| Revision as of 17:52, 6 December 2007 editChills42 (talk | contribs)243 edits reverting to last good version← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 19:01, 11 January 2025 edit undoPharaohCrab (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users955 edits →forms of Horus: added images to gallery | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Egyptian war and sky deity}} | |||

| {{Citations missing|date=December 2006}} | |||

| {{about|the ancient Egyptian deity|the Roman poet|Horace|other uses|Horus (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{redirect|Ihy||International Heliophysical Year}} | |||

| {{Infobox deity | |||

| {{otheruses}} | |||

| | type = Egyptian | |||

| | name = Horus | |||

| | image = Horus (based on reliefs).svg | |||

| | alt = | |||

| ]]] | |||

| | caption = Horus was often the ancient Egyptians' national ]. He was usually depicted as a falcon-headed man wearing the '']'', or a red and white crown, as a symbol of kingship over the entire kingdom of ]. | |||

| | cult_center = ], ]<ref>{{cite book|last=Sims|first=Lesley|title=A Visitor's Guide to Ancient Egypt|url=https://archive.org/details/visitorsguidetoa00lesl|url-access=registration|date=2000|chapter=Gods & goddesses|location=Saffron Hill, London|publisher=]|page=|isbn=0-7460-30673}}</ref> | |||

| | symbol = ] | |||

| | parents = ] and ], ] and ],<ref name="Lévai 2007">{{Cite book|last=Lévai|first=Jessica|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=C7vTAQAACAAJ&q=levai+jessica+aspects+of+nephthys|title=Aspects of the Goddess Nephthys, Especially During the Graeco-Roman Period in Egypt|date=2007|publisher=UMI|language=en|access-date=2021-11-17|archive-date=2023-04-03|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230403005225/https://books.google.com/books?id=C7vTAQAACAAJ&q=levai+jessica+aspects+of+nephthys|url-status=live}}</ref> ]<ref>{{Cite book|last=Najovits|first=Simson R.|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Y72qrAmKcfEC&dq=%22hathor%22+%22mother+and+wife+of%22&pg=PA27|title=Egypt, Trunk of the Tree, Vol. I: A Modern Survey of and Ancient Land|date=2003|publisher=Algora Publishing|isbn=978-0-87586-234-7|language=en|access-date=2021-11-17|archive-date=2023-04-03|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230403005225/https://books.google.com/books?id=Y72qrAmKcfEC&dq=%22hathor%22+%22mother+and+wife+of%22&pg=PA27|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| | siblings = ],{{efn|In some accounts.}} ]{{efn|Rarely attested.}} | |||

| | consort = ], ], ]<ref name="Gods, Goddesses, and Mythology, Volume 4">{{cite book |last= Littleson|first= C. Scott|date= 2005|title= Gods, Goddesses, and Mythology, Volume 4|publisher= Marshall Cavendish|isbn= 076147563X}}</ref> ]<ref name="Lévai 2007"/> ]<ref>{{cite book |last1=Pinch |first1=Geralidine |title=Handbook of Egyptian Mythology |date=2002 |publisher=] |isbn=9781576072424 |pages=145 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=N-mTqRTrimgC&q=ta-bitjet |access-date=18 July 2020}}</ref> | |||

| | offspring = ], ] (Horus the Elder) | |||

| | greek_equivalent = ] | |||

| | hiero = <hiero>G5</hiero> | |||

| | equivalent1 = ] | |||

| | equivalent1_type = Nubian | |||

| }} | |||

| '''Horus''' ({{IPAc-en|h|ɔː|ɹ|ə|s}}),{{efn|{{langx|grc|Ὧρος|translit=Hō̂ros}}, {{IPA|grc|hɔ̂ː.ros}}; {{langx|la|Hōrus}}, {{IPA|la|hoː.rus}}}} also known as '''Heru''', '''Har''', '''Her''', or '''Hor''' ({{IPAc-en|h|ɔː|ɹ}}){{efn|{{langx|egy|ḥr}}; {{langx|cop|Ϩⲱⲣ|translit=Hōr}}, {{IPA|cop|hɔr}}}}<ref>{{Cite web |date=2023-07-05 |title=Horus {{!}} Story, Appearance, Symbols, & Facts {{!}} Britannica |url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/Horus |access-date=2023-08-02 |website=www.britannica.com |language=en}}</ref> in ], is one of the most significant ] who served many functions, most notably as the god of kingship, healing, protection, the sun, and the sky. He was worshipped from at least the late ] until the ] and ]. Different forms of Horus are recorded in history, and these are treated as distinct gods by ].<ref name="oxford">"The Oxford Guide: Essential Guide to Egyptian Mythology", Edited by Donald B. Redford, Horus: by Edmund S. Meltzer, pp. 164–168, Berkley, 2003, {{ISBN|0-425-19096-X}}.</ref> These various forms may be different manifestations of the same multi-layered deity in which certain attributes or ] relationships are emphasized, not necessarily in opposition but complementary to one another, consistent with how the Ancient Egyptians viewed the multiple facets of reality.<ref>"The Oxford Guide: Essential Guide to Egyptian Mythology", Edited by Donald B. Redford, p106 & p165, Berkley, 2003, {{ISBN|0-425-19096-X}}.</ref> He was most often depicted as a ], most likely a ] or ], or as a man with a falcon head.<ref>Wilkinson, Richard H. (2003). ''The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt''. Thames & Hudson. p. 202.</ref> | |||

| The earliest recorded form of Horus is the ] of ] in ], who is the first known national god, specifically related to the ruling ] who in time came to be regarded as a manifestation of Horus in life and ] in death.<ref name="oxford"/> The most commonly encountered family relationship describes Horus as the son of ] and Osiris, and he plays a key role in the ] as Osiris's heir and the rival to ], the murderer and brother of Osiris. In another tradition, ] is regarded as his mother and sometimes as his wife.<ref name="oxford"/> | |||

| '''Horus''' is one of the most ancient deities of the ], who appears in his earliest form in late ]. Represented as a falcon, his name is believed to mean 'the high' or 'the far off'<ref name="horus1">''The Routledge Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses''. Routledge, Oxford and New York, 2005. Edited by George Hart. 2nd Edition, Page 70.</ref> and his earliest connections are to the sky and ''kingship'', derived from being the son of ] or ], as a sun god. Because the cult of Horus survived for the whole of the Ancient Egyptian civilization that extended for thousands of years, he gained many forms and associations. | |||

| ] wrote that Egyptians called the god ] "Horus" in their own ].<ref>{{cite web| url = https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=urn:cts:greekLit:tlg0545.tlg001.perseus-grc1:10.14| title = Aelian, Characteristics of Animals, 10.14| access-date = 2021-02-20| archive-date = 2020-08-06| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20200806113141/http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=urn:cts:greekLit:tlg0545.tlg001.perseus-grc1:10.14| url-status = live}}</ref> However, ], elaborating further on the same tradition reported by the ], specified that the one "Horus" whom the Egyptians equated with the Greek Apollo was in fact "Horus the Elder", a primordial form of Horus whom Plutarch distinguishes from both Horus and Harpocrates.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/e/roman/texts/plutarch/moralia/isis_and_osiris%2A/a.html%3Cbr%3EPlutarch |title=- Moralia, ''De Iside et Osiride'' (Isis and Osiris), 12. (356A). |access-date=2022-08-16 |archive-date=2023-04-03 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230403005325/http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/home.html |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Horus was usually represented as a man with a falcon's head. One important association is the '']'' which was an Egyptian symbol of power (first identified with ] and seen on images of his mother, ], as she was emerging from the reeds) and of the offerings made to the god ] and by extension, to all of the dead. In one myth cycle Horus' left eye is injured during his struggle with his uncle ], who had murdered ] in an attempt to seize the Egyptian throne. The ], its injury, and subsequent restoration became an important symbol for the unified land of Egypt and in the funerary rites of the renewal after death. | |||

| == |

==Etymology== | ||

| Horus is recorded in ] as ''ḥr.w'' "Falcon", 𓅃; the original pronunciation has been reconstructed as {{IPA|/ˈħaːɾuw/}} in ] and early ], {{IPA|/ˈħaːɾəʔ/}} in later ], and {{IPA|/ˈħoːɾ(ə)/}} in ]. Additional meanings are thought to have been "the distant one" or "one who is above, over".<ref>Meltzer, Edmund S. (2002). Horus. In D. B. Redford (Ed.), ''The ancient gods speak: A guide to Egyptian religion'' (pp. 164). New York: ], USA.</ref> As the language changed over time, it appeared in ] variously as {{IPA|/hɔr/}} or {{IPA|/ħoːɾ/}} (Ϩⲱⲣ) and was adopted into ] as {{lang|grc|Ὧρος}} ''Hō̂ros'' (pronounced at the time as {{IPA|/hɔ̂ːros/}}). It also survives in ] and Coptic ] forms such as ] | |||

| {{Hiero|ḥr "Horus"<br>|<hiero>G5</hiero>|align=right|era=egypt}}Horus is recorded in ] as {{unicode|ḥr.w}} and is reconstructed to have been pronounced *{{unicode|Ḥāru}}, meaning "Falcon". By ] times, the name became ''Hōr''.It was adopted into ] as {{Polytonic|Ὡρος}} ''Hōros''. The original name also survives in later Egyptian names such as ] literally "Horus, son of ]".<ref></ref> | |||

| "son of Isis" and ] "Horus, Son of Isis". | |||

| == |

== Horus and the pharaoh == | ||

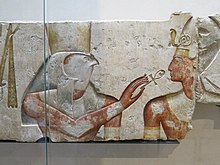

| ] to the pharaoh, ]. Painted limestone. {{Circa|1275 BCE}}, 19th dynasty. From the small temple built by Ramses II in ], ], Paris, France.|left]] | |||

| === Sky god === | |||

| The ] was associated with many specific deities. He was identified directly with Horus, who represented kingship itself and was seen as a protector of the pharaoh,<ref name=":2">{{Cite book |last1=Pearson |first1=Patricia O'Connell |title=World History: Our Human Story |last2=Holdren |first2=John |date=May 2021 |publisher=Sheridan Kentucky |isbn=978-1-60153-123-0 |location=Versailles, Kentucky |pages=29}}</ref> and he was seen as the son of Ra, who ruled and regulated nature as the pharaoh ruled and regulated society. | |||

| This is thought to be the original form of Horus.<ref>The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt by Richard H. Wilkinson, Thames and Hudson, page 200.</ref> His name meaning 'high' or 'distant' reflects his sky nature. He was seen as a great falcon with outstretched wings whose right eye was the sun and the left one was the moon. | |||

| One of the sky-god forms of Horus was 'Nekheny' (meaning 'he of ]' or ]). | |||

| The ] ({{Circa|2400–2300 BCE}}) describe the nature of the pharaoh in different characters as both Horus and Osiris. The pharaoh as Horus in life became the pharaoh as Osiris in death, where he was united with the other gods. New incarnations of Horus succeeded the deceased pharaoh on earth in the form of new pharaohs.<ref>{{cite book|last=Allen|first=James P.|author-link=James Peter Allen|title=The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6VBJeCoDdTUC&pg=PA1|year=2005|publisher=Society of Biblical Literature|isbn=978-1-58983-182-7}}</ref>{{Ancient Egyptian religion}}The lineage of Horus, the eventual product of unions between the children of ], may have been a means to explain and justify pharaonic power. The gods produced by Atum were all representative of cosmic and terrestrial forces in Egyptian life. By identifying Horus as the offspring of these forces, then identifying him with Atum himself, and finally identifying the Pharaoh with Horus, the Pharaoh theologically had dominion over all the world. | |||

| === Sun god === | |||

| {{Hiero|ḥr.w "Horus" <br>|<hiero>H-Hr:r</hiero>|align=right|era=egypt}} | |||

| Since Horus was said to be the sky, it was natural that he soon was considered also to contain the ] and ]. It became said that the sun was one of his eyes and the moon the other, and that they traversed the sky when he, a falcon, flew across it. Thus he became known as '''Harmerty''' - ''Horus of two eyes''. Later, the reason that the moon was not so bright as the sun was explained by a new tale, known as the ''contestings of Horus and Set'', originating as a metaphor for the conquest of ] by ] in about 3000 B.C. In this tale, it was said that ], the patron of Upper Egypt, and Horus, the patron of Lower Egypt, had battled for Egypt brutally, with neither side victorious, until eventually the deities sided with Horus. | |||

| == Origin mythology == | |||

| ], the cobra sun deity, as a crown - typically the symbol remains, but the names of the deities performing the function change as new cults arise]] | |||

| In one tale, Horus is born to the goddess Isis after she retrieved all the dismembered body parts of her murdered husband Osiris, except his ], which was thrown into the Nile and eaten by a ]/],<ref>{{Cite news|title=New York folklore quarterly|author=New York Folklore Society|publisher=]|year=1973|volume=29|page=294|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=92LYAAAAMAAJ&q=penis|access-date=2020-11-12|archive-date=2023-04-03|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230403005327/https://books.google.com/books?id=92LYAAAAMAAJ&q=penis|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|title=The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt|author=Ian Shaw|author-link=Ian Shaw (Egyptologist)|publisher=Oxford University Press|year=2003|isbn=978-0-19-815034-3|url-access=registration|url=https://archive.org/details/oxfordhisto00shaw}}</ref> or sometimes depicted as instead by a ], and according to ]'s account used her magic powers to ] Osiris and fashion a ]<ref>{{cite book|title=Eunuchs and castrati: a cultural history|author=Piotr O. Scholz|publisher=Markus Wiener Publishers|year=2001|page=32|isbn=978-1-55876-201-5|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=N90jBg01ZI0C&q=horus+isis+osiris+penis&pg=PA32|access-date=2020-11-12|archive-date=2023-04-03|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230403015330/https://books.google.com/books?id=N90jBg01ZI0C&q=horus+isis+osiris+penis&pg=PA32|url-status=live}}</ref> to conceive her son (older Egyptian accounts have the penis of Osiris surviving). | |||

| As Horus was the ultimate victor he became known as '''Harsiesis''', '''Heru-ur''' or '''Har-Wer''' ({{unicode|ḥr.w wr}} 'Horus the Great'), but more usually translated as '''Horus the Elder'''. In the struggle Set had lost a ], explaining why the ], which Set represented, is ]. Horus' left eye also had been gouged out, which explained why the moon, which it represented, was so weak compared to the sun. It also was said that during a new-moon, Horus had become blinded and was titled '''Mekhenty-er-irty''' ({{unicode|mḫnty r ỉr.ty}} 'He who has no eyes'), while when the moon became visible again, he was re-titled '''Khenty-er-irty''' ({{unicode|ḫnty r ỉr.ty}} 'He who has eyes'). While blind, it was considered that Horus was quite dangerous, sometimes attacking his friends after mistaking them for enemies. | |||

| After becoming pregnant with Horus, Isis fled to the ] ]lands to hide from her brother ], who jealously killed Osiris and who she knew would want to kill their son.<ref name="World mythology">{{cite book|title=World Mythology|author=Roy G. Willis|publisher=Macmillan|year=1993|page=43|isbn=978-0-8050-2701-3|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ojccFpRU8DwC&q=horus&pg=PA44|access-date=2020-11-12|archive-date=2023-04-03|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230403005325/https://books.google.com/books?id=ojccFpRU8DwC&q=horus&pg=PA44|url-status=live}}</ref> There Isis bore a divine son, Horus. As birth, death and rebirth are recurrent themes in Egyptian lore and cosmology, it is not particularly strange that Horus also is the brother of ] and ], by ] and ], together with ] and ].{{tone inline|date=July 2022}} This elder Horus is called Hrw-wr - Hourou'Ur - as opposed to Hrw-P-Khrd - the child Horus, at some point adopted by the Greeks as ].{{citation needed|date=July 2022}} | |||

| {{Hiero|rˁ-ˁḫr-3iḫṯ "<br>Re-Harachte"<br>|<hiero>G9</hiero>|align=left|era=egypt}} | |||

| ] pillar in the center, flanked by Horus on the left and ] on the right in this ] statuette]] | |||

| Ultimately, as another sun god, Horus became identified with ] as '''Ra-Herakhty''' ''rˁ-ˁḫr-3iḫṯ'', literally ''Ra, who is Horus of the two horizons''. However, this identification proved to be awkward, for it made Ra the son of Hathor, and therefore a created being rather than the creator. And, even worse, it made Ra into Horus, who was the son of Ra, i.e. it made Ra his own son and father, in a standard sexually-reproductive manner, an idea that would not be considered comprehensible to the Egyptians until the Hellenic era. Consequently Ra and Horus never completely merged into a single falcon-headed sun god. | |||

| === Genealogy === | |||

| Nevertheless the idea of making the identification persisted as with most of the symbols used in ancient Egyptian religion, and Ra continued to be depicted as falcon-headed. Likewise, as Ra-Herakhty, in an allusion to the ] creation myth, Horus was occasionally shown in ] as a naked boy with a finger in his mouth sitting on a ] with his mother, Hathor. In the form of a youth, Horus was referred to as '''Neferhor'''. This is also spelled '''Nefer Hor''', '''Nephoros''' or '''Nopheros''' ({{unicode|nfr ḥr.w}}) meaning 'The Good Horus'. | |||

| {{chart/start}} | |||

| In an attempt to resolve the conflict in the myths, Ra-Herakhty was occasionally said to be married to ], which was said to be his shadow, having previously been ]'s shadow, before Atum was identified as Ra, in the form ''Atum-Ra'', and thus of Ra-Herakhty when Ra was also identified as a form of Horus. In much earlier myths Iusaaset, meaning: (the) great (one who) comes forth, was seen as the mother and grandmother of all of the deities. In the version of the Ogdoad creation myth used by the ] cult, Thoth created Ra-Herakhty, via an ], and so was said to be the ''father'' of ''Neferhor''. | |||

| {{chart | | | | | | | | | CHA |CHA=]<br/>God of the ]}} | |||

| {{chart | | | | | | |,|-|-|^|-|-|.| }} | |||

| {{chart | | | | | TEF |~|~|y|~|~| SHU |TEF=]|SHU=]|}} | |||

| {{chart | | | | | | |,|-|-|^|-|-|.| }} | |||

| {{chart | | | | | GEB |~|~|y|~|~| NUT |GEB=]|NUT=]|}} | |||

| {{chart |,|-|-|-|-|v|-|-|-|+|-|-|-|.| }} | |||

| {{chart | ISI |y| OSI | | NEP | | SET |ISI=]|OSI=]|NEP=]|SET=]|}} | |||

| {{chart | | | |!| }} | |||

| {{chart | | | HOR |~|~|~|HAT|HOR='''Horus'''|HAT=]|}} | |||

| {{chart/end}} | |||

| == Mythological roles == | |||

| {{Hiero|1=rˁ-ḥr-3ḫty "Ra-Horakhty" |2=<hiero>G9-N27:N27</hiero>|align=right|era=default}} | |||

| ], ']s' in his grasp ]] | |||

| Isis had ]' body returned to ] after his death; Set had retrieved the body of Osiris and dismembered it into 14 pieces which he scattered all over Egypt. Thus Isis went out to search for each piece which she then buried. This is why there are many tombs to Osiris. The only part she did not find in her search was the genitals of Osiris which were thrown into a river by Set. She fashioned a substitute penis after seeing the condition it was in once she had found it and proceeded to have intercourse with the dead Osiris which resulted in the conception of Horus the child.<ref>]. ''Adonis Attis Osiris: Studies in the History of Oriental Religion''. 1961.</ref> | |||

| === Sky god === | |||

| ], ]s in his grasp]] | |||

| ] | |||

| Since Horus was said to be the sky, he was considered to also contain the Sun and Moon.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.worldhistory.org/Horus/|title=Horus|work=]|access-date=2019-02-22|language=en|archive-date=2021-04-14|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210414134748/https://www.worldhistory.org/Horus/|url-status=live}}</ref> Egyptians believed that the Sun was his right eye and the Moon his left and that they traversed the sky when he, a falcon, flew across it.<ref name="Sgt Wilko">{{cite book |last1=Wilkinson |first1=Richard H. |title=Reading Egyptian Art: A Hieroglyphic Guide to Ancient Egyptian Painting and Sculpture |date=1992 |publisher=Thames & Hudson |page=186}}</ref> Later, the reason that the Moon was not as bright as the sun was explained by a tale, known as '']''. In this tale, it was said that Seth, the patron of ], and Horus, the patron of ], had battled for Egypt brutally, with neither side victorious, until eventually, the gods sided with Horus. | |||

| As Horus was the ultimate victor he became known as ''ḥr.w or'' "Horus the Great", but more usually translated as "Horus the Elder". In the struggle, Set had lost a ], and Horus' eye was gouged out. | |||

| Horus was occasionally shown in art as a naked boy with a finger in his mouth sitting on a ] with his mother. In the form of a youth, Horus was referred to as ''nfr ḥr.w'' "Good Horus", transliterated Neferhor, Nephoros or Nopheros (reconstructed as {{IPA|naːfiru ħaːruw}}). | |||

| ] or ''Wedjat'']] | |||

| The ] is an ancient Egyptian symbol of protection and royal power from deities, in this case from Horus or ]. The symbol is seen on images of Horus' mother, Isis, and on other deities associated with her. In the Egyptian language, the word for this symbol was "wedjat" (''wɟt'').<ref>Pommerening, Tanja, Die altägyptischen Hohlmaße (''Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur'', Beiheft 10), Hamburg, Helmut Buske Verlag, 2005</ref><ref>M. Stokstad, "Art History"</ref> It was the eye of one of the earliest Egyptian deities, ], who later became associated with ], ], and Hathor as well. Wadjet was a ] and this symbol began as her all-seeing eye. In early artwork, Hathor is also depicted with this eye.<ref>{{cite web|access-date=18 January 2015|archive-date=27 January 2010|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100127075746/http://www.hethert.org/ladyofthewest.html|title=Lady of the West|url=http://www.hethert.org/ladyofthewest.html|url-status=dead|website=hethert.org}}</ref> Funerary amulets were often made in the shape of the Eye of Horus. The Wedjat or Eye of Horus is "the central element" of seven "], ], ] and ]" bracelets found on the mummy of ].<ref name="Silverman">{{cite book |author-link=David P. Silverman| last=Silverman |first=David P. |chapter=Egyptian Art |title=Ancient Egypt |publisher=Duncan Baird Publishers |year=1997 |page=228}}</ref> The Wedjat "was intended to protect the king in the afterlife"<ref name="Silverman" /> and to ward off evil. Egyptian and Near Eastern sailors would frequently paint the symbol on the bow of their vessel to ensure safe sea travel.<ref>Charles Freeman, ''The Legacy of Ancient Egypt'', Facts on File, Inc. 1997. p. 91</ref> | |||

| Horus was also thought to protect the sky.<ref name=":2" /> | |||

| === Conflict between Horus and Set === | === Conflict between Horus and Set === | ||

| ] | |||

| By the ], the previous brief enmity between Set and Horus, in which Horus had ripped off one of Set's testicles, was revitalised as a separate tale. According to ], Set was considered to have been ] and is depicted as trying to prove his dominance by seducing Horus and then having ] with him. However, Horus places his hand between his thighs and catches Set's ], then subsequently throws it in the river, so that he may not be said to have been inseminated by Set. Horus then deliberately spreads his own semen on some ], which was Set's favorite food (the ] thought that lettuce was ]). After Set has eaten the lettuce, they go to the deities to try to settle the argument over the rule of Egypt. The deities first listen to Set's claim of dominance over Horus, and call his semen forth, but it answers from the river, invalidating his claim. Then, the deities listen to Horus' claim of having dominated Set, and call his semen forth, and it answers from inside Set.<ref></ref> In consequence, Horus is declared the ruler of Egypt. | |||

| Horus was told by his mother, Isis, to protect the people of Egypt from ], the god of the desert, who had killed Horus' father, Osiris.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.mnsu.edu/emuseum/prehistory/egypt/religion/godslist.html |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100604111722/https://www.mnsu.edu/emuseum/prehistory/egypt/religion/godslist.html |archive-date=4 June 2010 |title=The Goddesses and Gods of Ancient Egypt }}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.egyptianmyths.net/horus.htm|title=Ancient Egypt: the Mythology – Horus|website=egyptianmyths.net|access-date=2007-08-25|archive-date=2019-11-29|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191129234140/http://www.egyptianmyths.net/horus.htm|url-status=live}}</ref> Horus had many battles with Set, not only to avenge his father but to choose the rightful ruler of Egypt. In these battles, Horus came to be associated with Lower Egypt and became its patron. | |||

| ] | |||

| According to ''The Contendings of Horus and Seth'', Set is depicted as trying to prove his dominance by seducing Horus and then having ] with him. However, Horus places his hand between his thighs and catches Set's ], then subsequently throws it in the river so that he may not be said to have been inseminated by Set. Horus (or Isis herself in some versions) then deliberately spreads his semen on some ], which was Set's favourite food. After Set had eaten the lettuce, they went to the gods to try to settle the argument over the rule of Egypt. The gods first listened to Set's claim of dominance over Horus, and call his semen forth, but it answered from the river, invalidating his claim. Then, the gods listened to Horus' claim of having dominated Set, and call his semen forth, and it answered from inside Set.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.theologywebsite.com/etext/egypt/horus.shtml|title=Theology WebSite: Etext Index: Egyptian Myth: The 80 Years of Contention Between Horus and Seth|author=Scott David Foutz|website=theologywebsite.com|access-date=18 January 2015|archive-date=11 May 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170511103316/http://www.theologywebsite.com/etext/egypt/horus.shtml|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>Fleming, Fergus, and Alan Lothian. ''The Way to Eternity: Egyptian Myth''. Duncan Baird Publishers, 1997. pp. 80–81</ref> | |||

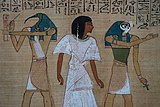

| ] in a painting from the tomb of ], thirteenth century BC{{sfn|Wilkinson|1992|pp=42–43}}]] | |||

| However, Set still refused to relent, and the other gods were getting tired from over eighty years of fighting and challenges. Horus and Set challenged each other to a boat race, where they each raced in a boat made of stone. Horus and Set agreed, and the race started. But Horus had an edge: his boat was made of wood painted to resemble stone, rather than true stone. Set's boat, being made of heavy stone, sank, but Horus' did not. Horus then won the race, and Set stepped down and officially gave Horus the throne of Egypt.<ref name="ReferenceA">Mythology, published by DBP, Chapter: Egypt's divine kingship.</ref> Upon becoming king after Set's defeat, Horus gives offerings to his deceased father Osiris, thus reviving and sustaining him in the afterlife. After the New Kingdom, Set was still considered the lord of the desert and its oases.<ref>{{cite book|last=te Velde |first=Herman |year=1967 |title=Seth, God of Confusion: A Study of His Role in Egyptian Mythology and Religion |edition=2nd |series=Probleme der Ägyptologie 6 |location=Leiden |publisher=] |isbn=978-90-04-05402-8 |translator-first=G. E.|translator-last=van Baaren-Pape }}</ref> | |||

| In many versions of the story, Horus and Set divide the realm between them. This division can be equated with any of several fundamental dualities that the Egyptians saw in their world. Horus may receive the fertile lands around the Nile, the core of Egyptian civilization, in which case Set takes the barren desert or the foreign lands that are associated with it; Horus may rule the earth while Set dwells in the sky; and each god may take one of the two traditional halves of the country, Upper and Lower Egypt, in which case either god may be connected with either region. Yet in the ], ], as judge, first apportions the realm between the claimants and then reverses himself, awarding sole control to Horus. In this peaceable union, Horus and Set are reconciled, and the dualities that they represent have been resolved into a united whole. Through this resolution, the order is restored after the tumultuous conflict.{{sfn|te Velde|1967|pages=59–63}}] and ]]]Egyptologists have often tried to connect the conflict between the two gods with political events early in Egypt's history or prehistory. The cases in which the combatants divide the kingdom, and the frequent association of the paired Horus and Set with the union of Upper and Lower Egypt, suggest that the two deities represent some kind of division within the country. Egyptian tradition and archaeological evidence indicate that Egypt was united at the beginning of its history when an Upper Egyptian kingdom, in the south, conquered Lower Egypt in the north. The Upper Egyptian rulers called themselves "followers of Horus", and Horus became the tutelary deity of the unified polity and its kings. Yet Horus and Set cannot be easily equated with the two halves of the country. Both deities had several cult centers in each region, and Horus is often associated with Lower Egypt and Set with Upper Egypt. Other events may have also affected the myth. Before even Upper Egypt had a single ruler, two of its major cities were ], in the far south, and ], many miles to the north. The rulers of Nekhen, where Horus was the patron deity, are generally believed to have unified Upper Egypt, including Nagada, under their sway. Set was associated with Nagada, so it is possible that the divine conflict dimly reflects an enmity between the cities in the distant past. Much later, at the end of the ] ({{Circa|2890–2686 BCE}}), Pharaoh ] used the ] to write his ] name in place of the falcon hieroglyph representing Horus. His successor ] used both Horus and Set in the writing of his serekh. This evidence has prompted conjecture that the Second Dynasty saw a clash between the followers of the Horus king and the worshippers of Set led by Seth-Peribsen. Khasekhemwy's use of the two animal symbols would then represent the reconciliation of the two factions, as does the resolution of the myth.<ref>Meltzer in Redford, pp. 165–166</ref> | |||

| === |

=== Golden Horus Osiris === | ||

| Horus gradually took on the nature as both the son of Osiris and Osiris himself. He was referred to as Golden Horus Osiris.<ref>Yoyotte, Jean, Une notice biographique du roi Osiris, BIFAO 77 (1977), p.145</ref><ref>Hymn to Osiris Un-Nefer, Translated by E.A.Wallis Budge</ref><ref>Budge, E.A. Wallis; 1901, Egyptian Magic, Kegan, Paul, Trench and Trübner & Co., London</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.egyptiangods.co.uk/horus.htm|title=Horus - Egyptian God Horus - Egyptian Mythology - Horus - Eye of Horus|first=Kevin|last=Roxburgh|website=www.egyptiangods.co.uk|access-date=2018-06-02|archive-date=2016-03-01|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160301140900/http://egyptiangods.co.uk/horus.htm|url-status=live}}</ref> In the ] he is given the full royal titulary of both that of Horus and Osiris. He was sometimes believed to be both the father of himself as well as his own son, and some later accounts have Osiris being brought back to life by Isis.<ref>E.A. Wallis Budge, Osiris and the Egyptian resurrection, Volume 2 (London: P. L. Warner; New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1911), 31.</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| When Ra assimilated ] into ''Atum-Ra'', Horus became considered part of what had been the ]. Since in this version Atum had no wife and produced his children by ] de facto, Hathor was easily inserted as the mother of the previously "motherless" subsequent generation of children. However, Horus did not fit in so easily, since if he was identified as the son of Hathor and Atum-Ra in the Ennead, he would then be the brother of the primordial air and moisture, and the uncle of the sky and earth, between which there was initially nothing, which was not very consistent with his being the sun. Instead, he was made the brother of ], ], Set, and ], as this was the only plausible level at which he could meaningfully rule over the sun and the pharaoh's kingdom. It was in this form that he was worshipped at ] as '''Har-]''' (also abbreviated '''Bebti'''). | |||

| == Forms of Horus == | |||

| Since Horus had become more and more identified with the sun since his identification as Ra, his identification as also being the moon suffered, so it was possible for the rise of other moon deities, without complicating the system of belief too much. Consequently, ] became a new moon god. ], who also had been a moon god, became much more associated with secondary mythological aspects of the moon, such as ], ], and ]. When the ] of Thoth arose in power, Thoth was inserted into new versions of the earlier myths, making Thoth the one whose ] caused the semen of Set and Horus to respond--in the ] of the ''contestings of Set and Horus'', for example. | |||

| <gallery widths="160" heights="160" perrow="5"> | |||

| File:Horus (based on reliefs).svg|Horus represented as a falcon-headed man | |||

| File:Re-Horakhty.svg|Ra-Horakhty, A form of ] Syncretized with Horus | |||

| file:horus-set.svg|Horus and ] depicted as one | |||

| File:Hours the child.svg|], a form of Horus represented as a child | |||

| File:Horus as falcon.svg|Horus as a falcon | |||

| File:Horus as falcon (crowned).svg|Horus represented as a crowned falcon | |||

| File:Haroeris.svg|Har-em-akhet or Heru-ur, two forms of Horus in which he had the body of a lion | |||

| File:Hor-imy-shenut.svg|Hor-imy-shenut, a form of Horus in which he had the body of a crocodile | |||

| File:Ancient Egypt Wings.svg|Heru-Behdeti, a form of Horus represented as a winged sun | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| Thoth's priests went on to explain how it could be possible that in older myths there were five children of ] and ]. They said that Thoth had ] the birth of a great king of the gods and so Ra, afraid of being usurped, had cursed Nut with not being able to give birth on any day in the year. In order to remove this ], Thoth proceeded to gamble with Chons, winning 1/72nd of ] from him. Prior to this time in Egyptian history, the calendar had 360 days. The Egyptian calendar was reformed around this time and gained five extra days, so a new version of the myth was used to explain the five children of Nut. 1/72 portion of moonlight for each day corresponded to five extra days, and so the new tale states that Nut was able to give birth to her five children again, one on each of these extra days. | |||

| == Mystery religion == | |||

| Since recognition of Horus as the son of Osiris was only in existence after Osiris's death, and because Horus, in an earlier guise, was the husband of ], in later traditions, it came to be said that Horus was the resurrected form of Osiris.{{Fact|date=September 2007}} Likewise, as the form of Horus before his death and resurrection, Osiris, who had already become considered a form of creator when belief about Osiris assimilated that about Ptah-Seker, also became considered to be the only creator, since Horus had gained these aspects of Ra. | |||

| === Heru-ur (Horus the Elder) === | |||

| Eventually, in the Hellenic period, Horus was, in some locations, identified completely as Osiris, and became his own Father, since this concept was not so disturbing to Greek philosophy as it had been to that of ancient Egypt. In this form, Horus was sometimes known as '''Heru-sema-tawy''' ({{unicode|ḥr.w smȝ tȝ.wy}} 'Horus, Uniter of Two Lands'). | |||

| {{Infobox deity | |||

| | type = Egyptian | |||

| | name = Heru-ur | |||

| | image = Haroeris.svg | |||

| | cult_center = ], ] | |||

| | symbol = falcon, falcon-headed man, ] | |||

| | parents = ] and ], or ] and ] (in ]) | |||

| | siblings = ], ], ], and ], or Tasenetnofret (in ]) | |||

| | consort = ], ], Tasenetnofret (in ]) | |||

| | offspring = ], ], ], ], or Panebtawy (in ]) | |||

| | image_upright = 1 | |||

| }}<!-- This section is linked from the redirect Horus the Elder --> | |||

| '''Heru-]''', also known as '''Heru-wer''', '''Haroeris''', '''Horus the Great''', and '''Horus the Elder''', was the mature representation of the god Horus.<ref>Wilkinson, Richard H. (2003). The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. p. 200</ref> This manifestation of Horus was especially worshipped at Letopolis in Lower Egypt. The Greeks identified him with the Greek god ].<ref name=":1" /> | |||

| His titles include: 'foremost of the two eyes', 'great god', 'lord of Ombos', 'possessor of the ijt-knife, who resides in Letopolis', 'Shu, son of Ra', 'Horus, strong of arm', 'great of power' and 'lord of the slaughter in the entire land'.<ref> Minas-Nerpel, Martina (2017). ''Offering the ij.t-knife to in the Temple of Isis at Shanhur''. In: Illuminating Osiris. Egyptological Studies in Honor of Mark Smith (Material and Visual Culture of Ancient Egypt 2). Lockwood Press, Atlanta, 2017, p.264 </ref> 'Foremost of the two eyes' was a common epithet which was referring to the two eyes of the sky god. The two eyes represent the sun and the moon, as well as the Wadjet-eye, and played an important role in the cult of Heru-ur. His cult center was originally Letopolis; later he was also worshipped in Kom Ombo and Qus.<ref> Minas-Nerpel (2017), p.266</ref> In Kom Ombo, he was worshipped as the son of Ra and ]<ref> Minas-Nerpel (2017), p.275</ref> ,the husband of his sister-wife Tasenetnofret and father of the child god Panebtawy.<ref>Abdelhalim, Ali. (2019). ''Notes on the Bandeau-Texts of Columns of Kom Ombo Temple''. Bulletin of the Center Papyrological Studies, p.298</ref> | |||

| ] necklace said to depict Hariesis (Horus) extending a ] in front of the goddess ]]] | |||

| By assimilating Hathor—who had herself assimilated ], who was associated with music and in particular, the ]—Isis was likewise, thought of in some areas in the same manner. This particularly happened amongst the groups who thought of Horus as his own father, and so Horus, in the form of the son, amongst these groups often became known as Ihy (alternately: Ihi, Ehi, Ahi, Ihu), meaning "sistrum player", which allowed the confusion between the father and son to be side-stepped. A supplicant depicted on an Egyptian ] necklace is said to depict Hariesis (Horus) extending a ] in front of the goddess ], an earlier sun deity who also was seen as an aspect of Hathor. | |||

| In his Moralia, the Greek philosopher Plutarch mentions three additional parentage traditions that supposedly existed for Heru-ur during the Ptolemaic period. According to Plutarch's account, Heru-ur was believed to be the son of Geb and Nut, born on the second of the five intercalary days at the end of the year, after Osiris and before Set, Isis, and Nephthys. Plutarch also records a variant tradition that assigns different fathers to Nut's children: Osiris and Heru-ur are attributed to Nut and Ra, Isis to Nut and Thoth, while Nephthys and Set are said to be the children of Nut and Geb. Additionally, similar to other manifestations of Horus, Heru-ur is sometimes regarded as the child of Isis and Osiris, conceived by the pair while still within the womb of Nut.<ref> Griffiths, J. Gwyn, ed. (1970). ''Plutarch's De Iside et Osiride''. University of Wales Press, pp.135-137</ref> | |||

| The combination of this, now rather esoteric new mythology, with the philosophy of Plato, which was becoming popular on the Mediterranean shores, lead to the tale becoming the basis of a mystery religion. Many Greeks, and those of other nations, who encountered the faith, thought it so profound that they sought to create their own, modelled upon it, but using their own deities. This led to the creation of what was effectively one religion, which was, in many places, adjusted to reflect, albeit superficially, the local mythology although it substantially adjusted them. The new religion is known to modern scholars as that of ]. | |||

| Heru-ur was sometimes depicted fully as a falcon; he was sometimes given the title '''Kemwer''', meaning "(the) great black (one)".{{Citation needed|date=September 2024}}. Heru-ur was also depicted as a ] (a falcon headed lion).<ref>http://tarot.vn/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/CCI18122015_0105.png {{Bare URL image|date=March 2022}}</ref> | |||

| ] described as associating ]'s relationship with his wife, Great Royal Wife ] by depicting a legend of the birth of Ra, in which (reading from left to right) the ibis-headed ] announced to ], the primordial waters, that she would become pregnant with Ra (the new king of heaven). In the next image, the impregnation of Neith was achieved by ] (on her left) and ] (on her right) applying the ], thereby leaving Neith "ever virgin". To the right are images of the subsequent birth over a birth brick, as well as the praise raised to the child by Neith's courtiers and fellow deities. The form of Ra at this point was Ra-Amun, who was becoming identified as ]. The child of Tiye, who consequently is described as being ''Ra/Horus'' through this association with the legend, went on to become ], when pharaoh.]] | |||

| <br clear="all" /> | |||

| Other variants include ''Hor Merti'' 'Horus of the two eyes' and ''Horkhenti Irti''.<ref name=":0">Patricia Turner, Charles Russell Coulter, ''Dictionary of ancient deities'', 2001.</ref> | |||

| === Heru-pa-khered (Horus the child) === | |||

| Heru-pa-khered (] to the Ptolemaic Greeks), also known as '''Horus the child''', is represented in the form of a youth wearing a lock of hair (a sign of youth) on the right of his head while sucking his finger. In addition, he usually wears the united crowns of Egypt, the crown of Upper Egypt and the crown of Lower Egypt. He is a form of the rising sun, representing its earliest light.<ref name=":1">{{Cite book|last=Strudwick|first=Helen|title=The Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt|publisher=Sterling Publishing Co., Inc.|year=2006|isbn=978-1-4351-4654-9|location=New York|pages=158–159}}</ref> | |||

| As early as the third millennium BCE, Ancient Egyptian ext like the Pyramid Texts referenced the birth, youth, and adulthood of the god Horus. However, his image as a child deity was not firmly established until the first millennium BCE, when Egyptian theologians began associating child gods with adult gods. From a historical perspective, Harpocrates is an artificial creation, originating from the priesthood of Thebes and later gaining popularity in the cults of other cities. His first known depiction dates to a stele from Mendes, erected during the reign of Sheshonq III (22nd Libyan Dynasty), commemorating a donation by the flutist Ânkhhorpakhered. Initially, Harpocrates originated as a duplicate of Khonsu-pa-khered, providing a child-god figure for the funerary gods Osiris and Isis. Unlike Horus, who was traditionally depicted as an adult, Khonsu, the lunar god, was inherently associated with youth. The cults of Harpocrates and Khonsu originally merged in a sanctuary within the Mut enclosure at Karnak. This sanctuary, later transformed into a mammisi (birth house) under the 21st Dynasty, celebrated the divine birth of the pharaoh, connecting the queen mother with the mother-goddesses Mut and Isis. The merging of local Theban beliefs with the Osiris cult endowed Harpocrates with dual ancestry, as seen in inscriptions at Wadi Hammamat which name him 'Horus-the-child, son of Osiris and Isis, the Elder, the first-born of Amun.' The Osirian tradition solidified Harpocrates as the archetype of child-gods, firmly integrated into the Osirian family.<ref>Forgeau, Annie (2010).Horus-fils-d'Isis. La jeunesse d'un dieu. IFAO. p.529 ISBN 978-2-7247-0517-1</ref> | |||

| === Heru-Behdeti (Horus of ]) === | |||

| The ] of Horus of ] is a symbol in associated with ], ], and power in ancient Egypt.<ref name=":02">{{Cite web |last=Rhys |first=Dani |date=2020-11-22 |title=What Was the Winged Sun in Egyptian Mythology? |url=https://symbolsage.com/winged-sun-egyptian-mythology/ |access-date=2023-03-13 |website=Symbol Sage |language=en-US}}</ref> The winged sun is symbolic also of the eternal soul. When placed above the temple doors it served as a reminder to the people of their eternal nature.<ref>{{Cite web |last=((Spydaman13)) |date= November 12, 2011 |title=Illuminati Sun Symbolism -- Auto Logos, Winged Solar-Disk (Part 3/3) |url=https://12160.info/profiles/blogs/illuminati-sun-symbolism-auto-logos-winged-solar-disk-part-3-3 |access-date=2023-03-13 |website=12160.info |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Adventist Logo Change |url=https://straighttestimony.com/seventh-day-adventist-logo/ |access-date=2023-03-13 |website=The Straight Testimony |language=en-US |url-status=live |archive-url=https://archive.today/20240321013326/https://straighttestimony.com/seventh-day-adventist-logo/ |archive-date= 21 Mar 2024 }}</ref> The winged sun was depicted on the top of pylons in the ancient temples throughout Egypt. | |||

| === Her-em-akhet (Horus in the Horizon) === | |||

| Her-em-akhet (or Horemakhet), (''Harmakhis'' in Greek), represented the dawn and the early morning sun. He was often depicted as a sphinx with the head of a man (like the ]), or as a ], a creature with a lion's body and a falcon's head and wings, sometimes with the head of a ] or ] (the latter providing a link to the god ], the rising sun). It was believed that he was the inspiration for the ], constructed under the order of ], whose head it depicts. | |||

| Other forms of Horus include: | |||

| *''Hor Merti'' ('Horus of the Two Eyes'); | |||

| *''Horkhenti Irti'';<ref name=":0" /> | |||

| *''Her-sema-tawy'' ('Horus Uniter of the Two Lands'), the Greek ''Harsomptus'', depicted like the double-crowned Horus | |||

| *''Her-iunmutef'' or ''Iunmutef'', depicted as a priest with a leopard-skin over the torso; | |||

| *''Herui'' (the "double falcon or Horuses"), the 5th ] god of ] in ]<gallery> | |||

| File:Harpocrates gulb 082006.JPG|''Heru-pa-khered'' ("Horus the child", known as Harpocrates to the Greeks) in the form of a child wearing the pschent and a ] | |||

| File:Medinet Habu Ramses III. Tempelrelief 15.JPG|''Heru-Behdeti'' ("Horus of Behedet") as a winged sun disk on the ceiling to the entrance to the temple of Ramses III | |||

| File:Edfu17 c.jpg|''Her-em-akhet'' (Greek: Harmakhis), the wall relief of a hieracosphinx depicted at the Temple of Horus in Edfu | |||

| File:Seth + Horus = 2 terres.jpg|''Her-sema-tawy'' ('Horus, Uniter of the Two Lands'), tying the papyrus and reed plants in the '']'' symbol for the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt opposite with ] (Sutekh) | |||

| File:Iunmutef (Her-Iunmutef).jpg|''Her-iunmutef'' (''Iunmutef''), ('Horus, Pillar of His Mother'), depicted as a priest wearing a leopard-skin over torso in the ], Valley of the Queens | |||

| File:Egypt sahura and god of nomo.jpg|], the 5th ] god of ] in ] besides the pharaoh ] | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| == Celebrations of Horus == | |||

| The Festival of Victory (Egyptian: Heb Nekhtet) was an annual Egyptian festival dedicated to the god Horus. The Festival of Victory was celebrated at the Temple of Horus at Edfu, and took place during the second month of the ] (or the sixth month of the ]). | |||

| The ceremonies which took place during the Festival of Victory included the performance of a sacred drama which commemorated the victory of Horus over Set. The main actor in this drama was the king of Egypt himself, who played the role of Horus. His adversary was a hippopotamus, who played the role of Set. In the course of the ritual, the king would strike the hippopotamus with a harpoon. The destruction of the hippopotamus by the king commemorated the defeat of Set by Horus, which also legitimised the king. | |||

| It is unlikely that the king attended the Festival of Victory every year; in many cases he was probably represented by a priest. It is also unlikely that a real hippopotamus was used in the festival every year; in many cases it was probably represented by a model.<ref>H. W. Fairman. The Triumph of Horus: An Ancient Egyptian Sacred Drama. London, 1974</ref> | |||

| The 4th-century Roman author ] mentions another annual Egyptian festival dedicated to Horus in his '']''. Macrobius specifies this festival as occurring on the ]. The 4th-century Christian bishop ] also mentions a winter solstice festival of Horus in his '']''.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.loebclassics.com/view/macrobius-saturnalia/2011/pb_LCL510.1.xml|title=MACROBIUS, Saturnalia – Loeb Classical Library|website=Loeb Classical Library|access-date=2015-07-09|archive-date=2015-07-09|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150709082219/https://www.loebclassics.com/view/macrobius-saturnalia/2011/pb_LCL510.1.xml|url-status=live}}</ref> However, this festival is not attested in any native Egyptian sources. | |||

| ==Suggested influence on Christianity == | |||

| William R. Cooper's 1877 book and ]'s self-published 2008 book, among others, have suggested that there are many similarities between the story of Horus and the much later story of ].<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Iaqe9CG_s6cC&q=jesus+horus&pg=PR6|title=Christ in Egypt: The Horus-Jesus Connection|last1=Murdock|first1=D. M.|last2=S|first2=Acharya|date=December 2008|publisher=Stellar House Publishing|isbn=978-0-9799631-1-7|language=en|access-date=2020-11-12|archive-date=2023-04-03|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230403005316/https://books.google.com/books?id=Iaqe9CG_s6cC&q=jesus+horus&pg=PR6|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|url=https://archive.org/details/horusmythinitsr00coopgoog|page=|quote=jesus horus.|title=The Horus Myth in Its Relation to Christianity|last=Cooper|first=William Ricketts|date=1877|publisher=Hardwicke & Bogue|language=en}}</ref> This outlook remains very controversial and is disputed.<ref name=Ehrman>{{cite book|last=Ehrman|first=Bart D.|title=Did Jesus Exist?: The Historical Argument for Jesus of Nazareth|date=2012|publisher=HarperOne|isbn=978-0062206442}}</ref><ref>C Henderson, S Hayes, Debunking the Horus-Jesus Connection, 2015, Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1996</ref><ref>Houdmann, S. Michael, Questions about Jesus Christ, WestBow Press, 2013</ref> | |||

| == In popular culture == | |||

| Declan Hannigan portrays Horus in the ] (MCU) television series '']'' (2022).<ref name="EnneadCast">{{Cite web |last=Silverio |first=Ben F. |date=April 13, 2022 |title=A Guide To The Council Of Gods On Moon Knight: Who's Who? |url=https://www.slashfilm.com/831472/a-guide-to-the-council-of-gods-on-moon-knight-whos-who/ |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220413200256/https://www.slashfilm.com/831472/a-guide-to-the-council-of-gods-on-moon-knight-whos-who/ |archive-date=April 13, 2022 |access-date=April 19, 2022 |website=]}}</ref> | |||

| In the film series ], a group of underworld warrior deities appear in '']'' when Kahmunrah uses the combination to open the gate to the ] and summon an army of Horus warriors. The warriors appear from the underworld carrying spears ready to attack and join Kahmunrah's fight to take over the world. | |||

| Horus is a Warrior class God in the ] game '']'' with the title of "The Rightful Heir".<ref>{{Citation |title=Smite - Horus and Set Reveal Trailer - IGN |date=17 April 2019 |url=https://www.ign.com/videos/smite-horus-and-set-reveal-trailer |language=en |access-date=2023-02-09 |archive-date=2023-02-09 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230209154436/https://www.ign.com/videos/smite-horus-and-set-reveal-trailer |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| In the book trilogy '']'' by ], main character Carter Kane hosts the spirit of Horus when he is released in the ] along with four other Egyptian deities. Horus speaks to Carter throughout the trilogy, offering him his advice and wisdom. | |||

| In the ] ] '']'' Horus is portrayed by ]. In the film, he helps out a mortal named Bek to stop his uncle Set while also trying to reclaim his throne and bring peace to Egypt. | |||

| Horus appears in a 1980 science fiction graphic novel '']'' written and illustrated by French cartoonist and storyteller ]. | |||

| == Gallery == | |||

| <gallery widths="160" heights="160" perrow="5"> | |||

| File:Golden head of Horus 01.jpg|Horus, patron deity of Hierakonpolis (near ]), the predynastic capital of Upper Egypt. Its head was executed by means of beating the gold then connecting it with the copper body. A uraeus is fixed to the diadem which supports two tall openwork feathers. The eyes are inlaid with obsidian. ]. | |||

| File:La Tombe de Horemheb cropped.jpg|Horus (right) in the Tomb of Horemheb (]) in the Valley of the Kings | |||

| File:Temple of Edfu 05.jpg|Horus relief in the ] | |||

| File:British Museum - Room 62 (21390272978).jpg|In Duat Horus conducts ] to a shrine in which Osiris sits enthroned | |||

| File:Abydos Tempelrelief Sethos I. 24.JPG|Relief in the ] of pharaoh ] presenting an offering to Horus | |||

| File:Head of Horus for attachment MET LC-52 95 2 EGDP023644.jpg|Head of Horus statue, 664–30 BCE, Late Period–Ptolemaic Period | |||

| File:Copper alloy statues.jpg|Copper-alloy of Horus (centre) as a Roman officer with '']'' stances (]) | |||

| File:Horus - Temple of Seti I (3500450346).jpg|Relief of Horus in the temple of ] in ] | |||

| File:God Horus as a falcon wearing the Double Crown of Egypt. 27th dynasty. State Museum of Egyptian Art, Munich.jpg|God Horus as a falcon wearing the Double Crown of Egypt. 27th dynasty. State Museum of Egyptian Art, Munich | |||

| File:Horus R01.jpg|Statue of Horus from the reign of ] (], {{circa|1400 BCE}}) in the ], Belgium | |||

| File:Head of a Falcon (Horus) from Memphis, Egypt produced after 1196 BCE Penn Museum.jpg|Head of Horus from Memphis, 1196 BCE, Penn Museum | |||

| File:S F-E-CAMERON Hatshepsut Hawk - 83d40m - Wadjet -2pstcrpt.JPG|Horus represented in relief with ] and wearing the double crown. ] | |||

| File:Temple of Edfu, Statue of Horus 2, Egypt.jpg|Statue of Horus in the ] | |||

| File:Falcon Horus, deity of Hierakonpolis, on a Naqada IIC jar, British Museum EA 36328.jpg|Falcon Horus, deity of Hierakonpolis, on a ]C jar, {{circa|3500 BCE}}, British Museum EA36328.<ref>{{cite web|title=British Museum notice|date=23 January 2020|url=https://www.flickr.com/photos/anthonyhuan/49431567466/in/photostream/|access-date=16 October 2020|archive-date=3 April 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230403005313/https://www.flickr.com/photos/anthonyhuan/49431567466/in/photostream/|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Jar, British Museum |url=https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/Y_EA36328 |website=The British Museum |language=en |access-date=2020-10-16 |archive-date=2020-10-17 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201017051306/https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/Y_EA36328 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| == See also == | == See also == | ||

| * ] | |||

| {{commonscat|Horus}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| {{commonscat|Ra-Horakhty}} | |||

| * ], Egyptian deity | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| ==Notes== | |||

| {{notelist}} | |||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| {{Reflist}} | |||

| <references/> | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| {{Ancient Egypt}} | |||

| {{Commons category|Horus}} | |||

| * | |||

| {{Ancient Egyptian religion footer|collapsed}}{{Kushite religion footer}}{{Portal bar|Ancient Egypt|Egypt|Myths|Religion}} | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 19:01, 11 January 2025

Egyptian war and sky deity This article is about the ancient Egyptian deity. For the Roman poet, see Horace. For other uses, see Horus (disambiguation).| Horus | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Horus was often the ancient Egyptians' national tutelary deity. He was usually depicted as a falcon-headed man wearing the pschent, or a red and white crown, as a symbol of kingship over the entire kingdom of Egypt. Horus was often the ancient Egyptians' national tutelary deity. He was usually depicted as a falcon-headed man wearing the pschent, or a red and white crown, as a symbol of kingship over the entire kingdom of Egypt. | |||

| Name in hieroglyphs |

| ||

| Major cult center | Nekhen, Edfu | ||

| Symbol | Eye of Horus | ||

| Genealogy | |||

| Parents | Osiris and Isis, Osiris and Nephthys, Hathor | ||

| Siblings | Anubis, Bastet | ||

| Consort | Hathor, Isis, Serket Nephthys Ta-Bitjet | ||

| Offspring | Ihy, Four Sons of Horus (Horus the Elder) | ||

| Equivalents | |||

| Greek | Apollo | ||

| Nubian | Mandulis | ||

Horus (/hɔːrəs/), also known as Heru, Har, Her, or Hor (/hɔːr/) in Ancient Egyptian, is one of the most significant ancient Egyptian deities who served many functions, most notably as the god of kingship, healing, protection, the sun, and the sky. He was worshipped from at least the late prehistoric Egypt until the Ptolemaic Kingdom and Roman Egypt. Different forms of Horus are recorded in history, and these are treated as distinct gods by Egyptologists. These various forms may be different manifestations of the same multi-layered deity in which certain attributes or syncretic relationships are emphasized, not necessarily in opposition but complementary to one another, consistent with how the Ancient Egyptians viewed the multiple facets of reality. He was most often depicted as a falcon, most likely a lanner falcon or peregrine falcon, or as a man with a falcon head.

The earliest recorded form of Horus is the tutelary deity of Nekhen in Upper Egypt, who is the first known national god, specifically related to the ruling pharaoh who in time came to be regarded as a manifestation of Horus in life and Osiris in death. The most commonly encountered family relationship describes Horus as the son of Isis and Osiris, and he plays a key role in the Osiris myth as Osiris's heir and the rival to Set, the murderer and brother of Osiris. In another tradition, Hathor is regarded as his mother and sometimes as his wife.

Claudius Aelianus wrote that Egyptians called the god Apollo "Horus" in their own language. However, Plutarch, elaborating further on the same tradition reported by the Greeks, specified that the one "Horus" whom the Egyptians equated with the Greek Apollo was in fact "Horus the Elder", a primordial form of Horus whom Plutarch distinguishes from both Horus and Harpocrates.

Etymology

Horus is recorded in Egyptian hieroglyphs as ḥr.w "Falcon", 𓅃; the original pronunciation has been reconstructed as /ˈħaːɾuw/ in Old Egyptian and early Middle Egyptian, /ˈħaːɾəʔ/ in later Middle Egyptian, and /ˈħoːɾ(ə)/ in Late Egyptian. Additional meanings are thought to have been "the distant one" or "one who is above, over". As the language changed over time, it appeared in Coptic varieties variously as /hɔr/ or /ħoːɾ/ (Ϩⲱⲣ) and was adopted into ancient Greek as Ὧρος Hō̂ros (pronounced at the time as /hɔ̂ːros/). It also survives in Late Egyptian and Coptic theophoric name forms such as Siese "son of Isis" and Harsiese "Horus, Son of Isis".

Horus and the pharaoh

The pharaoh was associated with many specific deities. He was identified directly with Horus, who represented kingship itself and was seen as a protector of the pharaoh, and he was seen as the son of Ra, who ruled and regulated nature as the pharaoh ruled and regulated society.

The Pyramid Texts (c. 2400–2300 BCE) describe the nature of the pharaoh in different characters as both Horus and Osiris. The pharaoh as Horus in life became the pharaoh as Osiris in death, where he was united with the other gods. New incarnations of Horus succeeded the deceased pharaoh on earth in the form of new pharaohs.

The lineage of Horus, the eventual product of unions between the children of Atum, may have been a means to explain and justify pharaonic power. The gods produced by Atum were all representative of cosmic and terrestrial forces in Egyptian life. By identifying Horus as the offspring of these forces, then identifying him with Atum himself, and finally identifying the Pharaoh with Horus, the Pharaoh theologically had dominion over all the world.

Origin mythology

In one tale, Horus is born to the goddess Isis after she retrieved all the dismembered body parts of her murdered husband Osiris, except his penis, which was thrown into the Nile and eaten by a catfish/Medjed, or sometimes depicted as instead by a crab, and according to Plutarch's account used her magic powers to resurrect Osiris and fashion a phallus to conceive her son (older Egyptian accounts have the penis of Osiris surviving).

After becoming pregnant with Horus, Isis fled to the Nile Delta marshlands to hide from her brother Set, who jealously killed Osiris and who she knew would want to kill their son. There Isis bore a divine son, Horus. As birth, death and rebirth are recurrent themes in Egyptian lore and cosmology, it is not particularly strange that Horus also is the brother of Osiris and Isis, by Nut and Geb, together with Nephthys and Set. This elder Horus is called Hrw-wr - Hourou'Ur - as opposed to Hrw-P-Khrd - the child Horus, at some point adopted by the Greeks as Harpocrates.

Genealogy

| Ra God of the sun | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tefnut | Shu | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Geb | Nut | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Isis | Osiris | Nephthys | Set | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Horus | Hathor | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Mythological roles

| |||

| rˁ-ḥr-3ḫty "Ra-Horakhty" in hieroglyphs | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Sky god

Since Horus was said to be the sky, he was considered to also contain the Sun and Moon. Egyptians believed that the Sun was his right eye and the Moon his left and that they traversed the sky when he, a falcon, flew across it. Later, the reason that the Moon was not as bright as the sun was explained by a tale, known as The Contendings of Horus and Seth. In this tale, it was said that Seth, the patron of Upper Egypt, and Horus, the patron of Lower Egypt, had battled for Egypt brutally, with neither side victorious, until eventually, the gods sided with Horus.

As Horus was the ultimate victor he became known as ḥr.w or "Horus the Great", but more usually translated as "Horus the Elder". In the struggle, Set had lost a testicle, and Horus' eye was gouged out.

Horus was occasionally shown in art as a naked boy with a finger in his mouth sitting on a lotus with his mother. In the form of a youth, Horus was referred to as nfr ḥr.w "Good Horus", transliterated Neferhor, Nephoros or Nopheros (reconstructed as naːfiru ħaːruw).

The Eye of Horus is an ancient Egyptian symbol of protection and royal power from deities, in this case from Horus or Ra. The symbol is seen on images of Horus' mother, Isis, and on other deities associated with her. In the Egyptian language, the word for this symbol was "wedjat" (wɟt). It was the eye of one of the earliest Egyptian deities, Wadjet, who later became associated with Bastet, Mut, and Hathor as well. Wadjet was a solar deity and this symbol began as her all-seeing eye. In early artwork, Hathor is also depicted with this eye. Funerary amulets were often made in the shape of the Eye of Horus. The Wedjat or Eye of Horus is "the central element" of seven "gold, faience, carnelian and lapis lazuli" bracelets found on the mummy of Shoshenq II. The Wedjat "was intended to protect the king in the afterlife" and to ward off evil. Egyptian and Near Eastern sailors would frequently paint the symbol on the bow of their vessel to ensure safe sea travel.

Horus was also thought to protect the sky.

Conflict between Horus and Set

Horus was told by his mother, Isis, to protect the people of Egypt from Set, the god of the desert, who had killed Horus' father, Osiris. Horus had many battles with Set, not only to avenge his father but to choose the rightful ruler of Egypt. In these battles, Horus came to be associated with Lower Egypt and became its patron.

According to The Contendings of Horus and Seth, Set is depicted as trying to prove his dominance by seducing Horus and then having sexual intercourse with him. However, Horus places his hand between his thighs and catches Set's semen, then subsequently throws it in the river so that he may not be said to have been inseminated by Set. Horus (or Isis herself in some versions) then deliberately spreads his semen on some lettuce, which was Set's favourite food. After Set had eaten the lettuce, they went to the gods to try to settle the argument over the rule of Egypt. The gods first listened to Set's claim of dominance over Horus, and call his semen forth, but it answered from the river, invalidating his claim. Then, the gods listened to Horus' claim of having dominated Set, and call his semen forth, and it answered from inside Set.

However, Set still refused to relent, and the other gods were getting tired from over eighty years of fighting and challenges. Horus and Set challenged each other to a boat race, where they each raced in a boat made of stone. Horus and Set agreed, and the race started. But Horus had an edge: his boat was made of wood painted to resemble stone, rather than true stone. Set's boat, being made of heavy stone, sank, but Horus' did not. Horus then won the race, and Set stepped down and officially gave Horus the throne of Egypt. Upon becoming king after Set's defeat, Horus gives offerings to his deceased father Osiris, thus reviving and sustaining him in the afterlife. After the New Kingdom, Set was still considered the lord of the desert and its oases.

In many versions of the story, Horus and Set divide the realm between them. This division can be equated with any of several fundamental dualities that the Egyptians saw in their world. Horus may receive the fertile lands around the Nile, the core of Egyptian civilization, in which case Set takes the barren desert or the foreign lands that are associated with it; Horus may rule the earth while Set dwells in the sky; and each god may take one of the two traditional halves of the country, Upper and Lower Egypt, in which case either god may be connected with either region. Yet in the Memphite Theology, Geb, as judge, first apportions the realm between the claimants and then reverses himself, awarding sole control to Horus. In this peaceable union, Horus and Set are reconciled, and the dualities that they represent have been resolved into a united whole. Through this resolution, the order is restored after the tumultuous conflict.

Egyptologists have often tried to connect the conflict between the two gods with political events early in Egypt's history or prehistory. The cases in which the combatants divide the kingdom, and the frequent association of the paired Horus and Set with the union of Upper and Lower Egypt, suggest that the two deities represent some kind of division within the country. Egyptian tradition and archaeological evidence indicate that Egypt was united at the beginning of its history when an Upper Egyptian kingdom, in the south, conquered Lower Egypt in the north. The Upper Egyptian rulers called themselves "followers of Horus", and Horus became the tutelary deity of the unified polity and its kings. Yet Horus and Set cannot be easily equated with the two halves of the country. Both deities had several cult centers in each region, and Horus is often associated with Lower Egypt and Set with Upper Egypt. Other events may have also affected the myth. Before even Upper Egypt had a single ruler, two of its major cities were Nekhen, in the far south, and Nagada, many miles to the north. The rulers of Nekhen, where Horus was the patron deity, are generally believed to have unified Upper Egypt, including Nagada, under their sway. Set was associated with Nagada, so it is possible that the divine conflict dimly reflects an enmity between the cities in the distant past. Much later, at the end of the Second Dynasty (c. 2890–2686 BCE), Pharaoh Seth-Peribsen used the Set animal to write his serekh name in place of the falcon hieroglyph representing Horus. His successor Khasekhemwy used both Horus and Set in the writing of his serekh. This evidence has prompted conjecture that the Second Dynasty saw a clash between the followers of the Horus king and the worshippers of Set led by Seth-Peribsen. Khasekhemwy's use of the two animal symbols would then represent the reconciliation of the two factions, as does the resolution of the myth.

Golden Horus Osiris

Horus gradually took on the nature as both the son of Osiris and Osiris himself. He was referred to as Golden Horus Osiris. In the temple of Denderah he is given the full royal titulary of both that of Horus and Osiris. He was sometimes believed to be both the father of himself as well as his own son, and some later accounts have Osiris being brought back to life by Isis.

Forms of Horus

-

Horus represented as a falcon-headed man

Horus represented as a falcon-headed man

-

Ra-Horakhty, A form of Ra Syncretized with Horus

Ra-Horakhty, A form of Ra Syncretized with Horus

-

Horus and Set depicted as one

Horus and Set depicted as one

-

Heru-pa-khered, a form of Horus represented as a child

Heru-pa-khered, a form of Horus represented as a child

-

Horus as a falcon

Horus as a falcon

-

Horus represented as a crowned falcon

Horus represented as a crowned falcon

-

Har-em-akhet or Heru-ur, two forms of Horus in which he had the body of a lion

Har-em-akhet or Heru-ur, two forms of Horus in which he had the body of a lion

-

Hor-imy-shenut, a form of Horus in which he had the body of a crocodile

Hor-imy-shenut, a form of Horus in which he had the body of a crocodile

-

Heru-Behdeti, a form of Horus represented as a winged sun

Heru-Behdeti, a form of Horus represented as a winged sun

Heru-ur (Horus the Elder)

| Heru-ur | |

|---|---|

| |

| Major cult center | Heliopolis, Giza |

| Symbol | falcon, falcon-headed man, Hieracosphinx |

| Genealogy | |

| Parents | Geb and Nut, or Ra and Heqet (in Kom Ombo) |

| Siblings | Osiris, Isis, Set, and Nephthys, or Tasenetnofret (in Kom Ombo) |

| Consort | Serket, Hathor, Tasenetnofret (in Kom Ombo) |

| Offspring | Imset, Hapi, Duamutef, Qebehsenuef, or Panebtawy (in Kom Ombo) |

Heru-ur, also known as Heru-wer, Haroeris, Horus the Great, and Horus the Elder, was the mature representation of the god Horus. This manifestation of Horus was especially worshipped at Letopolis in Lower Egypt. The Greeks identified him with the Greek god Apollo.

His titles include: 'foremost of the two eyes', 'great god', 'lord of Ombos', 'possessor of the ijt-knife, who resides in Letopolis', 'Shu, son of Ra', 'Horus, strong of arm', 'great of power' and 'lord of the slaughter in the entire land'. 'Foremost of the two eyes' was a common epithet which was referring to the two eyes of the sky god. The two eyes represent the sun and the moon, as well as the Wadjet-eye, and played an important role in the cult of Heru-ur. His cult center was originally Letopolis; later he was also worshipped in Kom Ombo and Qus. In Kom Ombo, he was worshipped as the son of Ra and Heqet ,the husband of his sister-wife Tasenetnofret and father of the child god Panebtawy.

In his Moralia, the Greek philosopher Plutarch mentions three additional parentage traditions that supposedly existed for Heru-ur during the Ptolemaic period. According to Plutarch's account, Heru-ur was believed to be the son of Geb and Nut, born on the second of the five intercalary days at the end of the year, after Osiris and before Set, Isis, and Nephthys. Plutarch also records a variant tradition that assigns different fathers to Nut's children: Osiris and Heru-ur are attributed to Nut and Ra, Isis to Nut and Thoth, while Nephthys and Set are said to be the children of Nut and Geb. Additionally, similar to other manifestations of Horus, Heru-ur is sometimes regarded as the child of Isis and Osiris, conceived by the pair while still within the womb of Nut.

Heru-ur was sometimes depicted fully as a falcon; he was sometimes given the title Kemwer, meaning "(the) great black (one)".. Heru-ur was also depicted as a Hieracosphinx (a falcon headed lion).

Other variants include Hor Merti 'Horus of the two eyes' and Horkhenti Irti.

Heru-pa-khered (Horus the child)

Heru-pa-khered (Harpocrates to the Ptolemaic Greeks), also known as Horus the child, is represented in the form of a youth wearing a lock of hair (a sign of youth) on the right of his head while sucking his finger. In addition, he usually wears the united crowns of Egypt, the crown of Upper Egypt and the crown of Lower Egypt. He is a form of the rising sun, representing its earliest light.

As early as the third millennium BCE, Ancient Egyptian ext like the Pyramid Texts referenced the birth, youth, and adulthood of the god Horus. However, his image as a child deity was not firmly established until the first millennium BCE, when Egyptian theologians began associating child gods with adult gods. From a historical perspective, Harpocrates is an artificial creation, originating from the priesthood of Thebes and later gaining popularity in the cults of other cities. His first known depiction dates to a stele from Mendes, erected during the reign of Sheshonq III (22nd Libyan Dynasty), commemorating a donation by the flutist Ânkhhorpakhered. Initially, Harpocrates originated as a duplicate of Khonsu-pa-khered, providing a child-god figure for the funerary gods Osiris and Isis. Unlike Horus, who was traditionally depicted as an adult, Khonsu, the lunar god, was inherently associated with youth. The cults of Harpocrates and Khonsu originally merged in a sanctuary within the Mut enclosure at Karnak. This sanctuary, later transformed into a mammisi (birth house) under the 21st Dynasty, celebrated the divine birth of the pharaoh, connecting the queen mother with the mother-goddesses Mut and Isis. The merging of local Theban beliefs with the Osiris cult endowed Harpocrates with dual ancestry, as seen in inscriptions at Wadi Hammamat which name him 'Horus-the-child, son of Osiris and Isis, the Elder, the first-born of Amun.' The Osirian tradition solidified Harpocrates as the archetype of child-gods, firmly integrated into the Osirian family.

Heru-Behdeti (Horus of Behdet)

The winged sun of Horus of Edfu is a symbol in associated with divinity, royalty, and power in ancient Egypt. The winged sun is symbolic also of the eternal soul. When placed above the temple doors it served as a reminder to the people of their eternal nature. The winged sun was depicted on the top of pylons in the ancient temples throughout Egypt.

Her-em-akhet (Horus in the Horizon)

Her-em-akhet (or Horemakhet), (Harmakhis in Greek), represented the dawn and the early morning sun. He was often depicted as a sphinx with the head of a man (like the Great Sphinx of Giza), or as a hieracosphinx, a creature with a lion's body and a falcon's head and wings, sometimes with the head of a lion or ram (the latter providing a link to the god Khepri, the rising sun). It was believed that he was the inspiration for the Great Sphinx of Giza, constructed under the order of Khafre, whose head it depicts.

Other forms of Horus include:

- Hor Merti ('Horus of the Two Eyes');

- Horkhenti Irti;

- Her-sema-tawy ('Horus Uniter of the Two Lands'), the Greek Harsomptus, depicted like the double-crowned Horus

- Her-iunmutef or Iunmutef, depicted as a priest with a leopard-skin over the torso;

- Herui (the "double falcon or Horuses"), the 5th nome god of Upper Egypt in Coptos

-

Heru-pa-khered ("Horus the child", known as Harpocrates to the Greeks) in the form of a child wearing the pschent and a sidelock of youth

-

Heru-Behdeti ("Horus of Behedet") as a winged sun disk on the ceiling to the entrance to the temple of Ramses III

-

Her-em-akhet (Greek: Harmakhis), the wall relief of a hieracosphinx depicted at the Temple of Horus in Edfu

Her-em-akhet (Greek: Harmakhis), the wall relief of a hieracosphinx depicted at the Temple of Horus in Edfu

-

Her-sema-tawy ('Horus, Uniter of the Two Lands'), tying the papyrus and reed plants in the sema tawy symbol for the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt opposite with Set (Sutekh)

Her-sema-tawy ('Horus, Uniter of the Two Lands'), tying the papyrus and reed plants in the sema tawy symbol for the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt opposite with Set (Sutekh)

-

Her-iunmutef (Iunmutef), ('Horus, Pillar of His Mother'), depicted as a priest wearing a leopard-skin over torso in the Tomb of Nefertari, Valley of the Queens

Her-iunmutef (Iunmutef), ('Horus, Pillar of His Mother'), depicted as a priest wearing a leopard-skin over torso in the Tomb of Nefertari, Valley of the Queens

-

Herui, the 5th nome god of Upper Egypt in Coptos besides the pharaoh Sahure

Herui, the 5th nome god of Upper Egypt in Coptos besides the pharaoh Sahure

Celebrations of Horus

The Festival of Victory (Egyptian: Heb Nekhtet) was an annual Egyptian festival dedicated to the god Horus. The Festival of Victory was celebrated at the Temple of Horus at Edfu, and took place during the second month of the Season of the Emergence (or the sixth month of the Egyptian calendar).

The ceremonies which took place during the Festival of Victory included the performance of a sacred drama which commemorated the victory of Horus over Set. The main actor in this drama was the king of Egypt himself, who played the role of Horus. His adversary was a hippopotamus, who played the role of Set. In the course of the ritual, the king would strike the hippopotamus with a harpoon. The destruction of the hippopotamus by the king commemorated the defeat of Set by Horus, which also legitimised the king.