| Revision as of 22:33, 30 November 2003 edit1984 (talk | contribs)303 edits +es link← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 03:25, 6 January 2025 edit undoOAbot (talk | contribs)Bots441,761 editsm Open access bot: doi updated in citation with #oabot. | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|4th- and 5th-century priest and theologian}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{about|the priest and Bible translator||Jerome (disambiguation)|and|Saint Jerome (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=October 2022}} | |||

| {{Infobox saint | |||

| | honorific_prefix = ] | |||

| | name =Jerome | |||

| | titles =Doctor of the Church | |||

| | birth_date ={{circa|342–347}} | |||

| | death_date =30 September 420 (aged approximately 73–78)<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.britannica.com/biography/Saint-Jerome |title=St. Jerome (Christian scholar) |publisher=Britannica Encyclopedia |date=2 February 2017 |access-date=23 March 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170324093227/https://www.britannica.com/biography/Saint-Jerome |archive-date=24 March 2017 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

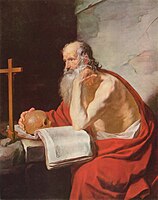

| | image =MatthiasStom-SaintJerome-Nantes.jpg | |||

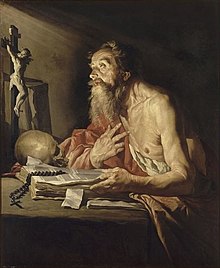

| | caption ='']'' by ], 1635 | |||

| | birth_place =] (possibly Strido Dalmatiae, on the border of ] and ]){{sfn | Kurian | Smith | 2010 | p=389|ps=: Jerome ("Hieronymus" in Latin), was born into a Christian family in Stridon, modern-day Strigova in northern Croatia}} | |||

| | death_place =], ] | |||

| | module = {{Infobox theologian | |||

| | embed=yes | |||

| | education = ] | |||

| | occupation = Translator, theologian | |||

| | notable_works = ]<br />'']''<br />'']'' | |||

| | era = ] | |||

| | language = ], ], ], ], ] | |||

| | tradition_movement = ] | |||

| | main_interests = ], ], ], ] | |||

| | notable_ideas = ] | |||

| }} | |||

| | feast_day =30 September (])<br />15 June (]) | |||

| | venerated_in =]<br />]<br />]<br />]<br />] | |||

| | attributes =Lion, ], ], ], trumpet, ], books and ] | |||

| | patronage =]s; archivists; ]s; librarians; libraries; school children; students; translators; ]; Dalmatia, against ] | |||

| | major_shrine =], Rome, Italy | |||

| | suppressed_date= | |||

| |influences=], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ]|influenced=Virtually all of subsequent ], including ], ] and some ]}} | |||

| {{Catholic philosophy}} | |||

| '''Jerome''' ({{IPAc-en|dʒ|ə|ˈ|r|oʊ|m}}; {{langx|la|Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus}}; {{langx|grc|Εὐσέβιος Σωφρόνιος Ἱερώνυμος}}; {{circa|342–347}} – 30 September 420), also known as '''Jerome of Stridon''', was an early Christian ], ], ], ], and historian; he is commonly known as '''Saint Jerome'''. | |||

| '''Jerome''' (about ] - ], ]), (full name '''Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus''') is best known as the translator of the ] from ] and ] into ]. Jerome's edition, the ], is still the official biblical text of the ]. He is recognized by the Vatican as a ]. He was born at ], on the border between ] and ], in the second quarter of the fourth century, and died near ] Sept. 30, ]. | |||

| He is best known for his translation of the Bible into ] (the translation that became known as the ]) and his commentaries on the whole Bible. Jerome attempted to create a translation of the ] based on a Hebrew version, rather than the ], as ] had done. His list of writings is extensive. In addition to his biblical works, he wrote polemical and historical essays, always from a theologian's perspective.<ref>{{cite book |editor1-first=Philip |editor1-last=Schaff |editor1-link=Philip Schaff |others=Henry Wace |title=A Select Library of Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church |access-date=7 June 2010 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NQUNAAAAIAAJ |volume=VI |year=1893 |publisher=The Christian Literature Company |location=New York |series=2nd series |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140711191259/https://books.google.com/books?id=NQUNAAAAIAAJ |archive-date=11 July 2014 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Jerome is a name shared across the European languages in remarkably unintuitive forms: | |||

| Hieronymus (Latin) = Jerome (English, and with diacritical marks, French) = Girolamo (Italian) = Geronimo (Spanish) | |||

| Jerome was known for his teachings on ] life, especially those in cosmopolitan centers such as Rome. He often focused on women's lives and identified how a woman devoted to Jesus should live her life. This focus stemmed from his close patron relationships with several prominent female ] who were members of affluent ].{{sfn|Williams|2006|p=}} | |||

| ==Life== | |||

| Jerome was born to Christian parents, but was not baptized until about ], when he had gone to ] with his friend Bonosus to pursue his ]al and ] studies. Here he studied under ], the foremost reacher of his time. He also learned ], but yet had no thought of studying the Greek Fathers, or any Christian writings. After several years in Rome, he travelled with Bonosus to Gaul and settled in ] "on the semi-barbarous banks of the Rhine" where he seems to have first taken up theological studies, and where he copied, for his friend Rufinus, ]'s commentary on the Psalms and the treatise ''De synodis''. Next came a stay of at least several months, or possibly years, with ] at ] where he made many Christian friends. Some of these accompanied him when he set out about ] on a journey through Thrace and Asia Minor into northern Syria. At ], where he made the longest stay, two of his companions died and he himself was seriously ill more than once. During one of these illnesses (about the winter of ] - ]) he had a vision which determined him to lay aside his secular studies and devote himself to the things of God. In any case he seems to have abstained for a considerable time from the study of the classics and to have plunged deeply into that of the ], under the impulsion of ], then teaching in Antioch and not yet suspected of heresy. Seized with the desire for a life of ] penance, he went for a time to the desert of Chalcis, to the southwest of Antioch, known as the Syrian Thebaid, from the number of hermits inhabiting it. During this period, however, he seems to have found time for study and writing. He made his first attempt to learn ] under the guidance of a converted Jew; and at this time he seems to have been in relation with the Jewish Christians in Antioch, and perhaps as early as this to have interested himself in the ], asserted by them to be the source of the canonical ]. | |||

| In addition, his works are a crucial source of information on the pronunciation of the ] in ].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Kantor |first1=Benjamin Paul |title=The Linguistic Classification of the Reading Traditions of Biblical Hebrew: A Phyla-and-Waves Model |series=Semitic Languages and Cultures |date=30 August 2023 |volume=19 |publisher=Open Book Publishers |isbn=978-1-78374-953-9 |page=20 |doi=10.11647/obp.0210 |doi-access=free |language=English}}</ref> | |||

| Returning to Antioch, in ] or ], he was ordained by Bishop ], apparently with some unwillingness and on condition that he still continue his ] life. Soon afterward he went to Constantinople to pursue his study of Scripture under the instruction of ]. There he seems to have spent two years; the next three (382 - 385) he was in Rome again, in close intercourse with ] and the leading Roman Christians. Invited thither originally to the synod of ] held for the purpose of ending the schism of Antioch, he made himself indispensable to the pope, and took a prominent place in his councils. Among other duties he undertook the revision of the text of the ] on the basis of the Greek New Testament and the ], in order to put an end to the marked divergences in the current western texts. This commission determined the course of his scholarly activity for many years, and is his most important achievement. He undoubtedly exercised an important influence during these three years, to which, outside of his unusual learning, his zeal for ] strictness and the realization of the monastic ideal contributed not a little. He was surrounded by a circle of well-born and well-educated women, including some from the noblest patrician families, such as the widows Marcella and Paula, with their daughters Blaesilla and Eustochium. The resulting inclination of these women for the monastic life, and his unsparing criticism of the life of the secular clergy, brought a growing hostility against him amongst the clergy and their supporters. Soon after the death of his patron Damasus (], ]), and having lost his necessary protection, Jerome left his position at Rome. | |||

| Due to his work, Jerome is recognized as a ] and ] by the ], and as a saint in the ],{{efn|name=EOC}} the ], and the ]. His ] is 30 September (]). | |||

| In August 385 he returned to Antioch, accompanied by his brother Paulinianus and several friends and followed a little later by Paula and Eustochium, who had resolved to leave their patrician surroundings and to end their days in the Holy Land. In the winter of 385 Jerome accompanied them and acted as their spiritual adviser. The pilgrims, joined by Bishop Paulinus of Antioch, visited Jerusalem, Bethlehem, and the holy places of Galilee, and then went to ], the home of the great heroes of the ascetic life. In ] Jerome listened to the blind catechist ] expounding the prophet ] and telling his reminiscences of ], who had died thirty years before; he spent some time in ], admiring the disciplined community life of the numerous inhabitants of that "city of the Lord," but detecting even there "concealed serpents," i.e., the influence of the theology of ]. Late in the summer of ] he was back in Palestine, and settled down for the remainder of his life in a hermit's cell near Bethlehem, surrounded by a few friends, both men and women (including Paula and Eustochium), to whom he acted as priestly guide and teacher. | |||

| == Early life == | |||

| Amply provided by Paula with the means of livelihood and of increasing his collection of books, he led a life of incessant activity in literary production. To these last thirty-four years of his career belong the most important of his works -- his version of the Old Testament from the original text, the best of his scriptural commentaries, his catalogue of Christian authors, and the dialogue against the ], the literary perfection of which even a controversial opponent recognized. To this period also belong the majority of his passionate polemics, which distinguished him among the orthodox Fathers, including notably the treatises occasioned by the Origenistic controversy against Bishop ] and his early friend Rufinus. As a result of his writings against Pelagianism, a body of excited partisans broke into the monastic buildings, set them on fire, attacked the inmates and killed a deacon, which forced Jerome to seek safety in a neighboring fortress (]). The date of his death is given by the ''Chronicon'' of ]. His remains, originally buried at Bethlehem, are said to have been later translated to the church of Santa Maria Maggiore at Rome, though other places in the West claim some relics -- the cathedral at Nepi boasting the possession of his head, which, according to another tradition, is in the Escurial. | |||

| Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus was born at ] around 342–347 AD.{{sfn|Williams|2006|p=}} He was of ] ancestry.{{sfn|Pevarello|2013|p=1}} He was not ] until about 360–369 in Rome, where he had gone with his friend ] to pursue ]al and philosophical studies. (This Bonosus may or may not have been the same Bonosus whom Jerome identifies as his friend who went to live as a hermit on an island in the Adriatic.) Jerome studied under the ] ]. There he learned ] and at least some ],{{sfn|Walsh|1992|p=307}} though he probably did not yet acquire the familiarity with Greek literature that he later claimed to have acquired as a schoolboy.{{sfn|Kelly|1975|pp=13–14}} | |||

| As a student, Jerome engaged in the superficial escapades and sexual experimentation of students in Rome; he indulged himself quite casually but he suffered terrible bouts of guilt afterwards.{{sfn|Payne|1951|pp=90–92}} To appease his ], on Sundays he visited the ] of the ]s and the ] in the catacombs. This experience reminded him of the terrors of ]: | |||

| ==Writings== | |||

| <blockquote>Often I would find myself entering those crypts, deep dug in the earth, with their walls on either side lined with the bodies of the dead, where everything was so dark that almost it seemed as though the Psalmist's words were fulfilled, Let them go down quick into Hell.<ref>{{bibleverse|Psalm |55:15}}</ref> Here and there the light, not entering in through windows, but filtering down from above through shafts, relieved the horror of the darkness. But again, as soon as you found yourself cautiously moving forward, the black night closed around and there came to my mind the line of Virgil, "Horror ubique animos, simul ipsa silentia terrent".<ref>{{Citation |last=Jerome |title=Commentarius in Ezzechielem |at=c. 40, v. 5}}</ref>{{efn|name=PL}}</blockquote> | |||

| ===Translations=== | |||

| '''Jerome''' was a noted scholar of Latin at a time when that statement implied a fluency in Greek. He knew some Hebrew when he started his translation project, but moved to Bethlehem to perfect his grasp of the language and to strengthen his grip on Jewish scripture commentary. A wealthy Roman aristocrat, Paula, founded a monastery for him in Bethlehem - rather like a research institute, today - and he completed his translation there. He began in 382 by correcting the existing Latin language version of the New Testament, commonly referred to as the ''Itala'' or ''Vetus Latina'' (the "Italian" or "]" version). By ] he turned to the ] in Hebrew, having previously translated portions from the Septuagint Greek version. He completed this work by ]. | |||

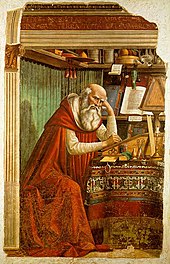

| ]'' (1480), by ]]] | |||

| For the next 15 years, until he died, he produced a number of commentaries on scripture, often explaining his translation choices. His knowledge of Hebrew, primarily required for this branch of his work, gives also to his exegetical treatises (especially to those written after 386) a value greater than that of most patristic commentaries, although he is as a rule too much hampered by Jewish tradition, and indulges too often in allegorical and mystical subtleties after the manner of ] and the Alexandrian school. But he deserves credit for the distinctness with which he emphasizes the difference between the Old Testament Apocrypha and the ''Hebraica veritas'' of the canonical books (cf. his introductions to the ], see ''Prologus Galeatus'', to the Solomonic writings, to the ], and to ]. His commentaries fall into three groups: | |||

| The quotation from ] reads, in translation, "On all sides round, horror spread wide; the very silence breathed a terror on my soul".<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131111105830/http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0054%3Abook%3D2%3Acard%3D752 |date=11 November 2013 }} (retrieved 23 August 2013)</ref> | |||

| *His translations or recastings of Greek predecessors, including fourteen homilies on ] and the same number on ] by Origen (translated c.380 in Constantinople); two homilies of Origen on the Song of Solomon (in Rome, c.383); and thirty-nine on ] (c.389, in Bethlehem). The nine homilies of Origen on ] included among his works were not done by him. Here should be mentioned, as an important contribution to the topography of Palestine, his book ''De situ et nominibus locorum Hebraeorum,'' a translation with additions and some regrettable omissions of the ''Onomasticon'' of Eusebius. To the same period (c. 390) belongs the ''Liber interpretationis nominum Hebraicorum'', based on a work supposed to go back to Philo and expanded by Origen. | |||

| *Original commentaries on the Old Testament. To the period before his settlement at Bethlehem and the following five years belong a series of short Old Testament studies: ''De seraphim'', ''De voce Osanna'', ''De tribus quaestionibus veteris legis'' (usually included among the letters as 18, 20, and 36); ''Quaestiones hebraicae in Genesin''; ''Commentarius in Ecclesiasten''; ''Tractatus septem in Psalmos 10 - 16'' (lost); ''Explanationes in Michaeam'', ''Sophoniam'', ''Nahum, ''Habacuc'', ''Aggaeum.'' About 395 he composed a series of longer commentaries, though in rather a desultory fashion: first on the remaining seven minor prophets, then on Isaiah (c.395 - c.400), on ] (c. 407), on Ezekiel (between 410 and 415), and on Jeremiah (after 415, left unfinished). | |||

| *New Testament commentaries. These include only ], ], ], and ] (hastily composed 387 - 388); Matthew (dictated in a fortnight, 398); ], selected passages in ], the prologue of ], and ]. Treating the last-named book in his cursory fashion, he made use of an excerpt from the commentary of the North-African ], which is preserved as a sort of argument at the beginning of the more extended work of the Spanish presbyter ]. But before this he had already devoted to the Book of Revelation another treatment, a rather arbitrary recasting of the commentary of ] (d. 303), with whose ] views he was not in accord, substituting for the chiliastic conclusion a spiritualizing exposition of his own, supplying an introduction, and making certain changes in the text. | |||

| === Conversion to Christianity === | |||

| ===Historical Writings=== | |||

| ]'' ]] | |||

| One of Jerome's earliest attempts in the department of history was his ''Temporum liber,'' composed c.] in ]; this is a recasting in Latin of the chronological tables which compose the second part of the ''Chronicon'' of ], with a supplement covering the period from ] to ]. In spite of numerous errors taken over from Eusebius, and some of his own, Jerome produced a valuable work, if only for the impulse which it gave to such later chroniclers as Prosper, ], and ] to continue his annals. Three other works of a hagiological nature are the ''Vita Pauli monachi,'' written during his first sojourn at ] (c.]), the legendary material of which is derived from Egyptian monastic tradition; the ''Vita Malchi monachi captivi'' (c.]), probably based on an earlier work, although it purports to be derived from the oral communications of the aged ] Malchus originally made to him in the desert of Chalcis; and the ''Vita Hilarionis,'' of the same date, containing more trustworthy historical matter than the other two, and based partly on the biography of ] and partly on oral tradition. The so-called ''Martyrologium sancti Hieronymi'' is spurious; it was apparently composed by a western monk toward the end of the sixth or beginning of the seventh century, with reference to an expression of Jerome's in the opening chapter of the ''Vita Malchi,'' where he speaks of intending to write a history of the saints and martyrs from the apostolic times. But the most important of Jerome's historical works is the book ''De viris illustribus,'' written at ] in ], the title and arrangement of which are borrowed from Suetonius. It contains short biographical and literary notes on 135 Christian authors, from ] down to Jerome himself. For the first seventy-eight authors Eusebius (''Historia ecclesiastica'') is the main source; in the second section, beginning with ] and ], he includes a good deal of independent information, especially as to western writers. | |||

| Although at first afraid of Christianity, he eventually ].{{sfn|Payne|1951|p=91}} | |||

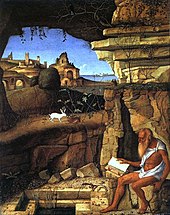

| ]'', by ] (1505)]] | |||

| ===Letters=== | |||

| Seized with a desire for a life of ascetic ], Jerome went for a time to the desert of ], to the southeast of ], known as the "Syrian ]" from the number of ] (hermits) inhabiting it. During this period, he seems to have found time for studying and writing. He made his first attempt to learn ] under the guidance of a converted ]; and he seems to have been in correspondence with ] in Antioch. Around this time he had copied for himself a Hebrew Gospel, of which fragments are preserved in his notes. It is known today as the ], which the ] considered to be the true ].{{sfn|Rebenich|2002|p=211|ps=: Further, he began to study Hebrew: 'I betook myself to a brother who before his conversion had been a Hebrew and...'}} Jerome translated parts of this Hebrew Gospel into Greek.<ref>{{Citation |first=Ray |last=Pritz |title=Nazarene Jewish Christianity: from the end of the New Testament |year=1988 |page=50 |quote=In his accounts of his desert sojourn, Jerome never mentions leaving Chalcis, and there is no pressing reason to think...}}</ref> | |||

| Jerome's letters, both by the great variety of their subjects and by their qualities of style, form the most interesting portion of his literary remains. Whether he is discussing problems of scholarship, or reasoning on cases of conscience, comforting the afflicted, or saying pleasant things to his friends, scourging the vices and corruptions of the time, exhorting to the ascetic life and renunciation of the world, or breaking a lance with his theological | |||

| opponents, he gives a vivid picture not only of his own mind, but of the age and its peculiar characteristics. | |||

| === Ministry in Rome === | |||

| The letters most frequently reprinted or referred to are of a hortatory nature, such as ''Ep. 14'', ''Ad Heliodorum de laude vitae solitariae''; ''Ep. 22'', ''Ad Eustochium de custodia virginitatis''; ''Ep. 52'', ''Ad Nepotianum de vita clericorum et monachorum,'' a sort of epitome of pastoral theology from the ascetic standpoint; ''Ep. 53'', ''Ad Paulinum de studio scripturarum''; ''Ep. 57'', to the same, ''De institutione monachi''; ''Ep. 70'', ''Ad Magnum de scriptoribus ecclesiasticis;'' and ''Ep. 107'', ''Ad Laetam de institutione filiae.'' | |||

| As protégé of ], Jerome was given duties in Rome, and he undertook a revision of the '']'' Gospels based on ] manuscripts. He also updated the Psalter containing the Book of Psalms then in use in Rome, based on the ]. | |||

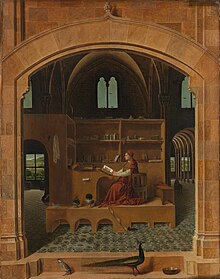

| ] |url=http://art.thewalters.org/detail/27087 |title=Saint Jerome in His Study |access-date=18 September 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130516145200/http://art.thewalters.org/detail/27087 |archive-date=16 May 2013 |url-status=dead }}</ref> The Walters Art Museum.]] | |||

| ===Theological Writings=== | |||

| Throughout his epistles he shows himself to be surrounded by women and united with close ties; it is estimated that 40% of his epistles were addressed to someone of the female sex and,<ref>D. Ruiz Bueno. (1962). Cartas de S. Jerónimo, 2 vols. Madrid.</ref> at the time, he was criticized for it.<ref>Epistle 45,2-3; 54,2; 65,1; 127,5.</ref> | |||

| Practically all of Jerome's productions in the field of dogma have a more or less violently polemical character, and are directed against assailants of the orthodox doctrines. Even the translation of the treatise of ] on the Holy Spirit into Latin (begun in Rome ], completed at Bethlehem) shows an apologetic tendency against the ] and ]. The same is true of his version of Origen's ''De principiis'' (c.]), intended to supersede the inaccurate translation by Rufinus. The more strictly polemical writings cover every period of his life. During the sojourns at Antioch and Constantinople he was mainly occupied with the Arian controversy, and especially with the schisms centering around Meletius and ]. Two letters to Pope Damasus (15 and 16) complain of the conduct of both parties at Antioch, the Meletians and Paulinians, who had tried to draw him into their controversy over the application of the terms ''ousia'' and ''hypostasis'' to the trinity. At the same time or a little later (]) he composed his ''Liber Contra Luciferianos'', in which he cleverly uses the dialogue form to combat the tenets of that faction, particularly their rejection of baptism by heretics. In Rome (c. ]) he wrote a passionate counterblast against the teaching of Helvidius, in defense of the doctrine of the perpetual virginity of Mary, and of the superiority of the single over the married state. An opponent of a somewhat similar nature was Jovinianus, with whom he came into conflict in ] (''Adversus Jovinianum,'' and the defense of this work addressed to his friend Pammachius, numbered 48 in the letters). Once more he defended the ordinary catholic practises of piety and his own ] ethics in ] against the Spanish presbyter | |||

| Vigilantius, who opposed the cultus of martyrs and relics, the vow of poverty, and clerical celibacy. Meanwhile the controversy with John of Jerusalem and Rufinus concerning the orthodoxy of Origen occurred. To this period belong some of his most passionate and most comprehensive polemical works: the ''Contra Joannem Hierosolymitanum'' (] or ]); the two closely-connected ''Apologiae contra Rufinum'' (402); and the "last word" written a few months later, the ''Liber tertius seu ultima responsio adversus scripta Rufini.'' The last of his polemical works is the skilfully-composed ''Dialogue contra Pelagianos '' (]). | |||

| Even in his time, Jerome noted ] accusation that the Christian communities were run by women and that the favor of the ladies decided who could accede to the dignity of the priesthood.<ref>Gigon, O. (1966). Die antike Kultur und das Christentum. pp. 120.</ref><ref>Deschner, Karlheinz (1986). ] pp. 164-170.</ref> | |||

| ==Theological Position== | |||

| Jerome undoubtedly ranks as the most learned of the western Fathers. In the ], he is recognized as the ] of ]s and ]s. | |||

| In Rome, Jerome was surrounded by a circle of well-born and well-educated women, including some from the noblest ] families. Among these women were such as the widows ], ], and ], and Paula's daughters ] and ]. The resulting inclination of these women towards the monastic life, away from the indulgent lasciviousness in Rome, and his unsparing criticism of the ] of Rome, brought a growing hostility against him among the Roman clergy and their supporters. Soon after the death of his patron Pope Damasus I on 10 December 384, Jerome was forced to leave his position at Rome after an inquiry was brought up by the Roman clergy into allegations that he had an improper relationship with the widow Paula. Still, his writings were highly regarded by women who were attempting to maintain vows of becoming ]s. His letters were widely read and distributed throughout the Christian empire and it is clear through his writing that he knew these virgin women were not his only audience.{{sfn|Williams|2006|p=}} | |||

| He surpasses the others especially in his knowledge of Hebrew, gained by hard study, and not unskilfully used. It is true that he was perfectly conscious of his advantages, and not entirely free from the temptation to despise or belittle his literary rivals, especially Ambrose. His own scholarship is by no means without its weak points. His acquaintance with Greek and Latin literature, both pagan and Christian, is great, but by no means without its gaps and its traces of superficial reading; and his knowledge of Hebrew offers innumerable points of attack to modern criticism. | |||

| Additionally, Jerome's condemnation of Blaesilla's hedonistic lifestyle in Rome led her to adopt ascetic practices, but these affected her health and worsened her physical weakness to the point that she died just four months after starting to follow his instructions; much of the Roman populace was outraged that Jerome, in their view, thus caused the premature death of such a lively young woman. Additionally, his insistence to Paula that Blaesilla should not be mourned and complaints that her grief was excessive were seen as heartless, which further polarized Roman opinion against him.{{sfn | Salisbury | Lefkowitz | 2001 | pp=32-33}} | |||

| As a general rule it is not so much by absolute knowledge that he shines as by an almost poetical elegance, an incisive wit, a singular skill in adapting recognized or proverbial phrases to his purpose, and a successful aiming at rhetorical effect. His weaknesses are most noticeable in dogmatic subjects. He was so little of a dogmatic theologian that he contributed only indirectly to the development of doctrine. The same may be said of his contribution to moral theology, in which he showed less an interest in abstract ethical speculation than a morbid ascetic zeal and passionate enthusiasm for the monastic ideal. | |||

| ]'', by ] {{c.|1445|lk=no}}–46, depicts Jerome's removal of a thorn from a lion's paw.]] | |||

| It was this attitude that made ] judge him so severely. In fact, Evangelical readers are generally little inclined to accept his writings as authoritative, especially in consideration of his lack of independence as a dogmatic teacher and his submission to orthodox tradition. He approaches his papal patron Damasus with the most utter submissiveness, making no attempt at an independent decision of his own. The Church founded upon the rock of Peter is to | |||

| decide whether he is to recognize, with the ], three ''hypostases'' in the divine ''ousia,'' or, with the ], one ''hypostasis'' with three ''prosopa'' or persons. "Decide, I pray thee, and I shall not fear to speak of three ''hypostases''." He may be called not only the forerunner of modern ultra-montanism, but even of the ] unreasoning obedience. The tendency to recognize a superior comes out scarcely less significantly in his correspondence with ] (cf. Jerome's letters numbered 56, 67, 102 - 105, 110 - 112, 115 - 116; and 28, 39, 40, 67 - 68, 71 - 75, 81 - 82 in Augustine's). | |||

| ==Scholarly works== | |||

| Yet in spite of the defects and weaknesses already mentioned, Jerome has retained a rank among the western Fathers. This would be his due, if for nothing else, on account of the incalculable influence exercised by his Latin version of the Bible upon the subsequent ecclesiastical and theological development. But that he won his way to the title of a saint and doctor of the catholic Church was possible only because he broke away entirely from the theological school in which he was brought up, that of the Origenists. In the artistic tradition of the Roman Catholic Church it has been usual to represent him, the patron of theological learning, as a cardinal, by the side of the Bishop Augustine, the Archbishop ], and the ]. Even when he is depicted as a half-clad anchorite, with cross, skull, and Bible for the only furniture of his cell, the red hat or some other indication of his rank is as a rule introduced somewhere in the picture. | |||

| ===Translation of the Bible (382–405)=== | |||

| ], 1607, at St John's Co-Cathedral, ]]] | |||

| Jerome was a scholar at a time when being a scholar implied a fluency in Greek. He knew some Hebrew when he started his ], but moved to ] to strengthen his grip on Jewish scripture commentary. A wealthy Roman aristocrat, Paula, funded Jerome's stay in a monastery in the nearby city of ], where he settled next to the ] – built half a century prior on orders of ] over what was reputed to be the site of the ] – and he completed his translation there. He began in 382 by correcting the existing Latin-language version of the New Testament, commonly referred to as the '']''. By 390 he turned to translating the ] from the original Hebrew, having previously translated portions from the ] which came from Alexandria. He believed that the mainstream ] had rejected the Septuagint as invalid Jewish scriptural texts because of what were ascertained as mistranslations along with its ] ] elements.{{efn|name=ndq}} He completed this work by 405. Prior to Jerome's Vulgate, all Latin translations of the ] were based on the Septuagint, not the Hebrew. Jerome's decision to use a Hebrew text instead of the previously translated Septuagint went against the advice of most other Christians, including ], who thought the Septuagint ]. Modern scholarship, however, has sometimes cast doubts on the actual quality of Jerome's Hebrew knowledge. Many modern scholars believe that the Greek ] is the main source for ] (i.e. "close to the Hebrews", "immediately following the Hebrews") translation of the Old Testament.<ref>Pierre Nautin, article "Hieronymus", in: ''Theologische Realenzyklopädie'', Vol. 15, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin & New York 1986, pp. 304–315, .</ref> However, detailed studies have shown that to a considerable degree Jerome was a competent Hebraist.<ref>Michael Graves, ''Jerome's Hebrew Philology: A Study Based on his Commentary on Jeremiah'', Brill, 2007: 196–198 (ISBN 978-90-47-42181-8): "In his discussion he gives clear evidence of having consulted the Hebrew himself, providing details about the Hebrew that could not have been learned from the Greek translations."</ref> | |||

| ''This article uses material from Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religion'' | |||

| === Biblical onomastica === | |||

| Jerome also produced two ]: | |||

| * ''Liber de Nominibus Hebraicis'', a list of names of people in the Bible and etymologies, based on a work attributed to ] and expanded by ] | |||

| * A translation and expansion of the ], listing and commenting on places mentioned in the Bible | |||

| === Commentaries (405–420) === | |||

| ] ]] | |||

| For the next 15 years, until he died, Jerome produced a number of commentaries on Scripture, often explaining his translation choices in using the original Hebrew rather than suspect translations. His ] commentaries align closely with Jewish tradition, and he indulges in ] and ] subtleties after the manner of ] and the ]. Unlike his contemporaries, he emphasizes the difference between the Hebrew Bible "Apocrypha" and the ''Hebraica veritas'' of the ]. In his ], he describes some portions of books in the Septuagint that were not found in the Hebrew as being non-] (he called them '']'');<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.thelatinlibrary.com/bible/prologi.shtml |title=The Bible |access-date=14 December 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160113204339/http://www.thelatinlibrary.com/bible/prologi.shtml |archive-date=13 January 2016 |url-status=live }}</ref> for ], he mentions by name in his ''Prologue to Jeremiah'' and notes that it is neither read nor held among the Hebrews, but does not explicitly call it apocryphal or "not in the canon".<ref>{{citation |url=http://www.bombaxo.com/blog/?p=233 |title=Jerome's Prologue to Jeremiah |first=Kevin P. |last=Edgecomb |access-date=14 December 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131231002043/http://www.bombaxo.com/blog/?p=233 |archive-date=31 December 2013 |url-status=live }}</ref> His '']''<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf206.vii.iii.iv.html |title=Jerome's Preface to Samuel and Kings |access-date=14 December 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151202094009/http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf206.vii.iii.iv.html |archive-date=2 December 2015 |url-status=live }}</ref> (commonly called the ''Helmeted Preface'') includes the following statement: | |||

| <blockquote>This preface to the Scriptures may serve as a "helmeted" introduction to all the books which we turn from Hebrew into Latin, so that we may be assured that what is not found in our list must be placed amongst the Apocryphal writings. ], therefore, which generally bears the name of Solomon, and the book of ], and ], and ], and the ] are not in the canon. The ] I have found to be Hebrew, ] is Greek, as can be proved from the very style.</blockquote> | |||

| ], 1639, ]]] | |||

| === Historical and hagiographic writings === | |||

| '''Jerome as a historian''' | |||

| Jerome's most famous work of historical writing was the '']'', a translation, reworking, and continuation of the '']'' of Eusebius. Written in Constantinople around 380 it became an influential text in Latin Christendom even though it is not without errors.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Burgess |first=R.W. |date=2002 |title=Jerome explained: an introduction to his Chronicle and a guide to its use |journal=The Ancient History Bulletin |volume=16 |pages=1-32}}</ref> In his other works he evoked historical events and used history as an example and source of argument. Even though Jerome engaged in historical writing, he did not consider himself bound by the rules of historians and his output in this domain has to be judged accordingly.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Fafinski |first=Mateusz |date=2025 |title=The ends of history? Jerome, Geruchia, and the Rhine crossings |url=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/emed.12752 |journal=Early Medieval Europe |language=en |volume=33 |issue=1 |pages=5 |doi=10.1111/emed.12752 |issn=1468-0254|doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| ==== Description of vitamin A deficiency ==== | |||

| The following passage, taken from Jerome's ''Life of St. Hilarion'' which was written {{Circa|392|lk=no}}, appears to be the earliest account of the ], symptoms and cure of severe ]:<ref name="Vitamin" /> | |||

| {{blockquote|From his thirty-first to his thirty-fifth year he had for food six ounces of ], and vegetables slightly cooked without oil. But finding that his eyes were growing dim, and that his whole body was shrivelled with an eruption and a sort of stony roughness (''impetigine et pumicea quad scabredine'') he added oil to his former food, and up to the sixty-third year of his life followed this temperate course, tasting neither fruit nor pulse, nor anything whatsoever besides.<ref name="Vitamin">{{cite journal |author=Taylor, F. Sherwood |author-link=F. Sherwood Taylor |title=St. Jerome and Vitamin A |journal=Nature |volume=154 |pages=802 |date=23 December 1944 |issue=3921 |doi=10.1038/154802a0|bibcode=1944Natur.154Q.802T |s2cid=4097517 |doi-access=free }}</ref>|author=|title=|source=}} | |||

| === Letters === | |||

| ], early-17th century)]] | |||

| Jerome's letters or ]s, both by the great variety of their subjects and by their qualities of style, form an important portion of his literary remains. Whether he is discussing problems of scholarship, or reasoning on cases of conscience, comforting the afflicted, or saying pleasant things to his friends, scourging the vices and corruptions of the time and against ] among the clergy,<ref>"regulae sancti pachomii 84 rule 104.</ref> exhorting to the ] and renunciation of the ], or debating his theological opponents, he gives a vivid picture not only of his own mind, but of the age and its peculiar characteristics. (See ].) Because there was no distinct line between personal documents and those meant for publication, his letters frequently contain both confidential messages and treatises meant for others besides the one to whom he was writing.<ref>W. H. Fremantle, "Prolegomena to Jerome", V.</ref> | |||

| Due to the time he spent in Rome among wealthy families belonging to the Roman upper class, Jerome was frequently commissioned by women who had taken a vow of virginity to write to them in guidance of how to live their life. As a result, he spent a great deal of his life corresponding with these women about certain abstentions and lifestyle practices.{{sfn|Williams|2006|p=}} | |||

| ]'' by ], {{c.|1595|lk=no}}]] | |||

| === Theological writings === | |||

| ], 1522]] | |||

| ==== Eschatology ==== | |||

| ] | |||

| Jerome warned that those substituting false interpretations for the actual meaning of Scripture belonged to the "synagogue of the Antichrist".<ref>{{cite book |author=Jerome |section=The Dialogue against the Luciferians |page=334 |editor1=Schaff, Philip |editor2=Wace, Henry |title=St. Jerome: Letters and select works, 1893 |series=A Select Library of Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, Second Series |section-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NQUNAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA315 |via=Google Books |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140101063014/https://books.google.com/books?id=NQUNAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA315#PPT19,M1 |archive-date=1 January 2014}}</ref> "He that is not of Christ is of Antichrist," he wrote to ].<ref>{{cite book |author=Jerome |section=Letter to Pope Damasus |page=19 |editor1=Schaff, Philip |editor2=Wace, Henry |title=St. Jerome: Letters and select works, 1893 |series=A Select Library of Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, Second Series |section-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NQUNAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA19 |via=Google Books |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170313134851/https://books.google.com/books?id=NQUNAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA19 |archive-date=13 March 2017}}</ref> He believed that "the mystery of iniquity" written about by Paul in {{nobr|2 Thessalonians 2:7}} was already in action when "every one chatters about his views."<ref>{{cite book |author=Jerome |section=Against the Pelagians |at=Book I, p. 449 |editor1=Schaff, Philip |editor2=Wace, Henry |title=St. Jerome: Letters and select works, 1893 |series=A Select Library of Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, Second Series |section-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NQUNAAAAIAAJ&pg=PT134 |via=Google Books |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140101065949/https://books.google.com/books?id=NQUNAAAAIAAJ&pg=PT134 |archive-date=1 January 2014}}</ref> To Jerome, the power restraining this mystery of iniquity was the Roman Empire, but as it fell this restraining force was removed. He warned a noblewoman of ]:<ref>{{cite book |author=Jerome |section=Letter to Ageruchia |pages=236–237 |editor1=Schaff, Philip |editor2=Wace, Henry |title=St. Jerome: Letters and select works, 1893 |series=A Select Library of Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, Second Series |section-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NQUNAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA236 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140101055138/https://books.google.com/books?id=NQUNAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA236 |archive-date=1 January 2014 }}</ref> | |||

| <blockquote>He that letteth is taken out of the way, and yet we do not realize that Antichrist is near. Yes, Antichrist is near whom the Lord Jesus Christ "shall consume with the spirit of his mouth". "Woe unto them," he cries, "that are with child, and to them that give suck in those days." ... Savage tribes in countless numbers have overrun all parts of Gaul. The whole country between the Alps and the Pyrenees, between the Rhine and the Ocean, has been laid waste by hordes of ], ], ], ], ], Herules, ], ], ], and – alas! for the commonweal! – even ].</blockquote> | |||

| His ''Commentary on Daniel'' was expressly written to offset the criticisms of ],<ref>Eremantle, note on Jerome's commentary on Daniel, in NPAF, 2d series, Vol. 6, p. 500.</ref>{{full citation needed|date=November 2022}} who taught that Daniel related entirely to the time of ] and was written by an unknown individual living in the second century BC. Against Porphyry, Jerome identified Rome as the fourth kingdom of chapters two and seven, but his view of chapters eight and eleven was more complex. Jerome held that chapter eight describes the activity of Antiochus Epiphanes, who is understood as a "type" of a future antichrist; 11:24 onwards applies primarily to a future antichrist but was partially fulfilled by Antiochus. Instead, he advocated that the "little horn" was the Antichrist: | |||

| <blockquote>We should therefore concur with the traditional interpretation of all the commentators of the Christian Church, that at the end of the world, when the Roman Empire is to be destroyed, there shall be ten kings who will partition the Roman world amongst themselves. Then an insignificant eleventh king will arise, who will overcome three of the ten kings. ... After they have been slain, the seven other kings also will bow their necks to the victor.<ref name=jeromedaniel>{{cite web |author=Jerome |title=''Commentario in Danielem'' |website=tertullian.org |url=http://www.tertullian.org/fathers/jerome_daniel_02_text.htm |access-date=6 May 2008 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100526033151/http://www.tertullian.org/fathers/jerome_daniel_02_text.htm |archive-date=26 May 2010}}</ref></blockquote> | |||

| In his ''Commentary on Daniel'',<ref name=jeromedaniel/> he noted, "Let us not follow the opinion of some commentators and suppose him to be either the Devil or some demon, but rather, one of the human race, in whom Satan will wholly take up his residence in bodily form."<ref name=jeromedaniel/> Instead of rebuilding the Jewish Temple to reign from, Jerome thought the Antichrist sat in God's Temple inasmuch as he made "himself out to be like God."<ref name=jeromedaniel/> | |||

| Jerome identified the four prophetic kingdoms symbolized in Daniel 2 as the ], the ], ], and Rome.<ref name=jeromedaniel/>{{rp|style=ama|at=ch. 2, vv. 31–40}} Jerome identified the stone cut out without hands as "namely, the Lord and Savior".<ref name=jeromedaniel/>{{rp|style=ama|at=ch. 2, v. 40}} | |||

| Jerome refuted Porphyry's application of the little horn of chapter seven to Antiochus. He expected that at the end of the world, Rome would be destroyed, and partitioned among ten kingdoms before the little horn appeared.<ref name=jeromedaniel/>{{rp|style=ama|at=ch. 7, v. 8}} | |||

| Jerome believed that Cyrus of Persia was the higher of the two horns of the Medo-Persian ram of Daniel 8:3.<ref name=jeromedaniel/> The he-goat is Greece smiting Persia.<ref name=jeromedaniel/>{{rp|style=ama|at=ch. 8, v. 5}} | |||

| ==== Soteriology ==== | |||

| Jerome opposed the doctrine of ], and wrote against it three years before his death.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Philip Schaff: NPNF2-06. Jerome: The Principal Works of St. Jerome - Christian Classics Ethereal Library |url=https://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf206.vi.ix.i.html |access-date=2024-03-08 |website=www.ccel.org}}</ref> Jerome, despite being opposed to Origen, was influenced by Origenism in his soteriology. Although he taught that the Devil and the unbelieving will be eternally punished (unlike Origen), he believed that the punishment for Christian sinners, who have once believed but sin and fall away, will be temporal in nature. Some scholars such as J.N.D Kelly have also interpreted ] to have held similar views considering the judgement of Christians.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Kelly |first=J. N. D. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=UivDgM0WywoC |title=Early Christian Doctrines |date=2000-11-20 |publisher=A&C Black |isbn=978-0-8264-5252-8 |language=en |quote=Jerome develops the same distinction, stating that, while the Devil and the impious who have denied God will be tortured without remission, those who have trusted in Christ, even if they have sinned and fallen away, will eventually be saved. Much the same teaching appears in Ambrose, developed in greater detail}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Goff |first=Jacques Le |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4dzynjFfX7kC |title=The Birth of Purgatory |date=1986-12-15 |publisher=University of Chicago Press |isbn=978-0-226-47083-2 |language=en |quote=Saint Jerome, though an enemy of Origen, was, when it came to salvation, more of an Origenist than Ambrose. He believed that all sinners, all mortal beings, with the exception of Satan, atheists, and the ungodly, would be saved: 'Just as we believe that the torments of the Devil, of all the deniers of God, of the ungodly who have said in their hearts, 'there is no God,' will be eternal, so too do we believe that the judgment of Christian sinners, whose works will be tried and purged in fire will be moderate and mixed with clemency.' Furthermore, 'He who with all his spirit has placed his faith in Christ, even if he die in sin, shall by his faith live forever.'"}}</ref> {{sfn|Augustine|Lombardo|1988|pp=64, 65|ps=. "Augustine, however, does not mention any names, and there is no evidence either here or in any other place that he is referring to these passages from the works of Jerome. Nevertheless, both Jerome and Ambrose seemed to have shared in the not uncommon error of their time, namely, that all Christians would sooner or later be reunited to God, an error which Augustine refutes here and in a number of other places"}} | |||

| Although Augustine does not name Jerome personally, the view that all Christians would eventually be reunited to God was criticized by Augustine in his treatise "on faith and works".{{sfn|Augustine|Lombardo|1988|pp=64, 65|ps=. "Augustine, however, does not mention any names, and there is no evidence either here or in any other place that he is referring to these passages from the works of Jerome. Nevertheless, both Jerome and Ambrose seemed to have shared in the not uncommon error of their time, namely, that all Christians would sooner or later be reunited to God, an error which Augustine refutes here and in a number of other places"}} | |||

| ===Reception by later Christianity=== | |||

| ]]] | |||

| Jerome is the second-most voluminous writer – after ] (354–430) – in ancient Latin Christianity. The ] recognizes him as the ] of translators, librarians, and ]s.<ref>{{cite web |last=Kemp |first=Jane |title=St. Jerome: Patron saint of librarians |website=Luther College Library and Information Services (luther.edu) |place=Decorah, IA |publisher=] |url=http://www2.luther.edu/library/about/history/40th/jerome/ |url-status=live |access-date= 2 June 2014 |archive-url= | |||

| https://web.archive.org/web/20240417235456/http://www2.luther.edu/library/about/history/40th/jerome/ |archive-date= April 17, 2024}}</ref> | |||

| Jerome translated many biblical texts into Latin from Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek. His translations formed part of the '']''; the ''Vulgate'' eventually superseded the preceding Latin translations of the Bible (the '']''). The ] in 1546 declared the ''Vulgate'' authoritative "in public lectures, disputations, sermons, and expositions".<ref>{{cite web |last=Akin |first=Jimmy |title=Is the ''Vulgate'' the Catholic Church's official Bible? |type=blog |url=https://www.ncregister.com/blog/is-the-vulgate-the-catholic-church-s-official-bible |access-date=8 December 2021 |newspaper=] |date=5 September 2017 |language=en |quote= ' sacred and holy Synod – considering that no small utility may accrue to the Church of God, if it be made known which out of all the Latin editions, now in circulation, of the sacred books, is to be held as authentic – ordains and declares, that the said old and vulgate edition, which, by the long use of so many years, has been approved of in the Church, be, in public lectures, disputations, sermons and expositions, held as authentic; and that no one is to dare, or presume to reject it under any pretext whatever' .}}</ref><ref>{{cite encyclopedia |title=Vulgate |year=2005 |dictionary=The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-280290-3 |pages=1722–1723|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=fUqcAQAAQBAJ |via=Google Books}}</ref> | |||

| Jerome showed more zeal and interest in the ascetic ideal than in abstract speculation. He lived as an ascetic for 4~5 years in the Syrian desert, and later near Bethlehem for 34 years. Nevertheless, his writings show outstanding scholarship<ref>{{cite book |last=Power |first=Edward J. |date=1991 |title=A Legacy of Learning: A history of western education |publisher=SUNY Press |isbn=978-0-7914-0610-6 |page=102 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Upup1CZKAsEC&pg=PA102 |language=en |quote=his exceptional scholarship produced ...}}</ref> and his correspondence has great historical importance.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |last=Louth |first=Andrew |date=2022 |title=Jerome |dictionary=The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-263815-1 |pages=872–873 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3CNeEAAAQBAJ&pg=PT2305 |lang=en |quote=His correspondence is of great interest and historical importance.}}</ref> | |||

| The ] ] Jerome with a ] on 30 September.<ref>{{cite web |title=The Calendar |website=] |language=en |url=https://www.churchofengland.org/prayer-and-worship/worship-texts-and-resources/common-worship/churchs-year/calendar | |||

| |access-date=8 April 2021 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| == In art == | |||

| {{anchor|Lion}}<!-- This Anchor tag serves to provide a permanent target for incoming section links. Please do not remove it, nor modify it, except to add another appropriate anchor. If you modify the section title, please anchor the old title. It is always best to anchor an old section header that has been changed so that links to it will not be broken. See ] for details. This template is {{subst:Anchor comment}} -->Jerome is also often depicted with a lion, in reference to the popular ] belief that Jerome once tamed a lion in the wilderness by healing its paw. The source for the story may actually have been the second century Roman tale of ], or confusion with the exploits of ] (Jerome in later Latin is "Geronimus");<ref>Hope Werness, ''Continuum encyclopaedia of animal symbolism in art'', 2006</ref>{{efn|name=EugeneRice}} it is "a figment" found in the thirteenth-century '']'' by ].{{sfn|Williams|2006|p=1}} Hagiographies of Jerome talk of his having spent many years in the Syrian desert, and artists often depict him in a "wilderness", which for West European painters can take the form of a wood.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.catholic-saints.info/patron-saints/saint-jerome.htm |title=Saint Jerome in Catholic Saint info |publisher=Catholic-saints.info |access-date=2 June 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140429031454/http://www.catholic-saints.info/patron-saints/saint-jerome.htm |archive-date=29 April 2014 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

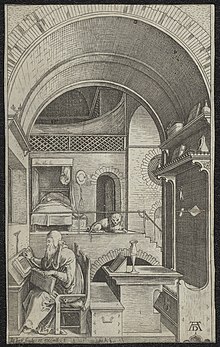

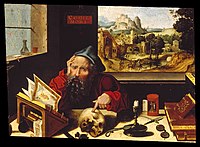

| From the late Middle Ages, depictions of Jerome in a wider setting became popular. He is either shown in his study, surrounded by books and the equipment of a scholar, or in a rocky desert, or in a setting that combines both aspects, with him studying a book under the shelter of a rock-face or cave mouth. His study is often shown as large and well-provided for, he is often clean-shaven and well-dressed, and a ] may appear. These images derive from the tradition of the ], though Jerome is often given the library and desk of a serious scholar. His attribute of the lion, often shown at a smaller scale, may be beside him in either setting. The subject of "Jerome Penitent" first appears in the later 15th century in Italy; he is usually in the desert, wearing ragged clothes, and often naked above the waist. His gaze is usually fixed on a ] and he may beat himself with his fist or a rock.<ref>Herzog, Sadja. “Gossart, Italy, and the National Gallery's Saint Jerome Penitent.” Report and Studies in the History of Art, vol. 3, 1969, pp. 67–70, , Retrieved 29 December 2020.</ref> In one of Georges de La Tour's 17th century French versions of St. Jerome his penitence is depicted alongside his red cardinal hat.<ref>Judovitz, Dalia. ''Georges de La Tour and the Enigma of the Visible'', New York, Fordham University Press, 2018. {{ISBN|0-82327-744-5}}; {{ISBN|9780823277445}}. p11, 19-22, 98, plate 3.</ref> | |||

| Jerome is often depicted in connection with the '']'' motif, the reflection on the meaninglessness of earthly life and the transient nature of all earthly goods and pursuits. In the 16th century ] by ] and workshop, the saint is depicted with a skull. Behind him on the wall is pinned an admonition, ''Cogita Mori'' ("Think upon death"). Further reminders of the ''vanitas'' motif of the passage of time and the imminence of death are the image of the ] visible in the saint's Bible, the candle and the hourglass.<ref>{{cite web |publisher=] |url=http://art.thewalters.org/detail/35964/saint-jerome-in-his-study/ |title=Saint Jerome in His Study |access-date=6 September 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120918103639/http://art.thewalters.org/detail/35964/saint-jerome-in-his-study |archive-date=18 September 2012 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Both ] and ] portrayed ]. | |||

| Jerome is also sometimes depicted with an ], the symbol of wisdom and scholarship.<ref name="NMSU"> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121022221000/http://artdepartment.nmsu.edu/faculty/zarursite/retablo/col-saints.html |date=22 October 2012 }}, gallery of the religious art collection of ], with explanations. Retrieved 10 August 2007.</ref> ]s and the trumpet of ] are also part of his ].<ref name="NMSU" /> | |||

| A four and three quarters foot tall limestone statue of Jerome was installed above the entrance of O'Shaughnessy Library on the campus of ] (then College of St. Thomas) in St. Paul Minnesota in October 1950. The sculptor was ] and the stone carver was Egisto Bertozzi.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Sculpture |url=https://www.kiselewskisculpture.com/ |access-date=2023-04-27 |website=Joseph Kiselewski |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Egisto Bertozzi – Stone Carver |url=https://saintjameslutheran.com/content.cfm?id=9078 |access-date=2023-04-27 |website=Saint James Lutheran Church |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| <gallery widths="200" heights="200"> | |||

| File:Vatican Museums 2020 P31 Leonardo da Vinci Saint Jerome.jpg|''Saint Jerome in the Wilderness'', ], 1480–1490, Vatican Museums | |||

| File:St Jerome Penitent in the Wilderness - Rijksmuseum.jpg|''Jerome Penitent in the Wilderness''. Copper engraving, ] 1494–1498 | |||

| File:Lucas Cranach d.Ä. - Der heilige Hieronymus (ca.1515, Mexico City).jpg|''Saint Jerome in the Wilderness'' by ] {{c.|1515|lk=no}} | |||

| File:Saint Jerome in his Study.jpg|''Hieronymus in Gehäus''. Copper engraving, ] 1514 | |||

| File:St.Jerome MET.jpg|''Saint Jerome'' {{c.|1520|lk=no}} Netherlandish stained glass window at MET. | |||

| File:Bernardino Luini - The Penitent St Jerome - WGA13761.jpg|''The Penitent St Jerome'' by ], {{c.|1520|1525|lk=no}}. | |||

| File:Lucas Cranach d.Ä. - Der heilige Hieronymus (ca.1525, Ferdinandeum).jpg|Saint Jerome by Lucas Cranach the Elder, {{c.|1525|lk=no}} | |||

| File:Workshop of Pieter Coecke van Aelst, the elder - Saint Jerome in His Study - Walters 37256.jpg|''Saint Jerome in his study'', {{c.|1530|lk=no}} by ] and Workshop, ] | |||

| File:Saint Jerome in Meditation-Caravaggio (1606).jpg|''Saint Jerome penitent'' by ], {{c.|1606|lk=no}}. | |||

| File:El Greco - San Jerónimo - Google Art Project.jpg|''Saint Jerome'' by ], {{c.|1605|1610|lk=no}}. | |||

| File:Jacques Blanchard - Hl. Hieronymus.jpg|Painting of Saint Jerome by ], 1632. | |||

| File:Gabriel Thaller; Sveti Jeronim i pavlini (18.st.).jpg|''Saint Jerome and the Paulines'' painted by Gabriel Thaller in the St. Jerome Church in ], ], northern Croatia (18th century) | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| == See also == | |||

| {{portal|Saints|Christianity}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| == References == | |||

| ===Notes=== | |||

| {{notelist|refs= | |||

| {{efn|name=EOC|In the Eastern Orthodox Church he is known as ''Saint Jerome of Stridonium'' or ''Blessed Jerome''. "Blessed" in this context does not have the sense of being less than a saint, as it does in the West.}} | |||

| {{efn|name=EugeneRice|] has suggested that in all probability the story of Gerasimus's lion became attached to the figure of Jerome some time during the seventh century, after the military invasions of the Arabs had forced many Greek monks who were living in the deserts of the Middle East to seek refuge in Rome. {{harvnb|Rice|1985|pp=44–45}} conjectures that because of the similarity between the names Gerasimus and Geronimus—the late Latin form of Jerome's name—'a Latin-speaking cleric … made St Geronimus the hero of a story he had heard about St Gerasimus; and that the author of ''Plerosque nimirum'', attracted by a story at once so picturesque, so apparently appropriate, and so resonant in suggestion and meaning, and under the impression that its source was ] who had been told it in Bethlehem, included it in his life of a favourite saint otherwise bereft of miracles.'" {{harv|Salter|2001|p=12}} }} | |||

| {{efn|name=PL|''] 25, 373'': Crebroque cryptas ingredi, quae in terrarum profunda defossae, ex utraque parte ingredientium per parietes habent corpora sepultorum, et ita obscura sunt omnia, ut propemodum illud propheticum compleatur: ''Descendant ad infernum viventes'' (Ps. LIV,16): et raro desuper lumen admissum, horrorem temperet tenebrarum, ut non-tam fenestram, quam foramen demissi luminis putes: rursumque pedetentim acceditur, et caeca nocte circumdatis illud Virgilianum proponitur (Aeneid. lib. II): "Horror ubique animos, simul ipsa silentia terrent."}} | |||

| {{efn|name=ndq|"(...) die griechische Bibelübersetzung, die einem innerjüdischen Bedürfnis entsprang (...) Rabbinen zuerst gerühmt (...) Später jedoch, als manche ungenaue Übertragung des hebräischen Textes in der Septuaginta und Übersetzungsfehler die Grundlage für hellenistische Irrlehren abgaben, lehte man die Septuaginta ab." {{harv| Homolka | 1999 | pp=43–}} }} | |||

| }} | |||

| ===Citations=== | |||

| {{reflist}} | |||

| ===Sources=== | |||

| {{refbegin}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |language=en |last1=Augustine |last2=Lombardo |first2=Gregory J. |title=On Faith and Works |location=New York, NY |publisher=Paulist Press |date=1988 |isbn=978-0-8091-0406-2}} | |||

| * Andrew Cain and Josef Lössl, ''Jerome of Stridon: His Life, Writings and Legacy'' (London and New York, 2009) | |||

| * {{cite book | last=Homolka | first=W. | title=Die Lehren des Judentums nach den Quellen | publisher=Knesebeck | issue=v. 3 | year=1999 | isbn=978-3-89660-058-5 | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6i6VSwAACAAJ | language=de|volume=Bd. 3|location=Munich|via=Verband der Deutschen Juden}} | |||

| * {{cite book|first=J.N.D. |last=Kelly |title=Jerome: His Life, Writings, and Controversies |publisher=Harper & Row |place=New York |year=1975}} | |||

| * {{cite book | last1=Kurian | first1=G.T. | last2=Smith | first2=J.D. | title=The Encyclopedia of Christian Literature | publisher=Scarecrow Press | issue=v. 2 | year=2010 | isbn=978-0-8108-7283-7 | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=dk4G-52QT-8C&pg=PA389}} | |||

| * {{Citation |first=Robert |last=Payne |title=The Fathers of the Western Church |publisher=Viking Press |place=New York |year=1951}} | |||

| * {{cite book |last1=Pevarello |first1=Daniele |title=The Sentences of Sextus and the origins of Christian ascetiscism |date=2013 |publisher=Mohr Siebeck |location=Tübingen |isbn=978-3-16-152579-7 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=2Fgfxmz2EToC&pg=PA1 }} | |||

| * {{Citation |first=Stefan |last=Rebenich |title=Jerome |year=2002|publisher=Psychology Press |isbn=978-0415199063|url= https://books.google.com/books?id=nDKJUq2WMgEC}} | |||

| * {{cite book | last=Rice | first=E.F. | title=Saint Jerome in the Renaissance | publisher=Johns Hopkins University Press | series=Johns Hopkins symposia in comparative history | year=1985 | isbn=978-0-8018-2381-7 | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=VNU5D7ZdhzoC }} | |||

| * {{cite book | last1=Salisbury | first1=J.E. | last2=Lefkowitz | first2=M.R. | title=Encyclopedia of Women in the Ancient World | publisher=ABC-CLIO | series=ABC-CLIO E-Books | year=2001 | isbn=978-1-57607-092-5 | chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=HF0m3spOebcC&pg=PA32 | author-link=Joyce E. Salisbury|chapter=Blaesilla}} | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Salter |first=David |title=Holy and Noble Beasts: Encounters With Animals in Medieval Literature |year=2001 |publisher=D. S. Brewer |isbn=978-0-85991-624-0 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=kctEkMyhztQC&pg=PA11 }} | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Scheck |first=Thomas P. |title=Commentary on Matthew |series=The Fathers of the Church|volume=117 |date=2008 |isbn=978-0-8132-0117-7 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=j0UmWBivNJgC&pg=PA5 }} | |||

| * {{cite journal|first=Martin|last=Slepička|title=Úcta k svatému Jeronýmovi v českém středověku: 1600. výročí smrti církevního otce svatého Jeronýma|journal=Slepička, Martin. Úcta K Svatému Jeronýmovi V Českém Středověku. K 1600. Výročí Smrti Církevního Otce Svatého Jeronýma. 1. Vyd. Ostrava: Repronis, 2021 |publisher=Repronis |place=Ostrava |year=2021 | url=https://www.academia.edu/49243338 }} | |||

| * {{cite book|first=Tom |last=Streeter|title=The Church and Western Culture: An Introduction to Church History|publisher= AuthorHouse |date=2006}} | |||

| * {{Citation |editor-first=Michael |editor-last=Walsh |title=Butler's Lives of the Saints |publisher=HarperCollins |place=New York |year=1992}} | |||

| * {{cite book|first=Maisie |last=Ward|title=Saint Jerome|publisher=Sheed & Ward|location= London |date=1950}} | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Williams |first=Megan Hale |title=The Monk and the Book: Jerome and the Making of Christian Scholarship |year=2006 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=7nWdiTsjOtUC |publisher=U of Chicago Press |location=Chicago |isbn=978-0-226-89900-8 }} | |||

| * ''Biblia Sacra Vulgata'' | |||

| * {{Schaff–Herzog|title=Jerome|volume=6|url=https://archive.org/details/newschaffherzog07haucgoog/page/126/mode/2up}} | |||

| {{refend}} | |||

| == Further reading == | |||

| {{refbegin}} | |||

| * Saint Jerome, ''Three biographies: Malchus, St. Hilarion and Paulus the First Hermit Authored by Saint Jerome'', London, 2012. limovia.net. {{ISBN|978-1-78336-016-1}} | |||

| {{refend}} | |||

| == External links == | |||

| {{Wikiquote|Jerome}} | |||

| {{Commons category|Saint Jerome}} | |||

| {{Wikisourcelang|la|Categoria:Vulgata}} | |||

| * ( {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160909170851/http://www.u.arizona.edu/~aversa/jerome.pdf |date=9 September 2016 }}) from ]'s ''Lives of the Saints'' | |||

| * | |||

| * {{CathEncy|wstitle=St. Jerome}} | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * Orthodox ] | |||

| * | |||

| * at the Christian Iconography web site | |||

| * from Caxton's translation of the Golden Legend | |||

| * at Somni {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150511160533/http://roderic.uv.es/handle/10550/2407/browse?value=Jeroni%2C+sant%2C+ca.+342-420&type=author |date=11 May 2015 }} | |||

| ** , digitized codex (1464) | |||

| ** , digitized codex (1475–1490) | |||

| ** , digitized codex (1490) | |||

| ** , digitized codex (1470–1480) | |||

| * | |||

| * {{Librivox author |id=14959}} | |||

| === Latin texts === | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * , a list of names of people in the Bible and etymologies, based on a work attributed to ] and expanded by ] | |||

| * of the ], listing and commenting on places mentioned in the Bible | |||

| ==== Facsimiles ==== | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| === English translations === | |||

| * {{cite book |author=Jerome |author-link=Jerome |year=1887 |url=https://archive.org/details/cu31924028534190 |title=The pilgrimage of the holy Paula |publisher=]}} | |||

| * | |||

| * : Preface to the Gospels | |||

| * | |||

| * (under "Jerome") | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * , The Life of Paulus the First Hermit, The Life of S. Hilarion, The Life of Malchus, the Captive Monk, The Dialogue Against the Luciferians, The Perpetual Virginity of Blessed Mary, Against Jovinianus, Against Vigilantius, To Pammachius against John of Jerusalem, Against the Pelagians, Prefaces (CCEL) | |||

| * | |||

| {{Christian History}} | |||

| {{Navboxes | |||

| |list= | |||

| {{History of Catholic theology}} | |||

| {{Catholic saints}} | |||

| {{Latin Church footer}} | |||

| {{History of the Catholic Church}} | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Subject bar |portal1= Biography |portal2= Christianity |portal3= Saints}} | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 03:25, 6 January 2025

4th- and 5th-century priest and theologian This article is about the priest and Bible translator. For other uses, see Jerome (disambiguation) and Saint Jerome (disambiguation).

| Part of a series on | ||||

| Catholic philosophy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Aquinas, Scotus, and Ockham Aquinas, Scotus, and Ockham | ||||

| Ethics | ||||

| Metaphysics | ||||

| Schools | ||||

Philosophers

|

||||

Jerome (/dʒəˈroʊm/; Latin: Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus; Ancient Greek: Εὐσέβιος Σωφρόνιος Ἱερώνυμος; c. 342–347 – 30 September 420), also known as Jerome of Stridon, was an early Christian priest, confessor, theologian, translator, and historian; he is commonly known as Saint Jerome.

He is best known for his translation of the Bible into Latin (the translation that became known as the Vulgate) and his commentaries on the whole Bible. Jerome attempted to create a translation of the Old Testament based on a Hebrew version, rather than the Septuagint, as prior Latin Bible translations had done. His list of writings is extensive. In addition to his biblical works, he wrote polemical and historical essays, always from a theologian's perspective.

Jerome was known for his teachings on Christian moral life, especially those in cosmopolitan centers such as Rome. He often focused on women's lives and identified how a woman devoted to Jesus should live her life. This focus stemmed from his close patron relationships with several prominent female ascetics who were members of affluent senatorial families.

In addition, his works are a crucial source of information on the pronunciation of the Hebrew language in Byzantine Palestine.

Due to his work, Jerome is recognized as a saint and Doctor of the Church by the Catholic Church, and as a saint in the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Lutheran Church, and the Anglican Communion. His feast day is 30 September (Gregorian calendar).

Early life

Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus was born at Stridon around 342–347 AD. He was of Illyrian ancestry. He was not baptized until about 360–369 in Rome, where he had gone with his friend Bonosus of Sardica to pursue rhetorical and philosophical studies. (This Bonosus may or may not have been the same Bonosus whom Jerome identifies as his friend who went to live as a hermit on an island in the Adriatic.) Jerome studied under the philologist Aelius Donatus. There he learned Latin and at least some Koine Greek, though he probably did not yet acquire the familiarity with Greek literature that he later claimed to have acquired as a schoolboy.

As a student, Jerome engaged in the superficial escapades and sexual experimentation of students in Rome; he indulged himself quite casually but he suffered terrible bouts of guilt afterwards. To appease his conscience, on Sundays he visited the sepulchers of the martyrs and the Apostles in the catacombs. This experience reminded him of the terrors of Hell:

Often I would find myself entering those crypts, deep dug in the earth, with their walls on either side lined with the bodies of the dead, where everything was so dark that almost it seemed as though the Psalmist's words were fulfilled, Let them go down quick into Hell. Here and there the light, not entering in through windows, but filtering down from above through shafts, relieved the horror of the darkness. But again, as soon as you found yourself cautiously moving forward, the black night closed around and there came to my mind the line of Virgil, "Horror ubique animos, simul ipsa silentia terrent".

The quotation from Virgil reads, in translation, "On all sides round, horror spread wide; the very silence breathed a terror on my soul".

Conversion to Christianity

Although at first afraid of Christianity, he eventually converted.

Seized with a desire for a life of ascetic penance, Jerome went for a time to the desert of Chalcis, to the southeast of Antioch, known as the "Syrian Thebaid" from the number of eremites (hermits) inhabiting it. During this period, he seems to have found time for studying and writing. He made his first attempt to learn Hebrew under the guidance of a converted Jew; and he seems to have been in correspondence with Jewish Christians in Antioch. Around this time he had copied for himself a Hebrew Gospel, of which fragments are preserved in his notes. It is known today as the Gospel of the Hebrews, which the Nazarenes considered to be the true Gospel of Matthew. Jerome translated parts of this Hebrew Gospel into Greek.

Ministry in Rome

As protégé of Pope Damasus I, Jerome was given duties in Rome, and he undertook a revision of the Vetus Latina Gospels based on Greek manuscripts. He also updated the Psalter containing the Book of Psalms then in use in Rome, based on the Septuagint.

Throughout his epistles he shows himself to be surrounded by women and united with close ties; it is estimated that 40% of his epistles were addressed to someone of the female sex and, at the time, he was criticized for it.

Even in his time, Jerome noted Porphyry's accusation that the Christian communities were run by women and that the favor of the ladies decided who could accede to the dignity of the priesthood.

In Rome, Jerome was surrounded by a circle of well-born and well-educated women, including some from the noblest patrician families. Among these women were such as the widows Lea, Marcella, and Paula, and Paula's daughters Blaesilla and Eustochium. The resulting inclination of these women towards the monastic life, away from the indulgent lasciviousness in Rome, and his unsparing criticism of the secular clergy of Rome, brought a growing hostility against him among the Roman clergy and their supporters. Soon after the death of his patron Pope Damasus I on 10 December 384, Jerome was forced to leave his position at Rome after an inquiry was brought up by the Roman clergy into allegations that he had an improper relationship with the widow Paula. Still, his writings were highly regarded by women who were attempting to maintain vows of becoming consecrated virgins. His letters were widely read and distributed throughout the Christian empire and it is clear through his writing that he knew these virgin women were not his only audience.

Additionally, Jerome's condemnation of Blaesilla's hedonistic lifestyle in Rome led her to adopt ascetic practices, but these affected her health and worsened her physical weakness to the point that she died just four months after starting to follow his instructions; much of the Roman populace was outraged that Jerome, in their view, thus caused the premature death of such a lively young woman. Additionally, his insistence to Paula that Blaesilla should not be mourned and complaints that her grief was excessive were seen as heartless, which further polarized Roman opinion against him.

Scholarly works

Translation of the Bible (382–405)

Jerome was a scholar at a time when being a scholar implied a fluency in Greek. He knew some Hebrew when he started his translation project, but moved to Jerusalem to strengthen his grip on Jewish scripture commentary. A wealthy Roman aristocrat, Paula, funded Jerome's stay in a monastery in the nearby city of Bethlehem, where he settled next to the Church of the Nativity – built half a century prior on orders of Emperor Constantine over what was reputed to be the site of the Nativity of Jesus – and he completed his translation there. He began in 382 by correcting the existing Latin-language version of the New Testament, commonly referred to as the Vetus Latina. By 390 he turned to translating the Hebrew Bible from the original Hebrew, having previously translated portions from the Septuagint which came from Alexandria. He believed that the mainstream Rabbinical Judaism had rejected the Septuagint as invalid Jewish scriptural texts because of what were ascertained as mistranslations along with its Hellenistic heretical elements. He completed this work by 405. Prior to Jerome's Vulgate, all Latin translations of the Old Testament were based on the Septuagint, not the Hebrew. Jerome's decision to use a Hebrew text instead of the previously translated Septuagint went against the advice of most other Christians, including Augustine, who thought the Septuagint inspired. Modern scholarship, however, has sometimes cast doubts on the actual quality of Jerome's Hebrew knowledge. Many modern scholars believe that the Greek Hexapla is the main source for Jerome's "iuxta Hebraeos" (i.e. "close to the Hebrews", "immediately following the Hebrews") translation of the Old Testament. However, detailed studies have shown that to a considerable degree Jerome was a competent Hebraist.

Biblical onomastica

Jerome also produced two onomastica:

- Liber de Nominibus Hebraicis, a list of names of people in the Bible and etymologies, based on a work attributed to Philo and expanded by Origen

- A translation and expansion of the Onomasticon of Eusebius, listing and commenting on places mentioned in the Bible

Commentaries (405–420)

For the next 15 years, until he died, Jerome produced a number of commentaries on Scripture, often explaining his translation choices in using the original Hebrew rather than suspect translations. His patristic commentaries align closely with Jewish tradition, and he indulges in allegorical and mystical subtleties after the manner of Philo and the Alexandrian school. Unlike his contemporaries, he emphasizes the difference between the Hebrew Bible "Apocrypha" and the Hebraica veritas of the protocanonical books. In his Vulgate's prologues, he describes some portions of books in the Septuagint that were not found in the Hebrew as being non-canonical (he called them apocrypha); for Baruch, he mentions by name in his Prologue to Jeremiah and notes that it is neither read nor held among the Hebrews, but does not explicitly call it apocryphal or "not in the canon". His Preface to the Books of Samuel and Kings (commonly called the Helmeted Preface) includes the following statement: