| Revision as of 15:08, 19 October 2007 view sourceNishkid64 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users51,999 editsm Protected Ezhava: Full protection: Dispute. ← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 20:54, 31 October 2024 view source DelphiLore (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users789 edits →OriginTags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Hindu community of Kerala, India}} | |||

| {{Copyedit|date=September 2007}} | |||

| {{pp-protected|reason=Long term and persistent ]. See protection log. This has been going on for years.; requested at ]|small=yes}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=April 2020}} | |||

| {{use Indian English|date=December 2017}} | |||

| {{Infobox ethnic group | |||

| |group= '''Ezhava''' | |||

| | image = Ezhava Temple.png | |||

| | image_caption = An ancient Ezhava temple in 19th Century near Trivandrum. | |||

| |regions = ] | |||

| | region2 = | |||

| | pop = Approx. 8,000,000 (2018)<ref name="ecostat.kerala.gov.in"> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220511142922/http://www.ecostat.kerala.gov.in/images/pdf/publications/Vital_Statistics/data/vital_statistics_2018.pdf |date=11 May 2022 }}</ref> | |||

| | total_ref = <ref name="ecostat.kerala.gov.in"/> | |||

| | langs = ] | |||

| | rels = ] | |||

| | related_groups = ], ] | |||

| {{fact|date=August 2024}}}} | |||

| The '''Ezhavas,''' also known as ''Thiyya'' or ''Tiyyar'' in the ],<ref>{{cite book |title=Society in India: Continuity and change |first=David Goodman |last=Mandelbaum |author-link=David G. Mandelbaum |publisher=University of California Press |year=1970 |isbn=9780520016231 |page= |quote=Another strong caste association, but one formed at a different social level and cemented by religious appeal, is that of the Iravas of Kerala, who are also known as Ezhavas or Tiyyas and make up more than 40 per cent of Kerala Hindus |url=https://archive.org/details/societyinindia01mand/page/502 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |title=Matrilineal Kinship |editor1-first=David Murray |editor1-last=Schneider |editor2-first=E. Kathleen |editor2-last=Gough |chapter=Tiyyar: North Kerala |first=E. Kathleen |last=Gough |author-link=Kathleen Gough |page=405 |year=1961 |publisher=University of California Press |isbn=978-0-520-02529-5 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=lfdvTbfilYAC&pg=PA312 |quote=Throughout Kerala the Tiyyars (called Iravas in parts of Cochin and Travancore) ... }}</ref> are a community with origins in the region of India presently known as ], where in the 2010s they constituted about 23% of the population and were reported to be the largest ] community.<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.indiatoday.in/india/south/story/caste-based-organisations-nss-sndp-form-hindu-grand-alliance-in-kerala-115305-2012-09-05|title=Caste-based organisations NSS, SNDP form Hindu Grand Alliance in Kerala|first=M. G. |last=Radhakrishnan|date= 5 September 2012|work=India Today}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.firstpost.com/politics/guess-whos-after-the-hindu-vote-in-kerala-hint-its-not-the-bjp-2619712.html|title=Guess who's after the Hindu vote in Kerala? (Hint: It's not BJP)|work=Firstpost}}</ref> The Malabar Ezhava<ref name="Smith1976pp31-32">] pp. 31–32</ref> group has claimed a higher rank in the ] than the other Ezhava groups but was considered to be of a similar rank by ] and subsequent administrations.<ref name="Nossiter1982p30">] p. 30</ref><ref name="Kodoth2001p350">{{cite journal |title=Courting Legitimacy or Delegitimizing Custom? Sexuality, Sambandham and Marriage Reform in Late Nineteenth-Century Malabar |first=Praveena |last=Kodoth |journal=Modern Asian Studies |volume=35 |issue=2 |date=May 2001 |page=350 |jstor=313121 |doi=10.1017/s0026749x01002037 |pmid=18481401 |s2cid=7910533 | issn=0026-749X}}</ref> | |||

| The '''Ezhavas''' form a major progressive community, which is also one of the largest in ], a south ]n state. They have made a mark in the economic and political panorama of the state and have contributed enormously to the literature and culture of the state. They are also found amongst the ] diaspora around the world. They are a social group sharing a common history from the pre-social reform era, when caste was an integral part of the political, economic, legal, and social order across the ] State. | |||

| Ezhava dynasties such as the ] existed in Kerala.<ref name="Smith1976pp31-32"/> | |||

| Folklore and written records show that Ezhavas were a martial class.<ref name = "ezh1">Bardwell L. Smith, Religion and Social Conflict in South Asia. (BRILL publications, 1976,ISBN 9004045104), Page 27</ref><ref name="ezh1a">{{cite web|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=07Y3AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA27&lpg=PA27&dq=izhava+kerala&source=web&ots=zFl70XFRFi&sig=FhdgryHrCKak2z2bK3yvQl8IjJk#PPA27,M1|title= Religion and Social Conflict in South Asia. Page 27|work=Bardwell L. Smith|publisher=(BRILL publications ,1976|accessdate=Aug 17, 2007}}</ref><ref name = "ezh2">Bardwell L. Smith, Vadakkan and Thekkan Pattukal. (Sri Rama Vilasom Press, 1967), Page 128 - 148</ref><ref name = "ezh3">Nagam Aiya, Travancore State Manual by Nagam Aiya</ref> The folk songs, ''Vadakkan Pattukal'', composed about 400 hundred years ago, are full of descriptions of the military exploits of Ezhava heroes. Ezhavas served in the armed forces of all important kings of the region, such as ]s of ], and the Kings of ] and ]. Many from community became ''Kottaram Vaidyan''(Palace Physician) of important kings in the region.<ref name = "ezh1">Bardwell L. Smith, Religion and Social Conflict in South Asia. (BRILL publications, 1976,ISBN 9004045104), Page 27</ref><ref name="ezh1a">{{cite web|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=07Y3AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA27&lpg=PA27&dq=izhava+kerala&source=web&ots=zFl70XFRFi&sig=FhdgryHrCKak2z2bK3yvQl8IjJk#PPA27,M1|title= Religion and Social Conflict in South Asia. Page 27|work=Bardwell L. Smith|publisher=(BRILL publications ,1976|accessdate=Aug 17, 2007}}</ref><ref name = "ezh2">Bardwell L. Smith, Vadakkan and Thekkan Pattukal. (Sri Rama Vilasom Press, 1967), Page 128 - 148</ref><ref name = "ezh3">Nagam Aiya, Travancore State Manual by Nagam Aiya</ref> They enjoyed better status before the arrival of the ] from north. Historically, they never found a place in the four-tier caste system of ]ism. They were engaged in many professions, and many were warriors, ayurvedic physicians, astrologers, arrack brewers, traders, roddy Tappers, spiritualists, traditional toxicologists, devil worshipers and dancers, sorcerers, farmers, and weavers. The Ezhavas are also known as ''Thiyya''s or ''Billava''s in some of part of ] especially ] areas. | |||

| ==Variations== | |||

| ] <!-- Image with unknown copyright status removed: ] --> | |||

| ] | |||

| They are also known as ''Ilhava'', ''Irava'', ''Izhava'' and ''Erava'' in the south of the region; as ''Chovas'', ''Chokons'' and ''Chogons'' in ]; and as ''Thiyyar'', ''Tiyyas'' and ''Theeyas'' in the ].<ref name="Nossiter1982p30" /><ref>{{cite book |title=Society in India: Continuity and change |first=David Goodman |last=Mandelbaum |author-link=David G. Mandelbaum |publisher=University of California Press |year=1970 |isbn=9780520016231 |page= |quote=Another strong caste association, but one formed at a different social level and cemented by religious appeal, is that of the Iravas of Kerala, who are also known as Ezhavas or Tiyyas and make up more than 40 per cent of Kerala Hindus |url=https://archive.org/details/societyinindia01mand/page/502 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |title=Matrilineal Kinship |editor1-first=David Murray |editor1-last=Schneider |editor2-first=E. Kathleen |editor2-last=Gough |chapter=Tiyyar: North Kerala |first=E. Kathleen |last=Gough |author-link=Kathleen Gough |page=405 |year=1961 |publisher=University of California Press |isbn=978-0-520-02529-5 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=lfdvTbfilYAC&pg=PA312 |quote=Throughout Kerala the Tiyyars (called Iravas in parts of Cochin and Travancore) ... }}</ref> Some are also known as ''Thandan'', which has caused administrative difficulties due to the presence of a distinct caste of ] in the same region.<ref name="stdg">{{cite web |url=http://164.100.24.208/ls/CommitteeR/Social/20threport.pdf |title=Standing Committee on Social Justice and Empowerment (2006-2007) |page=13}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| ==History== | |||

| ] | |||

| ===Origin=== | |||

| ===Inscriptions=== | |||

| ] | |||

| The earliest use of the word Eelam | |||

| or Ezham is found in a ] inscription as well as in the ]. The ] inscription found near ] in ] and dated on palaeographical grounds to the 1st century BCE, refers to a person as a householder from Eelam (''Eela-kudumpikan'').<ref name=":0">{{Cite book|title=Being a Tamil and Sri Lankan|last=Civattampi|first=Kārttikēcu|date=2005|publisher=Aivakam|isbn=9789551132002|pages=134–135|language=en}}</ref> The inscription reads "erukatur eelakutumpikan polalaiyan", which translates to "Polalaiyan, (resident of) Erukatur, the husbandman (householder) from Eelam".<ref name="Schalk">{{Cite book | last=Schalk | first=Peter | contribution=Robert Caldwell's Derivation īlam<sīhala: A Critical Assessment | editor-last=Chevillard | editor-first=Jean-Luc | title=South-Indian Horizons: Felicitation Volume for François Gros on the occasion of his 70th birthday | place=Pondichéry | publisher=Institut Français de Pondichéry | isbn=978-2-85539-630-9 | pages=347–364 | year=2004 }}.</ref> | |||

| The Sangam literature '']'', mentions ''Eelattu-unavu'' (food from Eelam). One of the prominent Sangam Tamil poets is known as ] meaning Poothan-thevan (proper name) hailing from ''Eelam''. (]: 88, 231, 307; ]: 189, 360, 343; ]: 88, 366).<ref>{{Cite book|title=Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature: Sasay to Zorgot|last=Lal|first=Mohan|date=1992|publisher=Sahitya Akademi|isbn=9788126012213|pages=4155|language=en}}</ref> The Tamil inscriptions from the ] & ] period dating from 9th century CE link the word with toddy, toddy tapper's quarters (''Eelat-cheri''), tax on toddy tapping (''Eelap-poodchi''), a class of toddy tappers (''Eelath-chanran''). Eelavar is a caste of toddy tappers found in the southern parts of ].<ref name=":0" /> ''Eela-kaasu'' and ''Eela-karung-kaasu'' are refers to coinages found in the ] inscriptions of ].<ref>{{Cite book|title=Politics of Tamil Nationalism in Sri Lanka|last=Sivarajah|first=Ambalavanar|date=1996|publisher=South Asian Publishers|isbn=9788170031956|pages=122|language=en}}</ref> | |||

| ==Theories of origin== | |||

| ===Legend=== | |||

| Etymologically, the word ''Ezhava''/''Thiyya'' can be traced to ''Ezham'' (or ]), or ''Dweep'' (a ] word for ]). Most theories of origin for the Ezhavas suggest a Sri Lankan and ] connection. There is a hypothesis that Ezhavas are descendants of Buddhists (from Sri Lanka, or emissaries from the Magadhan empire) who refused to convert to Hinduism. This hypothesis has been supported by genetic studies which show that the allelic distribution of Ezhavas in a bi-dimensional plot (correspondence analysis based on HLA-A, -B, and -C frequencies) shows a rather strong East Eurasian element due to its proximity to the Mongol population in the same plot.<ref name = "Crypto">A crypto-Dravidian origin for the nontribal communities of South India based on human leukocyte antigen class I diversity, by R. Thomas, S. B. Nair & M. Banerjee, Human Molecular Genetics Laboratory, Rajiv Gandhi Centre for Biotechnology, 16 June 2006, Tissue Antigens ISSN 0001-2815</ref>. | |||

| According to |

There are ] for the Ezhava. According to some ] folk songs like ]<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Bright |first1=William |title=Review of Dialect Survey of Malayalam (Ezhava-Tiiya) |journal=Language |date=1978 |volume=54 |issue=1 |pages=249 |doi=10.2307/413041 |jstor=413041 }}</ref> {{which|date=April 2020}} and legend, the Ezhavas were the progeny of four bachelors that the king of ] (Sri Lanka) sent to what is now ] at the request of the ] king Bhaskara Ravi Varma, in the 1st century CE. These men were sent, ostensibly, to set up ] farming in the region.<ref>] pp. 25–26</ref> Another version of the story says that the king sent eight martial families at the request of a Chera king to quell a civil war that had erupted against him.<ref>{{cite book|last=G.|first=Rajendran|title=The Ezhava community and Kerala politics|date=1974|publisher=Kerala Academy of Political Science|oclc=898909945}}{{page needed|date=February 2022}}</ref> | ||

| ===Social and religious divergence=== | |||

| ===Buddhist Roots=== | |||

| It has been suggested that the Ezhavas may share a common heritage with the ] caste. This theory is based on similarities between numerous of the customs adopted by the two groups, particularly with regard to marking various significant life stages such as childbirth and death, as well as their matrilineal practices and martial history. Oral history, folk songs and other old writings indicate that the Thiyyas were at some point in the past members of the armed forces serving various kings, including the ]s of ] and the rulers of the ]. ] has said that only a common parentage can explain some of these issues.<ref name="Smith1976pp26-30">] pp. 26–30</ref> | |||

| A theory has been proposed for the origins of the ] based on the actions of the Aryan ]s introducing such distinctions prior to the 8th-century AD. This argues that the Jains needed protection when they arrived in the area and recruited local sympathizers to provide it. These people were then distinguished from others in the local population by their occupation as protectors, with the others all being classed as out-caste. Pullapilly describes that this meant they "... were given ''kshatriya'' functions, but only ''shudra'' status. Thus originated the Nairs." The Ezhavas, not being among the group protecting the Jains, became out-castes.<ref name="Smith1976pp26-30"/> ] | |||

| Buddhism in Kerala has direct connections to Sri Lanka from as far back as the 3rd century B.C.E., when the Buddhist monk Rakshithadheeran came to Kerala with his followers, to spread the faith. In addition to this, the ] edicts mention Kerala, which would imply that Asoka's efforts to spread Buddhism would have impacted Kerala as well. The two gods of the Ezhavas, ''Cittan'' and ''Arattan'' are respectively, ''Buddhist-Sidhan'' and ''Arhatan'', according to historian C. V. Kunjuraman. Further, the ''Pandarams'' who perform priestly duties in Ezhava temples are considered to be successors of Buddhist monks. T. K. Veluppillai, the author of ''The Travancore State Manual'', believes that during Buddhist ascendancy in ], before the arrival of the ] ]s, ''the Ezhavas enjoyed great prosperity and power'' (II, 845). However he also says that it is very unlikely that the ]s came from Sri Lanka and spread all over ]. He says that they were the mainstream of Munda-Dravidian immigrants who left ] in the fifth, sixth, and seventh centuries to avoid persecution at the hands of their political enemies.<ref>, ''kerala.cc''</ref> | |||

| An alternate theory states that the system was introduced by the ] Brahmins. Although Brahmin influences had existed in the area since at least the 1st century CE, there was a large influx from around the 8th century when they acted as priests, counsellors and ministers to invading Aryan princes. At the time of their arrival the non-aboriginal local population had been converted to Buddhism by missionaries who had come from the north of India and from Ceylon. The Brahmins used their symbiotic relationship with the invading forces to assert their beliefs and position. Buddhist temples and monasteries were either destroyed or taken over for use in Hindu practices, thus undermining the ability of the Buddhists to propagate their beliefs.<ref name="Smith1976pp26-30"/> | |||

| The noted poet Mahakavi ], whose poems or ''Khandakavya'' such as ''Nalini'', ''Leela'', ''Karuna'' and ''Chandala Bhikshuki'' extol Buddhist ideals. He laments at times in his verses the past glory of the Sinhalese, or the natives of ], whom he considered to be the forefathers of present day ]s. <ref>''Oru Simha Prasavam'' by Kumaranasan</ref> | |||

| The Buddhist tradition of the Ezhavas, and the refusal to give it up, pushed them to an outcaste role within the greater Brahminic society.<ref name="Smith1976pp26-30"/><ref>{{cite book | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=A6MfPh-9DiEC&pg=PA25 | page=18 | title=On life and times of George Joseph, 1887–1938, a Syrian Christian nationalist from Kerala | last=Joseph |first=George Gheverghese | publisher=Orient Longman | year=2003 | access-date=2007-12-09 | isbn=978-81-250-2495-8}}</ref> This tradition is still evident as Ezhavas show greater interest in the moral, non-ritualistic, and non-dogmatic aspects of the religion rather than the theological.<ref name="Smith1976pp26-30"/> | |||

| What would further support the Buddhist connection of Ezhavas would be the fact that a large number of Buddha images have been discovered in the coastal districts of Alleppey and Quilon. The most important Buddha-image is the famous ''Karumadi Kuttan'' near ]. These areas also have the highest concentration of ]s in ]. | |||

| ==Past occupations== | |||

| ===Migrants from Iran=== | |||

| The Ezhava used to work as agricultural labourers, small cultivators, ]s and liquor businessmen; some were also involved in weaving and some practised ].<ref name="Smith1976pp31-32" /><ref>{{cite book |last=Rao |first=M. S. A. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=tZAiAAAAMAAJ&q=Chekor+kalari |title=Social Movements and Social Transformation |publisher=Macmillan |year=1979 |isbn=9780333902554 |page=23}}</ref> An upper section, by reason of wealth and/or influence, came into the position to acquire titles such as Panicker from the local rulers. These people lived in Nalukettu, had their private temples and owned a large amount of land.<ref name="Osella50" /> | |||

| ] | |||

| The social anthropologists Filippo and Caroline Osella say that the Ezhavas "... consisted in the mid-nineteenth century of a small landowning and titled elite and a large mass of landless and small tenants who were largely illiterate, considered untouchable, and who eked out a living by manual labour and petty trade."<ref name="Osella8">{{cite book |title=Social Mobility in Kerala: Modernity and Identity in Conflict |first1=Filippo |last1=Osella |first2=Caroline |last2=Osella |publisher=Pluto Press |year=2000 |isbn=978-0-7453-1693-2 |page=8 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=rMRw0gTZSJwC&pg=PA8}}</ref>{{efn|Gough describes Ezhava subtenants in Central Travancore, who worked land held by the Nair caste. One-third of the net produce from these lands was retained by the subtenants and the remainder was the property of the Nair tenant.<ref>{{cite book |title=Matrilineal Kinship |editor1-first=David Murray |editor1-last=Schneider |editor2-first=E. Kathleen |editor2-last=Gough |chapter=Nayars: Central Kerala |first=E. Kathleen |last=Gough |author-link=Kathleen Gough |page=315 |year=1961 |publisher=University of California Press |isbn=978-0-520-02529-5 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=lfdvTbfilYAC&pg=PA315 |quote=Tiyyars (called Iravas in Cochin)}}</ref>}} ], another social anthropologist and himself a member of the caste,<ref name="Osella8" /> noted the mythical belief that the Ezhava brought coconut palms to the region when they moved from Ceylon.<ref name="Osella50">{{cite book |last1=Osella |first1=Filippo |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=rMRw0gTZSJwC&pg=PA50 |title=Social Mobility in Kerala: Modernity and Identity in Conflict |last2=Osella |first2=Caroline |publisher=Pluto Press |year=2000 |isbn=978-0-7453-1693-2 |pages=55}}</ref> Their traditional occupation, or ''avakasam'', was tending to and tapping the sap of such palms. This activity is sometimes erroneously referred to as ''toddy tapping'', toddy being a liquor manufactured from the sap. Arrack was another liquor produced from the palms, as was jaggery (an unrefined sugar). In reality, most Ezhavas were agricultural labourers and small-time cultivators, with a substantial number diverging into the production of ] products, such as coconut mats for flooring, from towards the end of the 19th century.<ref name="Nossiter1982p30"/> The coastal town of ] became the centre of such manufacture and was mostly controlled by Ezhavas, although the lucrative export markets were accessible only through European traders, who monopolised the required equipment. A boom in trade for these manufactured goods after ] led to a unique situation in twentieth-century Kerala whereby there was a shortage of labour, which attracted still more Ezhavas to the industry from outlying rural areas. The ] impacted in particular on the export trade, causing a reduction in price and in wages even though production increased, with the consequence that during the 1930s many Ezhava families found themselves to be in dire financial circumstances.<ref name="Osella50" /><ref>{{cite book |title=Communal Road to a Secular Kerala |first=George |last=Mathew |publisher=Concept Publishing Company |year=1989 |isbn=978-81-7022-282-8 |pages=137–138 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=1TuPeXFP0WgC&pg=PA137}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |title='Destroy Capitalism!': Growing Solidarity of Alleppey's Coir Workers, 1930–40 |first=Robin |last=Jeffrey |author-link=Robin Jeffrey |journal=Economic and Political Weekly |volume=19 |issue=29 |pages=1159–1165 |date=21 July 1984 |jstor=4373437}}</ref> ] | |||

| In the ''Vadakkan Pattukal'' (Northern Ballads), it is said that the ''Ezhavas'' arrived in Kerala by sea from ''Elam''. ''Elam'' is interpreted to be Sri Lanka. However, there is another school of thought that refers to the ] civilization in ancient ]. The ] is hypothesized to be a ]. | |||

| Some Ezhavas were involved in weaving and ship making.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=bVgeAAAAMAAJ&q=jaggery|title= Religion and ideology in Kerala |page=246|first=Geneviève |last=Lemercinier|publisher=D.K. Agencies |year=1984|isbn= 9788185007021 |access-date=2011-06-21}}</ref> | |||

| ==Past Occupations== | |||

| ===Martial traditions=== | |||

| In the bygone era, many Ezhavas were notable as Ayurvedic physicians, warriors and traders. In fact one of the early translations of ] (a celebrated ] treatise on ]) to ] was by an Ezhava physician,'' Kayikkara Govindan Vaidyar''. After the arrival of ] ]s and with the establishment of Vedic system, Ezhavas were discriminated and subjugated to take up lowly placed jobs like toddy tapping, selling and making of arrack, palm wine etc. Vast majority were farmers and was placed outside the Varna system classifying them as ] by this new ruling class. However many were wealthy and some others were masters in various fields such ](medicine), martial arts (], ] etc), ], ], ''Manthravaadam'', ], Merchant Trading, Visha chikitsa etc. Also, there were many distillers and weavers from this community.<ref name = "ezh1">Bardwell L. Smith, Religion and Social Conflict in South Asia. (BRILL publications, 1976,ISBN 9004045104), Page 27</ref> <ref name=""ezh1a">{{cite web|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=07Y3AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA27&lpg=PA27&dq=izhava+kerala&source=web&ots=zFl70XFRFi&sig=FhdgryHrCKak2z2bK3yvQl8IjJk#PPA27,M1|title= Religion and Social Conflict in South Asia. Page 27|work=Bardwell L. Smith|publisher=(BRILL publications ,1976|accessdate=Aug 17, 2007}}</ref> <ref name = "ezh2">Bardwell L. Smith, Vadakkan and Thekkan Pattukal. (Sri Rama Vilasom Press, 1967), Page 128 - 148</ref> <ref name = "ezh3">Nagam Aiya, Travancore State Manual by Nagam Aiya</ref> | |||

| Some Ezhava served in army of local chieftains and local rulers such as of ] and ] of Kerala, who were privileged in the pre-colonial period to have their own private armies.<ref>{{cite book | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=A6MfPh-9DiEC&pg=PA25 | page = 20 | title = On life and times of George Joseph, 1887–1938, a Syrian Christian nationalist from Kerala | author = Joseph, George Gheverghese | publisher = Orient Longman | year = 2003 | access-date = 2007-12-09 | isbn=978-81-250-2495-8}}</ref> | |||

| === |

====Chekavar==== | ||

| A subgroup of the Ezhavas considered themselves to be warriors and became known as the Chekavars. The '']'' ballads describe Chekavars as forming the militia of local chieftains and kings but the title was also given to experts of Kalari Payattu.<ref name = "chek1002">{{cite book |first=Elamkulam P. N. Kunjan |last=Pillai |title=Studies in Kerala History |publisher=National Book Stall |location=Kottayam |year=1970 |pages=111, 151–154}}</ref> | |||

| There were in fact several acclaimed Ezhava Ayurvedic scholars. The first ] book published by the Dutch in 1675 titled '''Hortus Indicus Malabaricus''' speaks in its preface about a Vaidyar (doctor) Mr. Karappuram Kadakkarappally Kollattu Veettil Itty Achuthan(of present-day ] district), a reputed vaidyar of the community as the main force behind the book and it is he who had edited the book to reach its present form. Famous ezhava Vaidyar Sri ] founded of ]. He was awarded ''Vaidyaratnam'' title by K.C. Manavikraman '']'' of ] in 1953. Famous Thirumanakkal Vvaidyasala in ] and Kannur Ayurvedic Multi Speciality Hospital in ] are owned by Ezhava vaidyars. Famous Ayurvedic scholar from ] New Udaya Pharmacy and Ayurvedic Laboratories (Nupal) were established in 1960 by Sri N. K. Padmanabhan Vaidyar, who hails from a well-known traditional Ayurvedic family. Their product ] is now famous among patients having liver diseases. Vallabhassery Ayurvedic Pharmaceutical Firm established in the Ayurvedic field since 1833 by Vallabhasseril family of ]. | |||

| One of the early translations of Ashtanga Hridaya (a celebrated ] treatise on ]) to ] was by an Ezhava physician, Kayikkara Govindan ]. Kuzhuppully and Pokkanchery families in ] and ] respectively are traditional families of Ayurvedacharyans. Cholayil family is one of the most famous and respected ezhava Ayurvedic families in Kerala. Their beauty products like ''Cuticura'' and ] are very popular across ]. Ezhava physicians were the chief Ayurvedic physicians of the Travancore Royal family. Venmanakkal family (related to the Chavercode family) was the first family to learn Ayurveda from the Pali language in addition to the Ayurvedic knowledge from Sanskrit. Uracheril Gurukkal instructed ] in the field of ] and ], and Uppot kannan, who wrote interpretation of Yogamrutham (Ayurvedic text in Sanskrit by Ashtavaidyans), were also acclaimed Ezhava Ayurvedic scholars. Kelikkodan Ayyappan Vaidyar (Kottakkal) is one of the pioneer in the traditional Ayurvedic physician who is an eminent personality in Marma Chikithsa. <ref>Travancore State Manual</ref><ref name = "ezh1">Bardwell L. Smith, Religion and Social Conflict in South Asia. (BRILL publications, 1976,ISBN 9004045104), Page 27</ref> <ref name=""ezh1a">{{cite web|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=07Y3AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA27&lpg=PA27&dq=izhava+kerala&source=web&ots=zFl70XFRFi&sig=FhdgryHrCKak2z2bK3yvQl8IjJk#PPA27,M1|title= Religion and Social Conflict in South Asia. Page 27|work=Bardwell L. Smith|publisher=(BRILL publications ,1976|accessdate=Aug 17, 2007}}</ref> <ref name = "ezh2">Bardwell L. Smith, Vadakkan and Thekkan Pattukal. (Sri Rama Vilasom Press, 1967), Page 128 - 148</ref><ref name = "ezh3">Nagam Aiya, Travancore State Manual by Nagam Aiya</ref> | |||

| === |

===Medicine and traditional toxicology=== | ||

| Some Ezhavas had an extensive knowledge of the medicinal value of plants, passed to them by their ancestors. Known as ''Vaidyars'', these people acted as physicians. ] was probably the best known Ezhava physician: he directly influenced the botanical classification in '']'', published during the 17th century. Achudan's texts were written in the ] script that Ezhava castes used, for they were prevented from learning the more Sanskritised Aryazuthu script which was the preserve of the upper-castes.<ref>{{cite journal |title=Indigenous Knowledge and the Significance of South-West India for Portuguese and Dutch Constructions of Tropical Nature |first=Richard |last=Grove |journal=Modern Asian Studies |volume=30 |issue=1 |date=February 1996 |pages= 121–143|jstor=312903 |doi=10.1017/s0026749x00014104|s2cid=144682406 }}</ref> | |||

| Many ezhava families were practitioners of Visha chikitsa (]) for decades though it has been discontinued by many of these families now. This '']'' include treatment and cure of poison incurred from snake-bite, scorpion bite etc. ' | |||

| Some Ezhavas practiced ayurvedic medicine.<ref name="Alan Bicker 2000 9">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=FS7dkOgNGT0C&pg=PA9|title= Indigenous environmental knowledge and its transformations|page=9|first=RF Ellen Peter Parkes |last=Alan Bicker|publisher=Routledge |year=2000|access-date=2011-06-15|isbn= 9789057024832}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8XJ2HHZcM6oC&pg=PA83|title= Ecological Journeys |page=82|first=Madhav |last=Gadgil|publisher=Orient Blackswan |year=2005|access-date=2011-06-15|isbn= 9788178241128}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=WwNUblS-jpwC&pg=PA3120|title= Modern World System and Indian Proto-Industrialization |page=312|first=Abhay Kumar |last=Singh|publisher=Northern book center |year=2006|access-date=2011-06-15|isbn= 9788172112011}}</ref> | |||

| 'Theraickal Tharavadu'', an ezhava family from eroor, ], were the Visha Vaidyars of ] royal family. <ref name = "ezh32"> Keralakaumudi, Sree Narayana Directory, (kaumudi Publications, 2007)</ref> The Saint ]'s maternal uncle was a famous Visha Vaidyar of the Chiryinkilil area. Some of the families who were famous in this treatment were Chavarkode vaidyars of ], Aneppil family of Kollam, Kavil and Muloor families of Central Travancore etc. | |||

| ===Martial traditions=== | |||

| {{main|Chekavar}}{{main|Channar}}{{main|Panicker}}{{main|Varma Kalari}} | |||

| Ezhavas strived to maintain a martial tradition. The ] Tharavad (], ]) that supplied palace guards to the Royal House of Pandalam and the Valiya Mundakkal tharavadu of eastern ] that had men enlisted with the Army of Venad kingdom find mention in the annals of history preserved in certain old records. Cheerappanchira ] was the place where Lord ] gained special martial arts knowledge. In fact many of the foot soldiers in royal armies were of Ezhava origin. ''Puthooram veedu'', family of Legendary ] and ], had rich martial traditions. ]s from ''Varanappally ]'' in Central ] were military commanders of ] Kingdom for many centuries. Channars of Alummoottil Tharavad, an Ezhava family of renown from the central ], were also Warriors and ] trainers. The army of the Maharaja of ] and ] took recruits to infantry and light cavalry from this ] during the 17th and 18th century. Similarly, the Lakshana Panicker family of ] district(bordering ]) were reputed practitioners of kalaripayattu and were enrolled as trainers for the army of Maadathumkoor kingdom (present ]). Famous ] ]s/]s of Melathil Tharavad at Thoduvetty of ] district, in the southern part of erswhile ] Kingdom, has safeguarded the Great ] ], by giving protection to His Highness, while in exile. ] in Haripad was an Ezhava warrior lived in the 19th century who fought against the caste oppression by the so called upper castes. ] ]s from an Ezhava tharavaad based at Kulathoor were trainers of famous ]s. Their descendants have looked after the ] ] (] devatha) temple at Thozhuvancode, ].<ref name = "ezh1">Bardwell L. Smith, Religion and Social Conflict in South Asia (BRILL publications, 1976,ISBN 9004045104), Page 27</ref> <ref name=""ezh1a">{{cite web|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=07Y3AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA27&lpg=PA27&dq=izhava+kerala&source=web&ots=zFl70XFRFi&sig=FhdgryHrCKak2z2bK3yvQl8IjJk#PPA27,M1|title= Religion and Social Conflict in South Asia Page 27|work=Bardwell L Smith|publisher=(BRILL publications ,1976|accessdate=Aug 17, 2007}}</ref> <ref name = "ezh2"> Vadakkan and Thekkan Pattukal. (Sri Rama Vilasom Press, 1967), Page 128 - 148</ref> <ref name = "ezh3">Nagam Aiya, Travancore State Manual by Nagam Aiya</ref> Other Ezhava Kalari warriors include ], and ]. | |||

| ===Trading, Toddy Tapping, Brewing Arrack=== | |||

| Coconut trading was one of the traditional occupations of the community. A large number of members were also involved in the ] tapping business as toddy was a widely consumed alcoholic drink, in addition to be used in Ayurvedic medicine. A few sections of the community were also involved in brewing ]. ] preached against both of these processions and as a result, many members discontinued their practices although a few still continued.<ref name = "ezh33"> Thomas Johnson Nossiter and Frederick Albert Cook, Communism in Kerala: A Study in Political Adaptation (C. Hurst & Co Publishers, 1982, ISBN 0905838408), Page 21</ref><ref name = "ezh34"> Keralakaumudi, Sree Narayana Directory, (kaumudi Publications, 2007), page 21</ref><ref name="ezh35">{{cite web|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=pDlh-RIqrfoC&pg=PA30&dq=ezhava+ritual&sig=GhJRu_o6Ypu6ErEjV14-L6EkYp8#PPA21,M1|title=Communism in Kerala: A Study in Political Adaptation, P 22|work=Thomas Johnson Nossiter and Frederick Albert Cook|publisher=C. Hurst & Co Publishers|accessdate=2007-09-04}}</ref> | |||

| ==Culture== | ==Culture== | ||

| ] | |||

| ===Theyyam or Kaliyattam or Theyyatom === | |||

| ] as Lord ] & Lord ]]] | |||

| Popular in north ], ] incorporates dance, mime and music and preserves the rudiments of ancient tribal cultures; attaching great importance to the worship of heroes and the spirits of ancestors. The headgear and other ornamental decorations are spectacular in sheer size and appearance. This particular dance form is also known as Kaaliyattam. Theyyam is also performed by Vaniya, Kammala, ] and ] communities apart from thiyyas. The main deities of ezhavas are ''Vayanattu Kulavan, Kathivannur Veeran, Poomaruthan, Muthappan'' etc. <ref name = "ezh22"> Ronald M. Bernier, Temple Arts of Kerala: A South Indian Tradition (Asia Book Corporation of America, 1982 ,ISBN 0940500795)</ref> <ref name = "ezh23"> Krishna Chaitanya, Temple Arts of Kerala: A South Indian Tradition (Abhinav Publications, 1987 ,ISBN 8170172098)</ref> | |||

| === |

===Arjuna Nrtam (Mayilpeeli Thookkam)=== | ||

| Arjuna |

] ("the dance of ]") is a ritual art performed by Ezhava men and is prevalent in the ] temples of south Kerala, mainly in ], Alappuzha and ] districts. The ritual is also called "Mayilpeeli Thookkam" because the costume includes a characteristic garment made of mayilppeeli (] feathers). This garment is worn around the waist in a similar fashion as the "uduthukettu" of ]. The various dance movements are similar to kalarippayattu techniques. The performers have their faces painted green and wear distinctive headgears. The all-night performance of the dance is usually presented solo or in pairs.<ref name="ezh22">{{cite book | last=Bernier|first=Ronald M. | title = Temple Arts of Kerala: A South Indian Tradition | publisher = Asia Book Corporation of America | year = 1982 | isbn = 978-0-940500-79-2}}</ref>{{page needed|date=April 2020}} | ||

| ===Makachuttu=== | |||

| The songs which are strictly rhythm based are called ''Mayil Pattukal'' or ''Kavithangal'' and deal with various themes of the ]s (ancient ] scriptures). Each ''Kavitham'' is composed to suit a specific rhythm. Before each song the dancers explain the intricacies of the particular rhythm about to be employed and how this rhythm is translated into dance movements. Percussion instruments like the chenda, maddalam, talachenda and ilathalam (cymbal) form the musical accompaniment. <ref name = "ezh22"> Ronald M. Bernier, Temple Arts of Kerala: A South Indian Tradition (Asia Book Corporation of America, 1982 ,ISBN 0940500795)</ref> | |||

| Makachuttu art is popular among Ezhavas in ] and Chirayinkizhu taluks and in ], Pazhayakunnummal and Thattathumala regions. In this, a group of eight performers, two each, twine around each other like serpents and rise up, battling with sticks. The techniques are repeated several times. ] paste on the forehead, a red towel round the head, red silk around the waist and bells round the ankles form the costume. This is a combination of ] and ].<ref name = "ezh22"/>{{page needed|date=April 2020}}<ref name = "ezh23">Krishna Chaitanya, Temple Arts of Kerala: A South Indian Tradition (Abhinav Publications, 1987,{{ISBN|8170172098}})</ref>{{page needed|date=April 2020}} | |||

| === |

===Poorakkali=== | ||

| Poorakkali is a folk dance prevalent among the Ezhavas of Malabar, usually performed in Bhagavathy temples as a ritual offering during the month of ] (March–April). Poorakkali requires specially trained and highly experienced dancers, trained in Kalaripayattu. Standing round a traditional lamp, the performers dance in eighteen different stages and rhythms, each phase called a niram.<ref name="ezh22"/>{{page needed|date=April 2020}} | |||

| ==Customs== | |||

| === Parichamuttu Kali === | |||

| Ezhavas adopted different patterns of behavior in family system across Kerala. Those living in southern ] tended to meld the different practices that existed in the other parts of Kerala. The family arrangements of northern ] were matrilineal with patrilocal property arrangements, whereas in northern Travancore they were matrilineal but usually matrilocal in their arrangements for property. Southern Malabar saw a patrilineal system but partible property.<ref name="Nossiter1982p30"/><ref name="jeffrey1974">{{cite journal |first=Robin |last=Jeffrey |author-link=Robin Jeffrey |title=The Social Origins of a Caste Association, 1875–1905: The Founding of the S.N.D.P. Yogam |journal=South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies |volume=4 |issue=1 |pages=39–59 |date=1974 |doi=10.1080/00856407408730687}}</ref> | |||

| This martial folk-dance prevalent among the ezhavas of in ], ], ], ], ], ] and ] districts. Its also performed by Christians and some other Hindu communities. It had its origin during the day when ], the famous physical exercise of swordplay and defence, was in vogue in ]. The performers dance with swords and shields in their hands, following the movements of sword fight, leaping forward, stepping back and moving round, all the time striking with the swords and defending with shields. <ref name = "ezh22"> Ronald M. Bernier, Temple Arts of Kerala: A South Indian Tradition (Asia Book Corporation of America, 1982 ,ISBN 0940500795)</ref> | |||

| These arrangements were reformed by legislation, for Malabar in 1925 and for Travancore in 1933. The process of reform was more easily achieved for the Ezhavas than it was for the Nairs, another Hindu caste in Kerala who adopted matrilineal arrangements; the situation for the Nairs was complicated by a traditional matrilocal form of living called '']'' and by their usually much higher degree of property ownership.<ref name="Nossiter1982p30"/> That said, certainly by the 1880s, the Ezhavas appear increasingly to have tried to adopt Nair practises in a bid to achieve a similar status. ] notes that their women began to prefer the style of jewellery worn by Nairs to that which was their own tradition. Further, since Nairs cremated their dead, Ezhavas attempted to cremate at least the oldest member of their family, although cost usually meant that the remainder were buried. Other aspirational changes included building houses in the Nair tharavad style and making claims that they had had an equal standing as a military class until the nineteenth century.<ref name="jeffrey1974"/> | |||

| ===Makachuttu=== | |||

| ] | |||

| This ezhava art is Popular among ezhzvas in ] and Chirayinkizhu taluks and in ], Pazhayakunnummal and Thattathumala regions. In this, there will be a group of eight performers, two each, twin around each other like serpents and rising up, battle it out with sticks. The techniques are repeated several times. Sandalwood paste on the forehead, a red towel round the head, red silk around the waist and bells round the ankles. These form the costume. This is a combination of ] and ].<ref name = "ezh22"> Ronald M. Bernier, Temple Arts of Kerala: A South Indian Tradition (Asia Book Corporation of America, 1982 ,ISBN 0940500795)</ref> <ref name = "ezh23"> Krishna Chaitanya, Temple Arts of Kerala: A South Indian Tradition (Abhinav Publications, 1987 ,ISBN 8170172098)</ref> | |||

| ] was practised in within certain parts of Ezhava community, but has since died out. There are several proposed arguments for this, the Valiyagraman Ezhavas argue that they practised it for economic reasons, the argument that the older brother would marry first, and share his wife with his younger brother(s) until they could afford to marry. It was also common for one of the brothers to be away for long periods of time.<ref>{{cite book|author1=Filippo Osella|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=rMRw0gTZSJwC&dq=social+mobility+in+kerala+filippo+osella+polyandry&pg=PA89|title=Social Mobility In Kerala: Modernity and Identity in Conflict|author2=Caroline Osella|date = 20 December 2000|isbn=0-7453-1694-8|pages=89–90| publisher=Pluto Press }}</ref> | |||

| Following the British settlement in what became Kerala, some Thiyya families in ] were taken as concubines by British administrative officers who were in charge of ]. Children resulted from these relationships and were referred to as "white Thiyyas". These liaisons were considered as "dishonourable" and "degrading" to the Thiyya community and were excluded from it. Most of these women and children became Christians. The Thiyyas in northern Malabar generally had a better relationship with colonisers than the Hindus in other parts of the country. This was due in part to the fact that the British would employ Thiyyas but local princes would not.<ref>{{cite book|author1=Robin Jeffrey|title=Politics, Women and Well-Being: How Kerala Became 'a Model'|date=27 July 2016|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ENC-DAAAQBAJ&dq=Tiyyas+in+north+Malabar+fared+better+than+in+south+Malabar%2C+perhaps+because+land+was+more+readily+available.+They+were+matrilineal+before+the+British+East+India+company+estalished+forts+at+Telicherry+and+Cannanore+in+the+early+eighteenth+century%2C+and+some+Tiyya+families+permitted+their+women+to+form+liaisons+with+Europeans.+A+small+community+%E2%80%94+the+so-called+%E2%80%98white+Tiyyas%E2%80%99+%E2%80%94+resulted%2C+and+though+the+suggestion+of+concubinage+with+Europeans+became+a+great+embarrassment+in+the+twentieth+century%2C+such+arrangements+brought+considerable+advantage+in+the+eighteenth+and+nineteenth+centuries.+Tiyyas+in+north+Malabar%2C+even+if+not+members+of+%E2%80%98white+Tiyya%E2%80%99+families%2C+developed+a+smoother+relationship+with+the+European+rulers+than+Hindus+elsewhere+in+Kerala.+The+British%2C+unlike+Kerala%27s+princes+readily+employed+Tiyyas%2C+and+Tiyya+factotum+became+a+constant+companion+of+some+British+officials&pg=PA50|isbn= 978-1-349-12252-3|page=50|publisher=Springer }}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=rMRw0gTZSJwC&dq=social+mobility+in+kerala+filippo+osella+pallor+skin+tone&pg=PA83|title = Social Mobility in Kerala: Modernity and Identity in Conflict|isbn = 9780745316932|last1 = Osella|first1 = Filippo|last2 = Caroline|first2 = Filippo|last3 = Osella|first3 = Caroline|date = 20 December 2000| publisher=Pluto Press }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://science.thewire.in/politics/caste/janaki-ammal-geeta-doctor-caste-poems/|title=E.K. Janaki Ammal and the Caste Conundrum – The Wire Science|date=15 August 2020}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Abraham |first1=Janaki |title=The Stain of White: Liaisons, Memories, and White Men as Relatives |journal=Men and Masculinities |date=October 2006 |volume=9 |issue=2 |pages=131–151 |doi=10.1177/1097184X06287764 |s2cid=145540016 }}</ref> | |||

| === Aivar Kali === | |||

| Literally, Aivarkali means the play of the five sets. This was a ritualistic art form performed in almost all important temples of ]. Today it is found in central Kerala. This is also known as Pandavarkali, which means the play of the Pandavas, (the five heroes of Mahabharatha), and is performed by the following communities: Ezhava, Asari, Moosari, Karuvan, Thattan and Kallasari. | |||

| This ritualistic dance is performed beneath a decorated pandal with a nilavilakku at its centre. | |||

| The performers numbering five or more with their leader called Kaliachan enter the performance area after ritualistic bath, with sandal paste over their foreheads. They will be dressed in white dhoti and will have a towel wrapped around their heads.<ref name = "ezh22"> Ronald M. Bernier, Temple Arts of Kerala: A South Indian Tradition (Asia Book Corporation of America, 1982 ,ISBN 0940500795)</ref> | |||

| == Customs== | |||

| === Family System And Tharavadu === | |||

| {{main|Tharavadu}} | |||

| {{main|Marumakkathayam}} | |||

| Ezhavas followed, ], which was a system of joint family practised by some ] communities. Each ] has a unique name. The family lived together in this type ] comprised of a mother, her brothers and younger sisters, and her children. The oldest male member was known as the ''Karanavar'' or ''Mooppar'' and was the head of the household and managed the family estate. As joint families grew and established independent settlements, the branches modified the names in a such way that the main Tharavadu names are identifiable, yet Sakha (or ''Thavazhi'', i.e. Thay Vazhi which means ''Through Mother'') had a distinct name. For ezhavas in ] and ] ''Tharavad name'' were identified through their Mother's house (''Thavazhi'') but some other families in ] area (except in Kanayannur ]) were identified through by their father's ''Tharavadu''. This system of inheritance were matrilinear and were know as ]. However, now-a-days, most of the families follow ''Makkathayam''(patrilinear) system of family inheritance. | |||

| ===Snake Worship=== | |||

| {{Main|Sarpa Kavu}} {{Main|Snake worship}} | |||

| The snake worship(''Nagaradhana'') was prevalent among many ezhava families all over ], but was most common among ] and ] ]s of North ] and ]. ''Sarpa Kavu'' (meaning ''Abode of the Snake God''), small traditional forest (mostly man made) of green pockets, would have idols of snake gods and worshipped. For ezhavas, billavas and other similar communities, these sarpakavus can be any corner of the ] except eastern side while for some other communities like ]s it would be on the southwest corner of the ]. <ref name = "ezh32"> Keralakaumudi, Sree Narayana Directory, (kaumudi Publications, 2007)</ref> | |||

| ===Kuruthi=== | |||

| It was a rutual performed in temples especially ], ], ] temples. Though this was found among many communities, it was very common with ezhavas. Animals were sacrificed as part of the ritual. Kuruthy was also performed before padayani and Mudiyet in South Central ]. And in North Kerala, it was performed with ] and Pana. ] took the initiative to stop this ritual and now-a-days it's not so common in ].<ref name = "ezh36"> Keralakaumudi, Sree Narayana Directory, (kaumudi Publications, 2007)</ref> | |||

| ===Thali Kettu Kalyanam (Mock marriage ceremony)=== | |||

| {{main|Kettu Kalyanam}} | |||

| This type of marriage was prevalent among some Ezhava Pramanis (rich among the community). The ''thaali'' ( a gold necklace tied around the bride's neck) tying rite took place before the onset of puberty. During this ceremony the girl was forced to marry a man (from same community unlike other castes which followed this cutsom) whose horoscope matched with that of the girl. Though that man becomes her ''mock'' husband, he could simply leave the girl after the completion of the ritual. ] opposed this strongly and took the initiative to simplify marriage customs and celebrations. <ref name = "ezh36"> Keralakaumudi, Sree Narayana Directory, (kaumudi Publications, 2007)</ref> | |||

| <ref name = "ezh37"> David Smith, Hinduism and Modernity (Blackwell Publishing, 2003), ISBN 0631208623</ref> | |||

| ==Spiritual and social movements== | ==Spiritual and social movements== | ||

| ] | |||

| {{Original research|date=October 2007}} | |||

| The arrival of ] heralding an era of Hinduism, might have initiated the ostracization the Ezhavas.{{fact|date=October 2007}} There is a much disputed claim that the legend of Onam marks the conversion of Buddhist Kerala to ].{{fact|date=October 2007}} Accordingly, Ezhavas are the descendants of those Buddhists. The violence towards the Viharas, or the abodes of Budhdist monks, was soon to follow. The economic condition of the Ezhavas was abysmal at the turn of the last century. Social taboos had reduced them to a state of abject penury. | |||

| Some Ezhavas converted to ] from around the 9th century, due to the influence of Arab traders. These people, and other Muslim converts in the region, are now known as ]s.<ref name="Gough313" /> A sizeable part of the Ezhava community, especially in central ] and in the ], embraced ] during the ], due to caste-based discrimination. In ], ] missions started working in the first half of the 19th century, notably the ]. Most of their converts were from the Ezhava community.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=wFsbAAAAIAAJ&q=cannanore+thiyya|title= Kerala District Gazetteers: Palghat|page=188|first=C. K |last=Kareem|publisher=printed by the Superintendent of Govt. Presses |year=1976|access-date=2011-06-24}}</ref> The ]ist ] and the ] ] were also prominent in the movement for religious conversion, having established presences in the Travancore region in the early 19th century.<ref>{{cite book |title=Missionary Encounters: Sources & Issues |editor1-first=Robert A. |editor1-last=Bickers |editor2-first=Rosemary E. |editor2-last=Seton |publisher=Routledge |year=1996 |isbn=9780700703708 |chapter=Who is to benefit from missionary education? Travancore in the 1930s |first=Dick |last=Kooiman |page=158 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=98D8AemziJoC&pg=PA158}}</ref> | |||

| Till the 18th century, females of non-Brahmin class, were allowed to wear only a single loin cloth is girdled round the waist leaving the upper part exposed. In this respect males and females, rajas and nobles, rich and poor are equal. None of the ] ladies except ]s thought that the breast was to cover; and to them to cover the breast was an act of immodesty. There are instances of cruelties inflicted upon the ladies for violating these laws. An Ezhava lady who happened to travel abroad and returned well dressed was summoned by the Queen of ] and her breast was cut off for covering them.{{fact|date=October 2007}} In Travancore a riot occurred when group of local Brahmins assaulted a lady of Ezhava caste for wearing cloth below her knees.{{fact|date=October 2007}} In 1859 another riot took place in ] and continued for several days, when the ladies of the ] caste started to cover the breast. The revolt was called ''Chela kalapam (cloth revolt)''. <ref name = "ezh24"> Lloyd I. Rudolph, Susanne Hoeber Rudolph, The Modernity of Tradition: Political Development in India (University of Chicago Press, 1967, ISBN 0226731375)</ref><ref name = "ezh25"> Ilamkulam Kunhan Pilllai, Studies in Kerala History</ref><ref name = "ezh26"> C. Kesavan - Oru Jeevitha Samaram</ref> | |||

| The lowly status of the Ezhava meant that, as ] has commented, they had "little to lose and much to gain by the economic and social changes of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries". They sought the right to be treated as worthy of an English education and for jobs in government administration to be open to them.<ref name="Nossiter1982p30"/> An early Ezhava campaigner and their "political father", according to Ritty Lukose, was ].<ref>{{cite book |page=209 |first=Ritty A. |last=Lukose |chapter=Recasting the Secular: Religion and Education in Kerala, India |title=Everyday Life in South Asia |editor1-first=Diane P. |editor1-last=Mines |editor2-first=Sarah |editor2-last=Lamb |edition=2nd |publisher=Indiana University Press |year=2010 |isbn=9780253354730 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=828fOvb61wIC&pg=PA209}}</ref> In 1896, he organised a petition of 13,176 signatories that was submitted to the ] of the ] of Travancore, asking for government recognition of the Ezhavas' right to work in public administration and to have access to formal education.<ref>{{cite book |title=Being Middle-class in India: A Way of Life |editor-first=Henrike |editor-last=Donner |first=Caroline |last=Wilson |chapter=The social transformation of the medical profession in urban Kerala : Doctors, social mobility and the middle classes |publisher=Routledge |location=Abingdon, Oxon |year=2011 |isbn=978-0-415-67167-5 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=1_e8FT54FjIC&pg=PT193 |pages=193–194}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |title=Different Types of History |editor-first=Bharati |editor-last=Ray |chapter=Subjects of New Lives |first=Udaya |last=Kumar |publisher=Pearson Education India |year=2009 |isbn=978-81-317-1818-6 |page=329 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=9x5FX2RROZgC&pg=PA329}}</ref> Around this time, nearly 93 per cent of the caste members were illiterate.<ref name="Padmanabhan">{{cite book |chapter=Learning to Learn |first=Roshni |last=Padmanabhan |title=Development, Democracy and the State: Critiquing the Kerala Model of Development |editor-first=K. Ravi |editor-last=Raman |publisher=Routledge |year=2010 |isbn=978-1-13515-006-8 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=IGiMAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA106 |page=106}}</ref>{{efn|Robin Jeffrey notes that literacy among Ezhava men increased from 3.15 per cent to 12.10 per cent between the ], mainly through the work of missionaries rather than government schools.<ref name="jeffrey1974"/>}} The upper caste Hindus of the state prevailed upon the Maharajah not to concede the request. The outcome not looking to be promising, the Ezhava leadership threatened that they would convert from Hinduism en masse, rather than stay as ]s of Hindu society. ], realising the imminent danger, prompted the Maharajah to issue the ], which abolished the ban on lower-caste people from entering Hindu temples in the state.{{citation needed|date=March 2013}} Steven Wilkinson says that the Proclamation was passed because the government was "frightened" by the Ezhava threat of conversion to Christianity.<ref>{{cite book |title=Votes and Violence: Electoral Competition and Ethnic Riots in India |first=Steven I. |last=Wilkinson |publisher=Cambridge University Press |year=2006 |edition=Reprinted |orig-year=2004 |isbn=978-0-521-53605-9 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=tLpRFbLSxvAC&pg=PA179 |page=179}}</ref> | |||

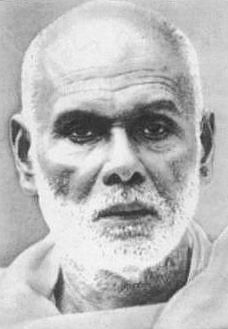

| ], a prophet, and social reformer of the early 20th century, paved the way for improvement in the spiritual freedom and other social conditions of the Ezhava and related communities in Kerala and other parts of the country. Also the Ezhava community's largely undisputed acceptance of ] as their spiritual, social and intellectual mentor and guiding spirit adds a major and unifying facet to community integrity and identity today. <ref name = "ezh5">NR Krishanan IAS, Izhavar Annum Innum</ref><ref name="ezh7">{{cite web|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=xNAI9F8IBOgC&pg=PA35&ots=ICjcuHwMf0&dq=narayana+guru+books&sig=0Mprz7a4NasyhqnlsrrHxAciIJk|title=Religion and Social Conflict in South Asia|work=Bardwell L. Smith|publisher=BRILL|accessdate=2007-08-08}}</ref> The community has prospered thanks to the pioneering efforts of by the community leaders. They are classified under OBC (Other backward castes), and enjoy the privileges of reservations of jobs in Government service, and in admission to Educational Institutions for financially backward students.<ref name = "ezh31"> Cyriac K. Pullapilly, The Izhavas of Kerala and their Historic Struggle for Acceptance in the Hindu Society</ref> | |||

| Eventually, in 1903, a small group of Ezhavas, led by Palpu, established ], the first caste association in the region. This was named after ], who had established an ] from where he preached his message of "one caste, one religion, one god" and a Sanskritised version of the Victorian concept of self-help. His influence locally has been compared to that of ].<ref name="Nossiter1982pp30-32" /> One of the initial aims of the SNDP was to campaign for the removal of the restrictions on school entry but even after those legal barriers to education were removed, it was uncommon in practice for Ezhavas to be admitted to government schools. Thus, the campaign shifted to providing schools operated by the community itself.<ref name="Padmanabhan" /> The organisation, attracted support in Travancore but similar bodies in Cochin were less successful. In Malabar, which unlike Cochin and Travancore was under direct British control,<ref name="SchneiderGoughp304">{{cite book |title=Matrilineal Kinship |editor1-first=David Murray |editor1-last=Schneider |editor2-first=E. Kathleen |editor2-last=Gough |chapter=Nayars: Central Kerala |first=E. Kathleen |last=Gough |page=304 |year=1961 |publisher=University of California Press |isbn=978-0-520-02529-5 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=lfdvTbfilYAC&pg=PA304}}</ref> the Ezhavas showed little interest in such bodies because they did not suffer the educational and employment discrimination found elsewhere, nor indeed were the disadvantages that they did experience strictly a consequence of caste alone.<ref name="Nossiter1982pp30-32">] pp. 30–32</ref> | |||

| When in 1896 a ''Ezhava Memorial'' signed by more than 13,000 representative ezhavas of ] was submitted to the government praying for the recognition of the right of the Ezhavas to enter the government service, the upper caste Hindus of the state prevailed upon the Maharajah not to concede the request. And when their fight for equity was not taking the Ezhavas anywhere, their leadership threatened that they would convert en masse, rather than stay as helots of ] society. The alert ], Sir C.P. Ramaswamy Iyer, realised the imminent danger and prompted the ] to issue ]. <ref name = "ezh28"> Dr. Palpu, Treatment of Tiyas in Travancore </ref> | |||

| The Ezhavas were not immune to being manipulated by other people for political purposes. The ] of 1924–1925 was a failed attempt to use the issue of ] access to roads around temples in order to revive the fortunes of ], orchestrated by ], a revolutionary and civil rights activist,<ref name="Smith1976p38">] p. 38</ref> and with a famous temple at ] as the focal point. Although it failed in its stated aim of achieving access, the ] (movement) did succeed in voicing a "radical rhetoric", according to Nossiter.<ref name="Nossiter1982pp30-32"/> During this movement, a few ]{{mdash}}an order of armed ]s{{mdash}}came to Vaikom in support of the demonstrators. After the eventual passing of the Temple Entry Proclamation, some of the Akalis remained. They attracted some Ezhava youth to the concepts of the Sikhism, resulting in Ezhava conversions to that belief.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=C8EBAAAAMAAJ&q=sikhism+ezhava|title= The abstention movement|page=19|first=K.K |last=Kusuman|publisher=Kerala Historical Society |year=1976|access-date=2011-06-15}}</ref> | |||

| The ] (1924 - 25) was a ] (movement) in ] against ] in ] society. The movement was centered at the ] temple at ], near ]. The Satyagraha aimed at securing freedom of movement for all sections of society through the public roads leading to the Sri Mahadevar Temple at Vaikom. The ezhava community and SNDP Yogam were in the forefront of this successful movement. | |||

| Between the Travancore census of 1875 and 1891, the literacy of Ezhava men had been increased from 3.15 percent to 12.1 percent. The 1891 census showed that there were at least 25000 educated Ezhavas in Travancore<ref>''The Decline of Nair Dominance: Society and Politics in Travancore 1847-1908'', Robin Jeffrey, Manohar Classics. p. 187-190</ref> Dr. Palpu had support from Parameswaran Pillai who was editing the Madras Standard. He raised the issue of the rights of Ezhavas in a speech at the National Conference in Pune in 1885, which was also editorialized in the Madras Standard. Pillai and Dr. Palpu also raised their questions regarding Ezhavas in the House of Commons in England in 1897. Palpu met with Swamy Vivekanda in Mysore and discussed the conditions of Ezhavas. Vivekanda has advised him to unite the Ezhava community under the leadership of a spiritual leader. He embraced this advice and associated with Sree Narayana Guru and formed the Sree Narayana Dharma Paripalana Yogam (S.N.D.P), registered in March 1903.<ref>''The Decline of Nair Dominance: Society and Politics in Travancore 1847-1908'', Robin Jeffrey, Manohar Classics. p. 187-190</ref> By mid 1904, the emerging S.N.D.P Yogam, operating a few schools, temples, and a monthly magazine announced that it would hold an industrial exhibition with its second annual general meeting in Quilon in January 1905. The exhibition was skillful and successful and was a sign of the awakening Ezhava community. | |||

| ==Religious Conversions== | |||

| <ref>''The Decline of Nair Dominance: Society and Politics in Travancore 1847-1908'', Robin Jeffrey, Manohar Classics. p. 187-190</ref> | |||

| The success of the SNDP in improving the lot of Ezhavas has been questioned. Membership had reached 50,000 by 1928 and 60,000 by 1974, but Nossiter notes that, "From the Vaikom ''satyagraha'' onwards the SNDP had stirred the ordinary Ezhava without materially improving his position." The division in the 1920s of {{cvt|60000|acre|ha}} of properties previously held by substantial landowners saw the majority of Ezhava beneficiaries receive less than one acre each, although 2% of them took at least 40% of the available land. There was subsequently a radicalisation and much political infighting within the leadership as a consequence of the effects of the ] on the ] industry but the general notion of self-help was not easy to achieve in a primarily agricultural environment; the Victorian concept presumed an industrialised economy. The organisation lost members to various other groups, including the Communist movement, and it was not until the 1950s that it reinvented itself as a pressure group and provider of educational opportunities along the lines of the ] (NSS), Just as the NSS briefly formed the National Democratic Party in the 1970s in an attempt directly to enter the political arena, so too in 1972 the SNDP formed the Social Revolutionary Party.<ref name="Nossiter1982pp30-32"/> | |||

| During different periods of history, sections of the Ezhava community converted to other religions. | |||

| ==Position in society== | |||

| ===Conversion to Christianity=== | |||

| They were considered as ''avarna'' (outside brahmanical varna system) by the Nambudiri Brahmins who formed the Hindu clergy and ritual ruling elite in late medieval Kerala.<ref name="Nossiter1982p30"/> ] says that the Ezhavas of Central Travancore were historically the highest-ranking of the "higher polluting castes", a group whose other constituents included ]s and various artisanal castes, and who were all superior in status to the "lower polluting castes", such as the ]s and ]s. The Nairs and, where applicable, the Mapillas ranked socially and ritually higher than the polluting castes.<ref name="Gough313">{{cite book |title=Matrilineal Kinship |editor1-first=David Murray |editor1-last=Schneider |editor2-first=E. Kathleen |editor2-last=Gough |chapter=Nayars: Central Kerala |first=E. Kathleen |last=Gough |author-link=Kathleen Gough |pages=312–313 |year=1961 |publisher=University of California Press |isbn=978-0-520-02529-5 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=lfdvTbfilYAC&pg=PA312}}</ref>{{efn|Kathleen Gough says of the Mappillas that they "... lived mainly in the ports and at inland trading posts on the banks of rivers. They were partly outside the village ranking system ... and were theoretically outside the Hindu religious hierarchy. Nevertheless Muslims were in some contexts accorded a rank ritually and socially between that of the Nayars and Tiyyars."<ref name="Gough313" />}} From their study based principally around one village and published in 2000, the Osellas noted that the movements of the late 19th- and 20th centuries brought about a considerable change for the Ezhavas, with access to jobs, education and the right to vote all assisting in creating an identity based on more on class than caste, although the stigmatic label of ''avarna'' remained despite gaining the right of access to temples.<ref>{{cite book |title=Social Mobility in Kerala: Modernity and Identity in Conflict |first1=Filippo |last1=Osella |first2=Caroline |last2=Osella |publisher=Pluto Press |year=2000 |isbn=978-0-7453-1693-2 |pages=16, 29 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=rMRw0gTZSJwC&pg=PA16}}</ref> | |||

| A sizeable part of the Ezhava community, especially in central ] and in the High Ranges, embraced ] during the ], due to caste-based discrimination. In ], ] missions started working in the first half of the 19th century, when the Basel German Evangelical Mission was founded by Dr. H.Gundert. Most of their converts were from the Thiyya community. The ''Ezhava Memorial'' was a plea that contained 13,000 signatures and requested an extension of civic rights, Government jobs, etc. to the lower castes. The Memorial was also an ultimatum given to the government, which said that the Ezhavas would convert en masse if it was not implemented{{fact|date=October 2007}}. ] decried the conversion since he said that they were made for materialistic or temporary benefits, convenience, or as an escape from discrimination and religious persecution. These principles formed the criteria for his support of conversions and re-conversions. For example, a family of the Kannoor community converted to Christianity for certain benefits, but not out of any change of belief. After some time this family desired to convert back, but their previous community opposed this re-conversion. Narayana Guru intervened and asked all the family and community leaders concerned to take back the family into the community. His arguments were convincing, and an amicable return was effected. In Neyyatinkara, there were some families who converted to Christianity due to the discrimination and religious persecution existing at that time against the lower strata of Hindus. But after witnessing the progress made due to the work of Narayana Guru and his disciples, these families wanted to convert back to ]. Again, the opposition of their community was overcome, and Narayana Guru happily converted them back. <ref name = "ezh27"> Surendra Kumar Srivastava and Akhileshwar Lal Srivastava, Social Movements for Development (Chugh Publications, 1988, ISBN 8185076340), Page 167</ref> | |||

| The Ezhavas are classified as an ] by the ] under its ].<ref name="obc">{{cite web|title=Central List of OBCs: Kerala|url=http://ncbc.nic.in/User_Panel/GazetteResolution.aspx?Value=mPICjsL1aLvX4YwLqUBC2NUPs1mZbhKbKhWJfmW%2b7ZgXWaQGOVNjwfOOnQuzOlde|publisher=National Commission for Backward Classes, Government of India|access-date=2017-04-16}}</ref> | |||

| In the village of Vazhappalli, near ], there were a limited number of families of a community known as Pichanaattu ] were facing discrimination from the upper castes do to their perceived low position in the social stratum. Although they were allowed entry into the temples and adjacent roads, the Hindu communities at the higher end of the social stratum did not accept them.{{unclear}} This, coupled with the limited number of members in their own community, made it difficult for them to function socially, and they faced increasing isolation.{{unclear}} Finally, the leader of this group, Mr. Krishnan ], converted to Christianity. ], a disciple of ], informed the saint of the situation. Panicker requested that the ''Pichanaattu Kuruppanmar'' should be better integrated into the community so that such conversions could be avoided in the future. ] accepted this proposal, and personally accepted the ''Pichanaattu Kuruppanmar'' into the community at a large public meeting which included leaders of other religious groups. <ref name = "ezh27"> Surendra Kumar Srivastava and Akhileshwar Lal Srivastava, Social Movements for Development (Chugh Publications, 1988, ISBN 8185076340), Page 167</ref> | |||

| ==Dispute between different Ezhava communities== | |||

| In 1921 an extensive effort to reach a thousand Ezhava Families living in the coastal areas of ] and hilly area of ] was initiated by an independent committee, in relation with the ] church. With Miss Isabel Baker's (CMS Missionary) generous contribution, a school, hospital and a ] factory were established under the title ''Karappuram Mission'' in the Shertellai area and as a result, thousands of Ezhava Families were converted in areas of ] and ] to Christianity.<ref name = "ezh27"> Surendra Kumar Srivastava and Akhileshwar Lal Srivastava, Social Movements for Development (Chugh Publications, 1988, ISBN 8185076340), Page 167</ref> | |||

| Some in the Ezhava community in Malabar have objected to being treated as Ezhava by the government of Kerala, arguing that the Ezhava in Malabar (locally known as Thiyyar) are a separate caste. They have campaigned for the right to record themselves as Thiyya rather than as Ezhava when applying for official posts and other jobs allocated under India's system of positive discrimination. They claim that the stance of the government is contrary to a principle established by the ] relating to a dispute involving communities who were not Ezhava.<ref>{{cite news |publisher=News 18 |title=Thiyyas to move SC against Government order |date=23 January 2012 |first=Kalathil |last=Ramakrishnan |url=https://www.news18.com/news/india/thiyyas-to-move-sc-against-government-order-439733.html |access-date =18 June 2019}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |newspaper=The Hindu|date=23 May 2012 |title=Plea to lower minimum qualification for jobs |url=http://www.thehindu.com/todays-paper/tp-national/tp-kerala/plea-to-lower-minimum-qualification-for-jobs/article3447946.ece |access-date=28 March 2013}}</ref> The Thiyya Mahasabha (a sub-group of the Ezhava in Malabar) has also opposed the SNDP's use of the Thiyya name at an event.<ref>{{cite news |newspaper=The Hindu|url=http://www.thehindu.com/todays-paper/tp-national/tp-kerala/thiyya-forum-lashes-out-at-sndp/article4349866.ece |date=27 January 2013 |title=Thiyya forum lashes out at SNDP |access-date=9 March 2013}}</ref> | |||

| In February 2013, the recently formed Thiyya Mahasabha objected to the SNDP treating Ezhavas and Thiyyas as one group, rather than recognising the Thiyyas in Malabar as being distinct. The SNDP was at that time attempting to increase its relatively weak influence in northern Kerala, where the politics of identity play a lesser role than those of class and the ] has historically been a significant organisation.<ref>{{cite news |newspaper=The Hindu|date=1 February 2013 |title=Ezhava-Thiyya convention in Kozhikode |url=http://www.thehindu.com/todays-paper/tp-national/tp-kerala/ezhavathiyya-convention-in-kozhikode/article4367837.ece |access-date=28 March 2013}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |publisher=The New Indian Express |date=1 February 2013 |title=SNDP out to make a dent in CPM citadels in Malabar |url=http://newindianexpress.com/states/kerala/article1444651.ece |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140521131832/http://www.newindianexpress.com/states/kerala/article1444651.ece |url-status=dead |archive-date=21 May 2014 |access-date=28 March 2013}}</ref> | |||

| ===Conversion to Sikhism in central Kerala=== | |||

| {{seealso|Sikhism}} | |||

| {{unsourced-section}} | |||

| During ] in 1922, at the instance of ], a few ]s came to ] in support of the demonstrators. After successful the completion of the ] and after the ], some of the Akalis remained. Some Ezhava youth were attracted to the concepts of the Sikhism and as a result, joined the religion. Many Ezhavas were also prompted to join ] after ]'s remarks which said that if you didn't receive respect in your own religion, you should get out of it. However, after the significant growth of the Ezhava movement, many families later re-converted to Hinduism and hence the number of Sikh Ezhavas dwindled. | |||

| == |

==See also== | ||

| *] | |||

| Ezhavas do not normally use any distinct surnames. However, occupational surnames like ], ], ], ], ''Mudalali'', ], ], ], ''chekon'', valiyachan, achan, chanatty, panikkathy, chekothy, thanpatty, ], karanavar, kutty, ](Mostly in ]), ] and to some extend ], were fairly common till the early 20th century {{ref|Alumoottil}}. ],], ] is still being used by Ezhavas in south Kerala. Some of these surnames like ], ], ''Mudalali'', ], valiyachan, achan, Amma were also used by some of the ] and ] communities of ]. | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| ==Notes== | |||

| ==Similar Communities== | |||

| {{notelist}} | |||

| ===Billavas=== | |||

| ] is a name of the caste found mainly in costal ] and ] District of ]. They were engaged in Martial Arts (Garadi), Toddy tapping, Ayurvedic and liquor business. This community is starting to follow ]'s teachings. | |||

| ==Poojari== | |||

| ] is a sub-sect of ] community of ] district in ], a south Indian state. They had very important role in ] or ] which is a kind of spirit-worship. This sub-sect of Billava community performs the ''Pooja'' activity during spirit-worship. | |||

| ==Selected List of Famous Ezhavas== | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ===Spiritual Leaders=== | |||

| *] | |||

| *Sree Malayalaswami of ], a disciple of Narayana Guru | |||

| *Guru ] (His name in the Purvashrama was Jayachandran Panicker) | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *Bhikshu ] | |||

| *] (Founder of Santhigiri Ashram) | |||

| * Brahmashri ] | |||

| *] | |||

| ] | |||

| ===Social reformers=== | |||

| * Sree Malayalaswami of ] , a disciple of ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * Mahakavi ] Poet and Social reformer | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] Leader of Sree Narayan Movement and community | |||

| * ] Great poet and a prominent social reformer | |||

| * ] Founder of ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] Freedom Fighter - Mahe | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] Yogam]] | |||

| ===Writers and Poets=== | |||

| *] | |||

| *] Founder of ]. | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| * Mahakavi ] | |||

| *] Disciple of ] from ]. | |||

| *] was associate editor of ], | |||

| *] IAS (Retd). Follower of ]. | |||

| *] ] Award winner for Oru Desathinte Katha | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| * Dr ] Eminent anthropologist, former Vice Chancellor of Kerala University | |||

| *Prof ] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] Writer | |||

| *] Noted writer and Kendra sahithya akadami award winner | |||

| *] | |||

| *] Noted critic | |||

| *] The Kathaprasangam Supremo | |||

| ===SNDP Yogam leaders=== | |||

| * Dr. P ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] Former SNDP Yogam General Secretary | |||

| * Mahakavi ] Former SNDP Yogam General Secretary | |||

| * ] Former SNDP Yogam President | |||

| * ] SNDP Yogam General Secretary | |||

| ===Artistes=== | |||

| ====Direction, Screenplay, Script Writing, Production==== | |||

| *] Film director, directed president's gold medal-winning film ''Chemmeen'' | |||

| *] Famous Hollywood writer director of movies like ''The Sixth Sense'', ''Unbreakable'', ''Signs'' and ''The Village'' | |||

| *] Great drama director | |||

| *] Film director | |||

| *] Film director | |||

| *]Top-Ranking Action Film director | |||

| *] Famous cinematographer director of many award-winning films | |||

| *] Actor, writer and director | |||

| *] Film director | |||

| *] Film maker and famous sculpturer | |||

| *] Serial Director | |||

| *] Film Director | |||

| *]Great drama director | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ====Acting==== | |||

| *] actor, director | |||

| *] Famous Film actor | |||

| *] Film actor | |||

| *] Film actor | |||

| *] Film actres | |||

| *] Film and TV actress | |||

| *] Model, Film and TV actress and Sister of ] | |||

| *] Film actor | |||

| *] Film actor | |||

| *] Film actress | |||

| *] Film actress | |||

| *] | |||

| *] Actor | |||

| *] Noted actor and politician | |||

| *] Film actress of 1970s | |||

| * Late ] | |||

| *] Malayalam actor | |||

| *] Film Actor | |||

| *] | |||

| ====Music==== | |||

| *] | |||

| *] Famous music director | |||

| *], musicians | |||

| *] Play back singer | |||

| *] Play back singer | |||

| *] Top Play back Singer | |||

| ] | |||

| ===Political leaders=== | |||

| *] Chief Minister of Kerala | |||

| *] Former Chief Minister of Kerala | |||

| *] Former Chief minister of ] | |||

| *] Freedom fighter, Congress leader and ex-MLA and former President of Thiru-kochi Pradesh Congress Committee. | |||

| *] ] leader and Union ] | |||

| *] Former Home Minister and Opposition Leader of Kerala | |||

| *] Politbureau Member of CPM | |||

| *] Politbureau Member of CPM | |||

| *] INC leader | |||

| *] RSP leader and Former Minister of Kerala | |||

| *] Founder leader of JSS and Former Minister | |||

| *] Former ] Minister of Kerala | |||

| *] Former ] Minister of Kerala | |||

| *] President, CPI | |||

| *] Former Industry Minister of Kerala | |||

| ] | |||

| ===Other famous people=== | |||

| *], Famous astrophysicist. | |||

| *] | |||

| *] Cricket Player. His mother is an Ezhava from ]. | |||

| *] Former Olympian | |||

| *] | |||

| ===Business figures=== | |||

| *] One of the Founders of ] | |||

| *] Chairman of Kerala Transport Company and PVS Hospitals and Managing Editor of ] | |||

| *] Founder of Cholayil Pharma, famous for Medimix, Cuticura | |||

| *] Founder of ] Soaps. | |||

| *] Chairman & Founder of www.rediff.com | |||

| ===Journalists=== | |||

| *] Founder Editor, ] | |||

| *] Columnist Rediff | |||

| *] Chief Editor ] | |||

| *] Noted Dubai-based business journalist and columnist | |||

| *] associate editor ]. | |||