagnoses. ], to include screening for ] and a ], can be helpful in establishing the presence and severity of ]. Although certain clues from history may suggest a diagnosis of vascular dementias instead of, or in addition to, AD (for example, see the Hachinski scale ), the ability of certain neuroimaging modalities such as ] to differentiate vascular type from Alzheimer disease types of dementias, appears to be superior to clinical exam (PMID 15545324). | |||

| ===Late stage=== | |||

| Interviews with family members and/or caregivers are also utilized in the initial assessment of the disease, as a patient with Alzheimer's may tend to minimize his or her symptoms, or may undergo evaluation at a time when his or her symptoms are less apparent, as ] fluctuations ("good days and bad days") are a common feature of the disease. Observations noting that a patient's good memory function decreases over time plays a critical role in the diagnosis of Alzheimer's. | |||

| ] | |||

| During the final stage, known as the late-stage or severe stage, there is complete dependence on caregivers.<ref name=NIA2023/><ref name=NHS2018 /><ref name=pmid10653284 /> Language is reduced to simple phrases or even single words, eventually leading to complete loss of speech.<ref name=pmid10653284 /><ref name=pmid7967534 /> Despite the loss of verbal language abilities, people can often understand and return emotional signals. Although aggressiveness can still be present, extreme ] and ] are much more common symptoms. People with Alzheimer's disease will ultimately not be able to perform even the simplest tasks independently; ] and mobility deteriorates to the point where they are bedridden and unable to feed themselves. The cause of death is usually an external factor, such as infection of ]s or ], not the disease itself.<ref name=pmid10653284 /><!-- cites previous 4 sentences --> In some cases, there is a ] immediately before death, where there is an unexpected recovery of mental clarity.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors = Mashour GA, Frank L, Batthyany A, Kolanowski AM, Nahm M, Schulman-Green D, Greyson B, Pakhomov S, Karlawish J, Shah RC |title=Paradoxical lucidity: A potential paradigm shift for the neurobiology and treatment of severe dementias |journal=Alzheimer's & Dementia |volume=15 |issue=8 |pages=1107–1114 |date=August 2019 |pmid=31229433 |doi=10.1016/j.jalz.2019.04.002 |s2cid=195063786 |hdl=2027.42/153062 |hdl-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| ==Causes== | |||

| ''']''' | |||

| Alzheimer's disease is believed to occur when abnormal amounts of ] (Aβ), accumulating extracellularly as ] and ]s, or intracellularly as ]s, form in the brain, affecting neuronal functioning and connectivity, resulting in a progressive loss of brain function.<ref>{{cite web | title=Alzheimer's disease – Causes | website=] (NHS) | date=24 April 2023 | url=https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/alzheimers-disease/causes/ | access-date=10 July 2023 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200929103158/https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/alzheimers-disease/causes/ |archive-date=29 September 2020 | url-status = live }}</ref><ref name=Tackenberg>{{cite journal | vauthors = Tackenberg C, Kulic L, Nitsch RM | title = Familial Alzheimer's disease mutations at position 22 of the amyloid β-peptide sequence differentially affect synaptic loss, tau phosphorylation and neuronal cell death in an ex vivo system | journal = PLOS ONE | volume = 15 | issue = 9 | pages = e0239584 | date = 2020 | pmid = 32966331 | pmc = 7510992 | doi = 10.1371/journal.pone.0239584 | bibcode = 2020PLoSO..1539584T | doi-access = free | title-link = doi }}</ref> This altered ] is age-related, regulated by brain cholesterol,<ref name=WangHao>{{cite journal | vauthors = Wang H, Kulas JA, Wang C, Holtzman DM, Ferris HA, Hansen SB | title = Regulation of beta-amyloid production in neurons by astrocyte-derived cholesterol | journal = Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America | volume = 118 | issue = 33 | pages = e2102191118 | date = August 2021 | pmid = 34385305 | pmc = 8379952 | doi = 10.1073/pnas.2102191118|issn=0027-8424 | s2cid = 236998499 | doi-access = free | title-link = doi | bibcode = 2021PNAS..11802191W }}</ref> and associated with other neurodegenerative diseases.<ref name=Vilchez>{{cite journal | vauthors = Vilchez D, Saez I, Dillin A | title = The role of protein clearance mechanisms in organismal ageing and age-related diseases | journal = Nature Communications | volume = 5 | issue = | pages = 5659 | date = December 2014 | pmid = 25482515 | doi = 10.1038/ncomms6659 | bibcode = 2014NatCo...5.5659V | doi-access = free | title-link = doi }}</ref><ref name=OUP>{{cite book| vauthors = Jacobson M, McCarthy N |title=Apoptosis |date=2002|publisher=Oxford University Press|location=Oxford, OX|isbn=0-19-963849-7|page=290}}</ref> | |||

| New imaging technologies have revolutionized our understanding of the structure and function of the living brain. Structural imaging provides information about the shape, position or volume of brain tissue. Structural techniques include magnetic resonance imaging (]) and computed tomography (]). Functional imaging reveals how well cells in various brain regions are working by showing how actively the cells use sugar or oxygen. Functional techniques include positron emission tomography (]) and ] (fMRI). | |||

| The cause for most Alzheimer's cases is still mostly unknown,<ref name=Breijyeh2020>{{cite journal | vauthors = Breijyeh Z, Karaman R | title = Comprehensive Review on Alzheimer's Disease: Causes and Treatment | journal = Molecules | volume = 25 | issue = 24 | date = December 2020 | page = 5789 | pmid = 33302541 | pmc = 7764106 | doi = 10.3390/molecules25245789 | type = Review | doi-access = free | title-link = doi }}</ref> except for 1–2% of cases where deterministic genetic differences have been identified.<ref name=Long /> Several competing ] attempt to explain the underlying cause; the most predominant hypothesis is the amyloid beta (Aβ) hypothesis.<ref name=Breijyeh2020 /> | |||

| No medical tests are available to diagnose Alzheimer's disease conclusively pre-]. Expert clinicians who specialize in memory disorders can now diagnose AD with an accuracy of 85 - 90%. However, a definitive diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease must await microscopic examination of brain tissue which generally occurs at ]. | |||

| The oldest hypothesis, on which most drug therapies are based, is the ], which proposes that Alzheimer's disease is caused by reduced synthesis of the neurotransmitter ].<ref name=Breijyeh2020 /> The loss of ]s noted in the ] and cerebral cortex, is a key feature in the progression of Alzheimer's.<ref name=Petersen /> The 1991 ] postulated that extracellular amyloid beta (Aβ) deposits are the fundamental cause of the disease.<ref name=pmid1763432>{{cite journal | vauthors = Hardy J, Allsop D | title = Amyloid deposition as the central event in the aetiology of Alzheimer's disease | journal = Trends in Pharmacological Sciences | volume = 12 | issue = 10 | pages = 383–388 | date = October 1991 | pmid = 1763432 | doi = 10.1016/0165-6147(91)90609-V }}</ref><ref name=pmid11801334>{{cite journal | vauthors = Mudher A, Lovestone S | title = Alzheimer's disease-do tauists and baptists finally shake hands? | journal = Trends in Neurosciences | volume = 25 | issue = 1 | pages = 22–26 | date = January 2002 | pmid = 11801334 | doi = 10.1016/S0166-2236(00)02031-2 | s2cid = 37380445 }}</ref> Support for this postulate comes from the location of the gene for the ] (APP) on ], together with the fact that people with ] (Down syndrome) who have an extra ] almost universally exhibit at least the earliest symptoms of Alzheimer's disease by 40 years of age.<ref name=Lott2019 /> A specific ] of apolipoprotein, ], is a major genetic risk factor for Alzheimer's disease.<ref name=Simon2018p111 /> While apolipoproteins enhance the breakdown of beta amyloid, some isoforms are not very effective at this task (such as APOE4), leading to excess amyloid buildup in the brain.<ref name=pmid7566000>{{cite journal | vauthors = Polvikoski T, Sulkava R, Haltia M, Kainulainen K, Vuorio A, Verkkoniemi A, Niinistö L, Halonen P, Kontula K | title = Apolipoprotein E, dementia, and cortical deposition of beta-amyloid protein | journal = The New England Journal of Medicine | volume = 333 | issue = 19 | pages = 1242–1247 | date = November 1995 | pmid = 7566000 | doi = 10.1056/NEJM199511093331902 | doi-access = free }}</ref> | |||

| ==Pathology== | |||

| {{main|Biochemistry of Alzheimer's disease}} | |||

| ===Biochemical characteristics=== | |||

| Alzheimer's disease has been identified as a ] disease, or ], due to the accumulation of abnormally folded A-beta and tau proteins in the brains of AD patients.<ref name="Hashimoto"> {{cite journal | author = Hashimoto M, Rockenstein E, Crews L, Masliah E | title = Role of protein aggregation in mitochondrial dysfunction and neurodegeneration in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases. | journal = Neuromolecular Med | volume = 4 | issue = 1-2 | pages = 21-36 | year = 2003 | id = PMID 14528050}}</ref> A-beta, also written Aβ, is a short ] that is a ] byproduct of the ] ] (APP), whose function is unclear but thought to be involved in neuronal development.<ref name="decoding darkness"> | |||

| The ]s are components of a proteolytic complex involved in APP processing and degradation.<ref name="Cai"> {{cite journal | author = Cai D, Netzer W, Zhong M, Lin Y, Du G, Frohman M, Foster D, Sisodia S, Xu H, Gorelick F, Greengard P | title = Presenilin-1 uses phospholipase D1 as a negative regulator of beta-amyloid formation. | journal = Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A | volume = 103 | issue = 6 | pages = 1941-6 | year = 2006 | id = PMID 16449386}}</ref> Although amyloid beta ]s are soluble and harmless, they undergo a dramatic ] at sufficiently high concentration to form a ]-rich ] that aggregates to form ]<ref name="Ohnishi">{{cite journal | author = Ohnishi S, Takano K | title = Amyloid fibrils from the viewpoint of protein folding. | journal = Cell Mol Life Sci | volume = 61 | issue = 5 | pages = 511-24 | year = 2004 | id = PMID 15004691}}</ref> that deposit outside neurons in dense formations known as ''senile plaques'' or ''neuritic plaques'', in less dense aggregates as ''diffuse plaques'', and sometimes in the walls of small blood vessels in the brain in a process called amyloid angiopathy or ]. | |||

| ===Genetic=== | |||

| AD is also considered a ] due to abnormal aggregation of the ], a ] expressed in neurons that normally acts to stabilize ] in the cell ]. Like most microtubule-associated proteins, tau is normally regulated by ]; however, in AD patients, hyperphosphorylated tau accumulates as paired helical filaments<ref name="Goedert">{{cite journal | author = Goedert M, Klug A, Crowther R | title = Tau protein, the paired helical filament and Alzheimer's disease. | journal = J Alzheimers Dis | volume = 9 | issue = 3 Suppl | pages = 195-207 | year = 2006 | id = PMID 16914859}}</ref> that in turn aggregate into masses inside nerve cell bodies known as ''neurofibrillary tangles'' and as dystrophic ]s associated with amyloid plaques. | |||

| ==== Late onset ==== | |||

| Late-onset Alzheimer's is about 70% ].<ref name=Andrews2023>{{cite journal |vauthors=Andrews SJ, Renton AE, Fulton-Howard B, Podlesny-Drabiniok A, Marcora E, Goate AM |date=April 2023 |title=The complex genetic architecture of Alzheimer's disease: novel insights and future directions |url= |journal=eBioMedicine |volume=90 |pages=104511 |doi=10.1016/j.ebiom.2023.104511 |pmc=10024184 |pmid=36907103}}</ref><ref name=Scheltens2021>{{cite journal |vauthors=Scheltens P, De Strooper B, Kivipelto M, Holstege H, Chételat G, Teunissen CE, Cummings J, van der Flier WM |date=April 2021 |title=Alzheimer's disease |url= |journal=Lancet |volume=397 |issue=10284 |pages=1577–1590 |doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32205-4 |pmc=8354300 |pmid=33667416}}</ref> Genetic models in 2020 predict Alzheimer's disease with 90% accuracy.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Sims R, Hill M, Williams J |date=March 2020 |title=The multiplex model of the genetics of Alzheimer's disease |url= https://orca.cardiff.ac.uk/id/eprint/129659/1/Nature%20Neuroscience.pdf|journal=Nat Neurosci |volume=23 |issue=3 |pages=311–322 |doi=10.1038/s41593-020-0599-5 |pmid=32112059|s2cid=256839971 }}</ref> Most cases of Alzheimer's are not ], and so they are termed sporadic Alzheimer's disease.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Chávez-Gutiérrez |first1=Lucía |last2=Szaruga |first2=Maria |date=2020-09-01 |title=Mechanisms of neurodegeneration — Insights from familial Alzheimer's disease |url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1084952118302969 |journal=Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology |series=Gamma Secretase |volume=105 |pages=75–85 |doi=10.1016/j.semcdb.2020.03.005 |pmid=32418657 |issn=1084-9521}}</ref> Of the cases of sporadic Alzheimer's disease, most are classified as late onset where they are developed after the age of 65 years.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Piaceri I, Nacmias B, Sorbi S |title=Genetics of familial and sporadic Alzheimer's disease |journal=Frontiers in Bioscience (Elite Edition) |volume=5 |issue=1 |pages=167–177 |date=January 2013 |pmid=23276979 |doi=10.2741/e605|doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| The strongest genetic risk factor for sporadic Alzheimer's disease is ].<ref name="NIA2021" /> APOEε4 is one of four alleles of ] (APOE). APOE plays a major role in lipid-binding proteins in lipoprotein particles and the ] allele disrupts this function.<ref name="Perea">{{cite journal |vauthors=Perea JR, Bolós M, Avila J |date=October 2020 |title=Microglia in Alzheimer's Disease in the Context of Tau Pathology |journal=Biomolecules |volume=10 |issue=10 |page=1439 |doi=10.3390/biom10101439 |pmc=7602223 |pmid=33066368 |doi-access=free |title-link=doi}}</ref> Between 40% and 80% of people with Alzheimer's disease possess at least one APOEε4 allele.<ref name="pmid16567625">{{cite journal |vauthors=Mahley RW, Weisgraber KH, Huang Y |date=April 2006 |title=Apolipoprotein E4: a causative factor and therapeutic target in neuropathology, including Alzheimer's disease |journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America |volume=103 |issue=15 |pages=5644–5651 |bibcode=2006PNAS..103.5644M |doi=10.1073/pnas.0600549103 |pmc=1414631 |pmid=16567625 |doi-access=free |title-link=doi}}</ref> The APOEε4 allele increases the risk of the disease by three times in ] and by 15 times in ].<ref name="pmid16876668">{{cite journal |vauthors=Blennow K, de Leon MJ, Zetterberg H |date=July 2006 |title=Alzheimer's disease |journal=Lancet |volume=368 |issue=9533 |pages=387–403 |doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69113-7 |pmid=16876668 |s2cid=47544338}}</ref> Like many human diseases, environmental effects and genetic modifiers result in incomplete ]. For example, Nigerian ] people do not show the relationship between dose of APOEε4 and incidence or age-of-onset for Alzheimer's disease seen in other human populations.<ref name="pmid16434658">{{cite journal |vauthors=Hall K, Murrell J, Ogunniyi A, Deeg M, Baiyewu O, Gao S, Gureje O, Dickens J, Evans R, Smith-Gamble V, Unverzagt FW, Shen J, Hendrie H |date=January 2006 |title=Cholesterol, APOE genotype, and Alzheimer disease: an epidemiologic study of Nigerian Yoruba |journal=Neurology |volume=66 |issue=2 |pages=223–227 |doi=10.1212/01.wnl.0000194507.39504.17 |pmc=2860622 |pmid=16434658}}</ref><ref name="pmid16278853">{{cite journal |vauthors=Gureje O, Ogunniyi A, Baiyewu O, Price B, Unverzagt FW, Evans RM, Smith-Gamble V, Lane KA, Gao S, Hall KS, Hendrie HC, Murrell JR |date=January 2006 |title=APOE epsilon4 is not associated with Alzheimer's disease in elderly Nigerians |journal=Annals of Neurology |volume=59 |issue=1 |pages=182–185 |doi=10.1002/ana.20694 |pmc=2855121 |pmid=16278853}}</ref> | |||

| ==== Early onset ==== | |||

| {{further|Early-onset Alzheimer's disease}} | |||

| Only 1–2% of Alzheimer's cases are ] due to ] effects, as Alzheimer's is highly polygenic. When the disease is caused by autosomal dominant variants, it is known as ], which is rarer and has a faster rate of progression.<ref name="Long">{{cite journal | vauthors = Long JM, Holtzman DM | title = Alzheimer Disease: An Update on Pathobiology and Treatment Strategies | journal = Cell | volume = 179 | issue = 2 | pages = 312–339 | date = October 2019 | pmid = 31564456 | pmc = 6778042 | doi = 10.1016/j.cell.2019.09.001 }}</ref> Less than 5% of sporadic Alzheimer's disease have an earlier onset,<ref name="Long" /> and early-onset Alzheimer's is about 90% heritable.<ref name=Andrews2023/><ref name=Scheltens2021/> Familial Alzheimer's disease usually implies two or more persons affected in one or more generations.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Schramm |first1=C. |last2=Wallon |first2=D. |last3=Nicolas |first3=G. |last4=Charbonnier |first4=C. |date=2022-05-01 |title=What contribution can genetics make to predict the risk of Alzheimer's disease? |url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0035378722005537 |journal=Revue Neurologique |series=International meeting of the French society of neurology : NeuroDegenerative Disease : What will the future bring ? |volume=178 |issue=5 |pages=414–421 |doi=10.1016/j.neurol.2022.03.005 |pmid=35491248 |issn=0035-3787}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Goldman |first1=Jill S. |last2=Van Deerlin |first2=Vivianna M. |date=2018-10-01 |title=Alzheimer's Disease and Frontotemporal Dementia: The Current State of Genetics and Genetic Testing Since the Advent of Next-Generation Sequencing |journal=Molecular Diagnosis & Therapy |language=en |volume=22 |issue=5 |pages=505–513 |doi=10.1007/s40291-018-0347-7 |issn=1179-2000 |pmc=6472481 |pmid=29971646}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Piaceri I |date=2013 |title=Genetics of familial and sporadic Alzheimer s disease |journal=Frontiers in Bioscience |volume=E5 |issue=1 |pages=167–177 |doi=10.2741/E605 |issn=1945-0494 |pmid=23276979 |doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| Early onset familial Alzheimer's disease can be attributed to mutations in one of three genes: those encoding ] (APP) and ]s ] and ].<ref name="Atri2019" /> Most mutations in the APP and presenilin genes increase the production of a small protein called ] (Aβ)42, which is the main component of ].<ref name="Selkoe">{{cite journal | vauthors = Selkoe DJ | title = Translating cell biology into therapeutic advances in Alzheimer's disease | journal = Nature | volume = 399 | issue = 6738 Suppl | pages = A23–A31 | date = June 1999 | pmid = 10392577 | doi = 10.1038/19866 | s2cid = 42287088 | doi-access = free | title-link = doi }}</ref> Some of the mutations merely alter the ratio between Aβ42 and the other major forms—particularly Aβ40—without increasing Aβ42 levels in the brain.<ref name="Borchelt">{{cite journal | vauthors = Borchelt DR, Thinakaran G, Eckman CB, Lee MK, Davenport F, Ratovitsky T, Prada CM, Kim G, Seekins S, Yager D, Slunt HH, Wang R, Seeger M, Levey AI, Gandy SE, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Price DL, Younkin SG, Sisodia SS | title = Familial Alzheimer's disease-linked presenilin 1 variants elevate Abeta1-42/1-40 ratio in vitro and in vivo | journal = Neuron | volume = 17 | issue = 5 | pages = 1005–1013 | date = November 1996 | pmid = 8938131 | doi = 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80230-5 | s2cid = 18315650 | doi-access = free | title-link = doi }}</ref> Two other genes associated with autosomal dominant Alzheimer's disease are ] and ].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Kim JH | title = Genetics of Alzheimer's Disease | journal = Dementia and Neurocognitive Disorders | volume = 17 | issue = 4 | pages = 131–136 | date = December 2018 | pmid = 30906402 | pmc = 6425887 | doi = 10.12779/dnd.2018.17.4.131 }}</ref> | |||

| ]s in the ] gene have been associated with a three to five times higher risk of developing Alzheimer's disease.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Carmona S, Zahs K, Wu E, Dakin K, Bras J, Guerreiro R |title=The role of TREM2 in Alzheimer's disease and other neurodegenerative disorders |journal=Lancet Neurol |volume=17 |issue=8 |pages=721–730 |date=August 2018 |pmid=30033062 |doi=10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30232-1 |s2cid=51706988 |url=https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10056337/ |access-date=21 February 2022 |archive-date=27 March 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220327190158/https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10056337/ |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| A Japanese pedigree of familial Alzheimer's disease was found to be associated with a deletion mutation of codon 693 of APP.<ref name=Tomiyama2010>{{cite journal | vauthors = Tomiyama T | title = | journal = Brain and Nerve = Shinkei Kenkyu No Shinpo | volume = 62 | issue = 7 | pages = 691–699 | date = July 2010 | pmid = 20675873 }}</ref> This mutation and its association with Alzheimer's disease was first reported in 2008,<ref name=Tomiyama2008>{{cite journal | vauthors = Tomiyama T, Nagata T, Shimada H, Teraoka R, Fukushima A, Kanemitsu H, Takuma H, Kuwano R, Imagawa M, Ataka S, Wada Y, Yoshioka E, Nishizaki T, Watanabe Y, Mori H | title = A new amyloid beta variant favoring oligomerization in Alzheimer's-type dementia | journal = Annals of Neurology | volume = 63 | issue = 3 | pages = 377–387 | date = March 2008 | pmid = 18300294 | doi = 10.1002/ana.21321 | s2cid = 42311988 }}</ref> and is known as the Osaka mutation. Only homozygotes with this mutation have an increased risk of developing Alzheimer's disease. This mutation accelerates Aβ oligomerization but the proteins do not form the amyloid fibrils that aggregate into amyloid plaques, suggesting that it is the Aβ oligomerization rather than the fibrils that may be the cause of this disease. Mice expressing this mutation have all the usual pathologies of Alzheimer's disease.<ref name=Tomiyama>{{cite journal | vauthors = Tomiyama T, Shimada H | title = APP Osaka Mutation in Familial Alzheimer's Disease-Its Discovery, Phenotypes, and Mechanism of Recessive Inheritance | journal = International Journal of Molecular Sciences | volume = 21 | issue = 4 | page = 1413 | date = February 2020 | pmid = 32093100 | pmc = 7073033 | doi = 10.3390/ijms21041413 | doi-access = free | title-link = doi }}</ref> | |||

| ===Hypotheses=== | |||

| ==== Amyloid beta and tau protein ==== | |||

| ] | |||

| The ] proposes that ] abnormalities initiate the disease cascade.<ref name=tzi/> In this model, ] tau begins to pair with other threads of tau as ]s. Eventually, they form ]s inside neurons.<ref name="tzi">{{cite journal |vauthors=Tzioras M, Davies C, Newman A, Jackson R, Spires-Jones T |title=Invited Review: APOE at the interface of inflammation, neurodegeneration and pathological protein spread in Alzheimer's disease |journal=Neuropathology and Applied Neurobiology |volume=45 |issue=4 |pages=327–346 |date=June 2019 |pmid=30394574 |pmc=6563457 |doi=10.1111/nan.12529}}</ref> When this occurs, the ]s disintegrate, destroying the structure of the cell's ] which collapses the neuron's transport system.<ref name=tzi/> | |||

| A number of studies connect the misfolded amyloid beta and tau proteins associated with the pathology of Alzheimer's disease, as bringing about ] that leads to ].<ref name=Sinyor>{{cite journal | vauthors = Sinyor B, Mineo J, Ochner C | title = Alzheimer's Disease, Inflammation, and the Role of Antioxidants | journal = Journal of Alzheimer's Disease Reports | volume = 4 | issue = 1 | pages = 175–183 | date = June 2020 | pmid = 32715278 | pmc = 7369138 | doi = 10.3233/ADR-200171 }}</ref> This chronic inflammation is also a feature of other neurodegenerative diseases including ], and ].<ref name=Kinney>{{cite journal | vauthors = Kinney JW, Bemiller SM, Murtishaw AS, Leisgang AM, Salazar AM, Lamb BT | title = Inflammation as a central mechanism in Alzheimer's disease | journal = Alzheimer's & Dementia | volume = 4 | issue = | pages = 575–590 | date = 2018 | pmid = 30406177 | pmc = 6214864 | doi = 10.1016/j.trci.2018.06.014 }}</ref> ]s have also been linked to dementia.<ref name=Breijyeh2020 /> ] accumulate in Alzheimer's diseased brains; ] may be the major source of this DNA damage.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Lin X, Kapoor A, Gu Y, Chow MJ, Peng J, Zhao K, Tang D |title=Contributions of DNA Damage to Alzheimer's Disease |journal=Int J Mol Sci |volume=21 |issue=5 |date=February 2020 |page=1666 |pmid=32121304 |pmc=7084447 |doi=10.3390/ijms21051666 |doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| ==== Sleep ==== | |||

| ]s are seen as a possible ] for inflammation in Alzheimer's disease.<ref name="Irwin">{{cite journal | vauthors = Irwin MR, Vitiello MV | title = Implications of sleep disturbance and inflammation for Alzheimer's disease dementia | journal = The Lancet. Neurology | volume = 18 | issue = 3 | pages = 296–306 | date = March 2019 | pmid = 30661858 | doi = 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30450-2 | s2cid = 58546748 }}</ref> Sleep disruption was previously only seen as a consequence of Alzheimer's disease, but {{As of|2020|lc=y}}, accumulating evidence suggests that this relationship may be ].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Lloret MA, Cervera-Ferri A, Nepomuceno M, Monllor P, Esteve D, Lloret A | title = Is Sleep Disruption a Cause or Consequence of Alzheimer's Disease? Reviewing Its Possible Role as a Biomarker | journal = International Journal of Molecular Sciences | volume = 21 | issue = 3 | pages = 1168 | date = February 2020 | pmid = 32050587 | pmc = 7037733 | doi = 10.3390/ijms21031168 | doi-access = free }}</ref> | |||

| ==== Metal toxicity, smoking, neuroinflammation and air pollution ==== | |||

| The cellular ] of ] such as ionic copper, iron, and zinc is disrupted in Alzheimer's disease, though it remains unclear whether this is produced by or causes the changes in proteins.<ref name=Breijyeh2020 /><ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Huat TJ, Camats-Perna J, Newcombe EA, Valmas N, Kitazawa M, Medeiros R |title=Metal Toxicity Links to Alzheimer's Disease and Neuroinflammation |journal=J Mol Biol |volume=431 |issue=9 |pages=1843–1868 |date=April 2019 |pmid=30664867 |pmc=6475603 |doi=10.1016/j.jmb.2019.01.018 }}</ref> Smoking is a significant Alzheimer's disease risk factor.<ref name=Knopman2021>{{cite journal |vauthors = Knopman DS, Amieva H, Petersen RC, Chételat G, Holtzman DM, Hyman BT, Nixon RA, Jones DT |title=Alzheimer disease |journal=Nature Reviews Disease Primers |volume=7 |issue=1 |pages=33 |date=May 2021 |pmid=33986301 |pmc=8574196 |doi=10.1038/s41572-021-00269-y }}</ref> ] of the ] are risk factors for late-onset Alzheimer's disease.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Eikelenboom P, van Exel E, Hoozemans JJ, Veerhuis R, Rozemuller AJ, van Gool WA | title = Neuroinflammation – an early event in both the history and pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease | journal = Neuro-Degenerative Diseases | volume = 7 | issue = 1–3 | pages = 38–41 | year = 2010 | pmid = 20160456 | doi = 10.1159/000283480 | s2cid = 40048333 }}</ref> ] may be a contributing factor to the development of Alzheimer's disease.<ref name=Breijyeh2020 /> | |||

| ==== Age-related myelin decline ==== | |||

| Retrogenesis is a medical ] that just as the fetus goes through a process of ] beginning with ] and ending with ], the brains of people with Alzheimer's disease go through a reverse ] process starting with ] and death of axons (white matter) and ending with the death of grey matter.<ref name="Laks2015">{{cite journal |vauthors=Alves GS, Oertel Knöchel V, Knöchel C, Carvalho AF, Pantel J, Engelhardt E, Laks J |date=2015 |title=Integrating retrogenesis theory to Alzheimer's disease pathology: insight from DTI-TBSS investigation of the white matter microstructural integrity |journal=BioMed Research International |volume=2015 |pages=291658 |doi=10.1155/2015/291658 |pmc=4320890 |pmid=25685779 |doi-access=free |title-link=doi}}</ref> Likewise the hypothesis is, that as infants go through states of ], people with Alzheimer's disease go through the reverse process of progressive ].<ref name="Kluger1999">{{cite journal |vauthors=Reisberg B, Franssen EH, Hasan SM, Monteiro I, Boksay I, Souren LE, Kenowsky S, Auer SR, Elahi S, Kluger A |date=1999 |title=Retrogenesis: clinical, physiologic, and pathologic mechanisms in brain aging, Alzheimer's and other dementing processes |journal=European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience |volume=249 |issue=3 |pages=28–36 |doi=10.1007/pl00014170 |pmid=10654097 |s2cid=23410069}}</ref> | |||

| According to one theory, dysfunction of ] and their associated ] during aging contributes to ] damage, which in turn generates in amyloid production and tau ].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Bartzokis G | title = Alzheimer's disease as homeostatic responses to age-related myelin breakdown | journal = Neurobiology of Aging | volume = 32 | issue = 8 | pages = 1341–1371 | date = August 2011 | pmid = 19775776 | pmc = 3128664 | doi = 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.08.007 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Cai Z, Xiao M | title = Oligodendrocytes and Alzheimer's disease | journal = The International Journal of Neuroscience | volume = 126 | issue = 2 | pages = 97–104 | date = 2016 | pmid = 26000818 | doi = 10.3109/00207454.2015.1025778 | s2cid = 21448714 }}</ref> An '']'' study employing genetic mouse models to simulate myelin dysfunction and ] further reveal that age-related myelin degradation increases sites of Aβ production and distracts ] from Aβ plaques, with both mechanisms dually exacerbating amyloidosis.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Depp C, Sun T, Sasmita AO, Spieth L, Berghoff SA, Nazarenko T, Overhoff K, Steixner-Kumar AA, Subramanian S, Arinrad S, Ruhwedel T, Möbius W, Göbbels S, Saher G, Werner HB, Damkou A, Zampar S, Wirths O, Thalmann M, Simons M, Saito T, Saido T, Krueger-Burg D, Kawaguchi R, Willem M, Haass C, Geschwind D, Ehrenreich H, Stassart R, Nave KA | title = Myelin dysfunction drives amyloid-β deposition in models of Alzheimer's disease | journal = Nature | volume = 618 | issue = 7964 | pages = 349–357 | date = June 2023 | pmid = 37258678 | pmc = 10247380 | doi = 10.1038/s41586-023-06120-6 | bibcode = 2023Natur.618..349D }}</ref> Additionally, ] between the demyelinating disease, ], and Alzheimer's disease have been reported.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Luczynski P, Laule C, Hsiung GR, Moore GR, Tremlett H | title = Coexistence of Multiple Sclerosis and Alzheimer's disease: A review | journal = Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders | volume = 27 | pages = 232–238 | date = January 2019 | pmid = 30415025 | doi = 10.1016/j.msard.2018.10.109 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Londoño DP, Arumaithurai K, Constantopoulos E, Basso MR, Reichard RR, Flanagan EP, Keegan BM | title = Diagnosis of coexistent neurodegenerative dementias in multiple sclerosis | journal = Brain Communications | volume = 4 | issue = 4 | pages = fcac167 | date = 2022-07-04 | pmid = 35822102 | pmc = 9272064 | doi = 10.1093/braincomms/fcac167 }}</ref> | |||

| ==== Other hypotheses ==== | |||

| {{Anchor|Retrogenesis}} | |||

| {{See also|Cell cycle hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease|Ion channel hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease}}The association with ] is unclear, with a 2019 study finding no increase in dementia overall in those with celiac disease while a 2018 review found an association with several types of dementia including Alzheimer's disease.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Zis P, Hadjivassiliou M | title = Treatment of Neurological Manifestations of Gluten Sensitivity and Coeliac Disease | journal = Current Treatment Options in Neurology | volume = 21 | issue = 3 | pages = 10 | date = February 2019 | pmid = 30806821 | doi = 10.1007/s11940-019-0552-7 | s2cid = 73466457 | doi-access = free | title-link = doi }}</ref><ref name=MakhloufMesselmani2018>{{cite journal | vauthors = Makhlouf S, Messelmani M, Zaouali J, Mrissa R | title = Cognitive impairment in celiac disease and non-celiac gluten sensitivity: review of literature on the main cognitive impairments, the imaging and the effect of gluten free diet | journal = Acta Neurologica Belgica | volume = 118 | issue = 1 | pages = 21–27 | date = March 2018 | pmid = 29247390 | doi = 10.1007/s13760-017-0870-z | type = Review | s2cid = 3943047 }}</ref> | |||

| Studies have shown a potential link between infection with certain viruses and developing Alzheimer's disease later in life.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Zhou L, Miranda-Saksena M, Saksena NK | title = Viruses and neurodegeneration | journal = Virology Journal | volume = 10 | issue = 1 | pages = 172 | date = May 2013 | pmid = 23724961 | pmc = 3679988 | doi = 10.1186/1743-422X-10-172 | doi-access = free }}</ref> Notably, a large scale study conducted on 6,245,282 patients has shown an increased risk of developing ] in cognitively normal individuals over 65.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Gonzalez-Fernandez E, Huang J | title = Cognitive Aspects of COVID-19 | journal = Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports | volume = 23 | issue = 9 | pages = 531–538 | date = September 2023 | pmid = 37490194 | doi = 10.1007/s11910-023-01286-y | s2cid = 260132167 }}</ref> | |||

| == Pathophysiology == | |||

| ] images of Alzheimer's disease, in the ], showing an amyloid plaque (top right), neurofibrillary tangles (bottom left), and ] (bottom center)]] | |||

| ===Neuropathology=== | ===Neuropathology=== | ||

| Both amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles are clearly visible by ] in AD brains.<ref name="Tiraboschi">{{cite journal | author = Tiraboschi P, Hansen L, Thal L, Corey-Bloom J | title = The importance of neuritic plaques and tangles to the development and evolution of AD. | journal = Neurology | volume = 62 | issue = 11 | pages = 1984-9 | year = 2004 | id = PMID 15184601}}</ref> At an anatomical level, AD is characterized by gross diffuse atrophy of the brain and loss of neurons, neuronal processes and synapses in the ] and certain subcortical regions. This results in gross ] of the affected regions, including degeneration in the ] and ], and parts of the ] and ].<ref name="Wenk">{{cite journal | author = Wenk G | title = Neuropathologic changes in Alzheimer's disease. | journal = J Clin Psychiatry | volume = 64 Suppl 9 | issue = | pages = 7-10 | year = | id = PMID 12934968}}</ref> Levels of the neurotransmitter ] are reduced. Levels of the neurotransmitters ], ], and ] are also often reduced. ] levels are usually elevated.<ref> | |||

| Alzheimer's disease is characterised by loss of ]s and ]s in the ] and certain subcortical regions. This loss results in gross ] of the affected regions, including degeneration in the ] and ], and parts of the ] and ].<ref name=pmid12934968>{{cite journal | vauthors = Wenk GL | title = Neuropathologic changes in Alzheimer's disease | journal = The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry | volume = 64 | issue = Suppl 9 | pages = 7–10 | year = 2003 | pmid = 12934968 }}</ref> Degeneration is also present in ] nuclei particularly the ] in the ].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Braak H, Del Tredici K | title = Where, when, and in what form does sporadic Alzheimer's disease begin? | journal = Current Opinion in Neurology | volume = 25 | issue = 6 | pages = 708–714 | date = December 2012 | pmid = 23160422 | doi = 10.1097/WCO.0b013e32835a3432 }}</ref> Studies using ] and ] have documented reductions in the size of specific brain regions in people with Alzheimer's disease as they progressed from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer's disease, and in comparison with similar images from healthy older adults.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Desikan RS, Cabral HJ, Hess CP, Dillon WP, Glastonbury CM, Weiner MW, Schmansky NJ, Greve DN, Salat DH, Buckner RL, Fischl B | title = Automated MRI measures identify individuals with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease | journal = Brain | volume = 132 | issue = Pt 8 | pages = 2048–2057 | date = August 2009 | pmid = 19460794 | pmc = 2714061 | doi = 10.1093/brain/awp123 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Moan R |title=MRI Software Accurately IDs Preclinical Alzheimer's Disease |journal=Diagnostic Imaging |date=July 2009 |url=https://www.diagnosticimaging.com/view/mri-software-accurately-ids-preclinical-alzheimers-disease |access-date=21 February 2022 |archive-date=21 February 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220221050502/https://www.diagnosticimaging.com/view/mri-software-accurately-ids-preclinical-alzheimers-disease |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| {{cite web | |||

| | last = Baskys | |||

| Both ] ] and ]s are clearly visible by ] in brains of those with Alzheimer's disease,<ref name=pmid15184601>{{cite journal | vauthors = Tiraboschi P, Hansen LA, Thal LJ, Corey-Bloom J | title = The importance of neuritic plaques and tangles to the development and evolution of AD | journal = Neurology | volume = 62 | issue = 11 | pages = 1984–1989 | date = June 2004 | pmid = 15184601 | doi = 10.1212/01.WNL.0000129697.01779.0A | s2cid = 25017332 }}</ref> especially in the ].<ref name=DeTureDickson2019>{{cite journal | vauthors = DeTure MA, Dickson DW | title = The neuropathological diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease | journal = Molecular Neurodegeneration | volume = 14 | issue = 1 | pages = 32 | date = August 2019 | pmid = 31375134 | pmc = 6679484 | doi = 10.1186/s13024-019-0333-5 | doi-access = free }}</ref> However, Alzheimer's disease may occur without neurofibrillary tangles in the ].<ref name=pmid15079014>{{cite journal | vauthors = Tiraboschi P, Sabbagh MN, Hansen LA, Salmon DP, Merdes A, Gamst A, Masliah E, Alford M, Thal LJ, Corey-Bloom J | title = Alzheimer disease without neocortical neurofibrillary tangles: "a second look" | journal = Neurology | volume = 62 | issue = 7 | pages = 1141–1147 | date = April 2004 | pmid = 15079014 | doi = 10.1212/01.wnl.0000118212.41542.e7 | s2cid = 22832110 }}</ref> Plaques are dense, mostly ] deposits of ] peptide and ] material outside and around ]. Neurofibrillary tangles are aggregates of the microtubule-associated protein tau which has become hyperphosphorylated and accumulate inside the cells themselves. Although many older individuals develop some plaques and tangles as a consequence of aging, the brains of people with Alzheimer's disease have a greater number of them in specific brain regions such as the ].<ref name=pmid8038565>{{cite journal | vauthors = Bouras C, Hof PR, Giannakopoulos P, Michel JP, Morrison JH | title = Regional distribution of neurofibrillary tangles and senile plaques in the cerebral cortex of elderly patients: a quantitative evaluation of a one-year autopsy population from a geriatric hospital | journal = Cerebral Cortex | volume = 4 | issue = 2 | pages = 138–150 | year = 1994 | pmid = 8038565 | doi = 10.1093/cercor/4.2.138 }}</ref> ] are not rare in the brains of people with Alzheimer's disease.<ref name=pmid11816795>{{cite journal | vauthors = Kotzbauer PT, Trojanowsk JQ, Lee VM | title = Lewy body pathology in Alzheimer's disease | journal = Journal of Molecular Neuroscience | volume = 17 | issue = 2 | pages = 225–232 | date = October 2001 | pmid = 11816795 | doi = 10.1385/JMN:17:2:225 | s2cid = 44407971 }}</ref> | |||

| | first = | |||

| | title = Receptor found that could lead to better treatments for stroke, alzheimer's disease | |||

| ===Biochemistry=== | |||

| | publisher = UCI Medical Center | |||

| {{Main|Biochemistry of Alzheimer's disease}} | |||

| | url = http://www.ucihealth.com/News/Releases/Receptor_found_treat_stroke_alzheimers_9-13-00.htm | |||

| | accessdate = 2006-11-04 }} | |||

| ==== Amyloid beta ==== | |||

| </ref> | |||

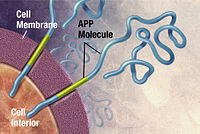

| {{Multiple image|footer=Enzymes act on the amyloid-beta precursor protein and cut it into fragments. The beta-amyloid fragment is crucial in the formation of amyloid plaques in Alzheimer's disease.|image1=Amyloid 01big1.jpg|image2=Amyloid 02big1.jpg|image3=Amyloid 03big1.jpg}} | |||

| Alzheimer's disease has been identified as a ], a ], caused by the accumulation of abnormally folded ] protein into amyloid plaques, and ] into neurofibrillary tangles in the brain.<ref name=tzi/> Plaques are made up of small ]s, 39–43 ]s in length, called amyloid beta. Amyloid beta is a fragment from the larger ] (APP) a ] that penetrates the ]. APP is critical to neuron growth, survival, and post-injury repair.<ref name=tzi/> In Alzheimer's disease, ] and ] act together in a ] process which causes APP to be divided into smaller fragments.<ref name=tzi/> Although commonly researched as neuronal proteins, APP and its processing enzymes are abundantly expressed by other brain cells. One of these fragments gives rise to ] of amyloid beta, which then form clumps that deposit outside neurons in dense formations known as amyloid plaques.<ref name=tzi/> Excitatory neurons are known to be the major producers of amyloid beta that contribute to major extracellular plaque deposition.<ref name=tzi/> | |||

| ==== Phosphorylated tau ==== | |||

| Alzheimer's disease is also considered a ] due to abnormal aggregation of the ]. Every neuron has a ], an internal support structure partly made up of structures called ]. These microtubules act like tracks, guiding nutrients and molecules from the body of the cell to the ends of the ] and back. A protein called ''tau'' stabilises the microtubules when ], and is therefore called a ]. In Alzheimer's disease, tau undergoes chemical changes, becoming hyperphosphorylated; it then begins to pair with other threads, creating neurofibrillary tangles and disintegrating the neuron's transport system.<ref name="pmid17604998">{{cite journal | vauthors = Hernández F, Avila J | title = Tauopathies | journal = Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences | volume = 64 | issue = 17 | pages = 2219–2233 | date = September 2007 | pmid = 17604998 | doi = 10.1007/s00018-007-7220-x | s2cid = 261121643 | pmc = 11136052 }}</ref> Pathogenic tau can also cause neuronal death through ] dysregulation.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Sun W, Samimi H, Gamez M, Zare H, Frost B | title = Pathogenic tau-induced piRNA depletion promotes neuronal death through transposable element dysregulation in neurodegenerative tauopathies | journal = Nature Neuroscience | volume = 21 | issue = 8 | pages = 1038–1048 | date = August 2018 | pmid = 30038280 | pmc = 6095477 | doi = 10.1038/s41593-018-0194-1 }}</ref> ] has also been reported as a mechanism of cell death in brain cells affected with tau tangles.<ref>Balusu S, Horré K, Thrupp N, Craessaerts K, Snellinx A, Serneels L, T'Syen D, Chrysidou I, Arranz AM, Sierksma A, Simrén J, Karikari TK, Zetterberg H, Chen WT, Thal DR, Salta E, Fiers M, De Strooper B. MEG3 activates necroptosis in human neuron xenografts modeling Alzheimer's disease. ''Science''. 2023 Sep 15;381(6663):1176-1182. {{doi|10.1126/science.abp9556}} {{PMID|37708272}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |date=2023-09-15 |title=Scientists discover how brain cells die in Alzheimer's |language=en-GB |work=BBC News |url=https://www.bbc.com/news/health-66816268 |access-date=2023-09-27}}</ref> | |||

| ===Disease mechanism=== | ===Disease mechanism=== | ||

| Exactly how disturbances of production and aggregation of the beta-amyloid ] give rise to the pathology of Alzheimer's disease is not known.<ref name=pmid17622778>{{cite journal | vauthors = Van Broeck B, Van Broeckhoven C, Kumar-Singh S | title = Current insights into molecular mechanisms of Alzheimer disease and their implications for therapeutic approaches | journal = Neuro-Degenerative Diseases | volume = 4 | issue = 5 | pages = 349–365 | year = 2007 | pmid = 17622778 | doi = 10.1159/000105156 | s2cid = 7949658 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Huang Y, Mucke L | title = Alzheimer mechanisms and therapeutic strategies | journal = Cell | volume = 148 | issue = 6 | pages = 1204–1222 | date = March 2012 | pmid = 22424230 | pmc = 3319071 | doi = 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.040 }}</ref> The amyloid hypothesis traditionally points to the accumulation of beta-amyloid peptides as the central event triggering neuron degeneration. Accumulation of aggregated ]s, which are believed to be the toxic form of the protein responsible for disrupting the cell's ] ion ], induces ] (]).<ref name=pmid2218531>{{cite journal | vauthors = Yankner BA, Duffy LK, Kirschner DA | title = Neurotrophic and neurotoxic effects of amyloid beta protein: reversal by tachykinin neuropeptides | journal = Science | volume = 250 | issue = 4978 | pages = 279–282 | date = October 1990 | pmid = 2218531 | doi = 10.1126/science.2218531 | bibcode = 1990Sci...250..279Y }}</ref> It is also known that A<sub>β</sub> selectively builds up in the ] in the cells of Alzheimer's-affected brains, and it also inhibits certain ] functions and the utilisation of ] by neurons.<ref name=pmid17424907>{{cite journal | vauthors = Chen X, Yan SD | title = Mitochondrial Abeta: a potential cause of metabolic dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease | journal = IUBMB Life | volume = 58 | issue = 12 | pages = 686–694 | date = December 2006 | pmid = 17424907 | doi = 10.1080/15216540601047767 | s2cid = 85423830 }}</ref> | |||

| Three major competing hypotheses exist to explain the cause of the disease. The oldest, on which most currently available drug therapies are based, is known as the "] hypothesis" and suggests that AD is due to reduced biosynthesis of the ] ]. The medications that treat acetylcholine deficiency have served to only treat symptoms of the disease and have neither halted nor reversed it.<ref name="Rosen">{{cite journal | author = Walker LC, Rosen RF | title = Alzheimer therapeutics: What after the cholinesterase inhibitors? | journal = Age Ageing | volume = 35 | pages = 332-335 | year = 2006 | id = PMID 16644763}}</ref> The cholinergic hypothesis has not maintained widespread support in the face of this evidence, although cholingeric effects have been proposed to initiate large-scale aggregation<ref name="Shen">{{cite journal | author = Shen Z | title = Brain cholinesterases: II. The molecular and cellular basis of Alzheimer's disease. | journal = Med Hypotheses | volume = 63 | issue = 2 | pages = 308-21 | year = 2004 | id = PMID 15236795}} </ref> leading to generalized neuroinflammation.<ref name="Wenk" /> | |||

| Iron dyshomeostasis is linked to disease progression, an iron-dependent form of regulated cell death called ] could be involved. Products of ] are also elevated in AD brain compared with controls.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Ryan SK, Ugalde CL, Rolland AS, Skidmore J, Devos D, Hammond TR | title = Therapeutic inhibition of ferroptosis in neurodegenerative disease | journal = Trends in Pharmacological Sciences | volume = 44 | issue = 10 | pages = 674–688 | date = October 2023 | pmid = 37657967 | doi = 10.1016/j.tips.2023.07.007 | doi-access = free }}</ref> | |||