| Revision as of 22:41, 9 December 2007 view sourceIllnab1024 (talk | contribs)1,148 edits Big RV← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 13:19, 9 January 2025 view source Gardenofedenn (talk | contribs)65 editsNo edit summaryTag: Visual edit | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Queen Victoria's reign}} | |||

| {| class="infobox" style="width:25em; text-align:left; font-size:95%;" | |||

| {{good article}} | |||

| |+ style="padding-top:0.5em; font-size:130%;"| '''Victorian era''' | |||

| {{pp|small=yes}} | |||

| |- | |||

| {{Use British English|date=June 2013}} | |||

| |colspan=2 align=center| ] ''']—]''' | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=October 2020}} | |||

| |- | |||

| {{stack begin}} | |||

| ! Preceded by | |||

| {{Infobox historical era | |||

| | ] | |||

| |name = Victorian era | |||

| |- | |||

| |start = 1837 | |||

| ! Followed by | |||

| |end = 1901 | |||

| | ] | |||

| |image = Queen Victoria - Winterhalter 1859.jpg | |||

| |- | |||

| |alt = | |||

| ! Monarch | |||

| | |

|caption = Painting of ] by ] (1859) | ||

| |before = ] | |||

| |colspan="0" style="font-size:smaller;"| {{{footnotes|}}} | |||

| |after = ] | |||

| |} | |||

| |monarch = ] | |||

| |leaders = {{Unbulleted list | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |]}} | |||

| |year_start=1837|year_end=1901 | |||

| }} | |||

| {{History of the United Kingdom}} | |||

| {{Periods in English History}} | |||

| {{History of Scotland}} | |||

| {{stack end}} | |||

| In the ] and the ], the '''Victorian era''' was the reign of ], from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. Slightly different definitions are sometimes used. The era followed the ] and preceded the ], and its later half overlaps with the first part of the '']'' era of continental Europe. | |||

| {{Cleanup|date=September 2007}} | |||

| Various liberalising political reforms took place in the UK, including expanding the electoral franchise. The ] caused mass death in ] early in the period. The British Empire had relatively peaceful relations with the other ]s. It participated in various military conflicts mainly against minor powers. The British Empire expanded during this period and was the predominant power in the world. | |||

| The '''Victorian era''' of the ] marked the height of the British ] and the apex of the ]. Although commonly used to refer to the period of ] rule between 1837 and 1901, scholars debate whether the Victorian period—as defined by a variety of sensibilities and political concerns that have come to be associated with the Victorians—actually begins with the passage of the ]. The era was preceded by the ] and succeeded by the ]. The latter half of the Victorian era roughly coincided with the first portion of the ] era of continental Europe and other non-English speaking countries. | |||

| Victorian society valued a high standard of personal conduct across all sections of society. The ] gave impetus to social reform but also placed restrictions on certain groups' liberty. Prosperity rose during the period, but debilitating ] persisted. Literacy and childhood education became near universal in ] for the first time. Whilst some attempts were made to improve living conditions, ] housing and disease remained a severe problem. | |||

| ==Introduction== | |||

| Queen Victoria had the ], and the cultural, political, economic, industrial and scientific changes that occurred during her reign were remarkable. When Victoria ascended to the throne, Britain was primarily ] and ] (though it was even then the most industrialised country in the world); upon her death, the country was highly ] and connected by an expansive ]. The first decades of Victoria's reign witnessed a series of epidemics (] and ], most notably), crop failures and economic collapses. There were riots over ] and the repeal of the ], which had been established to protect British agriculture during the ] in the early part of the 19th century. ] ]) gave her name to the historic era]] | |||

| The period saw significant scientific and technological development. Britain was advanced in industry and engineering in particular. Great Britain's population increased rapidly, while Ireland's fell sharply. Technologically, this era saw a staggering amount of innovations that proved key to Britain's power and prosperity.<ref name=":12">{{Cite book |last=Dutton |first=Edward |title=At Our Wits' End: Why We're Becoming Less Intelligent and What It Means for the Future |last2=Woodley of Menie |first2=Michael |publisher=Imprint Academic |year=2018 |isbn=9781845409852 |location=Great Britain |pages=85, 95-6 |chapter=Chapter 7: How Did Selection for Intelligence Go Into Reverse?}}</ref><ref name=":17">{{Cite web |last=Atterbury |first=Paul |date=17 February 2011 |title=Victorian Technology |url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/victorians/victorian_technology_01.shtml |access-date=13 October 2020 |website=BBC History}}</ref> Multiple studies suggest that on the per-capita basis, the numbers of significant innovations in science and technology and of scientific geniuses peaked during the Victorian era and have been on the decline ever since.<ref name=":20">{{Cite journal |last=Woodley of Menie |first=Michael |last2=te Nijenhuis |first2=Jan |last3=Murphy |first3=Raegan |date=November–December 2013 |title=Were the Victorians cleverer than us? The decline in general intelligence estimated from a meta-analysis of the slowing of simple reaction time |url=https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2013.04.006 |journal=Intelligence |volume=41 |issue=6 |pages=843–50}}</ref> | |||

| Discoveries by ] and ] began to examine centuries of assumptions about man and the world, about science and history, and, finally, about religion and philosophy. As the country grew increasingly connected by an expansive network of railway lines, small, previously isolated communities were exposed and entire economies shifted as cities became more and more accessible. | |||

| ==Terminology and periodisation== | |||

| The mid-Victorian period also witnessed significant social changes: an evangelical revival occurred alongside a series of legal changes in women's rights. While women were not enfranchised during the Victorian period, they did gain the legal right to their property upon marriage through the ], the right to divorce, and the right to fight for custody of their children upon separation. | |||

| {{see also|Periodisation}} | |||

| In the strictest sense, the Victorian era covers the duration of Victoria's reign as ], from her accession on 20 June 1837—after the death of her uncle, ]—until her death on 22 January 1901, after which she was succeeded by her eldest son, ]. Her reign lasted 63 years and seven months, a longer period than any of her predecessors. The term 'Victorian' was in contemporaneous usage to describe the era.{{sfn|Plunkett|2012|page=2}} The era can also be understood in a more extensive sense—the 'long Victorian era'—as a period that possessed sensibilities and characteristics distinct from the periods adjacent to it,{{NoteTag|This is the term used for the period covered by Patrick Leary's international academic mailing-list ''VICTORIA 19th-century British culture & society''.}} in which case it is sometimes dated to begin before Victoria's accession—typically from the passage of or agitation for (during the 1830s) the ], which introduced a wide-ranging change to the ] of ].{{NoteTag|A Scottish Reform Act and Irish Reform Act were passed separately.}} Definitions that purport a distinct sensibility or politics to the era have also created scepticism about the worth of the label 'Victorian', though there have also been defences of it.<ref name="hewitt20062">{{cite journal |last1=Hewitt |first1=Martin |date=Spring 2006 |title=Why the Notion of Victorian Britain Does Make Sense |url=http://muse.jhu.edu/article/204106 |url-status=live |journal=Victorian Studies |volume=48 |issue=3 |pages=395–438 |doi=10.2979/VIC.2006.48.3.395 |s2cid=143482564 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171030004144/http://muse.jhu.edu/article/204106 |archive-date=30 October 2017 |access-date=23 May 2017 | issn = 0042-5222 }}</ref> | |||

| The period is often characterised as a long period of peace and economic, colonial, and industrial consolidation, temporarily disrupted by the ], although Britain was at war every year during this period. Towards the end of the century, the policies of ] led to increasing colonial conflicts and eventually the ] and the ]. Domestically, the agenda was increasingly liberal with a number of shifts in the direction of gradual political reform and the widening of the franchise. | |||

| ] was insistent that "in truth, the Victorian period is three periods, and not one".<ref>{{Cite book |last=Sadleir |first=Michael |title=Trollope |year=1945 |pages=17}}</ref> He distinguished early Victorianism—the socially and politically unsettled period from 1837 to 1850<ref>{{Cite book |last=Sadleir |first=Michael |title=Trollope |year=1945 |pages=18–19}}</ref>—and late Victorianism (from 1880 onwards), with its new waves of ] and ],<ref>{{Cite book |last=Sadleir |first=Michael |title=Trollope |year=1945 |pages=13 and 32}}</ref> from the Victorian heyday: mid-Victorianism, 1851 to 1879. He saw the latter period as characterised by a distinctive mixture of prosperity, domestic ]ry, and complacency<ref>{{Cite book |last=Michael |first=Sadleir |title=Trollope |year=1945 |pages=25–30}}</ref>—what ] called the 'mid-Victorian decades of quiet politics and roaring prosperity'.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Trevelyan |first=George Macaulay |title=History of England |publisher=Longmans, Green and Co |year=1926 |pages=650 |oclc=433219629}}</ref> | |||

| In the early part of the era the ] was dominated by the two parties, the ] and the ]. From the late 1850s onwards the Whigs became the ] even as the Tories became known as the ]. Many prominent statesmen led one or other of the parties, including ], Sir ], ], ], ], ] and ]. The unsolved problems relating to ] played a great part in politics in the later Victorian era, particularly in view of Gladstone's determination to achieve a political settlement. | |||

| ==Politics, diplomacy and war== | |||

| In May of 1857, the ], a widespread revolt in India against the rule of the ], was sparked by '']s'' (native Indian soldiers) in the Company's army. The rebellion, involving not just sepoys but many sectors of the Indian population as well, was largely quenched after a year. In response to the Mutiny, the East India Company was abolished in August 1858 and India came under the direct rule of the ], beginning the period of the ]. | |||

| {{main|Political and diplomatic history of the Victorian era|United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland}} | |||

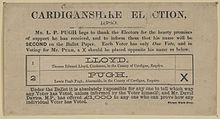

| ], a candidate at the ] in ] (now known as Ceredigion), explaining to supporters how to vote.]] | |||

| The ],{{NoteTag|A Scottish Reform Act and Irish Reform Act were passed separately.}} which made various changes to the electoral system including expanding the franchise, had been passed in 1832.<ref name= "greenhavenpress2">{{Cite book |last=Swisher |first=Clarice |title= Victorian England |publisher=San Diego: Greenhaven Press |year=2000 |isbn=9780737702217 |pages=248–250}}</ref> The franchise was expanded again by the ]{{NoteTag|See ] and ] for equivalent reforms made in those jurisdictions}} in 1867.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Anstey |first=Thomas Chisholm |url= https://books.google.com/books?id=OrEDAAAAQAAJ&dq=passed+parliament+date+%22The+Representation+of+the+People+Act+1867,+30+&pg=PA169 |title=Notes Upon "the Representation of the People Act, '1867.'" (30 & 31 Vict. C. 102.): With Appendices Concerning the Antient Rights, the Rights Conferred by the 2 & 3 Will. IV C. 45, Population, Rental, Rating, and the Operation of the Repealed Enactments as to Compound Householders |date=1867 |publisher= W. Ridgway |language=en |access-date= 11 May 2023 |archive-date=11 May 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230511230919/https://books.google.com/books?id=OrEDAAAAQAAJ&dq=passed+parliament+date+%22The+Representation+of+the+People+Act+1867,+30+&+31+Vict.+c.+102%22&pg=PA169 |url-status=live }}</ref> The ] in 1884 introduced a general principle of one vote per household. All these acts and others simplified the electoral system and reduced corruption. Historian Bruce L Kinzer describes these reforms as putting the United Kingdom on the path towards becoming a democracy. The traditional aristocratic ruling class attempted to maintain as much influence as possible while gradually allowing the middle- and working-classes a role in politics. However, all women and a large minority of men remained outside the system into the early 20th century.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Kinzer |first=Bruce L |title=Victorian Britain An Encyclopedia |publisher=Routledge |year=2011 |isbn=9780415669726 |editor-last=Mitchell |editor-first=Sally |pages=253–255 |chapter=Elections and the Franchise}}</ref> | |||

| : | |||

| Cities were given greater political autonomy and the ] was legalised.<ref name="NatGeo-20072">{{Cite book |last=National Geographic |title=Essential Visual History of the World |publisher=National Geographic Society |year=2007 |isbn=978-1-4262-0091-5 |pages=290–292}}</ref> From 1845 to 1852, the ] caused mass starvation, disease and death in Ireland, sparking large-scale emigration.<ref name="kinealyxv2">{{Cite book |last=Kinealy |first=Christine |title=This Great Calamity |publisher=Gill & Macmillan |year=1994 |isbn= 9781570981401 |page=xv}}</ref> The ] were repealed in response to this.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Lusztig |first1=Michael |date=July 1995 |title=Solving Peel's Puzzle: Repeal of the Corn Laws and Institutional Preservation |journal= Comparative Politics |volume=27 |issue=4 |pages=393–408 |doi= 10.2307/422226 |jstor=422226}}</ref> Across the British Empire, reform included rapid expansion, the complete abolition of slavery in the African possessions and the end of ]. Restrictions on colonial trade were loosened and responsible (i.e. semi-autonomous) government was introduced in some territories.<ref name="Rose-194022">{{Cite journal |author=Livingston Schuyler |first= Robert |date=September 1941 |title= The Cambridge History of the British Empire. Volume II: The Growth of the New Empire, 1783-1870 |journal= Political Science Quarterly |volume=56 |issue=3 |page=449 |doi= 10.2307/2143685 |issn=0032-3195 |jstor=2143685}}</ref><ref name="Benians-19592">{{Cite book |last= Benians |first=E. A. |title=The Cambridge History of the British Empire Vol. iii: The Empire – Commonwealth 1870–1919 |year=1959 |isbn=978-0521045124 |pages=1–16|publisher=Cambridge University Press }}</ref>] during the ] of 1879 by ] (1880)]] | |||

| Throughout most of the 19th century Britain was the most powerful country in the world.<ref>{{Cite book |last= Sandiford |first=Keith A. |title=Victorian Britain An Encyclopedia |publisher= Routledge |year=2011 |isbn= 9780415669726 |editor-last=Mitchell |editor-first=Sally |pages=307–309 |chapter=Foreign relations}}</ref> The period from ], known as the ], was a time of relatively peaceful relations between the world's ]s. This is particularly true of Britain's interactions with the others.<ref>{{Cite book |last= Holland |first=Rose, John |title=The Cambridge history of the British empire: volume II: the growth of the new empire, 1783-1870 |date=1940 |pages= x–vi |oclc=81942369}}</ref> The only war in which the British Empire fought against another major power was the ], from 1853 to 1856.<ref name="taylor60-612">{{cite book |last=Taylor |first=A. J. P. |url= https://archive.org/details/dli.bengal.10689.13016 |title=The Struggle for Mastery in Europe: 1848–1918 |date= 1954 |publisher= Oxford University Press | location = Mumbai |pages=60–61}}</ref><ref name="Rose-194022" /> There were various revolts and violent conflicts within the British Empire,<ref name="Rose-194022" /><ref name="Benians-19592" /> and Britain participated in wars against minor powers.<ref name="swisher248-502">{{Cite book |last=Swisher |first= Clarice |url= https://archive.org/details/victorianengland00swis/page/n5/mode/2up |title=Victorian England |publisher= Greenhaven Press |year=2000 |isbn= 9780737702217 |pages=248–250}}</ref><ref name="Rose-194022" /><ref name="Benians-19592" /> It also took part in the diplomatic struggles of the ]<ref name= "swisher248-502" /> and the ].<ref name= "Rose-194022" /><ref name="Benians-19592" /> | |||

| In January 1858, the Prime Minister ] responded to the ] plot against ] emperor ], the bombs for which were purchased in ], by attempting to make such acts a felony, but the resulting uproar forced him to resign. | |||

| In 1840, Queen Victoria married her German cousin ]. The couple had nine children, who themselves married into various royal families, and the queen thus became known as the 'grandmother of Europe'.<ref name="BBC Teach2">{{Cite web |title=Queen Victoria: The woman who redefined Britain's monarchy |url= https://www.bbc.co.uk/teach/ks3-gcse-history-queen-victoria-monarchy/z73rnrd |access-date=12 October 2020 |website=BBC Teach |archive-date=27 November 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201127013659/https://www.bbc.co.uk/teach/ks3-gcse-history-queen-victoria-monarchy/z73rnrd |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="NatGeo-20072" /> In 1861, Albert died.<ref name= "swisher248-502" /> Victoria went into mourning and withdrew from public life for ten years.<ref name= "NatGeo-20072" /> In 1871, with ] sentiments growing in Britain, she began to return to public life. In her later years, her popularity soared as she became a symbol of the British Empire. Queen Victoria died on 22 January 1901.<ref name="BBC Teach2" /> | |||

| In July 1866, an angry crowd in London, protesting ]'s resignation as prime minister, was barred from ] by the police; they tore down iron railings and trampled the flower beds. Disturbances like this convinced Derby and Disraeli of the need for further parliamentary reform. | |||

| ==Society and culture== | |||

| During 1875, Britain purchased ]'s shares in the ] as the African nation was forced to raise money to pay off its debts. | |||

| {{Main|Society and culture of the Victorian era}} | |||

| ===Family life=== | |||

| The Victorian era saw a rapidly growing ] who became an important cultural influence, to a significant extent replacing the ] as British society's dominant class.<ref name="houghton12">{{Cite book |last=Houghton |first=Walter E. |date=2008 |title=The Victorian Frame of Mind |location=New Haven |publisher=Yale University Press |doi=10.12987/9780300194289|isbn=9780300194289 |s2cid=246119772 }}</ref><ref name="Halévy-1924">{{Cite book |last=Halévy |first=Élie |title=A history of the English people ... |publisher=T. F. Unwin |date=1924 |pages=585–595 |oclc=1295721374}}</ref> A distinctive middle-class lifestyle developed that influenced what society valued as a whole.<ref name="houghton12" />''<ref name="Wohl-19782">{{cite book |last=Wohl |first=Anthony S. |title=The Victorian family: structure and stresses |publisher=Croom Helm |year=1978 |isbn=9780856644382 |location=London}}<br /><br />: ''Cited in'': {{cite book |last=Summerscale |first=Kate |url=https://archive.org/details/isbn_9780747582151 |title=The suspicions of Mr. Whicher or the murder at Road Hill House |publisher=Bloomsbury |year=2008 |isbn=9780747596486 |location=London |pages= |author-link=Kate Summerscale |url-access=registration |ref=none}} (novel)</ref>'' Increased importance was placed on the value of the family, and the idea that marriage should be based on romantic love gained popularity.<ref name="K2">{{Cite book |last=Theodore. |first=Hoppen, K. |title=The Mid-Victorian Generation 1846-1886 |date=30 June 2000 |isbn=978-0-19-254397-4 |pages=316 |publisher=Oxford University Press |oclc=1016061494}}</ref><ref name="Boston-20192">{{Cite web |last=Boston |first=Michelle |date=12 February 2019 |title=Five Victorian paintings that break tradition in their celebration of love |url=https://dornsife.usc.edu/news/stories/2948/five-victorian-paintings-break-tradition/ |access-date=18 December 2020 |website=USC Dornsife |publisher=University of Southern California |archive-date=10 February 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210210193513/https://dornsife.usc.edu/news/stories/2948/five-victorian-paintings-break-tradition/ |url-status=live }}</ref> A clear separation was established between the home and the workplace, which had often not been the case before.''<ref name="Wohl-19782" />'' The home was seen as a private environment,''<ref name="Wohl-19782" />'' where housewives provided their husbands with a respite from the troubles of the outside world.<ref name="K2" /> Within this ideal, women were expected to focus on domestic matters and to rely on men as breadwinners.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Robyn Ryle |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=CHHz_p-j9hMC&pg=PA342 |title=Questioning gender: a sociological exploration |publisher=SAGE/Pine Forge Press |year=2012 |isbn=978-1-4129-6594-1 |location=Thousand Oaks, Calif. |pages=342–343}}</ref><ref name="Rubinow-1992">{{Cite book |last=Rubinow. |first=Gorsky, Susan |title=Femininity to feminism: women and literature in the Nineteenth century |date=1992 |publisher=Twayne Publishers |isbn=0-8057-8978-2 |oclc=802891481}}</ref> Women had limited legal rights in most areas of life, and a ] movement developed.<ref name="Rubinow-1992" /><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Gray |first1=F. Elizabeth |year=2004 |title="Angel of the House" in Adams, ed. |journal=Encyclopedia of the Victorian Era |volume=1 |issue= |pages=40–41}}</ref> Parental authority was seen as important, but children were given ] for the first time towards the end of the period.<ref name="Bilston-20192">{{Cite web |last=Bilston |first=Barbara |date=4 July 2010 |title=A history of child protection |url=https://www.open.edu/openlearn/body-mind/childhood-youth/working-young-people/history-child-protection |access-date=2022-06-12 |website=Open University |language=en |archive-date=24 June 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210624202903/https://www.open.edu/openlearn/body-mind/childhood-youth/working-young-people/history-child-protection |url-status=live }}</ref> Access to education increased rapidly during the 19th century. State-funded schools were established in England and Wales for the first time. Education became compulsory for pre-teenaged children in England, Scotland and Wales. Literacy rates increased rapidly, and had become nearly universal by the end of the century.<ref name="Lloyd-20072">{{Cite web |last=Lloyd |first=Amy |date=2007 |title=Education, Literacy and the Reading Public |url=https://www.gale.com/binaries/content/assets/gale-us-en/primary-sources/intl-gps/intl-gps-essays/full-ghn-contextual-essays/ghn_essay_bln_lloyd3_website.pdf |publisher=University of Cambridge |access-date=27 January 2022 |archive-date=20 May 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210520183852/https://www.gale.com/binaries/content/assets/gale-us-en/primary-sources/intl-gps/intl-gps-essays/full-ghn-contextual-essays/ghn_essay_bln_lloyd3_website.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=The 1870 Education Act |url=https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/livinglearning/school/overview/1870educationact/ |website=UK Parliament}}</ref> Private education for wealthier children, boys and more gradually girls, became more formalised over the course of the century.<ref name="Lloyd-20072" /> | |||

| ===Religion and social issues=== | |||

| The growing middle class and strong ] placed great emphasis on a respectable and moral code of behaviour. This included features such as charity, personal responsibility, controlled habits,{{NoteTag|Avoiding addictions such as ] and excessive ]}} ] and self-criticism.<ref name="Halévy-1924" /><ref>{{Cite book |last=Young |first=G. M. |title=Victorian England: Portrait of an Age |year=1936 |pages=1–6}}</ref> As well as personal improvement, importance was given to social reform.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Briggs |first=Asa |title=The Age of Improvement 1783–1867 |year=1957 |pages=236–285}}</ref> ] was another philosophy that saw itself as based on science rather than on morality, but also emphasised social progress.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Roach |first=John |date=1957 |title=Liberalism and the Victorian Intelligentsia |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/3020631 |journal=The Cambridge Historical Journal |volume=13 |issue=1 |pages=58–81 |doi=10.1017/S1474691300000056 |jstor=3020631 |issn=1474-6913 |access-date=2 September 2020 |archive-date=2 September 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200902130752/https://www.jstor.org/stable/3020631/ |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Young |first=G. M. |title=Victorian England: Portrait of an Age |pages=10–12}}</ref> An alliance formed between these two ideological strands.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Halevy |first=Elie |url= |title=A History Of The English People In 1815 |date=1924 |pages=585–95}}</ref> The reformers emphasised causes such as improving the conditions of women and children, giving police reform priority over harsh punishment to prevent crime, religious equality, and political reform in order to establish a democracy.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Woodward |first=Llewellyn |title=The Age of Reform, 1815–1870 |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=1962 |edition=2nd |pages=28, 78–90, 446, 456, 464–465}}</ref> The political legacy of the reform movement was to link the ] (part of the evangelical movement) in England and Wales with the ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Bebbington |first=D. W. |title=The Nonconformist Conscience: Chapel and Politics, 1870–1914 |publisher=George Allen & Unwin, 1982 |year=1982}}</ref> This continued until the ].<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Glaser |first1=John F. |year=1958 |title=English Nonconformity and the Decline of Liberalism |journal=The American Historical Review |volume=63 |issue=2 |pages=352–363 |doi=10.2307/1849549 |jstor=1849549}}</ref> The ] played a similar role as a religious voice for reform in Scotland.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Wykes |first1=David L. |year=2005 |title=Introduction: Parliament and Dissent from the Restoration to the Twentieth Century |journal=Parliamentary History |volume=24 |issue=1 |pages=1–26 |doi=10.1111/j.1750-0206.2005.tb00399.x}}</ref> | |||

| Religion was politically controversial during this era, with Nonconformists pushing for the ] of the ].<ref name="Owen Chadwick2">{{Cite book |last=Chadwick |first=Owen |title=The Victorian church |publisher=A. & C. Black |year=1966 |isbn=978-0334024095 |volume=1 |pages=7–9, 47–48}}</ref> Nonconformists comprised about half of church attendees in England in 1851,{{NoteTag|They were a clear majority in Wales. Scotland and Ireland had separate religious cultures.}}<ref>{{Cite book |last=Johnson |first=Dale A. |title=Victorian Britain An Encyclopedia |publisher=Routledge |year=2011 |isbn=9780415669726 |editor-last=Mitchell |editor-first=Sally |pages=546–547 |chapter=Nonconformism}}</ref> and gradually the legal discrimination that had been established against them outside of Scotland was removed.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Machin |first=G. I. T. |year=1979 |title=Resistance to Repeal of the Test and Corporation Acts, 1828 |journal=The Historical Journal |volume=22 |issue=1 |pages=115–139 |doi=10.1017/s0018246x00016708 |s2cid=154680968 |issn=0018-246X}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Davis |first1=R. W. |year=1966 |title=The Strategy of "Dissent" in the Repeal Campaign, 1820–1828 |journal=The Journal of Modern History |volume=38 |issue=4 |pages=374–393 |doi=10.1086/239951 |jstor=1876681 |s2cid=154716174}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Anderson |first=Olive |author-link=Olive Anderson|year=1974 |title=Gladstone's Abolition of Compulsory Church Rates: a Minor Political Myth and its Historiographical Career |journal=The Journal of Ecclesiastical History |volume=25 |issue=2 |pages=185–198 |doi=10.1017/s0022046900045735 |s2cid=159668040 |issn=0022-0469}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Bowen |first=Desmond |year=1979 |title=''Conscience of the Victorian State'', edited by Peter Marsh |journal=Canadian Journal of History |volume=14 |issue=2 |pages=318–320 |doi=10.3138/cjh.14.2.318 |issn=0008-4107}}</ref> Legal restrictions on ]s were also largely ]. The number of Catholics grew in Great Britain due to ] and ].<ref name="Owen Chadwick2" /> Secularism and doubts about the accuracy of the ] grew among people with higher levels of education.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Coleridge's Religion |url=https://victorianweb.org/previctorian/stc/religion1.html |access-date=2022-08-10 |website=victorianweb.org |archive-date=30 March 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230330103435/https://victorianweb.org/previctorian/stc/religion1.html |url-status=live }}</ref> Northern English and Scottish academics tended to be more religiously conservative, whilst agnosticism and even atheism (though its promotion was illegal)<ref>{{Cite book |last=Chadwick |first=Owen |title=The Victorian Church |year=1966 |volume=1: 1829–1859 |pages=487–489}}</ref> gained appeal among academics in the south.<ref name="Lewis-200732">{{Cite book |last=Lewis |first=Christopher |title=Heat and Thermodynamics: A Historical Perspective |publisher=Greenwood Press |year=2007 |isbn=978-0-313-33332-3 |location=United States of America |chapter=Chapter 5: Energy and Entropy: The Birth of Thermodynamics}}</ref> Historians refer to a 'Victorian Crisis of Faith', a period when religious views had to readjust to accommodate new scientific knowledge and criticism of the Bible.<ref>{{cite book |last=Eisen |first=Sydney |chapter-url=https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-349-10974-6_2 |title=Victorian Faith in Crisis: Essays on Continuity and Change in Nineteenth-Century Religious Belief |publisher=Palgrave Macmillan UK |year=1990 |isbn=9781349109746 |editor-last1=Helmstadter |editor-first1=Richard J. |pages=2–9 |chapter=The Victorian Crisis of Faith and the Faith That was Lost |doi=10.1007/978-1-349-10974-6_2 |editor-last2=Lightman |editor-first2=Bernard |access-date=18 October 2022 |archive-date=19 October 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221019085106/https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-349-10974-6_2 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| In 1882 Egypt became a ] of Great Britain after ] occupied land surrounding the Suez Canal in order to secure the vital ], and the passage to India. | |||

| ===Popular culture=== | |||

| A variety of reading materials grew in popularity during the period, including novels,<ref name="British Library2">{{Cite web |title=Aspects of the Victorian book: the novel |url=http://www.bl.uk/collections/early/victorian/pu_novel.html |access-date=October 23, 2020 |website=British Library |archive-date=24 May 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180524101310/http://www.bl.uk/collections/early/victorian/pu_novel.html |url-status=live }}</ref> women's magazines,<ref name="BritLib-20202">{{Cite web |title=Aspects of the Victorian book: Magazines for Women |url=http://www.bl.uk/collections/early/victorian/pu_magaz.html |access-date=23 October 2020 |website=British Library |archive-date=3 February 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200203044916/http://www.bl.uk/collections/early/victorian/pu_magaz.html |url-status=live }}</ref> children's literature,<ref>{{Cite web |last=McGillis |first=Roderick |date=6 May 2016 |title=Children's Literature - Victorian Literature |url=https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780199799558/obo-9780199799558-0088.xml |access-date=28 October 2020 |website=Oxford Bibliographies |archive-date=31 October 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201031081053/https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780199799558/obo-9780199799558-0088.xml |url-status=live }}</ref> and newspapers.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Weiner |first=Joel H. |title=Victorian Britain An Encyclopedia |publisher=Routledge |year=2011 |isbn=9780415669726 |editor-last=Mitchell |editor-first=Sally |pages=628–630 |chapter=Press, Popular}}</ref> Much literature, including ]s, was distributed on the street.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Richardson |first=Ruth |date=15 May 2014 |title=Street literature |url=https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/street-literature |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220422020111/https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/street-literature |archive-date=22 April 2022 |access-date=2022-04-22 |website=British Library}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=Richardson |first=Ruth |date=15 May 2014 |title=Chapbooks |url=https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/chapbooks |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220422024529/https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/chapbooks |archive-date=22 April 2022 |access-date=2022-04-22 |website=British Library}}</ref> Music was also very popular, with genres such as ], ], ]s, ]s, ] and ] having mass appeal. What is now called ] was somewhat undeveloped compared to parts of Europe but did have significant support.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Mitchell |first=Sally |title=Victorian Britain An Encyclopedia |publisher=Routledge |year=2011 |isbn=9780415669726 |pages=518–520 |chapter=Music}}</ref> ] became an increasingly accessible and popular part of everyday life.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Photocollages Reveal Wit and Whimsy of the Victorian Era in Metropolitan Museum Exhibition Opening February 2 |url= https://www.metmuseum.org/press/exhibitions/2010/photocollages-reveal-wit-and-whimsy-of-the-victorian-era-in-metropolitan-museum-exhibition-opening-february-2 |access-date=18 November 2024 |website=]|date=27 January 2010}}</ref> Many sports were introduced or popularised during the Victorian era.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Baker |first=William J. |title=The state of British sport history |publisher=Journal of Sport History |year=1983 |volume=10 |issue=1 |pages=53–66}}</ref> They became important to male identity.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Maguire |first1=Joe |year=1986 |title=Images of manliness and competing ways of living in late Victorian and Edwardian Britain |journal=International Journal of the History of Sport |volume=3 |issue=3 |pages=265–287 |doi=10.1080/02649378608713604}}</ref> Examples included ],<ref>{{Cite book |last=Sandiford |first=Keith A. P. |title=Victorian Britain An Encyclopedia |publisher=Routledge |year=2011 |isbn=9780415669726 |editor-last=Mitchell |editor-first=Sally |pages=199–200 |chapter=Cricket}}</ref> ],<ref>{{Cite book |last=Seiler |first=Robert M. |title=Victorian Britain An Encyclopedia |publisher=Routledge |year=2011 |isbn=9780415669726 |editor-last=Mitchell |editor-first=Sally |pages=728–729 |chapter=Soccer}}</ref> ],<ref>{{Cite book |last=Sandiford |first=Keith A. P. |title=Victorian Britain An Encyclopedia |publisher=Routledge |year=2011 |isbn=9780415669726 |editor-last=Mitchell |editor-first=Sally |pages=685 |chapter=Rugby football}}</ref> ]<ref>{{Cite book |last=Blouet |first=Olwyn M. |title=Victorian Britain An Encyclopedia |publisher=Routledge |year=2011 |isbn=9780415669726 |editor-last=Mitchell |editor-first=Sally |pages=791 |chapter=Tennis}}</ref> and ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Richard |first=Maxwell |title=Victorian Britain An Encyclopedia |publisher=Routledge |year=2011 |isbn=9780415669726 |editor-last=Mitchell |editor-first=Sally |pages=74–75 |chapter=Bicycle}}</ref> The idea of women participating in sport did not fit well with the Victorian view of femininity, but their involvement did increase as the period progressed.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Kathleen E. |first=McGrone |title=Victorian Britain An Encyclopedia |publisher=Routledge |year=2011 |isbn=9780415669726 |editor-last=Mitchell |editor-first=Sally |pages=750–752 |chapter=Sport and Games, Women}}</ref> For the middle classes, many leisure activities such as ] could be done in the home while ] to rural locations such as the ] and ] were increasingly practical.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Scheuerle H. |first=William |title=Victorian Britain An Encyclopedia |publisher=Routledge |year=2011 |isbn=9780415669726 |editor-last=Mitchell |editor-first=Sally |pages=17–19 |chapter=Amusements and Recreation: Middle class}}</ref> The working classes had their own culture separate from that of their richer counterparts, various cheaper forms of entertainment and recreational activities provided by ]. Trips to resorts such as ] were increasingly popular towards the end of period.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Waters |first=Chris |title=Victorian Britain An Encyclopedia |publisher=Routledge |year=2011 |isbn=9780415669726 |editor-last=Mitchell |editor-first=Sally |pages=19–20 |chapter=Amusements and Recreation: Working class}}</ref> Initially the industrial revolution increased working hours, but over the course of the 19th century a variety of political and economic changes caused them to fall back down to and in some cases below pre-industrial levels, creating more time for leisure.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Cook |first=Bernard A. |title=Victorian Britain An Encyclopedia |publisher=Routledge |year=2011 |isbn=9780415669726 |editor-last=Mitchell |editor-first=Sally |pages=878–879 |chapter=Working hours}}</ref> | |||

| <gallery widths="200" mode="packed"> | |||

| In 1884 the ] was founded in London by a group of ] intellectuals, including ] ], ], and ], to promote socialism. ] and ] would be among many famous names to later join this society. | |||

| File:NiddMuseum1 Victorian Parlour.jpg|Recreation of a Victorian ] at ], Yorkshire | |||

| File:Halfpenny dinners for poor children in East London. Wellcome L0001135.jpg|Cheap meals for poor children in ] (1870) | |||

| File:The Leisure Hour. 1855. George-Hardy.jpg|''Leisure Hours'' (1855), depiction of a man resting by ] | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| ==Economy, industry, and trade== | |||

| On Sunday, ], ], tens of thousands of people, many of them ] or unemployed, gathered in ] to demonstrate against British coercion in Ireland. ] Commissioner Sir ] ordered armed soldiers and 2,000 police constables to respond. Rioting broke out, hundreds were injured and two people died. This event was referred to as ]. | |||

| {{further|Economy, industry, and trade of the Victorian era|Industrial Revolution|Second Industrial Revolution}} | |||

| ], ] in '']'' (1861)]] | |||

| ==Culture== | |||

| This inescapable sense of newness resulted in a deep interest in the relationship between modernity and cultural continuities. ] became increasingly significant in the period, leading to the ] between Gothic and ] ideals. ]'s architecture for the new ], which had been badly damaged in an 1834 fire, built on the medieval style of ], the surviving part of the building. It constructed a narrative of cultural continuity, set in opposition to the violent disjunctions of ], a comparison common to the period, as expressed in ]'s '']'' and ]' '']''. Gothic was also supported by the critic ], who argued that it epitomised communal and inclusive social values, as opposed to Classicism, which he considered to epitomise mechanical standardisation. | |||

| Before the Industrial Revolution, daily life had changed little for hundreds of years. The 19th century saw rapid technological development with a wide range of new inventions. This led Great Britain to become the foremost industrial and trading nation of the time.<ref name="Atterbury-2011">{{Cite web |last=Atterbury |first=Paul |date=17 February 2011 |title=Victorian Technology |url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/victorians/victorian_technology_01.shtml |access-date=13 October 2020 |website=BBC History |archive-date=6 November 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201106232436/http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/victorians/victorian_technology_01.shtml |url-status=live }}</ref> Historians have characterised the mid-Victorian era (1850–1870) as Britain's 'Golden Years',<ref>{{Cite book |last=Porter |first=Bernard |title=Britannia's Burden: The Political Evolution of Modern Britain 1851–1890 |year=1994 |chapter=Chapter 3}}</ref><ref name="Hobsbawn-1995">{{Cite book |last=Hobsbawn |first=Eric |title=The Age of Extremes: The Short Twentieth Century 1914-1991 |publisher=Abacus |year=1995 |isbn=9780349106717 |chapter=Chapter Nine: The Golden Years |author-link=Eric Hobsbawm}}</ref> with ] per person increasing by half. This prosperity was driven by increased industrialisation, especially in textiles and machinery, along with exports to the empire and elsewhere.<ref name="F">{{Cite book |last=Thompson |first=F. M. L. |title=Rise of Respectable Society: A Social History of Victorian Britain, 1830–1900 |year=1988 |pages=211–214}}</ref> The positive economic conditions, as well as a fashion among employers for providing welfare services to their workers, led to relative social stability.<ref name="F" /><ref name="Porter">{{Cite book |last1=Porter |first1=K |title=The Mid-Victorian Generation: 1846–1886 |last2=Hoppen |first2=Theodore |pages=9–11 |chapter=Chapters 1 to 3}}</ref> The ] movement for working-class men to be given the right to vote, which had been prominent in the early Victorian period, dissipated.<ref name="F" /> Government involvement in the economy was limited.<ref name="Porter" /> Only in the ], around a century later, did the country experience substantial economic growth again.<ref name="Hobsbawn-1995" /> But whilst industry was well developed, education and the arts were mediocre.<ref name="Porter" /> Wage rates continued to improve in the later 19th century: real wages (after taking inflation into account) were 65 per cent higher in 1901 compared to 1871. Much of the money was saved, as the number of depositors in savings banks rose from 430,000 in 1831 to 5.2 million in 1887, and their deposits from £14 million to over £90 million.<ref name="J">{{Cite book |last=Marriott |first=J. A. R. |title=Modern England: 1885–1945 |year=1948 |edition=4th |pages=166}}</ref> | |||

| The middle of the century saw ] of 1851, the first ] and showcased the greatest innovations of the century. At its centre was ], an enormous, modular glass and iron structure - the first of its kind. It was condemned by Ruskin as the very model of mechanical dehumanisation in design, but later came to be presented as the prototype of ]. The emergence of photography, which was showcased at the Great Exhibition, resulted in significant changes in Victorian art. ] was influenced by photography (notably in his portrait of Ruskin) as were other ] artists. It later became associated with the ] and ] techniques that would dominate the later years of the period in the work of artists such as ] and ]. | |||

| ===Child labour=== | |||

| ]) pulling a coal tub was originally published in the Children's Employment Commission (Mines) 1842 report.]] | |||

| Children had always played a role in economic life but ] became especially intense during the Victorian era. Children were put to work in a wide range of occupations, but particularly associated with this period are factories. Employing children had advantages, as they were cheap, had limited ability to resist harsh working conditions, and could enter spaces too small for adults. Some accounts exist of happy upbringings involving child labour, but conditions were generally poor. Pay was low, punishments severe, work was dangerous and disrupted children's development (often leaving them too tired to play even in their free time). Early labour could do lifelong harm; even in the 1960s and '70s, the elderly people of industrial towns were noted for their often unusually short stature, deformed physiques, and diseases associated with unhealthy working conditions.<ref name="Smith-2011">{{Cite book |last=Smith |first=W. John |title=Victorian Britain An Encyclopedia |publisher=Routledge |year=2011 |isbn=9780415669726 |editor-last=Mitchell |editor-first=Sally |pages=136–137 |chapter=Child Labor}}</ref> Reformers wanted the children in school; in 1840 only about 20 per cent of the children in London had any schooling.<ref name="cody">{{Cite web |title=Child Labor |url=https://victorianweb.org/history/hist8.html |access-date=2023-04-28 |website=victorianweb.org |archive-date=23 January 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230123112325/https://victorianweb.org/history/hist8.html |url-status=live }}</ref> By the 1850s, around half of the children in England and Wales were in school (not including ]).<ref name="Lloyd-2007">{{Cite web |last=Lloyd |first=Amy |date=2007 |title=Education, Literacy and the Reading Public |url=https://www.gale.com/binaries/content/assets/gale-us-en/primary-sources/intl-gps/intl-gps-essays/full-ghn-contextual-essays/ghn_essay_bln_lloyd3_website.pdf |publisher=University of Cambridge |access-date=27 January 2022 |archive-date=20 May 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210520183852/https://www.gale.com/binaries/content/assets/gale-us-en/primary-sources/intl-gps/intl-gps-essays/full-ghn-contextual-essays/ghn_essay_bln_lloyd3_website.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> From the 1833 Factory Act onwards, attempts were made to get child labourers into part time education, though this was often difficult to achieve.<ref name="May-1994">{{Cite book |last=May |first=Trevor |title=The Victorian Schoolroom |publisher=Shire Publications |year=1994 |location=Great Britain |pages=3, 29 |language=EN}}</ref> Only in the 1870s and 1880s did children begin to be compelled into school.<ref name="Lloyd-2007" /> Work continued to inhibit children's schooling into the early 20th century.<ref name="Smith-2011" /> | |||

| == Housing and public health == | |||

| ==Social institutions== | |||

| {{Further|Economy, industry, and trade of the Victorian era|Mathematics, science, technology and engineering of the Victorian era|Demographics of the Victorian era}} | |||

| Prior to the Industrial Revolution, Britain had a very rigid ] consisting of three distinct ]: the ] and ], the ], and the ]. | |||

| 19th-century Britain saw a huge population increase accompanied by rapid urbanisation stimulated by the Industrial Revolution.<ref name="J2">{{Cite book |last=Marriott |first=J. A. R. |title=Modern England: 1885–1945 |year=1948 |edition=4th |pages=166}}</ref> In the ], more than three out of every four people were classified as living in an urban area, compared to one in five a century earlier.<ref name="Chapman Sharpe-2011">{{Cite book |last=Chapman Sharpe |first=William |title=Victorian Britain An Encyclopedia |publisher=Routledge |year=2011 |isbn=9780415669726 |editor-last=Mitchell |editor-first=Sally |pages=162–164 |chapter=Cities}}</ref> Historian Richard A. Soloway wrote that "Great Britain had become the most urbanized country in the West."<ref name="Soloway-2011">{{Cite book |last=Soloway |first=Richard A. |title=Victorian Britain An Encyclopedia |publisher=Routledge |year=2011 |isbn=9780415669726 |editor-last=Mitchell |editor-first=Sally |pages=617–618 |chapter=Population and demographics}}</ref> The rapid growth in the urban population included the new industrial and manufacturing cities, as well as service centres such as ] and London.<ref name="Chapman Sharpe-2011" /><ref>{{Cite book |last=Theerman |first=Paul |title=Victorian Britain An Encyclopedia |publisher=9780415669726 |year=2011 |isbn=9780415669726 |editor-last=Mitchell |editor-first=Sally |pages=237–238 |chapter=Edinburgh}}</ref> Private renting from housing landlords was the dominant tenure. P. Kemp says this was usually of advantage to tenants.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Kemp |first1=P. |year=1982 |title=Housing landlordism in late nineteenth-century Britain |journal=Environment and Planning A |volume=14 |issue=11 |pages=1437–1447 |doi=10.1068/a141437 |bibcode=1982EnPlA..14.1437K |s2cid=154957991}}</ref> Overcrowding was a major problem with seven or eight people frequently sleeping in a single room. Until at least the 1880s, sanitation was inadequate in areas such as water supply and disposal of sewage. This all had a negative effect on health, especially that of the impoverished young. For instance, of the babies born in ] in 1851, only 45 per cent survived to age 20.<ref name="Cook-2011">{{Cite book |last=Cook |first=Bernard A. |title=Victorian Britain An Encyclopedia |publisher=Routledge |year=2011 |isbn=9780415669726 |editor-last=Mitchell |editor-first=Sally |pages=622–625 |chapter=Poverty}}</ref> Conditions were particularly bad in London, where the population rose sharply and poorly maintained, overcrowded dwellings became slum housing. ] wrote of the situation:<ref name="dan2">{{Cite web |title=Poverty and Families in the Victorian Era |url=http://www.hiddenlives.org.uk/articles/poverty.html |access-date=2023-04-28 |website=www.hiddenlives.org.uk |language=en |archive-date=6 December 2008 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081206083852/http://www.hiddenlives.org.uk/articles/poverty.html |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| {{Blockquote|text=Hideous slums, some of them acres wide, some no more than crannies of obscure misery, make up a substantial part of the metropolis... In big, once handsome houses, thirty or more people of all ages may inhabit a single room}} | |||

| The ], known as the aristocracy, included the Church and ] and had great power and wealth. This class consisted of about two percent of the population, who were born into nobility and who owned the majority of the land. It included the ], lords spiritual and temporal, the ], great officers of state, and those above the degree of ]. These people were privileged and avoided taxes. | |||

| Hunger and poor diet was a common aspect of life across the UK in the Victorian period, especially in the 1840s, but the mass starvation seen in the ] in Ireland was unique.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Goodman |first=Ruth |title=How to be a Victorian |publisher=Penguin. |year=2013 |isbn=978-0-241-95834-6 |chapter=Chapter 6: Breakfast: Hunger}}</ref><ref name="Cook-2011" /> Levels of poverty fell significantly during the 19th century from as much as two thirds of the population in 1800 to less than a third by 1901. However, 1890s studies suggested that almost 10% of the urban population lived in a state of desperation lacking the food necessary to maintain basic physical functions. Attitudes towards the poor were often unsympathetic and they were frequently blamed for their situation. In that spirit, the ] had been deliberately designed to punish them and would remain the basis for welfare provision into the 20th century. While many people were prone to vices, not least alcoholism, historian Bernard A. Cook argues that the main reason for 19th century poverty was that typical wages for much of the population were simply too low. Barely enough to provide a subsistence living in good times, let alone save up for bad.<ref name="Cook-2011" /> | |||

| The middle class or ] was made up of factory owners, bankers, shopkeepers, merchants, lawyers, engineers, businessmen, traders, and other professionals. These people could be sometimes extremely rich, but in normal circumstances they were not privileged, and they especially resented this. There was a very large gap between the middle class and the lower class. | |||

| Improvements were made over time to housing along with the management of sewage and water eventually giving the UK the most advanced system of public health protection anywhere in the world.<ref name="Robinson-201152">{{Cite web |last=Robinson |first=Bruce |date=17 February 2011 |title=Victorian Medicine – From Fluke to Theory |url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/victorians/victorian_medicine_01.shtml |access-date=13 October 2020 |website=BBC History |archive-date=8 November 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201108110941/http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/victorians/victorian_medicine_01.shtml |url-status=live }}</ref> The quality and safety of household lighting improved over the period with ]s becoming the norm in the early 1860s, ] in the 1890s and ]s beginning to appear in the homes of the richest by the end of the period.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Loomis |first=Abigail A. |title=Victorian Britain An Encyclopedia |publisher=Routledge |year=2011 |isbn=9780415669726 |editor-last=Mitchell |editor-first=Sally |pages=452–453 |chapter=Lighting}}</ref> Medicine advanced rapidly during the 19th century and ] was developed for the first time. Doctors became more specialised and the number of hospitals grew.<ref name="Robinson-201152" /> The overall number of deaths fell by about 20%. The life expectancy of women increased from around 42 to 55 and 40 to 56 for men.{{NoteTag|These life expectancy figures are rounded to the nearest whole.}}<ref name="Soloway-2011" /> In spite of this, the ] fell only marginally, from 20.8 per thousand in 1850 to 18.2 by the end of the century. Urbanisation aided the spread of diseases and squalid living conditions in many places exacerbated the problem.<ref name="Robinson-201152" /> The population of England, Scotland and Wales grew rapidly during the 19th century.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Jefferies |first=Julie |year=2005 |title=The UK population: past, present and future |url=https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20060215211500/http://www.statistics.gov.uk/downloads/theme_compendia/fom2005/01_FOPM_Population.pdf |access-date=2023-04-29 |website=webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk |pages=3 to 4 |archive-date=29 April 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230429012738/https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20060215211500/http://www.statistics.gov.uk/downloads/theme_compendia/fom2005/01_FOPM_Population.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> Various factors are considered contributary to this, including a rising ] (though it was falling by the end of the period),<ref name="Soloway-2011" /> the lack of a catastrophic pandemic or famine in the island of Great Britain during the 19th century for the first time in history,<ref name="victorian_mortality22">{{cite journal |last=Szreter |first=Simon |year=1988 |title=The importance of social intervention in Britain's mortality decline c.1850–1914: A re-interpretation of the role of public health |journal=Social History of Medicine |volume=1 |pages=1–37 |doi=10.1093/shm/1.1.1 |s2cid=34704101}} {{Subscription required}}</ref> improved nutrition,<ref name="victorian_mortality22" /> and a lower overall mortality rate.<ref name="victorian_mortality22" /> Ireland's population shrank significantly, mostly due to emigration and the Great Famine.<ref>{{cite web |title=Ireland – Population Summary |url=http://homepage.tinet.ie/~cronews/geog/census/popcosum.html |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110728111229/http://homepage.tinet.ie/~cronews/geog/census/popcosum.html |archive-date=28 July 2011 |access-date=10 August 2010 |publisher=Homepage.tinet.ie}}</ref> | |||

| The British lower class was divided into two sections: "the working class" (labourers), and "the poor" (those who were not working, or not working regularly, and were receiving public charity). The lower class contained men, women, and children performing many types of labour, including factory work, ], ]ing, mining, and other jobs. Both the poorer class and the middle class had to endure a large burden of tax. This third class consisted of about eighty-five percent of the population. | |||

| <gallery widths="180" heights="200" mode="packed"> | |||

| Industrialisation changed the class structure dramatically in the late 18th century. Hostility was created between the upper and lower classes. As a result of industrialisation, there was a huge boost of the middle and working class. As the Industrial Revolution progressed there was further social division. Capitalists, for example, employed industrial workers, who were one component of the working classes (each class included a wide range of occupations of varying status and income; there was a large gap, for example, between skilled and unskilled labour), but beneath the industrial workers was a submerged "under class" sometimes referred to as the "sunken people," which lived in ]. The under class were more susceptible to exploitation and were therefore exploited. | |||

| File:Slum in Glasgow, 1871.jpg|Slum area in ] (1871) | |||

| File:Llanfyllin Workhouse - geograph.org.uk - 3098623.jpg|Buildings originally built as ] ], a state-funded home for the destitute which operated from 1838 to 1930.<ref>{{cite web|title=Llanfyllin, Montgomeryshire|url=http://www.workhouses.org.uk/Llanfyllin/|access-date=30 May 2023|archive-date=7 May 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230507044551/https://www.workhouses.org.uk/Llanfyllin/|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=Llanfyllin and district – The Union Workhouse – A Victorian prison for the poor|url=http://history.powys.org.uk/school1/llanfyllin/workmenu.shtml|publisher=Victorian Powys|access-date=30 May 2023|archive-date=25 April 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230425161039/http://history.powys.org.uk/school1/llanfyllin/workmenu.shtml|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| File:-Vignetted portrait, woman holding a baby- MET DP113912.jpg|Photograph of a mother and baby by ] ({{Circa|1850s or 60s}}) | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| ==Knowledge== | |||

| The government consisted of a ] headed by Queen Victoria. Only the royalty could rule. Other politicians came from the aristocracy. The system was criticised by many as being in favour of the upper classes, and during the late 18th century, philosophers and writers began to question the social status of the nobility. | |||

| ===Science=== | |||

| {{Main|Mathematics, science, technology and engineering of the Victorian era}} | |||

| ] delivering a ] ({{Circa|1855}})]] | |||

| The Industrial Revolution incentivised people to think more scientifically and to become more educated and informed in order to solve novel problems. As a result, cognitive abilities were pushed to their genetic limits, making people more intelligent and innovative than their predecessors.<ref name=":21">{{Cite journal |last=Dutton |first=Edward |last2=van der Linden |first2=Dimitri |last3=Lynn |first3=Richard |date=November–December 2016 |title=The negative Flynn Effect: A systematic literature review |url=https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2016.10.002 |journal=Intelligence |volume=59 |pages=163–9}}</ref><ref name=":92">{{Cite web |last=Gambino |first=Megan |date=December 3, 2012 |title=Are You Smarter Than Your Grandfather? Probably Not. |url=https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/are-you-smarter-than-your-grandfather-probably-not-150402883/ |access-date=October 22, 2020 |website=Smithsonian Magazine}}</ref> The Victorians were impressed by science and progress and felt that they could improve society in the same way as they were improving technology. Britain was the leading world centre for advanced engineering and technology. Its engineering firms were in worldwide demand for designing and constructing railways.<ref>Lionel Thomas Caswell Rolt, ''Victorian engineering'' (Penguin, 1974).</ref><ref>Herbert L. Sussman, ''Victorian technology: invention, innovation, and the rise of the machine'' (ABC-CLIO, 2009)</ref> | |||

| ==Events== | |||

| ;1842 : A law is passed to ban women and children working in mines. | |||

| ;1848 : 2,000 people a week die in a cholera epidemic. | |||

| ;1851 : The Great Exhibition (the first World's Fair) is held in The Crystal Palace, with great success and international attention. | |||

| ;1859 : ] publishes "]", which leads to great religious doubt and insecurity. | |||

| ;1861 : ] dies; Queen Victoria refuses to go out in public for many years, and when she does she wears a widow's ] instead of the crown. | |||

| ;1888 : The ] known as ] murders and mutilates five (and possibly more) ] on the streets of ], leading to world-wide press coverage and hysteria. Newspapers use the deaths to bring greater focus on the plight of the unemployed and to attack police and political leaders. The killer is never caught, and the affair contributes to Sir Charles Warren's resignation. | |||

| ;1891 : Education becomes free for every child. | |||

| The professionalisation of scientific study began in parts of Europe following the ]. ] coined the term 'scientist' in 1833 to refer to those who studied what was generally then known as natural philosophy, but it took a while to catch on. Having been previously dominated by amateurs with a separate income, the ] admitted only professionals from 1847 onwards.<ref name="Yeo-2011" /> The British biologist ] indicated in 1852 that it remained difficult to earn a living as a scientist alone.<ref name="Lewis-200732" /> Scientific knowledge and debates such as that about ]'s '']'' (1859), which sought to explain biological evolution by natural selection, gained a high profile in the public consciousness. Simplified (and at times inaccurate) ] was increasingly distributed through a variety of publications which caused tension with the professionals.<ref name="Yeo-2011">{{Cite book |last=Yeo |first=Richard R. |title=Victorian Britain An Encyclopedia |publisher=Routledge |year=2011 |isbn=9780415669726 |editor-last=Mitchell |editor-first=Sally |pages=694–696 |chapter=Science}}</ref> There were significant advances in various fields of research, including ],<ref name="Katz-2009a">{{Cite book |last=Katz |first=Victor |title=A History of Mathematics: An Introduction |publisher=Addison-Wesley |year=2009 |isbn=978-0-321-38700-4 |pages=824–830 |chapter=Chapter 23: Probability and Statistics in the Nineteenth Century}}</ref> ],<ref>{{Cite book |last=Kline |first=Morris |title=Mathematical Thought from Ancient to Modern Times |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=1972 |isbn=0-19-506136-5 |location=United States of America |pages=696–7 |chapter=28.7: Systems of Partial Differential Equations}}</ref> ],<ref name="Lewis-2007-1">{{Cite book |last=Lewis |first=Christoper |title=Heat and Thermodynamics: A Historical Perspective |publisher=Greenwood Press |year=2007 |isbn=978-0-313-33332-3 |location=United States of America |chapter=Chapter 7: Black Bodies, Free Energy, and Absolute Zero}}</ref> ],<ref name="Lewis-200732" /> ],<ref name="Baigrie-2007a">{{Cite book |last=Baigrie |first=Brian |title=Electricity and Magnetism: A Historical Perspective |publisher=Greenwood Press |year=2007 |isbn=978-0-313-33358-3 |location=United States of America |chapter=Chapter 8: Forces and Fields}}</ref> and ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Katz |first=Victor |title=A History of Mathematics: An Introduction |publisher=Addison-Wesley |year=2009 |isbn=978-0-321-38700-4 |pages=738–9 |chapter=21.3: Symbolic Algebra}}</ref> | |||

| ] stands in the shadow of ] Abbey ] ]] | |||

| == |

===Industry=== | ||

| ]Known as the 'workshop of the world', Britain was uniquely advanced in technology in the mid-19th century.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Buchanan |first=R. A. |title=Victorian Britain An Encyclopedia |publisher=Routledge |year=2011 |isbn=9780415669726 |editor-last=Mitchell |editor-first=Sally |pages=784–787 |chapter=Technology and invention}}</ref> Engineering, having developed into a profession in the 18th century, gained new profile and prestige in this period.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Buchanan |first=R. A. |title=Victorian Britain An Encyclopedia |publisher=Routledge |year=2011 |isbn=9780415669726 |editor-last=Mitchell |editor-first=Sally |pages=265–267 |chapter=Engineering}}</ref> The Victorian era saw methods of communication and transportation develop significantly. In 1837, ] and ] invented the first ]. This system, which used electrical currents to transmit coded messages, quickly spread across Britain, appearing in every town and post office. A worldwide network developed towards the end of the century. In 1876, ] patented the ]. A little over a decade later, 26,000 telephones were in service in Britain. Multiple switchboards were installed in every major town and city.<ref name="Atterbury-2011" /> ] developed early radio broadcasting at the end of the period.<ref name="Baigrie-2007b">{{Cite book |last=Baigrie |first=Brian |title=Electricity and Magnetism: A Historical Perspective |publisher=Greenwood Press |year=2007 |isbn=978-0-313-33358-3 |location=United States of America |chapter=Chapter 10: Electromagnetic Waves}}</ref> The railways were important economically in the Victorian era, allowing goods, raw materials, and people to be moved around, stimulating trade and industry. They were also a major employer and industry in their own right.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Ranlett |first=John |title=Victorian Britain An Encyclopedia |publisher=Routledge |year=2011 |isbn=9780415669726 |editor-last=Mitchell |editor-first=Sally |pages=663–665 |chapter=Railways}}</ref> | |||

| Popular forms of entertainment vary by socio-economic class. Victorian England, like the periods before it, was interested in theatre and the arts. Music, drama, and opera were widely attended. There were, however, other forms of entertainment. Gambling at cards in establishments popularly called casinos was wildly popular during the period—so much so that evangelical and reform movements specifically targeted such establishments in their efforts to stop gambling, drinking, and prostitution. | |||

| == Moral standards == | |||

| ] and 'The ]' became popular in the Victorian era typically associated with the British brass band. The band stand is a simple construction which not only creates an ornamental focal point, it also serves acoustic requirements whilst providing shelter from the changeable British weather. It was common to hear the sound of a brass band whilst strolling through parklands. At this time musical recording was still very much a novelty. | |||

| {{further|Victorian morality|Women in the Victorian era}} | |||

| ] | |||

| Another form of entertainment involved 'spectacles' where paranormal events, such as ], communication with the dead (by way of ] or ]), ] conjuring and the like, were carried out to the delight of crowds and participants. Such activities were very popular during this time compared to others in recent Western history. | |||

| Expected standards of personal conduct changed in around the first half of the 19th century, with good manners and self-restraint becoming much more common.<ref name="Perkin-1969">{{Cite book |last=Perkin |first=Harold |title=The Origins of Modern English Society |publisher=Routledge & Kegan Paul |year=1969 |isbn=9780710045676 |pages=280}}</ref> Historians have suggested various contributing factors, such as Britain's ] during the early 19th century, meaning that the distracting temptations of sinful behaviour had to be avoided in order to focus on the war effort, and the evangelical movement's push for moral improvement.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Briggs |first=Asa |title=The Age of Improvement: 1783–1867 |publisher=Longman |year=1959 |isbn=9780582482043 |pages=66–74, 286–87, 436}}</ref> There is evidence that the expected standards of moral behaviour were reflected in action as well as rhetoric across all classes of society.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Bradley |first=Ian C. |title=The Call to Seriousness: The Evangelical Impact on the Victorians |publisher=Lion Hudson Limited |year=2006 |isbn=9780224011624 |pages=106–109}}</ref><ref name="Probert-2012">{{Cite news |last=Probert |first=Rebecca |date=September 2012 |title=Living in Sin |work=BBC History Magazine}}</ref> For instance, an analysis suggested that less than 5% of working class couples cohabited before marriage.<ref name="Probert-2012" /> | |||

| ==Science, technology and engineering== | |||

| ] in ]]] | |||

| The impetus of the Industrial Revolution had already occurred, but it was during this period that the full effects of industrialization made themselves felt, leading to the mass society of the 20th century. The revolution led to the rise of railways across the country and great leaps forward in engineering, most famously by ]. | |||

| Another great engineering feat in the Victorian Era was the sewage system in London. It was designed by ] in 1858. He proposed to build 82 miles of sewerage linked with over 1,000 miles of street sewers. Many problems were found but the sewers were completed. After this, Bazalgette designed the ] which housed sewers, water pipes and the ]. | |||

| Historian ] argued that the change in moral standards led by the middle of the 19th century to 'diminished cruelty to animals, criminals, lunatics, and children (in that order)'.<ref name="Perkin-1969" /> Legal restrictions were placed on cruelty to animals.<ref>{{cite web |title=London Police Act 1839, Great Britain Parliament. Section XXXI, XXXIV, XXXV, XLII |url=http://www.animalrightshistory.org/animal-rights-law/victorian-legislation/1839-uk-act-london-police.htm |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110424093224/http://www.animalrightshistory.org/animal-rights-law/victorian-legislation/1839-uk-act-london-police.htm |archive-date=24 April 2011 |access-date=23 January 2011 |df=dmy-all}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=McMullan |first=M. B. |date=1998-05-01 |title=The Day the Dogs Died in London |url=https://doi.org/10.1179/ldn.1998.23.1.32 |journal=The London Journal |volume=23 |issue=1 |pages=32–40 |doi=10.1179/ldn.1998.23.1.32 |issn=0305-8034 |access-date=31 March 2023 |archive-date=4 June 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210604043828/https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1179/ldn.1998.23.1.32 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="Rep">{{citation |editor-last=Rothfels |editor-first=Nigel |title=Representing Animals |page=12 |year=2002 |publisher=Indiana University Press |isbn=978-0-253-34154-9}}. Chapter: 'A Left-handed Blow: Writing the History of Animals' by Erica Fudge</ref> Restrictions were placed on the working hours of child labourers in the 1830s and 1840s.<ref>{{Cite book |chapter=Cooper, Anthony Ashley, seventh Earl of Shaftesbury (1801–1885) |chapter-url=https://www.oxforddnb.com/display/10.1093/odnb/9780192683120.001.0001/odnb-9780192683120-e-6210 |title=Oxford Dictionary of National Biography |year=2018 |language=en |doi=10.1093/odnb/9780192683120.013.6210 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=Kelly |first=David |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=wMhwAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA548 |title=Business Law |publisher=Routledge |year=2014 |isbn=9781317935124 |page=548 |display-authors=etal}}</ref> Further interventions took place throughout the century to increase the level of child protection.<ref>{{cite book |author1=Litzenberger |first=C. J. |title=The Human Tradition in Modern Britain |author2=Eileen Groth Lyon |publisher=Rowman & Littlefield |year=2006 |isbn=978-0-7425-3735-4 |pages=142–143}}</ref> Use of the ] also decreased.<ref name="Perkin-1969" /> Crime rates fell significantly in the second half of the 19th century. Sociologist ] linked this change to attempts to morally educate the population, especially at ]s.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Davies |first=Christie |title=The Loss of Virtue: Moral Confusion and Social Disorder in Britain and America |year=1992 |isbn=978-0907631507 |editor-last=Anderson |editor-first=Digby |pages=5, 10 |chapter=Moralization and Demoralization: A Moral Explanation for Changes in Crime|publisher=Social Affairs Unit }}</ref> | |||

| During the Victorian era, science grew into the discipline it is today. In addition to the increasing professionalism of university science, many Victorian gentlemen devoted their time to the study of natural history. | |||

| ===Sexual behavior=== | |||

| Photography was realized in 1839 by ] in France and ] in England. By 1900, hand-held cameras were available. | |||

| Contrary to popular belief, Victorian society understood that both men and women enjoyed ].<ref name="draznin2001">{{cite book |author=Draznin, Yaffa Claire |title=Victorian London's Middle-Class Housewife: What She Did All Day (#179) |publisher=Greenwood Press |year=2001 |isbn=978-0-313-31399-8 |series=Contributions in Women's Studies |location=Westport, Connecticut |pages=95–96}}</ref> Chastity was expected of women, whilst attitudes to male sexual behaviour were more relaxed.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Goodman |first=Ruth |title=How to be a Victorian |publisher=] |year=2013 |isbn=978-0-241-95834-6 |chapter=Chapter 15: Behind the bedroom door}}</ref> The development of police forces led to a rise in prosecutions for illegal ] in the middle of the 19th century.<ref>Sean Brady, ''Masculinity and Male Homosexuality in Britain, 1861–1913'' (2005).</ref> Male sexuality became a favourite subject of medical researchers' study.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Crozier |first=I. |date=2007-08-05 |title=Nineteenth-Century British Psychiatric Writing about Homosexuality before Havelock Ellis: The Missing Story |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jhmas/jrm046 |journal=Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences |volume=63 |issue=1 |pages=65–102 |doi=10.1093/jhmas/jrm046 |pmid=18184695 |issn=0022-5045}}</ref> For the first time, all male homosexual acts were outlawed.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Smith |first=F. B. |date=1976 |title=Labouchere's amendment to the Criminal Law Amendment bill |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10314617608595545 |journal=Historical Studies |volume=17 |issue=67 |pages=165–173 |doi=10.1080/10314617608595545 |issn=0018-2559}}</ref> Concern about sexual exploitation of adolescent girls increased during the period, especially following the ], which contributed to the increasing of the age of consent ].<ref name="Clark-2011">{{Cite book |last=Clark |first=Anna |title=Victorian Britain An Encyclopedia |publisher=Routledge |year=2011 |isbn=9780415669726 |editor-last=Mitchell |editor-first=Sally |pages=642–645 |chapter=Prostitution}}</ref> | |||

| At a time when job options for women were limited and generally low-paying, some women, particularly those without familial support, took to prostitution to support themselves. Attitudes in public life and among the general population to prostitution varied. Evidence about prostitutes' situation also varies. One contemporary study argues that the trade was a short-term stepping stone to a different lifestyle for many women, while another, more recent study argues they were subject to physical abuse, financial exploitation, state persecution, and difficult working conditions. Due to worries about ], especially among soldiers, women suspected of prostitution were for a period between the 1860s and 1880s subject to spot compulsory examinations for ], and detainment if they were found to be infected. This caused a great deal of resentment among women in general due to the principle underlying the checks, that women had to be controlled in order to be safe for sexual use by men, and the checks were opposed by some of the earliest feminist campaigning.<ref name="Clark-2011" /> | |||

| Although initially developed in the early years of the 19th century, ] became widespread during the Victorian era in industry, homes, public buildings and the streets. The invention of the ] gas ] in the 1890s greatly improved light output and ensured its survival as late as the 1960s. Hundreds of gas works were constructed in cities and towns across the country. In 1882, incandescent ]s were introduced to London streets, although it took many years before they were installed everywhere. | |||

| ==Prostitution== | |||

| Beginning in the late 1840s, major news organisations, clergymen and single women became increasingly interested in ], which came to be known as "The Great Social Evil." Although estimates of the number of prostitutes in London by the 1850s vary widely (in his landmark study, ''Prostitution'', ] reported that the police estimated there were 8,600 in 1857 London alone), it is enough to say that the number of women working the streets became increasingly difficult to ignore. | |||

| When the 1851 census publicly revealed a 4% demographic imbalance in favour of women (i.e. 4% more women than men), the problem of prostitution began to shift from a moral/religious cause to a ] one. The 1851 census showed that the population of Great Britain was roughly 18 million; this meant that roughly 750,000 women would remain unmarried simply because there were not enough men. These women came to be referred to as "superfluous women" or "redundant women," and many essays were published discussing what, precisely, ought to be done with them. | |||

| While the Magdalen Hospital had been "reforming" prostitutes since the mid-18th century, the years between 1848 and 1870 saw a veritable explosion in the number of institutions working to "reclaim" these "fallen women" from the streets and retrain them for entry into respectable society—usually for work as domestic servants. The theme of prostitution and the "fallen woman" (an umbrella term used to describe any women who had ] out of ]) became a staple feature of mid-Victorian literature and politics. In the writings of ], ] and others, prostitution began to be seen as a ], rather than just a fact of urban life. | |||

| When ] passed the first of the ] in 1864 (which allowed the local constabulary to force any woman suspected of ] to submit to its inspection), ]'s crusade to repeal the CD Acts yoked the anti-prostitution cause with the emergent ]. Butler attacked the long-established ] of sexual morality. | |||

| Prostitutes were often presented as victims in ] such ]'s poem ''The Bridge of Sighs'', ]'s novel '']'' and ]' novel '']''. The emphasis on the purity of women found in such works as ]'s '']'' led to the portrayal of the prostitute and fallen woman as soiled, corrupted, and in need of cleansing. | |||

| This emphasis on female purity was allied to the stress on the ] role of women, who helped to create a space free from the pollution and corruption of the city. In this respect the prostitute came to have symbolic significance as the embodiment of the violation of that divide. The double standard remained in force. ] legislation introduced in 1857 allowed for a man to divorce his wife for ], but a woman could only divorce if adultery was accompanied by cruelty. The anonymity of the city led to a large increase in prostitution and unsanctioned sexual relationships. Dickens and other writers associated prostitution with the mechanisation and industrialisation of modern life, portraying prostitutes as human commodities consumed and thrown away like refuse when they were used up. Moral reform movements attempted to close down ]s, something that has sometimes been argued to have been a factor in the concentration of street-prostitution in ](East End) by the 1880s. | |||

| By the time the CD Acts were repealed in 1886, Victorian England had been completely transformed. This era, which at its outset looked no different from the century before it, would end resembling much more the era that would follow. | |||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||